The first time I saw a picture of the Puchezh Epitaphios, still quite brightly hot pink despite being almost 600 years old, I was intrigued and wanted to know more. The article I’ve translated here (Петров, А.С. “Пучежская плащаница 1441 года и новгородское шитьё времени архиепископа Евфимия II.” Новгород и новгородская земля. Искусство и реставрация. Issue 4. Velikij Novgorod, 2001, pp.226-240) discusses this item, an embroidered liturgical veil created in 1441 in Novgorod, and several other items from that timeframe. In particular, it was interesting to me to read here about the ties between Novgorod and Western European art, notably opus anglicanum.

The Puchezh Epitaphios of 1441 and Novgorodian Embroidery at the Time of Archbishop Euphimius II, by A.S. Petrov

A translation of Петров, А.С. “Пучежская плащаница 1441 года и новгородское шитьё времени архиепископа Евфимия II.” Новгород и новгородская земля. Искусство и реставрация. Issue 4. Velikij Novgorod, 2001, pp.226-240.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[Where possible, I’ve replaced the black and white photos in the original article with color photos.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here online.]

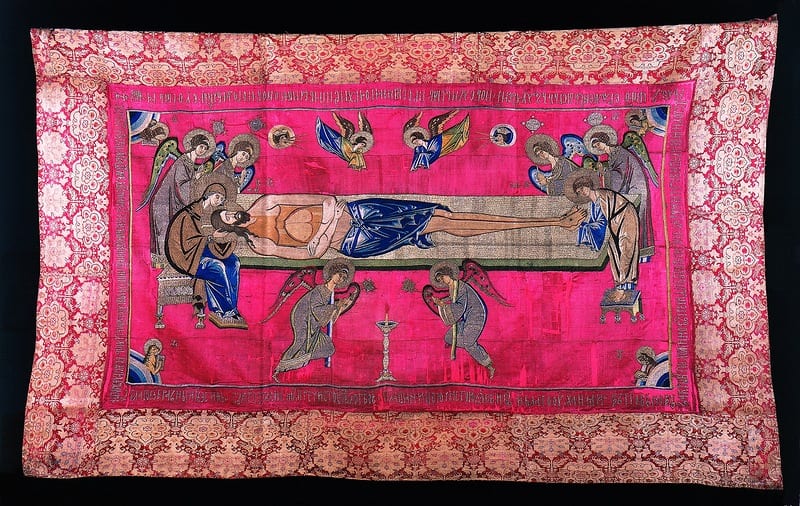

We do not always pay attention to the anniversaries in the life of works of art; and yet, the very subject of this article[1]The author would like to thank E.S. Smirnova and A.S. Preobrazhenskij, leaders of a seminar on medieval Russian art in the Department of History at Moscow State University im. M.V. Lomonosova, and also all its participants for their valuable advice on the preparation of this article. Special appreciation to the staff of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin, in particular, A.L. Batalov and T.D. Panovaja who participated in a discussion of this text at a scientific colloquium on April 1, 2011. Thanks as well to A.V. Silkin and I.A. Sterligova for their consultation. is to remember that this year marks a symbolic date – the 570th anniversary of the completion of the so-called Puchezh Epitaphios in the collection of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin, one of the most important monuments in the history of Novgorodian embroidery (illus. 1). Information about its age and patron are seen on the embroidered inscription on the upper edge: “In the year 6949 [1441] the creation of this veil: was ordered: by the venerable archbishop of Novgorod the Great, Lord Euphemius. Amen.“[2]For the text of all inscriptions and other data, see: Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo: Katalog. Moscow, 2004, catalog item 7, pp. 90-93. The special significance of this inscription lies in that, here before us, is the first ecclesiastical embroidery which we know with certainty was created in Novgorod. After all, despite the fact that practically all items of Russian ecclesiastical embroidery from the period of the 12th-15th centuries are tied to Novgorod, dating them and determining their region of manufacture retains some degree of suspicion[3]This includes: a “podea” dated by researchers to the turn of the 11th-12th century with a composition of the Crucifixion in the State Historical Museum (see Lifshits, L.I. “Pelena s ‘raspjatiem’ i izobrazhenijami Khrista, Bogomateri Voploschenie i apostolov na poljakh.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 2010, pp. 39-48); a 13th century (?) double-sided gonfalon depicting the archangels and 13th century (?) veils depicting Christ, the Holy Virgin, the apostles and the Evangelists – all in the collection of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin (about these items, see: Sterligova, I.A. “Novye svedenija o drevnejshikh shitykh pelenakh iz Muzeja-zapovednika ‘Moskovskij Kreml’.'” ibid., pp. 49-58); the so-called “cuffs of Varlaam of Khutyn” with figures of the Deësis from the 12th-13th centuries, a 14th century altar podea(?) with the Deësis and Evangelists, and a 14th century (?) epitrachelion with images of saints – all in the collection of the Novgorod Museum-Reserve (Ignashina, E.V. Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe i litsevoe shit’jo v sobranii Novgorodskogo muzeja: Katalog. Velikij Novgorod, 2003, catalog items 2, 5, 6). Exceptions from this list include the “veil” of Maria Tverskaja from 1389 (Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971, pp. 10-11, tables 5, 6) and certain archeological finds, such as the fragments of a 12th-13th century epitrachelion from a dig near Kiev’s St. Sophia cathedral.. This is partly due to our relatively weak ability to correlate them with monuments of Novgorod iconography and applied art, and partly due to their rarity and the corresponding difficulty of combining them into groups by characteristic artistic and technical features, that, in turn, we are unable to draw a harmonious line of development — each of these monuments remains separate and unique. Thus, information about the creation of this monumental epitaphios in 1441 marks not only a formal starting point in the history of Novgorodian embroidery: beginning with this work, we can trace a consistent evolution of ecclesiastical embroidery in Novgorod the Great in the 15-16th centuries, right up to the fall of Novgorod to the Oprichnina in 1570, which had such a catastrophic effect on its culture.

[Color image obtained online here.]

It is important to note the meaning of this epitaphios for our evaluation of Novgorod art of that time as a whole. This period in the history of the culture of Novgorod the Great, when Archbishop Euphemius occupied the pulpit, was characterized by a rich artistic life. This was when several dozen churches were built and registered, when the royal court was rebuilt, when the clock-tower was built, when the sacristy and decoration of icons in the Cathedral of St. Sophia were replenished; but, not one of the monuments which survive from that time carries the seal of such high artistry as this work of Euphemius’ embroiderers. In it, we witness not only an intensity of accomplishment, but also a significant height of creative achievement[4]E.A. Gordchenko noted the low quality of construction work by the Euphemian masters (Gordchenko, E.A. Vladychnaja palata novgorodskogo kremlja. Leningrad, 1991, p. 18). According to T.Ju. Tsarevskaja, several recently discovered remants of murals found in the Lord’s chamber also speak to this (Tsarjevskaja, T.Ju. “O Novgorodskoj stenopisi vremeni arkhepiskopa Evfimija II.” Novgorod i Novgorodskaja zemlja. Iskusstvo i restavratsija. Issue 3. Velikij Novgorod, 2009, p. 68.). It is not by coincidence that E.S. Smirnova reviewed this item in the context of the development of Novgorod iconography of the 15th century as a whole, thus presenting it as a valuable monument of visual art[5]See: Smirnova, E.S., V.K. Laurina, E.A. Gordchenko. Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda XV vek. Moscow, 1982, pp. 78-81. Unfortunately, in modern study, the appeal of embroidery to researchers of iconography relates predominantly to the study of iconographic analogies, while as a rule, the artistic features and merits of the embroidered works themselves are ignored.. Obviously, this is due to the fact that, from the extended – almost 30 year long – rule of St. Euphemius (1429-1458), frescos are preserved only in insignificant fragments, and the number of icons indisputably tied to this period are limited in number[6]Tsarjevskaja, O Novgorodskoj stenopisi…, 2009, pp. 61-76; Smirnova, E.S., et.al. Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda…, 1982, p. 75.. This embroidered work, the cartoon of which was famously designed by icon painters, partly accounts for our knowledge about painting at this time. The subject of this article is the historical and artistic analysis of this epitaphios, as well as the a review and clarification of works similar to it.

The commonly seen name for this shroud, “Puchezhskaja”, comes from the name of the village of Puchezh, where it was discovered[7]True merit for the discovery of this item belongs to N.N. Pomerantsev who, even before the epitaphios was transferred to the museum collection, provided photographs of the subject and thereby introduced it to scientific study. in the Church of the Resurrection of Christ on the Pushavka River, now destroyed and hidden beneath the waters of the Gorky reservoir[8]Svod pamjatnikov arkhitektury i monumental’nogo iskusstva Rossii. Ivanovskaja oblast’. Part 3. Moscow, 2000, pp. 113-114.. According to the inscription in the vestibule, the church, which was located on the site of the ancient Pushavka Monastery, was built by the faith of Novgorod’s leader Iov (died, 1716), who was born in the nearby village of Katunki. The relocation of the epitaphios to Puchezh was tied, according to N.N. Pomerantsevyj, to Metropolitan Iov and occured around the time of the church’s construction, which was completed in 1717[9]Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, catalog item 7, p. 90, example 3.. The shroud’s original location is not mentioned in the donor rolls, but N.A. Majasova was of the opinion that it was created at Vjazhischskij Monastery, a particular favorite of St. Euphemius[10]ibid., p. 93. N.A. Majasova writes that this was also proposed by E.S. Smirnovaja, but does not provide a citation.. This suggestion is supported by looking at several key contemporaneous events in the history of the decoration of the monastery. In 1438, the monastery’s church in honor of St. Nikolaj the Miracle-worker was built[11]Antipov, I.V. Novgorodskaja arkhitektura vremeni arkhepiskopov Evfimija II I Iony Otenskogo. Moscow, 2009, catalog item 13, pp. 206-208. Meanwhile, the reconstruction of St. Nikolaj’s church dates to 1438; the previous church was founded in 1436 (ibid., catalog item 10, p. 205), but collapsed less than a year later.; in 1441, the church was painted[12]Novgorodskaja pervaja letopis’ (NPL), p. 421.. At first glance, this data allows us a convincing hypothesis that it could have originated at Vjazhischskij Monastery. However, the Inventory of Novgorod from 1617 does not mention even a single epitaphios among the monastery’s possessions[13]Janina, V.L., ed. “Opis’ Novgoroda 1617 goda.” Pamjatniki otechestvennoj istorii. 1984 (3), part 1, pp. 93-94.. In the Inventory of the Vjazhischskij Monastery of 1698, which we were able to read thanks to the assistance of I.Ju. Ankudinov, the epitaphios is also not mentioned — accordingly, it is unlikely that Metropolitan Iov acquired it from this Novgorod monastery. As a result, the problem of its origin once again becomes relevant.

We again recall that Lord Euphemius’ building and restoration efforts were on an unprecedented scale; as was written by Pachomius the Serb at that time, “He began to care for God’s churches, renewing some and founding others anew, approving not only one or two, but a great multitude.”[14]”Povest’ o Evfimie, arkhepiskope novgorodskom.” Pamjatniki starinnoj russkoj literatury. 1862 (4), p. 19. The coincidence of the year when the epitaphios was completed and the painting of the monastery church, given the abundance of church-building activities, could be completely random. In the late 1430s, Novgorod’s Cathedral of St. Sophia was in dire need of care. In 1438, the Deesis row for what was perhaps the first iconostasis in Sophia’s history was painted by the monk Aaron[15]Ikony Velikogo Novgoroda XI-nachala XVI veka. Moscow, 2008, catalog items 23-27.. In 1439, the cathedral walls were painted white-washed with lime and decorated with the tombs of the princes, which were relocated to that spot. As E.S. Smirnova has noted, these extensive renovations in St. Sophia and the glorification of the Novgorod saints led by Lord Euphemius led to wonderful events in the life of the church, in particular, the aforementioned monk Aaron’s vision of the Novgorod saints in 1438[16]Smirnova, E.S. “Ikony 1438 goda v Sofijskom sobore v Novgorode.” Pamjatniki kul’tury. Novye otkrytija. [PKNO] 1977. Moscow, 1977, pp. 215-216; Ikony Velikovo Novgoroda…, p. 260.. Undoubtedly there was also significant update and replenishment of the items in the cathedral sacristy at that time. Unfortunately, the Chronicle does not provide us with any information about any orders for precious decorations for the cathedral, for while the Novgorod Chronicles speak frequently about the construction and painting of temples at the prince’s command, they are completely silent about the contributions of items for the Holy Service[17]An exception is a mention of a donation of silver liturgical “utensils” to the Church of the Transfiguration. (NPL, p. 422). Meanwhile, an inscription on a golden chalice from 1669 in the collection of the Moscow Kremlin Museum mentions that this service item was created from a melted-down chalice which was donated to St. Sophia’s in 1438-1439, a gift of exceptional expense and rarity in medieval Rus'[18]See: Sterligova, I.A., ed. Dekorativno-prikladnoe iskusstvo Velikogo Novgoroda: Khudozhestvennyj metall XVI-XVII vekov. Moscow, 2008, catalog item 85. A few years before this, in 1435, Lord Euphemius ordered another valuable contribution: a panagiar [ciborium], stored today in the Novgorod Museum-Reserve (Sterligova, I.A., ed. Dekorativno-prikladnoe iskusstvo Velikogo Novgoroda: Khudozhestvennyj metall XI-XV vekov. Moscow, 1996, catalog item 22).. the wealth of the archbishop’s donations is also attested to by the aforementioned chronicler Pachomius the Serb, who personally knew the saint and included a wonderful passage in his work. After a detailed enumeration, Pachomius glorifies Euphemius on behalf of the temples themselves: “Yea, with a voice, the objects declare their tellingly different beauty;” then, the primary voice is given to the cathedral itself: “I, the Great Cathedral of God’s Wisdom, like the city of the great tsar amidst which I stand, having served many years, am now by my own (Euphemius – A.P.) renewed and decorated with many goods and icons, as indicated by his finger, the words of the objects (our emphasis – A.P.) to him: this is our beauty and the praise of the church due to Euphemius the Great!“[19]”Povest’ o Evfimie…”, p. 19.

It is possible that the Epitaphios of 1441 could have been among the items donated to the church. As N.A. Majasova noted, in medieval Rus’, “the embroidery on the epitaphios would have taken 2 to 3 years.”[20]Majasova, N.A. “K voprosu ob obraztsakh i kopijakh v drevnerusskom litsevom shit’e.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 2010, p. 30. It follows then that it could have been ordered in 1438-1439, years that were important for the decoration of St. Sophia, and then the completion of such a monumental work would have been just in time for the date mentioned in the embroidered inscription. Unfortunately, it’s not possible at this time to confirm this theory based on data from historical sources about the history of St. Sophia’s. The earliest complete inventory for the cathedral is dated to 1725, by which time the epitaphios was already located in Puchezh. Data in the Inventory of Novgorod of 1617 are too generalized; for the cathedral, they only mention “3 shrouds of velvet and satin, embroidered with gold, silver, and silk”[21]”Opis’ Novgoroda 1617 goda…”, p. 30.. It does not mention any further information about their iconography or typology. The surviving excerpts from the Inventory of St. Sophia from 1635-1646 do not mention any shrouds. We are left only to rely on indirect evidence. In 1454, that is, 30 years after the completion of the Puchezh Epitaphios, Moscow’s Prince Vasilij Ivanovich donated to St. Sophia’s a luxuriously-decorated epitaphios[22]Today, this item is stored in the collection of the Novgorod Museum-Reserve. Ignashina, Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe i dekorativnoe shit’jo…, catalog item 8.. Apparently at this time, Novgorod’s primary church already had at least one epitaphios which acquired secondary value relative to the prince’s gift. Another surviving epitaphios from St. Sophia’s was completed in 1711 by Akilina Buturlina “Under Iov, Metropolitan of Novgorod and of Velikie Luki,” according to the embroidered inscription[23]Ignashina, E.V. “Pamjatniki srednevekovogo litsevogo shit’ja iz Sofijskogo sobora.” Novgorodskij istoricheskij sbornik. 2003, 9(19), pp. 396-397.. The donation of this large work (155 x 235 cm in size) could have given the Metropolitan occasion to transfer Euphemius’ epitaphios, which would already have fallen into the category of “old,” to the new church which was built under his purview[24]The testimony of a priest named John Dobrozrakov from a church in Katunki, published in the mid-XIX century, is interesting in this regard. He recalled that in the church, in addition to icons preserved there by Metropolitan Iov, the church “still had an Aër and priestly robes donated by him; but they had been destroyed,” and in “five households of my parish, who consider themselves to be close relatives of Boris (Lord Jov’s nephew – A.S.), there were several ancient icons and fragments, presented to them in memory of Metropolitan Iov…” (“Nechto k popolneniju biografii Novgorodskogo mitropolita Iova.” Strannik. October, 1861, pp. 155-157.).

As another argument of St. Sophia’s being the origin of the 1441 epitaphios, we also have its unusually large size, which surpasses all other medieval Russian shrouds of the 15th century. Its length without including the outer border reaches 205 cm; with the outer border, sewn on 15th century Italian fabric and which, most likely, dates to the same time, is 255 cm. By comparison, the so-called Light Blue Epitaphios from the first half of the 15th century (now in the Sergiev Posad Museum-Reserve) is 183 cm in length; the shroud donated by Dmitrij Shemyaka to Novgorod’s Juriev Monastery (now in the Novgorod Museum-Reserve) is 183 cm; the epitaphios donated by Grand Prince Vasilij II “the Blind” to St. Sophia’s Cathedral (now in the Novgorod Museum-Reserve) is 193 cm; the Khutyn Epitaphios, which duplicates the iconography of the 1441 item, is 183 cm; an epitaphios ordered by Metropolitan Photius, possibly for the Cathedral of the Assumption in the Moscow Kremlin, is 123 cm[25]It is necessary to note that all of these pieces, unlike the Puchezh Epitaphios, have undergone significant repair and restoration, which could have affected their dimensions. However, these changes are unlikely to have been significant.. The resounding size of the Puchezh Epitaphios, more appropriate for a large cathedral than for a monastery church which was relatively small during Euphemius’ reign, also serves as a strong argument that it was most likely created for St. Sophia’s, whose decorations were always of particularly large size. It goes without saying that this hypothesis will need to be verified by other researchers. Its confirmation would allow us to better imagine the decoration of this cathedral of Novgorod the Great in the mid 15th century and to again appreciate the value of this monument.

The Puchezh Epitaphios, as has been mentioned repeatedly, distinguishes itself from earlier works primarily in its use of color, built on resounding color combinations in how the garments and individual details of the composition are constructed: dark blue with light blue and white, dark green with light green and yellow silks. Based on this color scheme, a special group of works has been distinguished, referred to (based on the epitaphios) as the so-called “Euphemius workshop” or “pictorial style”[26]The term “pictorial style” has come to be used with regard to Novgorodian embroidery as a result of its juxtaposition with the icon painting style, as is evident from the frequent use by researchers of the term “space” in relation to the use of the color white in draperies., although it must be noted that nothing is actually known of any such artisan workshop of that time. This “pictorial” style contrasted with the prevailing use at the time of local colors for individual pieces of clothing[27]Svirin, A.N. Pamjatnik zhivopisnogo stilja shit’ja (‘chin’) XV veka v Sergievskom istoriko-khudozhestvennom muzee (b. Troitse-Sergievoj lavry). Komissija. Sergiev Posad: 1926, p. 14., or of work where clothing was only embroidered using gold or silver threads[28]Lazarev, V.N. “Zhivopis’ i skul’ptura Novgoroda.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Moscow, 1954, table 2, pp. 278-279; Svirin, A.N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1963, pp. 33-34..

This color scheme, as has already been noted by researchers, most likely originates from Western European medieval embroidery[29]A.S. Svirin, summing up the comparisons of the “Iconostasis” from the Tretyakovskaya Gallery with medieval Russian paintings, says that its “artistic forms” are related to 14th century Novgorodian art, but makes a general remark that “in absorbing Byzantine elements, Novgorodian art … could not remain free from the influence of the Gothic-European style of that age.” (Svirin, Pamjatnik zhivopisnogo stilja…, p. 13). D.V. Ainalov also writes about the influence of Western European art on the style of the embroidery in question in his work on medieval Russian monumental painting (Ainalov, D.V. Geschichte der russischen Monumentalkunst zw Zeit des Grossfurstentums Moscau. Berlin/Leipzig, 1933, pp. 115-117). Later, V.N. Lazarev, while referencing A.N. Svirin’s opinion, writes that the technique of Euphemian embroidered items can be attributed to “Western sources” (Lazarev, Zhivopis’ i skul’ptura…, p. 278). N.A. Majasova also acknowledges the influence of Western European fabrics – medieval embroidery and tapestry weaving – on Euphemian embroidery (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 16; Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, p. 55).. It is well known that similar color schemes were widely used in English embroidery of the 12th-16th centuries, a style whose manner and technique has long been referred to as “opus anglicanum” (illus. 2, 3)[30]About this technique, c.f.: Christie, A.G.I. English Medieval Embroidery. Cambridge, 1938; King, D. Opus Anglicanum. English Medieval Embroidery. Catalog of an Exhibition, Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1963; Brel-Bordaz, O. Broderies d’ornements liturgiques XIII-XIV siècles (Opus anglicanum). Paris, 1982; Warner, P. “Opus Anglicanum – the technique.” Bulletin CIETA. 2001(78), pp. 41-44.. It’s color style was obviously borrowed by embroiderers from various European countries. It is possible that European embroideries could have reached Novgorod, considering in particular the international economic, diplomatic and cultural ties of the Novgorodians, which intensified during Euphemius’ rule. Exactly which kinds of embroideries, whether English or from other European countries, might have been known to the Novgorod artisans is difficult to say[31]There are quite a few examples of European embroidery in the sacristies of medieval Russian churches. One curious example is an epitrachelion originating from the Pavlo-Obnorskij Monastery and stored now in the Vologda Museum (Rybakov, A.A. Khudozhestvennye pamjatniki Vologdy. Leningrad, 1980, catalog item 74; Obraz svjatitelja Nikolaja v zhivopisi, rukopisnoj i staropechatnoj knige, grafike, melkoj plastike, derevjannoj skul’pture i dekorativno prikladnom iskusstve XIII-XXI vekov. Moscow, 2004, catalog item 340). The figures on it were worked by Russian masters in the 16th century, however, they used Western European embroidery from the 15th-16th centuries as a basis, such that new figures took the place of older ones that were not liked by the customer, either out of preservation, or because of their confessional irrelevance. Moreover, such a juxtaposition of interwoven saints as shown on the vestments, apparently, was not obligatory. This is evidenced by a pre-Revolutionary color photograph taken by S.M. Prokudin-Gorsky in which, along with other ancient vestments from the sacristy of the Tver Monastery and kept at that time in the Tver Museum, there appears an epitrachelion of European work from the late Gothic period (14th-15th centuries) (in its original publication, it was dated to the 13th-14th centuries — Zhiznevskij, A.K. Opisanie Tverskogo muzeja. Arkheologicheskij otdel. Moscow, 1888, p. 126, catalog item 555, no illustration). Apparently, the stole, like most of the embroidered works from the collection of the Tver Museum, disappeared during World War II. Prokudin-Gorsky’s photograph was recently published (see: Katasonova, E. “Ozhivshee vremja. Rossija 1908-1915 godov v fotographijakh S.M. Prokudina-Gorskogo.” Ubrus. 2007 (7), illustration on page 75). It in, in three layers stacked one on the next, there is sewn the figures of saints (at the top is a full-length image of the Holy Mother with the Infant Christ in her arms) under a canopy of tabernacles typical for the Gothic period. One can note the transitions from dark blue to light blue and white in the embroidered clothing and architecture, as well as the transition from green to yellow in the depiction of the grass. The epitrachelion was later trimmed with a border and fringe, and no doubt, was used in monastic worship..

[Color photo obtained online here.]

[Color photo obtained online here.]

And yet although this color scheme, borrowed from European embroideries, became the main distinguishing feature of Euphemian embroidery, it alone does not determine the height of its artistic merit, given how creatively and boldly the Novgorodian masters were able to comprehend this artistic movement. Embraced as some kind of impulse, it was qualitatively reworked by the spirit of the iconographic tradition which was dear to the Novgorodians, and as a result, it received a particular voice and clarity of design, serving not so much the decorative but the spirituality of form.

This additional expressiveness of color allowed the creators’ choice of the scarlet silk as the background of their work. This can likely be considered to be a certain peculiarity of the Novgorodian sense of color. Of course, red backgrounds were also used in Muscovite embroidery, for example in the Epitaphios of Elena Verejskaja of 1466[32]See: Nartsissov, V.V. “Vozdukh, shityj knjaginej Elenoj Verejskoj.” Drevnerusskoe iskusstvko: Issledovanie i attributsii. St. Petersburg, 1997, pp. 212-223; Putsko, V.G. “Plaschanitsa 1466 goda iz Arkhangel’skogo sobora Kremlja.” Ubrus. 2006 (6), pp. 59-71.; however, in other Muscovite shrouds of the first half of the 15th century, we see a clear preference for more refined and discrete combinations of gold and silver thread with light- or dark-blue backgrounds.

The sonorous patches of color on the Puchezh Epitaphios serve as additional structural elements of the composition. It is solidly and symmetrically built, with the center highlighted by the vibrant color of the Savior’s linens, which immediately grab the viewer’s eye, but then causes the eye to shift to Christ’s expressive face, the semantic center of the composition. It’s secretive nature is due to the recurring arcing contours of the inclined figures and the centripetal direction of the diagonal lines which are invisibly indicated by the movement of the four central angels and the symbols of the Evangelists in the four corners. At the same time, everything is subordinated to the figure of Christ, incredibly huge in scale unprecedented in other shrouds, giving a special monumentality to the image.

The Savior’s face (illus. 4) in the Puchezh Epitaphios is distinguished by the subtlety with with the features are worked, and the depth with which the suffering he has experienced are displayed, but not at the expense of solely external mimicry. The inner tragedy of the image is shaded by its restraint and impassivity. At the same time, we point out that the other faces do not carry such a high note as would correspond to the greatness and sorrow of this event. For example, the faces of the Holy Virgin and the angels standing behind her are filled out as if from a single pattern (illus. 5). On their faces, as well the faces of the angels flying near the body of Christ, there is a light, barely noticeable smile. However, this flaw of the minor figures does not detract from the artistic merit of the piece.

Detail: Holy Virgin and Angels

Researchers uniformly attribute the so-called Local Row or Marching Iconostasis, originating from the Moscow region Trinity-Sergiev Monastery and now in the collection of the Tretyakovskaya Gallery (illus. 6)[33]Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 16-17, tables 17, 18., to the Euphemius school. The basis for this initial attribution made by Ju.A. Olsuf’evyj was its iconographic peculiarity: on the extreme far right is depicted the Venerable Euphemius the Great, in whose name the later Novgorodian leader took his vows; on the far left, mirroring the Venerable one, stands the apostle John the Baptist — John was Lord Euphemius’ name before he became a monk[34]Olsuf’ev, Ju.A. K voprosu o shitom deisusnom <<Chine>> (No. 1543). Sergiev, 1924, pp. 7-8.. Further comparison with the Puchezh Epitaphios decisively confirmed this attribution.

Aside from the characteristic use of colored silk, the epitaphios and the embroidered iconostasis from the Tretyakovsky Gallery are also united by use of similar decorative details: the peacock-colored feathers in the angels’ wings, the way the hair is embroidered in curly loops, and the halos edged in a kind of punctured outline. But, we must also note the differences concerning the figurative interpretation of how the presented figures are portrayed. A study of the personages on the Tretyakovsky iconostasis reveals an exquisite subtlety[35]It is necessary to understand the connection between the embroidered images of the iconostasis, and in particular of the central image of the Savior, and the newly discovered fresco from the Euphemian era with an image of Christ Pantocrator from the Lord’s Palace in the Novgorod kremlin. (cf. Tsarevskaja, O novgorodskoj stenopisi…, pp. 72-74, illus. 15a-b.). The images on the iconostasis, as opposed to the Puchezh Epitaphios, have a more complex pattern of folds in their clothing (illus 7). Their peculiarly broken appearance, their predominantly bloated [?], flared figures stylistically closely parallel several figures in the icons of Aaron the Monk from 1438[36]Ikony Velikogo Novgoroda…, catalog items 23-27. As a more distant analogy, the image of St. John Climacus in a miniature from the manuscript “Lestvitsy” can be cited, from the beginning of the 15th century (Novgorod Museum-Reserve, inv. KP-32725-1. Smirnova, E.S. Litsevye rukopisi Velikogo Novgoroda XV vek. Moscow, 1994, catalog item 1, illustration on page 183.).

These differences, however, do not contradict the prevailing opinion that the Iconostasis and the Puchezh Epitaphios were created by the same workshop, and speaks to the fact that the workshop would have had multiple craftsmen and may have employed multiple replacement workers[37]These differences gave rise to some assumptions by researchers regarding the dating of the different works. Thus, as noted by Ju.A. Olsuf’ev, “the epitaphios, due to the severity of its style, should be considered to have been created later than the Iconostasis.” (Olsuf’ev, K voprosu…, p. 8). In our opinion, clear grounds do not exist for dating the iconostasis with regard to the Epitaphios of 1441..

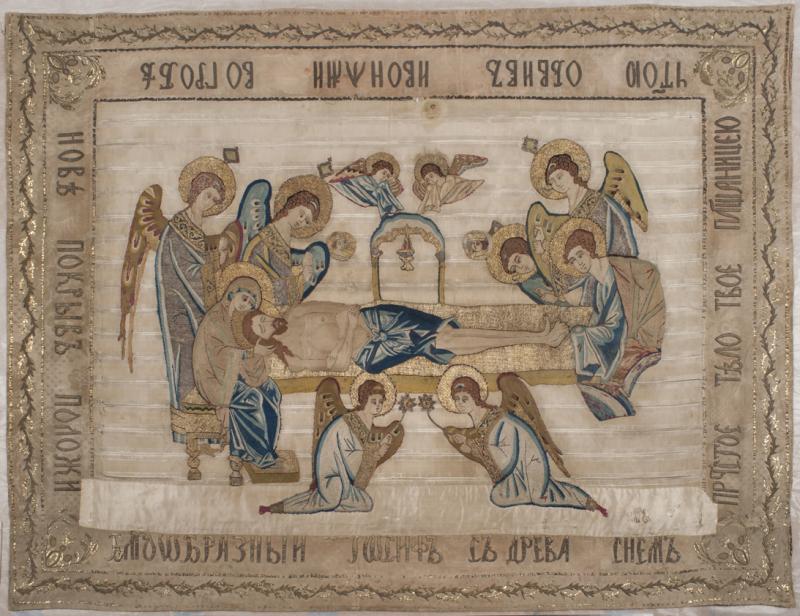

Another work traditionally attributed by researches to the Workshop of Lord Euphemius is an epitaphios from the Khutyn Monastery (illus. 8)[38]Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 16; Smirnova, et.al., Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda…, p. 75; Ignashina, Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe…, catalog item 9 (with full bibliography); Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, p. 93.. Aside from a slight reduction in size and scale, it was noted by researchers that it almost absolutely reproduces both the composition and iconography of the Puchezh Epitaphios[39]Svirin, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 33. See also the previous note..

A comparison of the two embroideries, however, completely contradicts the attribution of the Khutyn shroud to the workshop which filled Euphemius II’s orders. It is apparently more primitive in its cartoon, with a simplification of decorative elements (for example, in the depiction of the angels’ wings), a coarsening of order in figure and meaning, and a weakening of technological skill (illus. 9). The faces are embroidered with rough, thick stitches. In its creation, the embroiderers convey shape by using white as a glare effect, whereas craftsmen [of the Euphemius workshop] do not embroider flare in white, but instead build up the volume through careful use of stitching “in form”, making use of the fact that silk stitches which are laid down in different directions will reflect light differently, creating a subtle, almost imperceptible play of light. The faces on the Khutyn epitaphios are expressive, with the features drawn using contrast with black thread, generally creating a much rougher impression (this is especially visible in the image of the Savior) than the softened faces created through shades of brown on the items from the Euphemius masters. Generally speaking, the body of Christ, which has a more fractional figure, loses the monumental expressiveness achieved in the 1441 epitaphios. The clarity and rigor is also not maintained, compared to the copied item, in the Savior’s loincloth, nor in the rest of the details which are carried out with the noted color combinations.

[Color image obtained online here.]

It is obvious that the [Khutyn] epitaphios from the Novgorod museum, while undoubtedly influenced by the Euphemian work, is the work of artists of a different, altogether lower level of skill. Its technological character and choice of color date this monument to no later than the 15th century[40]This set of technological methods do not find any analogies in the monuments of the 16th century. In addition, in the next century, there appears to have been an obvious preference for more restrained, harmonized colors., but it is still difficult to date this work any more precisely. The Euphemius workshop is also typically attributed as the creator of another epitaphios, this one from the Tikhvin Assumption Monastery and preserved now in the Russian State Museum (illus. 10)[41]Nikolaeva, T.V. “Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva s nadpisjami XV-pervoj chetverti XVI veka.” Arkhelogia SSSR. Svod arkheologicheskikh istochnikov. Issue EI-49. Moscow, 1971, p. 17; Smirnova, et.al., Zhivopis’ Veliokogo Novgoroda…, p. 75; Likhacheva, L.D. “Gruppa novgorodskogo shit’ja XV-pervoj poloviny XVI veka v sobranii Russkogo muzeja.” Gosudarstvennyj Russkij muzej. Drevnerusskoe iskusstvo. Novye attributsii. St. Petersburg, 1994, p. 13; Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, p. 93; –, Sacred Arts and City Life: The Glory of Medieval Novgorod. St. Petersburg, 2005, catalog item 178. My thanks to conservator O.V. Kljukanov of the Russian Museum for his kind assistance with familiarizing me with this work.. But, when compared with the referenced works from the Euphemian workshop – that is, the Puchezh Epitaphios and the Iconostasis from the Tretyakovskaya Gallery – this attribution also does not find confirmation. It is likely that its creators had a sample from the Archbishop’s workshop to look at. However here, as in the Khutyn Epitaphios, the use of color borrowed from Euphemius’ embroiderers are meaningfully simplified by the simplification of the cartoon; in places, the three-colored dark blue/light blue/white bands lie along the figures’ outlines like pre-sewn ribbons. This lack of thoughtfulness and meaning also makes itself felt in the level of iconography. As evidence of this, take how the head of John the Apostle is drawn: a ribbon is woven into his hair and his hairstyle has long strands falling about his neck, decidedly identical to the angels around him. It is possible to imagine that the iconographer and embroiderer did not understand or did not notice that at the foot of the Savior, per tradition, John the Apostle should have been depicted. This epitaphios also dates from the second half of the 15th century, by all appearances.

The color motifs of Euphemian embroidery are also reflected in two more shrouds in the Novgorod State Museum, justly dated to the second half of the 15th century (illus. 11)[42]Ignashina, Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe…, catalog items 10,11., and also in several later works of Moscow production – for example, in a 1561 epitaphios from the workshop of the Staritsky princes.[43]See, for example, the cut of Mary Magdalene’s maphorion on the epitaphios donated in 1561 to the Trinity-Sergiev Monastery (Manushina, T.N. Shit’jo Drevnej Rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1983, catalog item 12, illustration on page 185; Baldin, V.I., T.N. Manushina, Troitse-Sergieva lavra. Arkhitekturnyj ansambl’ i khudozhestvennye kollektsii drevnerusskogo iskusstva XIV-XVII vekov. Moscow, 1996, Illus. 305).

The skills of the Euphemian masters are also echoed in an epitrachelion (illus. 12), located today in a private European collection. Originally published as work by Greek artisans from the turn of the 15th-16th centuries, “made for the Russian market”[44]Byzantium at the Temple Gallery. 50th Anniversary Exhibition 10th March – 30th June 2009. Byzantine Greek and Cretan Icons and Art Objects. London, 2009, catalog item 144., A.S. Preobrazhenskij has since attributed it to the art of Rus’, specifically to that of Novgorod the Great, from the second half of the 15th century[45]My thanks to A.S. Preobrazhenskij, who acquainted me with this item..

As seen from the review above, only two works, the Puchezh Epitaphios and the iconostasis from the Trinity-Sergiev Monastery, can be attributed to the order of Lord Euphemius II. These monuments serve as references, both in terms of their artistic plan and in their attribution to other embroideries with analogous color schemes. Other artistic works, in particular the Khutyn Epitaphios and the Tikhvin Epitaphios which were previously attributed to the same workshop, allow us to trace the earliest history of Novgorodian embroidery, and show not so much a line of development of the Euphemian artists’ style, but rather a reuse, duplication and simplification of already discovered techniques. In this way, other preserved works of Novgorodian 15th-century embroidery attest to the fact that, apparently, this highest level of artistry attained by embroidery of the Euphemius era was not picked up by following generations of artisans.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | The author would like to thank E.S. Smirnova and A.S. Preobrazhenskij, leaders of a seminar on medieval Russian art in the Department of History at Moscow State University im. M.V. Lomonosova, and also all its participants for their valuable advice on the preparation of this article. Special appreciation to the staff of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin, in particular, A.L. Batalov and T.D. Panovaja who participated in a discussion of this text at a scientific colloquium on April 1, 2011. Thanks as well to A.V. Silkin and I.A. Sterligova for their consultation. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | For the text of all inscriptions and other data, see: Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo: Katalog. Moscow, 2004, catalog item 7, pp. 90-93. |

| ↟3 | This includes: a “podea” dated by researchers to the turn of the 11th-12th century with a composition of the Crucifixion in the State Historical Museum (see Lifshits, L.I. “Pelena s ‘raspjatiem’ i izobrazhenijami Khrista, Bogomateri Voploschenie i apostolov na poljakh.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 2010, pp. 39-48); a 13th century (?) double-sided gonfalon depicting the archangels and 13th century (?) veils depicting Christ, the Holy Virgin, the apostles and the Evangelists – all in the collection of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin (about these items, see: Sterligova, I.A. “Novye svedenija o drevnejshikh shitykh pelenakh iz Muzeja-zapovednika ‘Moskovskij Kreml’.'” ibid., pp. 49-58); the so-called “cuffs of Varlaam of Khutyn” with figures of the Deësis from the 12th-13th centuries, a 14th century altar podea(?) with the Deësis and Evangelists, and a 14th century (?) epitrachelion with images of saints – all in the collection of the Novgorod Museum-Reserve (Ignashina, E.V. Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe i litsevoe shit’jo v sobranii Novgorodskogo muzeja: Katalog. Velikij Novgorod, 2003, catalog items 2, 5, 6). Exceptions from this list include the “veil” of Maria Tverskaja from 1389 (Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971, pp. 10-11, tables 5, 6) and certain archeological finds, such as the fragments of a 12th-13th century epitrachelion from a dig near Kiev’s St. Sophia cathedral. |

| ↟4 | E.A. Gordchenko noted the low quality of construction work by the Euphemian masters (Gordchenko, E.A. Vladychnaja palata novgorodskogo kremlja. Leningrad, 1991, p. 18). According to T.Ju. Tsarevskaja, several recently discovered remants of murals found in the Lord’s chamber also speak to this (Tsarjevskaja, T.Ju. “O Novgorodskoj stenopisi vremeni arkhepiskopa Evfimija II.” Novgorod i Novgorodskaja zemlja. Iskusstvo i restavratsija. Issue 3. Velikij Novgorod, 2009, p. 68.) |

| ↟5 | See: Smirnova, E.S., V.K. Laurina, E.A. Gordchenko. Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda XV vek. Moscow, 1982, pp. 78-81. Unfortunately, in modern study, the appeal of embroidery to researchers of iconography relates predominantly to the study of iconographic analogies, while as a rule, the artistic features and merits of the embroidered works themselves are ignored. |

| ↟6 | Tsarjevskaja, O Novgorodskoj stenopisi…, 2009, pp. 61-76; Smirnova, E.S., et.al. Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda…, 1982, p. 75. |

| ↟7 | True merit for the discovery of this item belongs to N.N. Pomerantsev who, even before the epitaphios was transferred to the museum collection, provided photographs of the subject and thereby introduced it to scientific study. |

| ↟8 | Svod pamjatnikov arkhitektury i monumental’nogo iskusstva Rossii. Ivanovskaja oblast’. Part 3. Moscow, 2000, pp. 113-114. |

| ↟9 | Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, catalog item 7, p. 90, example 3. |

| ↟10 | ibid., p. 93. N.A. Majasova writes that this was also proposed by E.S. Smirnovaja, but does not provide a citation. |

| ↟11 | Antipov, I.V. Novgorodskaja arkhitektura vremeni arkhepiskopov Evfimija II I Iony Otenskogo. Moscow, 2009, catalog item 13, pp. 206-208. Meanwhile, the reconstruction of St. Nikolaj’s church dates to 1438; the previous church was founded in 1436 (ibid., catalog item 10, p. 205), but collapsed less than a year later. |

| ↟12 | Novgorodskaja pervaja letopis’ (NPL), p. 421. |

| ↟13 | Janina, V.L., ed. “Opis’ Novgoroda 1617 goda.” Pamjatniki otechestvennoj istorii. 1984 (3), part 1, pp. 93-94. |

| ↟14 | ”Povest’ o Evfimie, arkhepiskope novgorodskom.” Pamjatniki starinnoj russkoj literatury. 1862 (4), p. 19. |

| ↟15 | Ikony Velikogo Novgoroda XI-nachala XVI veka. Moscow, 2008, catalog items 23-27. |

| ↟16 | Smirnova, E.S. “Ikony 1438 goda v Sofijskom sobore v Novgorode.” Pamjatniki kul’tury. Novye otkrytija. [PKNO] 1977. Moscow, 1977, pp. 215-216; Ikony Velikovo Novgoroda…, p. 260. |

| ↟17 | An exception is a mention of a donation of silver liturgical “utensils” to the Church of the Transfiguration. (NPL, p. 422) |

| ↟18 | See: Sterligova, I.A., ed. Dekorativno-prikladnoe iskusstvo Velikogo Novgoroda: Khudozhestvennyj metall XVI-XVII vekov. Moscow, 2008, catalog item 85. A few years before this, in 1435, Lord Euphemius ordered another valuable contribution: a panagiar [ciborium], stored today in the Novgorod Museum-Reserve (Sterligova, I.A., ed. Dekorativno-prikladnoe iskusstvo Velikogo Novgoroda: Khudozhestvennyj metall XI-XV vekov. Moscow, 1996, catalog item 22). |

| ↟19 | ”Povest’ o Evfimie…”, p. 19. |

| ↟20 | Majasova, N.A. “K voprosu ob obraztsakh i kopijakh v drevnerusskom litsevom shit’e.” Tserkovnoe shit’jo v Drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 2010, p. 30. |

| ↟21 | ”Opis’ Novgoroda 1617 goda…”, p. 30. |

| ↟22 | Today, this item is stored in the collection of the Novgorod Museum-Reserve. Ignashina, Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe i dekorativnoe shit’jo…, catalog item 8. |

| ↟23 | Ignashina, E.V. “Pamjatniki srednevekovogo litsevogo shit’ja iz Sofijskogo sobora.” Novgorodskij istoricheskij sbornik. 2003, 9(19), pp. 396-397. |

| ↟24 | The testimony of a priest named John Dobrozrakov from a church in Katunki, published in the mid-XIX century, is interesting in this regard. He recalled that in the church, in addition to icons preserved there by Metropolitan Iov, the church “still had an Aër and priestly robes donated by him; but they had been destroyed,” and in “five households of my parish, who consider themselves to be close relatives of Boris (Lord Jov’s nephew – A.S.), there were several ancient icons and fragments, presented to them in memory of Metropolitan Iov…” (“Nechto k popolneniju biografii Novgorodskogo mitropolita Iova.” Strannik. October, 1861, pp. 155-157.) |

| ↟25 | It is necessary to note that all of these pieces, unlike the Puchezh Epitaphios, have undergone significant repair and restoration, which could have affected their dimensions. However, these changes are unlikely to have been significant. |

| ↟26 | The term “pictorial style” has come to be used with regard to Novgorodian embroidery as a result of its juxtaposition with the icon painting style, as is evident from the frequent use by researchers of the term “space” in relation to the use of the color white in draperies. |

| ↟27 | Svirin, A.N. Pamjatnik zhivopisnogo stilja shit’ja (‘chin’) XV veka v Sergievskom istoriko-khudozhestvennom muzee (b. Troitse-Sergievoj lavry). Komissija. Sergiev Posad: 1926, p. 14. |

| ↟28 | Lazarev, V.N. “Zhivopis’ i skul’ptura Novgoroda.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Moscow, 1954, table 2, pp. 278-279; Svirin, A.N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1963, pp. 33-34. |

| ↟29 | A.S. Svirin, summing up the comparisons of the “Iconostasis” from the Tretyakovskaya Gallery with medieval Russian paintings, says that its “artistic forms” are related to 14th century Novgorodian art, but makes a general remark that “in absorbing Byzantine elements, Novgorodian art … could not remain free from the influence of the Gothic-European style of that age.” (Svirin, Pamjatnik zhivopisnogo stilja…, p. 13). D.V. Ainalov also writes about the influence of Western European art on the style of the embroidery in question in his work on medieval Russian monumental painting (Ainalov, D.V. Geschichte der russischen Monumentalkunst zw Zeit des Grossfurstentums Moscau. Berlin/Leipzig, 1933, pp. 115-117). Later, V.N. Lazarev, while referencing A.N. Svirin’s opinion, writes that the technique of Euphemian embroidered items can be attributed to “Western sources” (Lazarev, Zhivopis’ i skul’ptura…, p. 278). N.A. Majasova also acknowledges the influence of Western European fabrics – medieval embroidery and tapestry weaving – on Euphemian embroidery (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 16; Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, p. 55). |

| ↟30 | About this technique, c.f.: Christie, A.G.I. English Medieval Embroidery. Cambridge, 1938; King, D. Opus Anglicanum. English Medieval Embroidery. Catalog of an Exhibition, Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1963; Brel-Bordaz, O. Broderies d’ornements liturgiques XIII-XIV siècles (Opus anglicanum). Paris, 1982; Warner, P. “Opus Anglicanum – the technique.” Bulletin CIETA. 2001(78), pp. 41-44. |

| ↟31 | There are quite a few examples of European embroidery in the sacristies of medieval Russian churches. One curious example is an epitrachelion originating from the Pavlo-Obnorskij Monastery and stored now in the Vologda Museum (Rybakov, A.A. Khudozhestvennye pamjatniki Vologdy. Leningrad, 1980, catalog item 74; Obraz svjatitelja Nikolaja v zhivopisi, rukopisnoj i staropechatnoj knige, grafike, melkoj plastike, derevjannoj skul’pture i dekorativno prikladnom iskusstve XIII-XXI vekov. Moscow, 2004, catalog item 340). The figures on it were worked by Russian masters in the 16th century, however, they used Western European embroidery from the 15th-16th centuries as a basis, such that new figures took the place of older ones that were not liked by the customer, either out of preservation, or because of their confessional irrelevance. Moreover, such a juxtaposition of interwoven saints as shown on the vestments, apparently, was not obligatory. This is evidenced by a pre-Revolutionary color photograph taken by S.M. Prokudin-Gorsky in which, along with other ancient vestments from the sacristy of the Tver Monastery and kept at that time in the Tver Museum, there appears an epitrachelion of European work from the late Gothic period (14th-15th centuries) (in its original publication, it was dated to the 13th-14th centuries — Zhiznevskij, A.K. Opisanie Tverskogo muzeja. Arkheologicheskij otdel. Moscow, 1888, p. 126, catalog item 555, no illustration). Apparently, the stole, like most of the embroidered works from the collection of the Tver Museum, disappeared during World War II. Prokudin-Gorsky’s photograph was recently published (see: Katasonova, E. “Ozhivshee vremja. Rossija 1908-1915 godov v fotographijakh S.M. Prokudina-Gorskogo.” Ubrus. 2007 (7), illustration on page 75). It in, in three layers stacked one on the next, there is sewn the figures of saints (at the top is a full-length image of the Holy Mother with the Infant Christ in her arms) under a canopy of tabernacles typical for the Gothic period. One can note the transitions from dark blue to light blue and white in the embroidered clothing and architecture, as well as the transition from green to yellow in the depiction of the grass. The epitrachelion was later trimmed with a border and fringe, and no doubt, was used in monastic worship. |

| ↟32 | See: Nartsissov, V.V. “Vozdukh, shityj knjaginej Elenoj Verejskoj.” Drevnerusskoe iskusstvko: Issledovanie i attributsii. St. Petersburg, 1997, pp. 212-223; Putsko, V.G. “Plaschanitsa 1466 goda iz Arkhangel’skogo sobora Kremlja.” Ubrus. 2006 (6), pp. 59-71. |

| ↟33 | Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 16-17, tables 17, 18. |

| ↟34 | Olsuf’ev, Ju.A. K voprosu o shitom deisusnom <<Chine>> (No. 1543). Sergiev, 1924, pp. 7-8. |

| ↟35 | It is necessary to understand the connection between the embroidered images of the iconostasis, and in particular of the central image of the Savior, and the newly discovered fresco from the Euphemian era with an image of Christ Pantocrator from the Lord’s Palace in the Novgorod kremlin. (cf. Tsarevskaja, O novgorodskoj stenopisi…, pp. 72-74, illus. 15a-b.) |

| ↟36 | Ikony Velikogo Novgoroda…, catalog items 23-27. As a more distant analogy, the image of St. John Climacus in a miniature from the manuscript “Lestvitsy” can be cited, from the beginning of the 15th century (Novgorod Museum-Reserve, inv. KP-32725-1. Smirnova, E.S. Litsevye rukopisi Velikogo Novgoroda XV vek. Moscow, 1994, catalog item 1, illustration on page 183.) |

| ↟37 | These differences gave rise to some assumptions by researchers regarding the dating of the different works. Thus, as noted by Ju.A. Olsuf’ev, “the epitaphios, due to the severity of its style, should be considered to have been created later than the Iconostasis.” (Olsuf’ev, K voprosu…, p. 8). In our opinion, clear grounds do not exist for dating the iconostasis with regard to the Epitaphios of 1441. |

| ↟38 | Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 16; Smirnova, et.al., Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda…, p. 75; Ignashina, Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe…, catalog item 9 (with full bibliography); Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, p. 93. |

| ↟39 | Svirin, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 33. See also the previous note. |

| ↟40 | This set of technological methods do not find any analogies in the monuments of the 16th century. In addition, in the next century, there appears to have been an obvious preference for more restrained, harmonized colors. |

| ↟41 | Nikolaeva, T.V. “Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva s nadpisjami XV-pervoj chetverti XVI veka.” Arkhelogia SSSR. Svod arkheologicheskikh istochnikov. Issue EI-49. Moscow, 1971, p. 17; Smirnova, et.al., Zhivopis’ Veliokogo Novgoroda…, p. 75; Likhacheva, L.D. “Gruppa novgorodskogo shit’ja XV-pervoj poloviny XVI veka v sobranii Russkogo muzeja.” Gosudarstvennyj Russkij muzej. Drevnerusskoe iskusstvo. Novye attributsii. St. Petersburg, 1994, p. 13; Majasova, Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo…, p. 93; –, Sacred Arts and City Life: The Glory of Medieval Novgorod. St. Petersburg, 2005, catalog item 178. My thanks to conservator O.V. Kljukanov of the Russian Museum for his kind assistance with familiarizing me with this work. |

| ↟42 | Ignashina, Drevnerusskoe ornamental’noe…, catalog items 10,11. |

| ↟43 | See, for example, the cut of Mary Magdalene’s maphorion on the epitaphios donated in 1561 to the Trinity-Sergiev Monastery (Manushina, T.N. Shit’jo Drevnej Rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1983, catalog item 12, illustration on page 185; Baldin, V.I., T.N. Manushina, Troitse-Sergieva lavra. Arkhitekturnyj ansambl’ i khudozhestvennye kollektsii drevnerusskogo iskusstva XIV-XVII vekov. Moscow, 1996, Illus. 305). |

| ↟44 | Byzantium at the Temple Gallery. 50th Anniversary Exhibition 10th March – 30th June 2009. Byzantine Greek and Cretan Icons and Art Objects. London, 2009, catalog item 144. |

| ↟45 | My thanks to A.S. Preobrazhenskij, who acquainted me with this item. |