Today, I’d like to share with you the following article: Новицкая, М.А. “Золотная вышивка Киевской Руси.” Byzantinoslavica, 1972(33), pp. 42-50. This took some tracking down, as I was not able to find it anywhere online, but the folks at Dartmouth’s Baker-Berry library were helpful with tracking down a copy. I stored it in my Dropbox and am providing a translation of it here. This article is referenced by many other works on early Russian goldwork and gives a great overview of this area of study. It also has lots of cool pics that can be of use to the SCA reenactor. Enjoy!

Goldwork Embroidery of Kievan Rus’

A translation of Новицкая, М.А. “Золотная вышивка Киевской Руси.” Byzantinoslavica, 1972(33), pp. 42-50.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here.]

This article was written by the famous Ukrainian researcher Maria Alekseevna Novitskaya (1896-1965), author of a series of works about medieval embroidery. The text of this article is printed from a copy that was typed by the author herself, provided by M.I. Vjaz’mitnaja.

Since ancient times, embroidery has served a large role in the life of all levels of society, serving to decorate both clothing and the household. It is of great interest to characterize as one of the forms of artistic creativity in different historical periods.

The fragility of its materials and its poor conservation do not allow us to completely restore the general outline of all forms of embroidery, in particular for the earliest times. All the more valuable, then, are any remnants of embroidery, no matter how small, which have survived the centuries, been preserved to our time, and now emerge from the earth in archeological digs.

There has not yet been a single study dedicated to goldwork embroidery of Kievan Rus’.[1]{M.A. Novitskaja’s articles “Haptuvannja v Kyiv’skij Rusi. (Za materialamy rozkopok na terytorii URSR).” Arkhelogija XVIII, Kiev, 1965, pp. 24-38 and “Dav’norus’ke haptuvannja z figurymy zobrazhennjamy.” Arkheologija XXIV, Kiev, 1970, pp. 88-99, were published posthumously.} This and later notes in curly braces were made by V.G. Putsko, who prepared this article for publication. There is even an opinion that no works of Kievan Rus’ embroidery have survived to our time.[2]Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstvo Novgoroda. Moscow/Leningrad, 1947, p. 129. This is explained by the great fragmentation of discovered embroidery and their dispersion throughout multiple museum collections, as well as the dearth of publication.

In the time of Kievan Rus’, goldwork embroidery flourished in the lives of the feudal elite, and occupied such a significant role in their lives that the Chronicle even considered it necessary to mention these works of decorative art. For example, it emphasizes that during the sack of Putivl’ by Izyaslav in 1146[3]Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej [PSRL]. Vol 2, Issue 3. St. Petersburg, 1843, p. 27., “altar cloths”[4]Embroidered fabric which decorated the Holy Throne or Altar. and “church vestments, all sewn with gold” perished. In 1288, while listing the items which Grand Prince Vladimir Vasilyevich decorated churches built at various times, mentions “curtains sewn with gold” in Vladimir, and “veils of expensive fabric embroidered with gold and pearls” in Ljubomil.[5]PSRL, Vol 2, Issue 3, p. 223.

We can guess as to the quantity of embroidered examples based on the Chronicle story from 1183 about the fire of the Church of Our Lady of Vladimir, which destroyed “an uncountable number of robes[6]ibid., p. 127. Porty. Secular clothing were often seen in churches, as it was custom for princes to donate them to the church “in their own memory”. PSRL, Book 1, Issue 2, pp. 418, 463. embroidered with gold and pearls which would hang on holidays in two streams from the Golden Gate to Our Lady, and from Our Lady to the master’s hall in two brightly colored rows.” This distance is more than a kilometer in length.[7]Russkie drevnosti v pamjatnikakh iskusstva. Issue VI. St. Petersburg, 1890, p. 91. {In the opinion of N.N. Voronin, the Chronicle is referring to the northern “golden gate” and the southern gate of the cathedral doors, between which in two “wonderous rows” were suspended the fabrics of the cathedral sacristy. Voronin, N.N. Vladimir, Bogoljubovo, Suzdal’, Juriev-Pol’skoj. 2nd ed. Moscow, 1965, p. 47.}

From the excerpts above, it can be seen that goldwork embroidery was used to decorate both ecclesiastical items and secular clothes; in the second case, expensive embroidery acquired a purpose other than decorative: goldwork on the shoulders, as we know from the Chronicle under 1216, became as sign of belonging to the upper class.[8]PSRL, Vol. 1, Issue 3, p. 445.

Portraits of the Grand Prince with his family from contemporaneous frescos[9]Kresal’nyj, M.I. Sofijskij zapovednik v Kieve. Kiev, 1960, illus. 102, 103. {Lazarev, V.N. “Gruppovoj portret semejstva Jaroslava.” Russkaja srednevekovaja zhivopis’. Moscow, 1970, pp. 27-54.} and miniature paintings[10]Bobrinskij, A. Kievskie miniatjury XI v. i portret knjazja Jaroslava Izjaslavicha v psaltyre Egberta, arkhiepiskopa Trirskogo. St. Petersburg, 1902, pp. 11, 12, 15. {Lazarev, V.N. “Iskusstvo srednevekovoj Rusi i Zapad (XI-XV vv.)” XIII Mezhdunarodnyj kongress istoricheskikh nauk. Moscow, 1970, pp. 29-31, with lit. on p. 60; Logvin, G.N. “Miniatjury drevn’ogo kodeksu.” Misetstvo, 1966(6), pp. 14-19.} show that, in addition to the shoulder embroidery mentioned in the Chronicle, the edges of cloaks, cuffs, belts and hems of ceremonial outfits were also richly decorated.

Goldwork embroidery was also used on leather shoes: Daniil Romanovich, Prince of Galicia, had “boots of green leather, embroidered with gold.”[11]PSRL, Vol. 1, Issue 3, p. 187.

Historic materials also shine light on the question of where goldwork at this time was made, and even mention the historical persons who engaged in embroidery. In the 11th century, Anna-Janka, sister of Vladimir Monomakh and daughter of Grand Prince Vsevolod, having become a nun in the Andreevsky monastery in Kiev established by her father, organized there a school where young girls studied gold and silverwork embroidery.[12]Gerebtzoff, N. Essei sur l’histoire de la civilisation Russe. Paris, 1858, p. 124; Odobesko, A.I. “Vosdukh s vyshitym izobrazheniem polozhenija spasitelja vo grob.” Drevnosti Trudy Moskovskogo Arkheologicheskogo Obschestva, vol 4, Moscow, 1874, p. 7; Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstva Novgoroda. p. 129; {Svirin, A.N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1963, p. 21.} This indicates that nunneries were one type of center of artistic embroidery.

V.I. Tatischev says about a different Anna — Anna Vsevolodna, wife of Rjurik Rostislavich (1200) — that she embroidered both for her own family, as well as for the decoration of the Kiev-Vydubitskij Monastery.[13]Tatischev, V.I. Istorija Rossijskaja s samykh drevnejshikh vremen. Vol. 3, St. Petersburg, 1774, p. 329; Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstvo Novgoroda, p. 127. There is also data that in Greece, at the Ksilurgu Monastery on Mt. Athos in 1143, there were Russian epitrachelia and maniples.[14]Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstvo Novgoroda, p. 127.

Undoubtedly, the feudal upper class, taking advantage of lower class labor, had artist workshops, for example, the famous court workshop of Grand Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky.[15]Georgievskij, V.T. “Drevnerusskoe shit’jo v riznitse Troitse-Sergievoj Lavry.” Svetil’nik. 1914(11-12), p. 5. It’s possible that, in addition to female goldwork embroideresses, these also employed men, especially for leatherworking (e.g., for shoes).

The archeological materials underline and enrich the few Chronicle details about embroidery. For this current work, I have used original works of embroidery located in museum collections,[16]State Historical Museum in Moscow, State Historical Museum in Kiev, Historical Museum in L’vov, Cherigov Historical Museum, Historical-Archeological Museum in Khersonesus. as well as reconstructions from partially preserved examples published in archeological accounts.

These embroidered items come from 13 sources:

- 19 fragments of embroidery from Kiev itself;

- 23 from the Kiev region (of these, 5 from Belgorod, 8 from Shargorod, 6 from the village of Ochakov near Nabutovo, 2 from Romashki, 2 from Knjazhaja Gora);

- 2 from Chernigov and the Chernigov region;

- 2 from the Zhitomir region (Rajki);

- 2 from the L’vov region (Starij Galich and Zvenigorod);

- 2 from the Ternopil region (the village of Zhizhava);

- 1 from Chersonesus

These items are very poorly preserved, with sizes of fragments ranging from 4 cm to 10-15 cm, or rarely as large as 25-30 cm. They come from, it appears, no fewer than 40 items of clothing. It is not possible to say with certainty exactly from which part of clothing these fragments originate. The archeological finds mention standing collars, belts, ribbons, and headbands. The fragments predominantly appear to be bands with widths from 1-5.5 cm.

All of the embroidery mentioned above was done on silk fabric of various colors.[17]The color of the silk has been lost; it has all taken on a murky-brown color. The ornamentation on these colored surfaces was embroidered with gold and silver wrapped[18]It is made from thin, narrow (around 0.3 mm) rows of metal, tightly wrapped around a core thread. [jeb: cf. modern “Japan gold” thread] threads (in one case, with wound metallic wire).[19]Spirally-twisted flat wire. [jeb: Gimp, or possibly perl.]

Almost all of the items we studied were worked in the “pierced” style [“v prikep”]. This method’s peculiarity is that the metallic thread, whether wrapped [such as Japan gold] or drawn out [like a wire] is sewn through the fabric. On the front [obverse] side of the work, a stitch is obtained of about 7 mm in length (table I, illus. 1), and on the back [reverse], almost equal to the width of the thread (table I, illus. 2). On the obverse, each new row falls tightly, one after the next, such that each stitch begins in the middle of the previous one. This achieves a solid, almost “wrought” effect. The effect of the metallic brilliance and play of color was intensified by differing the direction of the stitches: the artisan arranged them in parallel rows (table I, illus. 4), or along the curve, following the shape of the picture [in Russian, called “shov po forme”] (table I, illus. 5 – fleurs-de-lys). For stems and narrow strips, they would also use stem stitch [“shov po jolochku“] (table I, illus. 5 – latticework). Enriched color combinations could be achieved by the artist sewing all details of the work, or by leaving the area between ornamental motifs unembroidered. For example, two embroidered items (table I, illus. 3, 4) from the crypt of the Church of the Tithes in Kiev[20]Karger, M.K. Arkheologicheskoe issledovanie drevnego Kieva. Kiev, 1950, illus. 95., we can see how differently the triangles appear when they are completely filled with gold stitches, versus the colored triangles which are only outlined in gold. This difference can also be seen in the treatment of the stems.

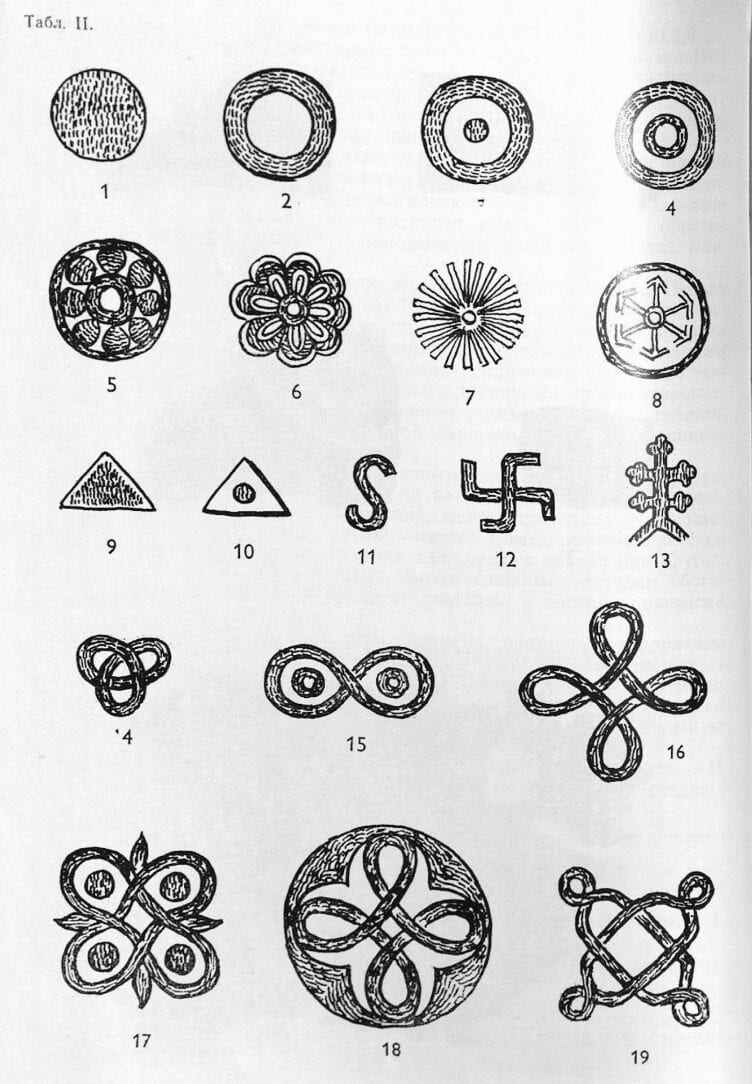

In the studied embroideries, we encounter geometric, floral and zoomorphic designs. The most common of these is geometric (table II), composed from all sorts of circles, rings, rosettes, triangles, swastikas, crosses, and S-shaped whorls.[21]See Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady, Vol. 1, St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 66. Braided motifs predominate, and were very common and characteristic for this time. From particular motifs of braids, formed by bent and intertwined stripes, we can see figure eights, triangles, rhombuses with braids in the corners, and more complex rosettes with overlapping figure eights, rhombuses enclosed in a circle, et. al. (table II, illus. 14-19).

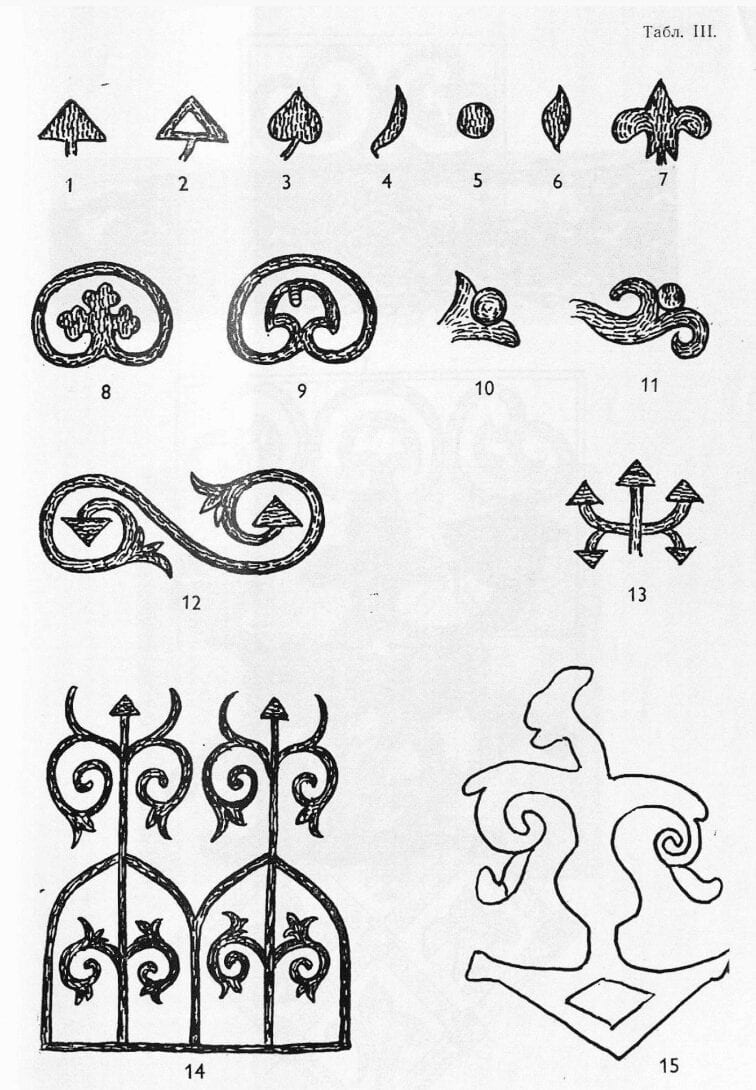

Floral designs are found less frequently, and have a stylized character (table III). Their main elements are triangular, heart-shaped, or elongated leaflets, round or square flower buds, spiral sprouts on straight or curved stems, and fleurs-de-lis[22]Lily of the field is a motif which came from the East., a favorite element in decorative art in medieval Rus’ (table III, illus. 7).

A motif reminiscent of a wide-bladed leaf of a water lily, from the base of which grows a fleur-de-lis, filling in its surface, was very wide-spread in different forms of decorative art of the 11th-12th centuries. It was particularly frequently found on kolts[23]Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady, Vol. 1, pp. 59, 60; Istorija russkogo iskusstva, vol. 1, Moscow, 1953, p. 271. and on fresco paintings, for example, in Kiev’s St. Sophia cathedral. There are two variants of this motif on our embroidered items: on a 11-12th century item from Belgorod(table III, illus. 8)[24]State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-1783; See Polonskaja, N.D. Istoriko-kul’turnyj atlas po russkoj istorii. Kiev, 1913, table XV, illus. 12; Polonskaja, N.D. “Arkheologicheskie raskopki V.V. Khvojko 1909-10 gg. v mestechke Belgorodka.” Trudy predvaritel’nogo komiteta XV arkheologicheskogo s’ezda. Moscow, 1911, illus. 53., and on an embroidery from Chernigov(table III, illus. 9)[25]Historical museum in Chernigov..

On an 11th-12th century embroidered item from Shargorod[26]State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-2651. we see a tree of life (table III, illus. 13) – a motif which comes from ancient times. In its interpretation, it is very similar to an analogous depiction on an embroidery from the Churkinskij burial mound from 12-13th century Nizhny Novgorod.[27]Spytsin, A. “Churkinskij mogil’nik.” Zapiski otdelija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii imperatorskogo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. 5, issue 1, illus 71.

On several fragments from the Mikhailov treasure[28]State Historical Museum in Moscow, OP-1093. See: –. Otchet Arkheologicheskoj Komissii, 1903, illus. 350., fragments of a complicated floral motif are preserved: thin, symmetrical shoots branch off from either side of a tall, spear-shaped stem. The lower part is enclosed in a keeled archway. In some cases, these motifs are united in pairs (table III, illus. 14) Another floral motif on an 11-12th century embroidery from Shargorod[29]State Historical Museum in Kiev, Inv. no. 1381., which arises from a triangle, is made up of plump twisting curls (table III, illus. 15).

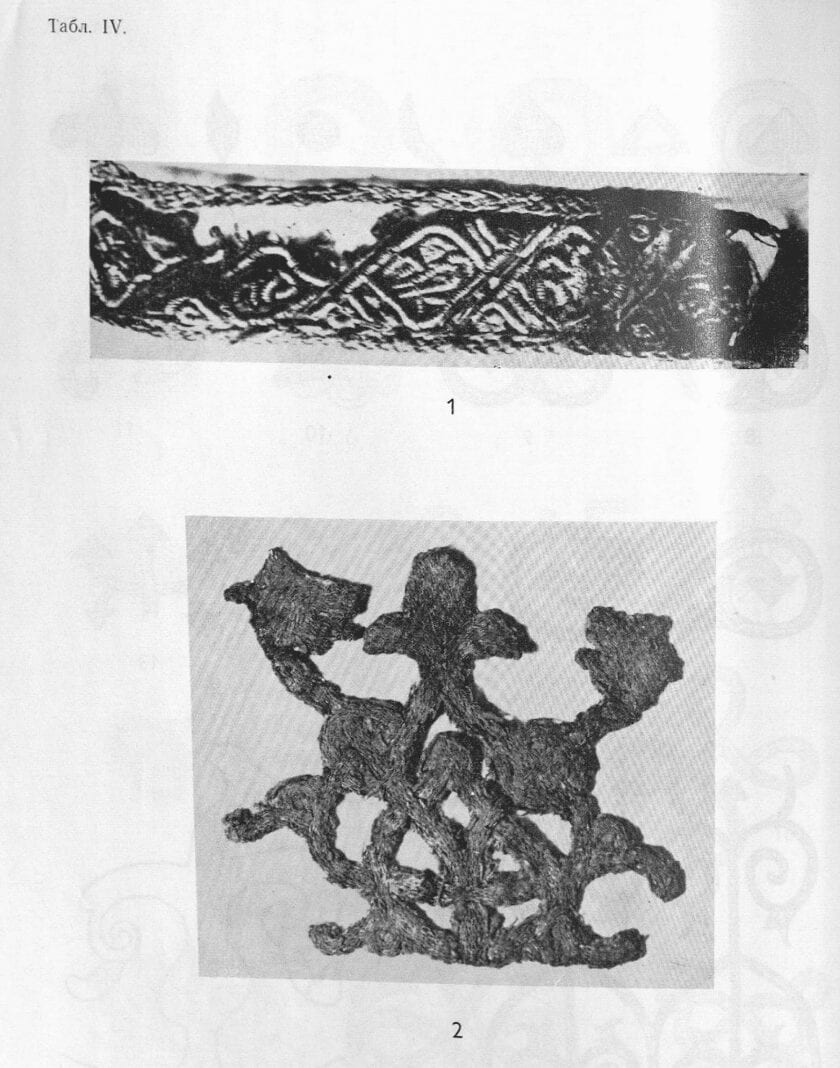

Zoomorphic ornament, in the form of birds and cheetahs, are seen only on 2 embroideries (table IV). Several miniature birds, filled in with gimp, are depicted on an 11-12th century embroidery from Shargorod[30]ibid., inv. no. V-2310.. They are placed in diamonds, part of which are filled in with rosettes. The birds are embroidered in profile, sometimes with their heads turned back over their bodies. One wing is raised aloft. Sometimes, it ends in a curl. Similar depictions of birds were a favorite motif in 11-12th century ornament.

We see analogies to this in an 11th century Kievan manuscript of the words of Grigorij Bogoslov[31]Stasov, V.V. Slavjanskij i vostochnij ornament po rukopisjam drevnego i novogo vremeni. St. Petersburg, 1886, table XII, illus. 19, 27., on the cover of the Juriev Gospel from 1120[32]ibid., table LIII., on a 12th century bronze ark from the city of Vschizh by Master Constantine[33]Rybakov, B.A. Remeslo drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1948, illus. 56., on the cover of a 12-13th century gospel[34]Buslaev, F.I. Istoricheskij ocherk po russkomu ornamentu v rukopisjakh. Petrograd, 1917, p. 4 (illus 3), 22 (illus. 30); Stasov, V.V. Russkij narodnyj ornament. Issue 1, St. Petersburg, 1872, p. IX., on kolts and bracelets from the treasure cache found in 1824 in the Mikhailov monastery in Kiev[35]Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Table 1, illus 59, 60; –. Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol 1, p. 250., on bracelets from the Vladimir treasure cache[36]Istorija kul’tury Drevnej Rusi. vol 2. Moscow/Leningrad, 1951, illus. 213., on the reliefs on a church in Pokrov on the Nerli, 1165[37]Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1, pp. 405, 411, 413, 439., on St. Dmitrij Cathedral in Vladimir, 1193-1197[38]{Varger, G.K. Skul’ptura Drevnej Rusi. Vladimir, Bogoljubovo. Moscow, 1969, pp. 288, 290, illus. 217.}, on St. Grigorij Cathedral in Juriev-Polskij, 1230-1234[39]{Bobrinskij, A.A. Reznoj kamen’ v Rossii. Issue 1, Moscow, 1916, table 30, illus. 9.}, et. al.

The depiction of a bird very similar to ours is also seen on a 12th century embroidery from Vladimir on the Kljazma[40]Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi X-XIII vv. Moscow/Leningrad, 1936, illus. on p. 29., and on a band from Staraja Rjazan’, where the birds stand alongside sacred trees.[41]Jakunina, L.I. “Fragmenty tkanej iz Staroj Rjazani.” Kratkie soobschenvenija Instituta istorii materialnoj kul’tury. 1947 (XXI), illus. 36/3.

Cheetahs form an integral part of a complex knotwork found in one of the 11-12th century graves from Belgorod[42]State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-1783. See: Trudy predvaritel’nogo komiteta XV arkheologicheskogo s’ezda, table XV, illus. 13., on the chest of the deceased. Rising sharply on either side of a fleur-de-lis growing from the knotwork, they give the entire composition a heraldic appearance. The cheetahs have small, upright ears, slightly open mouths, long, thin necks, and curved tips at the ends of their tails (table IV, illus. 2). We were unable to find an exact analogy of this motif in manuscript illumination, nor in carving, where the teratological style was particularly widespread[43]{See: Kolchin, B.A. Novgorodskie drevnosti. Reznoe derevo. Moscow, 1971.}.

The composition of ornament depended on the form and size of that part of the clothing for which the embroidery was intended. Most frequently, as has already been stated, this was bands for edging cloaks and the hems of clothing, belts, for women’s headbands, and as bands of trim; more rarely – as embroidery on chests or shoulders.

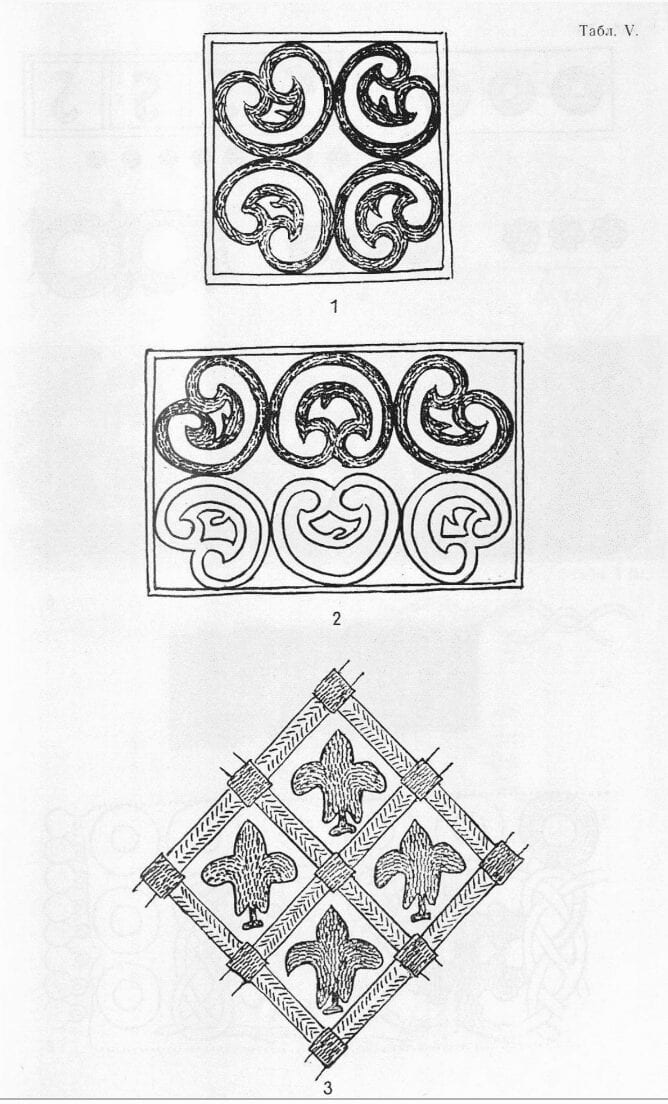

Fragments of embroidery from Chernigov[44]Historical Museum in Chernigov. allows us to reconstruct two compositions of identical motifs, intended for two details on clothing: one in the form of a square, and one of an elongated rectangle. The square embroidery has a centralized composition. It is made up of four identical motifs oriented toward the center (table V, illus. 1). A symmetrical arrangement of the same motif forms an elongated rectangle (table V, illus. 2).

An example of an unending motif which could be repeated infinitely in any direction (table V, illus. 3) is a latticework composition of an embroidery from Romashki[45]State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-2263.. Fleurs-de-lis, embroidered along the shape of the design, are enclosed in diamonds, which are filled out in stem stitch. We find an analogous composition on the clothing of Tsar Nikifor and Tsaritsa Maria in a manuscript compilation of works by St. John Chrysostom (1078-1081)[46]Lazarev, V.N. Istorija vizantijskoj zhivopisi. Vol. 2. Moscow, 1948, tables 138, 139. and in the ornament of the Miscellany of Svjatoslav of 1073[47]Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1, p. 103..

Two types of composition are used for embroidery on bands of different lengths and widths. The principal difference between these lies in that the first type is made up of repeated, separate motifs or elements; in the second, a continuous unending ornament.

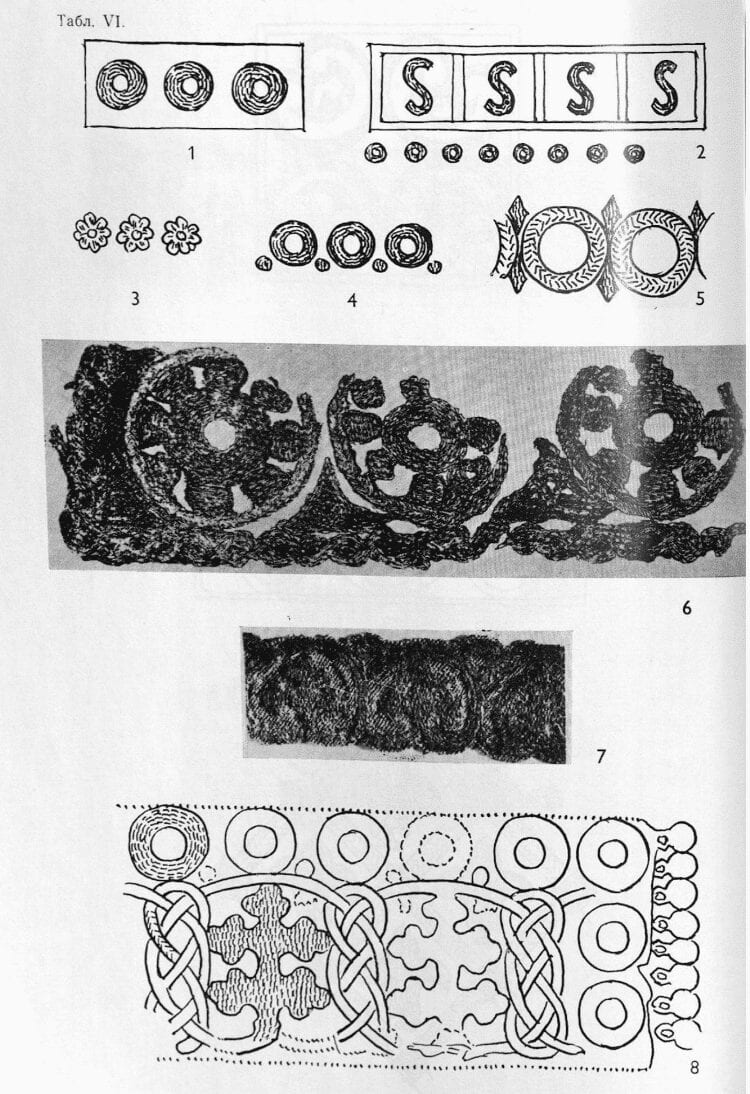

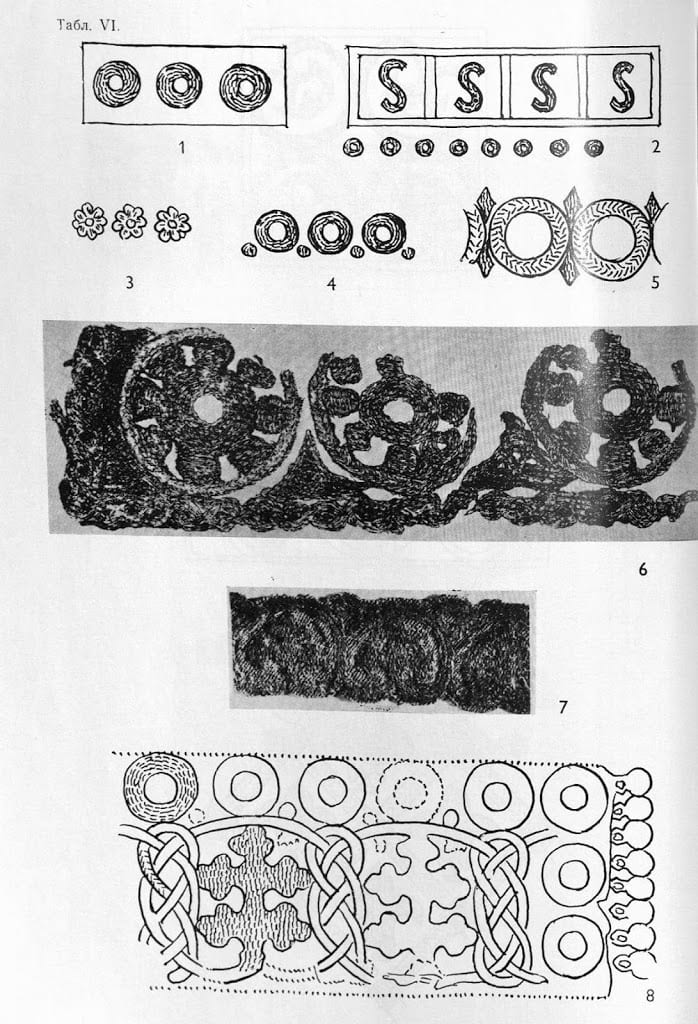

The first type of composition is simpler and more common. Its elements are placed either at a given distance from each other (table VI, illus. 1) or immediately next to each other (table VI, illus. 3), sometimes almost merging in their contours (table VI, illus. 7). Non-contiguous elements sometimes are sometimes framed, for example, in a 10th century embroidery from the Troitskij burial mound in Chernigovschina[48]State Historical Museum in Moscow, exposition of the Department of Feudalism. (table VI, illus. 2). Free space above or below between contiguous elements are often filled with dots, circles, triangles, et.al. (table VI, illus. 4-5). An embroidery from the village of Ochakovo[49]Geze, V.S. “Raskopki na gorodische ‘Ochakov’ u derevni Nabutovo.” Arkheologicheskaja letopis’ Juzhnoj Rossii. 1904 (3), illus. 5., bordered with a simple braid (table VI, illus. 6), represents a relatively complex example of this variant. A particularly complicated variant of this composition is seen in illus. 7 (table VI), an embroidery from Ochakovo[50]Spitsyn, A.A. “Nabutovskij mogil’nik.” Zapiski otdela russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii imperatorskovo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. II, illus. 101., where the contours of the framing around the crosses, interlaced figure eights, turn into a braid. This embroidery is like an intermediate link between the first and second types under consideration.

The second type of composition has 3 variants. The first is formed from wavy lines with with symmetrical shoots emerging above and below. The second is composed with the aid of broken, crossing and relatively wide bands. The third is a typical unending braid.

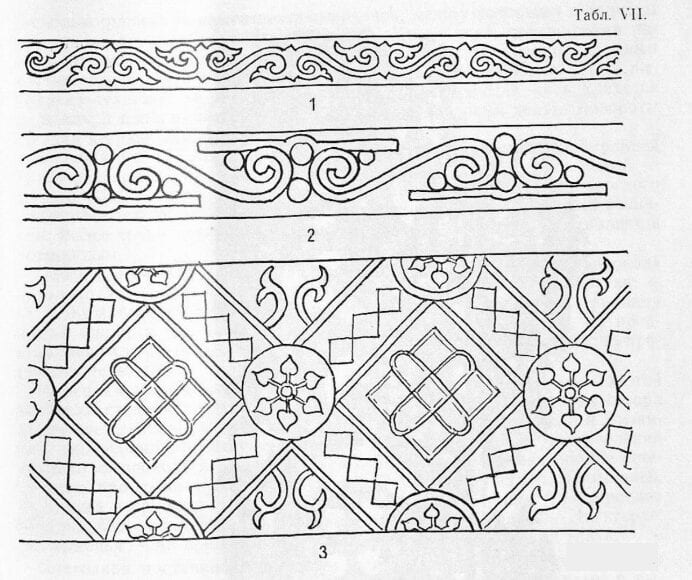

As an example of the first variant of this type, we have the embroidery of two headbands. One of these was found on the head of a young woman in a 12th century grave from Starij Galich[51]Pasternak, Ja. Starij Galich. Krakiv-L’viv. 1944, illus. 45. Located in the historical museum in Lvov.. The band is 2.6 cm wide and 31 cm long. The second headband comes from a treasure hoard found in 1904 in the Mikhailovsky monastery in Kiev[52]State Historical Museum in Moscow, OP-1091, no. 71. See: Archelogicheskaja letopis’ Juzhnoj Rusi, 1903, table XVI, Illus. 3. Otchet Arkheologicheskoj komissii, 1903, illus. 350.. On the first headband, all lines of the design are done in solid, gold lines (table VII, illus. 1) with strokes of silk thread; the second (table VII, illus. 2) has only the outlines of the design, decorated with hemispheres, are drawn.

Analogous compositions of ornament were widespread on various forms of decorative artwork of the same time, for example, in the Nedel’nij (Arkhangelsk) Gospel found in 1902[53]Stasov, V.V. Slavjanskij i vostochnij ornament. Table CXXIV., on silver bracelets[54]Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Vol. 1, illus. 89; Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1, p. 272., on the clothing of Novgorod Prince Jaroslav (see the fresco in the Savior Church on the Nereditsa)[55]Prokhorov, V. Russkie drevnosti. Issue IV, St. Petersburg, 1871, p. 44., and finally, on Varlaam of Khutyn’s embroidered cuffs from the 12th century.[56]Novgorod Historical-Archeological Museum-Reserve, inv. no. 1624. {Svirin, A.N. Ukaz. soch. Table XXIX, illus. 6.}

As examples of the second variant of this type, we have two embroideries. The first is a 11-12th century item from Shargorod (table IV). Its diamonds are formed by two rows of intertwined bands which bend at an angle above and below. A second embroidery from the village of Zhezhavy[57]Historical museum in L’vov., which according to archeological data dates to 900-1100. This item, as an exception to the norm, is overside couched[58]This embroidery technique characteristically has metallic threads laid over the top of the fabric, and attached to it by small stitches of non-metallic thread which pass through the fabric.. Its diamonds are formed by wide, ornamented bands (table VII, illus. 3); rosettes are placed on the edges of the diamonds. A significantly simplified analogy to this embroidery is found on an embroidery from Staraja Rjazan’.[59]Guschin, A.S. Ukaz. soch. Table XXIX, illus. 6.

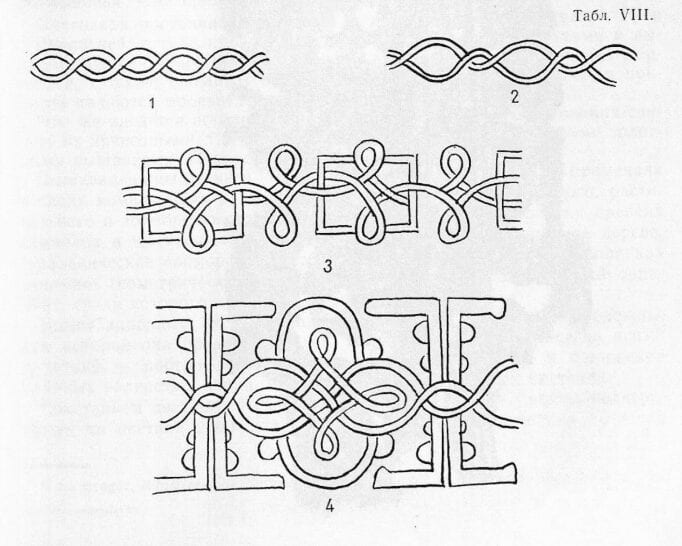

The third variant is made from various kinds of interwoven, narrow, wavy “bands”. For this type, it’s necessary to note that in all cases, even when the braids were extremely complex, the artisan always carefully delineated each of the bands. The simplest braids are composed of an endless row of united circles or ovals, sometimes joined by knots. The most complex are enriched by additional motifs of braids and straight broken lines.

On the embroidered item from Shargorod[60]State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-2653., part of the ornament is woven into square frames (table VIII, illus. 3), thanks to which, despite the continuity of the braid, it achieves a repetition of two different motifs. A detailed study of a poorly preserved fragment of embroidery, also from Shargorod[61]ibid., inv. no. S-57122., made it possible to reconstruct the relatively complex composition of its design (table VIII, illus. 4).

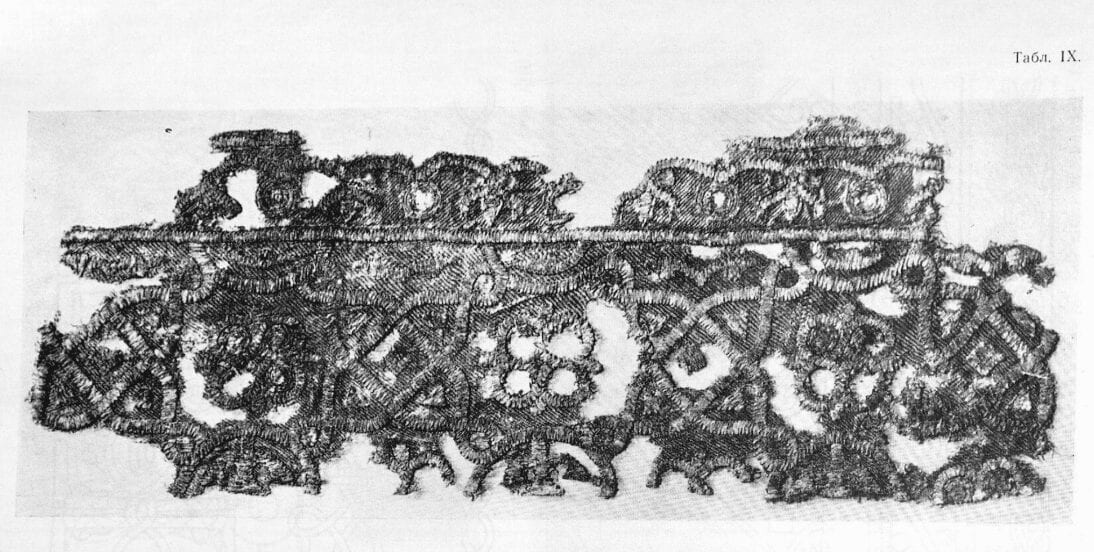

A 12th century embroidery from Chersonesus (table IX)[62]Chersonesus Historic-Archeological Museum, inv. no. 6292. has a relatively complex design. Its “bands” in an unending braid create several different ornamental motifs, between which are located rosettes from 2 interlaced figure eights. In addition, this wide band is framed above and below by a narrow border, the pattern of which is turned to one side. This embroidery, like the one from Zhezhavy, is also overside couched, and has the metallic thread laid not along the length of the design, but across its width; it passes back and forth from one edge to the other, where it is couched to the fabric.

Summarizing what has been said, it follows to note that the earliest of the embroideries we’ve looked at was dated to the 10th century, and the latest to the 13th. Later data are tied to the sack by the Tatar invasion of the same villages from which some of the embroideries we have studied originated. It’s nearly impossible to date these items any more precisely.

As has been said, nearly all the works were embroidered in the “pierced” manner [with the gold thread passing through the fabric], and only two using couching: one from Chersonesus, and the other from Zhezhavy in the Ternopolskij region. The “pierced” technique is similar to that used for embroidery with silk thread, but is inconvenient because it is difficult to pull the gold thread through the fabric without damaging it.

The German researcher M. Dreger, characterizing the technique of goldwork throughout the Middle Ages, emphasizes that almost all older northern goldwork was done using the “pierced” technique, while southern lands, such as Byzantium, typically used the couching technique.[63]Dreger, M. Künstlerische Entwicklung der Weberei und Stickerei. Vienna, 1904, p. 199. This commonality in the use of the “piercing” technique in Kievan Rus’ and northern countries is quite naturally tied to the close relations Kievan Rus’ had with Norway, Germany, France, and other lands, particularly through the female line. For example, Jaroslav the Wise was married to the daughter of Norwegian king Olaf, Ingegerd, and his sons to representatives of the German feudal aristocracy.

Thanks to permanent trade and military ties between Kievan Rus’ and Byzantium, embroidery items were brought from there, along with luxurious fabrics. It is possible that the embroidery from Zhezhavy, and especially that from Chersonesus with the more complex designs and worked in couching, were likely works of Byzantine artisans.

As for the remaining items of embroidery, there is no reason to think that they were imported, as Russian women were famed for their goldwork embroidery. It is no wonder that the Chronicles mention them.

The embroideresses of Medieval Rus’ skillfully and tastefully used various geometric, floral and zoomorphic motifs in their compositions, frequently preserving remnants of ancient symbols and motifs, such as swastikas, posettes, the tree of life, and heraldic zoomorphic compositions. Geometric and strongly stylized floral ornament plays a large role, in particular the fleur-de-lis design.

Compositional schemes of embroidery obey the part of clothing that they were intended for. The rhythm of composition, always clear and crisp, could be based on smooth or uniformly rising and falling wavy lines, or on endlessly twisting braids.

As a combination of the colored base fabric with gold or silver designs, sometimes emphasized by threads of colored silk or pearls, goldwork embroidery completely satisfied the medieval Russian artist’s need for color and contrast.

The examples of ornament presented here testify to the generality of embroidery techniques, as well as the particular character of ornament in different artistic centers of medieval Rus’: Kiev, Chernigov, L’vov, Vladimir on the Kljazma, Novgorod, Staraja Rjazan’, Nizhnij Novgorod, and other cities. Aside from this, the analogies presented here speak to the unity of ornamental style in embroidery and other different techniques of decorative art of medieval Rus’.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | {M.A. Novitskaja’s articles “Haptuvannja v Kyiv’skij Rusi. (Za materialamy rozkopok na terytorii URSR).” Arkhelogija XVIII, Kiev, 1965, pp. 24-38 and “Dav’norus’ke haptuvannja z figurymy zobrazhennjamy.” Arkheologija XXIV, Kiev, 1970, pp. 88-99, were published posthumously.} This and later notes in curly braces were made by V.G. Putsko, who prepared this article for publication. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstvo Novgoroda. Moscow/Leningrad, 1947, p. 129. |

| ↟3 | Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej [PSRL]. Vol 2, Issue 3. St. Petersburg, 1843, p. 27. |

| ↟4 | Embroidered fabric which decorated the Holy Throne or Altar. |

| ↟5 | PSRL, Vol 2, Issue 3, p. 223. |

| ↟6 | ibid., p. 127. Porty. Secular clothing were often seen in churches, as it was custom for princes to donate them to the church “in their own memory”. PSRL, Book 1, Issue 2, pp. 418, 463. |

| ↟7 | Russkie drevnosti v pamjatnikakh iskusstva. Issue VI. St. Petersburg, 1890, p. 91. {In the opinion of N.N. Voronin, the Chronicle is referring to the northern “golden gate” and the southern gate of the cathedral doors, between which in two “wonderous rows” were suspended the fabrics of the cathedral sacristy. Voronin, N.N. Vladimir, Bogoljubovo, Suzdal’, Juriev-Pol’skoj. 2nd ed. Moscow, 1965, p. 47.} |

| ↟8 | PSRL, Vol. 1, Issue 3, p. 445. |

| ↟9 | Kresal’nyj, M.I. Sofijskij zapovednik v Kieve. Kiev, 1960, illus. 102, 103. {Lazarev, V.N. “Gruppovoj portret semejstva Jaroslava.” Russkaja srednevekovaja zhivopis’. Moscow, 1970, pp. 27-54.} |

| ↟10 | Bobrinskij, A. Kievskie miniatjury XI v. i portret knjazja Jaroslava Izjaslavicha v psaltyre Egberta, arkhiepiskopa Trirskogo. St. Petersburg, 1902, pp. 11, 12, 15. {Lazarev, V.N. “Iskusstvo srednevekovoj Rusi i Zapad (XI-XV vv.)” XIII Mezhdunarodnyj kongress istoricheskikh nauk. Moscow, 1970, pp. 29-31, with lit. on p. 60; Logvin, G.N. “Miniatjury drevn’ogo kodeksu.” Misetstvo, 1966(6), pp. 14-19.} |

| ↟11 | PSRL, Vol. 1, Issue 3, p. 187. |

| ↟12 | Gerebtzoff, N. Essei sur l’histoire de la civilisation Russe. Paris, 1858, p. 124; Odobesko, A.I. “Vosdukh s vyshitym izobrazheniem polozhenija spasitelja vo grob.” Drevnosti Trudy Moskovskogo Arkheologicheskogo Obschestva, vol 4, Moscow, 1874, p. 7; Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstva Novgoroda. p. 129; {Svirin, A.N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1963, p. 21.} |

| ↟13 | Tatischev, V.I. Istorija Rossijskaja s samykh drevnejshikh vremen. Vol. 3, St. Petersburg, 1774, p. 329; Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstvo Novgoroda, p. 127. |

| ↟14 | Lazarev, V.N. Iskusstvo Novgoroda, p. 127. |

| ↟15 | Georgievskij, V.T. “Drevnerusskoe shit’jo v riznitse Troitse-Sergievoj Lavry.” Svetil’nik. 1914(11-12), p. 5. |

| ↟16 | State Historical Museum in Moscow, State Historical Museum in Kiev, Historical Museum in L’vov, Cherigov Historical Museum, Historical-Archeological Museum in Khersonesus. |

| ↟17 | The color of the silk has been lost; it has all taken on a murky-brown color. |

| ↟18 | It is made from thin, narrow (around 0.3 mm) rows of metal, tightly wrapped around a core thread. [jeb: cf. modern “Japan gold” thread] |

| ↟19 | Spirally-twisted flat wire. [jeb: Gimp, or possibly perl.] |

| ↟20 | Karger, M.K. Arkheologicheskoe issledovanie drevnego Kieva. Kiev, 1950, illus. 95. |

| ↟21 | See Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady, Vol. 1, St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 66. |

| ↟22 | Lily of the field is a motif which came from the East. |

| ↟23 | Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady, Vol. 1, pp. 59, 60; Istorija russkogo iskusstva, vol. 1, Moscow, 1953, p. 271. |

| ↟24 | State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-1783; See Polonskaja, N.D. Istoriko-kul’turnyj atlas po russkoj istorii. Kiev, 1913, table XV, illus. 12; Polonskaja, N.D. “Arkheologicheskie raskopki V.V. Khvojko 1909-10 gg. v mestechke Belgorodka.” Trudy predvaritel’nogo komiteta XV arkheologicheskogo s’ezda. Moscow, 1911, illus. 53. |

| ↟25 | Historical museum in Chernigov. |

| ↟26 | State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-2651. |

| ↟27 | Spytsin, A. “Churkinskij mogil’nik.” Zapiski otdelija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii imperatorskogo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. 5, issue 1, illus 71. |

| ↟28 | State Historical Museum in Moscow, OP-1093. See: –. Otchet Arkheologicheskoj Komissii, 1903, illus. 350. |

| ↟29 | State Historical Museum in Kiev, Inv. no. 1381. |

| ↟30 | ibid., inv. no. V-2310. |

| ↟31 | Stasov, V.V. Slavjanskij i vostochnij ornament po rukopisjam drevnego i novogo vremeni. St. Petersburg, 1886, table XII, illus. 19, 27. |

| ↟32 | ibid., table LIII. |

| ↟33 | Rybakov, B.A. Remeslo drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1948, illus. 56. |

| ↟34 | Buslaev, F.I. Istoricheskij ocherk po russkomu ornamentu v rukopisjakh. Petrograd, 1917, p. 4 (illus 3), 22 (illus. 30); Stasov, V.V. Russkij narodnyj ornament. Issue 1, St. Petersburg, 1872, p. IX. |

| ↟35 | Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Table 1, illus 59, 60; –. Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol 1, p. 250. |

| ↟36 | Istorija kul’tury Drevnej Rusi. vol 2. Moscow/Leningrad, 1951, illus. 213. |

| ↟37 | Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1, pp. 405, 411, 413, 439. |

| ↟38 | {Varger, G.K. Skul’ptura Drevnej Rusi. Vladimir, Bogoljubovo. Moscow, 1969, pp. 288, 290, illus. 217.} |

| ↟39 | {Bobrinskij, A.A. Reznoj kamen’ v Rossii. Issue 1, Moscow, 1916, table 30, illus. 9.} |

| ↟40 | Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi X-XIII vv. Moscow/Leningrad, 1936, illus. on p. 29. |

| ↟41 | Jakunina, L.I. “Fragmenty tkanej iz Staroj Rjazani.” Kratkie soobschenvenija Instituta istorii materialnoj kul’tury. 1947 (XXI), illus. 36/3. |

| ↟42 | State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-1783. See: Trudy predvaritel’nogo komiteta XV arkheologicheskogo s’ezda, table XV, illus. 13. |

| ↟43 | {See: Kolchin, B.A. Novgorodskie drevnosti. Reznoe derevo. Moscow, 1971.} |

| ↟44 | Historical Museum in Chernigov. |

| ↟45 | State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-2263. |

| ↟46 | Lazarev, V.N. Istorija vizantijskoj zhivopisi. Vol. 2. Moscow, 1948, tables 138, 139. |

| ↟47 | Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1, p. 103. |

| ↟48 | State Historical Museum in Moscow, exposition of the Department of Feudalism. |

| ↟49 | Geze, V.S. “Raskopki na gorodische ‘Ochakov’ u derevni Nabutovo.” Arkheologicheskaja letopis’ Juzhnoj Rossii. 1904 (3), illus. 5. |

| ↟50 | Spitsyn, A.A. “Nabutovskij mogil’nik.” Zapiski otdela russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii imperatorskovo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. II, illus. 101. |

| ↟51 | Pasternak, Ja. Starij Galich. Krakiv-L’viv. 1944, illus. 45. Located in the historical museum in Lvov. |

| ↟52 | State Historical Museum in Moscow, OP-1091, no. 71. See: Archelogicheskaja letopis’ Juzhnoj Rusi, 1903, table XVI, Illus. 3. Otchet Arkheologicheskoj komissii, 1903, illus. 350. |

| ↟53 | Stasov, V.V. Slavjanskij i vostochnij ornament. Table CXXIV. |

| ↟54 | Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Vol. 1, illus. 89; Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1, p. 272. |

| ↟55 | Prokhorov, V. Russkie drevnosti. Issue IV, St. Petersburg, 1871, p. 44. |

| ↟56 | Novgorod Historical-Archeological Museum-Reserve, inv. no. 1624. {Svirin, A.N. Ukaz. soch. Table XXIX, illus. 6.} |

| ↟57 | Historical museum in L’vov. |

| ↟58 | This embroidery technique characteristically has metallic threads laid over the top of the fabric, and attached to it by small stitches of non-metallic thread which pass through the fabric. |

| ↟59 | Guschin, A.S. Ukaz. soch. Table XXIX, illus. 6. |

| ↟60 | State Historical Museum in Kiev, inv. no. V-2653. |

| ↟61 | ibid., inv. no. S-57122. |

| ↟62 | Chersonesus Historic-Archeological Museum, inv. no. 6292. |

| ↟63 | Dreger, M. Künstlerische Entwicklung der Weberei und Stickerei. Vienna, 1904, p. 199. |

One Reply to “Goldwork Embroidery of Kievan Rus’”