My research on Russian quivers for the project I’m working on led me to the article below, about leatherworking in medieval Novgorod and evidence that has been found in archeological digs there. This is a great overview of medieval leatherworking, including tanning, dyeing, joining, carving and stamping, based on the multitude of leather finds from that city. Aside from some of the chemical processes used in tanning, leatherworking in medieval Rus’ appears to have used many of the same processes as we use today. The article specifically addresses shoemaking, but also a number of other leather items found in the archeological layers, most likely created by the same artisans in early period, before becoming specialized crafts in later period.

Toward a History of Leatherworking and Shoemaking in Novgorod the Great

A translation of Изюмова, С.А. «К истории кожвенного и сапожного ремесел Новгорода Великого.» Материалы и исследования по археологии СССР. 1959 (65), с. 192-222. / Izjumova, S.A. “K istorii kozhevennogo i sapozhnogo remesel Novgoroda Velikogo.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR. 1959 (65), pp. 192-222.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

http://www.archaeology.ru/Download/MIA/MIA_065.pdf. ]

The question of studying the leatherworking and shoemaking arts of medieval Novgorod and its products is of great historical and cultural interest. But, this question has not yet received its due attention in the literature. In published works, one finds only the most general characteristics of the arts associated with processing leather and creating various items from it.[1]Jakunina, L.I. “Novgorodskaja obuv’ XII-XIV vv.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury (KSIIMK). 1947 (17), pp. 38-48.This situation, to a certain extent, is explained by the extreme limitedness of the available archeological material which serves as the main source for this craft.

Over the last few years, as the result of an ongoing, systematic archaeological study of the Novgorod territory, a large number of various kinds of leather goods have been uncovered, corresponding to various periods of the city’s existence, as well as tools for leatherworking and shoemaking (adzes, knives, awls, pads, lasts, etc.) and remnants of production facilities (liming pits [Rus. зольники / zol’niki], leather washes, cobbler workshops). This new archaeological material allows us to elaborate on the technologies used in shoemaking in medieval Novgorod, and to give a chronological classification of Novgorodian shoes in the 10th-16th centuries. However, this material, along with the fragmentary nature of written sources and the known incompleteness of data from chemical analysis of medieval Russian leather items,[2]“Izuchenie drevnego proizvodstva kozhi i izdelij iz kozhi,” pp 61, 73. Manuscript in the archive of the Institute of History of Material Culture of the Soviet Academy of Sciences (IIMK), f. I, No. 555. is insufficient to fully illuminate the technologies of the leather arts. As a result, the primary process for tanning animal skins has to be restored using indirect means, including ethnographic material and literature on the technologies of leatherworking from the late 19th century. As for the social side of the studied craft, due to the specificity of the archaeological material and the lack of information from written sources, it cannot be as detailed as the technical study. This work, based primarily on material from a single dig site, cannot pretend to be exhaustive. We must hope that further accumulation of archaeological data in Novgorod and other medieval Russian cities will allow us to highlight in further detail the production discussed below.

I. Leather Production

The appearance and blossoming in Novgorod and its surroundings of leatherworking, associated with the tanning of animal hides and preparing an assortment of items from them, were driven by societal needs, and the development of cattle breeding served as the necessary source of raw material. The widespread presence of animal husbandry in Novgorod can be seen from the remnants of cattle stalls encountered during excavations in various locations throughout the city, as well as the presence of bones from domesticated animals. In written sources, we find mention of herds of horses and of large horned cattle belonging to Novgorod feudal lords, monasteries, and boyars.[3]Novgorodskie pistsovye knigi (NPK), vol. II, p. 28, et.al.

The rise of cattle breeding in Novgorod and its holdings allowed the rise of selected industries of artistic production tied to the processing of its raw materials and their use for various kinds of items (leatherworkers, shoemakers, sheepskin tanners, furriers, bone-carving, and other manufacturing). The current work will highlight the artistry related to items made from leather.The rise of cattle breeding in Novgorod and its holdings allowed the rise of selected industries of artistic production tied to the processing of its raw materials and their use for various kinds of items (leatherworkers, shoemakers, sheepskin tanners, furriers, bone-carving, and other manufacturing). The current work will highlight the artistry related to items made from leather.

Novgorod leatherworkers made use of hides from horses, as well as large- and small-horned cattle. The processing of hides started with a soak to clean off any dirt. During an excavation of Yaroslav’s Court in 1946, they found in the 12th layer remnants of a shoemaker’s workshop and a beamhouse [Rus. мочило, mochilo, lit. “drenchery” or “rettery”]. But, frequently, hides were washed directly in a river. After, the skins were cleared of any subcutaneous tissue, flesh, and any remnants of meat or fat. During an excavation of the Nerevskij End neighborhood of Novgorod, iron adzes[4]Kolchin, B.A. “Chernaja metallurgia i metalloobrabotka v drevnej Rusi.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR (MIA). 1953 (32), p. 129, illus. 100. used for removing flesh from leather were found. As opposed to a draw-knife, the adze had a single straight-edge handle.

After washing and scraping off the flesh, the skins would undergo liming [Rus. золка / zolka], that is, they were processed with lime or lime mixed with ash, in order to remove the hair. This process for removing hair from hides was known by Novgorod tanners no later than the 9th century.

During archeological excavations in the Nerevskij End in 1953-1954, layers from the 9th-15th centuries were found to contain remnants of leatherworker and shoemaker workshops. Around these workshops, they found layers of wool mixed with ash and lime, 5-7 cm to 10-15 cm deep.[5]Otchet Novgorodskoj arkheologicheskoj ekspeditsii IIMK za 1953 g. vol. 2, pp. 35, 38 (Manuscript in the IIMK archive); Otchet Novgorodskoj arkheologicheskoj ekspeditsii IIMK za 1954 g. vol. 1, pp. 2, 48 (Manuscript in IIMK archive).

Liming of hides was conducted in special rectangular wooden boxes. One such box dating to the 12th century was found by A.V. Artsikhovskij on Slavenskij Hill.[6]A.V. Artsikhovskij. “Raskopki na Slavne v Novgorode.” MIA. 1949 (11), pp. 126-128.

After liming, the hair was scraped off the hides, then the hides were washed in water and then “soured” [Rus. квасить, kvasit’] in order to better soften the hide. According to written sources, this softening was done using sour bread solutions. In this way, according to a 12th-century description of the legendary travels of the Apostle Andrew, “And after a while we saw Slavenskij Hill and we went to the village. And we saw wooden baths, which were strongly heated and mixed, then they scraped [the hides] with knives, and covered them in leather kvas….”[7]Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej. Vol. 1, “Lavrent’evskaja letopis’.” p. 8. In medieval Russian written sources, the words usmie, usma, usnie meant leather.[8]Lavrent’evskaja letopis’. p. 123. And “kvas usnijan” is nothing other than kvas used to soften leather. This softening with kvas was used to create the best types of leather – juft’ and poluval.[9]Povarnin, G. Ocherki melkogo kozhevennogo proizvodstva v Rossii. Part 1: Istorija i tekhnika proizvodstva. St. Petersburg, 1912, pp. 64, 147.

The leather, stripped of hair and rinsed in kvas, was then tanned. Chemical analysis has determined that medieval tanners used tanning solutions made from various tanning substances obtained from the bark of various trees (oak, willow, alder, and others).[10]“Izuchenie drevnego proizvodstva kozhi…”, p. 67. The most common tanning agent was the tannins in the bark of willow and oak trees (up to 12-16%).[11]Povarnin, G. Dubil’noe kor’e i ego sbor. Moscow, 1923, pp. 5, 7, 10. This ancient technology of tanning leather using vegetable tannins, by sprinkling bark over the leather, was still in use in Tikvin Posad in the 16th-17th centuries,[12]Serbina, K.N. Ocherki iz sotsial’no-ekonomicheskoj istorii russkogo goroda. Tikhvinskij posad XVI-XVII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1951, p. 163. and was preserved in artisanal handiwork until the 19th century.

Novgorodian leather was substantially well preserved: despite how long items were buried in the earth, items have retained their softness, flexibility, and strength. B.A. Rybakov, looking at the question of leather tanning, believed that in medieval Rus’ “they had special extracts, such as “leather kvas,” used for tanning hides.”[13]Rybakov, B.A. Remeslo drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1948, p. 402. This same opinion was also held by M.G. Rabinovich.[14]Rabinovich, M.G. “Arkheologicheskie raskopki v Moskve v Kitaj-gorode.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury (KSIIMK). 1951 (38), p. 54. Meanwhile, according to ethnographic data,[15]Belitser, V.N. “Narodnaja odezhda udmurtov.” Trudy Instituta etnografii, novaja serija. Vol. 10, 1951, p. 29. kvas was used to remove hair from hides, and according to materials on artisanal handicrafts,[16]Povarnin, Ocherki…, pp. 146-147, 204-205. to soften leather. Kvas and kissel contain no tannins, making them completely unsuitable for such an important operation as tanning.

Taking a close look at leather items from medieval Novgorod, it is striking what a range of materials were used to create them. For example, the soles [Rus. подошва, podoshva] of shoes were distinguished for their great firmness, density and tensile strength, while the shoe uppers [Rus. верх, verkh and головка, golovka] were noted for their thinness and softness. It follows that Novgorod tanners, while preparing their raw materials, took into account its intended use. This use of various techniques to tan leather in Novgorod led to sole-makers being distinguished from general tanners by the 15th-16th centuries.[17]Grekov, B.D. Opis’ torgovoj storony v pistsovoj knige po Novgorodu Velikomu XVI v. St. Petersburg, 1912, pp. 41, 63.

Leather from finished items from Novgorod had a singular thickness, from which we can conclude that after tanning, leather was evened out [jeb: pressed or shaved?]. Afterwards, it was oiled [Rus. жировали, zhirovali, “fattened”] to make it elastic and waterproof, and rolled. This rolling of the leather, especially when creating juft’[18]jeb: “Russian leather,” a kind of leather noted for its pliability., was done using a special tool called a leather press [Rus. кожемялка, kozhemjalka, literally “leather softener”]. One of these was found during an excavation of an earthen settlement in Staraja Ladoga, in a layer from the 11th century,[19]Orlov, S.N. Derevjannye izdelija Staroj Ladogi VII-X vv. Kandidatskaja dissertatsija. 1954, plate XVII, items 7, 19, pp. 172-175.[20]jeb: See image JEB1 in the Addenda section below, an example of a kozhemjalka used by Siberian tribes to soften leather. The bundle of leather is pressed between two roughened wood surfaces using a long handle. along with a large number of leather items, attesting to the very early development of tanning in Novgorod.

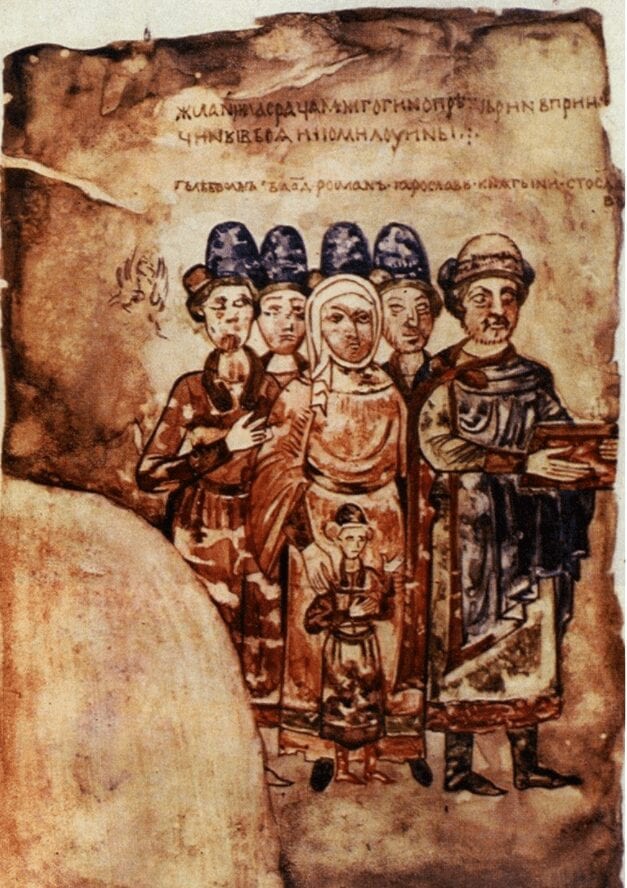

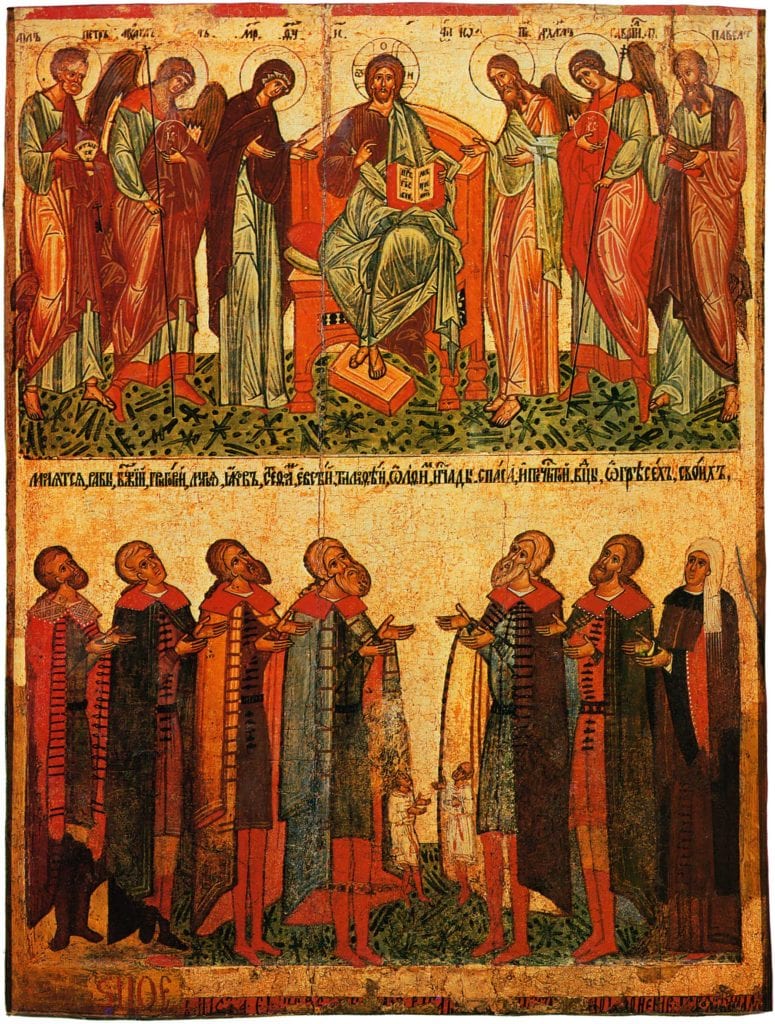

The external appearance of finished leather items has a black, dark-brown, or sometimes green color, allowing us to discuss the dyeing [Rus. окрашивание / okrashivanie, “coloring”] of leather by Novgorod tanners. This observation is confirmed by visual sources: a fresco in the Savior Church on the Nereditsa (12th cent.) depicts Prince Jaroslav Vladimirovich in green shoes;[21]Prokhorov, V.V. Materialy po istorii russkikh odezhd i obstanovki zhizni narodnoj. St. Petersburg, 1881, p. 77 and illustration. in the icon “The Praying Novgorodians” (15th century), the boyars’ children are wearing red shoes,[22] Novgorod museum, exposition, hall 2.[23]jeb: See image JEB2 in the Addenda section below of this icon, with the Novgorodians in the lower row wearing brown, dark brown, and red boots. and so forth.

The ability to dye leather to different colors (green, yellow, red, et.al.) was known in Rus’ in the earliest times. Miniatures in the Sviatoslavov Izbornik (1073) show various images with colored medieval Russian footwear.[24]Kondakov, N.P. Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i v miniatjurakh XI v. St. Petersburg, 1906, p. 40. Judging by this pictorial evidence, colored footwear was worn only by the upper levels of feudal society – princes, boyars, and their relatives. Chemical analysis of medieval leather items established that this dyeing was done using iron salts.[25]“Izuchenie drevnego prioizvodstva kozhi…”, p. 61.

In addition to tanned leather, Novgorod tanners also created rawhide [Rus. сыромятная, syromjatnaja]. This was known for its strength, but would soak through faster in water. Rawhide was not tanned, but rather was just kneaded and then soaked in fat. Leatherworkers used rawhide to make belts, tackle, and a simple form of footwear called “bog shoes” [Rus. поршни, porshni].

The custom of making porshni from rawhide survived in Russia right up to the 17th century. In the Perm’ Chronicle compiled by Shishonko, the following edict from the archbishop of Vologodsk and Perm’ is given: “Let them (the priests) not wear raw (rawhide) porshni… They who walk about in such shoes in the sanctuary bring a bloodless sacrifice, and for this, God will be angry, and will bring about fires and disasters.”[26]Permskaja letopis.’ Vtoroj period. Perm’, 1881, p. 443.

During excavations of a 9th-10th century layer in Staraja Ladoga, special wooden devices for cutting rawhide belts were found. These were in the form of a bar with two elongated slots.[27]Orlov, op. cit., pp. 48-49, plate 11, item 2; plate IV, item 5; plate V, item 1. Similar tools are also seen in the ethnographic record.[28]Ethnographical Museum of the Peoples of the USSR (Leningrad); “Evenki” section.

This leaves, then, the unclear question of the manufacture of saffian[29]jeb: Leather made of goatskin or sheepskin, usually dyed in bright colors, aka “Morocco leather.” in 9th-16th century Novgorod. A green saffian boot with a tall pointed heel and a pointed raised toe found in Lake Il’men[30]Novgorod Museum, hall 3. is perfectly identical to one housed in the State Armory in Moscow (17th century),[31]Armory museum, Moscow, Collection of clothing from [Tsar] Aleksej Mikhajlovich. but whether it was brought there from Moscow, where saffian was produced in the 17th century,[32]Novitskij, G.A. Pervye moskovskie manufaktury XVII v. po obrabotke kozhi. Report read at the section meeting of the Society for Study of the Moscow Province, March, 1926. rather than made in the Il’men region, is difficult to say. Novgorodian icons depict colored boots, and it’s entirely possible that they would have been made of saffian.[33]Novgorod museum, hall 2. However, the data available to us are quite insufficient in order to confirm that there manufacturing of saffian occured in Novgorod.

The methods described above for processing animal hides by Novgorod tanners (washing, liming, kvassing, tanning, and finishing) attest to the high level of development of the leather tanning arts in the period under review. These particular technological methods for processing animal hides, mastered by Novgorodians in the 9th-14th centuries, were preserved in the artisanal production in Russia almost without change right up to the 19th century.

The massive accumulation of items related to leatherworking found by excavations, including lumps of fur mixed with lime, scraps of leather, and leather shoes numbering in the several thousands, speaks to the specialization of leatherworking and shoemaking into a special branch of the arts; the volume of leather and items created from it went well beyond personal consumption by its creators.

The coexistence of remains of the tanning and shoemaking arts, concentrated in several relatively small structures,[34]A 12th-century workshop on Slavenskij Hill was 5.6 x 5.3 m. would indicate that in Novgorod, there was no differentiation between these two arts. Leather tanners were simultaneously also shoemakers. This lack of differentiation during early development of these arts was seen not only in Novgorod, but also in Southern Russia. No wonder that a chronicler, while recollecting the legendary Russian bogatyr who defeated Pechenezhin in hand-to-hand combat, calls him both Jan Kozhemjakij (the Leather-Maker) and Jan Usmoshevets (the Shoe-Maker).[35]Rybakov, op. cit., p. 402.

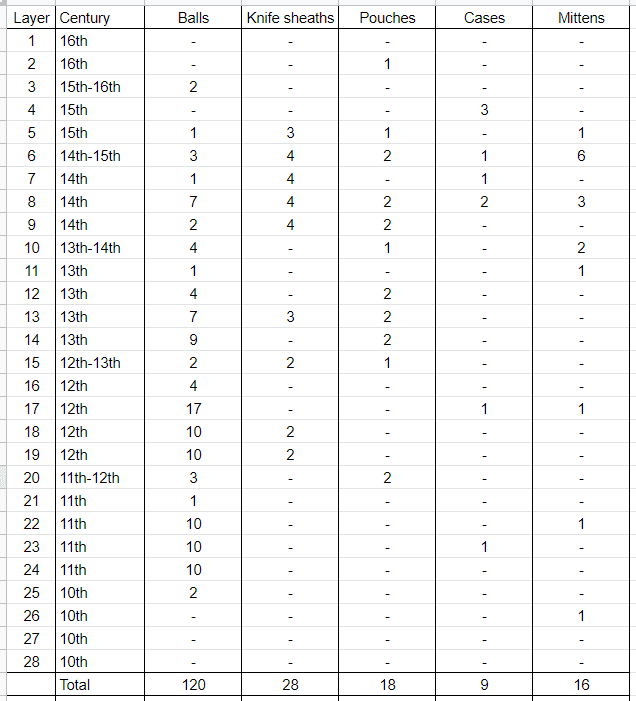

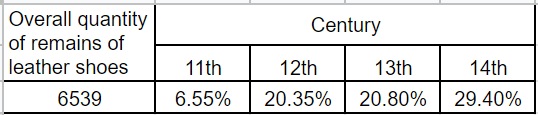

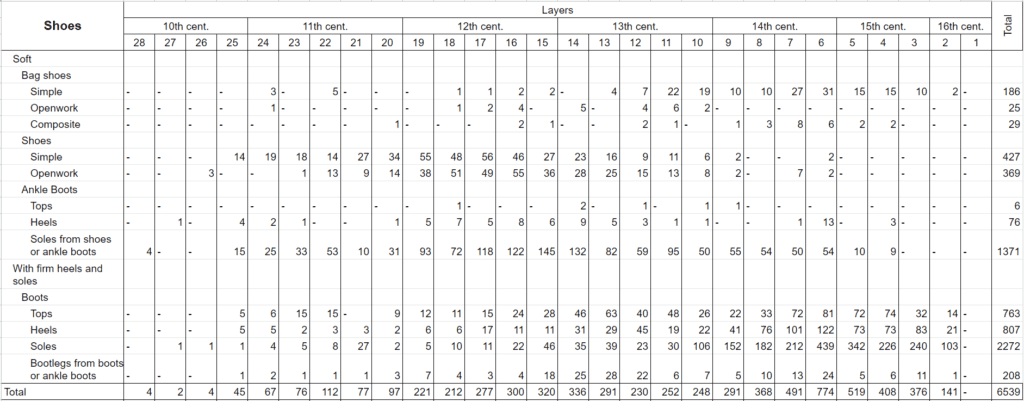

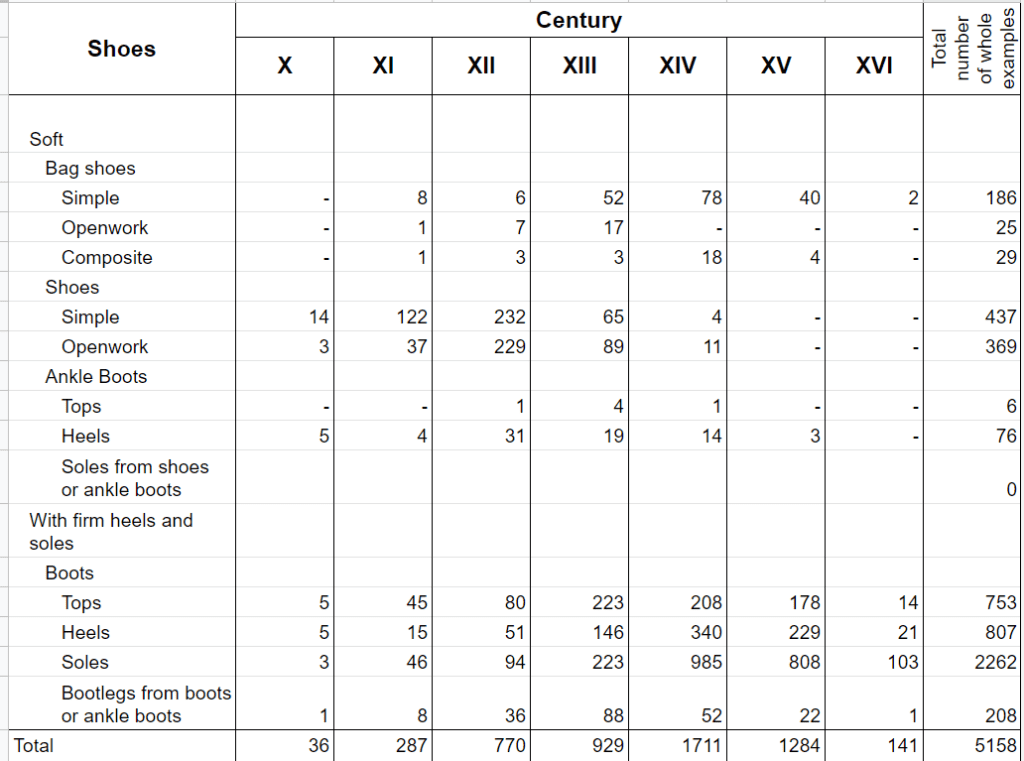

The subsequent economic and cultural development of Novgorod made possible an increase in demand for leather goods, requiring tanners to create a larger quantity of raw materials. The cited statistical data on leather shoes found in excavations of Nerevskij End, demonstrate at a glance a sharp increase in the quantity of finished shoes in the 12th-13th centuries, as opposed to the 9th century (Table 1.)

The First Novgorod Chronicle states that the number of artisans who perished in the Battle of the Neva in 1240 included “Innumerable sons of leatherworkers.”[36]Pervaja Novgorodskaja letopis’ (NL1), p. 294. Here, leatherworkers are noted as a distinct group of artisans, separate from shoemakers. A comparison of the aforementioned list in the First Novgorod Chronicle against the archeological data allows us to say that there was a complete distinction of leatherworkers vs. shoemakers by the 12th-13th century.

The leatherworking arts developed not only within Novgorod, but also in its surrounding villages. In written sources about the Votskaja and Shelonskaja pjatinas[37]jeb: A medieval administrative system for the lands around Novgorod. The land was divided into five districts [Rus. пятины, pjatiny, “fifths”]., the list of village artisans mentions both tanners and shoemakers.[38]Gnevushev, A.M. Ocherki ekonomiheskoj i sotsial’noj zhizni sel’skogo naselenija Novgorodskoj oblasti posle prisoedinenija Novgoroda k Moskve. Vol. 1, part 1. Kiev, 1915, pp. 249-253. However, village artisans were tied to arable land,[39]NPK, vol. 1, pp. 457, 580, 618, 640. and for them, the arts were ancillary to farming.

In the first half of the 15th century, leather production in Novgorod was imposed with a [Moscow] state tax, the “black extortion”[40]jeb: This was an extraordinary tax imposed by Moscow to help pay tribute to the Mongol Horde. In 1371, Dmitrij of Moscow and Mamaj negotiated the tribute to 1 ruble for every 2 plows (or equivalent units from other professions). Moscow became responsible for collecting the tribute from the other regions of Russia and paying the tribute to the Horde directly. [Rus. черный бор, cherny bor]. In a letter from 1437, a tanning vat [Rus. “тщан кожевничий”, tschan kozhevnichij] is listed as one taxation unit: “one grivna for each new plow, one for a mortar… and one for each tanning vat, and one for each shop.” The taxation of leatherworking by the government points to the great meaning it had in the economy of the Novgorod region.

This information which we have shown, unfortunately, does not give us any idea of the character of the trade in finished leather goods. But, this question has great significance in determining the categories of artisans. Based on the data at our disposal about the shoemaking arts, we may suppose that Novgorod leatherworkers worked on spec from consumer orders, receiving from them the necessary materials, as well as for sale on the market, buying raw materials with the proceeds. The character of finished products, in particular shoes made from ordinary types of leather, shows that leatherworkers were able to meet the needs of the lower urban classes of society and belonged to a free community of artisans. At the same time, there was another category of dependent artisans working directly for the courts of the princes, boyars, and monasteries.[41]Aristov, N.Ja. Promyshlennost’ drevnej Rusi. St. Petersburg, 1886, p. 150.

During the course of the 15th-16th centuries, there was a process of differentiation in the leatherworking arts. The rawhide-makers [Rus. сыромятники, syromjatniki], who prepared plain untanned rawhide,[42]Grekov, op. cit., pp. 58-59, 63, et.al. and sole-makers[43]idem., pp. 41, 63. [Rus. подошевники, podoshevniki] became distinct groups of leatherworkers. Based on written records from Novgorod, A.V. Artsikovskij determined that in the late 16th century, out of a general number of 5465 artisans, there were 427 leatherworkers.[44]Artsikovskij, A.V. “Novgorodskie remesla.” Novgorodskij istoricheskij sbornik. 1939 (6), p. 7. They populated a riverfront part Nerevskij End, which became called Kozhevniki [“Leatherworkers”]. It is not without reason that during excavations of Nerevskij End, all along Velikaja Street they found whole estates of leatherworkers.[45]Otchet Novgorodskoj … za 1953 g. Vol. 2, pp. 29, 35, 38. In addition to Velikaya Street, leatherworkers also lived on Lazarevskaja (23 leatherworkers), Glotovskaja, Savinaja (25), Doslana (23), Korel’skaja, Voronjaja, Vodjanaja (38), Chederskaja (57), Nikol’skaja (37) and other streets.[46]Majkov, V.V. Kniga pistsovaja po Novgorodu Velikomu kontsa XVI v. St. Petersburg, 1911, pp. xxvii-xxix.

In the 16th century, the tight connection between Novgorod leatherworkers and the market was characteristic. During this period in Novgorod, there were special shopping arcades where artisans sold their wares, including leatherworkers, rawhide-makers, shoemakers, and sole-makers.[47]Bakhrushin, S.V. Lavochnye knigi Novgoroda Velikogo 1583 g. Moscow, 1930, pp. 29, 36-37, 41-43, 61. It is quite possible that this tight relationship between artisans and the market also existed in earlier periods, including the 14th-15th centures.

We have information that Novgorodian leatherworkers from the 16th-17th centuries sold their wares not only within their own city, but also exported them far to the south and west. Olearius, who traveled through Novgorod in 1635, noted that “in these places they have lots of good arable land and pastures for cattle… Here too they produce excellent juft’, of which they sell a lot.”[48]Olearij, A. Opisanie puteshestvija v Moskoviju i cherez Moskoviju v Persiju i obratno. St. Petersburg, 1906, p. 125.

After the unification of Novgorod to the Grand Duchy of Moscow, many artisans were sent to Moscow, including leatherworkers, shoemakers, et.al.[49]Majkov, op. cit., pp. 22, 24, 43-44, 65, 70. Many leatherworker houses fell empty.[50]idem., pp. 43-44, 202. In the following period, the 16th-17th centuries, Moscow became a major center of leather production, supplying its products to Eastern lands.[51]Fekhner, M.V. “Torgovlja Ruskogo gosudarstva so stranami Vostoka v XVI v.” Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo museja (Trudy GIM). 1952 (21), pp. 64-65.

II. Leatherworking

1. Shoemaking Technology

During archeological studies of medieval Novgorod, remnants of leather shoes have been found in every layer and are the most massive group of finds. Most of all fragments of leather and pieces of leather shoes have been concentrated around shoemaking workshops uncovered in various locations throughout the city.

During excavations in the area around Velikaja Street, an entire mansion of a leatherworker was uncovered, which was inherited from generation to generation from the 11th-15th centuries. Here there were found leather fragments, findings, and entire examples of shoes, in heavy layers reaching up to 15 cm thick.[52]Otchet Novgorodskoj … za 1953 g. vol. 2, pp. 6, 9, 11, 14-18, 20-22, 26, 28-29, 35, 38; Otchet Novgorodskoj … za 1954 g., pp. 2, 48, 62. In 1955, near Velikaja Street, the remains of a shoemaker workshop from the 13th-14th century were found, around which were a multitude of leather shoe fragments, with more than 2000 found within a single square meter.

Table 2 provides a visual overview of the distribution of leather shoes found in 1951-1955 excavations in Nerevskij End by archeological layer.

[jeb: I added headers indicating which century each layer relates to. The further to the right a given column is (ie, the lower the layer number), the later in that century it represents. These mappings are taken from Арциховский, А.В. и Тихомиров, М.Н. Новгородские грамоты на бересте (из раскопок 1953-1954 гг.). Москва, 1958, с. 6 / Artsikhovskij, A.V. and Tikomirov, M.N. Novgorodskie gramoty na bereste (iz raskopok 1953-1954 gg.). Moscow, 1958, p. 6. Layers marked as “turn of the A-B century” are here included in the earlier century block.]

By comparing the abundance of shoe finds in all layers and the many remains of shoemaker workshops in various locations around the city, one comes to the conclusion that the shoemaking industry was widespread in Novgorod. In the early stages of its development, as noted above, shoe-making was not distinct from the tanning industry; this is confirmed by the remnants of both industries found together.[53]Artsikhovskij, Raskopki na Slavjane…, pp. 126-128. In shoemaker workshops from this period discovered on Velikaja Street, no clusters of wool and ash have been encountered.[54]Otchet Novgorodskoj … za 1953 g., vol. 2, pp. 15-18, 38. Written sources note the separate existence of leatherworkers by the mid-13th century.[55]NL1, p. 294. In the 12th-13th centuries, as can be seen on Table 2 by comparison to the 10th-11th centuries, the quantity of prepared shoe products rose sharply.

In shoe workshops found by excavations, in addition to remnants of leather shoes, instruments have been found: knives for cutting leather, straight and curved awls, needles, wooden lasts [Rus. колодки, kolodki], nails, etc. For example, in a 12th-14th century workshop in Nerevskij End, archeologists found wooden lasts (for both adults and teens), iron awls with wooden handles, shoemaker knives, etc.[56]Otchet Novgorodskoj … za 1953 g., vol. 2, pp. 15-18, 38, et.al. It is interesting to note that the tools used by 11th-16th century Novgorodian shoemakers differed little from those of artisanal craftsmen of the 19th-20th centuries.[57]Gdanskij, L. Derevenskij sapozhnik. Leningrad-Moscow, 1917, pp. 1-8, 10.

In the 10th-11th centuries, before the differentiation of shoemakers and leather tanners, an artisan would prepare the raw materials he needed, independent of their eventual use. Later, in the 12th-13th centuries, a shoemaker used material from his customers or bought them from the market. Once he had obtained the necessary material, he would start cutting. For this, he used special knives, differing from everyday knives by their round, wide blades with handles arranged such that the knife would cut as it was pushed away from the user.[58]Kolchin, op. cit., pp. 128-129, illus. 101. In medieval Russian written sources, such knives are called us’moreznye [“shoe-cutters”]. Similar knives have been found in Novgorod, on Knjazha Gora,[59]jeb: In Kiev. in the settlement near the village of Selische, and in other locations.[60]idem., p. 129. The shoemaker would cut the leather after measuring the foot and making a model in the form of a wooden last.

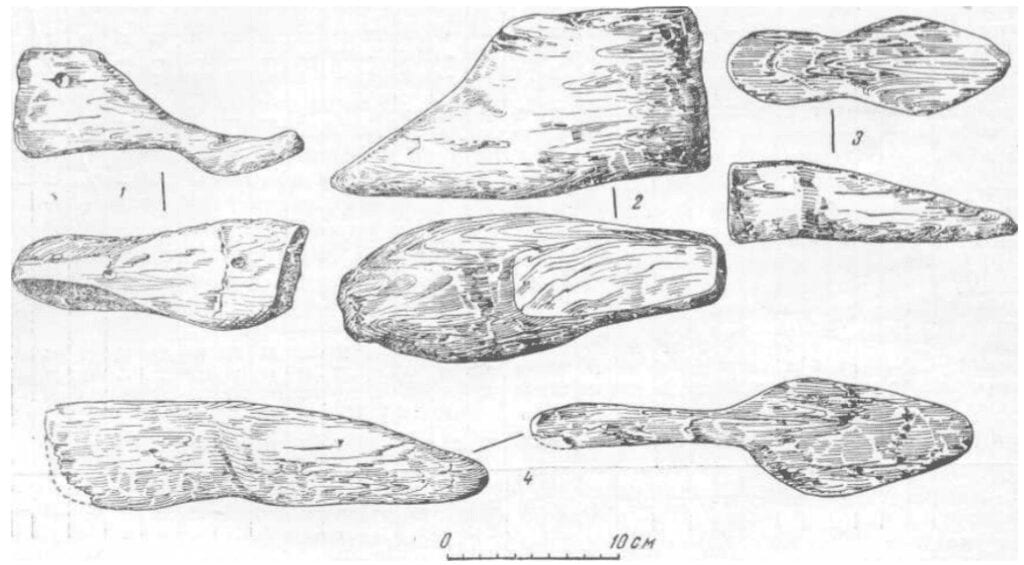

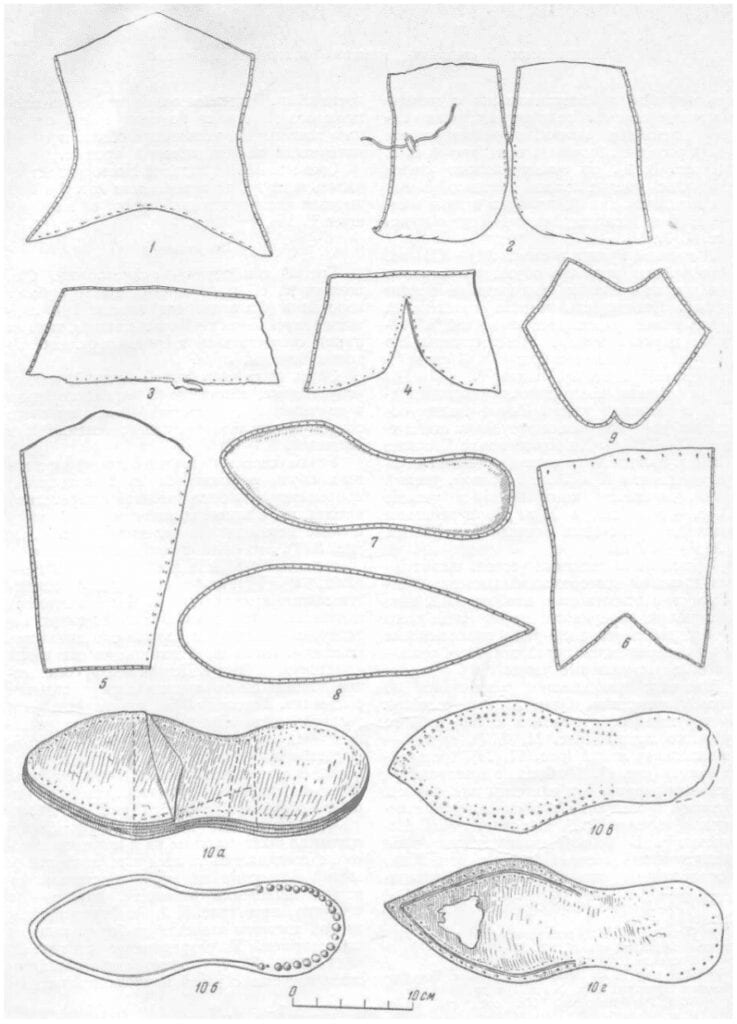

A large quantity of wooden lasts (around 200) has been found in Novgorod, in all kinds of fashions and sizes, made from solid hardwood (linden, birch). Among those found from the 10th-15th centuries, there were simple lasts [Rus. простые колодки, prostye kolodki] made from a single piece of wood, and composite (two-piece) lasts [Rus. составные колодки, sostavnye kolodki] with removable upper sections. The sections of such lasts, as with modern ones, were connected using pegs inserted into specially-prepared holes (Illustration 1, item 1).

Composite lasts undoubtedly served as a model when sewing shoes, as in modern shoemaking. One could also call them “protracted lasts” [Rus. затяжные колодки, zatjazhnye kolodki]. As for simple lasts, the majority were used after the sole had been sewn to the upper. Because the sole and upper are connected using an inverted seam, it was necessary then to invert the shoe and form it around a last. For this, a simple last (or pravilo) was used. Among these, there were lasts for juveniles and adults. The former were more simple in shape and of smaller dimensions. These lasts were 14-16.5 cm in length (Illustration 1, item 5), 4-6 cm wide, and 2.5-4.5 cm tall. The lasts narrowed upward, and were a small block with rounded toe and heel sections, separated by a slightly pronounced transition. There were lasts for both the left and right feet.

The lasts for adult shoes stand out for their wide range of fashions. One set was tall, with a wide lower section. The tops of these kinds of lasts either were tapered, or had a flat rectangular top (Illustration 1, item 2). They reached 9.5-10 cm in height, 8-8.5 cm in width in the front, and around 4 cm wide in the back. Simple lasts such as these are characteristic of the 11th-13th centuries. For the most part, these lasts were symmetrical.

Among the multitude of soles of various shapes, most were completely symmetrical with a wide front that was somewhat rounded. The heels [Rus. пятка, pjatka] of these soles were narrow, and in finished items were raised and sewn between two layers of the shoe’s heel quarter [Rus. задника, zadnika]. Similar shoes date to the 11th-13th centuries. A complete concurrence of wide-nosed, symmetrical lasts for the same type of shoe in terms of both shape and time period speaks to their mutual connection. Judging by asymmetrical examples of leather shoes from the 11th-13th century (for left and right feet), it seems they used the appropriate last for each side. Aside from wide-ended, tall lasts, there were also narrow and low ones, dating to the 13th-14th centuries.

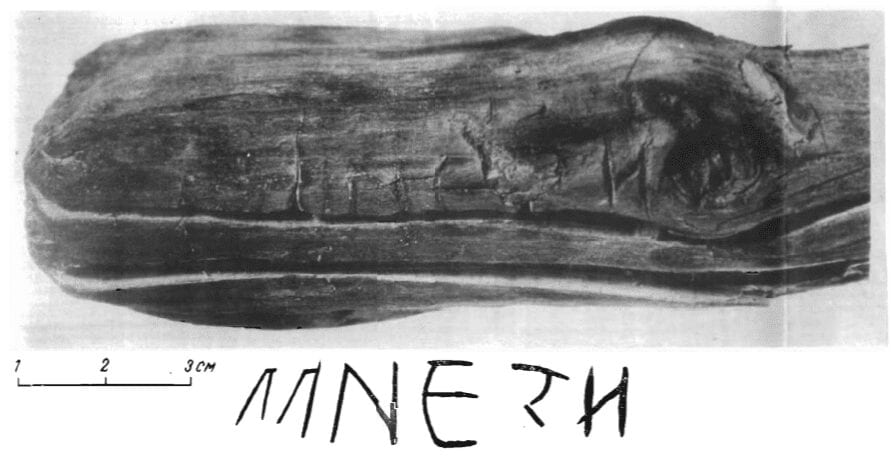

The existence of labeled simple lasts tells us that among them, there were not only simple lasts, but also protracted lasts. In Jaroslav’s Court, they found an example with the inscription “MNEZI” dating to the 15th century,[61]Artsikovskij, A.V. and Tikhomirov, M.N. Novgorodskie gramoty na bereste (iz raskopok 1951 g.). Moscow, 1953,p. 48.[62]jeb: See image JEB3 in the Addenda section for a picture of this last. and another with the letter “R”.

Special shoemaker tools for bootlegs [Rus. голенище, golenishce] have not been found. It seems that they may not have existed in the 11th-15th centuries.

The cut out sections of the shoe were sewn together with thread, which was waxed for strength. Blocks of wax have repeatedly been found during excavations.[63]Otchet Novgorodskoj … za 1953 g., vol. 1, pp. 15, 27. Threads were made from linen and hemp fibers by a member of the shoemaker’s family, as we can see from the frequent finds in shoemaker’s huts of hackles [Rus. гребень, greben’], scutchers [Rus. льнотрепалка, l’notrepalka, lit. “flax beater”], spindles, etc.[64]idem., vol. 2, pp. 15-17, et.al.

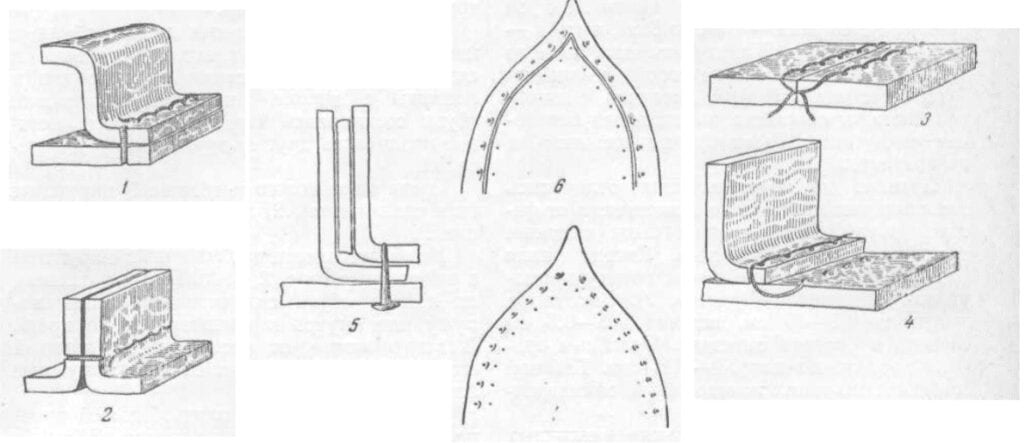

A review of the individual pieces of shoes and the complete item, it’s possible see a difference in how the pieces of the shoe uppers are connected, as opposed to how the sole is connected to the upper. The leather blanks were united using stitches which differ in their method of application. Among these stitches, we can highlight: 1) saddle stitching [Rus. наружный шов, naruzhnyj shov, “outer stitch”, or сандальный шов, sandal’nyj shov, “sandal stitch”], the hidden stitch [Rus. выворотный шов, vyvorotnyj shov, “inverted stitch”], and blind stitches [Rus. потайный шов, potajnyj shov].[65]The names of the stitches are from: Komissarov, N. and Fridljand, A. Kratkij spravochnik obuvschika i kozhevnika. Moscow, 1952.

1 – Saddle stitch, 2 – hidden stitch, 3 – blind butt seam, 4 – blind seam with a seam allowance, 5 – joining the inner and outer heel caps to the sole, 6,7 – blind seams on soles.

The simplest of these were the saddle and hidden stitches (Illustration 2, items 1-2). When doing these stitches, the leather pieces were placed either face to face or inside to inside, and were sewn along the edge. Depending on the placement of the outer face of the blank, this would create either a saddle or hidden stitch.

Blind stitches are distinguished by their strength and their difficulty of execution. Larger thicknesses of leather allow one to join pieces of leather without piercing all the way through the leather. These stitches are done in two ways:

- The sewing of the pieces was done with them lying end to end, or abutting each other, a so-called “butt seam” [Rus. тачный шов, tachnyj shov]. These stitches were used to join upper pieces of footwear (boot legs, the leg to the vamp [Rus. головка, golovka], the leg to the heel quarter, etc.] (Illustration 2, item 3).

- The pieces were joined with an allowance for the seam. In this case, the edge of one part was superimposed over the edge of another (Illustration 2, item 4). This was typically used to join the sole to the upper. On soles sewn with this stitch, two rows of holes are seen. On some soles, we see an incision between the two rows of holes (Illustration 2, items 6-7). The purpose of this incision is so far unclear. Was this incision done to make it easier to fold the edge? The majority of soles were sewn with this stitch.

Blind seams required using a curved awl and thread with bristles [jeb??: Rus. щетинка, schetinka] on the end.

The stitches described above for joining shoe pieces used by Novgorod shoemakers from the 11-16th centuries are completely identical to those used by artisans in the 19th-early 20th centuries.

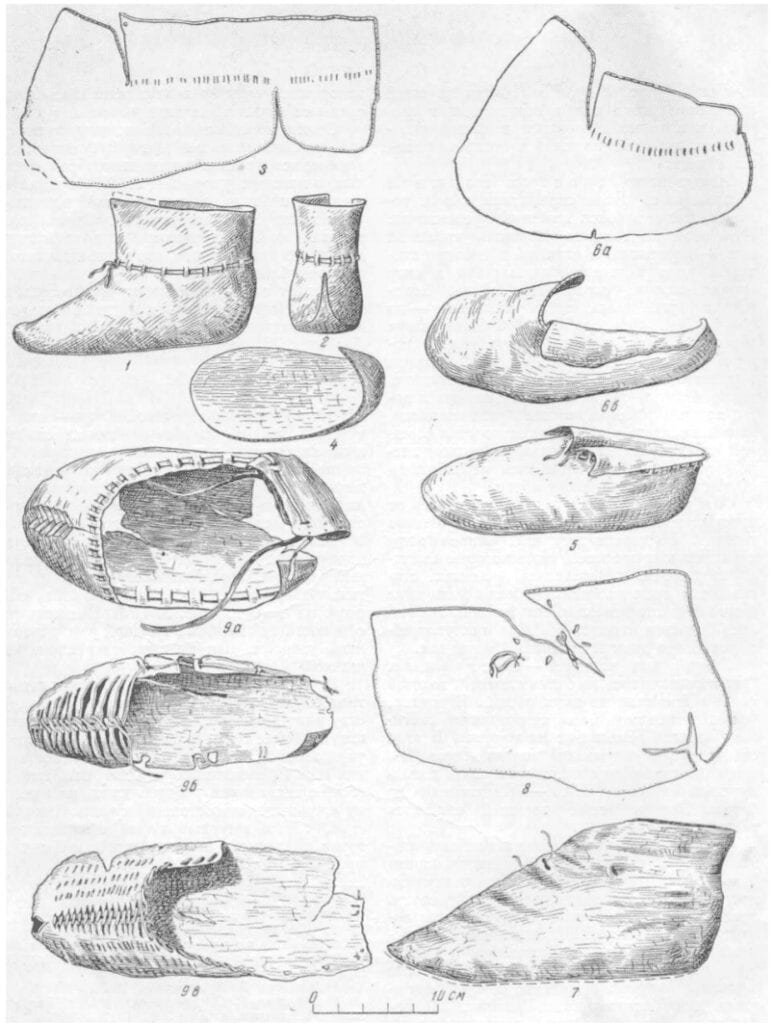

While reviewing the multitude of remnants of leather shoes, we managed to notice differences in their style, cut and methods of sewing, that is, to define the technology used by Novgorod artisans for shoemaking, starting in the 10th century. Independent of fashion, we were able to identify 4 types of shoe: 1) bog shoes [porshni], 2) soft shoes [mjagkie tufli], 3) ankle boots [polusapozhki], and boots [sapogi]. Boots, as opposed to the prior three categories, had more rigid soles and a harder heel quarter.

Bog Shoes (поршни, porshni)

Bog shoes were the simplest type of shoe, similar in appearance to bast shoes [lapti].[66]jeb: A very inexpensive form of shoe made from woven bast (linden bark). In medieval Russian written sources, such shoes were called “praboshni cherev’i” or just “cherev’ja,”[67]PSRL, vol. I, p. 123, 195. that is, shoes made from the soft hide obtained from the belly [chrevo] of an animal. In Dal’s Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language, we find an interesting note that the word porshni is related to the adjectives porkhlyj (“crumbly”), poroshlivy (“powdery”), and rykhlyj (“friable”),[68]Dal’, V. Tolkovyj slovar’ zhivogo velikorusskogo jazyka. Vol. III. St. Petersburg-Moscow, 1907, p. 847. which indeed agrees with the properties of this type of leather. The same dictionary also says that bog shoes were not sewn, but rather were made from a single piece of rawhide or hide, gathered up on a drawstring.[69]idem., p. 849. Observations of bog shoes from Novgorod completely confirm these observations.

With all their simplicity, bog shoes can be divided into three types, based on their construction: 1) simple (Illustration 3, item 9а), 2) openwork (Illustration 3, items 9б and 9в), and 3) composite.

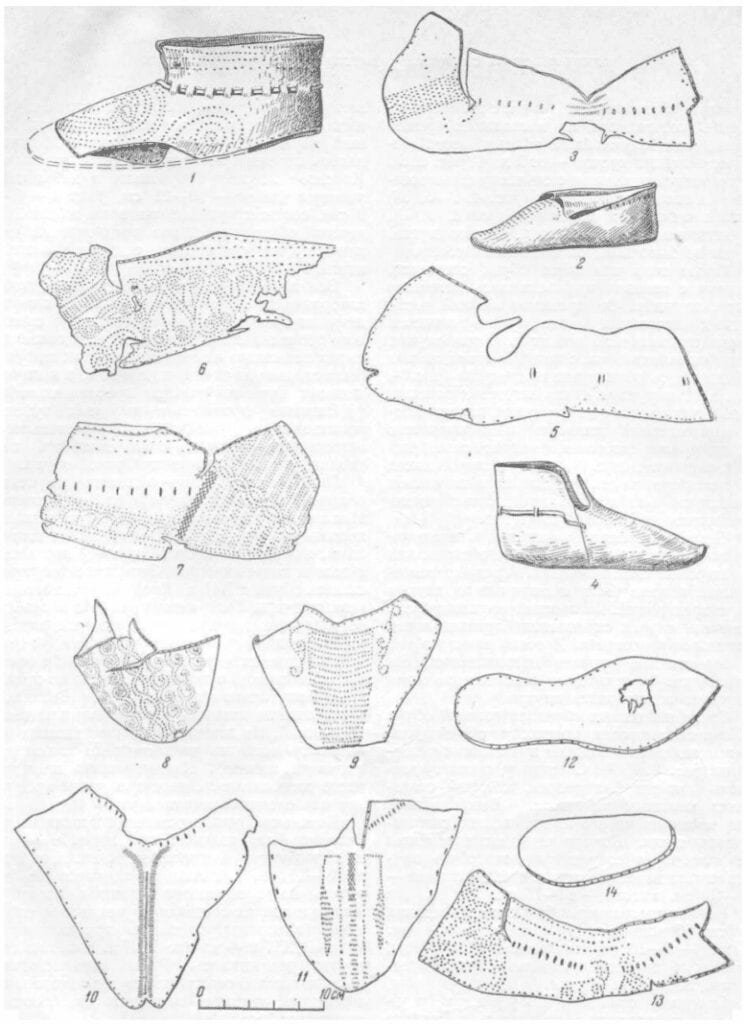

1 – child’s bootie (23-27-187); 2 – same, side view; 3 – same, pattern; 4 – sole from a simple soft shoe (24-29-132); 5 – shoe (15-18-387); 6a, 6б – same, part of the pattern; 7 – soft shoe (10-11-568); 8 – same, part of the pattern; 9а – simple bog shoe (7-5-942); 9б – openwork bog shoe (12-17-350); 9в – openwork bog shoe (13-17-17)

The first two types of bog shoes were made from rectangular pieces of leather of various thicknesses (2-2.5 mm). The length and width of the selected piece was determined by the dimensions of the foot and allowances for the height of the heel, upper and mouth. The edges of the leather were bent upward at the toe and heel and butt-stitched together. (Illustration 7, item 1) The mouth of these bog shoes had vertical slides along the upper edge, into which a leather lace was placed to serve as a drawstring and tie the shoe to the foot.

Most simple bog shoes were made by attaching the upper, heel and sides using a leather drawstring. At the same time, a decorative stitch was used on the upper [Rus. плетешок, pleteshok, “whip stitch”?] and the front and sides would form small pleats which would adorn the shoe. The drawstrings were quite long, up to 85-100 cm. They tightened the sides of the shoe, and were tied around the calf over one’s pants or stockings. This string would tightly connect the front and heel of the shoe. The width of the toe and heel corresponded to the size of the foot, but quickly the shoe would fray and start to fall off the foot. To fix this, the edges of the shoe were tightened with a transverse strap in front of the calf, which was threaded through holes on either side of the shoe.

Openwork bog shoes differed from simple ones in the more complex design of the shoe upper. The openwork was created by applying rows of parallel cuts, through which a ribbon was threaded in the center, intertwining and tightening the edges. There were also long narrow bands along the side. These bog shoes were quite graceful. These were made of thinner and softer material.

The third type was composite bog shoes. They were made from very dense, thick leather and consisted of two pieces. The thicker leather certainly would not have allowed to gather the edges on a drawstring. The corners of the blank, therefore, were cut and instead an additional, triangular piece of leather was inserted using a butt seam. The heel of these shoes was also sewn with a blind seam.

Bog shoes, as one of the easiest forms of footwear, was worn by men, women, and children. The simplicity of its cut and and uncomplicated exterior decoration allows us to suppose that this type of footwear was used primarily by the poorest classes of society. If the sole were to become overly worn, they would attach leather patches, attached with leather laces or plant (matte) fibers. Sometimes patches were attached to worn areas on the sides of the shoes. In some cases, only seam holes remained as signs that these patches had existed.

Among the numerous examples of bog shoes, varying in size and fashion, no two-layer or multi-layer bog shoes as mentioned by L.I. Jakunin[70]Jakunin, op. cit., p. 39. have been found. That author incorrectly identified a two-layer sole. Multiple examples of these stratified soles have been found in Novgorod. This is a sign that the leather was insufficiently tanned.

Bog shoes were known not only in Novgorod, but also in other medieval Russian cities: Grodno,[71]Voronin, N.N. “Drevnee Grodno.” MIA. 1954 (41), pp. 61-62, illus. 26, items 4-5. Staraja Rjazan’,[72]Mongajt, A.L. “Raskopki Staroj Rjazani.” Po sledam drevnikh kul’tur: Drevnjaja Rus.’ Smolensk,[73]Dig by D.A. Avdusin, 1955. Pskov,[74]Dig by G.P. Prozdilov, 1954. State Hermitage Museum, Inv. no. 559, 910, 930, 1300. and Staraja Ladoga.[75]Dig by V.I. Ravdonikas, 1947. State Hermitage Museum, Inv. no. 1106.

Soft Shoes (мягкие туфли, mjagkie tufli)

The second type of Novgorod footwear, soft shoes, are characterized by their soft, comfortable fit and their sewn-on soles. In their form, these shoes are reminiscent of modern baby booties, but with only one forward cut and with standing or lightly bent sides. Most of the examples of this type of shoe have a tightening lace around the ankles, running through a series of vertical slits and tied in front, on the rise (Illustration 3, items 1-5). The outer surface was either smooth, or decorated with designs carried out using stamping, embroidery, or leather carving.

Depending on the intended use of the shoe, various qualities of material were used. Thick, dense cowhide leather was used for the simplest shoes, without any decoration. This was, certainly, everyday footwear worn by artisans and peasants. Softer and thinner leather was used to make openwork and more costly footwear. Both types were cut precisely to the length and width of the foot, with small seam allowances.

The uppers of the majority of plain shoes consisted of several pieces of leather, sewn together with blind butt seams. The number of these pieces ranged from 2-4 (Illustration 3, item 5). Individual examples have been found which were made from an entire piece of leather (Illustration 4, items 2-5, 13) or with small inserts (Illustration 3, items 1, 3). For shoe blanks made from a single piece of leather, the seam was one the side rather than at the heel.

After the upper of the shoe had been sewn together, the inside-out shoe was sewn to the sole using a blind seam. The shape of the sole was based on the curvature of the lower part of the back halves of the upper. If the halves had straight edges, then a normal sole was attached (Illustration 4, item 12). If the blank had curved edges, then the sole had a pointed sole with the end turned upwards. The latter was sewn into the space between the edges of the blank, and created an idiomatic heel (Illustration 3, items 2, 4). The pointed end of the sole was joined with a vertical blind stitch with a seam allowance. These soles were completely symmetrical in shape.

After the sole had been sewn onto the upper, the shoe was turned rightside-out and was stretched over a wide-nosed last. Among the soles we reviewed, there were a few that were sewn from two or even three pieces. Among plain shoes, there were a few cases where the sides where the sides of the upper were fastened with leather laces. In the majority of cases, plain shoes were made without a lining. In some examples, the edges of the sides were sewn with an inner seam.

Amongst the discovered examples of completed footwear, there were a few examples which stand out from the overall set because of their unusual cut and large size (Illustration 3, items 7, 8). The front of these shoes had a slit along the instep [Rus. подъем, pod’em], which was laced. These were made almost from one complete piece, with a seam in the back. There was no lace at the ankle. Judging by the size, these belonged to an adult man. They were 25-28 cm in length, 12-16 cm in height.

The small dimensions of the majority of soft shoes (lengths from 10-15 cm to 20-22 cm, height 7-10 cm) suggests that they were primarily worn by women, teens, and children.

The main difference between plain shoes and openwork shoes was in the finish of the outer surface and partially in their cut (Illustration 4). These shoes had a toe that was slightly bent and raised. This was achieved by making a small, 1-1.5 cm cut at the end of the upper, into which the end of the sole was inserted. The beautiful outer decoration and small sizes (length 10-21 cm, height 5-9 cm) suggests these shoes were worn by women, teens, and children.

All openwork shoes had a lining which was carefully sewn to the upper inside edge of the sides of the shoe, without piercing all the way through the outer layer of leather. As these linings were made of fabric, none have survived in any of the examples from excavations, but signs of them can be easily seen in the holes left in the leather.

The outer design of these openwork shoes was made by cutting the leather before final construction of the shoe. We can make out several techniques for this decoration.

The simplest form of decoration was made by creating three parallel cuts on the shoe upper. Later, they had zigzag lines with uneven edges made by small stamps which did not pierce through the leather, but only made impressions on the surface. This style was used to decorate shoes in the 12th century. Aside from these carved lines, there were also cuts that went all the way through the leather, created by a sharp knife and running in parallel lines along the upper. Subsequently, carved lines began to be combined with embroidery and stamping. Previously, the decoration had always been in the center of the upper. The embroidery and stamping allowed decorating between the carved lines. On items which have survived to our time, this embroidery is visible only as a row of pierced needle holes. Originally, it appears it was probably rows of crosses or a complex meshwork.

1 – embroidered shoe (18-17-539); 2 – child’s embroidered shoe (14-13-499); 3 – pattern for #2; 4 – child’s embroidered shoe; 5 – pattern for #4; 6 – part of an embroidered shoe (14-20-231); 7 – same (28-33-144); 8 – same; 9 – same (13-13-615); 10 – upper for a shoe, decorated with carving and stamping (21-25-177); 11 – part of an embroidered shoe (2-26-173); 12 – sole from an openwork shoe (20-23-211); 13 – upper from an embroidered child’s shoe (16-20-23); 14 – sole from the same shoe (#13)

Decorating shoes with wool and silk thread was a beloved method of decorating shoes among the Novgorodians; it appeared in the 10th-11th centuries. We can often see the remains of thread on the surface of leather items. Embroidery patterns consisted of various combinations of crosses, zigzags, triangles, etc. In the 12th-early 13th century, it became more intricate. Rows of parallel lines of needle holes were connected into all kinds of whirls and tendrils, going down onto the sides of the shoe.

The 13th century was the pinnacle of openwork embroidered footwear. The entire top of the shoe would be covered with delicate vegetative and geometric designs. These might include luxurious lilies, intertwining plant stems, flower buds, etc. (Illustration 4, items 6, 8, 13; Illustration 8, item 2). Geometrical designs may have included entire bands of zigzag or wavy lines, figure-8 braids, rows of concentric circles, etc. (Illustration 4, items 7, 11).

In 12th-13th century layers from medieval Grodno, a leather shoe was found which was analogous in cut and manufacture to Novgorodian soft shoes. The upper of the Grodno shoe was likewise decorated with embroidery.[76]Voronin, op. cit., p. 62, illus. 26, items 1, 2. Embroidered shoes, identical in cut to those from Novgorod, were also found in Pskov,[77]Dig by G.P. Grozdilov, 1954. Hermitage, Nos. 163, 369, 380, 712. Smolensk,[78]Dig by D.A. Avdusin, 1955., and Staraja Ladoga.[79]Dig by V.I. Ravdonikas, 1947, Hermitage, Nos. 1900 et.al.

We also find stamped patterns on Novgorod openwork shoes. The earliest shoes with these patterns were found from the 11th-12th century. In Jaroslav’s Court, in 1948, a stamped pouch [Rus. кошелёк, koshelek] was found dating to the late 10th century. As such, this technique of stamping leather appeared before the 11th century, at least as early as the 10th century. But, the majority of stamped items dates to the 14th-15th centuries.

The majority of stamped designs carried out by medieval Novgorod artisans were noted for the flatness of the design, barely visible above the surface of the leather. Most frequently products had rows of parallel or crossing lines, curls, and less frequently, vegetative designs.

The stamped designs differed by the method of stamping. Some of these consisted of triangular imprints from a small, toothed stamp (Illustration 11, items 4, 7), another of solid lines (Illustration 11, item 14), and a third with scales (Illustration 11, item 13). Judging by the Novgorod stamped patterns, they were applied, or rather “imprinted,” using rigid stamps, and not by pressing the leather with thick threads as suggested by M.G. Rabinovich.[80]Rabinovich, op. cit., p. 54, illus. 26, item a. Our opinion is supported by the prints themselves, which are located only on the front surface of the leather. Further accumulation of archaeological material should help us find these hard stamps and to illuminate this very interesting technological process.

Among the leather items found in Novgorod were also found some which were carved in a “pseudo-stamped” pattern, looking like scales.[81]State Historical Museum, No. 82582.

Ankle Boots (полусапожники, polusapozhniki)

The third type of footwear was ankle boots. These were similar to normal boots, but with shorter bootlegs (without a lining). The backs were not as stiff as regular boots, as they lacked stiffeners [Rus. твердая прокладка, tverdaya prokladka] made of leather, birch bark, or bast.

Footwear of this type consisted of two types: 1) soft ankle boots, consisting of an extended upper and a sole, and 2) ankle boots of a more complex cut, with an upper, heel, bootleg, and sole.

For soft ankle boots, the upper consisted of 2 halves, with one for the upper and one for the heel quarter, both of which connected to the bootleg (Illustration 5, item 1; Illustration 8, item 7). These pieces were different in shape. In order to make these boots, it was necessary to have extended lasts which matched the shape and dimentions of the customer’s leg. The pieces of leather were soaked in water, stretched over the last, stitched together, and then hammered with a mallet. Once the leather dried, it would retain the shape of the last. The upper pieces, joined with a butt seam, were sewn to the sole inside-out. The finished shoe was then turned right-side out and straightened out. The bootlegs were not tall – 14-15 cm (Illustration 5, item 6). The soles of ankle boots were completely identical to those of soft shoes, came in both wide and blunt-nosed styles, and lacked a well-defined ankle (Illustration 5, items 7, 8).

1 – back half of an extended ankle boot (18-25-91); 2, 3, 4 – heel quarters from ankle boots (21-26-232, 19-24-236, 22-28-115); 5 – part of a boot leg (8-8-565); 6 – half of an ankle boot leg (13-17-294); 7, 8 – soles from ankle boots (12-16-304); 9 – upper from an ankle boot (10-6-687); 10а, 10б – multi-layer soles from boots, pierced with stitching holes (5-11-46, 15-18-387); 10в, 10г – single-layer boot soles with blind stitch holes (7-10-412, 7-10-878)

Complex ankle boots had bootlegs which were sewn from 2 halves, joined by either a butt seam or a hidden seam. Some were gathered at the ankle by a drawstring, others at the top of the bootleg (Illustration 5, items 2, 6). The shape of the sole was determined by the type of heel quarter. Soles with a narrow, raised back were sewn into a slit cut into the heel quarter from below with a blind seam (Illustration 5, item 4).

If the back quarter had a smooth lower edge (Illustration 5, item 3) then a normal type of sole was used, similar to those of soft ankle boots. The second style of ankle boots was a prototype for modern boots. They existed in the 10th-14th centuries.

Ankle boots with a raised sole back in the heel were also found in Staraja Ladoga.[82]Digs from 1947 and 1950. Hermitage, inventory Nos. 537, 1120, 1419, 1822.

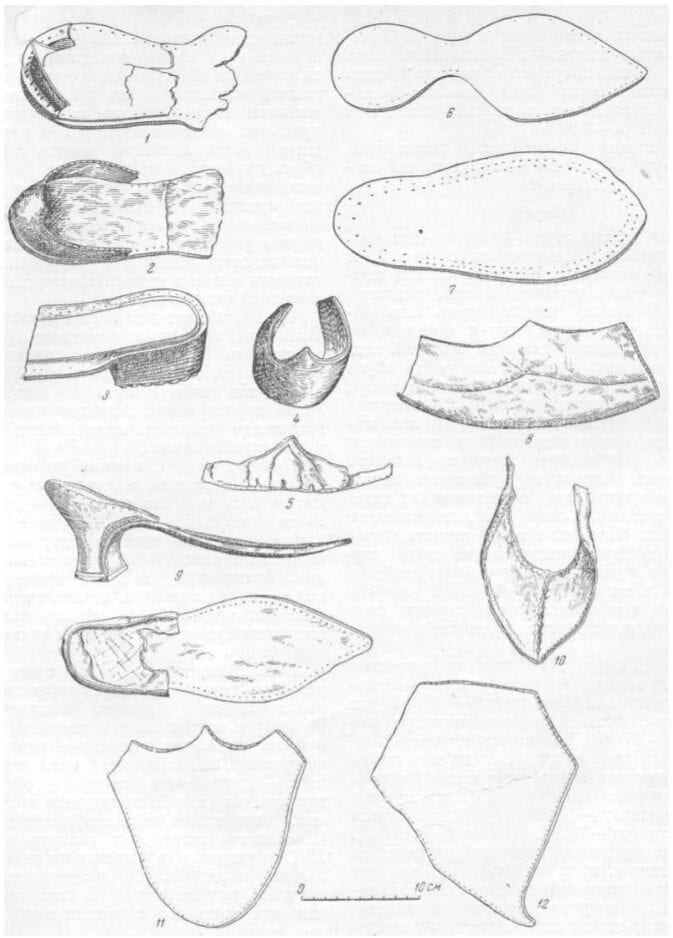

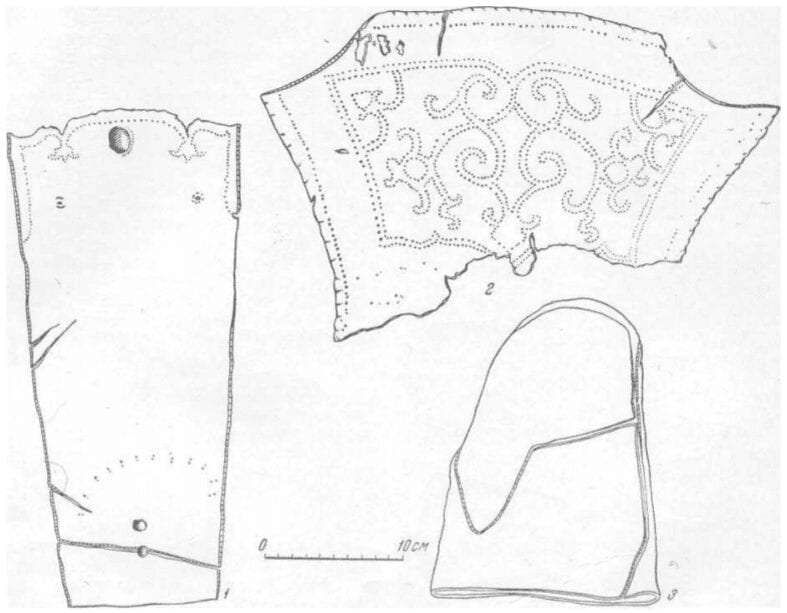

Boots (сапоги, sapogi)

The fourth type of footwear, boots, were a bit more complex to manufacture (Illustration 7, item 4; Illustration 8, item 1). The presence of several components (bootlegs, upper, heel quarter, sole, heel [Rus. каблук, kabluk] illustrates the need to use various types of leather and required the shoemaker to be skilled at precisely joining these parts. The upper was made of softer, more pliable leather, while the sole was made of rigid, thick leather. A lining [Rus. поднаряд, podnarjad], which differed in its thickness and flexibility, was sewn to the upper and bootleg. The required stiffness in the heel quarter was achieved by adding layers of stiffening, made from leather, birch bark, or bast. Creating boots required taking accurate measurements of the foot and leg, including the length of the foot, its width in 3 locations (the breadth [Rus. пучковая, puchkovaja] at the widest part, the instep [Rus. геленочная, gelenochnaja] at the narrowest part, and the heel breadth [Rus. пяточная, pjatochnaja] at the center of the heel), the ankle circumference, and the height of the calf and instep.

The Bootleg (голенища, golenischa). All Novgorod boots had a singular peculiarity: short bootlegs. Their high was 17-22 cm, with only individual examples found measuring 25-27 cm. The majority were made up from 2 pieces, joined at the sides in blind or hidden seams. The upper end of the bootleg was wider than the bottom (upper widths were 16-20 cm, while at the bottom they were 10-14 cm) (Illustration 5, item 5).

In addition to two-piece bootlegs, one-piece legs were also found, but they were less common since cutting out a blank required more material that was of better quality. The seams on such bootlegs were on the side, along the inseam. In one case, remains of a very long one-sided bootleg were found, representing the widest part of a boot that extended above the knee. The fragmentary nature of the find does not allow us to determine the complete form of this boot, but we believe it to have been a unique hunting boot. On the front upper edge there were signs of needle holes, where a leather strap was once attached, used to tie the boot to wearer’s clothing. The upper parts of the bootleg (and somethings near the ankle) there were sometimes rows of vertical slits, into which would been threaded leather laces used to tighten the boot to the leg. A lining was sewn to the inner side of the bootleg, as seen from a series of blind holes along the top of the bootleg.

1 – boot heel with an attached interior heel quarter (6-7-962); 2 – boot heel with an attached exterior heel quarter (3-3-975); 3 – stacked heel with part of a sole (4-13-757); 4 – heel stiffener made from 3 layers of birch bark (5-11-50); 5 – heel stiffener made from sheets of leather (23-27-301); 6 – part of a multi-layer heel from a high-heeled shoe (9-11-410); 7 – boot sole with blind stitching (3-9-245); 8 – outer heel quarter of a boot (7-8-940); 9 – boot sole with a thick wooden heel (State Historical Museum); 10 – lined boot upper (6-7-962); 11 – blunt-nosed boot upper (20-23-401); 12 – pointed-toed boot upper (22-24-403).

Among the large number of various boot parts, boot legs number are found least often. This is not coincidence. When other parts of the boot wore out, it seems, the boot legs were not thrown out, but rather were used to repair other shoes, or were reused in a new pair of boots. It is known that instances of this second use exist even in modern times.

Uppers/vamps (головки, golovki). Boot uppers came in two styles: blunt-nosed and pointed with a raised tip. The length of the upper ranged from 13-24 cm (Illustration 6, items 10-12). Blunt-nosed uppers were made from plain, coarse leather, while pointed-nosed uppers were made from leather that was softer and thinner. Most uppers, aside from those made from thick leather, had a lining which were attached using a blind stitch at the toe, and which consisted of one or two layers of leather (Illustration 6, item 10).

The method for attaching the upper to the sole differed, depending on the thicknesses of the two pieces. Uppers made of thick leather were attached using a simple saddle stitch; otherwise, they were attached using a hidden stitch. The top edge of the upper, whether straight or curved, determined the curvature of the bottom edge of the bootleg, as well as the angle of the inner edge of the heel quarter. The outer surface of the upper was decorated in the 15th-16th centuries with stamped parallel lines (Illustration 7, item 5) or with rows of studs with small round heads. When reusing scraps of material, the shoemaker would sometimes join multiple pieces to create an upper.

Heel Quarters (задники, zadniki). Boots had a doubled heel quarter, consisting of 2 layers of leather which were sewn together on the inside using a blind stitch forming a pocket. In order to give the boot a great deal of stiffness, this pocket was filled with pieces of leather, birch bark, or bast (Illustration 6, items 4, 5). The lower edge of both layers of the heel quarter were bent outwards and attached to the sole using a saddle stitch (as in modern sandals; Illustration 6, items 1, 2).

In the 15th-16th centuries, the outer surface of the heel quarter was decorated, stamped with rows of horizontal lines. This method of decorating the heel was also used in Moscow.[83]“Izuchenie drevnego proizvodstva kozhi…”, p. 43.

Soles (подошвы, podoshvy). It appears that the shape of the sole was determined by that of the upper. They included blunt-nosed and pointed-nosed soles.

Soles were made from multiple layers of thin leather (Illustration 5, 10а), and were attached to the upper using a saddle stitch. For durability, this stitching went through a special groove on the bottom of the sole. In order to prevent rapid wear of the front and back of the sole, iron or brass hobnails with broad, round heads were inserted into these locations (Illustration 5, items 1-6). These nails were up to 1-1.5 cm long, with heads 0.3-0.7 cm in diameter. The nails were square in cross-section. Heel protectors in the form of iron brackets have been known since the 14th century.

Thick soles were attached to the upper and heel quarter in a combination of methods. The area up to the heel was attached using an inner, hidden seam. The heel was attached using a saddle stitch (Illustration 5, items 10в-г; Illustration 6, item 7).

The large sizes of boots found in Novgorod (from 12 to 30 cm in length) suggest that they belonged to men or male teens. Judging by the material used, footwear of this type was worn by princes and boyars, as well as soldiers.

The majority of 11th-13th century Novgorod boots were without heels. However, 14th century soles with narrow heel sections and remains of stacked heels (made of leather or iron) indicate the appearance at this time of footwear with medium and high heels (Illustration 6, items 3, 6).

Technology-wise, the manufacture of boots in Novgorod did not differ an any way from that of Moscow[84]“Izuchenie drevnego proizvodstva kozhi…”, p. 39. or Pskov.[85]Dig by G.P. Grozdilova, 1954. Hermtage, inv. nos. 217, 288, 422, 484, 1031, 1056.

To close out this description of the technology of shoemaking in 11th-16th century Novgorod, we should include the following:

- Production of leather footwear in Novgorod started in the 10th century.

- The technology of shoemaking in the period under review reached a high level of development. The principle methods of cutting and sewing leather shoes used in the 11th-16th centuries were distinguished for their great skill and were preserved almost unchanged to modern times.

- Novgorod shoemakers created 4 principle types of shoe (bog shoes, soft shoes, ankle boots, and boots). The last of these, boots, are still widely used today.

- Over the many-century existence of this industry, the craftwork noticeably improved in the methods of decorating the outer surface. The simpler carving and embroidery on 11th-12th century shoes turned to complex openwork compositions in the 12th-13th centuries. In the 15th-16th centuries, boots with stamped designs on the upper appeared.

- The similarity in cut and design of various types of Novgorod footwear with that of other medieval Russian cities (Grodno, Staraja Rjazan, Smolensk, Pskov, Staraja Ladoga, Moscow), indicating that there was a common set of technology for shoemaking in Rus’.

2. Chronological Classification of Leather Footwear

The precise stratification of the cultural layers of medieval Novgorod allows us to group all of the remnants of leather footwear in our possession by century, and in this way, to reveal the main type of shoes worn in each chronological period. Table 3 provides the results of chronological count of the various types of shoes by period. From it, one can see at a glance when individual types of shoes came into or fell out of use.[86]The table is comprised of material from excavations in Nerevskij End carried out from 1951-1955. Statistics for the 10th and 16th century are incomplete, due to the poor preservation of footwear from these times.

10th-11th century footwear

The earliest examples of leather footwear from Novgorod were found in layers from the late 10th-early 11th century. These included bog shoes, soft shoes, ankle boots, and boots (Illustration 8).

The first type of shoe – bog shoes – is represented by an insignificant number of examples. It may be that they were not preserved in large numbers from such a distant time considering that the majority were made from simple rawhide. These shoes from the 11th century were plain. This type of shoe was also known in the West. For example, similar shoes were found in 10th century tombs near Oberflacht in Swabia.[87]Vejs, G. Vneshnij byt narodov s drevnejshikh do nashikh vremen. Vol. II, part 2. Moscow, 1975, p. 161, illus. 227.

Most soft shoes in this period were plain, but openwork shoes were also made, which had their surfaces decorated with embroidery and carving combined with stamping (Illustration 4, items 7, 10). Various types of braid patterns were a favorite motif of medieval Russian decoration. They are found on fabric,[88]Prokhorov, op. cit., pp. 85, 86. bone,[89]Izjumova, S.A. “Tekhnika obrabotki kosti v d’jakovskoe vremja i v drevnej Rusi.” KSIIMK. 1949 (30), p. 18, illus. 2, item е. wood, and stone. In Novgorod, knotwork like this is known on wooden items starting as early as the 10th century.[90]Janin, V.L. “Velikij Novgorod.” Po sledam drevnikh kul’tur. Drevnjaja Rus’. Moscow, 1953, p. 239.

In 11th century Russian painting, footwear analogous to Novgorod shoes are known.[91]Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1953, p. 39. Shoes similar to these soft shoes were worn in the 10th-11th centuries not only in Rus’, but also in Byzantium[92]Vejs, G. op. cit., p. 55, 57, 62, illus. 34, item o. and in the West.[93]idem., p. 168, illus. 231, item в.

In the 10th-11th centuries, short, soft ankle boots with extended bootlegs and ankle boots with detachable bootlegs. Ankle boots with short, flared bootlegs reminiscent of the Scythian ankle boots depicted on the Kul-Ob vase.[94]Prokhorov, op. cit., pp. 22-23. A leather lace was sometimes used to tighten these boots at the ankle.

Compound soles, blunt-nosed uppers, and plain bootlegs were characteristic for boots at this time. There were also boots of a more fashionable cut, with a narrow upraised toe, but these were not common. Compared to subsequent periods, the quantity of shoes found from the 10th-11th centuries was quite small. Footwear of this type had only just appeared in Novgorod and was not yet widely in use. In the 11th century, boots were also worn in the south of Rus’, as we can tell from the aforementioned miniature from the Svjatovlav Izbornik of 1073.[95]Kondakov, op. cit., pp. 40-41. The prince and his son are depicted wearing brightly-colored (and most likely, saffian) boots with pointed, raised toes.[96]jeb: See image JEB4 in the Addenda section for a photo of this miniature.

1 – boot (Jaroslav’s Court, found 1948); 2 – openwork shoe (State Historical Museum, inv. no. 3003); 3,4 – view of (2) from above and rear; 5 – child’s plain booty (21-25-226); 6 – bog shoe (5-13-172); 7 – ankle boot (18-25-91)

12th century footwear

For the 12th century, the following types of footwear are characteristic: bog shoes, soft shoes, ankle boots, and boots.

Bog shoes, as in the previous period, are represented by a small number of examples. These include both plain and composite shoes. In the 12th century, these were worn not only in Novgorod, but also in other cities of medieval Rus’. For example, leather shoes were also found in Staraja Rjazan’. Judging by a description of the shoe found there, it was similar to a Novgorod bog shoe in appearance (but not in cut). It “was cut from two whole pieces of leather, covering the top and heel of the foot. At ankle height, the upper part of the shoe was pulled together by a narrow cord or strap which ran through small cuts running around the upper part of the shoe.[97]Mongajt, op. cit., p. 315.

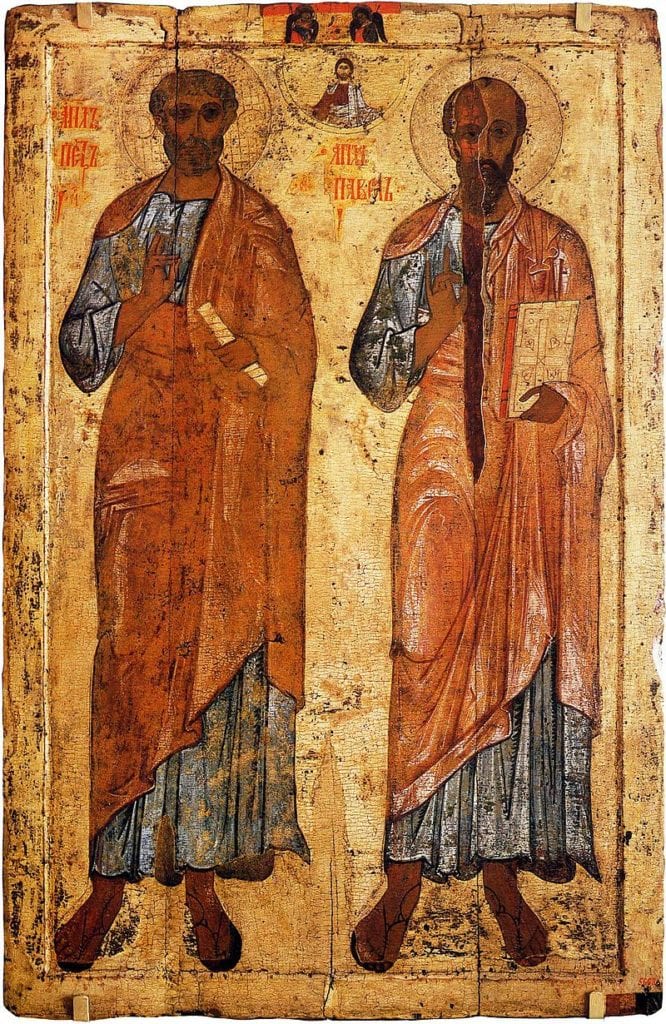

Bog shoes that were similar to those from Novgorod (i.e., simple) were also found in medieval Grodno in a layer from the 12th-13th centuries,[98]Voronin, N.N. “Na beregakh Kljazmy i Nemana.” Po sledam drevnikh kul’tur. Drevnjaja Rus’. Moscow, 1953, p. 281. and in Pskov. Bog shoes similar to the most simple ones from Novgorod are depicted on a 12th-century icon from Belozersk.[99]Russian Museum, Leningrad, Hall 1, “Peter and Paul” icon, 12th cent.[100]jeb: See image JEB5 in the Addenda section for a picture of this icon. The icon is now dated to the early 13th century.

Judging by the information in medieval written sources, bog shoes were also known in the south of Rus’. They were worn in both the summer and winter. The Laurentian Chronicle includes the following message: “and during Matins, they would enter, Isaak first of all, firmly and motionless, when winter was ripe and the frosts were fierce, standing in his worn-down bog shoes, as if his nose was frozen to stone.”[101]PSRL, vol. II, p. 195.

The most widespread type of footwear in the 12th century were simple and openwork shoes. However, there was a different fashion of shoe, between the two, with a cut on the forward instep or with a tongue (Illustration 3, item 7; Illustration 4, item 4). In outer appearance, this footwear was similar to modern slippers (without the hard heel or upper), or to galoshes with a tongue.

Of particular interest are the openwork shoes and the great variety of their decoration. Some of these were decorated with various designs – linear, zigzags, etc. – in silk or woolen thread. Some of the more widespread designs were vegetative, consisting of various vines, fleurs de Lis, and flower buds. These designs typically covered the entire surface of the shoe, and repeat patterns which were frequently seen on 12th century fabrics,[102]Artsikhovskij, A.V. “Odezhda.” Istorija kul’tury drevnej Rusi. Moscow-Leningrad, 1948, pp. 237, 250, illus. 148, 160. 12th-13th century stone carvings,[103]Mongajt, op. cit., p. 310. and 11th century frescos.[104]Grecov, B.D. The Culture of Kiev Russia. Moscow, 1947, p. iii. This affinity in ornamentation speaks to its genuine popularity.

In the 12th century, both plain and openwork soft shoes were also worn in other cities of medieval Rus’. In Belozero, simple shoes and soles with pointed, raised heels were found in a 12th century layer.[105]Dig by L.A. Golubevaja. State Historical Museum, inv. No. 83205. Similar shoes were found in a 12th-13th century layer in Pskov.[106] Dig by G.P. Grozdilov, 1954. Hermitage, inv. No. 163, 369, 380, 712. Shoes with a bent upper, tied at the instep with rawhide laces through side slits, were found in Grodno from a 12th-13th century layer.[107]Voronin, Drevnee Grodno, p. 281. These were all analogous to those from Novgorod.

Ankle boots from this period had detachable bootlegs and heel quarters which were plain or had a slit at the bottom. Their soles were of the usual type – blunt nosed, with a pointed raised heel. Similar heels found in Belozero indicate that they also wore similar shoes there in the 12th century, and possibly ankle boots as well, since similar soles were used for both types of footwear.

Boots of the 12th century had pointed or blunt nosed uppers. The bootlegs of some boots were tied at the ankles with a leather lace, but many also lacked a lacing. Some boots found in Novgorod digs undoubtedly belonged to the “black peoples” [jeb: villagers] of Novgorod. Similar boots were also worn by peasants in the 12th century, judging by a painting in the margins of the Pskov chronicle.[108]Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. I. Moscow, 1953, p. 116.

Boots worn by boyars and princes would have been made from the finest leather, primarily of dyed saffian, and decorated with embroidery or pearls. A fresco in the Church on the Nereditsa (12th century) in Novgorod shows Jaroslav Vladimirovich in yellow boots decorated with pearls.[109]Prokhorov, op. cit., p. 77.[110]jeb: See image JEB6 in the Addenda section for a reproduction of this fresco. In a minature from the 12th century manuscript “Ippolit’s Sermon on the Antichrist,” the prince is wearing red, patterned shoes.[111]Artsikovskij, Odezhda, p. 70. Colored boots were also worn by the princes’ and boyars’ family members. The 12th century author Daniil Zatochnik wrote “I would rather see my own feet in bast shoes in [the Lord’s] house, than in scarlet boots in a boyar’s court.”[112]Pamjatniki drevnerusskoj literatury. Iss. 3. Leningrad, 1932, p. 60.

13th century footwear

Bog shoes were widely worn in the 13th century and distinguished for their variety. Alongside plain bog shoes, which represent the majority, there have also been found smart-looking openwork shoes and composite shoes. Openwork shoes similar to those from Novgorod have also been found from 12th-13th century Grodno[113]Voronin, Drevnee Grodno, p. 61, Illus. 26, item 3. and Pskov.[114]Dig by G.P. Grozdilov, 1954, Hermitage.

In the 13th century, the quantity of soft shoes significantly diminished, compared to the previous time period. The majority of shoes from this time were openwork, decorated in patterns of curls, knotwork, etc. over the entire surface, or only on the upper. These embroidery motifs in leather footwear are analogous to paintings from Novgorod,[115]Russian Museum (Leningrad), Icon of “Nikola” from the Dukhov Monastery in Novgorod. as well as lacework from Staraja Rjazan’.[116]Mongajt, op. cit., p. 315 (drawing). Embroidered shoes have also been found in Grodno[117]Voronin, Drevnee Grodno, p. 62. and Pskov.[118]Dig by G.P. Grozdilov, 1954, Hermitage.

In the 13th century, soft shoes were worn not only in the city, but also in the countryside. Remains of men’s shoes with pointed toes and flat-heeled soles were found in Vjatichi burial mounds near Tushino, Moscow province.[119]Artsikhovskij, A.V. Kurgany vjatichej. 1930, p. 102. The soles had a pointed end, with would be sewn between the two halves of the upper.

13th century ankle boots were in no way different from those of the previous time period. The quantity found in the 13th-century layers was less than that form the 10th-12th centuries.

Boots from this period were the most widely used footwear of Novgorod’s population. As in the previous period, they came in pointed or blunt-nosed uppers, with bootlegs and heels in the normal cut. Some bootlegs had holes or cuts in the upper half designed for threading laces or decorative leather straps.

14th century footwear

Bog shoes in this period were either simple or compound. They are similar to those depicted on the frescos of Novgorod’s 14th-century Skovorodskij Monastery.[120]Jakunina, op. cit., p. 43, illus. 18б.

Ankle boots slowly fell out of use in the 14th century, and are not found at all in layers from the 15th century.

In the 14th century, boots without raised heels continued to exist, as in the previous time period. But, we also see for the first time boots with raised heels, as seen from soles found in an 16th-century layer with a narrow heel and a stacked heel made of iron attached. Simple boots from Novgorod were similar to those from Moscow.[121]“Izuchenie drevnego proizvodstva…,” illus. 5, 6в, 6г, 7, 8.

Alongside the types of 14th century footwear listed above, individual examples of simple and openwork shoes have been found, but these were not characteristic of this period.

Novgorod written sources from the 13th-14th centuries include the words kaligi and plesnitsy related to shoes (for example, “v kaligi i bouty” – “in kaligi and boots”).[122]Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevnerusskogo jazyka po pismennym istochnikam. Vol. I. St. Petersburg, 1893, p. 1182. It is difficult to determine to which type of footwear these words refer.

15th-16th century footwear

Bog shoes are only found in 15th-century layers, and are of extremely simple design.

Boots in the 15th-16th centuries were the most widespread form of footwear amongst the citizens of Novgorod. The majority had pointed, upturned toes. Among the boots of this period, we also find special hunting boots with wide, elongated bootlegs which reached above the knee.

Pointed boots were decorated with stamping on the upper in the form of stamped parallel lines (Illustration 7, item 5), or with hobnails with convex, round heads around the toe and heel.

From this period, boots have also been found with tall, narrow heels, which later were worn not only in Novgorod, but also in Moscow. A pair of green saffian boots from the 16th-17th century (Illustration 7, item 6) in the collection of the Novgorod museum presents the most complete picture of this type of boot.[123]Novgorod Museum, Inv. nos. 7628, 7629. The legs of these boots were double seamed with a lining, 27.5-29.5 cm in height. A dark-brown leather edge is sewn along the upper edge of the leg, forming a meandering pattern combined with parallel lines. In the front, the ends of this edging go downward forming an arrow. The seams joining the leg and heel to the upper are likewise edged with light and dark leather piping and brass wire. The heel quarter is embroidered with brass wire and rows of colored leather (red and yellow). The sole was sewn to the upper with crimson and yellow thread. Its bottom is completely covered in iron hobnails (head diameter 3.5-4 mm) forming a herringbone pattern. The metallic base of the heel was hammered onto a wooden form, covered with leather from the heel quarter, and covered at the bottom with parallel rows of brass spirals. The tall heel, which is slightly pulled to the rear, and the sole (in the arch area), a gap was achieved through which “a sparrow could fly” (Illustration 7, item 6). In medieval Russian folklore, there is a figurative description of a similar pair of boots with tall heels:

"The warrior has boots of green saffian:

See the heels like awls, the sharp-pointed toe,

See a sparrow fly under the heel,

As though to lay an egg near the nose."[124]Andreev, N.P. Russkij folklor. Leningrad, 1938, p. 163.

To conclude this chronological classification of Novgorodian leather footwear based on the collected archeological material from the 10th-16th centuries, we would like to note the following:

- The large quantity of leather footwear found during excavations in Novgorod and belonging to all periods of its existence starting in the 10th century, serves as one indicator of the cultural level of the city’s population.

- Certain types of footwear were characteristic for each time period.

- Differences between the shoes obtained primarily from archaeological digs in the artisans’ districts of the city from the footwear of princes and boyars depicted on monuments of art (icons, frescoes, etc.) provides evidence that there were various categories of shoemakers in Novgorod, serving the needs of different classes of society (artisans, boyars, princes, etc.).

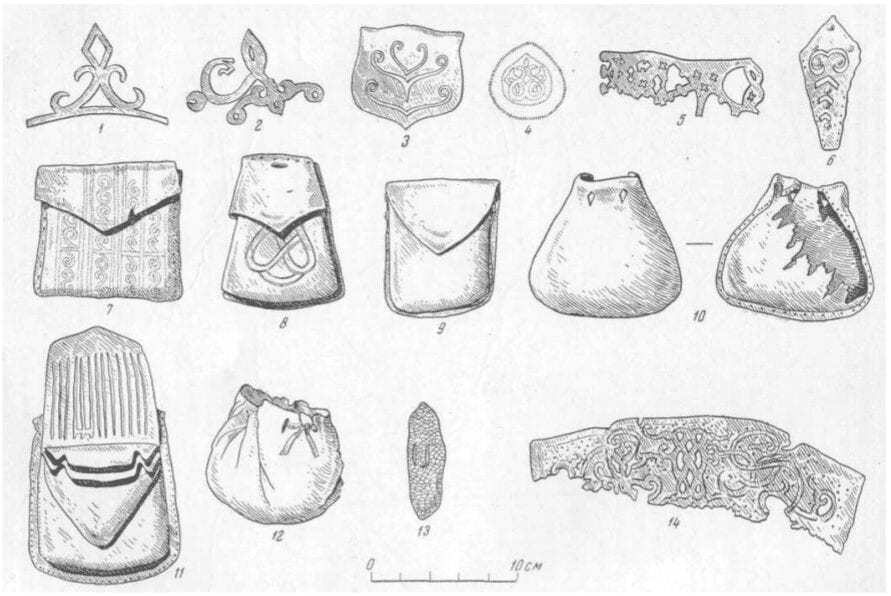

3. Various leather items from Novgorod excavations

An overview of the leatherworking arts of 10th-16th century Novgorod would be incomplete if we did not include a review if we did not review items created by shoemakers that were not related directly to shoes, but were made from the same materials. We are referring to the variety of items made from leather which played a large role in everyday life: balls, knife sheaths, bags, pouches, mittens, belts, etc. Table 4 shows a breakdown of these items by layer and century.[125]This table does not include items found in the 1955 excavations.

Balls (мячи, mjachi)

The use of leather balls in Rus’ first became known only after archaelogical finds in Novgorod.

1 – ball (13-20-1); 2 – ball decorated with silver stripes at the seams (14-18-280); 3 – parts of a ball (5-8-927).

Balls were made from well-tanned leather (to make them waterproof). They were sewn together from 2 circular pieces of various diameters (from 2 to 6-7 cm, or even as large as 11-15 cm) and a rectangular piece with a length equal to the diameter of the round pieces (Illustration 9, item 3). There have been cases noted where the rectangular pieces was made up from multiple pieces. These cut pieces were joined to one another using invisible or hidden seams. First, one of the round pieces would be joined to the rectangle. Then, the second circle was attached, leaving a hole whereby the ball could be tightly packed with wool, moss, or plant fiber (linen, flax, etc.) After the ball was stuffed, the hole was sewn closed.

In order to strengthen the seams between the individual pieces, sometimes narrow straps were sewn between them. These were sometimes decorated with thin silver thread (Illustration 9, item 2).

Balls are found in Novgorod in all layers from the 10th-16th centuries. At first, balls were made by shoe-makers, but later, in the 15th-16th centuries, they were made by specialized ball-maker artisans.[126]Majkov, op. cit., p. 1.

The large number of balls of various sizes found in Novgorod speaks to their wide use in everyday life. Those that were smaller in size were probably used for playing games similar to rounders. Larger balls (15-20 cm in diameter) may have been used for games similar to volleyball or soccer.

It is not known exactly which ball game was referred to by the phrase “to knock into the ball” used in one of the written sources from the 12th century, meaning a technique for conducting battle.[127]Kochin, G.E. Materialy dlja terminologichekogo slovarja drevnej Rossii. Moscow-Leningrad, 1937, p. 199.

Leather balls similar to the ones found in Novgorod have also been found in Pskov.[128]Dig by G.P. Grozdilov, 1954. Hermitage.

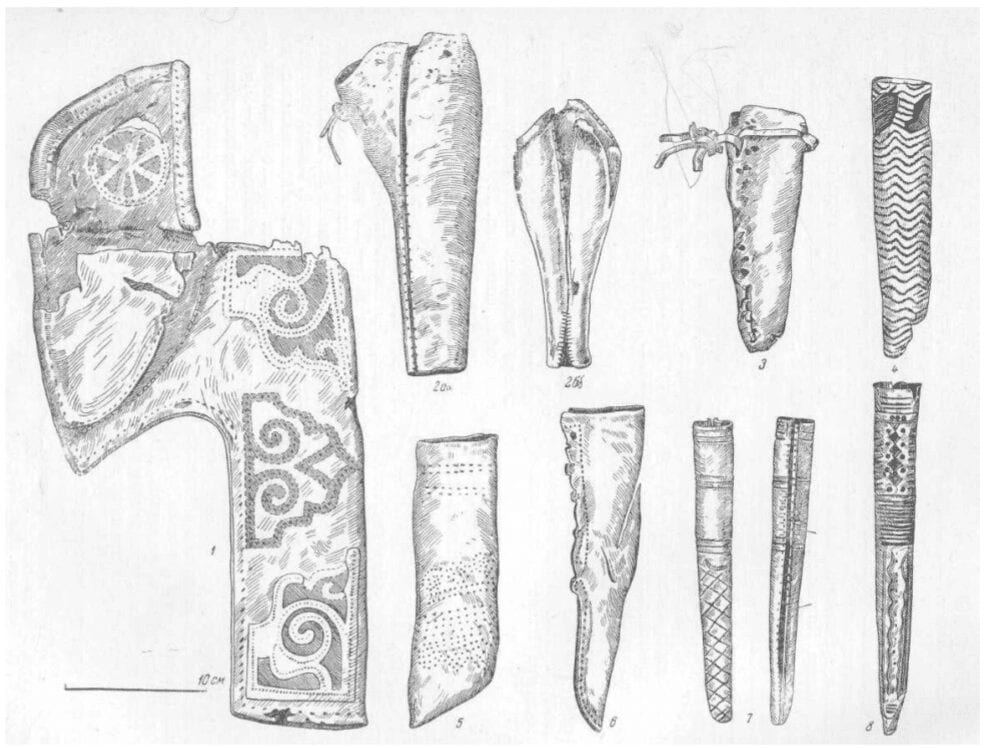

Knife Sheaths (ножны, nozhny)