Several of the articles I’ve read about medieval Russian clothing and embroidery have discussed the various kinds of fabric which existed in Kievan Rus’, but none as thoroughly as the article I’ve translated below. The author, V.F. Rzhiga, provides an overview of three categories of fabric which existed in Rus’ before the Mongol Invasion: silks, woolens, and plant-based cloth including linen, hemp, and cotton. Along the way, the addresses the various subcategories of fabric within these groups, the words by which they were called in medieval Russian, and provides evidence of their use and origin. This evidence comes from both physical archeological finds, as well as literary mention from the Chronicles and charters of the day. Some were imported from as far away as France, Byzantium, and the Middle East, while others were produced locally. This article provides a great overview on the topic, along with key information about how to interpret various medieval terms for fabric found in period sources.

On the Fabrics of Pre-Mongol Rus’

A translation of A translation of Ржига, В.Ф. «О тканях домонгольской Руси.» Byzantinoslavica. Vol. IV. Prague, 1932, pp. 399-417 / Rzhiga, V.F. “O tkanjakh domongol’skoj Rusi.” / “On the fabrics of pre-Mongol Rus’.”

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

http://kaup.ru/index.php/lib/articles/163-rzhiga-v-f-o-tkanyakh-domongolskoj-rusi.html ]

The question of fabrics in the most ancient period of Russian history is difficult and poorly studied. The current article has as its goal, as much as is possible, to illuminate the main aspects of this question, using both the surviving clothing fragments of the oldest fabrics, as well as testimony of literary monuments of that time.

Evidence of fabrics which existed in the era of pre-Mongol Rus’ are most conveniently considered by dividing them into three groups: 1. silk fabrics; 2. wool fabrics; and 3. linen, hemp and cotton fabrics.

Silk Fabric

Silk fabrics in our earliest times were exclusively imported and primarily were used for formal clothing worn by the upper ruling class and only partly to satisfy the needs of the religious cult. These fabrics were primarily imported from Byzantium. A series of individual words for silk material has survived to modern day, which need to have their meaning disclosed and compared to surviving fragments.

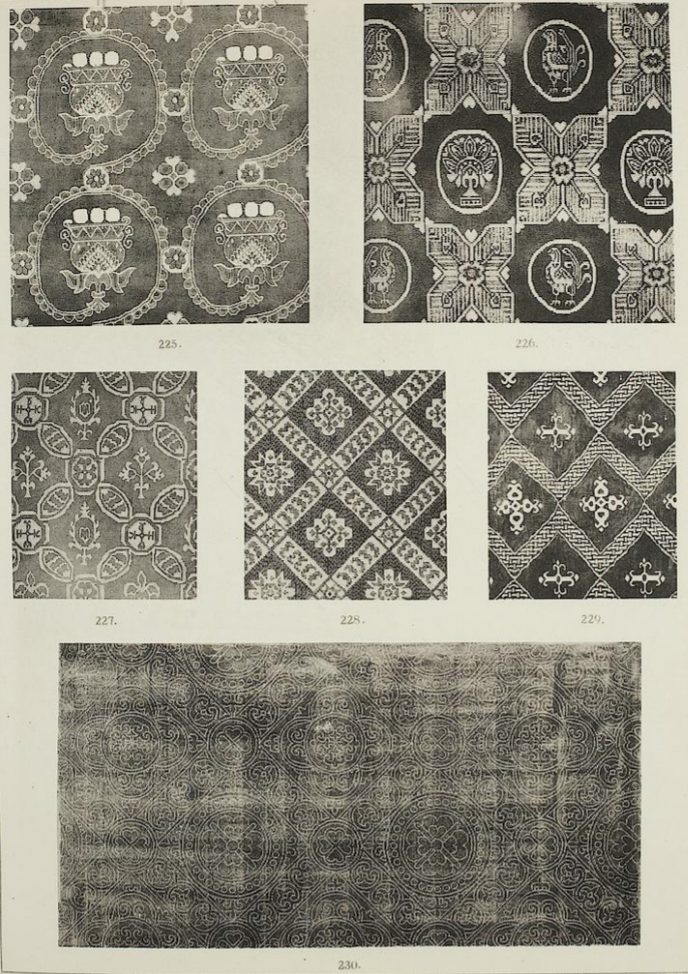

Of the silk fabrics, samite (Rus. аксамит, aksamit) was held in particular value. The Lay of Igor’s Campaign, when describing the booty taken from the Polovtsians, mentions not only “pavoloka” (Rus. паволока, another type of fabric, see more below) but also “precious samite.”[1]Slovo o polku Igoreve, I. izd., pp. 10-11. The context of chronicle references of samite clearly shows that this expensive fabric was used only in upper social strata, by royals and their court. For example, it is known that in 1164, the Greek Emperor sent Prince Rostislav “many gifts … samites and pavoloki and all kinds of patterned fabric (Rus. узорочье, uzoroch’e).[2]Letopis’ po Ipat’evskomu spisku, izd. Arkheografiches. komissii. St. Petersburg, 1871, p. 357. A bit later, in the second half of the 13th century, samite is characterized as a material used for the decoration of kings. Specifically, in the story from the Ipatiev Chronicle about the death of Prince Vladimir Vasil’kovich in 1288, we learn that “his Princess, washed him and wrapped him in samite with lace, as is befitting a monarch.”[3]idem., p. 604. Samite was also worn by courtiers, as can be seen from the Chronicle’s story about the murder of Andrey Bogolyubsky in 1175. “Do you remember, you Jew, whose clothes you came to be in? (said the Boyar Kuz’ma to Ambal, Andrey Bogolyubsky’s murderer.) You stand now in samite, and the prince lies naked.”[4]idem., p. 401. Samite was also used for ecclesiastical needs. A later account from 1288 recalls that an icon had a set of veils that were “embroidered with gold,” and another “of samite with plaques (Rus. дробницы, drobnitsy)”.[5]I.I. Sreznevskij. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkogo jazyka po pis’mennym pamjatnikam. Vol. II, p. 653. jeb: See also Savvaitov, P. Starinnykh russkikh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, v azbuchnom porjadke raspolozhennoe. St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 33: “Drobnitsy: metal plaques or plates – flat, convex, round, oblong, polygonal, in the form of starbursts, clusters, tiles, moon-shapes, icon cases, etc. Small drobnitsy were usually used in lace weaving, embroidery with gold and silver thread, and in decoration with pearls and beads” (jeb: translation mine). The word “samite” comes, of course, from the Greek ἑξάμιτον (hexamiton), which actually means six-threaded (ἑξ – six, μιτον – thread), but how this semantic meaning was associated with the features of samite is unclear to this day. As the earliest samite came to Rus’ from Byzantium, it is there in the history of Byzantine silk production that we must search for data about how the characteristic properties of this fabric came to be. In association with political successes in the 10th and 11th centuries, Byzantium experienced significant economic and artistic growth which was also reflected in the silk fabric industry, which in the period of the 10th-12th centuries reached its heyday. From Constantinople, this branch of industry spread to the islands and into Hellas; aside from the capital, its main centers became Cyprus and Thebes. According to an account from the second half of the 12th century, “In Thebes there lived around 2000 Jews, who were skilled silk workers and purple craftsmen.”[6]Falke, Otto von. Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei. 1913, p. 2. Von Falke, a historian of silk weaving, distinguishes three categories of Byzantine silk from this blossoming from the 10th-12th centuries: 1) fabrics with decorative patterns; 2) fabric conventionally called “satin” (Rus. атлас, atlas); and 3) fabrics with animal patterns. Purely ornamental silk fabric were especially widely-used and have come down to us as a large quantity of small fragments. The pattern on these fabrics primarily consisted of various kinds of rosettes, stars, crosses, and similar basic motifs as part of a network of diamonds, circles, or polygons. One feature of these decorative fabrics was a specifically and purely Byzantine combination of colors: deep purple tones, violet and dark blue, were beloved, with monotone black, green, and yellow patterns. The somber combination of black and violet or dark blue, or brownish and purplish red enjoyed the greatest use. Images of Byzantine clothing on mosaics, illuminations and bone clearly show that their clothing was primarily made up of this type of cloth with plain designs and specific colors.[7]idem., pp. 6-8.

A second category of Byzantine silk material consists of fabrics which are conventionally called “satin”. These are woven especially smooth and firm and stand out for their shiny silk gloss, monochromaticity and linear design. Their predominate color was golden-yellow, and less frequently, red, white, violet, or green. “Their purely linear design,” von Falke noted, “was produced such that the lines seem to be recessed into the surface, as if they were engraved into white metal. In places where they run parallel to the warp, they form sharp furrows…”.[8]idem., p. 8. The prevailing pattern scheme for Byzantine satins came down to “the surface of the fabric, by means of narrow stripes ascending in waves, decomposed into sharp-pointed ovals 60 cm tall, which were arranged in rows, abutting one against another. In four locations, they were joined to one another by small circles. The center of each sharp-pointed oval, surrounded by pearl-shaped bands, was filled with a palmetto with large, plastically embracing curls. The pearl-like band rests upon a smaller palmette and is surrounded by a wreath of strongly curved leaves.”[9]idem., p. 9. Fabrics of this sort were primarily used for ecclesiastical garb and as such are represented by a number of examples that have survived in Western Europe to modern day.

A third category of Byzantine silk is fabric with animal designs.[10]idem., pp. 10-22. This type of fabric was artistically most closely associated with Persian influence, as the main motifs of animals came directly from Persia, including griffons, lions, and eagles, arranged individually or in pairs against either a solid background or, more often, enclosed in circles. These materials are represented by a significant quantity of preserved items and are quite thoroughly described in the inventory of the Papal curia established in 1295. Since this inventory contains many items of fabric acquired much earlier than 1295, and since the Curia was one of the most important consumers of Byzantine silk fabric, the testimony of this inventory gains special importance. Cloth with animal designs is characterized here in large part as red or violet, and it is curious that the material itself is repeatedly referred to as “xamitum”. For example, the inventory’s No. 944 reads: “Unam planetam de xamito rubeo laboratum ad catenas cum grifonibus et aquilis ad aurum filatum de opere Romanie.”[11]jeb: “A planetam of samite, worked in stripes of red with grifons and lions in gold thread, of Roman make.” (??) Under No. 1194, we see: “Xamitum jallum ad rotas in quibus sunt leones et grifones ad aurum filatum de opere Romanie.”[12]idem., p. 21. But in a few cases, samite could also have plant designs, including lilies. Mention of samite with this kind of design is also found in the inventory of the Papal Curia exactly once: “Xamitum violaceum ad lilia aurea de opere Romanie.”[13]idem., p. 21. If we add to this that this category of fabric was, aside from the needs of the religious cult, used only for formal clothing of the upper ruling class, this indicates, for example as is shown in a depiction of the Byzantine court from 11th century,[14]idem., p. 6. then we have all the information we need to imagine what medieval Russian samite may have been like.

If we juxtapose information about samite on Byzantine soil with the surviving items from pre-Mongol Rus’, we can easily be sure that we are dealing with samite in the following circumstances. First of all, outerwear made of samite is depicted on the frescoes of the Spas-Nereditsa Church near Novgorod. The builder of this church, Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich,[15]jeb: sic., the prince shown in this fresco and builder of the church was actually Prince Yaroslav II Vsevolodovich, 1191-1246. is presented here in formal wear holding a church in his hands. His outer cape is made from luxurious material with animal designs inside circles against a dark-red field. The space between the circles is filled by quatrefoil rosettes with pointed ends, while inside the circles eagles are depicted, as can clearly be seen on the prince’s left shoulder. There is no doubt that this material is samite.[16]Prokhorov, V. Materialy po istorii russkikh odezhd i obstanovki zhizni narodnoj, izdavaemye V. Prokhorovym. 1881. Unnumbered plate after p. 78. Cloth decorated with eagles inside circles also appears on the frescoes of Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral, depicting Prince Yaroslav and his family. Yaroslav’s mantle is made of this very material. Cloth with circles without any detailed depiction of what is inside them can also be observed on the members of Yaroslav’s family, who are shown walking behind him. N.P. Kondakov has already noted that “mantles and robes with this kind of design, which in Byzantium had a special name of “eagles,” were among the vestments of the Byzantine court.”[17]Kondakov, N.P. Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i s miniatjury XI veka. St. Petersburg, 1906, p. 38. A cape made of similar material with circular designs is also depicted in the 11th century Trier Psalter on the figure of Yaropolk’s mother.

jeb: Image of Prince Yaroslav II Vsevolodovich in a samite cape with circular designs. Fresco from the Spas-Nereditsa Church near Novgorod, c. 1246.

jeb: Family portrait of Prince Yaroslav “The Wise” Vladimirovich (978-1054). 11th century fresco, Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral. His wife and daughters wear capes of samite.

jeb: Illumination from the Trier Psalter showing Yaropolk Izyaslavich (died 1087) , his wife, and his mother Gertrude standing before the Apostle Peter. His mother is the kneeling figure, in a samite cloak with circular designs. Izyaslavich wears a samite caftan with a pattern of lilies. Mid-11th cent. Image from Кондаков, Н.П. Изображения русской княжеской семьи с миниатюры XI века. Спб, 1906. Табл. 6.

jeb: Enameled depiction of St. Boris on a pendant from the Ryazan’ hoard of 1822. Early 13th century. His cloak is shown in samite with a stylized lily design. Image from Кондаков, Н.П. Изображения русской княжеской семьи с миниатюры XI века. Спб, 1906, с. 49, илл. 7.

Two examples of Byzantine samite with animal patterns which have survived to our time as fragments were found in the tomb of Andrey Bogolyubsky in the Cathedral of the Assumption in Vladimir. Today, they are stored in the Vladimir Musuem, and were at one point published by V. Prokhorov. They were both woven from spun silk. The pattern on the first fragment is that of paired gryphons inside circles. The gryphons stand on their hind legs “with their backs to one another with raised wings, and their heads turned toward one another.”[18]Prokhorov, Materialy po istorii…, p. 84. The circles’ borders are decorated with a pattern of birds with raised wings on either side. The large circles are joined by small decorative circles, while the remaining gaps are filled with paired images of lions. In as far as can be judged from the faded color image, the fabric was a combination of two basic colors – green for the animal figures, and violet as the ground, completely corresponding to those characteristic of Byzantine samite, as was mentioned before.[19]Prokhorov, Materialy po istorii…, plate 5, following p. 86.

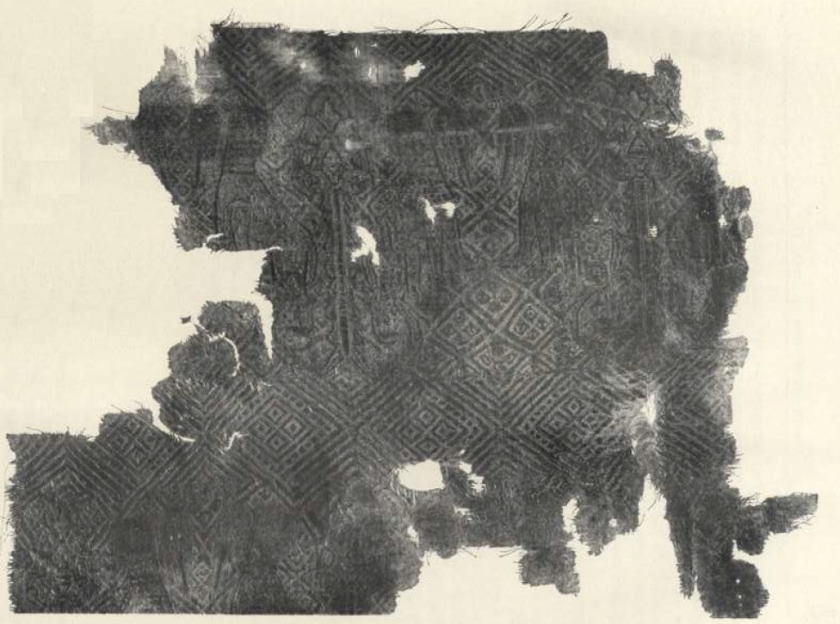

The second fragment of Byzantine samite from the tomb of Andrey Bogolyubsky was woven from spun silk and gold threads. “The patterns on this material,” Prokhorov wrote, “consists of small lions standing one against the other, with their heads raised upward; between them there are two birds standing back to back and in front of the lions’ heads. The birds and lion heads were woven in thin gold threads. Each group of lions is separated by a palmette design. The images of lions, birds and palmettes were woven in thick lines of dark green silk.”[20]idem., p. 84, plate 6 after p. 86. The ground fabric is yellow, but it is quite possible that it faded from an original red. The fragment of this fabric is stored in the State Historical Museum and is shown in illustration 1. The pattern of paired griffons inside circles are also seen in fragments found by Samokvasov in one of the Kiev burial mounds, and also published by Prokhorov.[21]idem., plate 3, after p. 86. We need to think that similar fragments with animal designs inside circles were also encountered in other cases of archeological finds in the region of pre-Mongol Rus’, but by the brief descriptions of these finds, it is not always possible to determine which type pattern was found. As such, it is entirely possible that we are dealing with samite in one of the sarcophagi from under the Church of the Tithes, but the report of this find was quite brief and indicated only that several of the decayed pieces of silk material uncovered there had a preserved “pretty design.”[mfn[Izvestija Arkheologicheskoj komissii. Issue 31. St. Petersburg, 1909. Appendix to Issue 31, p. 73.[/mfn] In view of the limitations of medieval Russian illuminations toward the characteristics of samite, the illustrative material preserved on a set of Bulgarian frescoes from 1259 in the Boyana Church of St. Nicholas are of interest, which depict the church’s founders as an old Bulgarian couple. Particularly curious is the pattern on the clothing worn by the woman, Desislava, which is shown as large circles with an animal design against a red background. Inside the circles, we see paired figures of animals, standing on their hind legs with their muzzles turned toward a tree standing between them. This samite also came to Rus’ from Byzantium. The male clothing. The boyar Kaloyan’s masculine clothing, it appears, was made from a monchromatic dark-violet fabric with a striped pattern which seems to have belonged to the group of Byzantine satins.[22]Minalo. B’lgaro-Makedonsko nauchno spisanie. Sofia, 1909. Year 1, Book 3: “Tsvetni obrazi na starob’lgarski boljari. (Khudozhestven’ pametnik’ ot’ 1259 god’.”

Samite with a vegetative design, specifically with lilies, can be seen, if not from a fragment of fabric, than on the one hand of a miniature from the Trier Psalter, where such a fabric is shown on Yaropolk’s caftan,[23]Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, pp. 16, 99, plates. and on the other hand, on the Ryazan’ barmy, on which we can see Sts. Boris and Gleb’s cloaks made from a material with a woven kriny (stylized lily) design.[24]idem., pp. 49-50; Kondakov, NP., Russkie klady. St. Petersburg, 1896, pp. 83-96, plate XIV. [jeb: See image above.]

Quite similar to samite in both quality and purpose was the so-called olovir (Rus. оловир). Earliest mention of this is found in the Ipatiev Chronicle under the year 1252, which mentions Prince Daniil Galitsky at the time of his arrival in Presburg (Bratislava). It says that Daniil was dressed in “a cope (Rus. кожух, kozhukh) of Grecian olovir embroidered with flat gold lace.”[25]Letopis’ po Ipat. spisku, p. 541. As with samite, olovir was also used in the preparation of items for the religious cult, as can at least be seen from a mention in the Chronicles from the second half of the 13th century: “and a second Acts of the Apostles (Rus. евангелие опракосъ, evangelie oprakos’, “Aprakos”) covered in olovir.”[26]idem., p. 609. The properties of this fabric is suggested by the very word όλόβερος (Greek, oloveros), which means anything purple. Du Cange notes in his dictionary of Greek that the word indicates a silk dye, that is the color, not the silk itself, and served to designate our modern color purple.[27]Du Cange. Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae graecitatis, p. 204. We find a related commentary in his Latin dictionary as well, where the word “holoverus” is described as “purpureus“: “vestes holoverae, quae totae vero colore, αληθίνω, seu purpureo tinctae sunt, absque ullis alterius coloris permistione”.[28]jeb: “Holoverae clothes, which are entirely purple in color, are never mixed with other colors. (???)[29]Du Cange. Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae latinatis. Vol. IV, p. 13. The following quote from Procopius, furthermore, clarifies that the olovir color and dye were befitting of kings: Procopius in Hist. arcana, p. 112, 1 Edit. όλόβερος tincturam et colorem fuisse, qui regum proprius est, … indicat.”[30]ibid. In another quote from Procopius, this purple dye is characterized as “a regal dye, which used to be called olovir” (“βάμματος δε τού Βασιλικού, όπερ καλείν ολόβερον νενομίχασι”).[31]ibid. The solid purple color of olovir sometimes had the same animal designs as samite, achieved by applying gold thread.

There were two periods in the use of gold thread in fabric-weaving in Byzantium:[32]Du Cange, Gloss. ad script. med. et inf. graec., p. 204. the first, dominated by the use of threads made from real gold, and a second, when this thread began to be replaced with thread wrapped with the finest sheets of gold (Goldschlägergold), which was applied to a thin, whitish intestinal membrane and wrapped around a thread of linen, or less frequently, silk or wool. This type of gilt thread was, of course, significantly less expensive than pure gold and came to be widely used starting in the 11th century, and by the 13th century had completely replaced pure gold threads. Examples of medieval cloth-of-gold (Rus. златотканая парча, zlatotkanaja parcha, “gold-woven brocade”) from the first millennium are almost non-existent even in the West, as old, worn cloth-of-gold was burned or destroyed altogether by some method in order to regain the remaining value of the pure gold. This fabric was, it appears, the so-called fofud’ja (Rus. фофудья) mentioned in our early Chronicles, in particular in the Laurentian Chronicle under the year 992, where it says: “And King Leon honored the Rus’ by sending them gifts of gold and pavoloka, and fofud’ya….”[33]Polnoe soranie russkikh letopisej. Vol. I., p. 16. Later, in the Chronicle’s telling of the translation of the relics of Sts. Boris and Gleb in 1115, we read: “Volodimir ordered his men to throw (in the Kievan Chronicle, more specifically, “to divide”, “to scatter”) the pavoloki, fofud’ya, and ornitsy[34]jeb: a type of valuable wool fabric, see below. and squirrel hides into that place where the people had gathered, and then they were quickly and easily able to reach the church.”[35]Letopis’ po Ip. spisku, p. 202; Letopis’ po Lavrent’evskomu spisku, p. 276.[36]jeb: The story says when Prince Volodimir tried to transfer the relics of Sts. Boris and Gleb to a new cathedral in 1115, a great crowd gathered to witness the event and blocked the way. By distributing silver dirhems and pieces of expensive cloth, they were able to disperse the crowd and reach the church. The characteristics of fofud’i are interestingly suggested by a citation which Du Cange gives from the apocryphal Life of St. Aleksey: “There is a Jewish word: a colorful light fabric, the Babylonian renda, or excellent fofud’ja, that is, a royal gold chlamys, which some also call stolon, giphasma (Gr. ύφασμα), or himation…”. The use of cloth-of-gold for outer clothing is known from the Chronicles in instance, specifically, the cloth-of-gold cloak work by the Varangian Yakun:[37]jeb: the Norwegian king Haakon “And Yakun came with his Varangians, and this Yakun was handsome, and he wore a cloak woven of gold.”[38]Letopis’ po Lavr. sp. izd. Arkheogr. Kom. 1872., p. 144, under the year 1024. It further states that during battle, this same Yakun lost his golden cloak: “and Yakun threw off his gold cloak as he fled.”[39]idem., p. 145, under the year 1024. Whole material examples of fofud’ja have not survived, but it is curious that in modern times, during excavations of Chernigov’s Transfiguration Cathedral of the Savior, in one of the sarcophagi uncovered near the northern wall of the cathedral’s northern annex, remnants of clothes were found which were profusely woven with pure gold thread.[40]Vseukrains’ka Akademija Nauk. Zapysky Istorychno-filologichnogo Viddilu, kn. XX., u Kyivi, 1928. Mykola Makarenko. Chernigivsk’yj Spas. (Arkheologichni doslidy 1923 r.), p. 15. Furthermore, Khanenko mentions a few occurences of preserved fragments of fabric which were woven with gold thread.[41]Khanenko. Drevnosti Pridneprov’ja. Iss. V, p. II. Gilt threads may be divided on the one hand into Byzantine thread, which was strongly gilt and which included a yellow silk core, and Cypriot thread, which had a thick linen core.[42]Falke, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 24. The Historical Museum has a number of fragments with shiny thread, and chemical analysis, of course, will show which include genuine gold thread and which are gilt, whether the latter originated from Byzantium or Cyprus, and whether they were produced as a result of the weaving process or through embroidery.

We saw that the second group of Byzantine fabrics consisted of satin materials which were monotone and had a linear pattern, and which were primarily used in ecclesiastical garments. This type of fabric is seen in significant quantities in Western Europe, but to date it seems that no examples have been found from the era of pre-Mongol Rus’. This lack of corresponding finds, however, is not to say that these fabrics were not used in medieval times; we must think that such fragments must be discovered sooner or later.

If samite, olovir, and cloth-of-gold served primarily the royal circles and only in part the church, and Byzantine satin was used primarily for church vestments, then a third category of Byzantine silks with colorful ornamental designs were widely used in the more or less wealthy urban circles. As in Byzantium, this continued in medieval Rus’ as well based on the Byzantine example. That this widely used (in the conventional sense of the term) silk fabric managed to gain sufficient distribution can be seen from the frequent use of the word pavoloka (Rus. паволока). The opinion has been expressed in literature that “pavoloka was a general term for any imported expensive silk and gold fabric,” and that “pavoloka included brocades, cloth-of-gold, Greek olovir, samite, and expensive sorts of fabrics in the widest selection of colors, amongst which most famous were purple, and scarlet or crimson.”[43]Klejn, V. Putevoditel’ po vystavke tkanej VII-XIX vekov, sobranija Istoricheskogo Muzeja. Moscow, 1926, p. 11. However, it is not possible to agree with this opinion. Such a wide meaning for the word cannot be argued based on citations. Quite the opposite, examples of the use of this word clearly show that the category of pavoloka did not include samite or cloth-of-gold, as these and other types of fabric are frequently mentioned alongside pavoloka. One quote about fofud’ya (cloth-of-gold) has already been mentioned. We remember its words: “And King Leon honored the Rus’ by sending them gifts of gold and pavoloka, and fofud’ya….” That samite was not included in the concept of pavoloka can be seen from the Lay of Igor’s Campaign and from the Ipatiev Chronicle. In the former, we read: “And scattering like arrows across the fields, they seized beautiful Polovtsian maidens, and with them gold, and pavoloki, and expensive samite.”[44]Slovo o polku Igoreve, 1st ed., pp. 10-11. In the Ipatiev Chronicle, it speaks about the gifts sent by the Byzantine emperor to Prince Rostislav: “And the king sent many gifts to Rostislav, samite and pavoloka and all kinds of variously patterned fabric.”[45]Letopis’ po Ipat. spisku, izd. Arkh. Kom. St. Petersburg, 1871, p. 357, under the year 1164. There are also no data whatsoever suggesting that olovir should be included in pavoloka. It is true that mentions of this word are scarce, but by all appearances, this fabric was no less valuable or extraordinary in its own right than samite. As such, the meaning of pavoloka needs to be rethought. In order to understand its meaning, let’s look at several other instances of the medieval use of this term. The colorful pattern of medieval pavoloka is indicated by this quotation from Daniel the Prisoner (Rus. Даниил Заточник, Daniil Zatochnik): “Pavoloka, sprinkled with many silks, shows its beautiful face.”[46]Sreznevskij, vol. II, pp. 855-856. Pavoloka was used both for clothing by the wealthy, as for other purposes. In the 12th-century Troitsky Sbornik‘s parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, we read: “For you dress up and go out in your pavoloka and marten.” Further, it says: “For you live richly upon the land, and walk about in crimson and pavoloka.”[47]ibid. Pavoloka was used to make pillows and featherbeds. Daniel the Prisoner mentions: “Bedding of pavoloka, filled with straw,”[48]ibid. while the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus mentions as one of the appurtenances of the wealthy “a bed laid with pavoloka feather cushions.”[49]ibid. Pavoloka is frequently mentioned as an item of coveted military booty. This was true even in the 10th century, when the Primary Russian Chronicle remembers: “And Oleg arrived in Kiev, carrying gold and pavoloki…”.[50]Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 19. This was still true in the 12th century when, according to the Lay of Igor’s Campaign, pavoloka was included in the spoils of war received after victory over the Polovtsians.[51]Slovo o polku Igoreve, p. 10. Pavoloka is also mentioned among the honorary gifts given in international relations, specifically given by the Byzantine emperor to Rus’ princes, and by Rus’ princes to the Hungarians. When seeing off Princess Ol’ga with great honor, the Byzantine emperor “gave her many gifts, gold and silver, pavoloka and various vessels, and let her go, having accepted her as his own daughter.”[52]Letopis po Lavr. sp., p. 60, under the year 955. Later, in 1151, the Russian princes “Vyacheslav and Izyaslav gave unto each other great honor, and both gave of themselves many precious gifts, clothes and villages, vessels and pavoloki, and every kind of gift.”[53]Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 290. Pavoloka is also mentioned as a kind of gift which the Rus’ princes exchanged. In the Ipatiev Chronicle, under the year 1146, we find: “And then Gyurgi sent to him (that is, to Svyatoslav) many gifts, pavoloka and furs, and to his wife, and to his household did he send great gifts.”[54]idem., p. 240. Pavoloka had long been a popular item in the trade between Rus’ and Byzantium. Further, while speaking about his interest in Pereyaslavl on the Danube, Svyatoslav mentions that various goods arrived there from all lands, in particular from Byzantium: “from the Greeks, pavoloka, gold, wine and various vegetables…”.[55]idem., p. 44, under year 969. There is reason to conclude that in the 10th century there was increased demand from Russian merchants for pavoloka, such that in its treaty with Igor’ in 945, Byzantium was forced to set a limit on the maximum amount of pavoloka Russian merchants could buy, set at 50 zalotniki or 175 rubles per person. On the other hand, because of this increased demand for pavoloka, it became a kind of currency in Byzantium, against which the value of other goods could be measured, for example, the price of slaves. In the same treaty between Igor’ and the Greeks in 945, the price of a slave was defined as 2 pavoloki, and as the market price of a slave according to the Rus’ Law was approximately 35 rubles, and as according to Igor’s treaty the value of a Russian prisoner was set at 10 zolotniki (that is, also 35 rubles),[56]Aristov, N. Promyshlennost’ drevnej Rusi. St. Petersburg, 1866, p. 281. it becomes clear that the price of a bolt of pavoloka was 17.5 rubles, and as a result, each Russian merchant according to the contract was able to acquire no more than 10 bolts.

So, pavoloka was a multi-colored silk fabric, which played quite a significant role in trade and home life in pre-Mongol Rus’. This fabric was quite thick, as opposed to a thinner sort of silk which was called koprina (Rus. коприна). The difference between pavoloka and koprina is excellently illustrated by a famous legendary story about the pavoloka and koprina sails which the Rus’ and the Novgorod Slavs sewed for themselves when returning from Constantinople. The pavoloka sails survived the journey, while the Novgorodians’ koprina sails were destroyed by the wind. There is also another story, albeit later, about the thinness of koprina silk, originating in the 14th century. “In soft clothing…, from fabric woven from linen and koprina.”[57]Spisok Slov Grigorija Nazianzina XIV v. (Sreznevsky, vol I, p. 1281). As for our preference for the use of thin, soft grades of silk, one can refer to the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, which mentions “a bed of straw with woven linens of soft silk.”[58]Sreznevskij, Svedenija i zametki, Vol. I, no. 20, p. 30. We have already shown that the categories of silk which enjoyed the greatest use, served the more or less well-to-do urban strata. These fabrics, as we saw, were known for their famous variegated colors and their use of ornamental, rather than animal, patterns, with various types of rosettes, stars, crosses, and various other basic motifs inside a network of diamonds, circles, or other polygons. Examples of these kinds of images can be seen in von Falke’s second volume, in illustrations 225-230.[59]Falke, Otto v. Vol. II., plates after p. 6. Pavoloka is also mentioned among the estate of Andrey Bogolyubsky, which was plundered after his death: “And the townsfolk of Bogolubets plundered the house of the prince, and they did divide amongst themselves the gold and silver, clothes and pavoloka, an estate which was beyond measure.”[60]Letopis’ po Ipat. spis., p. 402, under year 1175. It must be noted that in medieval Russian written works, we also encounter several other works for silk fabric, such as godovabl’ (Rus. годовабль),[61]Sreznevskij, Vol. I, p. 536; Lubor-Niederle, Prof. Dr. Zhivot starych Slovanu. Dil. I, svazek II. Prague, 1913, pp. 412-413, ex. 4; Berneker. Slavisches etymologisches Woerterbuch. p. 316: “годовабль: a word of German origin, compare to the German Gottgewebe“. oksiya (Rus. оксия),[62]Sreznevskij, Vol. II, p. 653. and brachina (Rus. брачина);[Niederle, op. cit., p. 414, ex. 1.[/mfn] but, the first two works were generally speaking little used and were used primarily in translated works; the latter, although it was encountered in Russian texts such as the Lives of Sts. Boris and Gleb and the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, had a meaning of silk fabric in general (cf. the citations in Sreznevskij, vol. I, p. 175).

Speaking about silk fabric, and in particular cloth-of-gold, it would be impossible not to mention also that, as in Byzantium, goldwork embroidery (using gilt thread) was also well known in Rus’. It was used for both the religious cult, as well as in daily life among the upper classes. In 1146, Izyaslav plundered the Church of the Ascension in Putivl, including ecclesiastical vestments embroidered with gold.[63]Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., sp. 237. When a church burned in Vladimir in 1183, the Chronicles attest that many “clothes embroidered with gold and pearls [were burned], which were hung on holidays in two rows from teh Golden Gates to the Church of the Holy Mother, and from the Holy Mother to the bishop’s court in two miraculous rows.”[64]idem., p. 426. Later, in the second half of the 13th century, Vladimir Vasil’kovich installed in the Church of St. Yuriy “samite vestments, embroidered with cherubim and seraphim in gold and pearls,” and “indit’ya (Rus. индитья, throne covers) embroidered all over in gold,”[65]idem., p. 609. and in Vladimir “curtains embroidered with gold, and others of samite with plaques.”[66]ibid. Goldwork embroidery was also used in everyday life among the upper classes. For example, we know that mantles (Rus. оплечье, oplech’e) were embroidered with gold. When describing the Battle of Lipetsk in 1216, the Laurentian Chronicle writes: “For behold, you have come bearing goods, and you shall have horses and armor and clothes… and yea you shall have a mantle embroidered with gold, if you kill and do not leave a single person alive.”[67]Letopis’ po Lavr. sp., p. 470. Gold embroidery was also found on the cuffs in the tomb of Yaroslav the Wise’s eldest son, Vladimir Yaroslavich, who died in 1052 and was buried in Novgorod’s St. Sophia Cathedral. This tomb was recently opened in Novgorod, and inside was found preserved clothing with goldwork on the cuffs. This embroidery was done on pink fabric with gilt thread. The pattern from this embroidery can be seen on illustration 2.[68]This photograph was obtained through the assistance of A.B. Oreshnikov, to whom I am deeply grateful.

Footwear was also embroidered with gold. Under the year 1252, the Chronicles mention that Daniel Galitsky’s outfit included “shoes of green leather, embroidered with gold.”[69]Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 54. Formal clothing was also decorated using patterned braid embroidered with gold, which was called “lace” (Rus. кружево, kruzhevo). We already mentioned that the same Daniel Galitsky’s attire included “a cape of Greek olovir, embroidered with flat gold lace.”[70]idem., p. 541. A bit later, in 1288, when describing the funeral of Vladimir Galitsky, the Chronicle says that he “was wrapped in samite with lace.”[71]idem., pp. 187, 220. To conclude this category of golden material, it is necessary to mention that silk fabric was also imported from the East, but this question requires preliminary development based on archeology. It is only possible to note that a number of such fabrics from the pre-Mongol period have already been found. This includes, for example, one of the fragments from the tomb of Andrey Bogolyubsky, a light, striped fabric with blue, yellow, and red stripes decorated with cross-shaped rosettes. This fragment was at one time published in a work by Prokhorov,[72]Prokhorov, V. Materialy po istorii russkikh odezhd. 1881. Plate 7, after p. 86. and a small segment of it is now stored in the State Historical Museum. The same work also reproduced several other examples of Eastern silk fabrics found in burial mounds.[73]idem., plates 1 and 2, after page 86.

Wool Fabric

Moving on to wool fabric, it is necessary to mention that even in earliest times, they were of dual origin in Rus’. The best, most expensive types were imported from abroad, while simpler and coarser sorts were produced at home. How large this import trade of foreign cloth is difficult to say. It is only possible to establish that this cloth was imported from the West, in particular from France, either by sea through Novgorod, or overland through Galician Rus’. Only two mentions of French cloth on pre-Mongol Rus’ soil have survived. In the charter given by Prince Vsevolod to the Church of St. John the Baptist in Petryatin Court (1130-1135), and which among other things established the conditions for entry into the Ivanovo organization of merchants,[74]jeb: Also called the “Ivan’s One-Hundred,” the first Rus’ guild, which existed in Novgorod in the 12th-15th centuries. Primarily, the merchants were traders in wax and honey. it says: “And whosoever wishes to enter the Ivanovo merchant guild shall give the merchants the base contribution of 50 silver grivny, and a thousand pieces of Ip’sky[75]Sreznevskij, vol. III, p. 615. (that is, Ypres[76]Ypres, a trade city in Flanders) cloth. It is curious that the Ivanovo guild also settled debts with the bishop in Ypres wool when it invited him to preside over church holidays. This trade in Ypres cloth, which began early in Novgorod, would later not only continue to survive but seems to have grown even larger. It is known that Grand Prince Ivan Vasil’evich III[77]jeb: The first ruler of Russia to call himself tsar’. Grand Prince of Moscow and of All Rus’ from 1462 to 1502. Grandfather of Ivan IV “The Terrible”. during his trip to Novgorod received as a gift from various persons 70 postavs (1 postav was about 15-30 meters) of Ypres cloth.[/mfn]Savvaitov, P. Opisanie starinnykh russkikh utvarej, odezdh, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora. St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 138.[/mfn] One of the forms of French cloth was skarlat (Rus. скарлат), an expensive woolen cloth dyed purple. The earliest mention of skarlat in Rus’ is found under the year 1287 in the charter of Prince Vladimir Vasil’kovich, where we read: “And I have purchased the village of Berezovich from the Yuryevichi from Fodork Davydovich, and I have given to him 50 grivny of silver, 5 cubits of skorlat, and plate armor.”[78]Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 595. Later, in the 14th century, trade in wool cloth became especially developed.[79]Aristov, N., Promyshlennost’ drevnej Rusi. St. Petersburg, 1866, p. 213, ex. 666.

To this category of foreign woolen materials which were imported during the pre-Mongol period of Rus’, we should add so-called “chain mail” fabric (Rus. кольчужная ткань, kol’chuzhnaja tkan’), which was a wool fabric with small metal spirals and rings woven into it, and which was found in burial mound “b” in the Petersburg province in Unotischi, as well in the Baltic region. A.A. Spitsyn suggested that this fabric “may have been the vatmal (Rus. ватмал) which Gotlanders used to trade in the 12th century and, it seems, later.”[80]Spitsyn, A.A. Kurgany Peterburgskoj gubernii (Materialy po arkheologii Rossii). No. 20. p. 32. Two pieces of this fabric were published by Spitsyn.[81]idem., plate XVI, Nos. 15-16.

Alongside these foreign wool fabrics, we evidently very early on cultivated our own production of woolen cloths. Based on materials from the burial mounds of the southern Ladoga region, archeologists have already noted that they encountered two types of woolen cloth: “a rougher type, which in appearance was quite similar to that used to this day for Little Russian caftans (svitki), and another, which was thinner and somewhat similar to modern woolen material.”[82]Brandenburg, N.E. Kurgany Juzhnogo Priladozh’ja. (Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, no. 18). St. Petersburg, 1895, p. 27. One of the types of locally-produced woolen material appears to have been called ornits’ (Rus. орниць). We can conclude this based on two quotations, one by St. Kirill of Turov, which says: “Shave your head, lo, and wear clothes of black woolen cloth,”[83]Sreznevskij, vol. III, p. 615. and another from the Studite Charter of 1193, where monks are recommended in wintertime to wear no more than two layers of black ornits‘: “It not befitting for monks to wear more than two layers in the winter, for befits them to take joy in the coldness, and by wearing no more than two svity[84]jeb: svita, a type of outer clothing, long, with no sleeves. sewn from thick black ornits’, they are sped upon their way and warmed by them and feel not the ferocity of winter.”[85]Opisanie slavjanskikh rukopisej Moskovskoj sinodal’noj biblioteki. Section III, part 1. Moscow, 1869, p. 263. In addition, it should be noted that from the 14th century, monks were banned from sewing their clothing from German cloth.[86]Sreznevskij, vol III, p. 615. If this prohibition can also be applied to earlier times, then there is no doubt that ornits’ was a woolen fabric of native production. The question of further understanding the properties of woolen fabrics from pre-Mongol Rus’ can be delivered only through the widest and most systematic collection of fragments uncovered in burial mounds, and their technological and chemical study. In the digest of the Moscow Section of the Academy of Material Culture released in 1928, two interesting analyses of 10th-12th century burial mound fabrics were released. Both fragments were from the territory of the Vyatichi. The first was discovered in a dig by N.I. Bulychev in the settlement of Kokhano in the Mosalsky district of the Kaluga province (Collection of the State Historical Museum, No. 25788/2). Analysis revealed, among other things, the nature of the fiber which formed the fabric was rough sheep’s wool, determined that the yarn was dyed a dark brown using vegetable dyes with an alum mordant, and revealed the thread weave system, which turned out to be quite simple, which today is called “plain weave” and is used to this day for linen fabric.[87]Gos. Akad. Istor. Mater. Kul’t. Moskovsk. Sekts. Sbor. I. K decjatiletiju Oktjabrja. Moscow, 1928, pp. 33-35, illus. on p. 34. Analysis of another wool fabric from the 10th-12th cent. from a dig by A.A. Spitsyn on the Dnieper River in the Smolensk province (collection of the State Historical Musuem, No. 42796) provided even more interesting results. This fabric was also made of sheep’s wool, dyed dark brown with vegetable dyes and an iron mordant. The weave of this fabric was completely different than in the previous example, specifically a 4-thread so-called twill weave, consisting of a weft thread which passes between alternating pairs of warp threads, and on each subsequent pass is staggered by one heddle. This type of weave is today generally used for the weaving of woolen fabrics and is reminiscent of a rough cheviot fabric.[88]idem., pp. 35-37, illus. on p. 36. These analyses further show that in our earliest times, various forms of woolen fabrics were being produced. And, if we ask ourselves which type of wool cloth was the so-called ornits’ we mentioned, then it is impossible not to assume that it was not the former, primitive plain-weave fabric, but rather the more complex twill weave. Is it possible that this more complex weave is indicated by one detail in the quote we mentioned above: the clothing recommended to monks is characterized here as sufficient to protect one from the winter cold because it was “sewn from black ornits’.” That this ornits’ was not a primitive fabric is also suggested by its mention alongside pavoloka in the Ipatiev Chronicle and alonside pavoloka and cloth-of-gold in the Laurentian Chronicle under the year 1115, when Vladimir Monomakh, in order to disperse the crowd during the transfer of Sts. Boris and Gleb’s relics, ordered his men to throw lengths of various fabric into the crowd: “Volodimir ordered his men to scatter the pavoloki, and ornitsy, and squirrel hides in order to disperse the people…”.[89]Letopis’ po Ipatsk. sp., p. 202. We also read the same in the Ipatiev Chronicle as in the Laurentian Chronicle: “And Volodimir ordered his men to scatter the pavoloki, fofud’ya, and ornitsy, and squirrel hides…”.[90]Letopis’ po Lavrent’evsk. spisku, p. 276. Incidentally, let us make a correction to Sreznevsky’s Dictionary. There we find two words without any clarification as to their meaning: one is “orin’ts’” (Rus. ориньць),[91]Sreznevskij, vol. II, p. 706. and the other is “or’nitsa” (Rus. орьница).[92]idem., vol. II, p. 711. The first is illustrated by the citation we gave above from the Studite Charter, but there is a typo in this quote. In the Dictionary, we see written “of black orin’ts’” while the manuscript says “of black ornits’.”[93]Rkp. Gos. Ist. Muzeja, v. Sinod. Bibl. No. 380 (330), folio 223 rev. It follows then that the word is not “orin’ts’,” but rather “ornits’.” As such, the form “or’nitsa = ornitsa” (Sreznevsky, vol. II, p. 711), and the declension to the accusative plural case “ornitsa” is incorrect. Thus, rather than two words in Sreznevsky’s dictionary (orin’ts’, or’nitsa), we should instead see one word, ornits’.

Aside from the types of woolen fabric listed above, there was another fabric known in earliest times which was particularly rough in its material and its weave, and which was used for so-called hair shirts (Rus. власяница, vlasjanitsa). In Nestorov’s Life of St. Theodosius, the hair shirt is characterized as “a svita of hair, sharp on the body.”[94]Sreznevskij, vol. I, p. 275.

Wool was used not only for fabric, but also in felt making. Blankets (Rus. полсти, polsti) or bolts of felt were created, which were primarily used in the construction of tents; from this, tents which were covered in wool were called a “p’lst’nitsa” (Rus. пълстьница). There are repeated mentions of these polstnitsy. For example, in the Laurentian Chronicle under the year 1207: “… and having kissed them, he ordered them to sit in the tent, while the Grand Prince himself sat in a polstnitsa,”[95]Letopis’ po Lavrent’evskomu spisku, p. 409. or in the 1st Novgorod Chronicle: “And behold, Gleb, before their arrival, dressed his nobles and his brothers and the filthy Polovtsian multitude in armor, and laid them down in polost’nitsy similar to tents, and bade them to drink.”[96]PSRL, vol. III, under 1218, p. 36.

Linen, Hemp, and Cotton Fabric

Let us turn next to fabric made from plant material, especially that made of linen and hemp.

These fabrics were, of course, primarily of local production. As early as the Prince Yaroslav’s Charter on the Ecclesiastical Court, we can see that flax and hemp were being cultivated and that the production of canvas was already a common occurrence: “If a man should steal hemp or flax or any kind of grain, the bishop shall give half the fine to the prince. So too for a woman. If a man should steal any white clothes, or canvas, or other cloth, the bishop shall shall give half the fine to the prince, and likewise for a woman.”[97]Vladimirskij-Budanov, M. Khristomatija po istorii russkogo pravda. Iss. I. Kiev, 1876, pp. 204-205. The production of linen was also performed in the monasteries. In Nestorov’s Life of St. Theodosius, there is mention of a monk who made linen: “there was a monk there who, with his own hands, acquired a small estate through the production of linen.”[98]Sreznevskij, vol. II, p. 956. Linen and hemp fabric started early on to be differentiated into classes based on the thoroughness of its processing. On the one hand, rough fabrics were produced which were called “sackcloth” (Rus. яригь, jarig’) and “canvas” (Rus. тълстина, t’lstina, based on a root meaning “thick”). Canvas was used as sails by the Novgorod Slavs, as can be seen from a story in the Primary Russian Chronicle under the year 907. In addition, canvas could be bleached in order to achieve the “white clothes” or “canvas” mentioned in the Yaroslav Charter. This was used primarily used for underclothes. Thinner linen cloth appears to have been known as chastina (Rus. частина), and was sometimes imported from abroad. The Smolensk Charter of 1229 calls out: “And when there is a German visitor in the city, he shall give the prncess a bolt of chastina…”.[99]Russkie Dostopamjatnosti. Part II. Moscow, 1843, pp. 259-260. But, in any event, domestic linen production was already developed to the point that it was used to produce not only canvas and underclothes, but also tablecloths, veils, and polavochniki (Rus. полавочники), or wide towels used to cover benches. An indication of this production exists by 1150, in a charter given by the Prince of Smolensk Rostislav Mstislavich to Bishop Manuel, which as part of the taxes for the city of Toropets includes: “a polavochnik, two tablecloths, and three veils.”[100]Dopolnenija k Aktam Istoricheskim, sobrannym Arkheograficheskoj Komisseju. Vol. 1. St. Petersburg, 1846, p. 8.

As for physical finds of linen fabric from pre-Mongol Rus’, aside from fragments found in burial mounds and subject to recording and analysis, we should mention the famous altar cloth (antimins) from 1149 from Novgorod’s Church of St. Nicholas on Yaroslav’s Court. Along its rectangular edges there is an inscription written in 12th century semi-Uncial (Rus. полуустав, poluustav).[101]Morozov, F. “Antimins 1149 (6657) goda.” Zapiski otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XI. Petrograd, 1915. This altar cloth is made of fine, rather than rough, linen canvas, and based on the properties of the fabric, may have been characteristic of local production.

Let us conclude with a few words about cotton fabrics. Of all types of cloth, these are the least well preserved in all respects, having not survived in any physical examples from pre-Mongol Rus’, nor in a literary sense; and yet, it is nevertheless impossible to affirm that they did not exist in earliest Rus’. This is because Eastern cotton fabrics like zenden’ (Rus. зендень) and calico (Rus. миткаль, mitkal’), which became well known in our country much later,[102]Klejn, V. Inozemnye tkani, bytovavshie v Rossii do XVIII v. i ikh terminologija. were most likely also imported into Rus’ even in its earliest days, as their existence in the East is documented by the 10th century. Zenden’ is mentioned by Abu Bakr al-Narshakhi in his description of Bukhara in differing forms (“zandanichi“, “zendèèdjy“, “zendanchi“) and comes from the Bukhara village of Zandana (or Zendene) which gave this fabric its name. This fabric, according to the historian, was produced in many Bukharan villages and was exported to far away lands.[103]Inostrantsev, K. “Iz istorii starinnykh tkanej. Altabasi, dorogi, zenden’, mitkal’, mukhojar.” Zapiski vostochnogo otdelenija Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XIII. 1900 (4), p. 84. al-Narshakhi states that this cloth was made of cotton, as it was also known to be in later times. Another ancient form of cotton fabric was calico. The Russian word for calico, mitkal’, according to Inostrantsev, comes from the Arabic word miskal‘, indicating a defined weight (1 3/7 drachms) as well as a type of gold coin.[104]idem., p. 85. This fabric was well known in Rus’ in later times,[105]Klejn, op. cit. and was documented in the East by the Arabian writer Ibrahim ibn Jakub.[106]Lubor-Niederle, op. cit., pp. 412-413, example 4.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Slovo o polku Igoreve, I. izd., pp. 10-11. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Letopis’ po Ipat’evskomu spisku, izd. Arkheografiches. komissii. St. Petersburg, 1871, p. 357. |

| ↟3 | idem., p. 604. |

| ↟4 | idem., p. 401. |

| ↟5 | I.I. Sreznevskij. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkogo jazyka po pis’mennym pamjatnikam. Vol. II, p. 653. jeb: See also Savvaitov, P. Starinnykh russkikh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, v azbuchnom porjadke raspolozhennoe. St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 33: “Drobnitsy: metal plaques or plates – flat, convex, round, oblong, polygonal, in the form of starbursts, clusters, tiles, moon-shapes, icon cases, etc. Small drobnitsy were usually used in lace weaving, embroidery with gold and silver thread, and in decoration with pearls and beads” (jeb: translation mine). |

| ↟6 | Falke, Otto von. Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei. 1913, p. 2. |

| ↟7 | idem., pp. 6-8. |

| ↟8 | idem., p. 8. |

| ↟9 | idem., p. 9. |

| ↟10 | idem., pp. 10-22. |

| ↟11 | jeb: “A planetam of samite, worked in stripes of red with grifons and lions in gold thread, of Roman make.” (??) |

| ↟12 | idem., p. 21. |

| ↟13 | idem., p. 21. |

| ↟14 | idem., p. 6. |

| ↟15 | jeb: sic., the prince shown in this fresco and builder of the church was actually Prince Yaroslav II Vsevolodovich, 1191-1246. |

| ↟16 | Prokhorov, V. Materialy po istorii russkikh odezhd i obstanovki zhizni narodnoj, izdavaemye V. Prokhorovym. 1881. Unnumbered plate after p. 78. |

| ↟17 | Kondakov, N.P. Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i s miniatjury XI veka. St. Petersburg, 1906, p. 38. |

| ↟18 | Prokhorov, Materialy po istorii…, p. 84. |

| ↟19 | Prokhorov, Materialy po istorii…, plate 5, following p. 86. |

| ↟20 | idem., p. 84, plate 6 after p. 86. |

| ↟21 | idem., plate 3, after p. 86. |

| ↟22 | Minalo. B’lgaro-Makedonsko nauchno spisanie. Sofia, 1909. Year 1, Book 3: “Tsvetni obrazi na starob’lgarski boljari. (Khudozhestven’ pametnik’ ot’ 1259 god’.” |

| ↟23 | Kondakov, Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i…, pp. 16, 99, plates. |

| ↟24 | idem., pp. 49-50; Kondakov, NP., Russkie klady. St. Petersburg, 1896, pp. 83-96, plate XIV. |

| ↟25 | Letopis’ po Ipat. spisku, p. 541. |

| ↟26 | idem., p. 609. |

| ↟27 | Du Cange. Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae graecitatis, p. 204. |

| ↟28 | jeb: “Holoverae clothes, which are entirely purple in color, are never mixed with other colors. (???) |

| ↟29 | Du Cange. Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae latinatis. Vol. IV, p. 13. |

| ↟30 | ibid. |

| ↟31 | ibid. |

| ↟32 | Du Cange, Gloss. ad script. med. et inf. graec., p. 204. |

| ↟33 | Polnoe soranie russkikh letopisej. Vol. I., p. 16. |

| ↟34 | jeb: a type of valuable wool fabric, see below. |

| ↟35 | Letopis’ po Ip. spisku, p. 202; Letopis’ po Lavrent’evskomu spisku, p. 276. |

| ↟36 | jeb: The story says when Prince Volodimir tried to transfer the relics of Sts. Boris and Gleb to a new cathedral in 1115, a great crowd gathered to witness the event and blocked the way. By distributing silver dirhems and pieces of expensive cloth, they were able to disperse the crowd and reach the church. |

| ↟37 | jeb: the Norwegian king Haakon |

| ↟38 | Letopis’ po Lavr. sp. izd. Arkheogr. Kom. 1872., p. 144, under the year 1024. |

| ↟39 | idem., p. 145, under the year 1024. |

| ↟40 | Vseukrains’ka Akademija Nauk. Zapysky Istorychno-filologichnogo Viddilu, kn. XX., u Kyivi, 1928. Mykola Makarenko. Chernigivsk’yj Spas. (Arkheologichni doslidy 1923 r.), p. 15. |

| ↟41 | Khanenko. Drevnosti Pridneprov’ja. Iss. V, p. II. |

| ↟42 | Falke, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 24. |

| ↟43 | Klejn, V. Putevoditel’ po vystavke tkanej VII-XIX vekov, sobranija Istoricheskogo Muzeja. Moscow, 1926, p. 11. |

| ↟44 | Slovo o polku Igoreve, 1st ed., pp. 10-11. |

| ↟45 | Letopis’ po Ipat. spisku, izd. Arkh. Kom. St. Petersburg, 1871, p. 357, under the year 1164. |

| ↟46 | Sreznevskij, vol. II, pp. 855-856. |

| ↟47 | ibid. |

| ↟48 | ibid. |

| ↟49 | ibid. |

| ↟50 | Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 19. |

| ↟51 | Slovo o polku Igoreve, p. 10. |

| ↟52 | Letopis po Lavr. sp., p. 60, under the year 955. |

| ↟53 | Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 290. |

| ↟54 | idem., p. 240. |

| ↟55 | idem., p. 44, under year 969. |

| ↟56 | Aristov, N. Promyshlennost’ drevnej Rusi. St. Petersburg, 1866, p. 281. |

| ↟57 | Spisok Slov Grigorija Nazianzina XIV v. (Sreznevsky, vol I, p. 1281). |

| ↟58 | Sreznevskij, Svedenija i zametki, Vol. I, no. 20, p. 30. |

| ↟59 | Falke, Otto v. Vol. II., plates after p. 6. |

| ↟60 | Letopis’ po Ipat. spis., p. 402, under year 1175. |

| ↟61 | Sreznevskij, Vol. I, p. 536; Lubor-Niederle, Prof. Dr. Zhivot starych Slovanu. Dil. I, svazek II. Prague, 1913, pp. 412-413, ex. 4; Berneker. Slavisches etymologisches Woerterbuch. p. 316: “годовабль: a word of German origin, compare to the German Gottgewebe“. |

| ↟62 | Sreznevskij, Vol. II, p. 653. |

| ↟63 | Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., sp. 237. |

| ↟64 | idem., p. 426. |

| ↟65 | idem., p. 609. |

| ↟66 | ibid. |

| ↟67 | Letopis’ po Lavr. sp., p. 470. |

| ↟68 | This photograph was obtained through the assistance of A.B. Oreshnikov, to whom I am deeply grateful. |

| ↟69 | Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 54. |

| ↟70 | idem., p. 541. |

| ↟71 | idem., pp. 187, 220. |

| ↟72 | Prokhorov, V. Materialy po istorii russkikh odezhd. 1881. Plate 7, after p. 86. |

| ↟73 | idem., plates 1 and 2, after page 86. |

| ↟74 | jeb: Also called the “Ivan’s One-Hundred,” the first Rus’ guild, which existed in Novgorod in the 12th-15th centuries. Primarily, the merchants were traders in wax and honey. |

| ↟75 | Sreznevskij, vol. III, p. 615. |

| ↟76 | Ypres, a trade city in Flanders |

| ↟77 | jeb: The first ruler of Russia to call himself tsar’. Grand Prince of Moscow and of All Rus’ from 1462 to 1502. Grandfather of Ivan IV “The Terrible”. |

| ↟78 | Letopis’ po Ipat. sp., p. 595. |

| ↟79 | Aristov, N., Promyshlennost’ drevnej Rusi. St. Petersburg, 1866, p. 213, ex. 666. |

| ↟80 | Spitsyn, A.A. Kurgany Peterburgskoj gubernii (Materialy po arkheologii Rossii). No. 20. p. 32. |

| ↟81 | idem., plate XVI, Nos. 15-16. |

| ↟82 | Brandenburg, N.E. Kurgany Juzhnogo Priladozh’ja. (Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, no. 18). St. Petersburg, 1895, p. 27. |

| ↟83 | Sreznevskij, vol. III, p. 615. |

| ↟84 | jeb: svita, a type of outer clothing, long, with no sleeves. |

| ↟85 | Opisanie slavjanskikh rukopisej Moskovskoj sinodal’noj biblioteki. Section III, part 1. Moscow, 1869, p. 263. |

| ↟86 | Sreznevskij, vol III, p. 615. |

| ↟87 | Gos. Akad. Istor. Mater. Kul’t. Moskovsk. Sekts. Sbor. I. K decjatiletiju Oktjabrja. Moscow, 1928, pp. 33-35, illus. on p. 34. |

| ↟88 | idem., pp. 35-37, illus. on p. 36. |

| ↟89 | Letopis’ po Ipatsk. sp., p. 202. |

| ↟90 | Letopis’ po Lavrent’evsk. spisku, p. 276. |

| ↟91 | Sreznevskij, vol. II, p. 706. |

| ↟92 | idem., vol. II, p. 711. |

| ↟93 | Rkp. Gos. Ist. Muzeja, v. Sinod. Bibl. No. 380 (330), folio 223 rev. |

| ↟94 | Sreznevskij, vol. I, p. 275. |

| ↟95 | Letopis’ po Lavrent’evskomu spisku, p. 409. |

| ↟96 | PSRL, vol. III, under 1218, p. 36. |

| ↟97 | Vladimirskij-Budanov, M. Khristomatija po istorii russkogo pravda. Iss. I. Kiev, 1876, pp. 204-205. |

| ↟98 | Sreznevskij, vol. II, p. 956. |

| ↟99 | Russkie Dostopamjatnosti. Part II. Moscow, 1843, pp. 259-260. |

| ↟100 | Dopolnenija k Aktam Istoricheskim, sobrannym Arkheograficheskoj Komisseju. Vol. 1. St. Petersburg, 1846, p. 8. |

| ↟101 | Morozov, F. “Antimins 1149 (6657) goda.” Zapiski otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XI. Petrograd, 1915. |

| ↟102 | Klejn, V. Inozemnye tkani, bytovavshie v Rossii do XVIII v. i ikh terminologija. |

| ↟103 | Inostrantsev, K. “Iz istorii starinnykh tkanej. Altabasi, dorogi, zenden’, mitkal’, mukhojar.” Zapiski vostochnogo otdelenija Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XIII. 1900 (4), p. 84. |

| ↟104 | idem., p. 85. |

| ↟105 | Klejn, op. cit. |

| ↟106 | Lubor-Niederle, op. cit., pp. 412-413, example 4. |