After reading a few sources about Novgorod’s jewelry production industry, I was interested in seeing how it sized up against jewelry from other Russian cities. Novgorod was near unique in that it managed to escape the worst of the Mongol invasion, which interrupted and halted development in most of the other cities of Rus’ from the 13th-15th centuries. At the same time, Kiev was in decline, with its power having been fragmented among a number of city-states. This was a time, however, of artistic invention driven by the rise of the middle class as a new market for jewelry.

The article below covers archaeological finds from Kiev just prior to the Mongol conquest and gives insight into how developed the art of jewelry production was in Kiev at the time. The archaeological digs were concentrated around several locations in Kiev, including that of the Church of the Tithes (Десятинная церковь / Desjatinnaja tserkov’), more formally known as the Church of the Dormition of the Virgin, the first stone church in Kiev, built 989-996 by Byzantine and Russian artisans. The church received its nickname because Grand Prince Vladimir, who had it built, was said to have set aside a tithe of 1/10 his great wealth to finance the cathedral. In 1240, when Kiev was sacked by the armies of the Mongol Batu Khan, a number of citizens took refuge inside the cathedral, hoping to escape capture or death. Unfortunately, the cathedral caught fire and collapsed, killing all inside. A new Church of the Tithes was built in the same area of Kiev in 1828-1842, but was razed by the Soviets in 1935. Archaeological excavations of the original church, however, found many items in the cathedral crypt, taken there by the Kievans who sought refuge, and giving us a glimpse into life in the city at that time.

This article in particular discusses Kievan-type or “imitation” casting molds, used to mass produce kolts, beads, etc. which previously were formed and soldered together one at a time. I had encountered the term “imitation molds” elsewhere, but this was the first time I saw the term explained to this degree. It also touches on the curious question of why so many molds, but so few cast items by comparison, have been found in Rus’ archeology.

Kievan Jewelers On The Eve of the Mongol Conquest

A translation of Корзухина, Г. Ф. “Киевские Ювелиры Накануне Монгольского Завоевания.” Советская Археология, 14 (1950), с. 217–244. / Korzukhina, G.F. “Kievskie Juveliry Nakanune Mongol’skogo Zavoevanija.” Sovetskaja Arkheologija, 14 (1950), pp. 217-244.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.academia.edu/30309560]

Grand princely Kiev, like no other medieval Russian city, is famous for its monuments of art. Its numerous and varied workshops, located near the Church of the Tithes and in several other regions of the city, attest to the existence in Kiev of a wide range of arts from the production of building materials to delicate works of gold and silver. Over the course of two centuries, Kiev was the artistic center from whence flowed to all ends of Rus’ at first finished works, and later, as small independent city-states arose with their own artistic workshops, the best techniques and artistic forms were borrowed.

Each new period in the evolution of the Kievan state was accompanied by a change in the character of formal dress of the nobility, known to us based on numerous troves. Every change in dress was closely associated with Kiev, which served as trendsetter for all of medieval Rus’. The jewelry workshops of Kiev created completely new types of decoration, as well as producing endless variants of each type.

The list of such innovations whose emergence can certainly be tied to Kiev includes a group of monuments to be reviewed in this article: molds used to cast various types of jewelry. In particular, we are interested in molds intended for casting simple, mostly flat items — lunnitsy, round pendants, crosses, seven-bladed and other types of temple rings, buttons, beads of granulation, etc. Such molds have been found from the earliest times up through the 17th century (Yakutia, digs by A.P. Okladnikov, 1946). They are encountered anywhere that the fine casting arts developed to any extent. For this reason, they are often encountered together with clay ladles with narrow spouts and short clay handles. These molds may be made from stone or fired clay; they were sometimes made by simply pressing a finished item into clay. These kinds of molds, and the items produced using them, are widely known from all territories of Eastern Europe and beyond.

We are interested in this case in a particular group of molds distinguished from all others by the following attributes:

- carved in stone (grey limestone, black steatite, slate). These stones are small grained and dense, but soft enough to allow carving the finest details of an item;[1]Collection of the State Russian Museum in Leningrad, Inv. no. 10820; collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, v-966 and Kunderevich collection, No. 1 and 9.

- Composed of 2-3 parts. When casting one-sided, flat objects, a flat stone cap was used;

- Intended primarily for casting complex, hollow decorations. Casting these items made use of a core placed inside the mold.

The decorations which served as originals for carving designs into these molds were most complex and rich in the pre-Mongol period; these items were part of the royal/boyar dress, known to us primarily from buried troves.

It is also possible to specify a list of secondary attributes characteristic for this group of molds. They were created with extreme care. Even the external, non-functional sides are meticulously finished, and the surfaces where the molds join together are perfectly flat. To join the sides together, the sides are equipped with round, cross-cutting holes into which fastening pegs were placed.[2]More normal, simpler molds do not always have such holes; it appears that they were held together with a cord or wire. Some Kievan clay molds used for casting flail heads even have preserved marks rubbed into the non-functional sides by the wire used to hold the sides together. Molds of this group are either rectangular or trapezoidal. Round, oval, and other molds of this type are unknown.[3]An exception is a round, bronze mold for kolts from Knjazha Gora. By the nature of its material, this mold represents a rare occurrence.

This list of primary and secondary attributes includes: 1) appearance, 2) method of casting (hinged molds, slush casting); 3) type of carved item (the decorations typical for royal/boyar costume). This latter attribute is especially significant, as it is this feature which will interest us in particular.

Table 1[4]jeb: The tables at the end of the article are lists of items and location discovered. I am not including them in my translation here. The tables can be viewed in the original article, linked at the top of this page (note, this requires an Academia.edu account to access). lists all of the molds we know of from the grand princely era. Unfortunately, we were unable to study the unpublished molds from the State Historical Museum in Moscow.

The overwhelming majority of molds from the grand princely era were found in cities, large or small. That they were found in Rajki, which cannot be considered a city, is still understandable. Rajki was a pronounced artistic center, the nature of which we will not attempt to determine in this article. If we omit several unprovenanced or semi-provenanced molds from the Kharkov and Chernigov museums, then fewer than 10 examples have been found outside of artistic and urban centers, of which 2 appear to be older than the others (9th century, Grigorevka in the former Kanevskij district, Kiev region, and Emenets in the former Nevel’skij district, Vitebsk region; molds for casting imitation dirhams).[5]A mold for casting dirhams was also found in Hungary, apparently dated to the 11th century (Hampel, 1907, p. 116). It is possible that they may have existed in some as-yet-unknown settlements. In any event, it is completely obvious that molds from the grand princely era were associated with artistic centers. Several of them are dissimilar to the examples of the type we are interested in: they have randomly located small depressions for several small objects, including crosses, buttons, bells and sometimes unknown items; there are also one-sided molds, for example one of fired clay with a rough image of a cross (Sarkel and Kiev Historical Museum). Items known to have been cast in them include crosses cast in pewter with flashing of spilled metal between the arms, and reverse sides that are drawn away from the sides as in money necklaces – a sign that they were cast in one-sided molds.[6]Collection of the State Russian Museum in Leningrad, Inv. no. 10820; Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, v-966 and the Kunderevich collection, Nos. 1 and 9.

There exists a small, very special group of molds. To date, only three of them are known. They were made not of stone or clay, but of bronze or reddish copper. One bronze mold was found on Knjazha Gora (for kolts, No. 101), and a second in Sarkel (for a large bell, No. 127); a third has no provenance (for a round pendants with an eyelet, No. 142). These will be discussed further.

Several molds, based on their external appearance, are quite similar to the type under review, for example, molds for three-beaded earrings and rings from Rajki, one for pendants (?) from Vitichevo, and for buttons and small rings with cast shields and wire bands. Similar rings made of bronze or base alloys of silver are sometimes found in treasure troves, but there they represent the least valuable or exquisite jewelry. They are also often found in burials of ordinary people, or even just in the cultural layers of settlements. This can also include molds for large crosses, similar to enkolpions but without hinges.[7]B.A. Rybakov incorrectly calls these molds for enkolpions (1948, p. 262; 1946, pp. 90-91). These carved crosses lack articulated hinges. We should mention, incidentally, that B.A. Rybakov incorrectly considers one of them, found in Kiev, to be a mold used for casting enkolpions with the reverse enscribed with “Bobche pomogaj” (“Lord help me”). The images and inscriptions on this example have nothing in common with studied enkolpions. The drawing of this mold published in The History of the Culture of Medieval Rus’ (Istorii kul’tury drevnej Rusi, 1948, illustration 78, item 5) is incorrect. See instead the image published by D.I. Bagalaej (1914, Illus. 167).

Several molds, based on their external appearance, are quite similar to the type under review, for example, molds for three-beaded earrings and rings from Rajki, one for pendants (?) from Vitichevo, and for buttons and small rings with cast shields and wire bands. Similar rings made of bronze or base alloys of silver are sometimes found in treasure troves, but there they represent the least valuable or exquisite jewelry. They are also often found in burials of ordinary people, or even just in the cultural layers of settlements. This can also include molds for large crosses, similar to enkolpions but without hinges.[8]B.A. Rybakov incorrectly calls these molds for enkolpions (1948, p. 262; 1946, pp. 90-91). These carved crosses lack articulated hinges. We should mention, incidentally, that B.A. Rybakov incorrectly considers one of them, found in Kiev, to be a mold used for casting enkolpions with the reverse enscribed with “Bobche pomogaj” (“Lord help me”). The images and inscriptions on this example have nothing in common with studied enkolpions. The drawing of this mold published in The History of the Culture of Medieval Rus’ (Istorii kul’tury drevnej Rusi, 1948, illustration 78, item 5) is incorrect. See instead the image published by D.I. Bagalaej (1914, Illus. 167). As such, we cannot draw a sharp line between the examples of the types that interest us, and all remaining molds. For this reason, the division shown on table 1 between the examples of the type that interest us and all remaining molds should be seen as approximate as much as possible.[9]On table 1, the upper portion with a list of the molds which interest us is separated from the lower portion by a line. The lower part of table 1 (beneath the bold line) claims in now way to be complete, in particular for regions that are not associated with the Dnieper basin. The upper section (above the bold line) is more exhaustive. Each row of the table has molds for identical products.

In this manner, some molds for simple decorations acquired the appearance of molds for more complex items, which is apparently explained by their timing; in some cases, this similarity of form is undoubtedly tied to the specific region where they were created. Sometimes this region can be narrowed down to a specific workshop.

In order to more clearly determine the number of molds there are in the group we are interested in, and in order to determine how they were distributed according to location of discovery, we made a selection from Table 1, specifically from the upper part listing examples for casting more richly-decorated and complex items that were typical for troves:

| Group | Area | Number Found |

|---|---|---|

| Kiev | Petrovskij manor | 27 |

| Kiev | Church of the Tithes manor | 16 |

| Kiev | Trubetskoj manor | 5 |

| Kiev | Manor on Zhitomirskij Street | 1 |

| Kiev | Intersection of Vladimirskij and Irininskij Streets | 1 |

| Kiev | Florova Gora | 9 |

| Other | Halich | 2 |

| Other | Vyshgorod | 1 |

| Other | Knjazhaja Gora | 2 |

| Other | Rajki | 2 |

| Other | Grodno | 2 |

| Other | Chernigovsk Museum | 1 |

| Other | Uvek | 1 |

| Other | Mitjaevo, Moscow region | 1 |

| Other | Novgorod | 1 |

| Other | Unknown origin | 1 |

| Total | 73 |

As you can see, the overwhelming majority of such molds were found in Kiev, 59 out or 73; only 14 were found outside of Kiev, and even one of those which has no provenance may have originated in the capital. As a result, examples of this type may most assuredly be deemed to be molds of the “Kievan” type.

Within the territory of medieval Kiev (including Florova Gora), molds of the “Kievan” type were found in six locations, sometimes in large groups, and sometimes individually. The bulk of them were found in the lands of the former Petrovskij manor or the manor of the Church of the Tithes, which can only technically be said to be “separate” lands. In reality, they were a single region of medieval Kiev. Trubetskoj street lies next to it, and manor no. 4 on Zhitomirskij street lies nearby. As such, four regions of Ancient Kiev can be united into a single region. Molds found within its borders are quite similar, carefully made, and were intended for casting the most exquisite decorations of the Kievan elite.

Separately located was a fifth location, Florova Gora. Here, at different times, more than 30 molds have been discovered, but only 9 belong to the type with which we are interested. The rest were intended for casting the most simple of items – buttons, bells, pectoral crosses, plaques, and other unidentified items. Some of these molds were made from fired clay. B.A. Rybakov has asserted that the molds from Florova Gora were more aristocratic than those found in Old Kiev, based on a number of misunderstandings which would take too long to enumerate here. Basically these are related to an incorrect association of molds to various regions of Kiev, which together with a series of insufficiently substantiated suppositions leads the aforementioned author to completely incorrect conclusions (Rybakov, 1948, pp. 269-278). Based on table 1, we can see that the molds of the type which interests us were for graceful star-shaped and round kolts, which on Florova Gora appear to have been random guests amongst the greater number of rough examples for simpler items.

However, our study is interested not in questions of the social topography of Kiev, but a series of other questions tied to molds of the “Kievan” type.

A single circumstance appears as a feature of all groups of molds of the “Kievan” type. At the time when decorations were cast in the simplest of molds, known to us from thousands of examples (lunnitsy, round pendants, etc.), we as of yet do not know which items were cast in molds for more complex items which are typical of treasure troves. It is thought that do this date, we have not yet found a single silver or bronze cast kolt, star-shaped kolt, triple-bead earring, amulet, bracelet[10]B.A. Rybakov (1948, p. 265) mistakenly states that silver bracelets found in a large number of examples were cast in molds. In reality, they were all made from thin, forged sheets of metal., etc. cast in a “Kievan” type mold. In the 1890’s, when the first molds of the “Kievan” type began to appear in the collections by Kiev collectors, N.P. Kondakov noticed that they ought to have been used to cast poor imitations of items in copper and low-grade silver, but that to that time, such items had not yet been discovered in any grave sites or settlements (Kondakov, 1896, p. 143). Fifty years passed, and B.A. Rybakov, once again turning attention to Kievan molds, had to state again this fact: “Instruments for casting (that is, molds – G.K.) are present, but kolts and bracelets cast using these molds have not been discovered” (1948, p. 273). Rybakov’s attempt to explain this based on the social topography of Kiev is unconvincing for the reasons stated above.

Without undertaking to fully explain why it is still unknown what types of jewelry were cast in “Kievan” type molds, we would like to draw attention to a number of circumstances which could shed some light on this mystery.[11]It cannot be assumed that these molds were used to cast not jewelry itself, but stamps and matrices used for embossing. Items of embossed jewelry from treasure troves were soldered together from a multitude of details, each of which was created from a separate matrix. We cannot imagine a star-shaped kolt being stamped from a single sheet of metal. The bronze matrices which have been discovered for beads, kolts, etc. are all for only a single piece of these items – one side of a kolt, half of a bead, etc.

It cannot be said that the appearance of molds of the “Kievan” type (or as Rybakov felicitously calls them, “imitation molds”) was a complete surprise.[12]jeb: Imitation molds are so-called because they were used to slush-cast hollow items like kolts or beads, in imitation of similar items which were formed and soldered or fused together. It was the result of series of events. At some moment in various locations in medieval Rus’, jewelry began to be cast which was reminiscent of the best urban jewelry. Some quantity of cast jewelry exists which reproduces in simplified form and in smaller size various kinds of expensive jewelry found in troves.

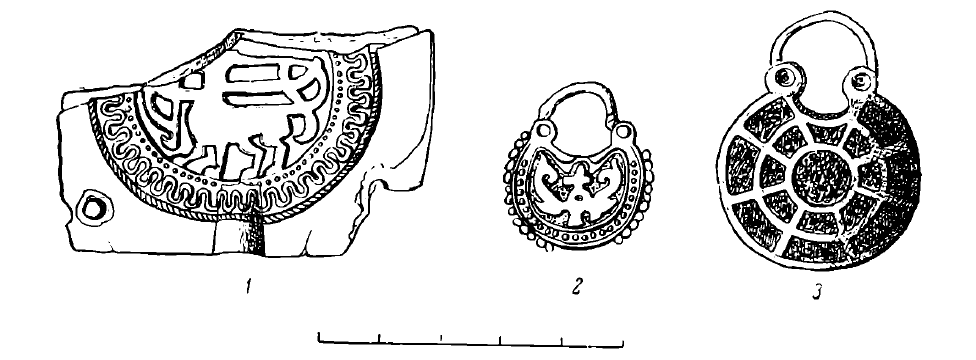

1 – star-shaped pendant from Knjazha Gora, bronze; 2 – flat kolt from Knjazha Gora, bronze; 3 – flat kolt from Poros’e, brass; 4 – mold for a flat kolt from Kiev, stone; 5 – mold for a hinged bracelet from Kiev, stone; 6 – hollow kolt from Kiev, lead; 7 – hinged bracelet from Kiev, lead.

A cast, bronze, star-shaped pendant was found on Knjazha Gora. It was small and simple in comparison to the smart, star-shaped kolts embossed in silver found in treasure troves. The rays of this semblance of a star-shaped pendant are covered in pseudo-granulation, and on the tips there are small spheres (Illustration 1, item 1).[13]Khanenko, 1902, Table XVII, item 357; Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, Inv. nos. 66107 and 13805.

A small, flat kolt and its hoop were found on Knjazha Gora, decorated with a dotted pattern (Illustration 1, item 2).[14]Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, Inv. Nos. 65790 and 30859.

In Poros’e, near Korsun, a small, flat kolt cast from brass was found, depicting two birds facing one another on either side of an upside-down lily. The hoop was cast as part of the kolt. Around the edge there is a border of cones, imitating hollow silver balls (Illustration 1, item 3).[15]Bobrinskij, 1887, p. 161, table VI, item 8; incidental find. Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, No. 66230-24730.

In 1926, S.S. Gamchenko found on the land of the former Trubetskoj manor in Kiev an interesting mold (Illustration 1, item 4; No. 57). Based on its appearance, it undoubtedly belongs to the “Kievan” type: trapezoidal with fastening holes, and meticulously worked in grey limestone. On either side it depicts kolts which are, in size and decoration (knotwork), analogous to silver embossed kolts with niello (for example, from Knjazha Gora; cf. Khanenko, 1902, Table XXVIII, item 973a). These kolts are completely similar to expensive jewelry found in troves, except in that they are flat rather than hollow.[16]Gamchenko, 1927, Illus. 16, 18; the mold is stored in the Kiev Historical Museum, Inv. No. 68271 and 1759 (Gamch. 4978).

In 1894 on Florovaja Gora in Kiev, 13 mold fragments were found together, including one for a flat kolt with a toothed edge. The decoration on the shield of this kolt was, it seems, unremarkable. (The mold survives only in fragment; No. 66).

In 1938, on the land of the former Mikhajlovskij monastery in Kiev (a dig by M.K. Karger), a fragment was found of a lead, hinged cuff-type bracelet, but significantly narrower. It was decorated with arches made up of convex points (Illustration 1, item 7). It is particularly interesting that in 1910, on the former Trubetskoj manor, during a dig by D.V. Mileev, there was found a fragment of a mold for casting a similar hinged bracelet, a poor semblance of cuffs known from treasure troves (Illustration 1, item 5; No. 60).

Molds for three-bead earrings and rings have been found in a series of cities and artistic centers (Rajki, Knjazha Gora, Novgorod, the Mitjaevskij burial mounds). Items cast in these molds would have been similar to jewelry from treasure troves, but in those troves they were the most plain jewelry, not really comparing to the other kolts, bracelets, medallion necklaces, etc. Similar cast rings are often found in commoner burials and in the cultural layers of villages in the form of individual finds (cf., for example, Khanenko, 1902, Table XXIII, items 424, 444, 1020, et.al.).

Even more similar was a find from the lands of the former Mikhajlovskij monastery in Kiev. Here, during a dig by the Institute of Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR in 1940, a cast, hollow, baglike kolt was found, decorated on both sides with knotwork ornamentation (Illustration 1, item 6). This kolt is peculiar in that, like the narrow cuff mentioned above, it was cast in lead. It is quite crude, rough and heavy, but nevertheless is very similar to kolts found in treasure troves.

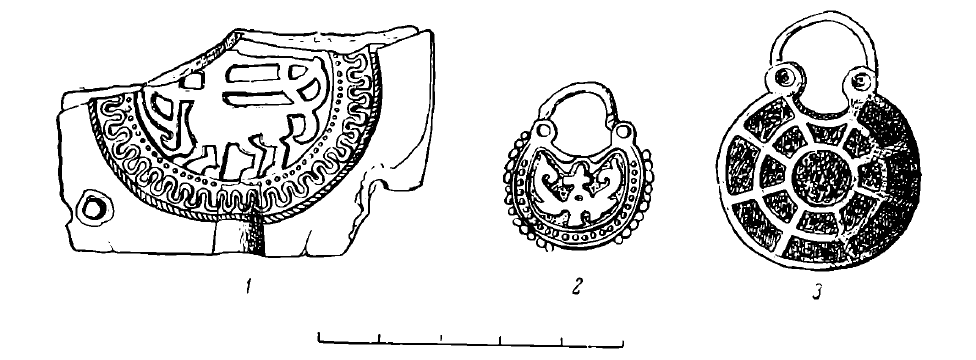

The collection of the State Russian Museum includes a lead, two-sided cross from the collection of N.P. Likhachev, which formerly served as the top of some unknown object. On the cross, there is a rough representation of the Crucifixion, orants, and saints in medallions with distorted inscriptions. All of the decorations and inscriptions are carried out in convex lines (Illustration 2, item 1).[17]Collection of the State Russian Museum, Inv. no. 13943, items a, b, v. Acquired from the Museum Fund on 18 Dec 1940. The location where it was discovered is unknown. In 1910, on the land of the Church of the Tithes manor, D.V. Mileev discovered a mold (fragment) with the image of a cross; the center of the cross appears to have depicted the Crucifixion (the hands are visible); the ends of the cross were of simple design. All of the imagery was done in carved lines, which when cast would become convex. In appearance, an item cast in this mold would have been similar to the lead cross from the Likhachev collection.

The desire to own jewelry similar to that of a noble pushed the citizens of Kiev to use cheaper metals than silver and gold. To this end, lead was used.

The discovery of lead jewelry (a narrow hinged bracelet, a kolt and a cross) lead us to a solution to the mysterious question about casting in imitation molds. However, to explore only in this direction the castings from molds of the “Kievan” type would be dangerous.

There exists a small group of molds, made from bronze and copper, intended specifically for casting in lead. To date, only three examples are known. A bronze mold could only be used to cast in metals with very low melting points like lead, certainly not silver or bronze. The first bronze mold was found on Knjazha Gora. It was used to cast a hollow kolt with decoration (knotwork) identical to that of a stone mold found by S.S. Gamchenko (Illustration 2, item 3, No. 101; see Illustration 1, item 4). The second bronze mold was found in Sarkel, and was used to cast spherical bells (no. 127; cf. Rybakov, 1940, Illus. 86-87). The third of copper was used to cast round pendants (No. 142).[18]This mold, it would seem, was not associated with the land of the central Dnieper region, but instead comes from north-western lands. It arrived to this collection from the State Academy of the History of Material Culture, which primarily obtained its materials from northern regions. All of these molds were used solely to cast items in lead. But, as we showed earlier, lead items were also cast in stone molds. For this reason, it is possible to state that lead items were cast in both metallic and stone molds, and to assert as unwarranted the theory that stone molds were used only to cast lead items.

It is hardly possible to consider that the better stone molds of the Kievan jewelers for star-shaped and round kolts depicting animals or with knotwork designs were intended for casting items in lead. Several have perceptible signs that they were used to cast in bronze.

On the former Trubetskoj estate in Kiev, I.A. Khojnovskij (1893, Table XIV, Items 144-145) discovered a stone mold which he considered to be for creating nails (No. 61). He also discovered in that location a “bronze nail” that was cast in that mold. The poor drawing provided by Khojnovskij robs us of the opportunity to definitively state that the item was not actually a nail, and that the mold was not intended to create nails. It would appear that he discovered a fragment of a mold, which had a sprue with a funnel-shaped bell at the top, and that the “nail” he discovered was metal that had hardened inside this sprue. If our observation is correct, then this would be our first evidence that imitation molds were used to cast items not only in lead, but also in bronze.

The character of the ornament carved into several molds also allows us to consider that some jewelry was cast in bronze. On lead jewelry, the ornament is made up of either convex lines or dots (for example, on a lead kolt found in 1940 – illustration 1, item 6; on a lead hinged bracelet found in 1938 – illustration 1, item 7; on a cross from the Likhachev collection – illustration 2, item 1). In molds, these lines are carved in, and the dots are drilled (for example, a mold for a hinged bracelet – illustration 1, item 5; a mold for a wide cuff from the former Petrovskij estate – illustration 4, item 2; a mold for a cross found during D.V. Mileev’s 1910 dig – illustration 2, item 2), but several molds depict animals or knotwork in the form of flat, smooth silhouettes. In the molds, these designs are sunken into the background, such that when cast, the images would become raised against a sunken ground (cf. a kolt from the crypt of the Church of the Tithes, No. 38-39; kolts from the former Trubetskoj manor, No. 57, illustration 1, item 4; two kolts from the former Petrovskij manor, Nos. 1 and 4, illustration 3, item 1; a kolt from Florova Gora, No. 65). The edges of the design are sharp and vertical. A similar character is also seen on the design on a bronze enkolpion decorated with champlevé enamel.[19]Leopardov, 1890, Table 1, item 3; Khanenko, 1899, Table XII, item 143; a series of unpublished crosses, cf.: the collection of the State Russian Museum, inventory nos. 8068 (Kiev province), 13654 (Vladimir on the Kljazma), 4138, 10404, 11776; the collection of the State Hermitage, inventory no. 828/12 (Knjazha Gora). It would appear that on these kolts, as on the enkolpion, the sunken ground around the raised design would have been filled with colored enamel. A similar bronze, hollow kolt with birds and palm leaves against a red enameled ground was found on Knjazha Gora (Illustration 3, item 2; cf. Khanenko, 1902, Table XXVIII, item 349). It is true that this item is smaller than the carving in the stone mold, but the size is not of importance, as the principal of its decoration is identical, allowing us to state that it could have been used on kolts that were cast in “Kievan” type molds.

1 – cross from the collection of N.P. Likhachev, lead; 2 – mold for a cross from Kiev, stone; 3 – mold for a lead kolt from Knjazha Gora, bronze.

In 1910, during a dig by D.V. Mileev on the Trubetskij manor, a bronze kolt with enamel was found which in terms of size was quite typical for silver kolts (0.034 m in width). The face depicted a bird in profile, a pose which was common of birds on gold jewelry, with one wing in front of its chest and the other raised high. The reverse side depicted a four-petaled rosette in a ring, surrounded by a dotted border.[20]Collection of the Hermitage, inventory no. 928/624 negat. II-3447.

Aside from kolts with birds, 2 singular bronze kolts with enamel are known, with non-pictorial decoration on both sides. One of these was found on Knjazha Gora (decorated with a pair of concentric circles and radial lines, cf. Catalog, V.V. Tarnovskij, 1898, p. 14, no. 319); the other was found in the Ekaterinoslavsk region (similar to the previous one, with red champlevé enamel; Illustration 3, item 3; cf. Petrov, 1915, Table VIII, item 8).

Aside from these, several bronze and one gold kolt with cloisonné or champlevé enamel are known. One was found in Rajki (with non-pictorial decoration),[21]Unpublished. a second was found in Galich (gold, with decoration similar to the previous), a third is located in the State Historical Museum (depicting a saint on the face and with decoration on the reverse), and the two remaining are in the State Russian Museum (paired, similar in decoration to those above, but better in quality).[22]The kolt in the State Historical Museum was published by S.G. Matveev (1928, pp. 113-117); the pair of kolts in the State Russian Museum (inv. no. 4603) was published by M.P. Botkin (M.P. Botkin Collection, 1911, illustration on p. 36).p The bronze kolts were gilded (there are traces of gold).

This group of kolts and an adjoining series of bronze enameled jewelry (crosses, enkolpiony, pins, and various other items) are descended from another series of jeweled items: non-silver, embossed, nielloed, and gold jewelry with cloisonné enamel. These kolts, cast in Kievan-type molds, imitate silver jewelry with niello. Genetically, these are two divergent trends in jewelry. However, at some time, these two trends crossed. Decoration which was typical for silver embossed jewelry (animals, knotwork) became decorated with enamel instead of niello.

1 – mold for a bronze enameled kolt from Kiev, stone; 2 – bronze enameled kolt from Knjazha Gora; 3 – bronze, gilt, enameled kolt from the Ekaterinoslavsk region.

Based on all this information, it is obvious that the current theory about the absence of items cast in imitation molds does not align with reality. Cast rings, a hinged bracelet, and both flat and hollow kolts are known. Some of these items were cast in pewter, part in bronze, and several bronze items are decorated with enamel. The quantity of these cast items, however, is relatively small compared to number of molds that have been discovered. It follows to take into consideration that during mass production, the number of items cast should have been significantly greater than the number of molds, that is, exactly the opposite of what has been seen.

One of the reasons for this small quantity of cast items could be the use of brittle material such as lead. But, this cannot completely explain this phenomenon. It is quite possible that there is a second reason related to the time when these imitation molds arose.

Typically, Kievan imitation molds date to the 12th-13th centuries. There have twice been attempts to clarify their dates. Briefly, literally in few words, A.S. Guschin touched on this question (1927, pp. 74-75), dating molds based on the items carved into them as “no later than the first half of the 12th century” (from the mid-11th to the mid-12th century). Guschin based his dating on the fact that “Kiev, as an economic center, had already stopped playing a central role by the first half of the 12th century, and after the complete defeat of Andrej Jurievich in 1169, it lost all of its wealth and completely fell into decay.” Therefore, “the heyday of mass production of silver jewelry can only be dated to the 11th century.”

B.A. Rybakov (1948, pp. 271-272, 278) dated the appearance of imitation molds to the 12th century. Based on the text preceding his final conclusion, it appears that he was leaning toward the end of the 12th century, but he is not finally specific.

In the history of medieval Russian formal metallic jewelry, it is possible to discern 3 types which successively replaced one another. Each consisted of a multitude of items that were varied in form and purpose, but stylistically unified. The first class arose in the second half of the 10th century and was still in use in the early 11th century. It consisted of embossed silver jewelry with floral, non-pictorial decoration. The kind of jewelry worn in the mid-11th century, that is, during the Jaroslav era, is not yet clear to us, but in the late 11th century, there arose a new class which was quite different from that of the 10th century. It consisted exclusively of rich gold jewelry with very complex filigree, precious stones, pearls, and small enameled insets. In the early 12th century, enamel gradually replaced almost all other types of decoration and became the lone form of decorative finery. In the mid-12th century, this gold jewelry gave way to a third stylistically-unified form of jewelry that was characteristic of the period of feudal fragmentation. Jewelry of this third type are typologically quite similar to the gold jewelry, but they were made of silver, and were decorated with niello instead of enamel. This third class of jewelry lived from the mid-12th century right up to the Mongol invasion. The character of jewelry changed somewhat over those 80-90 years. Work on the dating of treasure troves, which served as the theme of my dissertation, has provided the ability to track these changes and to determine which items belong to the early, middle or late sections of this time. It would take too long to enumerate all of the arguments that allow us to date items to this or that time. We provide here only the main features of one of these groups of jewelry, belonging to the end of this period, that is, to the first half of the 13th century.

In the 13th century, three-bead earrings were often made with different beads: the central bead differed in size and decoration from those on either side. Often the central bead (and sometimes all three) were oval.

13th century kolts were quite small, much smaller than before. Sometimes they were bag-shaped and stretched outward at the bottom. The borders around kolts in the 13th century are exceptionally varied. Along with traditional round spheres imitating strings of pearls, there appeared varied combinations of small spheres, thick ribbed wire, thin flattened wire, etc. Alongside earlier designs (gryphons, birds), non-pictorial decoration appears in the 13th century – knotwork and other decorative compositions.

Star-shaped kolts in the late 12th century became quite large. Their conical rays became pear-shaped. The small spheres on the ends of their rays and pyramids of round granules were replaced by large hollow spheres or cones. Under the arch, there appeared an additional ray or process in the form of a truncated cone.

When jewelry depicted a human face (saints, sirens, etc.), the faces were shown in profile, rather than straight-on as before.

If one looks closely at the items carved into casting molds, one immediately notices they contain features characteristic only of later jewelry, from the first half of the 13th century. The kolts are small, with shields that are often covered with non-pictorial decoration. Their borders are quite varied, with wire loops, spheres, wire, etc. Earrings had various different beads, oval beads, or even had many beads (see nos. 11 and 51). Star-shaped kolts had pear-shaped rays. Faces are shown in profile.

All of these data lead us to date these imitation molds quite narrowly to the early 13th century (before 1240).

To this list of signs we can add one more that supports this dating. The use of champlevé enamel on bronze arose in Kievan Rus’ in the 13th century,[23]A bit earlier, around the mid-12th century, items with mixed cloisonné-champlevé enamel on bronze appeared. and fell into decline in the 14th century. This is confirmed by a study of bronze enkolpions, among which enkolpions with champlevé appeared very late in the pre-Mongol period and fell into decline in the post-Mongol period.

The insignificant number of items of jewelry cast in imitation molds that have been found in modern times may partly reveal on the late arrival of this casting method. It appears that casting jewelry in Kievan-type molds began not long before the Mongol invasion, but the idea of casting items that resembled embossed jewelry was in the hands of skilled jewelers of the larger artistic centers, in particular those of Kiev, where the overwhelming majority of imitation-style molds have been discovered.

As has already been said, the casting molds found in Kiev originate primarily from two regions – Florova Gora, and the former Petrovskij manor and the adjacent land of the Church of the Tithes.

31 molds have been found on Florova Gora. These were found in various locations, in groups and singularly. Based on archival data, we managed to clarify information about these molds. The notes from V.V. Kvojko’s collection, written on 28 August 1894 and sent to the Archeological Commission with an offer of sale, indicated: “Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, stone molds found together in June 1894 after torrential rains in the city of Kiev on Florova Gora [in total, 13 molds – G.K.]. Nos. 2, 16, 17, 19, 23, stone and clay molds found on the same hill in various locations. No. 10, a stone mold, acquired in Kiev from a vendor, location of discovery unknown.”[24]Archive of the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences, I, 1894, No. 122, p. 7. There is a photograph taken by the Archeological Commission. It shows 14 stone and clay molds (therefore, the molds in the photo are from multiple groups in the description). Unfortunately, no numbers are visible in the photo, so it is not possible to determine which of them were found together or from which locations on Florova Gora. All 19 molds from the Khvojko collection were bought by the Archeological Commission for the Hermitage, and were subsequently transferred to the State Russian Museum.[25]Hermitage, Inv. nos. 95/48-54; State Russian Museum, Inv. nos. 11421-11424, 11426, 11429-11440, 11672. Unfortunately, the original numbers from the Khvojko collection are not preserved in either the Hermitage’s inventory, nor on the molds themselves; as a result, the 13 molds found together after a rainfall and presumably belonging to the same workshop cannot be discerned from the remaining set of Florova Gora molds. We were able, however, to find a photograph in the photo-archives of the Institute of the History of Material Culture. The photo was taken in 1894 by V.V. Khvojko in Kiev and sent to the Archeological Commission. In the photo, amongst an array of items (arrow heads, fragments of clay toys, etc.) there are 13 stone molds, apparently the same 13 which were found together following a downpour.[26]Photoarchive of the Institute of the History of Material Culture, F-114.7. On our table #1, these 13 items are listed under numbers 65-67, 69-72, 74-75, 77, 85-86, and 89. These molds are for 3 kolts, a three-bead earring, a large medallion, 2 rings (one with the seal of the Rurikovichi) and a series of small, plain jewelry; there are also 2 capstones for one-sided molds: flat stone tiles with fastening holes and a small notch on top used as a casting funnel.

In this manner, the instrumentation of jewelers’ workshops on Florova Gora has been recovered. The array of molds shows that, along an array of elaborate, hollow cast items and jewelry such as those found in treasure troves, they were also used to create small, simple jewelry – pendants, crosses, buttons, etc. There can be no question about the special aristocratic nature of jewelry coming out of this workshop, in comparison to the workshops on the former Petrovskij manor.

Molds from the former Petrovskij manor originate from digs by V.V. Khvojko (1907-1908) and the Institute of Archeology of the Ukranian SSR Institute of Sciences (1936). From the lands of the former manor of the Church of the Tithes, aside from a few individual finds, the majority of molds were found in 1939 by M.K. Karger (1941) in the cathedral crypt, where they ended up in connection with the destruction of the church in 1240.

Unfortunately, the exact location where the molds found by V.V. Khvojko, which constitute a significant portion of Kievan finds, were discovered is unknown. Based on evidence published by Khvojko (1913) about his dig, it is impossible to determine whether the molds he found originate from one or several artists’ workshops. However, based on notes in his diaries, which are preserved in Kiev in private hands, it appears that the molds were discovered within the area of a single jeweler’s workshop, but the exact location of this find cannot be determined.

A comparison of the molds from the cathedral crypt and from Khvojko’s dig revealed that one mold from the crypt (no. 46) and one from Khvojko’s dig (No. 10) are actually parts of a single mold for a three-beaded earring (Illustration 4, item 1). Therefore, if it were possible to determine where on the former Petrovskij manor Khvojko made his discovery, it might be possible to know the location of the workshop of the jeweler who took refuge in 1240 in the Church of the Tithes and who perished under her collapsed vaults. It would appear that we have several data toward the resolution of this question.

1 – parts of a mold for earrings from Kiev: a – from the crypt of the Church of the Tithes, b – from the former Petrovskij manor; 2 – parts of a mold for a cuff bracelet from Kiev: a – found in 1908, b – found in 1936.

In 1936, during the work of the Kievan archeological expedition by the Ukranian SSR Academy of Sciences on the former Petrovskij manor, on “plot S, dig A,” that is, on the border of the between the former Petrovskij and Sljusarevskij manors (50 meters or so northwest of the Church of the Tithes), 4 molds were discovered: one for some kind of conical pendant (No. 23), the second and third for a three-beaded earring (Illustration 5, item 1; Nos. 13 and 14), and a fourth for a bracelet (Illustration 4, item 2b; No. 16). This last mold appears to be part of a mold for a cuff bracelet found by V.V. Khvojko (Illustration 4, item 2a; No. 15). This makes it possible to locate the jeweler’s workshop which was uncovered by Khvojko, and where the jeweler who took refuge in the Church of the Tithes would have lived and worked, the same jeweler who preserved along with himself an example of the latest advances in casting technology. His workshop was located quite close to the cathedral, just a few dozen to the northwest.

Of particular interest is that we are able to determine not only the location where this jeweler lived and worked, and not only the time and location of his death, but even his name! On one of the molds originating from his workshop (the mold for a three-beaded earring found in 1936, No. 13), several letters have been scratched in two rows, spelling out: “МАКОСИМОВ” (“Makosimov”, Illustration 5, item 2), that is, “Maksim’s”. It appears that the medieval term for a mold was masculine. For the study of medieval Russian art, which was extremely poor at preserving the names of its master artisans, this appearance of a new name tied to even brief biological data can certainly be considered a happy and interesting find. It should be considered that the name “Makosimov” belonged to the master jeweler, and not to the person who carved the mold. The genitive case form of the inscription emphasizes the fact of its use and ownership, rather than its creation.[27]jeb: The author implies that if the inscription was emphasizing who created the mold, it would have been written in instrumental case — that is, the inscription should be read as “Maksim’s mold” rather than “a mold made by Maksim”.

1 – Mold for a three-beaded earring from Kiev; 2 – Inscription on the mold.

In this way, we can determine the existence of two significant jeweler workshops in 13th century Kiev – one on Florova Gora and one on the former Petrovskij manor. A few molds were discovered outside of these complexes, but there are no direct data to link them to either of these workshops. It would appear that these belonged to other workshops. One of these may have been located on the former Trubetskoj manor, south of the Church of the Tithes. Here there was found a fragment of a mold, as mentioned above: a sprue and the bronze cast in that sprue which I.A. Khojnovskij referred to as a bronze nail. Their discovery together leads us to the conclusion that the workshop itself was located somewhere nearby.

4 more molds are associated with the former Trubetskoj manor: one was for a kolt (No. 57), a second was for a cuff bracelet (No. 60), and the remaining two for a three-beaded earring (Nos. 58 and 59).

It is not yet known whether casting molds were carved by the jewelers themselves, or if they were created by specialist stone carvers. Works of art discovered in the Kievan region over recent years speak to the great versatility of Kievan master artisans. Various forms of art united in one and the same sets of hands. As a result, we assume that jewelers would carve their own molds. However, whereas normal casting molds were unceasingly varied in appearance, molds of the “Kievan” type are all exceptionally similar to one another. It would appear that this is due to the narrow region in which they were made and the shortness of the period of time that they were in use, which again supports our belief that these imitation-style molds appeared on the eve of the Mongol invasion.

The molds from Galich (Nos. 96 and 97) differ from those from Kiev. They are simpler and coarser, and the items carved into them are of a different style. It is apparent that in Galich, there existed a completely independent production of jewelry of this type.

The molds from Grodno (Nos. 112, 113) are quite poorly made, but they seem to be related to the famous Nakiev raid (the small size of the starred kolt, the small, narrow rays, and the smaller than usual number of rays).

Molds found in Novgorod, Rajki and other locations are simpler than those found in Kiev.

On the other hand, a mold for a star-shaped kolt found in Uvek on the Volga River (No. 129) does not differ from the Kievan molds in either its appearance, decoration, or the impeccable carving technique. It would appear to have been carved in Kiev and sent to Uvek in the years following the Mongol invasion.

On Knjazha Gora, of course, there existed an independent and also highly developed production of jewelry.

What can explain the development of imitation-style molds? What did their appearance mean for the history of medieval Russian art? Can the start of mass production of cheaper items of jewelry be seen as a sign of the art’s progress, or of its decline?

Its appearance can be seen as a sign of both the progress and downfall of Kievan art. If one compares cast jewelry of the pre-Mongol years to the more exquisite items that were worn by the upper classes of Kiev in the 11th-12th centuries, then the production of the former must be seen as a sign of a regression of the high art of jewelry making in the central Dnieper region. These cast items were crude and heavy, and were only slightly reminiscent of the more expensive jewelry of the upper class. But, it is not really possible to compare these two groups of items, as they were intended for completely different social categories: items chased from precious metals were for the upper classes, and those cast in bronze and lead were for everyday citizens. It is not coincidental that jewelry cast in imitation-style molds are never found in treasure troves of gold and silver items.

In order to determine whether there was or was not a regression in the arts of jewelry making in 13th century Kiev, by comparison to the 12th century, it is necessary to compare jewelry of the upper classes from the 12th century to those of the 13th century, or to compare jewelry for everyday citizens from both time periods. With such comparisons, it becomes perfectly obvious that jewelry worn by the upper class in the 13th century became much worse in quality, while that worn by everyday citizens became significantly more varied as it was filled by a number of different types of jewelry which were previously worn only by members of the more wealthy classes of society. The relocation of centers of active political life to the north and northwest during the period of feudal fragmentation deprived the central Dnieper region of its former power, when it was the most important political and cultural center of Kievan Rus’. Life in the cities of the central Dnieper region gradually tapered off. Thanks to the stability of medieval artistic traditions which were preserved by the central Dnieper’s jewelers, applied art was affected by these changes a bit later than were other areas of the city’s culture. In the second half of the 12th century, jewelry for the upper class continued to live a full-blooded, artistic life, and only began to show signs of decline in the late 12th and especially in the 13th centuries. In this time, nothing new was created. Jewelers lived off the achievements of better days, combining elements of decoration which were created by their predecessors. Frequently, a conscious archaization of jewelry can be noticed. Along with this, the quantity of jewelry produced becomes smaller, and the technique of production and the quality of metal used becomes cheaper.

At the same time, the selection for everyday citizens was replenished in the 13th century by an entire array of new jewelry which conveyed in simplified form the jewelry of the upper class. The penetration of these simpler, less expensive forms of princely-boyar jewelry into wider layers of society can be seen even earlier. For example, in the first half of the 11th century, cast bronze jewelry using more simplistic technique appears imitating signs of the formed, silver, granulated jewelry which appeared amongst the upper class in the 10th century. This included large and medium-sized cast bronze lunnitsy, round semi-spherical pendants with granulation, etc. These items were cast in molds created simply by pressing expensive prepared items into clay.

Casting jewelry in stone molds in the 13th century was qualitatively different from the clay molds used by earlier artisans. As B.A. Rybakov correctly stated (1948, p. 271), “only the presence of a wide, reliable circle of customers or of the free market could have made possible the appearance of such expensive and time-consuming devices as these casting molds.” As a result, the appearance of imitation stone molds must be seen as a consequence of the large and widely diversified craft, rather than as a sign of the decline of art as a whole. In the late 12th and 13th centuries, all medieval Russian cities were developing their own local artistic forms. These artistic forms in the new political centers were, of course, less aristocratic than in former Kiev. At the same time, Kievan art also became less aristocratic and joined the crafts of the other principalities in forming a new culture characteristic for this period of feudal fragmentation.

Imitation-style molds are interesting as well in that the items which were cast in them reflected the tastes of their immediate users, the artisans. Perfectly aware of their upper-class customers, but at the same time fully connected with the urban masses, Kiev’s jewelers for one last, short time became trendsetters, creators of particular jewelry. The Mongol invasion interrupted the further development of art in the central Dnieper region. In the post-Mongol period, the development of art followed completely different paths.

Literature

- Artamonov, M.I. “Srednevekovye poselenija na nizhnem Donu.” Izvestija Gosudarstvennoj akademii istorii material’noj kul’tury. 1935 (131).

- Artsikhovskij, A.V. Kurgany vjatichej. Moscow, 1930.

- Bagalej, D.I. Russkaja istorija. Vol. I. Moscow, 1914.

- Bobrinskij, A.A. Kurgany i sluchajnye arkheologicheskie nakhodki bliz m. Smely. Vol. I. St. Petersburg, 1887.

- Gamchenko, S.S. “Rozkopi 1926 r. v Kyivi.” Korotke zvydomlenija za 1926 r. Kiev, 1927.

- Guschin, A.S. “K voprosu o slavjanskom zemledel’cheskom iskusstve.” Sbornik “Izobrazitel’noe iskusstvo.” Gosudarstvennyj institut istorii iskusstv. Leningrad, 1927.

- —. Pamjatniki zhudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi X-XIII vv. Leningrad, 1936.

- Dovzhenok, V.I. “Ogljad arkheologychnogo vivchenija drevn’ogo Vishgoroda za 1934-1937 rr.” Arkheologyja. 1950 (3), Table VI, item 10.

- Istorija kul’tury drevnej Rusi. Domongol’skij period. Vol. I. Material’naja kul’tura. Moscow-Leningrad, 1948.

- Karger, M.K. “Tajnik pod razvalinami Desjatinnoj tserkvi v Kieve.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury. 1941 (X).

- Katalog vystavki XI arkheologicheskogo s’ezda v Kieve. Kiev, 1899.

- Katalog ukrainskikh drevnostej kollektsii V.V. Tarnovskogo. Kiev, 1898.

- Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. St. Petersburg, 1896.

- Leopardov, N.A. Sbornik snimkov s predmetov drevnosti, nakhodjaschikhsja v g. Kieve v chastnykh rukakh. Issue 1. Kiev, 1890.

- Matveev, S.G. “Mednyj kolt Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja.” Trudy sektsii arkheologii Rossijskoj assotsiatsii nauchno-issledovatel’skikh institutov obschestvennykh nauk. Vol. II. Moscow, 1928.

- Molchanovskij, F.N. “Obrabotka metalla na Ukraine v XII-XIII vv. po materialam Rajkovetskogo gorodischa.” Problemy istorii dokapitalisticheskogo obschestva. 1934 (5).

- Petrov, N.I. Al’bom dostoprimechatel’nostej tserkovno-arkheologicheskogo muzeja pri Kievskoj dukhovnoj akademii. 1915 (IV-V).

- —. Ukazatel’ Tserkovno-arkheologicheskogo muzeja pri Kievskoj dukhovnoj akademii. Kiev, 1897.

- Rybakov, B.A. “Znaki sobstvennosti v knjazheskokm khozjajstve Kievskoj Rusi X-XII vv.” Sovetskaja arkheologija. 1940 (IV).

- —. “Sbyt produktsii russkikh remeslennikov v X-XIII vv.” Uchenye zapiski Moskovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. 1946 (93).

- —. Remeslo drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1948.

- Sobranie M.P. Botkina. St. Petersburg, 1911.

- Spitsyn, A.A. “Novye priobretenija Saratovskogo muzeja.” Izvestija arkheologicheskoj komissii. 1914 (53).

- Tarnovskij, V.V. Katalog ukrainskikh drevnostej kollektsii V.V. Tarnovskogo. Kiev, 1899.

- Khanenko, B.I. and V.I. Drevnostej Pridneprov’ja. 1902 (V).

- —. Drevnosti russkie, kresty i obrazki. 1899 (1).

- Khvojko, V.V. Drevnie obitateli srednego Pridneprov’ja i ikh kul’tura v doistorichskie vremena. Kiev, 1913.

- Khojnovskij, I.A. Raskopki velikoknjazheskogo dvora drevnego grada Kieva. Kiev, 1893.

- Durczewski, Z. Stary zamek w Grodnie w swietle wikopalisk dokonanych w latach 1937-1938. Grodno, 1939.

- Hampel. Ujabb tanulm nyok a honfoglalasi kor emlekeiröl. Budapest, 1907.

- Hołubowicz, W. “Znaki rodowe i inne na przedmiotach z wykopalisk w Grodnye.” Slavica Antiqua. Vol. 1. Poznan’, 1948.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Collection of the State Russian Museum in Leningrad, Inv. no. 10820; collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, v-966 and Kunderevich collection, No. 1 and 9. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | More normal, simpler molds do not always have such holes; it appears that they were held together with a cord or wire. Some Kievan clay molds used for casting flail heads even have preserved marks rubbed into the non-functional sides by the wire used to hold the sides together. |

| ↟3 | An exception is a round, bronze mold for kolts from Knjazha Gora. By the nature of its material, this mold represents a rare occurrence. |

| ↟4 | jeb: The tables at the end of the article are lists of items and location discovered. I am not including them in my translation here. The tables can be viewed in the original article, linked at the top of this page (note, this requires an Academia.edu account to access). |

| ↟5 | A mold for casting dirhams was also found in Hungary, apparently dated to the 11th century (Hampel, 1907, p. 116). |

| ↟6 | Collection of the State Russian Museum in Leningrad, Inv. no. 10820; Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, v-966 and the Kunderevich collection, Nos. 1 and 9. |

| ↟7 | B.A. Rybakov incorrectly calls these molds for enkolpions (1948, p. 262; 1946, pp. 90-91). These carved crosses lack articulated hinges. We should mention, incidentally, that B.A. Rybakov incorrectly considers one of them, found in Kiev, to be a mold used for casting enkolpions with the reverse enscribed with “Bobche pomogaj” (“Lord help me”). The images and inscriptions on this example have nothing in common with studied enkolpions. The drawing of this mold published in The History of the Culture of Medieval Rus’ (Istorii kul’tury drevnej Rusi, 1948, illustration 78, item 5) is incorrect. See instead the image published by D.I. Bagalaej (1914, Illus. 167). |

| ↟8 | B.A. Rybakov incorrectly calls these molds for enkolpions (1948, p. 262; 1946, pp. 90-91). These carved crosses lack articulated hinges. We should mention, incidentally, that B.A. Rybakov incorrectly considers one of them, found in Kiev, to be a mold used for casting enkolpions with the reverse enscribed with “Bobche pomogaj” (“Lord help me”). The images and inscriptions on this example have nothing in common with studied enkolpions. The drawing of this mold published in The History of the Culture of Medieval Rus’ (Istorii kul’tury drevnej Rusi, 1948, illustration 78, item 5) is incorrect. See instead the image published by D.I. Bagalaej (1914, Illus. 167). |

| ↟9 | On table 1, the upper portion with a list of the molds which interest us is separated from the lower portion by a line. The lower part of table 1 (beneath the bold line) claims in now way to be complete, in particular for regions that are not associated with the Dnieper basin. The upper section (above the bold line) is more exhaustive. Each row of the table has molds for identical products. |

| ↟10 | B.A. Rybakov (1948, p. 265) mistakenly states that silver bracelets found in a large number of examples were cast in molds. In reality, they were all made from thin, forged sheets of metal. |

| ↟11 | It cannot be assumed that these molds were used to cast not jewelry itself, but stamps and matrices used for embossing. Items of embossed jewelry from treasure troves were soldered together from a multitude of details, each of which was created from a separate matrix. We cannot imagine a star-shaped kolt being stamped from a single sheet of metal. The bronze matrices which have been discovered for beads, kolts, etc. are all for only a single piece of these items – one side of a kolt, half of a bead, etc. |

| ↟12 | jeb: Imitation molds are so-called because they were used to slush-cast hollow items like kolts or beads, in imitation of similar items which were formed and soldered or fused together. |

| ↟13 | Khanenko, 1902, Table XVII, item 357; Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, Inv. nos. 66107 and 13805. |

| ↟14 | Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, Inv. Nos. 65790 and 30859. |

| ↟15 | Bobrinskij, 1887, p. 161, table VI, item 8; incidental find. Collection of the Kiev Historical Museum, No. 66230-24730. |

| ↟16 | Gamchenko, 1927, Illus. 16, 18; the mold is stored in the Kiev Historical Museum, Inv. No. 68271 and 1759 (Gamch. 4978). |

| ↟17 | Collection of the State Russian Museum, Inv. no. 13943, items a, b, v. Acquired from the Museum Fund on 18 Dec 1940. The location where it was discovered is unknown. |

| ↟18 | This mold, it would seem, was not associated with the land of the central Dnieper region, but instead comes from north-western lands. It arrived to this collection from the State Academy of the History of Material Culture, which primarily obtained its materials from northern regions. |

| ↟19 | Leopardov, 1890, Table 1, item 3; Khanenko, 1899, Table XII, item 143; a series of unpublished crosses, cf.: the collection of the State Russian Museum, inventory nos. 8068 (Kiev province), 13654 (Vladimir on the Kljazma), 4138, 10404, 11776; the collection of the State Hermitage, inventory no. 828/12 (Knjazha Gora). |

| ↟20 | Collection of the Hermitage, inventory no. 928/624 negat. II-3447. |

| ↟21 | Unpublished. |

| ↟22 | The kolt in the State Historical Museum was published by S.G. Matveev (1928, pp. 113-117); the pair of kolts in the State Russian Museum (inv. no. 4603) was published by M.P. Botkin (M.P. Botkin Collection, 1911, illustration on p. 36).p |

| ↟23 | A bit earlier, around the mid-12th century, items with mixed cloisonné-champlevé enamel on bronze appeared. |

| ↟24 | Archive of the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences, I, 1894, No. 122, p. 7. |

| ↟25 | Hermitage, Inv. nos. 95/48-54; State Russian Museum, Inv. nos. 11421-11424, 11426, 11429-11440, 11672. |

| ↟26 | Photoarchive of the Institute of the History of Material Culture, F-114.7. |

| ↟27 | jeb: The author implies that if the inscription was emphasizing who created the mold, it would have been written in instrumental case — that is, the inscription should be read as “Maksim’s mold” rather than “a mold made by Maksim”. |