In 1981, a burial mound in southern Russia near Chingul was excavated. The archeologists working on the site found a magnificent treasure hoard buried with a nomadic chieftain. The find included items from Rus’, Byzantium, and the Middle East, attesting to the trade routes of the time. The article translated below is an overview of the find and history of the Polovtsy/Kipchak nomads of the time, in an attempt to identify the chieftain who was buried at this site.

A Polovtsy Khan, or…?

A translation of Отрошенко, В., Рассамакин, Ю. “Половецкий хан или?…” Знание — сила. 1986(7), pp. 30-32.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://preview.tinyurl.com/y48yc92d

In 1982, in the 6th issue of the journal “Knowledge is Power,” we described the discovery on an extremely rich tomb of a medieval nomad found in a burial mound in the city of Chingul’ [jeb: in south-east Ukraine] on the banks of the Molochnaja River. At that time, while acquainting our readers with the circumstances of the discovery, we expressed our theories about which of the Polovtsy khans from the late 12th-early 13th century may have been buried in this mound. Without exact dates for many items from the mound, the authors of the hypothesis could not yet take all details into account.

Köten Khan?

First, a short recap about the Chingul’ grave. A wooden sarcophagus stood at the bottom of a spacious, deep grave. In it, the skeleton of a solidly built male, dressed in a sumptuous, gold-fabric kaftan of Byzantine silk with three silk belts decorated with gilt silver buckles. On the chest was a thick chain made from an alloy of silver and gold, and the legs were bound with a golden cord. His fingers had rings with gems, and the right hand grasped a straightened gold torc. On this left were a sabre, a sheathed bow, a quiver with arrows, a shield, a helmet, and 3 knives. The helmet, shield casing, the rays on the quiver, and knife handles were gilded. Near the shoulders were a silver and gilt chalice and incense burner. Amphorae were placed around the sarcophagus, and around the grave pit there were five Arabian horses with bridles and saddles. The bridle straps were decorated with gilt silver.

S. Krug obtained additional information through the examination of the skeleton. The interred male was about 40-50 years old, tall, sturdily built, and Mongoloid — but his Mongoloid features were few and smoothed over, as was characteristic for pagan burials burials of the 12th-13th centuries on Ukrainian lands. The occipital part of the skull there was a dent and two healed scars from sabre cuts, and the crown was pierced by a five-sided hole.

These were the collected data. But, who was he?

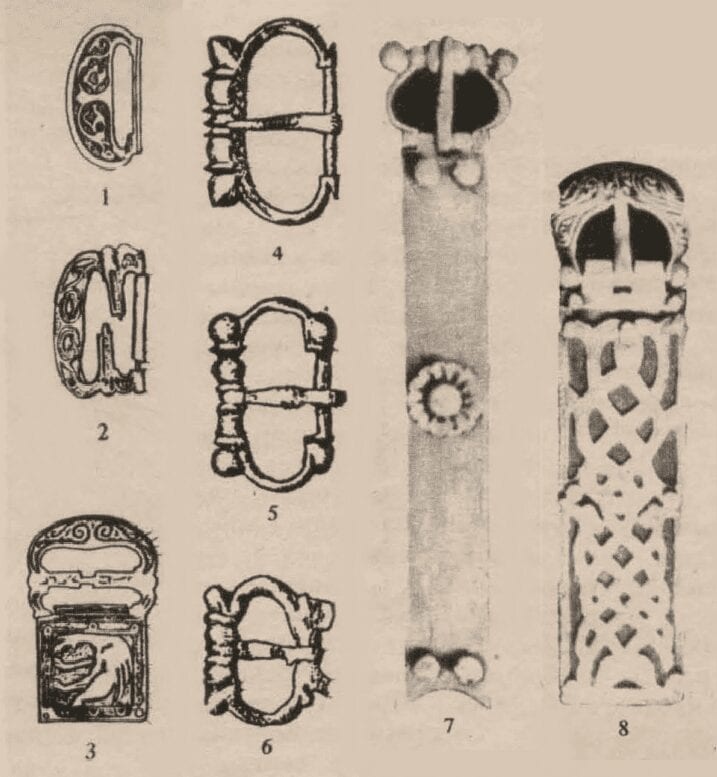

We began our investigation by dating the items in the burial mound, paying particular attention to the belts. Craftsmen have always changed the form and decoration of their works according to the fashion and tastes of their customers. Our task was made easier by a study of famous belts from the 13th-14th centuries, collected, dated and published by German researcher I. Fingerlin in 1971. Two buckles from the Chingul’ burial mound with multi-colored enamel insets and images of beasts, according to set, date to the first half of the 13th century; a third dates to 1230-1289. Thus, the three could have coexisted sometime in the 1230-1240’s. It was during these 20 years that European knights girded themselves with belts with similarly decorated buckles.

Knight belt findings are important not only for dating purposes, but also as a category of items related to the Polovtsy. Belts were found in large numbers and varieties in Polovtsy (Komans, Kuns) graves in Hungary. In this manner, our search found not only landmarks in time, but our glance also was drawn to Hungary. But, let’s leave for now these widespread parallels and look instead at the Polovtsy steppe at the beginning of the 1330s…

There is no peace among the Polovtsy. Hunting is a entertaining sport on the steppe, and a secondary source of power. But, the beloved son of Köten Khan of the Durut Mangush tribe does not return from the hunt. Soon, one of the khan’s confidants brings him the woeful news of his son’s capture and death at the hands of Akku, bull of the Toksoba tribe. The Durut tribe vows to avenge themselves against the offender and decimates Akku’s army. The wounded Taksoba leader sends his brother to the Mongols with a complaint against the Durut and requesting help. The Mongols were monitoring the situation on the steppe, attentively responded to the request, sending a force of 30,000 men against Köten.

of the mound.

Such Mongol raids were typically reconnaissance missions. The Mongols took active steps to conquer the Polovtsy steppe only after 1235, when in the city of Karakorum, they decided “to take possession of the lands of the Bulgars, the Asovs, and of Rus’.” This list of nations cited by the Persian author Juvayni does not mention the Polovtsy, whom the Mongols considered their “serfs and stablemen,” obliged to submit to their blood masters. But, the Polovtsy did not even think of submitting. One of the most active leaders of the resistance against the Mongol invaders was Khan Köten Sutoevich.

It’s clear that our attention was drawn to the colorful figure of this intransigent warrior against the eastern invaders. He is attractive because Köten was a relative and ally of the powerful Princes of Rus’ Mstislav the Daring and D of Galicia, as well as King Bela IV of Hungary. Had Köten been buried in the Chingul’ mound, this would explain why so many objects of medieval Russian and western European objects were found here. This first guess, however tempting at first glance, quickly fell apart.

Why? In 1239, the Mongol horde campaigned against Crimea, pushing the opposing Polovtsy further and further west. Köten, not wishing to surrender to the mercy of the victors, negotiated with Bela IV about the resettlement of the Polovtsy in Hungary.

The negotiations took place in the Autumn of 1239, and soon the immigrants occupied a key position in the royal court. As P. Golubovskij writes: “The king gives preference to the Polovtsy at meetings and councils, and Köten’s daughter Erzhebet (Elizaveta) becomes an heiress to the throne. The interests of local magnates are severely infringed, and for the common people, the presence of these restless, plundering nomads brings a heap of trouble. An anti-Polovtsian conspiracy ripens: Köten is accused of colluding with the Mongols and Russians, and by decision of the royal council, he and his family are thrown into prison. Köten tries to explain himself to the king, but the conspirators are one step ahead of him. The Hungarians and Germans break into the prison, seize the prince’s entire family, immediately behead them, and throw their heads through a window to the crowds.”

Thus, the khan died, but the battle-worthy horde he brought with him to Hungary remained. This was of particular importance to us, for the man interred in the Chingul’ burial mound must have visited Hungary – so many objects that belonged to him are associated with it.

The execution of the Polovtsy elite occured in Pest early in 1241, and by the 10th of March, Bela IV had received news that the Mongols had invaded Hungary via the “Russian Gate” (the Veretsky Pass). The person who gained the most from Köten’s death turned out to be Batu Khan.

And what about the Polovtsy? They were paid off in full for the death of their leader. The royal army was defeated, and the enraged nomads, burning towns and villages, rushed to the Balkans and the Bulgarian border. As they killed, they would remind each of their victims: “This is for Köten!” The Polovtsians’ sequence of actions suggests that this invasion of Bulgaria was probably conceived by Köten and that not all of the Polovtsy leaders were executed. It was they who led the horde on to the next war, leaving behind an acute shortage of professional soldiers.

In the Balkans, the 1240s were marked by the confrontation of 3 forces: the Crusaders of the Roman Empire who seized Constantinople in 1204; the Greeks of the Nicene empire; and the Bulgarians, who were strengthening their own kingdom. Each of them tried to attract the Polovtsy to their side, while the nomads sought to sell their services to the highest bidder. There are well-known examples of Polovtsy women marrying important nobles of the Roman Empire, who would have owned knight’s regalia. Items produced in western Europe thus could have come to one of the leaders of the horde as wedding gifts (dowry) for one of these daughters. This possibility is described by Hungarian historian A. Palochi-Khorvat, as well as Soviet researcher B. Marshak.

After the aforementioned events in the Balkans, some Polovtsy returned to Hungary, while others of the Golden Horde were forced to return to the steppes, and a third appeared in Rus’. And thus our story has a Russian angle.

Tigak Khan?

In the hot summer of 1248, near the town of Pozhga (now Bratislava), King Bela IV meets Prince Daniil of Galicia. With undisguised admiration and in quite some detail, a chronicler described the ceremonial garb of the Russian prince: “Daniil himself rode before the king, according to Russian custom. The horse beneath him was a wonder, with a saddle of burnished gold, and arrows and sabre decorated with gold other decorations worthy of astonishment: a case of Greek tin, sewn about with wide gold lace, and shoes of green leather embroidered with gold.” This description is extremely interesting. Prince Daniil’s outfit in this description is almost identical to the kaftan of the Chingul’ khan.

Relations of the princes of Galicia with the Polovtsy throughout the first half of the 13th century were friendly, despite these dramatic turns of history. After the first blow of the Mongols in 1222, Köten rode to Galicia, to visit his son-in-law Mstislav the Daring, bringing along many gifts from the steppe, to seek aid from the Russian princes. Mstislav heard this petition not only because of political considerations, but because he previously had himself spent 2 years at Köten’s headquarters, and it was only with the aid of his force that, in 1221, he was able to suppress an uprising in Galicia by boyars united with the Hungarians. Later, his son-in-law Daniil, together with the hand of his daughter Anna, grand-daughter of Köten, would carry on the tradition of friendship with the Polovtsy.

In the year of Mstislav’s death (1228), strife erupted anew in the principality of Galicia. Daniil and Köten found themselves in different camps. The prince sent an ambassador to the Khan with the following address: “O father! Turn away from this war and make peace with me.” Köten left the coalition arrayed against Daniil and left for “the Polovtsy lands.” Subsequently the prince and khan acted as allies in the endless internecine feuds. All of this allows us to draw a conclusion about the special status between Daniil and the Polovtsy, and explains why he took the Polovtsy horde under his protection in the mid 1240s.

In the winter of 1251-1252, Daniil marched on Lithuania with his brother Vasil’kij and his son Lev, “and with Polovtsy, along with the ambassador Tigak.” Daniil’s ambassador, of course, must have been from the royal family, perhaps a close relative of Köten. If so, then he could well have owned a gilt helm of Russian make or Daniil of Galicia’s Byzantine tunic, as described in the Chronicle, perhaps received as a wedding gift.

The reader has already certainly guessed our intention to test this theory: could Tigak be our Chingul’ khan?

Having twice raided Galico-Volynskij Rus’, both on the way to Hungary and back, but also having failed to capture Daniil himself, who had been warned by a faithful Polovtsy named Aktay, Batu entered into extensive negotiations with the prince. Conditions eventually required Daniil to journey, having first obtained a promise of safe conduct, to Batu’s headquarters on the Volga in 1246 and concede subjugation to the “patronage” of the Golden Horde. The Horde dramatically increased Daniil’s prestige in the eyes of European monarchs, who were afraid of new invasions by the Mongols. The following decade was marked by a series of military, political and diplomatic successes for the Galician prince. In 1254, the legate of Pope Innocent IV, Abbot Opizo, crowned Daniil. In those years, the prince held a fairly independent policy toward the Golden Horde, in any event, as the Chronicle notes, “not fearing Kuremsy” (the governor of the westernmost regions of the Horde). It was in those years that Daniil could afford to keep Tigrak in service to the Polovtsy.

Batu Khan died in 1255. Instead of the low-initiative Kuremsy, one of the best generals of the Chingizids, Burudaj-bahadur, arrived in the west with “a great force. In 1258, south-western Rus’ was fully incorporated into the sphere of Tatar-Mongol rule,” notes V. Pashuto. And what of the Polovtsy? The Chronicles do not mention anything further of them. In the opinion of several historians, they returned to the steppe under the auspices of the Golden Horde.

We mentioned only a few of the lurid events in the medieval history of the peoples of Eastern Europe of these three decades. In the cycle of endless wars, conspiracies and destruction when many cities were exterminated, along with entire peoples defending their honor and wealth, it is difficult to track the fate of a single person. We attempted this with all care, and came to the conclusion that in the Chingul’ mound is buried one of the Kötenovichi, most likely Tigak Khan.

In conclusion, starting in the 1240s, power over the Polovtsy steppe transferred completely into the hands of the Mongolian aristocracy. In the colorful phrase of G.A. Fedorov-Davydov, “under the dense row of Mongolian nomadic feudal lords in Desht and Kypchak, the old feudal nobility was no longer visible – it had lost its meaning.” The collection of items in the Chigul’ burial mound allows us to “discern” the remnants of a Polovtsy nomadic tribe which, judging by the archeological materials, had not yet been fully exterminated or evicted from the steppe. Interested in returning the Polovtsy to their own nomadic place in order to restore the economic order that was destroyed by the war, the leaders of the Golden Horde somehow made contact with the leaders of the Polovtsy emigration, making certain concessions. Tigak’s horde was no exception in this respect. In 1282, after the battle of Khood with the army of the Hungarian king Lazlo Polovtsov (himself, Köten’s grandson), part of the Polovtsy left to join the Golden Horde. Oldamur Khan led the Polovtsy army in this fight. P. Golubovskij writes, “in 1285, the Polovtsy together with the Tatars made an attack against Hungary and ravaged the whole country all the way to Pest.” Undoubtedly, the Polovtsy units in this army were led by their own leaders.

As we see, the historical information placed in the Chingul’ complex reveals itself to “perusal” and promises new discoveries.

A. Elkina, Restorer:

Over the last four years, we have extracted a lot of interesting information from the remnants of clothing preserved in the Chingul’ burial mound — mostly fragments of goldwork embroidery. We are employees of the State Research Restoration Workshop of the Ministry of Culture of the Ukrainian SSR. There are now no more “unknown objects” — all of the fragments have found their places in one of six kaftans decorated with goldwork embroidery and brocade bands. Of course, the clothes were not completely preserved, and we had almost completely decayed pieces; but, two of the six kaftans can be reconstructed in full detail.

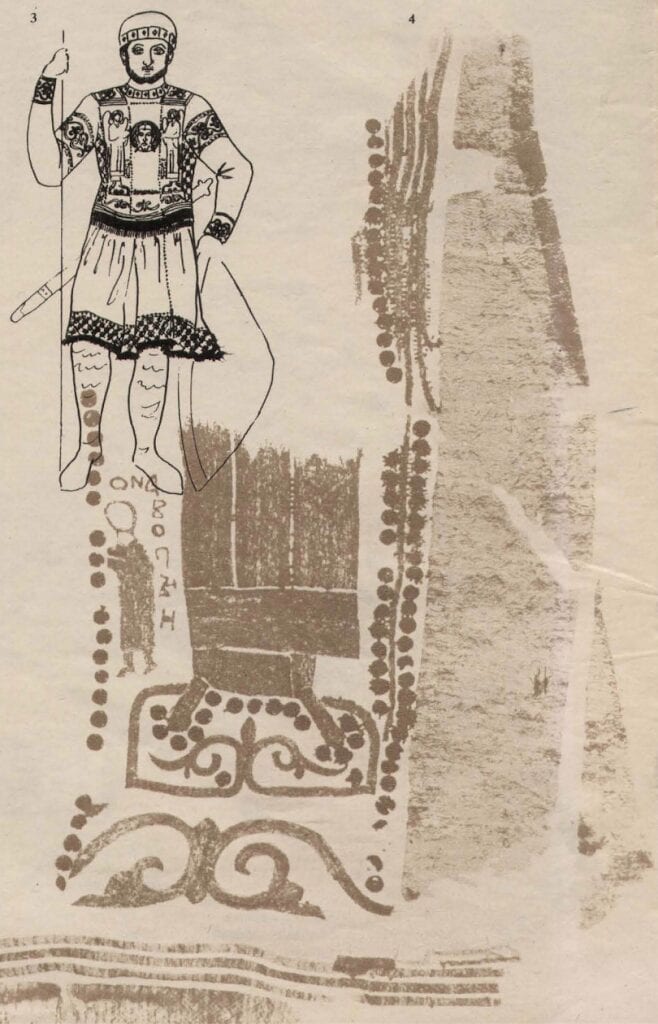

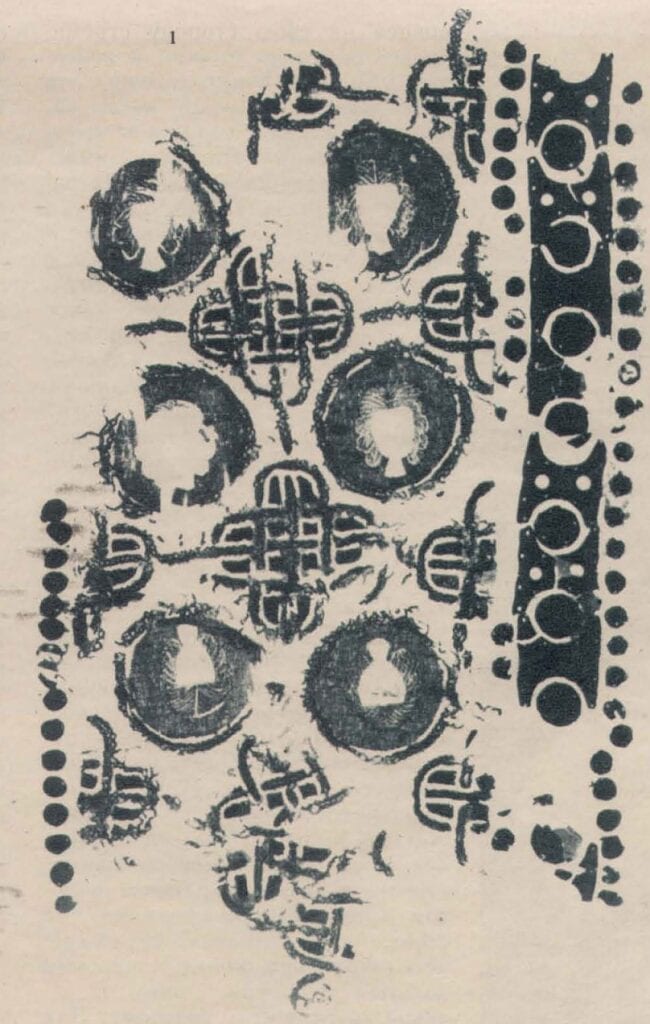

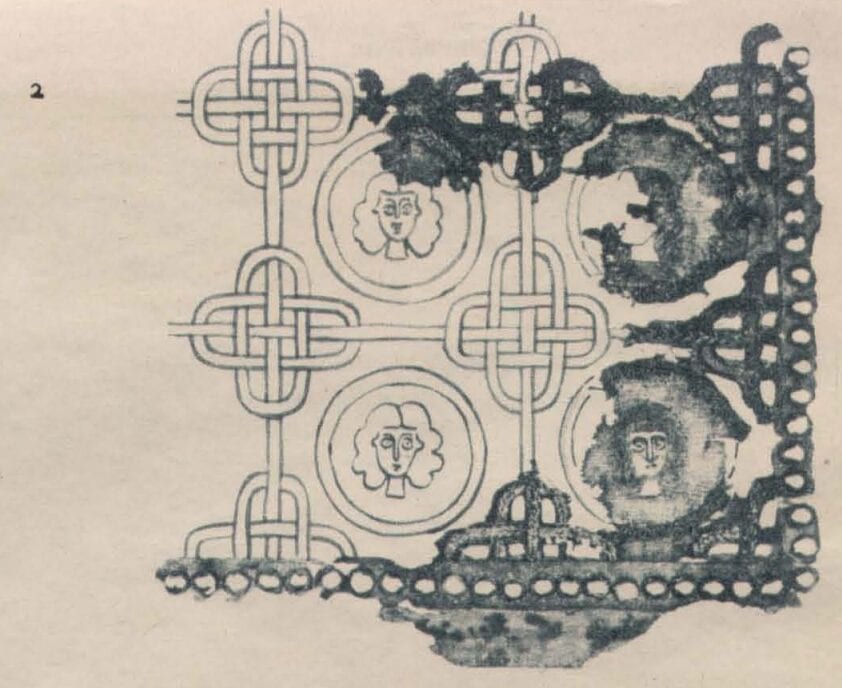

The first is the one in which the noble warrior was clothed. The kaftan was sewn from a thick, glossy crimson silk with inserts of goldwork embroidery on a dark blue foundation. An embroidered strip decorates the entire front, from top to bottom. Richly embroidered strips of embroidery run from the shoulders to the elbows, and bands of embroidery run around the ends of the sleeves. The ornament of all the details is the same: a grid with gold plaques at the intersections, and inside the cells are goldworked circles with the faces of angels or beautiful girls, enameled on Russian golden inserts. The kaftan collar and round headcap are lined with gilt plaques, decorated with gems. All of the patterns are decorated along the contours with tiny river pearls. Beneath is a gold-fabric band. There are not enough words to describe this outfit, it is so luxurious.

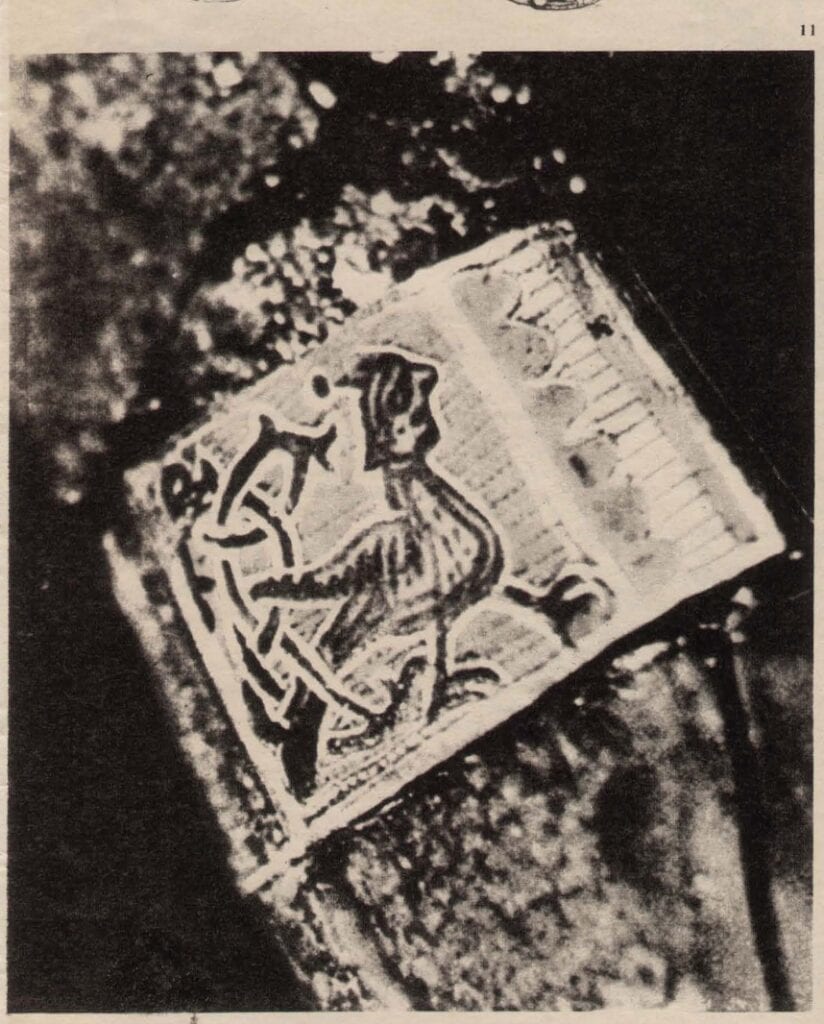

The second kaftan was more difficult to recreate. Recently, having reached some previously unidentified remnants, we discovered a small fragment of embroidery. Folds and concentric arcs were decorated with gold. Arcs — after all, this was part of a circle. We measured the diameter and realized that the circle was a halo! The halo was around the head of the Savior of Edessa. Of course, only the Savior could decorate the chest of a warrior. The Savior of Edessa was embroidered on the most ancient of Russian banners. One of them is preserved in the Armory.

This kaftan was just as luxurious as the first. But importantly, it differs by having a Slavonic inscription upon it: “[I]ona vopyj” – “Screaming Jonah” (per B.I. Marshak).

What can be said about this noble warrior’s clothing? It is all sewn from expensive imported materials – silk fabric from Constantinople and wrapped golden threads of Byzantine production. But the work – goldwork embroidery trimmed with pearls, the ornament, and the Slavonic inscription – are of medieval Russian origin. Similar items are known from celebrated Russian treasuries from pre-Mongolian times. These clothes were designed by artists and carried out by skilled craftsmen in the courts of the great Russian princes shortly before the invasion.

![Complete reconstruction of the first kaftan from the Chingul Kurgan, made by A. Elkina on the basis of her extensive research; X-ray of goldwork embroidery on the second kaftan. To the left can be seen the inscription: "[I]ona vopyj."](https://b2058619.smushcdn.com/2058619/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Screen-2BShot-2B2019-02-01-2Bat-2B10.50.40-2BPM-658x1024-1.jpg?lossy=0&strip=1&webp=1)

3. Complete reconstruction of the first kaftan, made by A. Elkina on the basis of her extensive research; 4. X-ray of goldwork embroidery on the second kaftan. To the left can be seen the inscription: “[I]ona vopyj.”

S. Vysotskij, Doctor of Historical Sciences:

My opinion diverges a bit from that of other historians and of Alla Konstantinovna Elkina. Judging by the theme of the imagery on the second kaftan (or more correctly, on the vestment), the clothing was created in full or at least in part in one of the medieval Russian monasteries by order of a certain Iona — a wealthy individual, possibly a royal individual named for his godfather. The clothes were given by him as a gift to a church in one of the cities in southern Rus’ near the Polovtsy steppe. As a result of nomad raids on the city and plunder of the church, the vestments fell into the hands of the khan and were buried with him.

And, what new information can our science teach us from the discovery of the fabric with the inscription? Together with information on the development and distribution of writing in Rus’, received as a result of the study of birch bark letters from Novgorod and graffiti in Kiev, the inscription on the fabric sheds light on yet another facet of the cultural development of Rus’ — the history of medieval Russian embroidery. It proves that in pre-Mongol times, medieval Russian embroideresses achieved great skill in their art, and also that some of them were literate.