Below is my translation of the book Medieval Russian Embroidery (Древнерусское шитьё), by Natalia Andreevna Majasova (1919-2005), an expert in this area of study. Over the many years of her career, she was instrumental in the research and transformation of several collections of medieval Russian embroidered works, first at the Zagorsk State Historical-Artistic Museum-Reserve (the Soviet-era museum built on the site of the Trinity-Sergiev Lavra, a famous monastery outside Moscow), and then later with the Museums of the Moscow Kremlin. This book, published in 1971, is a general overview, with over 50 full-color plates showing examples from the major embroidery centers of Moscow and Novgorod from the 15th-16th centuries, a couple of post-period items from the 17th century, and an in depth introductory article on the subject.

Medieval Russian Embroidery

A translation of Маясова, Н.А. Древнерусское шитьё. Москва, 1971. [Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971]

Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[I have added some helpful information in places, such as links to view images which are discussed but not actually shown in the book (where possible). These footnotes are labeled with my initials (jeb). The remaining footnotes are from the book. In the book, the footnote numbering starts afresh on each page. This doesn’t make sense in the below format which is not paginated, so the footnotes numbers here just increment across the entire work.]

[This translation is from a copy of the book I own in my personal library.]

From the Author

This album is an overview of one form of medieval Russian artistic embroidery – figurative or ecclesiastical embroidery – and does not address ornamental embroidery, which could support a specialized study all its own.

Here, I have captured the period of the greatest flourishing of the art of embroidery from the 14th to the 17th centuries, inclusive. I have selected for publication the most characteristic and significant works of art, allowing the reader to judge the particulars of the development of this artform. Many of these works have inscriptions with dates and the names of their patrons and sometimes of the master artisans, allowing us to date other monuments of medieval Russian art.

The works are organized in chronological order, independent of their intended use or the artistic center to which they are related, allowing us to cover the development of this artform as a whole. I must acknowledge my deep appreciation to V.I. Antonova and N.A. Demina for their assistance with preparing this book for publication.

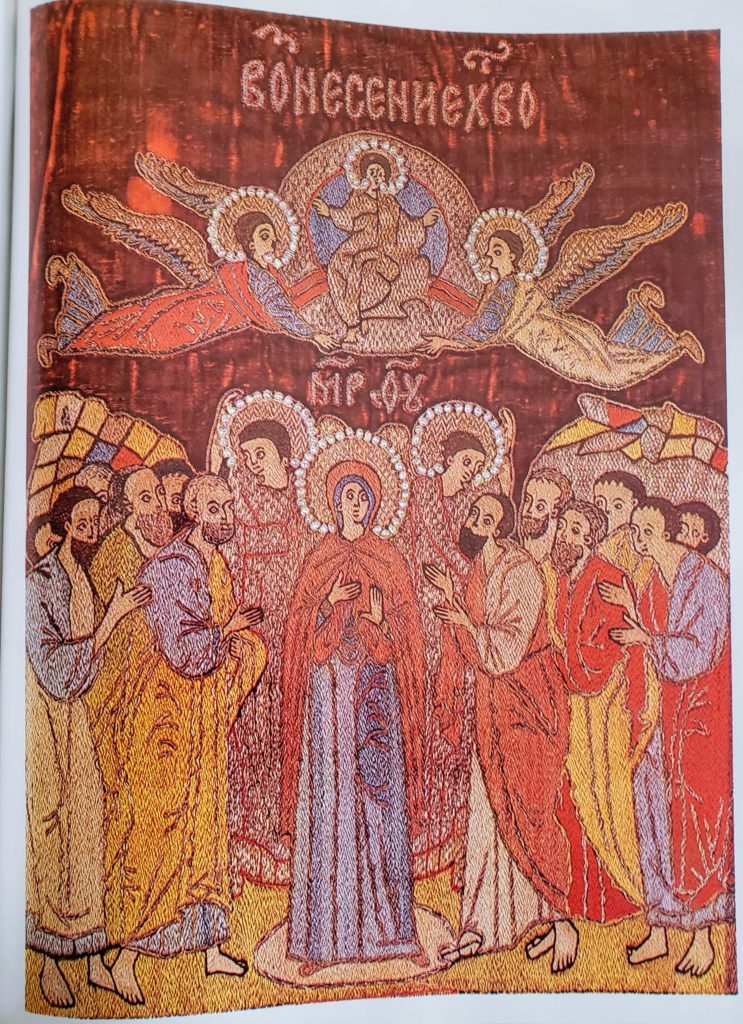

Medieval Russian Embroidery

Works of ecclesiastical[1]The name “litsevoe” [literally “facial”] is assigned to this form of embroidery as a figurative art, due to its depiction of man, his face, and his surroundings, as opposed to ornamental embroidery.[2]jeb: Given that this term is almost exclusively used to discuss liturgical embroidery, I have interpreted this term as “ecclesiastical”. embroidery occupied an important place in the artistic and societal life of medieval Rus’. Their functions were highly varied. Large Aërs and podeai decorated altar screens and the walls of cathedrals; podeai were hung under icons in churches and home chapels, and were sometimes taken in the place of an icon on long journeys. Embroidered images decorated the curtains which closed off the Royal Gates, the veils which decorated altars and altar thrones, the palls on the tombs of the saints, and on the vestments worn by priests and deacons. Epitaphia, sudaria (veils), and gonfalons were used in crowded holiday ceremonies, and flags, embroidered icons and even entire embroidered iconostases accompanied soldiers on their distant campaigns.

Works of artistic embroidery were highly prized in Medieval Rus’. They were meticulously preserved in church and monastery sacristies, and in the houses of wealthy princes and boyars, and were passed down from generation to generation. But, many masterpieces of this art perished in times of fire, enemy invasion, and feudal strife, or decayed from frequent use. For example, in 1183, the chronicles mention that during a fire in the Cathedral of the Assumption in Vladimir, many “fabric items embroidered with gold and pearls, which would be hung on holidays in two rows from the golden gate to the Cathedral of Our Lady, and again in marvelous rows from the Cathedral of Our Lady to the Lord’s palace”[3]Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej [PSRL]. Vol 2, St Petersburg, 1843, p. 127 were destroyed by fire. Such tidings are encountered frequently.

The majority of works of ecclesiastic embroidery which have survived to our time have numerous gaps, rough wear, and later additions. In the 1920s, Soviet museums carried out a methodical scientific restoration of these remarkable monuments to medieval art.[4]This restoration was organized in the early 1920s by the State Central Art Restoration Workshops [GTsKhRM] and their branch at the Trinity-Sergiev Lavra; in 1927, these works were displayed for the first time at the 3rd Restoration Exposition. The principal artisan-restorers of fabric and embroidery were: N.P. Shabel’skaja, T.N. Aleksandrova-Dol’nik, Ju.S. Karpova, K.N. Sishova, M.N. Rozhdestvenskaja, E.S. Vidonova, and A.D. Beljakova (Merkulova). Today, the restorers of the GTsKhRM and artisans at the nation’s most significant museums carry on this work through the use of new methods.

Ecclesiastical embroidery is closely tied to icon painting and fresco. But, although it follows those artforms in subject matter, iconographic schemes, and choice of color, it at the same time has its own features and specificity.

First of all, this was a collective form of art. The cartoon for the embroidery was typically created by an icon painter – the lead iconographer [znamenschik]. This drawing, done in ink on fabric, can be seen, for example, on the large embroidered icons depicting the Archangel Michael and the Apostle Peter (illustration 20, illustration 21), or on the famous podea by Grand Princess Maria, wife of Simeon the Proud (illustration 5, illustration 6). Later, in the 17th century, the artisan frequently would first draw the design on paper, which then would be transferred onto the fabric. Many works have liturgical or donor inscriptions. In most cases, these were drawn out by a different artisan, the “word writer” [slovopisets]. During the 17th century, “herbalists” [travschiki] are also mentioned, who would draw the landscape [travy]. Typically, several artisans would participate on large embroideries, each working on the area in which she was most skillful. For example, the inscription on a 1654 podea with the image of Tsarevich Dmitrij attests that “the labor and care for this podea in pearlwork was done by the wife of Dmitrij Andreevich Stroganov, Anna Ivanovna, while work on the faces and robes and utensils was done by Sister Marfa, called the Great.”[5]Makarenko, N. Iskusstvo Drevnej Rusi. U Soli Vychegodskoj. Petrograd, 1918, p. 91.

Information about the artisans and icon painters is encountered very infrequently prior to the 17th century. But, whereas on many monuments of embroidery we find the names of the donor, this is still extremely important, as in most cases, this indicates the workshop from which the item originated. These workshops or “solaria”[6]These are so named as these were the brightest and cleanest rooms in the house, retained specifically for these workshops. existed in almost every princely and boyar household, in the houses of wealthy civil servants and tradesmen, and in nunneries. Several of these solaria retained a relatively large number of artisans. For example, we know that Prince Afanasia Vjazemskij in the 16th century retained 40 embroiderers.[7]Shlikhting, Al’bert. Skazanie. Leningrad, 1934, p. 33. In the royal solaria of the second half of the 17th century, the number of artisans and apprentices numbered as high as 80 individuals.[8]Zabelin, I.E. Domashnij byt russkogo naroda v XVI i XVII st. Tom II: Domashnij byt russkikh tarits v XVI i XVII st. Moscow, 1901, p. 399. The mistress of the house, herself typically a skilled artisan, would serve as the head of these workshops. The Swedish nobleman Petr Petrej, who served during the reigns of Boris Godunov and Vasilij Shujskij, writes about the wives of noble Russians: “In embroidery, they are experienced and skillful, such that they surpass many embroideresses in pearlwork and their work is exported to distant countries.”[9]“Moskovskie letopisi Konrada Busova i Petra Petreja.” Skazanija inostrannikh pisatelej o Rossii. St. Petersburg, 1851, p. 308.

About the fact that this form of Medieval Russian artwork was well-known beyond its own borders very early on, we have the inventory of the Ksilurgu Monastery on Mt. Athos which, as early as the 12th century, mentions epitrachelia and podeai of Russian make.[10]“Opis’ imuschestva obiteli Ksilurgu 6651 (1147) g.” Akty russkogo na svjatom Afone monastyrja sv. velikomuchenika i telitelja Pantelejmona.” Kiev, 1873(6), pp. 52-53. Also to Mt. Athos, to the Serbian Hilandar monastery, Ivan the Terrible and Tsaritsa Anastasija Romanovna sent in 1556 a katapetasm (a curtain for the Royal Gates) with a depiction of “The Presentation of the Tsaritsa” and saints along the border.[11]Stasov, V.V. “Zametki o drevnej russkoj katapetazme.” Izvestija Imperatorskogo russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva (IAO). Vol. IV, St. Petersburg, 1863, pp. 534-541. In the early 16th century, Tver’s bishop Nil sent the Byzantine Patriarch Pakhomius, amongst other gifts, two embroidered chasubles with depictions of the holidays, and an epitrachelion embroidered with saints.[12]Prodolzhenie Drevnej Rosijskoj Vivliofiki. Part IV, St. Petersburg, 1790, No. 178, p. 3. Medieval Russian embroidery enjoyed well-deserved fame. And, this fame was primarily due to the extreme skill of Russian women. The expressiveness and beauty of image depended on their art, and they filled the plain artist’s design with a vibrant world of multicolored silk.

Every woman in Medieval Rus’ was expected to be able to sew and embroider. Diligence at handiwork was considered to be a special virtue. It is no wonder that the famous work of the 16th century, the Domostroj, which contains the various rules of “worldly wisdom,” particularly emphasizes that “good wives do needlework.”[13]Domostroj Sil’vestrovskogo izvoda. St. Petersburg, 1902, cf. 64, 16, 20, 30, et.al. Embroidering liturgical podeai was considered to be pious work. It was considered a feat if a woman “spent all night without sleep in prayer and needlework, in spinning and handiwork.”[14]”Povest’ ob Ulijanii Osorinoj.” Russkaja povest’ XVII v. Moscow, 1954, pp. 40-41. With this closed lifestyle which a woman of Medieval Rus’ (especially in the upper classes) led, handiwork was almost the only area of creativity available to her. It was not by chance that foreigners arriving in Russia noted: “The best thing that women can do here is to sew well and embroidery excellently in silk and gold.”[15]Izvestie anglichanina, byvshego pri starskom dvore v 1557-1558 gg.” Chtenija v Obschestve istorii i drevnostej Rossijskikh pri Moskovskom universitete (ChOIDR), Book 3, Moscow, 1884, p. 25.

Close to nature and brought up in an everyday life where almost every object was a work of art, amongst marvelous frescoes and icons, women of Medieval Rus’ were able to reflect in their works the artistic tastes and high culture of their time, and to finely convey the diversity and reverberation of color that surrounded them in the real world.

The extraordinary diversity of color and tones that were noticed by medieval Russians attest to the subtlety of their perception. For example, for the color red, they used names like: worm-red, maroon, clove, raspberry, ore-yellow,[16]jeb: yellow with a reddish tinge, orange crimson, lingonberry, currant, vermilion, poppy, firey; for yellow – sand, yellow, saffron, straw, lemon, etc. And the quality and diversity of their embroidered work depended not only on the cartoon that was drawn for them by the icon painter, but also on their taste and skill, on the color of the fabric they selected for the ground, on their selection of multicolored silk threads and their combination with gold, pearls and precious stones, on their application of this or that particular stitch, creating different play of light and shadow.

Tyipcally the “facial” areas, that is, the face and other exposed parts of the body, were embroidered using flesh-colored or grey silk in stem stitch, in which the stitches lie tightly beside one another, or split stitch, where the needle pierces through the middle of the previous stitch, as if splitting it. In fine works (especially in the 15th century) faces were typically embroidered with stitches running either vertically or horizontally. In larger and monumental works, the artisans worked the stitches following the direction of the muscles, so called embroidery “in form,” in order to convey the dimension of the face and body. This method developed primarily in the in the middle of the 16th century, when they also began to emphasize the volume through the use of silks of various shades.

The “non-facial” areas – clothing, surrounding items, landscape, architecture – were embroidered either in multicolored silks, as was characteristic in the 15th century, or in silver and gilt[17]Starting in the 14th century, pure gold threads are rarely encountered. Instead, it was replayed by gilded silver. Such threads are typically called “gilt”. couched threads, especially starting in the mid 16th century. In “couched” embroidery, silver threads are laid over the fabric in parallel rows, and are tacked down onto the fabric using stitches of silk, creating various patterns. Often to give relief to gold threads, other threads, yarn, or thicker material was laid down under the gold. There existed “chased” [po chekannoe delo], “Persian brocade” [po altabasnomu] and “aksamite” [po aksamitnomu] embroidery which imitated chased metalwork or expensive imported fabrics. One of the most difficult methods, technologically speaking, was two-sided embroidery, in which gold and silk threads were passed through the ground fabric, such that both sides of the item received the same image. This method was used to embroidery flags and banners. Frequently, haloes, the contours of the figures, and other details were decorated with pearls. For this purpose, they would first couch down a braided cord [dvojnoj shnurok], over which they would then couch down the string of pearls.[18]About this technique, cf: Shabel’skaja, N.P. “Materialy i tekhnicheskie priemy v drevnerusskom shit’je.” Voprosy restavratsii. 1926(1), pp. 113-125; Kalinina, E.V. “Tekhnika drevnerusskogo shit’ja i nekotorye sposoby vypolnenija khudozhestvennykh zadach.” Russkoe iskusstvo XVII v. Leningrad, 1929, pp. 133-165.

Silk threads for embroidery were used either plain or twisted. Silk was primarily obtained from China or Persia. Gold and silver threads were foil wrapped around a silk core[19]jeb: gold or gilt silver was beaten into a foil, cut into thin strips, and then wrapped around a silk core. cf. modern so-called “Japan thread”, passing thread [volochenye] in the form of thin hair, or gimp [skannaja], where metal thread is intertwined with silk thread.

Gold and silver, as well as precious stones, were also imported. The pearls used were “Gurmish” [“gurmyshskij”] or “Kafim” [“kafimskij”] – imported from India or Persia through Azov or Kaffa[20]jeb: A city in Crimea on the Black Sea, today called Feodosia. These could be round and relatively expensive, or “irregular” and relatively cheaper. Small and medium sized pearls were obtained in many northern rivers.[21]Jakunina, L.I. Russkoe shit’jo zhemchugom. Moscow, 1955, pp. 144-148. Italian brocades were the preferred ground fabric for the majority of items of ecclesiastical embroidery – “Venetian,” predominantly “worm-colored” (red) or azure (light- to dark-blue), and also Western taffeta. In the majority of items, the central section which housed the main image would be of one color, and the border of another. The borders were decorated with images of saints, holidays, scenes from saints lives, or donor and liturgical inscriptions,[22]Due to the nature and size of this publication, liturgical inscriptions are not presented in this work, and name inscriptions are given only where necessary to qualify a depiction. or occasionally ornamentation.

The content of embroidered works was, to a large extent, dependent on its intended use. Veils, for example, typically depicted the saint for whose grave it was intended; epitaphia and Aërs often depicted the Entombment or Lamentation of Christ; sudaria or altar veils often depicted Our Lady of the Sign, the eucharistic lamb, the Crucifixion, or Christ in the Tomb; podeai would carry the image of the icon under which they would hang; etc. But, these canonical requirements only applied to the main image in the center, and not for all types of embroidered objects.

Many Aërs and podeai have survived to modern day featuring varied themes. The content of images on the borders, as a rule, was selected by the donor, and the selection of theme for the embroidery would depend directly on his wishes. This selection, it would appear, was never by chance, but rather was dictated by deep considerations, and not always only by moral or aesthetic nature.

Princes, boyars, the clergy, wealthy civil servants or merchants – these were the upper class of the feudal world who played an immediate, direct role in the social and political life of the country. Their mothers, wifes, sisters and daughters lived through the interests of the men of their households, and would often render a direct influence on the direction of historical events from their chambers. Having married for political reasons from one princedom to another, they were often caught between a rock and a hard place, torn between the duties of being a daughter or a wife, between their attachment to the land of their birth and their new duties. They expressed his entire complex world of sympathy and antipathy, personal passions, and social and political interests through the only way available to them – through embroidered works. These works, donated to churches and monasteries, alongside fresco and icons, spoke in a language of allegory and metaphor understood by medieval man about the questions that interested them.

Understanding the subject of an embroidered work, comparing it with the inscription and the identity of the donor based on concrete historical events, allows us to transfer that monument into the atmosphere of real life, to see the personal experiences and sympathies behind it, and the societal and political views of that living person.

Arising in Rus’ with the acceptance of Christianity, ecclesiastical embroidery formed here, just like icon painting, under the direct influence of Byzantium. But, it developed on soil that was already prepared. Numerous folk embroideries from the 18th-19th centuries which preserve symbolic representations of ancient pagan beliefs, attest to the development of the art of embroidery in Rus’ in the pre-Christian era. It would appear that these distant folk traditions played a significant role in the lush expansion that the art of Russian ecclesiastical embroidery achieved even in the early part of its evolution.

A lot of information about the import of embroidered works of Byzantine art to the cities of Rus’ has come to us through history. But, in the chronicles of the 10th-13th centuries, saints’ lives and other sources mention Russian embroidery as well. In the 11th century, Kiev’s Janchin Monastery had a school of embroidery and fabric, where the first nun from a Russian princely family, Prince Vsevolod’s daughter Janka, “having gathered the young women, taught them writing, and handicrafts, and singing, and sewing.”[23]Russkij biograficheskij slovar’. Vol. 2, St. Petersburg, 1900, p. 158. Anna, wife of Kiev’s Prince Rjurik Rostislavovich (died 1215), “herself engaged in labor and handicraft, embroidering in gold and silver.”[24]Zabelin, p. 545 Many works of embroidery are mentioned in relation to fires and enemy incursions.

In most cases, these mentions talk about embroidery “of gold and silver.” At the same time, various cities are mentioned. It appears that goldwork embroidery was not characteristic of any single artistic center, but was common in Kiev, Novgorod, Rostov, Vladimir, and other cities. This is attested by individual works of embroidery which have survived from the 12th-14th centuries: the epimanikia of Varlaam of Khutyn (died 1193) from Novgorod,[25]Svirin, A.N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1963, pp. 25-27. fragments of embroidery from 12th-13th century Kiev with images of saints,[26]IV vystavka «Restavratsija i konservatsija proizvedenij iskusstva.» Katalog. Moscow, 1963, p. 51. a 12th-century podea in the Museum of History, believed to have come from Novgorod’s Jur’iev Monastery,[27]Svirin, pp. 24-25, illus. on p. 27 and others.

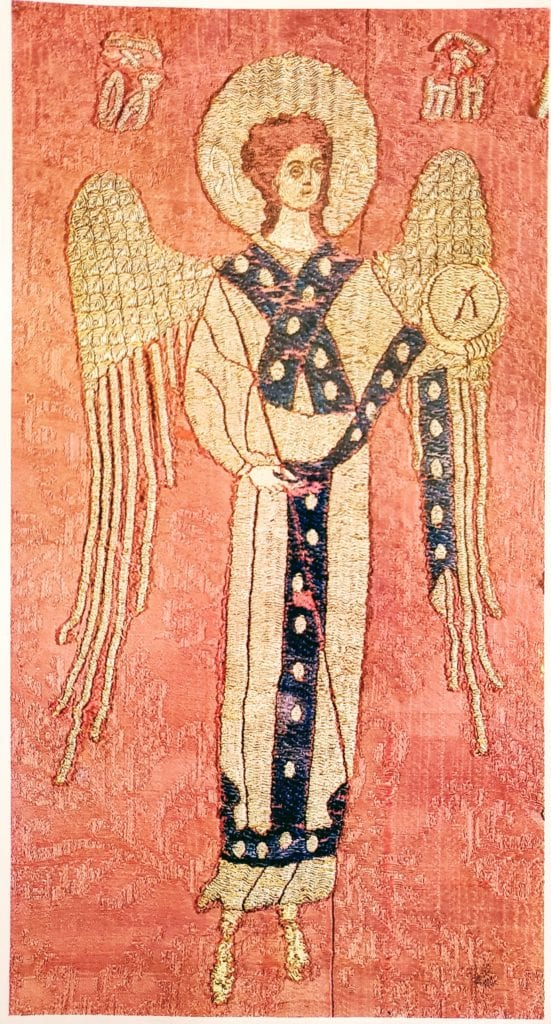

These examples of early goldwork embroidery also include a gonfalon, decorated on each side with an archangel wearing a loros, and holding a staff and mirror. The two images differ not only in the transposition of attributes from left to right as if in mirror image, but also in the contours of the design, in various ornamentation, in the folds of clothing, and in other details. The ground fabric for one item might be a black silk, and for another dark red.[28]Today (since the 18th century?), the ground for both images is a lingonberry-colored satin. The two halves have been separated. It appears that each side had its own design, possibly by different artists.

The better preserved archangel is the one that was embroidered on a black background [Illustration 1]. Most remarkable about his figure are his wide-spread, powerful wings. The bold curve at the shoulders emphasizes their sharply angular lines. Like a predatory bird, his feathers bristle and stretch down to the very ground. The archangel’s strong hand grasps the staff firmly, like a spear. These apparently emphasized features do not correspond to the seemingly fragile figure, with its somewhat large head, narrow shoulders and thin legs. But, the artist’s skill and even this very contrast manages to create a unique originality and charm which distinguish this true work of art.

The form of the wings, which gives the depiction of the archangel a state of tension, and the proportions of the figure speak to the 14th century. Here, echoes of the Palaeologan Renaissance are clearly felt. At the same time, the structure of the face with its sharp nose and round brows, the narrow shoulders, and the aristocratic refinement of the entire image call to mind works of the Rostov-Suzdal’ “school” of the 13th century.[29] See Rostovo-suzdal’skaja shkola zhivopisi.” Katalog. Moscow, 1967. These characteristics allow us to attribute the item to the first half of the 14th century, to monuments of the Rostov-Suzdal’ region, whose orbit included Moscow.[30]D. Ainalov calls this item a “banner” and attributes it to the Novgorod school of the 14th century. (Ainalov, D. Geschichte der russischen Monumentalkunst zur Zeit der Grossfürstentums Moskau, Berlin, und Leipzig. 1933, p. 117) His attribution is seconded by V.N. Lazarev and A.N. Svirin.

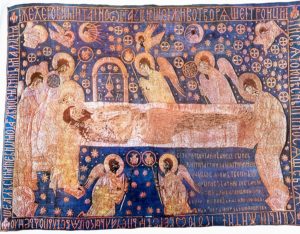

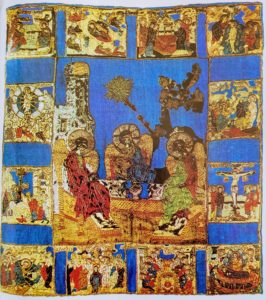

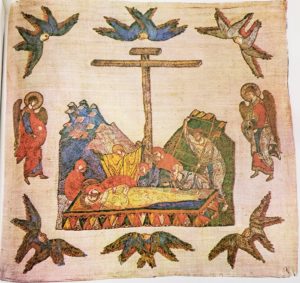

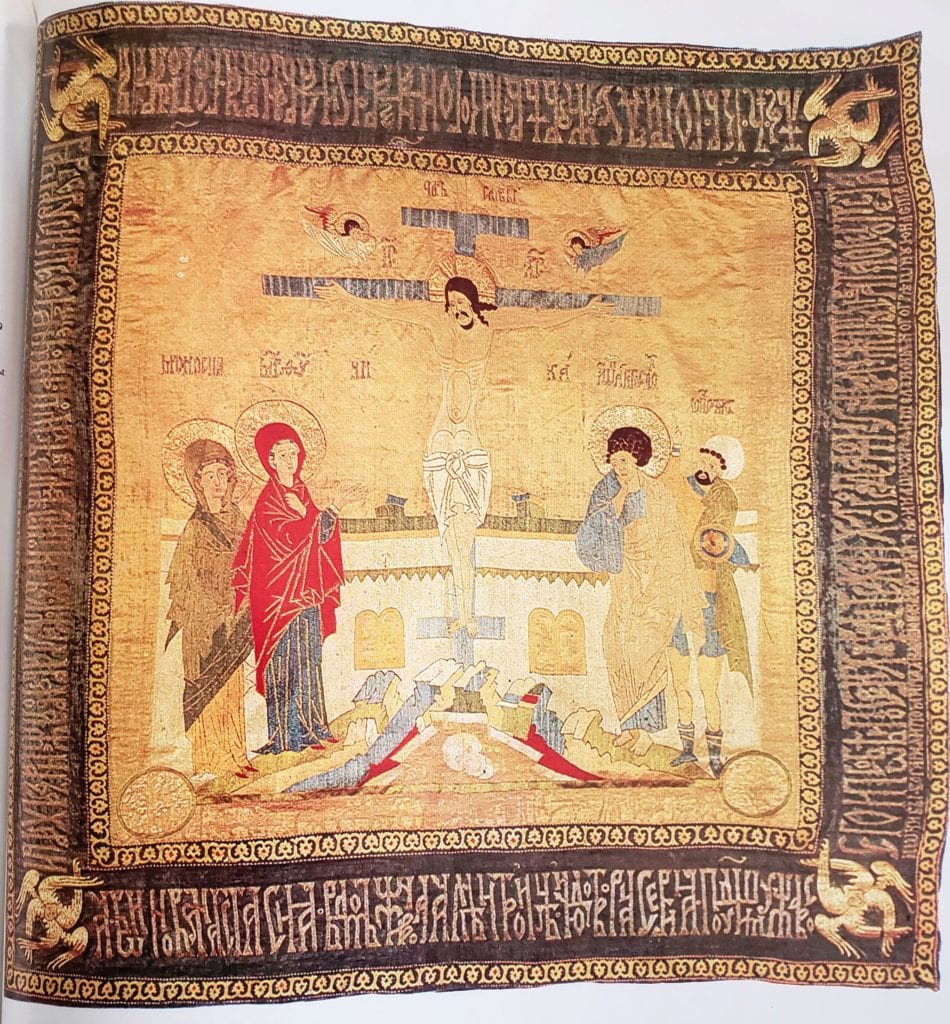

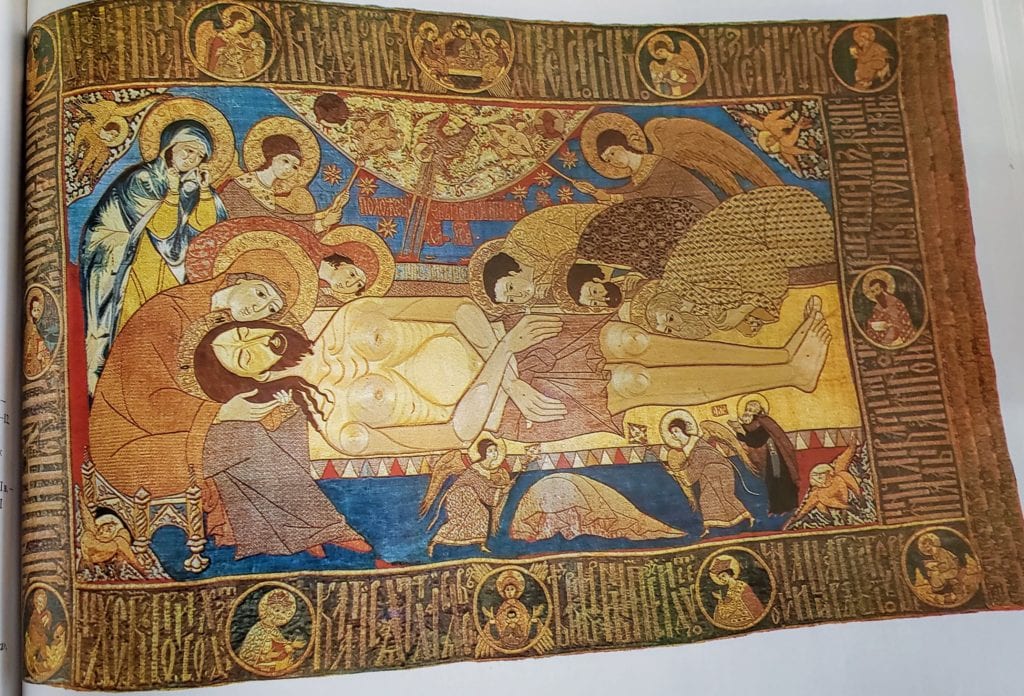

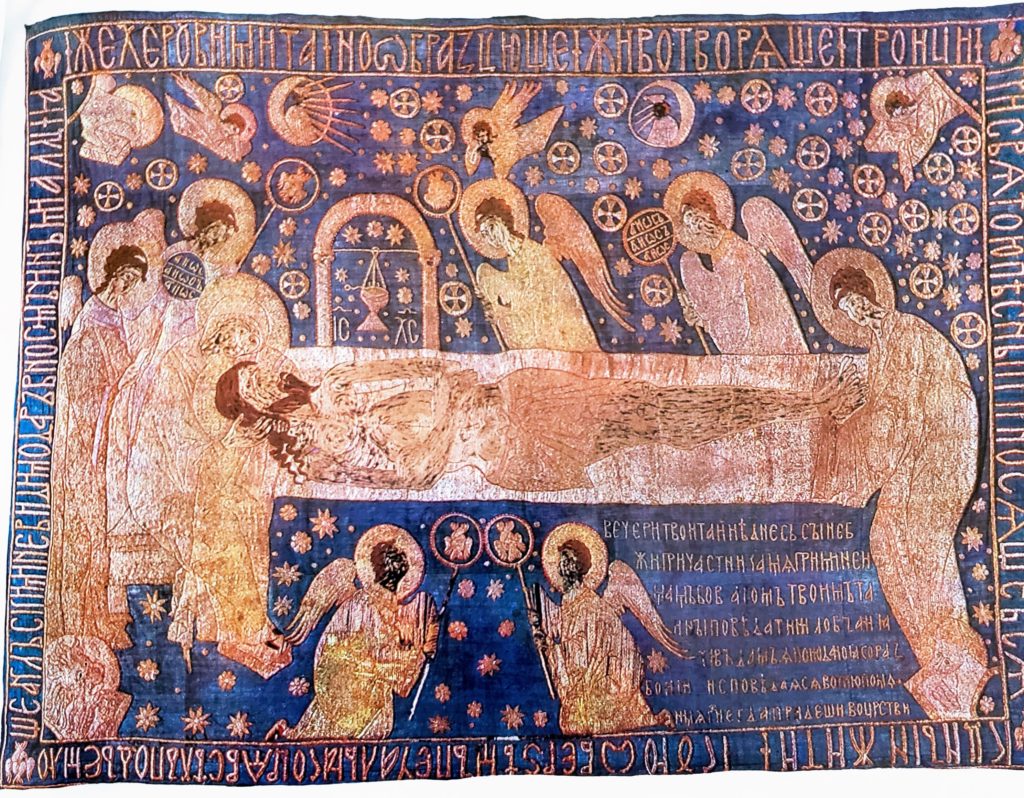

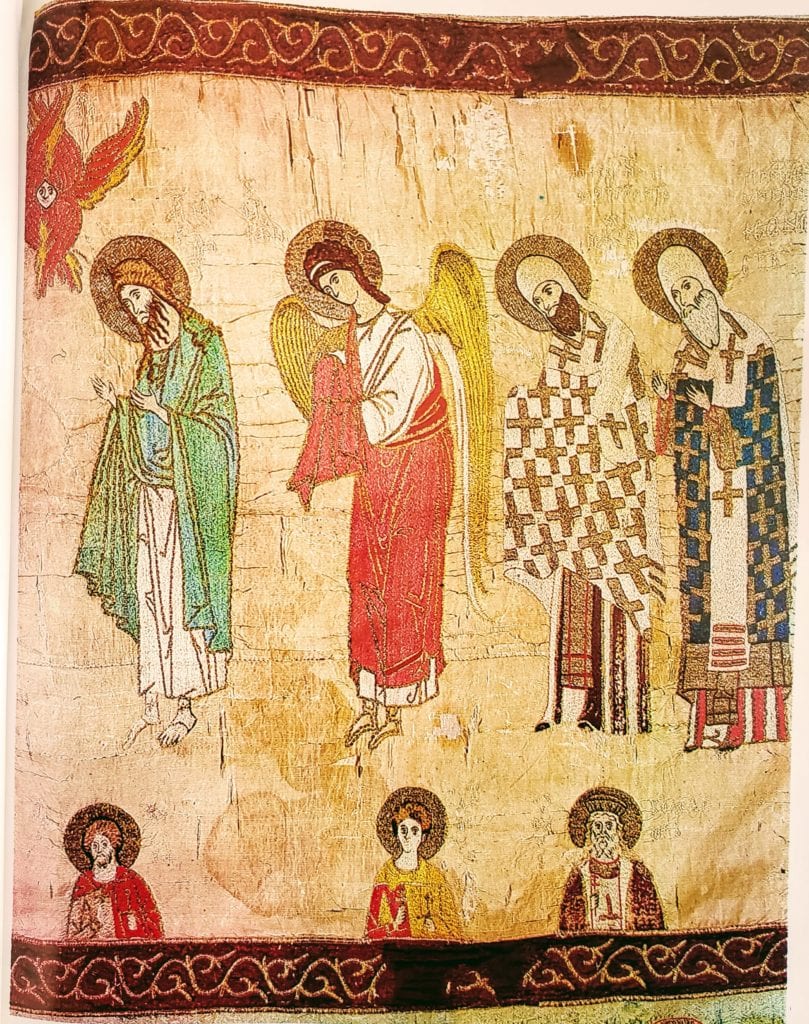

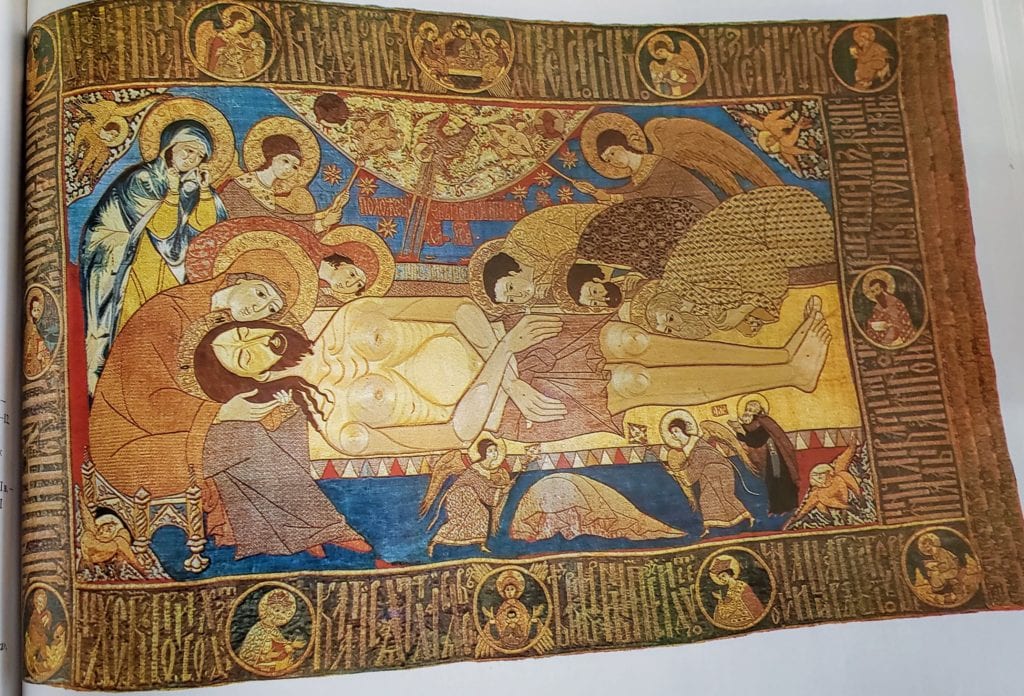

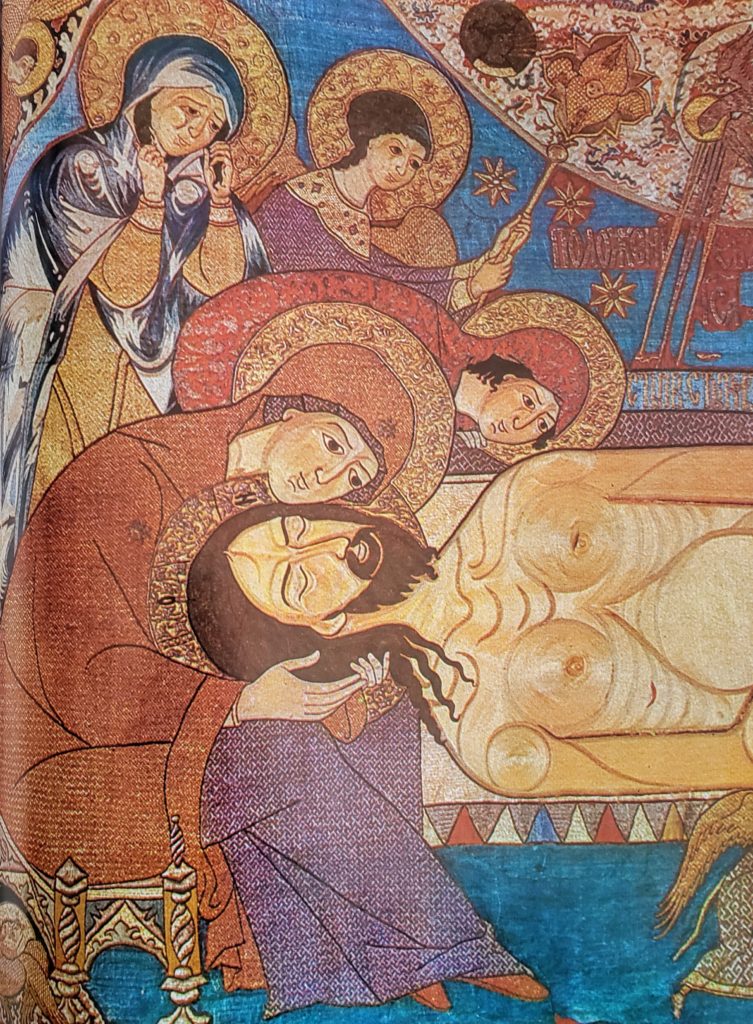

The so-called “Blue” epitaphios from the Trinity-Sergiev Lavra [Illustration 2] belongs to the same style of “goldwork embroidery.” Based on the paleography of the inscription, which contains 14th century elements, M.V. Schepkina dates this item to the very beginning of the 15th century.[31]This attribution was made in 1949 by request of the staff of the Zagorsk museum. This allows us to refer to this item as the earliest of the Russian epitaphia that have survived to modern times. Its composition depicts one of the earliest forms of the “Lamentation of Christ,” which appears to have been adopted directly from Byzantium. We also find the fountain motif, completely covered in stars and crosses inside circles, in earlier Byzantine examples.[32]For example, in an epitaphios from the time of Andronicus II Palaeologus (Byzantine emperor 1282-1328) from the Church of St. Kliment in Okhrid. See: Miljukov, P.N. «Khristianskie drevnosti zapadnoj Makedonii.» Izvestija Russkogo Arkheologicheskogo instituta v Konstantinopole, Vol 1, Issue 1. Sofia. pp 93-94, illus. 30.

Several examples of 15th century embroidery are similar to the “Blue” epitaphios in composition, general style and technological methods. These include the so-called “Euphemius” epitaphios donated in 1456, according to its inscription, by the Grand Prince Vasilij Vasil’evich to Archbishop Euphemius of Novgorod’s St. Sophia[33]Now located in the Novgorod Museum [2130]. See: Svirin, A.N., p. 39, and also two epitaphia in the Russian Museum.[34]One of these epitaphia was received from the Kirillo-Belozersk Monastery, now in the Russian Museum [281]; the other from the Arkhangelsk Medieval Repository, also now in the Russian Museum [280].

Among these works, the “Blue” epitaphios stands out for its emotional mood, particular to works of the 14th century. This feeling is created primarily by the asymmetry of its design, the center of which is drawn to the left, toward Christ’s head. The tension is also created by the fountain replete with stars, the dynamic poses of the angels which seem to gravitate in unison toward Christ, the restless silhouette of their hair, and His anguished face with its furrowed brow. The slender, narrow-shouldered and strongly elongated proportions of the figures stand out clearly against the blue background. The monotone of the gold embroidery is broken only by the red stitches which mark the contours and folds of the clothing and which underline the silhouette-like nature of the design.

The “Blue” epitaphios and similar works, and by analogy the the goldworked cuffs of Varlaam of Khutyn, are generally considered to be Novgorodian.[35]V.N. Lazarev. Iskusstvo Novgoroda. Moscow-Leningrad, 1947, p. 130; A.N. Svirin, pp. 34-36. The author of this work also has determined these to be Novgorodian. See: N.A. Majasova. «Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo.» Troitse-Sergieva Lavra. Khudozhestvennye pamjatniki. Moscow, 1968, pp. 117-118. But, evidence from the Chronicles and from extant works of goldwork embroidery from various Russian oblasts require us to reconsider this attribution. The lack of Novgorodisms in the inscription on the items listed above, a chronicle which mentions the donation of the “Euphemius” epitaphios by the princes of Moscow, the refinement of the design, the perfection of technique in the goldwork embroidery, and the opulence of the very material lead us to the opinion that the “Blue” epitaphios, just like the “Euphemius” epitaphios, originated from the workshop of the Grand Prince of Moscow. This theory is confirmed by a recently discovered epigonation from 1439, attributed to Princess Ul’janija, daughter-in-law of Vladimir the Bold.[36]cf. N.A. Majasova. «Pamjatniki moskovskogo zolotnogo shit’ja XV veka.» Drevnerusskoe iskusstvo. Khudozhestvennaja kul’tura Mosckvy i prilezhaschikh k nej knjazhestv XIV-XVI vv. Moscow, 1970, pp. 488-493.

Not as highly valued as gold embroidery, and more susceptible to destruction, items embroidered in silk have survived in lesser quantities. The earliest of these, dated to the end of the 14th century, attests to a great blossoming of silk embroidery at that time, which appears to have existed previously alongside goldwork embroidery, and which became widespread in the 15th century.

If goldwork excels in the silhouette-like style of its design and the flatness and monotonality of its rendering, embroidery with multicolored silks allowed the depiction of depth and to display subtle nuances of color transition, and to draw attention to what was most important. This embroidery is, to a larger degree than goldwork, tied to icon-painting and fresco, and it is not without reason that the French researcher G. Mille referred to it as “needle painting.”

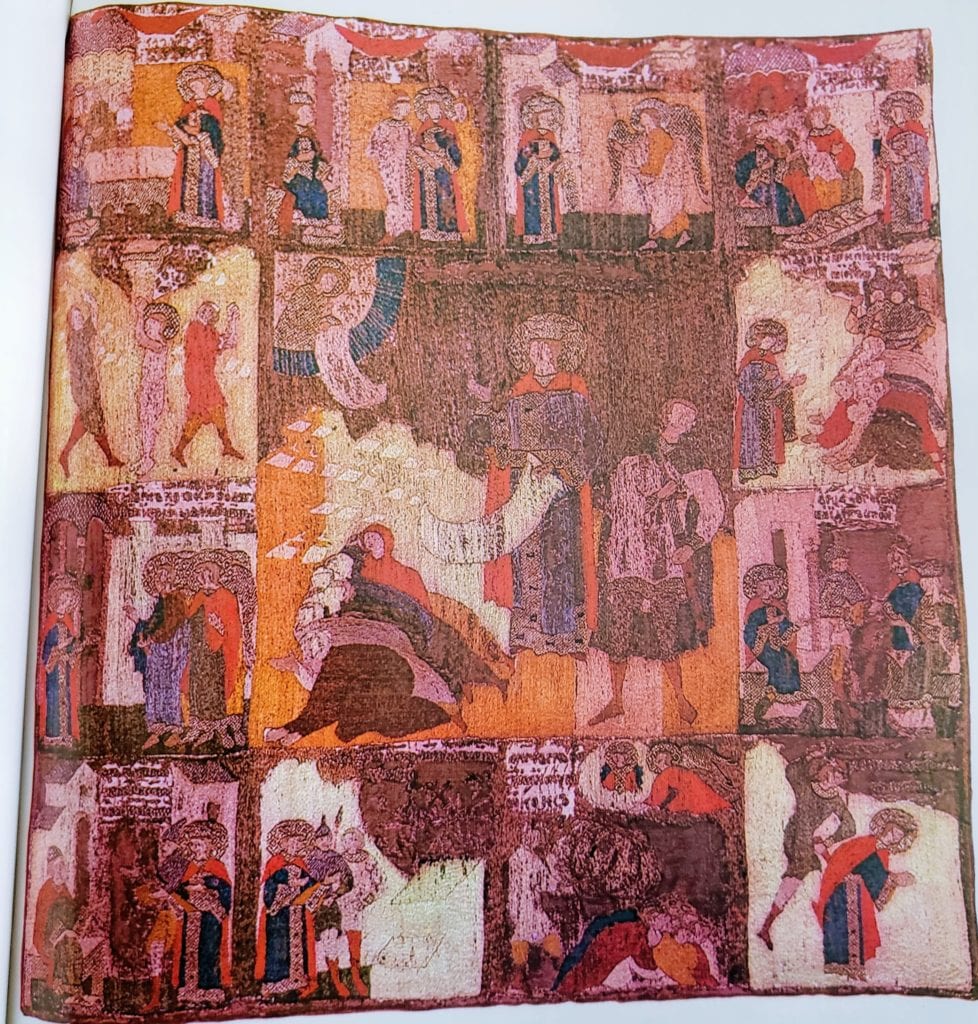

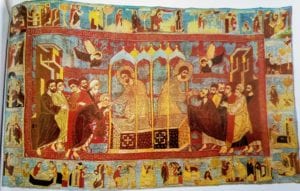

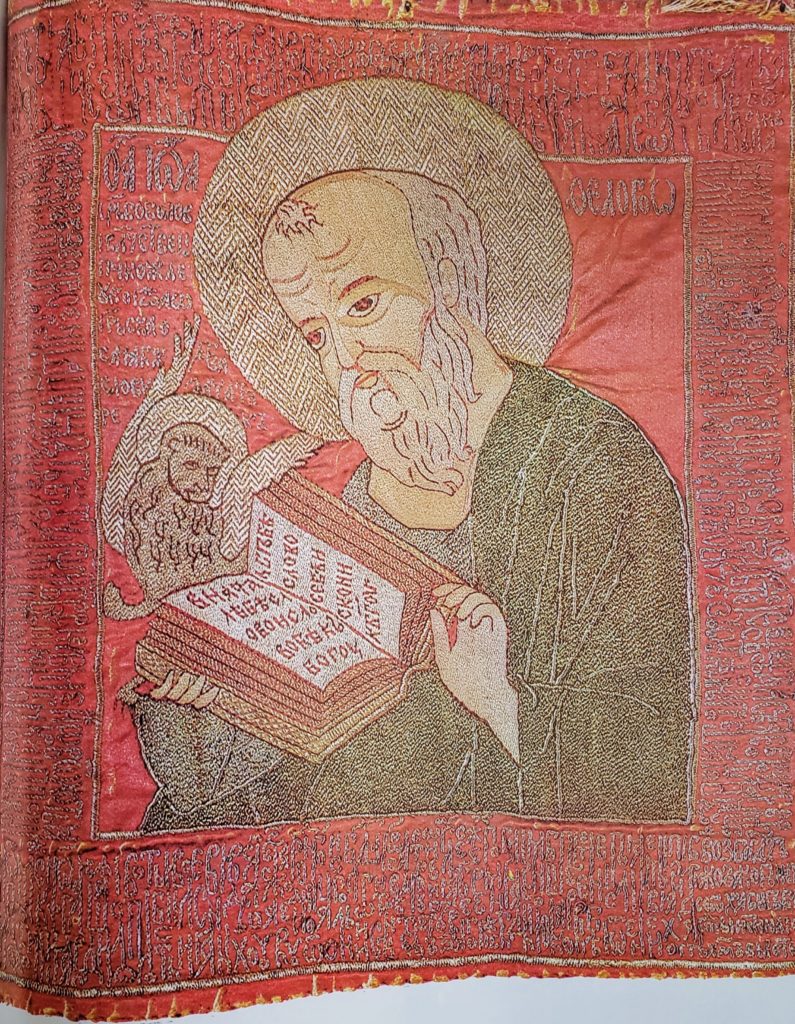

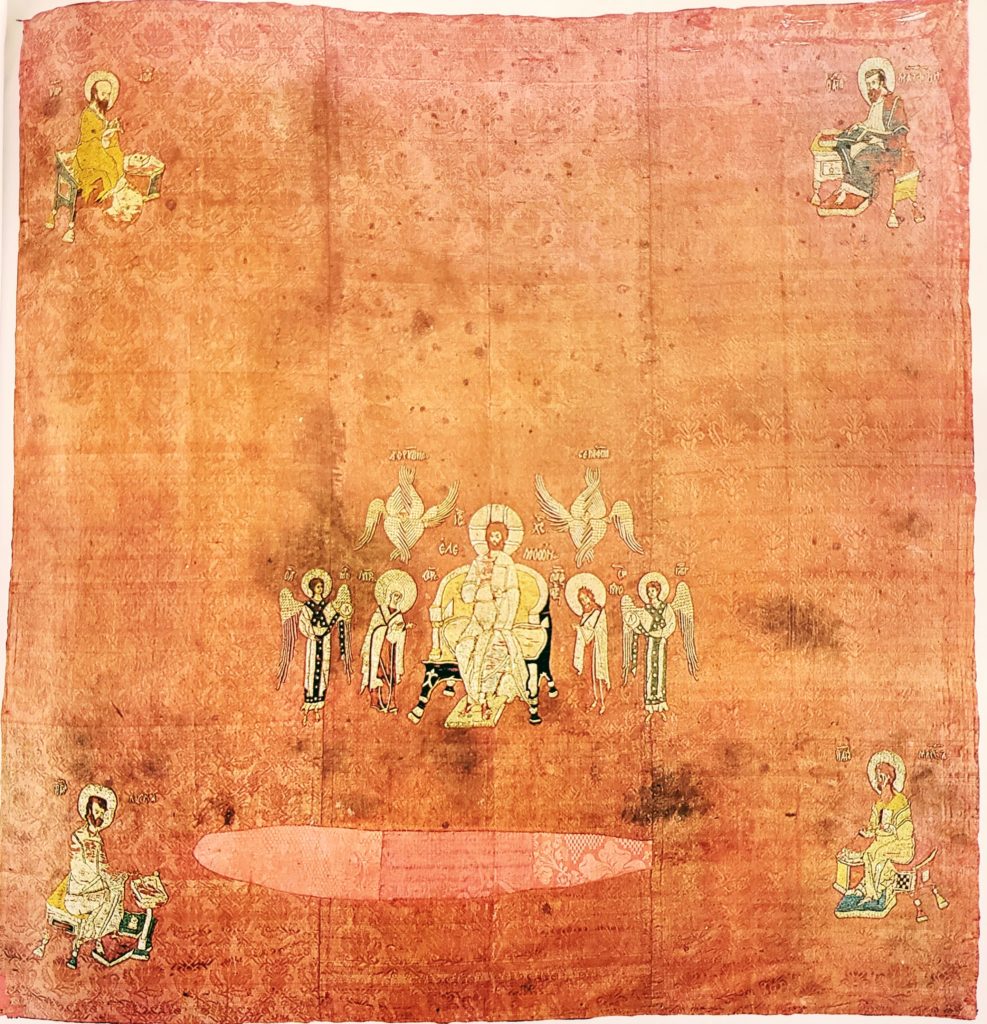

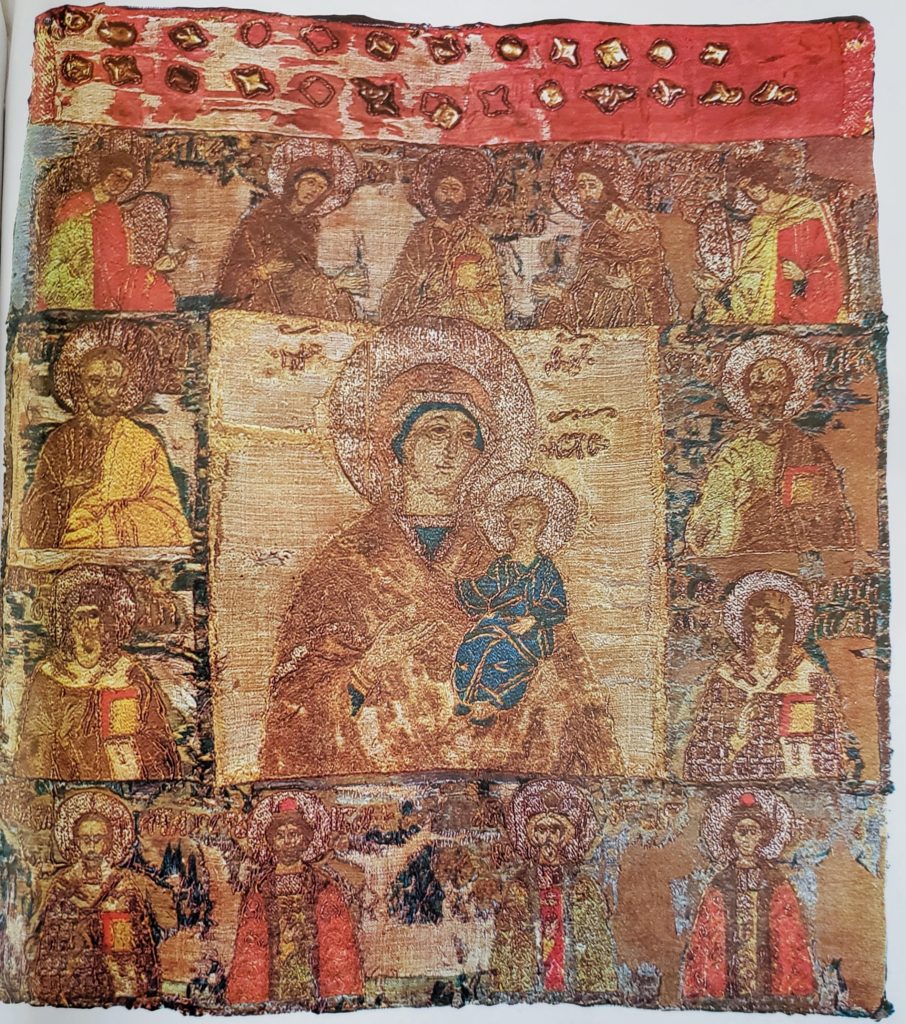

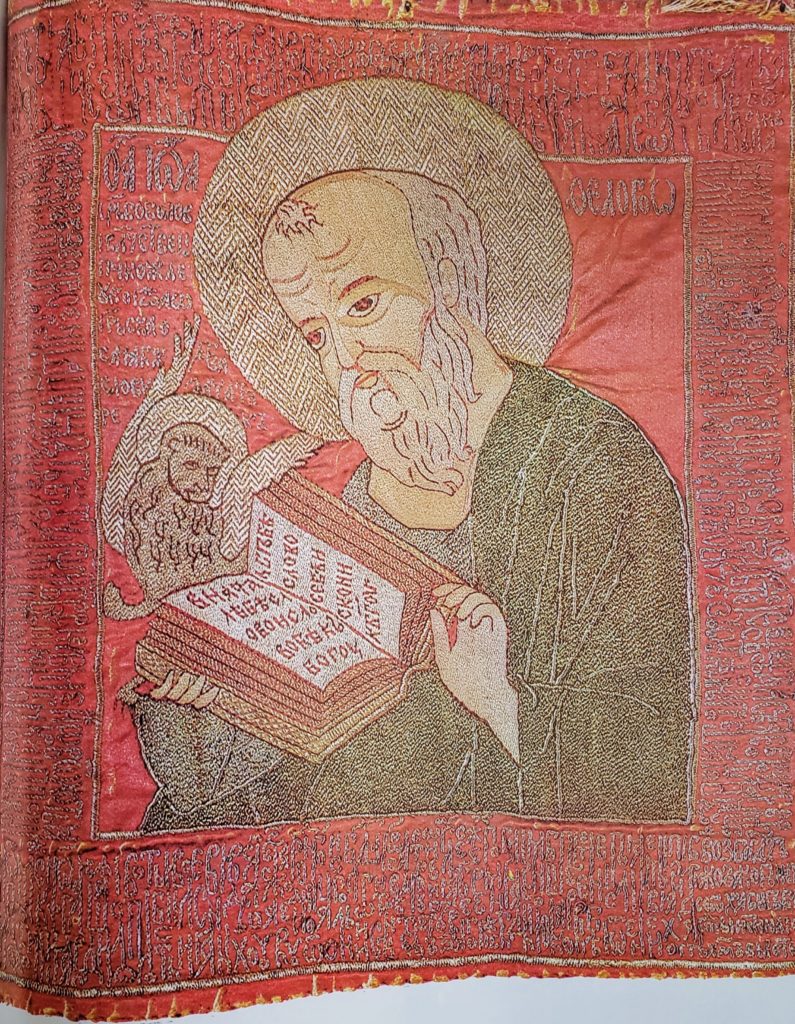

Such works include the embroidered depiction of the All-Merciful Savior with the Forthcoming from the late 14th century [Illustrations 3, 4].[37]This item has been incorrectly called “The Supreme One on His Throne” (cf. V.N. Lazarev, p. 129; A.N. Svirin, p. 27). These same authors also attribute it to 14th century Novgorodian art. On the original ground, which has not survived, there were likely donor and liturgical inscriptions. Today, the work appears as a large square veil. The images of the Savior and those surrounding him are placed not in the center, but rather a little lower, while the evangelists are embroidered writing in the four distant corners. This placement of the figures and the general size of the veil lead us to think that the served as the front part of an altar cloth.[38]Cf. a throne cover, similar in composition, donated by the Godunovs to the Trinity-Sergiev monastery (illus. 53).

The Savior, in light blue and silver robes, solemnly sits on a semi-circular throne. His figure, which is sharply elongated in proportions, is several times larger than those of his followers. The divinity of the Savior is underlined by the seraphim and cherubim which shade him with their wings. The Holy Mother and John the Baptist’s heads are inclined toward Him in prayer, and their hands are outstretched. The row of followers is rounded out by fine, slender archangels in Roman-style robes [Illustration 4].

The color scheme is dominated by light blue, dark blue and yellow silk in combination with silver and gold. In the proportions of the figures, the form of the archangels’ wings, and in the unusually curved legs of the Savior’s throne and of the evangelists’ desks, and in the ratio of colors, we can feel the sophisticated taste and familiarity the artist had with the greatest works of Christian art.[39]A.N. Svirin finds an analogy to the archangels in this work in mosaics of the latter half of the 13th century in the Church of San Gregorio in Messina (cf. A.N. Svirin, p. 27). The inscriptions in Cyrillic letters convey with errors the Greek names: “IS XS Elemoön” (Jesus Christ the Savior), “prdmro” (Prodromos-the Forerunner).[40]A Byzantine cameo from the 11th century with a bust depiction of Christ with the Evangelists is preserved in the Hermitage, with a Greek inscription: “IC XC OELENMON”; on the reverse, also in Greek: “Christ Our Lord, he who trusts in you shall not be deceived” (cf. A.V. Bank, Vizantijskoe iskusstvo v sobranijakh Sovetskogo Sojuza. Moscow-Leningrad, 1966, no. 167-168). The title “Savior” rather than “the All-Mighty”, is suitable to the composition, which is presented as a small Deësis rank, in which “Christ appears not in the form of an apocalyptic Ruler of the World, that is, as a terrible judge, but instead as a kind Savior, called to save humanity”[41]V.N. Lazarev, p. 75. Churches were also dedicated in Rus’ to the All-Merciful Savior. For example, a chapel is dedicated to him in the Transfiguration Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin. The chronicles mention it in relation to the burial there in 1396 of Stefan of Perm. PSRL, vol. XI. Moscow, 1965, p. 164. The Greek-sounding nature of the inscription and the composition, which is solemn and full of refined grace, suggest there was some similar Byzantine original. It is quite possible that this “All-Merciful Savior,” having no analogy in Novgorodian art and yet at the same time responding to its Grand Prince surroundings, was created in Moscow in the second half of the 14th century and was given to Novgorod as a royal gift.

It is worth noting that in this item, the Deësis composition is shown full-length; today, as in medieval Russian painting, especially applied art and ecclesiastic embroidery, half-length figures are seen since the early 15th century.[42]For example, a 12th century tiara from Kiev (cf. Istorija kul’tury Drevnej Rusi, Vol. 2. Moscow-Leningrad, 1951, p. 418), or the 12th century cuffs of Varlaam of Khutyn (cf. A.N. Svirin, p. 25).

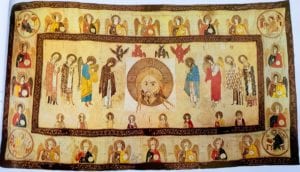

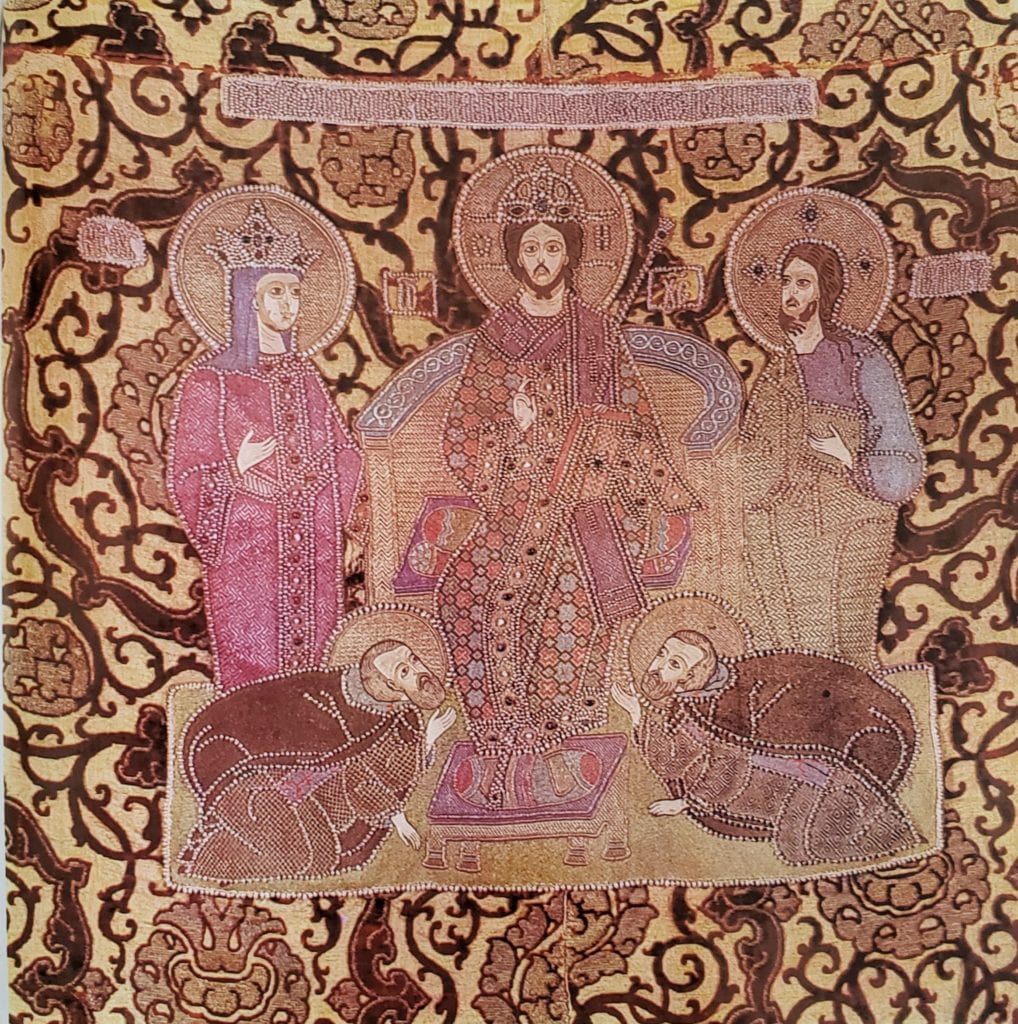

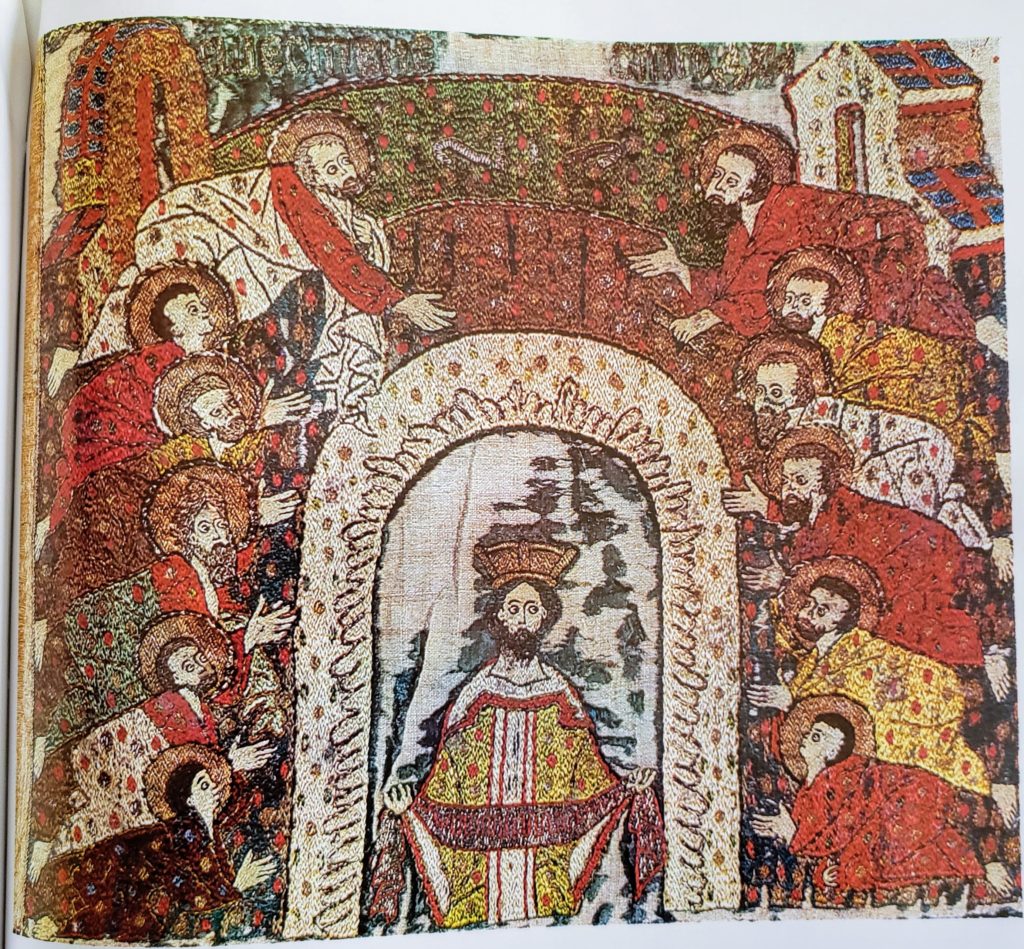

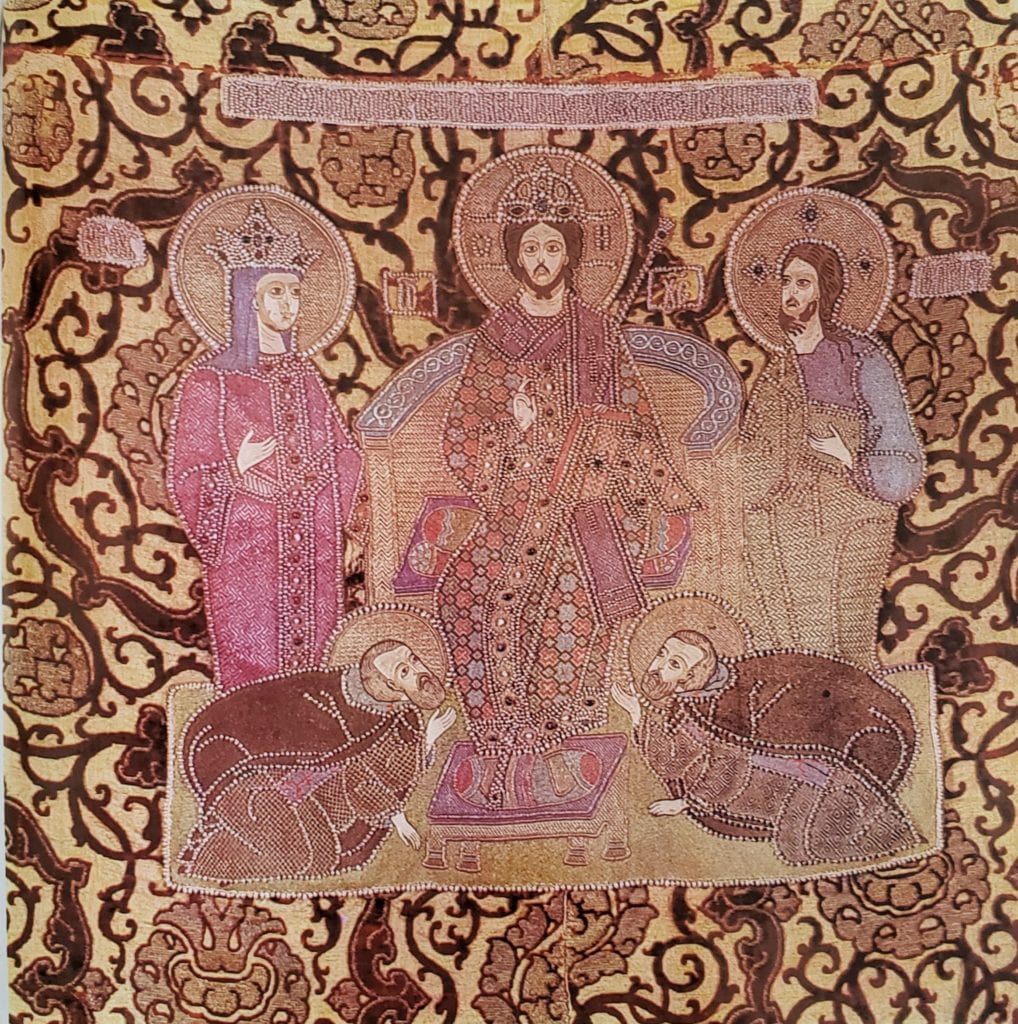

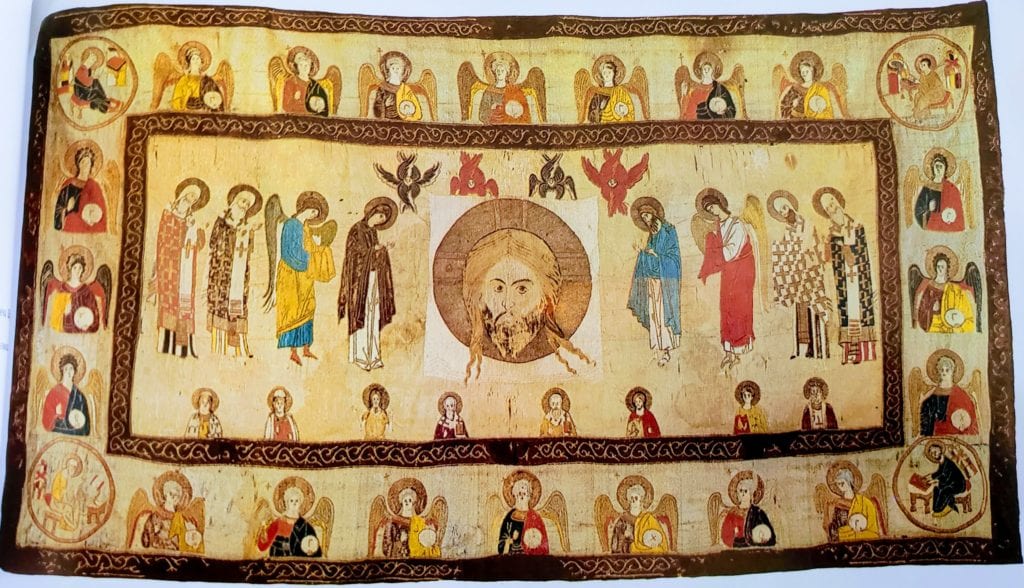

A Deësis composition with eight figures standing before the image of the Savior Not Made By Hands[43]jeb: Also known as the Image of Edessa, or Mandylion. was also embroidered in the late 14th century on an Aër which has a certain stylistic similarity to the “All-Merciful Savior.”[44]It is worth drawing our attention to the proportions of the figures of those standing before Christ, the elongated form of several of their heads, and on other details. The inscription on the Aër attests to its creation in 1389 by Grand Princess Marija Semyonovaja [Illustrations 5, 6]. This is the earliest of the dated works of Muscovite embroidery to have survived to our time. The donor of this Aër was the daughter of the Prince of Tver Akeksandr Mikhajlovich and the third wife of Grand Prince Simeon the Proud. Having been widowed at a young age, the Princess died of old age[45]Marija was married in 1346; Simeon died in 1353 during a plague epidemic. in 1399 having “taken the black” and the name Fetinija, and was buried in the Kremlin in Spassky Monastery, the main cathedral of which was painted and decorated at the direction of Simeon’s first wife. It is possible that Marija also donated her veil with the image of the Savior to this church. The inscription recalls her wordly name, based on which we can determine that the Aër was embroidered before she took orders and was created in the Grand Prince’s workshop.

The creator of this veil, the daughter of a prince who came out against the violence of the Khan’s legate and who was killed for it by the Horde, managed to express in her work the thoughts and senses felt by the people who had just survived the Battle of Kulikovo and the siege of Moscow by Tokhtamysh. The stern face of the Savior is reminiscent of the battle flags which often portrayed his likeness during that time.[46]The researcher of medieval Russian flags, L. Jakovlev, notes that the first example of this depiction of the Savior’s face on banners, and even the first use of the word znamen’ (rather than the more ancient word stjag) for “flag,” is found in a description of the preparations for the Battle of Kulikovo in “The Doings and Tales of the Massacre of Dmitrij Donskoj”: “… And the Grand Prince, arrayed with his Polish soldiers … went out to the high place, and saw the image of Christ depicted on the Christian banners, shining like the sun.” (Drevnosti possijskogo gosudarstva. Addendum to the third edition. Moscow, 1865, p. 17) Among those who pray to Him are the Muscovite metropolitans and the holy Russian warrior-princes Boris and Gleb. Among the half-length figures in the central section in the right corner, next to the images of Dmitrius of Thessaloniki and Prince Vladimir, are the labeled holy heroes of the Battle of Kulikovo, Dmitrij Donskoj and Vladimir Andreevich the Brave. Here too is embroidered the martyr Nicetus the Goth, the famous vanquisher of demons, which the Russians associated with the infidel and evil enslaving Tatars; and another champion against demons and heretics, the recognized defender of the Russian clans from foreign invaders, St. Nicholas.[47]Aside from these depictions, we also see embroidered here: the creator of the liturgy Gregory the Theologian, and, in an Orans pose with his hands raised in prayer, St. Alexius of Rome, whose Life was associated with the cult of the Savior Not Made By Hands. Contrary to the statement by the first researcher of this Aër, V. Trutovskij, about the image of the Savior being a supposedly later work (Khudozhestvennye sokrovischa Rossii. Vol 2. St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 125), detailed surveys have shown that the Savior was embroidered contemporaneously to the rest of the veil. Along the outer edge, there are the solemn figures of triumphant Heavenly warriors – angels and archangels – as protectors of the people in their battle with the forces of evil. Between these figures, fragments of an inscription are preserved, speaking of “glory in Heaven and on Earth.” This entire work, with its solemn composition, symbolic images and inscriptions, and festive color scheme, is permeated by the belief in the victory of light over the dark forces of evil.

In addition, this notable monument to the heroic epoch of the battle against the Tatar-Mongol yoke and the creation of Russian nationhood attests to the rich traditions which up to this time were held by the art of medieval Russian embroidery. The embroideresses were able to convey with great mastery the subtle, expressive face of the Savior, the light, graceful figures of those standing before Him, and the picturesque poses of the Evangelists. The strong, rhythmic form of the composition and its restraint are emphasized by the dark-violet stripes with their thin golden patterns and the precise alternating colors of the angels’ clothing around the edge. The color scheme around the edge is more saturated than in the center. Here, cinnabar and cornflower alternate with yellow and purplish-brown, rather than the pale yellow and white images in the center. These create a certain artistic expressiveness. This major scale of color underlines the work’s epic, solemn content.

The rise of national identity following the Battle of Kulikovo had a huge impact on the creative forces of the Russian folk. Medieval russian embroidery, as well as icon-painting, increasingly begins to deviate from the traditions of Byzantine art.

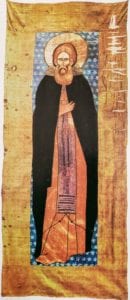

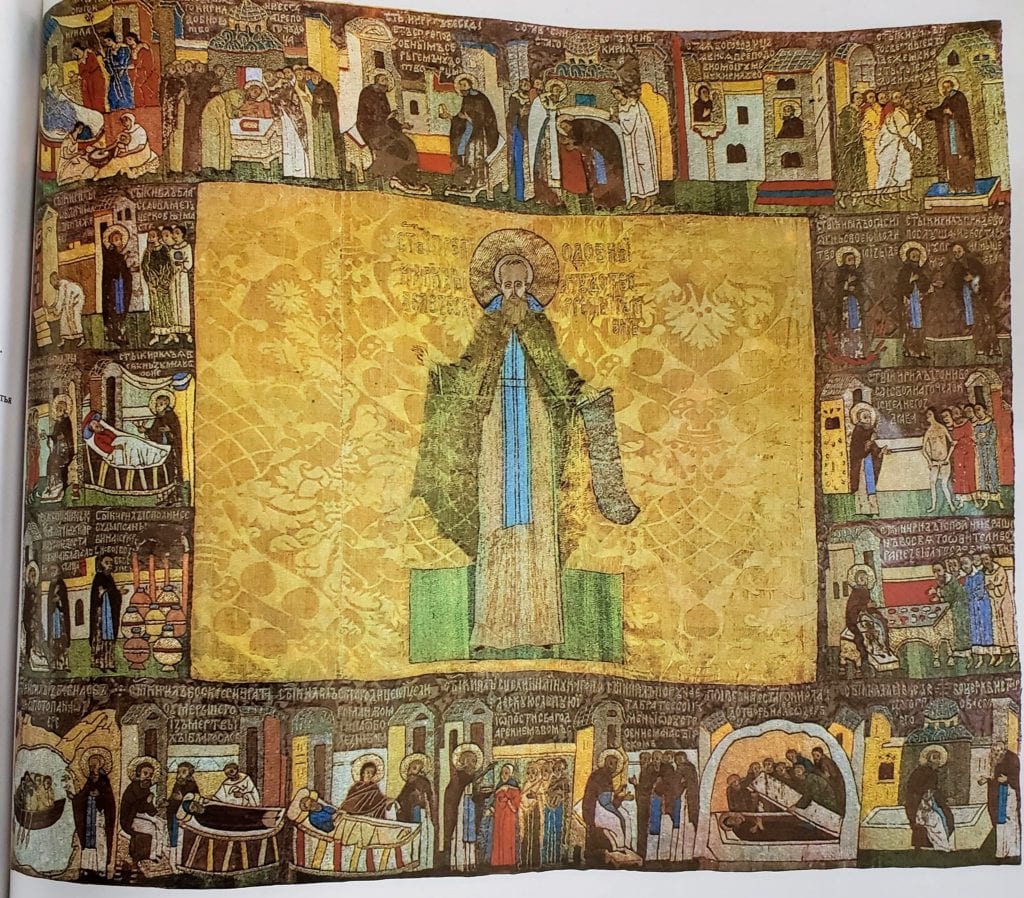

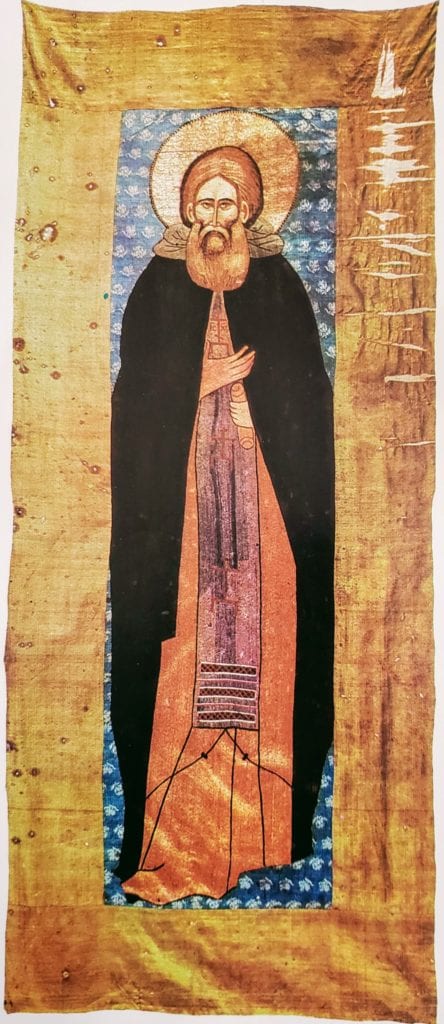

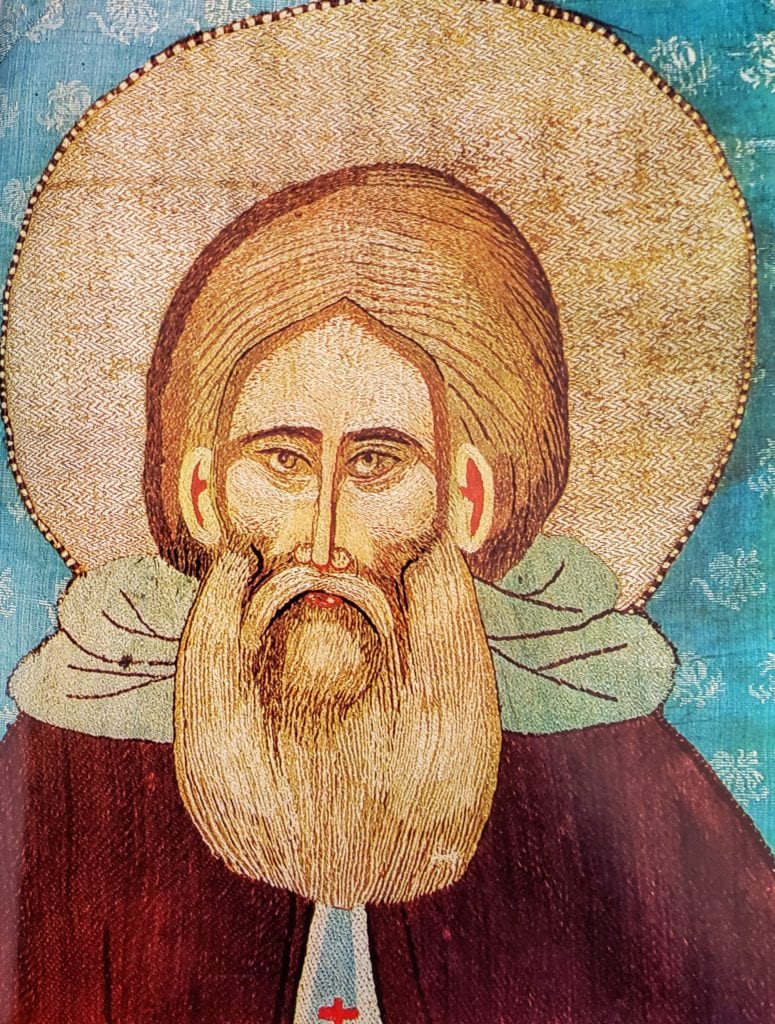

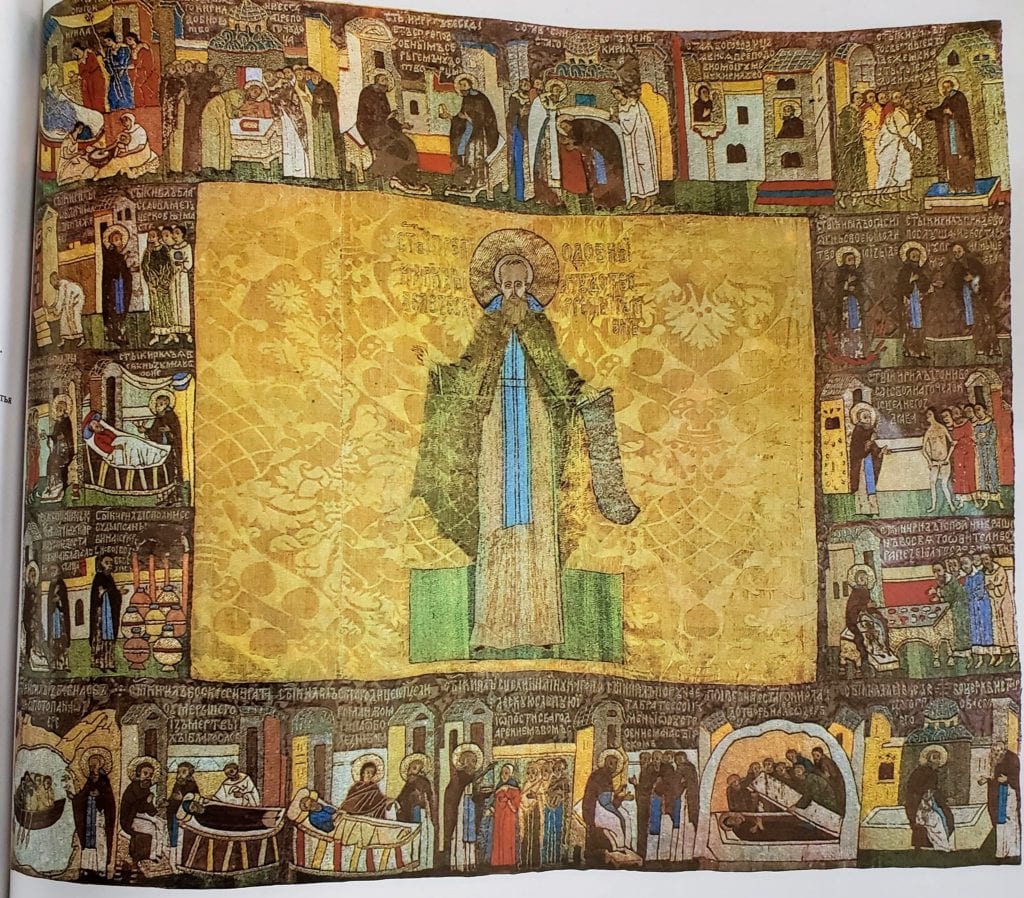

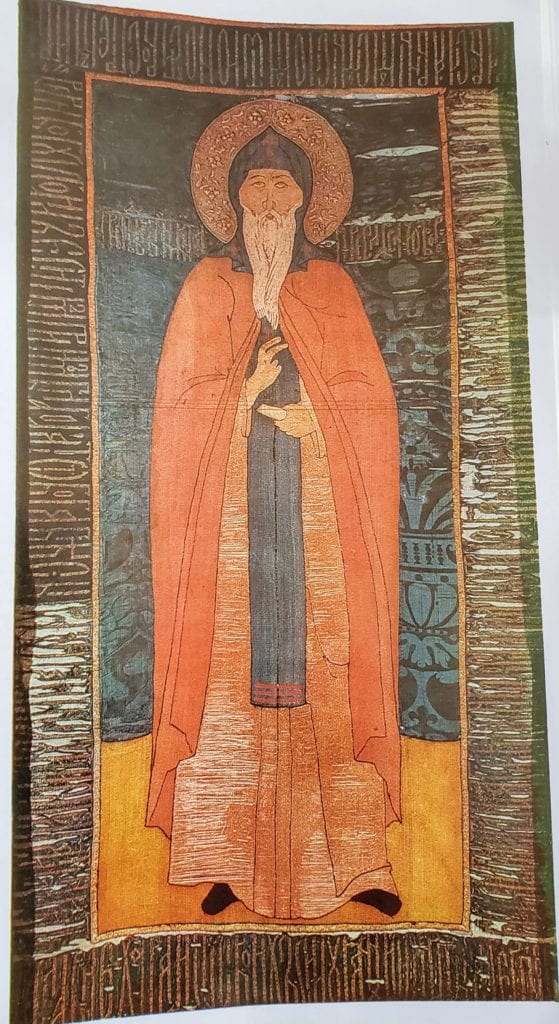

A veil with the image of Sergius of Radonezh [Illustrations 7 and 8], typically dated to 1422-1424, that is, immediately after the saint’s canonization, holds a special place among the monuments of this period. Amongst burial veils, most of which are stored in various museums in our country, this veil stands out for its individual interpretation of form and for its technique of embroidery, which was unusual for this time period.

Sergius’s large head is somewhat assymetrical, as if slightly turned to the left, while the face points forward. The hair, forming a sharp angle on the forehead, is parted, divided into strands which cross over his head. The face has high cheekbones, with a large forehead and sunken cheeks. Beneath his thick, almost straight eyebrows, are his close-set, narrowed eyes. The smart, insightful gaze of these peculiar eyes produces an indelible impression. The undeniable individuality of the interpretation of the face suggests the direct perception by the artist, a certain portrait-ness in form. It is evident that Sergius’s face had such characteristic, unique features that it was well-remembered by those who saw it. It is possible to suppose that he was also seen by the artist, who conveyed his likeness with rare artistic skill.[48]The 30 years separating the Sergius’s death (1392) and the creation of this veil do not preclude this possibility. Applying the split stitch which was typical for Russian embroidery, the artisan sculpted the form like a sculptor using large stitches, arranging them along the direction of the muscles, introducing darker threads in shaded areas, a technique which became more widespread in Russian embroidery later, in the 16th century. The artisan also created here singular highlights; on the forehead and cheeks, she placed stitches of red thread, and drew with red thread the lines of the nose and lips, and filled in the folds of the ears. Just as picturesquely, she depicted the beard and hair of the saint using silks of various tones – flesh-colored, grey and brown. Despite the techniques of silk embroidery which were rare for this time period, this veil should be attributed to the first quarter of the 15th century, when there were still those alive who would have remembered Sergius.

This is further supported by our very understanding of the image, and our attention to the inner essence of the subject, characteristic of the time of Andrej Rublev, Theophanes the Greek, and their “associates.” It is necessary to dwell on methods such as the red outline of Sergius’s nose, which call to mind the faces from the Deësis in the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin. Moreover, the unique interpretation of Sergius’s head and face are very similar to the depiction of Abraham in the 1408 fresco “The Bosom of Abraham” in Vladimir’s Cathedral of the Assumption, considered to be the work of Daniil the Black.[49]I.E. Grabar’. «Andrej Rubljov.» Voprosy restavratsii. Iss. 1. Moscow, 1926, p 71, illustration on p. 35; V.N. Lazarev. Andrej Rubljov i ego shkola. Moscow, 1966, p. 103; et. al. Scholars have pointed to Daniil’s tendency toward “the expressiveness of literally portraitlike characteristics of the persons portrayed”[50]S.S. Chudrakov. «Andrej Rubljov i Daniil Chjornyj.» Sovetskaja arkheologija. 1966 (1), p. 100. From 1424-1427, the years to which we attribute the creation of this veil, Andrej Rublev and Daniil the Black, along with their school, painted the frescos and icons in the Trinity Cathedral, at the invitation of Nikon of Radonezh. This evidence allows us to suppose that perhaps it was Daniil, the oldest of the masters and artel of artists working in the monastery, who served as the lead icon-painter for this first veil in honor of Sergius’s tomb.[51]In the literature, we frequently find the idea that the lead icon painter may have been the nephew of Sergius, Fedor, the archimandrite of the Simonov monastery; or they suggest it was Archbishop Rostovskij, who according to legend painted a likeness of Sergius while the latter was still alive. No works by Fedor have survived against which we could compare this veil, and we have only descriptions from the 17th century («Skazanie o sv. ikonopistsakh» from the so-called «Klintsovskij podlinnik» – cf. F.I. Buslaev, Literatura russkikh ikonopisnykh podlinnikov, Vol II. St. Petersburg, 1910, p. 396). As a result, the aforementioned theory seems, in our opinion, much more likely. It is entirely likely that the donor of this veil was Prince Jurij Dmitrievich of Zvenigorod, Sergius’s godson, who donated the primary funds for the construction of Trinity cathedral and who lobbied in support of the saint’s canonization.[52]There is evidence that Prince Jurij’s wife embroidered the chasubles for Nikon of Radonezh and Savva of Storozhi (Archbishop Leonid. Zhizneopisanie pr. Savvy Storozhevskogo. Moscow, 1877, p. 12)

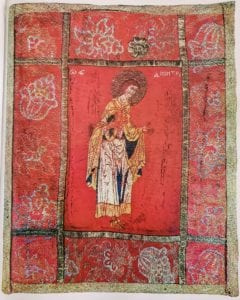

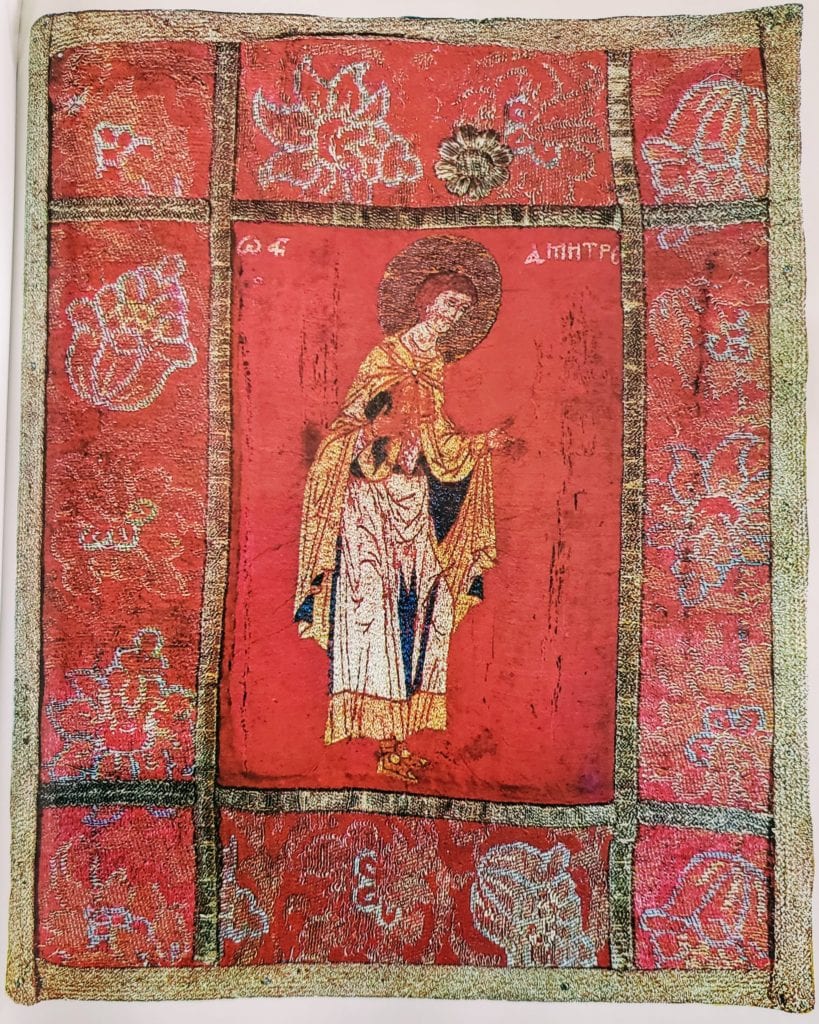

A small embroidered icon of St. Demetrius of Thessaloniki [Illustration 9] also belongs to this circle of Muscovite art, completed by artisans in the same vein. The saint is shown in 3/4 profile to the right in a pose of prayer. It would appear that this was part of a small iconostasis. Such embroidered iconostases, lighter and more convenient to transport than paintings on wood, were taken along on military campaigns and distant journeys. An embroidered iconstasis belonging to Tsar Feodor Ivanovich has survived,[53]The iconostasis is stored in the Russian Museum [314-322] (cf. E. Kutilova, «Vnov’ restavrirovannyj pamjatnik XVI v.» Soobschenija Gos. Russkogo muzeja. Iss. 1. Leningrad, 1941, p. 17; Ju.N. Dmitriev. «K istorii odnogo pamjatnika.» Soobschenija Gos. Russkogo muzeja. Iss. 4. Leningrad-Moscow, 1956, p. 5); it later became part of the “marching canvas church” of Aleksej Mikhajlovich.[54]A.I. Uspenskij. Zapisnye knigi i bumagi starinnykh dvortsovykh prikazov. Moscow, 1960, pp. 2, 15, 74-76. The icon of Demetrius of Thessaloniki is the earliest example known to us of this kind. Demetrius’s entire pose, including the slightly bowed head and upper portion of his torso, his outstretched arms, and his bent knees, create an expression of humble prayer. His form is treated very softly. His movement is graceful. The figure with its narrow shoulders seems a bit elongated in its upper half, creating a feeling of fragility and a certain refined grace. His clothing falls in soft folds, easily and loosely drawn in brown silk. The color scheme is based on a combination of whitish-flesh colored and yellow silk with blue spots, giving it a festive tone and a sense of light.

The figure’s overall silhouette, posed legs, and the arrangement of the folds of clothing recall the depiction on an icon of the same name from the Deësis row in the Trinity Cathedral in the Trinity-Sergiev Monastery.[55]cf. V.N. Lazarev. Andrej Rublev i ego shkola, illus. 178. It is entirely possible that the same artist, a close disciple of Andrej Rublev, was also the lead iconographer for this embroidered Demetrios.

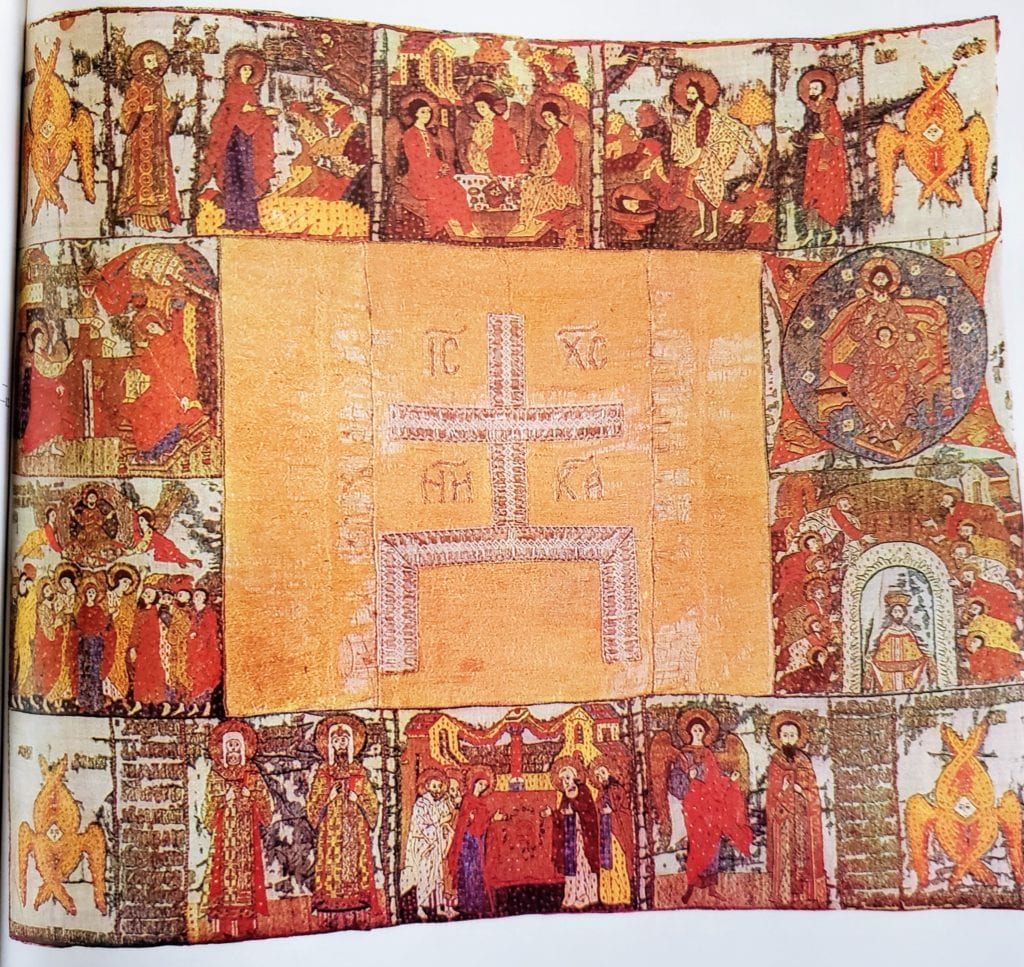

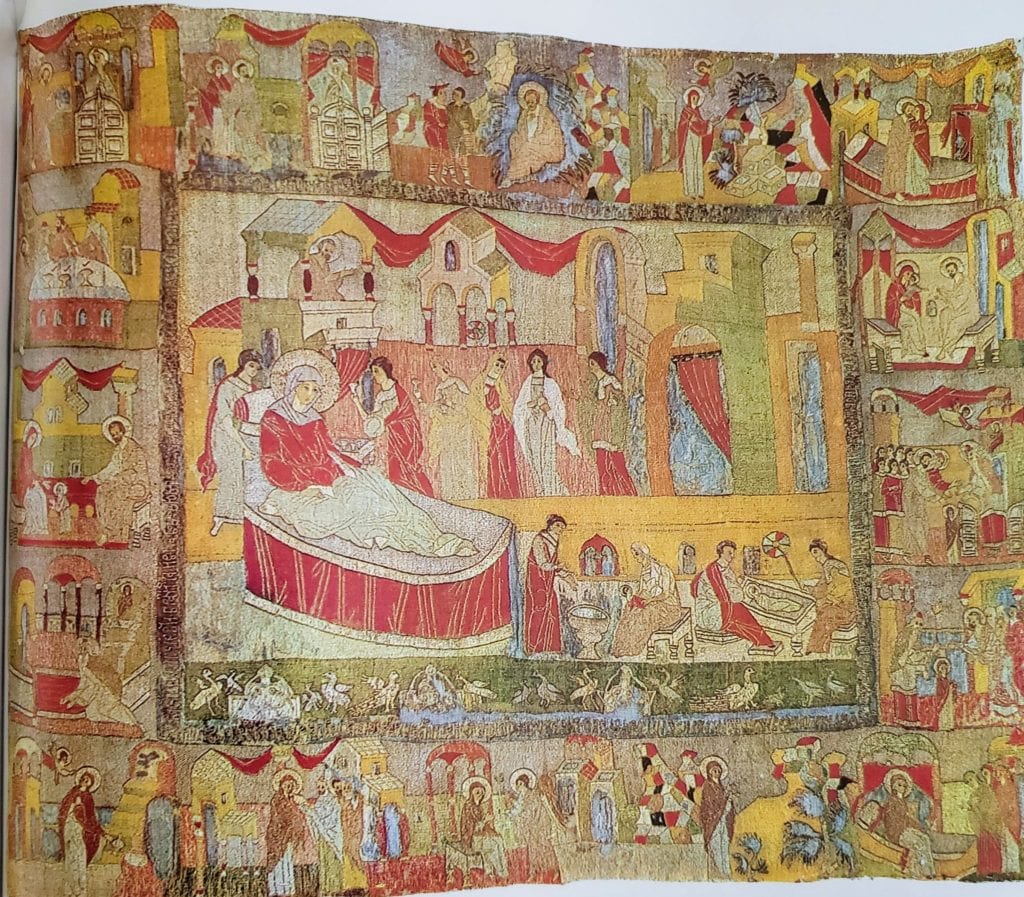

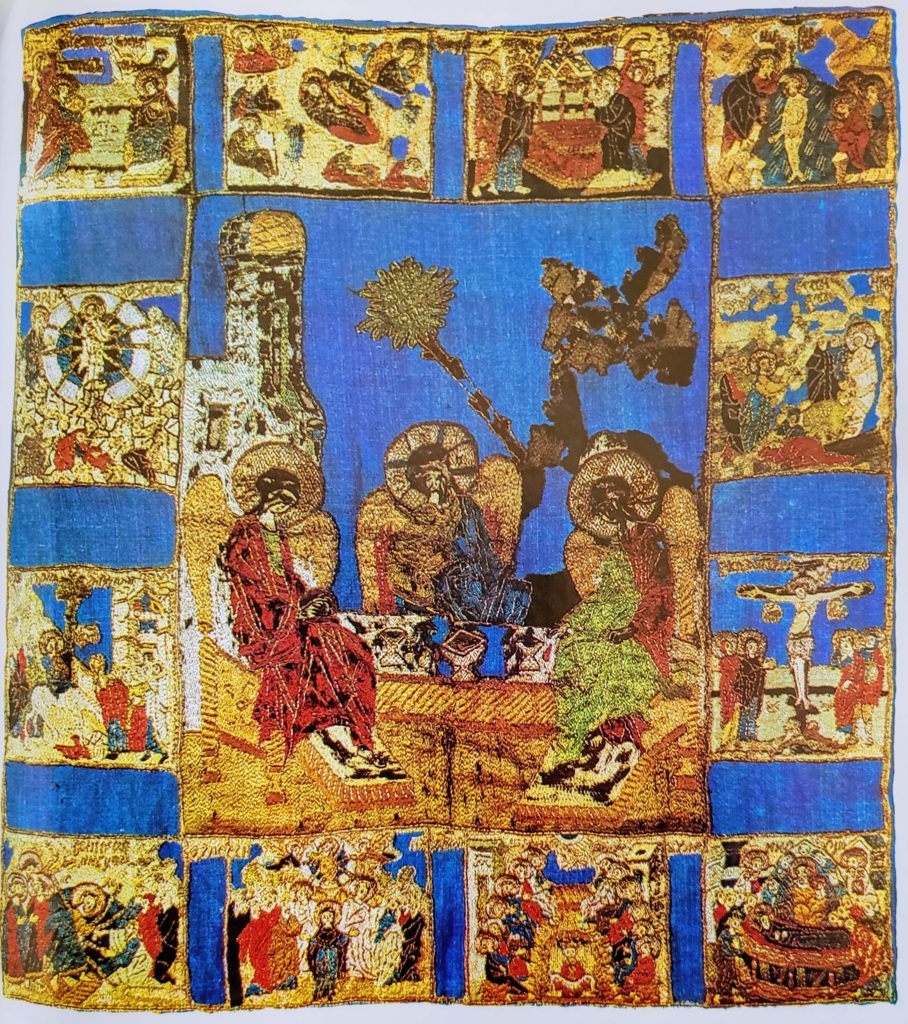

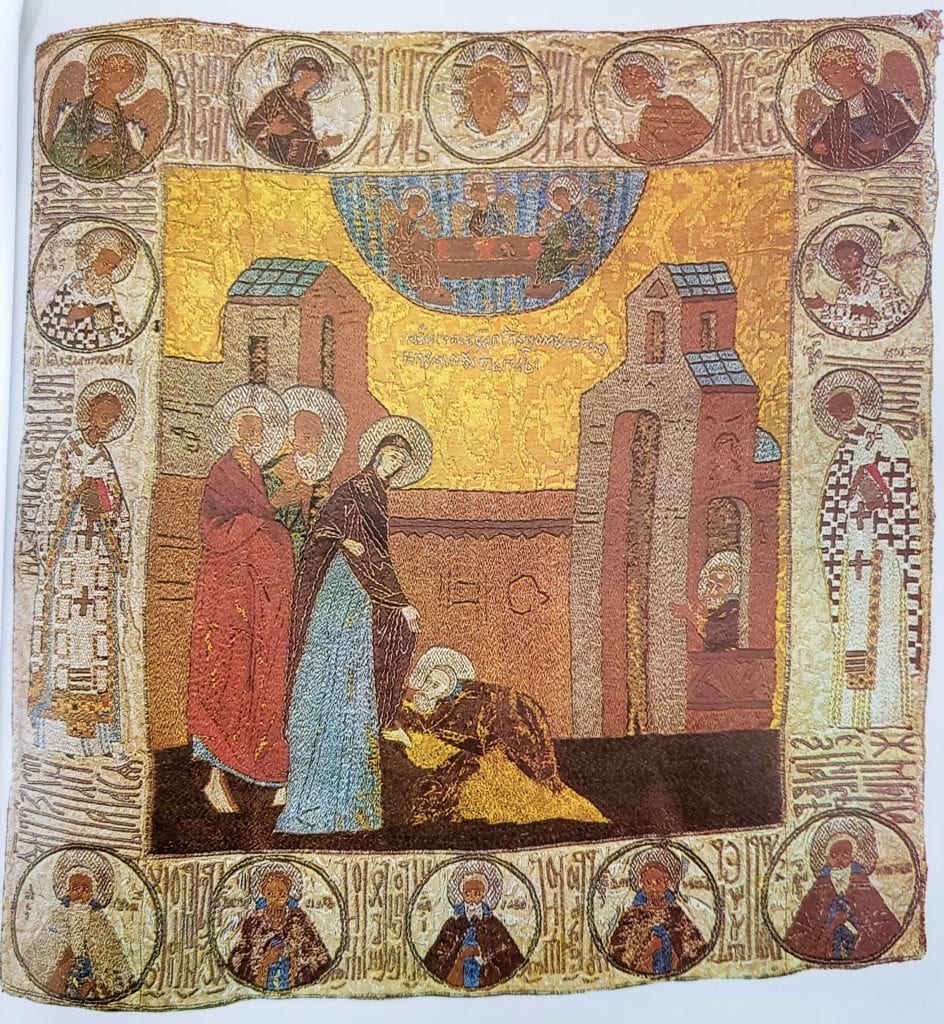

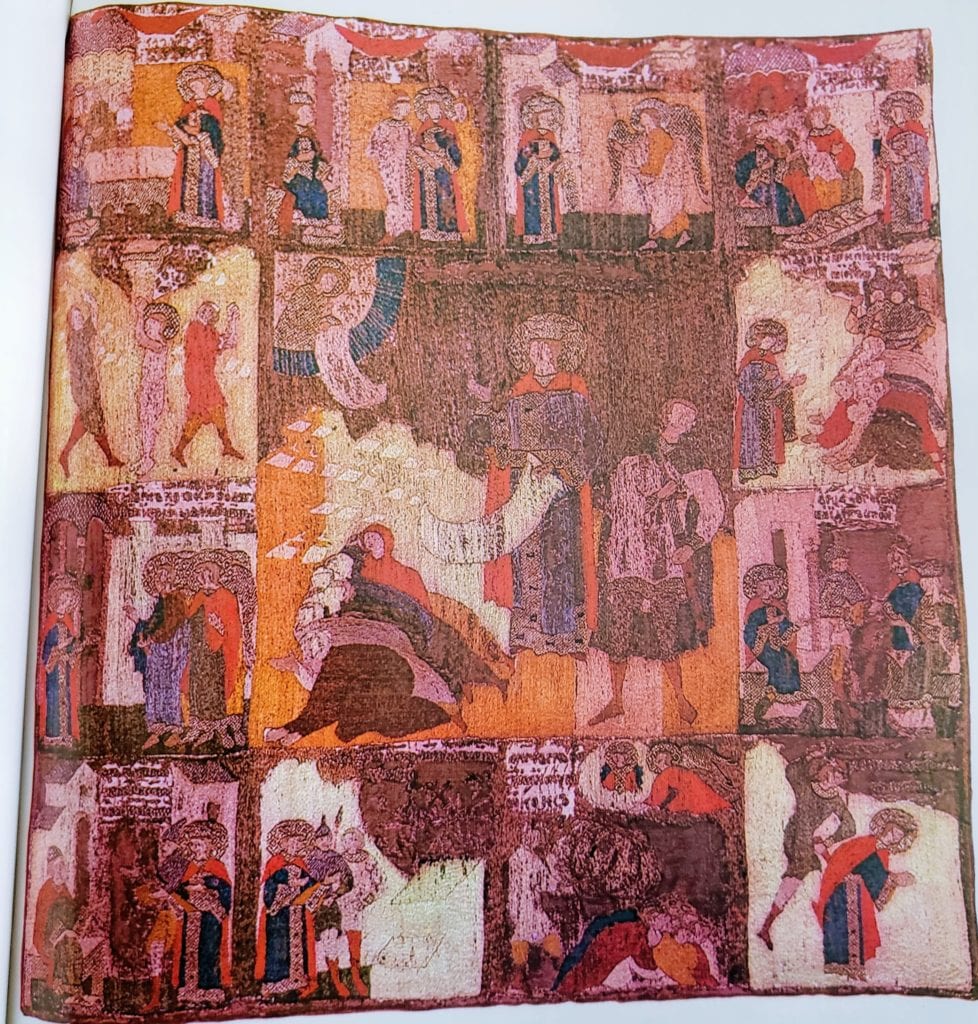

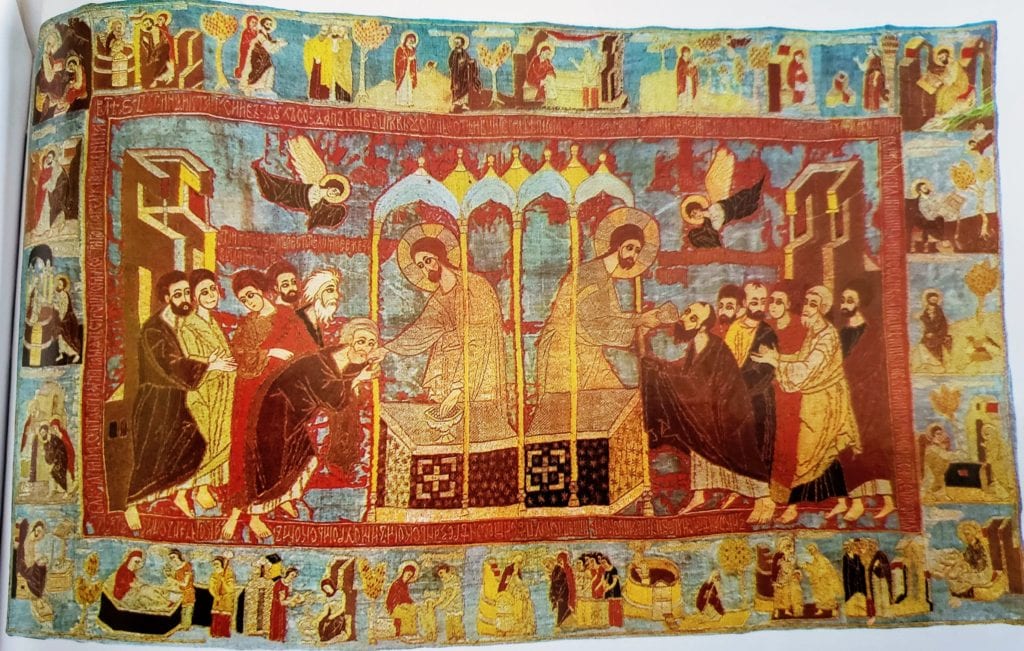

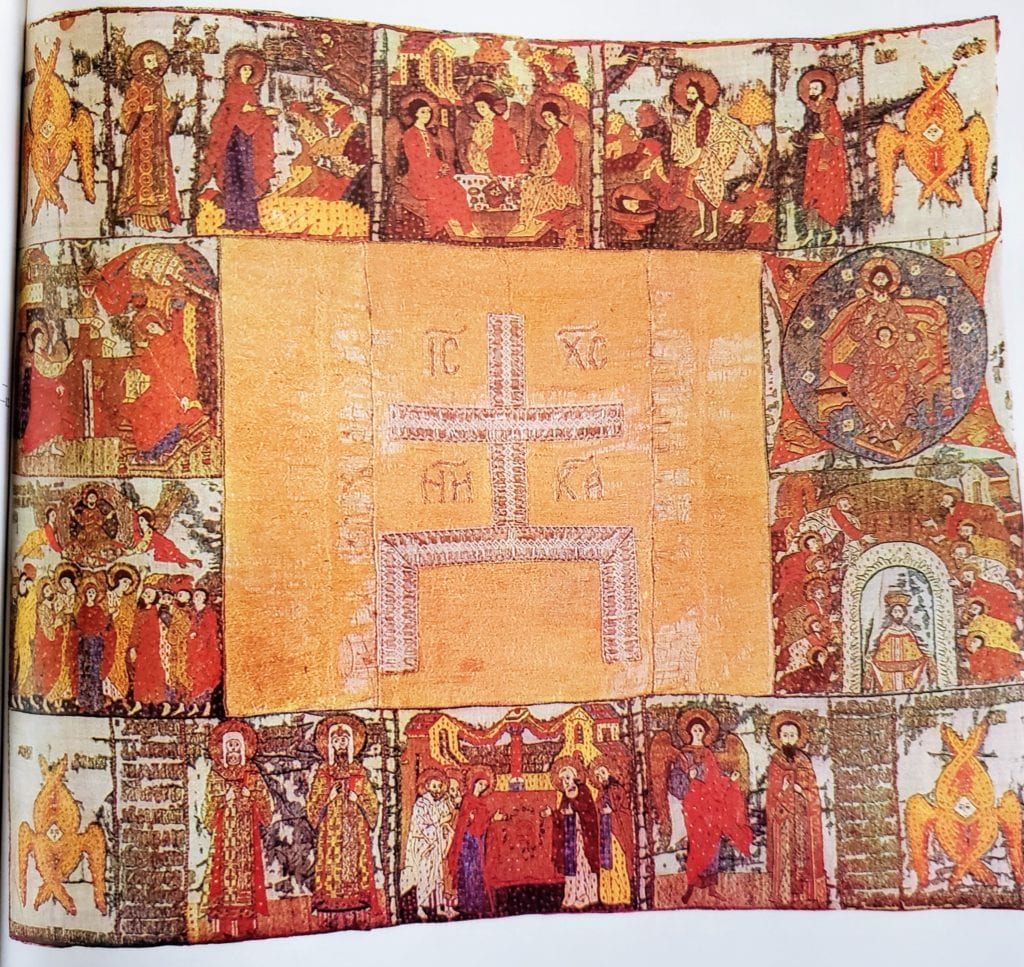

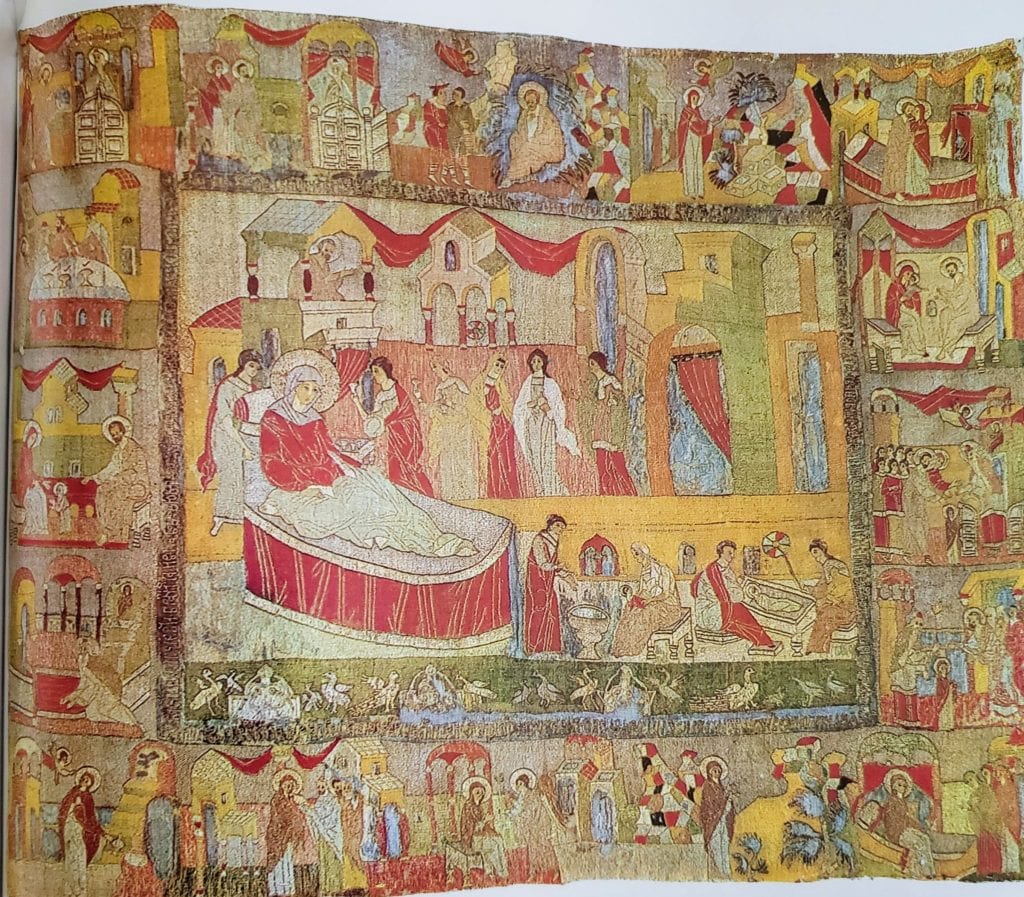

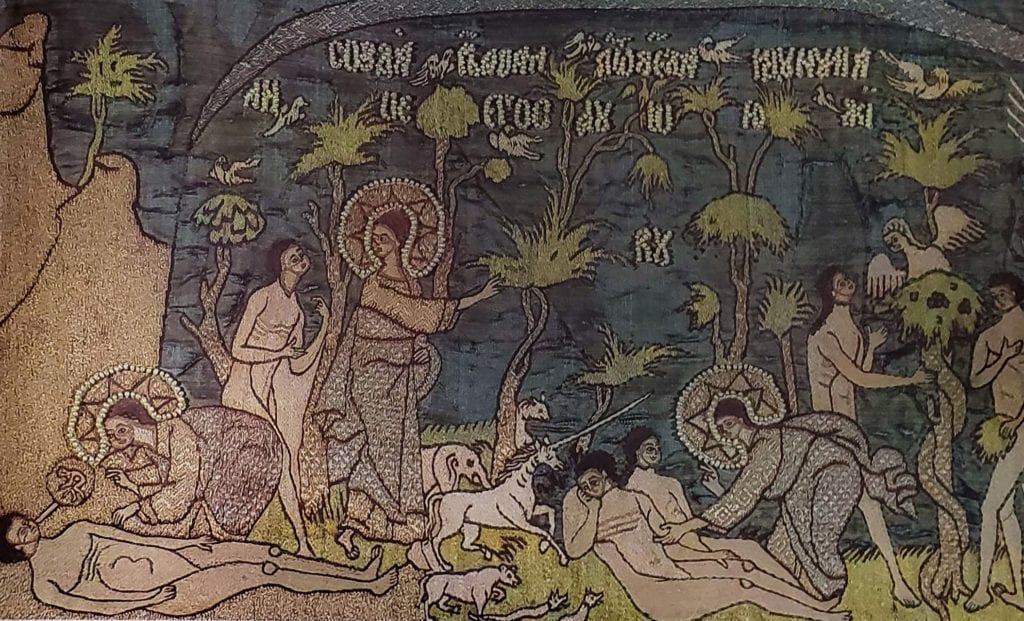

Among the outstanding works of medieval Russian embroidery are also the so-called “Suzdal'” [Illustrations 10, 11] and “Rjazan'” [Illustrations 24, 25] Aërs which depict in their centers the communion of the apostles with wine and bread, and on their edges, scenes from the Lives of Joachim, Anna and the Mother of God. The content and order of images on both Aërs are identical, which led their first scholar, V.N. Schepkina, to suppose that they were both based on an original work of south-Slavic origin: an embroidered Aër, several times larger, created for the well known Church of the Annunciation.[56]cf. V.N. Schepkin. «Pamjatnik zolotnogo shit’ja nachala XV v.» Drevnosti. Trudy IMAO. Vol. XV, issues 1-2. Moscow, 1894, pp. 35-68. The south-Slavic origin of the original work, according to V.N. Schepkin, can be seen in the inscription, and the name of the church from the last frame of the Life, which says “Annunciation” [«Blagoveschenie»].

The Suzdal’ Aër has an inscription which indicates that it was created for the Church of the Nativity of the Holy Mother in Suzdal’ by Konstantin’s Ogrofena “in the year 6900”. The last digit of the date remained unembroidered. A reference in the inscription to Metropolitan Fotius and Grand Prince Vasilij I clarify its date to 1410-1425; at the same time, Mitrofan, the bishop of Suzdal’ who is also mentioned here, is not mentioned anywhere after 1416. Considering the delay in Fotius’s activities as metropolitan, it makes sense to date this Aër to the years 1410-1413.

The name of the creator of this veil has so var remained unsolved. It is worth noting that she is here called by her husband’s name, “of Konstantin”, without a patronymic. It would seem that Konstantin was a well-known person in his time. And yet, in contrast to the inscription on the work above by Marija Semenova, which lacks the princely title, and only above the line is found the frequently seen and, it seems, almost-forgotten modest phrase “Servant of God”.[57] The name Konstantin was held by the son of Dmitrij Donskoj, who died childless in the Simonov monastery around 1440. But, his wife, who died in 1419, was named Anastasija. Whether or not he was subsequently married to another or who that second wife might have been is unknown. The names of the wives of other historical persons with this name are also unknown; for example, those of Prince Konstantin Vladimirovich of Rostov (died 1415) or Konstantin Dobrynskij. V.N. Schepkin’s supposition that Ogrofena was simply an artisan, and that the artist’s name is mentioned in the place of the donor, if they were not one and the same person, is not supported.

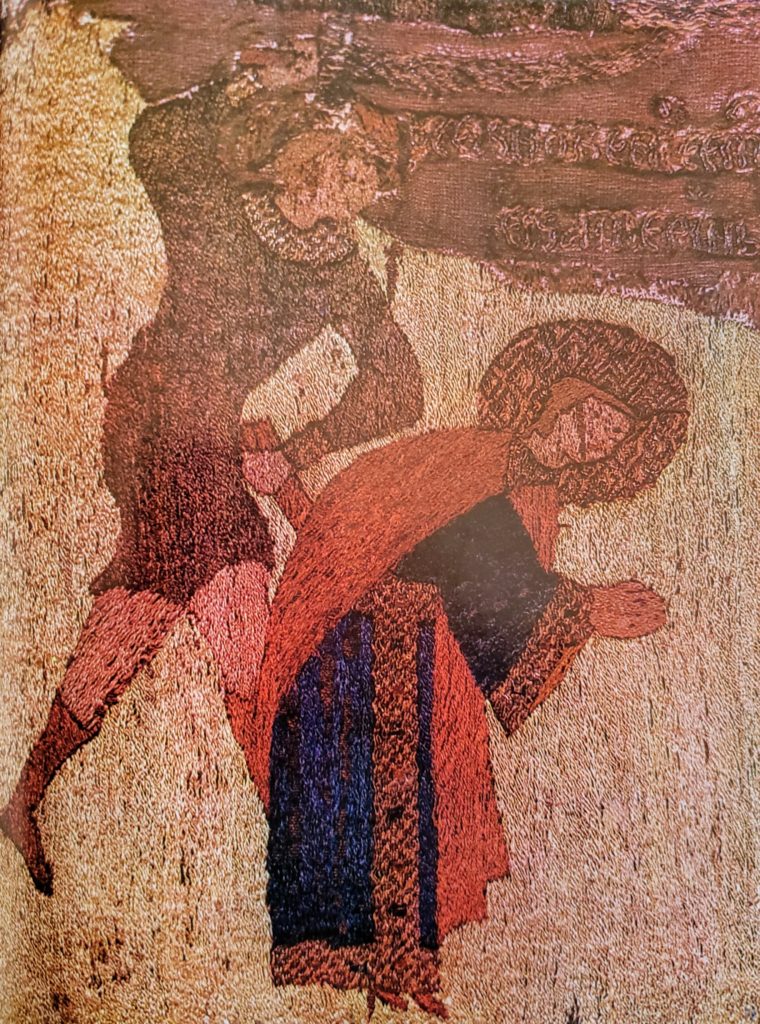

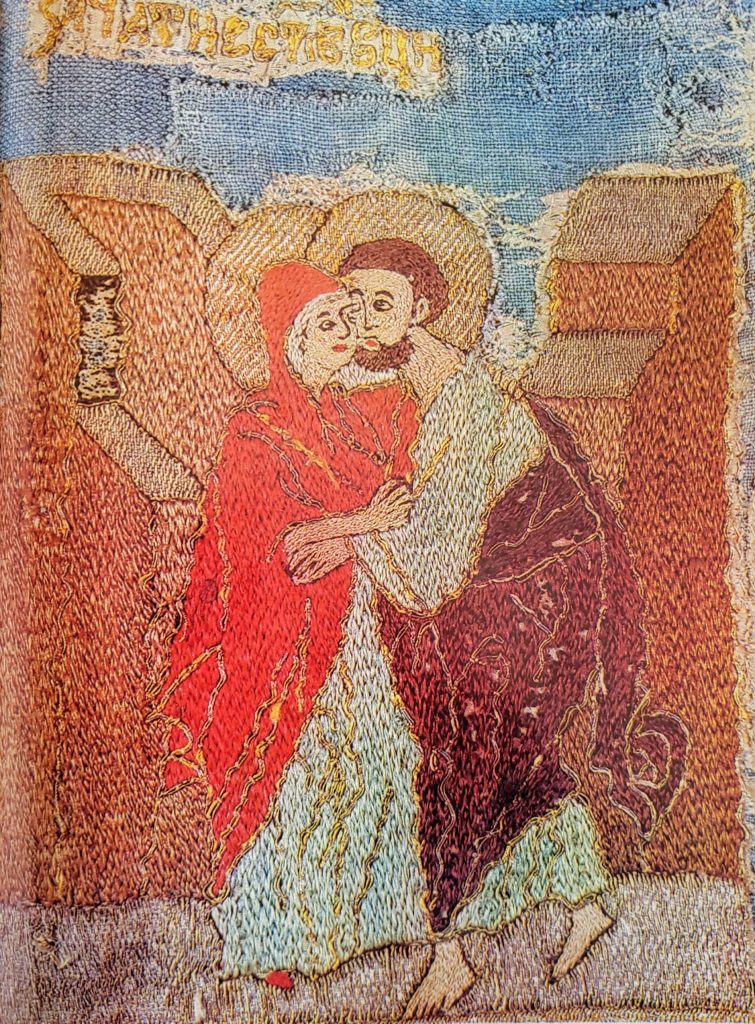

The Aër depicts the scenes of the Childlessness of Joachim and Anna and the birth of Mary, whose fate is followed through to the Annunciation, imbued with such sincerity of feeling that it is not possible to this as merely a blind copy of some prior work. It is entirely likely that this Aër was donated to the church, as was often done, as a prayer for childbirth. With the content following the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James,[58]I.Ja. Profir’ev. Apokrificheskie skazanija o novozavetnykh litsakh i sobytiakh. St. Petersburg, 1890, pp. 136-148. bringing us living pictures of the everyday life of the Jewish people, the artist and embroideress have given the work a purely Russian sincerity peculiar to Muscovite art of the first quarter of the 15th century. Particularly well executed are the scenes: “Joachim’s Exile in the Desert,” where Joakim, turning slightly, looks sadly at the weeping Anna; the scene where a servant coaxes Anna to stop her complaining and to put on a “bandage” (head band) and wedding robes; the “Conception”, where the artist emphasizes the spouses’ resurrected hope in their rush toward one another. But particularly solemn are the scenes of the “Caress” and “Arrival” of Mary. Here we see the delighted joy of the parents, their care for the baby, and the child’s first steps.

It is worth noting that the embroidery is carried out with relatively large stitches in split stitch, the lines of the faces are generalized, and upon closer inspection, as is often seen with works of this style of art, some figures and faces seem a bit primitive; but the embroideress has managed to convey superbly the overall design, roundness of line, grace of movement, tenderness, and a sincerity in the treatment of each separate figure, as well as of the entire composition. There is every reason to believe that the main icon-painter was a Muscovite and belonged to the artistic school of the marked genius Andrej Rublev. This is seen not only in the general orientation of his art, but also in the similarity of specific details in this Aër to other works by that school. For example, in terms of composition, the central section of the Aër is reminiscent of the Gate of the Assumption and of an icon in the Trinity iconostasis.[59]V.I. Lazarev. Andrej Rublev i ego schkola. illus. 152, 153, 154. Moreover, the style of the apostles and the general proportions of their figures is also very similar. Joachim and his characteristic head, with its slightly lowered brow, seems to have been based on a fresco in the Cathedral of the Assumption in Vladimir.[60]ibid., illus. 60, 90. There we may also find analogies for the architectural elements and for the trees, which resemble spreading palms.[61]ibid., illus. 116. Exquisite, balanced compositions, pictorial color schemes, lively and moving handling of subjects and images place this “Suzdal’ Aër” amongst the best of the works of Muscovite art of the first half of the 15th century.

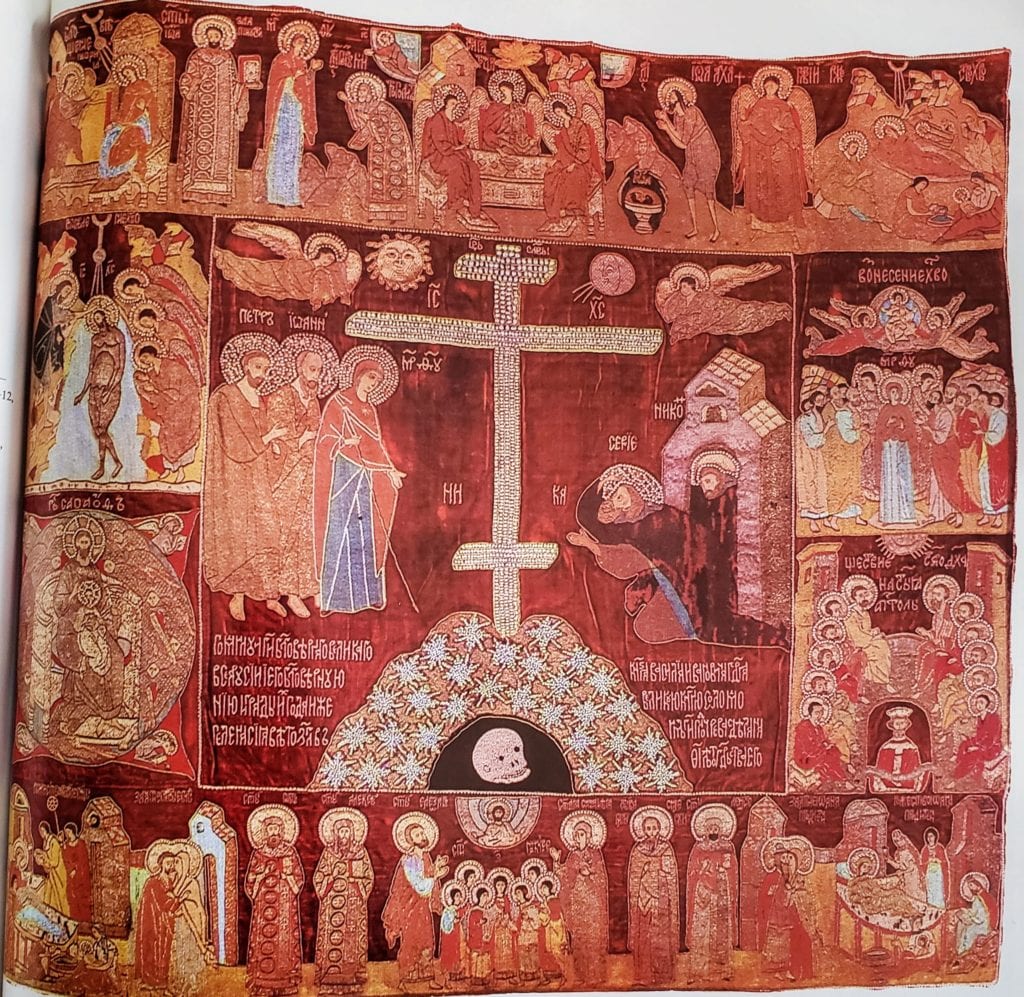

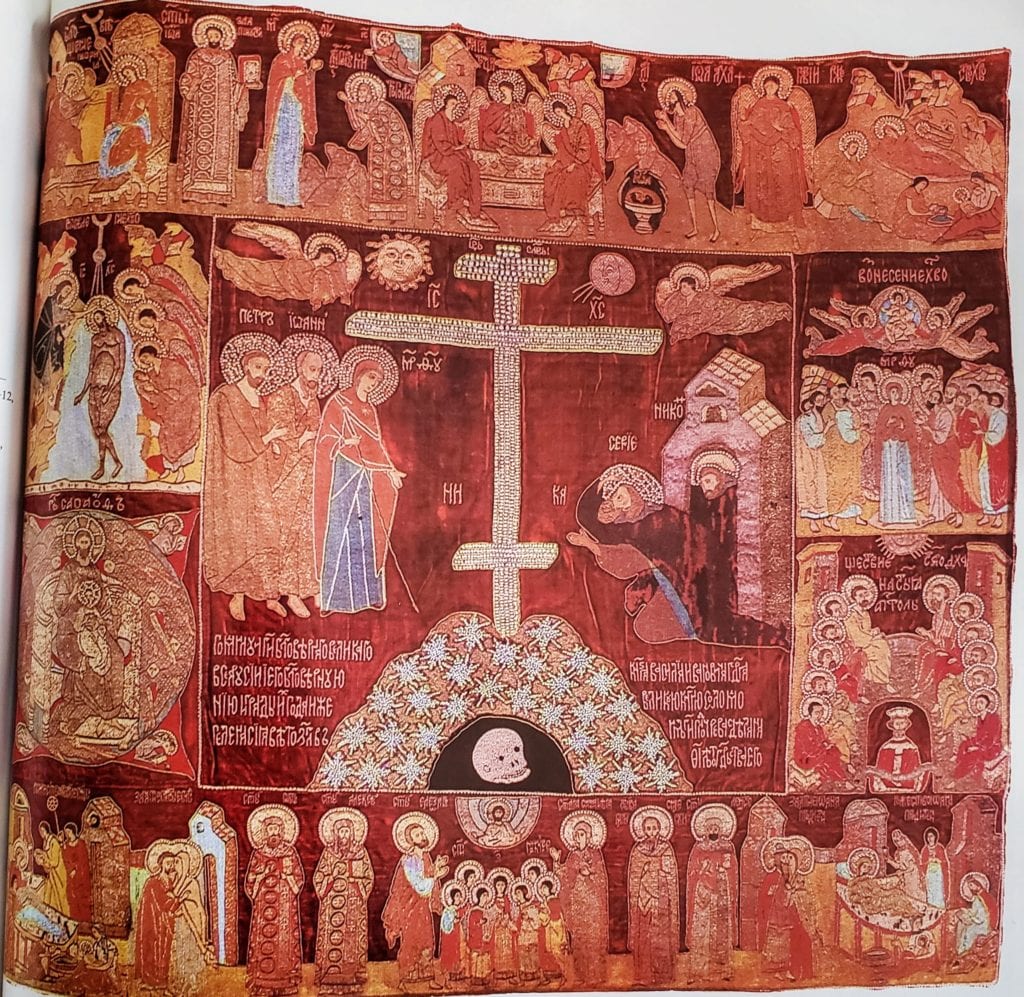

The podea [pelena], or more correctly, veil [pokrovets],[62]This appellation is based on its size, similar to that of another embroidered “Trinity” from the Godunov workshop which is called a sudarium [sudar’] in the inventory of the Trinity-Sergiev Monastery from 1641 (pp. 96 and 96 obv.), but which in subsequent inventories was called a “veil [pokrovets] with the head of Sergej” (cf. archive of the Zagorsk Museum) depicting “The Trinity, with Holidays” [Illustration 12] was undoubtedly created under the artistic influence of Andrej Rublev. The artist strove to convey the same composition and general tone of Rublev’s work, and the same pensive grace of its figures. A certain similarity in the form of the angels, proportions of the figures, and crease of the clothing is noticeable. At the same time, this embroidered “Trinity” is not a direct copy of an icon. The angels are no longer sitting in a tight bunch, nearly touching one another. The distance between them has increased, and the table has grown longer, somewhat violating the roundness of the entire composition. Much attention has been given to the details of this podea. The chambers, hills, and the Oak of Mamre take up a large area here. On the table, instead of one chalice, there are three, along with a salt cellar and loaves of bread. The color scheme also diverges from that of Rublev. The color of clothing is packaged differently. Between the angels, remnants of a dark-green hill are visible. The ground for this podea was originally a dark-brown damask.[63]In the 18th century, the images were cut out along their edges and transferred onto a crimson velvet. During restoration in 1951, it was replaced with a rough blue crash. In comparison to an icon, the color scheme on this podea is of heavier and more saturated tones.

The images on the outer border of the work also have a certain compositional similarity to works created by Rublev and those working in his atelier. Parts of it mirror the icons in the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin; other parts, the Trinity Cathedral. It would seem that these and other compositions were in common use amongst Muscovite artisans of the 15th century. We consider it possible to date the podea to the second half of that century, when similar variants of the Rublev “Trinity” were circulating throughout Muscovite art.[64]This author does not agree with the opinion of V.I. Antonova, who dated this work to the very beginning of the 15th century and believes that the artist who drew this icon was Andrej Rublev himself, who created here the first draft of his “Trinity” («O pervohachal’nom meste “Troitsy” Andreja Rubleva.» Gos. Tret’jakovskaja galereja. Materialy i issledovanija. Issue 1. Moscow, 1956, pp. 26-30.) See the icons depicting this variant of the “Trinity” in the Andrej Rublev Museum: one from Borodava near Kirillov from 1486 [item 54], one from Volokalamsk from the 1480s [item 21], and one from Uglich [item 106] one from Aleksandrov from the early 16th century, et.al. The artisan who embroidered this work has given particular attention to the central image, and with rare artistic skill has conveyed the artist’s subtle design. The images on the border are worked a bit more roughly, with faces and other details worked in a generalized manner.

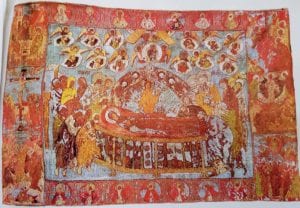

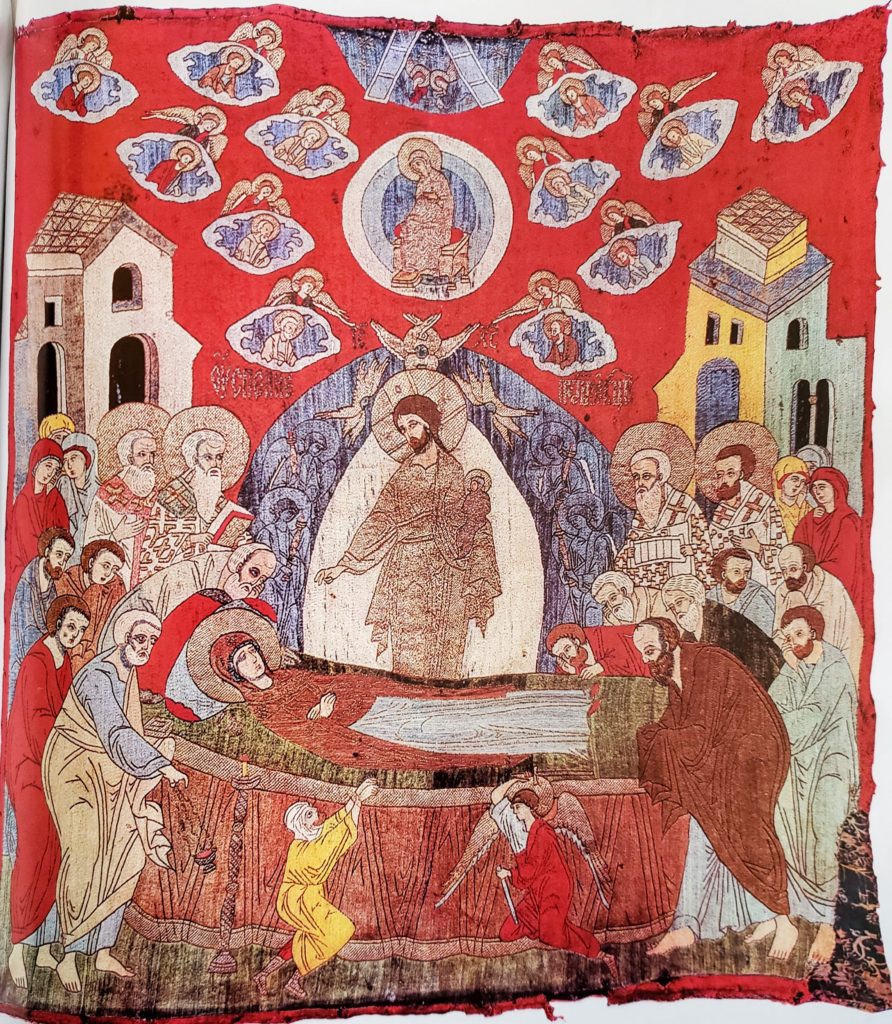

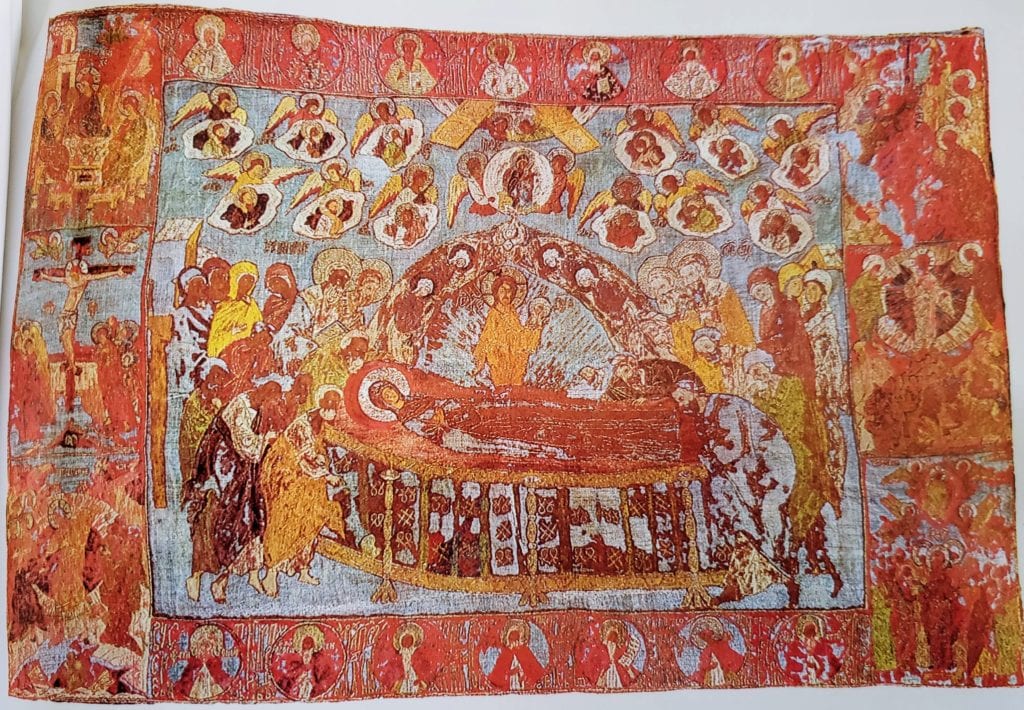

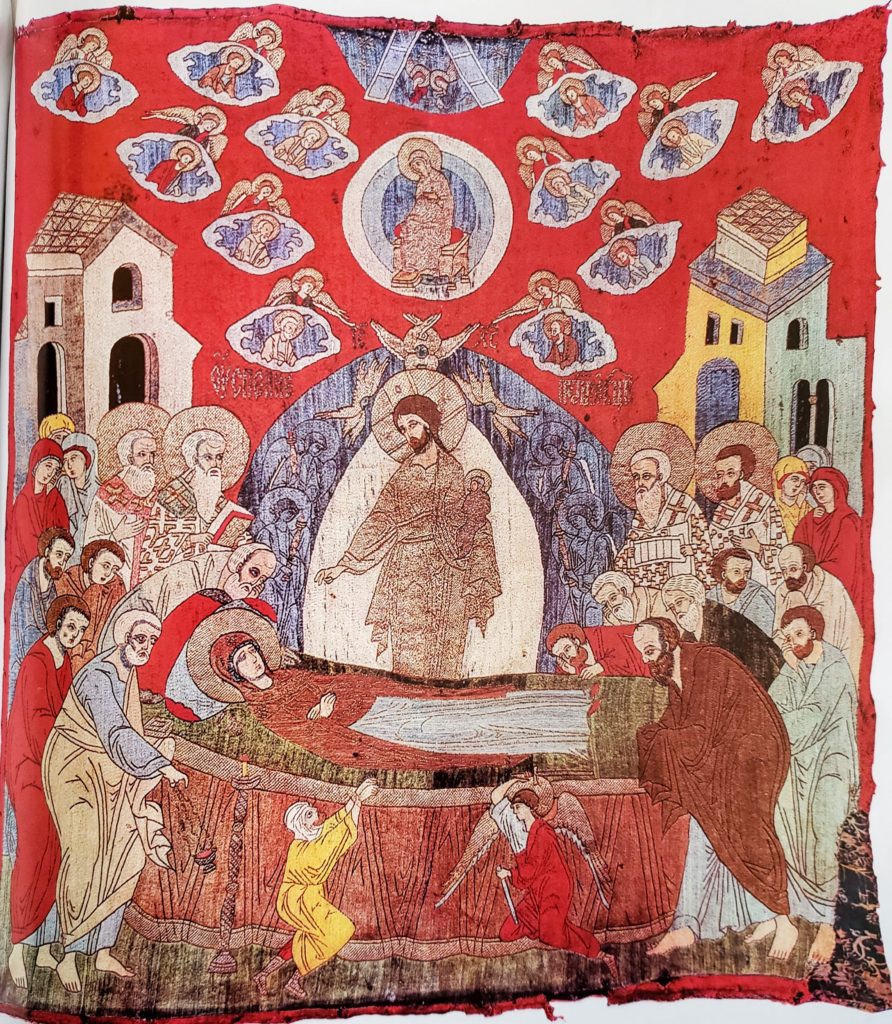

Another depiction of the “Trinity”, similar to the podea above and combined with the holidays in the same order but with different variations, attributed to the circle of Russian artists of the early 15th century, was embroidered onto a podea from the Our Lady of Vladimir Monastery [Illustration 13]. The center of this podea depicts the so-called “Cloudy Dormition.” The composition is oriented horizontally, and is very saturated in color. Around a long bed, the apostles and women stand in two large groups. The sky is full of angels which bear the Holy Mother and apostles aloft on clouds. This is reinforced by the saturation of color in this podea, which was originally dominated by violet-brown, cherry and raspberry tones.[65]This impression is broken by the gaps in the original ground fabric, a brown damask which was replaced with a light blue rough fabric during restoration. Stylistic details of the work, its iconographic similarity of its composition to Muscovite art, the proportions of the slender figures, and the soft expression of the faces all speak to its Moscow origin.

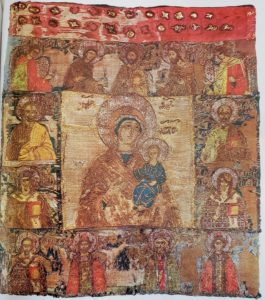

Two other podeai are similar to the “Dormition” podea above. On one of these [Illustration 14], the center depicts two groups of saints standing in prayer across from one another. Above them is embroidered “Our Lady of the Burning Bush” in a relatively uncommon variant, with “Our Lady of the Sign” shown in front of the burning bush. To the right is Moses, kneeling and removing his shoes; to the left is flying angel. The upper border depicts a Deësis composition with Our Savior Not Made By Hands in the center. It is notable for its lack of the Holy Mother and John the Baptist. Below are embroidered a number of saints and Russian clergymen, including Varlaam and the Prince Ioasaf.[66]jeb: According to the tale, Ioasaf or Jehosaphat was a Prince of India whom Varlaam convinced to become a Christian. This story was quite popular in medieval Russia, and can be found on many icons.

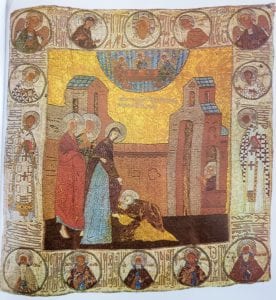

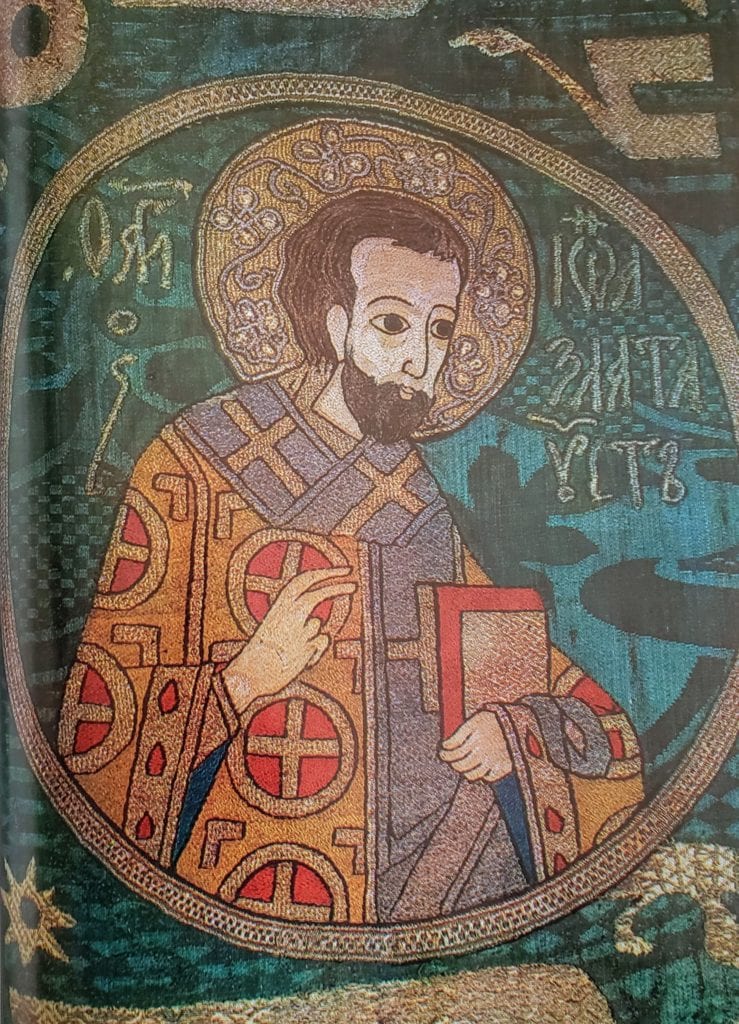

Another podea [Illustration 15] depicts Sergius of Radonezh and his student Mikhej’s vision of the Holy Mother and Sts. Peter and Paul. The composition portrays a relatively common variation of this subject, with Sergius on his knees.[67]N.A. Majasova. «Masterskaja khudozhestvennogo shit’ja knjazej Staritskikh.» Soobschenija Zagorskogo muzeja-zapovednika. Iss. 3. Zagorsk, 1960, p. 54. Sergius is shown at the very feet of the Holy Mother, who slightly bows forward, as if wanting to lift him up. A surprised Mikhej impetuously leads out of the cell window. These details give the scene life and a certain immediate warmth. The composition of the border almost completely duplicates that of the aforementioned podea, except amongst the half-length images, here we have the full-length figures of Sts. Nicholas and John Chrysostom, the latter of whom was likely the name day saint of Grand Prince Ivan III.

Both podeai are embroidered in multi-colored silk on a bright-yellow damask, and are very portrait-like. The figures have the thin, slightly elongated proportions that were common in Muscovite art of the last quarter of the 15th century. The Muscovite origin of these podeai is attested to by the very subject of Sergius of Radonezh and the selection of saints which were particularly honored at that time in Moscow. These include the Moscow Metropolitans Pjotr and Aleksej, Leontij of Rostov, Sergius of Radonezh, Varlaam of Khutyn, Savva Visherskij, and Dmitrij Prilutskij. The podeai were undoubtedly produced in the same workshop in the second half of the 15th century. The works’ style and character of design, the composition of the border scenes, the tracing of the inscription, the color scheme, and technical methods all attest to this. It is also likely that the “Dormition” podea also came from the same workshop. Although it has a completely different color scheme, it resembles the podeai listed above in its design of elongated figures, lifelike poses, and the tender facial expressions. Particularly similar are the half-length figures of the saints on the borders, the spaces between whom are filled with inscriptions which are carried out in almost identical calligraphy. It also should be mentioned that on all three podeai, the faces were worked in one and the same unstable silk, which in places has darked to a shade of brown.

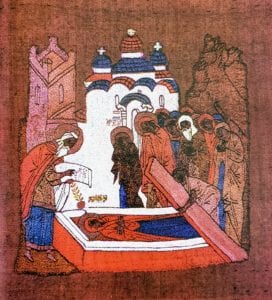

A different artistic direction is seen in a small podea with a composition of “The Burial of St. Anne” rarely seen in Rus’ [Illustration 16]. The artist strove for a particular concretization of details. The moment of the burial is extremely precise: a priest reads the last rites just as the tomb is covered with its lid. Instead of the stylized basiliciform or stepped buildings common to the majority of icons painted in the 15th century, a white-stoned, single-blocked temple with three domes rises behind the crowd. There is even a roof over the door, supported by curved brackets atop two pillars. Particularly expressive is the figure of the weeping Holy Mother, who is draped in a brown maphorion. She is a bit separated from the crowd and the other women follow a bit behind her. This serves to focus the viewer’s attention upon her. Her grief is underlined by the standing row of sorrowful figures with bowed heads. The artist and embroideress carried out this main element in colored accents: the red maphorion on Anna in the tomb and the dark silhouette of the Holy Mother against the surface of the white walls of the cathedral. The cathedral occupies such a significant place that it suggests it was inspired by a particular structure, possibly the newly built Moscow Cathedral of the Dormition (1479), which it resembles. It would seem that the podea was created in Moscow in the last quarter of the 15th century. As evidence for this dating, we have the well-known narrative and concretization of development and the shape of the temple, which is not found in earlier works.

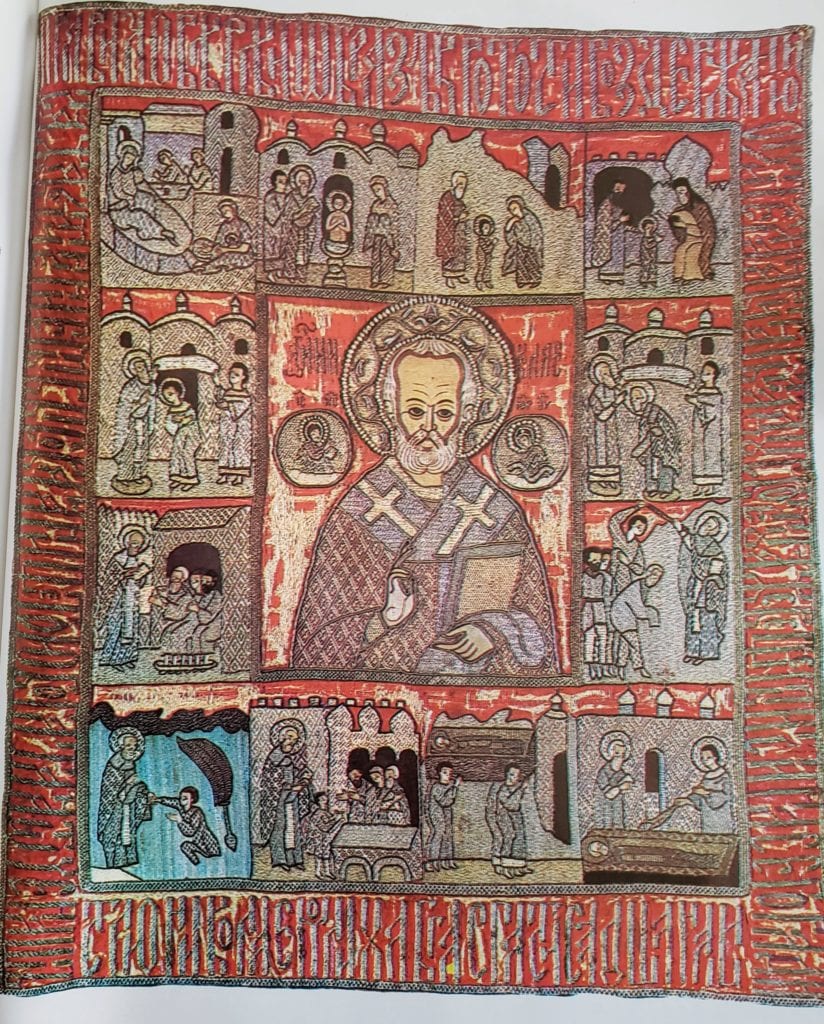

There are also significant works from the Novgorod school extant from the 15th century. There is an array of works tied to the name of the Archbishop Euphemius II (1429-1458). Euphemius is historically famous for his construction of buildings. Under his leadership, many churches, the clock tower, the Palace of Facets, and the Archbishop’s Palace in Novgorod were constructed or renovated, and decorated with paintings or icons. He was the ktetor of the Vyazhitskij and Khutynskij Monasteries. Most likely, Euphemius also ordered works of embroidery from a workshop in one of the female monasteries under his ward. In 1439, Archbishop Euphemius “gilded the tomb of Prince Vladimir Jaroslavich … and ordered and presented a veil; and also likewise decorated his mother’s grave.”[68]Novgorodskie letopisi. St. Petersburg, 1879, p. 139. The museums of the Moscow Kremlin house the so-called “Puchezh” Epitaphios,[69]The Kremlin Museums, no. 18652 op. The name of the “Puchezh” Epitaphios comes from the town of Puchezh, in the Novgorod region, where it was discovered in 1930. It has been published many times (cf. Der Moskauer Kreml die Rüstkammer. B.A. Rybakov und Mitarbeiter. Prague, 1962, illus. 86, 87).[70]jeb: See my translation of an article about this work, along with photographs: The Puchezh Epitaphios of 1441 and Novgorodian Embroidery in the Time of Archbishop Euphemius II with an embroidered inscription: “In the year 6949 [1441] the creation of this veil: was ordered: by the venerable archbishop of Novgorod the Great, Lord Euphemius. Amen.” This work is of particular interest due to its picturesque style. In the clothing here, one color gradually transitions into another. The light blue fabric has dark blue tones in the folds, and lightens to white in highlighted areas. Light brown silk is combined with light yellow and dark brown; yellow, with dark and light green. The picturesque style is also seen in the “peacock eyes” in the angel’s wings, and in the floral-covered ornamentation of the benches. Very similar in both composition and artistic technique to the Puchezh Epitaphios is another epitaphios from the Khutynskij monastery, which quite likely was created by the same artist.[71]This item is now in the Novgorod museum [2132] (cf. A. Svirin. “Une broderie du XV siécle de Style pittoresque.” L’art byzantine chez les slaves. Paris, 1932, table X.2; A.N Svirin. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo, p. 38).

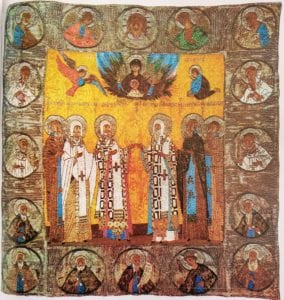

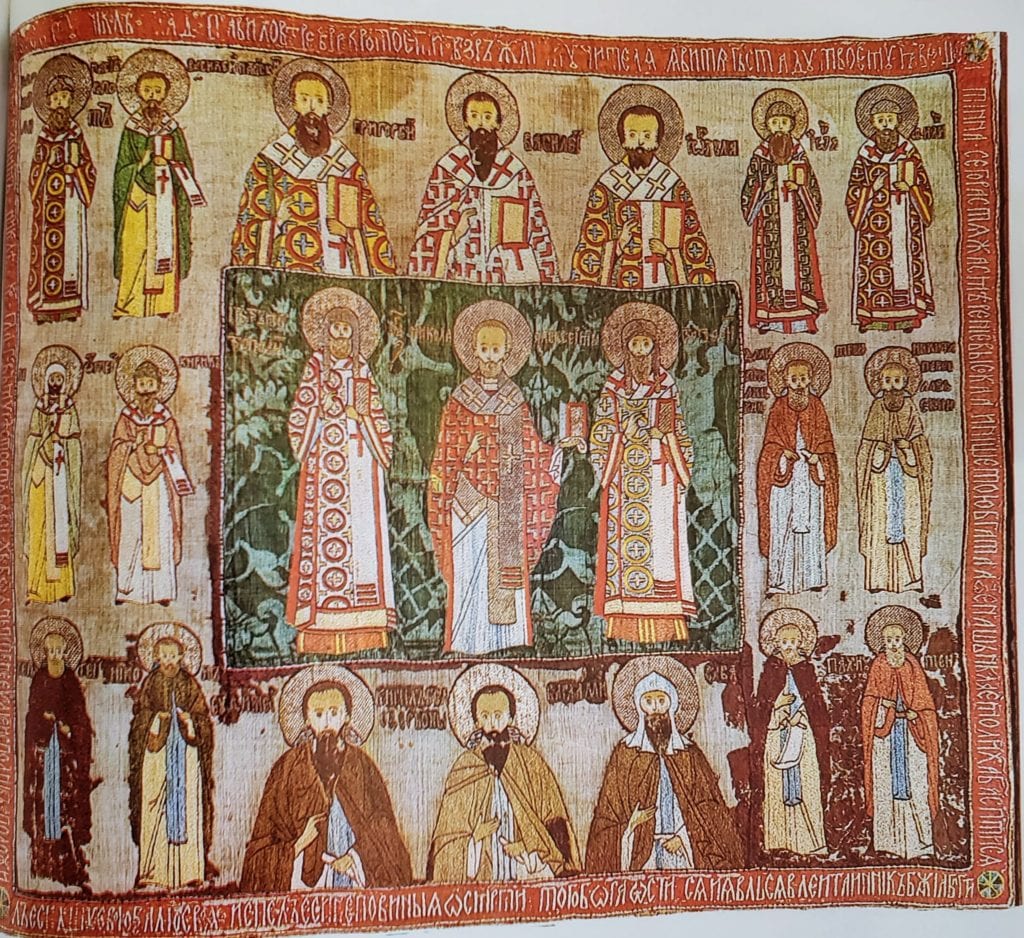

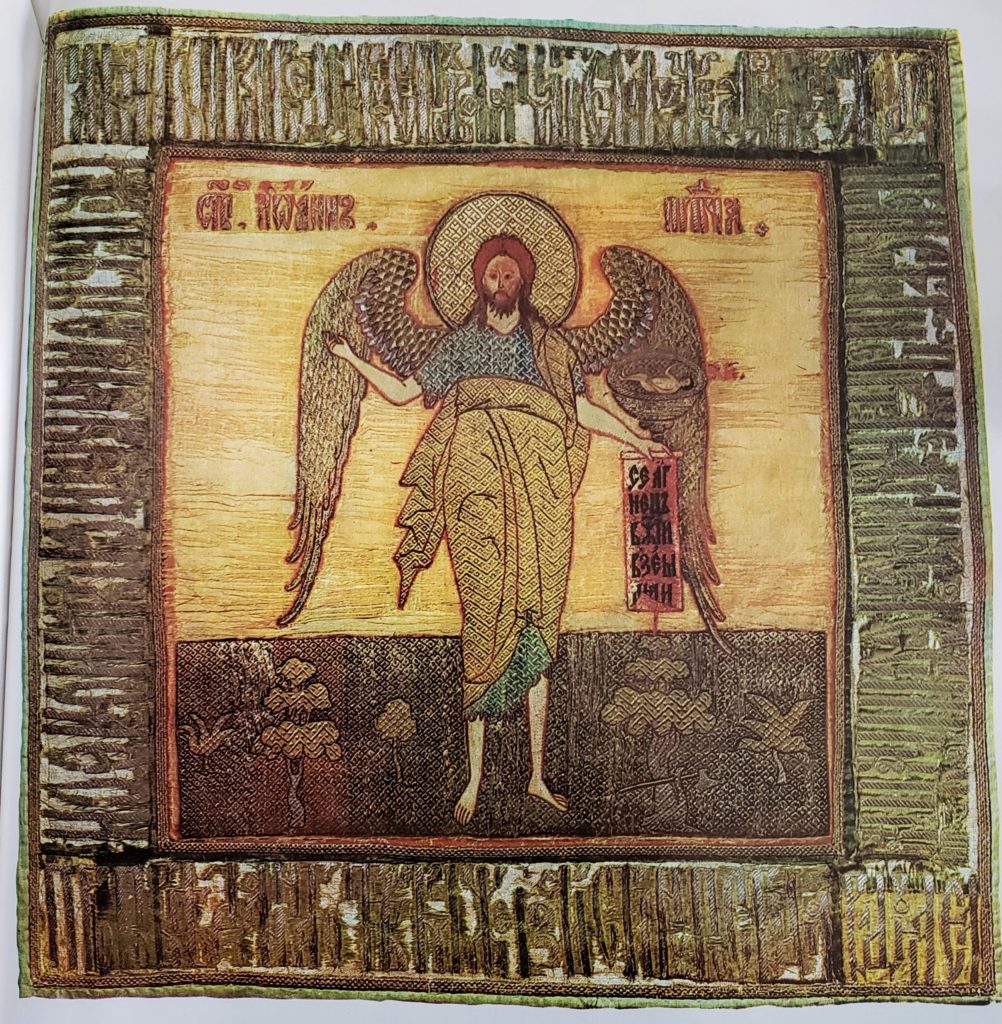

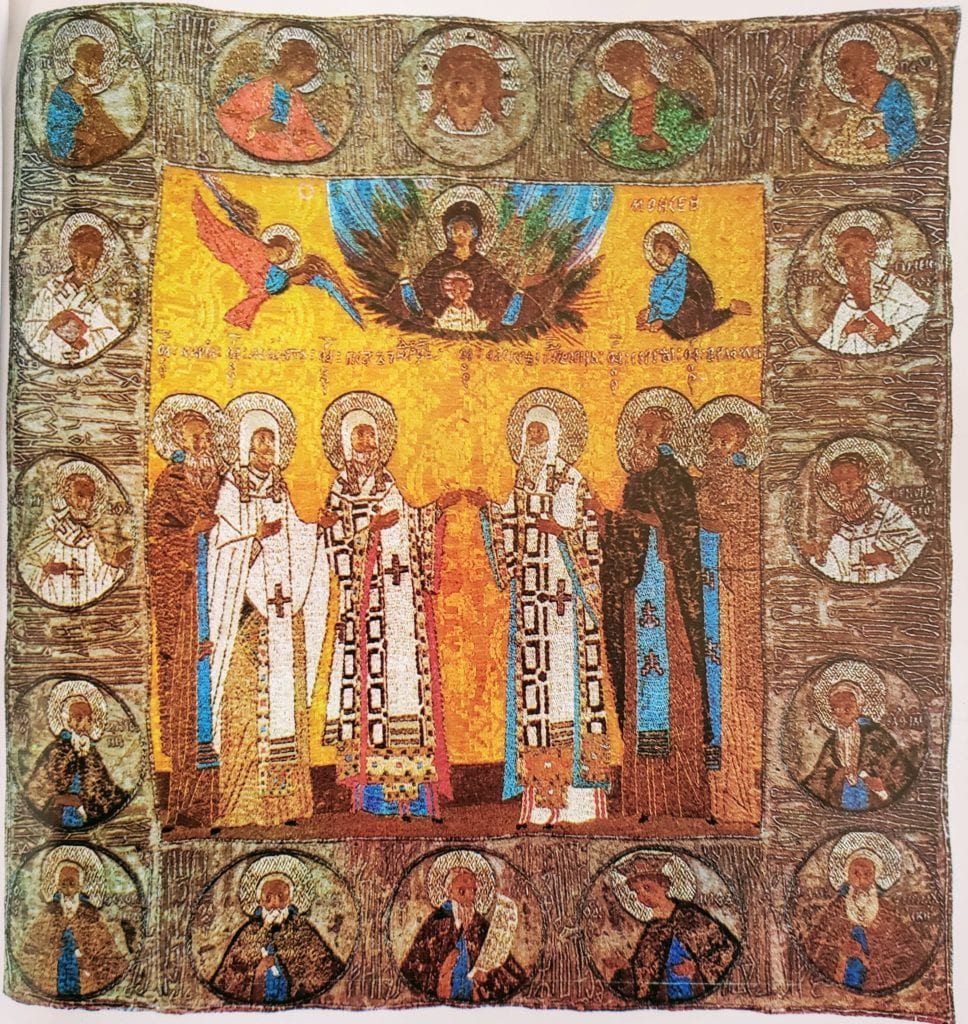

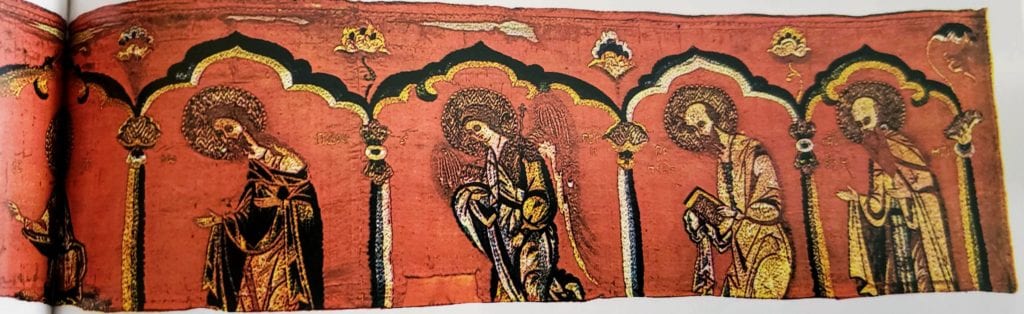

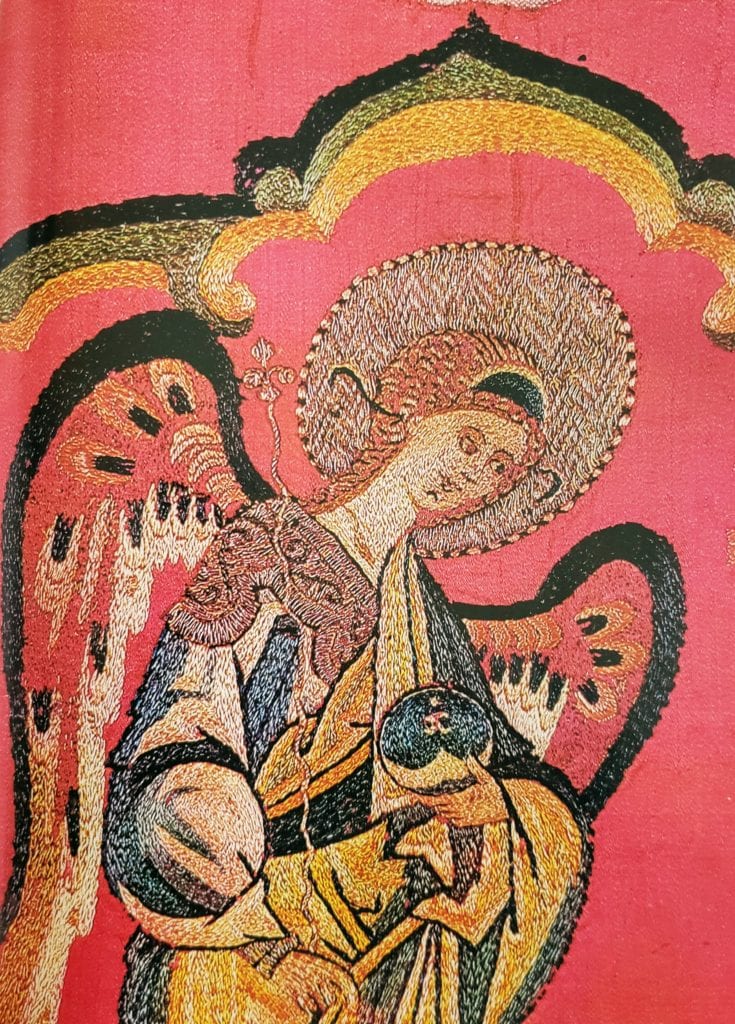

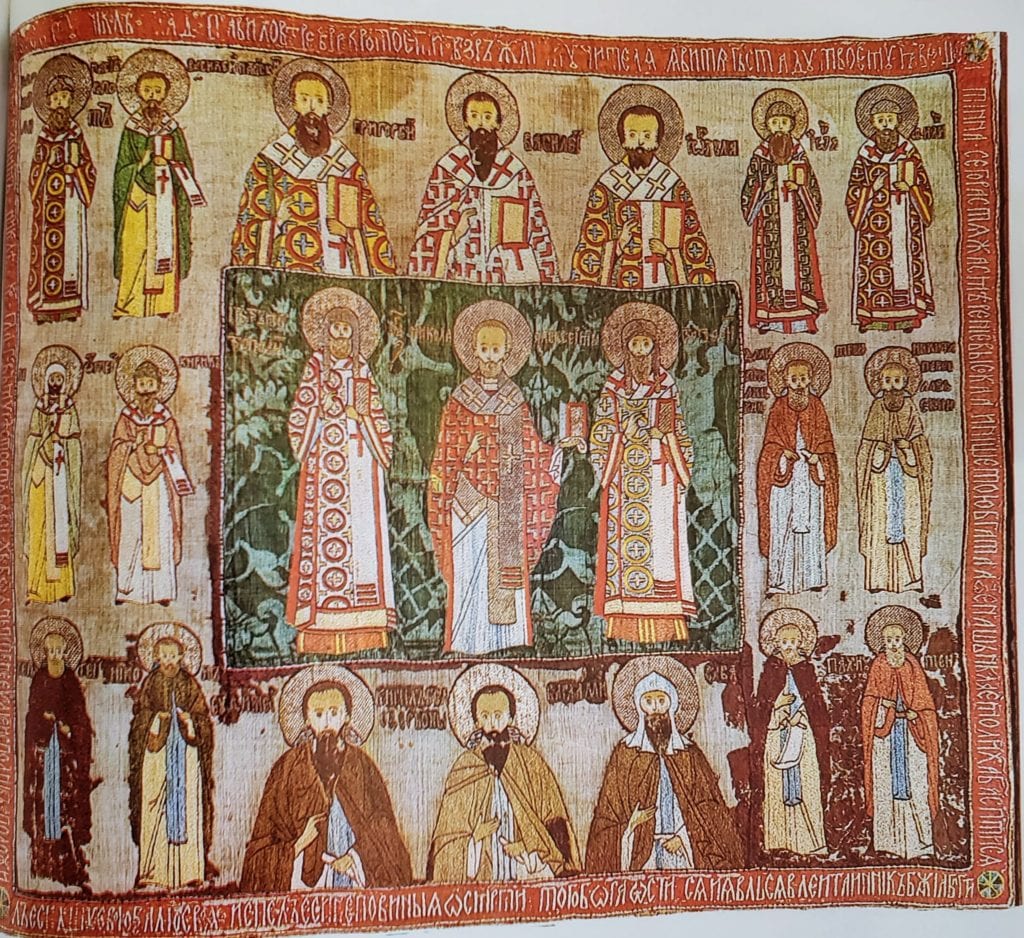

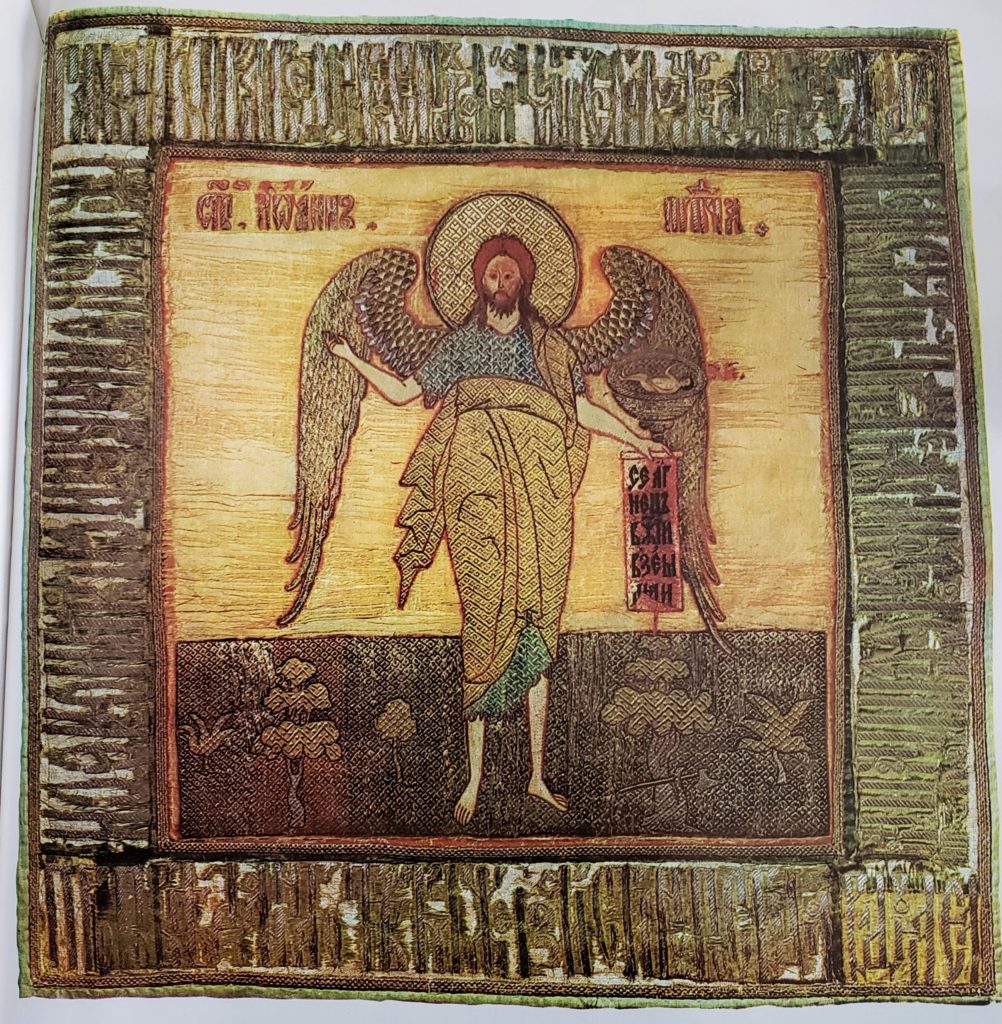

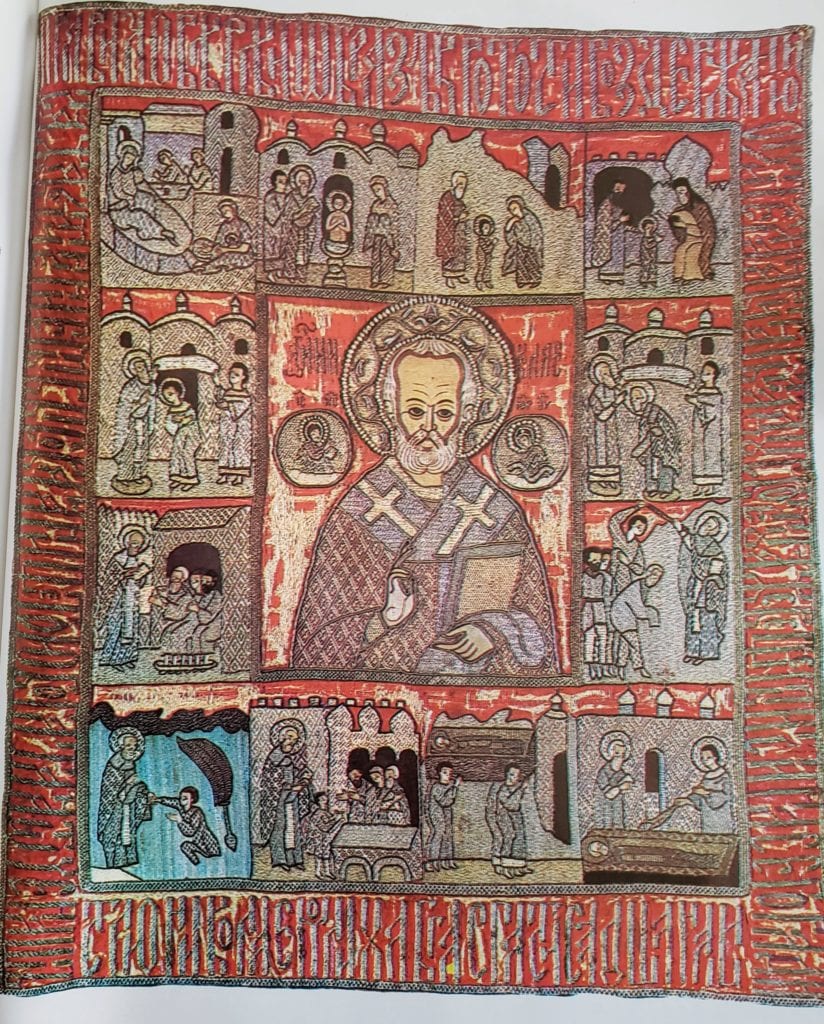

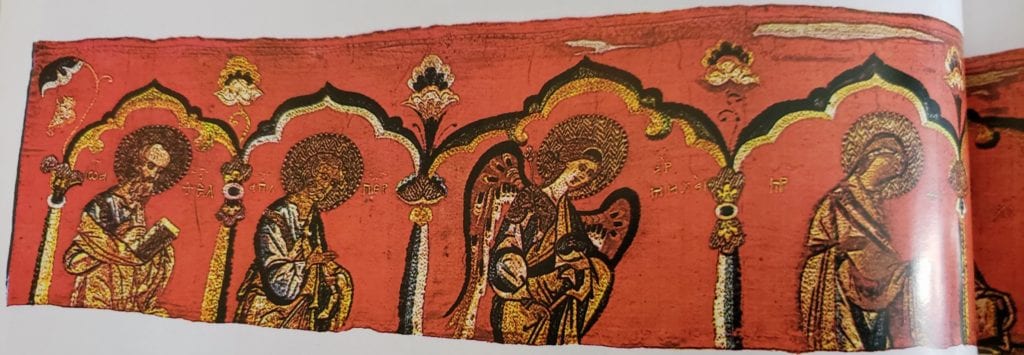

Euphemius’s atelier also produced the famous “Deësis Row” [Illustrations 17, 18][72]The “Row” was located in the Trinity-Sergiev Lavra and is listed in the earliest surviving inventory, from 1651. The fact that Euphemius II was well known as an opponent of Moscow, it would seem, should have precluded it from being donated to a monastery in the Moscow region. It is possible, however, that it was a reciprocal gift for the epitaphios of Grand Prince Vasilij II the Blind, the inscription of which specifically mentions its addressee – Archbishop Euphemius. It is also possible that the “Row” came to the monastery among other works of art captured from Novgorod by Ivan the Terrible. The “Row” has not survived in its entirety. The lower part of the figures is cut off, the border which, most likely, contained the donor inscription is missing.[73]jeb: The Deësis Row is a part of the iconostasis in an Orthodox Christian church. It is typically located immediately over the Royal Door through the iconostasis, with Christ sitting immediately over the door, flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, often along with other saints or angels depicted in full-length. In this case, the Deësis Row was presumably part of a larger embroidered iconostasis. The ethereal figures of the “Row” are placed in graceful pictorial frames with lush flowers in the corners. In the center, the Savior is seated on His throne; on either side of him stand the Virgin Mary, John the Baptist, the archangels, and the apostles Peter and Paul. This canonical grouping is completed by the especially revered Archbishop Euthymius The Great and John the Theologian, who were his name day saints.[74]In their honor, Euphemius II built and decorated two churches: in 1439, the Church of St. John the Theologian in Vjazitskij Monastery, and in 1445, a chapel to Euthymius the Great in the entry hall of his palace.

That this “Row” should be attributed to Euphemius’s workshop is supported not only by its selection of saints, but also by the general pictorial style of this work, which is similar to that of the Puchezh Epitaphios. Here too, we see the same gradation of colors, the same subtle transitions from light to dark. Moreover, here this artistic technique has reached its greatest resonance. Fancy bell-shaped arches, resting atop pillars with unusual flower-shaped capitals, growing from them out of them on curved stems, and the lush and subtle flowers create a fabulous environment for the subtle, slender figures of the figures, clothed in robes which almost seem to be iridescent in the sun’s rays. A feeling of spring-time joy, glistening in all of the colors of the rainbow, emerges from this extraordinary work. The singular style of the Euphemius workshop, which researchers have called “pictorial”, did not receive any greater development in Russian embroidery. It is true that few works from the 15th century in this style[75]Two epitaphia in this “pictorial” style are stored in the Novgorod Museum [2131, 2097]. One one of them, amongst the images on the border, are embroidered the Novgorodian saints Nicetas the Goth and Jonah, who it would seem were the name day saints of the donor-martyrs Kondratij and Tat’jana. One more less skillfully-worked epitaphios is stored in the Russian Museum [195].have survived, but in the mid-16th century, several echoes of this pictorial style are seen in one of the epitaphia from the workshop of Princess Evfrosina Staritskaja, which incorporates the best traditions of the art of medieval Russian embroidery [Illustration 44].

D. Ainalov ties the appearance of this style in Novgorodian embroidery in the 15th century to Western European influences.[76]D. Ainalov. Geschichte der russischen monumentalkunst zur Zeit des Grossfürstentums Moskau. Berlin and Leipzig, 193, p. 117. Certainly there does exist in works of western medieval embroidery a light-and-dark style, a technique which was taken from portraiture. The Novgorodians’ familiarity with this art cannot be ruled out, as Novgorod had undertaken extensive trade relations with its neighboring states since ancient times, and Archbishop Euphemius had German artisans who worked alongside his Russian masters. But this acquaintance could only enrich the traditional methods of medieval Russian embroidery to a certain extent. Despite its great originality, Euphemius’s “Row” does not vary far from the general circle of Russian works of art. This is attested to not only by the accepted Russian iconography, but also the technique of embroidering in silk split stitches and in couched spun gold threads which was common to Russian embroideresses, in the form of the keeled arches which were widespread in 15th century Russian architecture, and even in the flowers, encountered in icons[77]The same sprigs with fringed leaves as on the last columns in the “Row” are also found on the mid-15th century Novgorodian icon “Daniil in the Lion’s Den” (Novgorodskij istoriko-arkhitekturnyj muzej-zapovednik. Leningrad, 1963, pp. 10, 30). Here too, the leaves have the same gradation of color from dark blue to light blue and white. The similarity between the “Row” and this icon can also be seen in how the clothing and various details of the figure of Daniel have been worked. It is possible that here we have two works from artists from the same school. and frescoes and which have ties to Russian folk art. The overall structure of this work is also accordant with that style.

No works of Novgorodian embroidery dated to the second half of the 15th century have survived to modern day. But, it would appear that a small podea with a depiction of “The Entombment of Christ” [Illustration 19] belongs to that time. This work is especially pictorial. The action unfolds in front of a backdrop of hills, which to the left are light blue and to the right are green. The clothes of Christ’s mourners and of the angels are of bright local colors [«lokal’nye tsveta»]. The tomb is decorated with flower petals. The composition of the podea is reminiscent of an icon of the same subject, typically attributed to the Novgorod school of painting.[78]V.I. Antoneva, N.E. Mneva. Katalog drevnerusskoj zivopisi. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1963, Nos. 102 (illus. 73), 106 (illus. 76). Here we see the same cast of characters, the same pathetic pose of the Magdelene, Christ’s body swaddled like a mummy, and the same hills with their squarish summits sticking up. The detailing is also characteristic for Novgorod – the cross reminding us of recently completed events, the ladder which Nicodemus busily clears away. The realistic earthly character of the proceedings is emphasized by the body of the recently deceased being surrounded only by people, with the “heavenly forces” carried away to the edges of the composition. At the same time, the soaring seraphim and the archangels bowing in prayer denote the singularity of this event, and the connection of heaven of these earthly events.

It should be noted that not only the very composition of the podea has analogies to Novgorodian art. The silhouettes of the archangels, as well as the layout of the folds of their clothing are similar to icons of the Novgorod school from the Gostinopol’ Row, dated to 1475.[79]ibid., No. 101 (illus. 79).

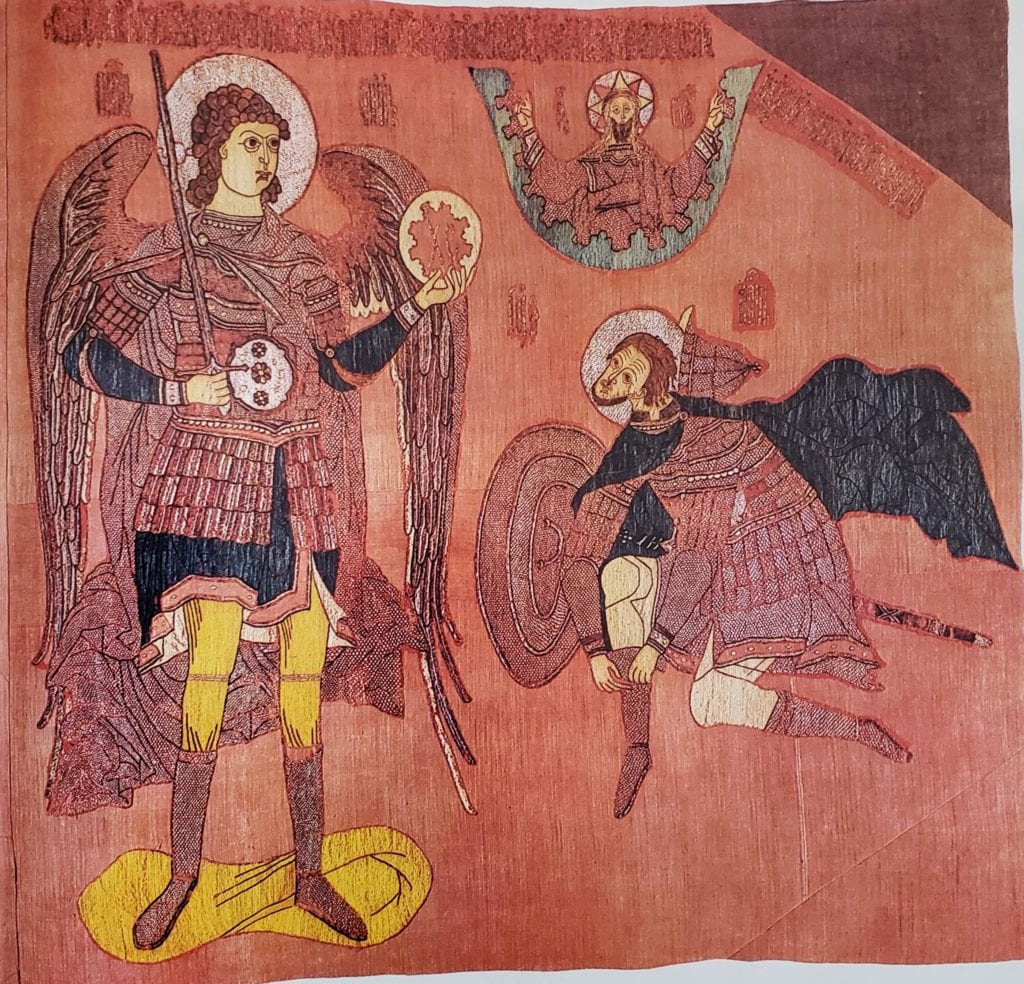

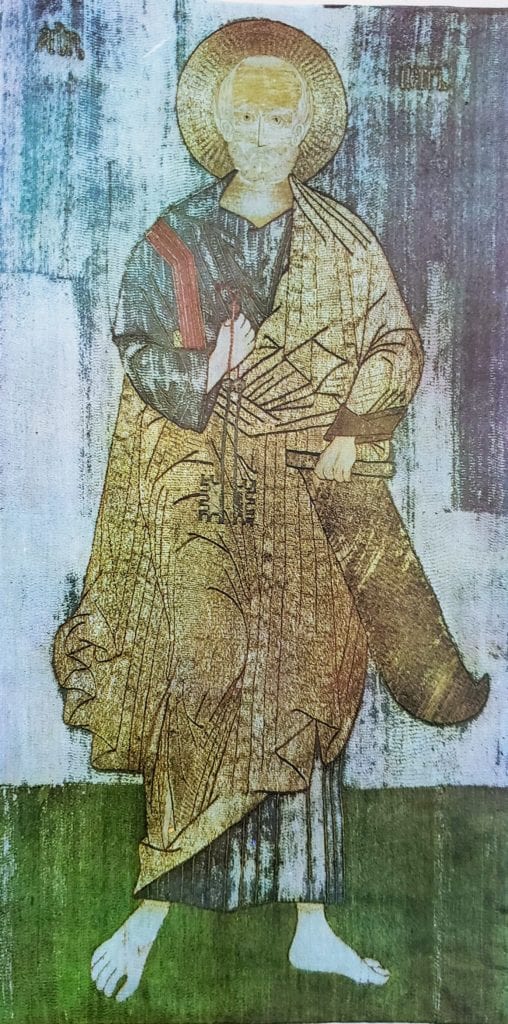

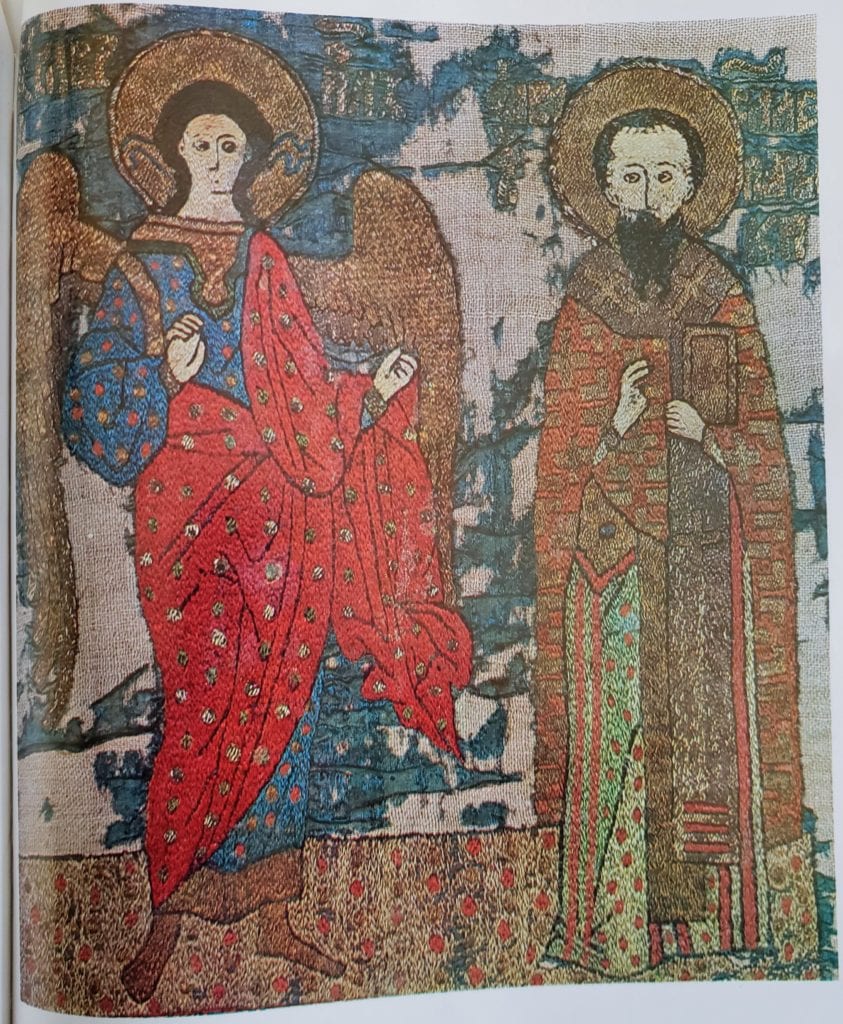

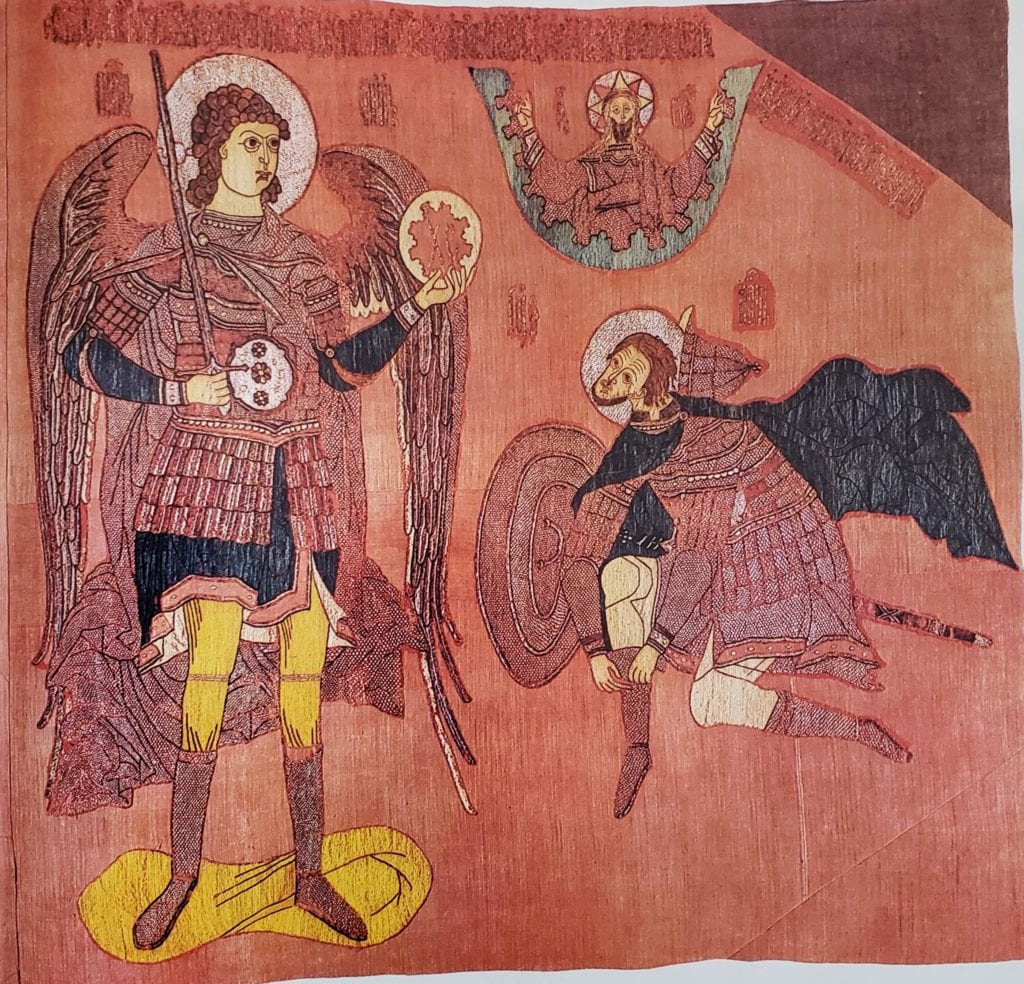

We can attribute, it would seem, to Novgorodian art of the late 15th-early 16th century two large embroidered depictions of the Archangel Michael [Illustration 20] and the apostle Peter [Illustration 21]. Their straight-faced, front-facing figures stand firmly upon the earth. They are relatively stout, with large haloes, large feet, and somewhat small hands. They are somewhat odd looking for the 15th century, in their poses and the expressions on their faces; their majesty and mild calm are more peculiar to the late 15th-early 16th century. At the same time, it is difficult to attribute them to Muscovite art of that time. Here we do not see the fine gradation [of color] intrinsic to Rublev and hits followers, nor the refined grace of Dionysius’s school. The figures’ staging and their weightiness are reminiscent of Novgorordian images of earlier times. The technique of the embroidery is typical of the 15th century, worked in stem stitch in colored silks and in gold with inconspicuous couching. The main coloring of the images are the dark blue silk base and green ground. On the image of St. Peter, this is enriched by the gold of his clothing and halo. On the image of Archangel Michael, a bright-red cloak is thrown over his golden armor. His wings are worked with an unusual volume, as if they were bent forward. This curve over the shoulders emphasizes his bold resilient lines, creating an internal volume filled with yellow silk. Instead of a sword sheath in his left hand, the Archangel holds an unrolled scroll, as does St. Peter. Thus too is the archangel shown on Dionysius’s frescoes to the left of the gate in the cathedral in Ferapontov Monastery.[80]Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol 3. Moscow, 1955, p. 500. The Archangel Michael, patron saint of military glory, unites here the function as both angel and watchdog. Both works are of relatively large size, and they have been generally accepted to consider them to be remnants of a Deësis row. But, the straight-faced, non-prayerful poses of the figures, the archangel’s warlike clothing, atypical for a Deësis, and the analogy to the frescoes in Ferapontov Monastery provide an opportunity to suggest that the original placement of these figures – the guardian angel and Peter, the guardian of the gates of Heaven – on the edges of the pillars guarding the western entrance into a church. The Aleksandr-Svirskij Monastery, from whence these icons came, was founded around 1494. In 1506, the Trinity Cathedral was built there, with a chapel dedicated to the apostles Peter and Paul. It would seem that we can also attribute the creation of these embroidered icons to that time.

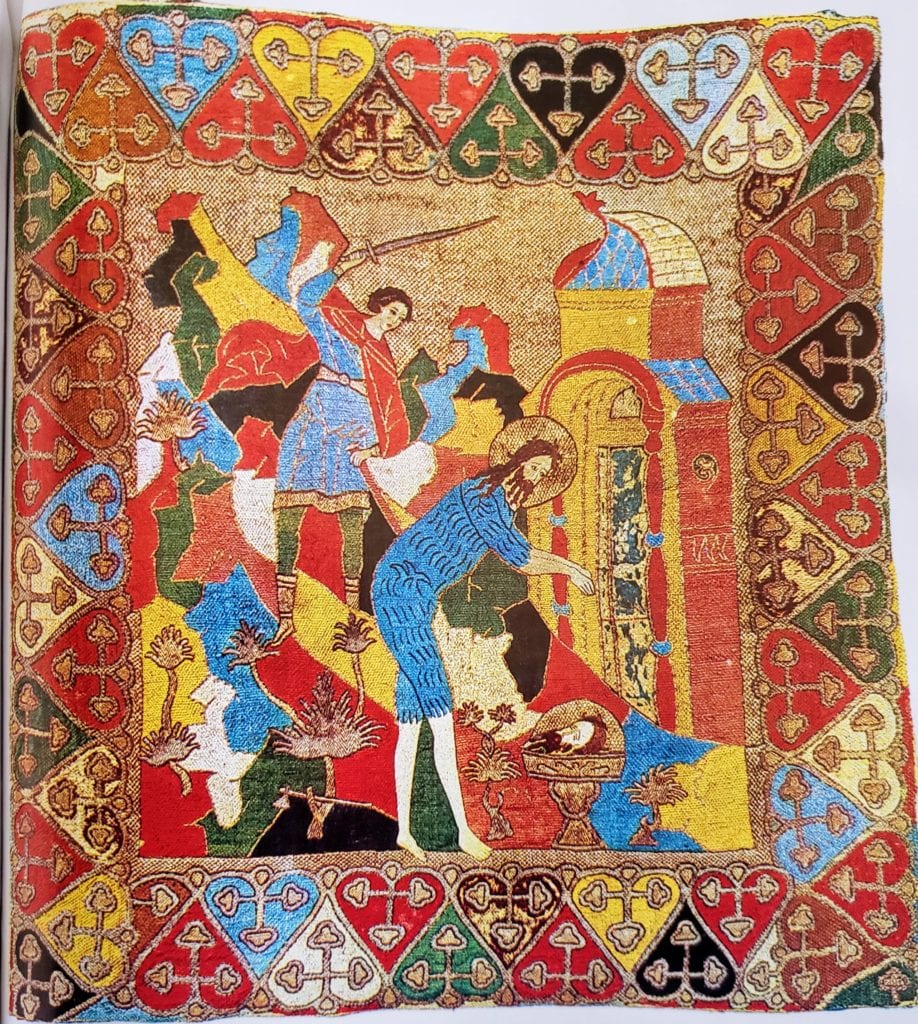

A podea from the late 15th-early 16th century embroidered in colored silk and depicting St. Catherine the Martyr with Scenes of her Life [Illustrations 22 and 23] is particularly picturesque. Prayers to Catherine were read at births and at “departures of the soul,”[81]For example, the dying Grand Prince Vasilij III appealed to her. (PSRL, Vol. VI, 1853, p. 273) but the design of this podea, based on its central inscription — “Catherine’s Prayer for the People” [«m[o]len[i]e styja ek[ate]riny o narode»] — goes beyond an individual prayer. This podea came from the Khutyn Monastery. It would appear that it was created in Novgorod. In the second half of the 15th century, Novgorod experienced a great shock – the loss of its independence. During the campaigns of the Prince of Moscow, the lands of Novgorod were “captured and burned, and the best people were beaten and struck down and devastated.”[82]Novgorodskie letopisi. St. Petersburg, 1879, p. 304.[83]jeb: By this time, Novgorod’s population had grown larger than it could support, and it became dependent on Vladimir to feed its people. The princes of Moscow used this dependence to gain control over its lands, and eventually Ivan III annexed the city to the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1478, disbanding the Veche and seizing the Hanseatic League goods stored there. It is possible that this podea was created during these dark days for the people of Novgorod.

Full of dignity in her royal garb, Catherine prays together with the people,[84]In this subject, it is more common for the people to be placed facing toward Catherine, praying to her (V.I. Antonova, N.E. Mneva. Katalog drevnerusskoj zhivopisi. Vol. 2, No. 443.). A depiction of the people similar to that in our podea, with them praying together the Catherine, is seen in a Novgorod icon from the mid-16th century (ibid., No. 361). as if not noticing the young executioner who draws a long sword from its sheath with some effort. The podea has several crowd scenes. Here almost everywhere is the crowd present, as if to emphasize the intention of this work. The hills are drawn in the Novgorod style, with square tops; the details of the clothing are meticulously embroidered in multicolored silks selected with great taste. Particularly fine is the final scene [Illustration 23], where Catherine’s humble pose, ready to receive death, is juxtaposed against the energetic movement of the executioner, who holds his sword above her.

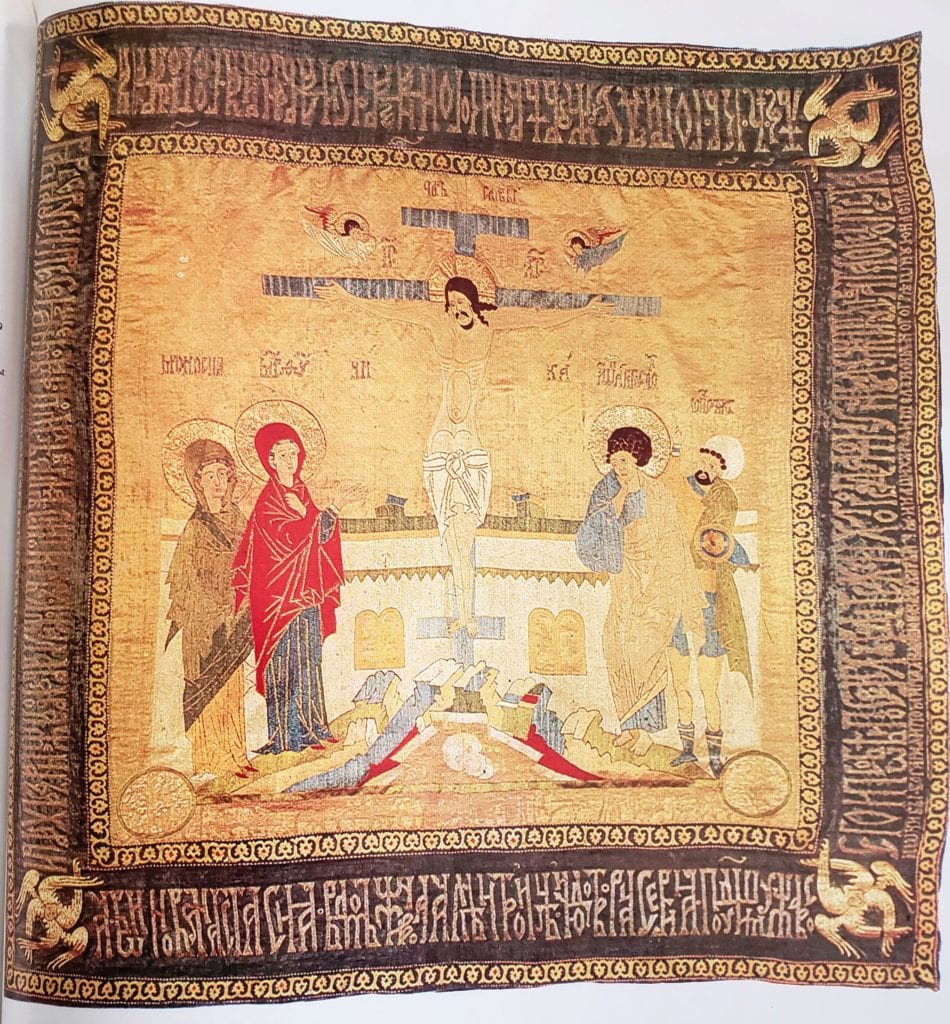

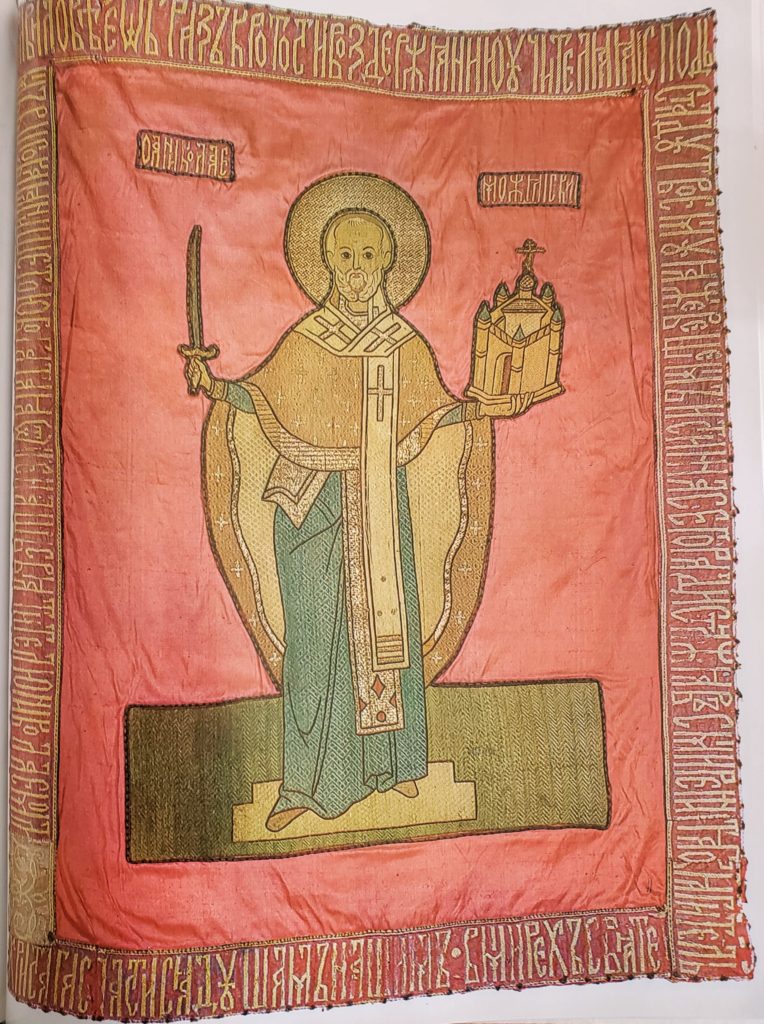

Illustration 24

Among the very small number of works of art to have survived to our time from the central Russian cities which were subjected to brutal ruin during the time of the invasion of the Tatars and of feudal strife during the times when they lost their independence, of particular value is the so-called “Rjazan'” Aër decorated with the Eucharist and scenes of the lives of Joachim, Anna and the Holy Mother [Illustrations 24, 25]. The Aër has an inscription about its creation in 1485 at the “conception” of Grand Princess Anna. The daughter of Moscow’s Grand Prince Vasilij Vasilievich the Blind, Anna was wed in 1464 to the Prince of Rjazan’ Vasilij, who had been raised in the Moscow court. After her husband’s death in 1483, she lived with her son Ivan in Pereslavl’-Rjazan’, and it was to the largest church of that city, the Cathedral of the Assumption, that she donated this work. It is likely that the selection of subject for this Aër, along the border of which is depicted the miraculous birth of a child to “desperate” parents, is tied to her son, Price of Rjazan’ Ivan Vasilievich, and his lack of children at that time.[85]This is attested by a conversation he had in 1496 with his younger brother, Feodor. (Sobranie gosudarstvennykh gramot i dogovorov [SGGD], Part 1. Moscow, 1813, No. 127, p. 32)

As has already been noted, V.N. Schepkin is of the opinion that the Rjazan’ Aër shares a proto-original with the Suzdal’ Aër by Ogrofena Konstantinova [Illustrations 10, 11]. They both have the same content and arrangement. And yet, this work is of a different time, and a different artisan created it. Although it repeats the general design of the Suzdal’ Aër, the artist here creates a different composition, embodying in it their own aesthetic ideals. He has positioned slightly differently the apostles who approach the throne, has shifted the ciboria, has turned them into a single building, has dropped the scene of the “Caress” of the child, has highlighted the “Bathing of the Child” into its own separate cell. Also, some of the scenes here are slightly different: “The Annunciation to Anne about Joachim’s Return,” “The Evangelism to Joachim,” “The Arrival” (the first steps) of the Blessed Virgin, the Prayer for the Rods, John the Evangelist, and others. The Rjazan’ artist also has a different rhythm for the construction of the composition, and different proportions for the figures. The apostles are depicted with large, stocky heads. They do not completely fit in the center of the work, and their feet reach down into the strip with the inscription. Around the border there are many figures standing vertically, and the crowns of the trees have acquired an elongated, pineapple-shaped form. Here, line and silhouette are less gently rounded and are a bit more sheer than on the Suzdal’ Aër, the faces of the apostles are more elongated, and their features are sharper. Embroidered following the direction of the design, they have slight shading in brown silk. The whites of their round eyes stand out sharply. On the clothing, the silk stitches are thicker than on the faces. Everything is embroidered in heavy split stitches. The folds and contours are outlined in gold. The trees have acquired a particular decoration, with trunks in gold, fruit in red and silver, and light green foliage. As is often seen, the center area is embroidered more meticulously than the border. It would appear that here, several artists worked under the direction of a local artist who was untouched by Muscovite art of the Dionysian period.

Works which came from the Moscow Kremlin workshops of Ivan III are extraordinarily diverse.