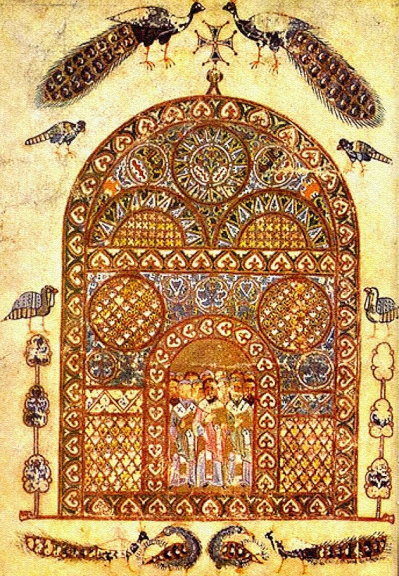

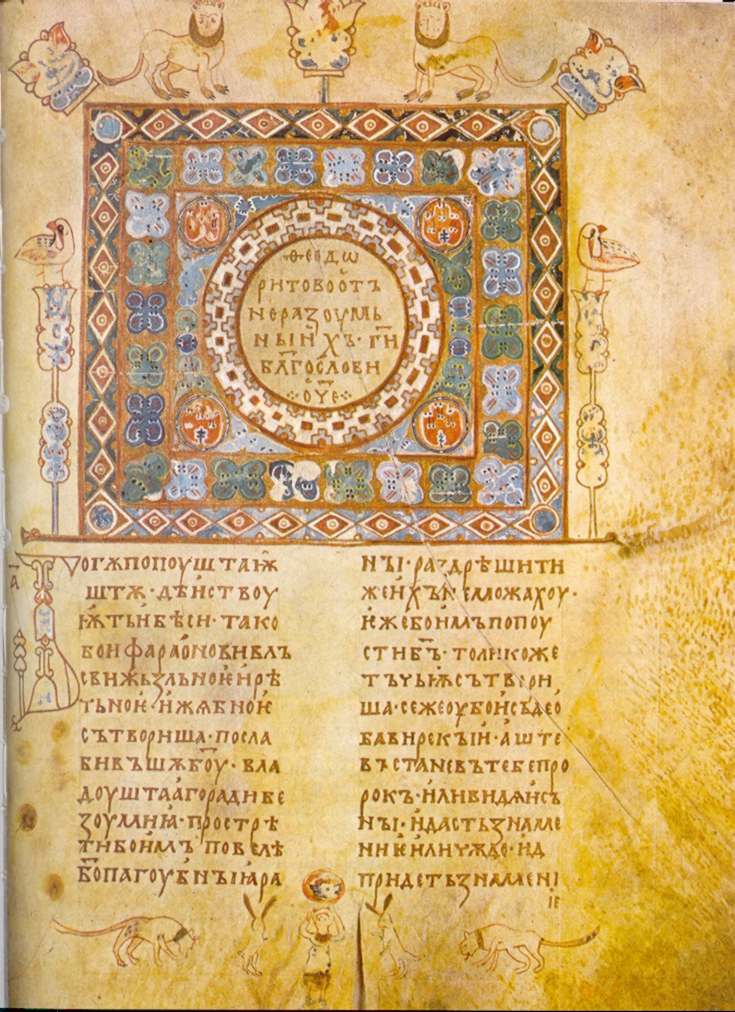

Schavinskij’s chaper on medieval Russian ink was so interesting, I decided to read on, and just finished his chapter on medieval Russian paints. He goes into great depth on the various kinds of red, green, and blue paints that were used in Russia from medieval times up through the 18th century. Black (which was usually “painted” using ink), white (almost always painted using white lead), and yellow (which seems to have been typically orpiment, massicot, or shishgel’, a yellow pigment made from buckthorn berries) are for some reason not described in depth, but are discussed in passing in this chapter. Learn about the dangers of adding garlic to cinnabar! What does minium not love? How did Russians collect cochineal? How do you make verdigris without grapes for vinegar? Where did the Russian word for indigo come from? What exactly is “dove blue” made of? Read on and find out!

Medieval Russian Paints

A translation of Щавинский В. А. «Древние русские краски.» Очерки по истории техники живописи и технологии красок в древней Руси. М., Л., 1935. с. 93-129. / Schavinskij, V.A. “Drevnie russkie kraski.” Ocherki po istorii tekhniki zhivopisi i tekhnologii krasok v drevnej Rusi. Moscow-Leningrad, 1935, pp. 93-129. [Notes on the History of Painting Techniques and Paint Technology in Medieval Rus’.]

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.icon-art.info/bibliogr_item.php?id=10230. ]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

Cinnabar (Киноварь)

As with the majority of terms used to indicate red mercury sulfide (cenobrium, cinabrio, Zinnober, et. al.), the Russian word kinovar’ (Rus. киноварь) is very similar to its Greek term: κιννάβαρι. We have no data whether or not this paint[1]jeb: note that paint made from cinnabar also goes by the term “vermillion.” Russian doesn’t make a distinction between the two. I’ve consistently translated киноварь as cinnabar, as a result. was known to Kievans and Novgorodians prior to the start of intensified Greek-Byzantine influences. Beginning with the start of this era, it was used with general and widespread prominence.[2]The Romans learned of cinnabar only during Scipio’s Spanish campaign (around 200 BCE). Aside from Spanish cinnabar, the ancients were also familiar with cinnabar from Colchis. We find it everywhere in the earliest works of our writing, from the 11th-16th centuries, inclusive, and thanks to its uninterrupted continuity in terms of book writing, on the one hand, and it appears, and the abundance of material itself on the other, the concept of cinnabar in its original meaning has been firmly retained to modern day. This is all the more interesting because everywhere except in Russia, with regards to cinnabar, there is continual confusion of this concept at various times.[3]Whereas in Russian literature we nowhere find signs of cinnabar being confused with any other similar paint, in Western Europe, such confusions are encountered relatively frequently, beginning it seems from the moment of its appearance among the Romans after Scipio’s Spanish campaign, and running up until later times. For example, Pliny and Vetruvius called it minium or red lead (Rus. сурик, surik, “lead tetroxide”), the author of the Leiden Papyrus X (3rd century) along with Dioscorides confused it with sinopia (red earth), with orpiment (Rus. сандрик, sandrik, “arsenic trisulfide”) and minium, Heraclius confused it with carmine, and it seems, with some kind of vegetable-based paint called glades and glaciens, Theophilus confused it with sinopia, de Mayern confused it with orpiment, and so forth. In addition to Spanish deposits, Western Europe obtained its cinnabar from the Causasus (Colchis). It can be difficult to say which of two essentially chemically-identical varieties of cinnabar, natural or artificial, was originally used in Russia.

In the USSR, the former of these can be found in several locations. The best known, the Nikitovskoe Field located near the Bakhmut district of the Dniepropetrovsk region was important in former times not only for domestic, but also for foreign trade. In 1736, J.M. Croekern wrote that German pharmacists sold natural cinnabar originating in mines in Ukraine, Hungary, and Semigradiya, as well as Germany.[4]This does not rule out the possibility that that by “Ukraine,” the German writer meant the Krain (jeb: Carniola, a region in modern day Slovenia.) where cinnabar was also mined. According to the testimony of their former owner Auerbach, who assembled a significant collection of medieval mining tools and made many interesting observations, the Nikitovskoe cinnabar mines had already developed in ancient times, possibly even in prehistory. In a study of the Olbia excavations by the Institute of Historical Paint and Cosmetics Technology, mineral cinnabar was found in significant quantities.

The method for preparing artificial cinnabar was thoroughly covered in the oldest of our available sources, a sbornik manuscript from the middle of the 15th century:[5]Manuscript I.

Указ како творити киноварь. О киноваре. Возми ртутя литру едину изгисай сунпора литры две, сотри же обое купно потом обреть сосуд стеклян дебел якож викию имают мирожи продающiе врачебная. И потом обряще как от ногож творят златарие горнила вних же растворяют злато и чесаница дробные и расчеши их надробно и смеси их с пометами ослими и с каком егда смесиши трое добре, возми стекло и помаж е от надвара все когда просохнет то помажи до 6-ти крат, когда просохнет добре вложи внутрь ртуть и сунпор якож имаши сотренно, и шарие на огни да горит дондеже видеши исходящ дым черлен и тогда творится киноварь.

How to create cinnabar. About cinnabar. Take a single litra[6]jeb: A Byzantine measure of weight, approx. 327.6 gr. of mercury, melt (?) two litras of sulfur[7]jeb: сунпор, sunpor, “sulfur.”, and mix (?) them both together,[8]jeb: купьно meaning вместе, “together”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkago jazyka po pis’mennym’ pamjatnikam’. Vol. I. St. Petersburg, 1893, p. 1373. then find a stout[9]jeb: дебелыи meaning толстый, “stout”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. I, p. 649. glass vessel similar to those medicinal vessels[10]jeb: викия meaning сосудь, “vessel”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. I, p. 257. sold along the Mirozh River. Then having found a small[11]jeb: дробьныи meaning мелкий, “small”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., p. 724. rake like those used at a goldsmith’s hearth when they melt gold from nuggets,[12]jeb: ногуть = нохотъ meaning горох, “peas”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkago jazyka po pis’mennym’ pamjatnikam’. Vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 462. mix them well, and then mix in donkey dung, and mix the three together well, then take the glass [vessel] and coat its outer surface[13]jeb: от надвара, “from the outside”. and let it dry, and do this up to 6 times, and when it has dried well, put the mixed mercury and sulfur within it, and having closed (?) it, then heat the vessel over a flame until you see crimson smoke emerge, and then the cinnabar is created.

This recipe is noteworthy not only in the early date of the list which included it, but also in the directness of how it presents the process itself. The abundance of untranslated Greek words and and South Slavic elements speaks to its very close connection to the South. Nothing more definite, however, can be said about it.[14]Simoni, P. Ob’jasnitel’nye primechanija k tekstam, izdannym v PDPI, CLXI, p. 3 and following. Among our remaining recipes, this one stands alone and obviously was not influenced by anything. This can be explained in that the Russians, who possessed natural cinnabar, did not need a method for manufacturing it artificially.[15]In a Trade Book compiled by Russian merchants in 1575-1610, in a list of imported goods, we find: “cinnabar sells for 9 altyn a pound, and if it is expensive, for 2 rubles.” Sakharov, I. “Torgovaja kniga.” Zap. Otd. russk. i slav. arkh. Arkh. obsch. vol. I., St. Petersburg, 1851, p. 125. In the second half of the 17th century, cinnabar imported through Arkhangel’sk was purchased by order of the Armory for iconographic work. it was also for sale in Moscow. Uspenskij, A. Tsarsk. ikon., vol. I, p. 314 and following. Of the earliest foreign recipes, this one is most similar to that of Theophilus, which also prescribes mixing mercury with sulfur in a 1:2 ratio, and to heat the solution in a closed glass vessel coated with clay,[16]Theophilus, CXLI. although it is not a direct translation – for example, the step at the end of the reaction (“until you see crimson smoke emerge”) does not really match the Latin “cum sonus cessaverit” (“until the noise ceases”). This similarity can be explained by the common chemical methods used during the Middle Ages, which included the heating of glass vessels which had been coated in a mixture of clay and manure. The recipe presented in a Herminia[17]jeb: A type of manuscript dedicated to the technology of icon painting; from the Greek Ἑρμηνεία, “explanation.” is, it seems, later, and in many ways differs from this one (for example, it uses a 4:1 ratio of mercury to sulfur).[18]Erm., 43.

Studying the places where signs of uncrushed raw material may have survived, we come to the conclusion that this cinnabar was of mineral origin. This is how the method for grinding it is described in the most reliable of our sources, a very detailed recipe by the Siysky master artisan:[19]Manuscript XXIV.

Ручник и плита измыть чисто и взять киноварь по надобью и ручником терти без воды на плите грязно поколь незнать будет звездок и опахивать чиненым перышком или деревянным ножичком скраев во едино место, чтоб едино равенством все терлось и задать свежей воды в киноварь малую часть, чтоб неожидить и паки с водою терети[20]The direction that cinnabar must be rubbed with water (“dry, it will burn”) is also specified in another recurring entry. Manuscripts XLVIII, XXVII. и довольно и ножичком скраев на середину оскребать, чтовы все в равенстве утёрлось и что мельче употребишь то он цветен и прибылен бывает, а буде крупно утрешь, черноват не прибылен будет в творке.

Wash clean a small pestle[21]jeb: ручица meaning ветвь, “stick”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkago jazyka po pis’mennym’ pamjatnikam’. Vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1912, p. 200. and a brick[22]jeb: плита meaning кирпичь, камень, “brick, stone”; Sreznevsky, op. cit., vol. II, p. 965., and take as much cinnabar as you need, and rub it to dust without water using the pestle against the brick until there are no longer any sparks[23]jeb: literally, “little stars.” and brush[24]jeb: опахати meaning обмахивать, “to fan, brush”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, p. 679. the piles[25]jeb: скра meaning груда, “pile”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 390. into a single pile using a clean feather or a wooden knife, such that everything is evenly ground, and add a small portion of fresh water to the cinnabar, and without waiting, while it is wet, grind it thoroughly, and use a knife to scrape it back to the center, such that everything is ground evenly, and the more fine it is when you use it, the more colorful and gainful it will be, but if it is coarse, it will be blackish and unsuccessful in your work.

A second surviving recipe recommends the same signs when grinding: to grind the cinnabar until the “sparks” disappear.[26]Manuscript XVIII (38). In the printed text, it says: “покамест не увидишь в киноварью искр” – “until you see sparks in the cinnabar”. This is apparently a mistake by the copyist or publisher. Finally, we find a third recipe in a list of paints, where it says: “киноварь веницейская цветом искры светлеются у ней” – “Venetian cinnabar glows from the light of the sparks.”[27]Manuscript XLII. These sparks or “stars” seen in commercial cinnabar as it was crushed, due to deposits of pyrite or other sulfide ores which accompanied the cinnabar, were absent in artificially prepared cinnabar.[28]Cinnabar from Nikitovskoe was typically accompanied by antimony or antimony ores, which also have a metallic luster.

In the 17th century, along with indigo, (Med. Rus. крутик, krutik)[29]jeb: see Schavinskij, V.A. Ocherki po istorii tekhniki zhivopisi i tekhnologii krasok v drevnej Rusi. Moscow-Leningrad, 1935, p. 37 (footnote 47): “крутик или индиго”/”krutik, or indigo.” cinnabar was one of the cheaper paints; it cost just two dengas per zolotnik,[30]jeb: a denga was a Russian coin used from the 14th-17th centuries, valued at 1/2 kopek. A zolotnik was a measure of weight, equal to a little more than 4 grams. This comes out to about 3.5 kopeks an ounce.[31]Manuscript XXV. According to a royal painter writing in 1667, cinnabar cost nearly the same amount. Uspenskij, op cit., vol. 1, p. 311. Sometimes, however, prices were significantly higher. and was so widely used that sometimes it was sold even more cheaply, but not always, it seems, if minium was on hand: “желть да киноварь то станет сурик” – “yellow and cinnabar can be used as minium.” The same also was true for cochineal (Rus. бакан, bakan): “вохра да киноварь то станет бакан” – “ochre and cinnabar can be used as cochineal,” or even in the appropriate mixture, light ochre.[32]Manuscripts XXXVII, XXVII, XLVI, XXXVI, XLIII. There even exist directions for the opposite case, of making cinnabar from minium along with two other substances, apparently with the goal of reducing costs:

Указ какой киноварь составити. Возми сурику выть, да скапидару тож, да селитры тож по мере и все положи в одно место и смочи, покамест она высохнет, а держи в тепле и ты увидишь, что будет добро.[33]Manuscripts XXXVIII, XLII.

On the making of cinnabar. Take one part[34]jeb: Med. Rus. выть, vyt’, “a share or unit.” minium, and also one of turpentine,[35]jeb: скапидар > скипидар, skipidar, “turpentine.” and also the same amount of saltpetre, and place them all in one location, and moisten it, then when it has dried, store it in a warm spot, and you will see that it will be good.

Cinnabar was a beloved paint in Russia and was used pretty much everywhere. In books, it played the second most important role after cochineal. Judging by our manuscripts, starting from the earliest times, our cinnabar, which may not have always achieved that same amazing brightness which is observed in the best Western European manuscripts, nevertheless almost always had a quite pure tone. The change from cinnabar to plant-based red paints which quickly faded serves paleographers studying Slavic manuscripts as one of the signs that a manuscript is of South Slavic, rather than Russian, origin.

The directions for creating ground cinnabar for writing, which was very widely used, exists mainly in one redaction from manuscripts from the 17th-early 18th centuries in many repetitions.[36]Manuscripts XVI, XVII, XXXVI, XXXVII, XXXVIII, XXVII, XLIII. The original text was doubtless much older, as can be seen from the large number of later versions. We show here the most complete text, from an 18th century manuscript:[37]Manuscript XVII.

О киноварном растворении. В маленькiй сосудец всыпати киноварь и положити вода мало и мешати перстом прежде не густе и по малу приливать вода дондеже растворится по чину и сухого не будет и поставить сосудец, он мал час дондеже устоится и сливати вода с киноварью во ин сосудец, а киноварь тотчас же положити квасцов толченых мерно по сосуду смотря, понеже велия пользы киноварю от квасцов ставится киноварь красен и личен и с пера бежит. А чеснок неции толкут не соля и кладут в киноварь, тем гнездо киноварное портят, якож патока класти в чернило порча есть гнездо, сице и чеснок класть в киноварь велия спона гнезду лоск злой и смрад и гнездо гниет от чесноку и в тетратях красные строки слипаются и письмо помрачается, отнюдь не потребно есть чеснок класть в киноварь. Яблоко же кислое, а не сладкое, измяв гораздо жми из него сырость в киноварь, зело бы сие добро и подобно квасцам в пользу гнезду, жми же аще имеша румянец в киноварь, вельми бо красен киноварь становится от румянцу.[38]A special method for the preparation of cinnabar is presented by a late 17th century muralist. “Киноварь утерть на плите с водою, да и высушить, да положить в медное судно и налить в него доброго вина и горить. По тех мест как само утихнет и высушить и тако писать.” – “Grind the cinnabar with water on a brick, then dry it, and place it in a copper vessel and pour good wine into it, and then heat it. In that place, let it settle and dry, and then write with it.

On the dilution of cinnabar. Pour the cinnabar into a small vessel and add a little water and mix it with your finger before it thickens, and little by little add water until it dissolves well and is not dry, and set the vessel aside, and let it sit for an hour until it settles, and pour the water from the cinnabar into another vessel, and immediately add a measure of crushed alum to the cinnabar while watching the vessel, until the cinnabar benefits from the alum and becomes red cinnabar [ink] and direct(?) and flows from the quill. If any garlic is pounded without salt and added to the cinnabar, then the “nest” will spoil, or if you place its juice into the ink the “nest” will spoil, for adding garlic to the cinnabar will be a great hinderance to the nest, and [the ink] will have an evil gloss and stench, and the nest will rot from the garlic, and the red lines will stick together in your book,[39]jeb: тетрать > тетрадь, “notebook, quarto” and the letters will darken, as there is no need whatsoever to add garlic to cinnabar. Having pressed the juice from an apple that is sour, and not sweet, add it to the cinnabar, and it will be good and useful to the “nest” similar to alum, or you can also add pressed crimson[40]jeb: Rus. румянец, rumjanets, “blush, crimson, rose” to the cinnabar, and the cinnabar will become quite red from the roses.

The note about the dangers of garlic, which is not repeated in other manuscripts, appears to be an individual addition.[41]The author of one Typikon [jeb: a type of book outlining the the Byzantine Rite and hymns in the Divine Liturgy.] recommends adding garlic together with egg white. Manuscript XXXVIII.

The observation about the use of alum, which is repeated everywhere, is extremely interesting in that it shows the link with sources from deep antiquity. In a Greek Alexandria papyrus from the 3rd century (the Leiden Papyrus X), a fragment of a recipe for the dilution of cinnabar via the addition of alum and white vinegar is preserved.[42]This is also in the Padua Manuscript, 17th century, published by Merrifield, Original Treatises, Longon, 1849. The latter, as often occurs in Russian directions, was exchanged for a more easily accessible acid – “the juice of a sour apple.” Crimson, or “dressing blush,”[43]jeb: “румянец платяной,” “румянец платной,” later “румянец платчатый”.[44]See the section on Rumyanets. (This article is missing in Schanvinsky’s manuscript – M.F.) used as a woman’s toiletry item, was also used by painters, along with cinnabar, to create a light cochineal.

Aside from the aforementioned, widely used redaction, in a 16th century manuscript[45]Manuscript III. there is preserved one short, somewhat corrupted redaction, also repeated by the author of one typicon:[46]Manuscript XXXVIII.

Прежде размочи в воде камедь, еже есть вишневый клей белой, чистой и лей в киноварь, то и прияте и бегучее и мухи не ясть, да туда же положь квасцов и будет урядно и красно.

First soak in water the gum,[47]jeb: камедь, kamed’, “tree resin, gum” that is, cherry glue which is white and clean, and add it to the cinnabar, and when it is good and flows and there are no flies, then add alum to it, and it will be nice and red.

A notation of apparently personal observations by a Northern Russian artisan from the end of that century or the beginning of the next[48]Manuscript VIII. indicates one should rub the cinnabar with the gum using the palm of your hand and with water, or using gum and kvass.

As a rule, for writing, cinnabar was dissolved in gum,[49]According to the Athonite Herminias, cinnabar was mixed with tree gum and sugar. although an exception is an entry in the Ikonopisniy podlinnik from the 17th-18th centuries,[50]Manuscript XXXV. which discusses using egg white, or even the whites “of an owl’s nest” mixed with “duck’s milk”.[51]In a second recipe, the author of the Typikon writes about cinnabar mixed with egg white and “poppy milk.” Manuscript XXXVIII. This artist indicates that “it is good to keep in your cinnabar well a Greek sponge,” and another writes, “If you have no sponge for your cinnabar nest, sew a little pillow from cloth, having sewn the ends tucked in, and put that into your cinnabar well.”[52]Manuscript VIII.

Iconographers also widely used cinnabar. It was used in Russia, as always and almost everywhere, together with white lead and ochre as part of flesh color – sankir’[53]jeb: санкирь, a greenish-brown tone used in iconography for painting flesh., the “membranes” of Latin artists, or in paints which were used to “darken or lighten” a given base tone.[54]A Dutch master from the late 16th-early 17th centuries writes that cinnabar (along with white lead) gives flesh blush and warmth: “maer vermilioen doet al vleeschigher Glocyen.” Pure bleached cinnabar, or cinnabar mixed with other paints, was used to paint the upper and lower vestments of many saints. It was also used in all manner of mixed tones for various needs and combinations; cinnabar was only not used when painting “fields of light.”[55]Manuscript XLIX.

Russian artists also used cinnabar for mural painting, although with certain limitations. For fresco painting in its pure, perfect form buon fresco, where this technique has been used, where the paint binder was solely caustic lime, they avoided using cinnabar; likewise, Cennino Cennini and Raphael Borghini (14th-15th centuries) left it out of their lists of fresco paints. There is also the opinion that for mural painting in general, only natural cinnabar was useful.[56]Alb. Ilg, footnote to a translation of Cennino Cennini, p. 147. Out of two surviving Russian mentions, the first by a Bishop Nektarios, says: “а киноварем писать внутрь церкви, а извне не писать, потому что почернеет” – “but paint with cinnabar only inside the church, and do not paint with it outside, because it will turn black.”[57]Manuscript XXXVIII. The second comes from a manuscript from the first half of the 17th century: “а вне церкви писать за киноварью место вохрою горелою” – “outside the church, instead of cinnabar, paint using burnt ochre.”[58]Manuscript XI. Both of these brief mentions are in full agreement with the decrees of the Athonite Herminias:

О киновари надобно знать тебе, что если расписываешь наружную часть храма на том месте, где дует ветер, то не клади ее, потому что она почернеет, а замены светлокорчневою краскою. Если же расписываешь внутри храма, то прибавь к киноварь немного стенных белил и константинопольской охры, и она не почернеет.[59]Herminias, #66, translated by Bishop Porfiriy.

You must know about cinnabar that if you are painting an outer part of the church, in a place where the wind blows, then do not add it, because it will turn black, but rather replace it with light-brown paint. And if you are painting inside the church, then add to the cinnabar a little whitewash and Constantinople ochre, and it will not turn black.

A second limitation was that cinnabar (as well as minium, sometimes) was prescribed to be made using “wheat glue”, that is, a decoction of wheat grains, rather than pure water as was used with other paints with the exception of azure (Rus. лазорь, lazor’).[60]Manuscripts VI, XIII, VII, XXVI. In the Herminias, this precaution is mentioned only with regards to azure.

For art painting work, oil-based cinnabar was used rarely, and was instead replaced with the cheaper minium, which when combined with linseed oil created a faster drying paint. In bookbinding, cinnabar was used more frequently with gum to paint the edges of book pages.[61]Manuscript XXVIII.

The chemical properties of cinnabar, and its ability to unite with many heavy metals to create black sulfurous compounds was, it seems, notorious, as seen in the directions when grinding cinnabar to scrape it from the edges of the grindstone using a wooden, rather than iron, knife.[62]Manuscript XXIV. In spite of this, the mixing of cinnabar with white lead and even with copper-based green pigments, which modern artists so carefully avoid, was practiced in Russia typically by all,[63]Manuscripts VII, XXX, XXXIII, et.al. as well as in other painting schools. The blackening of the paints was prevented here through their binding agents, the insulating abilities of which is not difficult to demonstrate through experience.[64]Test samples created with a mixture of cinnabar with white lead in oil in various ratios did not change their color over the course of several years, similar to comparison samples created using white zinc (the author’s finding can only be explained by the insulating effects of oil. All artist’s guides caution against this combination. – M.F.)

Along with minium, cinnabar was also used in complex compositions of Greek poliment[65]jeb: aka bole, an adhesive reddish or brownish pigment used under gilding to improve the adherence and color tone of the gold leaf. under gold.[66]Herm., #12. An interesting observation is noted by a Russian artist monk from the late 17th century, who compiled quite detailed notes based on personal experience and that of other artists he knew:

А с суриком киноварь под золото не пригожь и золото перхнет прочь с того киноварью и ты об том накрепко стерегись.[67]Manuscript XXXIII.

But cinnabar mixed with minium is not suitable for gold, and the gold will peel away from that cinnabar, and you should be very wary of that.

This appears to be talking about Russian modifications to an ancient method, which Theophilus was aware of, for gilding in books. Minium and cinnabar in a 2:3 ratio, mixed with egg white, served as an underlay for gold foil, which would would stick to that glue. This Russian scribe first “improved” the “large words” on the page by brushing on a mixture of cinnabar and ochre, then applied the gold “на подпуск” – “to this hook”, that is, to this liquid, which caused the gold to adhere to the page. This liquid, the glue which Theophilus calls glutina, and that which the Russian artists called “sheepskin glue,” appear to have all been the same substance. The latter knew that “старые писцы киноварь под золото за клею мест (творили) в масле яичном” – “the scribes of old placed (used) cinnabar under gold using egg oil,”[68]Manuscript XXXIII. that is, egg whites, which were a preferred binder. It is possible that it was precisely the use of this new binder which conditioned the interaction between the cinnabar and minium, leading to the formation of lead sulfide and causing the gold to flake off the page.

Minium, or Red Lead (Сурик)

Surik (Rus. сурик, “minium, red lead”), the Great Russian word for red oxides and peroxides of lead, is not related to the accepted names in Western European languages for these well-known compounds.[69]Today, there exists a cheaper form of paint called iron minium, achieved by heading iron compounds, and having nothing in common with lead-based minium. Here, it seems, we must turn to its Greek origin.

In early times, minium was achieved by burning white lead. Pliny reveals the history of the accidental discovery of minium, a fire in Piraeus at a time when there was a load of white lead there packed in a box.[70]Pliny, XXXV, 6, 20. Descriptions of how to create red lead can be found in writings by Vitruvius, Heraclius, and Theophilus.[71]Heraclius, III, XXXIV; Theophilus, XLIV. This method consists of heating finely ground white lead over a fire, carefully stirring it until it achieves the desired redness. Among Russian authors, this description is encountered rarely. A manuscript attributed to a Bishop Nektarios provides the following:

Указ какой сурик делать. Возми белил и положи в череп железной сосуд и постави на жар, и как загорят белила, станут красны, то и сурик.[72]Manuscript XXXVIII.

How to create minium. Take white lead and place it into a skull-shaped iron vessel, and place it upon the fire, and the white lead will turn tan, then will become red, and then it will be minium.

We do not see mentioned here, first of all, that the white lead must be previously finely ground, nor secondly that it must be stirred while it is being roasted. Both are quite important for the calcification process needed to create red lead. A second mention is related not to the production of minium itself, but with the roasting of white lead as a preparatory step for the boiling of linseed oil:[73]jeb: Rus. олифа, boiled linseed oil, used in icon painting as a protective final topcoat varnish over the tempera paint.

И в кадильницу положа белил ожги на угол, чтобы были красноваты, аки сурик.

And place white lead in a censer and heat it over a fire until it turns red like minium.

This shows the unknown author’s unfamiliarity with the technical principle. In the absence of other instructions, we must suppose that Russian artists did not know how to prepare minium, and must have purchased it from other specialists, either domestically or possibly as a foreign trade. The latter is not supported by its inexpensive nature, which allowed it to be used widely for painting and other kinds of technical needs. In the second half of the 18th century, as can be seen from the Armory Palace’s expense accounts, minium prepared in the town of Kashin was quite famous in Moscow.[74]Manuscript VIII. In 1667, a pound of Kashin minium cost 6 altyn 4 dengas (jeb: 18.67 kopeks).[75]Kashin minium is mentioned in Uspenskij, A. Tsarsk. ikon., vol. I, pp. 262, 313; Vol. III, p. 379 and following. In 1770, a supply of 11 large poods (jeb: 180 kg) in 26 bladders were purchased for the Armory Palace, vol. III, p. 230. In the very beginning of the 18th century, in the North it cost 10 dengas, while in the South (in Glukhov) in 1727, 3 pounds of “miniya” (Ukrainian red lead) cost 36 kopeks.[76]White lead cost 6 dengas and ochre cost 4-6 dengas. Manuscript XXXV.

The main use of minium was as base coats and for painting all kinds of crafts. The Siysky craftsman wrote:

Сурик с маслом льняным стирать зело удобно и красен будет, и потом мало задать олифы крепкая и скорая к ставки сурик с маслом. И по железу писать и ко всему удобен, красить и подкрашивать скрынку и шкатулку и к судовой поделке.[77]Journal of N. Khanenko, p. 7.

Minium mixed with linseed oil makes a very fine and red wash, and then add a little bit of linseed oil to make the minium and oil dry quickly and strong. And it will be convenient to paint on iron or on anything, to paint and decorate boxes and chests, and for marine goods.

Another artist who preferred the egg white technique from a slightly later time wrote:

Буде яйце с краскою и суриком смешать и писать и сверх олифою покрыть и будет крепко; а буде сурик с яйцем писать и потом олифить.[78]Manuscript XXIV.

Take an egg and mix it with minium, and paint with it, and cover it with linseed oil, then it will be strong; and if you paint with minium and egg, then cover it with linseed oil.

Minium was also used in bookbinding. Red lead was quite often used in various “compounds” and “potions” used “under gold” to “make it scarlet,” as an ingredient in poliment or “goldfarb.”[79]Manuscript XLII[80]jeb: Rus. гульфарба, a yellowish or reddish paint or varnish that was applied to wood, metal, glass, etc. items before gilding. When gold foil was being applied to white levkas, paper, or wood, for example when “у братинок венцы подписывали” – “the crowns of loving cups[81]jeb: Rus. братина, bratina, a spherical vessel used for drinking wine, mead, or beer. were painted” then they were first painted with an undercoat of “equal parts levkas and red lead,”[82]Manuscript XXVIII. in order to give the gold a reddish tone. A favorite method of painting on red gesso in 18th century Western Europe was also adopted by Russian painters, as seen in an early 19th century recipe for priming canvas, where the gesso was tinted in bulk with red lead and lime coal.

In lists of paints that are suitable for murals and frescoes written by the Western European masters, we do not find red lead. In one “Directions for mural painting” (“Устав стенному письму”), we do find an indication that red lead was used, although not without the precaution that, as with azure and cinnabar, it should be made using “wheat glue.” The directions’ conclusion mentions “А киноварь на том же твори, как следует раваривать пшеницу для письма лазорью” – “And make cinnabar the same way, just as you should boil wheat when for writing with azure.” This short precaution is repeated in several variants, while in others, the mention of red lead is omitted.

Red lead was generally used for both paintings and illuminations. It is frequently encountered in lists of paints and in directions of paints “which can be blended together:”

Когда оранжевый оттенок его надо было усилить, то прибавляли желтой, и получали “золотую краску,” кирпично-красные “лилей цветы” давал охра с суриком, когда же не хватало самого сурика, то ему подражали, пребавляя к холодной по тону киновари немного желти.[83]Manuscripts XXXVIII, XLVI.[84]Manuscripts XXXVI, XLVIII, XXXVIII.[85]Manuscripts XLVI, XVIII, XXXVII.[86]Manuscript XLVII.[87]Manuscripts VII, XIII.[88]Manuscripts XLVII, XLVI, et.al.[89]Manuscripts XLVI, XXXVI, XXXVII.[90]Manuscripts XXIII, XLIX.[91]Manuscripts XV, XLVI, XXVII, et.al. Manuscript XXXVIII includes a method, distorted by the scribe to the point of incomprehensibility, of creating cinnabar from red lead by mixing it with turpentine and saltpetre.

When an orange shade needed to be strengthened, then they added yellow to create “gold paint,” ochre and red lead gave the brick-red of “lily flowers,” and when there was not enough red lead, then it was imitated by adding a little yellow to the cold tone of cinnabar.

Although it is customary to state that book miniatures got their name from minium (that is, red lead), due to an amazing confusion of concepts which ruled in medieval and classical antiquity in the area of red pigments, it is difficult to be absolutely sure that this type of art’s name is tied to red lead or at least only to red lead. The earliest mention, it seems, concerning the use of red lead (using egg as a binder) for illumination is found in a fragment of an 11th century manuscript, by the author known as Anonymus bernensis.[92]Quellenschriften fuer Kunstgeschischte. VII. Vienna, 1874, p. 384.

In Russia, knowledge of the chemical properties of red lead was shown in their ability to deacidify it, resulting in the yellow pigment massicot,[93]jeb: Rus. блягиль, bljagil’, “lead oxide, massicot”, from Ger. bleigelb. as well as their familiarity with its instability in the presence of acids: “а сурику в кислом не чем не творить – не любит” – “but do not mix red lead with any kind of acid – it doesn’t love it.”[94]Manuscripts XLVIII, XXVII.

Red and white lead were particularly important as lead compounds used in the preparation of various kinds of linseed oil varnish.[95]Manuscripts XXVII, XLIII. They provided to this process not only linoleates which accelerated the drying of the linseed oil, but also acted favorably in the same direction with their oxidizing properties.[96]Manuscripts XV, XXIV, XXXVI, et.al. As a result, it was especially popular for use where fast-drying varnish was required for winter work,[97]Manuscript VIII. as well as for a thick, “favorable”[98]jeb: Med Rus. покосьныи, meaning благоприятный, “favorable”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, p. 1114. varnish (in the form of heated white lead)[99]See the chapter on Linseed Oil Varnish. used when gilding to cover a surface which was not fully dry “to the touch.” This kind of varnish, sometimes colored with more red lead or with ochre, was used when gilding mural images on dry levkas, especially “to gild crowns.”[100]Manuscript XXIII, also in the Athonite Herminias, chapter 69.

Carmine (Черлень)

The word cherlen’ (Rus. черлень, “cochineal, carmine”) is one of the oldest Russian words for the color red. The Lay of Igor’s Campaign tells us:

Русичи великая поля чрлеными щиты перегородища. […]

Чрлен стяг, бела хорюговь, чрвлена чолка, сребрено оружие храброму Святославичу.

The Rus with their crimson shields have blocked the great field […]

Carmine banner, white gonfalon, crimson fringe, silver weapon, To the brave son of Svyatoslav!

Folk memory has long preserved the correct representation of the origin of this word cherlen’. The monk Pamva Berynda[101]jeb: 1550?-1632, Russian lexicographer, poet and engraver. defined it as “кармазиновую фарбу с червцю” – “a carmine dye made from cochineal.”[102]Leksikon slovenorosskij, sostavlennyj vsechestnym ottsom Kir. Pamvoju Beryndoju. Printed in Kiev, 1627.

Pallas collected detailed information about the cochineal scale insect, which has long provided material for dyes but is now forgotten, during his travels through Russia (1768-1774): “From mid-June to mid-July[103]This was the medieval name for the modern month of July. In Polish the word czerwiec means June, as does the word červen in Czech and Slovak., women and children routinely go out before the harvest to gather cochineal (Coccus polonicus). They look for this insect in dry, narrow places, especially near the base of strawberry plants, which they call kubanka, or in the sparse clumps of a grass called Petentilla reptens (jeb: sic).[104]jeb: European cinquefoil. It is said that in Little Russia they collect it near a third type of Viscaria plant, which does not grow near Kinel, but which according to the speech of the local inhabitants appears to be none other than St. John’s wort (Hypericum portoratum) (jeb: sic). They cut this grass with a knife and collect into a vessel the blue vesicles located on the upper part of the plant, of which there may be from 10 to 12 on a single plant, and within which the dye insects are located. These vesicles, depending on the weather, come to ripeness earlier or later in the month of June, depending on the weather, but in July these insects begin to hatch, as is well known to the Cherkasy women. They more willingly collect these hatched insects rather than the vesicles, because they produce a cleaner and better dye… The collected insects are rolled in a sieve to clean the dirt from them, then they dry them in a pan in the oven or over coals which emit a low heat. Because of the difficulty in this collection, they intentionally sell this cochineal for a dear price.” This is followed by a description of how to dye yarn and belts with cochineal.[105]Puteshestvie po raznym provintsijam Rossijskoj Imperii P.S. Pallasa. Part 1, St. Petersburg, 1773.

The Russian cochineal insect described by Pallas was well known even earlier not only in Russia,[106]cf. “чрвлена чолка” in the Lay of Igor’s Campaign. but even far beyond its borders. Heinsius’s Allgemeines Bücher-Lexicon, published in 1741-1742 in Leipsig, also contains pretty complete information about the cochineal insect collected by peasants in Poland and Ukraine, in the summer around St. John’s Eve (June 23), and which was therefore called St. Johannis Blut.[107]Allgemeine Schatzkammer der Kauffmannschaft u. s. w., Leipzig, verlegt v. J.S. Heinsius. Part III, 1741, p. 1023. Aside from German merchants,[108]Kljuchevskij, Skazanija inostrantsev o Moskovskom gosudarstve, pp. 252-253. Russian cochineal was also sold to the Armenians and Turks, who used it to dye wool, silk, and leather, especially for goatskin leather, and for horsetails used in bunchuki.[109]Dnevnik general’nogo khorunzhego N. Khanenka (1727-1753 gg.). Kiev, 1884, p. 96.[110]jeb: See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tug_(banner). The Dutch used it to make a cochineal which significantly improved the color. The so-called Carta di Spagna and the Turkish Pezette di Levante were made from the same cochineal. By 1585, the royal agent Gersey along with various other goods was purchasing cochineal for the court. A few decades before Pallas’s journey (1773), cochineal was sold everywhere, and in Moscow cost 20 kopeks for 3 zolotniks (about 12.8 grams).

In later Russian painting technique literature, there are no indications of the applicability of this carmine, which mainly went to the dyeing industry, to oil painting; but, it was doubtlessly practiced. Vermiculus was the insect from whence vermillion originally came, and cinnabar was used to replace this pigment, which was essential for book-writing and illumination.[111]I.I. Sreznevskij, having studied Grand Prince Mstislav’s letter to the Novgorod Jur’ev monastery (1130), written in gold paint, found that “the gold was bound with a vegetable glue, which now to the naked eye seems brown in color, but under the microscope is a purplish color, and which most likely was originally cherry colored.” The pigment dissolved in this glue, the so-called “embellishment” (jeb: “прикрас”, “prikras“), was most likely now-faded ink. The gold dyed with carmine was possibly called “carmined” (Rus. червонный, chervonnyj). The author of the late 11th century Anonymus bernensis mentions the creation of carmine paint using egg white glair. Among Slavonic manuscripts, we among the South Slavs, we find some with quite faded “cinnabar” made from cochineal.[112]The Greeks had their own form of cochineal, as mentioned by Pausanius, X, 36.

Having replaced the Russian cochineal, its cousin the Mexican cochineal also blotted from the people’s memory its characteristic bright pink-red dye, which came to be called carmine. But the word cherlen’ did not disappear without a trace. It was long preserved as mineral cherlen’, a cheap surrogate for that of animal origin.

Starting in the 16th century, and possibly even earlier, in Northern Russian literature, the words chervlen’, cherlen’, chernen’, chernil’ and even chern’[113]jeb: These words show a progression from the Russian cherlen’/cherv’, meaning “insect” and indicating a color red, toward the Russian chern, meaning “black.” Hence the confusion described in this paragraph. were used to indicate the very common in nature red and reddish-brown earthy dyes of varying shades colored by (anhydrous) iron oxides, which were used in compounds in varying amounts.[114]In cases where it contained manganese as well as iron, the color became darker, similar to umber or raw Sienna. As such, influenced by this new material, the concept of the insect-based carmine was gradually lost. Modern iconographers know of cherven’ from their iconographic sourcebooks as a color term, but largely under its later meaning and think of it as blackish, rather than reddish. These pigments, found everywhere, number among the most ancient, known already to prehistoric man.[115]For historical data about natural, red, iron-based pigments being known in antiquity as Sinopia, Bolus, et.al., cf. Cremer, F.G. Studien zur Geschichte der Oelfarbentechnik. Duesseldorf, 1895, p. 116.[116]Manuscript XXIV.[117]Manuscript X. The words “slimy” and “mucous” were also used to describe thin Kolomna ochre.

In Russia, carmines differed by their origin and their quality, including Pskovian carmine, German carmine,[118]Manuscript XXIV. “черлень слизуха” – “slimy carmine,” and the highly valued “черлень плавленая” – “floating carmine” which was purified through decantation.[119]Manuscript XLII.[120]Manuscript XXXV. The first two were characterized as “черлень скопская туга, черлень немецкая красная аки немецкий бакан” – “Skopje banner carmine, and German red carmine, like German carmine.”[121]On German carmine (Rother Bolus) found in many locations in Germany, and on the excellent crimson found in Livonia near the city of Wenden, cf. Croekern, J.M., 1736, p. 99. In an Ankhangel’sk manuscript from the late 17th century,[122]Manuscript VII. it mentions that one pound of carmine, similar to chrome green, cost 2 altyns, or only about twice as much as ochre; it seems, then that this pigment was one of the cheaper ones available.

The better varieties of carmine have been used since ancient times by painters to create flesh-tone paints and in the painting of faces. The Athonite Herminias recommended for this use the very similar bole, both of which were used to shade in faces and the outlines of hands, as well as to “писать уста” – “paint mouths.”[123]Manuscripts XLII, XXII. In Theophilus’ writings, the role of carmine was played by the mineral rubea.[124]jeb: Burnt umber. Russian iconographers added it to the sankir’ used for faces, as well as to the first layer or “facial” ochre, or “черлень скопская” – “Skopje carmine,” and used the same ochre mixed with a bit more carmine to shade in faces.[125]Buslaev, F. Drevnerusskaka narodnaja literatura i iskusstvo. Vol. II, p. 393.

The author of an excellent description of the iconographic image of the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God (17th century) wrote: “устье ко всенепорочные червленою красотою побагрене” – “the mouths are an immaculate scarlet, drawn with carmine paint.” Carmine also went into the ornamental case (riza); scarlet was painted using ink mixed with carmine, the mountains were painted in whitened ochre darkened with crimson, etc.[126]Manuscript XLII.[127]Manuscripts VII, XXIV, XXVI.

Along with the earthy pigments ochre and chrome green, the durable crimson played an extremely important role as an essential component in the greenish pigment sankir’ and the lighter toned first layer of ochre, consisting of ochre mixed with a large amount of carmine or the similarly toned burnt umber. This ochre was used to lightened the sankir’ of hands and faces, and was then followed by the even lighter second ochre, which was mixed with white lead. Sometimes they would create an undertone of sankir’ strengthened by an admixture of carmine.[128] Manuscripts VII, XXIV, XXVI. [129]Manuscript XXIV.[130]Manuscript XXVI.[131]Manuscripts XLIV, XLVI.[132]Manuscript. XXXVIII.[133]Manuscript XXXVII.[134]Manuscript XXIX.

Carmine was used to tint levkas or gesso on canvas for painting in oils (18th cent.). As one of the cheaper pigments it was quite freqently used in poliment under gilding, or was used to cover white levkas intended for gilt items (for example, wooden loving cups). Bookbinders painted it onto the edges of books intended to be gilt.[135]Manuscript XLVI. As a result of an obvious mistake by the copyist, who dropped the first letter, in a late 18th century collection belonging to I.P. Pogodin published by Rovinskij, instead of “алая” (“scarlet”), we find written “лая” (“barking”), paragraph 86. This mistake was included as an actual name for a paint color in the alphabetical index by Rovinskij, and later figures as a medieval Russian color in Ageev’s Tekhnicheskie zametki po zhivopisi. Vol IV, iss. 6, 1886, pp. 453, 461, 463. For oil painters, as a sticky paint, carmine served all kinds of purposes: for example, when ground with an equal part of chalk, it was used as an oil paint; when mixed with lampblack and applied to a surface primed with lightened ochre with the assistance of a moistened wad of canvas, carmine was used to create an effect of walnut trees.[136]Manuscripts XXXVI, XLV.

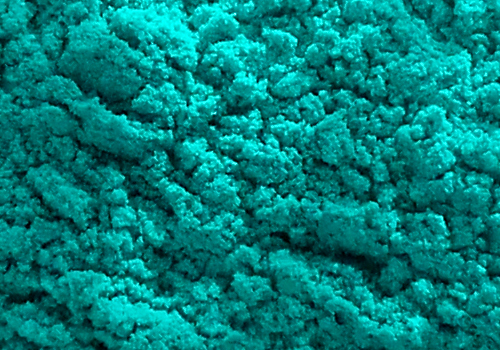

Verdigris (Ярь)

Yar’ or verdigris (Rus. ярь-медянка, jar’-medjanka) was the common Russian term for various copper-compound, artificially-prepared dyes.[137]The paint word jar’ can hardly be called a native Russian word; for example, it has nothing in common with the similar words jar’ meaning “spring bread”, jarilo meaning “deity”, jar’kij meaning “bright, sparkling” (medieval jar’ was not a bright colored paint, see more below). Along with the majority of the oldest words indicating pigments, the word jar’ most likely came from the Byzantine Greek word τξιγχιαρι, which meant exactly the same color of paint. The suffix “ari” or “jari,” which is more familiar to Slavic consonance, had already acquired meaning as a noun in Russia, while the foreign-sounding root “tdzinki” or “tsink’jargi” was lost over time.

Copper’s ability, when mixed with various acids, to create green and blue salts which were suitable to use as pigments was first noticed and used quite long ago. It has not lost this significance in the technology of modern times. The earliest known of these compounds was copper acetate; this common aqueous acetic copper salt now carries the name verdigris, from the term vert de Grèce, or viride graecum in medieval Latin.[138]In later Greek sources, the barbarism βαρδαραμον, vardaramon, from the Roman verderame, same into use to mean verdigris. It was already known to Pliny, who indicated how to identify whether it contained impurities of ferrous sulfate.[139]With the help of oak gall extracts. Its method of production is recorded by Heraclius (Modus faciendi viridem cupri vel aeris – The method of making green copper).[140]Heraclius, III, XXXIX. Theophilus also includes a method which produces similar results (De veridi hispanico – On Spanish green).[141]Theophilus, XLIII. Dionysius of Fourna, in accordance with the previous two authors, describes its creation thus:

В медный сосуд положи опилки меди с крепким уксусом, накрой его и поставь в таком месте, где сильно жжет солнце в жаркое время, пока сгустится уксус. Потом вынь эти опилки и положи в другой сосуд, чтобы осохли.[142]Herminia, 42.

Place copper filings into a copper vessel, together with strong vinegar, cover it, and put it in a place where the sun burns strongly in hot weather until the vinegar thickens. Then remove the filings and place them in another vessel to dry out.

The core principle of the methods recorded by these three authors, as well as many other Western European right up through modern day, is the action of acetic acid in a closed vessel in warmth upon metallic copper. Russian literature on the preparation of verdigris is quite extensive, but, unfortunately, has been preserved in manuscripts no earlier than the early 18th century. The simplest recipes accurately, and even almost word for word, repeat the simplest recipes from Western European authors, further developing into several original variants, which diverge only in one, very important point, the reason for which is easy to see. Russian artisans did not have cheap vinegar, which was always abundantly available to South-Western craftsmen from Spain to Byzantium in the form of common grape-based table vinegar, accidentally soured wine, or fermented grape pomace.

The words оуть (out’) and уксус (Rus. uksus, vinegar) are, of course, not foreign to the Russian ear.[143]Out is from the Latin acidum, acetum, found in translations of the Gospels, which given the lack of a corresponding Russian word, is shown here without translation. Uksus comes from the Greek όξος, oksos, “vinegar”. “Old out’” (оуть старыи) and “sour out’” (оуть кислыи) are mentioned in Russia as early as the mid 15th century. In 1525, according to Herberstein, vinegar was typically provided as a condiment at the royal table. At the same time, imported “Rhenish vinegar” (уксус ренскии) was well known. The expressions “honey kvass” (квас медвяныи) and “bitter honey vinegar” (уксус медвяныи жестокии) suggest that this was not always an imported product. But this does not, however, allows us to think that vinegar was in common use even in later times, much less during the dawn of Kievan and Novgorodian painting, when, one must think, under the influence of fresh Greek traditions, the Russian method for the production of verdigris was reworked.

Not having access to vinegar, Russian artisans replaced it with sour milk. This is what one, apparently very ancient, recipe dictates:

Указ како ярь составити. Молока кислово твороженново положить в сосуд медной, красной меди, не луженыя, да класть куски медные же в то молоко и запечатав поставити в тепло на 12 дней или больше, и распечатав, вынув засушити: станет ярь.[144]A completely analogous phenomenon is also noted in the process of Russification of a Western European method for preparing white lead.

On the production of verdigris. Place sour curdled milk into a copper vessel, of red copper which has not been tinned, and place pieces of copper into the milk, and having sealed it up, place it in a warm place for 12 days or more, and having unsealed it, remove it, and it will be verdigris.

Another often repeated, quite complicated recipe reads:

Возми горшок медный да сыра четверть, да молока преснова безмен, да купоросу семь [золотников] и положи в горшок и покрой покрышкою медною и запечатай тестом и положи в печь, на две недели, да мечи куски меди там в горшок.[145]Manuscript XV.

Take a copper pot and a quarter of cheese, and a bezmen[146]jeb: a medieval Russian measure of weight, about 2.5 pounds. of fresh milk, and seven zolotniks of vitriol (sulfate), and cover it with a copper lid, and seal it up with dough, and place it in the oven for two weeks, and add pieces of a copper sword to the pot.

Three sets of directions for creating verdigris are found in a row in the Typikon by Bishop Nektarios:

Возми молока кислого творогу и положи в медной сосуд, да медным же и покрой; да тут же положи всяких крох медных; да тут же положи листу веничного или травы всякие зеленые и держать месяц, смотреть в месяце четырежды, и вымешивать, чтоб зелено было; а держать в тепле на печи, а сучить исподволь в тепле же.

Take some sour milk curds and place them in a copper vessel, and cover it with a copper lid; and add to it any kind of copper “crumbs;” and also place there a broom leaf or any kind of green herbs, and let it sit for a month, and look four times a month, and stir it so that it will become green; and keep it in a warm spot on the oven, and gradually turn it in the heat.

Another reads:

Возми сыр козий молодой из творила, да против четверти сыра соли, да против четверти сыра меду пресного и положи в медный сосуд и поклади меди и покрой медью же и поставь сосуд на солнце в зной на три недели.

Take [one part] young goat cheese from its mold, and add one quarter part salt, and one quarter part fresh mead, and place it into a copper pot, and add copper, and cover it with copper, and place the vessel in the sun in a warm place for three weeks.

And finally:

В судно медное налить кислого молока, да крохи сырные, да крохи белильные и смочи молоком кислым и поставь на две недели, такожь и медью покрой.[147]Manuscripts XVIII, XXXVI, XXXVII.

Into a copper vessel[148]jeb: судьно meaning сосуд, “vessel”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 609. pour some sour milk, and cheese crumbs, and crumbs of white lead[149]jeb: белильный means “bleaching” in modern Russian, but possibly here from белила, “white lead” ??, and moisten it with [more] sour milk, and let it sit for two weeks, and cover it also with copper.

Replacing the vinegar with sour milk, of course, led to completely different results: instead of copper acetate, they obtained copper lactate, which also had a significant admixture of casein which further changed the outer appearance and quality of the pigment. This admixture, however, could have been intentional. The colloidal cheese curds, which dissolved the caustic salts, played the role of a substrate, an opaque carrier of the pigment, and others began to add it to their pigments as such.[150]Manuscript XXXVIII. The color of the paint achieved, as can be seen from the paints in illuminations, and which we can easily be convinced of given the recipes above, was a quite indefinite, dirty, and dull greenish-blue, which was not satisfactory to artists. They attempted to improve upon it, adding the “broom leaf or any kind of green herbs,” sulfate (copper, of course), or even white lead.[151]For both of the following recipes, see also manuscript XI. The origin of the second method presented by Bishop Nektarios would be difficult to call a Russian variant of the method presented by Dionysius of Fourna, which was almost identical to Theophilus’s recipe for “Spanish green.”[152]Theophilus, XLII.

The aforementioned use of salt, mead, or three weeks in the heat of the sun are not found in any other recipes, but we do find them in Theophilus, in his article entitled De viridi salso (“On green salt”), as well as in Heraclius’s Quomodo efficitur viridis color cum sale (“How to create green color with salt”),[153]Heraclius, III, XXXVIII. which served, it seems, as a source for the previous author. This recipe seems to have ended up in Russian collections by chance.

In addition to homemade verdigris, it was also sold as “bars of verdigris,” which may have also been an item of local production.[154]Manuscript XLII. In lists of paints imported in the 17th century through Arkhangel’sk, we find both types of green: verdigris, and Venetian verdigris.

Quite different is an interesting recipe from a 17th century Novgorodian manuscript: “Взяти гороху, на мочить 15 дней и больше, да столчи, да по тому же составити с медью” – “Take peas, and soak them for 15 days or more, and for that same number of days, let it sit for the same number with copper.”[155]Manuscript XV. As opposed to the usual method for creating verdigris, this paint is called prazelen’ (Rus. празелень, “blue-green paint”). The formation of copper pigment under these conditions may be related to the direct influence of an enzyme generated during the germination of the peas, as well as the effect of the fermentation by-products on copper during the formation of sugars from starch.

Artisans attempted to improve the color of verdigris, first of all, by tinting it with all kinds of yellow paints:[156]Russian verdigris was not the only one that needed this touch up. Chennino Chennini also found his verdigris to be insufficiently green. In order to paint plants or green, he mixed three parts verdigris with one part saffron. Cennini, 49. “Буде похощешь ярь, чтоб зеленью учинить мало шафрану задать или ревеня” – “To make your verdigris green, you will want to add a little saffron or rhubarb.”[157]Manuscript XXIV. They also added realgar/orpiment (Rus. ражгиль, razhgil’), shishgil’ (Rus. шишгиль, a bright yellow pigment made from buckthorn berries), or cow’s bile. Secondly, they would influence its chemical composition by adding alum:[158]Manuscripts XXVIII, XXXVIII.

Ярь терти с квасцами на камени, велико становится и буде цветно[159]In modern Russian, ярко, jarko, “bright”. надобе писать и тою составною ярию пиши, или же уксуса и вина.

Grind verdigris with alum on a stone, it will become great and bright for painting, and if you need to paint use that compound, or mix it with vinegar and wine.

A more demanding artist recommended using both methods for improvement at the same time:

Ярь терти на уксусе ренском, зелено будет, захочешь того зеленее и ты шафрану подпусти и пиши кистью и пером.

Grind your verdigris into Rhenish vinegar, and it will be green, or if you want it even greener, then add saffron, and paint with a brush or quill.

With the exclusion of fresco painting, where Russian verdigris, just like its Green and Italian counterpart, was found to be unsuitable, this cheap, homemade pigment was used everywhere, although often with certain precautions.[160]Manuscripts VII, XXX, XXXVIII. On its use in iconography, Nikodim Siysky writes:

Ярь медянка яйца не любит … закиснет мало мало меду задать с яйцем … таж ярь медянка и на яйце мощно потребить аще белил довольно совокупишь и будет зелена и поспешна к делу.

Verdigris does not love egg white … it will turn a bit sour if you add a little mead with egg white … also verdigris can be used with egg white if you thoroughly mix in some white lead, and it will be green and useful for your work.

He also warns illuminators:

[Ярь] чтобы не линяла с бумаги, возми скапидару да влей на камень и на нем три ярь крепко весь день, что бы утерлася мелко, и возми кисть или перо и пиши на бумаги, что хочешь.

Lest [verdigris] fade from the page, take turpentine and pour it onto a stone and [grind] three [parts] verdigris firmly upon it all day, until it becomes fine, and then take your brush or pen and write upon paper whatever you wish.

The use of verdigris in book painting, however, is far from safe; it has a destructive effect on parchment and paper.[161]Manuscripts VII, XXX.[162]Manuscript XXXVIII.[163]Herminia, 66; Cennini, 72.

Verdigris was especially widely used in all kinds of artistic craftwork. Pure verdigris, or verdigris mixed with shishgil’ was used to paint the edges of books, and it was also “useful” for oil painters.

Ярь медянка с маслом вельми потребно писать скатули, подголовашки и по каменю и по железу; стирать на плите ручником на масле льняном или на скапидаре и малу белил задать, а буде хотя мало нефти, буде есть, а можно и без сих на едином масле льняном утерти довольно, и прикладывай пиши, что тебе потребно.

Verdigris with oil is quite useful for painting chests, head rests, on stone, and on iron; mix it with linseed oil on your palette with a spatula, or with turpentine, and add a little white lead, or with a little mineral oil if you have any, or you can just mix it with linseed oil, and then use it to paint whatever you need.

When mixed with carmine on a squirrel fur brush, it was used to paint the crowns of loving cups. In general, in places where other paints were less useful, “можно тех место, ярью медянкою наполнить” – “one could fill in those places with verdigris.” The addition of white lead was particularly recommended. One later artisan wrote:

Когда ярь одна на олифе разведена будет, то оная во время сушения ежедвенво темнее становится, для чего должно оную пополам с белилами мешать.

When verdigris is mixed with linseed oil alone, then it will over time darken day by day as it dries, to prevent this, it should be mixed with a half part of white lead.

Along with carmine, verdigris was a preferred paint for various kinds of materials, as well as glass. Both are transparent glazes, and therefore quite well suited to situations where it was undesirable to completely cover the underlying material, for example when painting on gold or silver. One detailed article talks about how to mix them with turpentine and a small addition of linseed oil for this purpose, and how to paint with them such that the result would be “чисто и уветно” – “clear and covering.” Verdigris was also used to paint on metal, mixed with ammonia or sometimes with vitriol:

Буде по золоту или по серебру или судно какое и нибудь золотое или серебряное или медное или оловянное или булатное или захощешь травы навесть, положи и смеси ярь с нашатырем на воде и пиши ино будет крепко.

Whether you want to paint on gold, or silver, or any kind of vessel of gold or silver or copper or pewter or damask, or if you want to cover them with herbs, take and mix verdigris with ammonia in water, and paint, and it will be strong.

Verdigris was also added to various compounds and paints used in gilding with gold leaf, and under gold in poliment. This usage was according to Greek traditions. It was also used by artisans in gold work in compounds called gold-coloring, intended to add shades of gold to one’s work. As a copper salt, verdigris was useful along with lead compounds in the boiling of “good linseed oil” was it was especially used when it was required to hasten the drying, and where the color of the oil did not play an important role; for example, when painting under gold in ships’ holds, or when dry gilding “touch free.”[164]Russian artists, however, who did not fear the formation of black copper sulfide, mixed verdigris with cinnabar and realgar.[165]Manuscript XXIV.[166]Manuscript XXXVIII.[167]On this, see also Alcherius (1398). For examples, see his chapter on “Book Art.”[168]Manuscript XXVII.[169]Manuscript XXIV.[170]Manuscript XXXVII.[171]Manuscript XXIV.[172]Manuscript XLV.[173]Manuscript XXXVIII.[174]Manuscript XXVII, XLVIII.[175]Manuscripts XXVII, XLVIII, XXXVIII.[176]Manuscript XLVI, XLVIII, XXXVIII.[177]Herminia, 69.[178]See the chapter on Olifa.

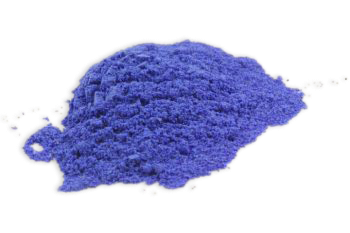

Venetian Verdigris (Ярь веницейская)

Along with verdigris which was frequently home-made, in various lists of paints and articles on painting techniques, we often also see imported “Venetian verdigris” listed. As opposed to plain verdigris, its Venetian counterpart was a quite expensive paint, which is why it was rarely used, for the painting of various items made of wood. The thrifty Nikodim Siysky wrote:[179]Manuscript XXIV.

Дорогие краски бакан веницейский и ярь веницейская довелось их сначала с водой терты убыли меньше, и яйцы мало задавать, и писать потребное иконы или разцвечивать позолоту и по се ребру, или заставицы употреблять разцвечивать везде потребны.

The expensive paints Venetian crimson and Venetian verdigris should first be ground with a little water, and add a little egg white, and then paint the necessary icons, or use it to color gilding or silver, or use it to color in any kind of headpiece.[180]jeb: заставица meaning заставка, “headpiece”, or a large illumination at the start of a page/chapter; Sreznevskij, op. cit, vol. I, p. 948.

The late 17th century artist was thinking of book illumination,[181]Manuscript XLII. placing it next to plain “медянка брусками” – “verdigris in blocks” in his article “Роспись красками, кой на камеди растворяются” – “On the painting with pigments which dissolve in gum.”

In a list of paints with prices by one artist from the early 18th century[182]Manuscript XXXV. who was not very solid in his knowledge of color nomenclature, along with Venetian verdigris, we also find Ярь турская – “Turkish verdigris” as the most expensive paint mentioned. The end of the list has not survived. A zolotnik of it cost 10 dengas, or 2 altyns and 2 dengas, or 2 altyns and 4 dengas.[183]The price of Venetian verdigris depended, it appears, on its quality, and therefore was always changing. For example, in a Muscovite list of paints from 1667, a zolotnik cost around one altyn retail (Uspenskij, A. Tsarsk. ikon. i zhiv. Vol. I, p. 311), and in 1662 in the same location, it cose 4 dengas (idem., vol. III, p. 320.) We have somewhat conflicting data on the color of this verdigris, but nevertheless it should be considered as more of a bluish, rather than greenish pigment. In a list from the early 19th century (1803),[184]Manuscript XLV. among the green paints, Venetian verdigris is listed first, followed by sap green (Rus. сафтгрин, saftgrin, from Ger. saftgrün) and mountain green (Rus. берггрен, berggren, from Ger., “mountain green”, a pigment made from malachite), pigments which are undoubtedly green, but it is also listed with indigo (Rus. крутик, krutik) and Prussian blue (Rus. Лазорь берлинская, Lazor’ berlinskaja, “Berlin azure”), as a pigment which can be mixed with gamboge (Rus. гуммигута, gummiguta, a deep mustard-yellow pigment) to make green. Bishop Nektarios[185]Manuscript XXXVIII. saw it as a light blue pigment, which when mixed with white lead would produce dove blue (Rus. голубец, golubets, a light-blue-grey pigment typically created by mixing hydrated cupric oxide (black) with calcium carbonate (white)). Based on this data, it is difficult to guess its true nature, but if it is true that the word yar’ was used to characterize not so much a color (given that Russian verdigris was after all categorically neither very green, nor bright), but rather indicated that it belonged to the category of copper pigments, then one can assume that in known situations, the name indicated one of the light-copper-blue or greenish pigments, of which quite many were in use by Italian artists from the 15th-17th centuries. For example, in Raphael Borghini’s Il Riposo (1584)[186]Raph. Borghini. Il Riposo. Firenze, 1854, Vol. II, p. 241. we’re able to count 6 in total: Azzura di biadetti, Azzura della Magna, Azzura commune, and 3 Azzura d’artificio, of which the first two were natural, and the rest were artificial.[187]Alb. Ilg, footnotes to Trattato Cennino Cennini, Vienna, 1888, p. 157. A light blue artificial pigment which was called “Venetian,” was also used by the old German masters. In a manuscript by G.B. Pictorio, Illuminir-Kunst (1730),[188]“Ein Venedisch Himmel blau zu machen,” p. 373; the recipe appears to have been distorted by the scribe, as copper is not involved in the preparation of this paint. we even find an article on how to prepare them.

Blue-green (Празелень)

Over the course of the later, comparatively speaking, period of our literary sources, the word prazelen’ (Rus. празелень) was often used to mean any paint consisting of blue or blue-green mixed with yellow of various types. One Northern-Russian master from the 16th-17th centuries[189]Manuscript VIII. wrote: “Желтый положи часть и сини две и пол и составя також три и будет празелень” – “Take one part yellow and two and a half or three parts blue, and you will have prazelen’.” Another artisan from the 17th century provided a full list of compositions known to him for this color in his article “Указ празелени” – “On the making of blue-green”:[190]Three numbers are skipped in the manuscript. – M.F.

- празелень, ярь, бель, шафрану больше

- празелень, ярь, желть

- празелень, ярь, бель

- празелень, желть, синь

- празелень, желть, синь, бель

- празелень, вохра, синь

- празелень, вохра с чернилом, синь

- Blue-green: verdigris, white, a lot of saffron

- Blue-green: verdigris, yellow

- Blue-green: verdigris, white

- Blue-green: yellow, blue

- Blue-green: yellow, blue, white

- Blue-green: ochre, blue

- Blue-green: ochre mixed with ink, blue

A somewhat later artist made it from indigo and yellow, and made dark prazelen’ completely without blue, using ochre and ink.[191]Manuscript XV.

But while the aforementioned artists knew only of prazelen’ made up as composites, in other locations we find indications that such a paint did exist. For example, one master who indicated that he knew of verdigris, Venetian verdigris, green, and even some kind of unknown “зеленая желчь” – “bile green,” and, it follows, was knowledgeable about the green colors which existed, mentions in one list “празелень брусками, цветом синевата” – “prazelen’ in blocks, bluish in color.”[192]Manuscript XXXIII. Another master from around the same time (late 17th or early 18th century) even noted the price of this inexpensive paint: празелень или прасиней краски по два алтына фунт” – “blue-green or bluish pain for two altyns a pound.”[193]Manuscripts XLVI, XXXVI, XXXIV.[194]Manuscript XLII. In a list of paints from the late 18th century, the color is nowhere to be found.[195]Manuscript XXXV.

This purchased blue-green paint was used in iconography primarily “писать поля свет” – “to paint the fields of light” and in the landscape sections to paint “trees, greenery, earth, and mountains” where no particular brightness was required.[196]Manuscript XLV. Its primary use was in wall painting.[197]Manuscripts XLII, XLIX. In one common article “Устав стенному письму” – “On the painting of walls,”[198]Manuscript VII., the only green mentioned is prazelen’, where it says:

А празелень будет только на высушке не хороша либо плесневеет и ты в ней задавай чернил по мере.

Prazelen’ alone will not be good when dry for it will grow moldy, you must add to it an equal measure of ink.

In another variant of the same directions,[199]Manuscript XXVI. we find, “К лицам в санкирь задать черлены псковской, празелени” – “On faces, you must add Pskovian carmine or prazelen’ over the sankir’.” Bishop Nektarios also speaks about prazelen’s usefulness for wall painting.[200]Manuscript XXXVIII. In a list of paints requested by artisans for painting the walls of Moscow’s Dormition Cathedral in 1642, it mentions:

… вохры грецкие 5 пуд, да празелени грецкой 6 пуд, и тех дву красок здесь нет. Прежде всего та краска приходила из Царяграда, а без той вохры и без празелени стенное письмо не крепко.

… 5 poods[201]jeb: A medieval Russian measure of weight, equaling 40 pounds. of Greek ochre, and 6 pounds of Greek prazelen’, and those two paints are not here. Previously that paint came from Constantinople, and without that ochre or prazelen’, the wall painting will not be powerful.

The same list also mentions German prazelen’.[202]Uspenskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 6.

The fact that this prazelen’ was primarily used for wall painting serves as an important clue toward its definition. A no less important clue is provided by the thorough and multi-faceted Siysky artisan.[203]Manuscript XXIV. Speaking about paints “у больших дел” – “used for many things”, he includes prazelen’ and ochre in the group of paints which “переплавивают” – “swim through,” that is, which precipitate in water (for example, “floating” or precipitated chalk, aka whiting chalk), by which he indicates its earthy character. Having thus noted the characteristics of this pigment — bluish-green, dull, earthy, resistant to both light and caustic lime, and inexpensive — we can with some certainty attribute it to the group of natural green pigments, which includes Verona green (terre verte), Bohemian green earth, et.al., whose colors are based on the mineral glauconite. This paint was quite common, and it numbers among the earliest pigments. The Athonite masters called it “green stone” (Gr. πλάχα πρασίνη, plakha prasine), and they also used it for wall painting on gesso in general, and in particular (as in Russia) in the layering of flesh colors along with our sankir’, and our Pskovian carmine played the same role as Greek yellow ochre.

The Greek word for this green paint, πρασίνη/prasine, is closely related to that used by Theophilus in his article “De colore prasino.” The expression “prasius” or “Prasium-Stein” to indicate this green stone is also found in German dictionaries from the 18th century. [204]Chaptal found green earth in a paint-seller’s pot in Pompei. See also, Alb. Ilg, footnotes to the trasnlation of Cen. Cen., Wien, 1888, p. 153. Its influence can also be seen in the Russian word prazelen’. Along with this Russified form, the Greek term was preserved to mean the color gold, or in some places, just to mean “paint” in its simpler form. The compiler of the Azbukovina (late 16th century manuscript),[205]Azbukovnik i skazanie o neudoboponimaemykhrechakh i t.d. v Skazanijakh russkogo naroda, sobrannykh Sakharovym. St. Petersburg, 1849. Vol. II, p. 179. for example, translates it as “прасино, зелено” – “bluish, green.” It appears that he had in mind the artisan cited above, who identified prazelen’ as a bluish paint.

The Russian deposits of green earth were quite numerous,[206]Fersman, A.E. (ed.) Khimiko-tekhnicheskij spravochnik. I: Iskopaemye sery. Petrograd, 1919, p. 24. but it is impossible to say whether even one of these was used by Russian painters. The only developed deposits are located in the vicinity of Koporya, in the Leningrad region. In Estonia, near Revel, green earth was discovered in the first half of the 18th century.[207]J.M. Croekern writes about green earth: “Dergleichen Art Erde habe ich bey Reval in Estland am Thume so sich dasselbst in grosser Menge zeiget wahrgenommen; sie ist aber night allzu helle un von so schoener Farbe als die Englische.” (“I perceived this type of earth at Reval in Estonia on the Thume, such that it shows itself in great numbers; but it is not very bright, nor of such beautiful color as that found in England.”) Croekern, J.M. Der wohlanfuehrende Mahler. Jena, 1736, p. 100.

Mountain Green (Зелень)

Aside from the artificial copper and green earthy greens, Russian artisans may have also had a natural green copper-based paint, which was called by 16th century Italians verdetto della Magna (mountain green), and which is prepared from the mineral known as “green copper”, or malachite. But, it is difficult to say whether it was actually used in the Middle Ages, based on the literary data.

In those situations when we find in one manuscript or another the paints prazelen’ and zelen’ (Rus. зелень, bright or mountain green), we see that the former was applied as a less bright paint as a background or landscape details surrounding the central figures, while the latter was used for bright clothing. For example, we read:

А ризы писать красками разными: бакан разбелить, голубец ребеляй и зелень.[208]Manuscript XLII.

And paint the robes with various colors: lightened carmine, lightened dove blue, and bright green.

Or:

У сына [божия] верхняя риза – зелень, мешать вместе с белилами, шишгелю положить троху, исподь киноварь.

The Son [of God’s] upper garment shall be bright green, mixed with white lead or buckthorn yellow (shishgel’), and lay it down with a reed[209]jeb: трох >> трость, тръсть meaning стебель тростника, “a reed stalk”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1013. over cinnabar.

In the same collection, we also read, in the description of the image of St. Sergius the Miracleworker’s vision: “У Иоанна верх зелень, исподь киноварь одинок” – “St. John’s upper clothing is bright green laid down over cinnabar alone.” We further read, however that this zelen’ is a mixed paint:

У богородицы ризы крыть: верхняя риза бакан разбелить, исподь голубец, класть белила. У ней же у края ризы вывороток крыть зелень-зеленью, голубец разбелить и положить шишгелю троху малую.[210]ibid.

To paint the robes of the Mother of God: for the upper garment, lightened carmine over dove blue, and add white lead. For the edges and lining of her garment, paint bright green, lightened blue, and add buckthorn yellow with a small reed.

The author of a 1687 Podlinnik (Icon Painter’s Guidebook) writes:

Поля свет также празеленные и санкирные, кроме зелени, бакана, и киноварь, всеми делать.

Everyone paints the fields of light with blue-green and sankir’, along with some bright green (zelen’), carmine, and cinnabar.