I often get asked how to find medieval versions of Cyrillic letters to map to modern Russian texts for the purposes of SCA scroll calligraphy. This process can be a little difficult, as a number of the letters (especially vowels) don’t have one to one mappings. The soft sign (ь) and hard sign (ъ) existed but served as vowels, rather than silent pronunciation indicators as they do today. Other vowels like я looked quite different, as the alphabet went through a major reform in the early 1700s. And, there are characters that represent sounds that no longer exist in the modern Russian Cyrillic alphabet.

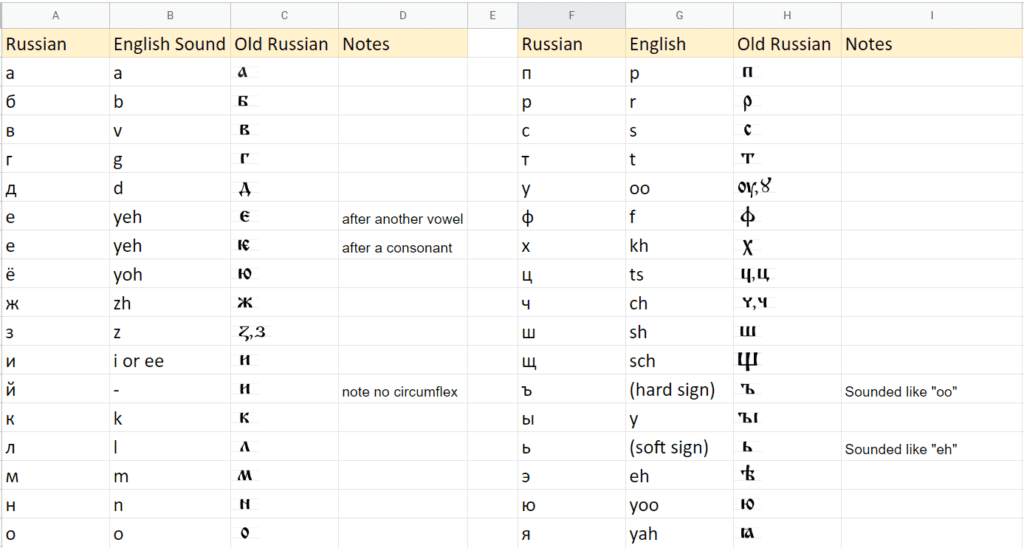

Texts for Russian SCA scrolls are typically in modern Russian, as that would most likely to be spoken by a recipient. With an attempt to make texts largely readable to those who do read modern Russian, I’ve put together the mapping below. The English column is provided to show a generalized pronunciation for each letter. Other mappings are possible, but here’s the table of letters in Russian and the most commonly-seen characters I would transcribe them to in old Russian:

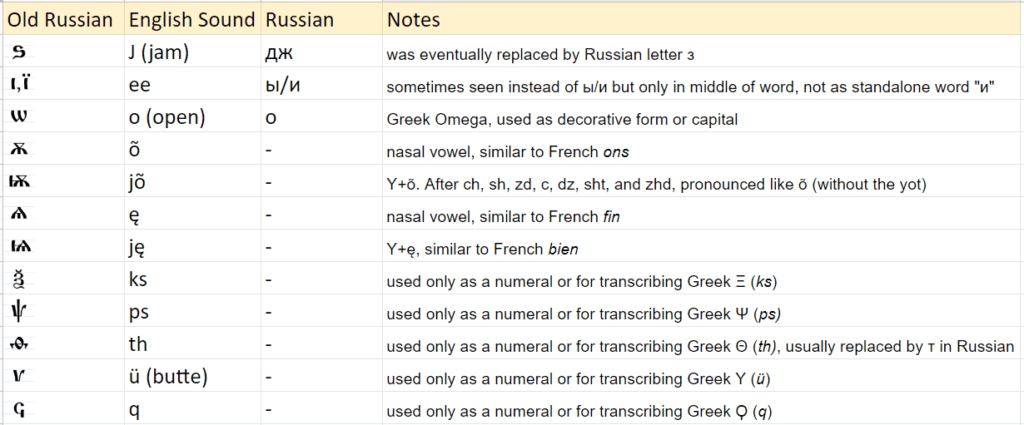

If you’re looking at medieval Russian texts as exemplars, you’ll sometimes see the following additional letters. These are less common, and were used in more specific situations. You’ll probably need these less frequently for a transcription of modern Russian, but I include this table in case you’re curious what they were for:

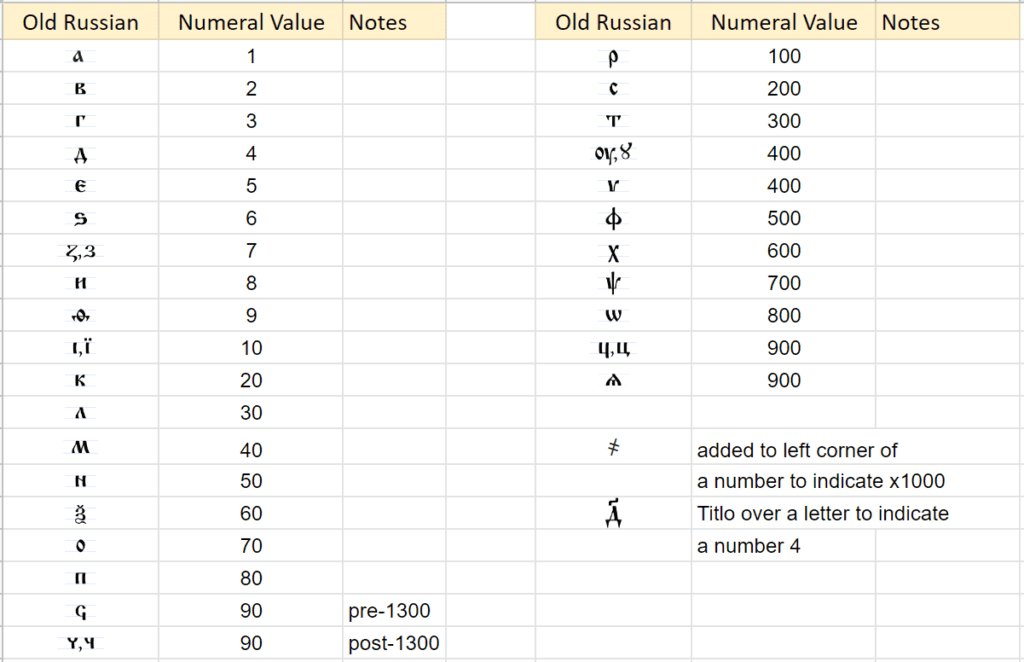

But wait, you say, what’s this about letters being used as numerals? That’s right, they were used to write down numbers, somewhat akin to Roman numerals. Typically a block of letters being used as a numeral would have a titlo symbol (a zigzag line over the word, also used to indicate abbreviations, especially of sacred names/words, such as Бг҃ъ/Богъ/bog/God). Numerals would also sometimes be surrounded by a dot on either side. Here’s how the letters mapped:

Numbers were written with the tens digit AFTER the ones digit, and were added together, so ·гмр· would represent (г+м+р = 3+40+100 = 143). Digits over 999 would use the numeral values for 1-900, with a special hashmark attached to the left side of the number to indicate x1000. So, ·к҂в· would indicate (к+҂в = 20+(2×1000) = 2020). Note the lack of a 0 placeholder for skipped digits (there’s nothing in the ones or hundreds digits in this example).

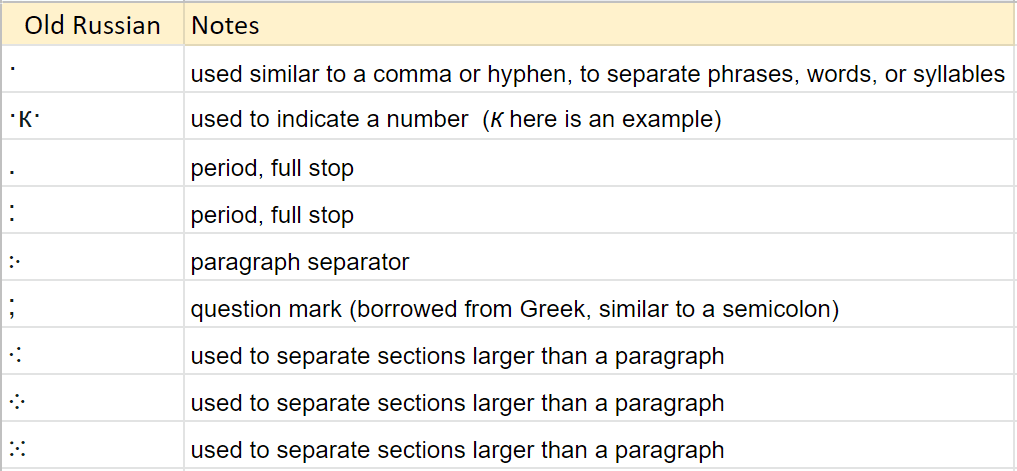

Medieval Russian was written without any spaces, and used some punctuation and diacritic marks to clarify the text. As mentioned above, the titlo character was used to indicate abbreviations, usually of sacred words. In the SCA, you might use those for terms like “King and Queen”, or “A.S.” Acute accents were sometimes used to indicate a stressed syllable (typically if the word could have different meanings based on stress). You’ll sometimes see the following punctuation marks:

Sometimes you’ll see letters floating over the text. What could this mean? Sometimes when abbreviating sacred words, the titlo character above the abbreviation would also include a letter from the middle of the word. In other cases, this simply means the scribe forgot a letter, so he stuck it in over the line to complete the word.

Finally, here’s a trick for finding images online showing medieval Russian calligraphy. For early SCA period (9th-13th century), writing was in a hand called устав / ustav, or uncial, based on Greek hands around the 8th-9th century when Cyrillic was first created. Ustav tends to be blockier and the letters approximate a square in shape. Starting in the 14th century, this shifted to a new style called полуустав / poluustav, semi-uncial, where the letters became smaller and rounder. If you do search in Google for “полуустав” (you can cut and paste the Russian word from here to your search bar), you’ll find a lot of images of texts in semi-Uncial. Finding texts in Uncial is a bit tricker (устав means “charter”, so you get a bunch of images of text documents), but try searching for “устав+шрифт” and you might get better luck.