I was recently doing some research into medieval archery, and came upon a book by A.F. Medvedev that was completely devoted to archery in Rus’ in the 13th-14th centuries. One of the chapters, which I’ve translated below, was devoted to crossbows, which were introduced to Rus’ around the 12th century. I just ordered my first crossbow, so it was fun to learn more about how these weapons were used in my persona’s lands.

Crossbows

A translation of Медведев, А.Ф. «Самострел.» Ручное метательное оружие (лук и стрелы, самострел): VIII-XIV вв. Москва, 1966, с. 90-96. / Medvedev, A.F. “Samostrel.” Ruchnoe metatel’noe oruzhie (luk i strely, samostrel): VIII-XIV vv. Moscow, 1966, pp. 90-96.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The book in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.academia.edu/30139333.]

[Note that the Illustrations are intentionally out of order. Only Illustration 5 actually appears in this chapter of the book. Illustration 1 was present in an earlier chapter, but is referenced here. I have included it at the first mention in this chapter.]

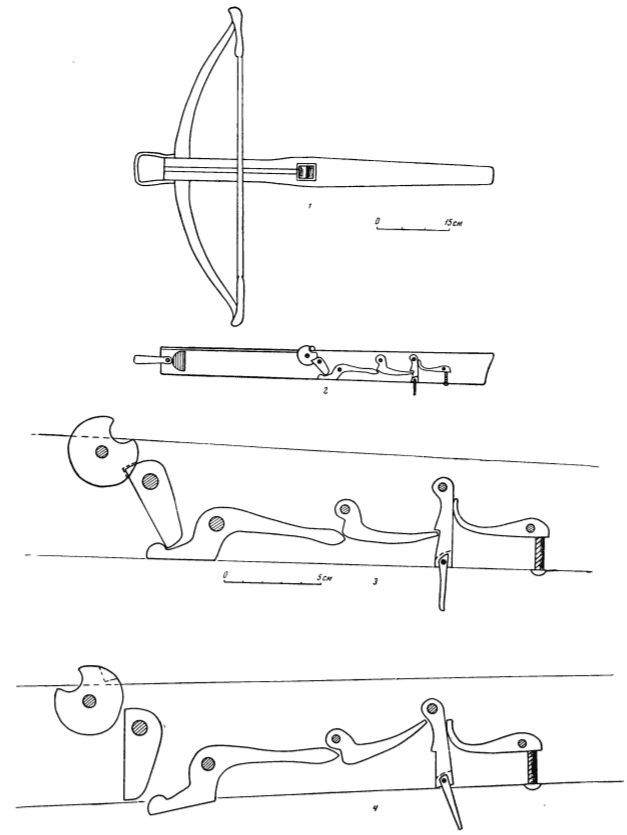

The crossbow [jeb: Rus. самострел, samostrel, literally “self-shooter”] is a mechanized bow, one type of long-range warfare. It owes its origin, certainly, to the bow. It consists of a very resilient prod [jeb: Rus. дуга, duga, literally “arc”] (itself a bow), embedded into a wooden stock [jeb: Rus. ложе, lozhe] with a butt. The stock has on top one or several shallow grooves, which may be compared in role to the barrel of a gun. Arrows or crossbow bolts would be placed into these grooves.

At first, crossbows were made from the materials as sophisticated bows, that is, from various species of wood, horn, and sinew. Later crossbow bows, or prods, would be made from steel bars. Naturally, the string of such crossbows could not be drawn by hand. Therefore, to facilitate drawing and firing the crossbow, a special trigger mechanism and a windlass or “crossbow winch” [jeb: Rus. коловорот самострельный, kolovorot samostrel’nyj] were mounted within the stock. The bow was cocked with both hands, while the crossbow was held with the aid of a special stirrup that was attached to the front end of the stock. The stock had a special dog-leg ledge to hold the string at the nut [Rus. собачка, sobachka]. The bowstring was released using a special mechanism (Illustration 5).

1 – top view; 2 – side cross-section; 3 – cocked; 4 – after firing

The bowstring of a crossbow was made of a thick durable cord, twisted from rawhide straps or ox veins.

Moscow’s Armory Palace stores several medieval Russian crossbows, made in Moscow and Pskov in the 16th century. Their prods are made of steel. Based on this, P.I. Savvitov and D.N. Anuchin asserted that Rus’ crossbows only had steel prods.[1]Savvitov, P.I. “Opisanie starinnykh tsarskikh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, izvlechennykh iz rukopisej arkhiva Moskovskoj Oruzhejnoj Palaty.” Zapiski Arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XLI, 1865, pp. 302, 528; Anuchin, D.N. “O drevnem luke i strelakh.” Trudy V arkheologicheskogo s’ezda v Tiflise. Moscow, 1887, p. 356. One is unable to agree with this conclusion. In the lands of the Near East, as well as Rus’, most likely, up until the 15th century crossbows commonly used prods made of wood, tendons, and horn. Moreover, in Rus’, as early as the 10th century and possibly even earlier, a kind of hunting crossbow was used; this was a large simple bow (“watchful bow”)[2]jeb: With a tripwire? which was set up on animal trails. These kinds of bows were also used by the tribes of Siberia.

Crossbows were widely used in the middle ages in Persia, Turkey, and Spain, where they were carried by Moors.

According to a 15th century Arab archery manual, Turkish and Persian crossbows were created according to the same principle as a composite bow [Rus. сложная лука, slozhnaja luka], but were significantly more powerful. They were built using a grooved deck which was fitted with a lock and a trigger. At the end of the stock was a stirrup. These “foot bows”, or crossbows, in the Arabian East existed during the Middle Ages in many variations, but they were “cursed by the Prophet,” and therefore were not appreciated by Arabs themselves.[3]Arab Archery: An Arabic Manuscript of About AD 1500. A Book on the Excellence of the Bow and Arrow and the Description Thereof. Trans. NA Faris and RP Elmer. Princeton, 1945, p. 12.

The Russian chronicles confirm that during the siege of Constantinople in 1453, the Turks used many of these “foot bows.”[4]Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej (PSRL). Vol. VIII (Letopis’ po Voskresenskomu spisky) St. Petersburg, 1856, p. 124; Vol. XII (Letopisnyj sbornik imenuemyj Patriarsheju ili Nikonovskoju letopis’ju) St. Petersburg, 1901, p. 842. This term was used in order to distinguish an everyday composite bow from crossbows, as the Turks used both at this time.

In Western Europe, crossbows (arbalests) were widely used in the 12th-15th centuries, after the Crusades. In 15th century France, arbalests were made, like simple bows, from yew wood, for which purpose the Decree of Karl VII (1422-1463) ordered yew trees be planted on graves in Normandy. But, as A. Demmin noted, arbalests were ineffective, and a nimble archer was able to release 3-4 times as many arrows than a crossbowman in the same amount of time.[5]Demmin, Auguste. Guide des amateurs d’arms et armures. Paris, 1869, p. 490. In addition, the bowstring of an arbalest spoiled more quickly from rain (stretched out and weakened), as it could not be taken off [when the arbalest was not in use].

The crossbow arrow (bolt) exceeded an ordinary arrow in the force of its blow, but was significantly inferior in distance of flight.

Marco Polo noted that crossbows existed amongst the Mongols in the 13th century, who most likely adopted from from the Chinese. However, they had no military significance there, or the Russian chronicles would certainly have mentioned their use.[6]Polo, Marco, Puteshestvie. Leningrad, 1940, pp. 78, 153. In all of the cities destroyed by the Tatar-Mongols, normal Mongol arrowheads found have been from normal arrows; no crossbow bolt heads have been found in neither Staraja Rjazan’, or in the cities of North-Eastern Rus’.

In Rus’ of this period, crossbows were in relatively limited use, primarily along the borders with their western neighbors. In the 14th-15th centuries, foot soldiers used them primarily during sieges and defense of cities. For both Russian and Tatar cavalry, crossbows were difficult and inconvenient, and were significantly less effective than regular bows.

The first crossbows are mentioned in Russian chronicles in 1184, in connection to a raid on Rus’ by the Polovtsy. The Polovtsy had some kind of an incendiary weapon (“spewing out live fire”) and “a crossbow that could barely be cocked by even 50 men.” This story, no doubt, is not about a handheld crossbow, but rather some kind of ballista, given the enormous force needed to cock the string.

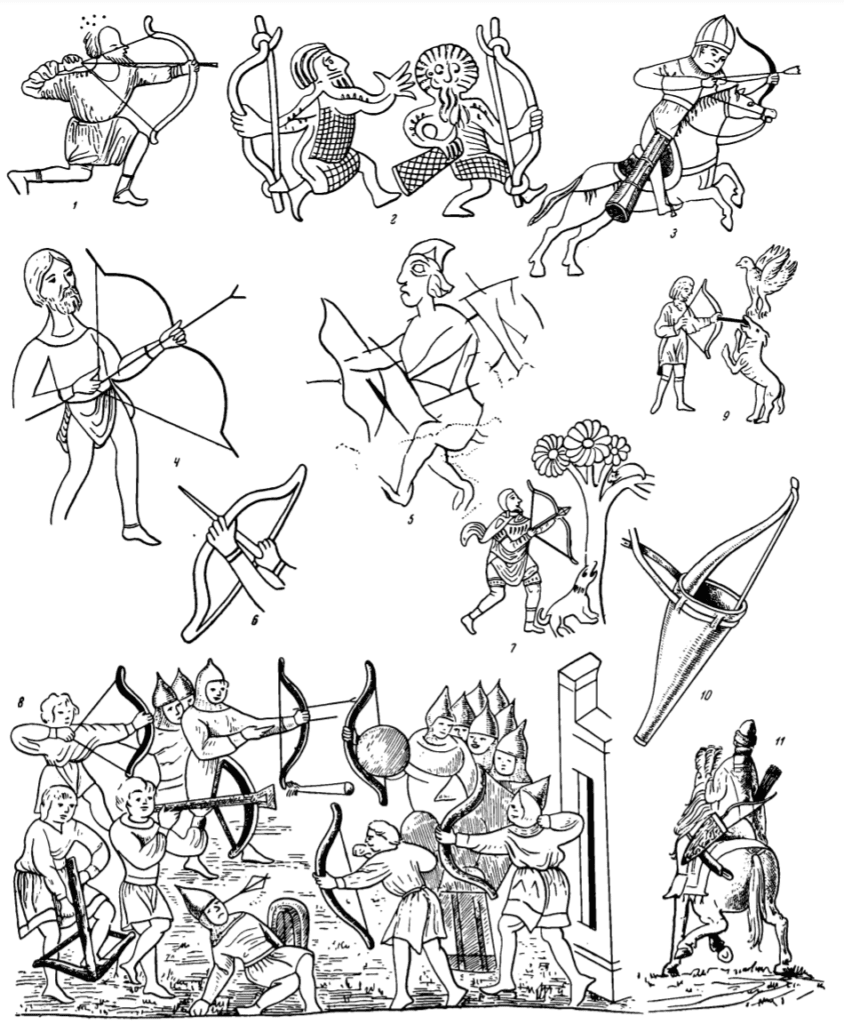

Crossbows are also depicted in miniatures from the Königsberg Chronicle[7]jeb: aka Radziwiłł Chronicle, a manuscript which is believed to be a 15th century copy of a 13th century original., illustrating events from 1151 and 1184. Judging by these depictions, these crossbows were of the same construction as those which have survived from the 16th and 17th centuries. There we can see how they were aimed (at eye-level), how they were aimed using two crank handles near the trigger, the stirrup for bracing the crossbow with the foot, and crossbow bolts with blunt points and fletching. They are used only by foot soldiers.

The arrival and spread of the crossbow in Rus’ can also be clearly traced by archeological finds of crossbow bolt heads in many medieval Russian towns, including Novgorod. In the precisely dated layers of the Nerevskij dig in Novgorod, crossbow bolt heads are first found in the 17-m building tier, which according to all data (including dendrochronological) corresponds to the last quarter of the 12th century (1177-1197), closely aligning with and confirming the Chronicles’ timing.

In Western Europe, according to Demmin, the arbalest became popular around the 12th century.[8]Demmin, op. cit., pp. 495-498. But, it first arrived there in the first half of the 12th century, a bit earlier than in Rus’. Bolt heads similar to and dating to the same time period as those from Novgorod have been found in the Baltic region, Poland,[9]Nadolski, Andrzej. Studia nad uzbrojeniem polskim w X, XI i XII wieku. Lodz, 1954, pp. 65, 194-197, plate XXXII, items 1-4., and in all of Western Europe, including England.[10]Noel-Hume, J. Archaeology in Britain. London, 1953, p. 96, plate XIX, item 8.

As was noted by D.N. Anuchin, the crossbow was introduced by the Arabs to Western Europe. It was also introduced into Rus’ directly from the Arab East. But, we are unable to agree with Anuchin’s belief that the crossbow appeared in Persia and amongst the tribes of Northern Russia via Western Europe.[11]Anuchin, op. cit., p. 356. This route (Mediterranean – Western Europe – Persia and Northern Russia) seems very strange and unrealistic. In addition, the crossbows of the Northern Russia peoples are principally different from handheld crossbows of medieval Europe. They did not have the same complex mechanism with metallic parts as Russian, Eastern, and Western European crossbows (arbalests), and were used in the North exclusively for hunting. This use of crossbows by the Laplander and Siberian tribes for hunting was also reported by Jacob Reitenfels in the 17th century; a “watchful bow” (or crossbow) used by the Siberian tribes is also described in detail in an article by Gr. Dmitriev-Sadovnikov.[12]Rejtenfel’s, Jakov. Skazanie o Moskovii. Moscow, 1905, p. 213; Dmitriev-Sadovnikov, Gr. “Luk vakhovskikh ostjakov i okhota s nim.” Ezhegodnik Tobol’skogo gubernskogo muzeja. Iss. XXIV. 1915, pp. 14-22.

Some advantages of the composite bow over the crossbow may be judged not only by the Western European accounts mentioned above, but also by Russian chronicles from the 13th century. There, in a 1252 skirmish against the warriors of Mindaugas of Lithuania which included detachments of German mercenaries with crossbows, Daniil of Halych’s cavalry routed the German crossbowmen and chased them across the field “like game.” But even Daniil had crossbowmen at this time. In 1261, the citizens of Kholm with catapults and crossbows, and did not surrender.[13]Letopis’ po Ipat’evskomu (Ipatskomu) spisku. St. Petersburg, 1871, pp. 543, 563.

Later mentions of crossbows amongst the Russians or Volga Bulgars are continually associated with the defense or siege of cities. It seems that they were more frequently used by the townsfolk than by professional soldiers.[14]PSRL, vol. VIII, p. 24; vol. X (Letopisnyj sbornik imenuemyj Patriarsheju ili Nikonovskoju letopis’ju) St. Petersburg, 1885, p. 25.

The citizens of Moscow defended their city from Tokhtamysh’s soldiers in 1382 using crossbows and firearms. At the time, there were almost no soldiers in the city, and the defense was held in large part by artisans and merchants. The Chronicle states that the Muscovites “shot arrows from the city walls, or struck [the Tatars] with stones, while others shot at them with harquebuses, and others shot them with crossbows or catapults, and others fired large canons.”[15]PSRL, vol. XXIV (Tipografskaja letopis’) Petrograd, 1921, pp. 151-152. Indeed, when one citizen, a felt-maker named Adam, “took up a crossbow and released an arrow,” he managed to kill one of the Khan’s associates.[16]PSRL, vol. XI (Letopisnyj sbornik imenuemyj Patriarsheju ili Nikonovskoju letopis’ju) St. Petersburg, 1897, p. 75.

Throughout the 15th century, crossbows were used in Rus’ exclusively for the defense and siege of cities. In 1408, they were used in Tver’. The prince of Tver’, Ivan Mikhajlovich, as an ally of the Tatar Khan Edigei, brought along crossbowmen on campaign against Moscow.[17]PSRL, vol. VIII, p. 83. Crossbows were also used in smaller cities in the 15 century, such as Galich on the Volga.[18]idem., p. 122. By this time, a certain formula had developed for describing the list of weapons used whenever there was a siege: “cannons and pischali,[19]jeb: A pischal’ was a medieval Russian firearm, between a cannon and an arquebus. Literally, the word means “squeaker”. crossbows and weapons, and shields, bows and arrows, as befits battle against an enemy,” as was said in one Chronicle in relation to a Tatar raid in 1451.[20]PSRL, vol. XVIII (Simeonovskaja letopis’) St. Petersburg, 1910, p. 207. While discussing a raid by Akhmat in 1472, the Chronicle bitterly notes that at that time in Aleksin they did not even have crossbows.[21]PSRL, vol. XII, p. 149. In 1478, Ivan III ordered the governor of Pskov, Shujskij, to go to rebellious Novgorod “with cannons, and pischali, and crossbows, and with all one needs to capture a city.”[22]PSRL, vol. VIII, p. 187.

An inventory of the Moscow Armory from 1687 (folio 459) lists the crossbows stored there and their characteristics. The inventory mentions several details of the construction of each crossbow, the material from which each was made, and their finishing and decorations. “A large crossbow, made in Moscow, with a butt at each end, made of apple wood, embedded with mother of pearl surrounded by brass settings and copper wire, with a pischal’-style trigger.” “A crossbow, of Moscow make, of maple, decorated with carved moose bone,” and so forth. “A crossbow of Pskov make, with a maple stock, decorated with bison bone, with a deck of moose bone in four columns, separated by black bone.” It also mentions “a winch”, “winch-like casing,” and crossbow bolts which apparently had bone points and fletching. Crossbow bolts had various kinds of heads: four-sided, three-sided, and two-sided or flat.[23]PSRL, vol. XII, p. 149The crossbows themselves were painted and richly decorated.

The construction of medieval crossbows can be judged based on examples preserved in our museums, as well as individual finds from archaeological digs in Novgorod, Grodno, and Izjazlavl, as well as from depictions in the Radziwiłł Chronicle (see Illustration 1, item 8).

1 – footsoldier from a miniature in the Khlodovskij Psalter; 2 – archers on the silver covering of an aurochs horn from Chernaja Mogila; 3 – a Russian archer on horseback, 10th century, from a miniature in the Manasene Chronicle; 4 – archer from the Svjatoslav Izbornik of 1073; 5 – depiction of an archer on a late 11th-early 12th century stone sinker from Novgorod; 6 – image of a bow from a stone carving in 12th century St. Dmitrij Cathedral in Vladimir; 7 – hunting with a bow, from the frescos in St. Sophia’s Cathedral in Kiev; 8 – archers and crossbowmen in a miniature from the Radziwiłł Chronicle; 9 – a hunter with a bow, carved on the shaft of a spear belonging to Tver’ prince Boris Aleksandrovich; 10 – a bow and bow cover, from a drawing in Gerberstein’s 1556 book; 11 – a 17th century archer on horseback, from Meierberg’s album.

In Novgorod, in a layer from the 13th century, a steel part from the firing mechanism of a crossbow was found. In Grodno, a layer from the 13th-14th centuries contained a bone part from a firing mechanism: a round nut with a semicircular notch to hold the string acocked, and with a hole in the center for an iron or steel spindle. When fired, this nut would spin forward from the power of the drawn bowstring, and the string would slip out [of the notch], propelling the arrow or “crossbow bolt”.[24]Voronin, N.N. “Drevnee Grodno.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR. 1954 (41). p. 167, illus. 88-18. In Izjaslavl, which was founded in the mid 12th century and destroyed during the Tatar invasion in 1240, they discovered an iron belt hook used for drawing the string of a crossbow. The hook originally had one or two belt-loops, attached to it by four rivets, but these belt-loops have not survived.

The firing mechanism for a 16th century crossbow is shown in Illustration 5. Crossbows from earlier periods (13th and 14th centuries) appear to have been similar, based on parts found in Novgorod and Grodno.

Together with crossbows and pischali, the compound bow had also long been used in Rus’, especially by mounted border troops. In 1659, the Russians, having smashed the Crimean Tatars at the Samara River, seized great spoils of war, including 200 horses, bows, and sabers. There were so many bows, that the Cossacks took only the best ones, and threw the rest into the river.[25]Akty Moskovskogo gosudarstva (AMG), vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1894, p. 554. It would seem that compound bows were still built well, or it would hardly have been necessary to throw them in the river. Another document from 1661 attests that bows, pischali, spears and poleaxes were still owned by peasants, it is true, in the border regions, where weapons were quite necessary for fight off Tatar raids.[26]AMG, vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1901, p. 371.

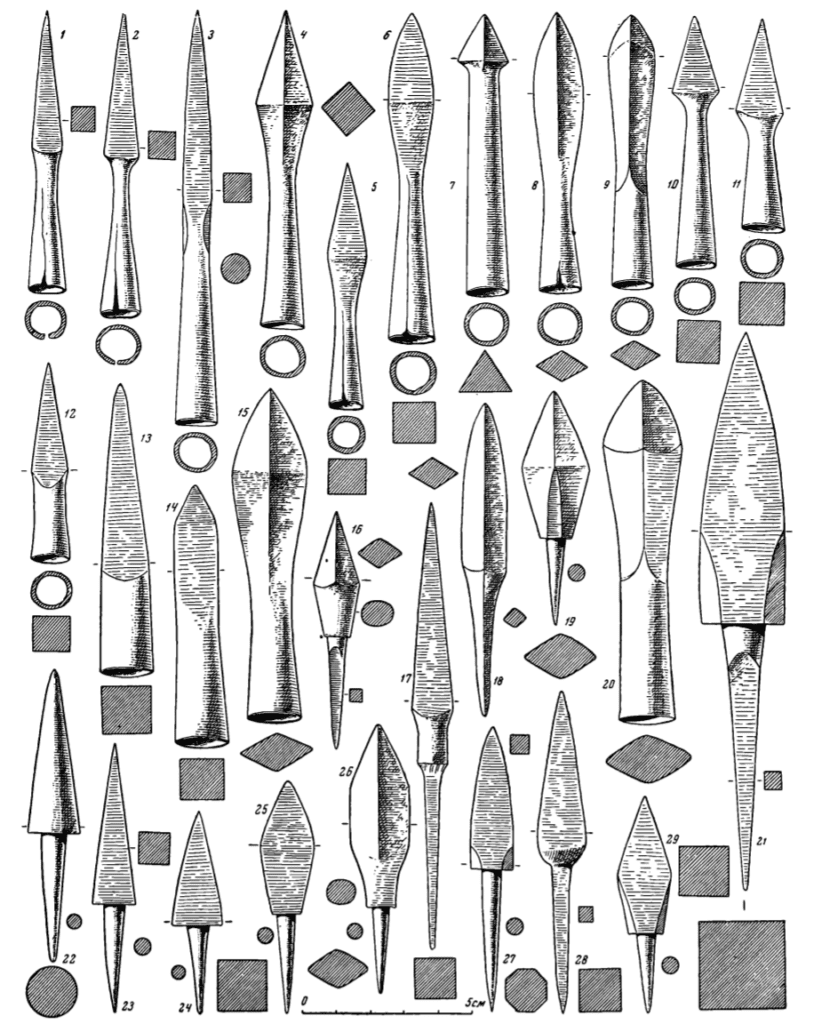

Crossbow Bolts and their Points

In Rus’, they used [wooden shaft] bolts and completely-iron crossbow bolts, which had an iron rod that was round in cross-section, about 1 cm in diameter, instead of a wooden shaft. One such bolt with a pyramidal head (same type as Plate 31, item 28) was found in Staraja Ladoga in a layer from the 13th-15th centuries.[27]The Hermitage, 13/2713. This bolt was 27 cm in length, with an end that was a bit thinner and, it appears, broken off. The normal length of preserved crossbow bolts from the 16th-17th centuries is 30-40 cm. Bolts had 2-3 fletches, but as a rule did not have nocks [Rus. ушка для тетивы, ushka dlja tetivy].

All crossbow bolt heads are divided into two groups, depending on the manner of how they attach to the shaft: socketed [Rus. втульчатые, vtul’chatye] and tanged [Rus. черешковые, chereshkovye, lit. “petiolar”]. A characteristic feature of crossbow bolt heads is their massiveness, regardless of shape. They were all able to pierce armor, regardless of whether they were square, diamond, or (more rarely) triangular or round in cross section. They were all significantly larger than the typical arrow head. While the latter averaged around 9 g, judging by 130 examples found in Novgorod, crossbow bolt heads ran from 18 g to 30 g, while many weighed 30-50 g or even as large as 200 g (Plate 31, item 21).

Socketed bolt heads are distinguished from socketed arrow heads by the size of the socket diameter. Arrow heads typically have sockets that are 7-9 mm in diameter, while crossbow bolt heads are typically 10-15 mm in diameter. Tangs on bolt heads are, as a rule, significantly more massive than those of arrow heads, and are almost always either round or square in diameter.

Bolt heads from the late 12th-14th centuries were 6-12 cm in length, and only in rare cases reached 16 cm. These heads were typically 8-15 mm in width, rarely reaching 25 mm. Generally speaking, earlier bolt heads (12th-13th century) were less massive than later ones (14th-15th century).

Based on shape and cross-section, socketed bolt heads can be divided into 8 different groups. Heads which are square in cross-section are grouped by the shape of their faces and the character of their sockets; heads which are diamond in cross-section are grouped by the shape of their widest face.

Type 1: Pyramidal, square in cross section, with a neck (Plate 31, items 1-2, 10-11). The earliest (12th-13th centuries) have faces in the shape of an elongated isosceles triangle in 1:4 proportions. Later, the heads were shorter and more massive, with sides in proportions of 1:3 or less (Plate 31, 10, 11). Theses were 6-10 cm in length, with heads 2.5-4.5 cm, at greatest width 8-14 mm, and weighed 12-30 g (averaging 20 g).

Bolt heads of this type were prevalent in medieval Novgorod (more than 30 examples found), where they appeared in the last quarter of the 12th century, and were in use until the last quarter of the 15th century. Heads of this type were also used in Latvia, where they have been discovered in the settlements of Mezotne (7 examples) and Martinsala.[28]Museum of the Latvian SSR. In Mezotne, bolt heads of this type have not been found earlier than the second half of the 12th century. Hence, the period of their use was the second half of the 12th century through the 15th century.

Bolt heads with more elongated proportions of 1:7 can be considered a variation of this type (Plate 31, item 3). These were up to 13 cm in length. These have been found in Mezotne and in Izjaslavl.[29]Digs by M.K. Karger, 1957-1961, Leningrad department of the Institute of Archeology of the USSR Academy of Sciences (LOIA).

Type 2: Pyramidal, square in cross section, without a neck (Plate 31, items 12-13). These are 6-8 cm in length, with faces 1-1.4 cm in width, and with proportions of 1:3 to 1:4. These have been found in Smolensk (in layers from the 13th-14th centuries),[30]Dig by D.A. Avdusin, 1957, Smolensk Museum. in the Dnieper region,[31]Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. and in Izjaslavl.[32]Dig by M.K. Karger, 1958, LOIA.

Type 3: Square in cross section, with short pyramidal points (Plate 31, item 14). Three bolt heads of this type have been found in the Kiev region,[33]Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. dated to the 13th-15th centuries.

Type 4: Pyramidal with a diamond-shaped head, square in cross section (Plate 31, item 4). 6-9.5 cm in length, with the head 4-5 cm long, and the face up to 1cm wide. These were in use in the 13th-14th centuries. They have been found in Novgorod, Grodno,[34]Voronin, op. cit., Illustration 88, item 8. the Dnieper region,[35]Temitskij collection, Kiev Historical Museum, No. 21867. and Latvia.[36]Shnore, E.D. Asotskoe gorodische. Riga, 1961, plate X, items 1-2.

Type 5: Pyramidal, square in cross section, with facets shaped like a pointed leaf (Plate 31, item 5). These bolts have so far only been found in Novgorod, and date to the 13th century. This type is in all ways similar to type 1, with the exception of the shape of the facets.

Type 6: Pyramidal, square in cross section, with facets shaped like laurel leaves (Plate 31, item 6). These were used quite widely in Latvia, are found in 14th century layers in Novgorod, and have also been foudn in Izborsk, where G.P. Grozdilov found them in the limestone mortar in the masonry of a fortress wall, erected around 1330. They undoubtedly hit the just-built wall during a raid by one of the Baltic tribes. In Latvia, they were found in the forts of Tervet[37]Digs by Brivkalne, 1954-1958. and Mezotne, where they fell out of use in the 13th century. They were also found in great numbers in Riga and the hillfort of Velidona, where they were possibly used as late as the 15th century.[38]Stored in the collections of the Riga and Latvia SSR Museums. As a result, these are dated to the 13th-15th centuries.

Type 7: Pyramidal, triangular in cross-section (Plate 31, item 7). A lone example of this type has been found, in the grave of a nomad in the Kamenskij burial ground (#82).[39]Dig by E.A. Symonovich, 1953. The entire head weighs 19 g. Judging by the decorated bone plates on the quiver, this burial dates to the 14th century.[40]Symonovich, E.A. “Kamenskij mogil’nik.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury Akademii nauk SSSR. 1956 (65), illus. 36 (the author’s dating is incorrect.).

Type 8: Laurel-leaf shaped heads, diamond in cross-section (Plate 31, items 8-9, 15, 20). Widely used in Latvia and in Rus’ to the west of the Novgorod-Smolensk-Kiev line. They are divided by shape into 2 kinds, each of which has 2 variants (compare Plate 31, 8 & 15 vs. 9 & 20).

Bolt heads of the first type (Plate 31, item 8) have been found in the hill fort of Khutor Polovetskij,[41]Dig by V.I. Dovzhenok, 1956, Museum of the Institute of Archeology of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. which ceased to exist during the Mongol Invasion of 1240, in 13th-14th century layers in Smolensk,[42]Digs by D.A. Avdusin, 1951-1955. Smolensk museum. in Pskov (in Domontovoe town, 14th century layer),[43]Dig by G.P. Grosdilov, 1960. Stored in the Hermitage. in Drutsk (13th-14th century layer),[44]Dig by L.V. Alekseev., in Grodno (13t-14th century layer),[45]Voronin, op. cit., 1954, Illustration 88, item 7. in Riga,[46]Riga Museum, No. 41998/190., and in the hillfort of Velidona, where they were used from the 12th-15th centuries.[47]Museum of the Latvian SSR. Bolts of the same shape, but larger and heavier (Plate 31, item 15) have been found in the Pskov kremlin (13th-15th century layer),[48]Dig by S.A. Tarakanova, 1948. Pskov Museum., in Izjaslavl, and in Riga.

Bolt heads of the second type differ in that the widest area of the head falls not in the center, but rather closer to the point (Plate 31, items 9 and 20). These have been found in a 14th century layer in Novgorod, in the Kiev region,[49]Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. and in the hillfort of Velidona.[50]Museum of the Latvian SSR. In those last two locations, only the larger examples have been found (second variant).

It is possible that bolt heads of the second variation were characteristic in the 14th and 15th centuries, while those of the first variation appeared in the last 12th or early 13th century.

Among the tanged bolt heads, we find another 11 types.

Type 9: Conical, round cross section (Plate 31, item 22). One example like this has been found in grave #82 in the Kamenskij burial mound (see Type 7).[51]Symonovich, op. cit.

Type 10: Pyramidal, square in cross section, with triangular facets (Plate 31, items 23, 24). 6-14 cm in length, with the head 3.2-8 cm long, and the widest part of the face 1-1.5 cm. Found on Knjazha Gora,[52]Dig by N.F. Beljashevskij. Kiev Historical Museum. where they may date to the late 12th or first half of the 13th century (before 1240); at the Semigallian settlement of Mezotne (4 examples),[53]Museum of the Latvian SSR. where they ceased being used by the 13th century; and in Riga, where they may have been used from the 12th-15th centuries. Early heads of this type have more elongated proportions (1:6 – 1:8),[54]Kiev Historical Museum. while later examples are less elongated (1:2 – 1:5).

Type 11: Pyramidal, square in cross section, with triangular convex facets and cut off corners at the base (Plate 31, items 21 and 27). 8-16 cm in length, with the heads 4-8.5 cm long, facets 1.2-2.5 cm wide, weight from 30-200 g. The most massive examples belong to the later period of their use (14th-15th century). They were found on Knjazha Gora[55]Dig by N.F. Beljashevskij. Kiev Historical Museum. and in Izjaslavl,[56]Digs by M.K. Karger, 1959-1960, LOIA. which was destroyed in 1240. There they probably were used in the late 12th or first half of the 13th century. Aside from the locations mentioned above, these were also found in Suvar (Volga Bulgaria) and in the hillfort of Martinsala near Riga, where a German castle was located from the late 12th-15th centuries, and where the most massive examples have been found, weighing as much as 200 g (Plate 31, item 21).

Type 12: Pyramidal, square in cross section, with sides shaped like pointed leaves (Plate 31, item 28). As opposed to bolt heads of type 10, these do not have an abrupt, stepped transition from the head to the tang. These have been found only on the lands of medieval Rus’: in the Dnieper Region,[57]Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. in Smolensk (a layer from the 13th-14th centuries),[58]A dig by D.A. Avdusin, 1951. Smolensk museum. in the Pskov kremlin (layer from the 13th-15th centuries),[59]Dig by S.A. Tarakanova, 1948, Pskov Museum. and in Staraja Ladoga,[60] Dig by Leningrad State University, 1938. Hermitage, 13/2713. where an iron bolt was found with this type of head. It follows that these were in use from the 13th-15th centuries.

Type 13: Elongated pyramidal, square cross section, with a round neck (Plate 31, item 17). These were 9-13 cm long, with the head 5.5-7.5 cm long; the facets were 1-1.2 cm wide, and the neck was 1.5-2 cm long. A distinctive feature is the elongated proportions of the head characteristic of the oldest crossbow bolt heads found in Rus’. These were found on Knjazha Gora[61]Dig by N.F. Beljashevskij. Kiev Historical Museum. and in Izjaslavl. Both of these hillforts were destroyed during the Mongol invasion, so we can state that tehse were in use from the late 12th century through 1240.

Type 14: Square in cross section with diamond-shaped facets (Plate 21, item 25). These come in two varieties. They were found in hillforts in the Dnieper Region – Knjazha Gora and Khutor Polovetskij,[62]Dig by V.I. Dovzhenok, 1956. Museum of the Department of Archeology of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences., which were destroyed by the Mongols in 1240. As a result, we can date these to the late 12th-early 13th centuries. The Kiev Museum contains this kind of bolt head from various other spots in the Kiev region.[63]Temnitskij and Creighton Collections. Kiev Historical Museum. They have also been found in Grodno in a 13th-14th century layer,[64]Voronin, op. cit., p. 167, illus. 88, items 2, 6., in the Pskov kremlin in a 13th-15th century layer,[65]Dig by S.A. Tarakanova, 1948. Pskov Museum. and at the hillforts of Tervet and Martinsala.[66]Digs by Brivkalne, 1954-1958.

Type 15: Square in cross section with diamond-shaped facets and cut off corners (Plate 31, item 29). These differ from type 14 in the cut off corners on the lower half of the head. These were widely used in Latvia, where they have been found in the hillfort of Asote dating to the 13th century,[67]Shnore, op. cit., Plate X, item 14., in Mezotne in a 12th-13th century layer, and in Velidona.[68]Museum of the Latvian SSR. In Rus’, with the exception of Novogrudok where they were found in a 13th-14th century layer,[69]Dig by F.D. Gurevich, 1959. these are practically unknown.

Type 16: Diamond-shaped cross section with diamond-shaped facets and cut off corners (Plate 31, item 19). Except for cross-section, these are similar to type 15. These were found in the Mezotne hill fort [70]Museum of the Latvian SSR. and in Riga.[71]Dig by R. Shnore, 1938. Riga Museum. They are almost unknown in the lands of Rus’.

Type 17: Pyramidal, diamond-shaped cross section, with an oval or round neck (Plate 31, item 16). Only one example of this type has been found, in Smolensk in a layer from the 13th-14th centuries.[72]Dig by D.A. Avdusin. Smolensk museum.

Type 18: Keeled, diamond-shaped cross section, without a support for the shaft (Plate 31, item 18). One example has been found in the hillfort of Devichgoro, destroyed by the Mongols in 1240.p[73]Dig by V.V. Geze. Kiev Historical Museum. It appears to have been in use from the late 12th-early 13th century.

Type 19 (Plate 31, item 26). Found in a 13th-14th century layer in Grodno, known only from a drawing published by N.N. Voronin.[74]Voronin, op. cit., illus. 88, item 1.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Savvitov, P.I. “Opisanie starinnykh tsarskikh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, izvlechennykh iz rukopisej arkhiva Moskovskoj Oruzhejnoj Palaty.” Zapiski Arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XLI, 1865, pp. 302, 528; Anuchin, D.N. “O drevnem luke i strelakh.” Trudy V arkheologicheskogo s’ezda v Tiflise. Moscow, 1887, p. 356. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | jeb: With a tripwire? |

| ↟3 | Arab Archery: An Arabic Manuscript of About AD 1500. A Book on the Excellence of the Bow and Arrow and the Description Thereof. Trans. NA Faris and RP Elmer. Princeton, 1945, p. 12. |

| ↟4 | Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej (PSRL). Vol. VIII (Letopis’ po Voskresenskomu spisky) St. Petersburg, 1856, p. 124; Vol. XII (Letopisnyj sbornik imenuemyj Patriarsheju ili Nikonovskoju letopis’ju) St. Petersburg, 1901, p. 842. |

| ↟5 | Demmin, Auguste. Guide des amateurs d’arms et armures. Paris, 1869, p. 490. |

| ↟6 | Polo, Marco, Puteshestvie. Leningrad, 1940, pp. 78, 153. |

| ↟7 | jeb: aka Radziwiłł Chronicle, a manuscript which is believed to be a 15th century copy of a 13th century original. |

| ↟8 | Demmin, op. cit., pp. 495-498. |

| ↟9 | Nadolski, Andrzej. Studia nad uzbrojeniem polskim w X, XI i XII wieku. Lodz, 1954, pp. 65, 194-197, plate XXXII, items 1-4. |

| ↟10 | Noel-Hume, J. Archaeology in Britain. London, 1953, p. 96, plate XIX, item 8. |

| ↟11 | Anuchin, op. cit., p. 356. |

| ↟12 | Rejtenfel’s, Jakov. Skazanie o Moskovii. Moscow, 1905, p. 213; Dmitriev-Sadovnikov, Gr. “Luk vakhovskikh ostjakov i okhota s nim.” Ezhegodnik Tobol’skogo gubernskogo muzeja. Iss. XXIV. 1915, pp. 14-22. |

| ↟13 | Letopis’ po Ipat’evskomu (Ipatskomu) spisku. St. Petersburg, 1871, pp. 543, 563. |

| ↟14 | PSRL, vol. VIII, p. 24; vol. X (Letopisnyj sbornik imenuemyj Patriarsheju ili Nikonovskoju letopis’ju) St. Petersburg, 1885, p. 25. |

| ↟15 | PSRL, vol. XXIV (Tipografskaja letopis’) Petrograd, 1921, pp. 151-152. |

| ↟16 | PSRL, vol. XI (Letopisnyj sbornik imenuemyj Patriarsheju ili Nikonovskoju letopis’ju) St. Petersburg, 1897, p. 75. |

| ↟17 | PSRL, vol. VIII, p. 83. |

| ↟18 | idem., p. 122. |

| ↟19 | jeb: A pischal’ was a medieval Russian firearm, between a cannon and an arquebus. Literally, the word means “squeaker”. |

| ↟20 | PSRL, vol. XVIII (Simeonovskaja letopis’) St. Petersburg, 1910, p. 207. |

| ↟21 | PSRL, vol. XII, p. 149. |

| ↟22 | PSRL, vol. VIII, p. 187. |

| ↟23 | PSRL, vol. XII, p. 149 |

| ↟24 | Voronin, N.N. “Drevnee Grodno.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR. 1954 (41). p. 167, illus. 88-18. |

| ↟25 | Akty Moskovskogo gosudarstva (AMG), vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1894, p. 554. |

| ↟26 | AMG, vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1901, p. 371. |

| ↟27 | The Hermitage, 13/2713. |

| ↟28 | Museum of the Latvian SSR. |

| ↟29 | Digs by M.K. Karger, 1957-1961, Leningrad department of the Institute of Archeology of the USSR Academy of Sciences (LOIA). |

| ↟30 | Dig by D.A. Avdusin, 1957, Smolensk Museum. |

| ↟31 | Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟32 | Dig by M.K. Karger, 1958, LOIA. |

| ↟33 | Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟34 | Voronin, op. cit., Illustration 88, item 8. |

| ↟35 | Temitskij collection, Kiev Historical Museum, No. 21867. |

| ↟36 | Shnore, E.D. Asotskoe gorodische. Riga, 1961, plate X, items 1-2. |

| ↟37 | Digs by Brivkalne, 1954-1958. |

| ↟38 | Stored in the collections of the Riga and Latvia SSR Museums. |

| ↟39 | Dig by E.A. Symonovich, 1953. |

| ↟40 | Symonovich, E.A. “Kamenskij mogil’nik.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury Akademii nauk SSSR. 1956 (65), illus. 36 (the author’s dating is incorrect.). |

| ↟41 | Dig by V.I. Dovzhenok, 1956, Museum of the Institute of Archeology of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. |

| ↟42 | Digs by D.A. Avdusin, 1951-1955. Smolensk museum. |

| ↟43 | Dig by G.P. Grosdilov, 1960. Stored in the Hermitage. |

| ↟44 | Dig by L.V. Alekseev. |

| ↟45 | Voronin, op. cit., 1954, Illustration 88, item 7. |

| ↟46 | Riga Museum, No. 41998/190. |

| ↟47 | Museum of the Latvian SSR. |

| ↟48 | Dig by S.A. Tarakanova, 1948. Pskov Museum. |

| ↟49 | Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟50 | Museum of the Latvian SSR. |

| ↟51 | Symonovich, op. cit. |

| ↟52 | Dig by N.F. Beljashevskij. Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟53 | Museum of the Latvian SSR. |

| ↟54 | Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟55 | Dig by N.F. Beljashevskij. Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟56 | Digs by M.K. Karger, 1959-1960, LOIA. |

| ↟57 | Creighton collection, Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟58 | A dig by D.A. Avdusin, 1951. Smolensk museum. |

| ↟59 | Dig by S.A. Tarakanova, 1948, Pskov Museum. |

| ↟60 | Dig by Leningrad State University, 1938. Hermitage, 13/2713. |

| ↟61 | Dig by N.F. Beljashevskij. Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟62 | Dig by V.I. Dovzhenok, 1956. Museum of the Department of Archeology of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. |

| ↟63 | Temnitskij and Creighton Collections. Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟64 | Voronin, op. cit., p. 167, illus. 88, items 2, 6. |

| ↟65 | Dig by S.A. Tarakanova, 1948. Pskov Museum. |

| ↟66 | Digs by Brivkalne, 1954-1958. |

| ↟67 | Shnore, op. cit., Plate X, item 14. |

| ↟68 | Museum of the Latvian SSR. |

| ↟69 | Dig by F.D. Gurevich, 1959. |

| ↟70 | Museum of the Latvian SSR. |

| ↟71 | Dig by R. Shnore, 1938. Riga Museum. |

| ↟72 | Dig by D.A. Avdusin. Smolensk museum. |

| ↟73 | Dig by V.V. Geze. Kiev Historical Museum. |

| ↟74 | Voronin, op. cit., illus. 88, item 1. |