I recently finished reading and translating a chapter from Jewelry of Medieval Novgorod by M.V. Sedova, an overview of jewelry found in archeological digs. This chapter describes rings [perstni] that have been uncovered in Novgorod. Unfortunately some of the photos are rather dark and murky, but the chapter still gives a great overview of the wide array of ring styles that have been discovered from medieval Rus’. Novgorod’s use of wooden streets has left behind a very detailed time-map allowing archeologists to very accurately map finds down to the decade in some cases, and it’s interesting to see how styles changed over time. Illustration 80 (which is from the book’s Conclusion chapter) in particular contains a number of rings with settings that I wish I could find color photos of. And, the footnotes have me eyeing more sources to read in the future!

Jewelry Of Medieval Novgorod (10th-15th centuries)

A translation of Седова, М.В. «Перстни.» Ювелирные изделия древнего Новгорода (Х-XV вв.). Москва: Издательство «Наука», 1981, с. 121-144. / Sedova, M.V. “Perstni.” Juvelirnye izdelija drevnego Novgoroda (X-XV vv.). Moscow: Publishing House “Science,” 1981, pp. 121-144.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

http://www.archaeology.ru/Download/Sedova/Sedova_1981_Iuvelirnye.pdf. ]

Table of Contents

- Introduction (pp. 3-9)

- Head Jewelry (pp. 9-22)

- Torcs (pp. 22-23)

- Pendants (pp. 23-48)

- Items of the Christian Cult (pp. 49-73)

- Pins (pp. 73-83)

- Brooches (pp. 83-93)

- Bracelets (pp. 93-121)

- Rings (pp. 121-144) [this post]

- Belt Decorations (pp. 144-153)

- Various Clothing Items (pp. 153-159)

- Other Products (pp. 159-180)

- Conclusion (pp. 180-194)

Rings

Along with bracelets, rings were the most common form of jewelry. In Novgorod digs from 1951-1974, 290 rings were found, including fragments which are difficult to assign to any given type. Judging by materials from excavations of burial sites, in the lands of northwestern and northeastern Rus’, rings were primarily worn by women, although they were also worn by men and children. They were worn on both the left and right hands, sometimes on both hands at the same time. The number of rings varied from 1-2 to 4-5, and sometimes reached as high as 10 on both hands. They are sometimes found worn on the toes. This was characteristic of the Finno-Ugric peoples.[1]Nedoshivina, N.G. “Perstni.” Ocherki po istorii russkoj derevni X-XIII vv. Trudy GIM, issue. 43. Moscow, 1967, pp. 253-254.

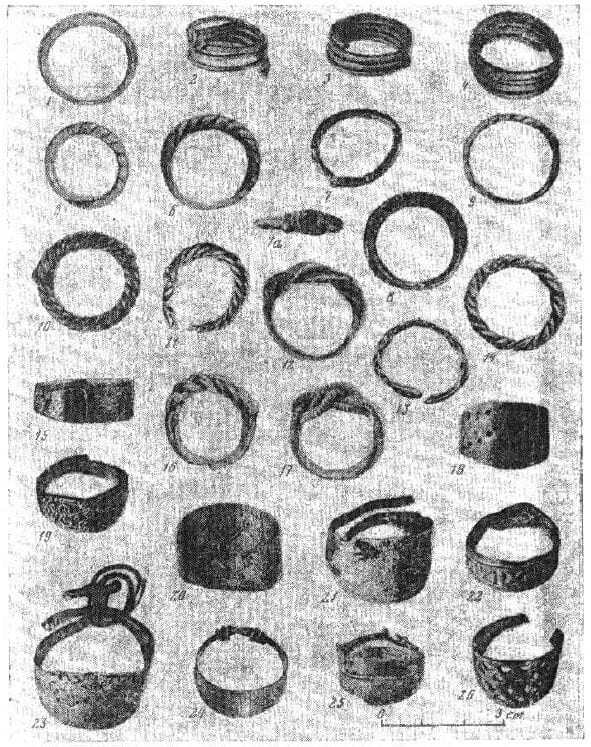

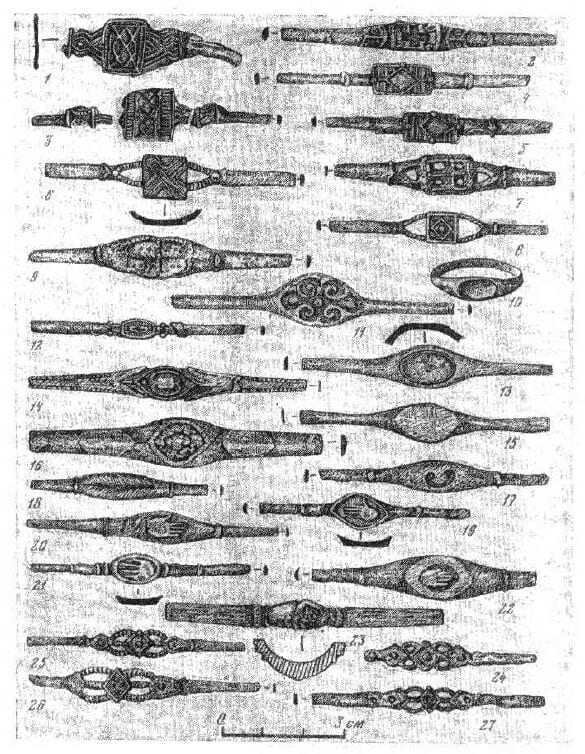

(1) 25-28-26; (2) 24-28-3; (3) 23-27-52; (4) 21/20-25-41; (5) 18-218; (6) 15-23-847; (7) 18-19-451; (8) 23/22-25-882; (9) Lyud., eastern trench; (10) 17-21-285; (11) Il13/12-22-203; (12) 18-22-269; (13) 19/18-24-1856; (14) Il18-19-120; (15) 22-28-785; (16) 18-15-539; (17) K18-67; (18) 14-16-458; (19) 22-23-965; (20) 28-32-189; (21) 25-30-813; (22) 10-12-679; (23) 24-22-606; (24) 22-24-375; (25) 24-27-355; (26) 18/17-17-1098

Wire Rings

Illustration 45, item 1. Closed, round-wire rings. These are the simplest form of wire ring. They were found in layers from the early 11th century thrIllustration 45, item 1. Closed, round-wire rings. These are the simplest form of wire ring. They were found in layers from the early 11th century through the 1170s (25-28-26[2]jeb: See the introduction for a description of how to decipher these attribution numbers. — illus. 45:1; 22-24-315[3]jeb: If no illustration:item-number reference is given, such as with this example, then the referenced item is not pictured in any of the illustrations.; 20-20-445; 17-20-860). The middle (face) section of these rings is somewhat thickened, while the inner faces of the wire is tapered. Microstructural analysis of one such ring showed that closed rings were cast without any subsequent working.[4]Ryndina, N.V. “Tekhnologia proizvodstva Novgorodskikh juvelirov X-XV vv.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii SSSR. 117 (1963), p. 240.[5]jeb: See my translation of this article into English here: https://rezansky.com/jewelry-production-technology-in-10th-15th-century-novgorod These rings were made from a multi-component alloy (group V).[6]jeb: See the introduction for further details about the varous groups of alloys used to create items of jewelry found in the Novgorod digs.

Round-wire rings with overlapping ends. These are a variant of the closed rings. Their middle section is likewise thickened; the ends are tapered, and overlap one another somewhat. These rings were distributed in layers from the late 11th-late 13th centuries (21-25-305; 20-17-1707; 20-25-16; 18-22-223; 18-14-1740; 18/17-20-1643; 17-13-680; 15-22-814; 15-20-1207; 15/14-21-1118; Tr8-96; 14/13-21-1334). They were first cast as a straight billed, which was then bent around a finger mandrel. They were made from multi-component alloys (group V) until the 13th century, when they were made from a lead/tin pewter (group VIII). Rings of this type were very common among Slavic antiquities.

Illustration 45, items 5-6. Ribbed rings. These are a variation of round-wire rings. Their thickened, outer surface has been marked with oblique grooves, imitating that they have been twisted. On the palm side, their smooth overlapping or joined ends are tapered. Similar rings were one of the most common form of jewelry amongst all of the Slavic tribes.[7]Nedoshivina, Perstni, p. 264. It would seem that they may be considered an ethnically defining characteristic of the Slavs. In Novgorod, 17 such rings have been found in layers from the 1090s-1390s (21-23-1620; 20-25-41; 20-24-53; 20-25-184; 20/19-21-414; Il14-24-250; 19/18-28/1330; 18-218 — Illus. 45:5; 18/17-27-1398; 18/17-20-1008; 17-19-944; 15-21-2158; 15-23-847 — Illus. 45:6; 14-14-1673; K20-49; Slav12-38; 6-8-902). They were cast using a composite, rigid mold. The grooves on the outer surface were created using a gouge.[8]Ryndina, Technologia proizvodstva…, p. 240. Ribbed rings were only made from tin-lead and tin bronzes.

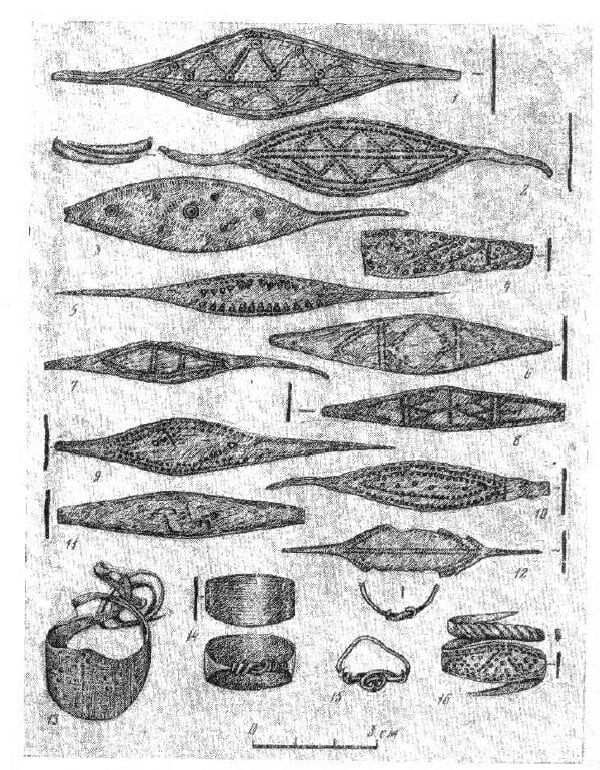

Illustration 46, item 15. Tied-off round-wire ring. This ring was found in a layer from the 1050s (Buja16-17-17 — Illus. 46:15). Its shield consists of a wire which has been wrapped into a spiral and then tied off on either side. Similar rings have been found in Vladimir and Uglich burial sites. A.A. Spitsyn dates those rings to the 11th century.[9]Izvestija Arkheologicheskoj komissii, 15 (1905), p. 320.

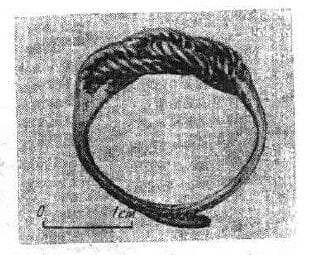

Illustration 45, items 2-4; Illustration 47, item 2. Spiral rings. These are made from wire which has been bent spirally into multiple rows. They were made by wrapping pre-annealed wire around a round mandrel.[10]Ryndina, Tekhnologija proizvodstva…, p. 240. Spiral rings have been found in layers from the first quarter of the 11th century through the mid-13th century, but their appearance changed over the course of that time. The oldest ring, found in a layer from the 1020s-1050s, is made from round wire which has been spirally wrapped into four tiers and then twisted into a spiral at the ends (24-28-3 — Illus. 45:2). Similar rings are known among Finno-Ugric and Baltic antiquities from the 10th-11th centuries.[11]Latvijus PSR arheologija. Riga, 1974, table 52, item 10; Kivikoski, E. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands. Helsinki, 1973, Illus. 753. In Novgorod burial sites, several such rings have been found, in particular once with an 11th century coin. A.A. Spitsyn dates these rings to the 11th century. Four rings were found in a layer from the mid-11th century (23-27-52 — Illus. 45:3), from the turn of the 11th-12th centuries (21/20-25-41 — Illus. 45:4), and from the first half of the 13th century (15-17-1823; 15/14-21-1121b — Illus. 47:2). The rings from the 11th-early 12th century were made from a rectangular cross-section wire that had been tightly coiled; the rings from the 13th century were made from round-wire and their spirals were quite loose. This type of ring in quite widespread use. They are associated with antiquities of the Finno-Ugric and Baltic tribes from the Baltic region to the Kama region.[12]Selirand, J. Eestlaste matmiskombed varafeodaalsete suhete tarkamise perioodil. Tallin, 1974, table XL, item 8; Katalog der Ausstellung zum X. Archaeologischen kongress in Riga. Riga, 1896, Table 21, items 3-5, 7-8; Shnore, E.D. Asotskoe gorodische. Riga, 1961, Table VI, items 42, 49, 56; Lietuviu liaudies menas. Vilnius, 1958, No. 523; Smirnov, A.P. “Ocherki drevnej i crednevekovoj istorii narodov Srednego Povolzh’ja i Prikam’ja.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii SSSR. 28 (1952), p. 124, Table XXX, items 6, 9.

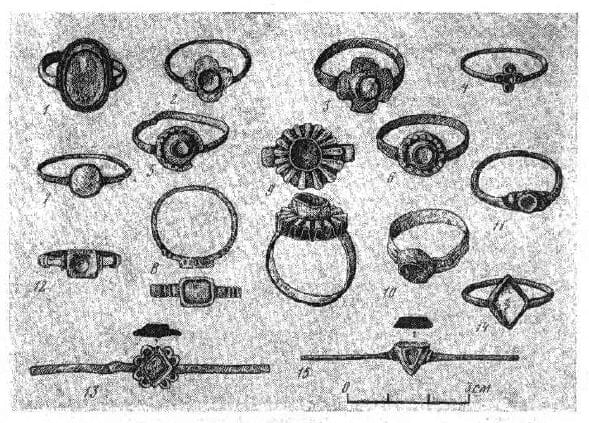

(1) 28-32-189; (2) 25-30-813; (3) 24-26-1566; (4) 15-16-1902; (5) 14-15-1931; (6) 14/13-20-1128b; (7) 13/12-19-1142b; (8) 8/7-13-709; (9) Tikhv13-16-1; (10) Mikh19-29-59; (11) 11/9-15-22; (12) 24-27-355; (13) 24-22-606; (14) 22-24-375; (15) Buja16-17-17; (16) K26-28

Twisted Rings

Twisted [vitye] rings represent a significant portion of all rings discovered. They may be categorized based on the number of wires from which they are twisted, into double, triple, quadruple (2×2); based on the design of their ends, into looped, cut-off, closed, and so forth.

Illustration 47, item 3. A ring made from two wires, each folded over into thirds and twisted, but not intertwined. The ends of the wires have been soldered into a flat shield (25-28-372 — Illus. 47:3). This is the oldest of the twisted rings, dating to the 11th century.

Illustration 45, items 12, 14. Doubled over and twisted wire rings [dvojnye so skanoj perevit’ju]. One such ring was found in a later from the 1050s-1060s (Il18-29-120 — Illus. 45:14). It was made from billon which had been forged into wire which was of consistent thickness across its entire length. The other doubled and twisted ring, which is thicker on the outer side and narrow on the palm side, was found in a layer from the 1160s-1170s (18-22-269 — Illus. 45:12). Analogous rings are quite common among antiquities of the Baltic region, Finland, and Scandinavia, as well as in materials from Novgorod burial sites. A.A. Spitsyn dates these to the 12th-13th centuries.[13]Nedoshivina, Perstni, p. 263, illus. 33, item 8; Selirand, Eestlaste matmiskombed…, table XL, item 2, p. 355; Kivikoski, Die Eisenzeit Finnland, Illus. 1094; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 20 (1896), Table III, item 10.

Illustration 45, items 10, 13. Rings made from wire which has been folded into thirds and twisted [trojnye vitye perstni]. These appear in several variations. Two rings with closed ends appear to have been made from three-wire bracelets with chopped off ends (Il16/15-25-57; 17-21-285 — Illus. 45:10), and date to the 1170s-1230s. Five of these rings with looped ends (similar to bracelets) were distributed throughout layers from the 1130s to teh end of the 13th century (19/18-24-1856 — Illus. 45:13; Buja13-12-19; 16-14-672; Il11/10-20-320; 12/11-13-954). They were all made from multicomponent alloys (group V).

A four-strand (2×2) twisted ring. Only one such ring has been found to date, in a layer from the late 12th century (16-21-1191). The round wire from which it was twisted was made of tin (group IX).

Illustration 45, items 7, 8. Pseudo-twisted rings. In appearance, these rings resemble twisted rings, but they were cast in a mold which was created by pressing a twisted ring into clay. Four pseudo-twisted rings with closed or overlapping ends have been found in various layers: the early 11th century (25-27-1017); the early 12th century (20/19-24-323); the late 13th century (11-19-750); and the early 15th century (4-10-1375). Therefore, they cannot be seen as belonging to any particular chronological period. They differ only in the alloys from which they were made: those from the 11th-early 12th centuries were made of brass (group IV), while those from the 13th and 15th centuries were made of a tin/lead pewter (group IX).

A pseudo-twisted ring mimicking a ring made from two wires which have been folded into thirds and twisted but not intertwined (of the type seen in Illustration 47:3 above) was found in a layer from the 1050s-1070s (23/22-25-882 — Illus. 45:8).

A pseudo-twisted ring with an oval shield on the end was found in a layer from the 1160s-1170s (18-19-451 — Illus. 45:7). It was cast from a tin/lead bronze alloy (group II). In appearance, it resembles a 3-rod, wrapped bracelet with an oval shield on one end which dates to the late 11th century (Illus. 36, items 2a, b).[14]jeb: See the images and description of this item in my translation of the chapter on bracelets, https://rezansky.com/jewelry-of-medieval-novgorod-10th-15th-centuries-bracelets/

(1) 22-17-1753; (2) 15/14-21-1121b; (3) 25-28-372; (4) 15-16-1904; (5) 11-17-1123; (6) 14-11-1732; (7) 11-14-1645; (8) 21-25-391; (9) Ljud12-9; (10) 21/20-23-315; (11) 27-31-78; (12) 20-28-746; (13) 24-25-1652; (14) 22-26-292; (15) 15-14-984; (16) Ljud15-3; (17) 8-10-1819; (18)13/12-12-1794; (19) 8-10-1823; (20) 12-19-136; (21) 7/6-13-1334; (22) 5-8-1535; (23) 4-4-1657; (24) K18-14; (25) 3-5-1265; (26) 3-11-dig I; (27) 2-9-98

Plaited Rings

Rings of this type were woven from several wires, and the technology of this weaving is similar to that used to create bracelets of the corresponding type. Plaited rings are divided into two types.

Illustration 45, items 16-17; Illustration 48. The first type consists of rings which have a plaited center section, and smooth joined or overlapping ends. In the Novgorod collection, there are seven such rings, found in layers from the mid-12th to the mid-14th centuries. The rings were initially woven from four or six wires, the ends of which were then forged into a single, smooth unit. Four wires[15]jeb: Plaited 2×2? were used to create pewter rings from the mid-12th (18-15-539 — Illus. 45:16) and early 14th centuries (Il8/7-15/24), as well as a silver ring from the mid-14th century (K18-67 — Illus. 45:17). Six wires (sometimes first twisted in pairs) were used to create a bronze ring from the 1150s-1170s (Il13-23-127), a billon ring from the 1220s-1230s (15-21-1226), a gold ring from the early 14th century (10-12-909 — Illus. 48), and a billon ring from the 1320s-1340s (Mikh10-18-60).

Illustration 45, item 11; Illustration 49, item 4. The second variation consists of rings which are woven for their entire length from seven thin wires, with the central section slightly thicker, and the ends tapered. Four such rings have been found in layers from the 1170s-1280s (Il13/12-22-203 — Illus. 45:11; 15-16-1900; 14-22-1344; 14/13-15-1800 — Illus. 49:4). These rings were made from a lead/tin bronze (group IV) and pewter (group X).

Plate Rings

Plate rings, as with bracelets, were made from plate metal of varying thickness. They are in the shape of an elongated rectangle, and are divided into various types based on the shape of their ends.

Illustration 45, items 5, 18-22; Illustration 46, items 1-4, 6-10. Rings with wide centers and open ends. These are the most common type. Their ends gradually narrow from the wider, central part. This form was used over the course of many centuries and has even survived to modern day, therefore we are able to date these rings based on their ornamentation, technology of production, and source material. The oldest ring of this type found in Novgorod is from layers dating to the mid-10th century (28-32-189 — Illus. 45:20, 46:1). It was forged and has stamped decoration in the form of two zigzags with punched circles between the sharp corners. Similar in form and decoration is a ring with overlapping ends and a stamped pattern in the form of two zigzag lines, found in a layer from the early 11th century (25-30-813 — Illus. 45:21, 46:2). A forged ring decorated with large and small punched circles (24-26-1566 — Illus. 46:3) dates to the first quarter of the 11th century. All of these rings were made from a multi-component alloy (group V). Similar rings are found in Gnezdo, Jaroslav and Ladoga-region burial sites from the second half of the 10th century, but they are also known from material found in later Novgorod and Kostroma burial sites from the 12th-early 13th centuries.[16]Nedoshivina, Perstni, p. 257, Illus. 32, item 3.

A billon ring from the 1070s-1090s (22-23-965 — Illus. 45:19), cast in a one-sided stone mold, stands apart for the originality of its decoration. It’s design is composed of foliate curls.

Of the 19 remaining unclosed rings with wide centers distributed in layers from the late 11th-late 12th centuries, 11 are unornamented, 8 are covered in patterns (21/20-26-123; 20-25-dig VB; 20/19-22-355; Mikh19-29-59 — Illus. 46:10; 17-14-684; 17/16-20-860; 16-12-679; 15-16-1902 — Illus. 46:4; Tikhv13-16-1 — Illus. 46:9; 14-15-949; 14-16-458 — Illus. 45:18; 14-15-1931; Tikhv11-15-22; 14/13-20-1128b — Illus. 46:6; 13-16-1532; 13/12-19-1142b — Illus. 46:7; 12-19-1359; 11-19-843; 8/7-13-70). These decorations are primarily geometric, stamped, and in the form of “wolves teeth”[17]jeb: A stamp in the form of a triangle containing 3 raised dots., diamonds, triangles, and double lines. With the exception of the cast ring from the late 11th century mentioned above (22-23-965 — Illus. 45:19), the remainder were all forged.[18]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236. The 11th century items were made from a multi-component alloy (group V), the 12th-13th century items are of tin-bronze (group III) and tin-lead bronze (group II), pure copper (group I), or brass (group IV).[19]Konovalov, A.A. Tsvetnye metally…, pp. 143, 145.

Illustration 45, items 24-25; Illustration 46, items 12, 14.[20]jeb: The original references illus. 46:24, which doesn’t exist. It appears this is a typo and should have referenced illus. 46:14. Rings with wide centers and tied-off ends. These rings are set apart from teh previous set in that, their ends are wrapped around the shank and tied off on either side. Three rings have been around in layers from the 11th century. These were all forged, 2 made of brass (24-27-355 — Illus. 45:25, 46:12; Tr20-64) and one of silver (22-24-375 — Illus. 45:24, 46:14). On one of these rings (Illus. 45:24) there is a pattern created using a double toothed wheel; the others are all smooth. Tied-off rings are known from a broad territory across northeastern Europe — in Sweden and Finland to the west, from sites in the Baltic region, from burial sites in the Leningrad, Pskov, Novgorod, Kalinin, Jaroslav, and Vladimir regions, and from burial grounds in Ljadinskij and Maksimov to the east. Although these rings appear in the West in the late 10th century, in our lands they primarily date to the 11th century.[21]Arbman, H. Birka. Vol. II. Upsala, 1940, Table III, items 8-10; Tallgren, A.M. Zur Archaeologie Eestis. Vol. II. Dorpat, 1925, p. 103, illus. 136; Nedoshivina, Perstni, pp. 269-270, illus. 31, items 2, 4; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 10 (1893), table II, item 11; 25 (1901), table XXV, item 7.

Illustration 45, item 23; Illustration 46, item 13. A wide-centered, “whiskered” ring. This item was found in a layer from the 1020s-1050s (24-22-606 — Illus. 45:23, 46:13). The ring is made of brass. Its long ends, the “whiskers,” instead of being wrapped around the shank of the ring, have been tied into a careless knot. The shield is decorated with a stamped pattern in the form of a cross with three small dots at each end. “Whiskered” rings serve as a defining trait of the Finno-Ugric tribes. They are found in antiquities from Finland, the Baltic region, the northwestern regions of Rus’, and between the Volga and Oka rivers, dating from the late 10th-early 13th centuries.[22]Nedoshivina, Perstni, pp. 257-258, Illus. 31, item 5.

Illustration 46, item 16. “Whiskered” ring with ribbed ends. This appears to be a variation on the “whiskered” [usatyj] ring. It dates to the mid 13th century (K26-26 — Illus. 46:16), and is made of bronze. Its shield is decorated with a stamped zigzag pattern, with triangles punched in each of the turns. Similar rings have been found in Gotland, Finland, the Baltic region, and in the northwestern regions of Novgorod lands, dating to the 11th-13th centuries.[23]Stenberger, M. Die Schatzfunde Gotlands der WIkingerzeit. Vol. II. Lund, 1947, Table 39, item 2; Selitrand, Eestlaste mamiskombed…, pp. 352-353; Shnore, Asotkoe gorodische, Table VI, items 40, 47; Nedoshivina, Perstni, Illus. 31, items 5-6; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 20 (1896), Table XIII, items 21-22; 29 (1903), Table XXIII, items 38-39.

Illustration 45, item 15; Illustration 47, item 12. “Straight” rings [Prjamye perstni]. These rings have a consistent width and unclosed ends. One smooth ring cast in bronze was found in a layer from the last quarter of the 11th century (22-28-785 — Illus. 45:15); another was found in a layer from the mid-12th century (19-16-663). A third is decorated with a series of convex dots down the middle, surrounded by a pair of “flagella” (oblique hatch marks) on either side (20-28-746 — Illus. 47:12). It would appear that this was previously a fragment of an oval-ended bracelet (cf. Illustration 42:18) dating to the first third of the 12th century.[24]jeb: See the images and description of this item in my translation of the chapter on bracelets, https://rezansky.com/jewelry-of-medieval-novgorod-10th-15th-centuries-bracelets/ The ring was found in a layer from the first quarter of the 11th century.

Illustration 45, item 26. A latticework [reshetchatyj] ring. This ring was found in a layer from the 1160s-1170s (18/17-17-1098 — Illus. 45:26). It is a double-zigzag filigree copper ring, cast in a one-sided stone mold. Latticework rings are an ethnic marker of the Vjatichi tribe of Slavs. The typology and dating of these rings was well studied by A.V. Artsikhovskij and T.V. Ravdina.[25]Artsikhovskij, A.V. Kurgany vjatichej. Moscow, 1930, p. 73; Ravdina, T.V. Khronologija «vjaticheskikh» drevnostej. Avtoref. kand. dis. Moscow, 1975, p. 11. The discovery of this latticework ring in Novgorod attests to the direct contact between the Vjatichi and this great cultural center of medieval Rus’.

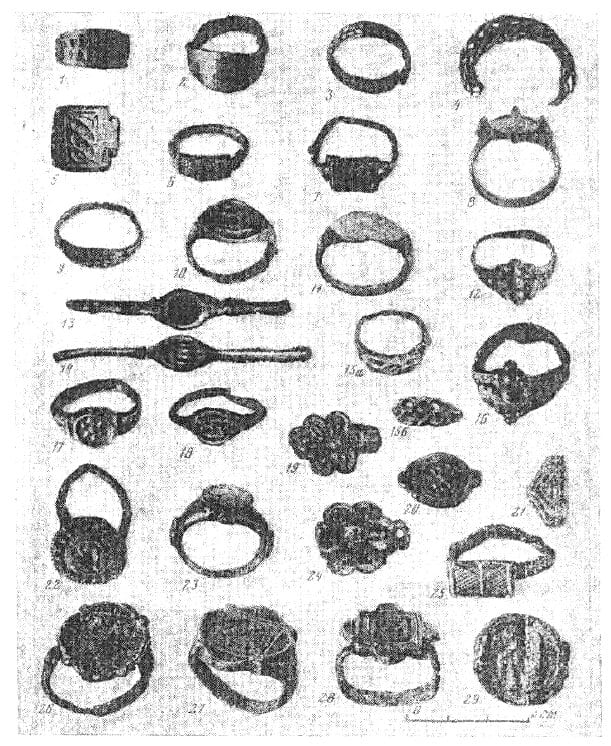

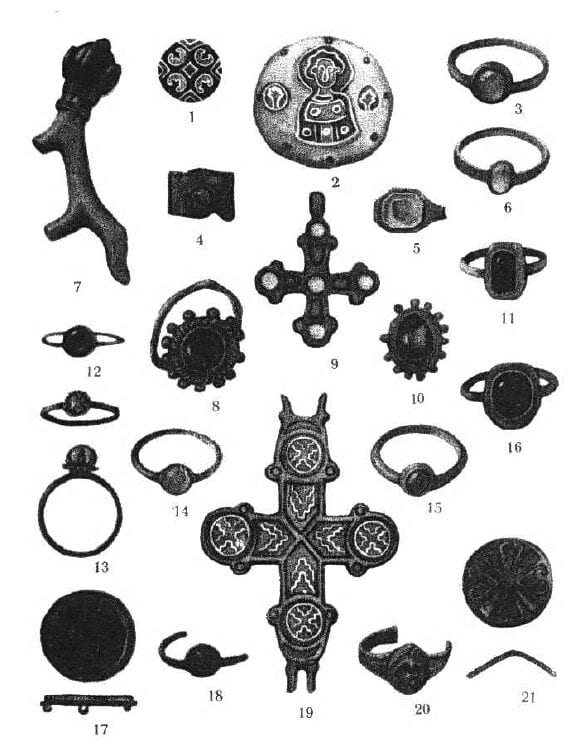

(1) 23-27-1232; (2) 12/11-7-669; (3) Il18-28-95; (4) 14/13-15-1800; (5) 18-20-40; (6) 9/8-14-1163a; (7) 13-21-767; (8) K21-29; (9) Il-12-12-14; (10) 10-14-1515; (11) K16-69; (12) Il16-25-20; (13, 18) 7/6-13-1334; (14) 7/6-13-1329; (15a, b) K25-76; (16) 20-25-787; (17) 10/9-11-1103; (19) 4-12-123; (20) Tr8-83; (21) 12-19-136; (22) 18-19-1104; (23) Tikhv15-23-51; (24) Tikhv4-14-53; (25) 7/6-15-778; (26) Tikhv13-17-49; (27) 14-22-624; (28) 2-7-1376; (29) without provenance.

Illustration 47, items 1-2, 4-7; Illustration 49, items 1-2. Rings with wide centers and closed ends. These rings are wider on the face and gradually taper on the palm side. In all, 10 rings of this type have been found, in layers from the mid-11th to the early-14th centuries. All of them were made of pewter. The oldest ring was cast in a mold created by pressing an original ring into clay, and is decorated with a relief pattern of “wolves teeth”, two rows of triangles with three dots inside each (23-27-1232 — Illus. 49:1). Another ring, dating to the 1170s-1190s, is decorated along the contours of the middle section with granulated lines with a convex “braid” between them (22-17-1753 — Illus. 47:1). A ring from the first third of the 12th century is decorated with a rhombus with a dot in the middle (15-16-1904 — Illus. 47:4). Three rings from the 13th century are smooth and unornamented (15-15-493; 12-12-1770; 12/11-7-669 — Illus. 49:2). Two rings from the turn of the 13th-14th centuries are ornamented. On one, there is a raised pattern in the form of two teardrops with the wider end pointing toward the center, where there are two circles (11-17-1123 — Illus. 47:5). On the other, the pattern is of two concentric diamonds with a circle in the middle and triplets of the same circles on either sides of the diamonds (11-14-1645 — Illus. 47:7). On the edges of these bands, the soldering seams are visible. N.V. Ryndina notes that “this is a characteristic sign that they were cast in a two-part mold with inserted rods. Each side of the mold was carved with a semicircular canal, the width of which corresponded to the inner diameter of the ring. In the wall of the canal there was a transverse recess for the band’s rim, which connected to the sprue. Having joined the sides of the mold and having placed a cylindrical rod into the canal, they would cast the ring. Once the mold was taken apart, the ring was removed from the rod.”[26]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236.

Two cast rings from the 1230s-1260s are distinguished by their famous originality (14-11-1732 — Illus. 47:6; Lyud12-9 — Illus. 47:9). Their ornamentation consists of 3 or 4 cells containing oblique crosses. Rings with similar three- or five-part ornamentation are considered a characteristic decoration of the Vjatichi tribes of the third quarter of the 12th century.[27]Ravdina, T.V. “Drevnerusskie litye perstni s geometrichestkim ornamentom.” Slavjane i Rus’. Moscow, 1968, pp. 133-138. On several of these, signs of red enamel have been found. All of the Vjatichi rings come from rural burial mounds – none have been found in settlements. The Novgorod rings are first such discovery in the cultural layer of a city. However, their ornament is unique and not fully analogous to Osko-Moscow River rings. It is possible that they were created based on a Vyatichi pattern, but by Novgorod artisans, who somewhat redesigned the traditional pattern.

Illustration 47, items 8, 10-11, 13-16, 18, 24-26; Illustration 49, item 3. Narrow plate rings. These rings are of consistent width (3-7 mm) along their entire length. They may be divided into two variants: closed-ended, and with overlapping ends. The latter were found in layers from the late 10th-late 13th centuries. The oldest ring from the 970s-990s is decorated with transverse relief dashes (27-31-78 — Illus. 47:11). Of six rings from the 11th century, two were undecorated (25/24-25-1911; 24-29-2064), one was decorated with four raised lateral lines (24-25-1652 — Illus. 47:13), one is covered with eye-shaped[28]jeb: This is a diamond shape with a dot in the middle. stamp marks (24-52-393), and three have a design in the form of a braided cord (Ljud15-3 — Illus. 47:16; Il18-28-95 — Illus. 49:3; 22-26-292 — Illus. 47:14). This last ring was bent from plate which had been cast in a mold created by pressing a finished ring into clay.[29]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236. Rings with braid designs were widely worn among the Finnish tribes of the Volga and Kama regions, and are not characteristic of Slavic antiquties.[30]Gorjunova, E.I. “Merjanskij mogil’nik na Rybinskom more.” Kratkie coobschenija Instituta istorii materialnoj kultury Akademii nauk SSSR. 54 (1954), Illus. 71, item 11. These Novgorod rings were created, it appears, from strips that were cast using clay molds created from finished items.[31]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236, Illus. 20, item 5.

No narrow plate rings with overlapping ends have been found in layers from the 12th century. Rings from the 13th century were decorated with vine patterns (15-14-984 — Illus. 47:15) and a twisted spiral pattern with granulation (13/12-12-1794 — Illus. 47:18), but three were completely undecorated (14-19-326; 14-16-1811; 14-19-2086).

There are several examples of narrow plate rings with closed ends: a pewter ring from the turn of the 11th-12th centuries decorated with a pair of lines created by a toothed stamp (21-25-391 — Illus. 47:8); a bronze ring from the early 12th century decorated with an eye-shaped punch (21/20-23-315 — Illus. 47:10); and a bronze undecorated ring from the 1230s-1260s (14/13-16-1583).

There is a group of rings from the mid 14th-15th centuries, particularly compact chronologically-speaking, which are narrow plate with closed ends. All five rings are cast in bronze, with extended flanges and a protruding middle section covered in vertical dashes (K18-14 — Illus. 47:24; 6-8-1543; 3-11-dig I — Illus. 47:26; 3-5-1265 — Illus. 47:25; Got5-48). Similar rings have been found in 14th-15th century layers in Staritsa.[32]Voronin, N.N. “Otchet o raskopkakh v Staritse Kalininskoj obl.” Arkhiv Instituta arkheologii Akademii nauk SSSR. R-1, d. 358, p. 108.

Shield Rings

Rings of this type typically have a narrow-plate band and a sharply expanding middle section in the form of a circle, oval, square or diamond. Longitudinally, the shield is in the same plane as the band.

(1) 18-27-1364; (2) 14-22-1424; (3) 13/12-16-1526; (4) 14-15-1920; (5) 10/9-11-1103; (6) 13-20-1351; (7) 9-9-1673; (8) 5-13-133; (9) 18-19-1104; (10) 11/10-15-1250; (11) Il12-21-275; (12) Tikhv13-17-49; (13) below level 28-33-42; (14) Il18-29-38; (15) 13-16-1534; (16) 2-7-1376; (17) 15-18-1601; (18) 25-27-1019 [jeb: Incorrectly labeled as “#16”]; (19) Mikh10-18-93; (20) 7/6-15-778

Illustration 50, items 14, 18. The oldest examples in the Novgorod collection are two rings from the 11th century. They are made of bronze, with shields that project up over the band. One has a shield in the form of a eight-petaled rosette (25-27-1019 — Illus. 50:18[33]jeb: Note that this item is incorrectly labeled in illustration 50. There are two rings marked #16, to the left and right of rings #15 and #17. The ring on the left is the actual #16. The ring on the right should be marked #18.); the other has a shield in the form of a hemisphere surrounded by large spheres of granulation (Il18-29-38 — Illus. 50:14).

Illustration 49, items 12, 16. Two rings cast in pewter have shields decorated with large spheres of pseudo-granulation (20-25-787 — Illus. 49:16; Il16-25-20 — Illus. 49:12). These rings date to the first half of the 12th century.

Illustration 49, item 5; Illustration 51, items 1, 3. Rings with transverse rectangular shields. Three rings with shields decorated with knotwork were found in layers from the second half of the 12th century to the 1230s (18-20-40 — Illus. 49:5; 16-18-904 — Illus. 51:1; 16/15-17-1876 — Illus. 51:3). These rings were cast in pewter (group VIII) in composite stone molds with inserted rods.[34]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236. Two molds for casting similar rings were found in Serensk.[35]Nikol’skaja, T.N. “Kuznetsy zhelezu, medi i serebru ot vjatich.” Slavjane i Rus’. Moscow, 1968, illus. 3, item 2. Rings with identically decorated shields were found in burial mounds near Moscow[36]Latysheva, G.P. “Raskopki kurganov u st. Matveevskaja v 1953 g.” Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki Moskvy i Podmoskov’ja. Moscow, 1954, illus. 6, item 2. and in Staraja Rjazan’.[37]Mongajt, A.L. “Staraja Rjazan’.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR. 49 (1955), illus. 137, item 4.

Illustration 49, items 13, 17-18, 20; Illustration 50, items 1-8, 10. Rings with round shields. These rings came into use in Novgorod in the second half of the 12th century existed through the early 14th century. A ring was found in a layer from the 1160s-1170s with a round shield decorated with lines of pseudo-granulation (18-27-1364 — Illustration 50:1). There are additional rounded widenings on either side of the shield. A mold for casting similar rings was found in Kiev.[38]Karger, M.K. Drevnij Kiev. Vol. 1. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958, table XIV.

A ring from the 1230s-1260s, cast in pewter, is decorated in the center with a quatrefoil surrounded by a radial design (14-15-1920 — Illus. 50:4). A second ring from the same period is undecorated, but has additional widenings on either side of the shield (14-22-1424 — Illus. 50:2). It was cast in tin bronze (group III).

A pewter cast ring from the 1260s-1280s is decorated with a pair of touching arcs enclosed in a rim (13-20-1351 — Illus. 50:6).

A ring from the 1260s-1280s cast in tin (group IX) has a shield decorated with a five-part uneven rosette, with plant fronds on either side (13/12-16-1526 — Illus. 50:3).

Two rings dating from the late 13th-early 14th centuries have smooth shields encircled by “braid” and filigree widenings abutting the shield (K23-27; K20-58).

Two rings cast in pewter are decorated with a four-part rosette with a dot in the middle. The bands are split and covered in notches where they touch the shield. One such ring was found in a layer from the late 13th century (13-20-624), the other in a layer from the 1340s-1360s (9-9-1673 — Illus. 50:7).

A ring cast in tin dating to the late 13th century to the early 15th century has a shield with two semi-circular curls and two triangles; on either side of the shield, there are raised tripartite widenings (11/10-15-1250 — Illus. 50:10).

The shield on a ring cast in pewter (group VIII) from the first half of the 14th century is decorated with 7 raised hemispheres, and with pyramids made up of three hemispheres on either side of the shield (10/9-11-1103 — Illus. 50:5).

A ring from the 14th century (Tr8-83 — Illus. 49:20), cast in bronze, depicts an octofoil surrounded by a radial design, and is reminiscent of the pattern of another ring from the mid-13th century described above (Illus. 50:4).

A ring from the early 15th century is decorated with a pair of concentric circles (5-13-133 — Illus 50:8).

A special group is comprised of 10 unclosed rings with round shields, on which is depicted an ancient solar symbol. All of these rings, cast in copper in a single one-sided mold, were found together in the complex of a jeweler’s workshop from the 1380s-1390s (7/6-13-1334 — Illus. 49:13, 18). Five of these have been bent into a circle, while the others are still flat blanks with signs of casting flash. The shields of the finished rings have signs of enamel.[39]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 241. An identical ring was found at the Mikhajlovskij dig in a layer dating from 1319-1323 (Mikh11-20-39). Analogous rings are known from the materials found in Novgorod burial mounds from the 13th-14th cneturies[40]Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 20 (1896), Table XIII, item 31. and from the antiquities of the Kama region.[41]Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 26 (1902), Table XV, item 11.

(1) 16-18-904; (2) 13/12-19-1123; (3) 16/15-17-1876; (4) 9/8-14-234; (5) 9/8-14-1163a; (6) 13-21-767; (7) 8/7-15-1325; (8) Tikhv11-15-22 [jeb: Incorrectly labeled as #6]; (9) 14-21-759; (10) 16-20-298; (11) 9-14-2118; (12) 11/10-15-1499; (13) Tikhv8-14-60; (14) 14-20-2120; (15) 3-8-1379; (16) 4-5-1602; (17) 11/10-18-1426; (18) 8-11-456; (19) Mikh7-15-40; (20) 11/10-16-1259; (21) Mikh8-16-75; (22) 8-3-1755; (23) Got1/15-3; (24) 10/9-17-1361; (25) 9/8-6-662; (26) Tikhv8-14-73; (27)Slav15-14

Illustration 49, items 8-11, 14; Illustration 50, item 17; Illustration 51, items 9-22. Rings with oval shields. These were found in layers from the very end of the 12th century through the mid-15th century. Several of these are undecorated (16-20-298; Tikhv8-14-60; K16-69 — Illus. 49:11; Mikh7-15-57; 3-8-1379; 9-4-937), but the majority have designs on their shields. For example, a cast, bronze ring from the 1220s-1230s is decorated with five rows of large pseudo-granulation (15-18-1601 — Illus. 50:17). A ring from the 1230s-1260s is decorated with a cross and with dots in each of the four quadrants (14-21-759 — Illus. 51:9). It was cast in an alloy of tin and lead in a composite mold with an inserted rod.[42]Ryndina, Technologia proizvodstva…, pp. 239-240, Illus. 20, item 9. A cast bronze ring from the same time period is decorated with two semi-ovals with a rectangle between them (14-20-2120 — Illus. 51:14).

A large number of rings with oval shields depict human hands. 12 such rings were found in layers from the late 12th – late 14th centuries (Il12-21-14 — Illus. 49:9; 11-18-1379; 11/10-16-1259 — Illus. 51:20; 10-14-1515 — Illus. 49:10; 10-15-dig IIE; Mikh8-16-75 — Illus. 51:21; Mikh7-15-40 — Illus. 51:19; 8-3-1755 — Illus: 51:22; 8/7-13-277; 7-4-673; 7/6-13-1329 — Illus. 49:14). This last ring was found in the same complex as the rings with solar symbols mentioned above. It was manufactured in the same workshop, cast as a straight blank in copper, and still has casting flash on its band. The remaining rings were all cast in pewter in a two-sided mold with an inserted rod. Only one (11-18-1379) was cast from a wax model.[43]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 239, Illus. 21, item 1. Rings depicting human hands are well known among Western European antiquities. They are occasionally also found in medieval Russian cities: for example, in Goroditsa on Volga, a similar ring was found in a layer from the 13th-14th centuries.[44]Medvedev, A.F. “Novye materialy po istorii Goroditsa na Volge.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta arkheologii Akademii nauk SSSR. 113 (1968), Illus. 7, 9.

From the turn of the 13th-14th centuries comes a ring cast in billon, with a shield depicting a cross surrounded by oval notches (11/10-15-1499 — Illus. 51:12). A bronze ring with a decoration in the form of a semi-oval dates from the same time (11/10-14-1426 — Illus. 51:17). Two bronze rings from the early 14th century have cast “thorns” around the edges of an oval shield with a transverse protrusion between them (10-12-895; K21-29 — Illus. 49:8). A similar ring was found in layers from the 10th-13th centuries in Polotsk.[45]Shtykhov, G.V. Drevnyj Polotsk. Minsk, 1975, Illus. 33, item 16.

A bronze ring dating from the 1340s-1360s depicts a quartet of plant shoots, accompanied by ovals in the elongated sections (9-14-2118 — Illus. 51:11). This ring was threaded onto a leather cord, on which, it seems, it was hung about the neck as a memento or amulet.

A pewter ring found in a layer from the 1360s-1380s has a shield which depicts a double braid (8-11-456 — Illus. 51:18).

Two oval-shield rings were found in layers from the 1420s. One has a design in the form of an oval created by zigzag lines, with a cross in the center (4-5-1602 — Illus. 51:16). The other has a design around the contours of the shield, created using a triangular stamp (4-1602).[46]jeb: This actually seems to describe the ring shown in Illus. 51:16; I suspect something here is mislabeled.

Illustration 49, item 6; Illustration 51, items 2, 4-5. Rings with rectangular shields. These rings were found in the same layers as those of the previous type. A pewter ring from the 1260s-1280s has the image of a cross with expanding arms (13/12-19-1123 — Illus. 51:2).

Two pewter rings from the 1340s-1360s have hatched rectangular shields depicting diamonds with dots in their corners (9/8-14-234 — Illus. 51:4; 9/8-14-1163a — Illus. 49:6, 51:5). These rings were all cast in a two-sided composite mold with an inserted rod.[47]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, pp. 239-240, Illus. 20, items 7, 13.

Illustration 47, items 17, 19, 21; Illustration 49, items 15a, b; Illustration 51, items 24-27. Rings with diamond-shaped shields. Three of these rings were found in layers from the second half of the 14th century (8-10-1819 — Illus. 47:17; 8-10-1823 — Illus. 47:19; 7/6-13-1334 — Illus. 47:21). One particular variant of this type of ring are nine complex latticework rights with diamond-shaped centers and four semi-circular arches on either side of the shield. These were all cast in pewter and were found in layers from the 1230s through the mid 14th century (K19-17; K25-76 — Illus. 49:15a, 15b; Tikhv8-14-73 — Illus. 51:26; 10/9-10-1904; 10/9-17-1361 — Illus. 51:24; 9/8-6-662 — Illus. 51:25; Slav15-14 — Illus. 51:27; Tr4-82; Tr6-100). These last two rings were cast in the same stone mold.

Illustration 49, item 7; Illustration 51, items 6-8. Rings with square shields. Three rings were found in layers from the 1260s-1360s. The earliest of these has a shield decorated with an oblique cross (13-21-767 — Illus. 49:7, 51:6). The shield of another ring from the mid-13th century depicts a diamond inscribed into the square (Tikhv11-15-22 — Illus. 51:8).[48]jeb: Illustration 51 is mislabeled. Item 8 is incorrectly marked as item 6. The item is located just above item 10 in the illustration.. A ring from the mid-14th century has a latticework shield in the form of a four-part grid (8/7-15-1325 — Illus. 51:7). These rings were all made from tin or pewter.

Rings with square- or diamond-shaped shields were cast in composite molds with inserted rods. The majority of them have visible casting seams along the sides of the shields.

To sum up what has been said, it is worth noting that rings with shields were made by urban artisans. They are almost never found in burial site antiquities. As evidence of their mass production in cities, we have the use of composite molds with inserted rods, as well as the cheap alloys of pewter used to imitate silver.

Illustration 51, item 23. Standing alone is this bronze ring with a shield in the form of two hands shaking (Got1/15-3 — Illus. 51:23). Such rings in silver are known from 12th-century England. They achieved greatest popularity in the 14th-15th centuries, particularly in Flanders and Italy.[49]Dalton, O.M. British museum. Franks Bequest Catalogue of the finger rings. London, 1912, Plate XVI, items 1006-1007, 1043, 1046, 1051. The ring from Novgorod was found in the Gothic section excavation, which teemed with Western European items. It is likely that this ring belonged to a foreigner.

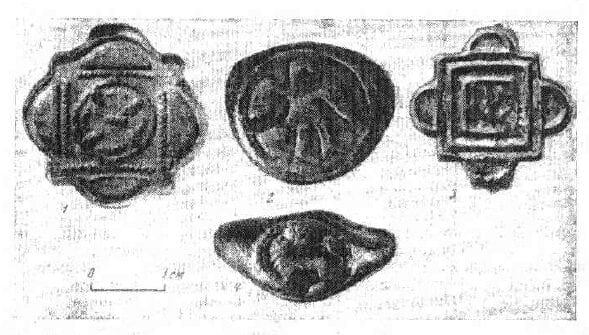

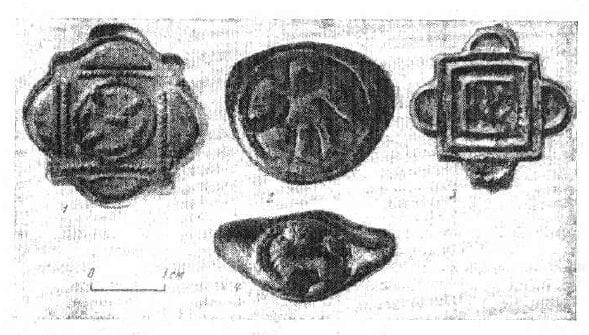

Seal Rings

Seal rings are distinguished from wide-centered rings in that their shields are thick and raised, rising in height from the line of the band. Seal rings were used to impress seals into wax or mastic. They come in multiple shapes: round, oval, rectangular, etc.

Illustration 50, item 13. The earliest example is this ring, cast from a wax model, with a round seal engraved with the image of a bird with its wings spread and its head turned to the right (below level 28-33-42 — Illus. 50:13). It dates from the first half of the 10th century (before 953). Similar seal rings have been found repeatedly in early monuments of medieval Rus’ — for example, at the Timerevskoe settlement from the 9th-10th century,[50]Bulkin, B.A., Duboe, I.V., Lebedev, G.S. Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki drevnej Rusi IX-XI vv. Leningrad, 1978, p. 93. in Kostroma burial sites (along with 10th century coins,[51]Nefedov, F.D. “Raskopki kurganov v Kostromskoj gub.” Materialy po arkheologii vostochnykh gubernij Rossii. Vol. 3. 1899, table III, item 20. during P.M. Eremenko’s digs in the lands of the Radimichi,[52]Spitsyn, A.A. “Veschi iz raskopok P. Eremenko v kurganakh Novozybkovskogo i Surazhskogo uezdov.” Zapiski Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. VIII, Issue 1-2, 1896, Table III, item 3. et.al. They have also been discovered in Bulgaria.[53]Ivanov, J. “Starob’lgarski i vizantijski pr’steni.” Izvestia na Arkheologicheskogo druzhestvo. Vol II, 1911, pp. 6, 9. Their arrival in the Slavic lands was most likely tied to Byzantine influence and is associated with early state symbolism.

Illustration 49, item 22; Illustration 50, item 9. This pewter ring from the 1160s-1170s has a raised shield with a line of pseudo-granulation around the edge, and the figure of a bird with raised wings in the center (18-19-1104 — Illus. 49:22, 50:9). The shield was cast separately in a mold, then soldered to the band.[54]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 239.

Illustration 49, item 23. This bronze seal ring dating from the 1170s-1190s has a nielloed design in the form of a cross with widening arms (Tikhv15-23-51 — Illus. 49:23).

Illustration 50, item 11. This bronze, cast ring from the 1190s-early 13th century has a seal depicting the tree of life, a subject characteristic for jewelry from the late 12th-early 13th centuries (Il12-21-275 — Illus. 50:11).

Illustration 52, item 2. This ring, cast in pewter from a wax model, comes from the 1220s-1230s. The shield depicts a bird with raised wings and its head turned to the right (15-16-961 — Illus. 52:2). The image of the bird and manner of the imagery is significantly coarser than that of the 10th century ring described above.

Illustration 49, items 26-27; Illustration 50, items 12, 15; Illustration 52, item 1. Two very similar rings were found in layers from the 1230s-1260s. Their shields have a quadrifoliate shape. One depicts a geometrical four-leaf rosette (Tikhv13-17-49 — Illus. 49:26, 50:12). The other has a square with a circle inscribed inside it (14-22-624 — Illus. 49:27, 51:1). The first ring is of bronze; the second of silver, cast from a wax model. One more quadrifoliate ring is bronze, and with a shield depicting a schematic figure of a bird with raised wings, was found in a layer from the 1260s-1280s (13-16-1534 — Illus. 50:15). Analogous rings have been found in Kiev[55]Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Vol. 1. St. Petersburg, 1896, Table V, item 8., on Knjazha Gora and in the lands of the Northern tribes[56]Samokvasov, D.Ja. osnovanija khronologicheskoj klassifikatsii i katalog kollektsii drevnostej. Warsaw, 1892, Nos. 4182, 4188. and also among the antiquties of Chernaja Rus'[57]Spitsyn, A.A. “Predpolagaemye drevnosti Chernoj Rusi.” Zapiski russkoj arkheologicheskoj obschestva. Vol. XI, Issue 1-2, 1899, pp. 303-310, Table VII, item 3. and in the lands of the Vjatichi.[58]Artsikhovskij, Kurgany vjatichej, pp. 75-77.

Illustration 47, item 20; Illustration 49, item 21. One half of a ring cast in brass (group IV), with a hexagonal shield and geometric pattern, found in a layer from the 1280s-1290s (12-19-136 — Illus. 47:20, 49:21).

Illustration 52, item 4. A ring with an oval seal depicting a relief figure of a panther, dating from the 1310s-1340s (10-15-1190 — Illus. 52:4). It was cast in pewter from a wax model. An analogous ring was found in a stone grave in the former Lida district of the Vilna province, dating from the 13th-14th centuries.[59]Spitsyn, Predpolagaemye drevnosti…, Table VI, item 8.

Illustration 50, item 19. This cast pewter ring from the 1320s-1340s has a round shield with a six-leaved plant inside a circle with rays extending in four directions (Mikh10-18-93 — Illus. 50:19).

Illustration 47, items 22-23, 27; Illustration 49, items 24-25; Illustration 50, item 20. A ring found in layers from the 1380s-1390s has a rectangular shield, divided into six sectors, two of which are covered in oblique hatch marks (7/6-15-778 — Illus 49:25; 50:20). This ring was cast in pewter using a composite mold. During the casting, the prepared shield was placed in a depression in the mold, and during the casting process the metal fused with the band.[60]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 241. This method of casting rings was further developed in the 15th century, and this was how two rings, dating to the first quarter of the 15th century, with round shields decorated with concentric circles were cast (5-8-1535 — Illus. 47:22, 4-4-1657 — Illus. 47:23). This is also how a ring from the mid-15th century with an oval shield (2-9-98 — Illus. 47:27) and two rings with shields in the form of six-petaled flowers, from the early 15th century (4-12-123; Tikhv4-14-53 — Illus. 49:24), were cast.

Illustration 49, item 28; Illustration 50, item 16; Illustration 52, item 3. This ring from the 1460s has a quadrifoliate seal, on which there are three concentric squares containing the image of a bird (2-7-1376 — Illus. 49:28, 50:16, 52:3).

All of these rings were made of pewter (group VIII).

Illustration 49, item 29; Illustration 53. Finally, it is worth noting two more seal rings. In 1951, a billon ring was found in the Nerevskij dig outside of the dated layers. This ring’s shield bears the image of a lion walking to the right. Its head is turned to the front, and its tail is depicted as a palmette.[61]jeb: See Illustration 53. The second seal ring was found in the Torgovyj dig in 1971, also outside the stratigraphic layers. Its shield depicts a bird of prey with a large beak and spread tail.[62]jeb: See Illus. 49:29. The depiction of fantastical subjects on these shields attests to the spread of images characteristic for high art and having prototypes in Byzantine culture into everyday life.

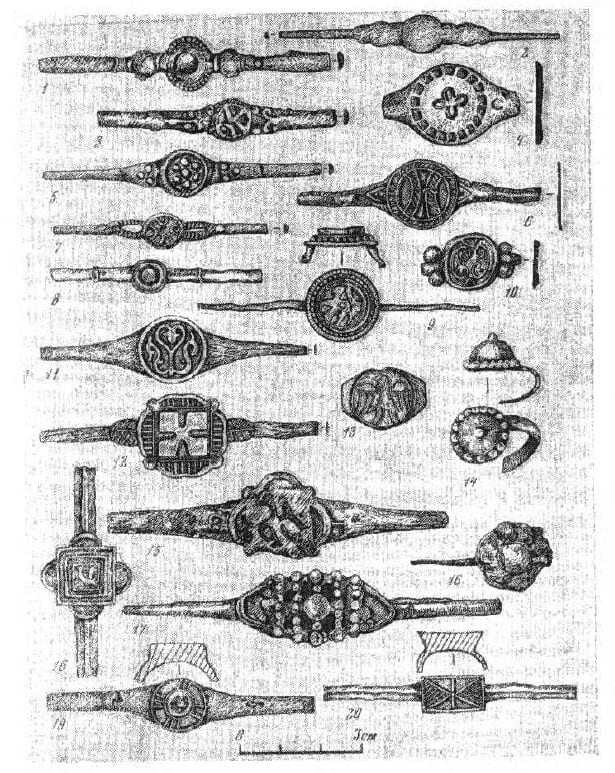

Rings with Settings

Rings of this type are typically made of round-wire or rectangular billets, less frequently from plate metal. On the face, they have round, oval, rectangular, diamond-shaped, triangular, or figurative shields with settings for glass or stones. “Novgorod jewelers used two methods for setting stones in rings. The first consists of the insert being held by “claws” which were sawn with a thin file into the upper part the setting (in modern jewelry making, this is called a prong setting [krapanovyj])… The other, which was more widely in use, was to place the insert directly into the body of the ring, while the edge of the metal was crimped around the insert.”[63]ibid.

(1) 10-17-1379; (2) 14-20-dig IE; (3) 15-14-987; (4) 11-17-1254; (5) 8-7-488; (6) 10/9-17-102; (7) 12-19-1460; (8) Slav11-14; (9) K15-71; (10) Torg26-24; (11) 13-19-829; (12) 23-26-381; (13) K21-50; (14) 13-17-1519; (15) 12-21-331

Illustration 54, item 12. The oldest are two rings with rectangular shields and light-blue glass settings. These rings were cast in a multi-component alloy (group V) in a compound mold with an inserted rod. One of them (23-26-381 — Illus. 54:12) was found in a layer from the third quarter of the 11th century; the other (16-23-765) was in a layer from the late 12th century.

Illustration 54, item 8; Illustration 80, item 4. Yet another ring with a rectangular shield containing a round, green glass setting was found in a layer from the 1170s-1190s (17-18-952 — Illus. 80:4). A ring from the 13th century has a rectangular glass insert (Slav11-14 — Illus. 54:8).

Illustration 55. This gold ring with a rectangular jasper stone surrounded by dragon heads on either side is particularly elegant (12-22-1009 — Illus. 55). It is very similar to a gold ring found in the ruins of the Lower Church in Grodno dating to the 13th-14th centuries.[64]Voronin, N.N. “Raskopki v Grodno.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury Akademii nauk SSSR. XXXVII (1951), p. 28, Illus. 14. The Novgorod rind, based on the location where it was found, dates to the 1130s-1160s.

Illustration 54, items 5-7, 9-10; Illustration 80, items 3, 8, 10, 12-15, 18, 20. Rings with round or oval settings. There are 27 of these rings in the Novgorod collection, distributed in layers from the mid-12th to the end of the 14th centuries. They are grouped according to the shape of their shields.

Two pewter rings with bezeled [gorodchatoj] shields containing dark blue glass stones were found in layers from the second half of the 12th century. One of these (18-23-2173 — Illus. 80:8) has a round shield in the form of a bundle to which large spherical granules have been soldered. The shield of the other ring (17-21-295 — Illus. 80:10) has an oval shield. These are very similar in the manner of execution to a round bezeled pendant from the early 12th-early 13th centuries (Illus. 14:11), as well as a pendant found in Belozero. Most likely, all of these items came from the same workshop.

Two plate rings with golden glass insets held by pronged settings are narrowly dated to the 1160s-1170s (18-25-784; 18-24-806 — Illus. 80:20). They were cast in pewter (group VIII) in a compound mold with an inserted rod. A third such ring was found outside the chronological layers in the Nerevskij dig in 1951. It appears that these rings were all made in the same workshop.

A particularly large group of rings has round insets held by bezels (Il17-27-336; 17-25-1375 — Illus. 80:3; Il12-21-331; 16-17-1073 — Illus. 80:12; 16-21-1221 — Illus. 80:18; 15-22-737; 14-14-1905 — Illus. 80:14; Torg26-24 — Illus. 54:10; 13-19-1165; 13-18-1276; 13/12-19-1378; 13/12-14-1967; 13/12-11-500; 12-19-1460 — Illus. 54:7; 11-11-595 — Illus. 80:15; K22-18; Ljud9-19; 8-17-844 — Illus. 54:5).

Unique in the manner of its setting is a bronze ring from the mid-14th century (Il7-14-50 — Illus. 80:13). Its spherical inset of grey glass is seated on a raised shield, out of which four “claws” rise to clasp the stone.

Two bronze (group V) rings dating from the 14th century have insets which are set into round cast shields, decorated around the edges with pseudo-granulation (10/9-17-102; 8-7-488).

The shield of a bronze ring from the 1370s-1380s is in the form of a rosette made of a thin corrugated thin band surrounding the bezel (K15-71 — Illus. 54:9). This manner of creating the setting to hold a precious stone in the 14th-15th centuries drew the attention of Ju.D. Aksenton.[65]Aksenton, Ju.D. Dorogie kamni v kul’ture drevnej Rusi. Avtoref. kand. dis. Moscow, 1974, p. 11. A corrugated metallic band was used, for example, as a setting on the poruchi for Metropolitan Aleksej and on a cover for the icon The Tenderness of the Mother of God in the Arsenal collection (State Arsenal Palace, No. 15462).

Illustration 54, item 1; Illustration 80, items 6, 11, 16. Rings with oval settings on oval shields. Six oval settings have been found, in layers from the mid 12th-mid 14th centuries (18-21-1068; 17-18-941 — Illus. 80:16; 16-20-1021; 16-22-107 — Illus. 80:6; 10-17-1379 — Illus. 54:1; 9-8-505 — Illus. 80:11).

Illustration 54, items 2-4. Rings with round settings on four-sided shields. These items were in use particularly in the 13th century (15-14-987 — Illus. 54:3; 14-20-dig IE — Illus. 54:2, 11-17-1254 — Illus. 54:4; 10-16-2061).

Illustration 54, items 11, 14-15. A ring with a diamond-shaped shield and setting (13-17-1519 — Illus. 54:14), a ring with a complex oval shield cast using a wax model (13-19-829 — Illus. 54:11), and a ring with a triangular shield and setting (12-21-331 — Illus. 54:15) all date to the 13th century.

Illustration 54, item 13. This bronze ring with a diamond-shaped setting decorated on all sizes with openwork loops was found in a layer from the early 14th-century (K21-50 — Illus. 54:13). This ring is very similar to the contemporaneous openwork shield rings (Illus. 51:24-27), distinguished only by the presence of its setting.

Illustration 80, item 5. This ring from the 1380s-1390s has an octagonal, green, glass inset (7-12-2116 — Illus. 80:5).

With the exception of one gold ring with a jasper stone, all of the other rings have insets of glass. The most common color was dark blue (30% of the entire collection), followed by green (20%), translucent yellow (20%), red (13%), black (10%) and grey (7%). The insets were typically low-convex, in the form of a cabochon; flat settings are found less frequently.

One exception is the inset for a silver ring from the early 14th century (10-17-1379 — Illus. 54:1), consisting of two transparent pieces glued together; the upper half is convex, the lower half is flat. Both halves have been painted red, giving the entire setting a pinkish hue. Analogous crystal insets, glued together from two halves, came into widest use in Novgorod in the 14th century (in layers from 1367-1394). Chemical analysis of the pink paste showed that is most likely shellac which has been dyed[66]Aksenton, Dorogie kamni…, p. 14. Highlighted insets of rock crystal are known from several monuments of applied art from the 14th-15th centuries.

The majority of rings which have been studied scientifically consist of independently cast settings which have been soldered to a forged ring. This method of production was used throughout the entire existence of rings with settings.[67]Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 240. Also used was the method of casting rings in a compound mold with an inserted rod. In order to create a seat for the insert in the shield, the mold had a special depression, into which a clay sphere was placed. Creating rings using lost wax was less widely used.

The material used to create rings with settings was primarily pewter, as well as alloys from group V and brass.[68]Konovalov, Tvetnye metally… p. 148.

Rings with settings were made by urban artisans. They were most commonly worn in the cities and are found in rural burial sites relatively infrequently.

(1) 15-20-1292; (2) K24-16; (3) 17-25-1375; (4) 17-18-952; (5) 7-12-2116; (6) 16-22-107; (7) 17/16-22-1184a; (8) 18-23-2173; (9) 20-21-1986; (10) 17-21-295; (11) 9-8-505; (12) 16-17-1073; (13) Il7-14-50; (14) 14-14-1905; (15) 11-11-595; (16) 17-18-941; (17) 19-23-296; (18) 16-21-1221; (19) 13-14-1801; (20) 18-24-806; (21) 20-25-220.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Nedoshivina, N.G. “Perstni.” Ocherki po istorii russkoj derevni X-XIII vv. Trudy GIM, issue. 43. Moscow, 1967, pp. 253-254. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | jeb: See the introduction for a description of how to decipher these attribution numbers. |

| ↟3 | jeb: If no illustration:item-number reference is given, such as with this example, then the referenced item is not pictured in any of the illustrations. |

| ↟4 | Ryndina, N.V. “Tekhnologia proizvodstva Novgorodskikh juvelirov X-XV vv.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii SSSR. 117 (1963), p. 240. |

| ↟5 | jeb: See my translation of this article into English here: https://rezansky.com/jewelry-production-technology-in-10th-15th-century-novgorod |

| ↟6 | jeb: See the introduction for further details about the varous groups of alloys used to create items of jewelry found in the Novgorod digs. |

| ↟7 | Nedoshivina, Perstni, p. 264. |

| ↟8 | Ryndina, Technologia proizvodstva…, p. 240. |

| ↟9 | Izvestija Arkheologicheskoj komissii, 15 (1905), p. 320. |

| ↟10 | Ryndina, Tekhnologija proizvodstva…, p. 240. |

| ↟11 | Latvijus PSR arheologija. Riga, 1974, table 52, item 10; Kivikoski, E. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands. Helsinki, 1973, Illus. 753. |

| ↟12 | Selirand, J. Eestlaste matmiskombed varafeodaalsete suhete tarkamise perioodil. Tallin, 1974, table XL, item 8; Katalog der Ausstellung zum X. Archaeologischen kongress in Riga. Riga, 1896, Table 21, items 3-5, 7-8; Shnore, E.D. Asotskoe gorodische. Riga, 1961, Table VI, items 42, 49, 56; Lietuviu liaudies menas. Vilnius, 1958, No. 523; Smirnov, A.P. “Ocherki drevnej i crednevekovoj istorii narodov Srednego Povolzh’ja i Prikam’ja.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii SSSR. 28 (1952), p. 124, Table XXX, items 6, 9. |

| ↟13 | Nedoshivina, Perstni, p. 263, illus. 33, item 8; Selirand, Eestlaste matmiskombed…, table XL, item 2, p. 355; Kivikoski, Die Eisenzeit Finnland, Illus. 1094; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 20 (1896), Table III, item 10. |

| ↟14 | jeb: See the images and description of this item in my translation of the chapter on bracelets, https://rezansky.com/jewelry-of-medieval-novgorod-10th-15th-centuries-bracelets/ |

| ↟15 | jeb: Plaited 2×2? |

| ↟16 | Nedoshivina, Perstni, p. 257, Illus. 32, item 3. |

| ↟17 | jeb: A stamp in the form of a triangle containing 3 raised dots. |

| ↟18 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236. |

| ↟19 | Konovalov, A.A. Tsvetnye metally…, pp. 143, 145. |

| ↟20 | jeb: The original references illus. 46:24, which doesn’t exist. It appears this is a typo and should have referenced illus. 46:14. |

| ↟21 | Arbman, H. Birka. Vol. II. Upsala, 1940, Table III, items 8-10; Tallgren, A.M. Zur Archaeologie Eestis. Vol. II. Dorpat, 1925, p. 103, illus. 136; Nedoshivina, Perstni, pp. 269-270, illus. 31, items 2, 4; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 10 (1893), table II, item 11; 25 (1901), table XXV, item 7. |

| ↟22 | Nedoshivina, Perstni, pp. 257-258, Illus. 31, item 5. |

| ↟23 | Stenberger, M. Die Schatzfunde Gotlands der WIkingerzeit. Vol. II. Lund, 1947, Table 39, item 2; Selitrand, Eestlaste mamiskombed…, pp. 352-353; Shnore, Asotkoe gorodische, Table VI, items 40, 47; Nedoshivina, Perstni, Illus. 31, items 5-6; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 20 (1896), Table XIII, items 21-22; 29 (1903), Table XXIII, items 38-39. |

| ↟24 | jeb: See the images and description of this item in my translation of the chapter on bracelets, https://rezansky.com/jewelry-of-medieval-novgorod-10th-15th-centuries-bracelets/ |

| ↟25 | Artsikhovskij, A.V. Kurgany vjatichej. Moscow, 1930, p. 73; Ravdina, T.V. Khronologija «vjaticheskikh» drevnostej. Avtoref. kand. dis. Moscow, 1975, p. 11. |

| ↟26 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236. |

| ↟27 | Ravdina, T.V. “Drevnerusskie litye perstni s geometrichestkim ornamentom.” Slavjane i Rus’. Moscow, 1968, pp. 133-138. |

| ↟28 | jeb: This is a diamond shape with a dot in the middle. |

| ↟29 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236. |

| ↟30 | Gorjunova, E.I. “Merjanskij mogil’nik na Rybinskom more.” Kratkie coobschenija Instituta istorii materialnoj kultury Akademii nauk SSSR. 54 (1954), Illus. 71, item 11. |

| ↟31 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236, Illus. 20, item 5. |

| ↟32 | Voronin, N.N. “Otchet o raskopkakh v Staritse Kalininskoj obl.” Arkhiv Instituta arkheologii Akademii nauk SSSR. R-1, d. 358, p. 108. |

| ↟33 | jeb: Note that this item is incorrectly labeled in illustration 50. There are two rings marked #16, to the left and right of rings #15 and #17. The ring on the left is the actual #16. The ring on the right should be marked #18. |

| ↟34 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 236. |

| ↟35 | Nikol’skaja, T.N. “Kuznetsy zhelezu, medi i serebru ot vjatich.” Slavjane i Rus’. Moscow, 1968, illus. 3, item 2. |

| ↟36 | Latysheva, G.P. “Raskopki kurganov u st. Matveevskaja v 1953 g.” Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki Moskvy i Podmoskov’ja. Moscow, 1954, illus. 6, item 2. |

| ↟37 | Mongajt, A.L. “Staraja Rjazan’.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR. 49 (1955), illus. 137, item 4. |

| ↟38 | Karger, M.K. Drevnij Kiev. Vol. 1. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958, table XIV. |

| ↟39 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 241. |

| ↟40 | Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 20 (1896), Table XIII, item 31. |

| ↟41 | Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, 26 (1902), Table XV, item 11. |

| ↟42 | Ryndina, Technologia proizvodstva…, pp. 239-240, Illus. 20, item 9. |

| ↟43 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 239, Illus. 21, item 1. |

| ↟44 | Medvedev, A.F. “Novye materialy po istorii Goroditsa na Volge.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta arkheologii Akademii nauk SSSR. 113 (1968), Illus. 7, 9. |

| ↟45 | Shtykhov, G.V. Drevnyj Polotsk. Minsk, 1975, Illus. 33, item 16. |

| ↟46 | jeb: This actually seems to describe the ring shown in Illus. 51:16; I suspect something here is mislabeled. |

| ↟47 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, pp. 239-240, Illus. 20, items 7, 13. |

| ↟48 | jeb: Illustration 51 is mislabeled. Item 8 is incorrectly marked as item 6. The item is located just above item 10 in the illustration. |

| ↟49 | Dalton, O.M. British museum. Franks Bequest Catalogue of the finger rings. London, 1912, Plate XVI, items 1006-1007, 1043, 1046, 1051. |

| ↟50 | Bulkin, B.A., Duboe, I.V., Lebedev, G.S. Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki drevnej Rusi IX-XI vv. Leningrad, 1978, p. 93. |

| ↟51 | Nefedov, F.D. “Raskopki kurganov v Kostromskoj gub.” Materialy po arkheologii vostochnykh gubernij Rossii. Vol. 3. 1899, table III, item 20. |

| ↟52 | Spitsyn, A.A. “Veschi iz raskopok P. Eremenko v kurganakh Novozybkovskogo i Surazhskogo uezdov.” Zapiski Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. VIII, Issue 1-2, 1896, Table III, item 3. |

| ↟53 | Ivanov, J. “Starob’lgarski i vizantijski pr’steni.” Izvestia na Arkheologicheskogo druzhestvo. Vol II, 1911, pp. 6, 9. |

| ↟54 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 239. |

| ↟55 | Kondakov, N.P. Russkie klady. Vol. 1. St. Petersburg, 1896, Table V, item 8. |

| ↟56 | Samokvasov, D.Ja. osnovanija khronologicheskoj klassifikatsii i katalog kollektsii drevnostej. Warsaw, 1892, Nos. 4182, 4188. |

| ↟57 | Spitsyn, A.A. “Predpolagaemye drevnosti Chernoj Rusi.” Zapiski russkoj arkheologicheskoj obschestva. Vol. XI, Issue 1-2, 1899, pp. 303-310, Table VII, item 3. |

| ↟58 | Artsikhovskij, Kurgany vjatichej, pp. 75-77. |

| ↟59 | Spitsyn, Predpolagaemye drevnosti…, Table VI, item 8. |

| ↟60 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 241. |

| ↟61 | jeb: See Illustration 53. |

| ↟62 | jeb: See Illus. 49:29. |

| ↟63 | ibid. |

| ↟64 | Voronin, N.N. “Raskopki v Grodno.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury Akademii nauk SSSR. XXXVII (1951), p. 28, Illus. 14. |

| ↟65 | Aksenton, Ju.D. Dorogie kamni v kul’ture drevnej Rusi. Avtoref. kand. dis. Moscow, 1974, p. 11. |

| ↟66 | Aksenton, Dorogie kamni…, p. 14. |

| ↟67 | Ryndina, Tekhnologia proizvodstva…, p. 240. |

| ↟68 | Konovalov, Tvetnye metally… p. 148. |

2 Replies to “Jewelry Of Medieval Novgorod (10th-15th centuries): Rings”