Today’s post is Part I of a translation of Russian Historical Costume for the Stage, a book written in 1945 by N. Gilyarovskaya. This work has extensive research into historical clothing from the Kievan Rus and medieval Moscow periods, with many source images, as well as discussion about how to reproduce items of clothing for the stage. Although it is obviously a product of the Soviet era in which it was written (Stalin good! Feudalism bad! Long live the proletariat!), the book provides a great synopsis of medieval Russian history, as well as an overview of items worn by Russians in the SCA medieval period. Parts II and III give an overview of period fabrics, as well as patterns and practical descriptions of various items of clothing worn in period, and will follow soon in a separate post. I hope you enjoy!

A translation of Гиляровская, Н. Русский исторический костюм для сцены: Киевская и Московская Русь. Москва-Ленинград, 1945. [Giljarovskaja, N. Russkij istoricheskij kostjum dlja stseny: Kievskaja i Moskovskaja Rus’. Moscow-Leningrad, 1945.]

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This work also contains an extensive glossary below; see the table of contents.

This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here (note, requires a .djvu file reader):

Русский исторический костюм для сцены: Киевская и Московская Русь. Where possible, I have replaced the black and white source images in the original with color images found online. Click on the image thumbnail to open the image full screen in the lightbox; from there see the “i” button in the lower left to view any additional notes Giljarovskaja may have given about that image.]

Russian Historical Costume for the Stage: Kievan and Muscovite Rus’

Collected by N. Gilyarovskaya, with assistance from members of the Academy of Sciences S. Bogoyavlenskij, N. Vorob’ev, and O. Gapanova.

State Publishing House “Iskusstvo”, Moscow/Leningrad, 1945.

Years of great national shock mobilize the will of the people. In a powerful, unstoppable urge to protect the homeland, love for it escalates, and like a bright flame, interest in the matters, feelings and feats of its ancestors flares up. In his speech at the Red Army parade on 7 November 1941, Comrade Stalin stated, turning to his warriors: “A great liberative mission has fallen to you. May you be worthy of that mission! The war which you wage is emancipative and just! May the courageous image of our great forebears – Aleksandr Nevskij[1]jeb: 1221-1263, Prince of Novgorod and Grand Prince of Kiev and Vladimir, defender of Rus’ from German and Swedish invasions, made a saint in 1547. See here for more details., Dmitrij Donskoj[2]jeb: 1350-1389, Prince of Moscow and Grand Prince of Vladimir, victor against the Tatars at the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, made a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church. See here for more details., Kuz’ma Minin[3]jeb: ?-1616, merchant who became a hero with Dmitrij Pozharskij for defending Russia against a Polish invasion in 1611-1612. See here for more details., Dmitrij Pozharskij[4]jeb: 1577-1642, Russian prince who, with Kuz’ma Minin, led the resistance against a Polish invasion in 1611-1612 and was dubbed “Savior of the Motherland.” See here for more details., Aleksandr Suvorov[5]jeb: 1729/30-1800, Field Marshal of the Russian Empire and considered one of the greatest military leaders of all time. See here for more details., Mikhail Kutuzov[6]jeb: 1745-1813, Field Marshal of the Russian Empire, led the military effort which defeated the Napoleonic invasion of Russia. See here for more details. – inspire you in this war!”

The great deeds of our fathers and grandfathers came to life in the historical memory of our people. Our literature was enriched by works on historical themes, glorifying our heroic patriotic ancestors.

A great role in carrying out this patriotic task that was imperiously dictated to art and literature by the Great Patriotic War[7]jeb: Russian term for World War II. has been filled by Soviet theater, which possesses the most expressive and visual means of influencing the masses. Arias from the classical operas Prince Igor’ by Borodin and Ivan Susanin by Glinka resound anew. The work of modern writers and playwrights had no less powerful an impact. All theaters have in their repertoires plays on historical themes, and the number of these works continues to grow.

In order the embody the lives of our ancestors on stage, great meaning is held by historically correct presentation of the image of the person, the external material culture of the people, familiarity with their ways of life, their customs, their habits and tastes. As such, great is the role of historical costume, recreating the external appearance of a man, assisting with the lifelike truthfulness and artistic impression of their image.

This understanding of “theatrical costume” includes not only the dress, headwear, shoes, et.al. but also the external image of a man with accessories and attributes, and all other requisite props.

Costume imparts the living character of the image, and often even predetermines the demeanor of a character on stage. It immediately introduces the viewer to the environment surrounding a character, contributes to a better perception of the era, gives him the opportunity to feel the pulse of the past, and helps to reveal its content.

To date, there are no books or manuals in Soviet literature which would give the theater worker concrete directions on how to create Russian historical costume for the stage. Our work is an attempt to partially fill this gap. Without getting carried away with wide plans to give a comprehensive history of Russian clothing, this work summarizes the material as it applies to questions of the stage. Scientifically tested and verified, this material can serve as a guide for the creativity of directors, artists, actors and costumers.

The theater repertoire is the basis for the selection and systematization of the information, that is, works of modern and classical Russian drama written on subjects of Russian history of the pre-Petrine period. We have likewise taken into account well-known works of narrative fiction which could be staged.

For this material, complex and painstaking work was carried out to determine the appearance of personages, their clothing and necessary items needed to recreate the images of the heroes of the most popular historical literary and dramatic works. Information was taken into account about the historical personages which could serve as prototypes. Some of this information has been placed into the book, some into the captions for the illustrations.

From the graphical material, we primarily selected actual images of the historical personages shown in literary and dramatic works. During this selection, we took into account not only images contemporary to their lifetime, but also posthumous, obviously fantastical images, which are denoted as such which would serve to warn theater workers in their selection of traits for their heros.

When we were unable to find actual portraits of historical figures, we selected typical images of people of their time; this allows the ability to adhere to a chronological framework for the selection of clothing, hairstyles, weapons, etc.

The book is divided into two parts: one historical-theoretical and one practical. The first part is illustrated with actual portraits and drawings and, where possible, contemporaneous events, as well as works of historical painting, giving us samples of various interpretations of medieval Russian clothing by artists. The second part serves as a practical guide for the creation of Russian historical costume. At the end of the book is a bibliography, as well as a guide to names and a dictionary of terms.

I am immensely thankful to the institutions, as represented by their employees, which have given me assistance through their council, namely: the State Historical Museum, the State Tretyakovskaya Gallery, the V.I. Lenin State Historical Library, the A.A. Bakhrushin State Theatrical Museum, the State Literary Museum, the Museum of the Bolshoy Theater, the Museum of the Malyj Theater, the Museum of the Moscow Theater of the Arts, the Leningrad Theatrical Museum, the State Theatrical Library, the All-Russian Theatrical Society, and the State Institute for the Theatrical Arts. I would like to especially thank L.I. Yakunina, N.I. Sobolev, G.V. Zhidkov, N.E. Mneva, L.I. Zheverzheev, V.A. Maslikha, N.D. Telesheva, E.P. Aslanova, E.S. Krechetova, E.N. Chebotarevskaya, N.A. Popov, Ju.A. Bakhrushin, and the artistic costumers N.P. Lamanova, L.N. Vorob’eva, D.N. Larskij and V.N. Shalik.

— January, 1945. N. Gilyarovskaya

Part I

Historical Study

When staging plays of a historical nature, the artists and costumers play a responsible role. Stage costume should reflect the particularities of the depicted period. Therefore, it is advisable to start a work on the history of medieval Russian costume with the main milestones in the development of medieval Rus’.

Without going deep into the distant past, let us focus on the more well-known 9th century. At this time, the eastern Slavs had their villages primarily along the water route “from the Varangians to the Greeks,” serving as a road between the Baltic and the Black Sea along the Neva, Volkov, Lovat’ and Dnieper Rivers. Along this water route stood the ancient Slavic cities: Ladoga, Novgorod, Smolensk, Kiev, et.al., supporting a lively trade with both the Scandinavian countries to the north and the Greek cities to the south. The very fact that these cities existed in the 8th-9th centuries shows that the eastern Slavs had by this time managed to evolve culturally and economically. It is possible to assert that the Varangians, having appeared in Europe in part in Rus’ in the 9th century, were culturally significantly less evolved than the Slavs; this can be seen in how the Varangian princes and their warriors quickly adapted the Slavic language and customs. In turn, the Slavs very early on, around the 6th century, began to be influenced by the more cultured Greeks, with whom they had constant relations, more often peaceful than hostile. Relations with Byzantium (the ancient name for the capital of the Greek empire, Constantinople) became extremely close when, in the mid-9th century, Rus’ began to adopt Christianity and in particular when the Kievan Prince Vladimir made Christianity the state religion. This event, which reinforced the attention of the more cultured Greeks upon the Slavs, occurred in 988. Vladimir, hero of epics and tales, was a powerful prince, standing at the head of a people and a powerful force before which even Byzantium trembled. Just as mighty were his closest successors, with whom foreign leaders sought close relations. Yaroslav, son of Vladimir, married off his daughters, one to the Norwegian King Harald, one to the Hungarian King Andrej, and a third to the French King Henry I, and one of his sons was wedded to the daughter of the Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachos.

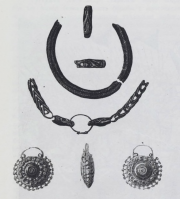

All kinds of goods flowed from Byzantium to Rus’, which the Slavs exchanged for furs, wax, honey, and finally, slaves. The prince, receiving tribute of various goods from his subordinate tribes, was likewise interested in carrying out trade in Byzantium, the prime market for the sale of goods. The prince and his druzhina[8]jeb: The prince’s household or army., which participated in all of the prince’s activities, both trade and war, could boast before foreign ambassadors of their accumulated wealth, consisting of expensive fabric, gold and silver items, etc. The ambiance of the prince’s palace was reminiscent of Byzantium. Their clothing copied that of Byzantium, as we can see in an ancient image depicting Prince Svyatoslav and his family where, however, the Byzantine mode was mixed with medieval Russian customs (the grivna[9]jeb: See illustration 5.). The members of the druzhina imitated their prince in their clothing.

Trade relations with Byzantium, however, suffered great difficulties. The southern Russian steppes, with their fat pastures, had attracted nomads since ancient times. The Pechenegs tried to intercept merchant ships on route to or from Byzantium. Under Prince Vladimir, the Pechenegs advanced nearly to Kiev itself.

Following the Pechenegs there came a more numerous and dangerous enemy – the Polovtsy. As long as the Kievan state was cohesive and unified, it had at its disposition great material and personnel resources, and the enemy forces were unable to prevail.

But, the Kievan state, as with all feudal states, was short-lived. Within it arose the forces which in the end dismembered and weakened it. This was feudal nobility, mastering large expanses of land, subjugating the population and turning them into vast possessions of their sovereign. The power of the state during the period of Kievan rule needed the help of the nobility, helping it to gain strength, and thereby created a force dangerous to itself.

By the 11th century, this tendency for the nobility to seize power for itself had already become visible. In Novgorod, the boyars fully achieved this goal. In the 1130s, Novgorod became a boyar republic and isolated itself from the rest of Rus’. At the same time in the Galician-Volynian lands there was a fierce, on-again-off-again battle between the boyars and the prince, which adversely affected the population of the villages and cities. In the lands of Vladimir-Suzdal’, the same battle ended with the cities united under princely rule and the defeat of the boyars. Nowhere else in the shattered lands of Rus’ did the prince hold as much meaning and power as here, in north-eastern Rus’.

Parallel to this strengthening of landed nobility, there arose new cities, some of which turned to the major economic centers which led the various segments of Rus’. Each of them would choose their own prince. They were all of a single house (the Rjurikovichi), but, as the author of the “Lay of Igor’s Campaign” stated: “rozne sja im xoboty pashut, kopia pogot,” which in a somewhat freeform translation says something like:

Yes, the times have come! To divide their banners

The Princes Rjurik and David did decide.

The banner of Vladimirov howled, and its enemies trembled,

But now that banner has been split.

The grinding interests of individual principalities forced their princes to become embroiled in local politics. Minor issues became major, and they ignored what was truly important.

A period of senseless wars between individual feudal leaders began, national hardships intensified, and Rus’ weakened. The Polovtsy began to triumph.

The battle against them demanded effort from all forces, and was not always successful. One of the most unfortunate undertakings was the 1185 campaign by northern prince Igor’ Svyatoslavich, which served as the theme of the poetic and patriotic work known as the “Lay of Igor’s Campaign.”

The appearance of the “Lay of Igor’s Campaign” speaks to a high level of culture of the warriors amongst whom this work was born, and about the refinement of their tastes. The political fragmentation of Rus’ and the difficulty of maintaining their ancient relations with Byzantium is reflected in their clothing: heavy Byzantine fabrics were replaced by lighter fabric of local manufacture or imported from western or south-western nations. For this reason, for example, Prince Igor’ was unable to imagine himself in the same luxurious clothing as was worn by old Prince Vladimir.

The continual excursions into the steppe and warfare against mounted enemies demanded large cavalry units, which gained prevailing importance. The western European sword, poorly suited for equestrian activities, was replaced by the lighter saber; chainmail, as with the enemy, was the main kind of protective armor. The Russian soldier, in warfare against the eastern steppe-dwellers, developed a particular system of armament and warfare tactics.

During this period of greatest isolation of the princedoms and of strain from internecine warfare, a black cloud hung over Rus’. Rus’ fell victim to one of the largest events in the history of mankind, the victory of the Mongol hordes over half of Asia and Europe and the formation of a world power by Ghengis Khan. The heroic battle of individual parts of Rus’ against the Mongols glorified Russian weaponry, gave birth to images of unparalleled fearlessness, but did not give the desired results. Rus’ was already unable to rally all its forces against its enemies. From 1237 to 1240, the Tatars ravaged almost all of Rus’ and subdued the Russian princes to their power. The Tatars left the existing systems intact, but imposed heavy taxes on the people. Having received this blow from the Tatar horde, and cut off from western Europe, Rus’ stopped for a long time in its economic and cultural development. Humiliated and weakened, she lost her meaning in the family of nations and appeared to be easy prey in the eyes of her western neighbors. Into the Russian lands advanced the Swedes from the north-west, and from the West, the Livonian Knights, who founded their state on the lower reaches of the western Dvina. Aleksandr Nevskij, however, taught both them and others a great lesson. With a relatively small army, he met the Swedes on the River Neva and smashed them completely. It was from this battle that he earned the nickname “Nevskij”. He also freed Pskov; the Livonian Knights, fettered by their armor, were defeated. This was the famous “Battle on the Ice” in 1242.

Aleksandr strove to live peacefully with the Tatars, as he saw the hopelessness of war against the numerous and well organized Tatar host; but, his successful actions against his western neighbors could not help but inspire thoughts that even the Tatar force could not stand against the united forces of all the Russian lands. A united Rus’ – this was what general aspirations strove toward. Moscow seized upon executing this task.

In 1147, when the Chronicles first mention it, Moscow was a small city, occupying only a small part of today’s Kremlin. During the time of the Tatar invasion, Moscow also fell to ruin, but resurrected, it began to grow quickly. In the eastern part of the area between the Oka and Volga there appeared many new cities, and Vladimir-on-the-Klyazma became the capital of the Grand Prince. The western part of this area was poorly settled, as it teemed with thick forests and vast swamps. It was inherited by a younger son of Aleksandr Nevskij, Prince Daniil, founder of the dynasty of Muscovite princes. The main forces of the Tatars, naturally, headed to the richer princedoms, and the princedom of Vladimir was completely destroyed, but the Tatars checked in on Moscow rarely; when they did appear, the population easily hid in reliable places among the forests and swamps.

Moscow was advanced by its advantageous geographical location on several trade routes. Skillful politics by the Muscovite princes facilitated the transfer of the center of political life from Vladimir to Moscow. Moscow quickly and successfully continued to grow.

Grand Prince Dmitrij Ivanovich, grandson of Ivan Kalita, having successfully united a significant portion of the lands around Moscow, was already so powerful that he decided to test his strength against that of the Tatars. On the shores of the Don, on the Field of Kulikovo, in 1380 the Russian army met Mamaj’s hordes. Thanks to the inspiration which embraced the Russian soldiers in battle against their subjugators, and thanks to his successful leadership, the Russian forces seized victory, and the defeated Mamaj retreated to the capital of the Golden Horde, the city of Saraj. For this battle, Prince Dmitrij received the nickname “Donskoj.” But, this victory at Kulikovo did not yet give complete freedom from the Tatar yoke, as not all of Rus’ was united: the princes of Ryazan’ were still on the side of the Tatars against Moscow, and Mamaj had a powerful ally in the person of Władysław II Jagiełło, who stood at the head of a united Poland and Lithuania. The Russians, however, were convinced that the Tatars could be beaten, and the Tatars themselves began to fear the power of Rus’, and confined themselves for the time being to collecting their annual tribute.

100 years passed after the Battle of Kulikovo, and a newly united Rus’ refused to pay its tribute to the Tatars. All dependence on them was destroyed. Grand Prince Ivan III, great-grandson of Dmitrij Donskoj, could already call himself leader “of all Rus’.” Connected to Moscow with all its vast lands was the wealthy city of Novgorod, which carried on a lively trade with western governments. The princes of Tver’ finally recognized the power of Moscow. The shadow of independence was held only by certain princes of Ryazan’ and the free city of Pskov, and even they recognized Ivan III’s son, Vasilij III. The princes of the lands united under Moscow entered the service of the Muscovite prince and became his subjects. Having married Sof’ya Palaeologus, a Byzantine princess, Ivan III considered himself the heir to the Byzantine emperors, adopted Byzantine ceremony at court, appearing before the people only in luxurious brocade vestments. He was an autocrat with unlimited power over his subjects.

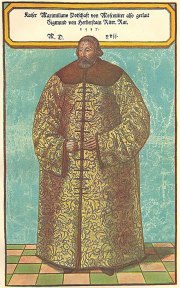

The period of the Tatar yoke and the growth of Moscow was one of estrangement of Rus’ from the foreign governments and cultures. All of the people’s power was focused on warfare against the enslavers, first secretly and then openly. The entire atmosphere of Russian life was composed distinctively, with very weak influence from the Tatars, mainly affecting military affairs. Gradually, there developed a costume which was significantly different from that which was in use in Kievan Rus’. Due to the stagnation of public life under the Tatars and under the influence of severe, climatic conditions, the cut of clothing was adapted to stillness and solidity, rather than freedom of motion. Long, heavy shuby [fur coats], long caftans, and long hanging sleeves completely took shape during the time of Ivan III and lasted until Peter the Great.[10]jeb: Peter the Great was tsar from 1682-1725. The character of this costume can be precisely established via the drawing of Baron Herberstein, who visited Moscow as the ambassador from Maximilian I to Vasilij III.

In parallel to this development of self-rule, the poorest classes were enslaved. In the Code of Law [sudebnik] published under Ivan III, there is an article allowing a peasant to leave the landowner for whom he worked only at the end of field work, around St. George’s Day in the autumn.[11]jeb: 26 November. This limitation was one of the stages in transition to full enslavement which gradually swept up all of the peasants living on the lands of the nobles, monasteries, et.al. It was characteristic for peasants to begin to be called “orphans,” as if underlining their difficult position. But even the landowners did not always agree. Wealthy boyars would entice peasants to their lands when they had the right of passage, leaving many landholders without workers, which was a sensitive matter for small landholders, as landowners lived and equipped themselves for compulsory military service only at the expense of income from their lands. Between the large and small landowners, this was a never-ending outlandish battle.

The position of the boyars was more difficult. The majority were descendants of local princes. They were unable to forget that their predecessors had been sovereigns. Having gathered in Moscow, they attempted to force the Grand Prince to share the state authority with them, but they met energetic resistance from Ivan III, his son Vasilij III, and especially from his grandson, Ivan IV “The Terrible”. Ivan the Terrible, having taken the title of Tsar, managed to elevate the authority of the state to unprecedented heights, and thereby contributed to the creation of a vast national, and later multinational, state.

As it strengthened, the Muscovite government grew ever stronger in international relations. Western powers sought out unions with Moscow in order to jointly repulse the impending influence of the Turks: in 1453, the Turks invaded Constantinople and flowed into the Balkan peninsula. It fell to Moscow to fight with those Muslim states which formed from the disintegration of the Golden Horde. The battle went successfully: under Ivan the Terrible, the khanates of Kazan’, Astrakhan and Siberia were conquered in succession. However, the battle with the Crimean Horde dragged on for 3 centuries. The Crimean Tatars continued their annual incursions into the Russian lands, ravaged the southern counties, and almost reached Moscow itself.

No less difficult was the battle against the united Lithuanian-Polish state, which had absorbed quite a bit of originally Russian lands.

With the demise of Tsar Fjodor, son of Ivan the Terrible, the dynasty of Ivan I Kalita came to an end on the throne of Moscow. A battle for the throne began. First to seize power was Boris Godunov, who persecuted the boyars no less than Ivan the Terrible. The boyars responded by supporting Dmitrij the Pretender, who leant heavily on assistance from the Poles and seized the Russian throne after the sudden death of Godunov. Once the Pretender was no longer needed, the boyars assassinated him and placed their own candidate on the throne: Vasilij Shujskij. The landholders and peasants moved against Shujskij, and he was overthrown. This internal unrest was complicated by the Poles, who seized the Moscow Kremlin, and by the Swedes, who seized Novgorod. The state was on the brink of doom, but the patriotism of the people and the exploits of such selfless individuals as Minin, Pozharskij, and the peasant Ivan Susanin saved the country from the foreigners. An army, gathered under the leadership of Pozharskij and Minin liberated Moscow from the Poles. In 1613, Mikhail Fedorovich from the boyar family of Romanov was elected to the throne.

In the 17th century, nearly 50 years were occupied with wars: with the Swedes over the shores of the Gulf of Finland, with the Poles over the ancient Russian territories, and with the Crimeans and Turks over the southern Russian steppes. Especially difficult was the battle against the Poles. The Zaporozhian Cossacks, formed primarily of peasants who fled from the estates of the Polish lords and the unbearable oppression of serfdom and rose up against those lords under the leadership of Bohdan Khmelnytsky. When they switched to being citizens of Moscow, after their first major successes and subsequent failures, a war started over the Ukraine which ended with the unification of left-bank Ukraine and Kiev on the right bank of the Dnepr with Russia.

The wars against the Swedes and Poles, with their well-armed and trained troops, forced Moscow to organize its military affairs along the same model. Military instructors were invited from abroad, who started to teach the Russian soldiers this new military system. When the Thirty-Years’ War ended in western Europe in 1648, many mercenaries who took part in it flooded into Russia in search of military fortunes and earnings. There was no lack of instructors. Thus, the noble irregular cavalry, the core of the Russian army, set aside its age and gave way to regular infantry and cavalry regiments, uniformly armed with cold steel and firearms. We can find information about the armaments of the Russian army in descriptions (with numerous illustrations) recorded by the Holstein-German Olearius and the Swede Palmquist who visited Moscow in the 17th century. Aside from the soldiers, there also arrived engineers, master artisans, doctors, pharmacists, etc. to serve Moscow. A special settlement was built on the Yauza River for these foreigners. Moscow gained the ability to export various goods (bread, furs, saltpetre, potash, etc.) abroad and to use the proceeds to purchase cannons, rifles, cloth, wine, et.al. In this way, lively relations between Moscow and western Europe were established.

This rapprochement with the West affected all aspects of Russian life, it is true, only among the more affluent sections of society. In boyar homes, luxurious furniture, carpets and dishes appeared. Under the guidance of foreigners, factories were built: silk, velvet (built by Tsarevna Sof’ya), cloth, ironworks, and more. The outfits of the landed class began to imitate that of the foreigners. A dress of a Polish cut was in fashion during the reign of Boris Godunov. Then Polish fashion was replaced by German. Aleksej Mikhajlovich, while his father Tsar Mikhail was still alive, had German caftans in his wardrobe. Young courtiers followed his example, but were met with resistance from zealots of the old customs, particularly the clergy. Tsar Fjodor Alekseevich openly stated his desire that the landed gentry and upper class wear shorter clothing. This revitalization of Russian life did not correspond to heavy fur coats and floor-length caftans. This is why it was so necessary for Peter I to have his people dress in shorter, more comfortable clothing.

In the court of Aleksej Mikhajlovich, theatrical performances were staged, which were considered by those of the old views to be sinful and “demonic.” At first, artists selected from the foreigners and worked under foreign directors, but then Russian artists and directors appeared as well. In the village of Preobrazhenskoe outside Moscow, a special theater was built. The spectators were the tsar and his family, boyars, and court nobles. However, the theater during the reign of Tsar Aleksej did not last long, and could have its cultural effect only upon the court, but its very existence had great meaning. The very fact that the tsar attended spectacles, and with the permission of his confessor, had to dispel the prejudice against theater spectacles: the path for the later establishment by Peter I of the public theater was cleared.

For artists of the court theater, particular costumes were needed. A few years passed, and Peter dressed his court jesters in a new kind of caftan, but after only a few years, comfortable and short costume entered into general use in both the upper and lower classes of society.

— S.K. Bogoyavlensky, Member-correspondent of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR

Russian Historical Costume in Pictorial Art and On the Stage

Theater decorative art, and theater costume in particular, are closely dependent on the general condition of art of its period. This also applies to so-called “historical” costume, reproducing either on stage or in a picture people of prior times.

When working on historical costume, we need not only historical knowledge, but also the creative ability to generate the artistic image. It’s not enough to dress the actor in the authentic dress of the historical person he is portraying. The actor should, above all, be imbued with the psychology of his hero, and should inhabit his dress and learn to walk and move as people did in the time that he depicts — in a word, before he steps out onto the stage, he should produce a genuine scientific historical study, if he does not wish to be simply “in costume.”

This study of materials and embodiment by the actor of the desired historical image is particularly difficult when the matter involves people from distant times, whose culture was different from our own.

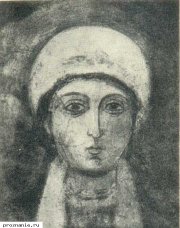

Little is known about the appearance of these people, about their manners and customs, and familiarity with them is primarily possible only through monuments of medieval art, which are often poorly preserved and almost always present man and his surroundings through the tastes and customs of their own time. In order not to fall into rough stylization or a purely external imitation of the manner of that ancient art, it is necessary to grasp the rules according to which, for example, medieval Russian icons or fresco were painted. It is then necessary to create a thin demarcation between the a man of that age and how he may have actually been, and his appearance in works of art according to the aesthetic canon of his time. For example, the excellent portrait of St. Demetrius of Thessaloniki [Illustration 69] which, according to tradition, depicts the Great Throne of Prince Dmitrij of Vsevolod, can be interpreted as bearing similarities to the original person, and yet also bears imprints of Byzantine religious art.

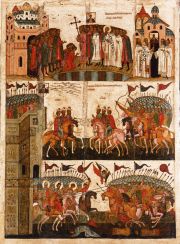

It is likewise obvious that the two young boys in the icon of the “Praying Novgorodians” [Illustration 11] stand in unrealistic, conventional poses, and that no living person could look like the rider depicted in the center of the painting of the “Church Militant”[12]jeb: You can see an image of this icon online here., where Ivan the Terrible and his entire army are clothed in idealized outfits of a type traditional for Byzantine icons, without any real life elements.

This occurred not because of an inability or lack of desire to create a realistic depiction of man, but to a large part due to completely other motivations. For example, in one resolution of the Stoglavy Synod held in Moscow by Ivan the Terrible in 1551, it states that “proud icon painters and their students were to paint from ancient images, and would not use their independence and conjectures to depict the Almighty.” Otherwise, artists would face serious punishment for any deviation from tradition determined to be sacrilegious.

The Novgorodian youths, just like the remaining praying Novgorodians [Illustration 11], are completely bent forward in pious emotion, although in reality, they would, of course, had their own different poses and would have moved more naturally. We notice, however, that in this painting, the artist has dressed the Novgorodians, as opposed to the angels and saints, in very realistic, modern clothing, which can do much to help clarify past life.

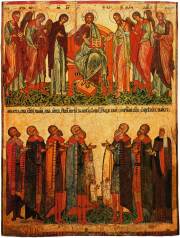

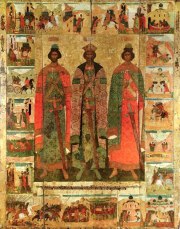

A great amount of material toward the evolution of medieval Russian costume is found in icons depicting the princes Boris and Gleb, which the church considered to be saints. On a 13th-14th century icon from Novgorod [Illustration 72], Boris and Gleb, in both their poses and their clothing, show strong influences from Kievan tradition. Boris’s dark blue korzno and cinnabar caftan and Gleb’s scarlet korzno and purple caftan, with their ornamentation and overall appearance, belong to a Byzantine style of clothing. On their heads, they wear smallish Grand Prince caps of the Kievan period, decorated with fur.

Boris and Gleb look completely different on another Novgorod icon from a bit later, although still from the late 14th century [Illustration 76]. These figures have no solemn or Byzantine characteristics. Boris and Gleb stand quite simply, and are dressed completely differently: over a caftan with a large pattern, Boris wears a special robe, which is less like a korzno than an everyday Novgorod shuba with turned down collars and lapels, similar to what we see on the “Praying Novgorodians” icon. Instead of the traditional korzno, Gleb wears a common shuba with long sleeves and turned down collars, of a slightly different fashion. Their belts, as appears to have then been in fashion, sit low, and on their heads they wear the everyday princely caps, which seem to have somewhat lost their ancient form.

On a 15th century icon [Illustration 83], Boris and Gleb are once again stylized in Byzantine fashion. Their poses are regal, but as if the korzno were no longer in use and its form had been forgotten, and yet tradition required it, Gleb wears a particular kind of cape, covering his right hand; moreover, this cape with its collar and simple details is more reminiscent of a shuba than the korzno which it should represent. Boris wears an actual shuba. The brothers wear tiny Novgorod-style princely caps, barely hanging on to the tops of their heads, similar to those we see on the generals in the icon “The Battle between Novgorod and Suzdal'” [Illustration 10]. Their belts once again sit at the waist. It is difficult to say whether everyday fashion had changed, or if this is a return to earlier iconographic traditions of depicting Boris and Gleb.

Muscovite icon painters of Ivan the Terrible’s time present Boris and Gleb in a new guise [Illustration 88], once again approaching Byzantine tradition. The elongated figures stand in solemn poses, straight, with beautiful faces, dressed in expensive, golden shuby with long sleeves. Between them, strong and beautiful and in the same kind of shuba but with a large, turned down collar stands the grey-haired Prince Vladimir in a crown reminiscent of an overturned sunflower.

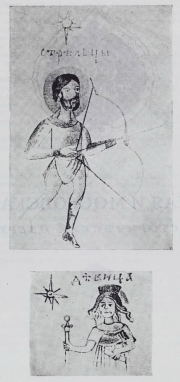

Russian icon painters and illuminators depicted saints, Biblical kings, and even Russian and foreign leaders in such crowns, sometimes with longer petals. These crowns served as a symbol, as an attribute of saintliness or power.

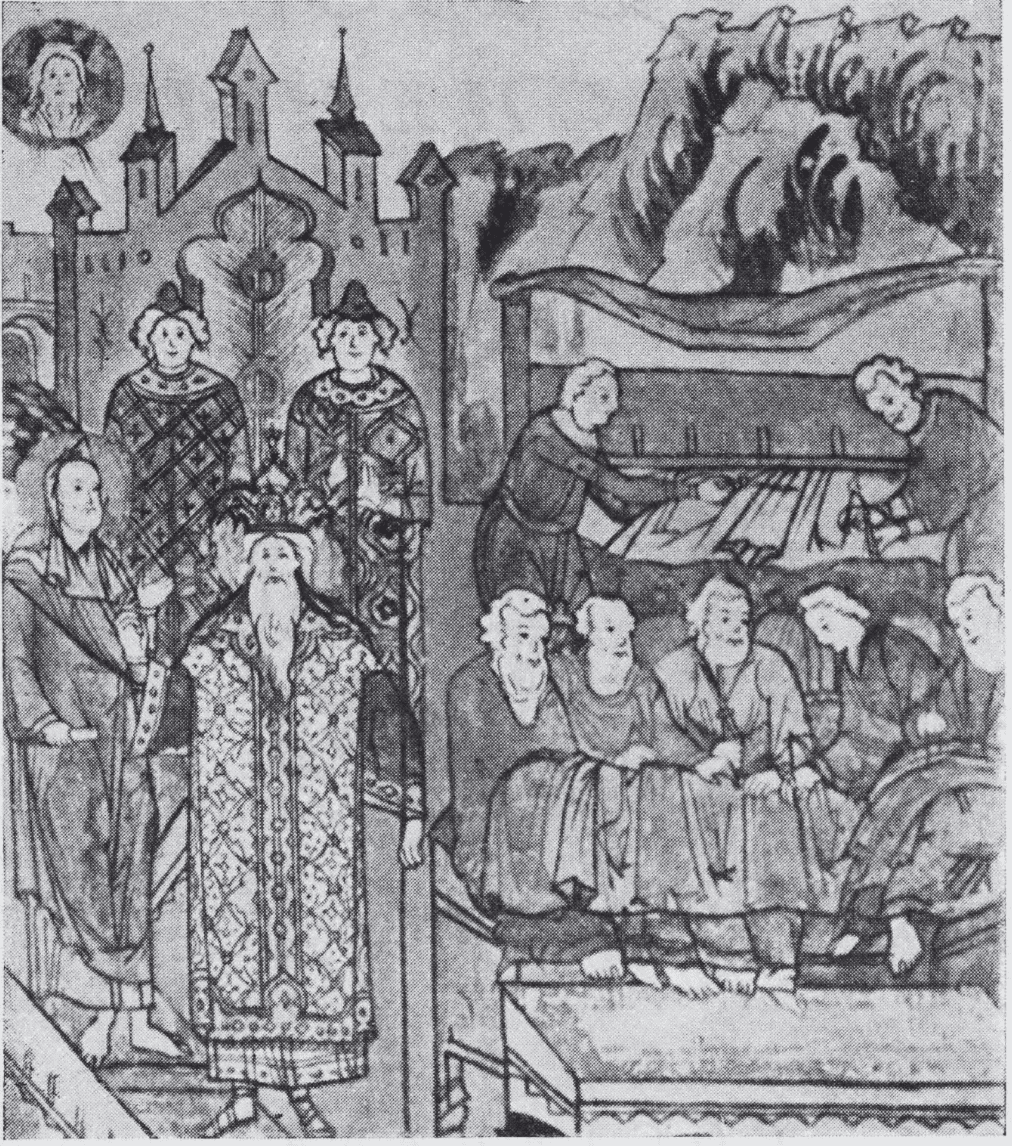

A similar crown, but with small spheres atop the ends of the elongated leaves, is worn by Ivan the Terrible in the illumination “The Coronation of Ivan IV”[13]jeb: See an image of this illumination here online.. A similar crown is seen on both him and his wife in the illumination “The Farewell from His Spouse” (before the Kazan’ campaign). Similar headwear is also seen on his mother Elena Glinskaya and on the Tsaritsa Fat’ma on a miniature depicting “The Reception of the Grand Duchess, Wife of Shighali” in 1535. A similar type of crown also decorates the head of the Tsar’ in the illumination “The Manufacture of Clothing” [Illustration 1].

Generally speaking, in Russian art of the 16th and 17th centuries, we often encounter elements of everyday life alongside conventional canons of iconography. This is clearly seen in the family icon of the Godunovs [Illustration 92], where Boris, Gleb, the skhimnitsa Ksenia and Saint Feodot are dressed in everyday worldly and spiritual outfits, while Mary Magdalene’s outfit is of a iconographic character, and Theodore Stratelates is depicted as a Byzantine warrior, such as in Muscovite Rus’ would have been seen only in icons.

A lot of valuable material for the study of everyday clothing can be found in the huge compositions located in every church, notably those of the “Last Judgement” which were painted in church vestibules on the right hand side of the entrance. In these multi-figure paintings, to the right of the judge stand the saints and the righteous, and to the left stand the sinners. The righteous and saints are always depicted in traditional clothing of the iconographic type, but on the left, amongst the sinners, it is possible to find a multitude of figures in simple everyday outfits.

In a 16th century icon of the “Last Judgement” in the Tretyakovskaya Gallery[14]jeb: You can see an image of this icon online here., amongst the sinners there are several figures depicting western leaders, dressed in modern outfits.

In addition, important guidelines for the clothing of the clergy can be found on the right side of this icon – a row of elders in monastic vestments, depicted in the form of flying angels with wings, numbered amongst the angelic host for their selfless lives. These depictions clearly show that in medieval Rus’, the clergy and even monks wore bright colors: light blue, yellow, brown, reddish-brown, not only black; moreover, the crosses and symbols on these outfits, which are quite precisely depicted, were not only white, but also red [Illustration 89], as continued amongst the Old Believers almost until modern day. From this, we can see that the gloomy figure of the hermit in black with large white crosses of Calvary which typically appears on stage, for example in “Boris Godunov,” does not at all match historical fact.

There is much interest in the study of so-called “illustrated books” [litsevye knigi], that is, illustrated medieval manuscripts, collections [izborniki], chronicles, and so forth. Information copied from other, older books is presented alongside descriptions of modern events. Amongst traditionally conventional depictions of people and their surroundings, we also find purely everyday features.

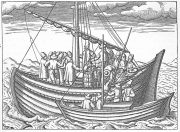

Frequently in these books, we can find a layering of multiple centuries. Is is necessary to separate these strata in order to find the true core, as the scribes of various times introduced their own tastes and the tastes of their eras into both the narration and images of these works. Such, for example, are the drawings from the famous Köningsberg Chronicle [Illustrations 81 and 82], which were preserved via the touch-ups and updates by artists of later centuries, but at the core of which lie drawings that are contemporary to the author of the work, illuminating the time of Igor Svyatoslavovich’s campaigns. Of particular interest are the depictions of covered carts and soldiers sailing in small boats of a particular type, in that both forms of ancient transport are shown quite clearly, as are the soldiers’ clothing and weapons: swords, bows and spears.

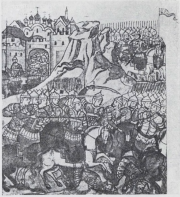

The depictions in the miniatures of the 16th century “Battle with the Golden Horde” [Illustration 84] from a manuscript of The Life of St. Sergius is even more conventional. The Muscovite troops stream out of a completely everyday Russian city and go around an archetypal rock, the type of which was often painted on ancient icons and which would never have existed outside of Moscow. The soldiers’ outfits and armor are of an iconographic type. However, they hold not swords, but curved western sabers. One of the generals coming out of the gate wears a typical Grand Princely cap, while a second (possibly the Khan of the Horde) wears a crown with prongs, similar to the leaves of a sunflower.

The miniatures from the 16th-century so-called “Godunov Psalter” have played a large role in the study of medieval Russian daily life, where, alongside completely stylized depictions, we also find details of the everyday, for example, the drawing of the horse with a beautifully drawn tall saddle, the scene of the archers shooting from the fortress tower (which, itself, is quite conventional), the soldiers’ weapons, their swords, helms with chainmail skirts, etc. [Illustration 90]

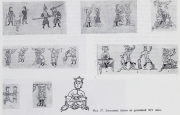

It is particularly difficult to study the clothing of the lower class, as they are depicted relatively infrequently. They are found amongst small marginalia (for example, the sleeping digger[15]jeb: See illustration 70., in capital letters (fishermen, soldiers standing guard, gusli players)[16]jeb: See illustrations 73, 77, 78., amongst various figures on an icon, or in the so-called “saints’ lives,” that is, amongst a small group of scenes depicting selected events from the lives of a saint: his birth, death, miracles, etc.

Many details about everyday life can be found in illuminated capitals in medieval books and manuscripts. Capitals of the Kievan period are of a purely ornamental character; thematically, they are drawn from the worlds of hunting and vegetation. In the 14th century, amongst the decorated initial letters, we start to find the first human faces, then the letters themselves transform into completely human figures: hunters, fishermen with nets, skomorokhi, gusli players, soldiers, et.al. in the form of realistic and lifelike drawings [Illustration 77]. The 16th century brings about a stylization of these motifs of fishermen and hunters, birds and dogs, which transform into perfect monsters [Illustration 78], but at the same time, alongside these freakish drawings, in other manuscripts we find very clear, strong, purely graphical letters. In the 17th century, among these decorative letters of an ornamental character, we find very realistically drawn figures – a hunter, a boy with a horn, etc. [Illustration 80].

Everyday details are also seen in the images of the builders of churches, donors, clients ordering icons and manuscripts, on frescoes, and in the icons and manuscripts themselves. Thus we see depicted the family of Prince Svyatoslav, the large family of Prince Yaroslav the Wise with his wife and daughters, Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich, the praying Novgorodians, a praying city dweller, the merchants Stroganov, and so forth [Illustrations 3, 4, 8, 11, 23, 91].

Occasionally we even find the figure of the artisan himself who created the artwork. To this end, in particular we note a unique sculpture, a relief figure of the stone-work master Avraamij, with all the attributes of its creation on the Korsunskij or Magdeburgskij gates of Novgorod’s St. Sophia cathedral [Illustration 74]. The gates themselves date to the 17th century, but the figure of Avraamij is from the 14th century. It was created analogous to three other figures of foreign master artisans.

Sometimes the most important details are found in the most random documents, for example in the “Petition” of Clerk Grigorij Vspolokhov, given by him to Tsar’ Aleksej Mikhajlovich on the occasion of the birth of Tsarevich Pjotr [Illustration 96, 97]. This precisely dated document is a fourteen-meter-long scroll with illustrations. In it, the author, a high-ranking official who was imprisoned for some reason, asks the tsar’ for mercy. In the scroll, there are five color illustrations. Here are the two most characteristic of them: in one, the petitioner in a long tunic and with a bare head and on bended knee extends his hands, bent in prayer, to the throne which soars in the clouds. A smashing sword falling from the throne deviates slightly from the head of the supplicant. On the other drawing, the tsar’s subjects congratulate him on the birth of the tsarevich. Here we see representatives of all layers of Muscovite Rus’ society presented in precise order, clothed in stately, festive clothing, and what is more, each stands in the picture precisely in the spot which they occupy in the hierarchy of that time. At the top, the tsar, holding a lily, receives the congratulations of the patriarch. Behind the tsar’ are the boyars; behind the patriarch stand the spiritual authorities. They all hold palm fronds in their hands, as if on Palm Sunday. The tsaritsa is shown below with the boyarinas, greeted by young women. All of the women hold lilies. Further down, the populace and merchants stand, holding palm fronds. Amongst them, there are six children. But, such documents with visual depictions of the everyday are few and far between.

Materials from the Kievan period are few in number and difficult to study. In Russia and abroad, in Novgorod or Pskov, the wealthy are depicted in monuments and literary sources. As for Moscow, starting in the middle of the 16th century, rich and diverse details can be gleaned from the so-called “stories of foreigners in Muscovy.” These are a series of relatively detailed and accurate descriptions of the Muscovite state, almost always accompanied by well-done drawings. Their authors were foreign travelers who visited Muscovy for various different purposes. Some arrived as part of diplomatic missions as ambassadors, such as Gerberstein, Olearius, Meyerberg, and others; in order to establish trade relations, such as Massa; or in order to commit espionage, such as Palmquist. A large number of foreigners served as hired troops for the Muscovy tsar (such as Margeret), and all kinds of artisans and specialists were continually arriving in Muscovy. Among the latter, various adventurers sometimes came, seeking their fortune in distant lands.

Communiques and diaries from the ambassadors, reports from trade missions, private memoirs — these all contained a multitude of important material about everyday life. Taking errors and inaccuracies into account which are inevitable given the authors’ unfamiliarity with everyday life in this new land, and by comparing them to Russian sources, it is possible to find a lot of valuable data.

Foreigners were not allowed to participate in the everyday lives of the population of Moscow. The inner life of Muscovite society was closed to them. This was especially difficult for diplomats, because arriving ambassadors were immediately isolated and surrounded by such high honor and splendor that they were only able to see that which was deemed necessary to show them. Therefore, when writing about customs and manners, they predominantly made use of stories of others, which were often biased.

Representatives of the merchant class, of course, were able to see much more, but they too, where possible, were separated from the population, as were artistic masters. Adventurists of all types were in a better position to study the population, but their stories often contain many prejudgments and fantasies. Therefore, when studying the valuable material given by these foreign sources, it always pays to keep in mind who their author was, the position he held in his own country, what he was doing in Muscovy, and for what reasons he wrote his memoirs.

Of particular interest for our study are the notes of a certain Hollander named Struys[17]jeb: Jan Janszoon Struys, 1630-1694, Dutch adventurer who wrote a book called “Three Travels” about his adventures. See here for more details.who at one time worked as a sailing master on the Volga. His world travels, his relatively extended time in Rus’, and his lower social standing all allowed him to become familiar with the everyday life of the Russian masses amongst whom he lived. Observant, bright, and possessed of undeniable literary talents, Struys saw with his own eyes that which the official ambassadors were unable.

Speaking of the people he met, he gives a description of their clothes, often with interesting everyday details, for example: “Narrow sleeves, several cubits in length, are pleated at the shoulder in order to free up the arms. Cut this way, it becomes convenient for cooks to pick up hot pots and pans, and their sleeves become untidy and dirty. Thieves and vagabonds place stones in the ends of these sleeves, in order to unexpectedly strike victims on the head.”

Of course, the question of elongated sleeves in medieval Russian costume is considerably difficult. In some situations, lowered sleeves indicated respect, in others, sadness. The adages “sleeves rolled up” (meaning “good”) and “sleeves let down” (meaning “bad”) have survived from that time. Such details, of course, could easily have escaped even the most attentive foreigner.

We recall Struys’s drawing depicting Stepan Razin[18]jeb: Stepan “Sten’ka” Razin was a Cossack leader who led a major uprising against the nobility and tsarist bureaucracy in southern Russia in 1670-1671. See here for more details. throwing the Persian princess into the Volga, an event which he describes as a eyewitness. It is impossible to know whether he personally saw this event, or if he retold a living legend from that time, because Struys speaks in his stories about a lot of events as if he were personally present, possibly in order to liven up his retelling. But in any event, that which he reports about Stepan Razin, his appearance and his way of carrying himself, must be considered when recreating his image. Struys’s drawing [Illustration 127] answers the controversial question of how to depict Stepan – with a beard or with only a mustache, as Surikov describes him, giving an amazingly powerfully expressive face of a typical Don Cossack. It is interesting that both surviving engraved portraits of Stepan Razin of foreign origin present completely different appearances. On one engraving, Razin in a hat and with a mustache appears quite similar to the image drawn by Struys; on the other, Razin is presented as a brutish, bearded man in a turban [Illustrations 128, 129]. Both engravings have the same German inscription: “Stenko Radzin, head of the rebels in Moscow, brutally executed 27 May 1671.”

When studying sources and using them for the stage, it is extremely important to turn one’s attention to the captions and the frames in which the images are presented, as these immediately point to the era of the portrait’s creation and often help to determine their origin. Often, these foreign sketches are quite fantastical, but the majority of these images were created in a realistic manner. Taking into account some errors which we note in the captions, they can serve as excellent material for the recreation of historical images.

The impressions of these travellers, sometimes seemingly insignificant, create complete pictures of past life and revive images of long-gone people in all their peculiarities. For example, one foreigner, describing the Pskov warriors riding out before a battle, writes that “their weapons shone brilliantly, and their helms burned like glass.” This brief note clearly produces a magnificent image of Pskov army marching out against the background of the sparkling white walls of Pskov, its snow-white churches and houses, surrounded by greenery, with bright, even “burning like glass” metallic scaled armor. This picture is unique and resembles neither the appearance of any medieval western European knightly militia known to us, nor that of the patterned color and brightness of the Muscovite army of the 17th century.

Tanner[19]jeb: Bernhard Leopold Franz Tanner, a Czech adventurer., who was in Muscovy in 1678, writes about this dress. A lesser servant of the Polish embassy who was embittered with his Polish masters, and at the same time dissatisfied with the Russians, about whom he tried to relay any bad thing he could find (or, quite possibly, imagine), he nevertheless could not help but be delighted by the beauty which he found in this land that was foreign to him. The first thing which struck him was the detachment of resident royal bodyguards which rode out to meet the embassy.

“The color of their long, red outfits was identical on each of them. They sat upright on white horses, and they had wings attached to their shoulders, rising above their heads and beautifully painted. In their hands, they held long pikes, at the ends of which were fastened gold dragons, twirling in the wind. The squad looked like an angelic legion.”

Tanner confesses that he does not have the words to describe a second group of courtiers which rushed to meet the embassy.

“The riders wore smart red half-caftans. They wore a second caftan, lined with sable and masterfully embroidered, thrown about their neck. They called these a feryaz’. On either side of each feryaz’, there were roses fashioned from large pearls, silver, and gold. They wore these folded back over the right shoulder and down the back. Their hats, sparkling with stones, silver and gold in the sun, gave even greater beauty to this procession of already smartly-dressed riders.”

This description of the embroidery corresponds to the wonderful patterns which decorated the clothing of Ambassador Potemkin [Illustration 59], from around the same time.

Furthermore, Tanner takes delight in describing the horses’ harnesses, rattling and jingling with chains of silver and gold, which make the horses “jump with their rattling.” Their horseshoes likewise rang from the chains and bells that were attached to them. The riders were agile and stately, they pranced before one another, and Tanner was struck by the prowess with which they leapt from tired horses to fresh ones.

The entire squad burned like fire in their bright finery.

In general, Tanner was struck not only by the brilliance and splendor, but also by the din which accompanied the cortege: more and more troops arrived in order to greet the ambassadors. They all “imperceptibly struck their horses, such that they would continually play and nicker…”

The shine, radiance, bright colors, gold, silver – all of these were characteristic for the court of Tsar’ Aleksej and Tsar’ Fjodor, who continued the tradition. Thus too were the buildings which were erected in cities and suburbs as residences for the tsars and boyars. The foreigner Reitenfelds, describing a palace in the village of Kolomensk built by Tsar’ Aleksej Mikhajlovich called “an eighth wonder of the world” by contemporaries, notes that it was so smart and shiny that “it seemed fresh out of the box.” We must not forget it was at this same time that the severe red and white walls of the Cathedral of St. Basil, built by Ivan the Terrible from brick and white stone, received its smart, multi-colored paint job.

All these details, comments, descriptions and observations by foreign “eyewitnesses” give us much data for the study of the appearance of people and of everyday life in pre-Petrine Russia. Documents and literary evidence written by Russians and various works of art and household items either disprove or complement what was described by these eyewitnesses. It is impossible to determine the level of sound and din that would have been created by the Russian riders and their bells and chains, but Tanner notes the pleasantness of their sound. These chains were divided into “jinglers” (povodnye) and “rattlers” (gremjachie). Jinglers were made up of a chain of rings, and hung between the bit and the front of the saddle bow in the form of reins; rattlers were made up of several rattles linked to one another. These were also attached to the saddle horn often would hang down further than the horse’s belly. The very arrangement of these chains was such that, it appears, Tanner did not exaggerate their musical role in the stately parade of these Muscovite riders. Tanner further describes the finery of the Faceted Chamber, the grandeur of the court and the richness of the royal vestments on the day that the Polish embassy was received and the celebration which he happened to witness.

We have two testimonies of this eventful day. One of them, the impression of an eyewitness, the aforementioned Tanner, and the second, an official record in the Russian palace book, the so-called Outings of the Sovereigns, Tsars and Grand Princes, which was kept at court every day and in which they recorded all of the tsar’s more or less official “excursions’ to church, to receptions, his trips on pilgrimage, and so forth. Each entry describes in detail what clothing and assorted items the tsar’ wore. The book provides very precious material in this area and with careful reading, sheds light on official life and the strict etiquette of the sumptuous court of the Russian tsars. It covers the reigns of Tsar’s Mikhail, Aleksej, and Fjodor Romanov. The chronicler faithfully records in it:

On the 10th of May, the Great Sovereign hosted in the Faceted Chamber the arrival of the great and plenipotentiary ambassadors of Jan Kazimir, king of Poland: Prince Michał Czartoryski, the governor of Vilnius Kazimierz Sapieha, and Hieronym Komar. And the Tsar wore the following: the cross of gold with diamonds, the cape with the image of the Savior, a baldric of gold with a buckle, barmy of Greek make, and a royal platno – on a ground of silver velvet, with vines of green (which were created this year for Holy Week), a waist-length caftan of silver fabric decorated with golden vines and pink silk [flowers?], with lace and the wrists decorated with pearls and stones, a zipun of white taffeta, and the crown with emeralds…

The tsar held the royal scepter, and the orb of state with a cross stood on a gilt silver platter near the window. The tsar’ was dressed in the Faceted Chamber, whence he came from his own chambers in his everyday clothes, namely “a voluminous golden ferjaz’ on a ground of yellow, green vines and silver embroidery with diamonds; a riding caftan with golden vines and rose silk, with gold embroidery and stones; a scarlet velvet hat decorated with a buckle and a diamond feather. He had an Indian staff with stones.”

This is the fact of the matter. At this reception, Tsar’ Fjodor was wearing a hat with an emerald of the second category, and a silver royal platno embroidered with golden embroidered vines. Whatever he wore beneath his platno was not visible, as all of the depictions we’re aware of always show the royal platno buttoned all the way to the floor.

Tanner, having seen Tsar’ Fjodor on the throne in all of his glory, described the young monarch thus:

“[His head] was decorated with a glistening hat, the top of which was gold crown, decorated with precious stones and various decorations, and in his hand was the royal scepter. The caftan (tunic), at which it was impossible to stare intently due to the excessive brilliance (I stood at a close distance), was so luxurious that later, as we returned to the embassy compound, all conversation was focused upon it. His outerwear (a paludamentum), which was thrown over his shoulder like a mantle, shone with diamonds and pearls such that they called the Muscovite tsar, decorated in this attire, a star taken from the heavens.”

In order to reconstruct the actual appearance of this youthful tsar’ (he was eighteen years old at the time), it is worth looking at one of his portraits in which he wears “the crown and barmy of Monomakh,” which seems to have been painted from life by a contemporary artist (possibly by Ivan Ievlev Saltanov, an Armenian artist who worked at that time in Moscow’s Kremlin Armory) [Illustration 54]. In this portrait, Tsar’ Fjodor Alekseevich is depicted as a saint, with a halo about his head and in full royal vestments. He wears a golden, patterned platno, with a scepter in his right hand, and the Orb of State in his left. What Tanner calls a “tunic,” that is, a caftan, and what “outer wear” he might have worn thrown over his shoulder like a mantle is difficult to determine. Here we see perhaps an inaccuracy, well-known presentation bias by which, according to the western model, he was unable to imagine a monarch without a mantle. Of course, this is mere conjecture, but these inaccuracies do not lessen the impression of “eye-witness.” Nevertheless, it is necessary to approach the descriptions and stories not only of foreigners, but Russian portraits, with great caution.

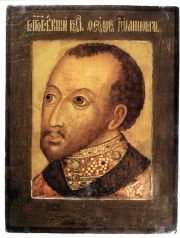

Russian iconographic portraits, or so-called parsuny, are also unreliable, especially when they first appeared at the turn of the 16th-17th centuries. Take, for example, the parsuna of Tsar’ Fjodor Ioannovich [Illustration 26]. This portrait presents, from our point of view, a distorted face; yet at the same time, if we are to believe Struys’s account, the elongated chin and long ears we see in this portrait were highly prized among Russians in the 16th century. Likewise beastly is the image of Prince Mikhail Skopin-Shujskij [Illustration 39], famed for his good looks and valor; this parsuna, like that of Tsar’ Fjodor, was placed on his funeral monument. In general, work based on medieval portraits requires a great deal of caution.

We turn now to Boris Godunov, one of the central figures of our historical repertoire. We reviewed four posthumous portraits (there are no portraits from during his lifetime), and picked out two of them. In one, Boris is presented as part of a series of Russian tsars, with the appropriate splendor typical for such images [Illustration 28]. The other, where he is depicted without a beard and with only a mustache, is a later portrait which emphasizes Boris’s Tatar origins [Illustration 27]. There is unreliable evidence that Boris once shaved off his beard, which allegedly provoked great outrage from his contemporaries. We are not presenting the other two images: the first from a suite by Stenglin[20]jeb: Johann Stenglin (1710-1776), German printmaker. from the 18th century, which is obviously not authentic and furthermore presents an expressive image;[21]jeb: This image can be seen online here: http://www.russianprints.ru/files/1274_350.jpg the second is a completely fantastic image of Boris with a completely shaved beard and in a boyar hat, also clearly not contemporaneous, as tall boyar hats appeared later.

We likewise reviewed portraits of the False Dimitrij.[22]jeb: Dmitrij I claimed to be the youngest son of Ivan the Terrible, having escaped an assassination attempt in 1591. Supported by the Poles and Cossacks, he led an uprising against Boris Godunov and was crowned tsar’ in 1605. In 1606, he was deposed and executed by an uprising of boyars led by Prince Vasilij Shujskij. We present here a well-known portrait from Vishnevetskij Palace, now in the Moscow Historical Museum [Illustration 30], and an accompanying portrait of Marina[23]jeb: Marina Mniszech, the Polish noblewoman who married the False Dmitrij I in 1621. Her refusal to convert to the Orthodox faith after her wedding was a primary factor in the subsequent boyar uprising which led to her husband’s deposition and death. She returned to Poland, but returned to Russia and married another pretender to the throne, False Dmitrij II. After a bid to nominate her son Ivan to the throne, she was later captured, and died in prison (strangled, according to some sources) in 1614. in a Polish dress [Illustration 35]. We also present their depiction from a contemporary brochure by Grokhovskij, published in 1606 on the event of their betrothal in Krakow on 24 Nov 1605, at which the absent groom was represented by the Muscovite ambassador Afanasij Vlas’ev-Bezobrazov [Illustration 31].

In Grokhovskij’s brochure, in the portrait from Vishnevetskij Palace, and also in a foreign engraving depicting Dmitrij in the Cap of Monomakh [Illustration 34], there is obviously a great similarity of portraiture. Aside from these portraits, however, there are also some obviously fantastical depictions. We know of two such portraits, from which we present one, pointing to its unreliability [Illustration 32]. Similar unreliable portraits of historical figures are quite common, and in the majority, they are clothed in the most inaccurate clothing which completely do not attest to their individual quality or their position in society and time. As such, the 16th and 17th centuries present a lot of material, both authentic and inauthentic, of both Russian and foreign origin. For all their inaccuracies, however, a few graphical depictions by foreigners of this time have a real character which raises their value as historical sources.

A large amount of material, which has so far been little studied, can be found in Russian sources of the most diverse character, which as shown above, present particular interest through juxtaposition against foreign witnesses. In the captions under portraits of Russian statesmen, we have attempted to summarize the various descriptions of their appearance from surviving historical sources. These include some interesting disagreements (see, for example, the captions for the portraits of Boris Godunov and the False Dmitrij, Illustrations 28 and 30). The inconsistency of these descriptions and recollections by contemporaries make the recreation of these historical figures’ likenesses for the stage difficult, as well as for all other forms of pictorial art.

We find a particularly large amount of detail about everyday life in memoirs and documents of the Time of Troubles.[24]jeb: The interregnum between the death of Tsar Fjodor I in 1598, last of the House of Rjurik, and the ascension of Mikhail I Fjodorovich, first tsar of the House of Romanov, in 1613. The period was marked by civil strife, pretenders to the throne, and invasions by foreign armies, as well as a famine in 1601-1603 in which approximately 1/3 of the population of Russia died of starvation. In them, we find detailed descriptions of the appearances of the False Dmitry I, Marina Mniszech, their solemn processions, feasts, costumes, the uniforms of their guards, their Russian and Polish entourages — in a word, everything about the peculiarities of this short-lived but turbulent reign. Along the way, the authors of these memoirs touch on a number of Russian everyday features and often describe Russian outfits which seemed strange to them.

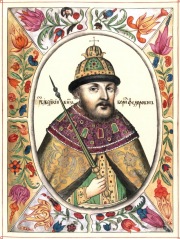

Artistically exceptional paintings, icons and portraits were produced by the royal artisans of the Kremlin Armory, where alongside conventional compositions, they also created realistic depictions. Thus, for example, were the portraits of the tsars in a unique manuscript, the “Tsar’s Titulary”, also referred to as “The Great Book of State, or the Source of Russian Sovereigns,” created by order of Tsar’ Aleksej Mikhajlovich in 1672-1673. The portrait of Aleksej Mikhajlovich himself, apparently, was painted from life. It is possible that the artisans had access to no-longer extant images of Ivan the Terrible, Vasilij Shujskij, Filaret,[25]jeb: Fjodor Nikitich Romanov, later Filaret Patriarch of Muscovy and of All Russia, political and religious leader during the Time of Troubles and following years, and father of the first Romanov tsar. and Tsar’ Mikhail Fjodorovich[26]jeb: 1596-1645, elected in 1613 to become the first tsar’ of the Romanov line, ending the Time of Troubles., as each of these portraits in the Titulary presents an image of a living person, each with its own unique internal or external details, and yet all presenting a generally attractive appearance [Illustrations 25, 28, 38, 40, 41, 51]. Around each of the portraits are illuminated ornamental frames of every possible color, and it is amazing that although there is a singularity of composition, the design on each is unique and asymmetrical, such that no one color or drawing is repeated. The bright colors, preserved with their original radiance to modern day, give an impression of the high artistic culture which the Muscovite state achieved in the 17th century.

Every time period idealizes in its own way, and the 17th century gave rise to its own conventions which one must study in order to recreate the image of mankind of this past time. In the 17th century, a new type of crown appears on images of saints. This not the Byzantine stemmatos of the 11th-12th centuries, nor the sunflower-like crown of the 15th-16th centuries; this is the koruna. Similar koruny were added to Jaroslav, his wife and Vladimir during the restoration of the frescos in St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev by Pjotr Mogila, as preserved in a 1651 sketch by the foreigner van Westerfeld [Illustration 93]. A similar koruna is also seen on the Tsarevich Dmitrij in the Tsar’s Titulary [Illustration 94].

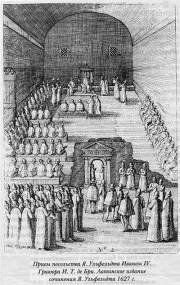

The realism of the portraits in the Titulary peacefully coexists with an array of conventional compositions. Particularly characteristic from this point of view is the 1670’s manuscript “On the Election of Tsar’ Mikhail Fjodorovich to the Throne,” created with create mastery by the iconographers of the Moscow Armory at the order of the boyar Artamon Sergeevich Matveev. The drawings depict one after another scene presenting the solemn ceremonies for the elevation of Filaret to the Patriarch’s throne [Illustration 95], and of the coronation of Tsar’ Mikhail. All of the images are full of the spirit of medieval Russian piety and grandeur. The figures and poses were recreated in meticulous detail by miraculous draftsmen, but all of the men’s faces — with beards or smooth, young or old, monks and priests — are of only a few types repeated an uncountable number of times, without any individualization and without any reproduction of any portrait-like or characteristic traits. Only the figures in the front rows are drawn in detail, and the remainder fuse into a dense mass of heads.

This idealization would continue into later centuries. The affected 18th century idealized its own heroes, giving them fine features, giving them beautiful, mandala-like eyes, giving men a proud, majestic posture, and ladies a salon-like grace. Patriotic Russian literature of the first third of the 19th century and the rise of national self-awareness gave life to a row of literary works which would, in one way or another, find visual embodiment in art or on the stage. These patriotic subjects, of course, emerged first in familiar images of classical figurative art and classical tragedy with their idealized types in antique fashion.

If we review historical and portraiture at the end of the 18th and early 19th centuries, it becomes completely apparent that, with all the realism of reproducing nature exactly, and almost copying details in the manner of interpreting subject, at the heart of the overall composition there lies a certain idealism. The higher a person stood on a hierarchical ladder or the more significant the feat he accomplished, the more conventional his depiction would be. Quite typically for the first quarter of the 19th century, the monument to Minin and Pozharskij on Moscow’s Red Square shows both figures in poses and costumes from ancient statuary.

Until the late 18th-early 19th centuries, it was generally not even thought of to reproduce historical costume. Biblical heroes were clothed in the mode of the artist’s time, not only in conventional depictions of religious art, but even in paintings by the great realist Rembrandt. They also did not know historical perspective, and heroes of the past were presented as conventional symbols, or simply like living contemporaries. This also occured on the stage. In medieval theater, the Madonna or saints would be dressed in contemporary outfits. The Age of Enlightenment and the study of classical history did not create realistic historical costume, but rather brought about only new conventions. Theatrical costume until the late 18th century was generally one of three types: 1) ordinary modern dress, as in the theater of Shakespeare (it became further embellished in French classical tragedy); 2) fantastical dress, as in Italian or French ballet and opera; 3) specialized theatrical costume, as in ancient Greek theater or Italian commedia dell’arte.

The reform of historical theatrical costume first arose in the work of the renowned French tragedian Francois-Joseph Talma, who during the time of the French Revolution dressed for the role of Brutus in a Roman toga, having studied the poses of ancient statues. This bold innovation, as well as the appearance of the well-known actor on stage without a powdered wig, aroused indignation from other actors, who found Talma to be “monstrous” precisely because he “resembled an ancient statue,” as one actress reported after having seen him in a toga. This attitude toward historical costume was to change fundamentally, and soon all of French society was obsessed with the fashion of dressing à l’ antique.

This enthusiasm for classicism led to another extreme: ancient outfits, poses and gestures came to be considered symbols of heroism, loftiness and tragic emotion. Any heroic content began to flow into the tragic-classical forms, regardless of whether it was that of a medieval knight or Roman emperor. There was no true historicity or scientific attitude to this question.

In general, Russian historical costume went through the same phases of development as in the West. Theater of the mid-18th century created conventional heroic figures for tragedies and occasionally grotesque types for comedies. Much has been said about their naturalness, but they are remembered in a very particular way. A characteristic attitude toward medieval Russian dress can be seen in a portrait by Losenko, the first Russian historical painter. Aside from works on Biblical themes that were common for that time, such as “Cain and Abel” or “Hector and Andromache”, Losenko painted a work on a subject of Russian history, “The Grand Prince Vladimir Before Rogneda” [Illustration 98]. This work was painted in the classical style that was typical for that time period. Both Vladimir and Rogneda are dressed in theatrical outfits, with a faint hint of some kind of Russian style, while at the same time, the soldiers in the back of the painting are dressed in relatively realistic Russian military outfits. It is interesting to note that the actor Dmitrevskij posed for this painting.

The clothing on Vladimir and Rogneda in Losenko’s painting are a visual illustration of the Russian costumes that an audience of the 18th century would have seen on the stage. Illustrations for Ozerov’s tragedy “Dmitrij Donskoj” are characteristic in the same way, where the heroes are dressed in severe outfits of a Byzantine type, standing in solemn poses like classical statues. The academician of portraiture P.P. Sokolov writes in his memoirs: “The theater served me well as an accomplice for the development of expression, which I subsequently gave to the persons depicted in my paintings. There was a time when the Academy of Artists gave out a particular golden medal exclusively for expressions, and this was extremely just…”

The connection between theater and portraiture was very great. It is known that the famous painting by Brjullov “The Last Days of Pompeii” was inspired by an opera on the subject which the artist saw in Italy. Pushkin was awed by Brjullov’s talent, and Gogol’, precisely based on this painting, extremely clearly formulated the attitude of his era to the goals of art. He wrote: “Brjullov’s painting is one of the brightest works of the 19th century. It is a bright resurrection of portraiture, which has long been in some time of lethargic condition… His (Brjullov’s) figures are exquisite despite the horror of their position. They drown it out with their beauty. Brjullov’s uses man in order to show all the beauty and supreme grace of his nature… He presents man as beautifully as possible; his female [subject] breathes everything that is best in the world….” And thus under the influence of such classical canons of beauty (as they were understood in the first third of the 19th century) and of the available historical data, that particular Russian costume was formed, which long held on in both artwork and on the stage, and which was preserved right up until the Revolution in Russian courtly ceremonial clothing (on certain ceremonial days, the Empress and ladies of the court would dress in Russian costume, per etiquette).