Podeai (singular: podea) are an embroidered fabric item used in Eastern Orthodox churches to adorn and show honor to particularly respected icons. These are seen on altars, below the “local row” of the iconostasis, and below stand-alone icons. They are also sometimes carried in processions. I am presenting here a translation of an article about podeai and their role in the medieval Russian church.

The Embroidered Likeness Under an Icon: Images on Suspended Podeai

A translation of Петров, А.С. «Шитый образ под иконой. Изображения на подвесных пеленах.» Церковное шитье в Древней Руси. 2010, с. 69-81. / Petrov, A.S. “Shityj obraz pod ikonoj: izobrazhenija na podvesnykh pelenakh.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. 2010, pp. 69-81.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.academia.edu/4434496

Among the many fabric items displayed in Byzantine and medieval Russian churches, hanging podeai [peleny] played a significant role. Along with the apron [ubrusets] draped above an icon, and curtains which would sometimes even completely cover an icon, the podea was one of the elements of decoration for an icon. It was a rectangular piece of fabric which was hung beneath the icon. Podeai were an obligatory attribute for icons in the “local row” of the iconostasis in cathedrals and large monastical churches. Russian sources from the 16th-17th centuries attest that podeai were widely used: they accompanied icons during solemn liturgical processions, displayed beneath icons placed on lecterns, and a part of the decoration for portable icons located on the altar.

The functions of podeai have been insufficiently studied. One important and almost singular study is an article by well known Byzantinist A.A. Frolov, a Russian emigree living in Paris, who outlined key areas for the subsequent study of podeai.[1] Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’: un tissu décoratif de 1’église byzantine.” Byzantion, 1938 (13), pp. 461–504. This article was published in 1938 in the journal Byzantion. A.A. Frolov, just like the English researcher P. Johnstone[2]Johnstone, P. The Byzantine Tradition in Church Embroidery. London, 1967. P. 22, saw the podea primarily as an element of decoration. Meanwhile, in one of his epigrams, 12th century Byzantine author Nicolai Calliclis called the podea “an icon of an icon”[3]Sternbach L. “Nicolai Calliclis Carmina.” Rozprawy Akademii Umijetnosci, Wydzial filologiczny, 2e série, XXI. Vol. XXVI. Cracovie, 1903, pp. 340., indicating they had not only decorative but also semantic meaning.

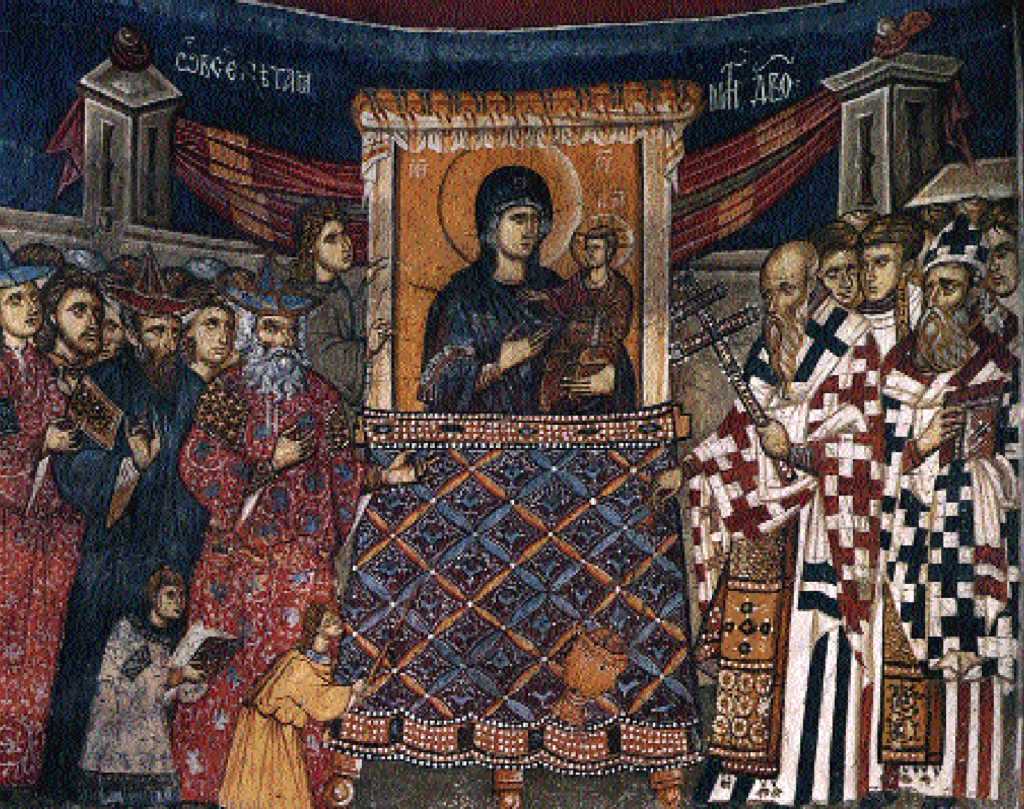

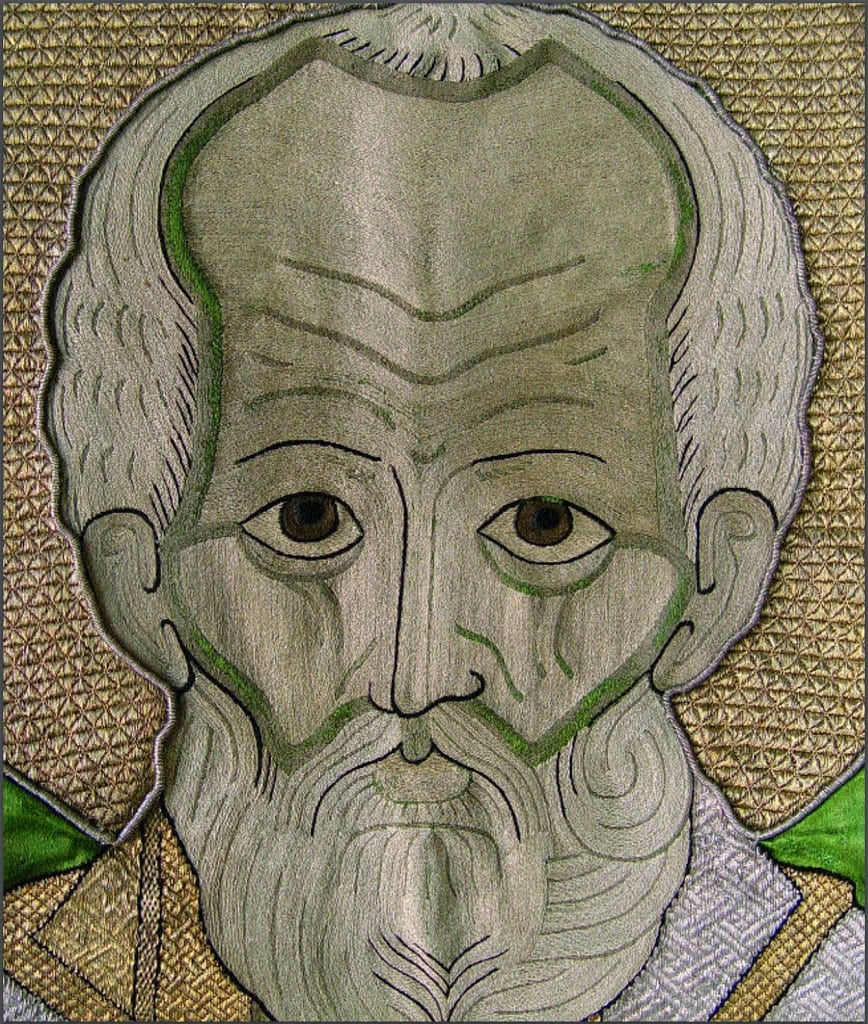

The first mention of podeai that we are aware of in Byzantine sources comes from the 12th century and they became particularly widespread during the Palaeologus era. At this time, podeai are encountered in a number of compositions (Illus 1.) which reflect solemn professions with icons as were performed in Byzantium (these include an illustration of the Praise of the Most Holy Theotokos, the composition “The Triumph of Orthodoxy.”[4]See our article dedicated to an analysis of podea imagery: Petrov, A.S. “Izobrazhenija podvesnykh pelen v vyzantijskom iskusstve.” Ubrus, 2008 (9), pp. 3-8.

Byzantine podeai were most frequently expensive fabrics, perhaps with a cross embroidered in the center, while further ecclesiastic embroidered images were rare. This article is devoted to the creation of podeai with so-called “facial” embroidery (that is, with images of “faces” – human figures).

Among all preserved Byzantine embroidered fabric items, there are only a few that could be called “podeai.” At the same time, it should be noted that the question of their function is covered by scientific literature.

It appears the earliest podea is an embroidered image of Our Lady of the Sign from the Church of St. Sophia in Ohrid (75 x 55 cm, National Historic Museum in Sofia), created in the first quarter of the 13th century (illus 2)[5]”Khristianskoe iskusstvo Bolgarii. Vystavka [proizvedenij iz Natsional’nogo istoricheskogo muzeja v Sofii v GIM]. 1 oktjabrja — 8 dekabrja 2003 goda. Moscow, 2003, catalog item no. 62. . In the middle of a red silk background, the Virgin is depicted with her hands raised upward. On her chest is a medallion with a half-length image of Christ Emmanuel. Around the border is embroidered an inscription in Greek: “O, Thou, Word of God the Father, inexpressibly become flesh through an inexperienced Virgin, we now see a man presenting a the flesh[?] before us, although none of us are worthy! Receive this gift from Theodorus Comnenus and Doukaina Maria Comnene, a kindly couple, and reward the health of their souls!“[6]”Ο ΣΑΡΚΑ ΛΑ ΩΝ ΕΞ ΑΠΕΙΡΑΝΔΡΟΥ ΚΟΡΝΣ + ΤΡΟΠΟΙΣ ΑΦΡΑΣΤΟΙΣ Ω ΘΕΟΥ ΠΑΤΡΟΣ ΛΟΓΕ + ΗΝ ΝΥΝ ΟΠΩΜΕΝ ΑΝΘΡΟΠΟΙΣ ΠΡΟΚΕΙΜΕΝΗΝ + ΕΙΣ ΕΣΤΙΑΣΙΝ ΚΑΝ ΠΑΣΙ ΠΑΡΑΞΙΑΝ + ΔΕΞΑΙ ΤΟ ΔΩΡΟΝ ΕΚ ΘΕΩΔΟΡΟΥ ΤΟΔΕ + ΚΟΜΝΗΝΟΔΟΥΚΑ ΚΑΙ ΔΟΥΚΑΙΝΗΣ ΜΑΡΙΑΣ + ΚΟΜΝΗΝΟΤΥΟΥΣ ΤΗΣ ΚΑΛΗΣ ΣΥΥΖΥΦΙΑΣ + ΑΝΤΙΔΙΔΟΥ ΔΕ ΨΥΧΙΚΗΝ ΣΩΤΗΡΙΑΝ” My heartfelt thanks to A. Nikiforov who translated this inscription at my request. The Theodorus Comnenus mentioned in the inscription was the despot of Epirus who captured Ohrid in 1216 and was crowned there in 1223. Therefore, we can deduce that the podea was created after 1216.

N.P. Kondakov published this monument, calling it an “embroidered podea”[7]Kondakov, N.P. Makedonia: Arkheologicheskoe puteschestvie. St. Petersburg, 1909, p. 270.. L. Mirkovich considered it to be an Aër[8]Mirkovich, L. “Iskusstvo tserkovnogo shit’ja. III. Vozdukhi.” Ubrus, 2006 (5). Trans. by E. Katasonova. p. 49.. In favor of this being an Aër, we could discuss the iconography of Our Lady of the Incarnation, which in later times was commonly used to decorate liturgical veils. The embroidered inscription also has liturgical allusions. The intent of this text’s author could be interpreted as follows. “The flesh” which “we now see a person presenting” would be the prepared or consecrated Holy Gifts, and this fabric would serve to conceal that which “none of us are worthy” to see. We should note that the inscription is written, with all letters oriented around the center, as was characteristic for later liturgical veils. On the other hand, the text’s liturgical allusions could refer to the image of Our Lady of the Incarnation, which could have a similar series of associations: the Virgin as a cover for the flesh that was prepared within her. The vertical format and size of the item also suggest that the item in question is a podea.

In the Church of Our Lady of Perivlepty (Sts. Clement and Panteleimon) in Ohrid there came a fabric item embroidered with the image of the Crucifixion, which is now located in the National Historical Museum in Sofia (illus 3)[9]“Kristianskoe iskusstvo Bolgarii,” pp. 60-61, no. 63.. In the center of this podea, the size of which is unusual (the length is nearly double normal size, 122 x 68 cm) depicts the Crucifixion; beneath the cross Mt. Golgotha with Adam’s skull. On either side of the cross stand the weeping Mother of God and John the Theologian; above, two mourning angels. A supplemental inscription is embroidered on several lines of unequal height: “I bring the Word to Thou as a gift this depiction of Your Crucifixion, made from material which might be considered worthy; I, the Great Eteriarkh, with my wife Evdokia who is by her mother, grandfather and father a Comnenus, for the absolution of our sins”[10]”+ ΔΑΡΩΝ ΣΟΙ ΚΛΙΝΟΣ ΜΕΓΑΣ ΕΤΕΡΙΡΧΗΣ ΤΥΠΟΝ ΣΗΣ ΣΤΑΥΡΩΣΕΩΣ ΑΝΑΤΥΠΟΣΟΙ ΕΚ ΤΗΣ ΔΟΚΟΥΣΗΣ ΤΑΧΑ ΤΙΜΙΑΣ ΥΛΥΣ + ΣΗΝ ΣΥΔΟΚΥΑ ΤΗ ΟΜΟΖΥΓΩ ΛΟΓΕ ΟΥΖΗ ΚΟΜΝΗΝΗ ΠΛΑΚΥΜΑΤΩΝ +”. Translation borrowed from “Kristianskoe iskusstvo Bolgarii,” p. 60.. It is known that the ktetor mentioned in the inscription was also a patron of the church, which was built in 1295. This allows us to date the item to approximately the same time.

Unfortunately neither the inscription, nor the documents related to Ohrid’s St. Sophia reveal the main purpose of this item. A.A. Frolev, without justifying his position, called it a podea[11]Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’…,” p. 487.. L. Mirkovich decided that this item was an Aër[12]Mirkovich, L. “Iskusstvo tserkovnogo shit’ja…,” p. 50.. Bulgarian historian Ju. Bojcheva, having dedicated a separate article to this item, supported A.A. Frolov’s opinion[13]Bojcheva, Ju. “Edin pamjatnik na vizantijskogo vezba ot Okhrid: datirovka i atributsija.” Problemy na izkustvoto. 1998(3), pp. 8-12.. Pointing to traces of wax and soot on the upper parts of the item, she suggested that it may have served as podea for a diptych altar icon of the Virgin Hodegetria [Our Lady of the Way] and the Crucifixion, dated to 1270-1280 from Ohrid, which may also have been used as an image for solitary worship in a series used during Holy Week. According to I.A. Sterligova, “the unusual length of this podea is tied to its allocation to a high prokynetarion with a canopy, where the revered icon was located.”[14]Sterligova, I.A. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevaja pelena v ikone.” Vizantijskij mir: iskusstvo Konstantinopolja v natsional’nye traditsii. K 2000-letiju khristianstva. Pamjati Ol’gi Il’inichny Podobedovoj (1912-1999): Sbornik statej. Moscow, 2005, p. 564, note 16.

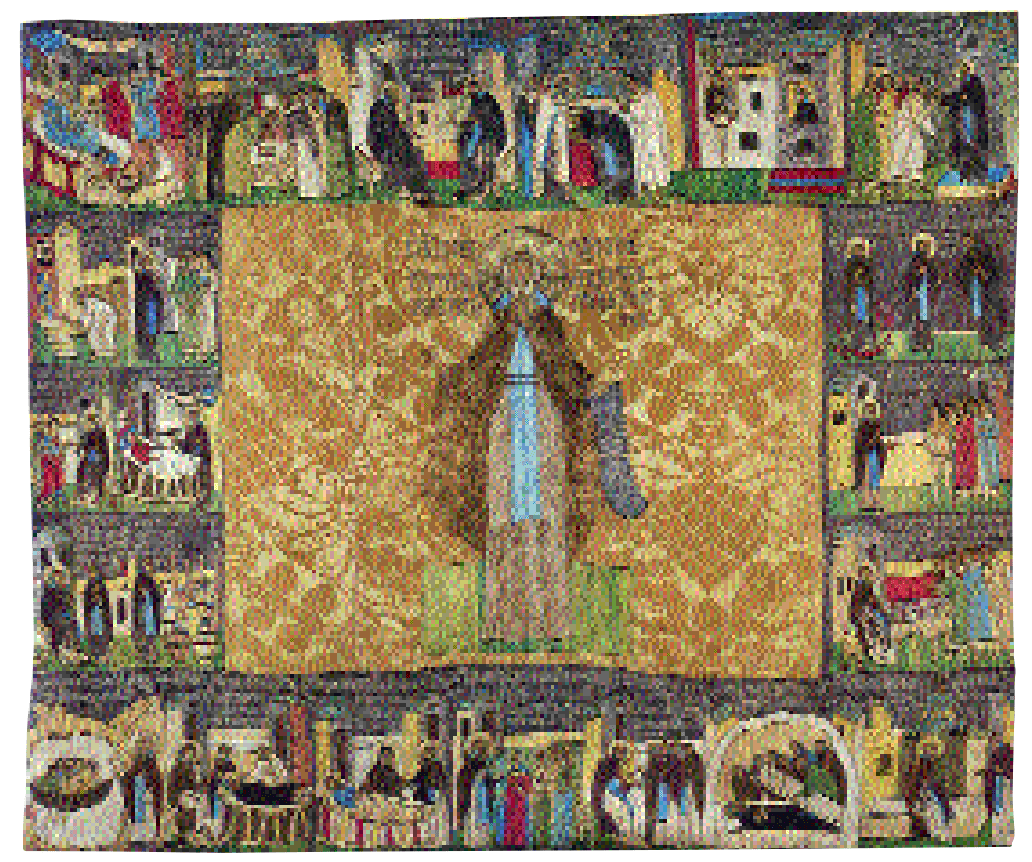

Scholars also consider another fabric item embroidered with the image of the Presentation of Mary from the same church in Ohrid to be a podea; its current location is unknown.(Illus. 4)[15]Originally published: Kondakov, N.P. Makedonia…, pp. 270-273, illus. 187. A. Frolov also recognized it as a podea (Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’…,” p. 287), as did I.A. Sterligova (Sterligova, I.A. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevaja pelena…,” p. 564. Also, note 16.)

Another famous fabric is a depiction of the Annunciation and the Birth of Christ, dated to the 14th century, and preserved at the Monastery of Hilandar on Mt. Athos.(illus. 5) Originally described by L. Mirkovich as an Aër, it continued to be called such in a series of subsequent publications.[16]Mirkovich, L. “Iskusstvo tserkovnogo shit’ja…,” p. 49. In modern day, however, scholars consider it to be a podea.[17] See Stojanovich, D. Istorija primenjene umetnosti kod Srba. Tom 1: Srednjovekovna Srbija. Beograd, 1977, p. 326; Bouras, L. “The Epitaphios of Thessaloniki Byzantine Museum of Athens N. 685.” L’art de Thessalonique et des pays balkaniques et les courants spirituels au XIV siécle. Belgrade, 1987, p. 213, plate 4; Sterligova, L. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevaja pelena…,” p. 564. The iconographic composition of the work points to its use in this manner. Similar images are not found on liturgical veils in the Byzantine period.[18]We are aware only of very late examples. For example, the Stroganov artisans embroidered a composition of the Annunciation on veils. See: Silikin, A.V. “Vozdukh, vyshito Blagoveschenie Prechistye Bogoroditsy.” Ubrus, 2007(7), pp. 3-6; however, the peculiarity of this choice of image can be partly explained. See for example the Ustyug Annunciation, in which the image of the Christ child appears on the breast of the Virgin Mary. That is, it depicts the moment when the incarnation started, and of the birth of Christ. which would have been appropriate for a fabric used while performing the sacrament of the Eucharist. It is possible to suggest with a great degree of certainty that this item was hung as as podea beneath an icon of the Blessed Virgin or one of the Marian feast days.

Hilandar Monastery on Mt. Athos. Fragment.

Among preserved items of Byzantine embroidery, there is yet one more item, the purpose of which is a source of controversy among scholars. This is a fabric embroidered with the images of Archangel Michael and Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus in the role of St. Jesus son of Naue [Joshua] (Palazzo Albani, Urbino).(illus 6) In the center of a square (each side is around 75 cm) of purple silk, the archangel is depicted in military armor with his wings spread wide. Around the edges on a series of horizontal bands are embroidered the words of Manuel’s prayerful appeal to the archangel: “Like Joshua before me, on bent knee / Having thrown himself at thy feet, / Asking for your strength, / In order to subdue the foreigners’ regiments, / Thus do I, thy servant, Manuel, / The child of thrice-happy Eudokia, bound to Caesar’s line through my father, / And through her mother, scion of the Porphyrogenitus, / Now, as a petitioner, / Throw myself at your feet and implore thou, / Shine on me with your praised wings, / And quickly deliver me from all misfortune / And become my representative and the guardian / Of my soul and flesh for life, / And at the final and terrible Judgement, / Convince the Lord to take me / For I have, since my mother’s womb, trusted / In thou, O leader of the incorporeal.“[19]”Ως πριν Ιησούς του Ναυή κάμψας γόνυ / Των σων ποδων εμμπροσθεν αυτόν ερρ φη, / Αιτων παρά σου δύναμιν είληφεται / Ως αλλοφύλων υποτάξη τά στίφη / Ούτως εγωγε Μανουήλ σος οικετης, / Ευδοκίας παις ευκλεους τρις ολβίου, / Φυτοσπόρον μέν καίσαρα κεκτημένης, / Γεννήτριαν δέ πορφυράνθητον κλάδον / Τά νυν εμαυτόν ικετικω τω τρόπω / Ρίπτω ποσί σου και λιτάζομαι δέ σε / Ως σαις σκεποισ πτέρυξι κεχρυσωμέναις / Καί προστάτην έχω σέ καί φρικτη κρίσει / Ψυχής τε καί σώματος ών εν τω Βίω / Κάν τη τελενταία δέ καί φρικτη κρίσει / Ευρω προσηνη διά σου τόν δεοπότην / Εκ κοιλίας γάρ μετρικος επερρίθην / Επί σέ, ταζίαρχε των ασωμάτων.” I am extremely grateful to A.Ju. Vinogradov, who translated the embroidered inscription at my request. The archangel’s reply is embroidered above Manuel: “I turn my ear to thy prayer and shield / Thou, supplicant, with my wings, / And I shall destroy thy enemies with my blade.“[20]”Ους μου προσέσχε ση δεήσει καί σκέπο / Σέ μέν πτέρυζιν ιδίαις ως οικέτην / Εχθρούς δέ τούς σους ανεγο μου τη σπάθη .”

The technique used to embroider this item is interesting. The majority of the image is covered exclusively with rows of couched gold thread, without any color fill; only the the “facial” areas [face, hands, etc. uncovered by clothing] and a few details of the clothing are embroidered with silk. This linear style is reminiscent of the gilding technique used by Byzantine and medieval Russian “goldsmiths,” especially when creating gates.

The Manuel Palaeologus shown on this podea was the bastard son of Emperor John V Palaeologus. In the early 15th century, a difficult time for the empire, he led the Byzantine navy and in 1411 won a significant victory over the Turks. Immediately after this, he was disgraced and spent the remainder of his life in prison. These biographical facts led L. Serra, who published the first scientific study of this item, to call this a naval standard and to date it to around 1411.[21]Serra, L. “A Byzantine Naval Standard.” The Burlington Magazine, 1919 (Vol 34, No 193), p. 157. Thanks to M.A. Lidova, who brought this item to my attention. This opinion about the item’s purpose was also held by a series of later scholars. But, A. Carile later suggested that this was a podea.[22]Carile, A. “Manuele Nothos Paleologo. Nota prosopografica.” Notizie da Palazzo Albani, Vol 3, no 2-3, 1974, pp. 13-19. He argued that, based on the excellent state of its preservation, he was of the opinion that this item could not possibly have been a banner. However, his argument has a number of weak points. Firstly, given Manuel Palaeologus’s disgrace, a flag with his image would only have been used for the very short time between the depicted victory (that is, the date when production of the flag was completed) and his downfall, which could account for the good preservation of the fabric. Secondly, the very fact that Archangel Michael – leader of the heavenly army and of commander of the Byzantine fleet – as well as the explicit allusion to the Old Testament chieftain Joshua, reinforce the interpretation of this item as a battle flag. A similar subject was famously used by Russian artisans in the 17th century in the so-called “Sapieha Banner.”[23]Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971, p. 32, illus. 54. When comparing that item to the Byzantine work, it is clear that they may have used a certain Byzantine prototype with similar subjects. It is remarkable that Russian scholars did not notice this earlier.

It is possible to find certain data about embroidered podeai in Byzantine manuscript sources. For example, one of the earliest literary references is the Epigram of Nicolai Calliclis dedicated to a podea embroidered with the image of the Holy Mother.[24]Sternbach, L. “Nicolai Calliclis Carmina…” no. 24, p. 340. Another source, the Typikon of the Constantine monastery of Our Lady of True Hope (the typikon dates to 1327-1335), mentions a goldworked podea depicting the four feasts of the Virgin, embroidered with a circle of pearls(?) in the center.[25]Delehaye, H. Deux typica byzantins de l’epoque des Paleologues. Bruxelles, 1921, p. 93; in English translation, see: “Typikon of the Theodora Synadene for the Convent of the Mother of God Bebaia Elpis in Constantinople.” Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents. Trans. A.M. Talbot. Vol. 4. Washington, 2000, p. 1562. It is especially important that the source mentions that this podea was specifically used for an icon of the Assumption of the Most Holy Virgin. Based on these examples, we can see that there was some freedom of choice in podea subject matter vis-à-vis the subject of the icon itself.

The Inventory of St. Sophia of Constantinople, 1396, mentions another example – a podea depicting St. Constantine the Great.[26]Miklosich, Fr., Müller, I. Acta et diplomata graeca medii aevi sacra et profana. Vienna, 1860. p. 596. The Inventory of the Monastery of the Mother of God Eleousa in Stroumitza, attributed to the middle of the 15th century, mentions a podea with the image of Christ surrounded by the apostles;[27]Petit, L. “Le Monastère de Notre Dame de Pitie en Macedoine.” Izvestija Russkogo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo Instituta v Konstantinopole, no. 4, 1900, p. 123; in English translation, see: “Inventory of the Monastery of the Mother of God Eleousa in Stroumitza.” “Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents. Trans. A. Bandy. Vol. 4. Washington, 2000, p. 1673. it does not mention, however, which icon this podea decorated. Among icons listed in this source, we can determine with a high probability for which icon this podea was intended. This was an icon of about 90 cm in height, located in the iconostasis, with an image of Christ between His Apostles Peter and Paul, and other half-length figures (possibly other apostles) on either side.[28]”Inventory of the Monastery of the Mother of God Eleousa in Stroumitza,” p. 1671. The subject matter of the icon and podea are very similar to each other, but lacunae in the text describing other icons do not allow us to assert unconditionally that the podea was intended specifically for this icon.

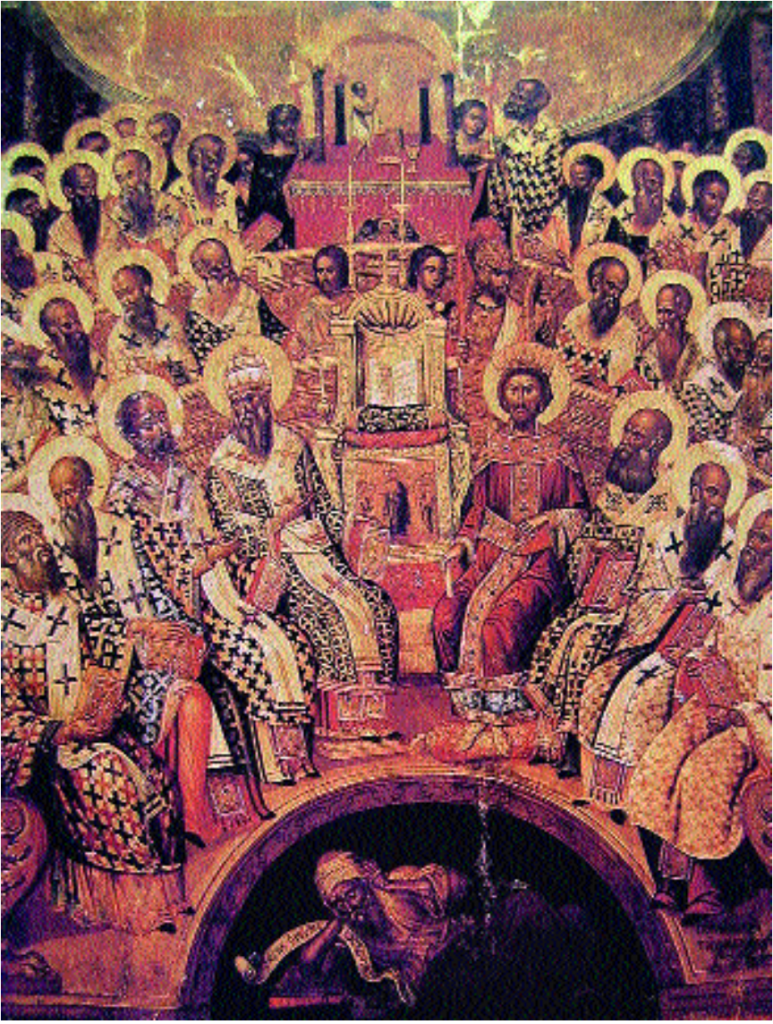

The design of the aforementioned icon is similar to that we find on an icon from Crete, “The First Ecumenical Council,” pained by Mikhail the Damascene in 1591.(illus. 7)[29]Crete, in the Heraklion city museum. See: Walter, Ch. “Icons of the First Council of Nicaea.” Pictures as Language: How the Byzantines Exploited Them. London, 2000, pp. 171-173. Although in this case it is presented, not on an icon, but rather under a Gospel set on the altar. Christ, seated in the middle, blesses with his hands the apostles, who are divided into two groups. The fabric allows a composition which is typical for podeai: the image is framed by an ornamental border, with a fringe hanging from the bottom edge. The edges of the center and of the entire icon are outlined in pearls.

The only image where we see an icon with a podea featuring ecclesiastical embroidery is found in a painting (1386-1390) from the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Cozia, Romania, illustrating the Akathist to the Holy Virgin.(illus. 8)[30]Babic, G. “L’iconographie constantinopolitaine de l’Acathiste de la Vierge à Cozia (Valachie).” Zbornik padova Vizantoloshkog instituta. Vol. 14/15. Beograd, 1973, pp. 186-187. See also: Grabar, A. “La soie byzantine de l’evêque Gunther a la cathedrale de Bamberg.” L’art de la fin de l’antiquite et du moyen age. Vol. 1. Paris, 1968, p. 219. In its center is embroidered in gold the image of the emperor. It precisely captures the appearance of the emperor, who is shown in this frescolike composition praying before an icon: the prayerful placement of his hands and his halo highlight his appearance. The center field is divided by lines forming a diamond-shaped grid, with the intersections decorated with white dots. The podea is framed with gold borders, outlined by a line of pearls. In essence, we see the portrait of a donor, which in fresco or icons often occurred with the image of the one to whom he applied for patronage — Christ, the Virgin, or a saint. If the donor wanted to have his own image next to an illustrious icon, he could add it as a figure embroidered on a podea.[31]The image of the interlocutor could also have been embroidered onto throne vestments. Thus, according to the “Inventory of the Monastery of the Mother of God Eleousa in Stroumitza,” is mentioned an altar cloth (altar podea?) with the image of John I Tzimiskes (ruled 969-976). See the inventory, p. 1673. Aside from the fresco in Cozia, some post-Byzantine Moldavian and Wallachian podeai from the 16th-17th centuries with embroidered images of donors are known.[32]Treasures of Mount Athos. Thessaloniki, 1997. Catalog items 11.35-11.36.

As follows from our analysis of preserved Byzantine works of embroidery and podeai with ecclesiastical embroidery mentioned in Byzantine sources, podeai could feature a multitude of subjects. Available data allow us to suggest that there was variability between the the images on icons and the podeai which served them.

Russian embroidered podeai, as with all embroidery in medieval Rus’, generally followed the Byzantine tradition, including basic patterns of function, typology and symbolic content. Along with this, embroidered podeai became extremely wide spread in Rus’, even more so than in Byzantium itself or the other lands of the Orthodox world. Podeai are frequently mentioned in monastery and church inventories. Sources attest that podeai served as the most important addition to an icon, and by further developing the subject of the icon’s image often became part of a single ensemble with the icon itself.

The majority of medieval Russian podeai with embroidered images would repeat the subject depicted on the icons beneath which they were suspended. In many cases, podeai which duplicated an iconographic image were donated for the decoration of the church, in order to add to the luster of already well-beloved miracle-working icon or to an especially honored image in the “local row” of the iconostasis. It is possible that, in these circumstances, the duplicate subject of the podea was determined by the special significance of the icon. Some beloved icons would accumulate several podeai. For example, the Inventory of the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery from 1601 records several podeai for the local icon of the Assumption of the Virgin “painted by Dionysius Glushitsky:” one with the image of the cross, and 2 others with the image of the Assumption.[33]Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda. St. Petersburg, 1998, p. 45. The mentioned icon is preserved today in the Kirillo-Belozerskij museum-sanctuary (inventory DZh-298); see: Petrova, L.L., Petrova, N.V., Shurina, E.G. Ikony Kirillo-Belozerskogo muzeja-zapovednika. Moscow, 2005, catalog no. 2. But, one of the mentioned icons may be part of the collection of the State Russian Museum (inventory DRT-261), see: Likhacheva, L.D. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo XV-nachala XVIII veka v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Russkogo Muzeja. Katalog vystavki. Leningrad, 1980, catalog no. 9. In other cases, icons were donated to a monastery along with podeai which copied their iconography. Thus, the Donor Book of the Trinity Sergeev Monastery contains a record about a donation by Prince Boris Ushatyj, and then by Prince Vasilij Tjumenskij, of an icon of the Virgin of Tenderness, with podeai decorated with the same image.[34]Vkladnaja kniga Troitse-Sergieva monastyrja. Moscow, 1987, pp. 98, 133. In the census book of the Kostroma Ipat’evskij Monastery, there is mention of an icon of the Holy Mother with the image of Saint Nicholaj written on the same board; on its podea is “embroidered the image of the Most Pure One, and also of Nikolaj.”[35] “Perepisnye knigi Kostromskogo Ipat’evskogo monastyrja 1595 goda.” Chtenija v Imperatorskom obschestve istorii i drevnostej Rossijskikh pri Moskovskom universitete. Vol. 3. Moscow, 1890, p. 13.

It is possible to mention many examples of this similarity of subject between icons and their podeai. What led to this need for customers and artisans of podeai where the image duplicated the icon, that is, essentially, in offering to its own image — the desire to “double” its power and to grace the shrine or to highlight the icon in particular, is a difficult and so far unresolved question. N.A. Majasova wrote that on podeai, they embroidered “the image of that icon under which it would be hung.”[36]Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. p. 7. Later, T.A. Badaeva noted that although “a general thematic accordance between icon and podea” was noticed, the subject of the icon and podea could vary.[37]Badjaeva, T.A. Dekorativnye printsipy drevnerusskogo litsevogo shit’ja XV stoletija. Avtoref. diss. kand. iskusstvovedenija. Moscow, 1974, p. 5. Having studied the Inventory of the Iosifo-Volokolamsk monastery, V.A. Menjalo went further, arguing that “throughout the 15th century, there were no icons with podeai of the same subject.”[38]Menjajlo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo v khramakh Iosifo-Volokolamskogo monastyrja v pervoj polovine XVI veka.” Gos. istoriko-kul’turnyj muzej-zapovednik “Moskovskij Kreml’. Materialy i issledovanija. Vyp. 10: Drevnerusskoe khudozhestvennoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1995, p. 19.

The examples below show just how often and in what different ways this thematic difference could occur on podeai and serve as significant and important additions to the subject of an icon.

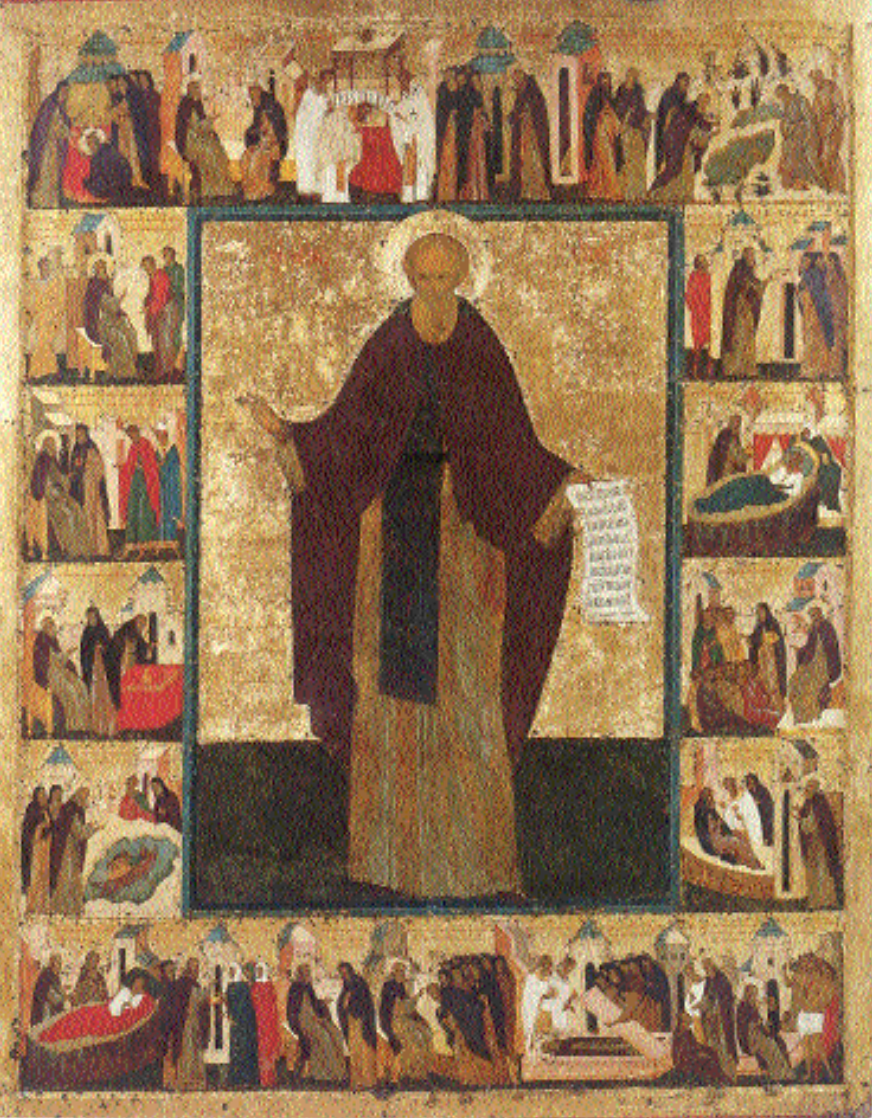

At times, this thematic digression was indeed quite negligible. The icon “The Venerable Cyril Belozerskij with Scenes of his Life” from the Kirillo-Belozerskij Monastery, from around the time of Dionysius, and its podea are now stored in the Russian Museum.(illus. 9-10)[39]Re: the podea, see: Likhacheva, L.D. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, Catalog no. 25. Re: the icon, see: Dionisij “zhivopisets preslovuschij.” Moscow, 2002, catalog no. 38; mentioned in “Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda,” p. 47. Around the edges of the icon are placed various events from the saint’s life and “miracles.” St. Cyril himself is shown in the central panel of the podea, but neither the composition nor the order of the scenes match that shown on the icon.[40]By all appearances, the iconographer who created the icon and the podea’s artisan used different redactions of the life of the Venerable Cyril. It is curious that the individual who attempted to set fire to the venerable one’s cell is named Ioann in the icon, but Andrej on the podea.

Beneath the miracle-working icon “Our Lady of Tenderness” in Suzdal’s Monastery of our Savior and St. Euthemius [Spaso-Evfim’evyj monastyr’] on holidays, a podea was displayed with the image of the Holy Mother in the same pose, but “in the corners near the Virgin” were embroidered “the Evangelists, and also five cherubim and serafim.”[41]Tikhonravov, K. “Opisnaja kniga Suzhdal’skogo Spaso-Eufimieva monastyrja (1660 g.).” Ezhegodnik Vladimir’skogo gubernskogo statisticheskogo komiteta. Vladimir, 1878, Table 2, page 7. The everyday podea was decorated only with an embroidered image of the Holy Mother.

The podea “Our Savior’s Image of Edessa with the Archangels Michael and Gabriel” (illustration 11 [42]jeb: Unfortunately, this image is not included in the PDF), originating from the Pokrovskij Monastery in Suzdal, according to the monastery’s Inventory of 1597, was designed for an icon of the Image of Edessa on which, judging by the inventory, the archangels were absent.[43] “Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale (1597),” published in: Georgievskij, V. Pamjatniki starinnogo russkogo iskusskva Suzdal’skogo muzeja. Moscow, 1927, Appendix 1, pp. 6-7. Today, the podea is preserved in the Vladimir-Suzdal’ Museum-Repository (inventory SM-1045); see: Trofimova, N.N. Russkoe prikladnoe iskusstvo XIII – nachala XX v. iz sobranija gosudarstvennogo ob’edinnenogo Vladimiro-Suzdal’skogo muzeev-zapovednika. Moscow, 1982, Catalog no. 43, color illustration no. 43. At the same monastery, beneath one of two images of the Intercession [Pokrov] in the local row of the iconostasis, on a podea with a similar theme, there is the image of the Deesis with selected saints: “A local icon with the image of Intercession to the Most Pure Virgin… and the image of the Holy Mother has a podea of blue damask, and on it is embroidered the image of the Most Pure One, and also the Deesis and selected saints.” (illustration 12 [44]jeb: Unfortunately, this image is not included in the PDF))[45]Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale…, p. 8; I.A. Sterligova’s opinion is that the Inventory is speaking of a podea now preserved in the State Historical Museum (inv. 78284 RB-2663). See her article dedicated to this: Sterligova, I.A. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevoe pelena k ikone…”, pp. 553-564. We find an interesting addition to the subject of the icon in the Inventory of the Goritskij Monastery of the Resurrection, where beneath an icon of the Image of Edessa was displayed “a valuable crimson podea. On it is embroidered the Image of Edessa, and also Weep Not, Mother.”[46]”Otpisnaja kniga Voskresenskogo Goritskogo devich’ego monastyrja otpischikov Kirillova monastyrja chernogo popa Matveja i startsa Gerasima Novgorodtsa igumen’e Marfe Tovarischevykh — 1661 g. maja 31 (podgotovka k publikatsii Ju.S. Vasil’eva).” Kirillov: Istorichko-krajevedcheskij al’manakh. Issue 1. Vologda, 1994, p. 264; on icons which combine these two subjects, see: Smirnova, E.S. Ikony Severo-Vostochnoj Rusi: Rostov, Vladimir, Kostroma, Murom, Rjazan’, Moskva, Volgogradskij kraj, Dvina. Seredina XIII-seredina XIV v. Moscow, 2004, pp. 302-305.

Podeai could also be decorated with a subject that was completely different from that of the icon. As an example, the icon “Our Lady of the Way” from the Khutyn Monastery of Our Savior’s Transfiguration had a podea with the image of the Dormition of the Virgin: “An image of the Most Pure Virgin Hodegitria… and with this image, a podea embroidered on green satin with gold threads and various silks; and on this podea is embroidered the image of the Dormition of the Most Chaste Virgin.”[47]Makarij, arkhimandrit. Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda. Moscow, 1856, p. 14. Interesting examples of similarly mismatched subjects of icon and podeai were found by V.A. Menjalo in the inventory of the Iosifo-Volokolamsk Monastery.[48]Menjalo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo…”, p. 17. There, in the 1545 inventory, about Dionysius’ icon “Our Lady of the Way” is written the following: “A large local icon. The Most Pure Lady of the Way. Painted by Dionysius… And for this icon, a podea embroidered on taffeta. The Intercession of the Virgin, and around it various saints are embroidered.”[49]Georgievskij, V.T. Freski Ferapontova monastryja. St. Petersburg, 1911. Appendix: “Opis’ Iosifo-Volokolamskogo monastyrja 1545 (7053) goda,” p. 2. The image of the Intercession in this context expands the theme of the Virgin, underlining the role of the Intercession to Our Lady for the human race. It is interesting that in the following inventory in 1572, the podea with the image of the Intercession was associated with an icon of the Dormition.[50]Menjalo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo…”, p. 17. In that same inventory, it indicates that a podea with the image of the Dormition is associated with the aforementioned icon “Our Lady of the Way.”[51]ibid. These examples show that under icons of the Holy Mother or of the Savior, it was entirely possible to find images dedicated to their holidays. But, it could also be the other way around: in the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery, beneath an icon of the Annunciation was a podea with the image of Our Lady of Tenderness (“borrowed,” as it were, from another icon of the Virgin).[52]Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g. (handwritten copy from the 19th century, Sergievo-Posadskij Museum, inv. 187 ruk.), leaf 40. Examples of similar variations are also found in documents from Suzdal monasteries. Beneath a “local” icon of the Transfiguration in the Monastery of Our Savior and St. Euthemius was a podea with an image of the Savior[53]Tikhonravov, K. “Opisnaja kniga Suzhdal’skogo Spaso-Eufimieva monastyrja…”, pp. 4-5., and under a “Friday” icon of the Intercession at the Monastery of the Intercession, a podea with an image of the Holy Mother.[54]Inventory of the Pokrov Monastery (1597), p. 29.

The choice of subject of a podea for an icon of any given iconography could be extremely diverse. Beneath Andrej Rublev’s Trinity in the Trinity Cathedral of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius Monastery was a podea with an image of the Trinity, but which was embroidered with scenes of various holidays around the edges.[55] Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g., leaf 8. Beneath the Trinity icon in the Kostroma Hypatian monastery, the podea was embroidered with an image of the Trinity, and “embroidered with scenes embroidered in 16 locations on dark blue damask,”[56]”Perepisnye knigi Kostromskogo Ipat’evskogo monastyrja…,” p. 2. The podea in question, donated to the monastery of Dmitrij Ivanovich Godunov, now lives in the collection of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin. See: Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo: Katalog. Moscow, 2004, catalog 43. that is, 16 compositions of the acts of the Trinity.(illustration 13 – jeb: unfortunately, this image is not included in the PDF) For the Trinity icon in the Kirillo-Belozerskij Monastery, a podea was dedicated for holidays with an image of the Trinity, as well as “an everyday podea, with the holidays of the Holy Mother embroidered in silver and gold.”[57]Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda…, p. 52. The most peculiar example is found in the inventories of the Staritskij Dormition Monastery, where along with an icon of the Trinity is mentioned “a podea with Abraham and Sarah, embroidered in silver and gold.”[58]Opisnye knigi Staritskogo Uspenskogo monastyrja 7115 – 1607 g., Staritsa, 1911, p. 11.

Beneath “a local icon of Sergei the Miracle-Worker with His Deeds in the Trinity Cathedral in the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery was a podea with image of the appearance of Holy Mother to Sergei – “The Vision of the Miracle-worker Sergei.”[59]Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g…., leaf 25 obv. It is interesting that in the Inventories of the Hypatian Monastery, we find the opposite scenario: an icon of Sergei’s Vision, with a podea embroidered with the image of the Saint.[60]”Perepisnye knigi Kostromskogo Ipat’evskogo monastyrja 1595 goda…,” p. 8.

This variation of the iconography of podeai with regards to their icons could result from the influence of local traditions, for example, as the result of the insertion of the figures of local saints. For example, under an icon of “the Venerable Varlaam the Miracle Worker Standing in Prayer; in a Cloud, the Savior” from Novgorod’s Khutyn Monastery of Our Savior’s Transfiguration, alongside the Venerable Varlaam stands Novgorod’s Saint Ioann — “Archbishop Ivan, and also Varlaam of Khutyn in Prayer; In a Cloud, the Savior.”[61]Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 30. Perhaps for the same reason, in the Kirillo-Belozerskij Monastery, according to the 1601 inventory, they found it possible to accommodate a podea with the image of the Venerable St. Cyril under an icon of Our Lady of the Way.[62]Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda…., p. 99.

Data in the Inventory of the Kirillo-Belozerskij Monastery from 1668 attest to the ability of a donor to affect the composition of the image. It mentions a podea, donated by Prince Fjodor Andreevich Teljatevskij, with the image of Sts. Epiphanius of Salamis and Feodor of Edessa, which originally was dedicated to an icon of St. Epiphanius alone: “A not very large podea… St. Epiphanius of Salamis and also St. Fjodor of Edessa, with the image of the Savior’s head… and this podea was in the sacristy of the Church of the Miracle-Worker Cyril with the image of St. Epiphanius which stood above the Miracle-Worker’s tomb…; given by Prince Fjodor Andreevich Teljatevskij.”[63]”Opis’ Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja (1668).” Zapiski Otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii imperatorskogo arkheologicheskogo Obschestva, vol. II, 1861, p. 314. Prince Fjodor Andreevich Teljatevskij Mikulinskij was steward and governor of Astrakhan, where he died in 1645, last in his line. The prince’s particular veneration of St. Epiphanius is also mentioned in the parish account book for 1645 (7152 by the old chronology), which talks of his building a church over his tomb in honor of the saint: “A stone church to St. Epiphanius of Salamis was built over the body of Prince Fjodor Andreevich Teljatevskij; for the masons, 35 men were given 12 rubles and 5 altyn.” “Prikhodo-raskhodnaja kniga startsa Feoktista Koledinskogo 7152-go godu.” Pamjatniki pis’mennosti v muzejakh Vologodskoj oblasti. Katalog-putevoditel’. Part 4. Issue 1. Vologda, 1985. Appendix 2, p. 148. The appearance of St. Feodor on the podea cannot be explained by any reason other than that the prince wanted to add the image of his own savior-saint.

We should separately mention examples where the images on the icon and podea did not match, and were not linked by meaning. We find evidence of such examples frequently in written sources, although this is more commonly seen in inventories from the 17th and 18th centuries, tied, to be honest, with a more formal relationship to this subject of church decoration in those later times. As the earliest example “we can look at a podea with the image of St. Nikolaj mentioned in the Inventories of the Iosifo-Volamskij Monastery in 1545 and 1572. Originally the podea was dedicated to Dionysius’s icon of The Dormition, but by a later inventory, it had been moved to an icon of John the Baptist.”[64]Menjajlo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo v khramakh Iosifo-Volokolamskogo monastyrja…,” p. 17.

Often when describing icons and podeai which do not agree with one another by theme, it is mentioned that the podea is “dilapidated,” that is, that it’s possible that when a new podea was created for a revered icon, the older podea was transferred to another icon, without concern for its subject. It’s possible to imagine that this is what happened to a podea with the image of St. Varlaam of Khutyn, which was associated to an icon of St. Gregory the Armenian in the Khutyn Monastery.[65]Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 58. Apparently, the podea was transferred there from one of the monastery’s many icons of St. Varlaam of Khutyn.

There is also mention of a podea being transferred from one icon to another in the Inventory of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery from 1641. There, a podea with an image of Our Lady of Kazan’ which was paired with an icon with the same iconography was “taken from that image and placed at the grave of the Miracle-Worker Nikonov, with an icon of Our Most Pure Lady of Tenderness.”[66]Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g…, leaf 160. The same icon also received a podea with the image of Our Lady of the Way from an icon with matching theme.[67]idem., leaf 160 obv. A similar transfer occurred for a podea from the Konevskaja Image of the Holy Virgin to an icon of the Deesis and Holy Mother.[68]idem., leaf 40 obv. By all appearances, the inventory is talking about a podea which is now stored in the collection of the Sergievo-Posadskij Museum (inv. 680). The inventory of Novgorod’s St. Sophia Cathedral from 1736 also attests that an icon of Our Lady of the Don on the altar was decorated with a podea showing The Torment of the Great Martyr Catherine.[69]Opisi imuschestva Novgorodskogo Sofijskogo sobora XVIII-nachala XX v. Moscow/Leningrad, 1988, Issue 1, p. 85. This podea is now located in the Novgorod museum (inv. DRT-27). See: Ignashina, E.V. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe i ornamental’noe shit’jo v sobranii Novgorodskogo muzeja: Katalog. Velikij Novgorod, 2001, cat. 19.

An example of a mismatch of image between icon and podea, but where both compositions interact with one another, is found in the Kirillo-Belozerskij monastery where, according to the inventory from 1668, beneath an icon of the “Presentation of the Queen” was located a podea with the image of “the Most Pure Virgin and the Incarnation of the Son of God … on either side, John the Baptist and Cyril the Miracle-Worker.”[70]”Opis’ Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja (1668)…,” p. 318. A visual image was created in this ensemble of a step-wise transfer of prayers to God. On the podea, the saints, in a sense the very founders of the monastery to whom pilgrims would appeal for aid, pray before an image of the Holy Mother, and on the icon, those prayers are carried by the Holy Mother to Christ himself. Another example comes from the Pokrovskij Monastery in Suzdal. Here, in the local row of the iconostasis, under an icon with “the image of the Most Holy Virgin of the Way” was located a podea, in the center of which was embroidered a cross, “and around the cross, on either side, Nikokaj the Miracle-Worker, and also the Venerable Sergej.”[71]”Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale (1597),” p. 6. This podea, which was stored until the Revolution in the collection of A.S. Uvarov, is now located in the State Historical Museum. See: Katalog sobranija drevnostej gr. A.S. Uvarova. Moscow, 1907, pp. 164-165. The intended use of this podea for an icon of the Holy Mother is underlined by the words of a well known motet to the Holy Mother, the words of which are embroidered around the edges: “and around the podea, on crimson taffeta, words embroidered in silver exalt your name.” It is this embroidered text of the hymn which binds together the icon and its podea.

We should also mention texts which are embroidered on podeai. The traditional placement of inscriptions around the edges of images, known in a few early icons preserved in Sinai and Rome, is almost never seen in later Byzantine and Medieval Russian art. The fields of Byzantine and Medieval Russian icons, with few exceptions, are either busy with the figures of saints, or with scenes from the life of the saint who is on the icon. Meanwhile, many important texts are accommodated on Russian podeai.

The edges of podeai typically served as the location for the arrangement of inscriptions. For ease of reading, the inscription typically were placed on the top and right edges with the letters facing the image, and then continued along the left and then the bottom edges with the letters facing outward. This is as opposed to the typical placement of inscriptions on liturgical veils, where all letters faced toward the center.[72]A podea with an ornamentally-arranged inscription and an image of John the Theologian is located in the collections of the Moscow Kremlin (inv. TK-2505). Here, the inscription (the preface and first lines of the Book of John) starts on the background but then carries over onto the border. I.A. Sterligova has proposed that this podea was intended “as a cover for the altar Gospel” (see Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 152-153; from my point of view, this podea is rather analogous to the podea placed under the Gospel during a reading. It could have been for a holiday, probably for Easter, which is discussed by the choice of passage — the first 17 lines from the Book of John, which are read during the Easter liturgy. More on this can be found in the article: Petrov, A.S. “Evangel’skie peleny…” (out for publication). The overwhelming majority of inscriptions on podeai had a liturgical character; as a rule, they were hymns related to the depicted saint or the events of Biblical history. The image typically was matched with a troparion in his honor; this also applies to podeai with images of holidays.

In a few situations, the affiliation of the podea to a selected icon was underlined by the inscription itself. The podea for the temple icon of the Mantle in the Pokrovskij monastery was decorated with a cross of pearls and plaques, and only the words of the troparion to the Mantle embroidered around the edges link the podea to the subject of the icon.[73]”Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale (1597)…,” pp. 4-5. Under an icon of the Resurrection of Christ in the Khutynskij monastery, there was a podea with an unusual image: “on the podea was sewn a church of silver and gold, and on the same podea, below there were two small crosses of pearls.” This podea was intended specifically for an icon of the Resurrection of Christ, as was underlined by the embroidered text of a hymn which was often sung on Sundays: “The Resurrection of Christ, Shall We See.”[74]Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 17.

Contributor inscriptions and texts of a personal nature were rarely embroidered on podeai. On a podea named “A Prayer for the People” recently found in Suzdal, in medallions that were affixed in the corners, the prayer to the Holy Virgin is embroidered, which carries a sense of a personal character: “Our Lady / Hear the prayers / Of your servants / And deliver us / From every need / And sorrow.”(illus 14)[75]The inscription was read by A.S. Preobrazhenskij, who kindly provided me the text of his as-yet-unpublished article dedicated to this work. See: Preobrazhenskij, A.S. “Pelena ‘Bogomater’ Molenie o narode’ iz grobnitsy arkhepiskopa Arsenija Elassonskogo. Osobennosti ikonografii.” (out for publication) Podeai for icons to Our Lady with the same inscription are also mentioned in the Inventories of the Khutynskij Monastery[76]Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 40. and St. Sophia cathedral.[77]Opisi imuschestva Novgorodskogo Sofijskogo sobora…, p. 86. The famous podea “The Appearance of the Holy Virgin to the Venerable Sergej, with Selected Saints and Holidays,” donated by Grand Prince Vasilij III and Solomonia Saburova to the Trinity monastery, is a rare example of an inscription where the names of the donors are combined with the request (for the birth of an heir): “Give unto us, Oh Lord, fruit of the belly.”[78]Inv. 409. See: Manushina, T.N. Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1983, cat. 10; Also, see: Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’…,” p. 482.

And thus, podeai with embroidered imagery created, along with the icons themselves, an ensemble in which they substantially complemented the icon image. The imagery on the podea could not only duplicate the iconography of the painted icon, but also significantly or even completely differ from it. In such situations, the role of the podea was to develop the content of the icon’s imagery, conferring to it additional semantic nuance.

Liturgical inscriptions played an important role in the iconography of podeai, the presence of which fundamentally differed these fabrics from the majority of medieval Russian icons. The presence of these inscriptions supported the imagery with a verbal level of development of the subject matter, allowing the prayerful to glorify the saint or holiday presented on the podea. In this manner, podeai were not only decoration, adorning and glorifying an icon, but were also an important medium of meaning and figurative content.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’: un tissu décoratif de 1’église byzantine.” Byzantion, 1938 (13), pp. 461–504. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Johnstone, P. The Byzantine Tradition in Church Embroidery. London, 1967. P. 22 |

| ↟3 | Sternbach L. “Nicolai Calliclis Carmina.” Rozprawy Akademii Umijetnosci, Wydzial filologiczny, 2e série, XXI. Vol. XXVI. Cracovie, 1903, pp. 340. |

| ↟4 | See our article dedicated to an analysis of podea imagery: Petrov, A.S. “Izobrazhenija podvesnykh pelen v vyzantijskom iskusstve.” Ubrus, 2008 (9), pp. 3-8. |

| ↟5 | ”Khristianskoe iskusstvo Bolgarii. Vystavka [proizvedenij iz Natsional’nogo istoricheskogo muzeja v Sofii v GIM]. 1 oktjabrja — 8 dekabrja 2003 goda. Moscow, 2003, catalog item no. 62. |

| ↟6 | ”Ο ΣΑΡΚΑ ΛΑ ΩΝ ΕΞ ΑΠΕΙΡΑΝΔΡΟΥ ΚΟΡΝΣ + ΤΡΟΠΟΙΣ ΑΦΡΑΣΤΟΙΣ Ω ΘΕΟΥ ΠΑΤΡΟΣ ΛΟΓΕ + ΗΝ ΝΥΝ ΟΠΩΜΕΝ ΑΝΘΡΟΠΟΙΣ ΠΡΟΚΕΙΜΕΝΗΝ + ΕΙΣ ΕΣΤΙΑΣΙΝ ΚΑΝ ΠΑΣΙ ΠΑΡΑΞΙΑΝ + ΔΕΞΑΙ ΤΟ ΔΩΡΟΝ ΕΚ ΘΕΩΔΟΡΟΥ ΤΟΔΕ + ΚΟΜΝΗΝΟΔΟΥΚΑ ΚΑΙ ΔΟΥΚΑΙΝΗΣ ΜΑΡΙΑΣ + ΚΟΜΝΗΝΟΤΥΟΥΣ ΤΗΣ ΚΑΛΗΣ ΣΥΥΖΥΦΙΑΣ + ΑΝΤΙΔΙΔΟΥ ΔΕ ΨΥΧΙΚΗΝ ΣΩΤΗΡΙΑΝ” My heartfelt thanks to A. Nikiforov who translated this inscription at my request. |

| ↟7 | Kondakov, N.P. Makedonia: Arkheologicheskoe puteschestvie. St. Petersburg, 1909, p. 270. |

| ↟8 | Mirkovich, L. “Iskusstvo tserkovnogo shit’ja. III. Vozdukhi.” Ubrus, 2006 (5). Trans. by E. Katasonova. p. 49. |

| ↟9 | “Kristianskoe iskusstvo Bolgarii,” pp. 60-61, no. 63. |

| ↟10 | ”+ ΔΑΡΩΝ ΣΟΙ ΚΛΙΝΟΣ ΜΕΓΑΣ ΕΤΕΡΙΡΧΗΣ ΤΥΠΟΝ ΣΗΣ ΣΤΑΥΡΩΣΕΩΣ ΑΝΑΤΥΠΟΣΟΙ ΕΚ ΤΗΣ ΔΟΚΟΥΣΗΣ ΤΑΧΑ ΤΙΜΙΑΣ ΥΛΥΣ + ΣΗΝ ΣΥΔΟΚΥΑ ΤΗ ΟΜΟΖΥΓΩ ΛΟΓΕ ΟΥΖΗ ΚΟΜΝΗΝΗ ΠΛΑΚΥΜΑΤΩΝ +”. Translation borrowed from “Kristianskoe iskusstvo Bolgarii,” p. 60. |

| ↟11 | Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’…,” p. 487. |

| ↟12 | Mirkovich, L. “Iskusstvo tserkovnogo shit’ja…,” p. 50. |

| ↟13 | Bojcheva, Ju. “Edin pamjatnik na vizantijskogo vezba ot Okhrid: datirovka i atributsija.” Problemy na izkustvoto. 1998(3), pp. 8-12. |

| ↟14 | Sterligova, I.A. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevaja pelena v ikone.” Vizantijskij mir: iskusstvo Konstantinopolja v natsional’nye traditsii. K 2000-letiju khristianstva. Pamjati Ol’gi Il’inichny Podobedovoj (1912-1999): Sbornik statej. Moscow, 2005, p. 564, note 16. |

| ↟15 | Originally published: Kondakov, N.P. Makedonia…, pp. 270-273, illus. 187. A. Frolov also recognized it as a podea (Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’…,” p. 287), as did I.A. Sterligova (Sterligova, I.A. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevaja pelena…,” p. 564. Also, note 16.) |

| ↟16 | Mirkovich, L. “Iskusstvo tserkovnogo shit’ja…,” p. 49. |

| ↟17 | See Stojanovich, D. Istorija primenjene umetnosti kod Srba. Tom 1: Srednjovekovna Srbija. Beograd, 1977, p. 326; Bouras, L. “The Epitaphios of Thessaloniki Byzantine Museum of Athens N. 685.” L’art de Thessalonique et des pays balkaniques et les courants spirituels au XIV siécle. Belgrade, 1987, p. 213, plate 4; Sterligova, L. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevaja pelena…,” p. 564. |

| ↟18 | We are aware only of very late examples. For example, the Stroganov artisans embroidered a composition of the Annunciation on veils. See: Silikin, A.V. “Vozdukh, vyshito Blagoveschenie Prechistye Bogoroditsy.” Ubrus, 2007(7), pp. 3-6; however, the peculiarity of this choice of image can be partly explained. See for example the Ustyug Annunciation, in which the image of the Christ child appears on the breast of the Virgin Mary. That is, it depicts the moment when the incarnation started, and of the birth of Christ. which would have been appropriate for a fabric used while performing the sacrament of the Eucharist. |

| ↟19 | ”Ως πριν Ιησούς του Ναυή κάμψας γόνυ / Των σων ποδων εμμπροσθεν αυτόν ερρ φη, / Αιτων παρά σου δύναμιν είληφεται / Ως αλλοφύλων υποτάξη τά στίφη / Ούτως εγωγε Μανουήλ σος οικετης, / Ευδοκίας παις ευκλεους τρις ολβίου, / Φυτοσπόρον μέν καίσαρα κεκτημένης, / Γεννήτριαν δέ πορφυράνθητον κλάδον / Τά νυν εμαυτόν ικετικω τω τρόπω / Ρίπτω ποσί σου και λιτάζομαι δέ σε / Ως σαις σκεποισ πτέρυξι κεχρυσωμέναις / Καί προστάτην έχω σέ καί φρικτη κρίσει / Ψυχής τε καί σώματος ών εν τω Βίω / Κάν τη τελενταία δέ καί φρικτη κρίσει / Ευρω προσηνη διά σου τόν δεοπότην / Εκ κοιλίας γάρ μετρικος επερρίθην / Επί σέ, ταζίαρχε των ασωμάτων.” I am extremely grateful to A.Ju. Vinogradov, who translated the embroidered inscription at my request. |

| ↟20 | ”Ους μου προσέσχε ση δεήσει καί σκέπο / Σέ μέν πτέρυζιν ιδίαις ως οικέτην / Εχθρούς δέ τούς σους ανεγο μου τη σπάθη .” |

| ↟21 | Serra, L. “A Byzantine Naval Standard.” The Burlington Magazine, 1919 (Vol 34, No 193), p. 157. Thanks to M.A. Lidova, who brought this item to my attention. |

| ↟22 | Carile, A. “Manuele Nothos Paleologo. Nota prosopografica.” Notizie da Palazzo Albani, Vol 3, no 2-3, 1974, pp. 13-19. |

| ↟23 | Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971, p. 32, illus. 54. |

| ↟24 | Sternbach, L. “Nicolai Calliclis Carmina…” no. 24, p. 340. |

| ↟25 | Delehaye, H. Deux typica byzantins de l’epoque des Paleologues. Bruxelles, 1921, p. 93; in English translation, see: “Typikon of the Theodora Synadene for the Convent of the Mother of God Bebaia Elpis in Constantinople.” Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents. Trans. A.M. Talbot. Vol. 4. Washington, 2000, p. 1562. |

| ↟26 | Miklosich, Fr., Müller, I. Acta et diplomata graeca medii aevi sacra et profana. Vienna, 1860. p. 596. |

| ↟27 | Petit, L. “Le Monastère de Notre Dame de Pitie en Macedoine.” Izvestija Russkogo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo Instituta v Konstantinopole, no. 4, 1900, p. 123; in English translation, see: “Inventory of the Monastery of the Mother of God Eleousa in Stroumitza.” “Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents. Trans. A. Bandy. Vol. 4. Washington, 2000, p. 1673. |

| ↟28 | ”Inventory of the Monastery of the Mother of God Eleousa in Stroumitza,” p. 1671. |

| ↟29 | Crete, in the Heraklion city museum. See: Walter, Ch. “Icons of the First Council of Nicaea.” Pictures as Language: How the Byzantines Exploited Them. London, 2000, pp. 171-173. |

| ↟30 | Babic, G. “L’iconographie constantinopolitaine de l’Acathiste de la Vierge à Cozia (Valachie).” Zbornik padova Vizantoloshkog instituta. Vol. 14/15. Beograd, 1973, pp. 186-187. See also: Grabar, A. “La soie byzantine de l’evêque Gunther a la cathedrale de Bamberg.” L’art de la fin de l’antiquite et du moyen age. Vol. 1. Paris, 1968, p. 219. |

| ↟31 | The image of the interlocutor could also have been embroidered onto throne vestments. Thus, according to the “Inventory of the Monastery of the Mother of God Eleousa in Stroumitza,” is mentioned an altar cloth (altar podea?) with the image of John I Tzimiskes (ruled 969-976). See the inventory, p. 1673. |

| ↟32 | Treasures of Mount Athos. Thessaloniki, 1997. Catalog items 11.35-11.36. |

| ↟33 | Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda. St. Petersburg, 1998, p. 45. The mentioned icon is preserved today in the Kirillo-Belozerskij museum-sanctuary (inventory DZh-298); see: Petrova, L.L., Petrova, N.V., Shurina, E.G. Ikony Kirillo-Belozerskogo muzeja-zapovednika. Moscow, 2005, catalog no. 2. But, one of the mentioned icons may be part of the collection of the State Russian Museum (inventory DRT-261), see: Likhacheva, L.D. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo XV-nachala XVIII veka v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Russkogo Muzeja. Katalog vystavki. Leningrad, 1980, catalog no. 9. |

| ↟34 | Vkladnaja kniga Troitse-Sergieva monastyrja. Moscow, 1987, pp. 98, 133. |

| ↟35 | “Perepisnye knigi Kostromskogo Ipat’evskogo monastyrja 1595 goda.” Chtenija v Imperatorskom obschestve istorii i drevnostej Rossijskikh pri Moskovskom universitete. Vol. 3. Moscow, 1890, p. 13. |

| ↟36 | Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. p. 7. |

| ↟37 | Badjaeva, T.A. Dekorativnye printsipy drevnerusskogo litsevogo shit’ja XV stoletija. Avtoref. diss. kand. iskusstvovedenija. Moscow, 1974, p. 5. |

| ↟38 | Menjajlo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo v khramakh Iosifo-Volokolamskogo monastyrja v pervoj polovine XVI veka.” Gos. istoriko-kul’turnyj muzej-zapovednik “Moskovskij Kreml’. Materialy i issledovanija. Vyp. 10: Drevnerusskoe khudozhestvennoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1995, p. 19. |

| ↟39 | Re: the podea, see: Likhacheva, L.D. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, Catalog no. 25. Re: the icon, see: Dionisij “zhivopisets preslovuschij.” Moscow, 2002, catalog no. 38; mentioned in “Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda,” p. 47. |

| ↟40 | By all appearances, the iconographer who created the icon and the podea’s artisan used different redactions of the life of the Venerable Cyril. It is curious that the individual who attempted to set fire to the venerable one’s cell is named Ioann in the icon, but Andrej on the podea. |

| ↟41 | Tikhonravov, K. “Opisnaja kniga Suzhdal’skogo Spaso-Eufimieva monastyrja (1660 g.).” Ezhegodnik Vladimir’skogo gubernskogo statisticheskogo komiteta. Vladimir, 1878, Table 2, page 7. |

| ↟42 | jeb: Unfortunately, this image is not included in the PDF |

| ↟43 | “Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale (1597),” published in: Georgievskij, V. Pamjatniki starinnogo russkogo iskusskva Suzdal’skogo muzeja. Moscow, 1927, Appendix 1, pp. 6-7. Today, the podea is preserved in the Vladimir-Suzdal’ Museum-Repository (inventory SM-1045); see: Trofimova, N.N. Russkoe prikladnoe iskusstvo XIII – nachala XX v. iz sobranija gosudarstvennogo ob’edinnenogo Vladimiro-Suzdal’skogo muzeev-zapovednika. Moscow, 1982, Catalog no. 43, color illustration no. 43. |

| ↟44 | jeb: Unfortunately, this image is not included in the PDF |

| ↟45 | Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale…, p. 8; I.A. Sterligova’s opinion is that the Inventory is speaking of a podea now preserved in the State Historical Museum (inv. 78284 RB-2663). See her article dedicated to this: Sterligova, I.A. “Drevnejshaja russkaja litsevoe pelena k ikone…”, pp. 553-564. |

| ↟46 | ”Otpisnaja kniga Voskresenskogo Goritskogo devich’ego monastyrja otpischikov Kirillova monastyrja chernogo popa Matveja i startsa Gerasima Novgorodtsa igumen’e Marfe Tovarischevykh — 1661 g. maja 31 (podgotovka k publikatsii Ju.S. Vasil’eva).” Kirillov: Istorichko-krajevedcheskij al’manakh. Issue 1. Vologda, 1994, p. 264; on icons which combine these two subjects, see: Smirnova, E.S. Ikony Severo-Vostochnoj Rusi: Rostov, Vladimir, Kostroma, Murom, Rjazan’, Moskva, Volgogradskij kraj, Dvina. Seredina XIII-seredina XIV v. Moscow, 2004, pp. 302-305. |

| ↟47 | Makarij, arkhimandrit. Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda. Moscow, 1856, p. 14. |

| ↟48 | Menjalo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo…”, p. 17. |

| ↟49 | Georgievskij, V.T. Freski Ferapontova monastryja. St. Petersburg, 1911. Appendix: “Opis’ Iosifo-Volokolamskogo monastyrja 1545 (7053) goda,” p. 2. |

| ↟50 | Menjalo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo…”, p. 17. |

| ↟51 | ibid. |

| ↟52 | Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g. (handwritten copy from the 19th century, Sergievo-Posadskij Museum, inv. 187 ruk.), leaf 40. |

| ↟53 | Tikhonravov, K. “Opisnaja kniga Suzhdal’skogo Spaso-Eufimieva monastyrja…”, pp. 4-5. |

| ↟54 | Inventory of the Pokrov Monastery (1597), p. 29. |

| ↟55 | Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g., leaf 8. |

| ↟56 | ”Perepisnye knigi Kostromskogo Ipat’evskogo monastyrja…,” p. 2. The podea in question, donated to the monastery of Dmitrij Ivanovich Godunov, now lives in the collection of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin. See: Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo: Katalog. Moscow, 2004, catalog 43. |

| ↟57 | Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda…, p. 52. |

| ↟58 | Opisnye knigi Staritskogo Uspenskogo monastyrja 7115 – 1607 g., Staritsa, 1911, p. 11. |

| ↟59 | Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g…., leaf 25 obv. |

| ↟60 | ”Perepisnye knigi Kostromskogo Ipat’evskogo monastyrja 1595 goda…,” p. 8. |

| ↟61 | Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 30. |

| ↟62 | Opis’ stroennij i imuschestva Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja 1601 goda…., p. 99. |

| ↟63 | ”Opis’ Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja (1668).” Zapiski Otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii imperatorskogo arkheologicheskogo Obschestva, vol. II, 1861, p. 314. Prince Fjodor Andreevich Teljatevskij Mikulinskij was steward and governor of Astrakhan, where he died in 1645, last in his line. The prince’s particular veneration of St. Epiphanius is also mentioned in the parish account book for 1645 (7152 by the old chronology), which talks of his building a church over his tomb in honor of the saint: “A stone church to St. Epiphanius of Salamis was built over the body of Prince Fjodor Andreevich Teljatevskij; for the masons, 35 men were given 12 rubles and 5 altyn.” “Prikhodo-raskhodnaja kniga startsa Feoktista Koledinskogo 7152-go godu.” Pamjatniki pis’mennosti v muzejakh Vologodskoj oblasti. Katalog-putevoditel’. Part 4. Issue 1. Vologda, 1985. Appendix 2, p. 148. |

| ↟64 | Menjajlo, V.A. “Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo v khramakh Iosifo-Volokolamskogo monastyrja…,” p. 17. |

| ↟65 | Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 58. |

| ↟66 | Opis’ Troitse Sergieva monastyrja 1641 g…, leaf 160. |

| ↟67 | idem., leaf 160 obv. |

| ↟68 | idem., leaf 40 obv. By all appearances, the inventory is talking about a podea which is now stored in the collection of the Sergievo-Posadskij Museum (inv. 680). |

| ↟69 | Opisi imuschestva Novgorodskogo Sofijskogo sobora XVIII-nachala XX v. Moscow/Leningrad, 1988, Issue 1, p. 85. This podea is now located in the Novgorod museum (inv. DRT-27). See: Ignashina, E.V. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe i ornamental’noe shit’jo v sobranii Novgorodskogo muzeja: Katalog. Velikij Novgorod, 2001, cat. 19. |

| ↟70 | ”Opis’ Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja (1668)…,” p. 318. |

| ↟71 | ”Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale (1597),” p. 6. This podea, which was stored until the Revolution in the collection of A.S. Uvarov, is now located in the State Historical Museum. See: Katalog sobranija drevnostej gr. A.S. Uvarova. Moscow, 1907, pp. 164-165. |

| ↟72 | A podea with an ornamentally-arranged inscription and an image of John the Theologian is located in the collections of the Moscow Kremlin (inv. TK-2505). Here, the inscription (the preface and first lines of the Book of John) starts on the background but then carries over onto the border. I.A. Sterligova has proposed that this podea was intended “as a cover for the altar Gospel” (see Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 152-153; from my point of view, this podea is rather analogous to the podea placed under the Gospel during a reading. It could have been for a holiday, probably for Easter, which is discussed by the choice of passage — the first 17 lines from the Book of John, which are read during the Easter liturgy. More on this can be found in the article: Petrov, A.S. “Evangel’skie peleny…” (out for publication). |

| ↟73 | ”Opis’ Pokrovskogo monastyrja v Suzdale (1597)…,” pp. 4-5. |

| ↟74 | Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 17. |

| ↟75 | The inscription was read by A.S. Preobrazhenskij, who kindly provided me the text of his as-yet-unpublished article dedicated to this work. See: Preobrazhenskij, A.S. “Pelena ‘Bogomater’ Molenie o narode’ iz grobnitsy arkhepiskopa Arsenija Elassonskogo. Osobennosti ikonografii.” (out for publication) |

| ↟76 | Opis’ Novgorodskogo Spaso-Khutynskogo monastyrja, 1642 goda…, p. 40. |

| ↟77 | Opisi imuschestva Novgorodskogo Sofijskogo sobora…, p. 86. |

| ↟78 | Inv. 409. See: Manushina, T.N. Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1983, cat. 10; Also, see: Frolov, A. “La ‘podea’…,” p. 482. |

One Reply to “The Embroidered Likeness Under an Icon: Images on Suspended Podeai”