Introduction

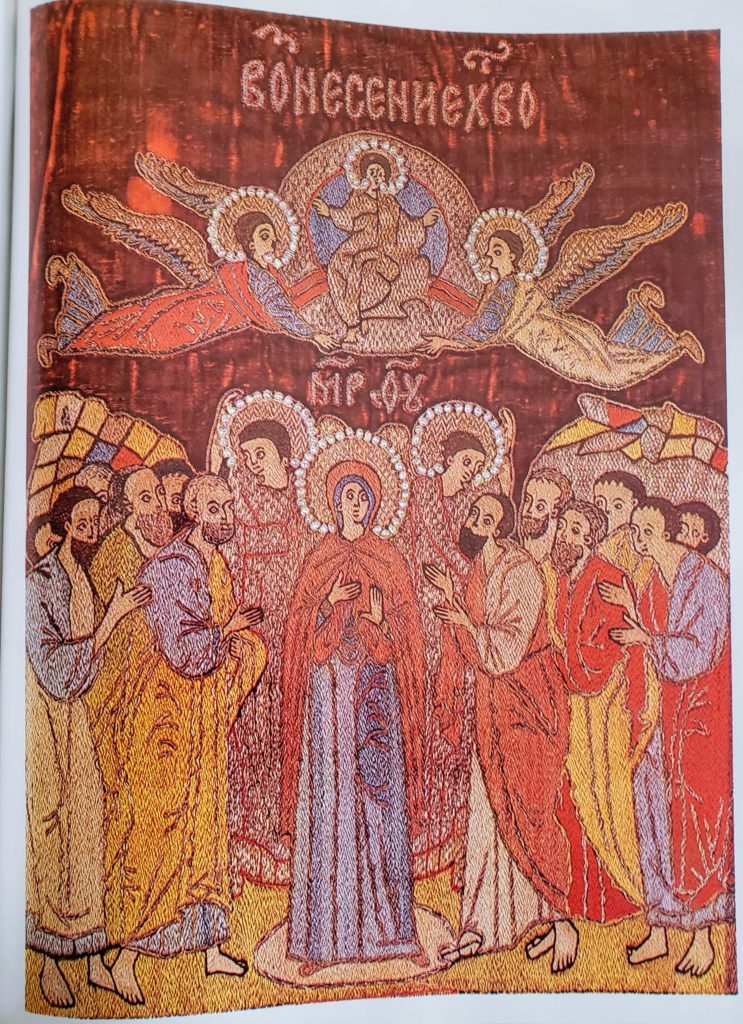

Today I am presenting a reproduction of a 16th century style Russian podea, or embroidered icon. Icons such as this were commonly hung beneath highly-prized painted icons as a form of decoration in the sanctuary, and were sometimes carried into battle or on long journeys. Ecclesiastical embroidery was used in both the Byzantine and Russian Orthodox churches. These traditions share many traits, although the use of color over most of the embroidered surface is more common in Russian, while the Byzantine style emphasized use of metallic thread. This piece is inspired by a section of a podea reproduced in N.A. Majasova’s Drevnerusskoe shit’jo (“Medieval Russian Embroidery”), plate 39, shown here in figure 1. It is not intended to be an exact copy, but incorporates techniques and methods seen in period works.

My icon depicts the Ascension, one of the twelve events in the Orthodox festal cycle. This is commonly seen in both Byzantine and Russian art, portrays the moment in the Book of Acts when Christ re-ascended to Heaven following his resurrection. Christ is depicted here in a mandorla (a round- or almond-shaped circle of light), born aloft by two angels. Below, two angles surround the Virgin Mary as the twelve apostles look on.

I embroidered this podea in silk and gold on a damask foundation with river pearl accents around the halos of Christ, the angels, and the Virgin Mary. Expensive fabrics imported from abroad, including damask, were often used as the ground for ecclesiastical embroidery in medieval Russia. I chose a green damask for the ground of this work, as I was unable to obtain a silk velvet as was used on the original. The damask I selected is very similar in appearance and color of other period Russian embroidered works. I worked the colored areas of the icon in silk using double-strand split stitch, and bordered the work in triple-strand stem stitch. As was common in Russian pieces of this period, I embroidered in solid blocks of color, rather than the finely-gradated shading as would be more commonly seen in Opus anglicanum. Fine shading of color was rarely seen in Russia until later period or post-period works.

For the metalwork, I used a golden thread modernly referred to as “Japan gold,” very similar to the metallic threads used in both Rus’ and Byzantium. This is composed of a thin strip of gilt metallic foil wrapped tightly around a silken core. During this period in Russia, metallic threads were typically couched to the ground fabric using silk stitches, as I have done here. For the purposes of this work, I used imitation Japan gold, as at the time I did not have a source to purchase actual gold thread. This Japan gold, however, is a reasonable approximation of materials as were used in period. The goldwork on this piece incorporates several couching techniques used in period, including a simple form of Or nué, and diamond-shaped, zigzag and basket-weave surface-couched diapering patterns. The lettering is done in gold laid back and forth across the width of the stroke and underside couched. The river pearls were couched to the work using black silk.

In total, this piece represents approximately 600 hours of work, from August 2003 to October 2004.

An Overview of Byzantine and Russian Ecclesiastical Embroidery

Ecclesiastical art in Russia to a large degree descended from Byzantine art. In order to better understand this art style, it is helpful to see its origins in and divergences from that tradition.

The Byzantine Empire officially adopted Christianity in the early fourth century. By the end of that century, it was already becoming traditional for objects, garments and places used during the holy rites to be richly decorated with religious images. The style of this art was heavily influenced by the various cultures within and around the Byzantine Empire. Ecclesiastical garb was largely adopted from Greek and Persian influences, and the use of painted icons on flat boards to depict the saints and other holy figures has roots in late Roman-Egyptian funereal portraiture. Persian art contributed the “severely stylistic, rigid, and heavily decorated” traits of Byzantine high art. These influences combined with more graceful elements from the Hellenistic tradition to produce a synthesis that was appealing to both the upper and lower classes of the Empire.[1]Johnstone, Pauline. The Byzantine Tradition in Church Embroidery. London, 1967, pp. 2-6.

Extant works of Byzantine ecclesiastical embroidery date from the Palaeologus dynasty in the mid-13th century, although we have evidence that decorated textiles were highly prized and used in the Eastern Church much earlier. One possible reason for the lack of earlier pieces is that they were destroyed during the iconoclasm of the eighth and ninth centuries, but this does not explain the absence of pieces from the tenth through the thirteenth centuries. Other textiles do exist from that period, including many pieces which were richly woven, but few which are embroidered, as was more commonly seen in later period. It has been theorized that embroidery began to be used by the Byzantines in the thirteenth century as the decline of wealth and power in the empire led the church to seek out cheaper alternatives to intricately woven fabrics.[2]Ibid, pp 7, 10. Embroidered works are seen in the Coptic, Russian and other Eastern churches much earlier, as well as in the West. Given that the ecclesiastical embroidery from 13th-century Byzantium is obviously well-developed and would have required a great deal of time, skill and money to produce, it seems to me incorrect to deem these embroideries a “compromise” brought on by the empire’s decadence. Instead, it seems likely that the Byzantine church incorporated techniques learned from abroad to match their own style and tastes, much as it did with painting and other artistic techniques in the mid- to late-Byzantine period.

As early as the fourth century, religious vestments based on late Roman and Greek attire became formalized, and remained relatively static even until today. For example, we see the chiton of ancient Greece preserved as the Greek sticharion (the equivalent of a Western alb), and cloaks worn in the late Roman period were preserved as the phelonion (chasuble or cope). Symbolic meanings attributed to these articles of attire helped with this preservation and focused attention to particular elements worthy of decoration. Epimanikia, which began as simple bands of trim about the sleeves of early sticharia, were said to represent the manacles used to restrain Christ when he was taken before Pilate. Over time, they developed into heavily embroidered detachable cuffs. The epitrachelion, or stole, a long strip that hung across the shoulders and down the front of the outfit, was used to distinguish a deacon from a priest. This item was given several possible symbolic meanings, including that it represented the rope placed about Christ’s neck when he was led to trial. The epigonation, or maniple, started as a simple towel or folded piece of cloth, but evolved into a stiff diamond of material suspended at knee height from a bishop’s belt, possibly to represent the sword of the Spirit.[3]Ibid, pp. 13-14, 19 All of these articles of clothing were heavily decorated with religious imagery emphasizing their ritual significance.

The Church also adopted the practice of using fabric and embroidery to decorate churches themselves. In the first few centuries C.E., when Christians were still persecuted and it was impossible to have a permanent church structure, rich fabric may have been used to decorate and solemnize any spot chosen to hold the holy rites. Similar decoration was used in Roman and Green templates and would have been quite familiar to early practitioners of Christianity.[4]Ibid, p. 19 Over time, textile elements of church decoration became richly decorated and highly prized. Altar cloths were used to decorate the sanctuary, and Aërs were used to cover the sacred vessels during Communion to keep out flies and other contamination. Curtains were suspended between the pillars around the altar so that the priests could preserve the secrecy of the most sacred moments of liturgy; over time, these curtains would evolve into a wall of wooden icons, known as an iconostasis.

One form of decoration commonly seen in Orthodox churches was a type of embroidered icon called a podea. Wealthy patrons would often donate money for their creation, typically dedicated to accompany a specific painted icon. Podeai would be suspended beneath the icons they were dedicated to, and typically depicted a scene that was either the same as or thematically complementary to that of the icon itself. For example, an icon of the Anastasis might be accompanied by a podea depicting the Ascension. In the Russian tradition, these podeai (called peleny in Russian) were especially popular, and were sometimes carried into battle or on long trips as a more portable replacement for icons of wood.

Ecclesiastical embroidery was heavily influenced by other forms of art, including painting, mosaic, and metalworking. Works in all of these media depicted the figures of the Deësis (Christ, the Virgin Mary, and John the Baptist), saints or other holy figures, and scenes from the Gospels or Apocrypha. Figures and scenes were commonly depicted with very little ornamentation. All effort was concentrated instead on the central subject at hand and the major figures. As a result, icons often have under-developed or ritualized background detail, or sometimes were simply completely covered in gold leaf, creating an ethereal, otherworldly feel which emphasized the divine nature of the subject material.

Festal scenes were an important element in ecclesiastical art in both the Eastern and Western churches due to their central place in Christian dogma. The festal cycle was comprised of twelve events from the Gospels and the Book of Acts. Although the exact set of twelve could vary from set to set, the most frequently seen images are: The Annunciation, the Nativity, the Presentation in the Temple, the Baptism of Christ, the Transfiguration, the Raising of Lazarus, the Entry into Jerusalem, the Crucifixion, the Anastasis, Pentecost, the Ascension, and the Dormition of the Virgin.[5] Martin, Linette. Sacred Doorways: A Beginner’s Guide to Icons. 2002, pp. 182-203. In Eastern iconography, it was common for larger embroidered works such as altar cloths to incorporate the events of the festal cycle in a border around the central work, which might be an image of a saint or other scene. Festal scenes were depicted individually as well, often incorporated into other pieces of ecclesiastical garb or podeai.

Byzantine ecclesiastical embroidery was typically worked almost entirely in metallic thread, with only the face or hands of the figures worked in colored silk. Dark red or blue silk fabric was commonly used as the ground material. Both silver and gold threads were used in Byzantine art. The metallic thread was most frequently constructed from a thin, flat strip of gilt metallic foil, wrapped spirally around a silk core. The core thread was typically yellow, although other colors have been found in extant pieces. The length of metallic thread was folded in half and laid down in dual rows, couched to the piece using silk thread. These couching threads were typically a slightly darker color than the metallic thread and would be pulled tight enough to create a small dent in the line of the metal, creating an illusion of depth. Using this technique, the embroiderer could create complex diapering patterns in the metal. Observing the many pieces reproduced in Johnstone’s work on Byzantine embroidery, one notices that the gold was typically worked either vertically or horizontally, sometimes alternating to create contrast between adjacent sections of the work. The metallic thread was rarely “modeled” to follow the curves or outlines of the object depicted. The silk embroidery for the hands and faces, however, was typically modeled. These color areas are relatively small in comparison to the predominance of metallic thread in many pieces, creating a quite extravagant, awe-inspiring impression.

In 988, Prince Vladimir of Kiev adopted Christianity as the official state religion in Rus’, in conjunction with his marriage to the sister of Byzantine emperor Basil II. Almost immediately after this conversion, Byzantine artists began traveling to Rus’, bringing along their artistic methods and style. Russian tastes and artistic methods influenced the adoption of these Byzantine arts and soon led to divergent artistic schools. Over time, this divergence became stronger due to the distance from Byzantium, the great distance between monastic centers, and the isolation that resulted following the invasion of the Tatar hordes. Although the artistic motifs and styles were originally inherited from Byzantium, by the twelfth century stylistic divergence was already pronounced, emphasizing dramatic use of color and expressive emotion over the more subtle and tonal variations and severe style seen in Byzantine works of the same time period.[6] Lazarev, Victor Nikitich. The Russian Icon: From Its Origins to the Sixteenth Century. Trans. C.J. Dees. 1996, pp. 21-22, 26.

Iconic art in Rus’, as in Byzantium, was created in specialized artistic workshops. In Rus’, these workshops were almost always associated with either a monastery/nunnery, or a royal or wealthy household. There is evidence in Byzantium that both men and women were trained and worked as embroiderers. In Rus’, the embroidery workhouses, called svetlitsy, were almost exclusively filled by women, and the head of the workshop was typically the female head of the household, herself often a trained embroiderer.[7] Majasova, p. 6; Manushina, T.N. Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo drevnej rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1983, p. 11. In both traditions, it is apparent that the needlework and goldwork skills needed to produce ecclesiastical embroidery were learned through a period of apprenticeship — materials were too expensive and works too large and intricate to trust to untrained hands.

Ecclesiastical embroidery seems to have taken hold in Rus’ very rapidly after the conversion to Christianity. As early as 1183, the Chronicles mention that a fire at the Vladimir Uspensky Cathedral destroyed “many items of cloth decorated with gold and pearls which were hung out on holidays.” Embroidered iworks were highly valued, passed down from generation to generation, and were frequently donated to churches or monasteries by royalty and the wealthy. They were also traded or gifted abroad – the Ksilurga Monastery on Mt. Athos in Greece records that it received embroidered epitrachelia and podeai from Rus’ as early as the 12th century, and in the 16th century, the Hilandar Monastery records receiving an embroidered curtain for the Royal Doors of an iconostasis, sent by Ivan the Terrible.[8]Majasova, p. 5.

Looking at the pieces reproduced in books by Majasova and Manushina, or the pieces which were included in the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in the late 1970’s, one is immediately struck by the predominance of color in Russian works, when compared to the mainly metallic appearance of Byzantine embroidery. It is believed that Russian folk art had already emphasized the use of color and embroidery well before the conversion to Christianity, and looking at the earliest surviving pieces of ecclesiastical works, it would appear that their skill and passion was quickly incorporated by the svetlitsy to ecclesiastical works after conversion. Gold and silver thread is still used liberally for angels, divine figures, halos, and inscriptions, but secondary figures and the background are commonly embroidered in brilliant tones of silk. The effect is a much warmer and immediate connection between the viewer and these works. This seems to have been more appealing to Russian tastes, as similar emotionalism is also stressed in Russian painted iconography.

In Byzantium, the gold, silk, and rick fabrics used for ecclesiastical works were produced locally. For the Russian svetlitsy, these materials were all imported. Silk thread was imported from as far away as Persia, and silk brocades, taffeta and damask came from as far away as Italy and Spain. The richest fabrics available were used in a wide array of colors – my research found a spectrum including dark blue and red silks, patterned fabrics, green and yellow damask, and orange and pink satin.[9]See for example, Majasova, plates 1 and 3; Manushina, pp. 55-58, 63, 69, 168. The metallic threads used in Russian embroidery were Rus’ were imported from Byzantium, although the Rus’ appear to have experimented more with technique. Early works used passing gold in split stitch, but later they adopted the Byzantine method of surface couching. The Rus’ experimented the modeling the gold to the curve and drape of the shapes being embroidered, which would have created a dazzling effect as light played off the curves in the candle-lit atmosphere of a church. Works are seen using colored thread to stitch down the gold as well, producing a color shaded effect much like Or nué. About the only component that did not need to be imported was the freshwater pearls used quite liberally on Russian works. These were drilled and strung on silken thread, then couched to the work, sometimes with couched rows of gold cord on either side.

In both Byzantine and Russian workshops, embroidered icons were a collaborative effort of multiple artisans. The “cartoon” or plan for the embroidery was laid out by a master icon craftsman and was transferred in ink onto the fabric. As many pieces incorporated either liturgical or donor inscriptions, another artisan called a “word-writer” was employed to lay out the text. The work was then turned over to the embroiderers.[10] Majasova, p. 5. Although their work was directed by the plan laid out by the icon master, the embroiderers appear to have held a good deal of creative power over the final result of the piece. Color combinations vary widely from one work to another even when depicting the same person or scene, indicating that the selection of color was largely driven by the embroiderer’s taste, the color of the ground fabric, and the availability of materials. The inscriptions on some larger pieces indicate that they took up to 10 years to complete, and even within that time frame, it is likely that they were completed by multiple needle workers embroidering side by side.

The sixteenth century represented the height of pictorial ecclesiastical embroidery in Russia, especially after the move of the patriarchate of the Eastern Orthodox Church from Byzantium to Moscow. After this period, embroidery saw a thematic shift toward a more ornamental style. Works from the 17th century reflect a tendency toward the Baroque, emphasizing pearls and purl gold in leaf or geometric forms. While the pictorial embroidery style was at its height, however, it represented one of the most noteworthy and beautiful forms of art in Russian culture.

Methods of Production

As an embroiderer with a Russian persona, I have long been fascinated by the pieces of ecclesiastical embroidery shown in T.N. Manushina’s book on the collection in Zagorsk, an important monastic center ouside of Moscow which I once had the privilege to visit. Having practiced several methods of early period embroidery, I was interested in working on a piece using late period Russian style and methods, and in particular using the gold-working skills I had been introduced to at an event in 2002. At the time, I had no practical experience doing split stitch or gold-working, and decided to create a piece where I could utilize both techniques.

The first step was to identify a theme and format for the piece. I was particularly inspired by the expressive quality of an icon of the Ascension reproduced in Majasova’s text (figure 1).[11]See reprodution in Majasova, plates 38-39. The Ascension depicts a scene in Acts 1:6-12 when Christ was raised from Earth back to Heaven, as witnessed by the apostles. In the Biblical text, two angels were present at this event, emphasizing its significance. The iconic image of this scene, formalized around the ninth century, shows the Virgin Mary and twelve apostles, although the Bible does not mention that Mary was present, and at this point in Acts there were only eleven apostles. Mary’s presence is primarily symbolic in this scene, and the twelfth apostle may represent either Matthias or St. Paul, who were both called to spread the word of God after this event.[12]Martin, p. 198. Christ is variously depicted as either adult or child form in this scene; depicting Him as a child emphasizes His place as the Son in the Holy Trinity.

I intentionally did not set out to create an exact replica of the work which inspired my project. First of all, the original was worked on a brocade fabric, but was later cut out and transferred onto the current velvet ground. Velvet was actually not commonly used on works until very late period.[13]Johnstone, p. 66. I decided to use brocade as the base for my work. As was done in medieval Russia, I picked the nicest fabric I was able to find, and ended up selecting a silk damask, a type of fabric seen in multiple period works.[14]See reproductions in Manushina, pp. 167-168, 171; Gosudarstvennye muzei, pp. 111-112, 199. This material was light green in color and displayed a raised leaf-shaped pattern, similar to the yellow damask seen in a podea in the Treasures of the Kremlin exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[15]See reproductions in Gosudarstvennye muzei, pp. 111-112. as well as several pieces in Majasova’s book,[16]See reproductions in Majasova, plates 15 and 16. and is almost identical in color to the ground fabric of an Aër in the Zagorsk collection.[17]See reproduction in Manushina, p. 171.

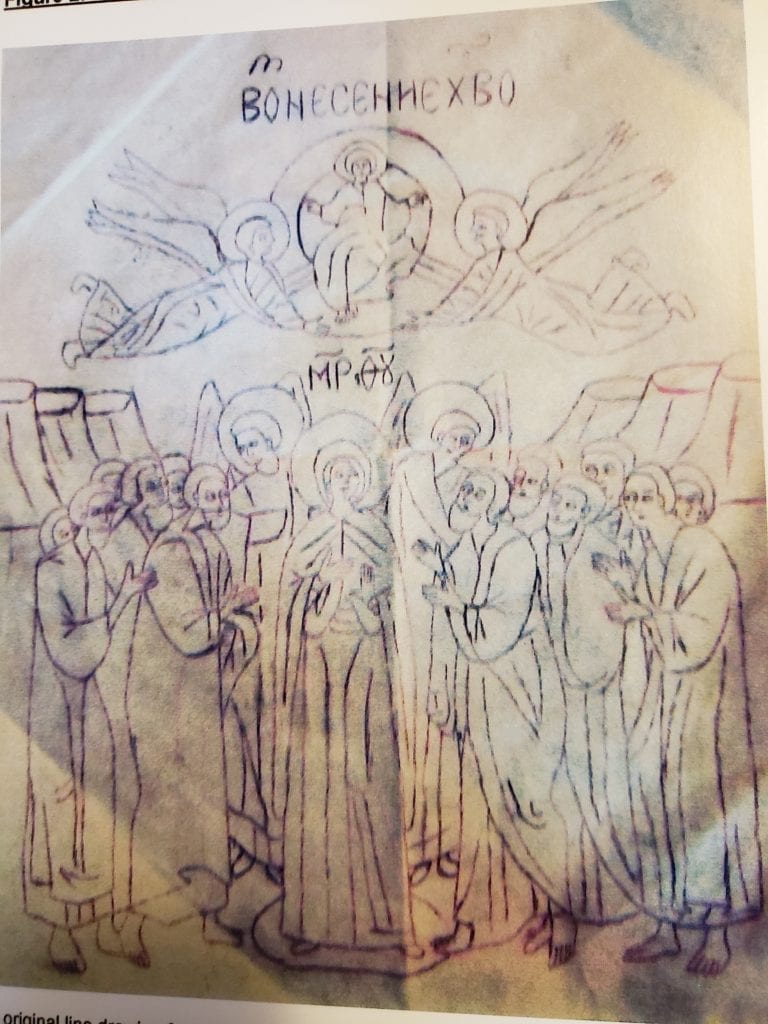

Knowing that icons were often drawn from “pattern-books” in period, I borrowed heavily from the arrangement in the source piece. I first drew out the icon on paper, purposefully retaining the somewhat “cartoon-like” appearance of the figures seen in period embroideries.[18] See figure 2 for a photograph of my original line drawing. After looking through several collections of works and reading up on the subject, I decided to reproduce my work as a podea or embroidered icon, as this form was very commonly seen in Russian embroidery.[19]Gosudarstvennye muzei, p. 196; Johnstone, p. 22. Once the icon had been drawn out, I transferred this design to the fabric and used ink to make the lines permanent so the design would remain visible throughout the course of the project.

As I cut the fabric for the project, it became quickly apparent that the loose weave in areas of the damask pattern made the fabric highly susceptible to fraying. The fabric also threatened to pull and gap exessively as even the slightest tension was applied to it while dressing the embroidery frame. To counteract this, I backed the damask with a sturdy cotton-linen fabric. There is precedence for linings such as this on period pieces,[20]Manushina, p. 59. and it stabilized the fabric enough to last throughout the embroidery process.

As the exact colors used varied greatly in various Ascension icons reproduced in the texts in my bibliography, I took the liberty of picking colors based on availability and combining them in ways which contrasted nicely with the color of the ground damask, while remaining true to the style of period works. The figures were first outlined in black silk using 2-strand satin stitch, and then were filled in using 2-strand split stitch in colored silk. The fields were filled using modeled fashion, that is, following the lines and contours of the area being filled. Faces, hands, and feet were stitched in a flesh-colored silk, again modeled in 2-strand split stitch. Hair was colored using strands of 2 shades of brown worked at the same time, a technique seen in both Byzantine and Russian works.[21]Johnstone, p. 72. See also Majasova, various plates, including plate 39. Note that fields were filled entirely in a single shade, as was commonly seen in period Russian works. Except for very large works like funeral shrouds which include figures at near life size, it was uncommon to see the kind of color shading typical to Opus anglicanum.[22]Note that in the Ascension icon in Majasova, plate 39, two different shades of blue are used to color in Mary’s dress. It appears, however, that this may have been unintentional. Her dress is not worked in a finely graduated fashion, and the change in color may merely represent a change of dye lot. Other apostles are worked in the lighter shade of blue, but the angel in the sky is worked in the darker shade. Mary’s dress is the only area where both shades are used side by side. The ground was covered in a golden-yellow color using horizontal stitches to contrast the primarily vertical stitches seen in the figures’ clothing. A three-strand stem stitch was used to create the border around the design.

Real gold was not available for this project as I was unable to find a source in 2003-2004 for actual gilt thread. As a result, I used imitation gold Japan thread. This is produced using a thin strip of gold-colored metallic foil wrapped around a silk thread core, very similar to the gold used on period works. For the halos, I chose to lay the gold in modeled fashion, following the curve of the outer rim of the halo and couched the gold using yellow silk. The result is a flat, rounded appearance reminiscent of painted icons, and is seen in some period works.[23]See for example, Majasova, plate 5. For the angels in the lower half of the work, I used colored silk to couch down the gold. This practice is also seen in some period works,[24]See for example, Manushina, pp. 180-181. and produces a tint of color that accentuates the gold. The gold thread in these areas was laid down in double rows, and then couched in colored silk thread. All of these areas were worked in surface couching. The gold was worked in adjacent areas in alternating directions to better distinguish the pattern; for example, on the angel on the left, the body is worked in mainly vertical rows, while his arm is worked in horizontal and diagonal rows of gold.

As in the original, the angels in the sky are worked in color to contrast the heavy use of gold in the central mandorla. I picked blue and read as the color of their outfits to mirror the blue and red Or nué used on the angel figures below. Ther wings and halos were worked in gold, and the outline stitches were covered in dual rows of gold to emphasize their divine nature. The nimbus and Christ’s robes were also worked in gold so as to catch and hold the viewer’s attention. I decorated the angel’s wings with a diamond diapering pattern. I laid the gold thread vertically with couching stitches in a slightly darker silk (the same golden-brown color I used for the ground). This darker silk produces enough of a color distinction to create a shadow-like effect, giving the gold a quilted appearance. A similar method was used to create a basket-weave effect in the nimbus and a zigzag pattern for the robes. At first I tried to execute the couching patterns by eyesight alone, but the effect was quite unsatisfying. After some thought, I came up with a much better technique. Before laying down any gold threads, I first laid out the couching pattern I desired in single-strand silk threads directly on the ground fabric. These lines were couched down tightly at any points of intersection to prevent them from shifting about. I then laid down the gold, placing a couching stitch wherever the gold thread crossed over those guidelines. This technique produced a much more even and exact result. For the nimbus, I laid down horizontal guidelines and then laid down the gold vertically; the gold was couched on alternate rows to produce a nice, even basket weave.

At the top of the icon is the phrase Вознесение Хсво, Slavonic for “The Ascension of Christ.” Above Mary’s head is the inscription ΜΡ ΘΥ, the abbreviation for the Slavonic for “The Mother of God.” Both inscriptions were embroidered in gold worked side to side across the width of the letter stroke. This thread was underside-couched, with the couching stitch pulled tightly enough to “pop” the corners where the gold thread turned back to the rear of the work, creating clean edges. This took quite a bit of work, as the backing fabric made it very difficult to pull the gold through the fabric, and the couching thread was prone to snap under tension. To make this process easier, I used a larger needle as an awl to prepare the hole through which the gold would be pulled.

I used natural river pearls, strung on black silk cord and couched to the work using black silk, around the edges of the figures’ halos. I then finished the work by attaching another length of the same brocade to cover the reverse side of the embroidery. As none of the pictures of podeai showed how they would have been suspended beneath an icon, I improvised and added loops at the top of the piece so it could be suspended from a rod. I have since found evidence of a fresco showing a podea beneath an icon,[25]Petrov, A.S. “Shityj obraz pod ikonoj: izobrazhenija na podvesnykh pelenakh.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. 2010, p. 70. but it is also does not clearly indicate the method of suspension.

Final Thoughts

I must question whether I might have picked something much smaller as my first foray into split-stitch and goldwork, had I realized the scope of the project when I began. The project took somewhere in the vicinity of 600 hours to complete, spread out over 13 months, and the materials for the piece probably cost between $100-$200. But, I am extremely happy with the results and found the project very enjoyable and a good learning experience.

The goldworking was a skill that grew on me. At first I found it very difficult to get the gold to cooperate and lay down exactly where I wanted it, but by the end of the piece, when i was working on the figures in the sky, I found goldwork quite enjoyable.

At some point in the future, I would like to revisit these methods to produce several embroidered elements of an Orthodox ecclesiastical outfit, such as an epitrachelion or epigonation. Now that I’ve found a method that works well for the goldwork, I am looking forward to my next opportunity to use that skill. I have already done one other project using split stitch skills I learned (a set of devices for the Northshield Copes), and another piece inspired by Spanish illumination and architecture.

Over the course of the project, I gained a new respect for needleworkers and other artisans who produced iconic art in the Middle Ages. Some of the pieces I’ve seen reproduced in books are truly enormous in scope, and it would take a high level of dedication to complete those projects over the course of up to 10 years. And although I am not Orthodox Christian, I found new respect for the reverence with which icons are held. The work is now framed behind UV-proof glass so that I can display it in my home as a small window into Russian sacred art and belief.

Bibliography

Gosudarstennye muzeji Moskovskogo Kremlja. Treasures from the Kremlin: An exhibition from the State Museums of the Moscow Kremlin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. May 19-September 2, 1979, and the Grand Palais, Paris, October 12, 1979-January 7, 1980. New York, 1979, pp. 110-123, 195-203.

Johnstone, Pauline. The Byzantine Tradition in Church Embroidery. London, 1967.

Lazarev, Viktor Nikitich. The Russian Icon: From its Origins to the Sixteenth Century. Trans. C.J. Dees. Collegeville, MN, 1996.

Lowden, John. Early Christian & Byzantine Art. London, 1997.

Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe Shit’jo. Moscow, 1971. (See my translation of this work to English here: https://rezansky.com/medieval-russian-embroidery-majasova-1971/)

Manushina, T.N. Khudozhestennoe shit’jo drevnej rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1983.

Martin, Linette. Sacred Doorways: A Beginner’s Guide to Icons. Brewster, MA, 2002.

Petrov, A.S. “Shityj obraz pod ikonoj: izobrazhenija na podvesnykh pelenakh.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. 2010, pp. 69-81. (See my translation of this work to English here: https://rezansky.com/the-embroidered-likeness-under-an-icon-images-on-suspended-podeai/)

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Johnstone, Pauline. The Byzantine Tradition in Church Embroidery. London, 1967, pp. 2-6. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Ibid, pp 7, 10. |

| ↟3 | Ibid, pp. 13-14, 19 |

| ↟4 | Ibid, p. 19 |

| ↟5 | Martin, Linette. Sacred Doorways: A Beginner’s Guide to Icons. 2002, pp. 182-203. |

| ↟6 | Lazarev, Victor Nikitich. The Russian Icon: From Its Origins to the Sixteenth Century. Trans. C.J. Dees. 1996, pp. 21-22, 26. |

| ↟7 | Majasova, p. 6; Manushina, T.N. Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo drevnej rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1983, p. 11. |

| ↟8 | Majasova, p. 5. |

| ↟9 | See for example, Majasova, plates 1 and 3; Manushina, pp. 55-58, 63, 69, 168. |

| ↟10 | Majasova, p. 5. |

| ↟11 | See reprodution in Majasova, plates 38-39. |

| ↟12 | Martin, p. 198. |

| ↟13 | Johnstone, p. 66. |

| ↟14 | See reproductions in Manushina, pp. 167-168, 171; Gosudarstvennye muzei, pp. 111-112, 199. |

| ↟15 | See reproductions in Gosudarstvennye muzei, pp. 111-112. |

| ↟16 | See reproductions in Majasova, plates 15 and 16. |

| ↟17 | See reproduction in Manushina, p. 171. |

| ↟18 | See figure 2 for a photograph of my original line drawing. |

| ↟19 | Gosudarstvennye muzei, p. 196; Johnstone, p. 22. |

| ↟20 | Manushina, p. 59. |

| ↟21 | Johnstone, p. 72. See also Majasova, various plates, including plate 39. |

| ↟22 | Note that in the Ascension icon in Majasova, plate 39, two different shades of blue are used to color in Mary’s dress. It appears, however, that this may have been unintentional. Her dress is not worked in a finely graduated fashion, and the change in color may merely represent a change of dye lot. Other apostles are worked in the lighter shade of blue, but the angel in the sky is worked in the darker shade. Mary’s dress is the only area where both shades are used side by side. |

| ↟23 | See for example, Majasova, plate 5. |

| ↟24 | See for example, Manushina, pp. 180-181. |

| ↟25 | Petrov, A.S. “Shityj obraz pod ikonoj: izobrazhenija na podvesnykh pelenakh.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. 2010, p. 70. |