I am currently reading and translating Kondakov’s book about the Gertrude Codex and its set of Orthodox illuminations, a couple of which depict her son Grand Prince Yaropolk Izyaslavich and his wife. In a previous blog post, I presented the first two parts of the book, a basic historical introduction and a description of each of the illuminations from Gertrude’s prayer book. Part 3 presents an overview of some other items of art which depict the Russian princes and grand princes, for comparison, including fresco murals, icons, other manuscript illuminations, and enameled jewelry. I’ll continue on with Part 4 in another blog post.

Depictions of the Russian Royal Family in 11th-century Miniatures (Part II)

A translation of Кондаков, Н.П. Изображения русской княжеской семьи в миниатюрах XI века. Санкт-Петербург, 1906. / Kondakov, N.P. Izobrazhenija russkoj knjazheskoj sem’i v miniatjurakh XI veka. St. Petersburg, 1906.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here: https://dlib.rsl.ru/viewer/01003735609. ]

Depictions of Prince Yaropolk Izyaslavich in 11th-century Miniatures

Part I – An introduction to the Gertrude Codex

Part II – A review of the miniatures

Part III – A review of other depictions of the Grand Princes and their families

Having arranged the monuments which we have included for comparison in chronological order, we begin their review with depictions of the Grand Prince once located in Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral. St. Sophia’s, according to the Chronicles, was founded in 1037, and painted and decorated in subsequent years during Yaroslav’s rule, and as a result, it can immediately be considered a monument for its paintings. Among the cathedral’s frescoed pictorial art, there evidently were once depictions of Yaroslav himself and his family in the central nave, and as with all the frescoes in the cathedral, they were discovered under the plastered walls in 1843. Over the course of 1848-1853 they were restored, repainted and added on to, such that these dilapidated paintings are considered completely lost, with the exception of one drawing (see illustration 3) which was captured by the restorer, artist and archeologist F.G. Solntsev.[1]A copy of this painting was published in Prokhorov, V.A. Materialy po istorii russkikh odezhd. 1871, plate following p. 60, showing four figures who appear to be Yaroslav’s sons, whose clothes, in particular their hats (which according to Solntsev’s drawing were pointed) significantly differ from Solntsev’s rendering described below and which appears to be closer to historical accuracy. Solntsev’s version lacks style, but is truer to the real depiction, in that his drawing presents in detail the original composition.[2]jeb: There have been numerous attempts to decode these frescos, with quite different results. Most agree that it showed the Grand Prince’s family approaching an enthroned Christ in the center, but disagree on whether these figures on the left were Princess Irene with her daughters, or Prince Yaroslav and his sons (or possibly one daughter, the second figure from the left). See http://sofiyskiy-sobor.polnaya.info/en/sofia_cathedral_mosaics_and_frescoes.shtml for more details on these attempted reconstructions.

Illustration 3: Drawing of the frescoes in Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral. [jeb: Solntsev’s reconstruction]

jeb: Color photo of the remnants of the family portrait fresco from Kiev’s St. Sophia. Photo in public domain.

jeb: One possible reconstruction of the entire fresco from Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral, by S. Vysotsky. The figures immediately to either side of Christ are Grand Prince St. Vladimir the Great, who made Christianity the official state religion of Rus’ in 988, and his grandmother Princess St. Olga of Kiev, the first Russian ruler to adopt Christianity in the 950s. Yaroslav is holding a model church, and his wife stands opposite.

This drawing presents only a shadow of its previous glory, but thanks to Ya.I. Smirov’s persistent search, he was able to reveal a full rendition of this painting in Portfolio No. 176 for the complete collection of drawings (17th cent.) in the Library of the Imperial Academy of Arts. In this album, among other various architectural drawings par excellence, drawing no. 334 shows two rows of figures as if in a long frieze, 5 male and 5 female, approaching a central figure who is dressed in imperial robes, constituting most likely a depiction of Yaroslav and his family before the Byzantine emperor. A detailed study of the entire album of Kievan monuments, to be presented by Ya.I. Smirnov in the near future, but we can judge and discuss this study based on an abstract which he published for the 1904 meeting of the Russian Archaeological Society. This published research will most likely be accompanied by reproductions of the most important drawings, including of course this one. In anticipation of such a complete and clear presentation of this important monument, we can only say a few words about the images themselves. The fact is that if the original images were preserved in this drawing with sufficient fidelity, then of course the real monument would be of decisive importance to us, and without it, it would be impossible to start any kind of analysis in this area. But these images, it appears, were painted quite roughly by their unknown artist, and the drawing can also only be considered to be a distant shadow of the original monument.

As a result, for our current review on this type of depiction of Yaroslav, we would have to accept so many provisional ideas that, at the end of all these calculations, the result itself would also be completely provisional. First of all, it seems entirely uncertain whether Yaroslav, carrying a model of the cathedral, is approaching some unknown emperor, when in that central position it would have been entirely proper to see the Lord Almighty. The only explanation which we could give this circumstance would be that in this place was depicted not the Lord Almighty himself, but His emblematic likeness, St. Sophia of Divine Wisdom, in the form of a royal angel of fiery color, whose imperial robes gave occasion to place the figure of an emperor in this location. All of the remaining figures could likewise be explained as artistic license, a freeform transfer of some of the artist’s memories from the church.

Of particular interest, at the same time, is a major point of doubt: the size of the crown[3]jeb: to avoid confusion, the Prince himself is not shown in the image above, he stood just to the right of the four figures. is characteristic not of the 11th century, but rather at least the 15th or possibly even the 16th-17th centuries. This is a typical princely or ducal crown with a row of crenellations or rays. However, the robes which are worn by the grand princes appear to correctly recall the real Grand Princely attire of the 11th century. Such is the mantle or long cape of brocade worn on Yaroslav himself, embroidered with eagles within circles. Capes and robes with this design worn in Byzantium had a special name, orlov[4]jeb: from Rus. орёл, oryol, “eagle”, and became part of the dress of the highest dignitaries in the Byzantine court. The cape is trimmed with wide band of gold, seeded with precious stones (about such borders, see below). His primary caftan is gathered by a wide belt, has narrow sleeves, and is decorated with golden trim at the hem and wrist.

Behind Yaroslav, we see his eldest son,[5]jeb: This is the figure on the far right in Illustration 3. wearing a caftan decorated with circles, but without any detail on what would have been embroidered inside the circles. The caftan is belted, and over it he wears some kind of short cape, thrown back over the shoulder, but the ends where the cape would have been fastened by a clasp [Rus. аграф, agraf] or possibly some kind of collar is not shown. Given the wide trim on the caftan, the ornamental design is of a typical Byzantine type. This son’s headgear is a fur cap, apparently made of sable, decorated at the crown with crossed rows of large pearls. The following son is depicted in the same cloak as his father, decorated with circles. The fourth is wearing a wide outer garment (possibly a Russian platno[6]It is also possible that this comes from the Byzantine πλατάνιον / platanion. See Vykhody russkikh tsarej from 1659: “A platno of golden brocade, embroidered with golden crowns.”), decorated with circles and equipped with a collar and with wide bands of gold throughout. Finally, the last son is again shown dressed in a cloak.

Yaroslav’s wife has a crown, under which which she has a veil or maphorion which covers the back of her head and neck; over this, she wears the same kind of royal cape with wide trim, decorated with the same design and almost the same kind of outer wear as her husband’s caftan, decorated with trim. The daughter immediately behind her is shown in a fur princely cap, worn over a veil. Over her belted dress, she has the same kind of princely cap, but the clothing itself has wider sleeves, much like a dalmatic. The three daughters behind her are dressed identically to the corresponding sons, with sleeves which are once again narrow. As such, this entire series of depictions does not provide, in essence, any strong points for discussing other monuments, and quite the opposite, needs diverse guidance in a critical analysis of its own details.

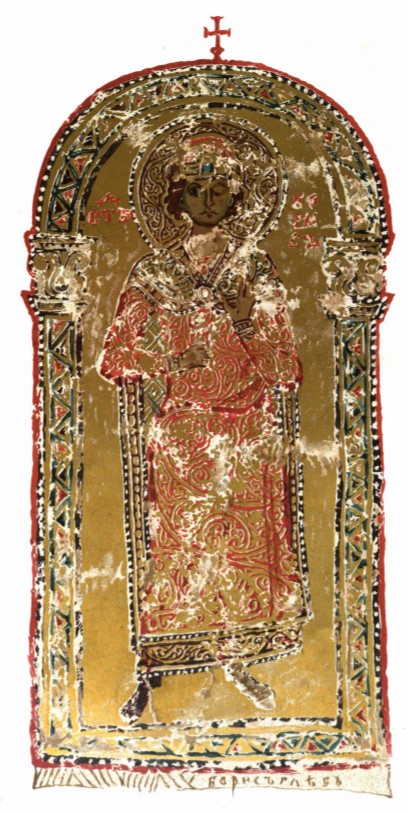

In the same building, on the right pillar of the cathedral, there is a depiction of St. Constantine the Great, with the figures of the prince and princess on either side at a reduced scale. Unfortunately, the frescoes in this location were completely painted over by the Solntsev’s artists and, as a result, to rely on various details of these depictions would be risky. The Prince (or Grand Prince) is shown without a beard, first of all, which in itself is understandable only from the conventional figures of saints, and wears a simple princely crown, that is, a round cloth hat, decorated at the brim with a golden band, which also runs over the red top in the shape of a cross. He also wears a dark-green cloak or chlamys decorated with trim, attesting to his royal dignity. He holds a scepter and a scroll, which could be part of the original or date to the restoration. A female figure wears on her head a maphorion or veil, which is topped by a golden crown in the form of a metallic hoop with precious stones. She is dressed in a light blue dalmatic, decorated with a golden collar and an imperial loros, the end of which has been made into the shape of a shield (a thorakion [Rus. форакия, forakija, from Gr. θωράκιον, thorakion, “armor”], see below), which she holds before her.

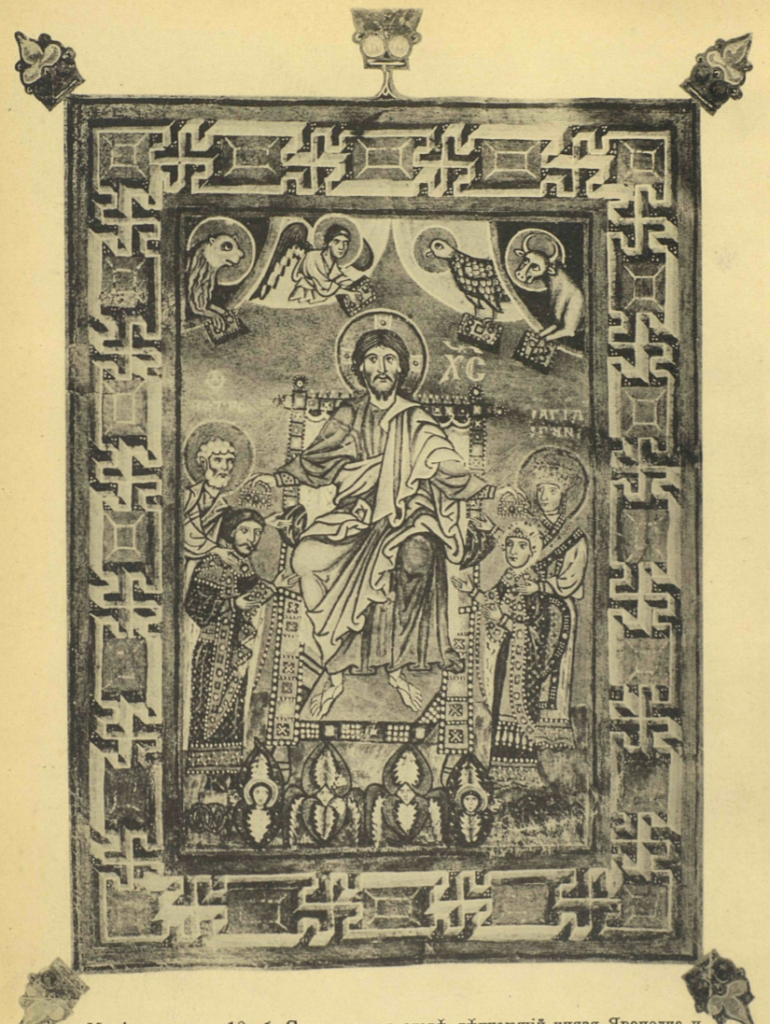

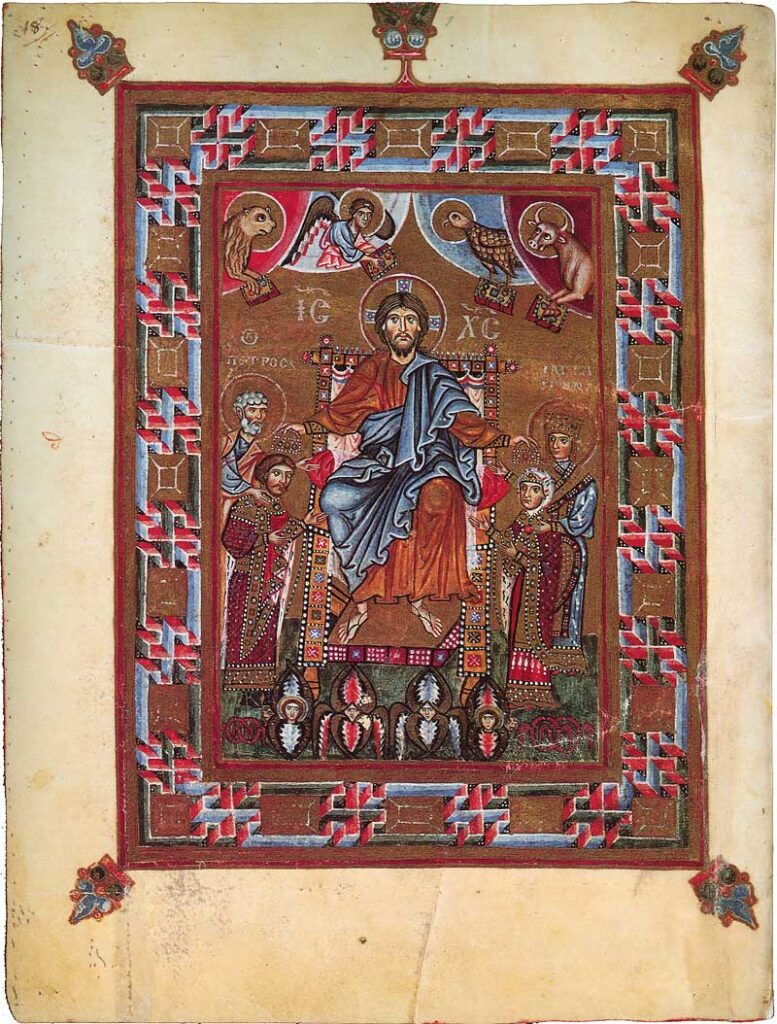

The title picture from the Izbornik, written in 1073 for Grand Prince Svyatoslav Yaroslavich[7]The Izbornik was discovered in 1817, but around 1834, this carpet page happened to be discovered in storage in the Moscow Armory, while the manuscript itself was in the Moscow Synodal Library. The illumination was reproduced at Olenin’s order by F.G. Solntsev, according to both with complete accuracy, like a facsimile. This copy was reproduced by V. Prokhorov in Materialakh po istorii russkikh odezd in 1871, on page 66, and in a publication of the Izborni velikogo knjazja Svjatoslava Jaroslavicha 1073 goda by the Society of the Lovers of Ancient Writing in 1880., may be, in fairness, called the most important monument of medieval Russian life, and deserves careful consideration.

Above the illumination there is an excerpt from the Psalm of David: “O Lord, do not despise the desires of my heart, accept us all and have mercy on us.” Grand Prince Svyatoslav is shown at the head of his family, approaching the Savior. Christ is shown seated, making a blessing sign with one hand. Above the prince, an inscription lists all the members of his family (see Illustration 4).

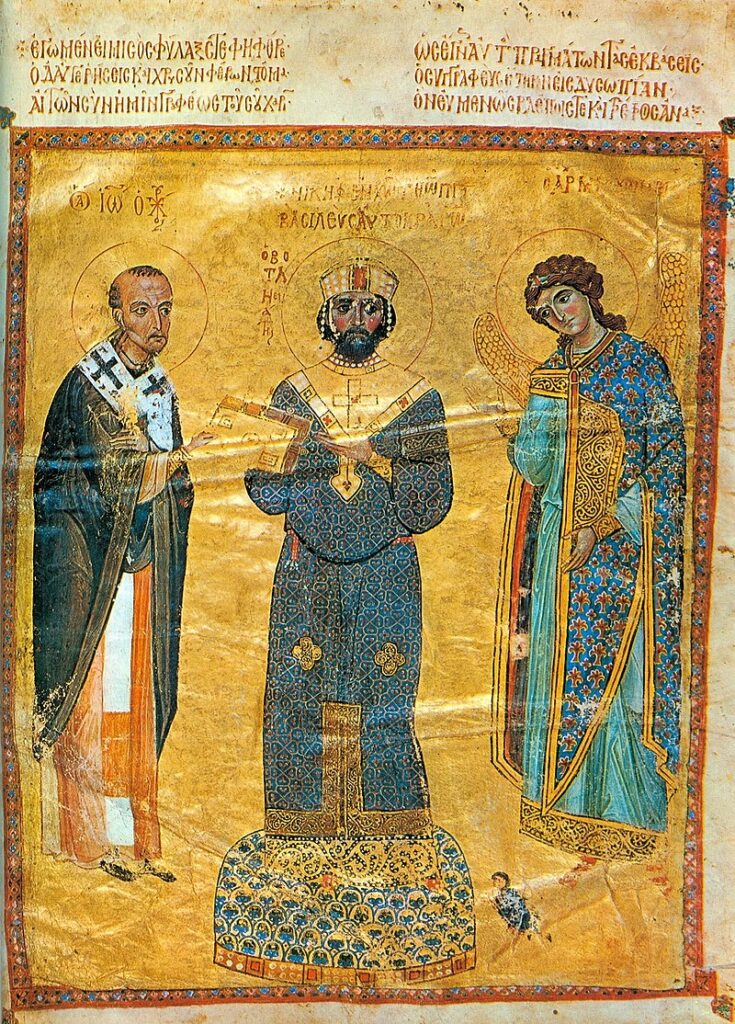

The Grand Prince is shown in a sable hat, with a crown of gold cloth and with earflaps raised and folded behind the fur trim. He is wearing a large cloak with wide gold borders and a ruby clasp at his right shoulder. The cloak is dark blue, that is, violet or purple, with a red or scarlet lining. His caftan is of the same dark blue color, with narrow sleeves, cuffs of gold brocade, and wide, red trim at the hem. The caftan is belted. The prince’s boots are of soft, green leather. As such, Svyatoslav’s clothing cannot be called “purely Russian,” as V.A. Prokhorov concluded: we can accurately establish in this chapter[8]jeb:??? – в ближайшем отделе that all of these clothes belong to the category of vestments, or in our term, a sort of uniform that came into use in the Byzantine court. The Prince’s wife is dressed in a bright red dress, belted and furnished with very wide sleeves. These sleeves are also almost doubled in length, and having been tied to the arm above the elbow, puff out over the elbow, and then become narrow at the wrist and are gathered by special cuffs of gold brocade. It appears that this is the same kind of dalmatic which was most often encountered among female court attire, with the one possible difference that here this outfit appears to be worn as a zipun[9]jeb: Rus., зипун, an item of Russian outerwear, resembling a collar-less caftan.. It is decorated with an oplech’e[10]jeb: Rus., оплечье, a wide detachable collar worn flat over the shoulders., a wide gold belt, and with trim at the hem. On her head she wears, firstly, a veil which is wrapped around her head such that one end falls to her right shoulder; over the veil, she wears a tall fur hat or cap, which has no brim at all and is conical in shape, similar to a Little Russian Cossack hat. All of Svyatoslav’s sons, including the youngest, wear the same kind of fur hat. They are all dressed in scarlet caftans, with gold belts, the ends of which fall to either side with gold braid. The caftans have gold cuffs. The most curious part of the sons’ clothing seems not quite clear: this is a sort of attached collar of gold brocade which appears to replace their metallic torcs, in the form of a small hoop which encircles the neck. It would have been more natural to see this as a fitted fur collar, a prototype of the later kozyr’.[11]jeb: A tall standing collar which stood behind the head, commonly worn in the 16th-17th centuries. Finally, on the youngest son’s caftan, we can clearly see sewn-on clasps on his chest, running all the way to his waist, made from gold braid. These kinds of decorations were also seen on Byzantine garments, as we can see from the miniature with a portrait of Nicephorus III Botaniates described below [jeb: See image].

An image of Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich of Novgorod, builder of the Spas-Nereditsa Church (1198) (see Illustration 5), is located on the southern wall inside a type of niche which were arranged in Greek churches from the 10th-12th centuries over the tombs of ktetors[12]jeb: a title given in the Middle Ages to the provider of funds for construction or reconstruction of an Orthodox church or monastery, for the addition of icons, frescos, and other works of art., who were customarily buried in the southern nave or narthex. The prince is shown bringing a model of the church to the Savior, who is seated upon a throne. The prince wears a sable hat with a light blue upper. His crimson cloak is of expensive brocade, embroidered with large concentric circles containing eagles and is bordered by a wide band completely strewn with pearls. Over it, he wears a golden oplech’e. Beneath his cloak, we can see a light-blue caftan with a wide band of crimson at the hem. His tall boots and pants are of two colors: light blue and yellow. He has embroidery on his cuffs and at the collar.

Grand Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich became ruler of Novgorod in 1182, was later driven out of the city, but returned to Novgorod in 1197. The depiction of the prince and Archbishop Martiriy was created, most likely, in 1199, when Yaroslav had once again been accepted as ruler and when the archbishop died. This image, according to Prokhorov’s testimony,[13]Russkie Drevnosti. Vol. 4, 1871, p. 35 w/ plate. suffers from a major alteration: under the outer depiction of the prince’s head, Prokhorov uncovered a different face, older, painted in the late 12th century. Whereas the former, erased face of the prince had a grey beard and hair, the newly uncovered head had a dark brown beard and long brown hair. Upon his head was the aforementioned hat. As such, we have here, aside from the fur hat which deserves further discussion, a typically Byzantine outfit of one of the highest patrician ranks completely corresponding to that of a Grand Prince. Therefore, there is no reason to consider this sort of attire to be Russian national clothing; if we were to decide, for example, to call his cloak a korzno, we would be able to conclude from this appellation any details about its folk Russian character or, importantly, about the national origin of this item of clothing.

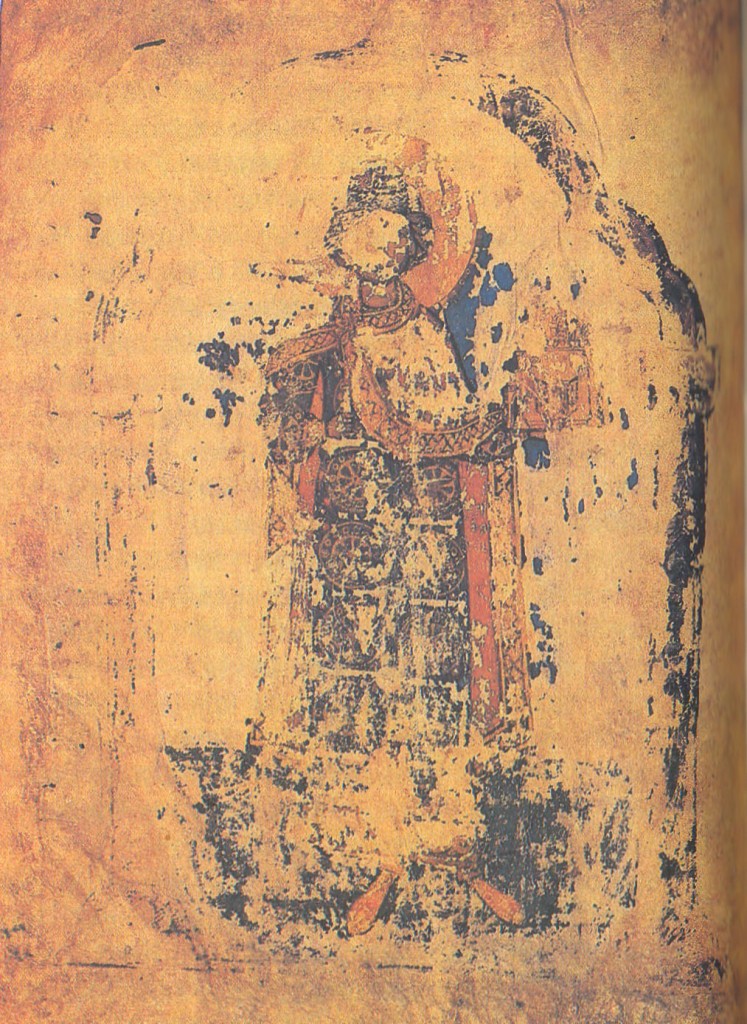

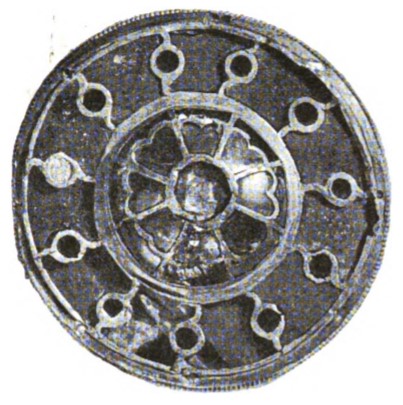

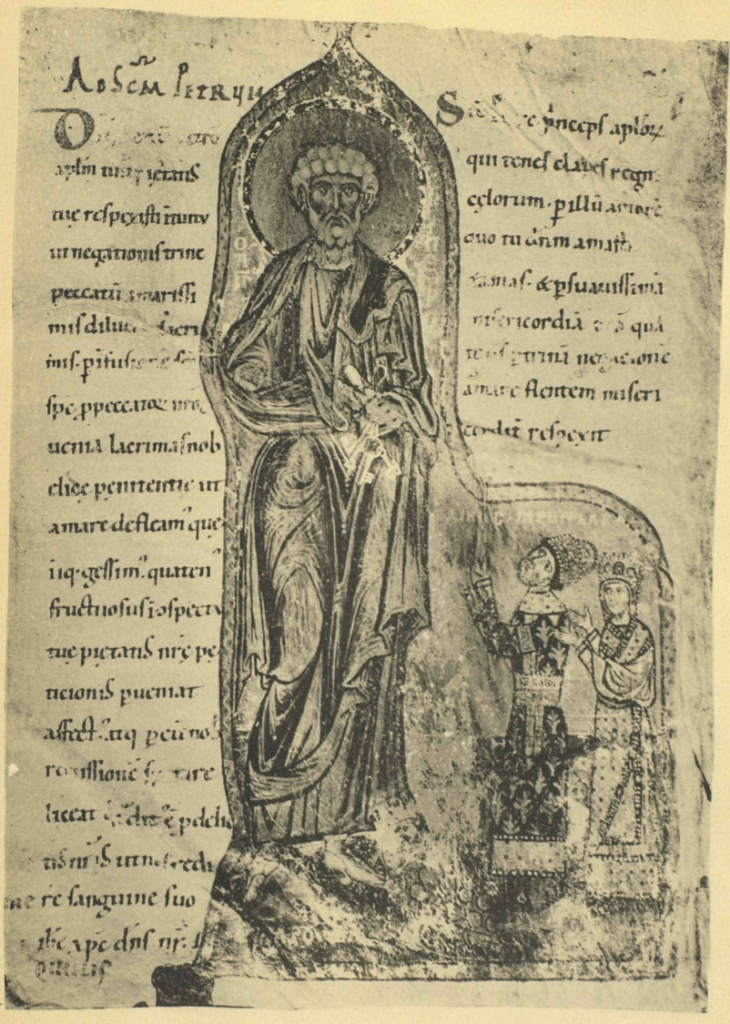

The 12th century is, generally speaking, richer in depictions than the 11th, and since the monument we are examining dates to the late 11th century, we have good reason to compare it to analogous monuments from the 12th century. First of all, let’s look at a depiction of a Russian prince from a manuscript of Hippolytus of Rome’s Sermon on Christ and the Antichrist dating to the 12th century, painted on parchment and preserved in the Chudov Monastery. As the prince here is depicted holding a model of a church, we can assume this is one of a series of such images showing a prince bringing a model church before the Savior. This unknown prince is depicted in a long brocade cloak decorated with figurative images, but because of the poor state of the miniature, their colors have not been preserved; the cloak has a scarlet lining and wide gold trim. This caftan or kabbadion is belted in exactly the same way as the aforementioned image of Nicephorus III Botaniates [jeb: See image], and is decorated with circles containing a curious design. The circles contain a sort of rosette, divided into a schematic star shape, similar to that found on early medieval sewn-on plaques.[14]Tolstoj, I., Kondakov, N. Russkie Drevnosti v pamjatnikakh iskusstva, iss. III, St. Petersburg, 1890, illus. 166 (p. 141). [jeb: See image below.] The prince’s boots, of soft, red leather, are embroidered and have the same Byzantine character. In other words, here again we do not find any special “Russian” cape or korzno, as was stated by Prokhorov, the publisher of this monument. In his opinion, the prince is shown wearing a Russian summer hat, with a band not of fur, but of golden cloth, and with an upper which was decorated with patterns like those seen on Sts. Boris and Gleb. The prince is shown holding a small cross in his right hand, like those commonly shown behind held by martyred saints. The scholar Sreznevskij[15]Zapiski Imperatorskoj Adakemii Nauk, vol. IX, book 1. proposed that were we see depicted Vsevolod Gavriil, prince of Novgorod and son of Mstislav, who died in 1137 and was sainted in 1192. In our opinion, it is not necessary to determine which of the 12th century sainted princes this is, in order to determine that this image as is follows. Firstly, the cross in his hand could easily be a later addition, meant to imitate St. Boris; and secondly, the cross in the hands of a prince who is bringing a model of a church which he has had built before the Savior, which in itself a custom borrowed from the Byzantine emperors seen during holiday services, as described by Kodinos.[16]Kodinos, De officiis, Chapter VI , pp. 51-52.

Illustration 6: Depiction of a prince from Hippolytus of Rome’s Sermon on Christ and the Antichrist. 12th century.

jeb: Color image of the depiction of a prince, from Hyppolytus of Rome’s Sermon. Image in public domain.

jeb: Encrusted rosette plaque from the Chulek find. Image from Tolstoj, I., Kondakov, N. Russkie Drevnosti v pamjatnikakh iskusstva, iss. III, St. Petersburg, 1890, p. 141, illus. 166.

We also would like to tie in an image of St. Boris in a miniature from a 13th century manuscript of A Lesson from Conversations with St. John Chrysostom in the [Moscow] Synodal Library and published by V.V. Stasov.[17]Stasov, V.V. Miniatjury nekotorykh rukopisej vizantijskikh, bolgarskikh russkikh, dzhagatajskikh, i persidskikh. 1940, pp. 89-92, plate IV. [jeb: see image] The inscription over the depiction indicates this is St. Boris, but the scholar strongly rejects this, and proposes that this is the Russian prince Boris-Mikhail, the Bulgarian prince who Christianized his nation in 907. In this illumination, the prince is also holding in his right hand a cross, the sign of a martyr. It is Stasov’s further conclusion that in this case, the Russian martyred Prince Boris is depicted. “This image of Prince Boris,” Stasov writes, “is in all details identical or closely related to a multitude of images of St. Boris. Its original source is, without a doubt, Byzantine, but here we also see several Russian traits. Prince Boris is dressed in a long, narrow caftan sewn from gold brocade with gold spiral patterns. At the hem, his caftan is decorated with a wide gold braid, in the form of a Byzantine garland against a black background. At his wrists, we see gold cuffs with a blackened or niellated pattern. Over his caftan, Boris does not wear the typical korzno (or short cape) fastened at the right shoulder (as seen with all Byzantines and medical Russian princes in Byzantine attire) with a large brooch with a precious stone in the center; instead, the prince has thrown a long, wide, dark-blue cloak over his shoulder, with a braid or trim of gold and silver circles against a black background. Upon his feed, the prince wears books, the color of which cannot be determined as a result of the paint peeling. Upon his head is a hat, rounded on top, with a red upper and a gold band, in the center of which, above the forehead, there is a large precious stone, apparently an emerald. This is a summer hat, without fur.”

The question about how many truly Russian traits we see in Grand Princely attire, which according to Stasov were based on originally Byzantine trends, is so difficult that it can only be answered by a review of each detail. And as this monograph intends to subject each of the major parts of this attire to separate consideration (hats, cloaks, caftans, boots, etc.), at this time it is necessary to analyze not these parts, but their specific characteristic variants, which will then need to be analyzed one by one. In this instance, this feature is the prince’s cloak which attracted Stasov’s attention. First of all, from the same drawing published in Stasov’s book, it is easy to determine the color of the cloak: an ashy light blue or bright grey, covered throughout with gold designs. It appears here that this bluish color represents the ground color of the fabric, embroidered with gold, but this can also be seen as a typical contrast used in attire of the 12th-13th centuries: everywhere in Byzantine miniatures, we find this typical variation of two basic, complementary colors on caftans and capes. If a caftan is red, then the cloak might be dark blue, dark violet, or light blue; likewise, if the cloak is crimson, then the caftan might be light blue, bright green, etc. In this case, given the brick-red color of the caftan, the ashy-lilac color of the cloak is a natural choice. But, the trim on both the cloak and the caftan is the same: a brick-red/chocolate tone, that is, ancient purple. Secondly, this cloak is of a different cut than Svyatoslav’s cloak or korzno. It is true that we so frequently encounter this type of cloak in Byzantine and Western garb, such that we cannot consider it to be only Russian. Furthermore, by our measurements, this cloak is no longer or wider than the cloak shown on Svyatoslav, but it is of a completely different pattern. Specifically, this cloak [Rus. plasch], pinned at the right shoulder, is in the shape of a long, rectangular cover, customarily made from thick wool fabric as an accessory of military life, and is the clothing of a commander rather than an emperor. A cape [Rus. mantija], on the other hand, which is pinned at the chest, is not large enough to completely cover the body in order to conserve heat, and serves only as a decorative garment and as such is not rectangular, but rather is a semicircular cape with a large opening at the neck such that the two ends of this opening can be pinned together at the chest. The length of these panels should be adjusted based on the person’s side, since it is settled upon the shoulders and should cover the entire figure from behind. Further, it is also understood that the fabric for this mantija should be thin, since if it were made of thick or heavy material, gathered in small folks around the figure, it would be extremely heavy. For this reason, it is necessary to determine the difference in the character of these two types of cloak: the military plasch and the decorative mantija. However, in every instance, the cloak may not be a sign of any Russian character in dress, since we know similar mantles made of expensive silk and decorated with figurative designs exist in the regalia of the Norman kinds of Sicily. Whether a prince’s hat can be considered a Russian trait of dress shall be reviewed below.

The widespread veneration in pre-Mongol Rus’ for the Sts. Boris and Gleb, who were martyred and became moral ideals for the retinue class was the reason for the early appearance of their images in Russian iconography. As a result, the earliest forms of Boris and Gleb were preserved, as seen, for example, in cloisonné enamel and manuscript illuminations. Since this type of artistic production completely came to a halt with the Mongol invasion, we have the opportunity to limit ourselves to an analysis of these most important and eldest monuments, including: an image of Sts. Boris and Gleb on two large earrings from the 1822 Ryazan’ hoard; two small images in the form of small icons on the cover of the Mstislav Gospel; an image on a suspended icon torc found in 1904 in the Radomysl district; and finally in numerous manuscript illuminations, the 13th century frescos in the Church of St. Nicholas on Lipno Island near Novgorod, etc. Particularly realistic are enameled images from the 12th century preserved either in treasure hoards or, as with the cover on the Mstislav Gospel, already in medieval times due to their rarity. As for the also quite rare fresco images, like the ones from the Church of St. Nicholas on Lipno (cf. Prokhorov, Russkie Drevnosti, 1871, vol. IV), those images present an understandable tendency toward a complication of costume and attire, due to a desire to focus on the depiction of all everyday decorations available to the icon painter.

But, if enamel images of Boris and Gleb are more realistic depictions of Grand Princely clothing, then they stand out at the same time for their monotony and schematism, which require prolonged study of each detail in order to reveal the realism beneath. Such is the case, for example, with how these enamels depict princely hats. We see in them, first of all, fur brims of dark chestnut or brown color, apparently sable fur; but sometimes, this brim is light green or even ash colored which is much harder to define, as this could be seen as fabric or even some kind of fur, for example, ermine (white is depicted in enamel using ash-blue).[18]Russkie klady, vol. 1, p. 16. An accurate drawing of the Ryazan’ kolt. Sometimes, the brim is shown in gold, that is, made from gold fabric and strewn with precious stones and with a forehead-mount [Rus. очелье-киотик, ochel’e-kiotik, “headband-icon”] of one or three stones or even a figurative depiction which, of course, due to the small size and schematism of the portrait, the enameller is unable to fully portray, as we will see below in our review of crowns and circlets. Just as diverse is the depiction of the tops of hats, which may be semi-circular, or slightly conical (or cucumber-shaped, as in Byzantine variants), or even pointed, which is clearly of Eastern origin. These tops’ colors are typically either shown in gold, or vary from ash-grey to red. If this crown is of colored material, then it is frequently decorated with a gold cross, decorated with gems in settings. Sometimes, the sides are decorated with pearls. We should add that nowhere do we find hats of a purely Byzantine character, strewn along the borders with individual pearls or with couched strings of pearls. Sometimes over the brow, above the brim, we see a rod used for fastening a feather (a so-called tash [Rus. таш]).

The cape typically depicted on these enamels is shown as commander’s rectangular cloak or stratigon, decorated with woven or embroidered kriny (stylized lilies) or red ivy leaves (see our earlier discourse on this type of fabric in Byzantium). We shall not review the other details of these outfits, as their details are not overly realistic.

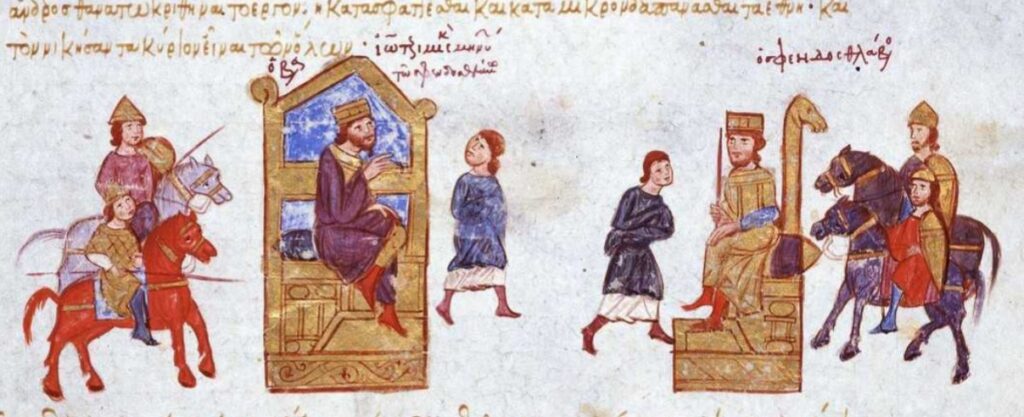

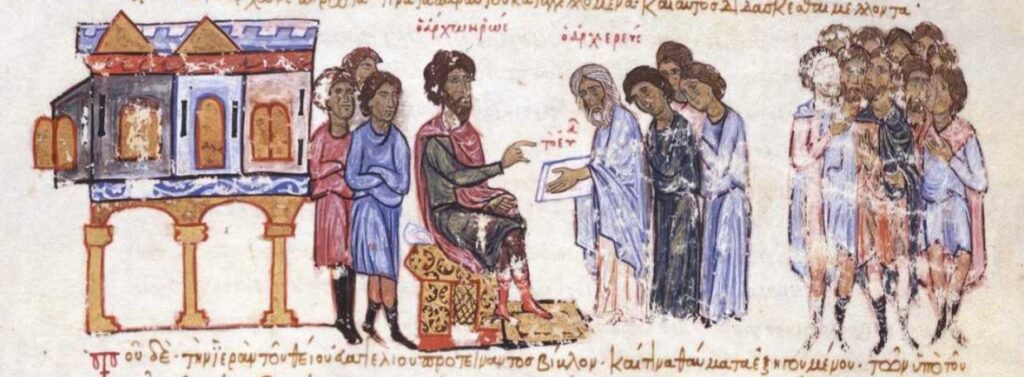

Depictions of Russian princes are just as schematic and conventional in illuminations from medieval manuscripts, for example, those which I published in the book Russkie klady from the manuscript by John Skylitzes [jeb: See images below] located in the National Library of Madrid written by one scribe in the 14th century, but illustrated by several illuminators from various originals (see images I, 41, 95, 122). In the manuscript there are up to 20 illuminations depicting Olga’s reception in Byzantium, wars of the Greeks against the Rus’, Svyatoslav’s campaigns, negotiations with Prince Vladimir, etc. These illuminations, as always, are quite stylized and avoid all characteristic details. Most commonly, therefore, an illumination will present Prince Svyatoslav simply in royal attire, with little distinction from that of the Byzantine emperor. For example, during Svyatoslav’s meeting with John I Tzimiskes, both are shown in identical outfits. The only difference is that Tzimiskes sits on a large throne under a baldachin, while Svyatoslav sits before him on a bench, but both have crowns upon their heads and typical cloaks over their shoulders. But, next to him, Svyatoslav’s nobles are depicted in hats with white and yellow (that is, gold) crowns, like those worn by Boris and Gleb.

jeb: Illumination from the Madrid Skylitzes. Prince Svyatoslav I’s meeting with Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes. Image in public domain.

jeb: Illumination from the Madrid Skylitzes. John I Tzimiskes and Svyatoslav I. Image in public domain.

jeb: Illumination from the Madrid Skylitzes. Miracle of the Gospel thrown on the fire before the Rus’ archon. Image in public domain.

On the other hand, in the miniatures from the Radziwiłł (or Königsberg) Chronicle,[19]Radzivilovskaja ili Kenigsbergskaja letopis’, izd. Obschestva Ljubitelej Drevnej Pis’mennosti 1902 g., fotomekhanicheskoe vosproizvedenie rukopisi. one thing is characteristic, which is that Russian princes and grand princes are never shown in royal vestments, while the Greek emperors are always shown wearing a crown, that is, a sort of circlet with points. Princes are depicted in long, multi-colored caftans, belted at the waist, with oplech’e and wide bands of trim at the hem and armbands. Upon their heads we see cloth hats, semicircular in shape, most commonly in the form of a conical cap with fur trim. But then the princes and their close boyars (starting with Oleg and Igor, on folio 18 and forward) are depicted in the familiar hat, with a fur brim and bands set with stones. This type of band on the princely cap aren’t shown in a cross shape, as usual, but rather in the form of oblique bows (folios 67, 105). Grand Prince Svyatoslav is even shown in a special kind of turban reminiscent of other sorts of Byzantine headwear called tufy, and in a wide, ermine cloak.

jeb: Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 9 obv. Askol’d and Dir travel to Byzantium and meet with Emperor Michael.

jeb: Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 26. Igor’ receives the Russians and the Greek ambassadors to work out a peace treaty. Note the rounded Rus’ hats with fur trim.

jeb: Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 32. Olga refuses Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus’s offer of marriage. Note the emperor’s crown, as opposed to those shown on the Rus’ princes in other images.

jeb: Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 39 obv. Byzantine emperor John I Tzimiskes receives ambassadors sent by Svyatoslav Igorevich. Contrast to the Byzantine illumination above.

jeb: Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 67 obv. Building the city of Belgorod at the behest of Vladimir Svyatoslavich. Note the oblique lines on Vladimir’s hat, as mentioned by the author.

jeb: Radziwiłł Chronicle, folio 115. Svyatoslav Yaroslavich of Kiev showing his wealth to the German ambassadors. Note the prince’s odd headwear and his sumptuous coat lined and trimmed with furs.

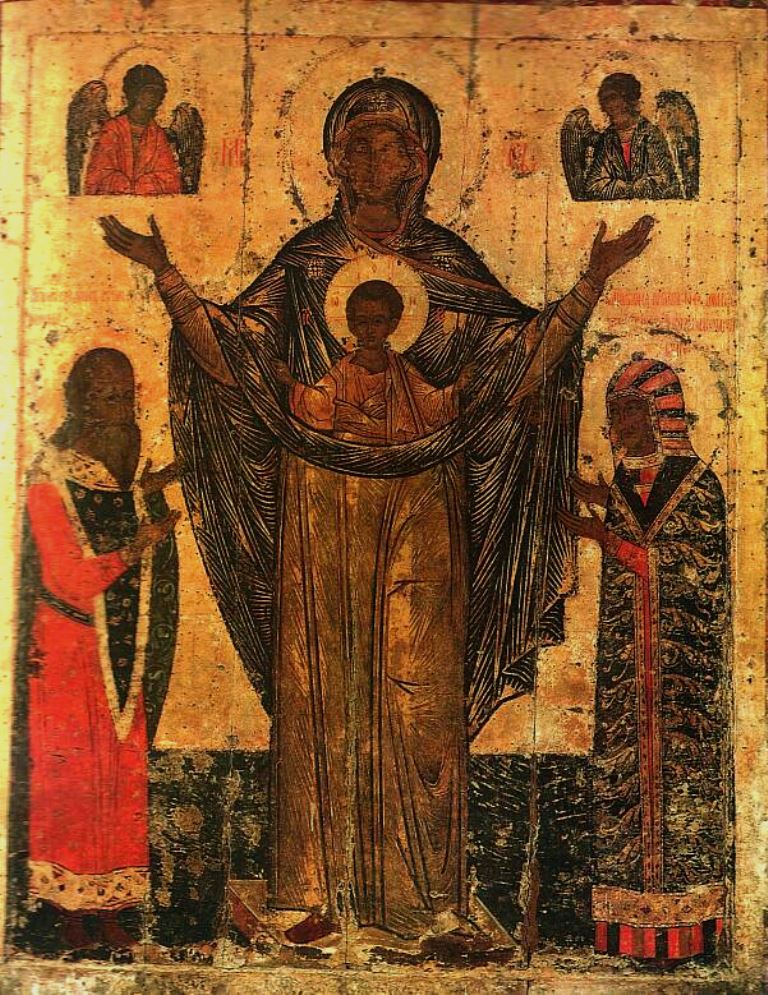

The images of princes from the pre-Mongol period preserved on some ancient icons, unfortunately, turn out to be either of later origin or later alterations, such as, for example, the image of Pskov Prince Dovmont and his wife on an icon of the Sign of the Blessed Virgin in Pskov’s Mirozhsky Monastery. In this case, only the princess’ outfit is of interest, in the form of a brocade opashen’, buttoned in front, with a striped dress underneath and a striped veil on her head.[20]Russkie Drevnosti, Vol. VI, 1871.

jeb: The Miraculous Icon of the Blessed Virgin, from Pskov’s Mirozhsky Monastery. Image in public domain.

jeb: Coin depicting Vladimir the Great. Image in public domain.

We have left for last one type of monument which was earlier considered to be most important in terms of everyday visual indicators for medieval barbarian states: its coins. The reason for this delay is their extreme conventionality of depiction, resulting from the stamping process, which decidedly does not allow any sort of data to be extracted which we could use for the analysis of other monuments. On coins minted by Vladimir and Yaroslav, the Kievan princes are shown on thrones wearing regal attire and crowns, and these crowns, often designated only by a band of pearls with a pearl cross above, are a common technique of depicting sovereigns on barbarian imitations of Byzantine coins depicting emperors.[21]Engel, A and Serrure, R. Traité de numismatique au moyen âge. Paris, 1891, I fig. 642. In short, an analysis of clothing from coins could be produced with the assistance of precise archaeological data obtained from various archaeological sites, but not the other way around.

Part IV – What these images tell us about what Russian Princes actually wore

To follow soon in another blog post.

The Plates

See Chapter II for a description of each of these plates.

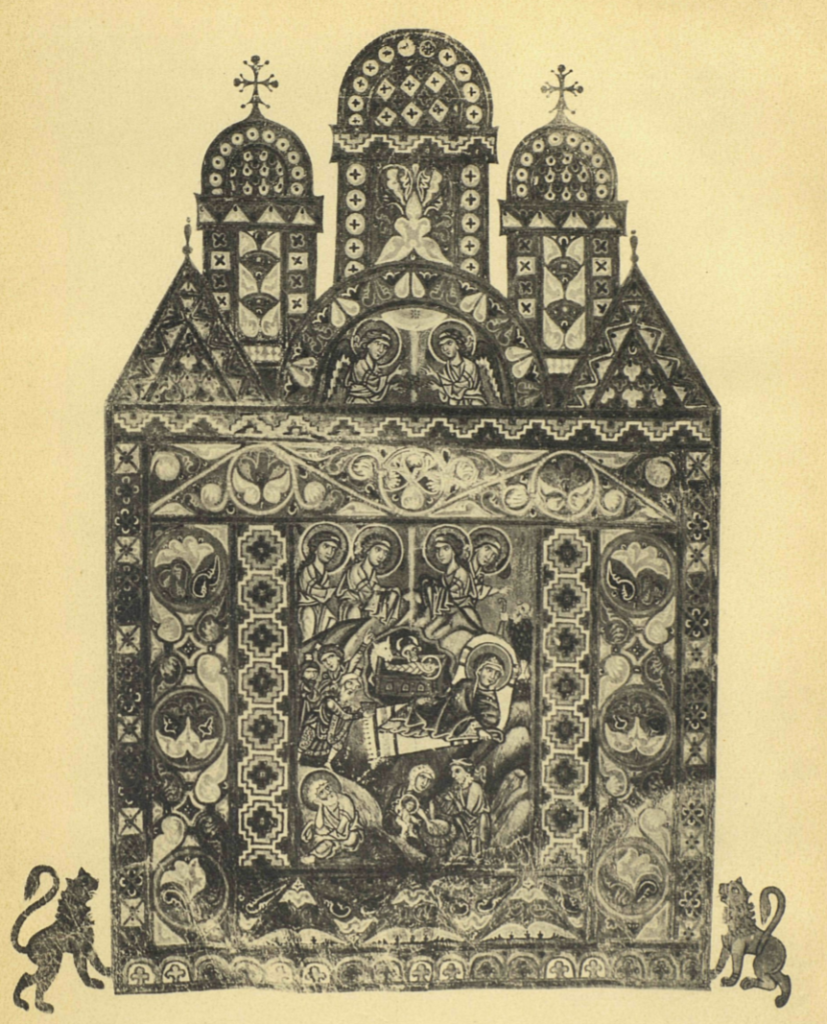

Plates #1 and #6

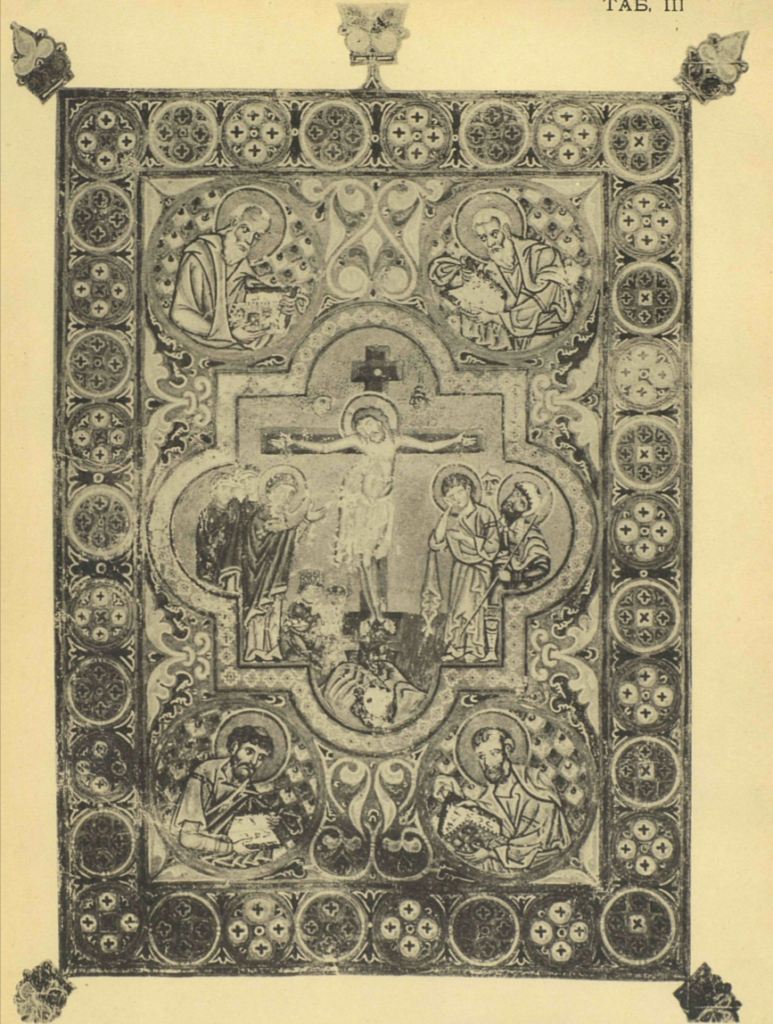

Plate #2

Plate #3

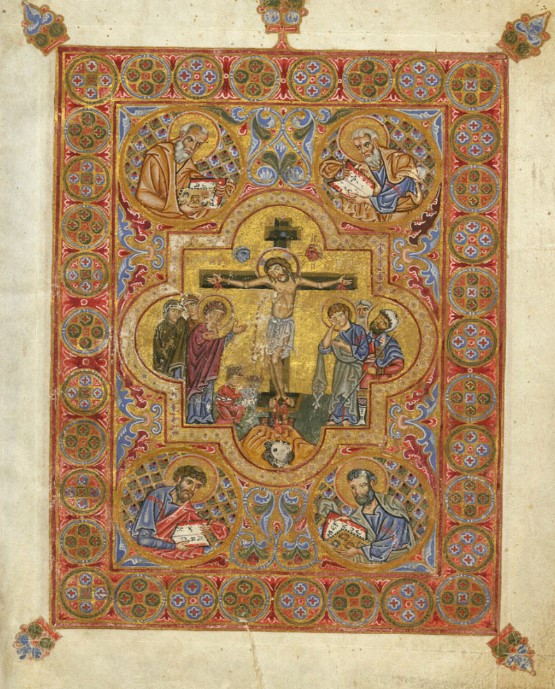

Plate 3: Miniature on folio 10: The Crucifixion of the Lord, and the Evangelists.

jeb: Color image of the Crucifixion. Image in public domain.

Plate #4

Plate #5

Footnotes

| ↟1 | A copy of this painting was published in Prokhorov, V.A. Materialy po istorii russkikh odezhd. 1871, plate following p. 60, showing four figures who appear to be Yaroslav’s sons, whose clothes, in particular their hats (which according to Solntsev’s drawing were pointed) significantly differ from Solntsev’s rendering described below and which appears to be closer to historical accuracy. Solntsev’s version lacks style, but is truer to the real depiction, in that his drawing presents in detail the original composition. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | jeb: There have been numerous attempts to decode these frescos, with quite different results. Most agree that it showed the Grand Prince’s family approaching an enthroned Christ in the center, but disagree on whether these figures on the left were Princess Irene with her daughters, or Prince Yaroslav and his sons (or possibly one daughter, the second figure from the left). See http://sofiyskiy-sobor.polnaya.info/en/sofia_cathedral_mosaics_and_frescoes.shtml for more details on these attempted reconstructions. |

| ↟3 | jeb: to avoid confusion, the Prince himself is not shown in the image above, he stood just to the right of the four figures. |

| ↟4 | jeb: from Rus. орёл, oryol, “eagle” |

| ↟5 | jeb: This is the figure on the far right in Illustration 3. |

| ↟6 | It is also possible that this comes from the Byzantine πλατάνιον / platanion. See Vykhody russkikh tsarej from 1659: “A platno of golden brocade, embroidered with golden crowns.” |

| ↟7 | The Izbornik was discovered in 1817, but around 1834, this carpet page happened to be discovered in storage in the Moscow Armory, while the manuscript itself was in the Moscow Synodal Library. The illumination was reproduced at Olenin’s order by F.G. Solntsev, according to both with complete accuracy, like a facsimile. This copy was reproduced by V. Prokhorov in Materialakh po istorii russkikh odezd in 1871, on page 66, and in a publication of the Izborni velikogo knjazja Svjatoslava Jaroslavicha 1073 goda by the Society of the Lovers of Ancient Writing in 1880. |

| ↟8 | jeb:??? – в ближайшем отделе |

| ↟9 | jeb: Rus., зипун, an item of Russian outerwear, resembling a collar-less caftan. |

| ↟10 | jeb: Rus., оплечье, a wide detachable collar worn flat over the shoulders. |

| ↟11 | jeb: A tall standing collar which stood behind the head, commonly worn in the 16th-17th centuries. |

| ↟12 | jeb: a title given in the Middle Ages to the provider of funds for construction or reconstruction of an Orthodox church or monastery, for the addition of icons, frescos, and other works of art. |

| ↟13 | Russkie Drevnosti. Vol. 4, 1871, p. 35 w/ plate. |

| ↟14 | Tolstoj, I., Kondakov, N. Russkie Drevnosti v pamjatnikakh iskusstva, iss. III, St. Petersburg, 1890, illus. 166 (p. 141). |

| ↟15 | Zapiski Imperatorskoj Adakemii Nauk, vol. IX, book 1. |

| ↟16 | Kodinos, De officiis, Chapter VI , pp. 51-52. |

| ↟17 | Stasov, V.V. Miniatjury nekotorykh rukopisej vizantijskikh, bolgarskikh russkikh, dzhagatajskikh, i persidskikh. 1940, pp. 89-92, plate IV. |

| ↟18 | Russkie klady, vol. 1, p. 16. An accurate drawing of the Ryazan’ kolt. |

| ↟19 | Radzivilovskaja ili Kenigsbergskaja letopis’, izd. Obschestva Ljubitelej Drevnej Pis’mennosti 1902 g., fotomekhanicheskoe vosproizvedenie rukopisi. |

| ↟20 | Russkie Drevnosti, Vol. VI, 1871. |

| ↟21 | Engel, A and Serrure, R. Traité de numismatique au moyen âge. Paris, 1891, I fig. 642. |