Having enjoyed myself reading the chapter on ink from Schavinsky’s Notes on the History of Painting Techniques and Paint Technology in Medieval Rus’, I decided to read on into the next chapter on “book art,” or illumination. This chapter provides an interesting overview of some of the paints and pigments used throughout the middle ages in Russia, as well as some of the preferred binders they used. It also touches upon gilding methods, and the evolution of illumination styles over the centuries. I found particularly interesting his description of the use of garlic juice in the copying of images from one surface to another.

Illumination

A translation of Щавинский В. А. «Книжное художество.» Очерки по истории техники живописи и технологии красок в древней Руси. М., Л., 1935. с. 39-50. / Schavinskij, V.A. “Knizhnoe khudozhestvo.” Ocherki po istorii tekhniki zhivopisi i tekhnologii krasok v drevnej Rusi. Moscow-Leningrad, 1935, pp. 39-50. [Notes on the History of Painting Techniques and Paint Technology in Medieval Rus’.]

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.icon-art.info/bibliogr_item.php?id=10230. ]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

Compared to painting on other materials, illumination on parchment and paper stands out in its technical simplicity. This explains the paucity of both Russian and foreign literary descriptions of both ornamental and miniature art. The only exception is gilding, which required the use of specific methods. The selection of pigments did not present any particular difficulties, and were worked primarily on egg whites or tree resins. In order to trace the relationship between Russian and Western European illumination techniques, we must first look at the history of the binders (Rus. связующий, svjazujuschij) that were used.

Among Latin-Byzantine authors of the 10th-12th centuries, egg white (Rus. белок, belok, “albumin”) was of primary importance. A particularly detailed and extensive description of the preparation of egg-white binder can be found from the author of a manuscript fragment from the late 11th or early 12th century, known as the “Anon. Bernensis.”[1]“De clared. Anonymus bernensis.” Quellenschr. f. Kunstgeschichte. Vol. VII. Wien, 1874. He was aware of two means of separating the liquid part of the dissolved proteins from the gelatinous structural components of egg whites; the first was by shaking them, then filtering them and whipping them with a whisk until foamy; the second was draining the parts that settled when it was left in the cold. He decidedly preferred the latter. Heraclius, an artisan who worked nearly a century earlier, knew only of a single method, of repeated (7-8 times) filtering of the egg white mixed with water.[2]Heracl., III, XXXI. Theophilus, a contemporary of the anonymous artisan, created paint for illumination using two methods: using natural gums (Rus. камедь, kamed’) for everything except green, white lead, red lead, and carmine. Green veride salsum[3]See the section on yar’ (Rus. ярь, a green pigment obtained through the oxidation of copper) in Chapter 7. was not suitable at all for illumination;[4]“Veride salsum no valet in libro.” (“Veride salsum should not be used in books.”) veride Hispanicum[5] See the section on yar’ in Chapter 7. should be based on pure wide, sometimes adding to it some vegetable juices.[6]“Sucum gladioli, vel caulae, vel pori.” (“Juice of the iris, from either the stems or the pores.”) Red and white lead and carmine were made using egg whites.[7]Theophilus, Diversarum artium schedula. p. XXXIX. Cennino Cennini advised basing paints on egg whites, although he also allows for the use of natural gums.[8]Cen. Cen. p. X.

Judging by the technical records of Russian scribes from the 17th century and later, the primary binder for paint in use at that time was no longer egg white, but rather tree gum. There are indications, however, that this earlier technology was closer to the technique used by the Byzantines. The compiler of a 17th-18th century collection[9]Manuscript no. XXXIII. Enumeration of manuscripts done by V.A. Schavinskij according to a book by P.K. Simoni; in a personal copy stored in the Institute of Historical Technology of the State Academy of the History of Material Culture, V.A. Schavinskij thus picked out each of the manuscripts which he used in his work. M. F. records, with repetitious emphasis:

Старые писцы писали златом и киноварь под злато, за клею месть в масле яичном и кноварь на масле, на масле на яичном и златом писали за клею месть, масло и яичное прибавливали к золоту понемногу.

Scribes of old wrote in gold with cinnabar under the gold, adding[10]мести, метать meaning iacere, iactare, “to throw”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkogo jazyka po pis’mennym pamjatnikam. Vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 129. egg and cinnabar to the oil as a glue, then wrote in egg and gold over this oil as a glue, adding a little of the egg and oil to the gold.

Another artisan from the 16th-17th centuries, among the various rare notes on the techniques of book writing which attest to his great knowledge of this subject, writes about the creation of paint using eggs, meaning by this the egg yolk, and describes its preparation. On the subject of egg whites, ne notes:[11]Separate the yolk from the egg white, and return it to the egg shell, from which the top quarter or sixth has been removed, and set it in a wooden or wax base, break the contents with a spatula, add water to the top, add salt “as needed,” stir again, and set it by a window. If you intend to use up all the contents at once, then do not add salt. The Anon. bernensis in one exceptional case, specifically for writing on poor quality parchment, such as that made from Burgundian sheep, also indicates to use egg yolk diluted with water instead of egg white.

Иже что от письма не под олифу, да растворяет на белке.[12]Manuscript VIII.

For if that which was written be not under oil[13]jeb: olifa mentioned here was linseed oil used as a topcoat over paintings and icons, as a preservative., dissolve it in egg white.

Here, too, we find an interesting note about the great ease of use of paints which have been prepared using natural gums, compared those prepared with egg, which is most likely the reason why scribes stopped using the latter:

И иже растворенных красок яйцем, что остается от письма, паки тех нельзя во ино время растворяти и писати, но искинути вон. Комеди же льзе и второе растворити и третие, нужды ради.

And if there is any paint dissolved in egg which remains from your painting, then it cannot be dissolved and used to paint at a later time, and it must be thrown away. Paint made with gum may be dissolved and used a second and third time, if need be.

We find directions for the preparation of egg whites for various uses relatively frequently. Nikodim Siysky describes this work in the following way:

Яичный белок один токмо[14]jeb: тъкъмо = токмо, meaning только, “only”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkogo jazyka po pis’mennym pamjatnikam. Vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1912, p. 1044. в чистом сосуде лопаткою убьет гораздо довольно, и егда понаустоится, кроме пены процедить сквозь плат в сосуде чист.[15]Manuscript XXIV.

Thoroughly beat a single egg white in a clean vessel with a spatula, and when it settles back down and it is without foam, filter it through a cloth into a clean vessel.

Serbian scribes in the 17th century did approximately the same thing, and this “preparation”(??) (“вотка”) was named by Russian artisans “egg oil” (масло от яйца), from whence, it seems this “oil” containing egg white entered into Russian collections.[16]Serbian scribes sometimes left ground cinnabar to stand on egg whites “дондеж въсмрьдит се и очрьвивет” (“until it stinks and turns red”) (jeb: очьрвити meaning обагрить, “to turn crimson”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol II., p. 849), and then they would paint with it. Manuscript IX. This grinding of cinnabar and lazuli into egg whites for illumination is preserved in several recipes in the form of relics from earlier centuries. These egg whites containing ground pigments were moistened with water and mixed with gum.

In an 18th century manuscript we find “Painting with pigments dissolved in gum” (“Роспись краскам, кои на камеди растворяются”). These pigments included the following:

зеленая желчь, бакан немецкий, ярь веницейская, медянка брусками, бакан веницейский, сурьма: растворять на камеди с водою.

Green bile, German crimson, Venetian yar’, verdigris from bars, Venetian crimson, kohl: dissolve in gum with water.

Afterwards, it says that these pigments may also be mixed with egg yolk.[17]Manuscript XLII. This list has in common with Theophilus’s only that they both exclude (perhaps incidentally, as this list was generally quite short for its time) the blue pigments, red lead, and white lead.[18]Petrus de S. Audemar, an artisan from Northern France in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, points to egg white as a binder for verdigris (Rus. ярь-медянка) (Merrit, p. 151). Cennino Cennini instructs one to paint with this pigment on parchment or paper using egg yolk (p. 56). Russian artisans seem not to have been completely overly concerned about copper oxides, which Western artisans found so scary. Their danger doubtless existed, as can be easily verified by looking through medieval manuscripts. As an example, we might single out from the earliest parchments a Gospel from 1199-1200 from the collection of the Bishop Porphyry,[19]Publichnaja biblioteka, F, p. I, no. 82. where in a miniature of the Evangelist John, all of the places which were covered in glazed copper paint have been badly damaged. The paint has almost completely disappeared in some places. The parchment underneath has taken on a glassy appearance, become fragile, and in some locations has completely crumbled. The same is also seen, although to a significantly less degree, on a page of the Serbian Miroslav’s Gospel (12th century). The green here is of a different character, darker, but has acted likewise upon the parchment, which has already cracked in one location around 1 cm long.[20] Publichnaja biblioteka, F, p. I, no. 83. On paper manuscripts, the same process can at least be seen in the miniatures of a Tetraevangelion from the 15th-16th centuries,[21]Publichnaja biblioteka, F, p. I, no. 581. where the light green copper paint, which has completely disappeared in some places, had a destructive effect on the paper.[22]The same effect can also frequently be seen on Georgian paper manuscripts from the 15th-16th centuries, and sometimes on earlier parchment manuscripts. Light blue pigments also sometimes turned out to be disastrous for manuscripts, but such occasions are significantly rarer. Its destructive effect, as with green, was most likely predicated on the presence of copper. A good example of this is the Galician Gospel from the 13th century.[23]20 The relatively dark blue (possibly azurite) acted so powerfully upon the parchment, that it became brittle beneath the paint and in places there are now cracks.

Based on our fragmentary evidence, it is difficult to imagine in full sequence the work of the artists who artfully decorated books with capitals and headpieces (Rus. заставка, zastavka, or заставица, zastavitsa),[24]The word заставка can be found as early as the Russian Arkhangel’sk Gospel of 1092. In it, under one of the headpieces, is written “This is a nice headpiece” (“люба заставице”). Its use in Russian passed through a series of centuries and is used among Old Believers to this day. The verb заставить (Rus. zastavit’) in the sense to decorate or adorn can be read in the notes of the Serbian Miroslav Gospel from the late 12th century (“заставить сие евангелие златом” – “decorate this Gospel with gold”), Sobolevskij, A.I. Slavjanorusskaja paleografija. St. Petersburg, 1908, p. 72). frequently very complex in design and color, as well as technically perfect iconographic images (Rus. лицевое изображение, litsevoe izobrazhenie, “facial art”). This is made all the more difficult by the fact that, undoubtedly, over the course of its many centuries of prosperity, it could not possibly have seen so monotonous. At the same time, artisans used in their book decorations an entirely varied set of technical skills and training. Sometimes this work was attempted by an ordinary scribe who owned nothing but his own writing technique. Having made a mechanical “translation” of a capital letter or even sometimes of a miniature that was complex in design, he colored it with ink, cinnabar or another paint with the assistance of a quill, filling in the gaps between the outlines with some kind of hashmarks.[25]See, for example, the miniature on the reverse side of the first page of a parchment Apostle Book from the 14th century. Publichnaja biblioteka, Q, 1, No. 5 – an architectural ornament in the form of a five-domed church, painted in the “animal” style. The gaps were filled in with azure using a quill. Sometimes the technical perfection of a work and good artistic taste reveal the head of an experienced specialist of book pictorial art.[26]Sp. Bogosluzhebnyj na krjukovyjkh notakh, 1573. Publichnaja biblioteka, Q, I, no. 898. It can also occur that the technique of ornamentation, especially in iconographic images, makes one assume it was authored by a master iconographer. Quite a few direct indications survive that professional iconographers were engaged in the production of illuminations.[27]See for example a 14th-15th century Gospel from the collection of F.A. Tolstoy, Publ. bibl., F, p. 1, no. 21. In addition to five exquisitely painted miniatures on separate pages in iconographic technique showing Christ and four of the Apostles, there are also headpieces which were at least in part painted by iconographers. A direct indicator of the work of an iconographer is found, for example, in a postscript to a Gospel from 1507 (Publ. bibl., Pogodin collection, No. 133, p. 3758): “The black writing was written by a calligrapher, while the gold was written by Mikhaylo Medovartsev, the Evangelists were written (painted) by Fedosiy Zograf, son of Dionisiy Zograf.” There are especially many such indicators related to books from the 17th century. It is known, for example, that the profusely illustrated manuscript Soulful Medicine (Душевное лекарство), preserved to this day in the Armory of the Moscow Kremlin, was painted in 1770 by iconographers from the Trinity-Sergiev Monastery (Uspensky, A. Tsarsk. ikon., vol. 1, p. 88). There too we see the names of the royal painters who “celebrated” (Rus. знаменить) and decorated with paint a book of the Life of St. Basil the Younger (p. 83). One of these, Fyodor Matveev, wrote a humorous book in 1670 for the “little” princesses (p. 178). In extremely important cases, the decoration of books involved the participation of several specialized painters. In 1673 the Ambassadorial Order of the Royally Appointed Painters (“Посольский приказ царскими жалованными живописцами”) compiled a book about the coronation of Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich: Ivan Maksimov painted the “faces” (Rus. лица, litsa, in iconography, any part of the body not covered by clothing), Sergej Vasil’ev Rozanov painted everything “up to the face” (Rus. доличное, dolichnoe, an iconographic term meaning the clothes, architecture, etc.), Fyodor Yur’ev painted the “vegetation,” and the gilding and silver were done by the gold-writer Grigorij Blagushin “with his comrades.” (These paintings were published in 1856 by the Commission for the Printing of State Documents of the Primary Archival Ministry for Foreign Affairs, as described by Uspenskij, A., vol. I, p. 191.)

The general order of work was as follows. For the reproduction of more complex compositions, they used drawings which had previously been prepared on individual sheets, or they were composed anew by the hand of an experienced “znamenschik” (Rus. знаменщик, “celebrator”),[28]Znamenschiki were special artisans who drew up the designs and inscriptions for various types of artistic works, embroidery, works in metal, and illuminations. Well known, for example, were the Gomulin brothers: Ivan Il’ich (first half of the 17th century), a znamenschik of the state silverworks, and Andrey (second half of the 17th century), znamenschik of the State Artisans’ Workshop (Troitskij, B. Slovar’ master., khudozhnik. i t.d., p. 47). See also Solovey, Ivashka (from Rovinsky’s Ischislenie russkikh ikonopistsev), and others. or by the scribe himself, or more often they were mechanically copied from another manuscript or from pre-prepared “translations,” “exemplars,” and “likenesses” (Rus. сколки, “chips”), of which scribes and these specialists always maintained stock.

There were several methods for taking such samples and reproducing them onto the proper spot on the page. One of the best known was through the use of ink mixed with “garlic potion,” that is, garlic juice evaporated to a thick syrup. A drawing carried out using this concoction and lightly moistened could provide several imprints onto sheets of paper that were pressed against it. In a northern-Russian manuscript from the late 16th-early 17th centuries, calligraphically written by monastic scribes, we find a somewhat time-damaged direction for the use of this “garlic potion:”

Чеснок истолцы и процедь сквозь плат и наложи полы сосудец глиной и поставь в печь в вольное теп(ло), утопи в полы. Егда случится, что дело проходити, взем зелья на раковину кусик, и водою разтри и разведи, и потом чернило разотри с (зельем) и положи по мере соли крошки с две или три таж кистью проходи, и потом наложа бумагу, и дми гораздо на п. . . . хоженое, и отдоле рукою левою держи бумагу, другие ж ногтем гладь. И аще в деле зелье удастся, и сымет до седмижды единова пр. . . . .[29]Manuscript 8. All of the methods listed for making copies were also used for icon production.

Pound the garlic and strain it through a piece of cloth, and fill a clay vessel with it, and place it in the oven into liberal head, and stoke up the fire (?). Once the work has completed, take a bit of the potion on a shell, and add water and mix it, and then add ink to (the potion), and add two to three measures of salt, and use with with a brush, and then place paper (over it), and press(?) hard on … and with the left hand hold the paper, while with the other, smooth the surface with your fingernail. And if the potion is successful, it will work up to seven times for a single ….

If one did not wish to smudge the image, then one would first take a copy of it using a “window frame” (Rus. оконница, okonnitsa), that is, using the light which passed through paper which had been attached to a window, they would trace the outlines with the same garlic potion mixed with ink.[30]Manuscript XLII. Here too we find directions for preparing garlic potion which are similar to those mentioned above. Having mixed it with soot, the artisan chooses, however, not to add salt. See also manuscripts XLVIII and XXIII. The same method could also be used without ink. One 18th century master advises:

Уголь разтирать на плите и растворять на воде. Писать по черным гвентам и прикладывать на белую бумагу и притирать ногтем.[31]Manuscript XLII.

Grind charcoal onto your palette and mix it with water. Write using a black gvent (??) and apply it to white paper, and smooth it with your fingernail.

A drawing applied in this manner would of course leave a reverse imprint, but by repeating the imprint, one could obtain the direct image.[32]Copies using the light of a window frame and with the assistance of garlic juice (for oil paintings) are also described in the technology of a herminia (icon painting guide) from Mt. Athos. The same artisan knew how to use tracing paper, prepared by rubbing it with a mixture of soot and beef lard,[33]Manuscript XLII. as well as how to “capture a likeness” using finely-ground lime charcoal pounced onto an image which had been pricked along the contours with a needle, onto paper which had been placed below it.

In some 16th-century manuscripts, for example a Gospel from 1537 (Moscow Synodal Library, #62), a completely different technique for transferring large patterned headpieces, capitals, and titular lines of vyaz’ can be seen. These were first imprinted using embossing boards (Rus. обронная доска, obronnaja doska), and only then were filled in by hand with paint and gold (see by the previous catalog of this library, No. 742, 810, et.al.).[34]Simoni, P. K istorii obikhoda knigopistsa, perepletchika i ikonnogo pistsa. 1906. Footnote on p. 285. Karskij, E. Ocherki paleografii, p. 480.

The contours of unusually complex headpieces and capitals were sometimes filled out in paint, and then outlined in ink or cinnabar using a quill pen.

There are very interesting directions about how one should clean a quill for various types of writing and drawing provided by the 16th-17th calligrapher mentioned above, which we provide here in their entirety:

О пере. Достоит же перо чинити, к большему письму книжно пространно и тельно, к мелку ж мало, к знаменну по знамени, и к скорописно пространно ж. Срез же у книжных длее скорописнаго, у того ж сокращеннее. Разсчеп же у книжных и знаменна и скорописна твори в полы среза, аще тельно зело, аще ли жидко перо, и у того разсчеп твори не по срезу, но мал. У книжного большаго разсчеп твори подлее мелька вдвое. У книжных же конец кос на десно, у снаменных же на шуе, у скорописных впрям. И аще случится починити книжна ли знаменна, скрашеной стране самый мало, скорописна ж и с обоих. Аще ли раздвоится, срежи весь разсчеп и учини новой. И сие до зде.[35]Manuscript 8. Furthermore, in an article “Also on the pen” there follows a not-completely-clear description of a hollow nib quill filled from above with ink with the expectation that it was able to write an entire page. This was a prototype of the fountain pens that entered into general use in the early 20th century (Füllfeder). Also of interest is the same artisan’s admonishment about the storage of writing materials: “Store ink, cinnabar, resin, and your pencase with your quills in neither great warmth, nor in the cold, for they shall spoil in the warmth, and even more so from frost, and the pens will rot in their case from moisture in warmth.” (“Держати чернило, кин(оварь), камедь, перница с перем ни в тепле зельне, ни в студени, понеж от зельна тепла портится, наипаче от мраз, перьеж в пернице в тепле от воды гниет.”)

On the pen. The quill needs to be cleaned, extensively and thoroughly for large book writing, a little bit for small writing, for znamenny chant notation (Rus. знаменное, znamennoe) according to the size of the notation, and extensively for skoropis‘. The cut is longer for book hands than it is for skoropis’, where the cut is smaller. For book work, znamenny, and skoropis’, make a slit the length of the cut tip if the feather is very stiff, or if the feather is soft, then make the slit not the full length, but smaller. For book writing, make the slit twice as long. For book writing, cut the tip straight across, for znamenny angle it to the left, and for skoropis’, angle it to the right. And if one is cleaning a quill for a book or for znamenny, the cut side of the tip should be very narrow, while for skoropis’ both sides should be narrow. If one should break the tip, then cut off the entire tip and start anew. And that is everything.

For more complex compositions which involved gold, the gilding was done first. This most difficult operation requires a final polishing using a hard, smooth object which would not damage the paint. To achieve a known type of effects, paints were applied over the gold. The gilding was done using sheets of gold leaf or with powdered gold pigment (Rus. творёное золото, tvorjonoe zoloto, “prepared gold”). There is an opinion that gold pigment entered into use among the Russians only in the late 16th century.[36]Sychev, N.P. Instruktsija dlja opisanija miniatjur. Petrograd, 1922, p. 16. Nevertheless, it is quite certain that it was in use significantly earlier.[37]Preparation of powdered gold was described in our earliest collections, manuscripts from the mid-15th century. It can also be found used in illuminations from even earlier times.

The techniques for applying levkas[38]jeb: In icon-painting, levkas is a bright white layer of powdered alabaster, gypsum, or chalk painted onto a surface under gold, similar to gesso, and sanded smooth, which would reflect light and make the gold appear even shinier. (Rus. левкашение, levkashenie) under the gold, gilding the headpieces, and painting in gold, cinnabar, and other paints used in illumination have been described by us in articles on these matters. Information on these can and must be supplemented by study of our inexhaustible collections of works of the book arts, for the material and painting technique points of view. Such a study requires special preparation and methods. This will result in new material and new methods of judging both individual works, as well as of groups of works associated with known features.

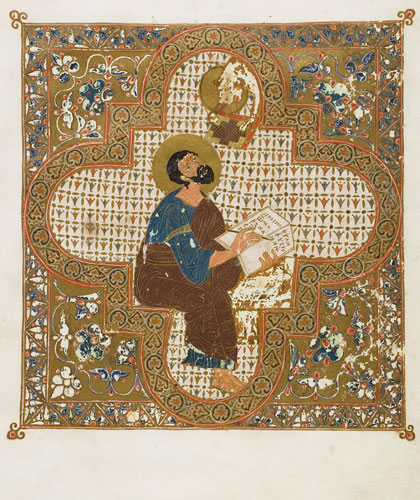

Arranging our material from a historical perspective, we are able to get a certain, as yet rather incomplete idea about the general process of development. Headpieces and capitals from the earliest manuscripts of the Ostromir Gospel (1056-1057), the Svyatoslav Sbornik (1073), the Mstislav Gospel (early 12th century), and the Serbian Miroslav Gospel (late 12th century) are characterized by the quite pure style of decoration from 9th-11th century Byzantine manuscripts. Its elements were primarily of a floral character, sometimes with the addition of images of peacocks, leopards, fish, or round, ruddy faces. Animal forms here still bear a natural character, with only slight signs of stylization.[39]cf. Sobolevskij, A. Slavjanorusskaja paleografija. St. Petersburg, 1908, p. 62. These decorations stand out for the beauty of their design and the variety of paint and gold. Gold was not uncommon in manuscripts of the Kievan and Galician periods. In addition to headpieces and capitals, these were also sometimes used to write entire texts, as in the Ostromir and Mstislav Gospels (circa 1117). A letter written entirely in gold from Grand Prince Mstislav to the Yuriev Monastery from 1130 has survived. We learn of a Gospel written in gold from the Khlebnikovsky Spisok, where it is written that Vladimir Vasil’kovich (died 1288), prince of Volhynia, “sent to Chernigov bishopric an Evangeliary written in gold.”[40]Under the same prince, there also was written the Service Book of Varlaam of Khutyn, where the headlines and initials were written in silver. This is a rare example of the use of silver in illumination, generally. Gold began to be seen less often from the 15th-17th centuries. Painting in gold was sometimes entrusted to especially skillful artists. For example, in the postscript to the Mstislav Gospel, two scribes are mentioned: Aleksa, who wrote in ink, and Zhaden, who wrote in gold.

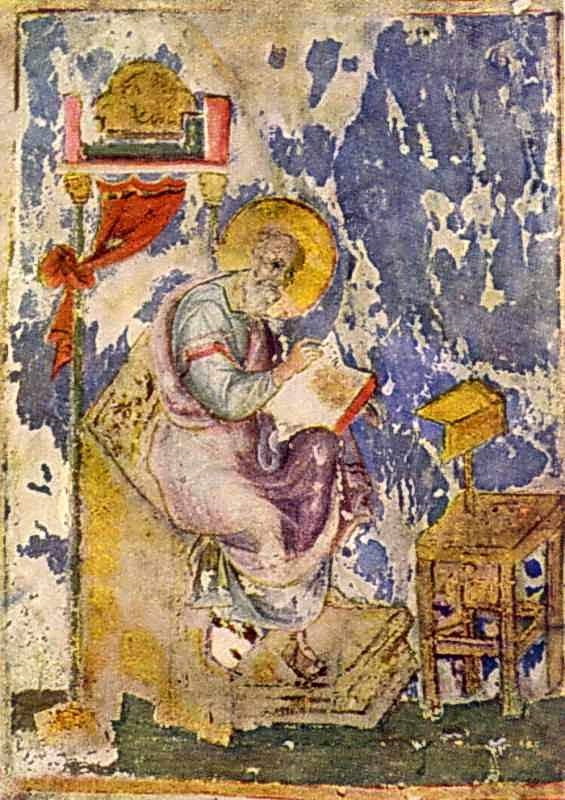

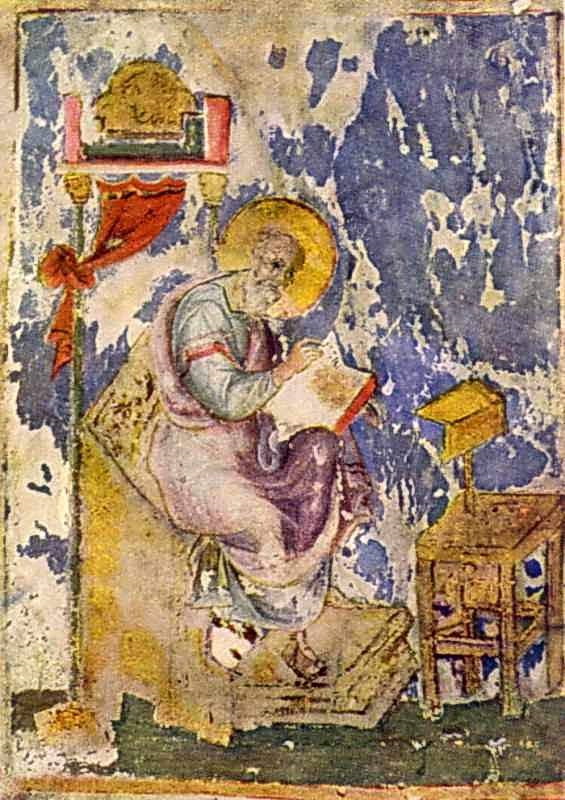

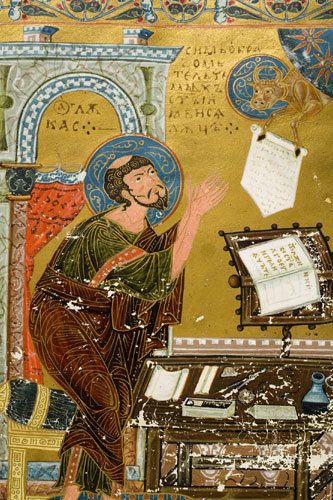

In the Ostromir Gospel, all of the headpieces and capitals were written primarily in solid, unmixed paint colors. The paints were mixed for portraits and vestments. These paints, based on what can be judged from sight, were as follows: three types of red can be made out: a colder shade of red, a pure but not very bright cinnabar, and an orange-red, possibly red lead (Rus. сурик, surik); a medium shade of purple (carmine (Rus. бакан, bakan), mixed with white lead (Rus. белила, belila)); a light blue, finely ground and pure, sometimes crumbling from the parchment, which appears to be ultramarine; yellow ochre (Rus. вохра, vokhra), quite pure and bright; a green, apparently compound pigment, a dark bottle-green shade, quite opaque. Comparing the pigments from the Ostromir Gospel with those from its contemporaneous Byzantine manuscripts, we observe a striking similarity of stylistic and technical means between them. In addition to gold, the 10th-11th century Byzantines typically decorated their manuscripts with cinnabar, some type of orange-red pigment, purple, ultramarine blue, an earthy yellow, and a muddy dark green. Professor A. Laurie, having studied the paints used by Byzantine illuminators, identified the orange-yellow as most likely an arsenic-based orpiment (possibly also containing red realgar), and the purple as Tyrian purple (from Murex snail shells), while the dark green he found to be as yet undefinable. As for the cinnabar and ultramarine, they can be in no doubt whatsoever.[41]Laurie, A.P. The Pigments and Mediums of the Old Masters. London, 1904, p. 59 and following. From among the other compounds, he identified a light sankir (Rus. санкирь, in icon-painting, an olive-brown shade used as a base color for painting faces) similar to a natural flesh tone, and a neutral shade of gray (Rus. рефть, reft’). The ink used on the miniatures was black, and different than that used for the calligraphy. White lead was used to paint accents over cinnabar, red lead, and carmine. The same accents over green were painted in yellow. This combination of underlying and accents, called dvizhki (Rus. движки, “movers”) are frequently seen also on headpieces from later period manuscripts. This can be explained by coloristic considerations. Gold pigment was relatively dull, and stuck well to the parchment. It was painted using some kind of durable binder, tinted with bright red paint. This paint appears to be the reason why locations which were covered in gold bled a yellowish-pink color through to the other side of the parchment.[42]Possibly a solution of cochineal bugs (Rus. раствор червца, rastvor chervtsa). See chervlen’ (Rus. червлень, aka черлень, cherlen’, which can mean either cochineal, or an earthy pigment of the same dark-cherry color). In places where the paint has crumbled away, it is possible to note the outlines of the drawing in a faint shade of pink.

jeb: Ostromir Gospel, 1056-1057, illumination depicting the Evangelist St. John. Image in public domain.

jeb: Ostromir Gospel, 1056-1057, illumination depicting the Evangelist St. Luke. Image in public domain.

jeb: Ostromir Gospel, 1056-1057, illumination depicting the Evangelist St. Mark. Image in public domain.

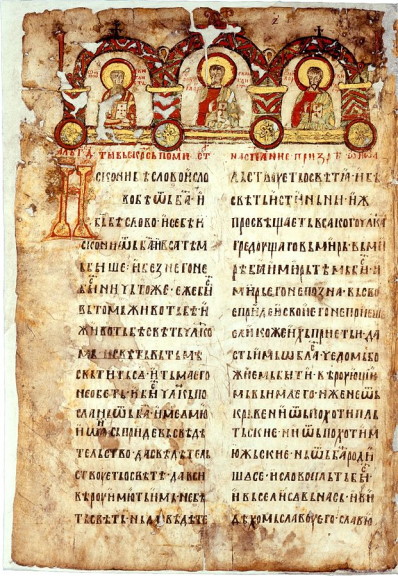

The pigments of the Serbian Mstislav Gospel, late 12th century, so far as one may judge based on a page stored in the State Public Historical Library of Russia,[43]Publ. bibl., F, p. 1, no. 83, in the collection of Bishop Porfiriy. were less sophisticated. The cinnabar is bright, finely ground, and has a glutinous sheen. The ocher is dull and uneven, from bright yellow to a dirty grey. The green pigment (yar’) is a matte dark green, peeling off in places, and has bled through the parchment to a brighter and lighter shade. The parchment is breaking down from it; in one place a tear can be noted around a centimeter in length. The white lead used on the faces and bodies of the figures is slightly glossy, and tinted to a flesh tone. The gold is silvery with quite indeterminate spots. Beneath it, on the opposite side of the page, there are always dirty grey spots.

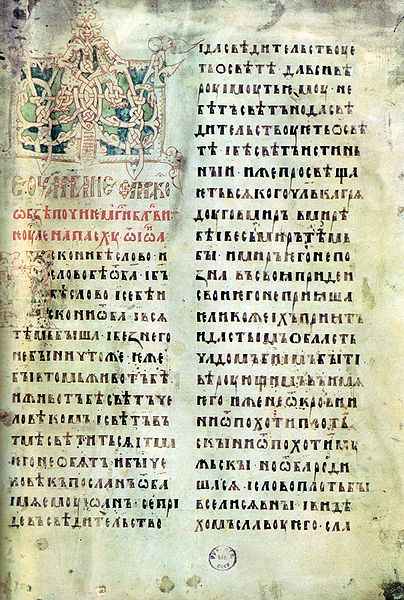

In the 12th century, the style of book illuminations in Russian manuscripts began to reflect some kind of external influence, contributing to new elements which were almost completely alien to the Byzantine style, and which became the so-called Teratological or Monstrous Style.[44]For more on this teratological style, cf. Schepkin, V. Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1920, p. 54. jeb: See my translation of this chapter on Slavonic Ornament. The form of monstrous animals and birds, intricately and complexly interwoven in ribbonlike bands, served as its primary motifs. Occasionally we also see interwoven human figures. From the earliest dated examples of this style, we might point to the Yuriev Gospel, circa 1120, and the Dobrilovo Gospel, 1164.[45]4Sobolevskij, Paleografija. p. 62. In the second half of the 13th century and throughout the entirety of the 14th century in Russian manuscripts, this style predominated and became quite monotonous. Their pigments were also uncomplicated. Typically these were combinations of cinnabar with dark blue, green, or yellow paint, without gold.[46]See, for example, 16th century manuscripts where, in addition to cinnabar and lapis, there was used also a yellow of an apparently different composition, one bright and quite opaque, in an Apostolary (Publ. bibl., Q, I, No. 5), and one dark and poorly opaque (ochre), in the Novgorod Psalter (Publ. bibl., F, p. 1, No. 3). Most commonly we find cinnabar with lapis, a combination believed to be of Novgorodian origin.[47]Sobolevskij, Paleografija, p. 65. Starting in the 14th century, in Novgorodian manuscripts, light blue and greenish paints began to be replaced by a calm blue-grey. Pskovian, West-Russian, Muscovite and Ryazanite manuscripts were transitional in their coloring. The latter were remarkable in that they retained the teratological style of ornament longer than the others, until the 16th century.[48]Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 65.

South Slavic manuscripts from the 12th and 13th centuries also often contained ornament in the teratological style. Their paints were slightly more varied.

In Ukrainian and Volhynian manuscripts, the older Byzantine influences were preserved much longer.[49]See, for example, the Peresopnytsia Gospel, from 1561, and the Zagorovsky Apostolary. The style of headpieces and capitals in Russian manuscripts from the 15th and early 16th century were directly dependent on Moldavian and South Slavic influences, which starting in the 14th century pulled away from elements of the teratological style, giving way to a preference for geometric forms, united sometimes with elements of a floral character. This style is typically called neo-Byzantine. Their paints became richer once more.[50]See for example a Tetraevangelion from the 15th century (Publ. bibl., Q, I, No. 896), with the following paints: cinnabar, lapis, ochre, some kind of bright yellow, light brown, most likely iron-based, and grey-green. The painting technique for illumination here became better and more complex. The coloration often gives evidence to the development of taste and the ability to produce excellent effects with little means.

As an example of the great illumination painting technique of the 16th century, let us look at the headpieces from the Service Book “on hooks” (Rus. на крюках, ??), written by a monk in the Makariev Hermitage in Kozelsk, in 1573.[51]Publ. bibl., Q, I, No. 898; headpieces on pages 4, 73, 216, 306, 535. Work began with the gilding using gold leaf over levkas in the form of short, wide rectangles. The gilding was scored with a sharp tool in order, it appears, to remove the excess levkas.[52]On the use of gold, see Chapters IV and VI. The levkas was applied to the page as a very thin layer. The area where the levkas was applied can be seen from the reverse side of the page. The gold is largely covered with multi-colored vegetative designs, surrounded by round lines. This ornament forms a continuous painted frame even outside the gilded area, becoming a light, delicate frame of thin writing. The paints are all opaque and are frequently compounds. The artisan only had a few pure colors available. Aside from white lead and “icon” black (that is, lampblack),[53]The text was written using a different ink. he worked in cinnabar of a medium brightness, a muted crimson-red carmine, and a quite bright yellow paint, apparently of good ochre. Nevertheless, the artisan was able to create, where necessary, the impression of light blue and green spots. He did this through artfully juxtaposing tones using composite colors: neutral gray, very bright gray, and a dark feather gray tinted with ochre to a greenish tone. The first of these was always lightened with white lead using a quill; the second was done using ochre. As a result, the effect of an exquisitely rich and pleasing-to-the-eye coloration was achieved.

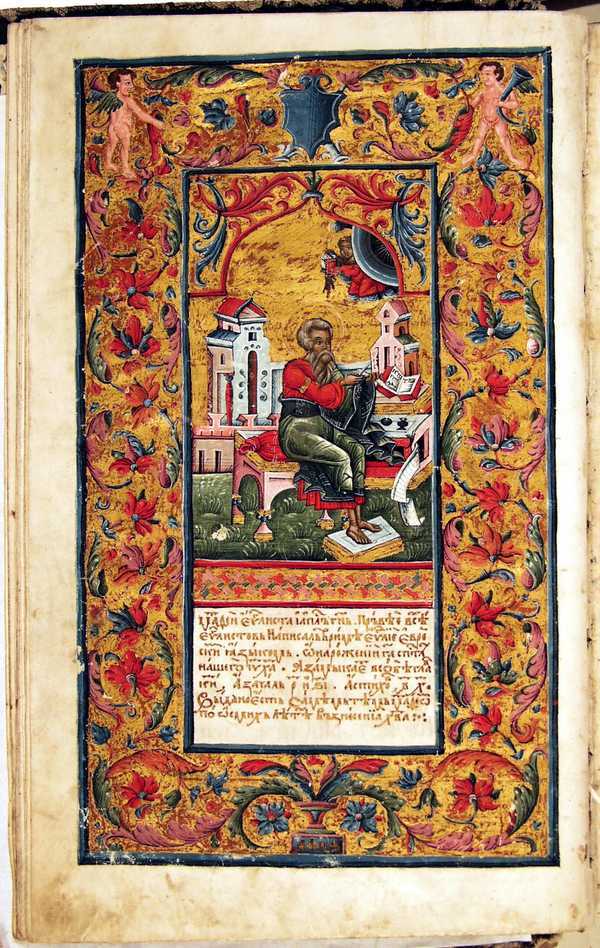

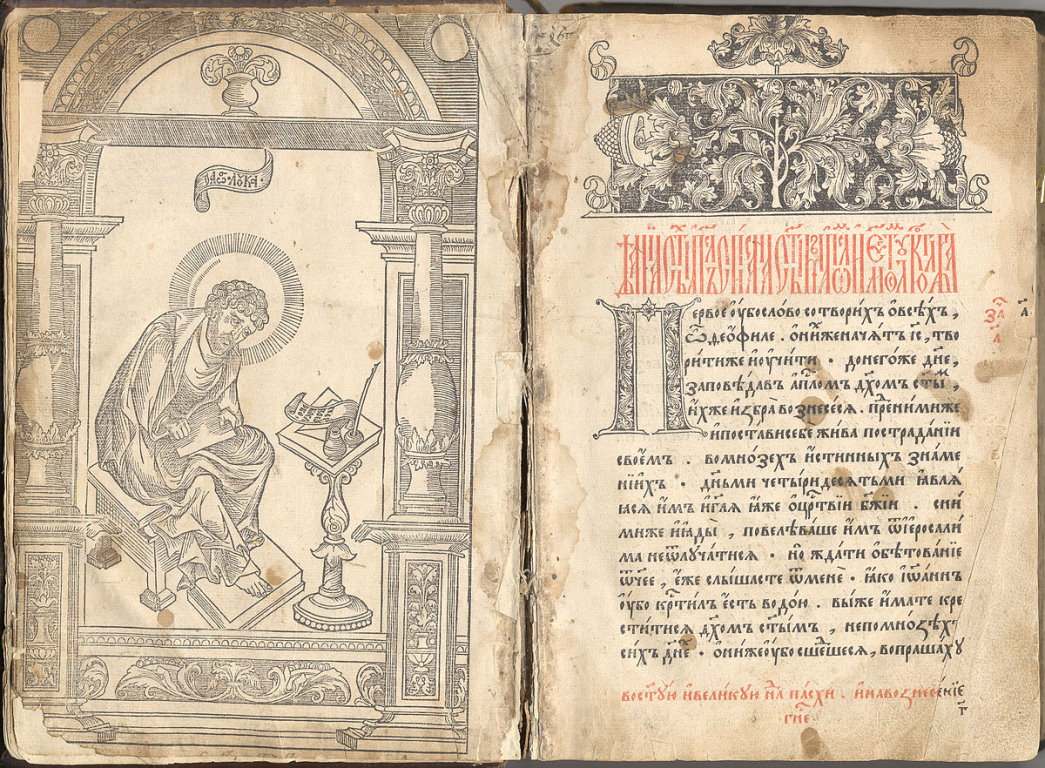

With the appearance of printed books for sale in the 17th century, the character of manuscript headpieces and capitals strongly changed, under the influence of changes in tastes in Western Europe. In the 17th century, the so-called Black Letter (Rus. старопечатный, staropechatnyj, “old-printed”) style began to prevail, an echo of the German Renaissance, characterized by large stylized plants, flowers, and fruit. Starting in the second half of that century, Dutch-German-Polish influences created a particular heavy-handed, sometimes quite awkward Muscovite Baroque, which arrived here about 150 years after its inception in Italy. Starting in the 18th century, finally, echoes of the evolutionary process began to be heard on French soil, from Louis XV style, to the Empire style.[54]See Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 58 and following. This was reflected in the character of Russian illumination.[55]The French styles, incidentally, did not last sufficiently long to have a significant impact on the character of decorations in folk religious books, although they occupied a prominent place in the albums and other manuscripts of the more wealthy classes. Not only in stylistic but also in technological respects, book engravings influenced the work of book artisans, who often attempted to translate the technical peculiarities of engraving in metal and wood, and achieved this sometimes to complete the illusion, competing, it seems, with the sale of printed headpieces and frames to scribes which appeared in Moscow in the late 17th century.

jeb: Teratological headpiece on the first page of the Siysky Gospel, 1339. Photo in public domain.

jeb: Page from the Buslaev Psalter (Rus. Буслаевская псалтирь, Buslaevskaja psaltir’), dated to the mid-15th century. The headpiece and capital С (“S”) are in the Balkan and neo-Byzantine styles. Image in public domain.

jeb: Frontispiece and title page from the 1564 Acts and Epistles of the Apostles (Rus. Апостол, apostol), the first dated printed book in Russia. The ornament is in Black Letter style. Photo in public domain.

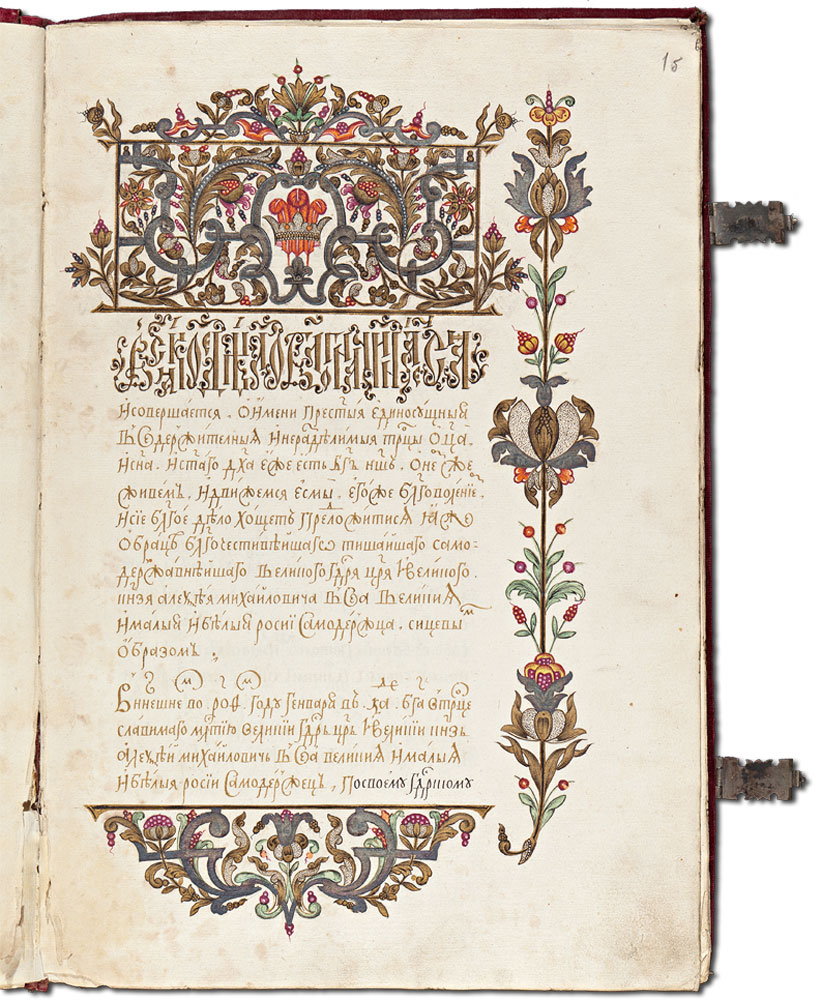

jeb: Example of Moscow Baroque ornament. Page from the Radostnyj chinovnoj spisok (“Joyful Bureaucratic List”) from the wedding of Tsar’ Aleksey Mikhaylovich, 1671. Photo in public domain.

As for the coloring of headpieces drawn in the engraved manner of the Black Letter style, there are two distinguished manners: an earlier one, with plants in black-on-white or white-on-black, with predominantly black lines and only a few in gold or cinnabar; and a later one, with multicolored markings of the same plant shapes, painted against a white, gold, colored, or black field.[56]Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 58.

Iconographic illuminations[57]The term “facial manuscript” (Rus. рукопись лицевая) is a medieval Russian term meaning an illuminated manuscript. in manuscripts, as generally in medieval Russian art, were less susceptible to external influences. Archaic Russian-Byzantine iconographic forms, although not as strictly retained as on icons, long remained dominant in illumination. Only starting in the second half of the 15th century in Russian miniatures did a certain shift toward Western influences begin to be seen. Changes in illumination techniques undoubtedly contributed greatly to this change in style, conditioned by the move from parchment to paper. Iconographic techniques which were fully suitable on slightly plastered (with levkas) parchment[58]As examples, see two gospels from the State Public Historical Library of Russia. The earlier of these is from the 14th century (F, p. 1, 15) and contains on the first page a somewhat damaged depiction of a writing evangelist; the second, from the late 14th or early 15th century (F, p. 1, 21) contains a depiction of the four evangelists and Christ, which is well preserved. It is interesting to note that the parchment in the top corner of one of the miniatures, which seems to have been defective, was replaced by an artist with glued-on paper; after it was plastered with white lead, the writing top the gesso became completely indistinguishable from the rest of the page. were less suitable on paper, although according to tradition it continued to be used occasionally on paper even in the 16th century.[59]For example, the miniatures in the Uvarov Paleya from the 16th century were painted in this manner, copied from a 14th century parchment manuscript.

Painting on paper required its own “watercolor” technique, and this method was assimilated by the Russian masters. In the 16th century, the paints used in miniatures were richer, and gold was used on crowns and for “light”. In the 17th century, they became simpler and more elementary in terms of their technology. In the second half of that century, they mainly boiled down to three colors, if one excludes the black which was used to paint almost only the outlines: red, green, and yellow. This manner of painting in three colors continued into the 18th century.[60]Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 80. Alongside this, in the second half of the 17th century, we also see miniatures with luxurious coloring, decorated in gold and silver even to excess.

As a typical example of popular inexpensive miniatures, strongly reminiscent of later popular painted printed items, we point to a Novgorod Facial Manuscript from the 18th century, from the library of Novgorod’s St. Sophia Cathedral,[61]Novgor. Sof. bibl., no. 1430, now in the State Public Library. Its spine has the inscription “Old Believer Illustrated Book” (“книга лицевая раскольницкая”). which was filled primarily with scenic images and has a scarcity of text. Its primary colors were approximately as follows: a rich cinnabar used for the text, while it was largely absent in illuminations,[62]In two places, horse tackle was painted in cinnabar using a brush. and was replaced with red lead; a green yar’, unevenly colored and sometimes noticeable on the reverse of the page; two yellows, one common dull ochre, the other lighter and brighter, possibly plant-based; a dirty, cloudy purple paint, insufficiently characteristic for plant-based carmine color, and possibly mineral-based, which was mixed into a dirty flesh-colored paint which was used to paint roads, bridges, and buildings. In addition to these, there were unsuccessful attempts to use a muddy, green-grey-light blue paint, which left behind dirty, uneven spots. The paints were applied to solid surfaces in blocks, shaded in places with a secondary application of the same or a slightly different shade.

This is a great example of the material squalor of Russian illuminators in the 17th and even in the 18th centuries. They often lacked light blue, pure pink or crimson, and bright yellow. Only in the late 18th century and early 19th century did they acquire carmine, Prussian blue, and other good foreign paints, which had long since entered into use by European artists.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | “De clared. Anonymus bernensis.” Quellenschr. f. Kunstgeschichte. Vol. VII. Wien, 1874. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Heracl., III, XXXI. |

| ↟3 | See the section on yar’ (Rus. ярь, a green pigment obtained through the oxidation of copper) in Chapter 7. |

| ↟4 | “Veride salsum no valet in libro.” (“Veride salsum should not be used in books.”) |

| ↟5 | See the section on yar’ in Chapter 7. |

| ↟6 | “Sucum gladioli, vel caulae, vel pori.” (“Juice of the iris, from either the stems or the pores.”) |

| ↟7 | Theophilus, Diversarum artium schedula. p. XXXIX. |

| ↟8 | Cen. Cen. p. X. |

| ↟9 | Manuscript no. XXXIII. Enumeration of manuscripts done by V.A. Schavinskij according to a book by P.K. Simoni; in a personal copy stored in the Institute of Historical Technology of the State Academy of the History of Material Culture, V.A. Schavinskij thus picked out each of the manuscripts which he used in his work. M. F. |

| ↟10 | мести, метать meaning iacere, iactare, “to throw”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkogo jazyka po pis’mennym pamjatnikam. Vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 129. |

| ↟11 | Separate the yolk from the egg white, and return it to the egg shell, from which the top quarter or sixth has been removed, and set it in a wooden or wax base, break the contents with a spatula, add water to the top, add salt “as needed,” stir again, and set it by a window. If you intend to use up all the contents at once, then do not add salt. The Anon. bernensis in one exceptional case, specifically for writing on poor quality parchment, such as that made from Burgundian sheep, also indicates to use egg yolk diluted with water instead of egg white. |

| ↟12 | Manuscript VIII. |

| ↟13 | jeb: olifa mentioned here was linseed oil used as a topcoat over paintings and icons, as a preservative. |

| ↟14 | jeb: тъкъмо = токмо, meaning только, “only”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevne-russkogo jazyka po pis’mennym pamjatnikam. Vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1912, p. 1044. |

| ↟15 | Manuscript XXIV. |

| ↟16 | Serbian scribes sometimes left ground cinnabar to stand on egg whites “дондеж въсмрьдит се и очрьвивет” (“until it stinks and turns red”) (jeb: очьрвити meaning обагрить, “to turn crimson”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol II., p. 849), and then they would paint with it. Manuscript IX. This grinding of cinnabar and lazuli into egg whites for illumination is preserved in several recipes in the form of relics from earlier centuries. These egg whites containing ground pigments were moistened with water and mixed with gum. |

| ↟17 | Manuscript XLII. |

| ↟18 | Petrus de S. Audemar, an artisan from Northern France in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, points to egg white as a binder for verdigris (Rus. ярь-медянка) (Merrit, p. 151). Cennino Cennini instructs one to paint with this pigment on parchment or paper using egg yolk (p. 56). |

| ↟19 | Publichnaja biblioteka, F, p. I, no. 82. |

| ↟20 | Publichnaja biblioteka, F, p. I, no. 83. |

| ↟21 | Publichnaja biblioteka, F, p. I, no. 581. |

| ↟22 | The same effect can also frequently be seen on Georgian paper manuscripts from the 15th-16th centuries, and sometimes on earlier parchment manuscripts. |

| ↟23 | 20 |

| ↟24 | The word заставка can be found as early as the Russian Arkhangel’sk Gospel of 1092. In it, under one of the headpieces, is written “This is a nice headpiece” (“люба заставице”). Its use in Russian passed through a series of centuries and is used among Old Believers to this day. The verb заставить (Rus. zastavit’) in the sense to decorate or adorn can be read in the notes of the Serbian Miroslav Gospel from the late 12th century (“заставить сие евангелие златом” – “decorate this Gospel with gold”), Sobolevskij, A.I. Slavjanorusskaja paleografija. St. Petersburg, 1908, p. 72). |

| ↟25 | See, for example, the miniature on the reverse side of the first page of a parchment Apostle Book from the 14th century. Publichnaja biblioteka, Q, 1, No. 5 – an architectural ornament in the form of a five-domed church, painted in the “animal” style. The gaps were filled in with azure using a quill. |

| ↟26 | Sp. Bogosluzhebnyj na krjukovyjkh notakh, 1573. Publichnaja biblioteka, Q, I, no. 898. |

| ↟27 | See for example a 14th-15th century Gospel from the collection of F.A. Tolstoy, Publ. bibl., F, p. 1, no. 21. In addition to five exquisitely painted miniatures on separate pages in iconographic technique showing Christ and four of the Apostles, there are also headpieces which were at least in part painted by iconographers. A direct indicator of the work of an iconographer is found, for example, in a postscript to a Gospel from 1507 (Publ. bibl., Pogodin collection, No. 133, p. 3758): “The black writing was written by a calligrapher, while the gold was written by Mikhaylo Medovartsev, the Evangelists were written (painted) by Fedosiy Zograf, son of Dionisiy Zograf.” There are especially many such indicators related to books from the 17th century. It is known, for example, that the profusely illustrated manuscript Soulful Medicine (Душевное лекарство), preserved to this day in the Armory of the Moscow Kremlin, was painted in 1770 by iconographers from the Trinity-Sergiev Monastery (Uspensky, A. Tsarsk. ikon., vol. 1, p. 88). There too we see the names of the royal painters who “celebrated” (Rus. знаменить) and decorated with paint a book of the Life of St. Basil the Younger (p. 83). One of these, Fyodor Matveev, wrote a humorous book in 1670 for the “little” princesses (p. 178). In extremely important cases, the decoration of books involved the participation of several specialized painters. In 1673 the Ambassadorial Order of the Royally Appointed Painters (“Посольский приказ царскими жалованными живописцами”) compiled a book about the coronation of Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich: Ivan Maksimov painted the “faces” (Rus. лица, litsa, in iconography, any part of the body not covered by clothing), Sergej Vasil’ev Rozanov painted everything “up to the face” (Rus. доличное, dolichnoe, an iconographic term meaning the clothes, architecture, etc.), Fyodor Yur’ev painted the “vegetation,” and the gilding and silver were done by the gold-writer Grigorij Blagushin “with his comrades.” (These paintings were published in 1856 by the Commission for the Printing of State Documents of the Primary Archival Ministry for Foreign Affairs, as described by Uspenskij, A., vol. I, p. 191.) |

| ↟28 | Znamenschiki were special artisans who drew up the designs and inscriptions for various types of artistic works, embroidery, works in metal, and illuminations. Well known, for example, were the Gomulin brothers: Ivan Il’ich (first half of the 17th century), a znamenschik of the state silverworks, and Andrey (second half of the 17th century), znamenschik of the State Artisans’ Workshop (Troitskij, B. Slovar’ master., khudozhnik. i t.d., p. 47). See also Solovey, Ivashka (from Rovinsky’s Ischislenie russkikh ikonopistsev), and others. |

| ↟29 | Manuscript 8. All of the methods listed for making copies were also used for icon production. |

| ↟30 | Manuscript XLII. Here too we find directions for preparing garlic potion which are similar to those mentioned above. Having mixed it with soot, the artisan chooses, however, not to add salt. See also manuscripts XLVIII and XXIII. |

| ↟31 | Manuscript XLII. |

| ↟32 | Copies using the light of a window frame and with the assistance of garlic juice (for oil paintings) are also described in the technology of a herminia (icon painting guide) from Mt. Athos. |

| ↟33 | Manuscript XLII. |

| ↟34 | Simoni, P. K istorii obikhoda knigopistsa, perepletchika i ikonnogo pistsa. 1906. Footnote on p. 285. Karskij, E. Ocherki paleografii, p. 480. |

| ↟35 | Manuscript 8. Furthermore, in an article “Also on the pen” there follows a not-completely-clear description of a hollow nib quill filled from above with ink with the expectation that it was able to write an entire page. This was a prototype of the fountain pens that entered into general use in the early 20th century (Füllfeder). Also of interest is the same artisan’s admonishment about the storage of writing materials: “Store ink, cinnabar, resin, and your pencase with your quills in neither great warmth, nor in the cold, for they shall spoil in the warmth, and even more so from frost, and the pens will rot in their case from moisture in warmth.” (“Держати чернило, кин(оварь), камедь, перница с перем ни в тепле зельне, ни в студени, понеж от зельна тепла портится, наипаче от мраз, перьеж в пернице в тепле от воды гниет.”) |

| ↟36 | Sychev, N.P. Instruktsija dlja opisanija miniatjur. Petrograd, 1922, p. 16. |

| ↟37 | Preparation of powdered gold was described in our earliest collections, manuscripts from the mid-15th century. It can also be found used in illuminations from even earlier times. |

| ↟38 | jeb: In icon-painting, levkas is a bright white layer of powdered alabaster, gypsum, or chalk painted onto a surface under gold, similar to gesso, and sanded smooth, which would reflect light and make the gold appear even shinier. |

| ↟39 | cf. Sobolevskij, A. Slavjanorusskaja paleografija. St. Petersburg, 1908, p. 62. |

| ↟40 | Under the same prince, there also was written the Service Book of Varlaam of Khutyn, where the headlines and initials were written in silver. This is a rare example of the use of silver in illumination, generally. |

| ↟41 | Laurie, A.P. The Pigments and Mediums of the Old Masters. London, 1904, p. 59 and following. |

| ↟42 | Possibly a solution of cochineal bugs (Rus. раствор червца, rastvor chervtsa). See chervlen’ (Rus. червлень, aka черлень, cherlen’, which can mean either cochineal, or an earthy pigment of the same dark-cherry color). |

| ↟43 | Publ. bibl., F, p. 1, no. 83, in the collection of Bishop Porfiriy. |

| ↟44 | For more on this teratological style, cf. Schepkin, V. Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1920, p. 54. jeb: See my translation of this chapter on Slavonic Ornament. |

| ↟45 | 4Sobolevskij, Paleografija. p. 62. |

| ↟46 | See, for example, 16th century manuscripts where, in addition to cinnabar and lapis, there was used also a yellow of an apparently different composition, one bright and quite opaque, in an Apostolary (Publ. bibl., Q, I, No. 5), and one dark and poorly opaque (ochre), in the Novgorod Psalter (Publ. bibl., F, p. 1, No. 3). |

| ↟47 | Sobolevskij, Paleografija, p. 65. |

| ↟48 | Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 65. |

| ↟49 | See, for example, the Peresopnytsia Gospel, from 1561, and the Zagorovsky Apostolary. |

| ↟50 | See for example a Tetraevangelion from the 15th century (Publ. bibl., Q, I, No. 896), with the following paints: cinnabar, lapis, ochre, some kind of bright yellow, light brown, most likely iron-based, and grey-green. |

| ↟51 | Publ. bibl., Q, I, No. 898; headpieces on pages 4, 73, 216, 306, 535. |

| ↟52 | On the use of gold, see Chapters IV and VI. |

| ↟53 | The text was written using a different ink. |

| ↟54 | See Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 58 and following. |

| ↟55 | The French styles, incidentally, did not last sufficiently long to have a significant impact on the character of decorations in folk religious books, although they occupied a prominent place in the albums and other manuscripts of the more wealthy classes. |

| ↟56 | Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 58. |

| ↟57 | The term “facial manuscript” (Rus. рукопись лицевая) is a medieval Russian term meaning an illuminated manuscript. |

| ↟58 | As examples, see two gospels from the State Public Historical Library of Russia. The earlier of these is from the 14th century (F, p. 1, 15) and contains on the first page a somewhat damaged depiction of a writing evangelist; the second, from the late 14th or early 15th century (F, p. 1, 21) contains a depiction of the four evangelists and Christ, which is well preserved. It is interesting to note that the parchment in the top corner of one of the miniatures, which seems to have been defective, was replaced by an artist with glued-on paper; after it was plastered with white lead, the writing top the gesso became completely indistinguishable from the rest of the page. |

| ↟59 | For example, the miniatures in the Uvarov Paleya from the 16th century were painted in this manner, copied from a 14th century parchment manuscript. |

| ↟60 | Schepkin, Paleografija, p. 80. |

| ↟61 | Novgor. Sof. bibl., no. 1430, now in the State Public Library. Its spine has the inscription “Old Believer Illustrated Book” (“книга лицевая раскольницкая”). |

| ↟62 | In two places, horse tackle was painted in cinnabar using a brush. |