The 10th century rise of Kiev as a centralized power in Rus’, the official state acceptance of Christianity in 988, and the accompanying closer ties with Byzantium brought about a tremendous amount of change in Rus’ in the 10th-11th centuries. Between that time, and when the Mongol invasion caused a great stagnation of Russian culture starting around 1240, Russian artisans built their first major cathedrals of wood, and then later acquired the ability for monumental buildings in stone. The article I’ve translated below provides an in depth look at this time period, using examples of buildings from Kiev, Novgorod, Chernigov, and other cities from the Kievan Rus’ lands to demonstrate how social, religious, and political forces influenced the development of ecclesiastic architecture throughout this time period. It provides a number of great images of Russian churches from early Rus’ (which I’ve also expanded upon, where possible), and touches on how the palaces and stately homes of the Rus’ upper classes mirrored the architectural styles in use for churches and cathedrals.

Architecture of Kievan Rus’

A translation of Воронин, Н.Н. «Зодчество Киевской Руси.» История русского искусства. Том I. Москва, 1953, с. 111-154. / Voronin, N.N. “Zodchestvo Kievskoj Rusi.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1953, pp. 111-154.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. Images labeled “jeb:” were added by me. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://yadi.sk/d/3W8-vpPd3WbPuC. ]

The most important theme in the early history of Russian architecture [Rus. зодчество / zodchestvo, specifically Russian architecture from the pre-Mongol period (9th-13th cent.)] is the question of wooden architecture in the 10th-11th centuries, of which no examples has survived to our time. We may make guesses about it only on the basis of ethnographic parallels, the epics, indirect descriptions from written sources, et.al. These data allow us to say that, in addition to the preserved ancient examples of stone architecture and archaeologically-studied semi-earthen dwellings and huts of townsfolk, there also existed a rich and sophisticated world of buildings of various types: churches, palaces, and fortresses, built by Russian carpenters. Considering this, it is possible to understand how extremely rapidly Russian builders learned stone architecture, as well as its stormy development.

The wooden architecture of the eastern Slavs, perfected over the course of centuries, attained a high level in the 10th century. It was widely used as a form of folk art, owned by almost everyone. Ibn Fadlan (early 10th century) saw, as he was sailing into Bulgar on the Volga, how Russian merchants built for themselves “large houses of wood,” in which they lived together with their living goods – slaves.[1]Puteshestvie Ibn-Fadlana na Volgu. Moscow-Leningrad, 1939, p. 79. Another author, Ibn Miskawayh (10th century) recalls how even on distant campaigns, the Rus’ would not part with their carpentry tools: “they hang from themselves a large part of the tools of an artisan, consisting of an axe, saw, and hammer, and that which is similar.”[2]Jakubovskij, A. “Ibn-Miskavejkh o pokhode Rusov v Berdaa v 943-944 gg.” Vizantijskij vremennik. 1926 (XXIV), p. 65. Russians, having perfectly mastered these simple wooden tools, not only built dwellings and fortresses, but also pagan sanctuaries, carved idols from wood, and in the end, created the first Christian churches, which appeared in Kiev well before the official adoption by Rus’. Ibn Rust (10th century), describing the semi-earthen dwellings of the Slavs, with their overlapping “sharp-pointed” roofs, was already able to compare them with the “rooves of Christian churches.”[3]Garkavi, A. Skazanija musul’manskikh pisatelej o slavjanakh i russkikh. St. Petersburg, 1870, pp. 266-267.

Naturally, the residents of the northern, forested regions of Rus’ were particularly famed for their artwork, in particular the Novgorodians, famed for their skilled carpenters. Kievan Prince Svyatopolk’s general mocked the the Novgorodians who came with Yaroslav: “Are you carpenters? We’ll put you to work on our mansions!”[4]Laurentian Chronicle, under year 6524 (1016). From this we can conclude that the Novgorodians build not only for themselves, in the North, but also in the South, in Kiev. When Vladimir Svyatoslavich fortified the Steppe borders of the Kievan lands with fortresses, they were build by both local residents, as well as “men” from Northern climes: “And [Vladimir] gathered the best men from the Slovenes, and the Krivichi, and the Chyudi, and the Vyatichi, and all settled cities.”[5]Laurentian Chronicle, under year 6496 (988). This cooperation of Northern and Southern building arts created a famous commonality of technique and artistic principles. Just as typical for woodworking in the 10th-11th centuries was the absence of specialization by type of building: one and the same woodworker would have built huts and mansions, churches and fortress walls with towers. This is why the secular and religious, civil and military buildings had so much in common, and did not differ in their specific forms of expression. From this, it is also possible to imagine that general ideas about beauty in buildings were more or less the same for both wealthy homes as they were for churches, usually sharply contrasting those of the poorer, primitive homes of artisans and peasants.

Due to the continual threat of warfare, particular emphasis was put on fortress architecture, a form of urban planning. By the 11th century, there existed specialized companies of “city builders” [Rus. градник, gradnik] and “builders of fortresses” [Rus. огородник, ogorodnik]. A mastery of composition of wide architectural ensembles and love for simple and stately monumental forms developed for the building of these urban fortifications. Based on the latest (13th century) indications from written sources,[6]See the tales on the building of Galitsko-Volynskaja Rus’ in the Hypatian Chronicle, under the years 1259 and 1276., we may suppose that in earlier times, the building of cities was systematic and well-thought-out work by the city-builders and the royal powers, who selected the most artistically and defensively-advantageous locations. The architect would carefully study the location, and would raise the city walls and towers in harmony with the relief and landscape of the area. This consistency of architecture with the landscape and the the military and engineering requirements determined the city’s appearance and justified its fashion.

It’s natural to think that this high artistic quality was shared as well by other buildings erected by Russian carpenter-homeowners. According to data from the chronicles,[7]Rzhiga, V. “K istorii drevnerusskogo zhilischa.” Trudy Gos. Istoricheskogo muzeja. 1929 (5), p. 23. in addition to the simplest forms of log houses, consisting of a single room or perhaps with an attached inner porch, there also existed a more complex type of dwelling consisting of three parts: the main room or istobka, a heated room; an intermediary room or vestibule [Rus. сень, sen’], and a purely ceremonial section [Rus. клеть, klet’] used for summer living. In wealthy homes, this system became more complex and ornate, and the dwelling became two-story and was abundantly decorated with both interior and exterior paintings and carvings.

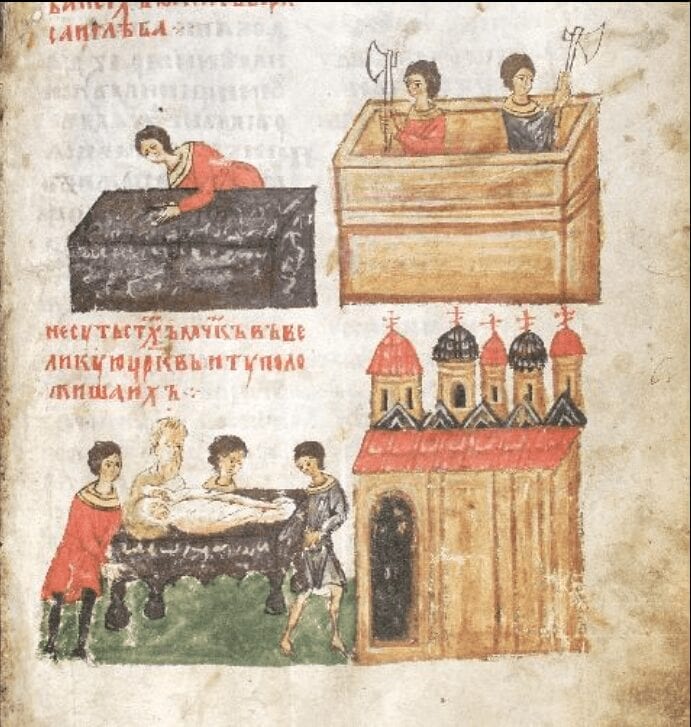

The sources report there were complex and picturesque ensembles of well-to-do wooden mansions, with golden-domed towers which, undoubtedly, were true works of art. Such was the Kievan court of Princess Ol’ga, which was called the “towered” court thanks to its picturesque towers. A miniature from the 15th-century Radziwiłł Chronicle, which copied a drawing from the early 13th century, depicts Ol’ga’s tower as a tall, square, two-story tower with a hipped roof (see Illustration). Just as a gate with its towers played an important role in the image of a city, so too was this central tower [Rus. повалуша, povalusha] a key element in the composition of a wealthy home.

Most likely, the first wooden churches in 10th-11th century Rus’ had the same appearance. The earliest depiction of a wooden church on the margin of the parchment in the 12th-century Pskov Charter depicts the characteristic shape of a tall, pillar-like wooden church, covered with a steep roof (see Illustration). It is possible that Thietmar of Merseburg’s recollection that in early 11th-century Kiev there were more than 400 churches may have been the result of an abundance of towered buildings, including not only churches, but also civil buildings.

The oaken Cathedral of St. Sophia, built in Novgorod in the late 10th century and destroyed by fire in the 11th century, according to the Chronicle, had “around thirteen peaks.” Of course, we may never know with full certainty what this most ancient of Novgorod the Great’s cathedrals looked like, but it is possible to imagine that the wooden church had a complex and original combination of 13 towers: around a tall central “pillar”, most likely, there were grouped 8 more pillars lesser in size, constituting the main nine-part square of the layout, to which four lowered side towers (3 vestibules and an altar) were attached.[8]Brunov, N. “K voprosu o samostojatel’nykh chertakh russkoj arkhitektury X-XII vv.” Russkaja arkhitektura. Moscow, 1940, p. 122; Novgorod I Chronicle, under the year 6557 (1049). In this manner, the thirteen peaks of this complex church formed, in a way, a stepped pyramid, growing in height toward the center. An indirect confirmation of this idea can be seen in the depictions of multi-peaked churches in Northern embroidery, which preserves a number of vestigates of deep, possibly pre-Christian, antiquity.[9]Voronin, N. “K kharakteristike drevnejshego zodchestva vostochnykh slavjan.” KSIIMK. Iss. XVI, p. 99, illus. 31.

A bit later, around 1020-1026, Yaroslav the Wise was reinforcing the cult of the first Russian saints Boris and Gleb, and invited to build a church over their graves in Vyshgorod not Greek architects, but a local architect Mironeg, who also built a wooden five-domed church: “build me a grand church, with five domes, and cover and decorate all of it with beauty.”[10]Shakhmatov, A. and Lavrov, P. “Sbornik XII v. Moskovskogo Uspenskogo sobora.” Chenija v obschestve istorii i drevnostej rossijskikh. 1889, vol. 2, p. 31. It appears that this church was a combination of 5 pillar-like churches. Not long after, the architect Jan-Nikola built in Vyshgorod by royal command a second wooden Boris and Gleb Church “with one peak.”[11]ibid. This does not preclude the possibility that these wooden churches may have had open porches and galleries [Rus. опасание, opasanie] encircling their ground floors.

Clearly, in similar wooden churches from the 10th-11th centuries, organically related in their tower-shaped appearance to the city fortress and with the picturesque mansions of the upper class, independent Russian tastes and preferences about the beauty of a church were already reflected in the earliest periods of Russian architecture. It is also possible to think that old pagan traditions and their love of polychromatics and carving were alive in its decorative style.[12]Streznevskij, I. “Arkhitectura khramov jazycheskikh slavjan.” Chtenija v obschestve istroii i drevnostej rossijskikh. 1846, vol. 3, p. 46. It may be that this is exactly why in the 11th century, wooden architecture from the pagan past and Christian present was differentiated by the term съграждати / s’grazhdati ([to build a] temple, city, church) from the new, brick architecture which used the word зьдати / z’dati, meaning to build from зьд / z’d , the clay from which bricks were made.

We need to keep all of this in mind when evaluating the real impact that the Byzantine architects invited by Vladimir to Kiev had on the history of Russian architecture: they arrived in a country which had its own developed culture, artistic traditions, and cadres of builders.

The general reasons and historical conditions which lead Kievan Rus’ to receive Christianity from Byzantium.[13]jeb: See https://rezansky.com/forces-contributing-to-the-development-of-kievan-rus-artwork/. Greek Orthodoxy had multiple centuries of experience in shackling living human thought, raising man in blind faith to the divine establishment and the eternal power of the ruling class, to instill obedience under the threat of “divine judgement” and torment beyond the grave. In this system of ideas and politics planted by the church, monumental architecture played a highly visible role, having achieved a high technological and artistic perfection. The emperor and patriarch precisely assessed the impact of majestic and lush architectural constructions, decorated with exquisite works of figurative art and the blinding wealth of ceremony and ritual on the consciousness of the people. This led Byzantine art to be carried out with great ideological saturation. Nowhere in Europe at this time was artwork so developed and refined as in Byzantium, and nowhere was it so clearly imbued with the governing ideas of church and state. As a result, the powerful impact of Byzantine artistic culture had an impact on the art of many regions of feudal Europe; for example, the art of 10th-11th century Germany was in many ways directly indebted to Byzantine tradition and its artisans, while Italy had its own local Byzantine schools, amongst which Venice and Sicily stood out, where in the 11th-12th centuries they erected churches richly decorated with Byzantine-style mosaics.

The great effectiveness of Byzantine ecclesiastic art was just as well understood by the princely-boyar upper classes of Kiev. The large, wide-open interior space of Greek stone churches, sparking with refined decorative art, was sharply different from the first wooden churches built in 10th-11th century Kiev; the theatricized rituals of worship created a deep impression. In this way, the adoption of Orthodoxy, in addition to providing the ruling class of Kiev the strongest weapon for strengthening the feudal system and asserting its power, also brought Rus’ into the front lines of Europe’s forward-looking architectural tradition, Byzantium’s building culture. This laid the foundation for the development of monumental stone architecture in Rus’. The pace and independence of this process in its earliest stages shows that Russian culture of this time was able not only to quickly perceive the high and complex tradition of the Greeks’ building art, but also to creatively rethink and rework it.

The Byzantine masters brought with them to Rus’ fully established principles of religious architecture. The primary type was the cross-domed church. The base of such a church was a square, broken into 9 cells by four columns bearing the weight of the dome; this space under the dome had adjoining rectangular cells, covered by semicircular vaults, with the walls along the main axes segmented by lesenes [Rus. лопатка, lopatka, “shoulder-blades”]. From the east, semi-circular altar spaces, apses, were attached to the church. From the west, the church was sometimes extended by three additional sections, and the number of pillars increased, as a result, to 6. This would serve as the support for a second story, the gallery [Rus. хоры, khory], under which the the columns sometimes were replaced by a wall with arches, separating the narthex-porch from the church. Sometimes the choir would continue over the wide narthexes, forming a letter “П”.

The external appearance of the template clearly expressed its inner construction; the walls’ lesenes corresponded to pillars, the walls ended in circular zakomary,[14]jeb: The semicircular or keeled ends of the outer wall segments on medieval Russian orthodox churches. These mirrored the shape of the immediately adjacent inner vault., accurately depicting the shape of the semi-circular arches which capped the building. The walls were not plastered, but rather were covered with layers of thin brick and stone on a pinkish solution of lime mixed with crushed brick, creating a unique two-color banded facade which was enlivened by the play of light and shade in the rows of decorative two-layer niches. The interior decoration of the church was quite opulent, with mosaic and fresco murals joining the decoration of the floors, columns, and panels of polished colored stones and marble, and so forth.

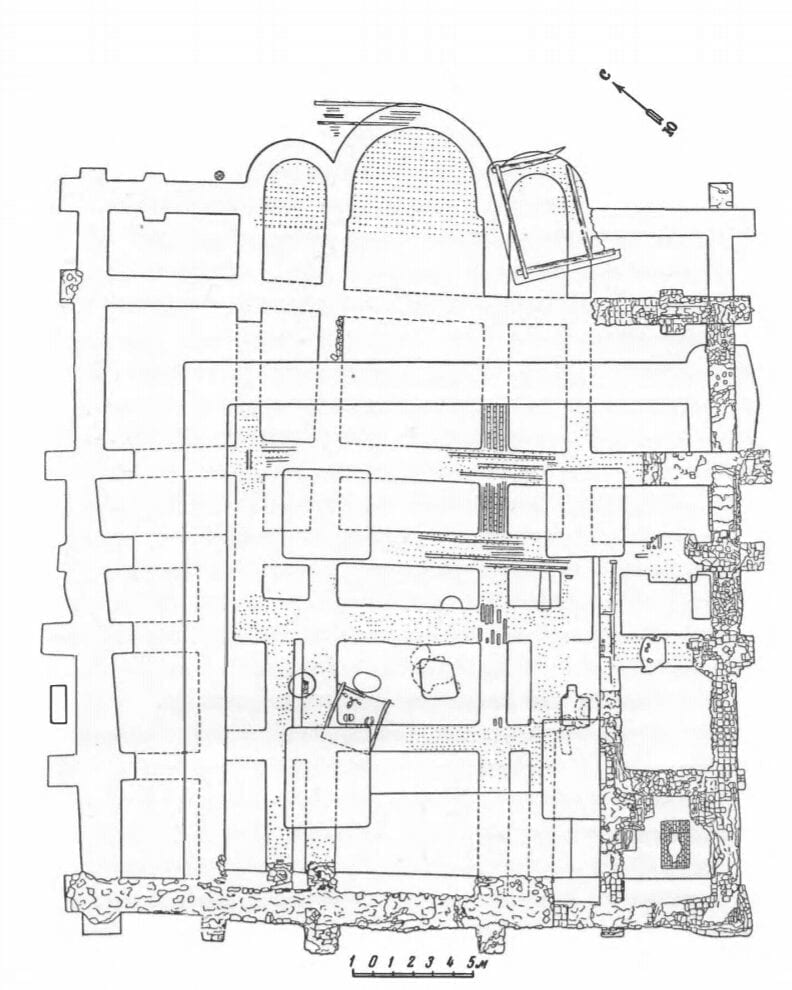

The Chronicles tell us that when he accepted Christianity, Vladimir “decided to build a stone church to the holy Mother of God, and sent for artisans from the Greek.”[15]Hypatian Chronicle, under year 6499 (991). In 996, the church was completed and called the Church of the Tithes, on account of Vladimir granting a tenth of his princely wealth to its construction. This church, the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin (989-996) has not survived; it was destroyed in 1240 when it was stormed by the Mongols, burying in its ruins the last denizens of the city – Kievans – who were hiding within it and its vaults. As a result we only know its plan and individual details of its decoration discovered during archaeological excavations (see Illustration).[16]Excavations of the location of the Church of the Tithes was begun during the archimandrite of Peter Mohyla (b. 1596 – d. 1647). Exhaustive study of the monument was carried out by an expedition of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. Cf. Karger, M. Arkheologicheskie issledovanija drevnego Kieva. Kiev, 1950, pp. 45-140. The walls of the church were almost completely disassembled, to the very foundation; only parts remained, based on which we may determine the layout. The excavations established interesting details of the construction technology; for example, at the base of the walls, there was a kind of flooring made of wooden planks, fastened with pegs and covered in lime mortar and a layer of masonry.

The church plan is characterized by a significant geometric irregularity, most likely tied to the site being broken down using a measuring cord. The original Church of the Tithes was a three-naved cross-domed church, with a narrow vestibule to the west; as early as the beginning of the 11th century (around 1039), it was expanded with open galleries around the sides, becoming a vast five-naved cathedral. It is possible that the galleries were slightly lower than the main body of the cathedral, which would have given its silhouette a stepped appearance.[17]Sherotskij, K. Kiev. Kiev, 1917, p. 81. It seems that the church had many domes,[18]This is confirmed by a later source, Spisok gradom Russkim, located in the chronicles: “the stone Church of the Tithes of the Holy Mother of God had around 25 domes….” (Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej, vol. VII, p. 240). with a complex silhouette vaguely reminiscent of the wooden churches like Novgorod’s St. Sophia’s. The walls of the church façade were broken up by lesenes and were enlivened by a series of semi-circular two-stage niches and tall windows.

Voevoda, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

During the excavations, they found fragments of colored slate, marble details, mosaics, and frescoes which demonstrate the luxurious inner decoration of this first Russian stone church, was later, even in ruins, had a reputation which led to it being nicknamed “the marble church of the most pure Mother of God.” The collection of wall panels included incrustations of porphyry, and the choir parapets were made from slabs of red slate and Proconissian marble[19]jeb: A coarse-grained white marble, typically with grey streaks, mined on Marmara Island in Turkey. This stone was also used to decorate much of the St. Sophia cathedral in Istanbul. with carved decoration. The choir arcade leading into the center nave of the church stood upon columns which were quadrifoliate in cross-section. The floors of the church were particularly fine. In the altar space, the floor was covered with slabs of white marble and red slate laid in a checkerboard pattern; in the places where the priests would walk or stand during the service, paths and rectangular, mosaic-patterned “rugs” (omphalia) were placed. The mosaics were created using pieces of natural stone: various colors of marble, green, white, dappled, and lilac porphyry, slate, and mosaic smalt. It appears that the floors of the central nave were just as richly decorated. In the side apses off the altar area and in the side naves, the floors were covered with glazed, multicolored tiles of various sizes and shapes, most likely creating some kind of complex design.[20]Karger, M. “K voprosu ob ubranstve inter’era v russkom zodchestve domongol’skogo perioda.” Trudy Vserossijskoj Akademii khudozhestv. Vol. I. Leningrad-Moscow, 1947, pp. 17-20. The altar area was separated from the rest of the church by a light, stone barrier. The precious implements of the church consisted of icons, utensils, and crosses of Greek make, in part brought by Vladimir from Korsun. The wealth and beauty of the décor of the Church of the Tithes reflected the tastes of Russians who were brought up on wooden buildings decorated “with all kinds of beauty.”

This main cathedral of Vladimir’s Kiev was not the only stone building; excavations have uncovered the foundations for stone palatial buildings nearby, characterized by opulent decorative details. Near the western entrance to the Church of the Tithes, the foundation was discovered of a stone building, built of granite, limestone and brick, containing remnants of what the Chronicle called “the house of a domestik“[21]A domestik was the head of the church choir. To the south of the church, they found the walls of a large masonry house with signs of opulent decoration. To the north and east of the church they also uncovered signs of stone buildings made from brick and red quartzite, and fragments of marble details, Majolica floor slabs, mosaics and frescos, and round panes of window glass. A significant quantity of burnt logs indicates that the upper floor of this building was, it seems, made of wood.

The signs of how this princely house was constructed indicate that it had extensive halls, or gridnitsy, intended for the prince to feast with his household or to hold princely councils. Based on indirect evidence, these were large single-story rooms, with rooves supported by pillars or columns. The epithet “bright”[Rus. светлый, svetlyj] which always accompanies mentions of gridnitsy in the byliny attests that they were well lit. Gridnitsy were always open and available, regardless of whether the prince was present or absent.[22]Rzhiga, op. cit., p. 8.

The Church of the Tithes and the royal represented the central architectural ensemble of the city, located atop the Kiev Hills. It appears to have been open and merged freely into Babin Torzhok Square, decorated with an ancient bronze quadriga[23]jeb: A classical form of statue depicting Apollo in a two-wheeled chariot, pulled by four horses. and possibly other statues captured by Vladimir in Kherson.[24]We can conjecture this from a verse in the Peryaslavl-Suzdal’ Chronicle: “And he took two Greek kapischi of the holy Mother of God, made of marble.” Letopisets Perejaslavla-Suzdal’skogo. Moscow, 1851, p. 31. Here the chronicler, it seems uses the word kapische to mean “statue” or “idol”. This city center conformed architecturally to the main stone gates of the city wall (discovered during excavations of the so-called Batu Gate).

It’s necessary to emphasize that these individual stone buildings did not define the appearance of Kiev around the time of Vladimir. The testimony mentioned above by Thietmar of Merseburg that early 11th-century Kiev had 400 churches shows, it seems, the presence as well of wooden churches which created a strong impression on this foreign observer. Likewise, along with the stately stone houses of the upper class, we should imagine a large quantity of simpler, wooden buildings. This combination of stone and wooden architecture was characteristic of its appearance.

The sumptuous buildings of the Church of the Tithes and the stone palaces of the princely upper class surrounding it, and the large wooden and, undoubtedly, still just as richly decorated mansions of the boyars, by their size, material and splendor of their inner and exterior decoration, would have presented a stark contrast with the dwellings of the Kievan lower classes, citizens, and artisans. These were small, smoky, dark semi-earthen buildings, with sod rooves, similar to burial mounds, which would not have reached far from the ground. The new, stone architecture would have heavily and weightily emphasized the deep abyss separating the feudal lords from their subjects. Someone living in a fragile, gloomy sod cabin, entering into the mammoth Church of the Tithes, stepping upon its marble or Majolica floors and contemplating its enormous space filled with light and luxurious mosaics and frescoes, would have sensed his insignificance before the might of the prince who ruled Kiev, his boyars, and their households. Emphasizing the role of this “quantitative” moment for the ideology of the Middle Ages, in particular with regards to architecture, K. Marx wrote: “With their enormous dimensions, these colossi act materially upon the soul. The soul feels suppressed by their weight, and this feeling of suppression is the origin of awe.”[25]Marks, K. and Engel’s, F. Sochinenija. Vol. 1, p. 140.

Stone building was not limited to Kiev in the first half of the 11th century: Yaroslav the Wise’s brother Mstislav, prince of Chernigov and Tmutarakan, built stone cathedrals in those cities; Yaroslav continued to construct magnificent buildings in the sprawling city of Kiev; his son Vladimir constructed a stone St. Sophia’s in Novgorod on the site of the prior wooden cathedral, destroyed by fire; and a bit later, in the second half of the 11th century, a stone St. Sophia’s was build in Polotsk. This continuation of stone architecture in distant regions of the Kievan lands accompanied the development and strengthening of the feudal system and broadening of princely power and the church, which henceforth would unite the swords of war and “of spirituality” in the battle against uprisings of the urban lower classes and peasants against the quickly growing feudal oppression and exploitation. But, this process itself suggests the start of feudal fragmentation and the weakening of the centralized role of Kiev and the growth of other feudal cities which would soon become centers of independent feudal principalities. For this reason, even the first architectural monuments in these cities show local characteristics, complicating and modifying the original Kievan patterns.

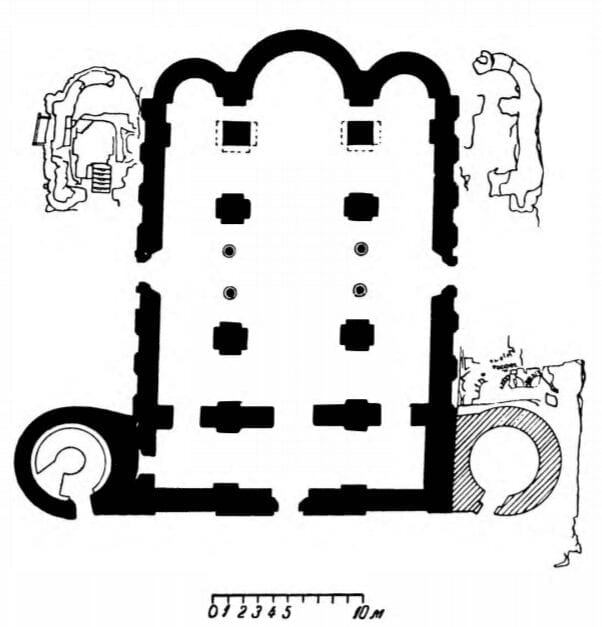

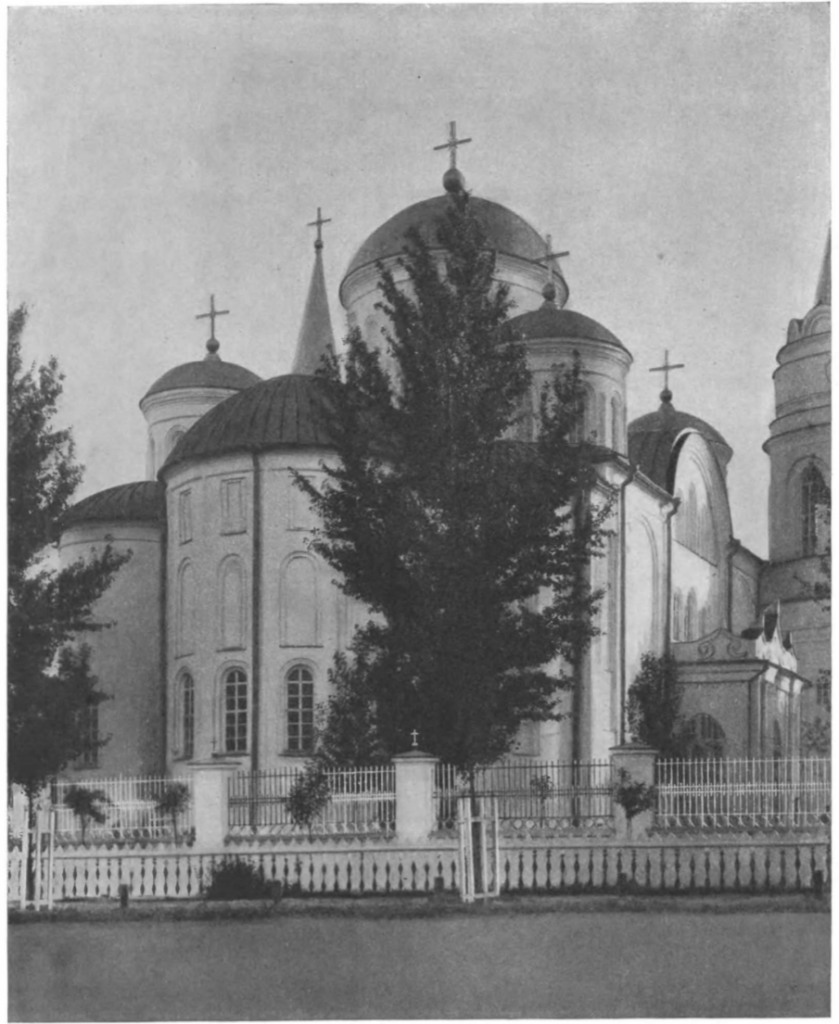

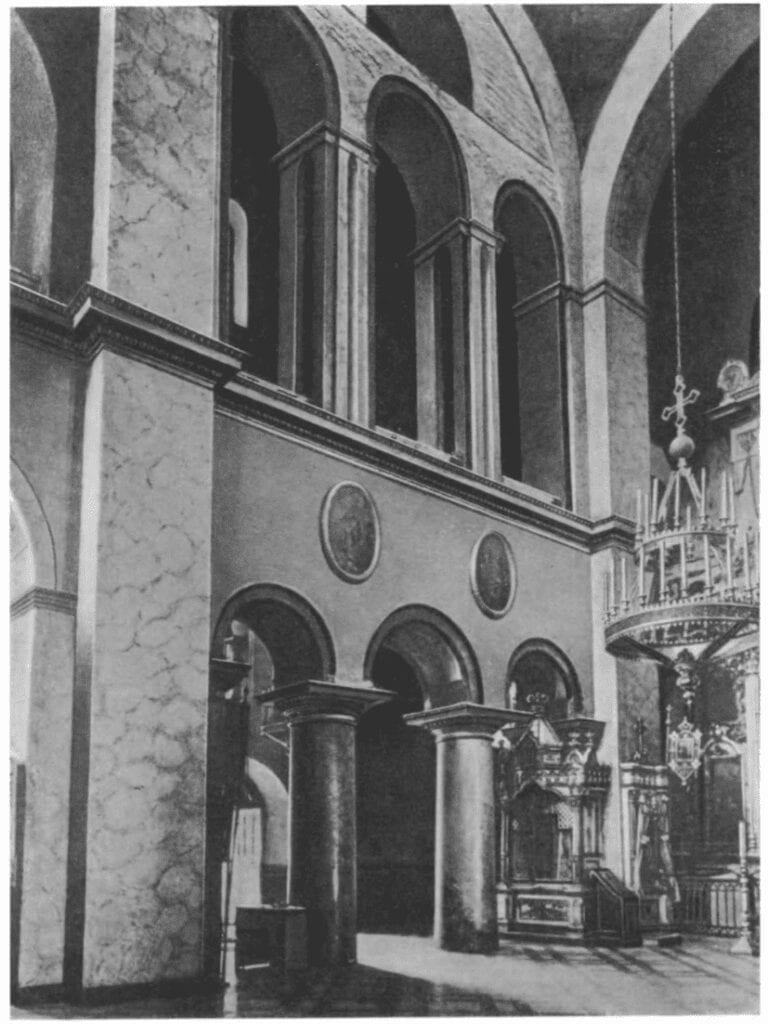

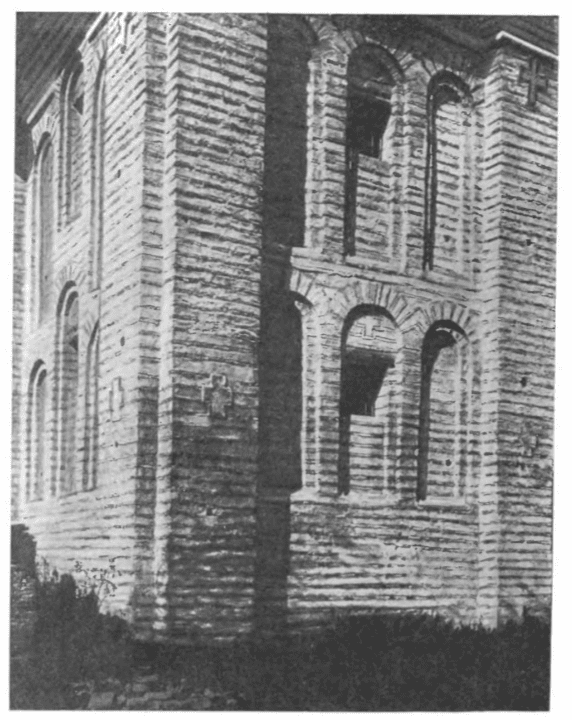

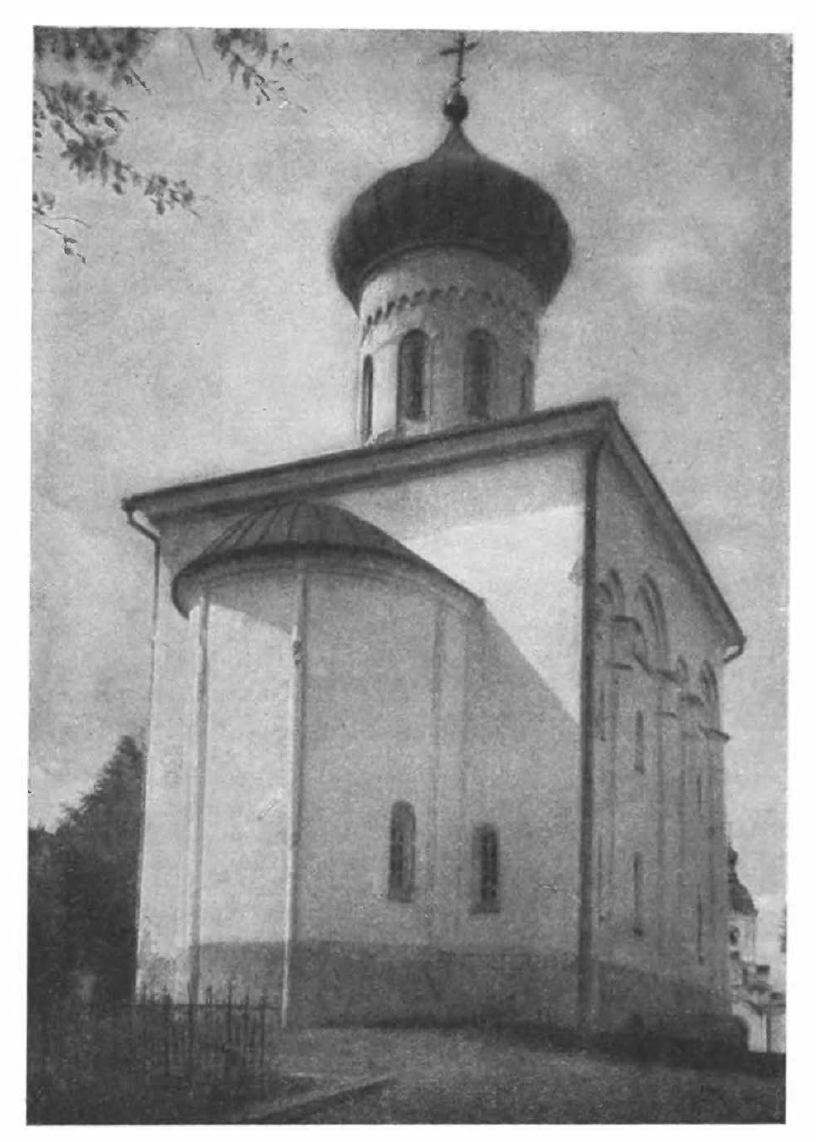

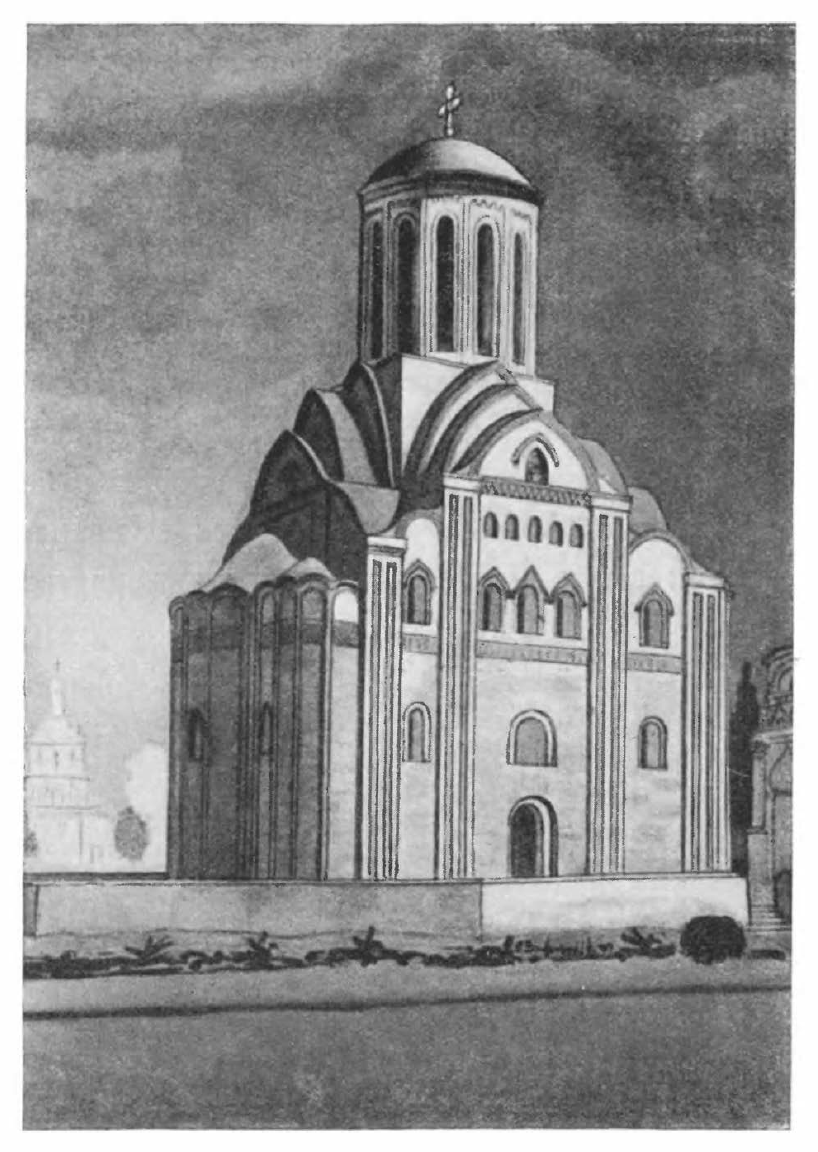

The Savior-Transfiguration Cathedral in Chernigov (see Illustrations) was started by Mstislav and completed by Yaroslav (around 1036). Similar to the original Church of the Tithes, this church was a large three-naved cathedral with three altar apses topped with zakomary. Its tranquil body is topped by five cupolas, which are round in cross-section with faceted corners. The originally exposed masonry of the outer walls gave the church a characteristic, two-toned and striped appearance. A notable feature of the church is its mighty cylindrical tower attached to the northwest corner, with a staircase leading to the choir. The location of the tower, built in the 18th century, was originally home to a small baptistery, and off the western corner, several small family tombs for the members of the royal family (see Illustration) were built in the 11th century. These parts of the building violated the strict isolation of the cross-dome body of the church, but the tower stairway likened the cathedral to a luxurious dwelling of a deity. The interior expanse of the church was richly illuminated; the side wings of the choir, separated from the expanse under the dome by three arcades, were supported by marble columns (see Illustration). The floor was finished with carved slabs of slate encrusted with colored smalt. The walls and vaults were covered with frescoes. In its rich splendor, this Cathedral of the Savior-Transfiguration was only barely outshone by the central church of Rus’, Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral.

Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral stood in the center of the city, which had grown far beyond the city limits from Vladimir’s time. Yaroslav the Wise parted its borders, and build new earthen ramparts with stone towered gates, and decorated the city with new buildings. The Chronicles recall the start of this building: “Yaroslav built up the great city [Kiev], and his city had a Golden Gate, and he established the church of St. Sophia, for the Metropolitan, and he established the church at the Golden Gate to the Annunciation to the Blessed Mother of God, and he established the monasteries to St. George and St. Irina.”[26]Laurentian Chronicle, under the year 6545 (1037). The old city from Vladimir’s time became, as it were, the inner citadel of Kiev. Yaroslav’s constructions, as shown by these recollections of his building efforts, consciously tried to liken the Russian capital to Constantinople. The very idea is amazing in its boldness and clearly shows how the Principality of Kiev’s political and cultural power had grown, given that its capital kept competing with “Eastern Rome”.

The main gates of Kiev (1037), called “Golden” in emulation of the Golden Gates of Constantinople, survived to modern times as a set of ruins (see Illustration). Judging by old drawings, they consisted of a monumental arch, and combined defensive tasks with an artistic role as a ceremonial triumphal arch; it was completed by a Church of the Annunciation, which stood atop the gate. Those entering through the gate were presented with the prospect of Kiev’s main street. On either side stood the churches of the Monasteries of St. Irina (1037) and St. George (1037),[27]The question of the naming of these monuments is currently under review; for now, we call them according to scientific tradition. and beyond them rose the golden domes of the Cathedral of St. Sophia, surrounded by the stone walls of the Metropolitan palace.

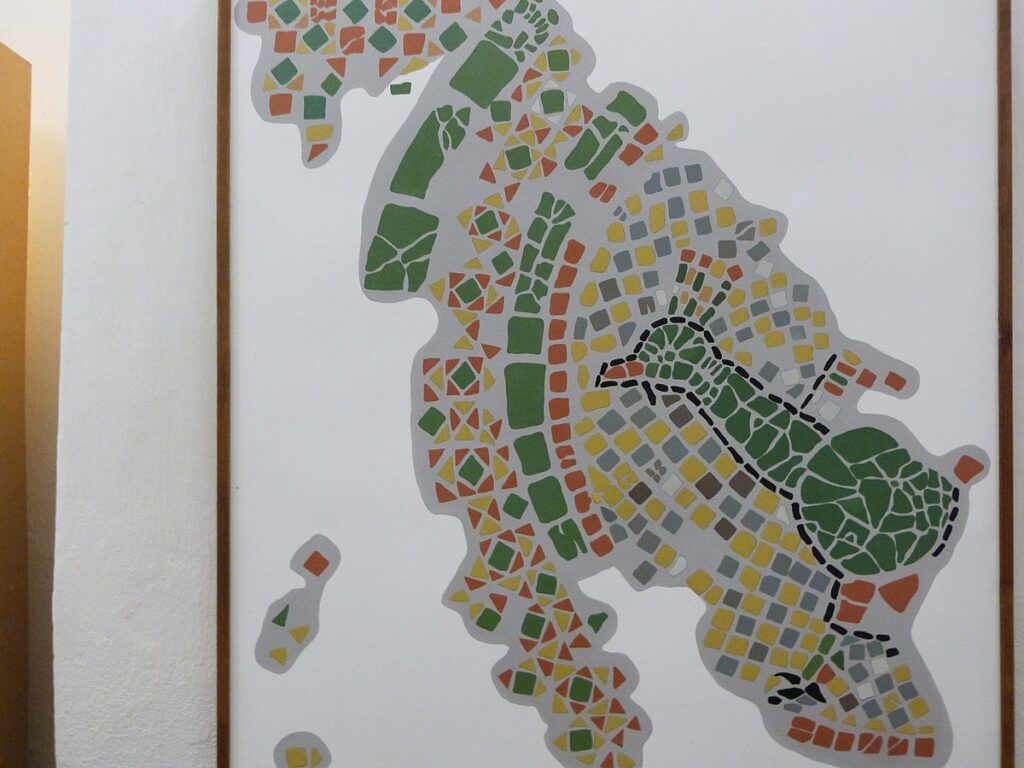

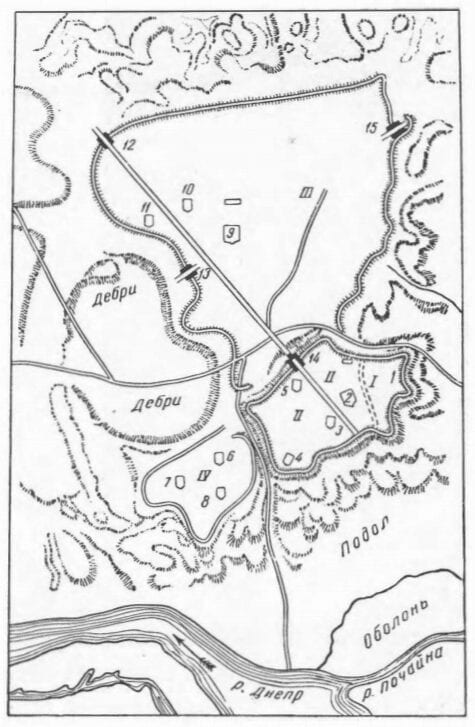

This new architectural center of Kiev, which replaced its original center of Babin Torzhok Square with its statues, the Church of the Tithes, and palaces, was planned quite deliberately and in full agreement with the architectural ensemble of the city (See map). The majestic complex of the three golden-domed churches of Sts. Sophia, Irina and George was built such that it stood at the intersection of the roads from three of the city gates: the Lyad, Lviv and Golden Gates. At the same time, from St. Sophia’s ran the way to the stone arch of the original city gate from Vladimir’s time, beyond which one could see the peaks of the Church of the Tithes. The beautiful design of the new city ensemble, no doubt, represented a huge urban planning experiment by Russian architects.

I – 8th-10th century settlement; II – Vladimir’s city; III – Yaroslav’s city; IV – Mikhajl’s city

1 – “temple”; 2 – Church of the Tithes; 3 – Yanchin Monastery; 4 – Vasilievskaya Church (Church of the Three Saints); 5 – Feodor’s Church; 6 – cathedral of St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery; 7 – St. Dmitry’s Church; 8 – St. Peter’s Church; 9 – St. Sophia Cathedral; 10 – St. George’s Church; 11 – St. Irina’s Church; 12 – Golden gate; 13 – Lyad gate; 14 – Batu gate; 15 – L’vov gate.

[jeb: Translation for Russian terms on the map:

дебри – thickets; Подол – Podil district, the lower city; Оболонь – Obolon district; р. Днепр – Dneiper River; р. Почайна – Pochayna River]

As a result of Yaroslav’s constructions, Kiev became one of the most beautiful cities of Europe. Its beauty deeply stirred contemporaries. In one of his sermons, Metropolitan Hilarion told Yaroslav: “you have crowned Kiev with majesty,” and addressing the deceased prince Vladimir, said: “Rise up… See the city shining with magnificence, see the churches flourishing… see the city we illuminate with icons of the saints, sparkling, and fragrant with thyme, and resounding with praise and divine songs to the saints.”[28]”Sermon on Law and Grace” by Metropolitan Hilarion. cf. Gudzij, op. cit., pp. 59-60.

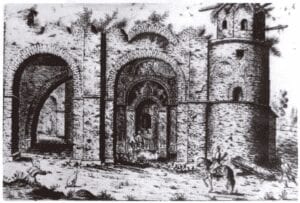

The central monument of Yaroslav’s Kiev and largest work of Kievan Rus’ art, St. Sophia’s cathedral has survived to our time in a completely distorted, almost unrecognizable form. It has suffered from fires, destruction, rework and repairs. By the 17th century, St. Sophia’s was in a dilapidated state: it’s picturesque ruins were captured in 1651 in a series of exquisite paintings by the Dutch painter Abraham van Westerfeld, who was in the retinue of the Lithuanian hetman Janusz Radziwiłł.[29]Smirnov, Ja. “Risunki Kieva 1651 g.” Trudy XIII arkheologicheskogo s’ezda v Ekaterinoslave. Vol. II, Moscow, 1908.

During the 17th-19th centuries, the cathedral was repeatedly “overhauled,” having received a series of accompanying buildings and a characteristically baroque appearance, making it even more difficult to judge its original appearance. This complex question has as yet not been completely resolved, and serves as the subject of ongoing research.

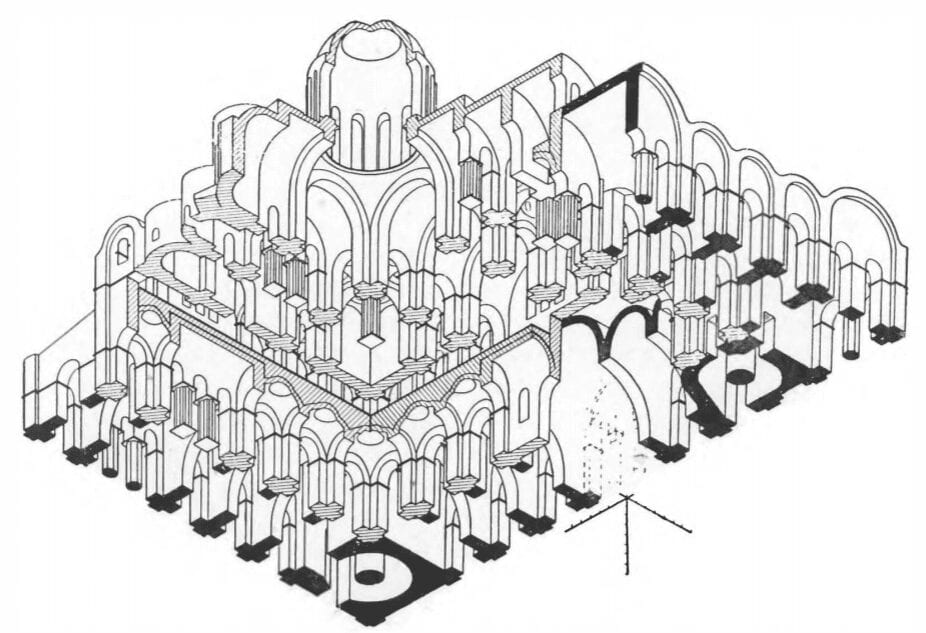

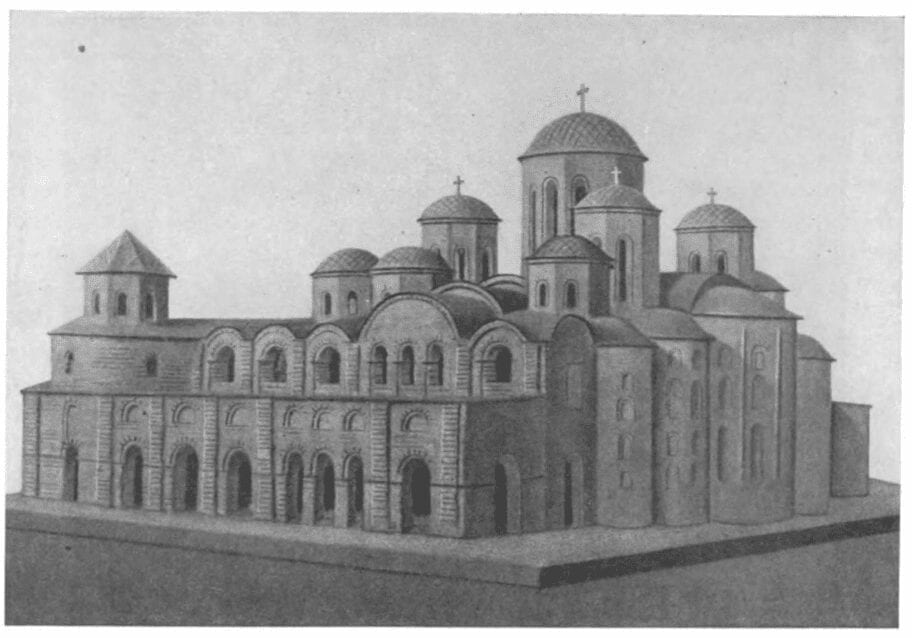

In contrast to the Church of the Tithes and Chernigov’s Savior-Transfiguration Cathedral, St. Sophia’s was fundamentally a broad (37 x 55 m), five-naved cross-domed church, with five apses and a clearly-defined wide cross of the central naves. A huge twelve-windowed dome stood above their intersection, with twelve smaller domes located at the corners of the temple body – four on each of the western corners, and two each on the eastern corners (see Illustration).

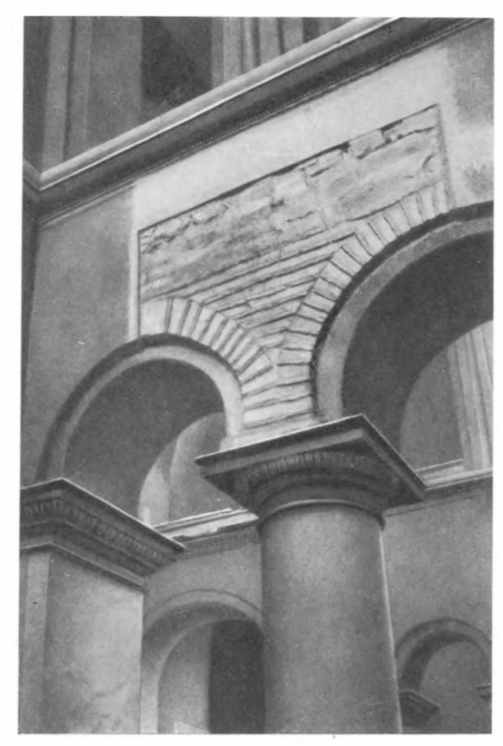

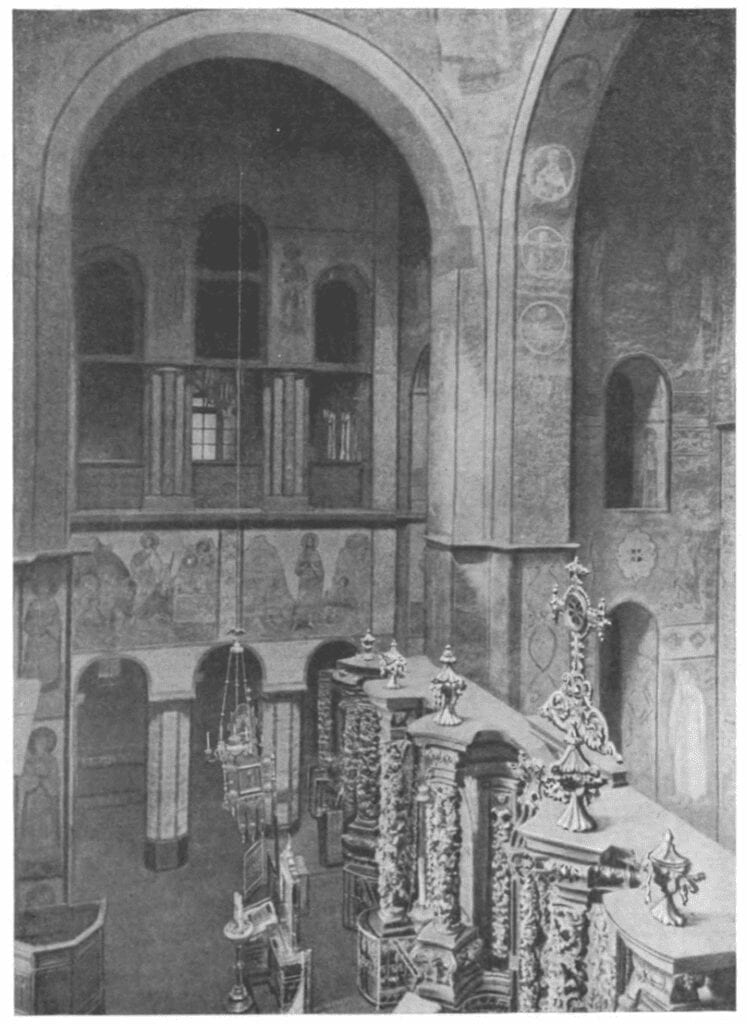

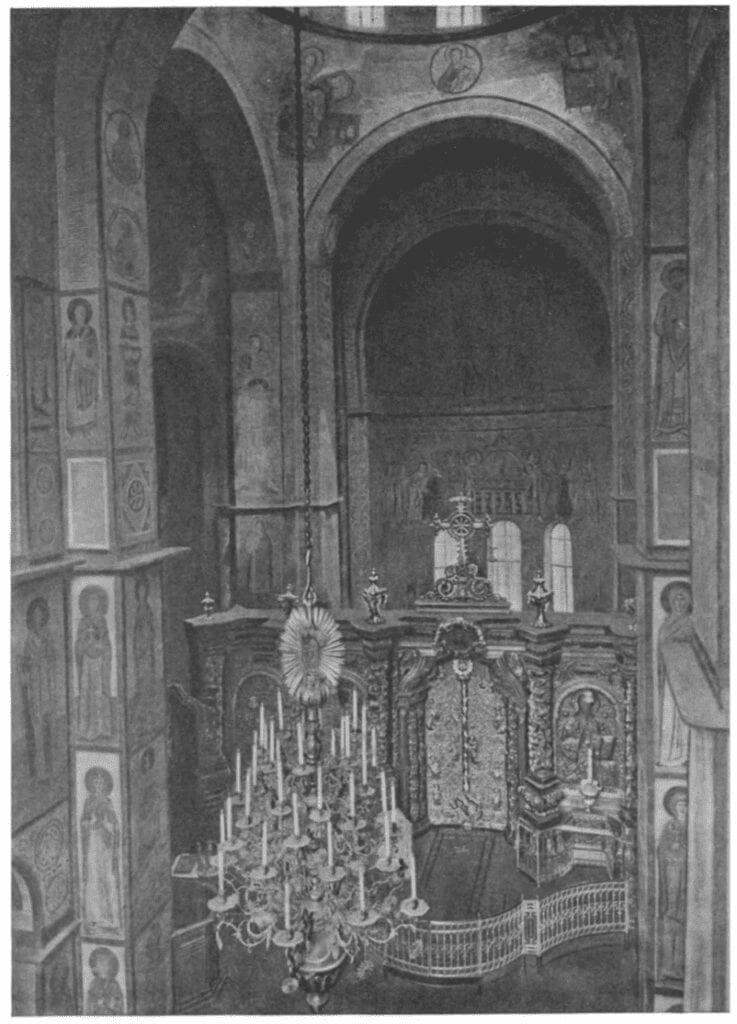

The eastern pairs of domes covered the altar space, while the western ones covered the wide choir, which spanned the entire western side of the church and the ends of the branches of the central cross. The choirs opened into the central expanse via three arcades, which were echoed from below by three arches which rested upon octagonal pillars and held up the main vaults of the choir (see Illustration).[30]The arcades beneath the choir on the western side collapsed in the 17th century and were not rebuilt during the 1686 restoration; the support bases were found during M.K. Karger’s 1939 excavation.

The central expanse of the church was surrounded by a single-story open gallery, to which was attached originally a single round tower with a staircase to the choir, located to the south-west.[31]Archeological studies by M.K. Karger found mosaics on the stairs from this staircase which were similar to the design of the church mosaic, suggesting that the tower and central church were built around the same time. Later, the gallery was expanded to a second story, the choir was expanded, and the building was surrounded on three sides with a wider single-story open gallery, and a second tower and staircase on the south-west corner. A notable design feature of the outer gallery are its quarter-round arches serving as flying buttresses. In both its original appearance and after this enlargement, the cathedral was characterized by the integrity of its consistent architectural design: the body of the church grew step by step toward the central dome (see Illustration). The mass of the cathedral rose above the low gallery, its vaults of its central naves served as another step, leading to the central dome; the same movement increased through the placement of the twelve domes in the corners of the church: small ones on the periphery, larger ones between them, and the central dome. Likewise according to this principle, the central apse was larger and taller, and the others’ size decreased outwards.

The consistency of the final appearance of the church should not be assessed using the later additions, as there were two different construction enterprises involved, the latter of which changed or violated the ideals of the former. In fact, the church was expanded in an even more emphasized version of the pyramid-like form that defined its original appearance. It’s possible to suppose that this widened variation of the composition with two towers was envisioned even at the original stage, but that it was only gradually realized. At first only the heart of the church was completed, the façade of which would be covered by later expansions.[32]It is interesting that the later Gustynskij chronicle, talking about the building of this church by Yaroslav, also mentions at the same time about his building “her two gilded towers” (Gustynskij chronicle, year 1037). Grabovs’kij, S. and Aseev, Ju. “Dosdizhenija sofij Kijv’skoj.” Arkhitekturni pam’jatniki. Kiev, 1950, pp. 27-48. We would this see this curious architectural characteristic of medieval building again a bit later, for example when we become familiar with the history of the building of the Bogolyubovsky Palace.

In its original form, St. Sophia’s was an exceptionally complete and deeply unique building, embodying the full power of the artistic view of its builders. The galleries with their open arcades obscured the large building’s base in their shade, giving the impression that it was standing upon thin pillars. This impression was strengthened by the two-color nature of the walls, the decorative niches around the altar apses animated by chiaroscuro, and the numerous window openings.[33]It is curious that some of the apse niches intended for windows were placed at the request of the mosaicists who decorated the walls.

The western façade of St. Sophia’s Cathedral was flanked by two towers completed, like a fortress, by hipped gilded domes. These emphasized the ideas of statehood and grandeur in the image of Yaroslav’s cathedral. Circular staircases ran within the towers, which the royal family and courtiers would use to reach the choir when attending church services. From the choir space, they would have had an exquisite view of the magnificent and solemn rites (see Illustration below). It has been suggested that the towers may have been attached directly to the neighboring palaces. At the top of one of the towers, the ambassador from Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, Eric Lassote (1594), was shown a room where supposedly the princes would meet with their boyars in antiquity; the location of the decaying galleries, moreover, was where the townspeople would have attended veche meetings. A small baptistery was built (17th cent.) next to the southern tower.

In the stately rhythm with with the mass of the cathedral rose like a pyramid and its characteristic thirteen domes, which distinguished it from smaller Byzantine examples, it is possible to see the impact the principles of wooden architecture had on the builders of this Kievan church. St. Sophia’s deeply original composition and form no doubt show that Russian architects worked alongside the Greek, and introduced much that was new into the appearance of this central church of the Kievan principality. They were buried in the cathedral, and the memory of their unmarked graves was still popularly remembered even in the 16th century; the aforementioned Erik Lassote was shown “a place inside the church where the artisans who planned and built the church were buried.”[34]Sbornik materialov dlja istoricheskoj topografii Kieva, p. 18.

St. Sophia Cathedral’s interior was no less magnificent. Past the partial shade of the arcades that surrounded the church, the churchgoer passed through polished marble portals into the cathedral. At first, the relatively low arches of the vast choir stretched over his head and covered the side naves, then opened out into the central space of the cathedral through the graceful triple arcades. The powerful cross-shaped pillars, which broke up the interior into multiple cells, established its complexity and opulence: when entering the church, the viewer would have seen a succession of various picturesque perspectives in the light-flooded central space, drawing attention away from the twilight that reigned under the choir arches. The effect of this inner space was further enriched by the variety and splendor of its decorative elements: mosaics, frescoes, carved and polished stonework, bas relief, majolica and incrustations were used by the architects with unsurpassed skill. Under the churchgoer’s feet, the cold “carpet” of the sparkling floor stretched out, striking the eye with a variety of designs and decorations. As opposed to the Church of the Tithes, where the floors were mosaics using pieces of natural semi-precious stone, St. Sophia’s floors were covered in tiles of mosaic smalt which were either laid directly into mortar, or were encrusted into slabs of red slate. Sparkling stone covered the lower part of the walls and columns, twinkling in the intersecting rays of light from the candles in the polycandela.[35]jeb: Large decorative chandeliers representing the stars in the firmament. From Greek, singular polycandelon, Rus. хорос, khoros, or паникадила, panikadila An ornate mosaic painting separated the space under the dome from the altar, the main parts of the church interior, from a ritual point of view.

The short, most likely marble, altar barrier would have barely separated the altar space, in the depths of which, running along the walls of the apse, there was seating for the clergy, with the luxurious metropolitan throne standing in the center. Above them ran horizontal rows of mosaic figures of the church fathers, and the apse dome had a majestic depiction of the Holy Mother in prayer. The Annunciation scene over the eastern pillars connected the mosaics in the altar space with the enormous image of Christ Pantocrator in the central dome.

The opulence of the monumental decorations of St. Sophia’s Cathedral was reflected by the wealth and variety of church utensils, vessels, tabernacles, and other accessories of worship, the beauty of the precious clergy vestments, and the veils and podeai which decorated the icons. The inner décor of the cathedral merged into a single whole with its architectural forms, emphasizing their expressiveness and logic. St. Sophia’s, as with other contemporaneous buildings, was a coordinated assembly of all forms of art and was, in this way, an indivisible synthetic whole. Its unity was defined by an organic subordination of all branches of art to architecture, building the image of the temple using all artistic means.

Praising Yaroslav’s deeds, Metropolitan Hilarion said of St. Sophia’s Cathedral: “[Yaroslav] created this house of God, great and holy, in his wisdom, for the holiness and sanctification of your city, decorating it with all kinds of beauty: gold, and silver, and precious stones, and valuable vessels. This church evokes wonder and admiration in all surrounding nations, for there is hardly another such church in all the semi-dark lands from east to west.[36]”Sermon on Law and Grace” by Metropolitan Hilarion. cf. Gudzij, op. cit., p. 59. Even in the late 16th century, when St. Sophia’s lay in picturesque ruins, it instilled a great impression on those who saw it. “A great many agree,” wrote Bishop Vereschinskij, “that in all of Europe there are no churches that in their grandeur or grace stood higher than those of Constantinople or Kiev.”[37]Petrov, N. Istoriko-topograficheskie ocherki drevnego Kieva. Kiev, 1897, p. 137.

It would seem that the same splendor and wealth also characterized the churches of the first monasteries in Rus’, those of Sts. Irina and George, built by Yaroslav around the same time as St. Sophia’s. In their layout, they were similar to St. Sophia’s. The remains of towers in the corners attest to the existence at their western end. During excavations of the churches, slabs of polished slate from the walls’ facings, remains of colored majolica and mosaic floors, and other forms of expensive decoration were found.

Yaroslav’s architecture of Kiev and his St. Sophia’s Cathedral directly influenced the Cathedrals of St. Sophia in Novgorod and Polotsk, which were built (with a few differences) in imitation of the Kievan example (see below).

Let us look at the question of the master architects who build the oldest examples of Russian stone architecture which we have reviewed, and their origins. The architectural forms of the Church of the Tithes, as well as the aforementioned Chronicle, both clearly attest to Vladimir’s call for Greek architects.[38]Laurentian Chronicle, under year 6497 (989). The main three-naved core of the Church of the Tithes was the most pure example of Byzantine churches in Rus’, as yet lacking the more complex church features like towers, staircases and galleries, which were characteristic of Yaroslav’s later buildings. However, it is undoubtedly the case that the Greeks found in Kiev entirely favorable conditions which allowed them to meet the needs for the complex process of monumental stone construction. They also found a highly developed technique of artwork, and ready cadres of builders able to quickly master new techniques and artistic principles. As a result, these alien architects became figures of Russian culture.

Yaroslav’s time is absent of any mention of Greek architects being invited for his planned grandiose rebuilding of Kiev. Unique traits similar to the precepts of Russian wooden architecture become stronger in the buildings of this time. We mentioned these traits above in the buildings of Chernigov and Kiev, including the appearance of terem-style[39]jeb: A terem was the upper story of a upper-class home or palace, usually with a pitched roof, used by the women of the household as living quarters. Teremy also existed in towers and in fortresses like the Moscow Kremlin. Here, I presume the author is referring to the room at the top used for meetings, as mentioned by Lasotte above. towers serving as entryways into the choir, which take their origin from the canopy-towers and teremy of wooden housing architecture, the use of “outbuildings” to the main building of the church as associated service buildings, such as baptistery and shrines, and the significant transfer of the thirteen-dome style, known from Novgorod’s wooden St. Sophia’s Cathedral, and the pyramidal composition of Kiev’s St. Sophia. We should also note that by its measure, Kiev’s St. Sophia’s far surpassed the Byzantine five-naved cross-domed churches. It was the most majestic and grandiose church of its type.

Without a doubt, Russian builders worked on Yaroslav’s projects, some part of which, it is possible, also took part in Prince Vladimir’s buildings. It is hardly likely that, having had the opportunity to erect those monumental stone buildings which caught the Chroniclers’ attention, then left their new profession until Yaroslav’s project. When Yaroslav began to build the church to St. George, it is said:

“…there were few men to work on it; and having seen this, the prince asked of Tiun[40]jeb: The name, presumably, of one of Yaroslav’s advisors.: ‘”Why are there so few men working on the church?” And Tiun said: “It is an imperial undertaking, but the people are afraid of labor, and hiring them is difficult.”

And the prince said: “If that is the case, then this shall I do.” And he ordered his officials to load carts with kuny[41]jeb: A kuna was a medieval monetary unit used in Rus’ in the 10th-15th centuries. By the end of this period, the value of a kuna had stabilized around that of 2 grams of silver, or 1/25 of a hryvnia. and take them to the Golden Gates; and to announce to the throng of people, “Let any man earn a kuna per leg per day.”

And quickly there was a multitude of workers.[42]Quoted in Solov’ev, S.M. Istorija Rossii. Vol 1: Obschestvennaja pol’za. p. 245, item 4.

From this story, we can see that Kiev had many builders working in various professions who were needed for the building projects and ready for hire. Undoubtedly, among them were independent architects who helped carry out Yaroslav’s construction.

The technique of building had several features which were tied to their new conditions. For example, wood was used to a significant degree in building. The Church of the Tithes had a unique foundation: it rested on a wooden deck made from logs, joined with pegs, and filled with lime mortar. The choir side wings in Chernigov’s Savior-Transfiguration Cathedral were supported not by stone vaults, but on wooden ones. The parts which remained visible, however, were diligently painted red to match the color of slate. In addition to the simple flat bricks made by Russian potters, architects also used their masonry natural types of stone; for example, in the Chernigov Savior Cathedral, they used a yellow sandstone.

An analysis of these oldest Russian churches allows us to establish a very simple method for laying out the plan of their foundation using cord and pegs directly at the construction site. This type of plan for the Chernigov Savior Cathedral and the Church of the Tithes reveals significant deviations from geometrical shapes and right angles that have been cut off, caused by uneven pulling of the measuring cord. The plan of the cross-dome church was likewise laid out at the construction site. Its originally geometrical elements defining the scope of the building as a whole and of its sections were the square of the arches under the dome, and the circle of the cupola. Their derivatives (the diagonal of the square, a half-circle, etc.) determined the size for building the altar apse, the columns, the widths of the naves, and the widths of walls and vaults. This same simple method also determined the high points of the composition. This ideally clear and practically simple method, crystalized from many centuries of practice by Byzantine artisans, was quickly mastered by Russian architects and became a practical basis for their work.[43]Afanas’ev, K. “Pro proportsional’nist’ drev’norus’koi arkhitekturi XI-XII st.” Arkhitekturni pam’jatniki. Kiev, 1950, pp. 49-54.

These monuments of the 10th-11th centuries represent a single stylistic group, characterizing the oldest stage in the history of Russian architecture. This was a time of first contact and competition between stone Byzantine architecture and the traditions of Russian wooden architecture, giving a bright originality to these eldest of stone churches. This era of Vladimir and Yaroslav, so full of deep contradictions between old and new and of the battle between pagans and Christians, an era of the shining and complex culture of princely-era Rus’, identified the most important characteristics for the architectural style of the 10th-11th centuries.

In stone architecture, which served the church and princely power, two main types of building developed: the large urban cathedral, and the grand palace.

Characteristic were the enormous size of buildings, as sharply opposed to the dwellings of the masses, which were semi-earthen. All the means of artwork applied in the decor of these princely-church buildings reinforced the idea of the wide contrast between the ruling levels of Kievan society and the disenfranchised and enslaved citizens and peasants. The separation of the interior of the temple by the choirs where the prince and his associates would be seated, literally over the heads of those in prayer, clearly reflected the layers of the feudal hierarchy. This architecture, however, was as yet devoid of severe monastic spirit. Grandeur and wealth of decoration was characteristic for churches of this period: beloved and expensive gold vestments, enamel, and heavyweight patterned fabrics. The dynamism of the church’s mass, the two-toned nature of the facades enriched by the play of chiaroscuro, and the golden cupolas brought a spirit of festive splendor to its appearance. These church and state buildings, these churches and palaces, organically united with the urban landscape. The stately arcades of Sophia’s galleries would have united the cathedral with the surrounding space of the metropolitan fortress, while it’s steep-roofed stair towers resounded a powerful echo of the “gold-tipped” teremy and towers of the capital’s fortress walls.

Yaroslav the Wise’s death (1054) serves as a conventional border for the start of a new period in the life of medieval Rus’ and in the development of its culture and art. The feudal relationship which emerged over the course of the 10th-11th centuries was completely victorious.

In the 11th-12th centuries, the political map of the Russian lands changed: the large but fragile power of the first princes of Kiev gradually became increasingly fragmented. Over the immense territory of the Kievan principality, there arose numerous feudal principalities, each with its own capital, the growth of which left Kiev with only its faded glory: Kiev gradually became no longer all-Russian, but rather a local feudal center. Its political rivals, however, these principality capital cities, each attempting to imitate Kiev’s brilliance, would still yield to it. They were incomparably smaller than Kiev in size, their princes had limited material abilities, and their economic and political horizons were narrower and more segregated. Few of these cities enjoyed the same world renown as Kiev; only Novgorod the Great was even close.

Princely fortresses, boyar estates, and monasteries grew around and within the artistic and trade centers. Escalating class warfare, terrible urban and peasant uprisings, bloody rivalry between feudal lords – all of these determined the martial, fortified character of these feudal nests. They turned in on themselves, surrounded by the strong walls of their compounds which define the architectural style of the feudal city of the 12th-13th centuries. The very course of social relations took on a clear and consistent expression, anchored by all the norms of feudal law.

With this victory of feudal relations, the character of ideology and of religion itself changed: the Christianity of Vladimir’s time, which still contained much of pagan popular beliefs, turned into a religion of hermits and monks, permeated by asceticism. This new world view was characteristic not only for religious buildings, but also took over in princely-boyar circles. The Chernigov prince Svyatoslav Davidovich, who later took monastic tonsure in the Monastery of the Caves and received the name “Nikolai Svyatosha,” when leaving Kiev, “turned his back on Kiev and, as he said to his brethren: ‘…verily, my brothers, the vanity of its light and the beauty of its world.'”[44]Cited in: Ajnalov, D. “Kiev – Tsar’grad – Khersones.” Izvestija Tavricheskoj uchenoj arkhivnoj komissii. 1920 (57), p. 248. The aesthetic from Vladimir’s time seemed sinful and vain. These ideological shifts, tied to the intensification of the feudal exploitation and class warfare, would pose new challenges for architecture.

The new local princely dynasties arranged their capital cities, creating fortifications and their expensive residences. Each capital needed a central cathedral of a new style which was more modest than Kiev’s St. Sophia. The church reached into the layers of the urban and rural population and built small, “parish” in the cities and princely villages. The number of monasteries multiplied, with their own special requirements for the architecture of the monastery church and its ensemble of outbuildings. These new circumstances changed not only the typology, but also the very character of architecture, leading finally to an essential change in style. This process spanned from the late 11th century to the 12th century. In Kiev, this was complicated by the influence of older artistic tastes and skills, which quite clearly affected Kievan architecture from the late 11th century, tying it to architecture from the 10th-11th centuries.

These new artistic phenomena were associated first of all with the Kievan monasteries, which quickly grew in number and significance. They were generously supported by the princes, who promoted their construction. After Yaroslav founded the monasteries of Sts. Irina and George, his son Izyaslav I Yaroslavich (baptized as Dmitrii) founded the Dmitriev Monastery. In the mid 11th century, the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra[45]jeb: aka, the Monastery of the Caves. A lavra is a type of Eastern Orthodox monastery consisting of a cluster of cells or caves for hermits. was founded. In 1070, Prince Vsevolod Yaroslavich (baptized Mikhail) established the St. Michael the Archangel’s Vydubitsky Monastery. Svyatoslav Yaroslavich built his St. Simeon Monastery, the third member of the so-called “Yaroslav Triumvirate.” These monasteries had cathedrals which could compete with the enormous city cathedrals of Kiev and Novgorod. They were more modest than those in size and décor, and more severe and plain in artistic expression.

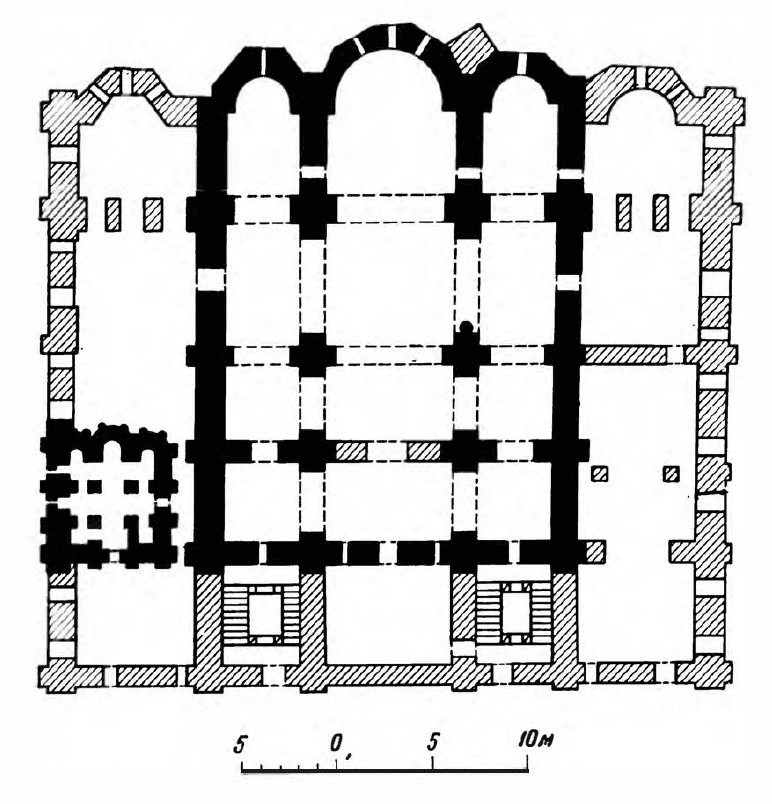

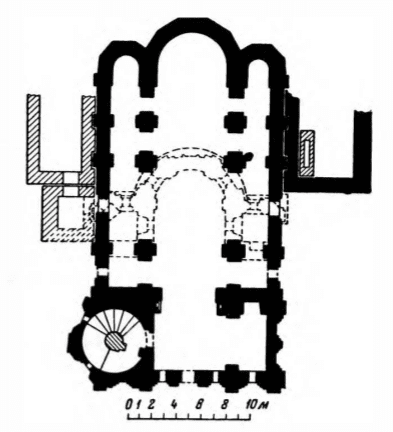

Plan for the Dormition Cathedral in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, 1073-1078.

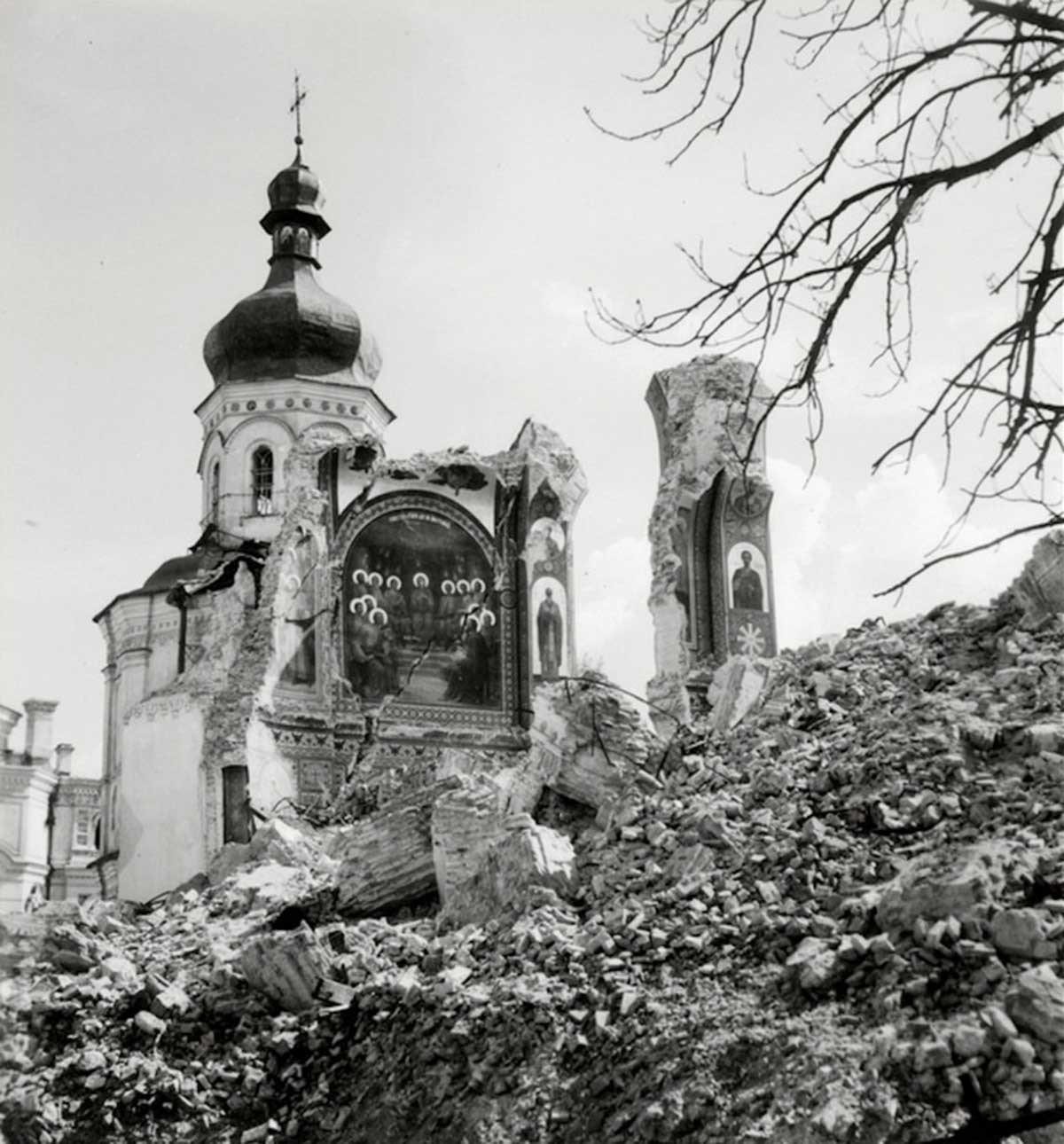

jeb: Ruins of the Dormition Cathedral in Kiev’s Monastery of the Caves, destroyed in 1941.

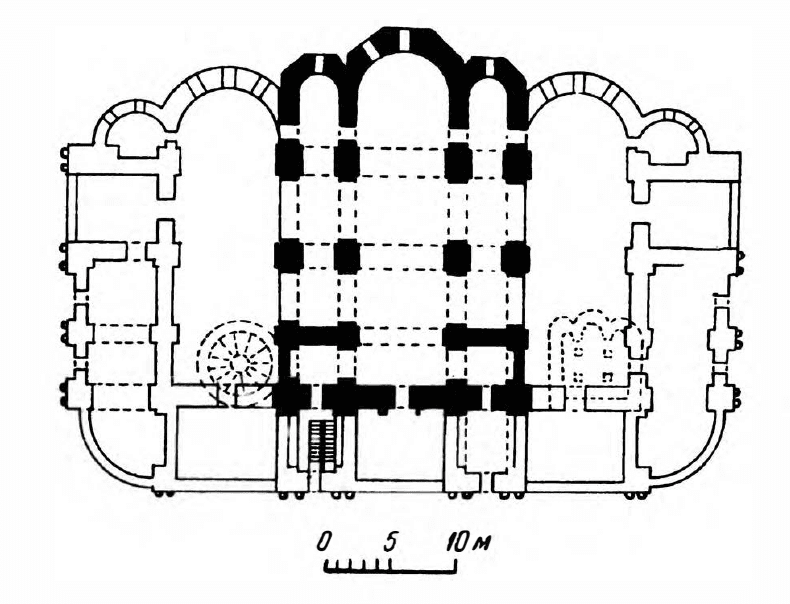

jeb: Present-day form of the Dormition Cathedral in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, rebuilt 1995-2000.

Деревягін Ігор, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The most characteristic of this type was the [Dormition] cathedral [aka Pechersky Cathedral] of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra [jeb: aka, Monastery of the Caves], founded in 1073-1078 by Prince Svyatoslav Yaroslavich. This monument was barbarously destroyed by fascists.[46]jeb: When this article was written, it was thought that Nazi Germany destroyed the church when they occupied Kiev in 1941. Later historians have accused the Soviet Army of destroying the church as part of the so-called Kreschatyk Explosions, a series of radio-controlled explosives which the Soviets left behind and set off once the Nazis had occupied the city. These explosions leveled much of the old city, and caused significant casualties among the occupying Nazi forces, as well as the resident Ukrainians. The church lay in ruins from 1941-1995, when a recently-independent Ukraine started to rebuild it. The new cathedral was consecrated in 2000.

The ancient foundation of this cathedral (see Illustration above) vaguely resembles the three-naved foundation of the Church of the Tithes. Its facades preserved the traditional system of decoration using a row of niches and are divided by flat lesenes. The northwest corner had a small attached cupolaed baptistery, built in the late 11th-early 12th century and similar to that from the cathedral in Chernigov. These features all speak vividly of the architectural traditions from the 10th-11th centuries. However, the stair tower, an expressive characteristic of churches from Yaroslav’s time, is absent, replaced (it seems) by a wooden staircase hidden between the cathedral wall and the baptistery. The interior of the church was also quite different. The faceted columns have been replaced by mighty cross-shaped pylons. The western quarter of the church has been sharply delineated from the main, four-column central expanse by a wall with arches. The interior has become more plain and severe. It was filled evenly but sparingly with light, not leaving behind spaces for picturesque interplays of light and shade. The decoration of the interior, however, was carried out in the old tradition. The altar was separated by a beautiful marble barrier, and mosaics and frescoes matched the richly patterned inlay floors. A 17th century Kievan chronicler still saw remnants of this decoration in “the great Pechersk cathedral,” and wrote that “all is beautifully decorated with golden mosaic, that is, gilt stone, as well as patterns and delightfully variegated colors, and with beautifully painted icons. The church dais [floor] was likewise sewn with various colors of stone in every pattern….”[47]Sinopsis. St. Petersburg, 1810, p. 92. New and old were intertwined in this cathedral, which was destined to become the “model” for many churches in the 12th century.

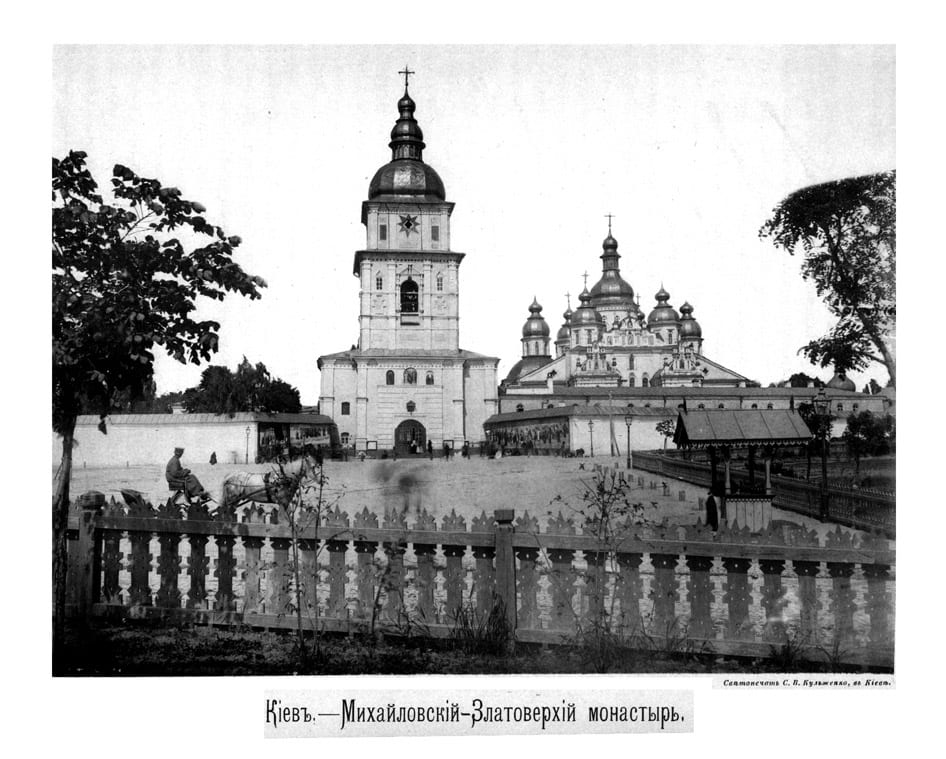

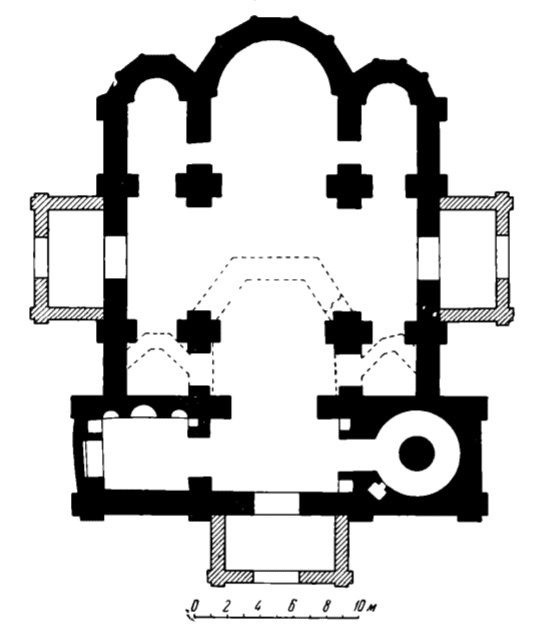

Very similar to the Pechersk cathedral was the church of St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery[48]jeb: also in Kiev. (see Illustration).[49]This cathedral has not survived to modern time.[50]jeb: The cathedral was demolished in 1930 by the Soviets, but was rebuilt in 1999. It had the same stylistic qualities, but retained more of the older features. At the northwest corner there was a monumental round stair tower, leading to the choir, while at the southwest corner was a baptistery. These details bring this cathedral closer to the composition of the Savior-Transfiguration cathedral in Chernigov. The most recent studies have determined that this cathedral, preserved under the name of St. Michael, was in fact the oldest cathedral in Dmitrievsky Monastery, dating not from 1108 (the date of another, lost cathedral to St. Michael), but the mid-11th century, when Prince Izyaslav founded the monastery in 1051. This reveals a great archaism in the architectural composition of the monument, as compared to Pechersky Cathedral. The altar-space mosaics and information about the luxurious floors, with mosaics and slabs of red slate encrusted with smalt which were just as lush as those in St. Sophia’s, attest to the princely tastes which contributed to the magnificent interior decoration.

A third monastic cathedral, in St. Michael the Archangel’s Vydubitsky Monastery (1070-1088), was built on a tall bluff over the Dnieper, and only the western part has survived. The eastern part was destroyed in medieval times due to erosion of the river bluff. Excavations have established that it was a large, eight-pillared church, which was unusually elongated along the longitudinal axis (see Illustration above). It’s six-pillared main body was extended by a wide porch, which led to the total of eight pillars. The eastern wall was extended by a number of tombs, resembling similar extensions on Chernigov’s Savior-Transfiguration Cathedral.[51]Karger, M. Arkheologicheskie issledovanija drevnego Kieva. Kiev, 1950, pp. 141-166. The formal stair tower leading to the choir was deprived by its builders of its independent architectural meaning: it has been pushed into the western porch, but not entirely, such that it still protrudes somewhat from the plane of the northern façade. The church was decorated with fresco paintings, and its floors were paved with slabs of slate encrusted with smalt and colored ceramic floor tiles.

Plan for St. Michael’s Vydubitsky Cathedral in Kiev, 1070-1088. Reconstruction by M.K. Karger.

jeb: St. Michael’s Vydubitsky Cathedral, built 1070-1088, restored in the 17th-18th centuries. The surviving sections of the original construction are exposed to show the Kievan-style architecture. Photo in the public domain.

A six-pillared church served as cathedral for Svyatoslav Yaroslavich’s personal monastery, discovered by excavations in 1947.[52]idem., p. 209.

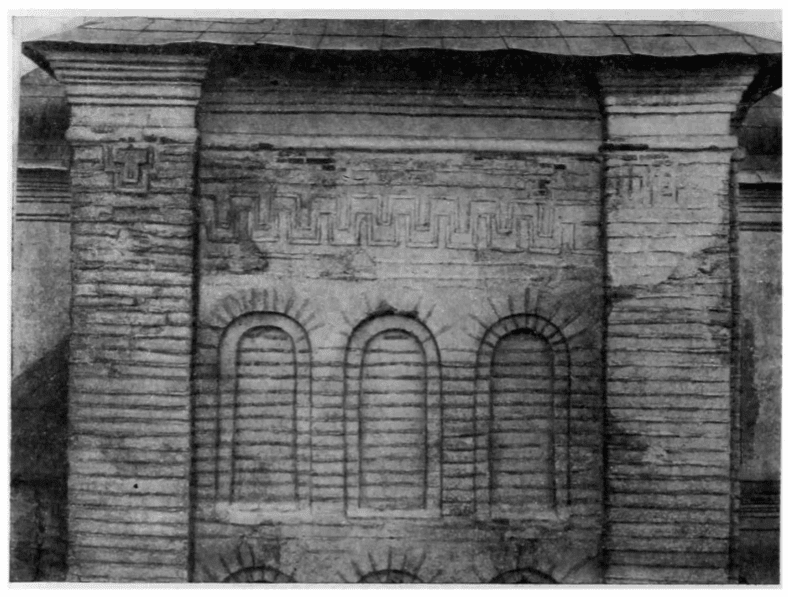

The Church of the Savior at Bérestovo, built in the late 11th-early 12th century by Vladimir Monomakh in his court monastery, is, like the Vydubitsky Cathedral, by the originality and famously-excellent architectural design. The staircase to the choir was added to the narthex, which also has a tomb located in a different corner. As a result, the narthex was wider than the church, with protrusions at its corners. At the same time, a new feature of this building were the three small porches in front of the entrances, giving the church its characteristic cross-shaped plan. These porches were, nevertheless, poorly tied to the composition of the plan, and its walls were thin. The western porch, it seems, had an original three-lesene covering, signs of which are still preserved on the wall of the church.[53]Karger, M. “K istorii kievskogo zodzhestva kontsa XI-nachala XII v. Tserkov’ Spasa na Berestove.” Sovietskaja arkheologija. 1953 (17). In this church, we also encounter the technique of clean brickwork with alternating protruding rows of bricks, with the recessed row covered with a wide strip of lime mortar, giving the façade a two-color striped appearance. An elegant, meandering pattern of bricks ran along the top of the walls (see Illustration).

jeb: Plan for the Church of the Savior at Berestovo, late 11th-early 12th century. Image from Karger, M. “K istorii kievskogo zodzhestva kontsa XI-nachala XII v. Tserkov’ Spasa na Berestove.” Sovietskaja arkheologija. 1953 (17), p. 238, illus. 13.

Detail of the façade of the Church of the Savior at Berestovo, Kiev. Late 11th-early 12th century.

jeb: Detail of the façade from the Church of the Savior at Berestovo, showing the meandering brickwork design. Image from Karger, M. “K istorii kievskogo zodzhestva kontsa XI-nachala XII v. Tserkov’ Spasa na Berestove.” Sovietskaja arkheologija. 1953 (17), p. 246, illus. 19.

A series of 12th-century monastic and urban cathedrals followed the “example” of the Pechersky Cathedral, in which further development of style can be traced. This type evolved in Kievan architecture in the 12th century. The Church of the Dormition in Podol (1131-1132) is one such church, where the staircase to the choir is located not in a tower, but inside the western wall. The Cathedral of Kiev’s Kirillovsky Monastery (1140) is just as similar to Pechersky Cathedral.[54]Aseev, Ju. “Arkhyitektura Kirilyvs’kogo zapovyidnika.” Arkhyitekturnyi pam’jatniki. Kiyiv, 1950, pp. 73-85.

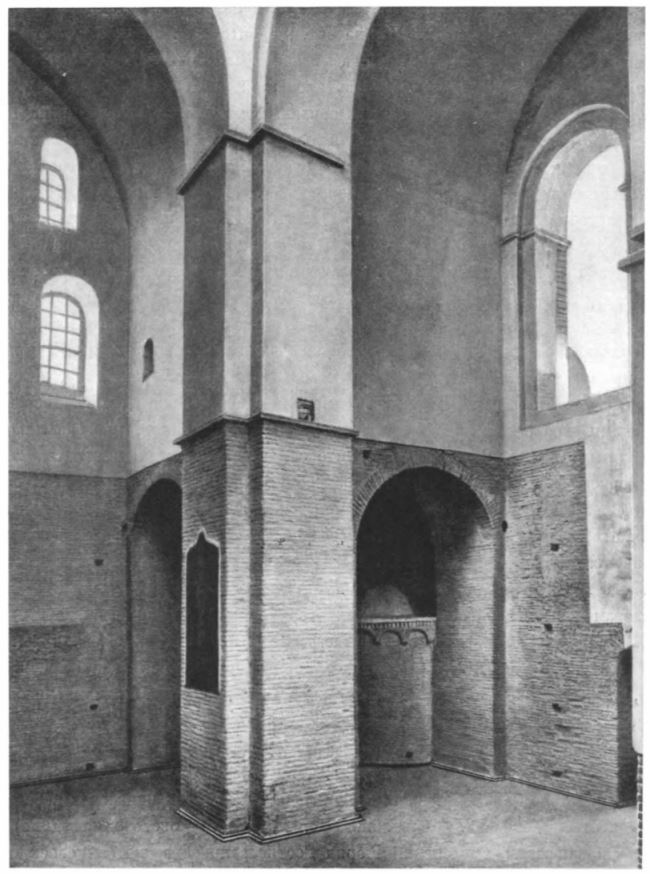

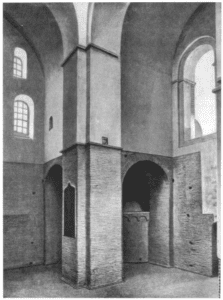

Of particular interest is the cathedral of the Eletsky Dormition Monastery in Chernigov (12th century), in which the baptistery and tombs which formerly violated the seclusion of the square mass of the church, have now been moved to the interior of the building. Just as characteristic is a change in the method of masonry: Eletsky Cathedral was built of one type of brick, and the surface of the walls may have been covered with whitewash or plaster. Along with the former “striped” masonry, the characteristic decoration using a row of niches has also vanished. The walls have attained a severe, dry surface, with only the vertical division of the walls by lesenes surviving, intensified into semi-columns. At the foot of the zakomary, the façade is broken up by a characteristic row of arches. In the Eletsky Monastery’s cathedral, this type of monastic church achieves its fullest embodiment. The severity and simplicity of the bulk, without any extensions, the parsimonious décor of its walls, the simplification of its interior space devoid of any picturesque moments (see Illustration) — these are all traits of the new style which had come together in Kievan royal monasteries by the 11th century to contradict the manifestations of earlier tastes.

Part of the interior of the Eletsky Monastery Cathedral in Chernigov. The original stonework has been exposed. 12th century.

jeb: Eletsky Monastery Cathedral in Chernigov, modern-day.

Maxim Massalitin, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Related to the needs of everyday monastic life, there appeared as part of the monastic ensemble a stone building of a semi-civil nature – the refectory [Rus. трапезница, trapeznitsa]. The refectory in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra was mentioned as early as 1110. But, we are unaware of the exact character of these buildings. It is only possible to assume that they had several overall features in common with barracks [gridnitsy] – a large feasting hall (10th century).

The chronicles have preserved mention of a large building erected by Metropolitan Efrem in Pereyaslavl-Russkiy, the most important political center of the Dnieper region. In the late 1080s, a large, richly decorated cathedral to the Archangel Michael was founded here, and the construction of stone fortress walls around the city with tower gates and gate temples to Sts. Andrew and Theodore [Stratelates] began. All of these buildings have vanished from the face of the earth, and their shape may only be recreated as a result of archaeological study.[55]Excavations of St. Michael’s Cathedral by M.K. Karger have established the presence of a vestibule on the northern wall. cf. Karger, M. “Pamjatniki perejaslavskogo zodchestva XI-XII vv.” Sovetskaja arkheologija, 1951 (15), p. 52.

In the 12th century, in Kiev and particularly in the new feudal cities, there appeared a new type of church, meetings the needs of both the feudal court and the parish. This type of church includes the Three-Saints (Vasiliev) Church in Kiev and a church found during excavations in the Kudryavets track in the Kopyrevo neighborhood of Kiev (both, late 12th century). These buildings were small, 4-column, single-domed charges with three apses and, it seems, with a choir in the western third of the building. It is characteristic that in these late 12th-century buildings, there are signs indicating the non-Kievan origin of their architects. Outer lesenes have been replaced on Three-Saints Church by semi-columns, reminiscent of the church in Smolensk. The church in Kudryavets clearly belongs to a Smolensk artisan. Its corner apses have rectangular outer shapes, and the lesenes have acquired the shape of complex beam pilasters, known from the Cathedral of the Archangel Michael in Smolensk and the Pyatnitsa Church in Chernigov.[56]Karger, M. “K istorii kievskogo zodchestva kontsa XII-nachala XIII v.” Kratkie soobschenija IIMK AN SSSR (KSIIMK). 1949 (27). Architecture at the end of the 12th century lost its local features. It is possible that the strong impact of Smolensk architecture was related to the struggle for the Kievan throne by the princes of the Smolensk and Chernigov dynasties. About the inner decoration of these buildings, we know only that there were relatively simple majolica floors and frescoes.

jeb: Church of the Three Saints in Kiev, built 1183. The church was destroyed by the Soviets in 1935 as part of an anti-religion campaign. Photo in the public domain.

jeb: The Chernigov Pyatnitsa Church, built late 12th century. The church was destroyed in WWII, but was restored to its medieval plan in the 1950s.

Serguei Trouchelle, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

In Kievan-Chernigov architecture of the 11th-12th centuries, we encounter the first examples of small, cupolaed churches, completely devoid of pillars and which were either based on individual designs, such as an unnamed single-apse chapel uncovered by excavations in Pereyaslavl-Yuzhny, or monastic churches for a particular purpose, such as the Church of St. Elijah above the caves of Eletsky Monastery in Chernigov. This group also includes a small church to the Archangel Michael, built by Vladimir Monomakh in his village in Ostyor, known as the “Yuriev Goddess” [Jur’eva bozhnitsa]. Its western section appears to have had a small porch, and the ceiling of the main, relatively small in size central nave was “deaf” (that is, the drum of the tower had no windows for light). Over the vaults, there towered a likewise windowless wooden pitched roof; according to the Hypatian Chronicle, the roof of the church was “hewn from wood.”[57]Hypatian Chronicle, under year 6660 (1152).

In the late 12th century, Svyatoslav Vsevolodovich, having seized the Kievan throne, built the Cathedral of the Annunciation in his city of Chernigov. This church, uncovered by excavations on the bank of the Strizhen River, was a monument of its time when, under the impression of Igor’s defeat to the Polovtsians, the alarming words of the folk poet’s ingenious call in the Lay of Igor’s Campaign for the princes to reunite resounded over Rus’, and when the fact of the former Russian unity under “the old Vladimir” and Yaroslav the Wise once again attracted the thoughts of political figures. The most powerful of Rus’ princes, Vsevolod of Vladimir, Syatoslav of Kiev, Ryurik Rostislavich of Smolensk, all turned in their buildings to examples of majestic structures from the 10th-11th centuries.

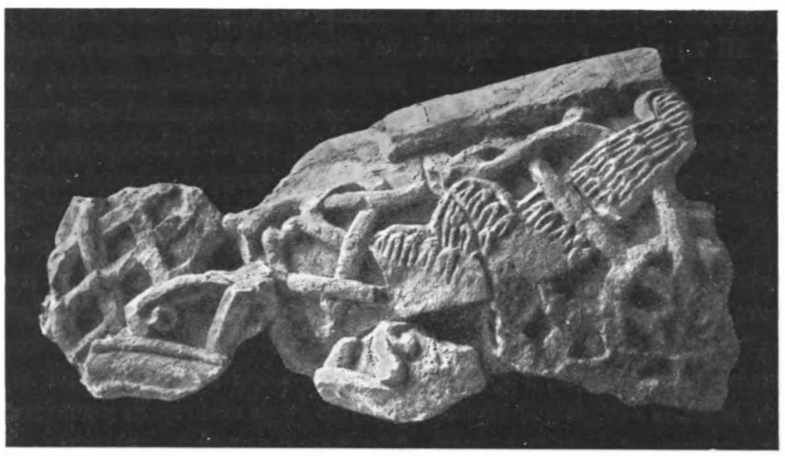

The Cathedral of the Annunciation[58]jeb: The cathedral was built in 1186, and was heavily damaged during the Mongol invasion in 1240. The church was demolished shortly thereafter. was a large six-columned cathedral, with galleries on three sides. It appears that these galleries were reduced in size, strengthening the “stepped” appearance of the church’s bulk, as if echoing the staggered composition of the Church of the Tithes and St. Sophia’s Cathedral. Astonishingly, the lush technique of mosaic floors was reborn, of which only a stunning figure of a peacock inside a circle has survived. The altar space had a white stone ciborium, decorated with complex carving, of which one fragment has survived – a bird inside a band of knotwork (see Illustration). It appears that this carved white stone was also included in the decor of the church walls, which also featured the arched band known from the Eletsky Cathedral.[59]Rybakov, B. “Drevnosti Chernigova.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR. 1949 (11).

Fragment of stone carving from Cathedral of the Annunciation in Chernigov, 1186. Chernigov Museum.

jeb: Floor mosaic design including a peacock from Cathedral of the Annunciation in Chernigov, 1186. Dunadan Ranger, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Chernigov’s Boris and Gleb cathedral, built 1120.

Star61, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Vasil’evsky Church, Ovruch, built 1190, destroyed 1321, reconstructed 1907-1909.

Валерій Ящишин, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As shown by the most recent studies in Chernigov, love for luxurious church décor and its wide, spacious composition was particular to Chernigov princely building. Thus, Boris and Gleb Cathedral (12th century) had tomb-galleries and richly decorated floors, and carved stone was used in its decoration.[60]“Doslizhenya Borysoglibs’kogo soboru v Chernigovi.” Arkhitekturni pam’jatnyky. Kyiv, 1950, pp. 64-72.

Ryurik Rostislavich’s name is tied to the building of the Vasil’evsky Church (late 12th century) in his city of Ovruch, to the northwest of the Kievan principality. The ruins of the church were masterfully excavated by P.P. Pokryshkin, allowing us to determine with great precision even details of the exterior wall decoration; the church was just as expertly restored by A.V. Schusev. This monument is not surprising in its dimensions. It was a relatively small four-column church with a single dome, with faceted stair towers in the corners, giving the building an extremely ceremonial, monumental character and majesty. These towers were clearly inspired by the example of Kiev’s St. Sophia, but here they are almost symmetrical. The brickwork was enlivened by frequent insertions of flat smooth boulders, reminiscent of the alternating stone and brick in St. Sophia’s facade, and methods of Grodno architects whose monuments we will review below. This church in Ovruch also shows signs of non-Kievan architects. As with the Kievan church in Kudryavets, we see beam pilasters, the lesenes on the towers and apses are semi-columns, the arches cut off the zakomary, and the large openings for the entryways are designed like portals.

But, these buildings, in which we see echoes of Yaroslav’s Kievan architecture, brought to life by the political aspirations of their princely-builders, do not change the overall course of the development of Dnieper-region architecture, as we have characterized above.

Reviewing the architecture of Kiev and Chernigov together, we assumed a certain convention: the 12th century was not known, strictly speaking, for its “architecture of Kievan Rus’.”

As can be seen from our review of monuments, the architecture of Chernigov acquired its own specific features, allowing us to speak of a general Chernigov architectural school, or Chernigov architecture. One of these characteristic traits was the combination of brickwork with white carved stone details, a love for majestic proportions, and rich decoration.

We spoke above about the use of carved stone in the decor of the Cathedrals of the Assumption and of Boris and Gleb in Chernigov. In the latter case, of particular interest are the carved white stone capitals depicting animals, winged dragons and birds in bands of knotwork.

During this time, Kiev and the Kievan principality, which had become the arena of fierce feudal warfare, were influenced by regional architectural schools. Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky of Vladimir sent his Vladimiran architects to Kiev to build an exquisite church in the great Yaroslav’s court; Smolensk architects built the church in Kudryavets; it is possible that either they or architects from Volynsk built the church in Ovruch. Peter Miloneg, a friend of Prince Ryurik Rostislavich and famous in the architectural history of Kiev, the one who built in 1199 the stone river-shore church for Vydubitsky Monastery, was most likely a Smolensk architect. Regional architectural schools, having been raised on the heritage of Kievan art, paid their debt to the impoverished “mother of all Russian cities.”

Given the qualifications made about the originality of architectural development in the Kievan province and in Chernigov, we can nevertheless give a general appraisal of the architecture of the Dnieper region and of what brought about this new stage in the history of Rus’ – the period of feudal fragmentation. By summing up the characteristic traits of the architecture of Kiev and Chernigov in the 12th century, we thereby define the main features of the architectural style of that historical period.