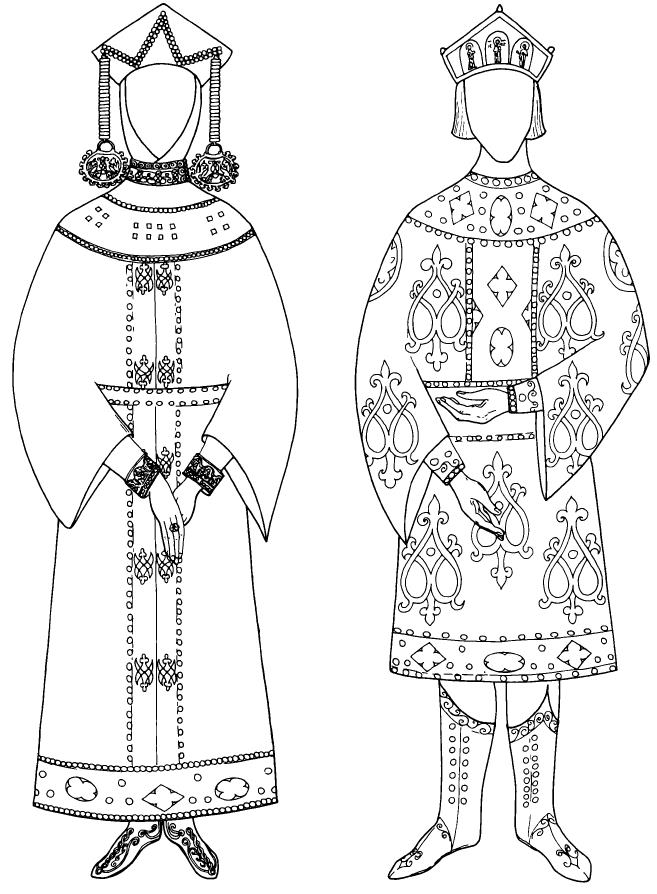

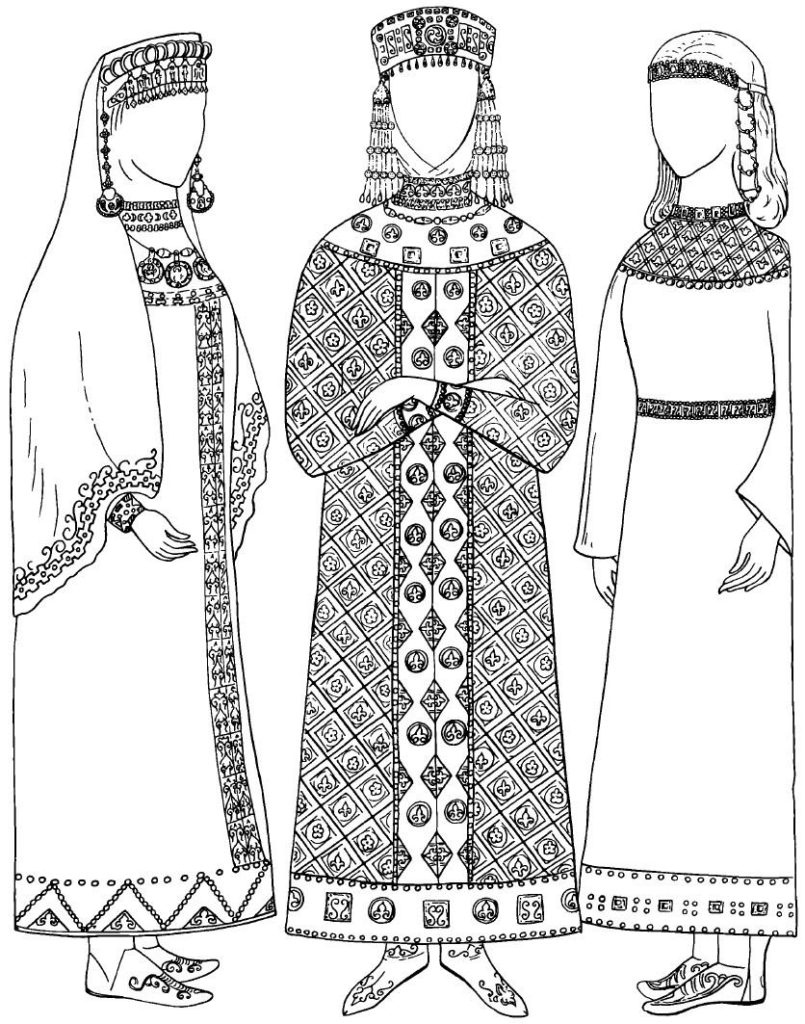

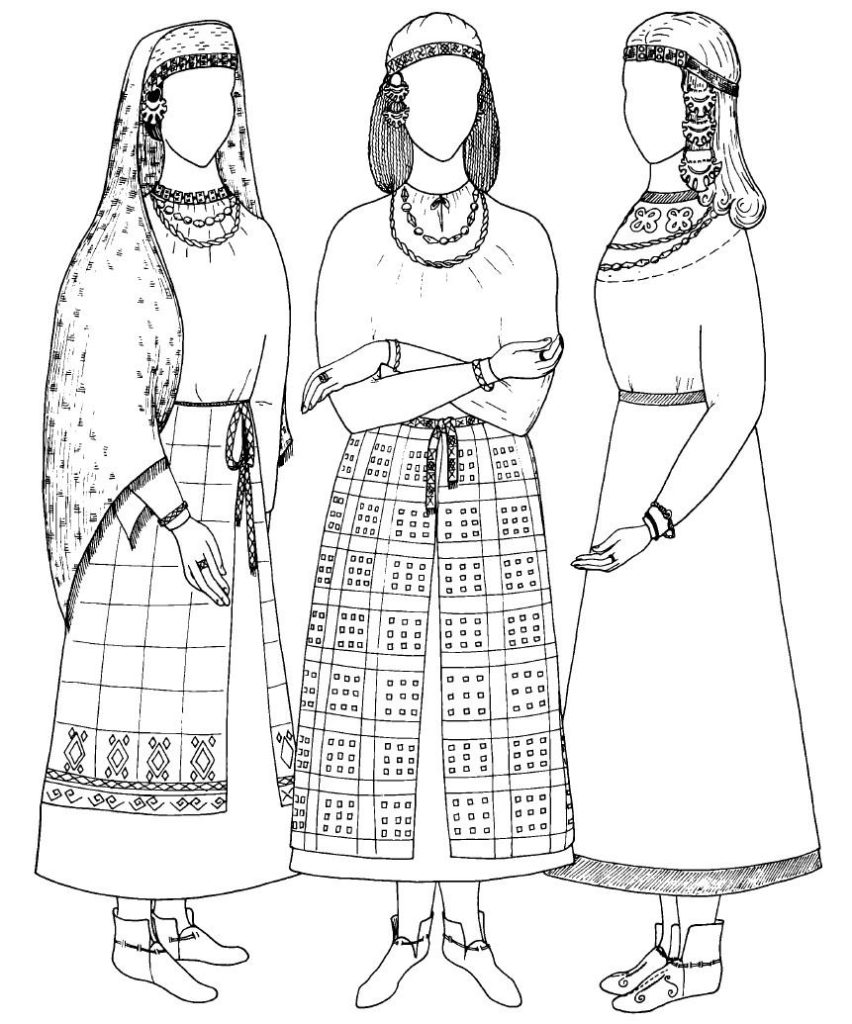

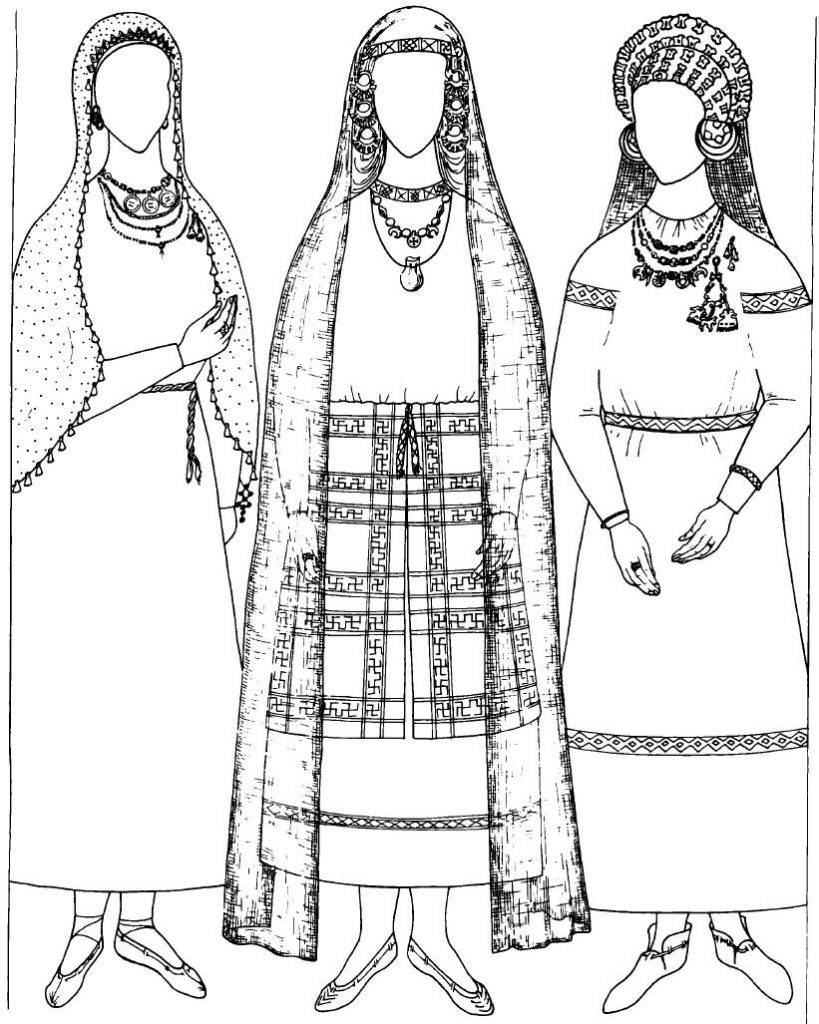

I recently finished reading and translating an article by M.A. Saburova on medieval Russian garb. This article, published in 1997, provides an excellent overview of literature which had been written up to that date, and a collection of materials from a multitude of sources and various archeological finds. It also provides some very interesting and well-done drawings reconstructing that medieval Russian garb in the pre-Mongol period may have looked like, based on archeological excavations and 19th-20th century ethnographic studies. This is a great resource about the fabric, clothing, jewelry, embroidery, and footwear from various regions in medieval Rus’. And it has so many references to what appear to be interesting works! Goldmine! Be sure to look at the drawings at the end of the post.

Medieval Russian Garb

A translation of Сабурова, М.А. «Древнерусский костюм.» Древняя Русь. Быт и культура. Москва, 1997, с. 93-109. / Saburova, M.A. “Drevnerusskij kostjum.” Drevnjaja Rus’. Byt i kul’tura. Moscow, 1997, pp. 93-109. (“Medieval Russian Costume.” Medieval Rus’: Everyday Life and Culture.)

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.archaeolog.ru/media/books_arch_ussr/ArchaeologyUSSR_16.pdf. ]

Clothing

Overview of Previous Scholarly Literature

As an ensemble, medieval Russian clothing, consisting of sewn clothing, head wear and shoes, has been insufficiently studied by scientific literature to date. The level of study varies for its various components. Until recently, in order to reconstruct clothing, scholars turned to frescoes, illuminations, and written works, using them as basic sources (Artsikhovskij, A.V., 1945, p. 34; 1948a, pp. 234-262; 1969, pp. 277-296; Levashova, V.P., 1966, pp. 112-119).

This approach and the poor state of preservation of items in archeological finds caused a fragmentation of the details of clothing. It’s researchers, however, repeatedly expressed the opinion that the clothing represented on items of medieval Russian art was conditional and subordinate to iconographic templates and carried little information about the actual clothing which was worn in medieval Rus’. They noted that for exhaustive study, it would be necessary to include archeological data (Artsikhovskij, A.V., 1948a, p. 362; 1969, p. 192).

Even in the previous century, specialists in the area of everyday life in the history of Rus’ paid particular attention to the terminology of medieval clothing. Certain forms of clothing were compared to costume from earlier epochs and to 19th-century folk attire. This comparative method was developed, thanks to which broad ethno-cultural juxtapositions became possible (Olenin, A.N., 1832, p. 31; Zabelin, I., 1843, No. 25., pp. 319-323; No. 26, pp. 327-333; No. 27, pp. 341-344; 1862; 1869; Prokhorov, V.A., 1875; 1881). In 1877, an album illustrating medieval Russian clothing was published, which summed up all the knowledge collected by scientists and artists in the 19th century (Strekalov, S., 1877).

This approach to the study of medieval Russian clothing was possible due to the level of archeological data. As is known, excavations in the field of Slavic archeology became widespread only in the second half of the 19th century. For the first time, they produced a massive inventory of burial mound finds from the 10th-13th centuries, including significant numbers of fragments from clothing. However, the lack of methods for restoration and conservation led to great difficulties when working with these small fragments. Archeological documentation suffered from one general disadvantage: the constructive coherence of clothing details in burials was reflected in the notes verbally, rather than graphically. This lack of drawings did not convey the proper information about the shape and details of the clothing finds.

Scholars understood that the material from these excavations would allow them to fully and accurately imagine the Slav’s everyday life, in particular their clothing, unlike the fragmentary data from written sources; as a result, the latter was used only as supporting evidence (Prokhorov, V.A., 1881, p. 37).

In the late 19th century, Russian science had at hand a significant number of buried treasure troves, as described by the expert on Russian and Byzantine art, N.P. Kondakov (Kondakov, N.P., 1896, Vol. I.) Possessed of extraordinary erudition, he introduced into scientific circulation a maximum of comparative material, both for items of jewelry (which are known from these treasure troves), as well as clothing, known from frescoes (Kondakov, N.P., 1888) and illuminated miniatures (Kondakov, N.P. , 1906). Kondakov attributed the majority of forms of headwear and clothing from the post-Mongol period to the epoch of Medieval Rus’, assuming that they were borrowed from Byzantium (idem., p. 87). He didn’t give much importance to the possibility of convergent forms of clothing which could have led to new, changed forms of clothing. Aside from the origin of specific categories of items, Kondakov was interested in their purpose, construction, and the particulars of how they were worn.

Unlike the 19th and early-20th century historian/scholars who studied medieval Russian clothing, primarily from the upper classes of society, archeologists had interested themselves since the turn of the century with the culture of wide layers of society. The first scholar to study burial ground material was A.A. Spitsyn, who singled out characteristic collections of items and temple rings which were qualifying ethic signals for various Slavic tribes (Spitsyn, A.A., 1899, pp. 301-340; 1895, pp. 177-188).

As early as the 19th century, there was a hypothesis in the scientific literature that Slavic dress of the 19th century preserved the cut of medieval clothing (Golovatskij, Ja.O., 1868, pp. 4-5). One of the first works on ethnography which widely made use of archeological data for the history of clothing was “The Ukrainian Peoples, Past and Present” (Volkov, F., 1916). Aside from archeological material, this author included terminology related to manuscripts in his study, showing the presence of analogous names and forms of clothing in both antiquity and in the 19th century.

After 1917, the view of peasant art changed dramatically, and V.S. Voronov put forth the idea that peasant art contains “series of successive layers” which lead back to pagan times (Voronov, V.S., 1924, p. 30).

B.A. Kuftin, further developing Voronov’s theory, turned his attention to “archaisms” in Russian dress which, in his opinion, could be understood and explained using material from medieval Rus’ (Kuftin, B.A., 1926, p. 92).

Around the same time, D.K. Zelenin formulated his approach to the study of Eastern Slavic women’s headwear (Zelenin, D.K., 1926, pp. 303-556). His study was based on a retrospective method, which proposed a detailed classification of all the material collected up to that date about headdresses. The author revealed the presence of general characteristics in all of the varied forms of headdress through the existence of similar forms as early as medieval Rus’ and the singular line of their development. Later, he returned to these questions in order to show a cultural unity of all Western Slavs (Zelenin, D.K, 1940, pp. 23-32). Unlike other scholars of the history of clothing, Zelenin recognized that there was a convergence in the development of forms of headdress and felt that similar forms could arise among different peoples independent of one another.

No less relevant in those tames was the work by N.I. Lebedeva, who described and compared the national Russian costume with those of Belarus and Ukraine (Lebedeva, N.I., 1927). She also highlighted the archaic features of costume among the southern great Russians (Lebedeva, N.I., 1929).

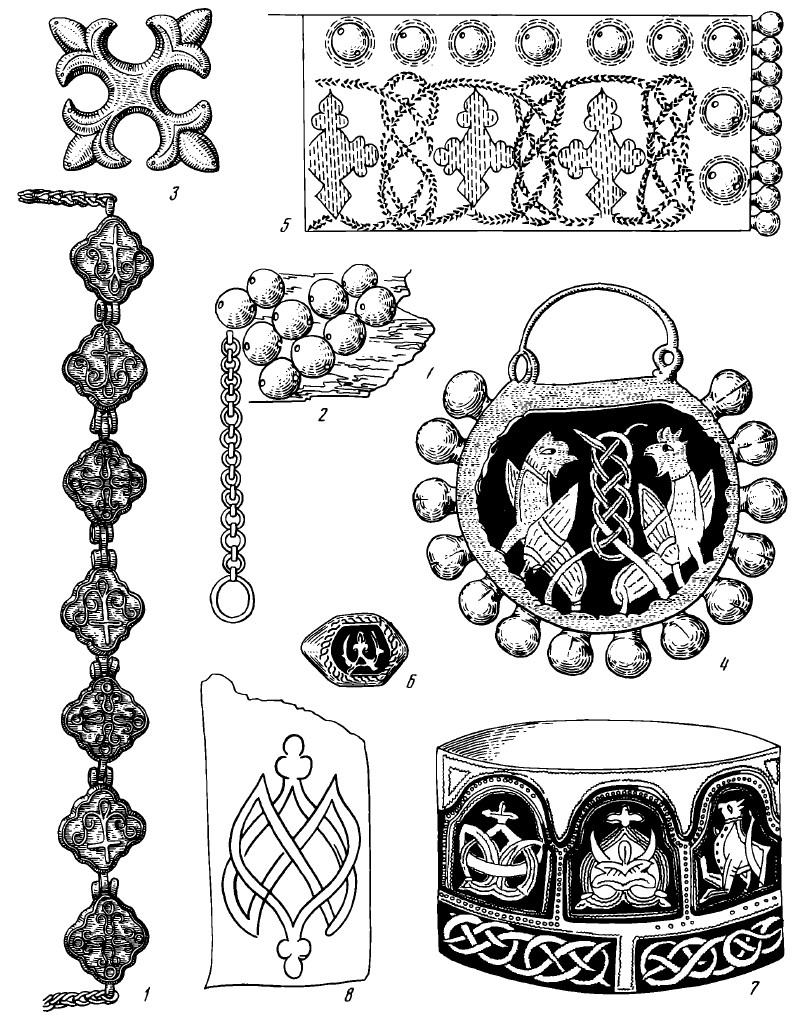

The unfolding excavations of medieval Russian cities expanded the circle of archeological sources, and provided the ability to once again illuminate questions around medieval Russian clothing. B.A. Rybakov paid special attention to the ways in which various types of jewelry were worn, including temple rings (Rybakov, B.A, 1948, pp. 337-338) and kolts (Rybakov, B.A., 1948, pp. 316-317, 332-383; 1940, p. 251; 1949, pp. 57-58, illus. 23, 25). He returned several times in many works to the reconstruction of headdresses made up of miniature icons (Rybakov, B.A., 1971, p. 35).

While investigating the Chernigov burial mounds, B.A. Rybakov turned his attention to the dating of grave finds, including clothing (Rybakov, B.A., 1949, pp. 19-21, illus. 4). These data, alongside evidence from the Chronicles about medieval burial outfits (Rybakov, B.A., 1948, p. 141) shed light on the essences of these rites and the character of the clothing and jewelry found in burials.

G.F. Korzukhina analyzed all known treasure troves and systematized them by their chronological attributes, allowing her to distinguish a stylistically uniform headdress from the jewelry items found within them. In her work, Korzukhina also looked at the question of how various forms of jewelry were worn, drawing upon a whole range of sources, and paying particular attention to terminology (Korzukhina, G.F., 1954, pp. 51-62). While characterizing the jewelry arts of the 13th century, she followed Rybakov in tracing its development in breadth, to the national environment which was expressed in the creation of inexpensive jewelry which imitated the gold and silver jewelry of the upper classes (Korzukhina, G.F., 1950, p. 233).

A.V. Artsikovskij remained interested in medieval Russian clothing throughout the course of his scientific studies. In his work The Burial Mounds of the Vyatichi (Artsikovskij, A.V., 1930), he developed a typology and chronology for the metallic attire of the Vyatichi; afterwards, he repeatedly returned to the topic of Vyatichi tribal dress (Artsikovskij, A.V., 1930, p. 110; 1947, pp. 80-81). In each of his works, whether dedicated to clothing (Artsikovskij, A.V., 1945, p. 34; 1948a, p. 234; 1969, p. 277) or some other topic (Artsikovskij, A.V., 1930, p. 101; 1947, pp. 17-18), he summed up the archeological knowledge with maximum attention to written sources and evidence from monuments of pictorial art.

In recent years, a new stage in the study of medieval Russian clothing has emerged, associated with both the continual replenishment of archeological finds, as well as with the level of development of related historical disciplines. Particular importance has been tied to the restoration of archeological monuments, returning items from excavations to their original appearance and revealing information about the technology of fabrics, leather, dyeing methods, embroidery, the character of fashion, etc.

A great achievement by ethnographers of recent years was the publication of a historical-ethnographical atlas, which displays various types of clothing on a map (Istoriko-etnographicheskij atlas, Vol. I, 1967; Vol. II, 1970). Evidence from written sources about clothing involving archeological material was summarized in the collection Medieval Clothing of the Peoples of Eastern Europe (Drevnjaja odezhda…, 1986).

Within the sphere of historical lexicography, lexemes associated with thematic groups of words related to clothing, shoes and jewelry are being studied (Berkovich, T.I, 1981; Lukina, G.N., 1974, pp. 246-262; 1970, pp. 100-102, et.al.; Vakhros, I.S., 1959). Archeologists are attempting to use finds of parts of clothing in order to recreate them, however, even collars, sleeves, belts, trim, and similar parts of clothing are preserved only in fragments. Archeologists are able to use these items for their reconstructions only after the work of restorators. It is logical to present factual information about the clothing of medieval Rus’ in the following order: first, the fabrics and details of outfits, then their parts (headdress, clothing, shoes), and finally, the reconstruction of entire outfits.

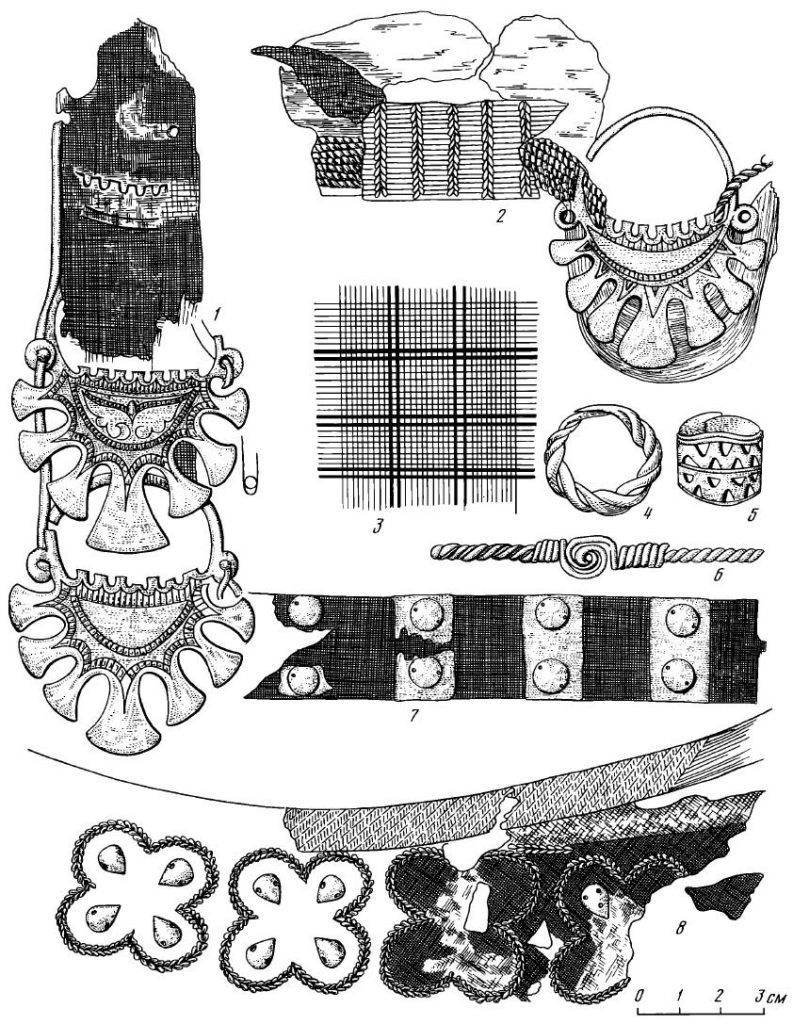

Fabric

Finds from the layers of medieval Russian cities, tombs, and village burial sites tell of the diversity of locally produced fabrics used to make clothing. This included wool fabric woven primarily from sheep wool, as well as fabric woven from various plant fibers (linen, hemp). Among wool and wool-blend fabric, we find checkered and striped fabrics. On wool fabric, we find embroidery with a bran’ design (Rus. браная техника, branaja tekhnika)[1]jeb: see Savvaitov, P. Starinnykh russkikh utvarej, odezhd, oruzhija, ratnykh dospekhov i konskogo pribora, v azbuchnom porjadke raspolozhennoe. St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 16: “Bran‘ or Branina: a patterned fabric in which the warp threads are lifted by a special means to create a desired pattern. It is used for trimmings, tablecloths, curtains, etc. Branyj, an item sewn from this fabric” (jeb: translation mine). Patterned fabrics are also known. Typical finds for the 10th-12th centuries are patterned or single-color bands, braid, laces, and fringe made from wool yarn (Klejn, V.K., 1926; Nakhlik, A., 1963, pp. 228-313; Shmidt, E.A., 1957, pp. 184-280; Levinson-Nechaeva, M.N., 1959, pp. 9-37; Levashova, V.P., 1966, pp. 112-119). Cloth (Levashova, V.P., 1966, p. 114) and other items made of felt (Levashova, V.P., 1959b, pp. 52-54) were widely used. Some fabrics were woven from wool in its natural brown, black, or other colors, while others were dyed using organic dyes such as cochineal or black walnuts. Mineral dyes were also used, including ocher, red iron oxide, etc. (Levashova, V.P., 1959b, pp. 96-102). In addition, clothing was sewn from thin woolen cloth imported from Western Europe (Nakhlik, A., 1963, pp. 270-274), as well as from silk and brocade fabric and gold-thread bands from the Mediterranean, Byzantium, and the Middle East (Klejn, V.K., 1926; Rzhiga, V.F., 1932, pp. 339-417; Fekhner, M.V., 1971, pp. 207, 226-227; 1980, pp. 124-129).

A special group is made up of fabric embroidered using metallic (gold and silver) threads by medieval Russian artisans. We know from written sources that as early as the 11th century, monasteries contained “schools,” and in royal circles there were “household workshops,” where the technique of goldwork embroidery was taught (Novitskaja, M.A., 1965, p. 26). It has been established that in various regions of Rus’, specific weaves prevailed (Levinson-Nechaeva, M.N., 1959, p. 21). For example, in Vyatichi burial mounds, we most commonly find wool-blend and wool checkered fabrics woven from threads of different colors (Rus. пестрядь, pestrjad’). These were woven from wool threads dyed primarily red, green, dark blue, yellow, or black, as well as white plant-based threads. The weave patterns varied. We find checkered fabrics with “openwork” bands formed due to the removal of hempen threads (Levinson-Nechaeva, M.N., 1959, p. 25), as well as checkered fabrics with “openwork” bands formed during weaving. One of the specimens of this kind of fabric was embroidered using a thick needle, creating a meander embroidery design. In the same burial mounds, we also discovered smooth, plain-weave woolen fabric with embroidery created using an additional weft, the bran’ (Rus. браная) technique. The pattern was preserved as chains of red diamonds against a dark background. The same mounds also revealed many decorated bands used for trimming clothing, as belts, and for fastening jewelry. They also revealed remains of broadcloth and diagonal fabrics, under which thin plain weave (linen?) fabric was placed during the burial.

In the Kharlapovo burial ground, used by the Krivichi trive, a multitude of fabrics was found – 54 examples. These did not include checkered fabrics (only one fragment was found near a headdress). As is known, in other Krivichi monuments there were individual fragments of checkered fabric found alongside bracelet-shaped temple rings. Nevertheless, it can be argued that this kind of fabric was almost never used in the funerary clothing of this particular burial ground. This burial ground also contained significantly fewer woolen decorated bands. As in the Vyatichi burial mounds, here too we see a profusion of woolen, monochromatic linen fabric. These were decorated with geometric patterns carried out using an additonal weft. Twill-woven fabrics, broadcloth and felt are predominant, found over the remains of a thin linen fabric.

As such, in Vyatichi and Krivichi weaving, we can trace several local variants. As we shall see below, these were complimented by local variations in clothing and headdress.

Headdress

In archeological finds from 10th-13th century burials and medieval Russian treasure troves, these are primarily represented by female headdress sets. Male headwear has been almost unknown. In recent years, new evidence has been collected by O.A. Brajchevs’kaja (Brajchevs’kaja, O.A., 1992).

In burials of females, headwear has been represented by fragments of textiles, including wool and silk fabric and very rarely fabrics made from threads of plant materials. Felt has been found, as well as remnants of undefinable organic origin (furs?). Often, twisted threads and fringe made from wool are also found, as well as various types of bands made of wool, silk, or cloth of gold. Aside from bands made from textiles, metallic bands made from silver, bronze and alloys have also been found.

Among the metallic details of headwear, a particular type has been found in the form of a metallic cord shaped like a hoop, with a loose end twisted into a tube. Metallic plaques, beads, and pearls have also been found, and details made of birch bark, oak, and leather were not uncommon.

An indispensable accessory to female headdress, as is well known, was temple rings. In some cases, remnants of hair have survived, giving hints about hairstyles.

All of this material in specific archeological finds comes across in certain combinations, characterizing the particulars of styling and various types of decorating headwear. Work in this area has consisted of the following factors: 1) restoration of the deteriorated details of headwear, and description of these items; 2) description of the location of these details in grave sites, primarily on the skull; 3) the association of structural elements which were found in a single burial site; 4) the systematization of material from burial sites into groups based on repeating details, and defining the construction and particulars of the found materials and their decoration, as well as how they were worn.

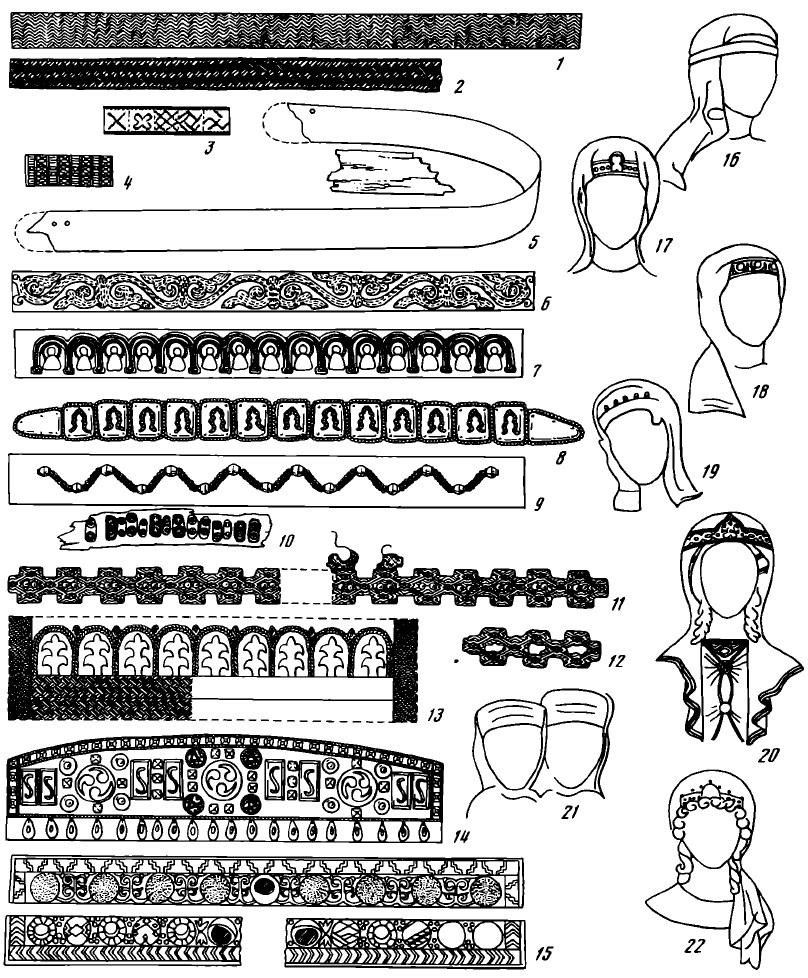

Keep in mind that all of these archeological finds are only details of unpreserved headwear. In order to imagine their complete form, it was necessary to turn to medieval examples of pictorial artwork, written sources, materials of later ethnography, and lexicological data. As a result of this integrated methodology, a typology of female headdress was created, based on its construction. This consists of three types: type I – headwear made up of unsewn fabric; type II – complex headwear comprising various details; and type III – headwear constructed from bands.

Type I

This group includes scarves and wimple-like items (plate 66, 16-22). In the 11th-14th centuries, these were referred to using terms such as plat, pokrov, and povoj (Rus. плат, покров, повой). All of these meant a piece of fabric used to cover or wrap something. In medieval Russian, they were also used to refer to headdress. The form of this headdress depended on the shape of the piece of fabric, or ubrus (Rus. убрус), a term which in the dialect of 19th-20th Eastern Slavs referred to a veil-like headdress. In medieval Russian, the term ubrus’ (Rus. убрусь) was used for both male and female headdress (Berkovich, T.A., 1981, pp. 22, 59; 1967, pp. 419-422[2]jeb: It’s unclear which work this is attempting to reference.; Sreznevskij, I.I., 1958, vol. II, p. 1001).

Type I headdress was made from various materials, and can be divided into three subtypes.

Subtype 1: Headdress made from wool and wool-blend fabrics. Wool kerchiefs were recorded and studied in Vyatichi burial mounds. Of interest among these is the fabric found in a female burial in the Volkov burial mound group in the Moscow region. This was a wool-blend, checkered fabric. The checkers were created using red, black, and yellow threads. In addition, inside the checkers there survived openwork stripes formed by the removal of threads of plant origin. This fabric was found near the temples, under a set of seven-bladed temple rings and a lamellar torque. The fabric’s location around the skull and chest speaks of its use as a veil. Analogous fabrics were found in the same burial mound group, in mounds #31 and 33, as well as in the burial mounds near Besed in the Tsaritsyn region near Moscow. These finds were dated to the early 12th-first half of the 13th centuries (Ravdina, T.V., 1968, pp. 136-142, illus. 1).

In 12 burials from the Vologda region burial mounds, checkered shawls were also found made from wool-blend, plain-weave fabric (Saburova, M.A., 1974, p. 94). It is interesting that in the 19th century, women in the Vologda province wore wool and wool-blend checkered shawls which were called a ponyava (Rus. понява), a term which was used in the 19th century for a skirt among the southern Great Russians, and meant an okhaben’ (a type of caftan) in the northern provinces of Russia (Dal’, V.I., 1956, Vol. III, p. 286). As a rule, in medieval written sources, the word ponyava indicates a fabric used for outerwear or which can be used to wrap up or cover something (PSRL, 1853, Vol. VI, p. 86; 1962, Vol. I., Iss. 2, p. 466).

Woolen shawls from the same time were not always checkered, but also could be patterned. Both were found in burial mounds from the Bityagov burial mound group in the Moscow region (Rozenfel’dt, R.L., 1973b, pp. 192-199). Shawls have also been found decorated with beads, plaques, and trapezoidal pendants in the Moscow, Smolensk, and Vologda regions (Saburova, M.A., 1974, p. 94).

In the northwestern regions of Rus’, wool veils are often found decorated with bronze spirals and rings (MAR, 1896, plate XVI, illus. 15-16 [3]jeb: It’s unclear which work this is attempting to reference. ). These are the so-called vilajne (Rus. вилайнэ) which were localized to regions adjacent to the lands of the Baltic and Balto-Finnish tribes. They were known to exist in this region as early as the 7th century, and continued to be used in some areas until the 19th century (Zarina, A.E., 1986, p. 178).

Subtype 2: Headwear made up of hemp [4]jeb: ?? – Rus. пасконный, paskonnyj >> посконный / poskonnyj) threads. This type can include sets woven from threads of vegetable fibers. They have almost never survived in the ground. Only in some cases have their remains been found in archeological finds. For example, in the Gomel’sk region of the Roslavl’ area, in the Vetochka IV burial mound group, fragments of linen plain-weave were found on the skull of a buried woman under seven-rayed temple rings and plaques, and near her right humerus. The headwear was decorated above the brow with a row of diamond-shaped pewter plaques. This burial mound was dated to the early 11th century (Solov’eva, G.F., 1967, pp. 10-13; 1966, p. 153).

Fabric made from vegetable fibers was better preserved on a female skull in a late 12th century burial unearthed in Minsk. This lightweight plain-weave fabric or ryadina (Rus. рядина) had a white color which was preserved (Tarasenko, V.P., 1950, pp. 127-128; 1957, p. 229). Under this fabric, her plaited hair which had been laid around her head, could be seen, along with a tall birch “circlet”(?). The headband was decorated with rectangular piece of embroidered silk fabric. Here too, a garland of flowers was preserved. Analogous fabric was used in the 19th-20th centuries especially for veils worn for weddings and burials. The Minsk Museum contains a veil or sarpanok (Rus. сарпанок) woven from hemp fibers. It has a very rare plain-weave structure, and is nearly 3 meters long. Similar veils were known among all eastern Slavs right up until the 20th century.

Subtype 3: Silk headwear. Medieval burials have sometimes preserved fragments of silk fabrics. For example, in the Moscow Kremlin, in a burial from the 13th century, a rich set of headwear was found which included a sheer silk, muslin-like veil called a fata (Rus. фата) (Sheljapina, N.S., 1973, p. 58).

Remains of fabric from faty are known from burials as well as medieval Russian treasure troves from the 12th-13th centuries (Fekhner, M.V., 1974, p. 69). They were made from diaphanous, lightweight, plain-weave fabric decorated with woven patterns, gold threads (Mikhaylovsky trove, 1903), or embroidered with gold fabric bands (Burial from Smolensk, 12th century, Church of St. John the Theologian; dig by I.I. Khozerov, 1924) (Plate 66, 11). They were typically died red or bright pink.

The term “fata” came to use from the lands of the East, where it indicated a particular type of silk fabric (Berkovich, T.L. 1981, p. 114). The centers of production for lightweight veils were Iranian cities (Pigulevskaja, N., 1956, p. 241). The fata was also known in the Russian literary language, as well as in 19th-20th century dialects. This word was used to mean elegant women’s shawls or bridal veils made from lightweight fabric.

Type II

Type II includes headwear consisting of a large number of details. It is obvious that these were not only built, but also sewn. The state of knowledge about this material allows us to divide them into three subtypes of complex headwear.

Subtype 1: Sewn headdress of rigid structure. For example, in a burial mound from the Besed burial mound group, a constructively-complete fragment of a headdress was preserved upon a female skull, under a set of temple rings. It consisted of a piece of bast (7.5 x 3.5 cm in size), upon which there was tightly affixed a woolen patterned band, 5 cm long and 2.3 cm wide. Between the bast and the band ran cords made from twisted wool threads. Oxides from metallic temple rings were preserved on these cords, and between the band and bast was a fragment of plain-weave wool fabric with a pattern carried out using the “bran’” (Rus. браная) technique. The fabric was greyish-brown, with a diamond-shaped checkerboard pattern created with red wool threads. Here too was found a fragment of the same fabric with bran’ decoration, 10 x 14 cm in size. It was cut out in the form of a triangle with rounded corners. Evidently, this was a woman’s headdress with a rigid base and an upper section sewn from fabric. The item was covered at the headband with a patterned band, under which ran wool cords from which the temple rings were suspended. The hair hidden by the headdress was, as it were, replaced by the “curls” of woolen cords. An analogous headdress was found in burial mound 28 from the Volkov burial mound group. It was created from dark woolen plain-weave fabric with a bran’ design in the form of diamonds and oblique crosses. The possible shape of this headdress can be judged by the height of the preserved bast base. Judging by depictions of headdress on works of small-form artwork from the 13th-14th centuries, their silhouette could rise above the brow and had a slightly expanding or rounded shape (Saburova, M.A., 1973[5]jeb: sic., see Saburova, 1978., pp. 32-35) (plate 66, 2).

Subtype 2: Composite headdress of soft construction. As an example of a headdress made up of a large number of independent pieces of soft construction, we might look at archeological sets with fringes from the Vyatichi burial mounds. They were found in five burial mounds in the Moscow region (Saburova, M.A., 1976a, pp. 127-132). To summarize the data from these excavated complexes, let us imagine the parts of these sets. This included fringe made from twisted wool threads, 20 cm long, which were attached to a band; patterned woolen bands, located on the forehead and tied around the head; and fragments of fabric (linen, wool, wool-blend) found on the skulls (under the bands and fringe, and over the band). The character of the included materials and the constructive elements of these sets were most similar to the headdress of southern Great Russians from the early 20th century called an “uvivok” (Rus. увивок) or a “maharam” (Rus. мохрам). These typically included various individual parts, created from various fabrics and fringes fastened to a band. Of interest is the coincidence of design on the bands from the archeological find and that on the band from a Tambov headdress with an uvivok: an oblique cross and rhombi (plate 66, 3). Young women also wore similar sets in the 19th-20th centuries. They were included in a set of clothing along with a paneva.

Subtype 3: Kokoshnik-style headdress, decorated with plaques. Among complex headdress, we know of sets which consisted of fabric, a stiff base (birch bark or bast) and pewter plaques. Their common form was that of a tall headdress in the shape of a “halo,” a kokoshnik with a rounded top. It was covered from top to bottom in plaques. Such headdresses were found in the Smolensk (Savin, N.I., 1930, Vol. II, pp. 225-226; Shmidt, E.A., 1957, p. 251) and Vologda regions (Saburova, M.A., 1974, p. 89).

Headdress of the same shape was worn in the 19th and 20th centuries in the central and northern regions of Russia. In the Russian Ethnographic Museum in St. Petersburg, one can see a birch bark base from a similar kokoshnik. It came from the Vologda province.

In the Kharlap burial ground in the Smolensk region, the construction of kokoshniki included bracelet-shaped temple rings, which were fastened to or superimposed over a circlet of birch bark. The diameter of these birch circlets repeated that of the temple rings. Studies have shown that along the edges of the birch circles there were small holes punched using a needle from when they were covered in red wool fabric. The rings were fastened to the headdress using leather straps. It is possible that the birch circlets were sewn to the rings or were simply “tucked in” beneath the headdress, as is known based on materials from later ethnography (Grankova[6]jeb: sic., see Grinkova., N.P., 1955, pp. 26-27).

The materials found in the Kharlap burial ground suggest that on either side of women’s headdress, they wore not only rings but also round “blades”, which are also known from 19th-20th century ethnographic materials (idem., pp. 24-27). In Moscow’s Museum of Folk Art, there is a headdress called a “horned krichka” (Rus. кричка рогатая). It has round blades sewn onto the firm base on either side of the headband. Their diameter is 7.5 cm. They are decorated with beads, plaques, and are united into a single composition with the headband by a band which is sewn around the blades and brow. We do not know whether the headdress from Kharlap described above is complete or partial. It is only possible to suppose that they might have included temple rings fastened to the blades and thrown over the top of the head with the assistance of straps. The Kharlap burial ground dates to the 11th-13th centuries.

Type III

Type III consists of headdress constructed from bands. These were round-shaped headdress made up of a strip of fabric, metal, plaques, and other materials which fastened the hair like the simplest of diadems or circlets (Rus. венок, венки).

The word “venъ” (Rus. венъ) and its decendants “wreath” (Rus. венок, venok), “crown” (Rus. венец, venets) and “coronet” (Rus. венчик, venchik) come from the proto-Slavic verb vit’ (Rus. вить, “to entwine”). As Berkovich has suggested, the original meaning of the medieval Russian word venok (wreath) was a young girl’s headdress (Berkovich, T.L., 1981, p. 15).

The word venets (crown) had a wider meaning, indicating also the headdress worn during coronations and weddings (idem., pp. 10-20). The word venets was a translation of the ancient Greek word “diadem”, a headband. In addition, the word venets was used in 15th-16th century royal life (Zabelin, I., 1901, p. 360; Dukhovnye gramoty, gr. 1486), and then in folk life from the 18th-20th centuries (Dal’, V.I., 1863-1866, Vol. I, p. 282; Filin, F.M., 1965-1980, Iss. 4, pp. 111-112; Opredelitel’, 1971, pp. 63, 192) to refer to headdress of various forms, most commonly on a stiffened base.

V.P. Levashova’s work presents several variants of headdress constructed from bands. She divided them up according to the material highlighted from the entire variety of forms from the 10th-13th centuries which were characteristic for the Slavic ethos of medieval Rus’ (Levashova, V.P., 1968, pp. 91-97).

Finds from recent years have significantly enriched our understanding of this area. Today we are able to divide band-type headdress into no fewer than 8 subtypes based on the material from which they are constructed.

Subtype 1 consists of crowns in the form of metallic bands. Sheetmetal crowns in the form of metallic bands are known from all of the lands of medieval Rus’. Several finds, as Levashova writes, have a stiffened base or are “sewn onto the band” (idem., p. 92; Uvarov, A.S., 1871, p. 160). For example, in the Kalinin region, a silver crown was discovered in the form of a band with holes on the ends. Beneath it ran a band of birch bark (Uspenskaja, A.V., 1972, p. 180) (Plate 66, 5). Combined with metallic crowns, in the Kursk region, crowns of a unique type were found, in the form of a metallic braid with loose ends (Sedov, V.V., 1982, p. 212, plate XXXVIII). This headdress was found together with bracelet-shaped temple rings and wire pins in the shape of open signet rings which fastened the temple rings to the hair. This burial dates to the late 11th century. The cloth bands were made from brocade (Plate 66, 1, 2, 12). These can be combined with subtype 2. Silk bands (subtype 3) were decorated with shields (Fekhner, M.V., 1973, p. 218, illus. 1g) and embossed plaques made from precious metals (Fekhner, M.V., 1974, pp. 647, 68). These were found in both rural burial mounds as well as wealthy urban burial sites and treasure troves (Pasternak, Ja.Kh., 1944, p. 125) (Plate 66, 6). Homespun band-type headdresses were also made from plant fibers (subtype 4) and wool (subtype 5) (Plate 66, 3-4). Analogous bands were made in the 19th century in Russian peasant life. They were decorated with geometric designs (Levinson-Nechaeva, M.N., 1959, pp. 32-33, illus. 12).

Bands constructed and sewn from cloth (subtype 6) have also been found in burials. For example, in a burial mound near the village of Ushmary in the Moscow region, a headdress was found (dig by M.E. Foss in 1924; Levinson-Nechaeva, M.N., 1959, pp. 27, 31, illus. 11) sewn from strips of fabric with the edges tucked in and sewn on the edges to a lining. The wool fabric was blue, with red and yellow design patterns. Seven-bladed temple rings were discovered nearby, as were strands of long, loose hair, which indicates that the headdress most likely belonged to a young girl. The burial mound dates to the 12th century.

A distinctive band sewn from various materials was also found in the Podolsk region of the Moscow area (digs by A.A. Yushko in 1965. Otchet IA, R1, issue no. 3058). It consisted of a wool band, onto which silk ribbons 1.5 x 2 cm in side had been sewn near the headband (Rus. очелье, ochel’je), and decorated by a pair of semi-spherical plaques made of billon. On either side of the face, there were seven-bladed temple rings. Under these, the hairstyle had been preserved in the form of curls, laid in a loop at temple-height. This burial mound dates to the 12th century.

Banded headdress made from plaques form subtype 7. They were decorated with series of plaques and plates. In burial sites, these were found on the frontal bones of the skull (Spitsyn, A.A., 1899, p. 306, illus. 16).

Medieval Russian treasure troves have revealed the most luxurious examples of this type of headdress (Kondakov, N.P., 1896, pp. 138-139, 145; Beljashevskij, N.F., 1901,[7]jeb: sic., see Beljashavskij, 1904. p. 150). These consisted of nine golden plates, seven of which were rectangular in shape with keeled ends (in the shape of an icon case), while the two on the ends were triangular in shape, tapering toward the outer ends. The plaques were joined by threads which ran through holes on the sides of the plaques. The headdress was akin to a diadem, with a headband made of plaques which were tied at the back of the head with a ribbon (Makarova, T.I., 1975, p. 44). They were decorated with enamel, pearls, and pendants, and were part of the ritual attire of medieval Russian princesses (Rybakov, B.A., 1970, pp. 36-38).

In urban archeological finds, analogous forms of headdress are also known, although they were more modest. For example, in the crypt under the ruins of Kiev’s Church of the Tithes, plaques from diadems were found: round with inserts, small hemispherical plaques, sewn in two rows, etc. They were preserved sewn to a fabric band (plate 66, 8). The quantity of plaques found on similar diadems were typically odd in number, since the base of these diadems had an initial form with a centerpiece or central figure. These diadems belonged to wealthy urbanites who perished in Kiev during the Tatar invasion in 1237 (Karger, M.K., 1958, p. 502; 1941, p. 79).

Plaques from similar diadems were also found in burial mounds. They were made from embossed or gilt silver and other alloys. For example, in the Gomel region of Belarus, a band made up of pewter plaques was found along with a headdress of type I. In the Novgorod region of the Chernigov area, in a burial mound near Khreplja (digs by A.V. Artsikhovskij, 1929-1930), a coronet made up of plaques decorated with ribbed wheels. Similarly-shaped plaques from the same kind of coronet were found in the territory of medieval Novogrudok (Pavlova, K.V., 1967, p. 37, illus. 10). They are also known from burial mounds in the former Pskov province, and from stone graves from the Lida district of the Vilensk Province (Spitsyn, A.A., 1899, p. 306, illus. 16), and also existed in the lands of the former Latvian SSR (Mugurevich, E., 1972, p. 389). E. Mugurevich believes that this type of headdress arrived in the North from the lands of medieval Rus’. A coronet made up of a row of sewn plaques with enamel was found only once, in burial mound I from the former Kostroma province, in Neryakhotsk county (Nefedov, F.D., 1899, p. 243, Plate 6, Illus 42) (plate 66, 10). It was sewn onto birch bark.

Subtype 8 includes headdress in the form of a crown with a birch bark or bast base, decorated with beads (Saburova, M.A., 1975, pp. 19-20) (plate 66, 9). E.N. Kletnova excavated a burial in the Smolensk region near Khozhaevo, in which she uncovered this type of headdress along with bracelet-shaped temple rings. She writes that upon the skull was located “a strip of birch bark which formed the basis of a headdress in the manner of a crown; it was strewn with a design of golden glass beads, laid horizontally and crossed by olive-shaped carnelian beads laid vertically” (Kletnova, E.N., 1910, p. 10). This burial mound dates to the 11th-early 12th centuries.

Aside from the types of headdress described above, archeological finds from the 10th-13th centuries have also included some details which tell of their construction, hairstyles, and the manner of their decoration. The most common and frequently encountered detail of headdress is the headband (Rus. очелье, ochel’e). In fact, this unique constructive detail, which was decorated using all kinds of techniques, are known from both the sewn and jewelry arts. For example, based on plaque imprints on a female skull, we can adduce the headband which was in a grave from the Sts. Boris and Gleb Church in Novgorod (Strokov, A.A., 1945, p. 73, illus. 32) (plate 66, 14; reconstruction by A.A. Strokov). It was rectangular in form with a lightly peaked top in the center. The entire surface of the headband was decorated with plaques. These included embossed plaques of gilded silver of various shapes and silver filigree. The very shape of this headband attests to the fact that it was sewn to a solid base. Along with analogous plaques, here too were found remains of silk fabric, “the golden shine of brocade” (Strokov, A.A., 1945, p. 70), which suggests that these headbands were part of expensive silk sets which included golden threads. This burial dates to the late 12th century.

A headband with a stiffened base was found in the Moscow region (dig by M.G. Rabinovich in 1956 near Zvezdochka) (plate 66, 13). It was made from a silk twill-weave. Embroidery in the form of trees inside archways was done in gold thread. The embroidery was bordered with golden-fabric bands which highlights that it was an individual decorative detail in a set. The grave dates to the 12th century.

A rich headband from a headdress was found in a grave under the Cathedral of the Assumption in the Moscow Kremlin (Sheljapina, N.S., 1973, pp. 57-58, illus. 4). It consisted of silk bands embroidered with gold and silk thread. In addition, the headband was decorated with pearls and a centerpiece in the form of a rectangular pendant(?) (Rus. дровница, drobnitsa), which has not survived (plate 66, 15). It was found along with a hair cap (Rus. волосник, volosnik) and a veil. This burial dates to the 13th century.

During the excavations in Novgorod in 1965, birch bark letter No. 429 was discovered. According to paleographic data, it dates to the 12th century (Janin, V.L., Zaliznjak, A.A., 1986, p. 207-208). It includes a list of clothing and “some female headdresses (3) with edging decorated with trim (or: from a multicolored band), and a headband…”. The last part is especially important, as it directly corresponds to the same detail of headdress which has been found in archeological sites from pre-Mongol Rus’. As is known, in the 20th century, this term came to be used in some provinces as the name of an entire headdress, preserving the meaning as the frontal part of a female headdress (Dal’, V., 1956, Vol. IV, p. 587).

Not infrequently, fragments of ribbons, fabric, and sometimes details of hairstyles are found in burials alongside temple rings, providing details about how the temple rings were worn. For example, from the materials from the Vologda expedition, it was possible to trace three methods for wearing temple rings: 1) braided into the hair at the temple or ear level; 2) threaded into the fabric of the headdress; 3) in the ears (Saburova, M.A., 1974, pp. 86-89, illus. 1). Cases are also known of temple rings being threaded into golden-fabric trim at the temples. A.V. Artsikovskij speaks about temple rings being worn threaded into a headband made of leather or fabric (Artsikhovskij, A.V., 1930, p. 46).

In addition, temple rings were fastened to leather bands. These are found everywhere. The bands were attached to headdresses in various ways. One common method was a leather or fabric band folded in half, with the temple rings threaded through them. They were passed through such that one ring was located belong another, while the lowest simply hung from the ribbon. This method was traced in Belarus in the lands of the Radimichi (Saburova, M.A., 1975, pp. 18-19, illus. 1-2). Seven-bladed temple rings were attached to stiff-based headdresses at the temples in this manner. An analogous method was also traced to the Moscow region. In burial mound 12 in the village of Mar’ino in the Podol’sk region, on the skull of a female burial, a fabric band was found in combination with seven-bladed temple rings (digs by A.A. Jushko i 1972, Archive of the IA, D. 5077, 5077a, #56, 57). During the process of restoration, imprints were found from the seven-bladed rings on the trim, as well as holes caused by the rings’ wires puncturing the fabric, allowing us to establish their method of wear. The temple rings, being laced through the trim, would have grasped the hair underneath it, fastening the hairstyle. In the burial site, of course, the hair was loose.

Under temple rings, there are often details of the hairstyle in the form of loops of hair which hang downward from the temple. As such, they would have lain under the temple rings. These loops and curls at the temples are usually found in female burial sites together with seven-bladed temple rings. They would have created a space between the temple and the rings, combining both utilitarian and aesthetic purposes (Saburova, M.A., 1974, pp. 91-92, illus. 4).

As can be seen from the description above, there were various methods for wearing temple rings.

In addition to temple rings, in urban settings and among the upper layers of society, all forms of ryasna (Rus. рясна) were worn – long pendants made up from blocks, chains, and their links. Various pendants were hung from these: kolts and plaques. Typically these were fastened to the headdress using signet-ring-shaped temple rings, one end of which was twisted into a spiral. Having pierced the headdress, the ring’s spiral would fasten the pendant to the headdress at this location. Ryasna, just like temple rings, came in a wide variety of shapes and methods of fastening to headwear.

In a 11th-12th century Suzdal’ necropolis, ryasna were found in the form of fused signet-ring-shaped rings. Three-beaded temple rings were suspended from them. This kind of ryasna was found in burials of young girls. Young women braided similar rings into their hair; older women typically wore these as a single ring at ear level (Saburova, M.A, Sedova, M.V., 1984).

In general, sets of these described types rarely occurred in life in their “pure” forms: more often, they appeared as combinations of various types. Such complex, composite forms sets were the result of the combinations of various forms which were worn at different ages. Exactly for this reason, female headdress included maidens’ coronets. This observation reinforces D.K. Zelenin’s theory that womenly headdress was a more complex form of maidenly headdress (Zelenin, D.K., 1926, p. 312). At the same time, maidenly headdress could include details from women’s headwear: a stiffened base, or the headband with temple rings. Composite headdress was also embroidered. It is possible that the term ush’v’ (Rus. ушьвь) reflects some type of similar headwear. Maidenly headwear constructed from ribbons was worn along with various headwear of types I and II. In an illumination from the Radziwiłł Chronicle, we can see a woman in a veil which is tied down with ribbons (Fotomekhanicheskoe vosproizvedenie Radzivillovskoj ili Kenigsbergskoj letopisi, 1902, folio 33).

Coronets and headbands were also worn with headdress of types I and II. For example, on a 14th century icon with a depiction of St. Barbara we can see a veil (Rus. убрус, ubrus) with a headband (plate 66, 22), and on a 14th century icon of St. Paraskeva with Scenes of Her Life, we see a wimple (Rus. плат, plat) and a diadem with a centerpiece (plate 66, 20). On works of small-form ceramics from the 13th-14th centuries, the myrrh-bearers are shown wearing headdresses with defined headbands (plate 66, 18-19, 21).

The aforementioned does not refute the principles of the proposed classification of headdress, but rather clearly points to a unified system for its design.

Decoration of medieval Russian clothing

As with headdress, clothing has rarely been preserved whole. Archeologists discover only their details. Let us start with those.

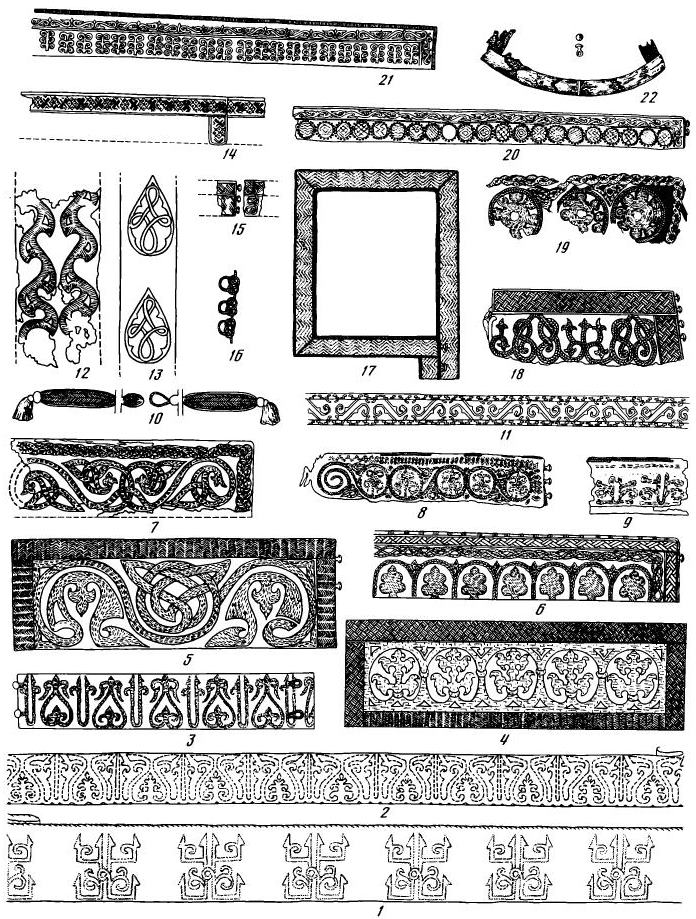

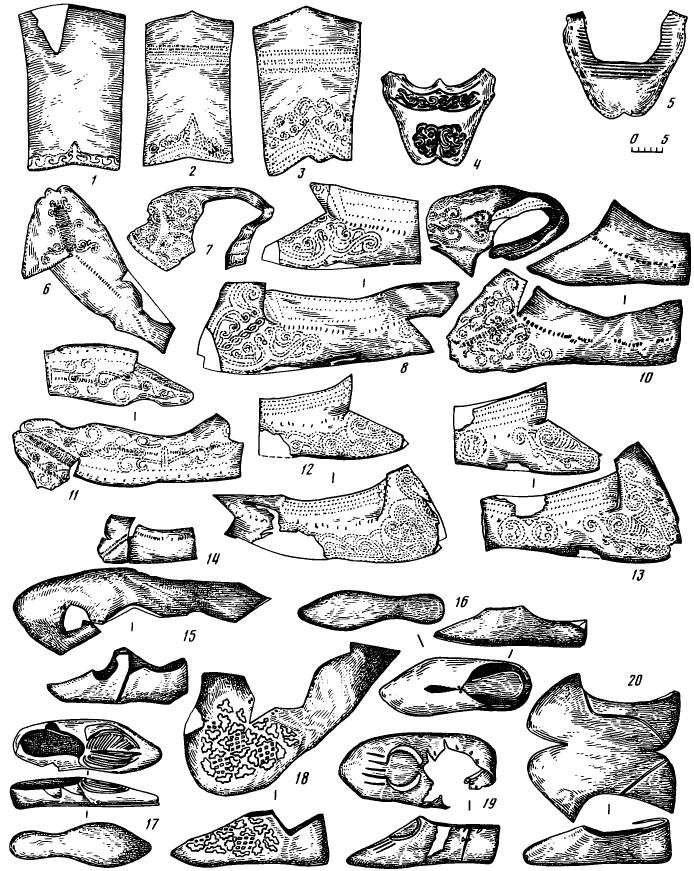

Collars

As a result of the excavations of a Suzdal’ necropolis, details of collared clothing have been studied. These were found in burials from the late 11th-mid-12th centuries (Saburova, M.A., 1976, pp. 226-229; Saburova, M.A., Sedova, M.V., 1984, pp. 122-126). The largest group is comprised of standing collars (Rus. стоячий воротник, stojachij vorotnik; jeb – see also plate 75, 2) with openings on the left (plate 67, 8-9, 14-16, 20-21), a smaller number of collars in the form of a chestpiece (Rus. воротник-карэ, vorotnik-kare) (plate 67, 17; jeb – see also plate 75, 4), one trapezoidal-shaped collar (plate 67, 22; see also plate 75, 5), and one round collar belonging to the so-called “bare-neck” type (Rus. голошейка, goloshejka; jeb – see plate 75, 1). It is interesting that in almost all of the burials, the clasp buttons were located to the left of the neck, including in burial sites where remnants of the collars themselves were not found. Exceptions are rare (plate 67, 22).

The details of the Suzdal’ collars were made of Byzantine silk cloth. They were decorated with gold-cloth bands, and were also embroidered with silk and gold threads. One collar was decorated with pearls, the work of medieval Russian female artisans.

For standing collars, the presents of a stiffened base (birch bark, leather) was characteristic, decorated with ornamentation at the top of the collar and with an opening to the left. They were 2.5-4 cm tall. The lower edge of all of the listed types of collars was pierced with a needle, traces of how they were fastened to the outfit. The presence of fragments of fabric on the inner side of these collars allows us to determine that the clothing itself was made from threads of both silk and vegetable fibers. All of the types of collars found in Suzdal’ are also known in traditional Russian clothing from the 19th-20th centuries, and were characteristic for shirts (Rus. рубаха, rubakha) of various styles. By including these 19th-20th shirts as analogies, it became possible to match the details of the standing collars from the burial sites with standing collars from men’s traditional Russian peasant shirts (Rus. косоворотка, kosovorotka, “Dr. Zhivago shirt”). Trapezoidal collars and chest pieces also matched decorations on some Russian wedding shirts (Molotova, L.N., Sosnina, N.N., 1984, p. 39, illus. 62, 184), and allowed us to attribute these details as shirt decorations.

Russian peasant shirts from the 19th-20th centuries as well as our [11th-12th century] collars stood 2.5-3 cm tall. They were decorated with various kinds of embroidery and later fasteners made from factory-produced buttons, which were analogous to earlier fasteners in the form of metallic, oval-shanked buttons which, as on the Suzdal’ collars, had a button sewn to the right side and a thread loop on the left (State Historical Museum, Inv. no. 77657, V476). On later shirts with chest pieces and trapezoidal collars, just as also on the medieval shirts, the collar was decorated with embroidery and was bound with a ribbon folded at right angles to the sides of the neck. It had an opening on the left, along which the left side of the collar descended. These shirts had fastenings of a different kind, with buttons or ribbons (Molotova, L.N., Sosnina, N.N., 1984, illus. 63, 184).

In archeological sites from medieval Rus’, collars of the forms described above were widely used. Standing collars are found in both male and female gravesites, while chest pieces are most commonly found in male burial sites. For example, in the Ivanovo region, collars made from golden fabric bands and having the form of chest pieces with openings on the left were found in male burial sites (plate 67, 5) (excavations by K.I. Komarova in 1975). A trapezoidal collar of gold-fabric trim was found in Staraya Ryazan’ (excavations by V.P. Darkevich in 1977). In archeological sites from pre-Mongol Rus’, however, standing collars with openings on the left were most common (plate 67, 6-7, 18-19). These are found everywhere in layers from medieval Russian cities (in medieval Rus’, Staraya Ryazan’, and in Smolensk). These are also known from treasure troves (Mikhaylovsk treasure trove, 1903, Kiev) (Fekhner, M.V., 1974, p. 68, example 6; Guschin, A.S., 1936, p. 29 and subsequent). Some of these collars were as tall as 7-7.5 cm. In addition to embroidery, these were decorated with pearls and plaques.

Such a wide distribution of standing collars with openings on the left indicates the prevalence of clothing with fastenings on the left and of their use among various layers of society.

As is known, for Russian national costume, double-breasted items are characteristic. A work by T.S. Maslova raises the theory that the distribution of double-breasted attire and peasant shirts occurred at the same time (Maslova, G.S., 1956, pp. 581, 702). Double-breasted clothing can be seen in illuminations from the Radziwiłł Chronicle. For example, in a miniature depicting the founding of Kiev, two figures are shown in long outerwear with an overlap on the left side (Radzivillovskaja ili Kenigsbergskaja letopis‘, 1902, folio 4). Apparently, tall collars (more than 4 cm tall), lined with birch bark or leather and with an opening on the left, also pertained to double-breasted outerwear.

Ozherel’ya

The ozherel’ye (Rus. ожерелье, ozherel’e, plural ожерелья, ozherel’ja) were a form of neck decoration, similar to the collars described above. They were also sewn onto fabric and were often lined with birch bark or leather. They were worn unattached to the clothing. Typically the entire outer surface of ozherel’ya was covered with embroidery, decoration, or golden-fabric trim, as well as with plaques and log-shaped beads (Rus. колодочки, kolodochki, “little logs”). The plaques and log-shaped beads were edged with pearls and beads. Inside the plaques, there were insets of stone or colored glass. In contrast to attached collars, an ornamental band decorated these unattached ozherel’ya and below (Fekhner, M.V., 1974, p. 68, example 3). Judging by depictions from medieval Russian frescoes, standing ozherel’ya were part of the formal attire of the upper layers of society. For example, in a 12th-century fresco from the Church of St. Kirill in Kiev, St. Euphrosyne is shown in rich clothing decorated with plaques, a mantle (Rus. оплечье, oplech’e; jeb – see below), and a standing ozherel’ye. The latter differs from those above in that the fastenings were located in the center of the collar.

Both ozherel’ya and their plaques are known not only from wealthy burial sites and treasure troves, but also from the layers of medieval Russian cities, and even from rural burial mounds. In the 12th-13th centuries, they were widely used across all the lands of Rus’, including its outlying regions (Saburova, M.A., 1976, p. 229). In Russian folk costume from the 19th-20th centuries, neck decorations in the form of standing collars (Rus. стоечка, stoyechka, “little stand”) made with a stiffened base and decorated with pearls, beads, embroidery and plaques were in widespread use (Molotova, L.N., Sosnina, N.N., 1984, illus. 59, 171-172).

Mantles

A mantle (Rus. ожерелье-оплечье, ozherel’e-oplech’e) was a form of formal outerwear, made of cloth and decorated. It the literature, it is also called a barmy (Rus. бармы) (Korzukhina, G.F., 1954, p. 56). Fragments of similar mantles, decorated about the chest with silk cloth of gold, gold-fabric bands, and metallic plaques with inserts of glass and carnelian were found in Chernigov near the foundation of the 12th century Church of St. Michael. The hem of this outfit was likewise decorated with plaques (Otchet Chernigovskoj uchenoj komissii, 1910, p. 11). A depiction of an outfit with a similar mantle can be seen in the frescoes of Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral (Lazarev, V.N., 1970, pp. 38-39) an on the aforementioned 12th-century fresco from Kiev’s Church of St. Kirill. These mantles decorated both female and male outfits (idem., pp. 47-49). Remains of mantles have been found not only in urban tombs, but also in rural burial mounds. Unlike the sumptous mantles of the upper class, these were chest decorations made of inexpensive silk fabric with embroidery and were a finishing layer on top of an outfit which, it appears, was sewn from homespun material (Fekhner, M.V., 1971, p. 223). For example, in the Moscow region (the Domodedovo district), a fragment of silk fabric was found in a female burial in burial mound #5 near the village of Novlenskoe, in 1969. It lay upon the chest. Along the edge of the fabric, a gold-fabric band had been attached. The fabric preserved gold-thread embroidery in the form of quatrefoil rosettes. Within the petals of these flowers, embossed plaques of gilt silver had been sewn on. The plaques were sort of compressed into a triangular shape and pointed toward the center of the rosette. They were attached to the fabric by means of three holes each. This burial dates to the 12th century.

One more mantle was found near the Pushkino railroad station in the Moscow region in 1925 (Fekhner, M.V., 1976, p. 224). This mantle was represented by several fragments of silk. Its individual fragments came together into a rectangular piece of cloth. It was decorated with gold-fabric trim on all sides. The embroidery was done in couched (Rus. “в прикреп”, “v prikrep,” “in attachment”) gold and silver thread. The design was in the form of four trees within round medallions (plate 67, 4). This was more accurately an embroidered chest appliqué (Rus. “вошва”, “voshva”). Similar mantles have also been found in several burial sites in the Moscow, Ivanovo, and Vladimir regions (Fekhner, M.V., 1973, p. 219, No. 7, 2, 8). These have been found in both male and female grave sites.

Sleeve Cuffs

Sleeve cuffs (Rus. опьястья, opjast’ja, also called обшлаги рукава / obshlagi rukava, зарукавье / zarukav’e) and detachable cuffs (Rus. поручи, poruchi) are also known as opyast’ya in clergical vestments. Finds of these decorated cuffs in medieval Russian archeological sites are extremely rare.

A well-preserved opyast’ye was found in the tomb of Prince Vladimir Yaroslavich, who died in 1052 (Rjabova, M.P., 1969, p. 130). This opyast’ye consisted of a rectangular piece of fabric, 23 cm long and 4.5 cm wide. Two buttons were attached to one of the short sides, and the other had loops of thread. These were 20 cm apart. The fabric was red satin. It was covered with gold embroidery. The decoration consisted of bands of stylized lilies (Rus. крины, kriny) surrounded by heart-shaped figures, between which there were plant sprouts which bent back toward their base and had triangular widenings at the top (plate 67, 3).

The celebrated trapezoidal cuffs belonging to St. Varlaam of Khutyn have survived from the 12th century. Their figural and ornamental embroidery in silver and gold thread has survived, along with their pearl edging (Jakunina, L.I., 1955, p. 35, illus. 13).

Finds from burial mounds are almost unknown. M.V. Fekhner mentions only one decorated sleeve cuff from the collection of the State Historical Museum. It was found on the right forearm in a burial site uncovered in the Moscow region (Fekhner, M.V., 1971, p. 219). It was decorated with gold-fabric trim. The absence of opyast’ya in burial mound interments suggests that the expensive imported fabric and trim was not used for the cuffs of burial clothing, and were used only on collars.

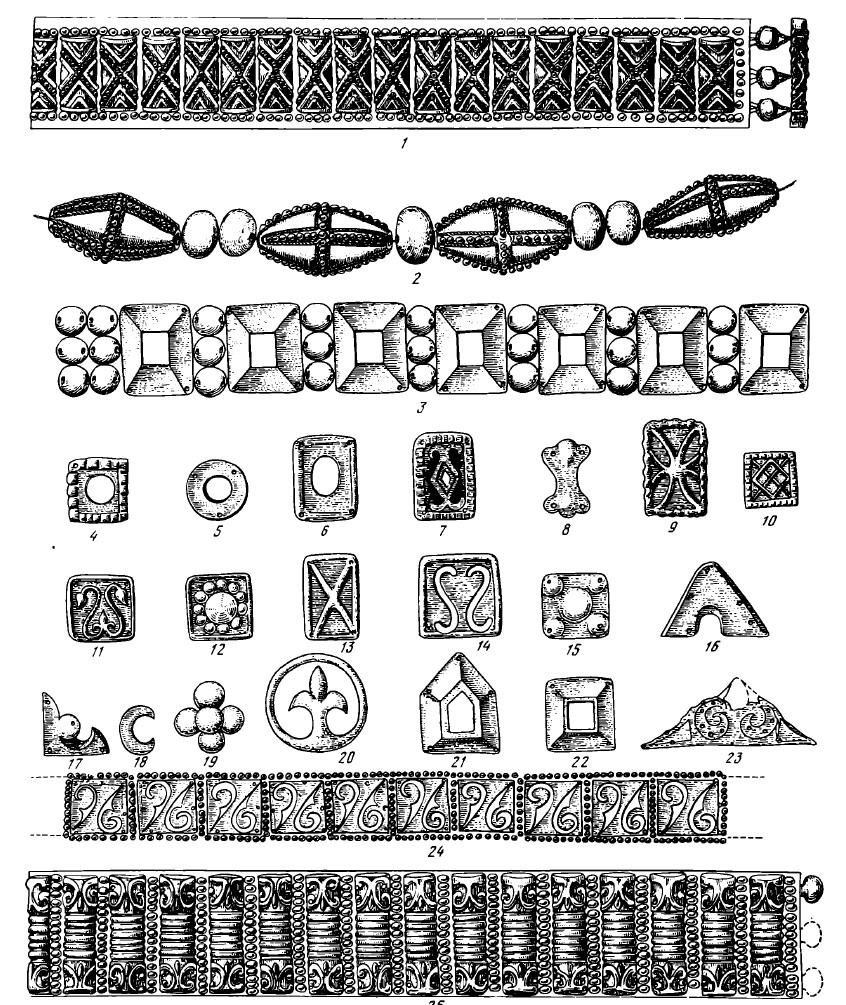

Belts

In wealthy burial sites from pre-Mongol Rus’, belts have been found repeatedly. V.V. Khvoyko writes about finds from burials in the Central Dnieper region (in Sharki and Belgorodok) of belts made of silk with Byzantine designs (Kvojko, V.V., 1913, pp. 55, 83). Several of the belts had gilt silver plaques (Kvojko, V.V., 1904, p. 101). Silk belts decorated with gilt plaques were also found in digs by L.K. Ivanovsky in the former Petersburg provice (Spitsyn, A.A., 1896, p. 159, plate XVI, 3), as well as in digs by D.Ya. Samokvasov in the former Kiev province on Knyazhaya Gora. Similar gilt silver plaques on a belt were also found at the Raikovets settlement (Goncharov, V.G., 1950, plate XX, 11). They have also been found in treasure hoards. For example, in a treasure trove in Staraya Ryazan’ found in 1887, a silk ribbon was found covered with a series of the same sort of plaques and edged with beads (Guschin, A.S., 1936, pp. 78-80, plate XXIX, 7). It seems that these ribbons decorated with plaques with various embossed designs, as well as plaques with enamel, could decorate not only headbands and ozherel’ja, but also belts. In the tomb of Prince Vladimir Yaroslavich, a belt was found made of Byzantine pattern silk bands, the decoration of which was repeated in the embroidery on the cuffs from the same burial (plate 67, 2).

Borders

Borders (Rus. кайма, kajma) was trim sewn to the edges of clothing (lining, collar). Researchers of medieval Russian clothing have long since turned their attention to the fact that clothing of the pre-Mongol period was trimmed with various forms of ribbon (Prokhorov, V.A., 1881, pp. 67, 76-77; Rzhiga, V.F., 1932, p. 54). Among the archeological samples of fabric in the State Historical Museum, a large quantity is composed of various kinds of ribbon used to decorate the edges of clothing (Fekhner, M.V., 1971, pp. 219-221). M.A. Novitskaya studied silk fabrics including embroidered trim found in Ukraine. No data has survived about the location of these details on clothing. Using evidence gleaned from medieval monuments of artwork (frescoes, icons, written sources, etc.), she compared the archeological material with the decorations on various details of formal wear. Out of this entire mass of material (headbands, sleeve cuffs, ozherel’ya, collars) she also differentiated trim which was used to decorate “the hem and edges of cloaks (Rus. корзно, korzno) and trim which was positioned vertically along the center of an outfit” (Novitskaja, M.A., 1965, pp. 34-35).

As an example of fabric used to decorate an outfit “from top to bottom,” from collar to hem, we can look at one of the fragments found in the Mikhaylovsky hoard in 1903 in Kiev. This was a strip of cloth 14 cm wide. It was cut out from a dark-pink colored silk. It had a stylized floral design carried out in golden thread (Fekhner, M.V., 1974, p. 68, example 1). The design on the specified fragment was positioned vertically and consisted of two parallel figures. A design with vertically positioned figures was also found on a fragment from the Vladimir hoard of 1865 (Guschin, A.S., 1936, plate XXIX, 2, 4) (plate 67, 12). It depicted a climbing vine, but the fragment itself was folded in half vertically, suggesting that this band was used to decorate the open edge of a frontally-open (Rus. распашной, raspashnoj, “swinging, worn without fastening”) garment, or was used in imitation thereof to create an item which resembled the ceremonial clothing of the nobility (Lazarev, V.N., 1970, p. 46). It appears that when decorating clothes from top to bottom, it was characteristic to position the design along the length of the trim.

In recent years, in the southern Russian steppes in burial mounds from the Pecheneg-Khazar region of the 10th century (Moshkova, M.G., Maksimenko, V.E., 1974, p. 10) and Polovtsian burial mounds from the 12th century (Otroschenko, V.V., 1983, pp. 300-303), clothes in the form of short caftans were found. The Byzantine trim on the Polovtsian caftan was analogous to trim from medieval Russian Sharogorod, which allows us to suppose that the trim from Sharogorod belonged to a caftan. A caftan was also depicted on a 12th century fresco from the Church of St. Kirill in Kiev (Blinderova, N.V., 1980, pp. 52-60) (plate 67, 1).

Wider types of borders are also known from medieval Russian hoards. M.A. Novitskaya proposed that these were used to decorated the hemline of long-length outfits similar to the ones depicted on the frescoes from the St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev, where we can see a group portrait of the family of Yaroslav the Wise (Novitskaya, M.A., 1965, p. 35). Wide border trim was also found in the Vladimir hoard of 1865. This trim was made from a multi-layer silk Byzantine fabric. It was embroidered with gold thread in the form of triangles filled with a pattern of morning-glories and stylized lilies.

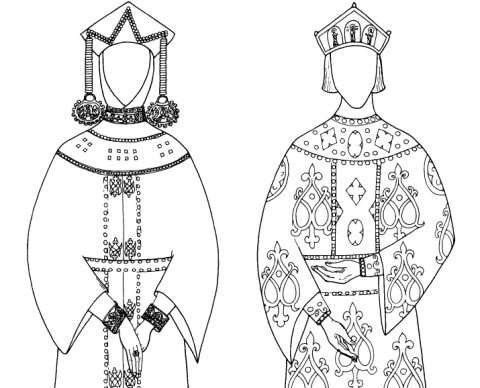

The most important material for the reconstruction of the clothing of medieval Rus’ is presented by unique finds of their whole forms.

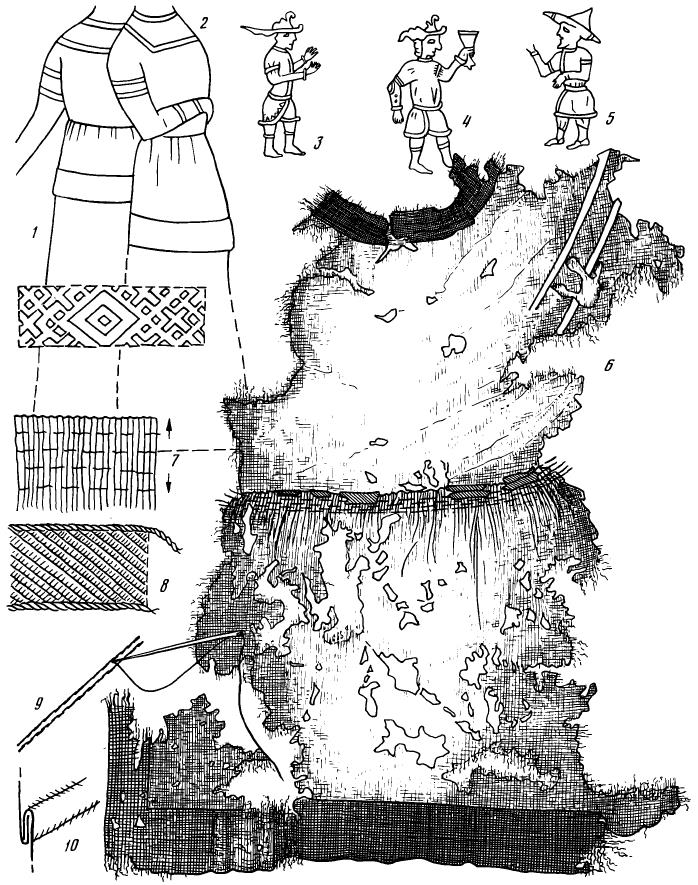

Details of the cut and entire forms of clothing (dress, mittens, socks, stockings)

An entire dress was uncovered in 1957 in the layers of Toropets, having been burned in the second half of the 13th century as a result of the Lithuanian invasion. In the 30 years since its excavation, it has become badly deformed, as it was not restored. The dress consists of a large number of significant fragments. It was sewn from wool fabric of various textures. The upper part of the dress was sewn from plain weave fabric, while the bottom was made from a twill weave. Folds can be seen on several fragments. A sleeve was well preserved, with a gore to the wrist. It was made from a twill weave fabric, while the gusset was of plain weave fabric. The seams which joined the pieces of the dress were done in such a way that the cut fabric would not unravel, using flat-felled seams (Rus. запошивочный шов, zaposhivochnyj shov). This sewing technique arose with the styling of the outfit (plate 68, 10). A fragment of fabric in the bran’ style was also found in Toropets (plate 68, 12).[8]jeb: sic., see plate 68, 11). Yet another whole dress was found in Izyaslavl. It was sewn from several types of very thin wool plain-weave fabric and tailored into a top and cutoff skirt. The top was lined. The collar was sewn from a band of thicker fabric. The border was folded in half and sewn down with horizontal stitches. The opening, located on the left side of the collar, opens into the seam on the shoulder. The skirt was attached to the top at the waistline. It was assembled using very small gathers then sewn together using four parallel seams. The seam which joins the top to the skirt was covered with a gold-fabric band, edged on either side with silk threads which have been twisted into a rope-like form. A border was sewn to the hemline. Judging by its seams, the sleeve was attached off the shoulder, where there is a band of fabric 5 cm wide. This detail was sewn to the sleeve using a fine running stitch (Rus. шов вперёд иглой, shov vperjod igloj, “seam going forward with the needle”), and then in the reverse direction, filling in the gaps in the stitch so accurately that it appears to have been stitched by machine.

Judging the length of the dress is difficult. Only scientific restoration would allow a full understanding of not only the technology used to create it, but also its form and size. If the proportions of the assembled dress are basically correct, then it was about knee length.

The existence of sewn dresses in medieval Russian cities are confirmed by finds excavated at the Raykovets settlement in Ukraine. This city perished during the Tatar invasion (Goncharov, V.I., 1950). Among the piles of burnt fabric located in the repository of the Kievan Institute of Archeology, there are fragments of wool, linen, and silk fabrics of various structures. The seams have survived on some of these. Plain weave fabrics were folded or gathered into very small pleats. Clothing with gathers and pleats are known from the burials at Birka as early as the 11th century. There is a theory that clothing with gathers were an import from the lands of the southern Slavs (Hägg, J., 1974, pp. 20-26).

In some areas of the south Slavic world, traditional clothing has been preserved to our time which was constructed with the assistance of various kinds of folds, pleats, and gathers (on skirts, sarafans, and on shirt sleeves and collars) (Jelka Radous Ribarie, 1975. See illustrations in the text and album).

Folds, pleats and gathers are also known from the traditional clothing of Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians (Maslova, G.S., 1956, p. 551, illus. 1; p. 552, illus. 1; p. 555, illus. 4; p. 604, illus. 27).

These dresses and their fragments attest to the existence of sewn dress among medieval Russian cities which were created using a different method: from both uncut and cut pieces of cloth. Both methods existed in this stage of the history of clothes-making, but also exist in traditional Russian costume to this day.

These dresses also provide us with an insight into the culture of sewing, the features of style, and the character and variety of stitches. The dress from Izyaslavl supports the presence in medieval Rus’ of clothing which was cut to the figure (fitted). This kind of clothing can be seen on the “maiden” in the Svyatoslav Izbornik. She wears a dress with a mantle and a pleated skirt. (Izbornik Svjatoslava 1073 g., 1977, p. 251).

The capital letter illuminations in medieval Russian manuscripts depict various types of sewn clothing, including some fitted using pleats and gathers.

In addition to entire dresses, archeological sites have also revealed various parts of clothing, preserved almost entirely. For example, in the layers from 13th century Novgorod, a male felted hat was found, in the form of a cap, 20.5 cm in height. Entire mittens have also been found in the layers from medieval Russian cities. Both knitted (State Historical Museum, inventory 1965, No. 2709) and of leather (Izjumova, S.A., 1959, p. 220, Illus. 220, 3; Ojateva, E.I., 1962, p. 92, Illus. 10; Ojateva, E.I., 1965, p. 51, illus. 3, 1) have been found. Rare instances of knitted wool socks, stockings, and shoes have also been found (Golubeva, L.A., 1973a, p. 97, illus. 31, 1-3; Shtykhov, G.V., 1975, p. 102, illus. 53; Artsikhovskij, A.V., 1930, p. 102).

In the layers of medieval Russian cities, knitted, braided, and woven belts made from woolen threads are often encountered (State Historical Museum, Inv. 1943, No. 1724, 1725). Leather belts with plaques have also been found (Drevnij Novgorod, 1984, illus. 287). Surviving metallic plaques from leather belts also allow their reconstruction (Rybakov, B.A., 1949, p. 54, illus. 22). The forms of medieval footwear are known best of all.

Footwear

Footwear is an integral part of one’s attire. Just as with costume, the footwear of each nation was special and traditional. Customary forms and the methods of their creation were handed down from generation to generation, reflecting the ethnic history of their people and the ethnocultural ties at various stages of their development. Shoes were made of bast and leather.

Bast Shoes

The oldest form of footwear to have existed in ancient Rus’ was bast shoes (Rus. лапти, lapti) woven from the bark of linden, birch, and other species of trees. According to scholars of clothing, bast shoes were in use in the Stone Age (Maslova, G.S., 1956, p. 714). They are almost unknown in the earliest layers of medieval Russian cities. In Novgorod, only one bast shoe has been found, in layers from the 15th century. The existence of bast shoes in earlier times is known from finds of tools used in the weaving of bast, or bast awls (Rus. кочедык, kochedyk) (Levashova, V.P., 1959a, p. 56, illus. 5, and 1959b, pp. 90-91), and from the presence of woven footwear from burial grounds (Levashova, V.P., 1959a, pp. 42-43). Soles from woven leather straps were found in the Lyadinsky burial ground and in a Vyatichi burial mound (Artsikhovskij, A.V., 1930, p. 102). Based on the fact that the inner side of the soles foun din the Lyadinsky burial ground preserved the remains of linden bast from the shoe itself, V.P. Levashova proposed that woven leather soles from the Vyatichi burial mound may have also belonged to common bast shoes made of linden. The bast shoes from the burials described above had different weaves: the soles from the Lyadinsky burial ground were woven diagonally, while the one from the Vyatichi burial mound were square woven.

Judging by the material from later ethnography, bast shoes came in the form of a shoe (Rus. туфель, tufel’) with short sides, similar to the Polesie-region, square-woven bast shoes, as well as in the form of deep, covered, diagonal-woven bast shows of the northern type known in the Novgorod region. Bast shoes were fastened using long strings or ties, which were passed through the sides of the shoe and wrapped around the leg. Bast shoes were worn over stockings, socks, leggings, or leg wraps (Rus. обмотки, obmotki) (Artsikhovskij, A.V., 1930, p. 102; Golubeva, L.A., 1973a, p. 97, illus. 31, 4).

In antiquity, there existed several names for shoes of the bast shoe type: “lychenitsa,” “lychake,” and “lapete” (Rus. “лычъница”, “лычакъ”, “лапътъ”), a derivative of which, “lapotnik’“(Rus. лапотникъ) is known in written sources and which dates, according to scholars, back to the proto-Slavic era (Vakhros, I.S., 1959, pp. 10, 121-124, 126).

The earliest depiction of bast shoes dates to the 15th century. In an illumination from the Life of St. Sergius of Radonezh, there is a scene of him plowing with the peasants while wearing bast shoes (Artsikhovskij, A.V., 1930, p. 187). It seems that urbanites did not wear bast shoes. Naturally, bast shoes were a laborer’s footwear, associated with work in the fields. Bast shoes were always worn by the poorest people, right up until the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Leather Footwear

Leather preserves well in the cultural layer of many medieval cities. In modern time, it has accumulated as the most valuable material for the study of leather footwear. In Novgorod alone, several hundred thousand examples of various kinds of footwear have been found. These include “bog shoes” (Rus. поршни, porshni), a low type of footwear similar to bast shoes; shoes (Rus. башмаки, bashmaki), a type of footwear with a collar at the ankle; boots (Rus. сапоги, sapogi) and ankle-boots (Rus. полусапожки, polusapozhki, “half-boots”), a type of footwear with boot legs; and shoes (Rus. туфли, tufli), footwear with low sides rising up to the ankle.

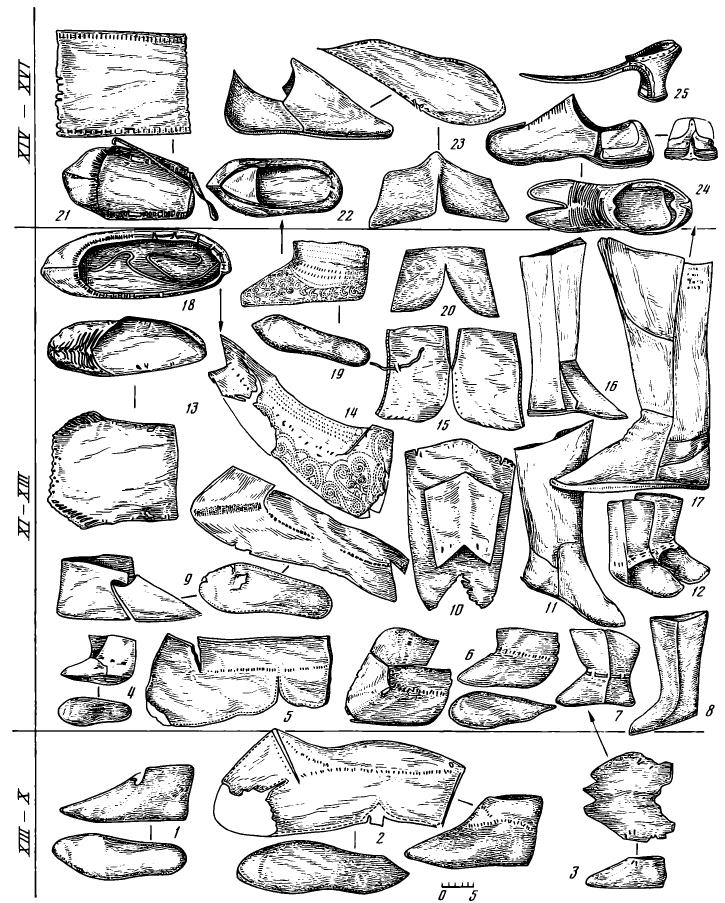

Serious study by S.A. Izyumova (Izjumova, S.A., 1959) was dedicated to Novgorodian footwear. This work created a typology and chronology for the basic types of footwear worn by Novgorodians in the 10th-16th centuries.[9]jeb: See my translation of this work on my blog: https://rezansky.com/leatherworking-and-shoemaking-in-novgorod-the-great/.

The Finnish scholar I.S. Vakhros analyzed the names of footwear in the Russian language and mapped them to specific forms of footwear (Vakhros, I.S., 1959).

Further systematization of leather footwear was carried out by E.I. Oyateva based on materials from Pskov (Ojateva, E.I., 1962, pp. 77-95) and Staraya Ladoga (Ojateva, E.I., 1965, pp. 42-59). In addition, she has also studied materials from several other cities and countries of the West (Ojateva, E.I., 1970, pp. 112-118).

In the current work, we have used new materials excavated in Novgorod, Beloozero, Staraya Russa, Minsk, Polotsk, and Moscow, as well as from burial sites from the 10th-13th centuries, allowing us to move beyond the local study of medieval Russian footwear and to generalize all available material.

We should note that the same E.I. Oyateva created the most successful classification scheme [for leather footwear]. The largest category in her typology is called a “group”. Group I includes all types of soft shoes; group II includes all rigid forms of footwear. The fashion (shape) of footwear forms the second category in this typology, called a “type”. The 1st type is made up of shoes (bashmaki), the 2nd type is boots (sapogi), and the 3rd is bog shoes (porshni). Following this classification, let us look at each of these types of footwear in order.

Soft-form shoes (Group I)

Type 1: Shoes (Rus. башмаки, bashmaki)

This is the oldest type of footwear in Rus’. Shoes have been found in Staraya Ladoga in layers from the 8th-10th centuries (plate 69, 1-3) (Ojateva, E.I., 1965, pp. 42-50). This is soft footwear made from tanned cow or goat leather with a collar above the ankle. Based on the cut (whether they were made from a single piece or two pieces of leather), shoes can be divided into two subtypes. One-piece shoes were cut from large pieces of leather, then the parts were joined using butt seams (Rus. тачный шов, tachnyj shov) and hidden seams (Rus. выворотный шов, vyvorotnyj shov, “inverted stitch”). One-piece shoes have ben found in Novgorod and Staraya Ladoga (table 69, 3), and in other cities from the 10th-13th centuries (Izjumova, S.A., 1959, p. 201). A shoe made from a single piece of leather was also found in the Raykovetsky settlement (Goncharov, V.K., 1950, plate XXX, illus. 8).

In Staraya Ladoga, among early shoes there were some made from two pieces of leather for the upper and sole (plate 69, 2). Shoes made from two pieces of leather are wide distributed throughout the layers of medieval Russian cites from the 10th-13th centuries. There are two variants of their cut known: with seams on the side (plate 69, 4-5, 9, 14, 19) and with seams in the back (table 69, 6).

Materials from excavations in Staraya Ladoga, Pskov, Novgorod, Beloozero, Minsk (Shut, K.P., 1965, pp. 72-81), Staraya Ryazan’ (Mongajt, A.L., 1955, pp. 169-170), Drevnee Grodno (Voronin, N.N., 1954, pp. 61-62), Moscow (Rabinovich, M.G., 1964, p. 287; Sheljapina, N.S., 1971, pp. 152-153), Polotsk (Shtykhov, G.V., 1975, pp. 72-80), Staraya Russa (Medvedev, A.F., 1967, p. 283), and other cities attest to a single tradition in the production of medieval Russian shoes starting in the 8th century. This unity is expressed in the existence of shoes of a single style in all medieval Russian cities. Original shoes with an elongated heel existed only in Beloozero, as a peculiarity of the leather craft in that city (Ojateva, E.I., 1973b, p. 204).

The fashion of cutouts on the heel or upper of shoes was carried forward into the fashion of stiff boots.

For shows from the 8th-11th century, one essential feature was characteristic: their soles were not clearly oriented for the left or right foot, although the cut of the uppers was assymetrical and oriented for the left or right foot (Ojateva, E.I., 1962, pp. 89-90). The soles of medieval Russian shoes were shown to the upper using a hidden seam, while the details of the uppers were sewn using butt seams.

Medieval Russian shoes from the 10th-14th centuries were fastened using a lace which was passed through a series of holes around the ankle. This manner of fastening was suitable for feet of any instep.

Shoes were decorated with embroidery. In the 8th-10th centuries, the main form of decoration was stripes in the center of the toe. This was done using small stitches which pierced the leather (plate 69, 2).