It has been a while since I posted or worked on a translation. But, after a recent event with the return to in-person activities post-Covid lockdown, I was inspired to do more research on men’s hats from the medieval Rus’ period. I came upon the article below, which gives a great overview of hats seen in various illustrative sources from the 13th-17th centuries, and discusses their evolution over that time period. I’m interested in making a new Rus’ hat for my persona, and this provides some great background information on how hats were fabricated and decorated, and what types of hats were appropriate to various classes in medieval Rus’ society. As is common in Russian scholarship, the “medieval” time period is extended to include the 17th century, up through the period of Petrine reforms. Unfortunately during those reforms in the early 17th century, most examples of pre-Westernization clothing were lost, so with the exception of ecclesiastic and a few royal hats, almost no physical examples survive, so illustrations from manuscripts, portraits, and illustrated essays written by Western observers of the Russian court are the only evidence we have in many cases.

Russian Men’s Headwear in the Second Half of the 13th – 17th Centuries and their Decoration

A translation of Жилина, Наталья Викторовна. «Мужской русский головной убор второй половины XIII-XVII в. и его украшение.» Вестник Тверского государственного университета. Серия: История 6 (2013), с. 3-29. / Zhilina, Natalia Viktorovna. “Muzhskoj russkij golovnoj ubor vtoroj poloviny XIII-XVII v. i ego ukrashenie.” Vestnik Tverskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seria: Istoria 6 (2013), pp. 3-29.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/74270677.pdf. ]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

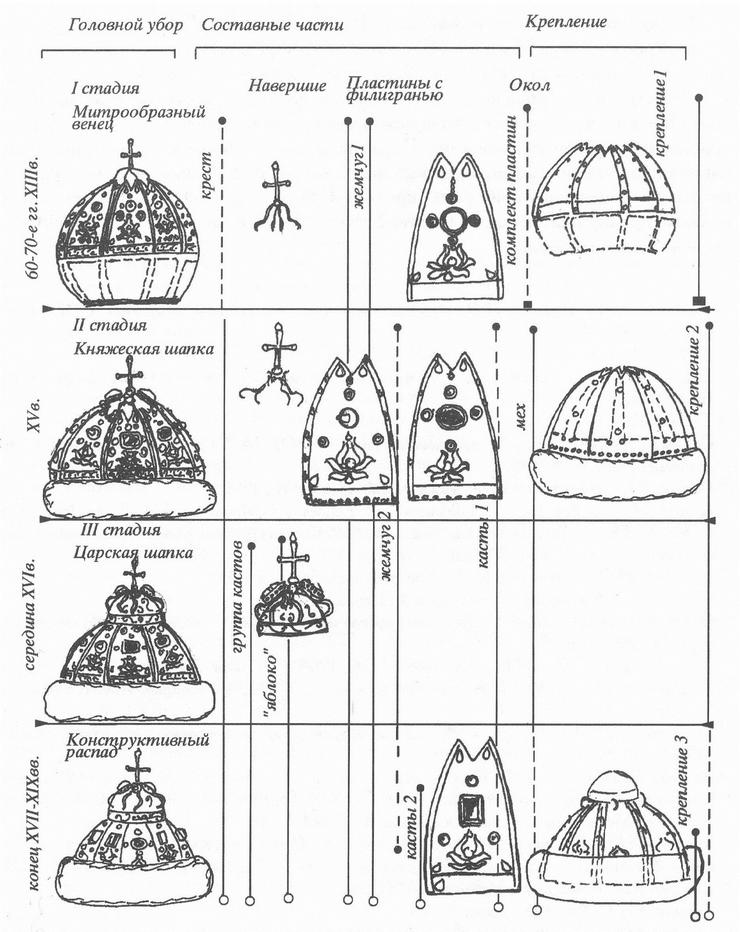

The purpose of this article is to organize illustrative sources according to the typology of men’s headwear, which is also considered to be a tier of costume decoration. This data is compared to physical items, which unfortunately are extremely few in number for the time period under review. By design, this work continues the study of women’s headwear from the same period.[1]Zhilina, N.V. “Tipologija zhenskogo golovnogo ubora s ukrashenijami vsoroj poloviny XIII-XVII v.” Zhenskaya traditsionnaja kul’tura i kostjum v epokhu Srednevekov’ja i Novoe vremja: mater. mezhdunar. nauch.-obrazov. seminara 9-10 nojabra 2012 g. Moscow-St. Petersburg, 2012. Issue 2, p. 53. This task is in line with the direction of research performed by O.V. Mareeva.[2]Mareeva, O.V. Kul’turno-istoricheskaja evoljutsija formy i simvoliki paradnykh golovnykh uborov russkikh gosudarej XII-XVII vv.: avtoref. dis. … kand. ist. nauk. Moscow, 1999. One chapter of a monograph about Monomakh’s Cap and thesis work is devoted to an analysis of men’s headwear.[3]Zhilina, N.V. Shapka Monomakha. Istoriko-kul’turnoe i tekhnologicheskoe issledovanie. Moscow, 2001, Chapter 4; –. “Russkij muzhskoj golovnoj ubor XIV-XVII vv.” Moda i dizajn: istoricheskij opyt. Novye tekhnologii. St. Petersburg, 2007.

Second Half of the 13th Through the 15th Centuries

In the 13th-14th centuries, in the post-Byzantine world and in Palaiologan Byzantium, a mitre-shaped type of imperial crown developed which widened over roughly the top third of its height.[4]Kul’tura Vizantii. XIII-pervaja polovina XV vv. Moscow, 1991, pp. 49, 55, 106; Beljaev, D.F. Byzantina Ocherki, materialy i zametki po vizantijskim drevnostjam: ezhednevnye i voskresnye priemy vizantijskikh tsarej i prazdnichnye vykhody ikh v khram sv. Sofii v IX-X vv. St. Petersburg, 1893, p. 286. The Cap of Monomakh in its original form (stage I), it seems, had this mitre-like form, analogous to the crowns of the Byzantine emperors. It can be compared with high probability to the “golden cap” mentioned in royal spiritual charters from 1339. The gold plates fastened to the fabric base through holes along their edges were an evolution of the plaques used in diadems, which by their originally curved shape would have given those caps a semispherical or mitre-like form. A fabric cap emerged from beneath the serrated upper edge of these plates, to which a cross was affixed upon a crosshair of arched supports, forming an additional tier which represented a stemma.[5]jeb: a type of crown worn in the late Roman, Byzantine and Bulgarian empires. Presumably, the bottom part of the headdress was connected into a narrow band to help the hat hold onto the head. This headwear was perceived as two-tiered, looking like a diadem or crown combined with a cap, and continued the line of development of Byzantine royal crowns and insignia (stemmas/tiaras).[6]Ribbon-type crowns were typically considered to be diadems, where the “ribbon” may consist of various types of medallions. A stemma was a type of headwear which included in its design a rigid hoop or, possibly, hoops which crossed at the top in order to affix the headwear to the head.

The first stage of the Cap of Monomakh was a crown of royal power.[7]Zhilina, op. cit., pp. 102-164. In the 14th-15th centuries, it would have been distinguished by a feature, thanks to which it subsequently became a prototype for royal hats – the presence of symbols of highest power, e.g. the crown’s points,[8]jeb: Rus. зубы, zuby, “teeth”. the cross on the imitation crosshairs, the four-part articulation (the 8 plates) corresponding to the equal number of perpendicular hoops on a stemma. In the 15th century, of course, there arose a new system of fastening the plates by their central and lower edges which secured the stemma-like structure of the headwear, and the top was accentuated with precious stones (stage II). The fur trim which appeared around this time, located below the plates, was derived from traditional Russian hats.[9]Here we are partially in agreement with M.G. Rabinovich, who judged that the Cap had been recreated as a Russian type of princely hat; however, in our opinion, it was based not on an Eastern skullcap, (jeb: Rus. тюбетейка, tjubetejka) but rather on a Byzantine crown-shaped coronet. cf. Rabinovich, M.G. “Odezhda russkikh XIII-XVII vv.” Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy. Moscow, 1986, p. 84. In the early 17th century, the French captain J. Margeret called this cap “the Royal Crown” and distinguished it from others by noting that it was with this crown specifically that “was once used to crown the Grand Princes.”[10]Margaret, J. Rossija nachala XVII v. Zapiski kapitana Marzhereta. Moscow, 1982, pp. 168-169.

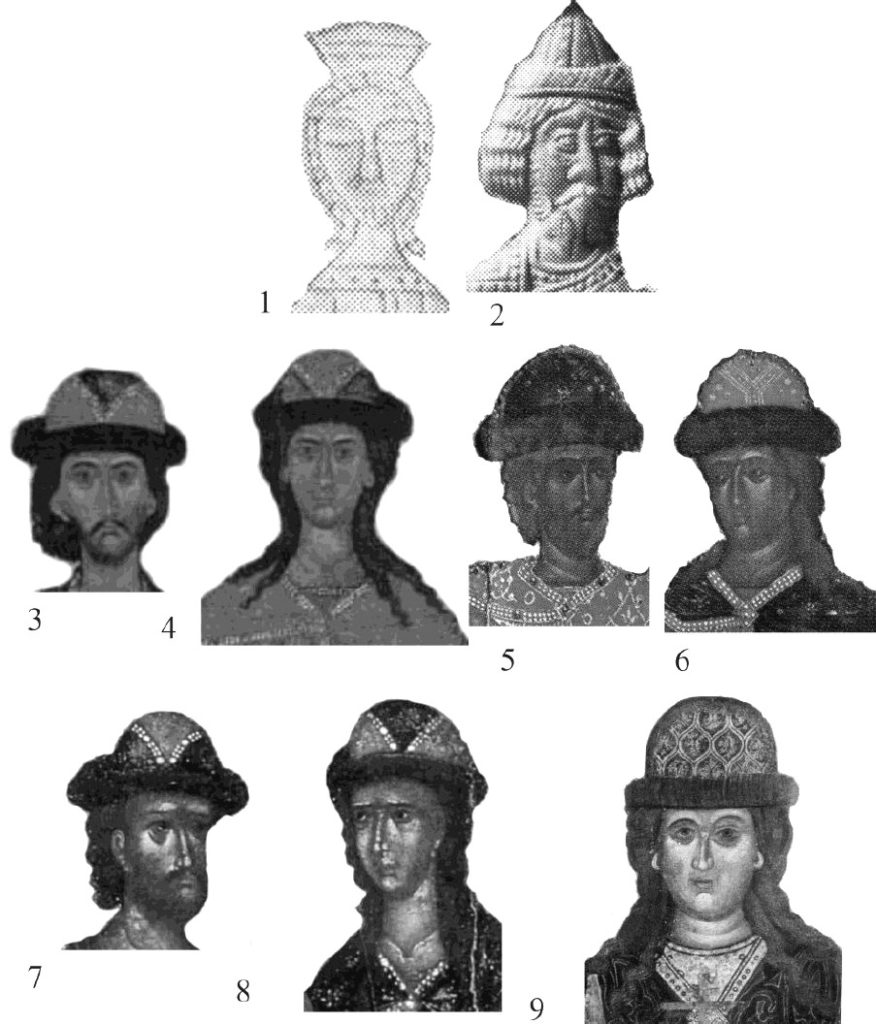

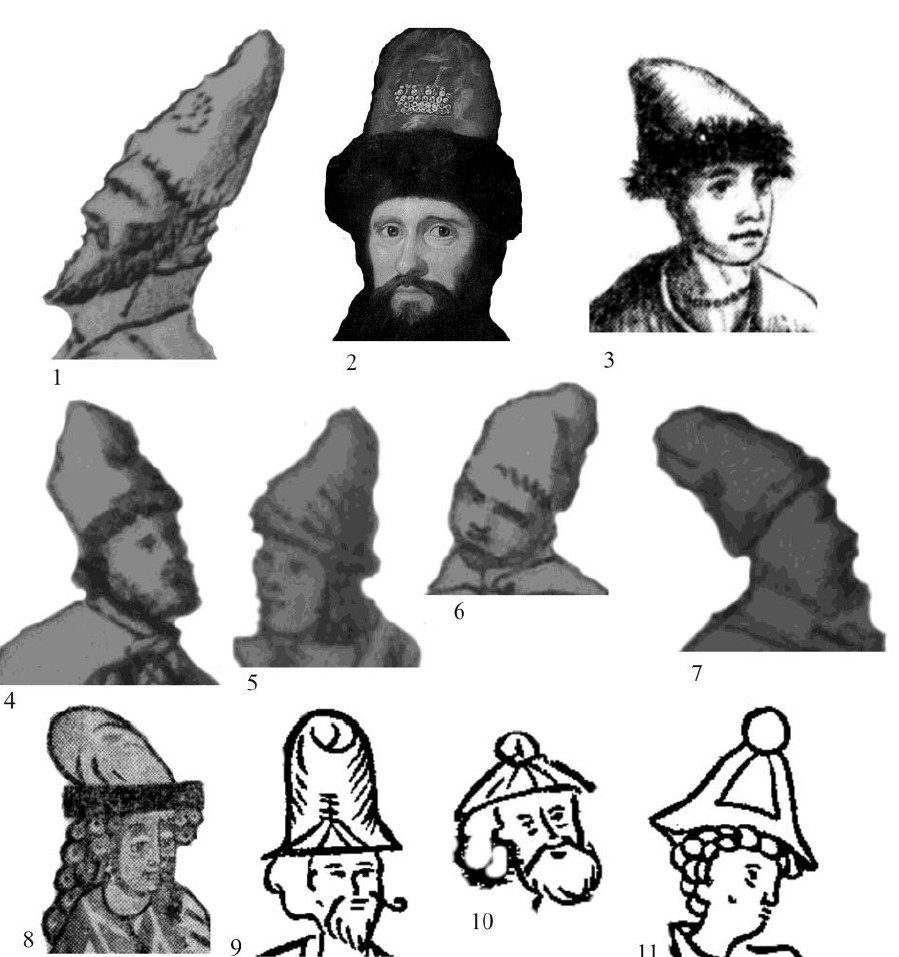

1 – crown or imperial coronet, widening and closed (pyramidal form, reliquary cross, late 13th-early 14th cent., Novgorod); 2 – wedge-shaped hat with trim, stone icon of Boris and Gleb, Solotchinsky Monastery, 13th cent.; 14th century icons of Boris and Gleb: 3, 4 – Pskov; 5, 6 – a church in Plotniki, Novgorod region; 7, 10 – State Tretyakovsky Gallery; 9 – village of Bolshoe Zagor’e, near Pskov.

For the 13th-14th century period, there are practically no depictions of pointed crowns, if we do not take into account that the Radziwiłł Manuscript miniatures may reflect this earlier time period. As the insignia of supreme power, we see an earlier form of imperial, pyramid-shaped crown, which is also known from the pre-Mongol era (illus. 1: 1). The crown of the Emperor Constantine on a Novgorodian reliquary cross has ryasna pendants, whereas in later times this type of pendants are not seen on men’s headwear.

Depictions of Russian princely headwear – hats with precious overlaid plates and trim from the second half of the 13th-15th centuries – are known from icons and the miniatures of the Radziwiłł Manuscript. During this period, the mitre-shaped cap became common. Typologically, Russian princely hats were related to the kolpak with trim, but differed from them in the stiffened, supported semispherical (or sometimes, conical or cylindrical) shape of the crown. This ceremonial, official wear was relatively dense and stiff.

On a stone icon of Boris and Gleb from the 13th century, we see depicted conical hats (from the front, we are able to make out 4 wedges, so there were likely 8 wedges in total), with precious stones running the length of these wedges. The trim is covered with diagonal lines, which are also shown on the lower borders of the clothing. This depicts either fur or beautiful striped fabric (illus. 1: 2). Changes in the mitre-like shape of this princely hat can be seen in the iconography of the princely Sts. Boris and Gleb in the 14th century (illus 1: 3-9).[11]Popov, G.V., Ryndina, A.V. Zhivopis’ i prikladnoe iskusstvo Tveri XIV-XVI veka. Moscow, 1979, p. 45.

The crowns of these caps are divided by arcs into segmented zones, as a rule, and moreover in different colors, variously for Boris and Gleb (illus. 1: 3, 4, 7, 8). Where the hats are shown as monochromatic, Boris and Gleb wear different colors (illus. 1: 5, 6). The zone outlines are also sometimes crumpled, and a rhombus is outlined on the crown, possibly a relic of the quadrangular shape of Byzantine headwear from the pre-Mongo period (illus. 1: 5, 6). The seams are emphasized by precious decorations – stones and plaques.

Illustrative sources from the 15th century are relatively richer than the preceding era, and they depict various types of men’s headwear.

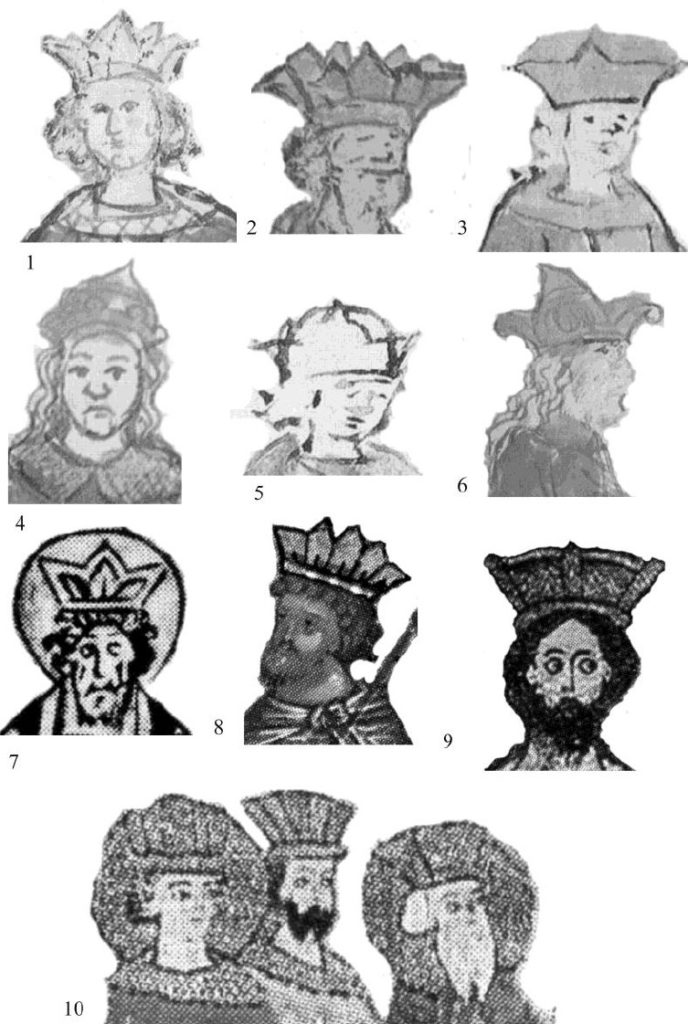

In miniatures from the Radziwiłł Manuscript: 1 – Emperor Heraklius (folio 5 rev.); 2 – Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus (folio 32); 3 – Prince Andrey Yur’evich Rostovsky (folio 203 rev.); 4 – Russian prince (David Svyatoslavich or Mstislav Vladimirovich) (folio 132); 5 – a Galician Volodimirovich prince (name not shown) (folio 196 rev. 2); 6 – Russian prince Svyatoslav Yaroslavich (folio 107.2)

From depictions on icons and works of applied art: 7 – Prince Mikhail of Chernigov, reliquary from the Tver’ region (last 3rd of the 15th century); 8 – the tsar’, from the icon The Seven Youths in the Fiery Furnace (late 15th cent., St. Sophia Cathedral, Novgorod); 9 – Jesus Christ on a podea of Sophia Palaiologos (late 15th cent.); 10 – the podea Church Procession (late 15th cent., State Historical Museum).

The miniatures from the Radziwiłł Manuscript, icons, and works of applied art reflect several forms of pointed crowns, and moreover, the crowns are shown on Russian princes in varying circumstances. Some of the depictions include only pointed circlets without a crown: 1) a crown with five points (illus. 2: 1-2; illus. 3, 8)[12]When referring to the miniatures of the Radziwiłł chronicle, the figure captions accompanying the illustrations indicate the folio number according to the publication Radzivillovskaja letopis. St. Petersburg-Moscow, 1994, vol. I. Each given link is not repeated for every occurrence. 2) a crown with three points (illus. 2: 3). Prince Mikhail of Chernigov is depicted wearing a crown with three points in an engraving (illus. 3: 7). The shape of the coronet is known as having three elongated, curving points, with a crown visible behind them (illus. 2: 6). There are also individual circlets with crowns. A semispherical crown but with a point (attached?) is shown significantly above the points, a circle of which runs around the lower edge of the headwear (illus. 2: 4). There are circlets with rounded, mitre-style crowns and a layer of semi-rectangular shaped points.[13]This type of crown, which has analogies in Western European material, is shown on the Russian prince Izjaslav, who had previously fled to the Poles and is seen returning to his homeland. cf. Radzivillovskaja letopis. Vol. 1, folio 101.2. There is also a tall two-layered, widening, crown-shaped hat.[14]This is depicted on Russian prince Vladimir Vsevolodovich (1094). Radzivillovskaja letopis. Vol. I, folio 129.2). We also see a continuation of the European-Byzantine tradition of depicting pyramidal crowns which are four-part in nature (illus. 2: 9). Works of liturgical embroidery depict closed headwear which transition from pyramidal to mitre-like in construction (illus. 3: 10).[15]jeb: sic. This appears to be a typo, and should refer to illus. 2: 10.

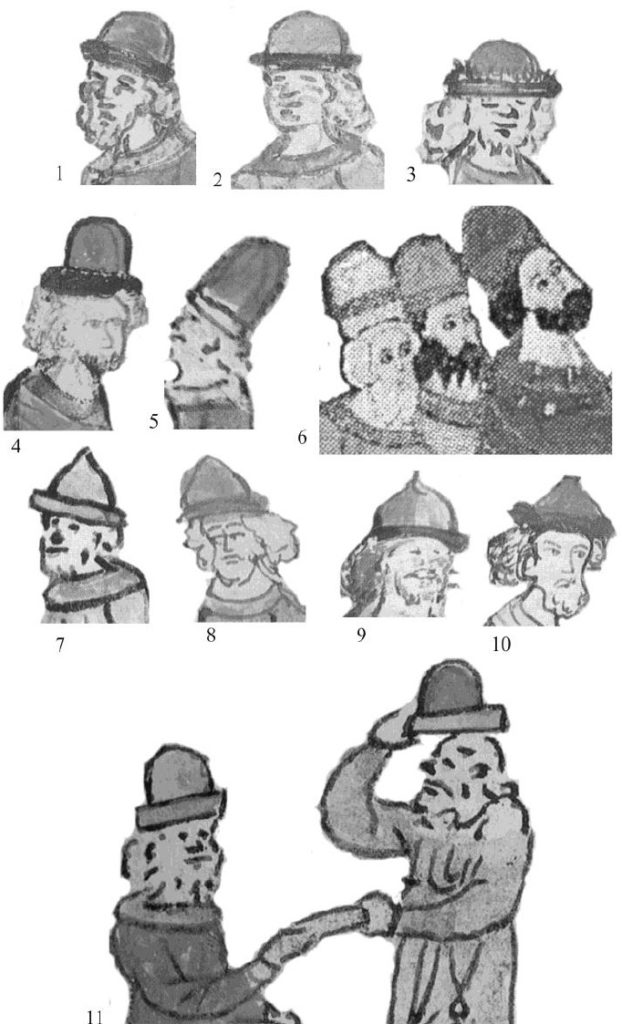

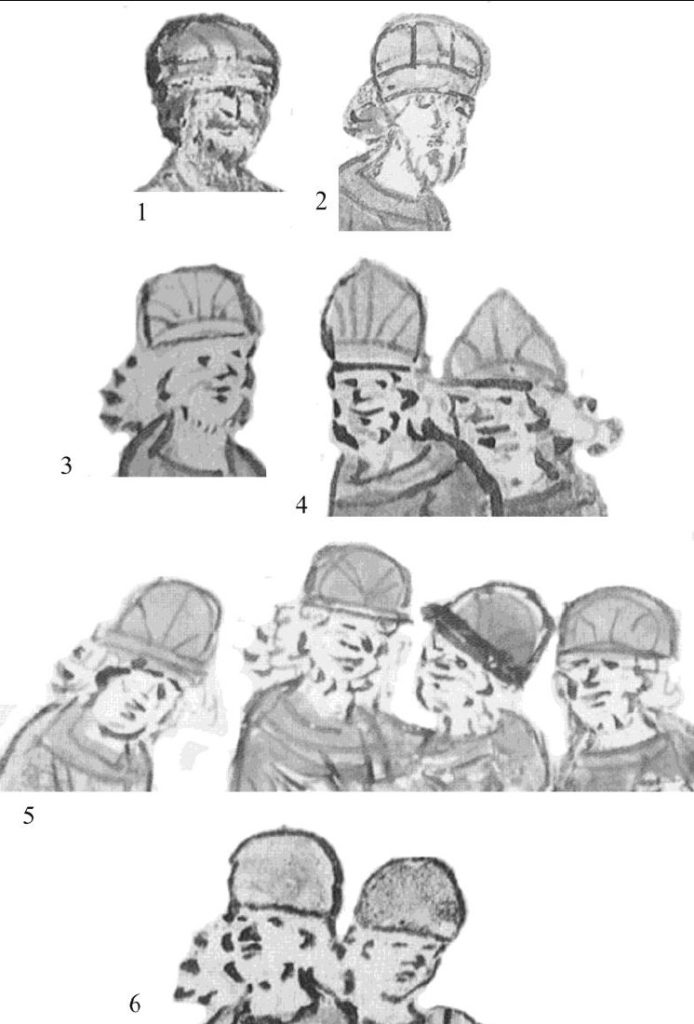

In miniatures from the Radziwiłł Manuscript: 1 – Slavic Prince Rostislav or Svyatopolk (folio 13); 2 – Russian Prince Svyatoslav (965) (folio 34); 3 – with clearly-visible fur trim, prince Vladimir Monomakh (1102) (folio 148 rev.)

tall hats: 4 – Russian prince receiving tribute (folio 5); 5 – Russian princes (folio 244); 7 – Russian Prince Roman Mstislavich of Galicia (1205) (folio 245 rev.); 8 – a Novgorodian member of Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich’s (1102) entourage (folio 148 rev.); 9 – sphero-conical form, member of Ugric King Heraclius’ entourage (folio 5 rev.); 10 – hat with earflaps, Slavic prince (folio 13 rev.)

semi-spherical with fabric revers: 11 – Prince Vsevolod Yur’evich, seated upon his throne, receives a warlord returning from his campaign against the Bolgars (1185) (folio 235); 6 – semi-spherical and sphero-conical hats with fur trim, the podea Church Procession (late 15th cent., State Historical Museum).

Semi-spherical caps with fur trim belonging to Slavic and Russian princes and members of their entourages are fairly well represented. The sources allow us to highlight several forms. The most commonly depicted is the mitre-shaped or semi-spherical form (illus. 3: 1-3, 6 left, 11). There are also taller hats which are nearly cylindrical with a semi-spherical top (illus. 3: 4-5). A sphero-conical form with a point at the top is also encountered (illus. 3: 6 right, 7-10). Alongside hats which are clearly shown with fur trim (illus. 3: 3), we also see hats with a cloth revers in a contrasting color (illus. 3: 7-8, 11). On hats with fur trim, we typically do not see any lines dividing the hat into multiple sections, except in isolated cases (illus. 4: 5, third from left).

Another category of mitre-shaped (semi-spherical or sphero-conical) hats is characterized by their lower rim, but as a rule do not have any trim or revers. These are typically shown in yellow, but their division into stripes has two types: a sectoral or cross-shaped division (illus. 4: 1-2), and a segmented division, sometimes with a single transverse stripe (illus. 4: 3-5). These hats belonged to the tsars and princes. Russian princes are most often shown in segmented headwear. There are hats of a simplified type, without revers, dyed in various colors (illus. 4, 6). The sectional division of the first type preserves the denotation of stemmas (and their division into four parts). The division into segmented zones of the second type originates, most likely, from the frontal positioning of a central brooch depicting a heavenly or earthly patron. The first variant symbolizes power, while the second symbolizes service. These headwear were more formal, and likely represented a form of princely insignia.

sectoral division: 1 – Slavic prince (folio 4 rev.); 2 – Bulgarian Tsar Mikhail (folio 13)

segmented division: 3 – Prince Oleg (1096) (folio 137); 4 – Russian Princes Andrey and Rostislav (folio 184); 5 – Russian princes Vladimir and Vsevolod (1144) (folio 174 rev.); 6 – hat without trim, Prince Vsevolod (folio 227 rev.2)

Sources also reflect headwear worn by wider circles of society. The most commonly seen headwear in the Radziwiłł Manuscript is a kind of soft kolpak with revers which has a frontal slit (illus. 5: 1-3). The podea Church Procession shows taller, pointed kolpaks which may be more expensive (illus. 5: 4). On the other hand, a conical, possibly knit commoner’s kolpak (illus. 5: 5) is much simpler. In some of these simple forms, no revers is visible, and the crown flops over decidedly (illus. 5: 6). We also see hats with wedge-shaped crowns (illus. 5: 7).

In addition to the typical Rus’ forms, we also encounter some unusual hats in the Radziwiłł Manuscript, some of which can be considered to be foreign, while others of unclear origin. A soft cap with a swollen, spherical shape with a tight lower band to hold it to the head belongs to a Byzantine commoner (illus. 5: 8).

In the Radziwiłł Manuscript miniatures, men’s headwear in the form of a turban is persistently encountered, worn by Slavic and Russian princes and urbanites (illus. 5: 9-10). The wearing of draped headwear, evidently, was a generally European fashion which may also have been common in Rus’. Relations with Lithuania may have contributed to this. It is known that such headwear was worn in Byzantium by women and some officials of the Byzantine court.[16]Dawson, T. “Propriety, Practicality and Pleasure: The Parameters of Women’s Dress in Byzantium, A.D. 1000-1200.” Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800-1200. London, 2006, pp. 44-48, plates 10-11; Radzivillovskaja letopis. Tekst, issledovanie, opisanie miniatjur. Vol. 2. St. Petersburg-Moscow, 1994, p. 290. It is possible that this contributed to its spread in Europe in the 14th-15th centuries.[17]Mertsalova, M.N. Kostjum raznykh vremen i narodov. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1993, pp. 190-191, 199, 234; illus. 175, 184, 219. Men’s draped headwear in the Radziwiłł Manuscript miniatures are decorated with tassels or vertically-standing egret feathers. On these turbans, the fastening strips or coils of fabric stand out. In some cases, the turbans become donut-shaped hats around the head, similar to the Italian balzo.[18]Mertsalova, op. cit., p. 302, illus. 297.

Also of interest are the elongated, curved kolpaks worn by the enemies of Rus’ in the broadest sense, specifically in some cases by the Polovtsians, but also by various people shown as liars (illus. 5: 11).[19]For Polovtsian kolpaks, see Radzivillovskaja letopis, vol. 1, folio 127 rev., 159 rev.2, 176.2; the kolpak worn by Prince Davyd as he tells a lie: idem., folio 145.2; the kolpaks of the lying Novgorodians: idem., folios 171 rev., 171 rev.2. The headwear of Russian military guards have distinctive elements in the form of tall frontal plattens or cockades (illus. 5: 12).

kolpaks with slanted revers: 1 – Russian man leading Polovtsian prisoners (folio 210 rev.); commoner riding a horse pulling the wagon carrying the corpse of Andrey Bogolyubsky (folio 216); 3 – a warrior guard of Vladimir Svyatoslavich (1184) (folio 228.2)

commoner’s kolpak: 5 – folio 227 rev.2

soft kolpak: 6 – folio 22

hat with a wedge-shaped crown: 7 – folio 193 rev.

soft spherical hat: 8 – Greek messenger carrying poisoned wine to Prince Oleg during his campaign against Constantinople (907) (folio 15 rev.);

turban: 9 – Svyatoslav, son of Princess Olga (folio 33 rev.); 10 – old Russian man placing Olga in her tomb (folio 33 rev.)

elongated kolpak: 11 – curvilinear, worn by a Polovtsian (folio 127 rev.); 12 – tall hats and gear worn by guards of the princely throne (folio 212); 4 – people at a ceremony, the podea Church Procession (late 15th cent., State Historical Museum).

16th Century

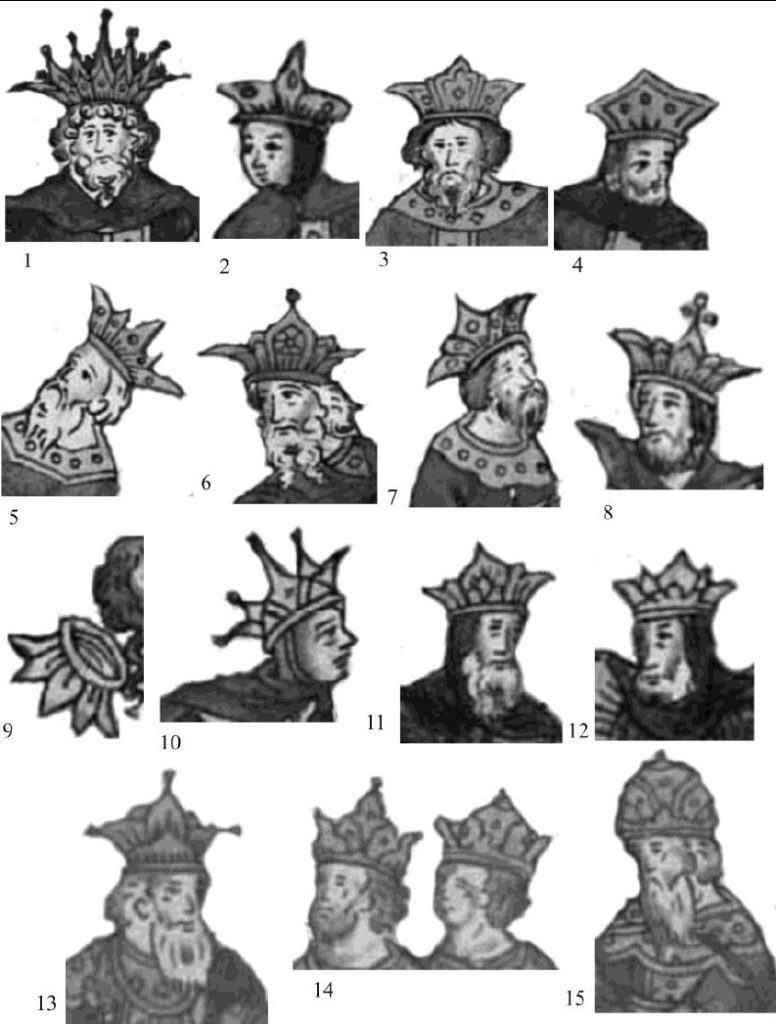

The Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible [20]jeb: Rus. Лицевой летописный свод, Litsevoj letopisnyj svod, lit. “Facial manuscript corpus”, a compilation of manuscripts commissioned by Ivan the Terrible for his royal library, containing 10 volumes and over 16,000 miniatures. from the 16th century contains the most varied forms of crowns, some of which are also known from 15th century material. They pertain to the kings of antiquity and the Byzantine emperors. Many of the crowns, as before, are without a cap and have tall points (type I). Among the men’s crowns, multi-pointed crowns with large numbers of points are relatively rare, as they are among women’s crowns (illus. 6: 1).[21]Litsevoj letopisnyj svod XVI veka. Vsemirnaja istorija, kniga 1. Moscow, 2010, p. 235. Crowns are most commonly shown with three (illus 6: 2-4)[22]idem., pp. 406, 279; Kn. 3, p. 734. and five points, viewed from the front (illus. 6: 5-8).[23]idem., Kn. 1, p. 308, 297, 323; Kn. 3, p. 593. The points may be shown with straight sides (illus. 6: 2, 5). In other cases, they are curved (illus. 6: 6-8). Crowns with curved points may be shown adorned with jewels and plaques. The central plaque is shown in the form of a kiotets[24]jeb: Rus. киотец, a plaque, typically enameled or carved and often showing an iconographic scene, used as a central decoration. (illus. 6: 6). The crowns are circular, as can be seen from repeated depictions of crowns falling from their wearer’s head or lying by themselves (illus. 6: 9).[25]idem. Kn. 1, pp. 408, 343. There are transitional variants where between the points we can see a cap, sometimes topped with a cross (illus. 6: 8, 11, 12).[26]Litsevoj letopisnyj svod XVI veka. Biblejskaja istorija. Moscow, 2010, Kn. 1, p. 318; Litsevoj letopisnyj svod XVI veka. Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 343. In other cases, we see a closed, angular, pyramidal or mitre-shaped form (illus. 6: 4).[27]idem. Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 408.

Museum Miscellany: 1 – folio 673; 2 – folio 759 rev.; 3 – folio 695; 4 – folio 760 rev.; 5 – folio 709 rev.; 6 – folio 704; 7 – folio 717; 8 – folio 727; 9 – folio 937 rev.; 10 – folio 779; 11, 12 – folio 772

Chronographic Miscellany: 13 – folio 815; 14 – folio 605 rev.; 15 – folio 610 rev.

On other crowns, the cap is more clearly seen, and in the majority of cases is mitre-like in form (illus. 6: 10).[28]idem. Kn. 1, pp. 445, 424, 431; Kn. 3, pp. 457, 38, 48. In details of crowns with caps (type II), the peaks are tall and spread to the sides with arced lines (illus. 6: 10, 13). In other cases, they lie more closely to the cap (illus. 6: 14). And, finally, there are some crowns seen with proportionally-tall, mitre-like caps and a lower row of sparse points (illus. 6: 15). Several variants of crowns are also known where a widening layer without points emerges from the lower edge; sometimes these have two such layers, and the headwear is divided into four sections.[29]idem. Kn. 3, pp. 436, 425; Kn. 1, p. 422. These different types and variants of crowns reflect the process by which caps became joined with layers of points. Not by chance, the mitre-like form became the caps for formalized Russian royal headwear.

The mitre-like form of headwear worn by Russian princes and the well-to-do, as in the 15th century, came in two basic types with respect to how the surface was divided. A similar phenomenon also is seen in women’s headwear.[30]Zhilina, Tipologija zhenskogo golovnogo ubora…, p. 53. Type I hats include those with perpendicular bands, of which one transverse band can be seen (illus. 7: 1).[31]Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 122. The second type (type II) includes those with segmented or curved partitions (illus. 7: 4-8).[32]idem., Kn. 1, pp. 308, 120, 293, 326, 343; Kn. 3, p. 160. But, it is also possible to make out several additional types which, of course, appear to be transitional. Type III hats differ in that their partitions are not arched, but rather are made up of broken lines (illus. 7: 2).[33]idem., Kn. 1, p. 352. In Type IV hats, the partitions are created by straight lines, with the individual parts of the cap reaching different heights (illus. 7: 3). A less commonly seen Type V is made up of hats without partitions (illus. 7: 14).[34]idem., Kn. 3, p. 155; Litsevoj letopisny svod…, Biblejskaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 509.

Museum Miscellany: 1 – folio 616 rev.; 2 – folio 731 rev.; 3 – folio 709 rev.; 4 – folio 615 rev.; 5, 6 – folio 702; 7 – folio 718 rev.; 8 – folio 727; 14 – folio 243 rev.;

Chronographic Miscellany: 9 – folio 677; 10 – folio 845; 11 – folio 900; 12 – folio 594 rev.; 13 – folio 598 rev.

Among the examples of Type II hats, we see quite a varied selection of forms and ornamentation. Judging from the illustrations, these princely caps had quite a lot of suspended (attached) or sewn-on decorations. Round figures are used to indicate precious stones (illus. 7: 4-8). A central, triangular plaque[35]jeb: Rus. дровница, drobnitsa. stands out on some images (illus. 7: 6-7).[36]idem. Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, p. 366. Even more interesting is the presence of a central plaque reminiscent of a figure with wings, possibly a depiction of an Archangel (illus. 7: 5). This is fully consistent with royal headwear; the Archangel Michael was patron saint of the princes. Among the crowns discussed above, there are also variants with curved divisions, where the points are shown as divergent, and where in the center we also see a depiction of the Archangel. These variants show that the tsar’s crowns evolved from princely headwear.

Some of the hats are topped off with a cross, which sometimes can be quite massive (illus. 7: 8). In other cases, they are shown quite formlessly (illus. 7: 9-11). This element of princely headwear in the miniatures is used in some cases to reflect the wearer’s pretention to supreme power. In a miniature showing the coronation of the Tsarevich Dmitry in 1498, the princely cap is reminiscent of the Cap of Monomakh.[37]Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, pp. 195-196, illus. 95.

As a rule, caps are shown with a thin rim running around the head. But, in some cases we also see a wider rim (illus. 7: 9, 13)[38]Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, pp. 181, 24. an expanding revers, double or triple revers, or a toothed brim[39]jeb: Rus. подзор, podzor, “valance”(?). (illus. 7: 12).[40]idem., pp. 366, 531. Some hats quite clearly show their fur trim (illus. 7: 10-11).[41]idem., pp. 627, 517, 53. In cases where a segmented division cannot be seen, the headwear looks quite similar to the Cap of Monomakh (illus. 7: 11). That is, these two categories of headwear – crowns and caps – were converging, reflecting the process of formation of the royal caps of the tsars.

Towards the mid 16th century, the Russian royal headwear, the Cap of Monomakh, was established. By this time, it had taken on the form which is now famous, having acquired its finial[42]jeb: Rus. навершие-яблоко, navershie-jabloko, lit. “pommel-apple”. and its fur trim. The general appearance of the Cap of Monomakh is reflected on the carved bas-reliefs on the Royal Thrones from 1551 in Uspensky Cathedral, but on one of the borders there still figures a princely segmented cap.[43]Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, pp. 191-194, illus. 92. The realities of the Cap of Monomakh partly coincide with the depictions of princely headwear in the miniatures from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible: the mitre-like shape, the absence of a false crown or points, and the presence of the finial. But, there are also differences: the Cap of Monomakh does not have curved partitions, but rather wedge-like structure also seen in Russian princely caps from the 13th century (illus. 1: 2). This difference is explained by the earlier dates of the Cap’s origin, and its conformity to the structure of that time period’s crowns of supreme power. This famous Russian insignia through this formation reflected the process of this earlier time (the merger of the Byzantine crown with the Russian princely cap). By the 16th century, it no longer quite fit the ongoing evolution of royal headwear based on the mitre-shaped cap and crown. In the Cap of Monomakh, the element of the crown was originally included in the main structure. In the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, the insignia of supreme power is depicted as a pointed crown with a cap (without fur trim). On the other hand, the Cap of Monomakh was a world model, one stage in the evolution of European crowns. The tradition of using it for coronations and the focus on its appearance consolidated in Russia not only the Russian tradition of princely hats, but also the global trend toward royal crowns with wedge-shaped or stemma-like structure, the crown of a New Age. It should also be noted that in this process there was no great difference from western variants of crowns, some of which also included fur trim.[44]Zhilina, N.V. “Put’ korony ot Drevnosti do Novogo vremeni.” Sacrum et profanum (V). Pamjat’ v vekakh: ot semejnoj relikvii k natsional’noj svjatyne. sb. nauch. tr. Sevastopol’. 2012, pp. 39-40, illus. 6: 5-9.

Of course, by 1553 the Cap of Monomakh had its finial, covering the pointed top of the plates. Since that time, plates have been common on real royal caps as a symbol of royal merit. On Ivan the Terrible’s Kazan Crown of 1553 there are two tiers of these plates with ornamental points at the top, appearing as if there were 2 crowns put on over the cap.[45]Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 82: 28. Practically every known royal cap from the 16th-17th centuries has this crown-like detail or related fragments. This false crown or points also complemented simpler royal headwear from this time, while the headwear of ordinary princes, as seen in miniatures, no longer included this feature by the 16th century. Pointed crowns had come to symbolize only the power of the Tsar (illus. 2: 7).[46]In the 15th century, Prince Mikhail of Chernigov was shown wearing a crown.

Golden sub-triangular plates went well with the wedge-shaped headwear or kolpaks which continued to exist in royal life. In 16th century portraits of Grand Prince Vasily Ivanovich and of Ivan the Terrible, similar caps were complimented by wearing an open crown over them. The most conspicuous example of this open crown is shown on the Nuremberg portrait of Ivan IV. Here, the crown has tall, narrow, and apparently thin pointed plates.[47]Rovinskij, D. Dostovernye portrety moskovskikh gosudarej. St. Petersburg, 1882, No. 10, 16; Zhilina, Shapka Monomaka…, illus. 82: 32-33.

Illustrations are known which depict the wedge-shaped fur hats worn by the late 15th-early 16th century rulers Vasily III and Ivan III.[48]Rovinsky, idem., No. 1; Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 82: 37. According to S. Herberstein, the kolpak worn by the ruler Vasily Ivanovich in order to demonstrate the Russian hunt was beautiful and impressive: “a white … kolpak (with revers), which had on both sides (where the revers were split) in front and in back expensive decorations made of gold, similar to necklaces, from which golden plates like feathers jutted upwards and (in time with his movements) bent and swayed up and down.”[49]Gerbershtejn, S. Zapiski o Moskovii. Moscow, 1988, pp. 82, 220; Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, p. 174. One might imagine that this “type of necklace” was analogous to the expensive “forged lace” plaque necklaces used in the 17th century used to decorate various edges of clothing, as well as on the revers of caps.[50]Medvedeva, G., Platonova, N., Postnikova-Loseva, M., Smorodinova, G., Troepol’skaja, N. Russkie juvelirnye ukrashenija 16-20 vekov iz sobranija Gosudarstvennogo ordena Lenina Istoricheskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1987, p. 24, No. 1-3. Based on this evidence, we can tell that exactly these kinds of plaques were used to fasten vertically-standing feather-like decorations, as are also well known from 17th century portraiture.

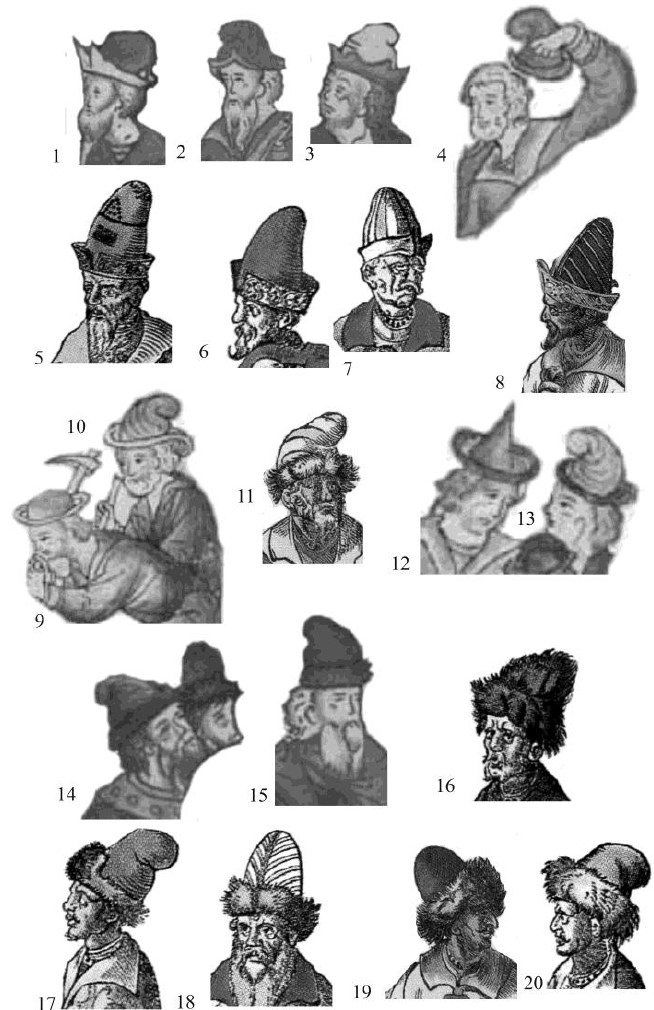

The Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible provides many depictions of relatively simple, soft, fabric kolpaks with revers. They are shown on people of varied social standing, and was the most characteristic of Russian headwear. The kolpak‘s revers had an opening in the front, and the edges of the revers protruded forward diagonally (illus. 8, 1-2).[51]Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, pp. 546, 16, 24. This protrusion was exaggerated in the image, but became an illustrative canon. A.V. Artsikhovskij dubbed this “oblique” (and its possible that this detail was indeed cut out along the bias).[52]Artsikhovskij, A.V. Drevnerusskie miniatury kak istoricheskij istochnik. Moscow, 1944, p. 101. The opening in the front sometimes had lacing.[53]Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, p. 71: 5. There are also examples with serrated revers (illus 8: 3).[54]Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, pp. 16, 24. The caps have a break – on the minatures this is depicted quite dramatically, sometimes with an almost spiral twist (illus. 8: 4, 10-11, 13).[55]idem. Biblejskaja istorija. Kn. 1, pp. 169, 397, 370, 381.

Just as in the Illustrated Chronicle, but significantly more beautifully and in greater detail, several kolpaks are depicted as worn by members of the Russian embassy to Austria in 1576 (illus. 8: 5-8). This colorful illustration depicts kolpaks decorated with pearls and jewels, their revers made from beautiful fabric, possibly cloth of gold (illus. 8: 5-6, 8).[56]Rovinskij, D. op. cit., nos. 19, 43; Russkaja narodnaja odezhda. Istoriko-etnograficheskie ocherki. Moscow, 2001. Illustration on the endpapers. Expensive kolpaks were tall and have less of a break (illus. 8: 5-6, 8). S. Herberstein notes that the kolpaks worn by the Russian elite at the reception of the ambassadors were decorated with pearls and various other jewels.[57]Gerbershtejn, op. cit., p. 212.

Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, 16th cent.: 1 – folio 876 rev.; 2 – folio 598 rev.; 3 – folio 594 rev.; 14 – folio 613 rev.; 15 – folio 602;

Museum Miscellany: 4 – folio 186; 9-11 – folio 172 rev.; 12-13 – folio 178;

Group Portrait of the Russian Embassy to Austria led by Z.I. Sugorsky (1576): 5-8, 11, 16-20.

Several basic types of cut are seen in the crowns of these kolpaks: 1) in two parts with one lengthwise seam, as can be seen from the angular join of the colorful stripes on the fabric (illus. 8: 8, 18); 2) wedge-shaped, made from multi-colored or monochromatic wedges (illus. 8: 7, 11). In some cases, the wedge-shaped kolpaks are strongly crumpled and appear to be almost spirally twisted, but it is possible that the seam in these cases is different, with the stripes arranged diagonally (illus. 8: 10, 11, 13).

The fabric crown of these caps was also combined with fur trim (illus. 8: 14-15, 17-20).[58]Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija, Kn. 3, pp. 54, 31. We know of kolpaks that were completely constructed from fur, such that the fur faced outwards; the trim in these cases appears to have been sewn on (illus. 8: 16). In other cases, just as on Russian fur coats, the crowns of these kolpaks remained bare (illus. 8: 20) or were decorated with precious fabric, velvet, or thick silk (illus. 8: 11, 17-19). The split in front was more typical for revers made of fabric; fur trim, as a rule, did not have a frontal split. In one case, we can see a seam or join on the front edge of the fur trim of an expensive kolpak (illus. 8: 18).

Other types of warm, winter hats were made almost entirely of fur. The voluminous, short ushanka or treukh made of fleece-like fur seen on two representatives of the embassy to Austria appears to be made entirely of fur (although it’s possible that the bare cap is just not visible) (illus. 9: 1). Another man is shown from the side, wearing a low, flat fur hat (illus. 9: 15). Similar low fur hats are also seen in the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible (illus. 9: 2). Sometimes, a short cap can be seen atop these fur hats (illus. 9: 24).[59]idem. Kn. 2, pp. 46, 50.

Group Portrait of the Russian Embassy to Austria led by Z.I. Sugorsky (1576): 1, 9, 10, 13-15;

Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, 16th cent., Museum Miscellany: 2 – folio 814 rev.; 3-4 – folio 816 rev.; 5-6 – folio 815;

Chronographic Miscellany: 7 – folio 598 rev.; 8 – folio 611; 11-12 – folio 595 rev.

Various sources also show mitre-like hats with broad fur trim (illus. 9: 5-12).[60]idem., p. 47; idem., Kn. 3, pp. 24, 49, 18. In the Illustrated Chronicle‘s miniatures, some hats have a segmented construction (illus. 9: 5-8, 12). In other sources, we can see that hats were sometimes sewn from striped fabric (illus. 9: 9-10). In some cases, the miniatures even depict men’s hats with brims (illus. 8: 9, 12).[61]idem., Biblejskaja istorija. Kn. 1, pp. 370, 381.

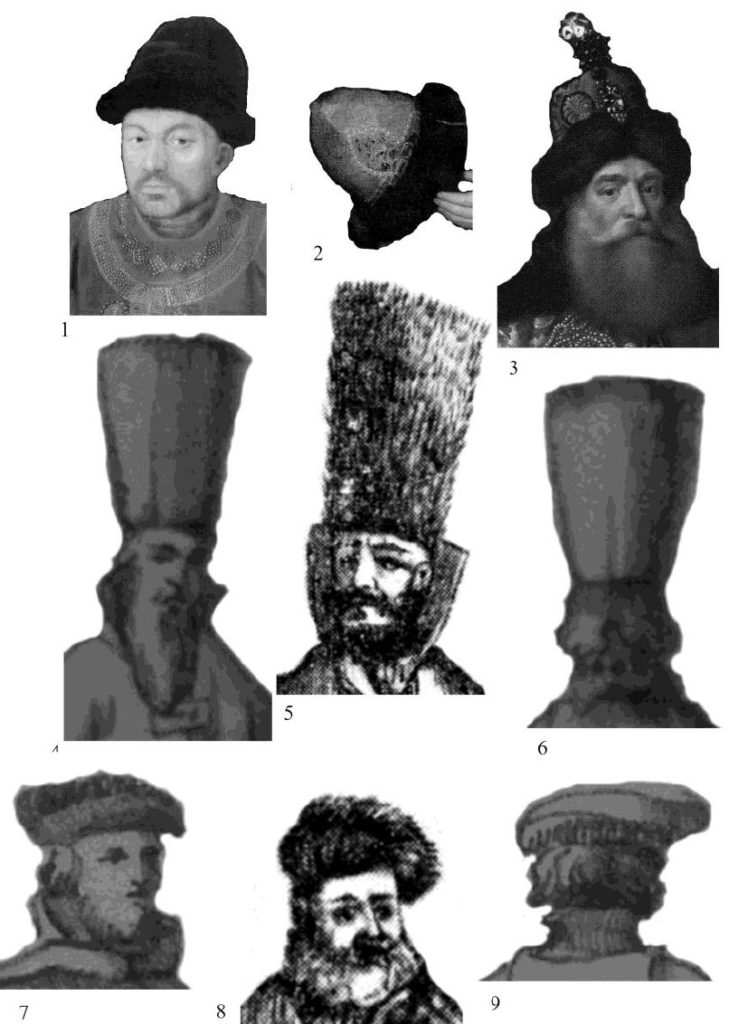

Tall, cylindrical fur hats are seen in two types: with the fur rolled to the inside (possibly called a murmolka[62]jeb: Rus. мурмолка, from Med. Russ. емурлукъ / emurluk, possibly from Turk. jağmurluk.) and with the fur on the outside (a “boyar hat” or gorlatnaja shapka[63]jeb: горлатная шапка, lit. “throat hat.” The origin of this name is said to be because they were made from the neck fur of sables, martens, foxes, etc.). The construction of the first type is easily visible on the drawing of the 1576 embassy: a fur “tube,” tapering toward the top, made from a single piece of fur with one longitudinal seam which did not reach all the way to the top. The top was not sewn closed, and where the upper edges of the hat came together, the top can be seen to be filled with the fur pile. This kind of hat may have been left bare, or covered [with fabric], judging by the blue color on one of them. The lower edge of the hat was slightly bent to allow it to fit better onto the head (illus. 9: 13-14). It is possible that this simpler and more archaic type of construction formed the basis of the more stately boyar hat.

17th Century

For the characterization of headwear for this century, there are both physical and illustrative materials which are in sufficient agreement that these sources allow one to characterize various societal strata.

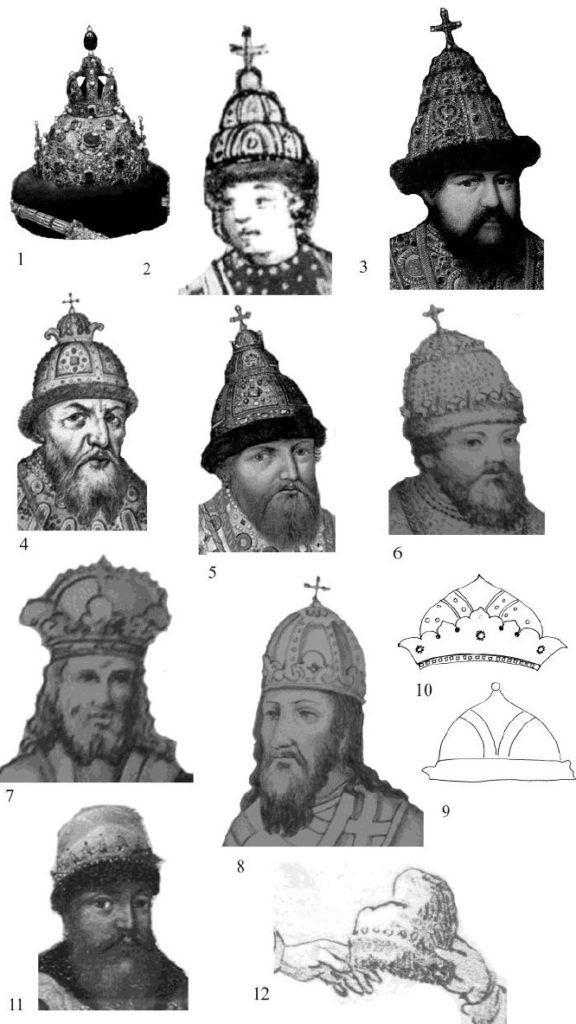

A crownlike detail or its symbol was essential on the headwear of royalty. Regarding this element, royal hats from the 17th century and their depictions agree with each other closely. It cannot be ruled out that the Cap of Monomakh may for some time have included additional crown-like details, which still has a large number of holes in its lower area that were used for fastenings. After the finial was added, the Cap of Monomakh came to be perceived as three-layered: a body made of plates, the finial, and the cross atop the crossed bands. Ivan the Terrible’s Kazan Cap has a semi-spherical finial.

It was this form and structure that was adopted by later royal headwear – most of all by the crown of the 17th century Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich, which was luxuriously decorated with enamelwork (illus. 10: 1). Mikhail Romanov is shown wearing this crown during his official coronation in 1613 (illus. 10: 2). On Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich’s crown from 1627, tall, overlaid, expensive plates in the form of ornamental points run along the lower border, as well as at the top near the cross. His satin crown also has four overlaid, expensive plates in the form of upwardly pointed “teeth”. Of course, in the early 17th century, the second tier on these royal crowns began to stand out more clearly as yet one more form of symbolic and decorative headwear.[64]Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 77-78. The second tier on Mikhail Fedorovich’s cap from 1627 is not continuous, as it was on earlier royal crowns. The bejeweled crown of Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich, depicted on his royal portrait,[65]jeb: Rus. парсуна, parsuna, a type of iconographic-style portrait popular in 16th-17th century Muscovy. consists of three practically-identical, tapering layers which do not have any individual, toothed plates (illus. 10: 3).

1 – crown of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich, 1627; 2 – Mikhail Fedorovich in a crown during his coronation in 1613 (miniature from the book Ob izbranii na tsarstvo velikogo gosudarja tsarja Mikhaila Fedorovicha, 1672/1763, lithograph 1856); 3 – Tsar Aleksej Mikhaijlovich in a crown in his royal portrait;

Crowns of the Russian Tsars in the Royal Titular, 1672: 4 – Ivan the Terrible; 5 – Aleksej Mikhajlovich;

Drawings from Meyerberg’s Album: 6 – Tsar Aleksej Mikhajlovich; 7 – Vladimir Svjatoslavich; 8 – Patriarch Nikon; 12 – the kolpak given to the tsar at the reception;

Other: 9 – hat worn by Prince Yurij Vsevologovich in an icon, 1645; 10 – hat worn by Prince Andrej Bogoljubskij in a fresco from the Archangel Cathedral, Moscow Kremlin, 1652-1656; 11 – crown worn by Mikhail Fedorovich in an equestrian portrait, 1670-1680s.

The Royal Titulary of 1672[66]The Bol’shaja gosudarstvennaja kniga, also called the Koren’ rossijskikh gosudarej or the Tsarskij tituljarnik, was compiled in 1672. shows two-tiered royal hats, where the lower layer is composed of plates, and the upper tier is a spherical finial. Between the upper and lower tiers, there is a crown-like belt whose “teeth” are shown either as a continuous valence, or as curved floral ornamental elements, as in the crown of Ivan the Terrible (illus. 10: 4).[67]Portrety, gerby i pechaty Bol’shoj gosudarstvennoj knigi 1672 g. Reprintnoe izdanie 1903 g. St. Petersburg, 2007, No. 26. Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich’s crown appears three-tiered, with a crown-like tier between the second and third tiers (illus. 10: 6).[68]idem., no. 32. Meyerberg’s album provides a depiction of Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich in 1662 in a two-tiered hat with two crown-like tiers at the base of each tier (illus. 10: 7).[69]Sobranie risunkov k puteshestviju Mejerberga. St. Petersburg, 1827, p. 57. According to this source, Patriarch Nikon’s headwear was very similar to that of the tsar. It was single-tiered, but with a crownlike layer below. This fully reflects Nikon’s high ambitions as they are known from history (illus. 10: 8).[70]idem., p. 59.

A tradition arose of depicting Vladimir the Great (died 1015) in a crown, but his crown differed from that worn by the tsars. In the Titulary from 1672, the other Russian rulers from the pre-Tsar period are depicted without headwear. In Meyerberg’s album, St. Vladimir is shown in a crown with a semi-spherical cap, two crossed arms, and a crown-like tier below (illus. 10: 7).[71]Sobranie…, p. 44.

The tsarevich Dmitry, who never became a true tsar, is shown dressed not in an official royal crown, but rather in a low princely hat with a pointed tier which symbolized his royalty.[72]Rovinskij, D. Materialy dlja russkoj ikonografii. St. Petersburg, 1890, Iss. 10. No. 361, 365, 367; Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 72. The headwear of the following princes also belonged to this type of princely hat with royal symbols: Yuriy Vsevolodovich (on an icon from 1645) and Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky (on a fresco from the Archangel Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin, 1652-1656) (illus. 10: 9, 10). These hats carry on the link of mitre-shaped, segmented princely hats. The crowns of rulers from the past were perceived as earlier, important insignia, but nevertheless were not considered equal to the contemporary royal crowns of the 16th-17th century.

The majority of hats in which Russian rulers and tsars are depicted in various everyday settings are typologically similar to kolpaks, similar to the 16th century, except with certain important additions which symbolized royalty or represented royal luxury. The expensive decorations of 17th century kolpaks fully continued the traditions of 16th century kolpaks. The military outfit of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich (second half of the 1670s-first half of the 1680s) includes a relatively stiff, light-colored hat with fur trim and a pointed layer, a false crown designating his royal position (illus. 10: 11). One of the drawings from A. Meyerberg’s collection shows the tsar at a ceremonial reception being presented with a soft kolpak decorated with a series of precious stones or plates around the upper edge of the revers “like a type of necklace”[73]Sobranie riskunkov…, p. 55. (illus 10: 12). This illustration is very reminiscent of Gerberstein’s aforementioned description of the white (hunting) kolpak owned by Grand Prince Vasily III. Written sources on expensive Russian kolpaks also mention “stones and pearls.”[74]Savvaitov, P. Opisanie starinnykh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, v azbuchnom porjadke raspolozhennoe. St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 45.

Drawings from Meyerberg’s Album: 1 – an expensive, decorated kolpak worn by an upper-class individual; 4 – a sotnik; 5 – a Boyar’s servant; 6 – a guest; 7 – a strelets;

A miniature from The Life of Anthony of Siysk, 1648: 9 – a peasant’s hat with a straightened revers and lacing; 10-11: knitted hats;

Other: 2 – the stol’nik I.I. Cheodanov, in a portrait by an unknown artist; 3 – a young Boyar, in a drawing from A. Olearius’s essay; 8 – a simple townsperson (a drawing from a bast box).

17th century kolpaks are subdivided by the form of their cap similarly to those from the 16th century. More expensive hats were tall and are shown, as a rule, uncrumpled in illustrations. They were ornamented with jewels and sewn-on imitation gemstones. According to their systems of ornamentation, the kolpak of a upper-class individual from one of Meyerberg’s illustrations was very similar to that in a portrait of the stol’nik[75]jeb: Rus: стольник, in Muscovite Rus’, a member of court one rank lower than a Boyar. I.I. Chemodanov. Chemodanov’s kolpak has sewn-on round plaques around 1 cm in diameter, forming ornamental figures (illus. 11: 1, 2).[76]Sobranie risunkov…, p. 40; Al’bom Mejerberga. Vidy i bytovye kartiny Rossii XVII veka. St. Petersburg, 1903, p. 25. Many hats are shown with fur trim (illus. 11: 3). The plainer hats worn by a sotnik,[77]jeb: Rus. сотник, a Cossack officer equivalent to a lieutenant. a Boyar’s servant, a guest, and a strelets[78]jeb: Rus. стрелец, literally “archer” or “shooter,” a soldier in a special permanent military squad in 16th-17th century Muscovite Rus’. appear squat, crumpled, and unadorned (illus. 11: 4-8).[79]Sobranie risunkov…, p. 32.

In addition to these kolpaks, semi-spherical or mitre-like hats which, most likely, were denser are also known. One very good illustration of this type of hat is a fur hat worn by Russian ambassador G.I. Mikulin from the early 17th century (illus. 12: 1). In the arms of a young Russian diplomat in the group portrait of the Russian embassy from 1662, we see a very expensive hat with an sewn-on decoration in the form of a wide, pointed leaf, the outline of which is decorated with pins, as well as with a series of precious, rectangular insets or a border of “forged lace” (illus. 12: 2). The most luxurious hat is that of Russian prince and diplomat P.I. Potemkin in a portrait from around 1700. It was made of expensive fabric, and has fur trim with an opening in the front; behind the fur there is fastened a tall inset “burdock” with a large number of jewels; on either side of it, there are fastened leaf-shaped decorations (either pinned or sewn on) (illus. 12: 3). We also have physical examples of these precious decorations: studs for a hat made by the workshops of the Moscow Kremlin in the 1620s have survived.[80]Sobranie risunkov…, p. 32.

Men’s winter fur hats are known from the illustrations to the travelogues by A. Olearius and A. Meyerberg. A cylindrical hat with fur on the outside, a so-called “boyar hat”[81]jeb: Rus. горлатка. widened toward the top and had a rounded bottom. We see these hats worn by princes, boyars, close associates of the tsar, and the tsar’s retinue at the most important of ceremonies (illus. 12: 4, 6). We also see this kind of hat worn by the head of a noble family during a trip to church for a wedding (illus. 12: 5). There are also short, flat hats made of fur, continuing the tradition of earlier short fur hats from the 16th century. These were similar to Western European berets. The fur “berets” are seen on merchants, nobles, and a person accompanying a boyar family (illus. 12: 7-9). This tradition was similar to that from Western Europe, but nevertheless appears Russian. This is yet one more instance of similarity in the evolution of costume, not necessarily a result of external influences.

The basic hat of the common folk was a soft, fabric kolpak with a revers, sometimes straightened downward, and with lacing (illus. 12: 9). The overall form is similar to felted hats with narrow brims known from later ethnographic material, the grechnevik;[82]jeb: Rus. гречневик, also гречишник, грешневик, гречник, гречушник, a tall cylindrical felted hat, sometimes with a narrow brim, made from brown sheep’s wool, commonly worn by peasants in the 18th and 19th centuries. it is possible that this analogy points to its evolution. Knitted hats with pompoms are also known, which also find parallels in ethnographic materials.[83]Artsikhovskij, drevnerusskie miniatjury…, p. 204, illus. 55. Kolpaks with straightened revers are shown worn by commoners in Meyerberg’s album.[84]Sobranie risunkov…, p. 9.

1 – Russian ambassador G.I. Mikulin (early 17th cent.); 2 – hat held by a Russian diplomat (group portrait of a Russian embassy, 1662); 3 – stol’nik P.I. Potemkim (portrait, c. 1700); 4, 6 – fur boyar hats from the Meyerberg Album; 5 – boyar hat from an illustration to A. Olearius’s essay; 7, 9 – flat fur caps worn by a merchant and a nobleman from the Meyerberg Album; 8 – a flat fur hat from an illustration to A. Olearius’s essay.

In the following time period, the boyar hat and kolpak faded into the past, and were not even preserved in folk costume. Forthcoming changes in hats tended toward the stiff and the flat, and a combination of fabric and stiffened materials. These tendencies appeared earlier in Western European costume, but in Russia, their implementation was accelerated by the reforms of Peter I. But, the treukh[85]jeb: Rus. треух, a type of hat similar to the ushanka, with earflaps and a lowered back panel over the neck. and malakhay[86]jeb: Rus. малахай, another fur hat similar to an ushanka worn by peasants. were preserved in ethnographic costume, as they worked well for the “national” Russian winter.

Conclusion

In princely men’s hats from the second half of the 13th century onward, the mitre-like form became established, as can be seen from various kinds of mitre-shaped, semispherical princely hats with fur trim and revers, while at the same time, the caps had both segmented construction of the surface and a wedge-shaped structure. The nobility of the 16th century, including princes, wore mitre-shaped hats with a segmented surface without crown-like elements, but with pinned on, inset, or sewn-on decorations, as well as precious stones. An image of the Archangel developed on the central plaque as a symbol of service. A finial was depicted on princely hats in miniatures to reflect cases of pretention to higher power.

As such, the evolution of princely and men’s hats in general can be summarized as follows. In the 13th-14th century Rus’, illustrations of pointed crowns are practically unknown, although initial stages of these pointed crowns are represented by the kiotets-style plaques from a 12th century pointed crown which were later reused for the cover of the 16th century Mstislav Gospel. In the West at the same time, the pointed form of crown became established, based on the kiotets-style plaques used on Byzantine crowns.[87]Zhilina, Put’ korony…, illus. 5. It appears that the evolution of princely headwear was suspended following the Mongol Invasion. In 15th century Rus’, crowns of various forms were known: with tall points and a mitre-like cap, and princes are depicted wearing pointed crowns. Russan royal headwear solidified toward the middle of the 16th century in the Cap of Monomakh. In men’s crowns seen in miniatures from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, the mitre-like cap can be seen more clearly, and is surrounded by a low tier of a fewer number of points. As a whole, illustrated sources reflect the development of combining caps and pointed crowns in Russian royal hats. In parallel, the use of a finial developed, forming a second tier on these hats.[88]Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 81-83.

Both princes and lesser nobles had characteristic hats in the form of a kolpak with a revers. Expensive sovereign and royal kolpaks are known, as well as kolpaks and flatter hats worn by the Russian well-to-do. Along the revers, these were decorated with a border of sewn-on plaques (“forged lace”), and behind the revers or behind this border, they were reinforced with tall decorations on pins (“burdocks”). These decorations used pearls, stones, and small sewn-on plagues arranged into ornamental shapes. The revers of these kolpaks were made from beautiful fabric or cloth of gold.

Bibliography

- Dawson, T. “Propriety, Practicality and Pleasure: the Parameters of Women’s Dress in Byzantium, A.D. 1000-1200.” Byzantine Woman: Varieties of Experience 800-1200. London, 2006.

- Artsikhovskij, A.V. Drevnerusskie miniatjury kak istoricheskij istochnik. Moscow, 1944.

- Beljaev, D.F. Byzantina: Ocherki, materialy i zametki po vizantijskim drevnostjam: ezhednevnye i voskresnye priemy vizantijskikh tsarej i prazdnichnye vykhody ikh v khram sv. Sofii v IX-X vv. St. Petersburg, 1893.

- Zhilina, N.V. “Russkij muzhskoj golovnoj ubor XIV-XVII vv.” Moda i dizajn: istoricheskij opyt. Novye tekhnologii. St. Petersburg, 2007.

- Zhilina, N.V. “Tipologija zhenskogo golovnogo ubora s ukrashenijami vtoroj poloviny XIII-XVII v.” Zhenskaja traditsionnaja kul’tura i kostjum v epokhu Srednevekov’ja i Novoe vremja: mater. mezhdunar. nauch.-obrazov. seminara 9-10 nojabrja 2012 g. Moscow, St. Petersburg, 2012. Iss. 2.

- Zhilina, N.V. Shapka Monomakha. Istoriko-kul’turnoe i technologicheskoe issledovanie. Moscow, 2001.

- Zhilina, N.V. “Put’ korony ot Drevnosti do Novogo vremeni.” Sacrum et profanum (V). Pamjat’ v vekhakh: ot semejnoj relikvii k natsional’noj svjatyne sb. nauch. tr. Sevastopol, 2012.

- Martynova, N.V. Moskovskaja emal’ XV-XVII vekov: katalog. Moscow, 2002.

- Medvedeva, G., Platonova, N., Postnikova-Loseva, M., Smorodinova, G., Troepol’skaja, N. Russkie juvelirnye ukrashenija 16-20 vekov iz sobranija Gosudarstvennogo ordena Lenina Istoricheskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1987.

- Mertsalova, M.N. Kostjum raznykh vremen i narodov. Moscow, 1993, Vol. 1.

- Popov, G.V., Ryndyna, A.V. Zhivopis’ i prikladnoe iskusstvo Tveri XIV-XVI veka. Moscow, 1979.

- Rabinovich, M.G. “Odezhda russkikh XIII-XVII vv.” Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy. Moscow, 1986.

- Savvaitov, P. Opisanie starinnykh utvarej, odezdh, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, v azbuchnom porjadke raspolozhennoe. St. Petersburg, 1896.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Zhilina, N.V. “Tipologija zhenskogo golovnogo ubora s ukrashenijami vsoroj poloviny XIII-XVII v.” Zhenskaya traditsionnaja kul’tura i kostjum v epokhu Srednevekov’ja i Novoe vremja: mater. mezhdunar. nauch.-obrazov. seminara 9-10 nojabra 2012 g. Moscow-St. Petersburg, 2012. Issue 2, p. 53. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Mareeva, O.V. Kul’turno-istoricheskaja evoljutsija formy i simvoliki paradnykh golovnykh uborov russkikh gosudarej XII-XVII vv.: avtoref. dis. … kand. ist. nauk. Moscow, 1999. |

| ↟3 | Zhilina, N.V. Shapka Monomakha. Istoriko-kul’turnoe i tekhnologicheskoe issledovanie. Moscow, 2001, Chapter 4; –. “Russkij muzhskoj golovnoj ubor XIV-XVII vv.” Moda i dizajn: istoricheskij opyt. Novye tekhnologii. St. Petersburg, 2007. |

| ↟4 | Kul’tura Vizantii. XIII-pervaja polovina XV vv. Moscow, 1991, pp. 49, 55, 106; Beljaev, D.F. Byzantina Ocherki, materialy i zametki po vizantijskim drevnostjam: ezhednevnye i voskresnye priemy vizantijskikh tsarej i prazdnichnye vykhody ikh v khram sv. Sofii v IX-X vv. St. Petersburg, 1893, p. 286. |

| ↟5 | jeb: a type of crown worn in the late Roman, Byzantine and Bulgarian empires. |

| ↟6 | Ribbon-type crowns were typically considered to be diadems, where the “ribbon” may consist of various types of medallions. A stemma was a type of headwear which included in its design a rigid hoop or, possibly, hoops which crossed at the top in order to affix the headwear to the head. |

| ↟7 | Zhilina, op. cit., pp. 102-164. |

| ↟8 | jeb: Rus. зубы, zuby, “teeth”. |

| ↟9 | Here we are partially in agreement with M.G. Rabinovich, who judged that the Cap had been recreated as a Russian type of princely hat; however, in our opinion, it was based not on an Eastern skullcap, (jeb: Rus. тюбетейка, tjubetejka) but rather on a Byzantine crown-shaped coronet. cf. Rabinovich, M.G. “Odezhda russkikh XIII-XVII vv.” Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy. Moscow, 1986, p. 84. |

| ↟10 | Margaret, J. Rossija nachala XVII v. Zapiski kapitana Marzhereta. Moscow, 1982, pp. 168-169. |

| ↟11 | Popov, G.V., Ryndina, A.V. Zhivopis’ i prikladnoe iskusstvo Tveri XIV-XVI veka. Moscow, 1979, p. 45. |

| ↟12 | When referring to the miniatures of the Radziwiłł chronicle, the figure captions accompanying the illustrations indicate the folio number according to the publication Radzivillovskaja letopis. St. Petersburg-Moscow, 1994, vol. I. Each given link is not repeated for every occurrence. |

| ↟13 | This type of crown, which has analogies in Western European material, is shown on the Russian prince Izjaslav, who had previously fled to the Poles and is seen returning to his homeland. cf. Radzivillovskaja letopis. Vol. 1, folio 101.2. |

| ↟14 | This is depicted on Russian prince Vladimir Vsevolodovich (1094). Radzivillovskaja letopis. Vol. I, folio 129.2). |

| ↟15 | jeb: sic. This appears to be a typo, and should refer to illus. 2: 10. |

| ↟16 | Dawson, T. “Propriety, Practicality and Pleasure: The Parameters of Women’s Dress in Byzantium, A.D. 1000-1200.” Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800-1200. London, 2006, pp. 44-48, plates 10-11; Radzivillovskaja letopis. Tekst, issledovanie, opisanie miniatjur. Vol. 2. St. Petersburg-Moscow, 1994, p. 290. |

| ↟17 | Mertsalova, M.N. Kostjum raznykh vremen i narodov. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1993, pp. 190-191, 199, 234; illus. 175, 184, 219. |

| ↟18 | Mertsalova, op. cit., p. 302, illus. 297. |

| ↟19 | For Polovtsian kolpaks, see Radzivillovskaja letopis, vol. 1, folio 127 rev., 159 rev.2, 176.2; the kolpak worn by Prince Davyd as he tells a lie: idem., folio 145.2; the kolpaks of the lying Novgorodians: idem., folios 171 rev., 171 rev.2. |

| ↟20 | jeb: Rus. Лицевой летописный свод, Litsevoj letopisnyj svod, lit. “Facial manuscript corpus”, a compilation of manuscripts commissioned by Ivan the Terrible for his royal library, containing 10 volumes and over 16,000 miniatures. |

| ↟21 | Litsevoj letopisnyj svod XVI veka. Vsemirnaja istorija, kniga 1. Moscow, 2010, p. 235. |

| ↟22 | idem., pp. 406, 279; Kn. 3, p. 734. |

| ↟23 | idem., Kn. 1, p. 308, 297, 323; Kn. 3, p. 593. |

| ↟24 | jeb: Rus. киотец, a plaque, typically enameled or carved and often showing an iconographic scene, used as a central decoration. |

| ↟25 | idem. Kn. 1, pp. 408, 343. |

| ↟26 | Litsevoj letopisnyj svod XVI veka. Biblejskaja istorija. Moscow, 2010, Kn. 1, p. 318; Litsevoj letopisnyj svod XVI veka. Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 343. |

| ↟27 | idem. Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 408. |

| ↟28 | idem. Kn. 1, pp. 445, 424, 431; Kn. 3, pp. 457, 38, 48. |

| ↟29 | idem. Kn. 3, pp. 436, 425; Kn. 1, p. 422. |

| ↟30 | Zhilina, Tipologija zhenskogo golovnogo ubora…, p. 53. |

| ↟31 | Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 122. |

| ↟32 | idem., Kn. 1, pp. 308, 120, 293, 326, 343; Kn. 3, p. 160. |

| ↟33 | idem., Kn. 1, p. 352. |

| ↟34 | idem., Kn. 3, p. 155; Litsevoj letopisny svod…, Biblejskaja istorija. Kn. 1, p. 509. |

| ↟35 | jeb: Rus. дровница, drobnitsa. |

| ↟36 | idem. Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, p. 366. |

| ↟37 | Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, pp. 195-196, illus. 95. |

| ↟38 | Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, pp. 181, 24. |

| ↟39 | jeb: Rus. подзор, podzor, “valance”(?). |

| ↟40 | idem., pp. 366, 531. |

| ↟41 | idem., pp. 627, 517, 53. |

| ↟42 | jeb: Rus. навершие-яблоко, navershie-jabloko, lit. “pommel-apple”. |

| ↟43 | Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, pp. 191-194, illus. 92. |

| ↟44 | Zhilina, N.V. “Put’ korony ot Drevnosti do Novogo vremeni.” Sacrum et profanum (V). Pamjat’ v vekakh: ot semejnoj relikvii k natsional’noj svjatyne. sb. nauch. tr. Sevastopol’. 2012, pp. 39-40, illus. 6: 5-9. |

| ↟45 | Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 82: 28. |

| ↟46 | In the 15th century, Prince Mikhail of Chernigov was shown wearing a crown. |

| ↟47 | Rovinskij, D. Dostovernye portrety moskovskikh gosudarej. St. Petersburg, 1882, No. 10, 16; Zhilina, Shapka Monomaka…, illus. 82: 32-33. |

| ↟48 | Rovinsky, idem., No. 1; Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 82: 37. |

| ↟49 | Gerbershtejn, S. Zapiski o Moskovii. Moscow, 1988, pp. 82, 220; Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, p. 174. |

| ↟50 | Medvedeva, G., Platonova, N., Postnikova-Loseva, M., Smorodinova, G., Troepol’skaja, N. Russkie juvelirnye ukrashenija 16-20 vekov iz sobranija Gosudarstvennogo ordena Lenina Istoricheskogo muzeja. Moscow, 1987, p. 24, No. 1-3. |

| ↟51 | Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, pp. 546, 16, 24. |

| ↟52 | Artsikhovskij, A.V. Drevnerusskie miniatury kak istoricheskij istochnik. Moscow, 1944, p. 101. |

| ↟53 | Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, p. 71: 5. |

| ↟54 | Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija. Kn. 3, pp. 16, 24. |

| ↟55 | idem. Biblejskaja istorija. Kn. 1, pp. 169, 397, 370, 381. |

| ↟56 | Rovinskij, D. op. cit., nos. 19, 43; Russkaja narodnaja odezhda. Istoriko-etnograficheskie ocherki. Moscow, 2001. Illustration on the endpapers. |

| ↟57 | Gerbershtejn, op. cit., p. 212. |

| ↟58 | Litsevoj letopisnyj svod…, Vsemirnaja istorija, Kn. 3, pp. 54, 31. |

| ↟59 | idem. Kn. 2, pp. 46, 50. |

| ↟60 | idem., p. 47; idem., Kn. 3, pp. 24, 49, 18. |

| ↟61 | idem., Biblejskaja istorija. Kn. 1, pp. 370, 381. |

| ↟62 | jeb: Rus. мурмолка, from Med. Russ. емурлукъ / emurluk, possibly from Turk. jağmurluk. |

| ↟63 | jeb: горлатная шапка, lit. “throat hat.” The origin of this name is said to be because they were made from the neck fur of sables, martens, foxes, etc. |

| ↟64 | Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 77-78. |

| ↟65 | jeb: Rus. парсуна, parsuna, a type of iconographic-style portrait popular in 16th-17th century Muscovy. |

| ↟66 | The Bol’shaja gosudarstvennaja kniga, also called the Koren’ rossijskikh gosudarej or the Tsarskij tituljarnik, was compiled in 1672. |

| ↟67 | Portrety, gerby i pechaty Bol’shoj gosudarstvennoj knigi 1672 g. Reprintnoe izdanie 1903 g. St. Petersburg, 2007, No. 26. |

| ↟68 | idem., no. 32. |

| ↟69 | Sobranie risunkov k puteshestviju Mejerberga. St. Petersburg, 1827, p. 57. |

| ↟70 | idem., p. 59. |

| ↟71 | Sobranie…, p. 44. |

| ↟72 | Rovinskij, D. Materialy dlja russkoj ikonografii. St. Petersburg, 1890, Iss. 10. No. 361, 365, 367; Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 72. |

| ↟73 | Sobranie riskunkov…, p. 55. |

| ↟74 | Savvaitov, P. Opisanie starinnykh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, v azbuchnom porjadke raspolozhennoe. St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 45. |

| ↟75 | jeb: Rus: стольник, in Muscovite Rus’, a member of court one rank lower than a Boyar. |

| ↟76 | Sobranie risunkov…, p. 40; Al’bom Mejerberga. Vidy i bytovye kartiny Rossii XVII veka. St. Petersburg, 1903, p. 25. |

| ↟77 | jeb: Rus. сотник, a Cossack officer equivalent to a lieutenant. |

| ↟78 | jeb: Rus. стрелец, literally “archer” or “shooter,” a soldier in a special permanent military squad in 16th-17th century Muscovite Rus’. |

| ↟79 | Sobranie risunkov…, p. 32. |

| ↟80 | Sobranie risunkov…, p. 32. |

| ↟81 | jeb: Rus. горлатка. |

| ↟82 | jeb: Rus. гречневик, also гречишник, грешневик, гречник, гречушник, a tall cylindrical felted hat, sometimes with a narrow brim, made from brown sheep’s wool, commonly worn by peasants in the 18th and 19th centuries. |

| ↟83 | Artsikhovskij, drevnerusskie miniatjury…, p. 204, illus. 55. |

| ↟84 | Sobranie risunkov…, p. 9. |

| ↟85 | jeb: Rus. треух, a type of hat similar to the ushanka, with earflaps and a lowered back panel over the neck. |

| ↟86 | jeb: Rus. малахай, another fur hat similar to an ushanka worn by peasants. |

| ↟87 | Zhilina, Put’ korony…, illus. 5. |

| ↟88 | Zhilina, Shapka Monomakha…, illus. 81-83. |