I have been looking into making a Russian style kaftan for my SCA persona, and came across this interesting article which discusses the theories on how the kaftan came to medieval Rus’ and Scandinavia, and its possible origins in Iran, Central Asia, Byzantium, or the Caucasus. This gives an overview of the kaftans depicted in the art of each of those areas, and compares them to the kaftan finds (mostly just buttons), illuminations, and other representational art depicting early-period Russians in kaftan-like garments. This has a great picture of the buttons that were commonly used on Rus’/Viking kaftans in the 9th-11th centuries, as well as some great pics for inspiration to work on my next project – trying to cast up some buttons, while I wait for my silk to arrive!

Eastern-Style Medieval Russian Kaftans (fashion, origin, chronology)

A translation of Михайлов, К.А. «Древнерусские кафтаны “восточного” типа (мода, происхождение, хронология).» Вестник молодых ученых. Серия: Исторические науки. 1 (2005), с. 56-65. / Mikhajlov, K.A. “Drevnerusskie kaftany ‘vostochnogo’ tipa (moda, proiskhozhdene, khronologija).” Vestnik molodykh uchenykh. Serija: Istoricheskie nauki. 1 (2005), pp. 56-65.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

General Overview

Scholars of costume will often admit that our understanding of medieval Russian clothing are often fragmentary and insufficient for detailed reconstruction. Our understanding is primarily based on works of figurative church art (icons, frescoes, manuscript illuminations), or on manuscript descriptions which are short on details. Often, pictorial sources may reflect centuries of church iconographic tradition, which may exist, in light of a generally-accepted canon, significantly longer in those depictions than a given type of clothing may have actually existed in reality. As a result, works of pictorial, most often ecclesiastic, art cannot always serve as the basis for reliable reconstruction of historical costume.[1]Rabinovich, M.G. “Drevnerusskaja odezhda IX-XIII vv.” Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy. Moscow, 1986, pp. 40-41; Saburova, M.A. “Drevnerusskij kostjum. Odezhda.” Drevnjaja Rus’. Byt i kul’tura. Moscow, 1997, p. 97.

This statement is especially true for the earliest period of medieval Russian history, the 10th and 11th centuries. At this time, the majority of sources on 10th-11th century medieval Russian costume consist of archeological data: fragments of clothing or fabric, jewelry and fittings, discovered in medieval Russian burials or in locations of medieval settlements.[2]Rabinovich, op. cit., pp. 40-41; Sedov, V.V. “Odezhda vostochnykh slavjan VI-IX vv.” Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy. Moscow, 1986, pp. 30-39. In this situation, where our concepts about medieval costume are based on its surviving metal decorations, other details about the costume itself become rare, or even unique. However, of greater value is a series of examples which belong to one type of clothing. They allow us to reconstruct a “typical” and quite widespread type of costume, based not only on individual details which happen to have survived. A series of these remnants of outer men’s wear, all similar to one another, have been discovered in a series of early medieval Russian burial mounds.

Among 10th-century medieval Russian burials, the most detailed information about remnants of clothing can be obtained from inhumed burials. Among these, the richest and most diverse inventory comes from burials performed using wooden burial chambers.[3]Lebedev, G.S. “Sotsial’naja topografija mogil’nika epokhi vikingov v Birke.” Skandinavskij sbornik. Iss. XXII. Tallin, 1977, pp. 151-156; Zharnov, Ju.E. “Zhenskie skandinavskie pogrebenija v Gnezdove.” Smolensk i Gnezdovo. Moscow, 1991, pp. 217-220; Graslund, A.S. “The Burial Customs. A study of the graves on Bjorko.” Birka IV. Stockholm, 1980, pp. 79-82. Burial chambers were discovered in many Scandinavian and medieval Russian burial mounds from the Viking era. The majority of scholars are of the opinion that these burials are of northern European aristocrats. In these medieval Russian burial chambers, remnants of clothing and their metallic decorations frequently remain in the same location where they were laid during the burial ceremony. Similar placement [across these burials] allows us to reconstruct the types of clothing based on the location of these metallic items and fragments of fabric.

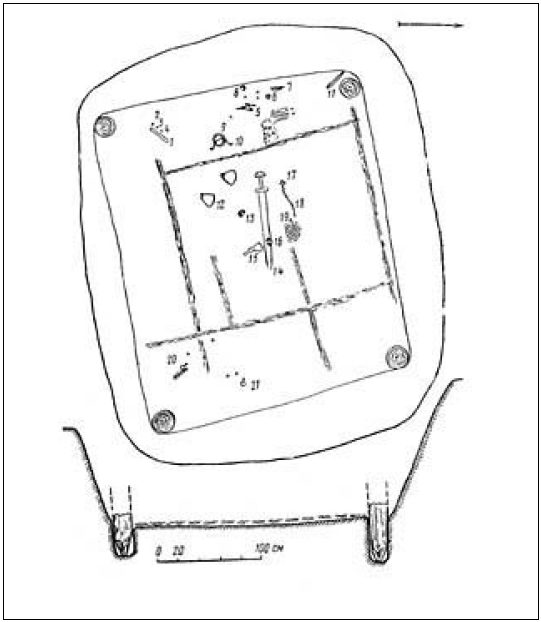

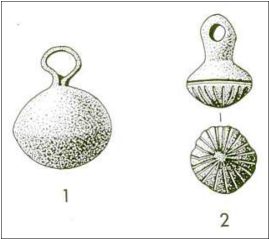

First of all, we should mention the remnants of men’s clothing examined in burial mound DN-4 from Gnezdovo, near Smolensk. At the bottom of the grave pit, there lay in situ fragments of two rows of narrow silk braid, comprising something like a breastplate 36 cm long, and a series of 24 bronze, mushroom-shaped buttons with eyelets for attachment (illustration 1). Scholars suggested that these surviving items once belonged to an item of men’s outerwear, similar to a kaftan.[4]Avdusin, D.A., Pushkina, T.A. “Tri pogrebal’nye kamery iz Gnezdova.” Istorija i kul’tura dreverusskogo goroda. Moscow, 1989, pp. 198, 201, illus. 3; Fekhner, M.V. “Tkani iz Gnezdova.” Arkheologicheskij sbornik pamjati M.V. Fekhner. Trudy GIM. No. 111. Moscow, 1999, p. 8. In another Gnezdovo burial, in a chamber from burial mound Pol’-62, archeologists found fragments of silken braid similar to that from mound DV-4. M.V. Fekhner noticed that the fabric from this chamber was red silk with a printed green pattern. Aside from these fragments, in Pol’-62, a narrow band woven from silk and silver threads (fragment length 2.5-18 cm, width 0.9 cm) had survived. The grave also contained “a fragment of the thinnest silk which, along with a glass button, may have been remnants of an under shirt.” This silk fabric, in Fekhner’s opinion, was of Byzantine origin.[5]Kamenetskaja, E.V. “Zaol’shanskaja kurgannaja gruppa Gnezdova.” Smolensk i Gnezdovo. Moscow, 1994, pp. 151, 171-172, illus. 7, 3-5; Fekhner, op. cit., p. 8.

The remains of men’s clothing from these burials in Gnezdovo have several characteristic peculiarities which allow us to compare these finds with others where fabrics were preserved less well. First of all, it is common for them to have metallic braid, or of silk bands woven with silver or gold threads, or cut from silk fabric. Secondly, an essential detail for this type of clothing was a row of identical mushroom-shaped bronze buttons, decorated with notches (see illustration 2, 2). The location of these buttons indicates that the garment was fastened to the waist, but was apparently unfastened below the waist. Thirdly, fragments of silk fabric are frequently found along with this collection of buttons. It should particularly be noted that in the early Middle Ages in Northern Europe, outer and inner clothing was fastened using special clasps with pins, called fibulae. These were used to pin the edges of clothing, most frequently cloaks and shirts. It seems that, against this widespread distribution of fibulae, clothing fastened using buttons would have appeared quite exotic in the forested regions of Eastern Europe.

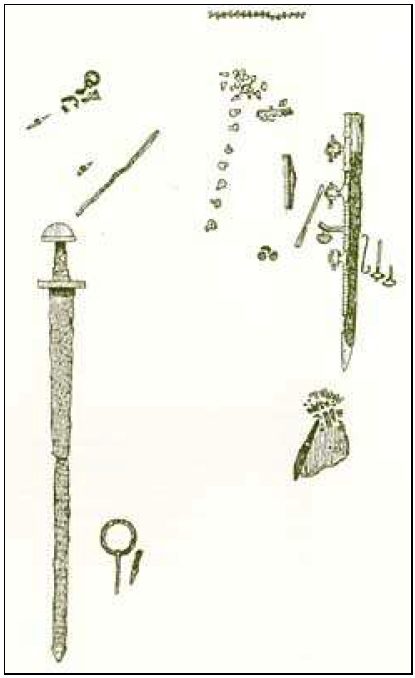

The closest analogies to the remnants of men’s clothing uncovered in the Gnezdovo burials come from several burials in the earliest of medieval Russian burial mounds and from the burial chamber of a Swedish grave in Birka. Swedish scholars call all of these remains of outer, flowing men’s clothing fastened with bronze buttons and decorated with braid “Eastern kaftans.”[6]Hägg, I. “Die Tracht.” Birka II:2. Systematische Analysen der Graberfunde. Stockholm, 1986, pp. 68-69; Jansson, I. “Wikingerzeitlicher orientalicher Import in Skandinavien.” Bericht der Romisch-Germanischen Kommission. Bd. 69. Mainz am Rhein, 1988, p. 594. Fragments of these “Eastern kaftans,” which were quite similar to the Gnezdovo finds, as well as buttons were discovered Birka graves no. 716, 752, 944, 985 and 1074.[7]Graslund, op. cit., p. 13. These burial sites contained from 4 to 18 bronze buttons, which lay in a single row from the skull to the lumbar region of the deceased (illustration 3). The distance from the top to the bottom buttons measured 10-15 cm (4 buttons) in chamber 985, and from 38-40 cm in chamber 752, where 10 buttons were found.[8]Arbman, H. Birka I. Stockholm, 1940-1943, p. 273, 411, Illus. 221, 365. In grave No. 716, perfectly in the grave, the distance from the first to last button measured around 20 cm (below was there was a belt, decorated with plaques, and remains of a pouch). In chamber No. 752, the buttons lay in a row around 38-40 long from the fibula (at the deceased’s throat) to the belt buckle. In no. 944, the buttons lay in a row from the remains of the skull for a distance of 28-30 cm. In no. 985, the buttons ran to a belt decorated with plaques, for a length of 30-34 cm. Aside from these burials where the buttons were found in situ, analogous bronze buttons (8 in number) were found in the burnt remains of grave no. 56. In chamber no. 985, four massive bronze buttons lay lay along the male’s spine, for a distance of 10-15 cm. In grave no. 949 of the Birka burial ground, three such buttons served to fasten a pouch with bronze fittings (the closest analogies to this type of pouch are from a burial mound in Volga Bulgaria and the Timerevo burial mound) (cf. Arbman 1940 op. cit., Table 128, 2). In grave No. 1105 of a woman, one bronze button with a tab lay alongside glass beads near the lower jaw of the deceased (from a shirt or collar). Aside from Birka, bronze mushroom-shaped buttons were discovered in Uppland, on the islands of the Aland archipelago, and in Southern Finland. However, these discoveries were most likely not associated with finds of “Eastern-style kaftans” (cf. Jansson, op. cit., p. 606). Along with these buttons, fragments of gold and silver braid which bound the edges of the garment were also found.[9]Jansson, op. cit., pp. 594, 606. Outside Birka, in central Sweden/Svealand, men’s kaftans with buttons and loops seem not to have been in use. These identical buttons, the presence of braid, bands, and of course the cut are all a characteristic peculiarity of costume which points to a singular fashion for both the Birka and medieval Russian examples. As the majority of these finds were associated with Birka’s late chronological phase, they can be dated to the late 9th-10th centuries. It appears that fragmentary memories of this style were preserved in Viking-era Scandinavian sagas. For example, in the Icelandic Egil’s Saga, there is a mention of the fashion of the famous Scandinavian’s clothing. Around 940-960 in Anglia, Egil Skallargrimson, the leader of a band of Vigings and wealthy landowner, was gifted “a long garment, made of silk, with a gold border and with golden buttons down to the hem.”[10]“Saga ob Egile.” Islandskie sagi. Moscow, 1956, p. 205. It is worth considering that the most widespread type of men’s wear in Northern Europe and Anglia during this time was the undertunic and cloak.

The solid buttons from these “Eastern kaftans” in the Birka and medieval Russian 10th-century necropolises had a characteristic mushroom shape and round eyelets for attachment. These details allow us to differentiate this type of cast button from spherical tabbed buttons and other later styles of metallic tabbed buttons. However, in the following century, bronze buttons of another type became even more widespread – spherical or mushroom-shaped buttons with a more elongated form (illustration 2, 1). For example, archeologists uncovered in Kiev several medieval casting molds used for casting these spherical buttons.[11]Shovkopljas, G.M. “Arkheologichni pam’mjatki gori Kiselivki v Kievi.” Pratsi kiivsk’kogo derzhavnogo istorichnogo museju. Iss. 1. 1958, pp. 147-148, plate 5, 9, 12; plate 6, 7. According to our data, grooved mushroom-shaped buttons were not widely used in later centuries. At the same time, the complex shape of these buttons is reminiscent of the shape of pendant seals from Byzantine cities. A few similar bronze buttons were discovered in the region of Constantinople and in excavations of Byzantine Corinth.[12]Archaologisches Museum, Istanbul, No. 6867 (cited in Jansson, op. cit., p. 607). These finds were associated with a form of clothing from Northern Europe, fastened with fibulae, for which fastening with buttons became a common detail.[13]These were used to fasten the collar of a shirt, but most often sets of such buttons were associated with men’s outerwear. In a series of medieval Russian burials, traces of such garments were recorded, which differ in their features from the majority of those buried in early medieval Russian gravesites. This costume can be traced especially clearly in complexes with cadavers, where remains of fabric and bronze buttons are recorded directly on the bones of the deceased. A distinctive feature of this garment are the bronze mushroom-shaped buttons located along the spine of the deceased from the chest to the pelvis. A majority of similar finds were made in male graves or in graves containing men’s items. In the literature, this type of garment is called “a kaftan” and its origin is deduced to be from Central Asia or Iran. Various styles of kaftan were in use among the Asiatic nomadic tribes (cf. Samashev, Z.S. “Odezhda i pricheski credevekovykh nomadov.” Kul’tury Evrazijskikh stepej vtoroj poloviny I tys. n.e. (Voprosy khronologii). Samara, 1998, pp. 406-408). Finds of entire early medieval kaftans fastened with buttons were associated with the well-known northern Caucasus burial at Moschevaja Balka (cf. Ierusalimskaja, A.A. Kavkaz na shelkovom puti. Katalog vremennoj vystavki. St. Petersburg, 1992). Depictions of similar outfits can be seen in Sogdian murals, Turkic stone steles, and in the Menologion of Basil II in the scene of the abuse of Byzantine prisoners of war by the Bulgarians. Aside from the bronze, mushroom-shaped buttons, kaftans were also fastened using bone buttons. A set of similarly-decorated, hemispherical bone buttons were found in the Gul’bische burial mound in Chernigov. Meanwhile, it seems that some bronze mushroom-shaped buttons were not associated with kaftans. This is especially true for burial complexes where fewer than 3 buttons were discovered. The closest example is seen in data from medieval Russian burials from the 11th-13th centuries, where 1-3 buttons were recorded in use to fasten standing collars on men’s and women’s shirts (Saburova, M.A., Elkina, A.K. “Detali drevnerusskoj odezhdy po materialam nekropolja g. Suzdalja.” Materialy po srednevekovoj arkheologii Severo-Vostochnoj Rusi.” Moscow, 1991, pp. 54-62; Saburova, M.A. Drevnerusskij kostjum. Odezhda.” Drevnjaja Rus’. Byt i kul’tura. Arkheologija. Moscow, p. 100.)

A characteristic and meaningful detail of the clothing which scholars call “Eastern-style kaftans” is the number of fastenings. At a minimum, they number no less than 4-6, but most frequently number as high as 8-12 buttons. To the collection of kaftans, it seems, we should attribute only those complexes in which 10 or more bronze buttons were discovered. An exception is that we should include the finds from a burial in the medieval Russian burial ground at Guschino near Chernigov. Judging by the location of the six buttons on the skeleton and the type of burial, this grave also contained a garment of the kaftan-type. In all, in my opinion, no fewer than 11 medieval Russian graves should be included in the list of complexes containing kaftans, where bronze buttons were preserved in situ along the spine running from the skull to the belt. This list of complexes includes: a burial from the Guschino burial ground near Chernigov; burials no. 36, 42, 61.4 and 98 from the Shestovitsa burial ground; burials Ts-157, Dn-4, L-129, Pol’-11, and Pol’-62 from Gnezdovo.[14]Borovs’kij, Ja.E., Kapljuk, O.P. “Doslidzhennja kiivs’kogo Ditintsja.” Starodavnij Kiiv. Arkheologichni doslidzhennja 1984-1989 gg. Kiev, 1993, pp. 3-8; Somosvasov, D.Ja. Mogil’nye drevnosti Severjanskoj Chernigovschiny. Posmertnoe izdanie. Moscow, 1917, pp. 77-80; Rybakov, B.A. “Drevnosti Chernigova.” MIA, 1949 (11), p. 22; Blifel’d, D.I. Davn’orus’ki pamjatki Shestovitsi. Kiev, 1977, pp. 128-131, 138-141, 151-155; Stankevich, Ja.V. “Shetovitskoe poselenie i mogil’nik po materialam raskopok 1946 g.” KSIIIMK. 1962 (37), pp. 23-27; Zharnov, Ju.E. op. cit., pp. 208, 210-211; Avdusin, Pushkin, op. cit., pp. 196-200; Kamenetskaja, op. cit., pp. 165, 171-172. It is particularly worth noting that the sets of buttons from kaftans, to date, have not once been found in “common” burials in 10th century pits or coffins, which exist in large numbers in the burial grounds from Gnezdovo, Shestovitsa and in the medieval Russian necropolises in Kiev. Likewise, signs of kaftans have not been found in such rich burial grounds in the upper Volga such as Timerevo or Mikhajlovskoe. Signs of kaftans likewise were found found in the burial grounds of Gotland, where large quantities of medieval Russian items have been found. Bug, if the lack of kaftan finds in Northern Rus’ can be associated with the peculiarities of northern dress, their absence on the island of Gotland can most likely be associated to chronological factors. The main import of medieval Russian goods to Gotland began only in the 11th century. As a rare exception, we should also note a burial from a Kievan necropolis, where in funerary chamber no. 114, three buttons were found on the chest of a male.[15]Karger. M.K. Drevnij Kiev. Vol. I. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958, p 187, illus. 34. In this case, the number of buttons corresponds to the number on the kaftans from Moschevaja Balka. It is possible to suppose that the garment in this chamber differed from the “traditional” medieval Russian kaftans of the 10th century. It seems that 9 mushroom-shaped buttons preserved in burial chamber no. 1 from the excavation on Great Zhitomirsky Street in the same necropolis were also from a kaftan.[16]Borovskij, Ja.E., Kaljuk, A.P., Syromjatnikov, A.K., Arkhipov, E.I. Arkheologicheskie issledovanija v ‘Verkhnem Kieve’ v 1988 godu.” NA IA NANU. no. 1988(17), pp. 5-12; Borovs’kij et.al., op.cit., pp. 3-8. Four of the richest burial chambers in the Shestovitsa burial ground (no. 36, 42, 61.4, 98) released 11 to 45 buttons each.[17]Blifel’d, op. cit., p. 43. In burial mound no. 145, 8 bronze buttons were found in the funerary pyre built atop the wooden burial chamber, together with a rider’s clothing set.[18]Blifel’d, op. cit., pp. 188-189. In Shestovitsky burial no. 61.4, the buttons (26 examples) lay from the upper ribs to the pelvic bones of the deceased, running a distance of about 40 cm. Below the buttons, there were fragments of a belt pouch. Burial mound no. 98 contained silk fabric with braid and bronze buttons on the deceased’s chest, as well as beside him. It appears that this burial may have contained two kaftans. The fact that the buttons were sewn one atop the next was registered in several burial chambers where even remains of linen and silk fabric were preserved.[19]Stankevich, op. cit.; Androschuk, F.O. Normani i slov’jani u Podesenni (Modeli kul’turnoj vzaemodii dobi rann’ogo seredn’ovichchja). Kiev, 1962, p. 65, illus. 43, 47. By analogy to these burials where certain numbers and positions of buttons have been recorded, buttons of the same shape and quantity from medieval Russian cremations can also be attributed to the same type of garment.

Aside from burials, the characteristic number of the same mushroom-shaped, cast bronze buttons are also seen from medieval Russian cremations. For example, in 7 Gnezdovo complexes with individual burials of men using cremation, 4 to 10 mushroom-shaped buttons were found (Serg-5 (55), Pol’-25/I, L-17, 22, 69, 103, Ts-106).[20]Zharnov, op. cit., p. 211. The same was also seen in cremations from V.I. Sizov’s excavation of a grave mound in Gnezdovo (burial mounds no. 15, 17, 65, 122), which revealed 4-6 buttons each.[21]Shirinskij, S.S. “Ukazatel’ materialov kurganov, issledovannykh V.I. Sizovym u d. Gnezdovo v 1881-1901 ff.” Trudy GIM Pamjatniki kul’tury. 1999 (36), pp. 103, 117, 120-121, 127; Blifel’d, D.I. “Drevn’orus’kij mogil’nik v Chernigovi.” Arkheologija. 1965 (XVIII), pp. 105-138, 123, plate IV, 12-15. In a cremation burial from mound No. 16 in a Chernigov burial ground “in an old cemetery in Berezki,” 6 of these buttons lay in a row directly atop the spin, in the location of the burnt clothing.[22]Blifel’d, op. cit., p. 117. 17 more bronze buttons were found along the spine in burial mound no. 15 from the same necropolis.[23]Blifel’d, op. cit., p. 131. In the looted burial chamber no. 17 from “the old cemetery in Berezki,” 2 bronze buttons were discovered, which fell off when the graverobbers pulled the deceased’s body to the surface.[24]In my opinion, a burial from a large burial mound in Gul’bische in Chernigov can be considered as an exception from this list of complexes. This is the only 10th century complex where numerous buttons were made from bone, rather than bronze. The clothing set in this grave revealed 9 hemispherical ornamental buttons, which most likely belonged to a kaftan. This theory is supported by the number of buttons, as well as their central Asiatic or Iranian origin (cf. Put’ iz varjag v greki. Katalog. Moscow, 1996, p. 80, no. 696.). Numerous finds of similarly decorated buttons have also been seen from the medieval cities of Central Asia and Azerbaijan. The largest number of finds of these hemispherical bone buttons with circular designs come from the 10th century layers from the village of Khorezm (cf. Vishnevskaja, N.Ju. Remeslennye izdelija Dzhigerbenta (IV do n.e. – XIII v.n.e.). Moscow, 2001, pp. 105-108, illus. 42, 1-15, 45, 11-14; Akhmedov, G.M. “Azerbajdzhan v IX-XIII vv.” Krym, Severo-Vostochnoe Prichernmor’e i Zakavkaz’e v epokhu srednevekov’ja IV-XIII veka. Arkheologija. Moscow, 2003, p. 381, plate 192, 8-20). A Sednevsk medieval Russian burial ground had three 10th century graves which contained 8, 10, and 35 buttons.[25]In addition, these buttons were found in medieval layers of the Byzantine city of Corinth.To date, 10th century medieval Russian burial grounds have revealed the remnants of no fewer than 12 Eastern-style kaftans from inhumations, and no fewer than 16 from cremations.

This given list of finds, in my opinion, clearly demonstrates that the distinctive feature of 10th century medieval Russian kaftans was the numerous bronze buttons in the characteristic mushroom shape. Sometimes they were positioned in a continuous strip every 1.5 cm (or more often, every 4-5 cm), giving the garment a certain smartness. Judging by the surviving details, the narrow silk braids which decorated the eyelet-clasps at each button were also positioned at the same rate. These braids were sewn to the garment parallel to one another, and parallel to the belt. Sometimes, this braid was also used to bind the edges of sleeve cuffs or the edges of the garment. This characteristic detail differentiates medieval Russian finds from the well-known kaftans discovered in the grave site from Moschevaya Balka. The latter were not as frequently decorated with buttons and braid. They had 2-4 small buttons decorated with 3-4 pairs of silk braid.[26]Ierusalimskaja, op. cit., pp. 14-15, illus. 1-2, photo 9.

In addition to the remains of kaftans discovered along with the remains of the deceased, in several chambers, fragments of silk garments with bronze buttons were found to one side of the body. It appears that these were remains of an additional set of burial clothing, which were buried alongside the departed. These adidtional sets of kaftans were found in Gnezdovo grave Pol’-11 and in Shestovitsa burial mound no. 98. It can be assumed that this set of clothing is similar to the one that the deceased was dressed in for burial. Ibn-Fadlan describes the process of dressing up a deceased Rus’ warrior during the funeral rites in one or the other set of garments. He recalls that before the Rus’ warrior was cremated, he was dressed in a kaftan with “golden” buttons which had been sewn especially for this occasion.[27]Krachkovskij, I,Ju. Puteshestvie Ibn-Fadlana na Volgu. Moscow-Leningrad, 1939, pp. 80-81. However, it remains unclear what type of clothing Ibn-Fadlan had in mind. It should be noted that in medieval Persian sources, the word “kaftan” often denoted a type of armor covered in fabric.

One of the most important problems associated with archeological finds of medieval Russian kaftans is that of the origin of this type of clothing. What range of finds and pictorial sources can be compared to the medieval Russian discoveries? There are various theories about the origin of this type of clothing which, in my opinion, can be reduced to several basic versions. These versions may be conventionally designated by their cultural/geographical nature: Turkic-Sogdian, Iranian, Steppe or Khazar-Alan, Hungarian, and Bulgaro-Byzantine.

The Turkic-Sogdian Theory

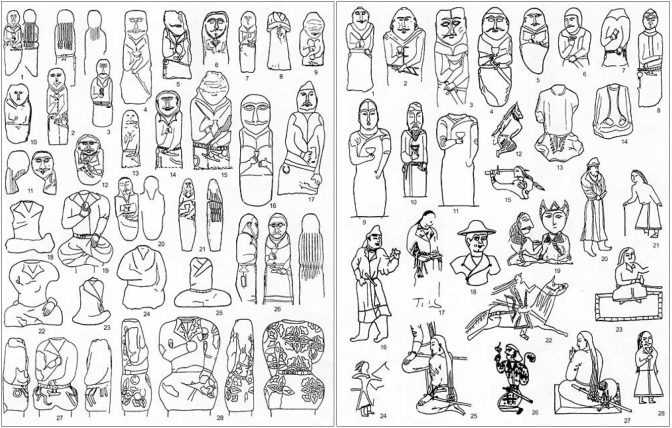

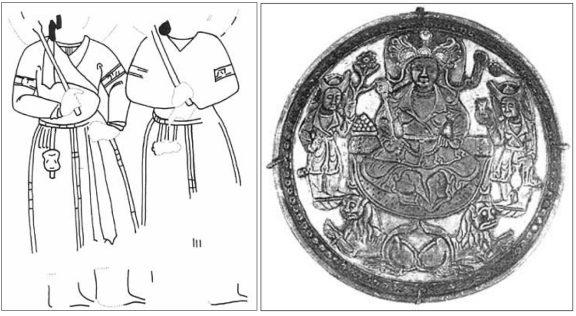

Scholars of medieval Turkic costume have to this date not yet come to a singular set of terminology to describe one and the same depictions of clothing. For example, one and the same item of outer men’s wear may be called a khalat or a kaftan. In truth, this confusion in terminology is associated with the fact that the outfits shown on medieval Turkic statues from Central Asia may be traced to a minimum of two types of outer wear.[28]Kubarev, G.B. “Khalat drevnikh tjurok Tsentral’noj Azii po izobrazitel’nym materialam.” Arkheologija, etnografija i antropologija Evrazii. No. 3 (3). Novosibirsk, 2000, pp. 81-85. Only one of these may be called a khalat. Most often this has a left-sided, deep wrap-over, where the outer, usually right side lies over the left and is fastened at the side or is cinched closed with a belt (see illustrations 4, 5).[29]Kubarev, op. cit., p. 85, illus. 1, 8, 23, 25, 27, illus. 3, 9, 10, 11, 18.

A second, less widely-distributed type of outerwear worn by Turkic nomads had a deep neckline with triangular open lapels, a straight axial opening from the collar to the hem, and narrow sleeves. This variant of men’s clothing was slightly fitted and fell to below the knee.[30]Kubarev, op. cit., illus. 1, 2, 17, 19, illus. 2, 3, 4, 34, illus. 3, 2, 16, 17, 28. On some Turkic statues, it is notable that this type of clothing was fastened down to the belt with button fasteners, but was freely open below the belt (illustrations 4.2, 5.2).[31]Kubarev, op. cit., illus. 1, 2, illus. 2, 4, illus. 3, 2. It appears that this second type of medieval Turkic outerwear can be considered as a prototype for the kaftans from Moschevaya Balka. A few earlier analogies to this type of costume can also be traced to Eastern Turkestan. For example, on 5th-8th century fresco paintings from Kucha and Khotan, the men’s kaftans worn by nobility have a front opening and triangular lapels.[32]Jatsenko, S.A. “Kostjum.” Vostochnyj Turkestan v drevnosti i rannem crednevekov’e. Arkhitektura. Iskusstvo. Kostjum. Moscow, 2000, pp. 332-333, plate 35, 1-3, 5, plate 60, 1-2. The medieval costume worn by the Uighurs of Turfan also preserved these two variants of outerwear for a long time: the khalat with its wide wrap-over, and the kaftan-khalat with the frontal opening in the middle and an outlandish standing collar.[33]Jatsenko, op. cit., p. 370, illus. 67, 1-3, illus. 69, 1-3; Kljashtornyj, S.G. Istorija Tsentral’noj Azii i pamjatniki runicheskogo pis’ma. St. Petersburg, 2003, p. 374.

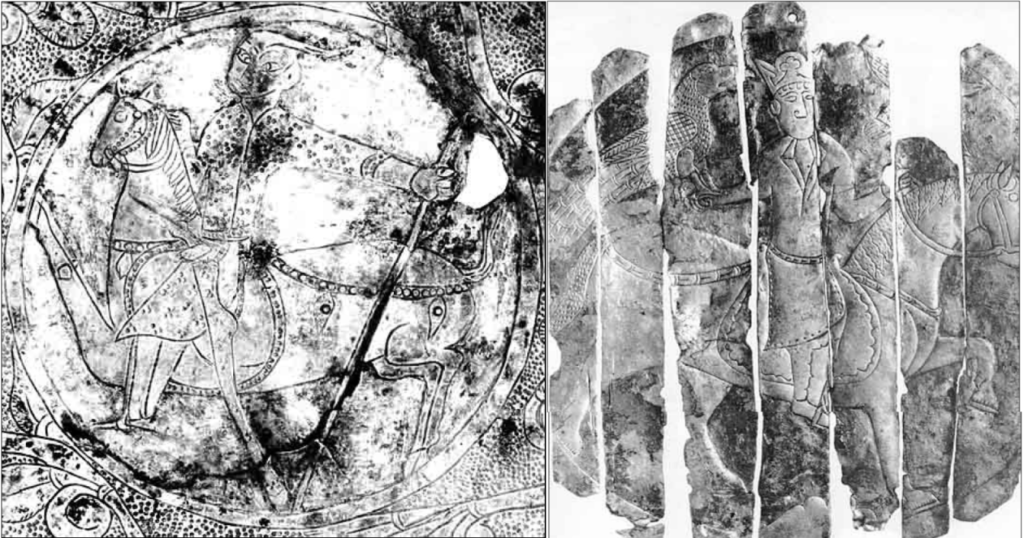

The latest, by time period, depictions of medieval nomads in kaftans with lapels were found on silver dishes originating from the Lower Ob region.[34]Sokrovischa Priob’ja. Katalog vystavki. St. Petersburg, 1996, pp. 114-117, 120-121, No. 53, 55. These finds date to the 9th-10th centuries and are traditionally attributed to be toreutic works by the ancient Hungarians. On one dish, a raider is shown in a long, open kaftan with a front opening and no lapels (illustration 6).[35]Sokrovischa Priob’ja, op. cit., p. 116. The other shows a rider in a kaftan with triangular lapels and a right-sided wrap-over (illustration 7).[36]Sokrovischa Priob’ja, op. cit., p. 121. While the first depiction is reminiscent of the finds from Moschevaya Balka, the second depiction is closer to the Turkic stone statues from Central Asia. Of course, the early medieval Turkic kaftan survived amongst the nomads right up until the 9th century, and its cut may have served as the basis for numerous imitations. It seems to us that it cannot serve as a direct basis for the medieval Russian forms of the kaftan due to the lack of buttons, braid, and a series of other characteristic details.

The Steppe or Khazar-Alan Theory

The “steppe” or “Khazar-Alan” version of the medieval kaftan can be considered as a derivative from the Turkic form. The basis of this version lies in the assumption made by several scholars that a similar type of clothing would have been quite convenient for riding horseback and that it may have been borrowed for this purpose by the Old Russian elite.[37]Gorelik, M.V. “Obraz muzha-voina v Kabarii-Ugrii-Rusi.” Kul’tury Evrazijskikh stepej vtoroj poloviny I tys.n.e. (is istorii kostjuma). Samara, 2001, p. 176. The finds of silk kaftans from the central-Caucasus burial site of Moschevaya Balka serve as support for this theory. Just as this monument clearly influenced Saltovo-Mayatsky culture, so too can the cut of the kaftans from this burial mound be associated with the culture of the steppe nomads which was dominant in this region. However, the absence of such important attributes as a multitude of bronze buttons and braid made from metallic thread serves as an argument against this assumption. Similar mushroom-shaped buttons have also not, to date, been found in materials from the steppe Saltovo-Mayatsky culture. In turn, the kaftans with lapels depicted on Turkic stone steles and Sogdian murals had only one internal button. Internal buttons were found on several of the kaftans from Moschevaya Balka (illustration 8). However, the majority of kaftans from this burial site had no more than 4 buttons, which were made from organic materials, a feature that is not seen on medieval Russian kaftans.

The Hungarian Theory

The “Hungarian” theory of the origin of the kaftan in Europe can be considered to be a derivation of the Turkic theory. It is associated with finds of bronze, mushroom-shaped buttons which, albeit rarely, were found in medieval Hungarian grave sites. In a series of cases, they were recorded in the components of attire among female burials from the “era of finding the Homeland.”[38]Jansson, op. cit., p. 606. The location of the bronze buttons in deceased’s remains in Hungary differs somewhat from the location of buttons in medieval Russian burials. Quite a few of these individual buttons were found in Hungarian burial mounds from the 10th century located in South-Western Slovakia, not far from the Carpathian passes, along the border of the medieval Russian state. For example, in the Sered I burial ground, mushroom-shaped buttons lay along the deceased’s spine, not in a single row, but rather in two rows of 6 buttons each.[39]Tocik, B. “Altmagyarische graberfelder in der sudwestslowakei.” Archaeologica Slovaca. Vol. III. Bratislava, 1968, p. 43, Plate XXXIV:9.

The Iranian Theory

The Iranian theory for the origin of “Eastern-style” kaftans was proposed and substantiated in detail by I. Jansson for finds from the Swedish burial ground at Birka. This scholar believed that the cut of the Birka kaftans was similar to depictions of outerwear on Ghaznavid guards or ghilman seen in frescoes from the palace in Lashkari Bazaar (illustration 9).[40]Jansson, op. cit., p. 602, plate 18. These depictions are not unique. They have parallels in images from medieval Iranian toreutics. For example, an early 11th century dish discovered in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District depicts Prince Mahmoud Ghaznevi on a throne, with two courtiers at his side. The prince and his couriers are dressed in khalaty with wide, right-sided wrapovers and triangular lapels, clothing which was characteristic for depictions of Turkic peoples in paintings from the fortified settlement of Afrasiab, as well on stone statues from Central Asia (illustration 10).[41]Marshak, B.I. Sogdijskoe serebro., Moscow, 1971, pp. 66-68, illus. 29; Sokrovischa Priob’ja, p. 125, no. 59.

In turn, the aforementioned ghilman guards on frescoes from the Ghazvevid palace in Lashkari Bazaar (Afghanistan) were dressed in khalaty with wide, straight-sided panels, but with only one triangular lapel. These khalaty are distantly reminiscent of Turkish outerwear seen on stone steles and several variants of free-flowing outerwear from medieval Uyghurs.[42]Kubarev, op. cit., illus. 1:23, 27, 3:9-11.; Jatsenko, op. cit., pp. 34-375, plate 67: 1. They differ from the 10th century kaftans in their wide oblique opening, the one-sided lapel, and the lack of buttons and braid. It appears that this clothing is not, in fact, directly related to the to Turkic kaftans from the second kaganate. In recent years, A.A. Ierusalimskaya has come out in favor of the Iranian or Sogdian origin of the medieval kaftans of the Central Caucasus, having seen direct analogies to Alan costume in Sogdian paintings.[43]Ierusalimskaja, A.A. “Nekotorye voprosy izuchenijja rannesrednevekovogo kostjuma (po materialam analiza odezhdy adygo-alanskikh plemen VIII-IX vv.)” Kul’tury Evrazijskikh stepej vtoroj poloviny I tys.n. (is istorii kostjuma). Samara, 2001, p. 93.

The Byzantine-Bulgarian Theory

This version of the origin of medieval Russian kaftans is evidenced by archeological finds, as well as information from written and figurative sources. For example, finds of bronze buttons analogous to those from medieval Rus’ and Birka were made in Byzantine Corinth, Bulgaria, and in Constantinople.[44]Jansson, op. cit., pp. 606-607, plate 20:2; Davidson, G.R. “The Minor Objects.” Corinth. Results of Excavations. Vol. XII. Princeton, 1952, p. 262, Nos. 2119, 2120.

One of the main pieces of evidence from written sources in this regard is found in the Book of Ceremonies of the Byzantine Court, written in the 10th century at the court of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. By analyzing data from Byzantine sources, the most important Russian Byzantinist of the 20th century, N.P. Kondakov, came to the conclusion that the Byzantine type of riding clothes, the scaramangium, was slightly different from the kaftans worn by medieval nomads. This opinion has the support of such scholars as I. Hägg, A.A. Ierusalimskaya, and to some extent, I. Jansson. N.P. Kondakov equated the Byzantine scaramangium and Eastern kaftans. However, his opinion was founded on intuition, rather than facts or pictorial sources.[45]Kondakov, N.P. Ocherki i zametki po istorii srednevekovogo iskusstva i kul’tury. Prague, 1929, p. 264. In the Book of Ceremonies of the Byzantine Court, the scaramangium is mentioned as the beloved attire of Byzantium’s military ranks. This source reports that so-called royal friends and, and in particular “friends” from “allied” Bulgaria would appear at royal feasts in scaramangii.[46]Kondakov, op. cit., p. 236. By comparing this information to depictions of noble Bulgarians in the Menologion of Basil II, it’s possible to suggest that the Bulgarians in the image are dressed in these scaramangii as mentioned in the Book of Ceremonies (illustration 11).[47]Angelov, D., Petrov, P., Primov, B. (ed.). Istorija na B’lgarija. Perva B’lgarska d’rzhava. Vol. II. Sofia, 1981, p. 143.

The Bulgarians are depicted in flowing, trimmed kaftans with fur edging on their semicircular collars and, it appears, with an inner fur lining. Judging by the color and decoration of the fabric, these Bulgarian kaftans were made of silk. The vertical opening to the waist was fastened with a series of 8-9 buttons, which were decorated with braid. The wide sleeves taper at the wrist, ending in cuffs of the same color. A unique characteristic of the kaftans depicted here is that one of them is not open below the waist. A slit is seen on the right side of the Bulgarian soldier. This detail has allowed some scholars to suggest that this item of clothing was open only to the waist. Such a cut would seem quite inconvenient for cavalry soldiers, such as the Bulgarians. Therefore, this cut is most likely a device of the artist, rather than a realistic depiction of actual clothing. Several parallels to this costume can be seen in the cut of kaftans from the Northern Caucasus, which also had fur linings, an axial opening, and braids.[48]Iarusalimskaja. A.A. Die Graber der Moscevaja Balka. Munschen, 1996, fig. 9. And yet, on the Bulgarian soldiers’ kaftans in the Menologion of Basil II, the braids are placed more frequently than was seen on kaftans from Moschevaya Balka.

The Byzantines’ acquaintance with kaftans confirms the drawings of clothing from a manuscript by the Byzantine chronicler John Skylitzes, located in the Madrid Library. For example, the manuscript twice depicts the Bulgarian Khan Omurtag, as well as one of his courtiers, in a kaftan with yellow braid (most likely, the artist was attempting to depict golden-colored braid). The “Archon of the Turks” is shown in a kaftan with a frontal opening, decorated with braid, as he negotiates with the ambassadors of “the Persian Prince” (illustrations 12, 13). In would appear that the Byzantine artist used these clothes to signify the “barbarian” leaders who led the Turkish nomads.[49]Bozhkov, A. Miniatjuri ot Madriskija r’kopis na Joan Skilitsa. Sofia, 1972, pp. 37, 59; Angelov, op. cit., pp. 149, 164; Grabar, A., Manussacas, M. L’illustration du manuscript de Skylitzes de la Bibliotheque Nationale de Madrid. Venice, 1972. And yet, in my opinion, the detailed depiction of this costume in 11th-12th century Byzantine miniatures indicates that this type of clothing was widespread among the Byzantines at this time. It is likely that it was only for this reason that illuminators were able to depict these kaftans’ details so accurately, corresponding to the fragments seen in Moschevaya Balka and the Birka burial ground. The high level of prestige associated with this clothing in 10th century Byzantium is mentioned in the Book of Ceremonies of the Byzantine Court. At a time when the ambassador from the Emir of Tarsus was received by Constantine Porphyrogenitus (chapter 15, book 2), all of the court ranks “from protospapharians down to the last man (that is, military and court officials) appeared wearing scaramangii, ordered by the color and decoration of their clothing [jeb: that is, by their rank]. In particular, those who had bulls and eagles within many circles upon their clothes, or with green and pink eagles, stood out here and there.”[50]Kondakov, op. cit., p. 301.

We should also note the absence of lapels and collars on both the kaftans from Moschevaya Balka, and on the depiction of “Bulgarian” kaftans depicted in the Madrid Skylitzes and in the Menologion of Basil II. This detail distinguishes these kaftans from their Central Asian and Turkic prototypes. Lapels are depicted on the majority of kaftan depictions from Central Asia: on the memorial stone steles of Turkic aristocrats, on the images of dehkans in murals from Penjikent and Turpan, on the khalaty worn by the ghilman from Lashkari Bazaar. Based upon these lapels, we can determine the wide wrapover of Turkic katans and khalaty. It is especially worth noting that this lack of lapels and deep wrap-overs is a characteristic detail of the Western variants of medieval European kaftans.

There are several indications that kaftans (scaramangii?) continued to be worn even at the end of the 11th century. For example, in an image from the famous Trier Psalter, Prince Yaropolk Izyaslavich is shown in a long, flowing outfit of colorful fabric. The openings, cut and cuffs of this outfit are decorated with braid.[51]Kondakov, N.P. Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i v miniatjurakh XI veka. St. Petersburg, 1906, pp. 99-101, plate VI.[52]jeb: See my translation of parts of this book on my blog: https://rezansky.com/depictions-of-the-russian-royal-family-in-11th-century-miniatures-part-i/ His cousins the Svyatoslavichi are depicted in an illumination from the Svyatoslav Izbornik in similar outfits, with braid on the chest and fur collars, which are also similar to the kaftans from the Menologion of Basil II.[53]Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, p. 41, illus. 6; Izbornik Svjatoslava 1073 g. Faksimil’noe izdanie. Moscow, 1983, p. 2. A high-ranking Byzantine official is depicted in a flowing outer garment with 15 buttons from collar to bottom hem. We learn from the inscription on an icon cover that this was the important logothete George Akropolites (1220-1282). N.P. Kondakov was of the opinion that this logothete was dressed in a kaftan or kabbadion.[54]Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, p. 83, illus. 10.

Left: Plate 6: Miniature from the Trier Psalter: Prince Yaropolk and his family before the Apostle Peter.

Center: Image 6: Depiction of a Rus’ prince from Hippolytus of Rome’s Sermon on Christ and the Antichrist. 12th century.

Right: Image 10: Depiction of George Akropolites (1220-1282) on the cover of an icon of the Blessed Mother in Lavra of St. Sergius.

The “Specific” or Local Theory.

Finally, we have the “specific” or “local” theory on the origin of kaftans. I. Hägg wrote about this possibility for clothing from the Birka burial ground. She suggested that these garments were sewn locally, in Scandinavia, from imported fabric. This theory of local production may be supported by the specific number of buttons which, it appears, was characteristic on for medieval Russian finds. Judging by finds of molds which were used for casting metallic buttons, they were able to be copied from imported examples in medieval Russian cities, and were not necessarily items of direct import.[55]Ivakin, G. “Kiev aux VIII-e-X-e siecles.” Les centers proto-urbains russes entre Scandinavie, Byzance et Orient. Realites Byzantines 7. Paris, 2000, fig. 9. The majority of finds of these buttons were from Kiev, and the vicinities of Chernigov and Gnezdovo. Undoubtedly, this clothing with its brass buttons was a copy of examples of prestigious clothing of the era. This fashion may have spread from the lands of the Caliphate through Khazaria, or from Byzantium through the lands of Bulgaria and Byzantine Crimea. In my opinion, the fashion of riding caftans undoubtedly originally spread from the nomadic tribes in regions of Central Asia. At the same time, long-term neighboring relations with Byzantium may have introduced certain changes into this fashion. It appears that, under the influence of the Byzantine Empire, the Danube Bulgarians succeeded in altering the traditional cut of this clothing. Most likely, this modified variant of the 10th century kaftan and possibly its Byzantine rendition was embraced by medieval Rus’ and subsequently also reached Birka. In my opinion, archeological finds indicate that theory of the borrowing of the kaftan from Bulgaria or Byzantium may be considered to be more persuasive. This theory is supported by the depictions of kaftans from Byzantine manuscript illuminations, as well as archeological finds. N.P. Kondakov assumed that “much attire was borrowed by the Byzantine court from barbarian leaders and, having undergone modifications, according to Byzantine ceremony, returned once again to those (barbarian) courts with their own specific meanings.”[56]Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, p. 87.

In the works of al-Istakhri, he notes that “the Rus’ was a people that cremated their dead… and that they dressed in short jackets….”[57]Novosel’tsev, A.P. “Vostochnye istochniki o vostochnykh slavjanakh i Rusi IV-IX vv.” Drevnerusskoe gosudarstvo i ego mezhdunarodnoe znachenie. Moscow, 1965, pp. 411-412. We do not know which kind of clothing this Arab source had in mind. It is possible that this clarification may be associated with the cut of Bulgarian kaftans, which reached only to the knee. Kaftans or jackets are also mentioned as the clothing of the Rus’ by Ibn Fadlan in his widely known writings about the funeral of a Rus’ noble on the Volga.

In our time, only the most rough dating of medieval Rus’ burial complexes containing bronze buttons is possible. It appears that they appeared no earlier than the mid 10th century, and existed within the limits of the second half of the 10th century. For example, the famous burial No. 42 from the Shestovitsa necropolis, based on the presence of items decorated in Mammen style, can be dated no earlier than the 960s-970s.[58]Jansson, I. “970/971 AD and the chronology of the Viking Age.” Mammen. Grav, kunst og samfund i vikingetid. Viborg Stiftsmuseums rkke 1. Hojbjerg, 1991, p. 284. A burial with mushroom-shaped buttons from Hungary is dated to the 10th century. All of the burials with analogous bronze buttons from Birka date to the late phase of the burial ground’s use, that is, from 880-970. As a result, it is possible to argue that this type of men’s wear spread in medieval Rus’ in the mid to late 10th century. Judging by the depictions of outerwear on the sons of Prince Svyatoslav Vladimirovich and in drawings from the Trier Psalter, it was used in royal circles right up through the 1070s. This chronology is supported by independent sources, such as Byzantine illuminations. Based on the dating of Byzantine miniatures from the Menologion of Basil II, the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript, and depictions of the royal family from the Svyatoslav Izbornik, is is possible to suggest that kaftans continued to exist through the late 11th century. This is evidenced not only by the illustrations themselves, but also by the precision with which the artists conveyed the particular qualities of cut and even fabric patterns.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Rabinovich, M.G. “Drevnerusskaja odezhda IX-XIII vv.” Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy. Moscow, 1986, pp. 40-41; Saburova, M.A. “Drevnerusskij kostjum. Odezhda.” Drevnjaja Rus’. Byt i kul’tura. Moscow, 1997, p. 97. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Rabinovich, op. cit., pp. 40-41; Sedov, V.V. “Odezhda vostochnykh slavjan VI-IX vv.” Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy. Moscow, 1986, pp. 30-39. |

| ↟3 | Lebedev, G.S. “Sotsial’naja topografija mogil’nika epokhi vikingov v Birke.” Skandinavskij sbornik. Iss. XXII. Tallin, 1977, pp. 151-156; Zharnov, Ju.E. “Zhenskie skandinavskie pogrebenija v Gnezdove.” Smolensk i Gnezdovo. Moscow, 1991, pp. 217-220; Graslund, A.S. “The Burial Customs. A study of the graves on Bjorko.” Birka IV. Stockholm, 1980, pp. 79-82. Burial chambers were discovered in many Scandinavian and medieval Russian burial mounds from the Viking era. The majority of scholars are of the opinion that these burials are of northern European aristocrats. |

| ↟4 | Avdusin, D.A., Pushkina, T.A. “Tri pogrebal’nye kamery iz Gnezdova.” Istorija i kul’tura dreverusskogo goroda. Moscow, 1989, pp. 198, 201, illus. 3; Fekhner, M.V. “Tkani iz Gnezdova.” Arkheologicheskij sbornik pamjati M.V. Fekhner. Trudy GIM. No. 111. Moscow, 1999, p. 8. |

| ↟5 | Kamenetskaja, E.V. “Zaol’shanskaja kurgannaja gruppa Gnezdova.” Smolensk i Gnezdovo. Moscow, 1994, pp. 151, 171-172, illus. 7, 3-5; Fekhner, op. cit., p. 8. |

| ↟6 | Hägg, I. “Die Tracht.” Birka II:2. Systematische Analysen der Graberfunde. Stockholm, 1986, pp. 68-69; Jansson, I. “Wikingerzeitlicher orientalicher Import in Skandinavien.” Bericht der Romisch-Germanischen Kommission. Bd. 69. Mainz am Rhein, 1988, p. 594. |

| ↟7 | Graslund, op. cit., p. 13. |

| ↟8 | Arbman, H. Birka I. Stockholm, 1940-1943, p. 273, 411, Illus. 221, 365. In grave No. 716, perfectly in the grave, the distance from the first to last button measured around 20 cm (below was there was a belt, decorated with plaques, and remains of a pouch). In chamber No. 752, the buttons lay in a row around 38-40 long from the fibula (at the deceased’s throat) to the belt buckle. In no. 944, the buttons lay in a row from the remains of the skull for a distance of 28-30 cm. In no. 985, the buttons ran to a belt decorated with plaques, for a length of 30-34 cm. Aside from these burials where the buttons were found in situ, analogous bronze buttons (8 in number) were found in the burnt remains of grave no. 56. In chamber no. 985, four massive bronze buttons lay lay along the male’s spine, for a distance of 10-15 cm. In grave no. 949 of the Birka burial ground, three such buttons served to fasten a pouch with bronze fittings (the closest analogies to this type of pouch are from a burial mound in Volga Bulgaria and the Timerevo burial mound) (cf. Arbman 1940 op. cit., Table 128, 2). In grave No. 1105 of a woman, one bronze button with a tab lay alongside glass beads near the lower jaw of the deceased (from a shirt or collar). Aside from Birka, bronze mushroom-shaped buttons were discovered in Uppland, on the islands of the Aland archipelago, and in Southern Finland. However, these discoveries were most likely not associated with finds of “Eastern-style kaftans” (cf. Jansson, op. cit., p. 606). |

| ↟9 | Jansson, op. cit., pp. 594, 606. |

| ↟10 | “Saga ob Egile.” Islandskie sagi. Moscow, 1956, p. 205. It is worth considering that the most widespread type of men’s wear in Northern Europe and Anglia during this time was the undertunic and cloak. |

| ↟11 | Shovkopljas, G.M. “Arkheologichni pam’mjatki gori Kiselivki v Kievi.” Pratsi kiivsk’kogo derzhavnogo istorichnogo museju. Iss. 1. 1958, pp. 147-148, plate 5, 9, 12; plate 6, 7. |

| ↟12 | Archaologisches Museum, Istanbul, No. 6867 (cited in Jansson, op. cit., p. 607). |

| ↟13 | These were used to fasten the collar of a shirt, but most often sets of such buttons were associated with men’s outerwear. In a series of medieval Russian burials, traces of such garments were recorded, which differ in their features from the majority of those buried in early medieval Russian gravesites. This costume can be traced especially clearly in complexes with cadavers, where remains of fabric and bronze buttons are recorded directly on the bones of the deceased. A distinctive feature of this garment are the bronze mushroom-shaped buttons located along the spine of the deceased from the chest to the pelvis. A majority of similar finds were made in male graves or in graves containing men’s items. In the literature, this type of garment is called “a kaftan” and its origin is deduced to be from Central Asia or Iran. Various styles of kaftan were in use among the Asiatic nomadic tribes (cf. Samashev, Z.S. “Odezhda i pricheski credevekovykh nomadov.” Kul’tury Evrazijskikh stepej vtoroj poloviny I tys. n.e. (Voprosy khronologii). Samara, 1998, pp. 406-408). Finds of entire early medieval kaftans fastened with buttons were associated with the well-known northern Caucasus burial at Moschevaja Balka (cf. Ierusalimskaja, A.A. Kavkaz na shelkovom puti. Katalog vremennoj vystavki. St. Petersburg, 1992). Depictions of similar outfits can be seen in Sogdian murals, Turkic stone steles, and in the Menologion of Basil II in the scene of the abuse of Byzantine prisoners of war by the Bulgarians. Aside from the bronze, mushroom-shaped buttons, kaftans were also fastened using bone buttons. A set of similarly-decorated, hemispherical bone buttons were found in the Gul’bische burial mound in Chernigov. Meanwhile, it seems that some bronze mushroom-shaped buttons were not associated with kaftans. This is especially true for burial complexes where fewer than 3 buttons were discovered. The closest example is seen in data from medieval Russian burials from the 11th-13th centuries, where 1-3 buttons were recorded in use to fasten standing collars on men’s and women’s shirts (Saburova, M.A., Elkina, A.K. “Detali drevnerusskoj odezhdy po materialam nekropolja g. Suzdalja.” Materialy po srednevekovoj arkheologii Severo-Vostochnoj Rusi.” Moscow, 1991, pp. 54-62; Saburova, M.A. Drevnerusskij kostjum. Odezhda.” Drevnjaja Rus’. Byt i kul’tura. Arkheologija. Moscow, p. 100.) |

| ↟14 | Borovs’kij, Ja.E., Kapljuk, O.P. “Doslidzhennja kiivs’kogo Ditintsja.” Starodavnij Kiiv. Arkheologichni doslidzhennja 1984-1989 gg. Kiev, 1993, pp. 3-8; Somosvasov, D.Ja. Mogil’nye drevnosti Severjanskoj Chernigovschiny. Posmertnoe izdanie. Moscow, 1917, pp. 77-80; Rybakov, B.A. “Drevnosti Chernigova.” MIA, 1949 (11), p. 22; Blifel’d, D.I. Davn’orus’ki pamjatki Shestovitsi. Kiev, 1977, pp. 128-131, 138-141, 151-155; Stankevich, Ja.V. “Shetovitskoe poselenie i mogil’nik po materialam raskopok 1946 g.” KSIIIMK. 1962 (37), pp. 23-27; Zharnov, Ju.E. op. cit., pp. 208, 210-211; Avdusin, Pushkin, op. cit., pp. 196-200; Kamenetskaja, op. cit., pp. 165, 171-172. It is particularly worth noting that the sets of buttons from kaftans, to date, have not once been found in “common” burials in 10th century pits or coffins, which exist in large numbers in the burial grounds from Gnezdovo, Shestovitsa and in the medieval Russian necropolises in Kiev. Likewise, signs of kaftans have not been found in such rich burial grounds in the upper Volga such as Timerevo or Mikhajlovskoe. Signs of kaftans likewise were found found in the burial grounds of Gotland, where large quantities of medieval Russian items have been found. Bug, if the lack of kaftan finds in Northern Rus’ can be associated with the peculiarities of northern dress, their absence on the island of Gotland can most likely be associated to chronological factors. The main import of medieval Russian goods to Gotland began only in the 11th century. |

| ↟15 | Karger. M.K. Drevnij Kiev. Vol. I. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958, p 187, illus. 34. In this case, the number of buttons corresponds to the number on the kaftans from Moschevaja Balka. It is possible to suppose that the garment in this chamber differed from the “traditional” medieval Russian kaftans of the 10th century. |

| ↟16 | Borovskij, Ja.E., Kaljuk, A.P., Syromjatnikov, A.K., Arkhipov, E.I. Arkheologicheskie issledovanija v ‘Verkhnem Kieve’ v 1988 godu.” NA IA NANU. no. 1988(17), pp. 5-12; Borovs’kij et.al., op.cit., pp. 3-8. |

| ↟17 | Blifel’d, op. cit., p. 43. |

| ↟18 | Blifel’d, op. cit., pp. 188-189. |

| ↟19 | Stankevich, op. cit.; Androschuk, F.O. Normani i slov’jani u Podesenni (Modeli kul’turnoj vzaemodii dobi rann’ogo seredn’ovichchja). Kiev, 1962, p. 65, illus. 43, 47. |

| ↟20 | Zharnov, op. cit., p. 211. |

| ↟21 | Shirinskij, S.S. “Ukazatel’ materialov kurganov, issledovannykh V.I. Sizovym u d. Gnezdovo v 1881-1901 ff.” Trudy GIM Pamjatniki kul’tury. 1999 (36), pp. 103, 117, 120-121, 127; Blifel’d, D.I. “Drevn’orus’kij mogil’nik v Chernigovi.” Arkheologija. 1965 (XVIII), pp. 105-138, 123, plate IV, 12-15. |

| ↟22 | Blifel’d, op. cit., p. 117. |

| ↟23 | Blifel’d, op. cit., p. 131. |

| ↟24 | In my opinion, a burial from a large burial mound in Gul’bische in Chernigov can be considered as an exception from this list of complexes. This is the only 10th century complex where numerous buttons were made from bone, rather than bronze. The clothing set in this grave revealed 9 hemispherical ornamental buttons, which most likely belonged to a kaftan. This theory is supported by the number of buttons, as well as their central Asiatic or Iranian origin (cf. Put’ iz varjag v greki. Katalog. Moscow, 1996, p. 80, no. 696.). Numerous finds of similarly decorated buttons have also been seen from the medieval cities of Central Asia and Azerbaijan. The largest number of finds of these hemispherical bone buttons with circular designs come from the 10th century layers from the village of Khorezm (cf. Vishnevskaja, N.Ju. Remeslennye izdelija Dzhigerbenta (IV do n.e. – XIII v.n.e.). Moscow, 2001, pp. 105-108, illus. 42, 1-15, 45, 11-14; Akhmedov, G.M. “Azerbajdzhan v IX-XIII vv.” Krym, Severo-Vostochnoe Prichernmor’e i Zakavkaz’e v epokhu srednevekov’ja IV-XIII veka. Arkheologija. Moscow, 2003, p. 381, plate 192, 8-20). |

| ↟25 | In addition, these buttons were found in medieval layers of the Byzantine city of Corinth. |

| ↟26 | Ierusalimskaja, op. cit., pp. 14-15, illus. 1-2, photo 9. |

| ↟27 | Krachkovskij, I,Ju. Puteshestvie Ibn-Fadlana na Volgu. Moscow-Leningrad, 1939, pp. 80-81. However, it remains unclear what type of clothing Ibn-Fadlan had in mind. It should be noted that in medieval Persian sources, the word “kaftan” often denoted a type of armor covered in fabric. |

| ↟28 | Kubarev, G.B. “Khalat drevnikh tjurok Tsentral’noj Azii po izobrazitel’nym materialam.” Arkheologija, etnografija i antropologija Evrazii. No. 3 (3). Novosibirsk, 2000, pp. 81-85. |

| ↟29 | Kubarev, op. cit., p. 85, illus. 1, 8, 23, 25, 27, illus. 3, 9, 10, 11, 18. |

| ↟30 | Kubarev, op. cit., illus. 1, 2, 17, 19, illus. 2, 3, 4, 34, illus. 3, 2, 16, 17, 28. |

| ↟31 | Kubarev, op. cit., illus. 1, 2, illus. 2, 4, illus. 3, 2. |

| ↟32 | Jatsenko, S.A. “Kostjum.” Vostochnyj Turkestan v drevnosti i rannem crednevekov’e. Arkhitektura. Iskusstvo. Kostjum. Moscow, 2000, pp. 332-333, plate 35, 1-3, 5, plate 60, 1-2. |

| ↟33 | Jatsenko, op. cit., p. 370, illus. 67, 1-3, illus. 69, 1-3; Kljashtornyj, S.G. Istorija Tsentral’noj Azii i pamjatniki runicheskogo pis’ma. St. Petersburg, 2003, p. 374. |

| ↟34 | Sokrovischa Priob’ja. Katalog vystavki. St. Petersburg, 1996, pp. 114-117, 120-121, No. 53, 55. |

| ↟35 | Sokrovischa Priob’ja, op. cit., p. 116. |

| ↟36 | Sokrovischa Priob’ja, op. cit., p. 121. |

| ↟37 | Gorelik, M.V. “Obraz muzha-voina v Kabarii-Ugrii-Rusi.” Kul’tury Evrazijskikh stepej vtoroj poloviny I tys.n.e. (is istorii kostjuma). Samara, 2001, p. 176. |

| ↟38 | Jansson, op. cit., p. 606. |

| ↟39 | Tocik, B. “Altmagyarische graberfelder in der sudwestslowakei.” Archaeologica Slovaca. Vol. III. Bratislava, 1968, p. 43, Plate XXXIV:9. |

| ↟40 | Jansson, op. cit., p. 602, plate 18. |

| ↟41 | Marshak, B.I. Sogdijskoe serebro., Moscow, 1971, pp. 66-68, illus. 29; Sokrovischa Priob’ja, p. 125, no. 59. |

| ↟42 | Kubarev, op. cit., illus. 1:23, 27, 3:9-11.; Jatsenko, op. cit., pp. 34-375, plate 67: 1. |

| ↟43 | Ierusalimskaja, A.A. “Nekotorye voprosy izuchenijja rannesrednevekovogo kostjuma (po materialam analiza odezhdy adygo-alanskikh plemen VIII-IX vv.)” Kul’tury Evrazijskikh stepej vtoroj poloviny I tys.n. (is istorii kostjuma). Samara, 2001, p. 93. |

| ↟44 | Jansson, op. cit., pp. 606-607, plate 20:2; Davidson, G.R. “The Minor Objects.” Corinth. Results of Excavations. Vol. XII. Princeton, 1952, p. 262, Nos. 2119, 2120. |

| ↟45 | Kondakov, N.P. Ocherki i zametki po istorii srednevekovogo iskusstva i kul’tury. Prague, 1929, p. 264. |

| ↟46 | Kondakov, op. cit., p. 236. |

| ↟47 | Angelov, D., Petrov, P., Primov, B. (ed.). Istorija na B’lgarija. Perva B’lgarska d’rzhava. Vol. II. Sofia, 1981, p. 143. |

| ↟48 | Iarusalimskaja. A.A. Die Graber der Moscevaja Balka. Munschen, 1996, fig. 9. |

| ↟49 | Bozhkov, A. Miniatjuri ot Madriskija r’kopis na Joan Skilitsa. Sofia, 1972, pp. 37, 59; Angelov, op. cit., pp. 149, 164; Grabar, A., Manussacas, M. L’illustration du manuscript de Skylitzes de la Bibliotheque Nationale de Madrid. Venice, 1972. |

| ↟50 | Kondakov, op. cit., p. 301. |

| ↟51 | Kondakov, N.P. Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i v miniatjurakh XI veka. St. Petersburg, 1906, pp. 99-101, plate VI. |

| ↟52 | jeb: See my translation of parts of this book on my blog: https://rezansky.com/depictions-of-the-russian-royal-family-in-11th-century-miniatures-part-i/ |

| ↟53 | Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, p. 41, illus. 6; Izbornik Svjatoslava 1073 g. Faksimil’noe izdanie. Moscow, 1983, p. 2. |

| ↟54 | Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, p. 83, illus. 10. |

| ↟55 | Ivakin, G. “Kiev aux VIII-e-X-e siecles.” Les centers proto-urbains russes entre Scandinavie, Byzance et Orient. Realites Byzantines 7. Paris, 2000, fig. 9. |

| ↟56 | Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, p. 87. |

| ↟57 | Novosel’tsev, A.P. “Vostochnye istochniki o vostochnykh slavjanakh i Rusi IV-IX vv.” Drevnerusskoe gosudarstvo i ego mezhdunarodnoe znachenie. Moscow, 1965, pp. 411-412. |

| ↟58 | Jansson, I. “970/971 AD and the chronology of the Viking Age.” Mammen. Grav, kunst og samfund i vikingetid. Viborg Stiftsmuseums rkke 1. Hojbjerg, 1991, p. 284. |