Today’s post is a translation of A.E. Zhabreva’s article on Russian clothing, as viewed and depicted via pictorial art sources from the 15th century, including manuscripts, embroidery, and icons. These sources are useful to determine what kinds of clothes were in fashion at the times those items were created.

A translation of Жабрева, А.Э. “Русский костюм в изобразительных источниках XV века.” Вестник Санкт-Петербургского университета [СПбГУ]. Серия 15: Искусствоведение. 2015 (4), с. 66-84. [Zhabreva, A.E. “Russkij kostjum v izobrazitel’nykh istochnikakh XV veka.” Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo universiteta [SPbGU]. Seria 15: Iskusstvovedenie. 2015 (4), pp. 66-84.]

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkiy-kostyum-v-izobrazitelnyh-istochnikah-xv-veka]

[Note that the author refers to a number of works of art, but only provides images of a subset of them. I have added galleries at the end of the article which provide, where possible, images of these mentioned works. The illustrations in the original article are in black and white. I have replaced them with color images where possible.]

Synopsis:

This article examines key pictorial artworks of the 15th century (icons, manuscript illuminations, samples of ecclesiastical embroidery) as sources for the study of Russian costume, allowing us to hypothesize the items of clothing that existed in the 15th century, and to identify differences by class, age and profession. Masterpieces of medieval art, such as the icons “Vladimir, Boris and Gleb” and “The Worshiping Novgorodians,” the Radziwiłł Chronicle, the sakkos of Metropolitan Photius, the suspended podea of Elena Voloshanka, and other items repeatedly drew the attention of 19th and 20th century researchers who in one way or another turned to the costumes depicted in them. Is is known that personages from the Old and New Testaments were traditionally depicted in canonical Greco-Roman or Byzantine apparel. The items reviewed here allow us to see that in the depiction of Russian saints, secondary characters, and the artists’ clients, images of contemporaneous clothing was also allowed. Deviations from the rules are found in iconography, in manuscript miniatures, and in ecclesiastical embroidery, which contain not only the images of princes and nobles, but also of commoners. They confirm the accordance of costume by feudal hierarchy, age of the wearer, the layering of male and female outfits, the availability in male wardrobes of short, narrow clothing such as kaftans, and the use of expensive imported fabrics.

Russian costume of the 15th century, both as a whole and in its regional peculiarities, has been little studied, due to the lack of material, written or pictorial sources.

Through the efforts of several generations of researchers of textual sources, we have revealed an array of terms denoting clothing, footwear, hats, and finery worn by medieval Russians in the 15th century. Amongst these researchers, one could name the textbook essays by P.I. Savaitov (1815-1895)[1]Savaitov, P.I. Opisanie starinykh russkikh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo ubora: izvlechenie iz rukopisej arkhiva Moskovskoj Oruzhenoj palaty. St. Petersburg, 1865., A.V. Artsikhovskij (1902-1978)[2]Artsikhovskij, A.V. Drevnerusskie miniatjury kak istoricheskij istochnik. Moscow, 1944.[3]Artsikhovskij, A.V. Miniatjury Kenigsbergskoj letopisi. Leningrad, 1932.[4]Artsikhovskij, A.V. «Odezhdy.» Ocherki russkoj kul’tury XIII-XV vv.: v 2 ch. Part 1. Moscow, 1969, pp. 277-296., and M.G. Rabinovich (1917-2000)[5]Rabinovich, M.G. «Odezhda russkikh XIII-XVII vv.» Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy: Materialy k ist.-ethogr. atlasu. Moscow, 1986, pp. 63-111.. Modern archeologists have also made a great contribution: N.V. Zhilina[6]Zhilina, N.V. «Tipologia zhenskogo golovnogo ubora s ukrasheniami vtoroj poloviny XIII-XVII v.» Zhenskaja traditsionnaja kul’tura i kostjum v epokhu Srednevekov’ja i Novoe vremja. Issue 2. Moscow-St. Petersburg, 2012, pp. 38-65., S.S. Rjabtseva[7]Rjabtseva, S.S. Drevnerusskij juvelirnyj ubor: osnovye tendentsii formirovanija. St. Petersburg, 2005., and Ju.V. Stepanova[8]Stepanova, Ju.V. «Drevnerusskij kostjum po pis’mennyjm i arkheologicheskim istochnikam X-XV vv.» Drevnjaja Rus’. Voprosy medievistiki. 2010 (4), pp. 84-92.

Pictorial artworks have been studied to a lesser degree, although certain items are well-known and are frequently mentioned by those researching medieval costume. The earliest study of these works was started by the designer and publisher V.A. Prokhorov (1818-1892), in one of the issues of “Materials for the History Russian Costume” dedicated to the 15th century.[9]Prokhorov, V.A. «Materialy dlja istorii russkogo kostjuma.» Russkie drevnosti. 1871 (6). pp. 65-74. A series of interesting publications on sources and reconstruction of Novgorod costume from the 14th-15th centuries have been written by O.V. Kuz’mina, a historian from Velikij Novgorod.[10]Kuz’mina, O.V. «Kostjum novgorodskogo bojarina (konets XIV-nachalo XV veka)» Rekonstruktsija kostjuma srednevekov’ja: sb. mater. Fashion-bloka XIV Mezhdunar. festivalja “Zilantkon-2004.” Kazan’, 2005, pp. 48-63.[11]Kuz’mina, O.V. «”Oblechjotsja v krasnye, i v chervlenyja, i v bagrjanyja odezhdy” (drevnerusskaja verxnjaja muzhskaja odezhda XIV-XV vekov).» Stratum Plus. 2010 (6), pp. 269-276.[12]Kuz’mina, O.V. «Detskij kostjum russkogo crednevekovogo goroda.» Integratsija arkheologicheskikh i etnograficheskikh issledovanij. Kazan’/Omsk, 2010 (1), pp. 346-350.[13]Kuz’mina, O.V. «Zhenskij novgorodskij kostjum v XIV-XV vv.: obzor istochnikov.» Vestn. Pskov. gos. universiteta. Ser. Sots.-gumanitar. i psikhol.-ped. nauki. 2013 (2), pp. 138-145.

Most of these items studied with regard to costume of the 15th century have been masterpieces of medieval Russian art, repeatedly considered by historians of the 19th and 20th centuries in terms of their dating, authorship, sources and analogs, and their technical and stylistic features. Here, we could name the work of the famous Russian historian and archeologist G.D. Filimonov (1828-1898)[14]Filimonov, G.D. «Ikonnye portrety russkikh tsarej.» Vestnik Obschestva drevnerusskogo iskusstva pri Mosk. publ. muzee. 1875 (6-10), pp. 35-66, 1-ja., the historian V.V. Nazarevskij (1870-1919)[15]Nazarevskij, V.V. Iz istorii Moskvy 1147-1913: Ocherki. Moscow, 1914., the Slavicist and paleographer M.V. Schepkina (1894-1984)[16]Schepkina, M.V. «Izobrazhenye russkikh istoricheskikh lits v shit’je XV veka.» Trudy GIM. Pamjatniki kul’tury. Iss. 12. Moscow, 1954., the art historian specializing in medieval Russian books and iconography O.I. Podobedova (1912-1999)[17]Podobedova, O.I. Miniatjury russkikh istoricheskikh rukopisej: k istorii russkogo litsevogo litopisanija. Moscow, 1965., the researcher of medieval Russian embroidery N.A. Majasova (1919-2005)[18]Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971.[19]jeb: See my translation of this book here: https://rezansky.com/medieval-russian-embroidery-majasova-1971/, and various scholars of medieval 15th century Russian art.[20]Popov, G.V. Zhivopis’ i miniatjura Moskvy serediny XV-nachala XVI veka. Moscow, 1975.[21]Smirnova, E.S. Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda, XV vek. Moscow, 1982. They did not specifically study costume, but anyone studying medieval Russian clothing should be aware of these studies.

Here, we shall consider examples of three types of pictorial sources: painted icons, manuscript illumination, and ecclesiastical embroidery.

Monuments of Icon Painting

[Click on the thumbnail to see a larger version of the image.]

[Color image found online here.]

Icon painting of the 15th century, being subordinate to the canons of Byzantine iconography, left virtually no space for artists to reflect their existing reality. One small “loophole” was the depiction of Russian saints, which nominally allowed depictions of actual clothing. Especially in the borders of “Life”-style icons, one finds secondary characters in authentic costume.

Royal clothing of the 15th century are depicted on the Rostov-Suzdal’ school icon “Boris and Gleb” (State Tretyakovskaya Gallery).[22]jeb: You can see an image of this icon in the gallery below. Their coats [shuby], one of fur, the other with a field of blue with scarlet flowers, both with loose sleeves and wide black collars, are draped over long, loose robes on both princes’ shoulders. Boris’s apparel is fastened by a single button at the neck, but three pairs of double buttonholes are visible. Gleb has his coat fastened with all buttons (one at the neck, and three with braided frogging). On the forearms, the sleeves are decorated with wide stripes.

A late-15th century icon from Novgorod’s St. Sophia Cathedral (one of the so-called “Sofia Tablets”), “Sts. Vladimir, Boris and Gleb” (Home-Museum of P.D. Korin)[23]Popov, pp. 319, 519 [Illustration 1], is an example of matching costume to the age and feudal hierarchy of the owner. All three figures are presented in luxurious multi-layered outfits from multi-colored fabrics with exquisite patterns. Their long shirts [rubakhi] (or svity?) are brightly colored: on Vladimir, bright lines form squares against a dark background; Boris’s has bright circles against a raspberry field, with ornamentation inside the circles; Gleb’s has a dark blue fabric with light-blue circles, filled with gold patterns inside them. The sleeves on Boris’s outfit are narrow with decoration at the wrists; Vladimir and Gleb’s sleeves are wide, decorated with trim, and lined in an alternate color, exposing the narrow sleeves of their undertunics. The hem-lines are decorated with wide golden stripes with circles and ovals of precious stones. Vladimir and Boris wear wide mantle-collars decorated with stones and pearls; Vladimir’s has a strip added to the center going down to mid-chest. The outfits of all three are belted.

The princes’ outer garments are distinguished: a fur coat of sable is “thrown” over Vladimir’s shoulders, with reversed lapels that make it possible to see that the same fur is used on the collar, lining, and inside the opening of the sleeves. The top of the fur coat is dark crimson, with a large pattern of wavy lines, curls, and shamrocks. The forearms of the loose sleeves are decorated with strips of dark yellow, with white dots representing pearls. Boris’s outerwear is an opashen’[24]jeb: An opashen’ was a long-skirted coat with short, wide sleeves, typically worn in the summer. The word is derived from raspakhnut’, meaning “to fly open.”, the outer part of which is made from dark-blue fabric with a light-blue design; the lining and collar are of white fabric, as if composed of snowflakes; the flaps, hem and sleeves are decorated in gold braid with pearls. Gleb’s outer wear is cloak [plasch] of raspberry-colored fabric with a floral pattern, edged on all sides with gold braid and dotted with pearls, and with a snow-white lining. The cloak appears to be pinned to his right shoulder, but the fastening is not visible, as it is covered by a wide mantle.

Vladimir, as the eldest of the three, wears a crown with points and pearls, as worn by the Byzantine emperors and all “monarchs.” Boris and Gleb are crowned with small hats with tall tops and fur edges, headwear with which the miniaturists obligatorily distinguished Russian princes.

Thus, on one icon, we see three outer princely robes according to the age and position of the person depicted: the most expensive is the shuba (worn by Vladimir), followed by the opashen’ (worn by Boris), which is similar to a shuba but without the inner fur lining [podpushka], and finally a sleeveless cloak [plasch] (worn by Gleb), possibly a privoloka[25]jeb: An outer cloak, literally, a “dragging” cloak..

In the Moscow school icon “Kosmas and Damian” from the second quarter of the 15th century (Andrej Rublev Museum of Medieval Russian Art)[26]cf. Popov, illus. 1.[27]jeb: You can see an image of this icon in the gallery below., we see captured everyday city outfits as may well have been in use amongst the male population. We see loose shirts, decorated at the lower hem with a band of a different color. Damian is wearing a dark shirt which falls below his knees. Kosmas is dressed in two shirts; the inner is light colored and longer, and the overshirt is dark and falls just below his hips. Both outfits are decorated with mantles [oplech’e]. Their small cloaks are draped with decorative folds.

This practice of wearing two shirts at the same time is also found in other works of art. For example, Zechariah is dressed this way in the icon “The Conception of John the Baptist” (second half of the 15th century, Andrej Rublev Museum of Medieval Russian Art).[28]cf. Smirnova, pp. 298, 503.[29]jeb: You can see an image of this icon in the gallery below. The outer tunic is decorated at the hem and at the ends of the sleeves with trim. The short cloak appears to be made of thin fabric with a geometric design. The biblical character wears a medieval Russian princely hat, which differs from the majority of its kind by its ring of white, rather than dark, fur.

[jeb: Color image found online here. See the gallery below for the full icon.]

The icon “The Praying Novgorodians” (1467, Novgorod State Historical-Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve) is one of the most valuable works of art for the study of Russian costume[30]Smirnova, pp. 246, 440[Illustration 2]. This rare example of a medieval Russian icon showing the icon’s patrons comes from the St. Nicholas-Kochanovskij church in Novgorod. In the bottom row of the icon (the Deësis row) is the family of the boyar Kuz’min, with the figures depicted in prayer.

The costumes of the Novgorodians differ from other images of the same time period. Six men of different ages are garbed in short caftans with decorative clasps; light-blue, green, yellow, brown and red robes with long sleeves and wide turndown collars are thrown over their shoulders. They wear narrow pants and tall boots. Here we see depicted not princes in iconographically canonical outfits, but rich people in secular clothing, as noted by G.D. Filimonov[31]Filimonov, p. 65. and A.V. Artikhovskij.[32]Artikhovskij, «Odezhda», p. 289. The inner garments are particularly distinguished (Artikhovskij calls them shirts, Filimonov calls them narrow-sleeved, single-breasted kaftans), shorter than the shirts and svity of the saints in the previous icons but clearly free-flowing, with a large number of buttons and frogs (about 15). Their belts are uniformly black. Their outerwear are more like opashni or epanchi[33]jeb: An epancha is a long, wide cloak with a hood. Typically, epanchi are sleeveless. The word comes from Turkish yapyndzha, and the garment was borrowed from the Arabian East. than shuby (Filimonov calls them “cloaks”); their collars are of different colors, and are of fabric rather than fur. The collars are wide and turned down, almost completely covering the shoulder. These outer garments are trimmed at the hem with a wide stripe of trim; their long, knee-length sleeves are straight and relatively wide.

G.D. Filimonov has excellently described these outfits:

[One of the figures] wears a black kaftan, seemingly without buttons, and a red cloak with black buttonholes; the collar has a brown field with large white squares and cross-shaped burdocks. On the left panel, in the opening there oblong buttons, fastened by a loop on the right panel. The lower part of the figure is damaged. Standing in front of him, with his back turned, is a figure without a beard, a chubby, youthful type, in a black cape, apparently without buttonholes, with a yellow collar with large red ornament. His kaftan is reddish-brown with buttonholes; his boots are red. The next figure, with a long beard ending in a point, is in a yellow cloak decorated with trim along the hem, a red lining, a red collar and red buttonholes; his kaftan also has buttonholes; the belt is black with white overlays, possibly silver; his boots are red, with a band below the calves.

Filimonov, p. 65.

The woman standing on the far right, the boyarina Maria Kuz’mina, is wearing a dress decorated with a fur collar, loose sleeves and a number of buttonholes and frogs. We can see the wide sleeves of her red underdress, edged with a black stripe and a row of pearls. On her head is a white wimple [plat], the long ends of which hang about her shoulders and end in fringe. O.V. Kuz’mina has justly hypothesized that this kind of dress with wide sleeves were the forerunner of the letnik which came into use in the 16th century.[34]Kuz’mina, «Zhenskij novgorodskij kostjum…», p. 141.. In the center of the composition there are two children in white shirts with red decorations and sashes.

In this way, the icon “The Praying Novgorodians” gives us a rare opportunity to become acquainted with the outer appearance of 15th-century Novgorodians, who dressed differently from their contemporaries from Moscow, Tver’, or other Russian cities. This image, along with other materials, allowed A.V. Artsikhovskij to compare Novgorodian clothes from the 15th century with those of western Europe and to note their originality.[35]Artsikhovskij, «Odezhda», p. 291.

[jeb: Color image found online here. The full icon can be seen in the gallery below.]

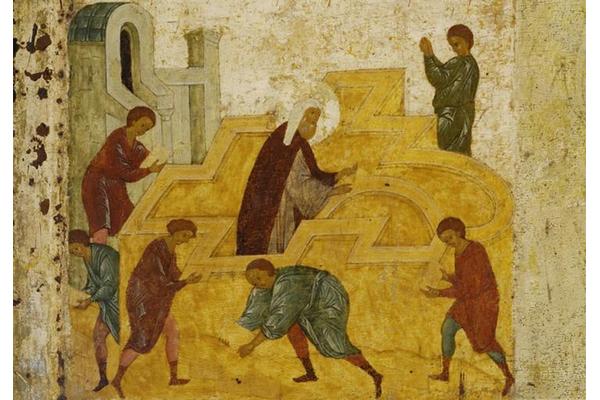

The icon “Metropolitan Peter with Scenes of His Life” by Dionysius and his workshop, dated to the late 15th-early 16th century (State Museums of the Moscow Kremlin) is an example of how secondary characters were dressed in costumes that were contemporary to the artist. On various border scenes of this icon we see not only long rubakhi, but also shuby, kaftans, and opashni worn over the shoulder, as well as both adult and children’s outfits. In the next to last scene on the left side (“Peter Lays the Foundation for the Cathedral of the Assumption in Moscow, 1324”), we see the builders erecting the church wearing long, loose shirts and colored pants tucked into tight boots.

In the opposite border scene, on the right (“Ivan Kalita’s Dream”), the Muscovite prince and his commander Protasij are presented in outfits that are far from canonical [Illustration 3]. The prince’s outfit include a shirt [sorochka], pants, boots, a caftan and a hat. The red shirt, with a yellow stripe at the hem, does not cover the knees; his pants are narrow, tucked into yellow boots that fit the legs. The short (just below the knees) kaftan is “sewn” from dark-green fabric with a geometric pattern; the lapels and turned-down collar are dark, with two strips of yellow along the edges of the breast. Similar stripes are also visible along the hemline and at the cuff. The kaftan is belted. On his head, Ivan Kalita wears a different hat than is typically seen in icons; its peak is triangular-shaped and white, with red lapels. Protasij’s outfit also consists of a shirt, pants and boots, but instead of a kaftan, he appears to be wearing an opashen’, a long coat with a small turn-down collar and hanging sleeves. His head is not covered.

[jeb: Images for “Monuments of Icon Painting”]

Boris and Gleb (15th century, Rostov-Suzdal’ school, in State Tretyakovskaya Gallery). Color file from https://shorturl.at/dAPR0

Sts. Vladimir, Boris and Gleb (late 15th cent. in the Home-Museum of P.D. Korin). Color file from https://shorturl.at/coryB

Kosma and Damian (second quarter of the 15th century, in the Andrej Rublev Museum of Medieval Russian Art.)

The Conception of John the Baptist (second half of the 15th century, in the Andrej Rublev Museum of Medieval Russian Art.) Color image found online here: https://tinyurl.com/y2dlg5bl

The Praying Novgorodians (Novgorod school, 1467, in the Novgorod State Historical-Architectural and Artistic Museum-Reserve.) Color image found online here: https://tinyurl.com/y3j8juxa

Metropolitan Peter with Scenes of His Life (Dionysius and his workshop. Moscow school, 1480s, in State Museums of the Moscow Kremlin.) Color image found online here: https://tinyurl.com/y2jrtq3f

The Founding of Moscow’s Cathedral of the Assumption, border scene from Metropolitan Peter with Scenes of his Life. Color image found online here: http://rusfact.ru/node/80758

Ivan Kalita’s Dream, border scene from Metropolitan Peter with Scenes of his Life. Color image found online here: https://tinyurl.com/y2vq88ew

Miniatures and Capitals from Manuscripts

Chronicles and manuscripts on various topics serve as sources not only for oral, but also as valuable visual information about the clothing of their time, preserved in miniatures, capitals, illuminations and border drawings. A.V Artsikhovskij points to a Psalter as an example of images of contemporary clothing, where a capital “M” is presented in the form of two fishermen dragging a net: both are dressed in a shirt to the knees and tall boots.[36]Artsikhovskij, «Odezhda,» p. 283.[37]jeb: See image in the gallery below. In the Life of Sergius of Radonezh, dating back to the 15th century, we find the earliest depiction of bast shoes [lapty]: one of the miniatures presents a plowing scene and a peasant in bast shoes.[38]Saburova, M.A. «Drevnerusskij kostjum.» Drevnjaja Rus’: byt i kul’tura. Moscow, 1997, p. 103.[39]jeb: Unfortunately, this source does not include an image of the manuscript in question.. V.A. Prokhorov, however, lamented the absence in manuscripts of this period of “such a prolific artistic imagination” as is seen in 16th-century manuscripts, saying that “the miniatures, illuminations and capitals are all drawn roughly and uniformly” [40]Prokhorov, p. 65..

One of the primary pictorial works of art referenced for the study of costume of the 15th century is the Radziwiłł Chronicle (aka the Königsberg Chronicle) in the collection of the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences.[41]Radzivilovskaja letopis’: faks. vosproizvedenie rukopisi, khranjaschejsja v B-ke Ros. akad. nauk. St. Petersburg/Moscow, 1994. 2 Volumes. Researchers have dated the creation of this manuscript variously, but primarily to the late 14th-early 15th centuries; the archaic nature of the miniatures have led to the suggestion that it was a copy from a 12th-13th century original.[42]Podobedova, pp. 50-53. Studying the costumes in the work, however, proves that the Radziwiłł Chronicle was written (or at least completed) in the 15th-early 16th centuries. A.V. Artsikhovskij considered this work to be a source for the history of 15th century costume.[43]Artsikhovskij, «Drevnerusskie miniatjury…», p. 28; «Odezhda», p. 277. V.A. Prokhorov noted that “these drawings were started in the 15th century, and finished early in the 16th century. Based on this, we can assume that the drawings in the second half of the manuscript include images of clothing which began to appear only in the early 16th century.”[44]Prokhorov, p. 68. Indeed, in miniatures, we find images of medieval clothes side by side with those of the Renaissance, which entered into use in Europe at the turn of the 15th-16th centuries.

It is curious that historians and art critics who have studied the Radziwiłł Chronicle have shown interest in the items of clothing depicted. For example, archeologist V.I. Sizov (1840-1904) dedicated a large portion of his article “Miniatures of the Königsberg Chronicle”[45]Sizov, V.I. «Miniatjury Kenigsbergskoj letopisi.» Izvestija ORJaS. Vol. 10, book 1. St. Petersburg, 1905, pp. 1-50. to clothing and their comparison to European counterparts. Based on the nature of these clothings, Sizov in particular built a chain of assumptions about the authors and artists, and possible sources for their creativity. Art critic O.I. Podobedova made interesting observations about the contributions of three master artisans on the book, working from a single source, including by studying images of costumes.[46]Podobedova, p. 55. In her opinion, the first artisan probably copied the original as is, with the second artisan making changes with a goal to, among other things, depict “a feudal order of precedence” through the use of clothing. The first master left the heads depicted without hats, as in the original; the second, guided by norms of the 15th century, subsequently drew hats on the princes, “either hemispherical with arc-shaped ornament, or tall with fur margins, he dresses the princes in crowns with 5 or, more rarely, 3 points[47]Podobedova, pp. 64, 68.. V.A. Prokhorov also wrote about these changes, noting that:

… deviations from the original are visible here and there, for example, in the old hats and other objects where the newly drawn lines not only do not coincide with the previous lines, but where they have obviously been deliberately change … for example, where the previously drawn hats were bigger, and have since been reduced in size.

Prokhorov, p. 68.

On the pages of the Chronicle, males are most often depicted in long or short, relatively loose shirts, with the collars, cuffs, and often the hem decorated in a different color. Shirts, as a rule, are belted, but the belt may be hidden by a small lump of overhanging fabric. The sleeves are long and narrow. Sleeves are are drawn short only in specific cases – when they are rolled up for work (folio 5 obv.). O.V. Kuz’mina showed how the length of the shirts depended on the social rank and occupation of the wearer.[48]Kuz’mina, «Detskij kostjum…», p. 269

[jeb: image captured from a personal copy of a facsimile of the chronicle.]

We also see other variants of male clothing, for example in the scene of the murder of Andrej Bogoljubskij (leaf 215)[Illustration 4]: the prince is wearing a single shirt, without an oplech’e. Its straight cut in front and the open lapels of the shirt are visible. The prince’s bare feet and chest clearly show that in this scene, this shirt is his only garment. It is curious that the obligatory princely cap is shown here symbolically – without its fur edge and unpainted.

One of the witnesses of this murder is dressed in a long, hanging outfit. It appears that his arms are threaded into the sleeves which are much longer, as if to speak to the old man’s helplessness. This gown is buttoned from bottom to top: three doubled lines (a fourth is hidden by the shield of the approaching soldier) represent button frogs. The hem and cuffs of this greenish-gray gown are painted in tan. A small turn-down collar with rectangular corners is left white.

Characters dressed in long outfits with many buttons are found more than once in the pages of the Chronicle (cf. folios, 106, 152, et.al.). Cloaks are draped over the shoulders of many, and fashionable robes from the turn of the 15th-16th centuries, which in Germany were called Schaube, are also found. Some young men are dressed in two-tone parti-colored outfits (folios 203 obv., 206 obv., et. al.). On many we see narrow, pointed-toe ankle boots without heels, up to the mid-calf, characteristic of the 14th-15th centuries.

Men’s heads are sometimes left uncovered, or in other cases they wear hats or helmets. In addition to the hat [shapka], a rounded cap with fur trim, we also find on the heads of the princes (folios 22 obv., 180 obv. 183, et.al.) a headdress in the form of a round miter: a black line marks the rim and arcs, and sometimes dots are also drawn. The hats of Novgorodians, Pskovans and Rjazanites differ from each other. Clergymen and boyars are often left bare-headed, and sometimes “princes wear little princely hats, and the Novgorodians wear hats with an oblique lapel.”[49]Podobedova, p. 68. The headwear of foreigners also differ: “the Torks, Kosogs, Khozars, Pechenegs, Polovtsy, and Volga Bulgars each have their own particular pointed cap; the Greek ambassadors are depicted in whimsical hemispherical caps.”[50]Podobedova, p. 69

Most of the women in the Radziwiłł Chronicle miniatures are “dressed” in loose, ankle-length belted dresses or long-sleeved tunics (ritual shirts with lowered sleeves). A dancing girl is depicted in such an outfit, with sleeves which hang significantly lower than her hands, and with her hair loose about the shoulders (folio 6 obv.).

Princess Ol’ga, who appears repeatedly in the Chronicle, is depicted in a dress and cloak, with a headband that “stands in as a crown, in the form of a hoop.”[51]Prokhorov, p. 69.[52]jeb: See a sample image of Princess Ol’ga in folio 29, in the gallery below. Her dresses and cloaks vary in color. This variation of a female outfit is traditional for Byzantine and Russian icon painting, but was it as common in life?

In the Radziwiłł Chronicle, we also find a completely different type of female outfit, characteristic of European Goth women. On some of the miniatures (folio 7, et. al.) two dresses are clearly visible: an inner dress with long narrow sleeves, and an outer dress with wide, shortened sleeves. Andrej Bogoljubskij’s wife, Princess Ulita Kuchkova, a Bulgarian by birth, is shown in such an outfit (folio 215). Her outer dress is draped in front and slightly raised, and a small train is visible behind. The princess’s high headdress is also a kind of cap; it leaves the neck and shoulders bare.

That women in this series of miniatures are dressed in the European style has been noted by all researchers of this work, in particular O.V. Kuz’mina:

All of them are clearly wearing European outfits; moreover, a costume from the late 15th century, conveyed by the artist quite accurately: a kirtle with long sleeves, narrow, tight about the figure, with stiff cuffs, a European cloak, and a wulsthaube headdress. <…> Such clothes were worn in the 15th century in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, however, the artist illuminating this manuscript thought it apt to dress this Russian princess in European clothing.”[53]jeb: See the example in folio 215, with Princess Ulita holding her husband’s severed arm.

Kuz’mina, «Zhenskij novgorodskij kostjum…,» p. 142.

Women’s headwear in the Chronicle are seen as cloth panels wound in various manners, and crowns of various shapes. N.V. Zhilina analyzed them in terms of their construction and existence.[54]Zhilina, pp. 43-48. She classified Princess Ol’ga’s headwear as a “towel-like ribbon,” and noted that “it has a sustained hemispherical shape in the upper part, giving an impression of some rigidity,” and that “this reflects Ol’ga’s special status as ruler of Rus’.”[55]Zhilina, p. 43. A different type of veil, wound around the head in the form of a turban, can be seen on the wife of Andrej Bogoljubskij and others women.[56]Zhilina, p. 47. As a rule, this is seen on women wearing European Gothic dresses. Girls’ hair was left uncovered.

I.O. Podobedova noted that in the second third of the manuscript, there is an increase of Western motifs, observed in clothing, architecture, and even in the manner in which the miniatures themselves were executed.[57]Podobedova, p. 72. V.A. Prokhorov also noted; “In the miniatures in general, a German influence is noticeable; this is primarily visible in the second half of the manuscript. Various figures are seen wearing German outfits.”[58]Prokhorov, p. 68. He justifiably suggested that “either these drawings were made under German influence, or in the places where the manuscript was created, probably in Western Russia, these same outfits were worn just as in the West.”[59]Prokhorov, p. 68.

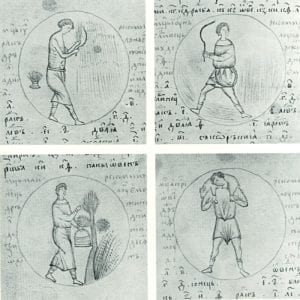

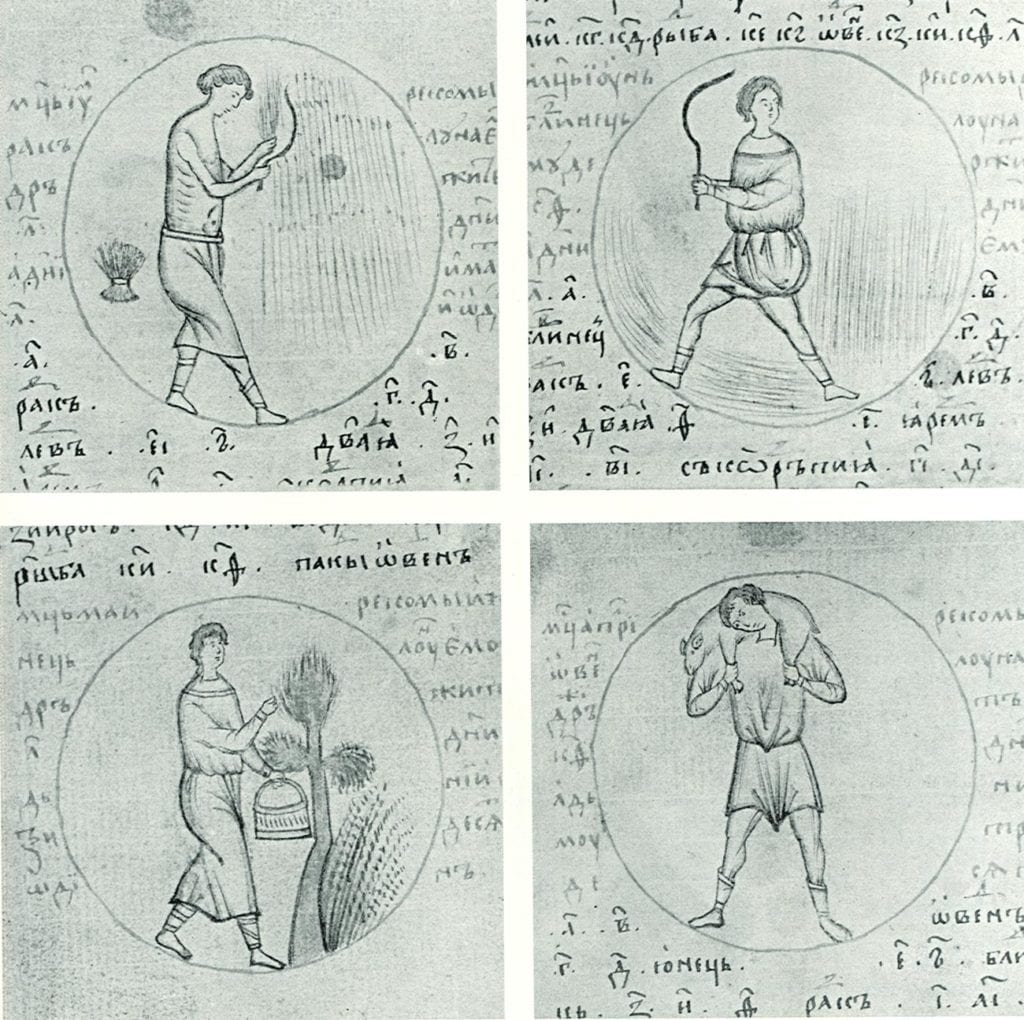

Images of peasant clothing are seen in the miniatures in the “Book of John of Damascus” (late 15th century, Russian State Library, Illustration 5).[60]Popov, pp. 52-55. Pictorial images of peasants are placed in circles among the text. On one of the figures, who holds a sickle, is dressed in a short, belted shirt with a round collar [oplech’e] about the shoulders; he has leg wraps [obmotki] wound around his legs, and a sack is attached to his belt. This person is harvesting grass for livestock: cutting the grass with a sickle and collecting it in his sack. This is unlike the man reaping rye or wheat, who cuts the cereal with a sickle and binds them into a sheaf. This reaper is bare-chested. He is wearing free-flowing pants with a belt. Most clearly presented are the clothes on the man carrying a piglet on his shoulders. He is shown standing straight, in a single shirt without a collar. His shirt is relatively short, tunic-like, and belted, with long, narrow sleeves. The neckline of the shirt is square shaped.

The fourth miniature depicts a woman in a long belted shirt, with long narrow sleeves and a round collar. Her lack of headgear indicates she is a young girl. The basket in her hand indicates her occupation – picking berries nuts or pine cones.

[jeb: Images for Miniatures and Capitals from Manuscripts]

Capital “M” from a 15th-century Psalter (Artsikhovskij, A.B. «Odezhda.» Ocherki russkoj kul’tury XIII-XV vv.: v 2 ch. Part 1, Moscow, 1969, p. 283.)

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 5 obv: Violence of the Obrin against the Dulebi: Obrin men in carts being pulled by Dulebi women.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 215: The Murder of Andrej Bogoljubskij by boyar conspirators.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 106: Gleb executes the sorcerer.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 152: Heavenly Signs in 1104.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 203 obv.: Izjaslav’s return to his father in Rostov

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 206 obv.: Mstislav’s return to Vladimir

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 180 obverse: The reconciliation of Izjaslav of Kiev with Gleb Gorodetskij.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 183: Jurij Dolgorukij is selected to be prince of Kiev.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 6 obv: Dances and Games of the Northern Tribes.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 29: Ol’ga’s Second Revenge for the Murder of her Husband – burning the Drevlyan ambassadors alive in the bathhouse.

Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 7: Women of the Giliev tribe constructing buildings and plowing land.

The Allegories of the Months, miniatures from the Book of John of Damascus.

Monuments of Ecclesiastical Embroidery

Medieval Russian ecclesiastical embroidery was closely tied to icon painting and adhered to the same canons, as the designers [znamenschiki] (those who drew the design for the embroidery) were usually icon painters. Only two monuments of this type contain images invaluable to the study of 15th century costume. These have long attracted the attention of researchers for their artistic and technical merits.

[Color image found online here. See an image of the complete sakkos below.]

The so-called Great Sakkos of Metropolitan Photius (?-1431), created in 1414-1417 (Moscow Kremlin Armory Chamber)[61]«Khudozhestvennye sokrovischa Moskovskogo Kremlja. Moscow, 1984, folio 115., is decorated with more than 100 embroidered images of characters from biblical history, as well as portraits of political figures of its day. Portraits embroidered onto the sakkos give us an idea of otherwise unpreserved secular monuments, especially clothing. V.V. Nazarevskij gives this description of the portrait of Grand Prince Vasily I’s family [Illustration 6]:

In this portrait, Vasilij I has a manly face, with a black mustache and a moderate beard, which is split in two at the end. He is wearing a low-belted red kaftan with a diamond design and narrow green trousers which are tucked into boots of red Morocco leather with clasps in three places. Over this, he has a relatively short green cloak or privoloka, with gold ornament and a blue lining. A gold bangle [zapjast’e] is visible on his right hand; with this hand, he holds a scepter, studded with pearls. On the head of the Grand Prince there is a filigree gold crown, with crosses at the top and a red velvet tulle. Grand Princess Sof’ja wears a type of sarafan of silver brocade with red diamonds inside golden frames; the dress is decorated with a gold necklace, and a matching apron and belt. Over the sarafan, she is wearing a shuba or long cloak, which is gold with silver circles and dark blue and red crosses. The Grand Princess wears a crown which is similar to her husband’s.

Nazarevskij, Iz istorii Moskvy…, pp. 69-70.

G.D. Filimonov also turned his attention to the sakkos and analyzed the portraits depicted. He believed that Vasilij Dmitrievich is depicted in an outfit that “has nothing to do with the Greeks” of that time, and that he wears “a type of half-kaftan, folded back on itself and cinched with a wide belt just below the waist.

This “half-kaftan” is checkered, red and gold. Below the kaftan there are relatively narrow green pants, with the ends tucked into tall boots. He is also wearing a short cloak or privoloka, of green color, with gold designs, and lined in blue with gold hatching. <…> The prince’s crown is of gold filigree, with crosses at the top, and with a red velvet tulle.

Filimonov, Ikonnye portrety russkikh tsarej…, p. 47.

As for Grand Princess Sof’ja Vitovtovna, G.D. Filimonov also called her outfit “a kind of sarafan of silver brocade, with red cells outlined in gold.”[62]Filimonov, p. 47. In his opinion, the sarafan was decorated with a gold “apron with a decorated hemline and belt,” and over it all, “a shuba or cloak.”

Both historians agreed that the prince wears a short cloak or privoloka on his shoulders, which the historian A.V. Tereschenko writes, later turned into the korzno and was worn by princes, boyars and nobles before the era of Peter I.[63]Tereschenko, A.V. Byt russkogo naroda. Part I. Moscow, 1997. There are some doubts as to the names of the princess’s outfit. It is unclear how these historians discerned an apron in the princess’s clothing. There is no reason to confidently state that Sof’ja’s dress is a sarafan, that is, sleeveless, which has not been proven to have even existed in the 15th century by that name. M.G. Rabinovich has theorized that at that time, female sleeveless clothing was called a shubka, a word which often appears in documentary sources.[64]Rabinovich, p. 69.

In our opinion, the princess is wearing two dresses: the inner one is longer and lighter, with an ornamented hem that is clearly visible. The outer dress is clearly free-flowing, made from silver fabric with a checkered pattern, with the front opening and hem framed by golden braid. It’s collar is indistinct, but also edged by a strip. The wavy line descending to the middle of her chest could be read as the edge of a mantle, especially given that immediately above there are three lines that could indicate precious stones. The visible parts of narrow sleeves, judging by the golden color which is also seen on the hem, are part of the inner dress. But, this does not prove the absence of sleeves on the upper dress, since half-length sleeves on the upper dress would not be visible from under her cloak, and without a larger and more detailed image. As for her cape, it is likely the same kind of privoloka as worn by her husband, but longer and decorated with ornament not only on the outside, but also within.

Archeological artist F.G. Solntsev (1801-1892) reinterpreted this embroidered portrait of the Grand Princely couple into a beautiful watercolor.[65]This watercolor image can be viewed online here: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-543e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99#/?zoom=true It should be noted that the sakkos has also attracted the attention of foreign researchers.[66]Piltz, E. Trois sakkoi byzantins: analyse iconographique (Vol. 17). Upsalla, 1976.

[The full podea can be viewed in the gallery below.]

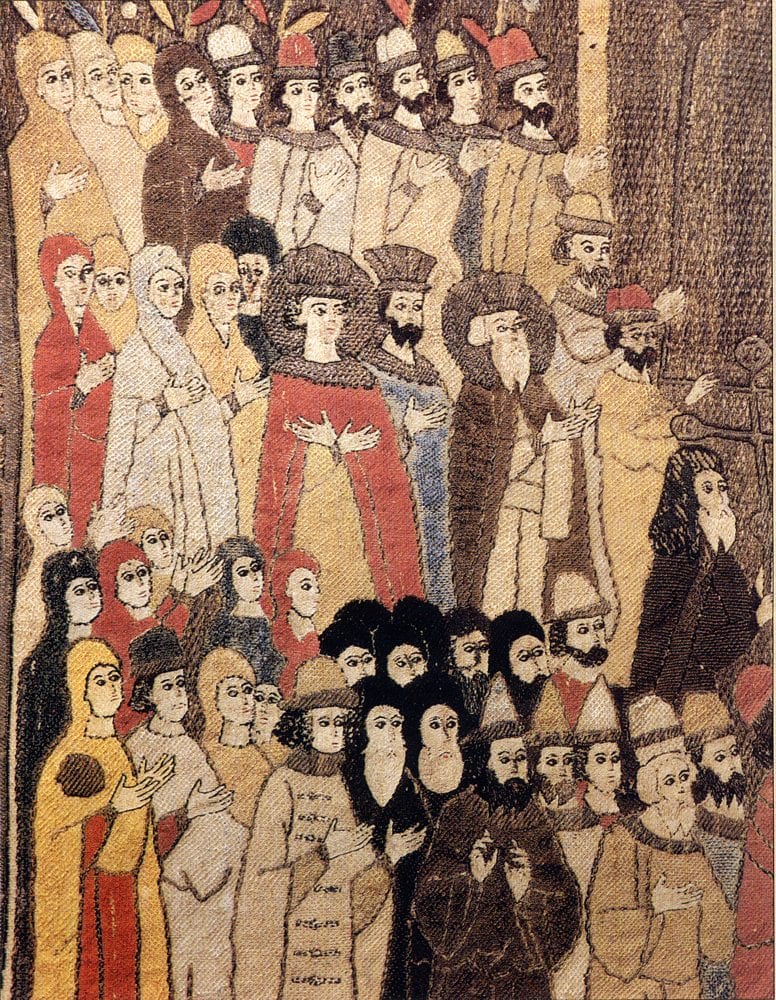

The podea “The Liturgical Procession” or “Displaying Our Lady of the Hodegetria on Palm Sunday (4 April 1498)[67]Majasova, plate 27.[68]jeb: See my translation of this source’s description of the podea on my blog.[69]Efimova, L.V. Kostjum v Rossii: XV – nachalo XX veka: iz sobr. GIM. Moscow, 2000, p. 10.[70]Epokha parsuny: russkij istoricheskij portret: kat. vyst. 26 dek. 2003 g. – 31 maja 2004 g. Moscow, 2003, pp. 38-39., created in the workshop of Elena Voloshanka, daughter of the Moldavian (Wallachian) monarch and wife of the eldest son of Ivan III (circa 1489, State Historical Museum), is a monument of ecclesiastical embroidery and a source of information not only about the historical personages at the end of the 15th century, but also of their clothing.

The scholar of medieval Russian embroidery N.A. Majasova wrote that this podea was created to commemorate the coronation of Dmitrij, grandson of Ivan III, on 4 February 1498.[71]Majasova, p. 20. She noted that this work was atypical for medieval Russian art, and that it was “essentially a secular picture, depicting a real event involving historical persons.”[72]Majasova, p. 20.

This work has repeatedly drawn the attention of our national researchers; in particular, the efforts of an employee of the State Historical Museum, M.V. Schepkina, to identify the main characters depicted on the podea. Significant clues in the identification of various persons were found in their clothes, hats, and hairstyles as depicted, evidence of their use in the 15th-16th centuries.[73]Schepkina, Izobrazhenie russkikh istoricheskikh lits…

The podea is composed of a centerpiece and an ornamental border. Our interest here is the multi-figured composition embroidered in the centerpiece [Illustration 7]. On it are embroidered the figures of men and women, many of whom are presented in the clothing of their time.

In the center of the composition is a deacon in brown robes, carrying an icon. To the right and left, others carrying censers, liturgical fans and sunshades follow him. A crowd of people moves toward them, divided into two groups. In the upper ranks stand people with long branches, nominally representing willow branches.

On the right, the clothes are simple and belted; on the left, everyone is dressed more richly: above their kaftans, they wear overclothing that is thrown over their shoulders like a cloak (a shuba or, perhaps, an opashen’). The left row ends in a group of women.

Majasova, p. 13.

In the second row on the right are the higher clergy, and on the left are three male figures with royal crowns. M.V. Schepkina particularly notes that the figure with the young face and halo “in no way should be mistaken for a woman; the primary evidence of this is his uncovered hair. This figure cannot be a tsaritsa or grand princess, as no married woman of medieval Rus’ would appear amongst their people with their hair uncovered.” In addition, other male figures have their hair cut the same way, to the middle of the ear.[74]Schepkina, p. 16. M.V. Schepkina asserted that this was a depiction of Dmitrij, grandson of Ivan III.

In the bottom row, we see figures in various outfits: monks, singers (three figures in pointed hats), a Frankish type in a short tunic. In the group of women, the class hierarchy is not obvious.

“On the left, the group consists of women alone, some of whom stand out for their outfits: for example, at the very edge stands a woman in raspberry; the yellow veil on her right has a round golden patch; this appears to be a so-called tablion, a sign of royal dignity. In front of her are two female figures; the clothing on the first is not clear, but she wears a hat on her head, with stripes running to her shoulders; based on this headdress, she is most likely a young girl. The second figure is undoubtedly a young girl, based on her attire: she has a hat on her head, has curls hanging down to her mantle, and long clothes with wide, draped sleeves. Along the entire opening all the way to the floor, there are frequent buttonholes. It is possible this is a kortel’, an outfit similar to a letnik, made of fur to be worn outdoors in the winter, or possibly a telegreja work over a letnik.”[75]Schepnik, p. 14. Is is most likely that the matron with the yellow veil and the gold patch on her shoulder represents Sof’ja Fominishna Palaeologus. The girls with the hats, then, can be theorized to be her daughters Feodosia and Evdokia, who would have been 21 and 12-13 years old at this time.

“Dmitrij’s mother, Princess Elena Stefanovna [“Voloshanka”], it can be proposed, is also in this group of women, possibly the figure in the yellow veil standing between the two girls. She is depicted quite modestly. If not for the fact that she was placed among the royal family, it would not even be possible to consider her to be the mother of one of the primary characters in this scene. Sof’ja Palaeologus, despite the commonality of this image, is indicated by the golden circle on her veil. In this way, the rules of court etiquette are completely consistent in this work: the Grand Prince and Princess are presented as per the Byzantine custom, with symbols of imperial power and origin. The younger daughter of the Grand Prince, as a secondary character, is depicted a bit more realistically, in the outfit of a 15th century Russian boyarishna. In this way, the podea gives us a unique view of court ceremonies in Moscow at the end of the 15th century.”[76]Schepkina, p. 16.

This interpretation by M.V. Schepkina was supported by N.A. Majasova.[77]Majasova, description for plate 27.

[jeb: Images for Monuments of Ecclesiastical Embroidery]

The Great Sakkos of Metropolitan Photius. 1410s. Front.

The Great Sakkos of Metropolitan Photius. 1410s. Reverse.

The Liturgical Procession, Palm Sunday, 4 April 1498. (c. 1498, State Historical Museum).

[jeb: Color image captured from my copy of Majasova’s book.]

Some Conclusions

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the efforts of researchers of various specialties revealed, published and analyzed monuments of 15th century medieval Russian art. This process continues to the modern day, and it is already possible to speak with confidence about the various types of clothing worn, about their division into inner and outer wear, and about the class and age differences in outfits.

Based on the considered artworks, we can conclude that male everyday clothes consisted of pants and a shirt (or two), belted with a sash. The length of the shirt depended on age and occupation. Their shoes were either bog shoes [porshni] or low boots. Women wore belted, ankle-length shirts and veils. The winter clothes of commoners are not depicted in these works.

Middle-classed males probably dressed differently in various cities; in two shirts, the upper of which was shorter than the under shirt, both of various colors, or in short shirts and caftans. Their outerwear were cloaks and epanchi. Women wore two shirts or two dresses, headwear in the form of a band or a veil. The outer clothing of wealthier women was an oversized dress with wide, but not very long, sleeves. Fitted dresses in the Gothic style, as well as headwear in the form of a turban which left the neck uncovered, may have been in use in the western territories.

The clothing of nobility were inner and outer long shirts of various colors. In wartime or while traveling, they wore shorter shirts and loose-fitting kaftan-style items (svity, kozhukhi). Narrow pants were tucked into the tight legs of heelless boots. Women wore at least 2 dresses over their shirt, the outermost of which (the prototype of the letnik) was shorter than the under dress, with narrow and long sleeves adorned at the cuff. On their shoulders they would wear a woven or fur mantle. Their headwear was a type of povojnik, over which they would wear a veil and wide capes in the form of a maphorion. Small crowns of various shapes were also worn.

Color also corresponded to the social status of the wearer. Peasants are shown in white or light-colored clothes, the colors of undyed canvas or wool. Costume of the middle class are usually colored, but each item is of a single color, with only the hemline, collar and cuffs decorated with a band of another color, often yellow. The costumes of the wealthy are shown made from fabrics with strong geometric ornament. Men’s hats served as important ethnic and regional markers.

The pictorial works of art considered here provide us the opportunity to hypothesize to some extent costume as it existed in the 15th century, and to identify some differences by class, age and profession. The picturesqueness of clothing as it existed in that day and their obvious social differences become apparent.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Savaitov, P.I. Opisanie starinykh russkikh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo ubora: izvlechenie iz rukopisej arkhiva Moskovskoj Oruzhenoj palaty. St. Petersburg, 1865. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Artsikhovskij, A.V. Drevnerusskie miniatjury kak istoricheskij istochnik. Moscow, 1944. |

| ↟3 | Artsikhovskij, A.V. Miniatjury Kenigsbergskoj letopisi. Leningrad, 1932. |

| ↟4 | Artsikhovskij, A.V. «Odezhdy.» Ocherki russkoj kul’tury XIII-XV vv.: v 2 ch. Part 1. Moscow, 1969, pp. 277-296. |

| ↟5 | Rabinovich, M.G. «Odezhda russkikh XIII-XVII vv.» Drevnjaja odezhda narodov Vostochnoj Evropy: Materialy k ist.-ethogr. atlasu. Moscow, 1986, pp. 63-111. |

| ↟6 | Zhilina, N.V. «Tipologia zhenskogo golovnogo ubora s ukrasheniami vtoroj poloviny XIII-XVII v.» Zhenskaja traditsionnaja kul’tura i kostjum v epokhu Srednevekov’ja i Novoe vremja. Issue 2. Moscow-St. Petersburg, 2012, pp. 38-65. |

| ↟7 | Rjabtseva, S.S. Drevnerusskij juvelirnyj ubor: osnovye tendentsii formirovanija. St. Petersburg, 2005. |

| ↟8 | Stepanova, Ju.V. «Drevnerusskij kostjum po pis’mennyjm i arkheologicheskim istochnikam X-XV vv.» Drevnjaja Rus’. Voprosy medievistiki. 2010 (4), pp. 84-92. |

| ↟9 | Prokhorov, V.A. «Materialy dlja istorii russkogo kostjuma.» Russkie drevnosti. 1871 (6). pp. 65-74. |

| ↟10 | Kuz’mina, O.V. «Kostjum novgorodskogo bojarina (konets XIV-nachalo XV veka)» Rekonstruktsija kostjuma srednevekov’ja: sb. mater. Fashion-bloka XIV Mezhdunar. festivalja “Zilantkon-2004.” Kazan’, 2005, pp. 48-63. |

| ↟11 | Kuz’mina, O.V. «”Oblechjotsja v krasnye, i v chervlenyja, i v bagrjanyja odezhdy” (drevnerusskaja verxnjaja muzhskaja odezhda XIV-XV vekov).» Stratum Plus. 2010 (6), pp. 269-276. |

| ↟12 | Kuz’mina, O.V. «Detskij kostjum russkogo crednevekovogo goroda.» Integratsija arkheologicheskikh i etnograficheskikh issledovanij. Kazan’/Omsk, 2010 (1), pp. 346-350. |

| ↟13 | Kuz’mina, O.V. «Zhenskij novgorodskij kostjum v XIV-XV vv.: obzor istochnikov.» Vestn. Pskov. gos. universiteta. Ser. Sots.-gumanitar. i psikhol.-ped. nauki. 2013 (2), pp. 138-145. |

| ↟14 | Filimonov, G.D. «Ikonnye portrety russkikh tsarej.» Vestnik Obschestva drevnerusskogo iskusstva pri Mosk. publ. muzee. 1875 (6-10), pp. 35-66, 1-ja. |

| ↟15 | Nazarevskij, V.V. Iz istorii Moskvy 1147-1913: Ocherki. Moscow, 1914. |

| ↟16 | Schepkina, M.V. «Izobrazhenye russkikh istoricheskikh lits v shit’je XV veka.» Trudy GIM. Pamjatniki kul’tury. Iss. 12. Moscow, 1954. |

| ↟17 | Podobedova, O.I. Miniatjury russkikh istoricheskikh rukopisej: k istorii russkogo litsevogo litopisanija. Moscow, 1965. |

| ↟18 | Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971. |

| ↟19 | jeb: See my translation of this book here: https://rezansky.com/medieval-russian-embroidery-majasova-1971/ |

| ↟20 | Popov, G.V. Zhivopis’ i miniatjura Moskvy serediny XV-nachala XVI veka. Moscow, 1975. |

| ↟21 | Smirnova, E.S. Zhivopis’ Velikogo Novgoroda, XV vek. Moscow, 1982. |

| ↟22 | jeb: You can see an image of this icon in the gallery below. |

| ↟23 | Popov, pp. 319, 519 |

| ↟24 | jeb: An opashen’ was a long-skirted coat with short, wide sleeves, typically worn in the summer. The word is derived from raspakhnut’, meaning “to fly open.” |

| ↟25 | jeb: An outer cloak, literally, a “dragging” cloak. |

| ↟26 | cf. Popov, illus. 1. |

| ↟27 | jeb: You can see an image of this icon in the gallery below. |

| ↟28 | cf. Smirnova, pp. 298, 503. |

| ↟29 | jeb: You can see an image of this icon in the gallery below. |

| ↟30 | Smirnova, pp. 246, 440 |

| ↟31 | Filimonov, p. 65. |

| ↟32 | Artikhovskij, «Odezhda», p. 289. |

| ↟33 | jeb: An epancha is a long, wide cloak with a hood. Typically, epanchi are sleeveless. The word comes from Turkish yapyndzha, and the garment was borrowed from the Arabian East. |

| ↟34 | Kuz’mina, «Zhenskij novgorodskij kostjum…», p. 141. |

| ↟35 | Artsikhovskij, «Odezhda», p. 291. |

| ↟36 | Artsikhovskij, «Odezhda,» p. 283. |

| ↟37 | jeb: See image in the gallery below. |

| ↟38 | Saburova, M.A. «Drevnerusskij kostjum.» Drevnjaja Rus’: byt i kul’tura. Moscow, 1997, p. 103. |

| ↟39 | jeb: Unfortunately, this source does not include an image of the manuscript in question. |

| ↟40 | Prokhorov, p. 65. |

| ↟41 | Radzivilovskaja letopis’: faks. vosproizvedenie rukopisi, khranjaschejsja v B-ke Ros. akad. nauk. St. Petersburg/Moscow, 1994. 2 Volumes. |

| ↟42 | Podobedova, pp. 50-53. |

| ↟43 | Artsikhovskij, «Drevnerusskie miniatjury…», p. 28; «Odezhda», p. 277. |

| ↟44 | Prokhorov, p. 68. |

| ↟45 | Sizov, V.I. «Miniatjury Kenigsbergskoj letopisi.» Izvestija ORJaS. Vol. 10, book 1. St. Petersburg, 1905, pp. 1-50. |

| ↟46 | Podobedova, p. 55. |

| ↟47 | Podobedova, pp. 64, 68. |

| ↟48 | Kuz’mina, «Detskij kostjum…», p. 269 |

| ↟49 | Podobedova, p. 68. |

| ↟50 | Podobedova, p. 69 |

| ↟51 | Prokhorov, p. 69. |

| ↟52 | jeb: See a sample image of Princess Ol’ga in folio 29, in the gallery below. |

| ↟53 | jeb: See the example in folio 215, with Princess Ulita holding her husband’s severed arm. |

| ↟54 | Zhilina, pp. 43-48. |

| ↟55 | Zhilina, p. 43. |

| ↟56 | Zhilina, p. 47. |

| ↟57 | Podobedova, p. 72. |

| ↟58 | Prokhorov, p. 68. |

| ↟59 | Prokhorov, p. 68. |

| ↟60 | Popov, pp. 52-55. |

| ↟61 | «Khudozhestvennye sokrovischa Moskovskogo Kremlja. Moscow, 1984, folio 115. |

| ↟62 | Filimonov, p. 47. |

| ↟63 | Tereschenko, A.V. Byt russkogo naroda. Part I. Moscow, 1997. |

| ↟64 | Rabinovich, p. 69. |

| ↟65 | This watercolor image can be viewed online here: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-543e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99#/?zoom=true |

| ↟66 | Piltz, E. Trois sakkoi byzantins: analyse iconographique (Vol. 17). Upsalla, 1976. |

| ↟67 | Majasova, plate 27. |

| ↟68 | jeb: See my translation of this source’s description of the podea on my blog. |

| ↟69 | Efimova, L.V. Kostjum v Rossii: XV – nachalo XX veka: iz sobr. GIM. Moscow, 2000, p. 10. |

| ↟70 | Epokha parsuny: russkij istoricheskij portret: kat. vyst. 26 dek. 2003 g. – 31 maja 2004 g. Moscow, 2003, pp. 38-39. |

| ↟71 | Majasova, p. 20. |

| ↟72 | Majasova, p. 20. |

| ↟73 | Schepkina, Izobrazhenie russkikh istoricheskikh lits… |

| ↟74 | Schepkina, p. 16. |

| ↟75 | Schepnik, p. 14. |

| ↟76 | Schepkina, p. 16. |

| ↟77 | Majasova, description for plate 27. |