I am currently reading and translating a book written in 1906 about a fascinating piece of history, the so-called Egbert Psalter. Also known as the Gertrude Psalter or Trier Psalter, this was a Latin copy of the Book of Psalms created in Germany around 980 for the Archbishop Egbert of Trier. In the 11th century, it became the property of Gertrude of Poland, who later became wife of Grand Prince Izyaslav of Kiev. While in Kiev, she seems to have commissioned a prayer book with a number of Russian/Byzantine illuminations, several of which contain images of Gertrude herself, as well as her son Grand Prince Yaropolk and his wife Kunigunde, daughter of Otto I. This prayer book became attached to the front of the psalter, and provides an interesting glimpse into the western view of the Kievan royal family and dress. The miniatures are believed to have been created in Germany or Poland, and are an interesting mix of Byzantine, Russian, and Ottonian styles.

The current translation includes the book’s plates (one of which was in color), and the first two parts. The first chapter gives some history behind Gertrude and her book, and the second describes each of the illuminations. Parts 3 and 4 will be in a future blog post.

The translation has been interesting, because:

- the book is a scan of a version that was published before Russian orthography was reformed by the Soviets (so it contains letters that no longer exist in Russian (і, ѣ), lots of extra hard-signs (ъ) at the ends of words, and some spellings that look a bit strange to those familiar with modern Russian. I got used to it pretty quickly as there are definite patterns to how these older spellings were reformed into modern Russian, but it was a fun puzzle. Some examples:

- “затѣмъ” instead of “затем”

- “недоумѣніе нѣмецкаго изслѣдователя” instead of “недоумение немецкого исследователя”

- “на головѣ ея” instead of “на голове её“

- “Византійскія” instead of “Византийские“

- “Матѳей” instead of “Матфей”

- the author’s scholarly language is a bit obtuse in spots, especially when he’s introducing new subjects (e.g. the final paragraph in chapter 2). He also assumes his reader is fluent in medieval Latin and Greek, so he provides inscriptions or quotes with no translation. I have taken a stab at guessing what those lines are trying to say, but Google translate was understandably perplexed by most of them.

Depictions of the Russian Royal Family in 11th-century Miniatures (Part I)

A translation of Кондаков, Н.П. Изображения русской княжеской семьи в миниатюрах XI века. Санкт-Петербург, 1906. / Kondakov, N.P. Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i v miniatjurakh XI veka. St. Petersburg, 1906.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here: https://dlib.rsl.ru/viewer/01003735609. ]

Depictions of Prince Yaropolk Izyaslavich in 11th-century Miniatures

Part I – An introduction to the Gertrude Codex

This overview of five Byzantine miniatures, found only recently in the so-called Gertrude Codex, a copy of the Latin Psalter written by order of the Trier archbishop Egbert (977-993) and located in the capital archive (now the Royal Archive) in the city of Cividale in Lombardy, is based in part on notes taken by the author based on the actual manuscript in Autumn 1903, and in part on various historical and archeological references collected for the task of comparative analysis of this monument. As such, the entirety of this review serves as a canvas and material for future study which must be undertaken on the difficult task of resolving questions of everyday Russo-Byzantine archaeology. Study of the complete manuscript of the Psalter was done on the Trier anniversary edition[1]Festschrift d. Gesells. f. n. Forschungen zu Trier. Sauerland, N.V. und A. Haseloff, Der Psalter Erzbischof Egberts von Trier – Codex Gertrudianus in Cividale. Mit 62 Tafeln. Trier, 1901. with sufficient precision, if not completeness, and resulted in a number of positive indications and conclusions which we will briefly list as the basis for further analysis.

The Codex of the Trier Psalter has long been known in archaeological literature, and is included in Kraus’s synchronous tables,[2]Kraus, F.X. Synchronistische Tabellen der chr. Kunstgeschichte. 1880, p. 55. where it is mentioned second only after the Trier Gospel as a monument of art owing their appearance to Egbert’s taste and patronage. The characteristic type of late 10th-century northern German ecclesiastical manuscript is not in itself particularly noteworthy. Of incomparably more interest would be the German enamels of that period, if only their investigation, currently made extremely difficult by their scattering throughout cities of the Rhine and its tributaries, could be supplemented by corresponding publication of those items. But in this case, both sets of material could be set to the side, given that the Psalter itself is so characteristic and is so well known in its various forms as to not require analysis. It is important only to know that this Latin manuscript originated in Trier, in all likelihood around the time of the destruction of the Cathedral of Trier, and reached Poland or Kiev in the hands of a Catholic princess by the name of Gertrude. All of the guesses expressed by Sauderland, who authored a historical study of the manuscript, are too complex to be easily accepted, but there is hardly any need for these conjectures either. Similar manuscripts in that time period, such as the Facial Psalter [Rus. Litsevaja Psaltir’], constituted desktop or, more correctly, prayer books for wealthy and noble people in the East and West. There was a deep divide between East and West at this time, and the Byzantine Facial Psalter attempted to satisfy the main task of divine enlightenment, and to be educational in its miniatures. On the other hand, the Latin illustrations in the Psalter met an exceptionally general requirement of these books, presenting a number of images of sacred persons and various events as required by the customer and scribe. The Egbert Psalter belongs to this class of examples, decorated by a series of iconographic images of various saints, the prophet David, the calligrapher Rodprecht and archbishop Egbert, the book’s recipient. The prayerful character of the Psalter’s illustrations intended for Catholics is associated with, for example, the image of the Apostle Peter in one of the Byzantine miniatures. Related Byzantine illustrations in Greek manuscripts were intended for instructive reflection, while Latin iconic figures of saints in the codex were intended for the prayers which completed readings. The image of the Apostle Peter is presented as an especially prayerful, demanding icon.

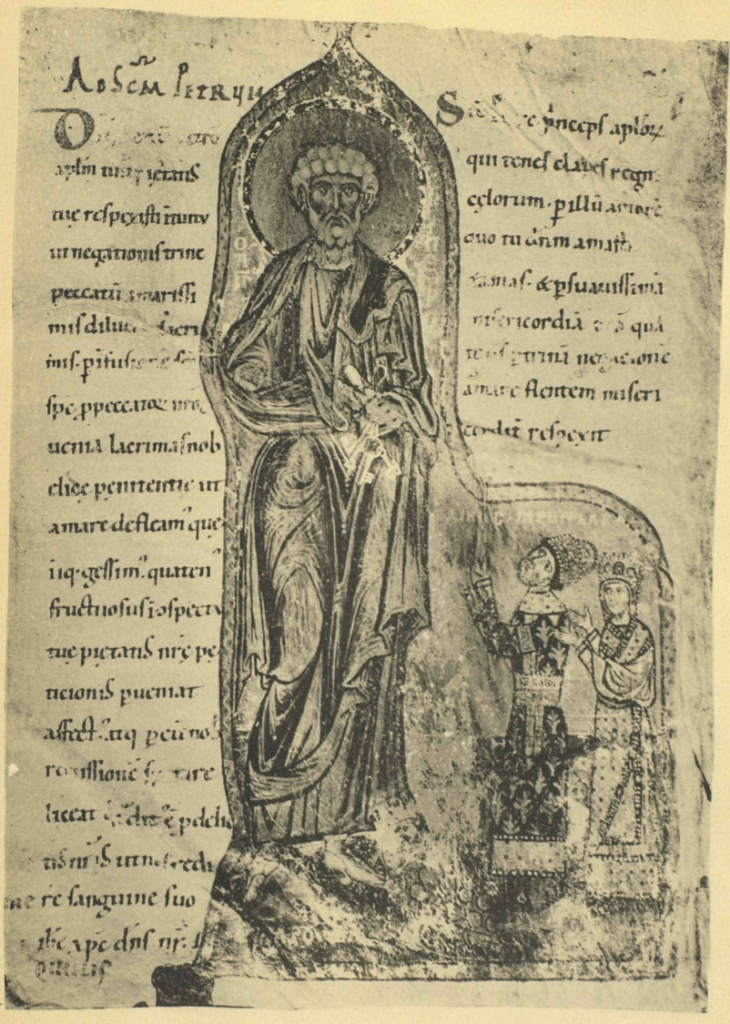

When this Latin Psalter reached the Slavic lands, it received a unique addition in the form of folios which were sewn to the front of the manuscript, and which included a number of miniatures and prayer texts, running from pages 5-18 inclusive of the modern manuscript. This entire part of the manuscript, serving as an preface to the Psalter itself, is filled with various prayers written around the same time in the 11th century and in similar handwriting. The prayers which compose this part of the manuscript were drawn up specifically on behalf of a certain Gertrude, and begin near the depiction (plate 1) of the Apostle Peter, before whom stands a couple: a husband and wife (the husband is named Yaropolk in the inscription), and kneeling at the apostle’s feet is a female figure (identified in the inscription as the mother of Yaropolk). The fifth folio, with which this section of the manuscript (or preface to the Psalter) begins, serves as a blank first page (5a), as happens at the beginning of a manuscript. It is important to note that this and the following six pages represent a single sheet of parchment, folded in half. The parchment of this section differs from that of the rest of the manuscript in its thickness and smoothness. These pages were once larger in size, as can be seen, for example, from the attached plate I, the top and bottom of which have been cut along the margins, judging by the missing parts of the decoration. The pages were once larger in size than the Psalter, and when they were sewn to the Psalter, they were cut down to fit.

Moreover, by looking at the composition of the first two pages, we find that the two prayers written on either side of the Apostle Peter and which are dedicated to him were written after the miniature was painted. A clear indication of this is the appearance of the letter on the left side of the depiction, where the words and lines run right up to the image itself, and only at its edge proceed to the next line, such that the entire written column of this Latin prayer seems to be lined up with a ruler on the left side, while on the right it follows the contours of the painting. On the other hand, the right column, which depends on the same image, has the left edge aligned, but in order to preserve space, the scribe started his letters too close to the image. But, while it is certain that the prayer was scribed after the miniature was painted, there is nothing to rule out that the left prayer was written very much later, or even that it was added for a later owner of the manuscript. The left side prayer mentions the Apostle Peter in the third person;[3]Ad Santum Petrum. Deus qui beatum Petrum, etc. the prayer on the right addresses him in the second person.[4]Sancte Petre, princeps apostolarum, qui tenes, etc. If we imagine this depiction of the Apostle Peter with the penitents before him in its original form, without the prayer texts written on either side and on an otherwise blank page, then this miniature is in the shape of a large Latin letter or capital, and could completely answer the question of the first line of the following page “in me indignam famulam Christi clementer respice,” as the miniature is similar in form to a capital and completely corresponds to the two-letter word “In”. From this we conclude that originally after the miniature there was only written the one short prayer on the right, “Sancte Petre” etc.[5]Sancte Petre, princeps apostolorum, qui tenes claves regni celorum, per illum amorem, quo tu dominum amasti et amas;et per suavissimam misericordiam tuam(?), qua te deus per trinam negacionem amare flentem misericorditer respexit in me indignam famulam Christi clementer respice. / jeb: “Saint Peter, leader of the apostles, you who hold the keys to the kingdom of Heaven, by the love which you master and the art you love, and with your soothing kindness, with which the triple God weeps for the denial of mercy, look favorably upon this worthy servant of Christ.” (???) which was then completed on the following page. The sheet of parchment upon which this miniature was painted, it seems, once existed at the very beginning of a notebook which was sewn from sheets and unbound. It noticeably yellowed and became damaged on the edges and at the fold, and as a result was glued into this spot with strips of parchment to reinforce it. What conclusions can we take from all these meticulous considerations? First and foremost, we can conclude that the owner of these pages, luxuriously decorated with miniatures, was a Catholic, and at the same time was born or grew up in a setting that was familiar with Byzantine art, which was the highest form of art at that time. On the field of the image, the apostle is referred to in Greek Ο άγιος Πέτρος (Gr., “Saint Peter”); the saint praying before him has an inscription in both Greek and Slavonic, and his mother, who prays at the apostle’s feet, is also named in both Greek and Slavonic, but with a mistake, as the word μητήρ (Gr. “mother”) is incorrectly abbreviated in an form which was only used for the name of the Holy Mother: Μ-Ρ.

As such, it appears that the illustrator was familiar with Greek and Latin orthography alike: from this, we can conclude that he was most likely not Greek, but rather was instead either German or a Slav. By creating an initial or final miniature in the form of an initial over an entire page, the illustrator was guided by Western or south-west Slavonic examples. The tracing of the word In has used a Latin or Western form, but in contemporary manuscripts, the Greek lapidary way of writing would have written in in a similar form, much like Ih. As I was informed by Count I.I. Tolstoy, this form of the letter n (with a raised vertical) was used for inscriptions on coins by Basil I and Constantine (869-870), Basil II and Constantine (976-1025) and Constantine Monomachos (1042-1055), and it was only by the time of Issac Komnenos (1057-1059) that on coins, as well as Latin and Greek inscriptions, that this form similar to the Latin h was no longer found, but instead was replaced by N.

The mentioned difference between the two prayers is important specifically because the prayer to the right of the figure of Peter is addressed to him on behalf of one person (and a woman, at that), while the prayer on the left is addressed on behalf of several unidentified persons. If we, in this way, prove the originality of only the short prayer on the right, it would also prove that the use of the figured miniature in the shape of the large capital representing the Latin preposition in was deliberate.

Who was the Catholic woman to whom these pages of prayers belonged, and who, as we learn from further prayers such as on the 6th page, turned to the archangel Michael, praying in her words: “exaudi me miseram pro Petro ad te clamantem,”[6]jeb: “I call to you, praying for Peter” (??) calling for the archangel’s protection for the servant of God Peter. This prayer may refer, according to custom, to a servant of Peter, among the wiles of the Devil, beaten by enemies visible and invisible: “libera Petrum famulum tuum ab insidiis diaboli et ab omnibus inimicis suis visibilibus et invisibilibus.”[7]jeb: “Peter’s servant is free from the snares of the Devil and all enemies visible and invisible.” A prayer to St. Helena, finally, names this penitent one as Gertrude: “intercede pro me famula tua Gertrude ad Dominum Deum ut per crucem Sanctam Domini Nostri ejusque Genitricis intercessionem… Sanctorum omnium nec non perpetuam Successionem mihi famulum tuum Petrum omnemque faciet.”[8]jeb: “Pray for me, your servant Gertrude, to the Lord our God and to the Holy Cross of our Lord, and to his mother, we pray… Thy protection is eternal, and Thy servant Peter follows and will do all.” (???) Further details on folios 8 and 8 obv. in general terms mention the disasters in life of the prayer herself and her son Peter, for whom the mother asks for the Lord’s kindness and mercy. Page 9 obv. displays The Nativity of Christ, a Byzantine miniature. Page 10 shows The Crucifixion. Page 10 obv. displays The Savior, Crowning the Couple. Page 11 contains a fragment about lunar days. Page 12 has a fragment of a carol. Pages 13 and 14 are once again prayers by the same Gertrude.

Of these prayers, the most curious is the one in which Gertrude, turning “to St. Peter for Peter,” confesses his common and even exaggerated sins and vices (these vices are enumerated with such diligence and variety, that this much be some sort of formulaic prayer).

These pages from 7 through 10 (written with 22 lines each) and from 11 to 14 (with 34 lines each) represent two notebooks of sheets folded in two.

Page 15 contains a dedicatory miniature and starts the Psalter proper, which runs uninterrupted for 40 pages, after which there is a fifth miniature depicting The Virgin and Child.

The remainder up to page 203 are comprised of the Latin Psalter. On the page 203, Gertrude’s prayers begin anew, with one addressed to the Blessed Virgin Mary, “for my only son Peter” / pro unico filio meo Petro. This is followed by laetania universalis, then by a prayer to Peter “for the army of my only son Peter” / pro omni exercitu Petri unici filii mei.

On page 213 obv. there is a prayer for her son Peter. The commemoration “to the Pope, our Prince, our Emperor, of our bishops and abbots, and for our relatives, brothers and sisters.” At the end there are two prayers to Archangel Michael and all the Saints for the deceased. As such, from page 203 to 232 we see Gertrude’s prayers as an appendix at the end of the Psalter.

Today, we can almost without a doubt claim that the one who went by the Catholic name Gertrude and who was the owner of this manuscript or, at the very least, of this prayer book was the wife of Grand Prince Izyaslav Yaroslavich and mother of his third son, Yaropolk Izyaslavich. She may have been previously a Polish princess and daughter of Mechislav II or Boleslav the Brave. The Life of St. Anthony in the Patericon tells that, when the Venerable Anthony was forced by the anger of Grand Prince Izyaslav to leave Pechersk for another country, “having heard this, the Princess prayed diligently to the Prince not to drive away his servant of God in anger from his lands, for God’s sake, as had been done when the monks were expelled from her own homeland of Poland. For she was a Polish princess, daughter of Boleslav the Brave.”[9]Bobrinskij, A.A., Count. “Kievskie miniatjuri XI veka i portret knjazja Yaropolka Izyaslavicha v psaltyre Egberta, arkhiepiskopa Trirskogo.” Zapiski Imperatorskogo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo Obschestva. Iss. XII, pp. 351-371. This princess’s son, Yaropolk Izyaslavich, is a prominent figure in the history of Kievan strife over the Grand Prince’s throne. He started out as prince of Vyshgorod, then later was prince of Vladimir-Volynsk. He was evicted from there by Vladimir Rosislavich, then was restored again by Vladimir Monomakh, with him he had once been friends. But, then he was forced to flee once again to Poland, when Monomakh took Yaropolk’s mother and wife prisoner in Lutsk. Yaropolk returned from Poland and, having made peace with Monomakh, settled again in Vladimir. From his personal history, it is known that in 1074 he travelled to Germany with his father Izyaslav, to the court of Henry IV, who subsequently married his sister Paraskeva. In that same year, Yaropolk was sent by his father to Pope Gregory VII, and received from the Pope the Russian throne, “with the consent of the Father and the Mother.” Yaropolk was murdered on the road from Vladimir to Zvenigorod on 22 November 1085 (or 1086), and was buried in a shrine in the Kievan Church of the Apostle Peter, which he himself had founded and which was located in Dmitrievsky Monastery. The Orthodox church anointed Yaropolk a saint (his saint’s day is 21 November).

The early chronicles (per the Radziwiłł copy, folio 117 obv.) give a significant, ethical characterization of Prince Yaropolk, dedicated to the death of Izyaslav, mourned by his son Yaropolk, his son’s army, and the entire city of Kiev. The son was in many ways like his father, but Izyaslav was described as “a good looking man, large of body, and gentle of rule, who hated the corrupt and loved truth; he did not play tricks or flatter, but was simple of mind, and did not repay evil with evil; for how many of you Kievans drove him out, plundered his house, and yet he did not repay you with hatred; he was exiled by his brother and walked a foreign land, but now sits once again upon his throne. Those who support Vsevolod now support him, and tell him how welcome he is; but he does not repay evil with evil, but rather is comforted and says: insofar as you, my brother, show me love, lead me to my throne and call me your elder, so too shall I forget your former ill will; you are a brother to me, and I to you, and I lay my head before you…” and so forth, as the Chronicle states, according to the divine law concerning those who would “give their souls for their friends.” Furthermore, the chronicle tells of how once Vsevolod had become Grand Prince of Kiev and established Yaropolk in Vladimir-Volynsk and had given him Turov, in the year 6592 Yaropolk came to Vsevolod in Kiev on a holiday, and in his absence the Rostislaviches seized his land, Vsevolod once again returned him to his throne; but, in the following year, “having listened to evil advice,” Vsevolod sent Vladimir Monomakh to drive him out. Yaropolk left his mother and his army in Lutsk and fled to Poland, and Vladimir captured Yaropolk’s mother and wife and led them to Kiev, and seized his estate. But, the following year, Yaropolk returned from Poland, made peace with Vladimir, and once again took rule in Vladimir-Volynsk. However, Yaropolk stayed there for only a short time, then journeyed to Zvenigorod, and on route was treacherously slain, at the instigation of evil people, as he slept in a cart, killed by his one of his own traitorous warriors, Neredets,[10]jeb: “the Unhappy.” who then fled to Przemysl and to Ryurik Rostislavich. The chronicle, with obvious commiseration, tells how all of Kiev went out to meet the slain body: the princes, boyars, the Metropolitan, all of the clergy, and all of the Kievans; and they created a great lamentation over him with Psalms and songs, and conveyed him to the Monastery of St. Dmitry, where they buried him with honor in the crypt of the Church of St. Peter the Apostle, “which he had himself founded on the 5th of December.” Anew, the chronicle laments the untimely death of this innocent man as a victim of human malice: “We accept many evils without guilt, we drive out our brethren and see them plundered, and what’s more, we give bitter death to force them to eternal life. Thus too was this blessed prince, meek, humble, a lover of his brethren, who gave tithes to the Holy Mother of God from all of his cattle and grain every year. He always prayed to God, saying: My Lord God, Jesus Christ, hear my prayer, and give me death as you gave to my brothers Boris and Gleb. From a stranger’s hand, let me wash away by sins with my own blood, and escape the vain light of this world and the rebellious snares of my enemies. God, do not spurn his petitions and receive their good, for their eyes do not see and their ears do not hear, nor does the person’s heart ascend, unless God accepts those who love Him.”

Based on these historical facts, we can guess that the prayer book and Byzantine miniatures were created for Gertrude, mother of Yaropolk, in Lutsk or Vladimir-Volynsk, or generally near the border of Poland and Halych. This conjecture is supported by the type of manuscript and the Byzantine inscriptions on the miniatures. A manuscript created in Kiev would have had completely different parchment, different dimensions, and different inscriptions. Our conjecture is further supported by a third part of the manuscript, also constituting a sort of appendix to the Psalter, on the first four pages (or really 3, since the first page was left blank). This introduction is a calendar, with memorial notes in two columns by month, and completely written in gold (as Sauderland has demonstrated) in the early 12th or late 11th century. According to Sauderland, the calendar was written between 1145 and 1160, in one of the monasteries in Wirttemburg, where, according to inventories, a psalter written in gold was sold by the wife of Boleslav III to the daughter of the Russian Grand Prince. In 1229, the Psalter fell into the hands of St. Elisaveta of Hungary, whose uncle, Patriarch Aquilen, received it from her hands for the cathedral in Chividale, where it now resides.

Part II – A review of the miniatures

Let us proceed to a review of the individual Byzantine miniatures.

Miniature #1

The first miniature depicts the Apostle Peter, standing facing the viewer, prayerfully addressing Yaropolk, his wife, and Yaropolk’s mother, who crouches at his foot. The illuminator, it seems, attempted to combine the typical form of writing the two letters In with vegetative ornamentation, which he was used to using or seeing in Byzantine capitals. He did not want to confine himself only to the figures, as then the letter n would have been completely incomprehensible, and the shape of the letter I would not have worked. This is the reason why, following the outline of the letter I, he also gave it a wavy, plantlike line. According to custom, he surrounded the entire golden background with a special type of stripe or frame decorated with zigzags. Above and below this border is decorated with special lily-shapes (the Byzantine krin), which strengthens even further the shape of the letter I. The gilding used on the background is not entirely according to Byzantine technique; it is pale and shiny, and even gives off a greenish shade, making the white inscriptions only faintly visible. As a result, we have shown all of the inscriptions in this text, since they are of special interest. The Apostle Peter’s halo and all of the outlines of his himation[11]jeb: an outer garment worn by the ancient Greeks over the left shoulder and under the right. are hatched in dark violet, somewhat brownish in shade, paint — that is to say, an ancient purple, and the apostle’s himation was supposed to be purple, or dark violet-brown. At the same time, however, the clothing is so covered with gold spaces or highlights that it could be (incorrectly) considered to be gold. The apostle’s chiton is dark-blue, with the same golden highlights. His right hand, which is held slightly forward and to the right, is covered by the himation and is held in the form of blessing that was typical for the second half of the 11th century on images of the Blessing of the Almighty, known from many mosaics. Further, the apostle is holding a scroll and collection of keys in his left hand. This combination is not completely typical, but in this case the keys can be attributed to the text that runs alongside: Sancte Petre, princeps apostolorum, qui tenes claves regni celorum… / Saint Peter, leader of the apostles, you who hold the keys to the kingdom of Heaven….

The overall drawing of the apostle is schematic, lacks understanding of form, and represents a distortion of the Byzantine template. These limitations are especially visible in the drawing of the clothing, in their tangled folds, and in the outline of the figure itself, especially on its right side. The artist appears to have copied this figure of the apostle from another manuscript which was not Greek, but Latin-Byzantine. He preserved all of the strange bends and breaks in the clothing’s folds, and was unable to parse out the drape of the himation. Just by looking at how he confused the folds along the chest, from which a wide band of the himation should cross over to the left shoulder, it is possible to understand the painter messed up when he copied these details into his illumination. The edges of the himation along the chest have merged with those of the chiton, resulting in malformed nonsense. The end of the himation which was artistically slung over his left shoulder was actually cut at the shoulder, such that in the original, it most likely descended significantly further.

The apostle’s head is also not a cleanly Byzantine form according to those known from the 10th or 11th centuries. His curly hair is presented in way that was more commonly seen on depictions of the great martyr St. George than on the fisherman of Galilee. In Byzantine originals (there are many, but the best and largest example is the depiction of the Apostle Peter from the Church of the Chora Monastery, now the Kariye Camii Mosque in Constantinople, which we have discussed on multiple occasions[12]Kondakov, N.P. Bizantijskija emali sobranija A.V. Zvenigorodskogo, p. 271; Vizantijskie tserkvi i pamjatniki Konstantinopolja, p. 187.), the apostle’s hair is short, somewhat tousled, scattered about his head in various separate locks; they have a rough, flat, energetic character. These are the locks of a simple, somewhat rough, direct, decisive individual. In the Latin manuscript, instead, we see schematic rows of hair curled into ringlets. The same is also true of the simple and, one can say, peasant beard in the Chora monastery mosaic, while in this miniature, this rough, passionate characteristic is absent; instead, we see a sort of shortened, insignificant beard. In the version of the apostle depicted in the mosaic, we see the large, wide-set, bright and far-seeing eyes of a fisherman. We also see his slightly curved, Semitic nose. He is naively upbeat with an expression of rough simplicity, with relatively thick lips. His face is overall oval in shape, as passed down through centuries of tradition, creating the realistic physiognomy of this honest and deeply religious fisherman with characteristic, almost diamond-shaped, facial features. There is nothing characteristic or similar to be found in the Latin manuscript. Here, we have a generally typical face of a Byzantine saint, with a gloomy pursed brow, looking off to one side, with a dry, completely straight nose and just as dry lips.

The Apostle is shown standing amidst green, blooming fields scattered with brightly-sparkling red flowers. A female figure falls at his feet, holding and preparing to kiss his left foot. This latter circumstance serves as a very curious indication, if only we could, in time, verify such a theory. Indeed, although we have encountered depictions of individuals worshipping at the feet of the Savior or the Virgin with Child in medieval Christian art of the Byzantine period, we definitely do not recall any instances before the saints or apostles. It is quite likely, therefore, that while depicting a faithful Catholic in this illumination, the illuminator was familiar with the habit of kissing the foot of a statue of the Apostle Peter located in the Vatican basilica. It is known that this statue was considered to have been a work from the 5th century, but the custom of kissing its foot has existed since ancient times. Moreover, there is a more recent theory that this statue was created in the 8th century and can be attributed to the school of Arnolfo DiCambio. This theory, which is unjustified by the work’s style, is now suspect due to some evidence in this miniature. For the sake of completeness, we should add that, of course, the statue of the Apostle Peter depicts him seated, and that the modern presentation of this statue on a tall pedestal, permitting one to kiss the foot while standing, dates to the 17th century, to the time of Pope Paul V, who had the statue moved to the Vatican from the monastery of St. Martin.

The depiction of Prince Yaropolk’s family serves as a subject of significant interest for Russian archeological research into illuminations, and due to its detailed depiction, deserves first a description, and then an analytical overview.

The inscription over Yaropolk’s head, written in whitework over gold, is in half-Greek and half-Slavonic:[13]What exactly the Russian Grand Duke’s title means, in this case, is absolutely impossible to determine, based on available materials. The only case which can be compared to such a general glorification of the prince is the addition of the phrase χραταίος къ ρήξ given to the King of Sicily around the same time. It is possible that the term δίχαιος / “righteous(?)” refers to an honorary title given to Yaropolk at the Papal court or even by the Catholic Church, but this is only a guess. Nevertheless, the term and inscription are entirely in keeping with the tastes and customs of the time.

Ό Δικέος Ꙗропълк[14]jeb: Yaropolk the Righteous

Yaropolk is standing, with one hand raised toward the Apostle and with his head bowed. There is a golden crown upon the prince’s head – a cap consisting of a wide hoop or band, decorated with stones and trimmed with pearls. Atop this band there is a semi-circular, soft-looking top or cap of gold cloth, also decorated with stones and pearls. Moreover, the lower part appears to divide the semicircular or conical top into four parts, which are decorated respectively with stones. For simplicity, the illuminator limited the illustration to only one of these lower panels and one row of pearls running from the brow to the back of the head. On this semi-circular part, however, he placed a transverse row, and inside it, placed a large sapphire surrounded by pearls. The prince’s hair, which emerges from under his hat, is painted in a reddish color, that is, a reddish-chestnut shade, an interesting circumstance for the question about this first Varangian family of princes. But, the type of face which the illuminator has given Yaropolk differs little from the typical Byzantine sort; specifically, it has the same large, beautiful eyes, the same slightly Roman nose, small lips, juicy tones, and flesh-like colors. Atypical is the prince’s small, rounded, drooping chin under his beard, which once again seems to retain a characteristic feature from the person depicted – the beard is also chestnut in color. The prince is wearing a crimson caftan, with a broad collar and a wide belt, and with a wide border along the hem. The collar, belt, and border are all of gold fabric and decorated with precious stones, sapphires and rubies. The caftan, which is opened in the front, has a border along each edge of gold braid, which in width appears to be similar to the galloon found in medieval Russian hoards and graves of princes from the Grand Prince period. The caftan appears to be made from a single color silk velvet brocade of samite, with golden kriny (stylized lilies) woven into the material. This fabric, used for formal Byzantine vestments, is especially well known, as we shall see, from the 10th and 11th centuries. The prince’s feet wear red shoes, which in ancient times were regalia of the Byzantine emperors, then of the Bulgarian tsars, then of European kings and western leaders without distinction. We should particularly note that prince is not wearing any kind of mantle or cape. On the caftan’s sleeves, near the shoulder, there are two gold bands, and there are gold cuffs at the wrists. The caftan has narrow sleeves, and can therefore be called a kabat.

The Grand Prince’s wife is presented in robes which are more decorous, complex and luxurious than his own. She is wearing a light blue outer dress, decorated at the hem with a wide gold band strewn with stones. She has a formal item of dress called by the Byzantine court a lorom thrown over the back of the dress and passed over both shoulders. This type of dress ran from the shoulders over the chest to the belt, and was tightly fixed to the body, such that the long end emerged from under the belt and fell to near the right knee, then was thrown over the right arm, or as in this case, was fixed under the same belt. We shall see later in an analysis of this outfit that the prince’s wife is wearing robes of a so-called lorat patrician of the Byzantine court. The princess’s wrists are decorated with gold cuffs decorated with stones. Her head is covered, firstly, with with an encircling cap which tightly binds the hair in a thin silken material and a tightening lace which runs along the hairline around the entire head, such that in front, the cap forms a sort of hair roll, a Byzantine style which we have already had the opportunity to discuss in detail in another location.[15]Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Vol. I. pp. 208-209. The cap is pale-pink; usually in Byzantine miniatures, this cap appears as a band of Arabian silk with colored stripes, such as on a towel, across of the fabric, but the head would be covered with the material lengthwise, such that the hair roll appeared to be divided by transverse stripes. Further, the princess’s head is covered by a tall crown of golden fabric, tower-like in shape, corresponding to the later kokoshnik. The crown is decorated with precious stones, and the top is broken up into triangular points, between which there are precious stones (apparently, laly[16]jeb: A general term for red gemstones: rubies, spinels, garnet, etc.) on pegs (spines). The nape is covered by a thin veil which descends from the crown down the back. Her feet are also covered by red shoes. The belt which tightens her golden lorum is also red.

Yaropolk’s mother, who has fallen at the apostle’s feet, is unfortunately poorly preserved, and was likely clearly distinguishable based on the original. In addition, as we shall see below, her robes are of extremely important, historical significance. Namely, on the original we can clearly see that Yaropolk’s mother is dressed in a scarlet feryaz’[17]jeb: A form of ceremonial outerwear with long sleeves worn by boyars and nobles in medieval Rus’ and Poland., over which we can see a sort of veil of thick brocade which lies stiffly over the drape of the lower material; this is an outer mantle [Rus. мантия, mantija] or Grand Princely cape [Rus. плащ, plasch]. This mantle covers the entire back, is pinned at the chest with a round brooch, and is made of gold brocade embroidered with scarlet circles without any interior design (most likely due to the difficulty of drawing such drawings in these tiny circles).[18]For an analysis of similar designs on mantles, see Part III below. Part of this golden mantle is also visible below the figure, but since there are no circles upon it, we can suppose that this is the golden lining of the mantle. The mother’s face is relatively young-looking, which does not correspond at all to the appearance of a mother of a 40-year old prince, and therefore does not appear to be portrait. Upon her head is the same sort of cap and a fabric veil with flowers which, unfortunately, are barely discernable, as in this section of the miniature, the gouache has nearly completely crumbled away. At the nape, it appears, a thin veil drapes over her back, as we also saw on the princess. Here we also see the same golden cuffs and red shoes.

Miniature #2

jeb: A color version of this image can be seen online here.

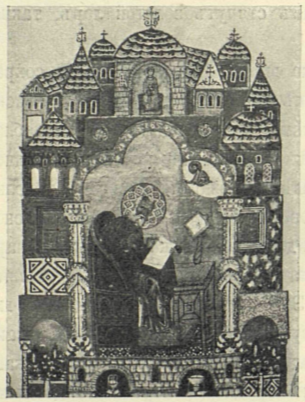

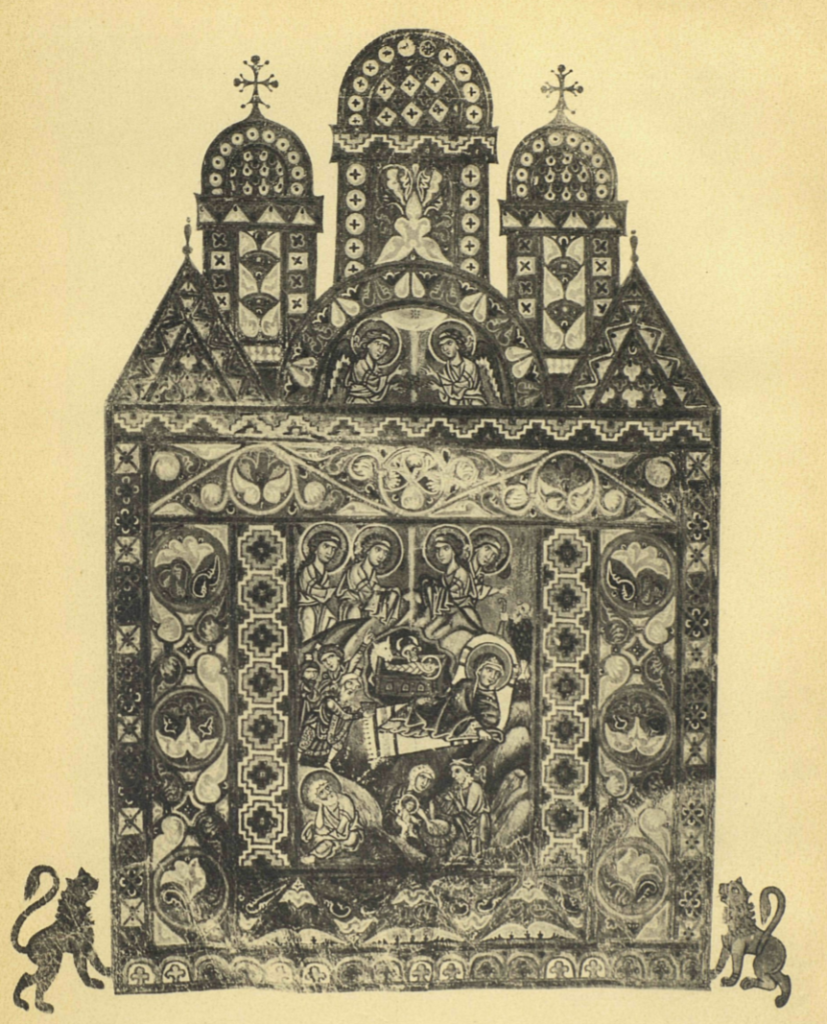

The next illumination, located on folio 9, presents a sort of ornamental miniature, similar to those which we frequently encounter among Byzantine miniatures. A good example for comparison is a miniature from a manuscript of the Homilies of St. Gregory the Theologian, in the library of the St. Catherine’s Monastery of Mt. Sinai, No. 339, 12th century (Illus. 1). This miniature shows the front façade of a large domed temple and an attached monastery, surrounded by a large number of hermit cells. Four or five domes can be seen on round cylindrical towers (“drums”), as well as several towers crowned by four-sided pyramidical roofs. These towers, some of which serve as gates and others which serve as walls, are placed in a peculiar, somewhat chaotic, disorder. Below we see open porticoes, densely strewn with plants and flowers. Everywhere, we see windows and doors, marble balustrades, various forms of decoration, and walls of varied masonry. Below the central cupola, we see a mosaic depiction of the Virgin with Child, seated on a throne. The entire center of this architectural display is taken up by an ornamental arcade, within which Gregory the Theologian is depicted at work. This arcade stands upon a foundation of rusticated walls with open arcades, before which stand splashing fountains. This entire pied, pompous ornament, that is, uses the architectural complex of monastic buildings to serve as a form of carpet page [Rus. выходная заставка/миниатюра, vykhodnaja zastavka/miniatjura, “exit illumination/miniature”].[19]Kondakov, N.P. Puteshestvie na Sinaj v 1881 godu. Odessa, 1882, pp. 143-152.

A somewhat simplified version of this miniature (Illus. 2) can be found in the Izbornik of Grand Prince Svyatoslav Yaroslavich from 1073,[20]See the Izbornik (facsimile) published by the Society for the Lovers of Medieval Writing, 1880. which has two different miniatures showing the scheme of a cupolaed cathedral with three (visible) cupolas, and an open arcade displaying a group of saints (led by St. Basil the Great). These carpet pages were intended for the honest glorification of all the church fathers and teachers whose works, in whole, excerpts or brief summary, are included in the theological and historical-biblical sections of this wonderful encyclopedia. The form of illumination, in this case, is not only characteristically simplified, but is reduced to a single decorative style which, in short, should be considered to be a Russian adaptation of Byzantine ornamentation (we hope to create a detailed analysis of the ornamental forms of illumination in the Svyatoslav Izbornik and of these current miniatures at a later time). We note only that the architectural forms depicted on this miniature are perhaps more reminiscent of the Svyatoslav Izbornik than the properly Byzantine miniatures in the Homilies of St. Gregory the Theologian. This similarity can be seen primarily in the schematic ornamental forms of the illumination itself on the floors and the two towers, and in particular in the medium-wide border decorated with large flowers inside circles which are repeated in the Izbornik.

In the central templon of the miniature and in the central zakomara we see displayed, according to the usual Byzantine tradition, the Nativity of Christ. Above, a shining star in the heavens sends a ray of light down to Earth. On either side of this ray there are two angels, singing “Glory Be to God on High.” Below there is a group of four angels, likewise praising peace on earth and goodwill in men, kneeling before the Epiphany. One of the angels, who is literally making a sign of blessing, preaches the Gospel to a shepherd who has climbed a hill. The hill is open in the middle, presenting a cave or cavern. Inside the cave, we see a cradle, richly decorated with precious stones, and inside, we see the swaddled infant. An ox and a donkey are eating from the manger. The Blessed Mother reclines to one side on a mattress. The three wise men, of three different generations, approach the cave in Persian garb and hats. Below on the left, under the mountain, Joseph sits half-asleep, but with his head raised as if listening to the angelic praise. Next to him, Salome stands by a fountain, holding the child and testing the water in the font.

As can be seen from all of this, the composition of this Nativity presents the most common or typical iconographic forms from later Byzantine art. Of main interest in these forms is how the two angels in the upper arcade are set apart, where the Nativity scene diverges from its lyrical story in the form of a well-known song of praise (“Glory Be to God on High”). Evidently, the scribe was not merely a calligrapher, limited exclusively to the copying and illumination of other people’s compositions, but was a master icon painter, and like all Greek and Russian icon painters (including illuminators), was able to a typical composition on the most varied backgrounds, expanding or contracting, dividing and connecting all kinds of groups, placing them into well-known scenes. We have already had several occasions to draw the attention of those interested in Russo-Byzantine archeology and folk arts to the dexterity of skill with which artisan-performers are guided in their field, since they have at their disposal commonly-used templates. It only takes a few instances of direct observation of our master icon painters to be aware that these master artisans never made copies in the precise meaning of the word. Naturally, there are known exceptions, for example renderings of significant icons, but even in these individual cases which one can speak of as copies in how they were created, in the end, the icon painter copies only of parts of the icon, and mainly reproduces it according to the template he was familiar with. As for small or multi-faceted icons, such as those for holidays, etc., in these environments, the icon painter, when transferring his drawing onto the levkas[21]jeb: The white foundation upon which an icon is painted, made of chalk, gypsum, or alabaster powder mixed with a binder, similar to gesso. and outlining the figures, we will quite readily carry out those figures in the techniques and styles to which he is accustomed. In this way, his cartoon may be of various styles (Fryazh, Stroganov, or even Academic) but he will perform it according to his own techniques. He has not only the typical drawing, which he can draw by rote, for figures that are male, female, standing, sitting, Apostles, Saints, church fathers, but also the methods he has learned for drawing clothing, such as folds and decoration, heads, hair, noses, and all of the other details which he learned in his workshop over the course of many years and which have become for him a common template. Moreover, a real artisan is never shy to depict a famous holiday in any location, to shrink or expand it as needed, to depict figures in this way or that, depending on the patron’s demands. This is why we think it extremely important to determine from various examples those features which were included in all depictions of various Byzantine and Russian iconographic themes, but realize that these do not constitute mechanical copies, but rather are unending variations of each theme in various small details. As an example, we turn to the Nativity of Christ, for which we can easily find hundreds of variants and yet still yet know that they are renderings of the same subject. Let those who wish to examine illuminations and icons from this point of view, and to review the figures and groups of angels in the Heavens, two groups of angels on earth, an angel speaking with a shepherd or approaching a pair of shepherds, groups of wise men, the bathing of the Child, et. al. Even the positioning of the Holy Mother, in some lying down, in some sitting on a tall mattress, is shown in diverse ways. In the current miniature, she is shown half-asleep; in others, she is seated and prepares to hold the swaddled Child in her hands, etc. Meanwhile, it cannot be denied that the basis of all of these depictions, there is a certain unchanging template, but that this pattern should be understood in its own way, within the limits of each particular workshop.

To conclude this description, we should point out one ornamental feature of this miniature. At the bottom, on either side of the illumination, the scribe has placed two lions which, having raised their heads, seem to look upon the depicted event, while also serving as guardians for this newborn king. One of these lions is shown in the typical position with his tail thrown over its hind leg; that is, this lion, as we see in many other examples, is Byzantine in origin. But, the lions were worked in gold in the original, and it seems the scribe borrowed them from a miniature where these lions played the role of statues, where, of course, they sat upon pedestals. In the current example, he mistakenly left out this important detail, and gave these animals forms which have agility that would be unnecessary in a statue. This topic deserves further discussion at a later time.

The lettering on the illumination is distinguished by its muted, dirty coloring. But, the faces are still of pure, good color, and the gouache shows relatively little peeling.

Miniature #3

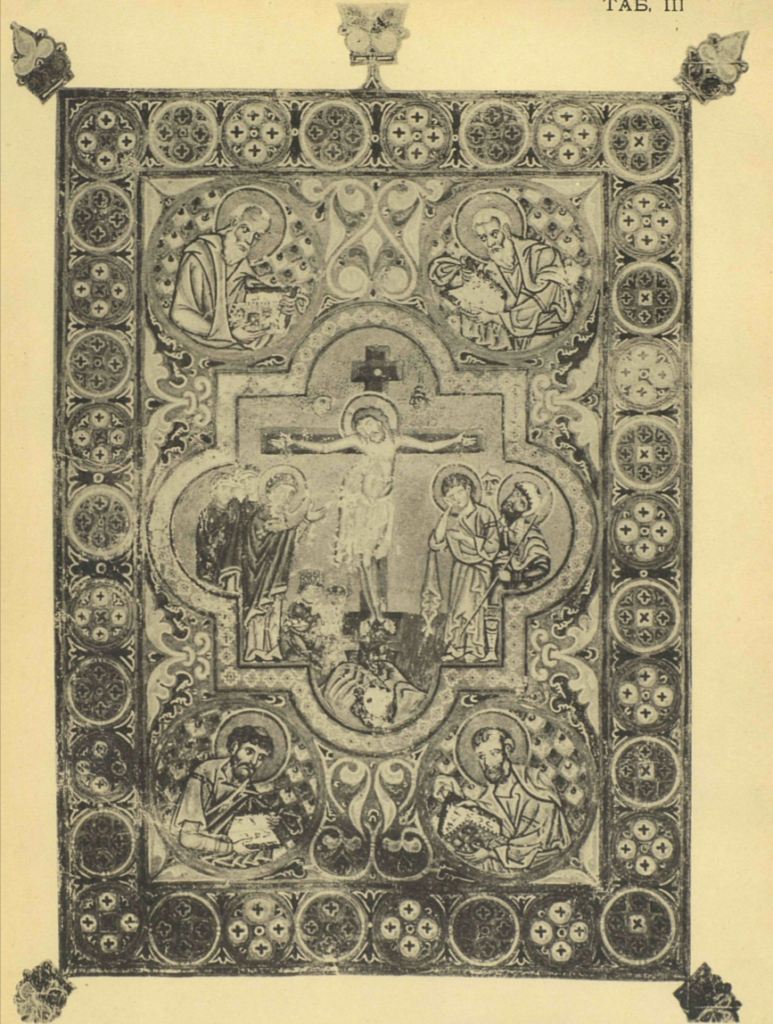

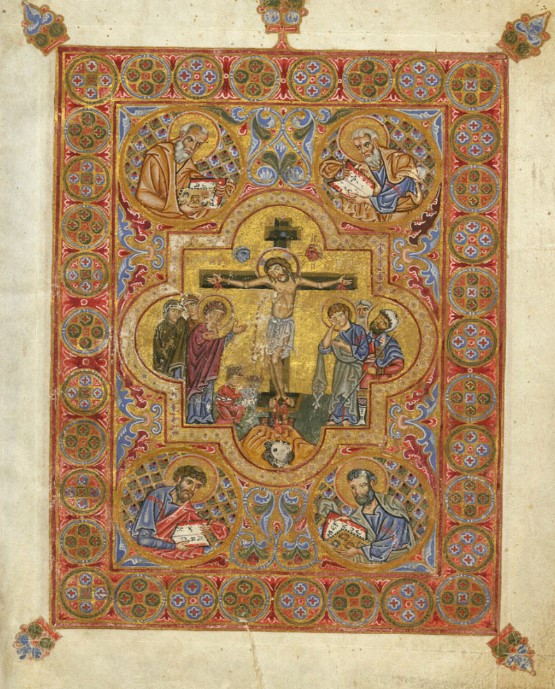

Plate 3: Miniature on folio 10: The Crucifixion of the Lord, and the Evangelists.

jeb: Color image of the Crucifixion. Image in public domain.

On folio 10, alongside the previous miniature, we see a decorative templon with a depiction of the Crucifixion on the central shield, and the four Evangelists around the shield, forming a sort of border, somewhat like a sort of Gospel cover. But, from an iconographic point of view, as well as from an ornamental whole, this illustration does not present a strictly Byzantine composition. For example, the cross-shaped shield in the middle does not fully correspond to the large circles placed in the corners. They are too large, do not fit the corners at all, and what’s more, the figures placed inside them are intentionally bent forward (ostensibly toward the Crucifixion, but this is only true in the upper circles). In addition, the five figures in the center are bordered by a typical border which does not correspond to the figures at all. The Crucifixion, of course, does appear on manuscript covers, as a central scene from the Gospels. For example, we often see the Crucifixion on Georgian and Byzantine silver covers, and the combination of the Crucifixion with the four Evangelists at the four points of the cross is also common; but, those cases usually depict Christ alone on the cross, or only Mary and John the Baptist, whereas here the Crucifixion is presented in the form of a complex historical scene, rather than just the lone figure of Christ.

We also see here a specific characteristic of enamelwork art as used in Byzantium, that is, cloisonné enamel. The scene of the Crucifixion in particular is reminiscent of enamel images of exactly the same size seen on special shields on manuscript covers. Works of enamel are distinguished by the very character of the folds of clothing, the well-known sketchiness, and in particular a certain shortness of figures, as well as the predominant quality of features and small details compared to the overall pattern. It is, finally, worth looking at the border of this central shield. Its enamel-like character is created through the placement of small sets of multi-colored crosses, set up along the border. Given how such a pattern is understandable in enamel work, composed of cells mechanically filled with enamel, it is, on the other hand, just as incomprehensible why one would choose this approach for painting with a brush. The four medallions with the Evangelists have bright, colorful backgrounds in the form of a lattice or trellis which covers the field in pink and light blue, dark and light. Here again the image is completely natural for enamelwork, but unprecedented for painting. These brightly colored backgrounds come to the fore and interfere with making out the beautiful faces of the Evangelists. Then, there are the curious ornaments which fill in the resulting gaps. The top and bottom ones are composed of stylized flowers or petals, and are reminiscent of ornamentation from similar illuminations in the Svyatoslav Izbornik. The others, created from a combination of light blue and pink flowers, are curious in their rare shape, in the form of two acanthus leaves, joined by a ring, which appear here to be completely out of place. Finally, there is an outer border covered with circles filled with smaller circles and crosses placed in a cross shape on each shield. This is once again a common enamel design, but looks strange in painted form. As a whole, this miniature creates a inharmonic impression, as a result of its predominantly reddish tone and the variegation of its light blue, pink, dark green, crimson, and white details. This is also the case for its decorative, “mix-and-match” character with regards to its iconographic content.

The central scene of the Crucifixion, out of all the miniatures in this set, is the most typical and rather reminds us of Latin copies of Green originals, rather than the Byzantine originals themselves. It is not unusual that its overall artistic craftwork is more similar to enamel artwork than it is to painted items. The entire design is so familiar, that if this instance had not had any special stylistic meaning of importance for solving our Russian historical questions, it would have been unnecessary to include any analysis of it in this description. It would have been sufficient to look at the poses of those standing before Christ, the design of the faces and fall of their clothing, and the exaggerated expression in their movement, in order to determine the merit of the image itself. But, as we need an accurate conclusion on the question of the style of the illuminations under review, we should review the various details of this scene.

Firstly, as opposed to the typical iconographic composition of the Crucifixion seen in illuminations, enamel icons and images, and finally in enameled crosses, here we do not see Christ’s final appeal to Mary and his disciple which is typically denoted by the well known Greek inscription saying: Mati, se Syn’ Tvoj [Rus., “Mother, behold Your Son”]. In this illumination, we see the following moment: the Savior’s eyes are already closed, and a stream of blood flows from between His ribs into a cup held by a kneeling female figure. The Mother of God stretches her hands toward her crucified son, and behind her stand two of the Myrrh-bearers. On the other side, John the Baptist, the young apostle, mourns, pressing his right hand to his head, and his left to his chest. Next to him, the centurion Longinus gazes sadly at the cross. Behind them, we see the head of Joseph of Arimathea. On either side of Christ’s head we see the sun and the moon in the form of two heads without the typical medallions surrounding them. Golgotha is presented as a low hill, inside which, in a dark, open cave, we can see the head of Adam.

In its composition and how the forms have been depicted, this illumination is very similar to a Munich enamel frame for a reliquary holding a fragment of the True Cross [Rus. древохранительница, drevokhranitel’nitsa, “wood-protector”] created in the 11th or very early 12th century.[22]Kondakov, N.P. Istorija i pamjatniki vizantijskoj emali. St. Petersburg, 1892, p. 184. The differences between the two are limited to the fact that in the Munich reliquary, there is a Greek inscription, Christ’s eyes are semi-closed and, the blood flowing from his rib falls into a phial that is standing on the ground. Furthermore, on the Munich frame, there are four mourning angels in Heaven, and three soldiers dividing the clothes amongst themselves. Moreover, if we dissemble the details of this image in the usual way, we find the following peculiarity: the Savior’s cross is shown in the dark brown of wood, with a dark violet tone in the shadows. It has a board at the top for an inscription or title, while below, there is a wide board, like a pedestal, not inclined, but perfectly level. This board began to be shown as inclined/bent around the 11th century because of the inability to show this wide board in perspective. Christ’s body is slightly bent and painfully thin. His head is shown again in ancient form, with a round beard. He is dressed only in a loincloth. As for the figures standing before him, it is worth nothing their shortened proportions and the original end of the himation which falls from John’s arm. The most curious detail of this entire presentation is the woman who holds the blood of Christ in a chalice or goblet, which stands on a towel. This woman is displayed in rich, red clothes, over which she has wrapped a multi-colored Eastern veil or scarf, the same kind of fabric with which she has enveloped the foot of the chalice. She wears a tall golden crown or kokoshnik on her head. Without any doubt, this image is allegorical, if not for the church itself, given that her head is not enclosed in a halo, then for the synagogue which received the blood of Christ. Above the cross, on either side, we see the typical inscription: Н СТАУ РОС’С.

We still have to say a few words about the images of the four Evangelists. They preserve the best characteristics of the Evangelist types established by Byzantine art. On them, we see their names inscribed: ЛꙊКАС МАРКОС IѠА(НН) MANФЕО / LOUKAS MARKOS IOA(NN) MANFEO,[23]This grammatical error in Matthew’s name is a result of the harmonization of sounds in the Greek language, and is rarely encountered. See Istorija i pamjatniki vizantijskoj emali, p. 278, ex. 2e, Plate VI. but John the Theologian and the Evangelist Matthew look almost identical, that is, the interpretation from which the illuminator selected his example was already indirect and distorted. The only difference, which is difficult to make out, is in the details of the forehead and hair. One wears a light blue chiton and yellow-brown himation, while the other wears vice versa. The Evangelist Mark, as opposed to the typical form, is shown in grey, with greying brown hair, and dressed in dark blue and green. Luke, as is typical, is tonsured. He is dressed in light blue and red. A tendency toward ornamentation in the folds of clothing can be seen especially clearly in this figure.

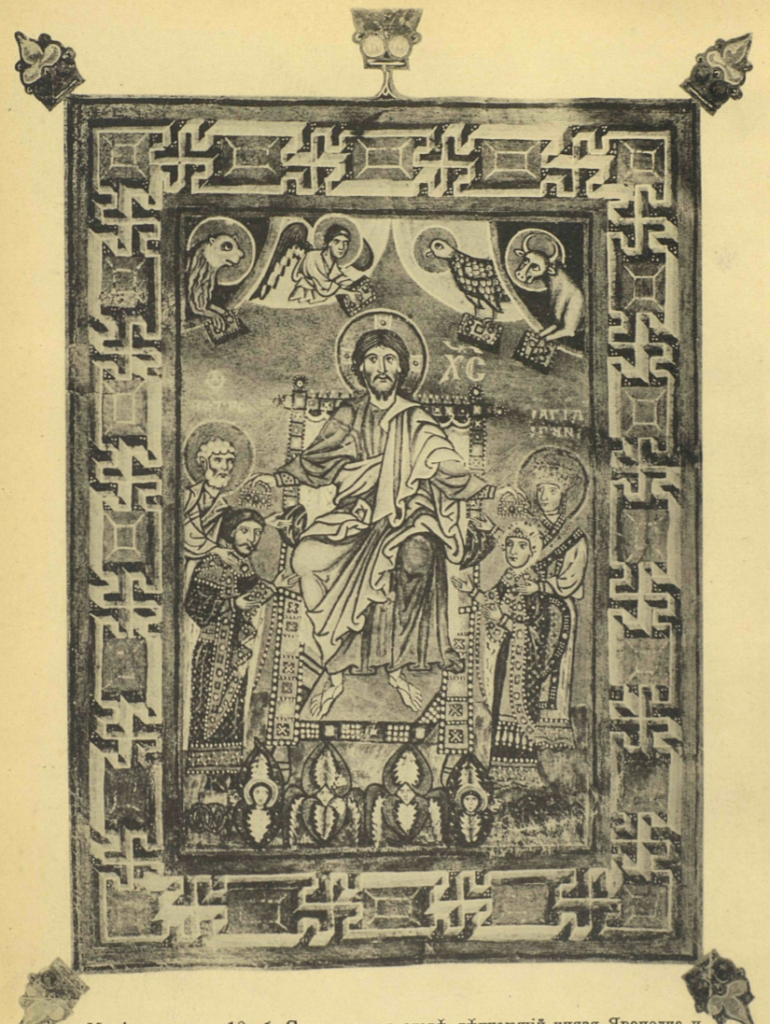

Miniature #4

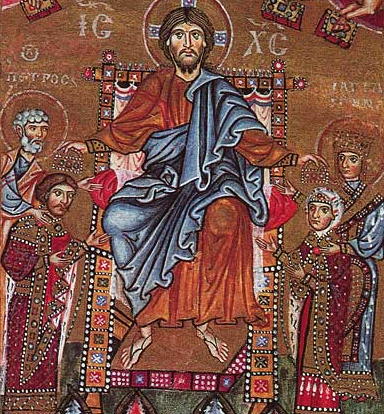

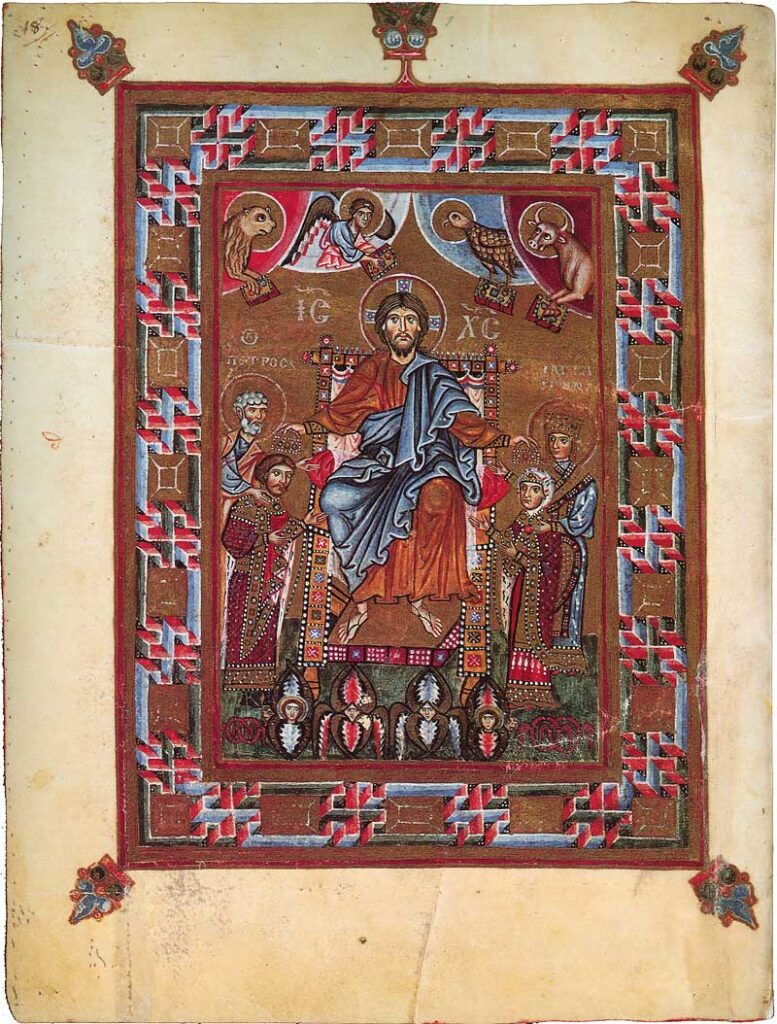

The next Byzantine miniature is located on the back of folio 10 or on folio 11 (or by another counting system, folio 18) and consists, like the first, of an essential image dedicated to the owners of the codex. Once again, the decorative composition of this illumination and its iconographic structure has its own particular, characteristic importance to resolve questions which any scholar of these miniatures should ask. The illumination is surrounded by a peculiar border which presents a perspective view of a ribbon-like meander which runs around a kind of mosaic-covered surface. It is apparent that in this case, the ornament duplicates the fanciful decorations of mosaic floors which were in use from the 9th to 12th centuries in both Byzantium and perhaps even more so in the Christian West. It is of particular importance that this design is a deliberate repetition of an illumination from the Latin Egbert Psalter itself depicting the prophet David playing the psaltery (folio 19 obv., a carpet page from the Psalter) [jeb: see image to the right]. The scribe, in this case, has altered the borrowed design, increasing several of its dimensions and surrounding the entire illumination with five Byzantine kriny buds. It seems the illuminator was tasked with, as it were, extending the Latin Psalter by adopting its style.

The scene depicts the Savior reclining on a richly decorated throne and crowning Yaropolk and his wife, who are led to the throne by the Apostle Peter and St. Irene, the princely couple’s patron saints. Based on this scene, we learn that Yaropolk and his wife’s Christian names were Peter and Irene. Similar types of decorative scenes had long been a required element for imperial house of Byzantium, since ancient times. An originally Latin then Greek formula, “in Christ” or “in the name of Christ, the Eternal King of Kings,” was part of the title of the emperors, elucidating their right and, at the same time, their obligation to execute Christian law. Byzantium granted other ruling houses the right to be called Tsars, Kings, or Princes by adding the title “in God” (έν Θεωνα) or “with God” (σύν Θεωνα). Understandably, these ruling families never observed this strict distinction, in particular in decorative art related to their veneration for the Empire and, in particular, once these families had adopted the Christian faith.[24]The most complete title is shown in a scene of the coronation by the Savior of John and Alexios Komnenos in the amazing manuscript Vatic. lib. Urbin. 2, written in 1128: Christ is surrounded by “mercy and justice” (women in crowns, similar to the one on Irene in our manuscript). John is called simply “Autocrat of to the Romans”, while the younger Alexios is called έν Χω τώ Θ ω πιστός Βασ. and so forth. This coronation rite is briefly described by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in his work De cerimon. aulac byr., vol. I, p. 38; for the later period see Georgios Kodinos’s De officiis, chapter XVII, ed. Bonn., p. 86-89. The patriarch who consecrated the mantle and placed it upon the king, and who then sanctified the crown and placed it upon the emperor’s head at the popular call “άγιος …” (“Holy holy holy”) and “Glory be to God on high,” represented the Savior himself. As such, we find images of Christ (sometimes with the Mother of God as well) crowning the rulers on depictions of the Georgian tsars, Serbian kings, and Bulgarian tsars: these rulers thus became, in a way, “crowned by God” or “chosen by God.” Then, as Reiske has already shown, it became custom to use or decorate the secondary-level titles of archons, dukes, and even higher ranks of court with the title “by the Grace of God.” From this, it became customary to decorate carpet page illuminations depicting coronations, ceremonial manuscripts, diptychs, seal rings, icon cases, and even throne rooms, ceremonial fabric, and formal robes.

In this miniature, the Savior is shown entirely according to Byzantine custom. He is dressed in a brownish/pale-purple (chestnut-colored) chiton, heavily stamped with gold; it is clear that the fabric is not cloth of gold, but rather is of purple fabric. The Lord’s throne is of the same color, although with more of a yellowish shade on the wood, heavily covered in gilt and abundantly decorated with precious stones and pearls. Christ’s himation, thrown into bizarre folds, is light blue. The character of how the Byzantine drawing of the folds has been translated is imitative and, likely, Latin. At the very least, in this depiction, we strongly sense an abandonment of naturalness and a desire toward a certain bizarre grace in the light, rounded folds of the himation’s heavy silk fabric. This multitude of folds is much more reminiscent of Latin illuminations of the 11th and 12th centuries than of Byzantine illuminations. Christ’s form, however, preserves the main Byzantine features: the thick, chestnut hair, the even, arching eyebrows, the stern gaze of his dark eyes to the right, the strong, smooth, slightly crooked nose, his medium lips, his noble, narrow oval face, and his small, drooping beard, lightly divided at the chin.

The crowns which the Savior holds in his hands and which he places upon the heads of the Prince and Princess, are in the form of a circlet or hoop, most likely metallic, with stones, pearls and with a single point by which the Savior holds them. This is the typical shape of a so-called votive crown, as well as of the imperial and princely crowns seen when the Savior is crowning a ruler.

Yaropolk and Irina approach the Savior, lightly bowing their heads and stretching out their hands, are dressed here in special rich attire. This new garb, to state briefly for the moment, correspond to the coronation over which the Savior presides. Yaropolk is dressed in a dark brown kaftan, embroidered with gold, with a gold collar and hem, and with a gold belt at the waist. Over the kaftan, he wears a red (scarlet) cape with wide gold braid, fastened by a fibula brooch at his right shoulder. The gold braid is decorated with stones, and the entire cloak is festooned with pearls. The cape’s lining is of ermine fur, and his boots are black. Yaropolk has light brown hair with a reddish tint, and is face looks the same as in the previous illumination. Princess Irene is dressed in a red chiton with gold designs and fringed with pearls along the hem. Over this, she wears a crimson mantle, fastened at the chest with a fibular brooch with a red stone. The mantle is bordered with side golden braid, strewn with stones, and lined with ermine ur. She wears red shoes upon her feet. She wears a multi-colored Eastern veil around her head, underneath which a cap can be seen made of gold fabric. The ends of the veil are tucked under the hat.

The Apostle Peter is of a standard type. St. Irene of Macedon is dressed completely the same as Princess Irene was in the previous illumination: a light-blue chiton, a gold lorom, and a tall crown with pearls and stones, with a veil in the rear, falling over the shoulders. Over her head is an inaccurate inscription: ϊ άγιά ίρήνι, with incorrect spelling and diacritics indicating aspiration. Peter’s inscription is likewise not quite correct: πετρος, with an unnecessary abbreviation symbol. For us, the depiction of St. Irene in a crown and royal or princely attire, which can be explained by the well-known legend (of relatively late origin) about the Great Holy Martyr Irene. Irene was the daughter of the king Licinia, and was named Penelope at birth, but took the name Irene after being Baptised by Timothy, a student of the Apostle Paul.

Above this coronation scene, seemingly without any iconographic significance, but more to fill in empty space (which in the Latin illumination of David was filled with drawings of animals) we see the emblems of the four Evangelists carrying their Gospels, presented in four Heavenly sections. Even the selection of symbolic emblems, which were extremely rare in Byzantine illuminations from the 10th-11th centuries, and the manner of painting those emblems show that this is a Western imitation of Byzantine examples.

At the bottom of the illumination, not only under the throne but also under the feet of those standing before it, without any separation, we see an extended row of the forces of Heaven in an allegorical presentation of earthly affairs, running from one side to the other. In the center are two six-winged seraphim, with two many-eyed cherubim on either side according to the prophet Isaiah’s vision, and at the ends there are two pairs of so-called altars, in the form of fiery, winged, multi-pointed wheels or circles. It appears that this symbolic detail was adapted here from an image of the Glory of God, and was unsuccessfully added to this image of the Savior blessing the prince’s reign.

Miniature #5

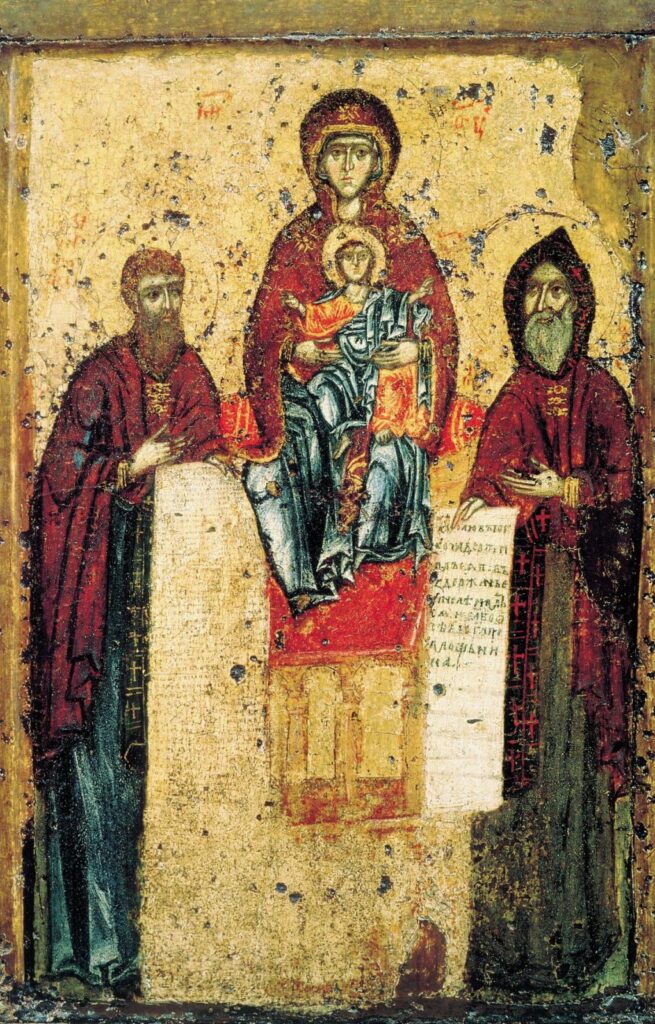

The next Byzantine miniature, located on folio 41 (page 75) shows the Mother of God seated upon a throne and holding the Child. The illumination is surrounded by a colorful, pieced set representing one segment of an endless field filled with mosaic crosses, a design which in its simplest form is called by our people “little towns” [Rus. городок, gorodok]. As with previously discussed forms, this ornament is primarily adapted to enameled items, where it is encountered par excellence. The illumination is worked on a gold field, which is so pale that it looks more like bronze. Upon this golden background, there is a golden throne, made up of massive columns which have been carved from wood and gilded, then covered with expensive, light fabrics. Under the Holy Mother’s feet there is a tall footstool on carved legs and decorated with encrustations. Upon the throne there is a cushion made from two fabrics: green and red, with gold embroidery.

The Holy Mother is shown here in that more or less ceremonial iconographic form which was used primarily in the 11th century in mosaics for church apses and was most consistent in its depiction of the Mother of God. The Virgin sits upon the throne, facing the supplicant [viewer], holding the Child with both hands before her bosom. The Child, holding a scroll between His left hand and knee, blesses the people with His right hand. The Mother and Child’s gaze is directed to the front, or possibly slightly to one side. Ceremonial and solemn presentations of this kind were furnished in mosaics with two approaching angels, and later with saints worshipping the image of the Savior. The oldest image of this kind (6th century) to survive to our time is a mosaic discovered by Ya.I. Smirnov on the island of Cyprus.[25]Smirnov, Ja.I. “Khristianskie mozaiki Kipra.” Vizantijskij vremennik. Vol. IV. 1897 (1-2), pp. 1-93. Aside from the analogous monuments from the 6th-9th centuries mentioned by the author, we can also look at a similar mosaic in the Church of Santa Maria in Domnica in Rome (9th century), a fresco in the church (now underground) of St. Clement in Rome (9th century), and various smaller monuments. But, as this miniature presents a clearly Byzantine character, it appears to be most similar to the (no longer surviving) Our Lady of Pechersk icon, and is in the middle between the versions of that icon and the older Christian forms. In 1085, the miracle-working icon of Our Lady of Pechersk made its first appearance in an apse of the Church of the Dormition in the Kiev Pechersk Lavra.[26]jeb: This original icon from 1085 is now lost, presumed to have been destroyed when the Church of the Dormition was demolished in the Khreshchatyk Explosions, set off by the Soviet Army in 1941 when they retreated from Kiev and abandoned it to the Germans in WWII.[27]The most similar in time frame and character to this was a mosaic in the Church of St. Mark in Venice, over the narthex door, with the Evangelist Mark and the Apostle John (the Child holds a scroll and makes a sign of blessing). Later, from this basic type of the Our Lady of Pechersk, where She holds the Child on Her knee with both hands, there came various other local variants: the Svensk version with saints, the Yaroslav version with angels and saints, as well as the Our Lady of Sicily from 1092 with angels on either side, Our Lady of Cyprus in Stromyno in the Moscow region, etc. In Western iconography from the 11th-12th centuries, there are numerous examples depicting the Holy Mother and Child in this form with Seraphim on either side of the throne; cf. the relief from Odalric’s case in the Vatican Museum, and another similar example in the same museum. From the vaults of this apse, the image began to pass into the church’s altar niches, and also spread out into a multitude of icons which by convenience used this form to depict saints and miracle-workers standing before the Holy Mother. In many examples, the Child Jesus makes a blessing with both hands.

We briefly note that, in this case, the illuminator has intentionally created a solemn depiction of the Mother of God. The Virgin has her head covered with a large, dark-purple (almost black, but with a chestnut-colored tone) maphorion, a kind of veil, which covers her shoulders and falls down her back, seen on the right and with a narrow end thrown over her knee and hanging down the left side. Likewise, her dark blue under-dress or chiton, visible on her left knee, is not covered by the folds of the maphorion. The large dimensions of the maforion and its complex shape gave Gazelov reason to think that Mary is wearing one, or possibly even two veils, such that, in particular, the maphorion on the right knee has a dark-red color, but on the shoulders it is dark-brown, and is the same color on her head, “below which, however, we once again encounter light-blue material.” The German scholar’s bewilderment may be resolved by the following fantastic consideration: the Virgin is wearing a single maphorion, and it is entirely of one color – namely, dark-purple or dark-violet-brown, which appeared, looking at the manner of how it was presented in the original, in some places black, and other places brown in tone. This was recreated by a clumsy scribe in this work too harshly. However, its red tone cannot in any way be accepted, as Gazelov proposes, to be a second layer of veil or the lining of the maphorion, which would be utterly impossible in the way it is depicted on her knee. What about the blue contour under the maphorion on her head, which indicates the exact same cap covering her hair as we see in all depictions of women in Byzantine art. It would be redundant, after all that has been said above, to expand on the idea that the Holy Mother’s maphorion is not gold, that is made of cloth of gold, shaded by dark-violet shadows, but rather is a dark purple, livened up with golden stripes or patterns. Upon her feet, the Holy Mother wears orange shoes. On her arm, we once again see her blue chiton. The maphorion is bordered in bright-red fringe along the folds. The Child wears a blue chiton and a purple-brown chiton, all hatch-marked in gold. Their faces are drawn sharply and drily, with strong olive-green shadows.

Based on this analysis of these miniatures’ contents, it can be seen with sufficient clarity how much the everyday side of these images remains uncertain, such that this description itself has to be carried out in conventional expressions, where those which are inconsistent with convention are often more well-known and have become more familiar. It is true that western medieval archeology from the 9th-12th century period is in the same position, but this is hardly a fact that can assist Russian-Byzantine archeology sufficiently or serve as a future excuse. Russian pre-Mongol archeology is so permeated by Byzantine culture that we could call it “Russian-Byzantine,” and so much could be illuminated by existing Byzantine sources in order to advance noticeably ahead of Western medieval archeology, were it not only for the unwillingness to know these Greek-Byzantine originals. At the same time, after analyzing these images of the Russian nobility themselves, it becomes necessary to briefly revisit, firstly, other similar images which have hitherto become known, and secondly, to review data from Byzantine sources concerning several everyday items which may allow a truly scientific resolution to archeological questions.

Part III

See this blog post.

Part IV

[To be continued in a future post.]

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Festschrift d. Gesells. f. n. Forschungen zu Trier. Sauerland, N.V. und A. Haseloff, Der Psalter Erzbischof Egberts von Trier – Codex Gertrudianus in Cividale. Mit 62 Tafeln. Trier, 1901. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Kraus, F.X. Synchronistische Tabellen der chr. Kunstgeschichte. 1880, p. 55. |

| ↟3 | Ad Santum Petrum. Deus qui beatum Petrum, etc. |

| ↟4 | Sancte Petre, princeps apostolarum, qui tenes, etc. |

| ↟5 | Sancte Petre, princeps apostolorum, qui tenes claves regni celorum, per illum amorem, quo tu dominum amasti et amas;et per suavissimam misericordiam tuam(?), qua te deus per trinam negacionem amare flentem misericorditer respexit in me indignam famulam Christi clementer respice. / jeb: “Saint Peter, leader of the apostles, you who hold the keys to the kingdom of Heaven, by the love which you master and the art you love, and with your soothing kindness, with which the triple God weeps for the denial of mercy, look favorably upon this worthy servant of Christ.” (???) |

| ↟6 | jeb: “I call to you, praying for Peter” (??) |

| ↟7 | jeb: “Peter’s servant is free from the snares of the Devil and all enemies visible and invisible.” |

| ↟8 | jeb: “Pray for me, your servant Gertrude, to the Lord our God and to the Holy Cross of our Lord, and to his mother, we pray… Thy protection is eternal, and Thy servant Peter follows and will do all.” (???) |

| ↟9 | Bobrinskij, A.A., Count. “Kievskie miniatjuri XI veka i portret knjazja Yaropolka Izyaslavicha v psaltyre Egberta, arkhiepiskopa Trirskogo.” Zapiski Imperatorskogo Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo Obschestva. Iss. XII, pp. 351-371. |

| ↟10 | jeb: “the Unhappy.” |

| ↟11 | jeb: an outer garment worn by the ancient Greeks over the left shoulder and under the right. |

| ↟12 | Kondakov, N.P. Bizantijskija emali sobranija A.V. Zvenigorodskogo, p. 271; Vizantijskie tserkvi i pamjatniki Konstantinopolja, p. 187. |

| ↟13 | What exactly the Russian Grand Duke’s title means, in this case, is absolutely impossible to determine, based on available materials. The only case which can be compared to such a general glorification of the prince is the addition of the phrase χραταίος къ ρήξ given to the King of Sicily around the same time. It is possible that the term δίχαιος / “righteous(?)” refers to an honorary title given to Yaropolk at the Papal court or even by the Catholic Church, but this is only a guess. Nevertheless, the term and inscription are entirely in keeping with the tastes and customs of the time. |

| ↟14 | jeb: Yaropolk the Righteous |

| ↟15 | Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Vol. I. pp. 208-209. |

| ↟16 | jeb: A general term for red gemstones: rubies, spinels, garnet, etc. |

| ↟17 | jeb: A form of ceremonial outerwear with long sleeves worn by boyars and nobles in medieval Rus’ and Poland. |

| ↟18 | For an analysis of similar designs on mantles, see Part III below. |

| ↟19 | Kondakov, N.P. Puteshestvie na Sinaj v 1881 godu. Odessa, 1882, pp. 143-152. |

| ↟20 | See the Izbornik (facsimile) published by the Society for the Lovers of Medieval Writing, 1880. |

| ↟21 | jeb: The white foundation upon which an icon is painted, made of chalk, gypsum, or alabaster powder mixed with a binder, similar to gesso. |

| ↟22 | Kondakov, N.P. Istorija i pamjatniki vizantijskoj emali. St. Petersburg, 1892, p. 184. |

| ↟23 | This grammatical error in Matthew’s name is a result of the harmonization of sounds in the Greek language, and is rarely encountered. See Istorija i pamjatniki vizantijskoj emali, p. 278, ex. 2e, Plate VI. |

| ↟24 | The most complete title is shown in a scene of the coronation by the Savior of John and Alexios Komnenos in the amazing manuscript Vatic. lib. Urbin. 2, written in 1128: Christ is surrounded by “mercy and justice” (women in crowns, similar to the one on Irene in our manuscript). John is called simply “Autocrat of to the Romans”, while the younger Alexios is called έν Χω τώ Θ ω πιστός Βασ. and so forth. This coronation rite is briefly described by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in his work De cerimon. aulac byr., vol. I, p. 38; for the later period see Georgios Kodinos’s De officiis, chapter XVII, ed. Bonn., p. 86-89. The patriarch who consecrated the mantle and placed it upon the king, and who then sanctified the crown and placed it upon the emperor’s head at the popular call “άγιος …” (“Holy holy holy”) and “Glory be to God on high,” represented the Savior himself. |

| ↟25 | Smirnov, Ja.I. “Khristianskie mozaiki Kipra.” Vizantijskij vremennik. Vol. IV. 1897 (1-2), pp. 1-93. Aside from the analogous monuments from the 6th-9th centuries mentioned by the author, we can also look at a similar mosaic in the Church of Santa Maria in Domnica in Rome (9th century), a fresco in the church (now underground) of St. Clement in Rome (9th century), and various smaller monuments. But, as this miniature presents a clearly Byzantine character, it appears to be most similar to the (no longer surviving) Our Lady of Pechersk icon, and is in the middle between the versions of that icon and the older Christian forms. |

| ↟26 | jeb: This original icon from 1085 is now lost, presumed to have been destroyed when the Church of the Dormition was demolished in the Khreshchatyk Explosions, set off by the Soviet Army in 1941 when they retreated from Kiev and abandoned it to the Germans in WWII. |