After reading about medieval Rus’ torcs in Седова, М.В. «Шейные гривны.» Ювелирные изделия древнего Новгорода (Х-XV вв.). Москва: Издательство «Наука», 1981, с. 22-23. (see my translation here: https://rezansky.com/jewelry-of-medieval-novgorod-10th-15th-centuries-torcs/), I was interested to learn more about these rare archeological finds. The article I have read and translated below is perhaps the most in depth work dedicated to this subject, focused on finds in northeastern and northwestern Rus’. It is interesting that the author states torcs were found (in all but one case) only in female graves, where other sources attest that they were worn by both men and women until the 12th-13th centuries, when it became predominantly a female decoration.

Russian Torcs

A translation of Фехнер, М.В. “Шейные гривны.” Очерки по истории русской деревни X-XIII вв. Труды Государственного исторического музея, 1967 (43), с. 55-88 / Fekhner, M.V. “Shejnye grivny.” Ocherki po istorii russkoj derevni X-XIII vv. Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja, 1967 (43), pp. 55-88.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here: https://www.twirpx.com/file/2508922/. ]

Metallic hoops worn as decoration on the neck are known among many peoples of Western and Eastern Europe, as well as the Near and Middle East. Among various peoples and at various periods in time, they were used first predominantly as part of female, and then later primarily as part of the male costume. However, in both cases, this form of decoration was the property only of local nobility.

An analogous situation was observed as well in Rus’ during the 10th-13th centuries. Here too, torcs were not widely used by all layers of society. Judging by numerous Russian treasure troves from the 10th-first half of the 13th centuries, they constituted an integral part of princely and boyar costume.[1]Korzukhina, G.F. Russkie klady IX-XIII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1954, pp. 62-63. In ordinary burial mounds, finds of torcs are relatively rare, attesting to their limited distribution among the primary class is Rus’ at that time – peasants.

As such, among digs of over 10,000 village burial mounds in north-eastern and north-western Rus’, only 400 examples of torcs have been found in total. On several of the torcs, signs of prior repairs were preserved, evidencing that they represented a known value.

It is worth noting, then, that finds of torcs, as a rule, are related to female burials, and moreover the wealthy, based on their burial inventories. They are typically found in graves as a single example[2]Torcs were found in pairs in 10 graves: near the villages of Ol’gii Krest (burial mounds 1 and 7), Shakhnogo, and Vakhrushego in the Leningrad region (Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, No. 29, p. 61; No. 18, pp. 38, 131); in Odintsovo in the Moscow region (burial mound 46, archive of the Institute of Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, R-1/2182); in Vlazovichi (burial mounds 25, 26, 41) and Kazarichi in the Brjanskaja region (burial mound 63, State Historical Museum, inventory No. 32884), and Dudenevo in the Kalinin region (burial mound 10, Izvestija Arkheologicheskoj komissii, 1904 (6), p. 10)., together with a larger quantity of jewelry items of bronze and silver (temple rings, rings, bracelets, amulets), necklaces of stone and glass beads, decorated crafts of bone, etc. Torcs are also found in twin burials – simultaneously buried men and women who, it’s well known, belong to the richest graves of village cemeteries from the 10th-13th centuries.

Based on this, we can conclude that among the rural population, torcs were in use only among the more prosperous segments of society and was affiliated with female costume.[3]In the Baltic region in the 10th-13th centuries, torcs also were common forms of jewelry (Nukshinskij burial ground, p. 35; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, No. 14, p. 26). Torcs are characteristic of female burials in 9th-10th century Mordovians and Muroms (Alikhova, A.E. “Iz istorii mordvy kontsa I – nachala II tys. n.e.” Is drevnej i srednevekovoj istorii mordovskogo naroda. Saransk, 1959).

The majority of torcs from the territories studied by us were made of copper and bronze; a few examples have signs of silver plating. They were also made of alloys – copper and silver (billon), and pewter. They were sometimes made of iron. As for torcs of fine silver, they are extremely rare in village cemeteries, and were typically found in troves.

Torcs found in 10th-13th century records can be divided into twisted [drotovye], wire [provolochnye], plate [plastinchatye], and plaited from several strands [vitye iz neskol’kikh provolok]. Each of these groups has an array of types based on cross section, form of the terminals, clasps, and also by their method of creation. We have attempted to present all of this information chronologically in order show how, over the course of time and based on fashion, one type of torc fell out of favor and others arose. Comparing the approximate dates of different objects found in the mounds along with the torcs, and taking into account the funeral rites inherent in the population of northeastern and northwestern Russia at certain times, I managed to date various types of torcs accurate to the century. This gives us the ability to use torcs as a milestone for dating archeological finds where they are encountered.

The impression is that in the 10th century among the Rus’ population, wearing of torcs was still uncommon. Torcs of this period do not vary in type and few examples have been uncovered. They started to come into fashion only in the 11th century, in particular in the second half, and it appears they started to fall out of everyday life in the late 12th-early 13th centuries.

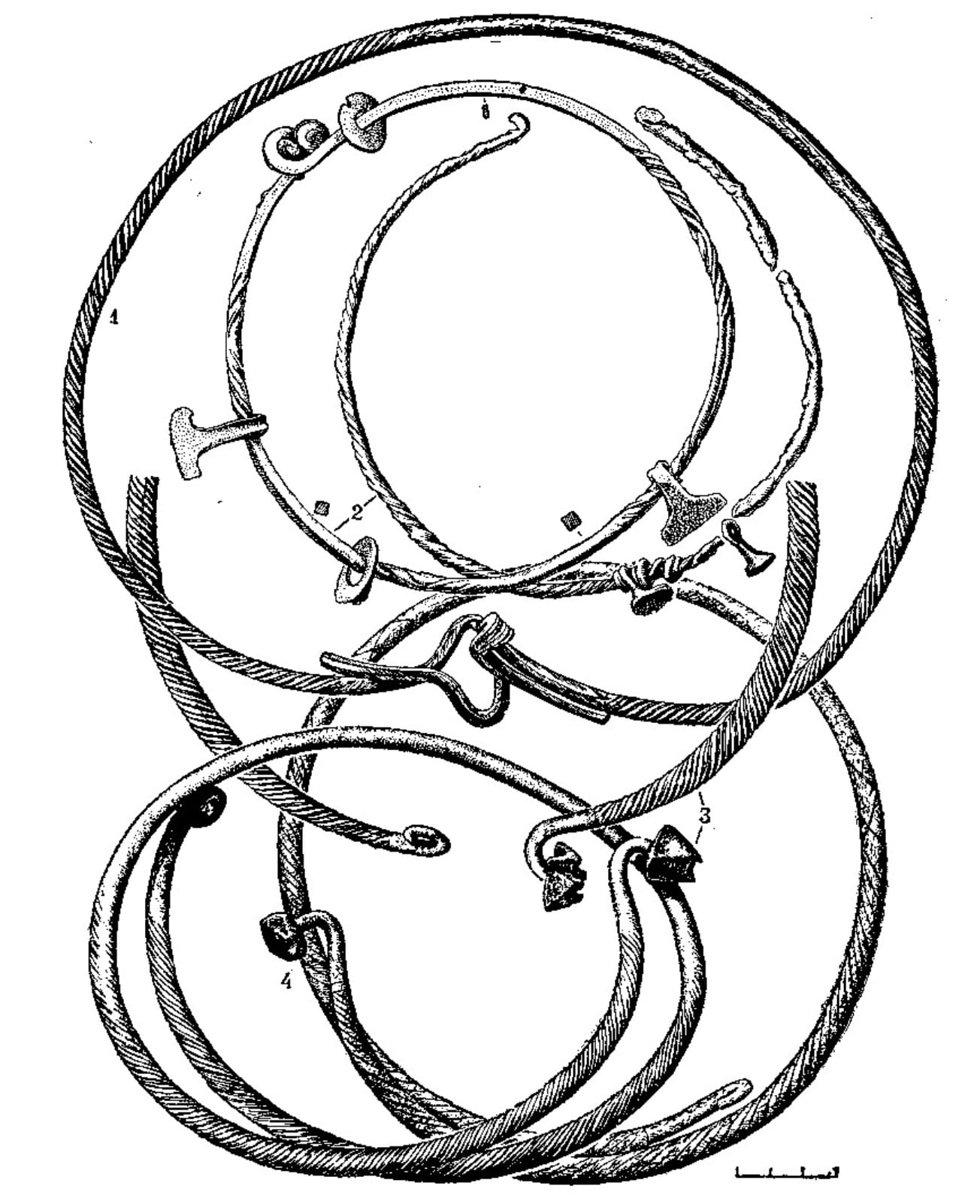

We start our review of this category of decoration with torcs made from solid wire. Amongst these, the earliest torcs were made from round or three-sided billets, the entire surface of which (with the exception of the nape and ends) was decorated with slanted, screwlike cuts. This design was created by twisting the billet (either cast or forged) in a heated state. The more strongly it was twisted, the more closely together the edges on the body of the torc would located. Then, using a special mandrel, the billet was bent into the form of a neck, and then the nape area and ends were forged in order to obliterate the facets and made the surface of the work smooth in these areas. These twisted torcs have a clasp in the form of two loops, with one flattened to serve as a hook, or the lock could consist of a loop and a multifaceted head (Illustration 7, items 1, 4). In digs, these torcs are often encountered with broken off heads of clasps, indicating it seems the soldered joint between the body and the clasp was not very strong.

Twisted torcs with diameters ranging from 20-25 cm were fastened not at the back of the neck, but at the chest. There are also examples with terminals which overlap significantly, which were worn unfastened.

In the studied territories, twisted torcs are encountered relatively rarely. They were uncovered in 22 locations for a quantity of 28 examples: 20 of bronze and copper, and 8 of pure silver. Among the last 6 torcs found in troves buried around the turn of the 9th-10th centuries, one was an incidental find in Pskov region and only one example was found in the remains of a funerary pyre near the town of Kabanskoe in the Jaroslav region (appendix I, item a).

In treasure troves containing twisted silver torcs, there have also been found (silver) torcs decorated with small hexagonal scales. These have been encountered in the studied territory as individual examples. Outside of these troves, a similar torc has only been found once, as an incidental find in the Kaluga region.[4]State Historical Museum, inventory no. 28607.

As for twisted torcs of bronze and copper which, with one exception, were found during digs of rural settlements,[5]Tumovskoe village, Vladimir region; Gorjunova, E.I. Etnicheskaja istorija Volgo-Okskogo mezhdurech’ja. Moscow, 1961, pp. 163, 175, Illus 78, items 15, 16. the remaining eighteen were found in burial mounds from cremations. It is worth noting that torcs in burial sites were always located in the center of the bonfire, most commonly atop heaps of calcified bones. In many cases, either within the torc or nearby, there were stacks of various other implements of the female dress: shell-shaped fibulae, bracelets, horseshoe-shaped clasps, necklaces of glass and stone beads, etc.[6]In burial mounds near the towns of Vikhmes, Gorodische, Karlukha, Kashiko, Kostino, Pod’el’e, Shakhnogo, and Jarovshina in the Leningrad region, and near Polezhanki in the Smolensk region.

Shell-shaped fibulae found together with twisted torcs belong to types 51B, 51C, and 55, according to Ja. Petersen, and date to the second half of the 10th century – early 14th century.[7]Petersen, Ja. Jaroslavskoe Povolzh’e X-XII vv. Moscow, 1963, p. 82. Beads of translucent glass (lemon-shaped, melon-shaped, and spherical) found together with twisted torcs in the same burial complexes may also belong to the 10th-early 11th centuries.[8]Ocherki po istorii russkoj derevni X-XIII vv. Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja, 1959 (33), pp. v, 1, 13, 22. Finally, twisted torcs are found with horseshoe-shaped fibulae with terminals in the shape of multi-faceted heads equipped with spikes or protrusions may be of great importance for dating twisted torcs. These fasteners are of a purely Finnish type, characteristic of the 10th century.[9]Salmo, H. Finnische Hufeisenfibeln. Helsinki, 1956, pp. 28, 38, 50.

Based on this data and the fact that twisted torcs were found in northeast and northwest Rus’ exclusively in funerary pyres, it is possible to conclude that they were common amongst the local population mainly in the 10th century. The range of twisted torcs was relatively large: they are known from finds from the 9th-10th century Kama region and southern Russia, and in Mordovian and Murom graves from the 9th-11th centuries, as well as in archeological finds in northern Europe from the same time (Appendix I, a).

It is worth noting that twisted torcs with clasps in the form of a pair of loops, of which one is flattened to serve as a hook, was characteristic of Latvia in the 7th-12th centuries. The birthplace, however, of twisted torcs with multi-faceted heads with spikes or protrusions (similar to those on horseshoe-shaped fibulae) is Finland.[10]Stenberger, M. Die Schatzfunde Gotlands der Wikingerzeit. Vol. 1. Uppsala, 1958, p. 125; Kivikoski, E. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands. Vol. 1. Helsinki, 1947, p. 48. Amongst the 10 twisted torcs found in the lands under our review and with completely preserved clasps, six have the same kind of heads as the twisted torcs of Finland (Illustration 7, item 3).[11]Torcs with heads covered with spikes or protrusions were found near the villages of Mandrogi, Kashino, Pod’el’e, Shanginichi (in two burial mounds), and Jarovschina in the Leningrad region. This allows is to hypothesize that twisted torcs in northeastern and northwestern Rus’ were imported from Finland and the Baltic region, and moreover that the majority of finds of this kind of torc were concentrated in southeast Ladoga and the area around Lake Chudskoe. This is further supported by the fact that the technique for twisting metal began to be used by Russian artisans no earlier than the 12th century.[12]Ryndina, N.V. “Tekhnologia proizvodstva novgorodskikh juvelirov.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii SSSR. 1963 (117), p.232.[13]jeb: See my translation of this article here: https://rezansky.com/2020/01/jewelry-production-technology-in-10th-15th-century-novgorod/

Typologically similar to the torcs described above are torcs made from wire that is diamond-, trapezoid- or hexagon-shaped in cross section. In order to make these easier to wear, the nape section of the ring was forged into a round shape. The outer sides of the ends of this type of torc were typically covered in ornamentation created with punches in the form of rings, points, miniature triangles with three hemispherical bulges inside, etc. The terminals of the torcs end in multi-faceted heads, or more often, small, round heads called ryl’tsa (Illustration 8, items 4 and 5).

Similar torcs have been found in both incineration and burial gravesites, associated with clothing, from the 10th-early 11th centuries, allowing us to date them to the same time period. In one of the burial mounds near Shakhnovo (Leningrad region), a torc made from faceted wire was found together with one that was twisted (Appendix I, b).

In northwestern and northeastern Rus, only 18 twisted torcs of this type have been found, out of which 15 were found in the southwestern Ladoga region and on the eastern shore of Lake Chudskoe, that is, the area of distribution for torcs with faceted sides and twisted torcs coincide (Illustration 9). Analogous torcs are well known in Finland.[14]Kivikoski, E. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands. Vol. II. Helsinki, 1951, p. 6, Table 83, item 675. Apparently, it was from there that they reached the Rus’.

To this list of imported goods, we should also add torcs made from square-shaped wire, either completely twisted, or twisted for only part of its length (typically in four places). These torcs were only made of iron. They are small in diameter, such that, it seems, they were tightly wrapped around the neck. The clasp is made of a loop and a hook, or two loops (Illustration 7, item 2). They were fastened not on the chest, as described above, but at the nape. These torcs were found primarily in fragments in 23 locations: in two hillforts, in one village, and in 45 burial mounds, out of which 32 were cremations (Appendix I, v), and the remaining 13 were burials.[15]Iron torcs were found in burials in the following locations: near the village of Dudino in the Volgograd region; near the villages of Zaozer’e, Il’ino, Krjuchkovo, and Nikol’skoe in the Leningrad region; in Beseda, Kon’kovo, Tagan’kovo, and Cherkizovo in the Moscow region; near the village of Khreple in the Novgorod region; near the villages of Timerovo (burial mound 375), Krivets, and in a barren of Plav’ in the Jaroslav region. In some graves where the torcs were relatively well preserved, they were found with iron amulets in the form of smooth circlets and miniature hammers were found on them. It is possible that iron torcs were also worn as a basis that was wrapped in a bronze spiral or ribbon. An example of this was found in burial mound 54 in the Timerovo burial ground.

○ – Twisted

◓ – With an arc of various sections

□ – Made from square wire

▼ – Twisted with looped terminals

⦙ – Trade routes

Torcs of this type were distributed throughout northern Europe: in Denmark, Norway, and in the in Åland Islands (Finland). The largest number of finds, however was in Swedish territory.[16]Paulsen, P. Axt und Kreuz in Nord und Osteuropa. Bonn, 1956, p. 205; Kivikoski, E. “Kvarnbacken.” Ein Gräberfeld der jüngeren Eisenzeit auf Åland. Helsinki, 1963, p. 84. There, in a single burial ground in Birka, iron torcs made from square wire, either completely or partially twisted, were found in 51 graves – in 41 cremations and 10 burials.[17]Birka, tables.[18]jeb: I was unable to locate the original reference this refers to. The majority of these were found with iron hammer-shaped pendants. The dominant portion of these were extremely crudely finished, such that it is sometimes difficult to determine whether they were hammers, crosses or simply circles. Based on the dating of the complexes where these were found, we can hypothesize that the time period of greatest distribution of iron torcs with hammer-shaped pendants was the late 10th-early 11th century.[19]Paulsen, op. cit., pp. 205-206. Perhaps only 3-4 of the Birka burials can be dated to an earlier time. According to Petersen, single-shell fibulae of type 37 and a sword of type E or D found alongside iron torcs provide a basis to date these graves to the late 9th-early 10th centuries.[20]Birka, burials 385, 854, 1151, 1158. In Sweden, judging by the material from the Birka burial ground, iron torcs were worn by both men and women.

Scandinavian scholars note that the hammer-shaped amulets found on torcs imitate an actual hammer, the symbol of the thunder god Thor, and that they were worn for magical purposes. However, in pre-Christian times in Sweden and other countries of northern Europe, it was not customary to wear cult objects as decoration. Therefore these Thor’s hammers, the most basic form of which appeared in northwestern Scandinavia by the 9th century, are found in early Viking age grave sites only as exceptions. Only with the introduction of Christianity in the late 10th-early 11th century did wearing these amulets on torcs become common; believers of the old pagan religion wore Thor’s amulets to contrast the Christian symbol of the cross.[21]Paulsen, op. cit., pp. 219-221; Stenberger, op. cit., p. 167.

The time when iron torcs existed in the Rus’ lands coincides with that of their greatest distribution in Scandinavia. Thus, the vast majority of these torcs was found in burial mounds with cremations or burials dated using shell-shaped or trefoil fibulae and several types of beads to the late 10th-early 11th century. Only a small number of iron torcs (6 examples) are dated to later times. For example, the torcs from burial mounds near the villages of Dudino (Volgograd region), Zaozer’e (Leningrad region) and from the outskirts of Moscow, found with western European coins from the second half of the 11th century and latticework rings, date to the last 11th or even early 12th century.

In the lands of medieval Rus’, iron torcs are found in burial mounds of the local population on in female graves. Individual male graves which also contained torcs appear to be Scandinavian, based on the burial clothes.[22]For example, mound 375 from the Timerovo burial ground. The prevailing location of these torcs in Sweden and their relatively small contribution to grave finds from medieval Rus’ burial mounds lead us to see these decorations as Scandinavian imports. It is characteristic that the majority of finds of iron square-wire torcs are along the primary trade routes linking northern Europe to the lands of the East. We cannot rule out, however, that some of these torcs may have been of local production.

Along with the aforementioned torcs which existed on the studied territory for a relatively short time, primarily in the late 10th-early 11th centuries, we also find one more type of torc distributed among the medieval Rus’ population throughout the 11th century. These are torcs with torcs which go well past one another, with cross-sections of an equilateral triangle with a broad base; the nape area of the decoration where it touches the neck is round in cross-section. The face of these torcs are decorated with “wolf’s teeth”, a typical ornament for this period in the form of a miniature triangle with three hemispherical dots inside. The terminals have heads of various forms (rosettes, polyhedrons, etc.) which were cast separately and then were seated onto the upturned ends of the torc (Illustration 10, item 2). Sometimes the ends were simply bent into a hook, for example the torc from a burial mound near the village of Marishkino in the Moscow region (Illustration 10, item 3).

Similar neck rings were widespread among the residents of the Sozha river basin, known in the literature called torcs of the “Radimichi” type.[23]Rybakov, B.A. Radzimichy. Pratsy, III. Minsk, 1932, p. 90. Similarly shaped torcs are also known in the Baltic region dating to the 10th-12th centuries. They differ from the Russian ones only in that the terminals are pointed, rather than ending in heads.[24]Shnore, E.D., Zaids, T. “Nukshinskij mogil’nik.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii Latvijskoj SSR. 1957 (1), pp. 27-29.

In the territory under review, torcs of the “Radimichi” type with triangular cross-sections have been found in 11 locations, numbering 23 examples (Appendix I, g).

A further development of this type of torc is represented by rings of thin wire, triangular in cross section, with overlapping gabled-plate [dvuskatnoplastinchatnyj] terminals, that is, ends with inner surfaces curved toward the center (Illustration 10, item 1). These torcs are decorated with the same triangles and points as the “Radimichi” type. The ends are shaped as a pair of metallic bands, to which square plaques with raised decoration were sometimes soldered, as can be seen on examples from burial mounds in the Moscow region (near the villages of Volkovo, Pokrov, Tushino, Troitskoe, Odintsovo, and Savvinskaja Sloboda). A similar plaque, possibly from a gabled-plate torc, was found near the hillfort of Kryzhovo (Pskov region) as part of a trove from the 11th-early 12th centuries.[25]State Historical Museum, inventory no. 43891. We should mention, however, that similar shield-plaques were also attached to torcs made from multi-faceted wire. Square plaques with raised rosettes are also found on a gilt silver torc from the Nevel’ trove from the 11th-early 12th centuries (Pskov region), which has terminals which are not gabled, but faceted.[26]Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi XI-XIII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1936, Table VIII, item 1; Korzukhina, op. cit., pp, 97-98.

All these shield plaques, to our knowledge, were created by casting, with the exception of the one from the village of Pokrov, which was punched.

Gabled-plate torcs were typically made of low-grade silver alloy, however examples of bronze and silver-plated copper have also been found. Compared to “Radimichi” torcs, these are lighter and more economical in their use of metal, but technologically they are similar. Torcs of this type were, undoubtedly, products of urban artistry.

It appears that gabled-plate torcs were most widespread in the 12th century, although in particular cases they have been found in monuments from earlier times. For example, in a burial mound near the village of Sel’tso (Pskov region), a torc with gabled-plate, overlapping terminals was found with decorations characteristic of the 11th century — bracelet-like temple rings with knotted ends, and gold-glass and prismatic beads of blue, transparent glass with white diamond-shaped inserts (Appendix I, d). In truth, it is worth mentioning that this example differs somewhat from other gabled-plate torcs. It’s terminals, which are similar to those of the “Radimichi” type, end in multi-faceted terminals. A neck ring found near the village of Zalakhtov’e (burial mound 20) in the Pskov region may also be dated to the 11th century. On this example, the terminals are significantly shorter than on other gabled-plate torcs. It also differs from others in that along the lower border of its terminals, there is a series of round holes, from which hang pear-shaped bells with cross-shaped openings and a round shield.[27]Zapiski otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva.Vol. IX. St. Petersburg, 1913, p. 261, Illustration 29, item 2.

By mapping where gabled-plate torcs have been found, we were able to identify the region of their widest use. Out of 17 finds of this torc that we are aware of, 11 were concentrated to the outskirts of Moscow and Zvenigorod (Illustration 11). Of these, in three groups of burial mounds (near the villages of Volkovo, Troitskoe and Tushivo), they found torcs with completely identical terminals, confirming that they were all poured in the same mold, that is, they were all made in the same workshop.[28]Avdusina, G.A. “Tri kurgany gruppy u Zvenigoroda.” Istoriko-arkheologicheskij sbornik MGU. Moscow, 1962, pp. 278-280; Rybakov, B.A. “Produktsia russkikh remeslennikov v X-XIII vv.” Uchenye zapiski MGU. 1947 (93), Illustrations 4-6. Keeping this in mind, as well as the concentration of finds of gabled-plate torcs near the aforementioned towns, we are able to hypothesize that the center of production for this form of jewelry was located in one of those towns.

We turn now to plate torcs which are found on the lands of northeastern and northwestern Rus’, coming in two types: crescent-shaped, and hollow made from plate which has been bent into a tube.

Only nine crescent-shaped torcs have been uncovered. These were made from thin plate, tapered at the ends, and either loop-ended or fastened using a clasp. Of these nine torcs, none are identical. They differ from one another in their decoration and ends — only their general form is similar (Illustration 12, items 1, 3). Based on the burial complexes where these torcs were found, they date to the 11 century (Appendix II, a). Torcs made of plate which has been bent into a tube also come from this time, including one whose ends meet in a hinge. These torcs are divided into groups by the the complexity of their shields. The last torc has a massive rosette plaque with small loops on the other end, to the end of which is attached a hook from the end of another torc (Illustration 12, item 4.)

● – woven with soldered connections;

▼ – woven with plain terminals, made from round wire;

▽ – woven with “welded” terminals;

◇ – woven, with overlapping terminals;

U – Round wire with open terminals;

▭ – Round with with loop-shaped terminals;

ᐩ – Gabled-plate

▲ – Of smooth wire, triangular in cross-section

In the territory under study, 8 hollow torcs have been found in all, in the Belogostitskij trove from the 11th-early 12th centuries, and in grave sites from the 11th century (Appendix II, b).

The small number of finds of plate torcs suggests that they were not characteristic neck decorations for the peoples of northeastern and northwestern Rus’ and were not produced locally. As for hollow torcs, there is a theory that the center of their creation was in the Dnieper region, from whence they dispersed to all ends of medieval Rus’ and even beyond its borders.[29]Stenberger, op. cit., p. 94.

As opposed to the twisted and plate torcs described above, which appear to have been imported, wire torcs, common among the rural population primarily in the 11th century, appear to have been items of local production. Amongst these, there are two types: made from solid round wire narrowing to blunt-pointed, open ends (Illustration 8, item 2), and made from fine wire with ends that are tied or bent into a loop (Illustration 8, items 1 and 3).

Torcs of the first type were most often made of copper or bronze wire. Only in two burial mounds (near the hill-fort of Petushka, Vladimir region, and the village of Ljudkovo, Brjansk region) were torcs found made from pewter. Torcs made from solid round wire are found in digs less frequently than are those made from fine wire. They have been found only in 13 locations (14 examples), whereas torcs made from fine wire have been in 27 locations, totalling 39 examples.

Mapping the finds of fine-wire torcs showed that they were ubiquitous among the rural population of the lands under our study (Illustration 6). They were typically found in burials; they were found in cremations only in in the Ladoga region.

The production of fine-wire torcs was done by rural artisans, who we know to have been familiar with the technology of creating wire.[30]Rybakov, B.A. Remeslo drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1948, pp. 161-162. This type of torc was also made from non-ferrous metals, as well as from iron. They were mostly worn as a simple rod, from which beads and various amulets could be hung. This intended use is shown by finds of fine-wire torcs strung with glass beads and decorated with round shields, coin-shaped pendants, and bells (Appendix III, b). On the ends of torcs from burial mounds near the villages of Zagor’e (Kalinin region) and Kolchino (Kaluga region), wax rings were found (Illustration 8, item 1). It appears that these were strung onto the torcs to ensure that the beads sat tightly together and did not bang against one another.

Sometimes, fine-wire torcs also served as frameworks, which were then completely covered in fine wire weave or wrapped in thin metallic bands. This use is seen from torcs found in Staraja Ladoga and burial mounds from the Moscow (villages of Vladychino, Grigorevka, Obukhovo, Odintsovo, Rassokha, Cherkizovo) and Pskov (near Ostenets Island) regions.

Our review ends with an overview of plaited torcs, which represent the largest group of torcs. In northwest and northeast Rus’, 213 examples have been found, representing half of all torcs found. Of these, 63 examples are not included in our review of the various types of torcs, as their forms are not entirely clear; they were either found in fragments, or exist in archival materials and in the literature without a precise description.

The same picture is also found in the other countries of Europe. In Sweden, Denmark, Finland, northern Germany, the British Isles, and in Hungary, twisted torcs clearly prevailed over all other types.[31]Stenberger, op. cit., pp. 83, 90; Strömberg, M. Untersuchungen zur jüngeren Eisenzeit in Schonen. Vol. I. Lund, 1961, p. 158; Kivikoski, op. cit., Vol II., p. 6, Table 84, item 676. The production of plaited torcs was particularly developed in Sweden. We should note that Scandinavian scholars came to the conclusion that the technique of plaiting, as well as this type of torc, was borrowed by Scandinavian artisans from southern Rus’ in the late 9th or early 10th century in a period of development of economic and cultural ties between Eastern and Northern Europe.[32]Stenberger, op. cit., pp. 87-90.

In Rus’, the bulk of plaited torcs were made of bronze or copper wire that was round, or less frequently, square in cross-section. Sometimes billon wire was used.

The number of wires from which these torcs were woven varies greatly. Torcs exist which are a simple cable made from 2-3 strands, and there some that are more complex, e.g., woven from several twisted cables. There are also torcs made from simple or complex cables which are then additionally interwoven with filament.

The clasps of plaited torcs and the form of their terminals are also extremely varied. There are torcs with overlapping ends, completed with loops or heads of various types, torcs with round-wire or forged plate terminals and fasteners in the form of two hooks, or a hook and a loop. Finally, there are torcs with plate terminals which are welded or soldered to the wire base, and with clasps in the form of spirally-twisted loops.

Plaiting of torcs became known in the studied lands in the late 10th-early 11th centuries. The earliest torcs had looped ends. They were made of wire that was folded over thrice, then twisted together. This can be seen easily on a torc found near the village of Tushino (Illustration 13, item 3), the ends of which consist of loops and one free end of wire, that is, they are made in exactly the same way as woven three-strand bracelets, which were in widespread use in Rus’ in the 11th-12th centuries. Examples are also found where the free end of the wire was bent twice around the end of the twisted part of the torc. In medieval Rus’, this type of torc was uncommon. Only 5 examples have been found, from burials and cremations from the late 10th-early 11th centuries (Appendix IV, a). Beyond the borders of the areas under our study, similar torcs have been found in Belarus, the Baltic region, Hungary, and in Gotland, in graves and troves from the 10th-11th centuries. These torcs were particularly common in Finland, where more than 60 examples have been found, primarily from the 10th-11th centuries.

From around the same time period come torcs of simple braid with overlapping ends, tipped with shields in the form of polyhedrons, cones or large rosettes (Illustration 13, item 7). They were worn such that the shields laid on either side of the neck. These torcs, judging by the fact that they have been discovered together with 10th century dirhams, pear-shaped bells with cross-shaped and linear openings, and gold- and silver-foil beads, and bipyramidal carnelian beads, existed in Rus’ in the 11th century (Appendix IV, b). Analogous torcs from the Kama region date to roughly the same time.

Mapping the finds of this type of plaited torc showed that they were common almost exclusively in the southern and southeastern portions of the territory under study. From 8 locations (13 examples) where these torcs were found, 6 (11 examples) were located near Chernigov or adjacent lands near Smolensk and Rjazan’ (Illustration 11).

The population of Vladimir-Suzdal’ and Novgorod in the 11th century wore torcs of a different type, plaited from round wire or forged, flattened ends (Illustration 13, items 2 and 5). As with others, these were made from a simple braid woven from 2 or, more frequently, 3 strands. One of the wires in this bundle would serve as the end and the others were wrapped around it several times; or, the ends were cut off, and were wrapped with a thin metal wire or ribbon (Illustration 13, item 1). The clasp for this type of torc was either a pair of hooks, or loops which either hooked onto one another or were tied together with a cord. Sometimes, torcs are found ending in a hook and loop. It is worth noting that torcs with forged ends were typically made from heavier wire than those with round-wire ends. Smooth, forged ends were, as a rule, decorated. Among torcs of this type, there are also examples that are intertwined with filament (Illustration 13, items 1 and 4).

The torcs described above were widely distributed in Rus’. They have been found in 49 locations, numbering 60 examples. These were in use among the medieval Rus’ population from the 11th-early 12th centuries,[33]Individual exceptions are found in grave sites from the second half of the 12th century, for example, in burial mound #5 near the village of Malaja Kamenka near Pskov. when they were replaced by torcs plaited from plain or, more often, complex bundles with narrow flat ends. The ends of these torcs were fused together, then forged into a flat end (Illustration 13, item 8). If the twisted torcs mentioned above can be hypothesized to have been produced by rural artisans, then these plaited torcs, which were created using complex technical methods like fusing, would appear to have been the product of urban artisans. The technique of fusing was already known in the Dnieper region by the 11th century, from whence, it seems, it was adopted by artisans of northwest and northeast Rus’.

In the lands we studied, torcs with flattened, fused ends appear in the late 11th century, but they were most widespread in the 12th century. Only in one instance was a similar torc found together with three-lobed temple rings typical of the 13th century (near the village of Nikonovo, Moscow region). This type of torc has been found in 31 locations, for a total of 47 examples.

In the 12th century, there appeared one more variation of the plaited torc, where the flattened, wide tip is bent around the twisted part of the torc and is soldered to it (using a powder of easily-fusible material) (Illustration 13, item 6). The appearance of torcs with soldered terminals was most likely tied to the artisans’ effort to switch to a more effective technique in relation to the transition from custom work to mass production.

In northeastern and northwestern Rus’, torcs with soldered ends have been found in 20 locations, for a total of 25 examples. Of these, only 2 were made from plain bundles. The rest were made from several bundles of doubled wire. It is curious to note moreover that out of 5 torcs from the outskirts of Moscow, one had soldered ends, and a second was forged.[34]Similar torcs were found near the villages of Gorki, Kazanskoe, Rozhdestveno, Tushino, and in the Moscow Kremlin. Among the torcs of these last two types, the most common form of clasp was spirally-rounded loops, which were tied together with a cord.

Among both the torcs with soldered ends, as well as torcs with ends that were forged together, examples have been found wrapped with wire.

Aside from the torcs described above, in northwest and northeast Rus’ there are also individual examples found of torcs woven from thin wire, as well as pseudo-twisted[35]jeb: This term refers to items which look like twisted or plaited torcs, but which were actually cast, possibly using a plaited torc to create the mold. torcs, which however seem to have been uncommon for this territory.

As a result of this work, we have come to the conclusion that in Rus’ from the 10th-early 13th centuries, the torcs described here typically belonged to female decoration[36]In the Odintsovo burial mounds (Moscow region), a torc was found, according to the author of the dig, in a male grave (Veksler, A.G. “Semiverkhie kurgany vjatichej v Odintsove pod Moskvoj.” Tezisy dokladov sektsii slavjano-russkoj arkheologii plenuma Instituta arkhelogii. 1966). So far as we are aware, this was the only case where a torc was found on Russian territory outside of a female gravesite., and in burial mounds of that time, they appear as symbols of wealthy individuals. In the 10th-11th centuries, they were both imported, as well as produced locally. Later, primarily in the late 11th-early 13th centuries, imported torcs almost completely disappear from the archeological record. At the same time, amongst torcs of local production, the proportion created by urban jewelers rises sharply.

Appendices

[jeb: There are a series of tables indicating the provenance for each of the items in the illustrations, items found in the same locations used for dating, and analogous items found elsewhere in Rus’ or in Europe. References for each are given, in many cases duplicating references already footnoted above. As this is mostly lists and bibliographic data, I’m translating the tables here. The tables can be seen by accessing the original article here: https://www.twirpx.com/file/2508922/.]

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Korzukhina, G.F. Russkie klady IX-XIII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1954, pp. 62-63. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Torcs were found in pairs in 10 graves: near the villages of Ol’gii Krest (burial mounds 1 and 7), Shakhnogo, and Vakhrushego in the Leningrad region (Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, No. 29, p. 61; No. 18, pp. 38, 131); in Odintsovo in the Moscow region (burial mound 46, archive of the Institute of Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, R-1/2182); in Vlazovichi (burial mounds 25, 26, 41) and Kazarichi in the Brjanskaja region (burial mound 63, State Historical Museum, inventory No. 32884), and Dudenevo in the Kalinin region (burial mound 10, Izvestija Arkheologicheskoj komissii, 1904 (6), p. 10). |

| ↟3 | In the Baltic region in the 10th-13th centuries, torcs also were common forms of jewelry (Nukshinskij burial ground, p. 35; Materialy po arkheologii Rossii, No. 14, p. 26). Torcs are characteristic of female burials in 9th-10th century Mordovians and Muroms (Alikhova, A.E. “Iz istorii mordvy kontsa I – nachala II tys. n.e.” Is drevnej i srednevekovoj istorii mordovskogo naroda. Saransk, 1959). |

| ↟4 | State Historical Museum, inventory no. 28607. |

| ↟5 | Tumovskoe village, Vladimir region; Gorjunova, E.I. Etnicheskaja istorija Volgo-Okskogo mezhdurech’ja. Moscow, 1961, pp. 163, 175, Illus 78, items 15, 16. |

| ↟6 | In burial mounds near the towns of Vikhmes, Gorodische, Karlukha, Kashiko, Kostino, Pod’el’e, Shakhnogo, and Jarovshina in the Leningrad region, and near Polezhanki in the Smolensk region. |

| ↟7 | Petersen, Ja. Jaroslavskoe Povolzh’e X-XII vv. Moscow, 1963, p. 82. |

| ↟8 | Ocherki po istorii russkoj derevni X-XIII vv. Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja, 1959 (33), pp. v, 1, 13, 22. |

| ↟9 | Salmo, H. Finnische Hufeisenfibeln. Helsinki, 1956, pp. 28, 38, 50. |

| ↟10 | Stenberger, M. Die Schatzfunde Gotlands der Wikingerzeit. Vol. 1. Uppsala, 1958, p. 125; Kivikoski, E. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands. Vol. 1. Helsinki, 1947, p. 48. |

| ↟11 | Torcs with heads covered with spikes or protrusions were found near the villages of Mandrogi, Kashino, Pod’el’e, Shanginichi (in two burial mounds), and Jarovschina in the Leningrad region. |

| ↟12 | Ryndina, N.V. “Tekhnologia proizvodstva novgorodskikh juvelirov.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii SSSR. 1963 (117), p.232. |

| ↟13 | jeb: See my translation of this article here: https://rezansky.com/2020/01/jewelry-production-technology-in-10th-15th-century-novgorod/ |

| ↟14 | Kivikoski, E. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands. Vol. II. Helsinki, 1951, p. 6, Table 83, item 675. |

| ↟15 | Iron torcs were found in burials in the following locations: near the village of Dudino in the Volgograd region; near the villages of Zaozer’e, Il’ino, Krjuchkovo, and Nikol’skoe in the Leningrad region; in Beseda, Kon’kovo, Tagan’kovo, and Cherkizovo in the Moscow region; near the village of Khreple in the Novgorod region; near the villages of Timerovo (burial mound 375), Krivets, and in a barren of Plav’ in the Jaroslav region. |

| ↟16 | Paulsen, P. Axt und Kreuz in Nord und Osteuropa. Bonn, 1956, p. 205; Kivikoski, E. “Kvarnbacken.” Ein Gräberfeld der jüngeren Eisenzeit auf Åland. Helsinki, 1963, p. 84. |

| ↟17 | Birka, tables. |

| ↟18 | jeb: I was unable to locate the original reference this refers to. |

| ↟19 | Paulsen, op. cit., pp. 205-206. |

| ↟20 | Birka, burials 385, 854, 1151, 1158. |

| ↟21 | Paulsen, op. cit., pp. 219-221; Stenberger, op. cit., p. 167. |

| ↟22 | For example, mound 375 from the Timerovo burial ground. |

| ↟23 | Rybakov, B.A. Radzimichy. Pratsy, III. Minsk, 1932, p. 90. |

| ↟24 | Shnore, E.D., Zaids, T. “Nukshinskij mogil’nik.” Materialy i issledovania po arkheologii Latvijskoj SSR. 1957 (1), pp. 27-29. |

| ↟25 | State Historical Museum, inventory no. 43891. |

| ↟26 | Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi XI-XIII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1936, Table VIII, item 1; Korzukhina, op. cit., pp, 97-98. |

| ↟27 | Zapiski otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva.Vol. IX. St. Petersburg, 1913, p. 261, Illustration 29, item 2. |

| ↟28 | Avdusina, G.A. “Tri kurgany gruppy u Zvenigoroda.” Istoriko-arkheologicheskij sbornik MGU. Moscow, 1962, pp. 278-280; Rybakov, B.A. “Produktsia russkikh remeslennikov v X-XIII vv.” Uchenye zapiski MGU. 1947 (93), Illustrations 4-6. |

| ↟29 | Stenberger, op. cit., p. 94. |

| ↟30 | Rybakov, B.A. Remeslo drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1948, pp. 161-162. |

| ↟31 | Stenberger, op. cit., pp. 83, 90; Strömberg, M. Untersuchungen zur jüngeren Eisenzeit in Schonen. Vol. I. Lund, 1961, p. 158; Kivikoski, op. cit., Vol II., p. 6, Table 84, item 676. |

| ↟32 | Stenberger, op. cit., pp. 87-90. |

| ↟33 | Individual exceptions are found in grave sites from the second half of the 12th century, for example, in burial mound #5 near the village of Malaja Kamenka near Pskov. |

| ↟34 | Similar torcs were found near the villages of Gorki, Kazanskoe, Rozhdestveno, Tushino, and in the Moscow Kremlin. |

| ↟35 | jeb: This term refers to items which look like twisted or plaited torcs, but which were actually cast, possibly using a plaited torc to create the mold. |

| ↟36 | In the Odintsovo burial mounds (Moscow region), a torc was found, according to the author of the dig, in a male grave (Veksler, A.G. “Semiverkhie kurgany vjatichej v Odintsove pod Moskvoj.” Tezisy dokladov sektsii slavjano-russkoj arkheologii plenuma Instituta arkhelogii. 1966). So far as we are aware, this was the only case where a torc was found on Russian territory outside of a female gravesite. |