Today’s post is a continuation of my translation of Russian Historical Costume for the Stage, a book written in 1945 by N. Gilyarovskaya. This work has extensive research into historical clothing from the Kievan Rus and medieval Moscow periods, with many source images. Part I provided an overview of medieval Russian history and dress for the stage (see my translation in an earlier blog post, here: https://rezansky.com/2019/10/russian-historical-costume-for-the-stage-part-i/). Part II concentrates on describing various types of clothing, with a multitude of images, and provides some general guidance on how to construct them. Part III (appendices) includes an overview of period fabric that was used in Rus’ in medieval times, as well as a helpful glossary of obscure medieval Russian terms.

Some of the recommendations are obviously directed more toward creating the impression of medieval outfits, rather than historical authenticity, and it is important to remember that the work was published in the Soviet Union immediately following World War II, which understandably influenced the availability of fabric options. But, the pictures and the descriptions provide useful information for the SCA researcher, assuming the recommendations about recreating items for the stage are taken with a grain of salt. As with many sources on the medieval period, SCAdians should take the good, laugh at the bad.

Russian Historical Costume for the Stage: Kievan and Muscovite Rus’

A translation of Гиляровская, Н. Русский исторический костюм для сцены: Киевская и Московская Русь. Москва-Ленинград, 1945. [Giljarovskaja, N. Russkij istoricheskij kostjum dlja stseny: Kievskaja i Moskovskaja Rus’. Moscow-Leningrad, 1945.]

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here (note, requires a .djvu file reader):

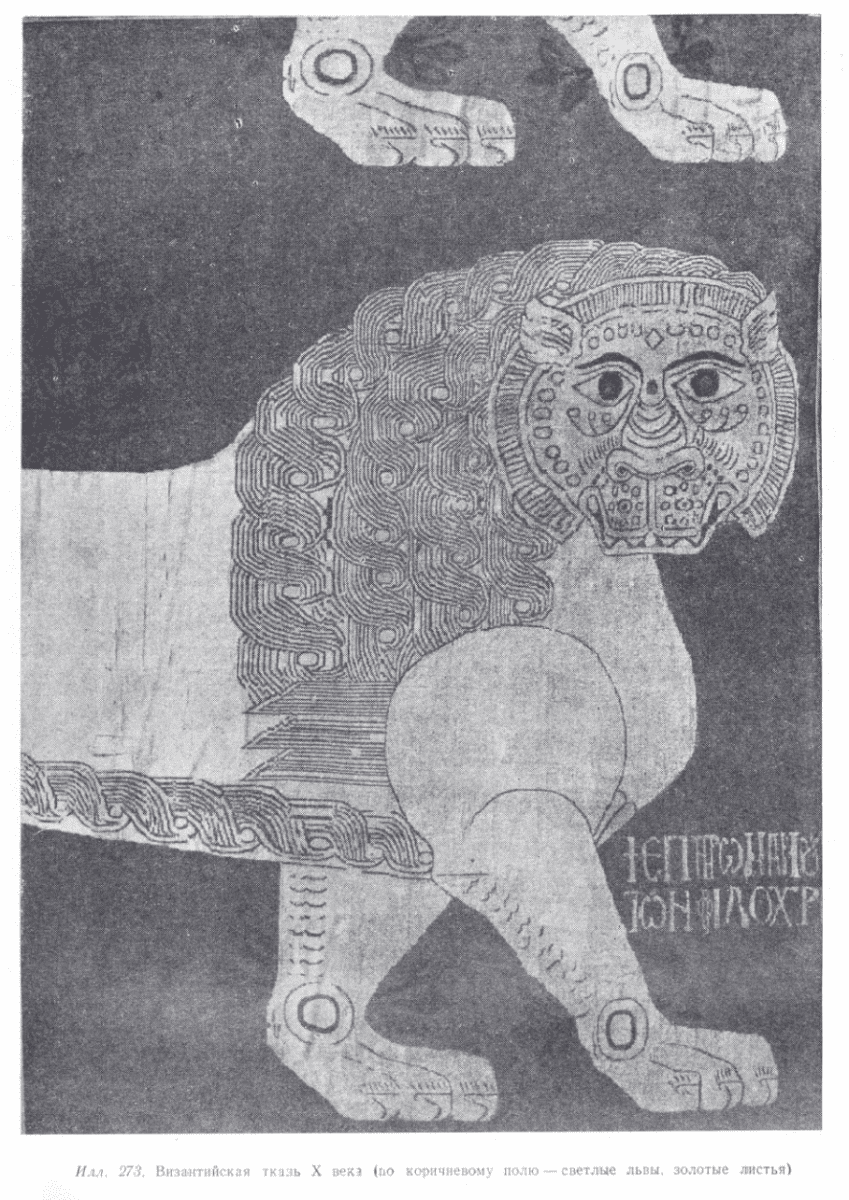

Русский исторический костюм для сцены: Киевская и Московская Русь. Where possible, I have replaced the black and white source images in the original with color images found online. Click on the image thumbnail to open the image full screen in the lightbox; from there see the “i” button in the lower left to view any additional notes Giljarovskaja may have given about that image.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This work also contains an extensive glossary below; see the table of contents.

This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

Collected by N. Gilyarovskaya, with assistance from members of the Academy of Sciences S. Bogoyavlenskij, N. Vorob’ev, and O. Gapanova.

State Publishing House “Iskusstvo”, Moscow/Leningrad, 1945.

Introduction and Part I

For the introduction and Part I, see my translation here:

Russian Historical Costume for the Stage: Kievan and Muscovite Rus’, Part I

Part II

Practical Implementation of Russian Historical Costume for the Stage

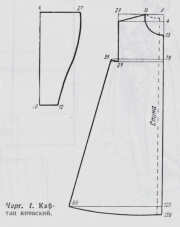

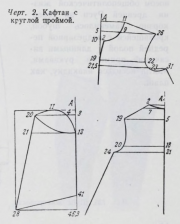

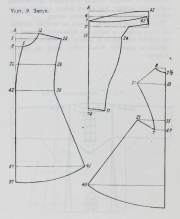

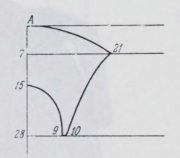

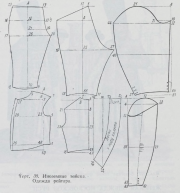

A Note on Measurements

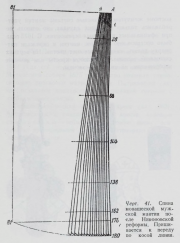

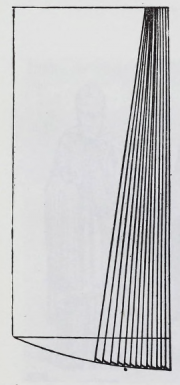

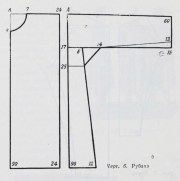

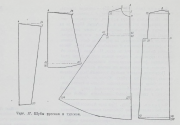

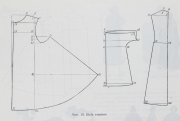

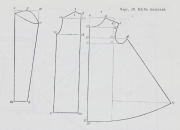

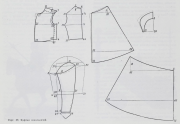

The measurements in the diagrams are made based on a sliding scale system. In this system, the pattern is drawn based on the chest measurement. Measure the circumference of the chest, then divide by two. This “half of the chest circumference” is then divided by 48. The units displayed on the diagrams are equivalent to this 1/48th of half the chest circumference. For a medium figured person (48cm), it is possible to use these measurements as centimeters. For figures of other sizes, 1/48th of the half-chest measurement will be proportionally larger or smaller.

The patterns always start with a vertical line, the upper end of which is marked with the letter “A”. Horizontal lines originate to the left or right from that vertical line.

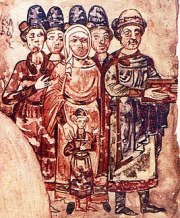

An Early Depiction of the Rus’

Among the scarce information about the peoples who lived on the land between the Dneipr and Volga Rivers, a picturesque depiction of these ancient Rus’ is given by the 10th century Arab traveler Ahmed Ibn Fadlan. Ibn-Fadlan was the Rus’ who traveled on business to the king of the Khazars, and attended the burial of a Rus’ nobleman.

Ibn Fadlan writes that he had never seen people with better physique: “They are like palm trees, rosy and beautiful. They wear no jackets or caftans, but only cloaks, covering one arm and leaving the other free. Each was armed with an axe, a sword and a knife. Their swords are flat, with grooves, and Frankish” (European).

Women wore on their necks rows of beads, the number of which indicated the wealth of their husbands. One row of string of beads corresponded to 10,000 dirhams. The Rus’ particularly valued green ceramic beads.

Having observed a funeral rite, Ibn Fadlan noted that the deceased man wore trousers, leg wraps (a kind of stocking without soles), shoes, a jacket, a brocade caftan with buttons, and a hat of brocade and sable.

Types of Medieval Russian Clothing

Kievan Caftan

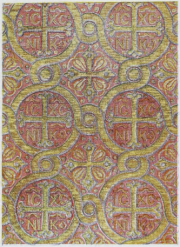

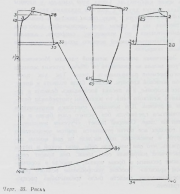

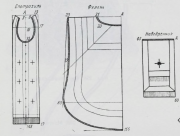

[Illustration 134; Diagrams 1 and 2. See also Illustration 4.]

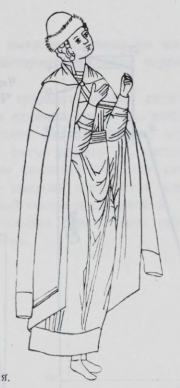

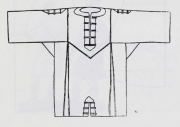

Fitted with the same straight armhole for both men and women. The difference is in the length and in the sleeves. For women, this served as an outer garment. The sleeve was wide, such that from under it would be seen an embellished undershirt sleeve. Men wore a cloak or korzno over this caftan.

Note: Given that, from a modern point of view, female clothing constructed with a square armhole appears a bit baggy, for the stage you may wish to create it with a round armhole [Diagram 2].

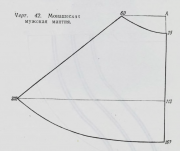

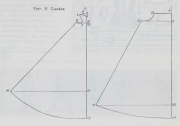

Korzno

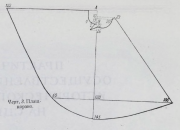

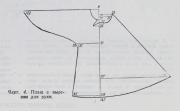

[Illustrations 134 and 135; Diagrams 3 and 4]

A cloak worn over the left shoulder and fastened on the right shoulder with a buckle or clasp. If the korzno was made of heavy fabric such as brocade, then a cutout was created to free the left arm.

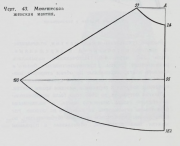

Novgorod Shuba

[Illustration 136; Diagram 5]

With the transfer of the general political life of medieval Rus’ to the north, the korzno was replaced by the shuba, sewn with a cropped front and long, straight hanging sleeves. It was able to be worn over the shoulders like a cape.

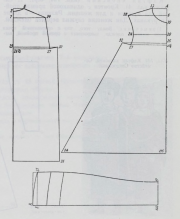

Shirts and Pants

A major component of Russian clothing since ancient times has been pants and shirts, preserved to modern day almost unchanged. After the Tatar invasion, the opening of the collar, located in medieval Russia in the center of the chest, moved to the left side (the so-called kosovorotka), and shirts which previously extended to the knee became shorter.

Shirts [Illustration 137; Diagram 6] were sewn from a variety of material: from homespun canvas, block-printed fabric, and calico; the lining at the chest and on the back were attached to the shirt by red thread. Gussets were inserted at the armpit, typically of red color. In general, red has long been a beloved color of the Russian people.

The pants and shirts used by peasants as everyday clothing were used by the upper classes as underclothes. Such shirts were sewn from thin linen and trimmed with red taffeta which was sewn to the lower hem, at the armpit, at the end of stitches, and as button plaques. The shirt was worn untucked over the pants, and were tied with a thin belt or colored cord. In private, these shirts could also be worn as outerwear, that is, over an undershirt. In these cases, the shirts were embroidered with red silk and gold decorated with various trim. Richly decorated keyhole collars or necklines decorated with pearls were attached to the shirt with small buttons or hooks. The collars were straight, 2-3 fingers wide, and typically fastened buttons that were metallic or covered with silk, sometimes decorated with precious stones or pearls. For the stage, shirts should be richly decorated and of colored silk.

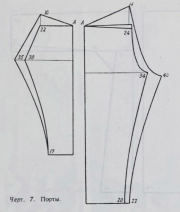

Pants were made from the same kinds of fabrics, or sometimes from cotton, and tucked into shoes or legwraps. Pants worn as underwear were sewn from thin linen. Over these linen pants [Illustration 138; Diagram 7], the wealthy would wear an outer pair of pants made from silk, broadcloth or brocade. A boyar’s pants might be made from gold or samite on a taffeta lining, with taffeta trim. Pants could also be made for warmth (fur-lined, or made from quilted cotton). Pants for children were sometimes made with feet.

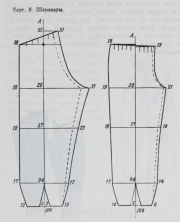

For the theater, it is convenient to create pants in the form of sharovary (harem pants) [Diagram 8], but this is incorrect: they had their own fashion. If pants are being made from brocade or silk and are going to be tucked into boots, then sew on a lower border of cotton in order to avoid rapid wear.

Zipun

[Illustration 139; Diagram 9; pl.: zipuny]

A tight-fitting, almost skin-tight caftan, worn over a shirt. The sleeves were narrow and of normal length, closed using 4-8 buttons. Zipuny were also sewn with sleeves of alternate fabric, or with no sleeves at all. Zipuny were usually knee-length, or sometimes shorter. The width of the hem was around 210 cm [82 inches]. Boyars would wear zipuny as under clothing. Zipuny were sewn with a taffeta lining, and with trim of brocade, or of fur for warmth. The zipun had a standing collar, sewn or buttoned to the zipun so that a given zipun could be worn with different collars. The collar was sometimes decorated with pearls. The front was fastened using “push-through” buttons, that is, using buttonholes rather than buttonloops (such buttonholes were seen only in the 17th century).

It is possible that zipuny were worn without a belt. Peasant zipuny were made of coarse cloth. They were worn by both men and women. The pattern for a zipun can also be used for two other forms of peasant wear: the azjam and the sermjaga [Illustration 140].

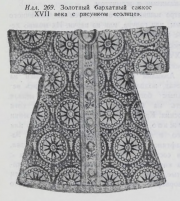

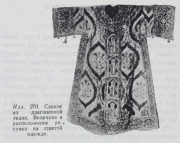

Caftans

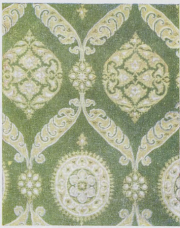

Caftans were one of the most common forms of Russian clothing, and came in many varieties. Caftans were worn over a zipun, which it resembled in cut, but had longer sleeves; the excess sleeve was gathered above the hand. The caftan came in various lengths. Some caftans (starting in the 17th century) had tall standing collars which covered the nape and were called kozyry. The outer side of the kozyr’, made of satin, velvet or samite, was embroidered with silk, gold and silver thread and decorated with pearls and precious stones.

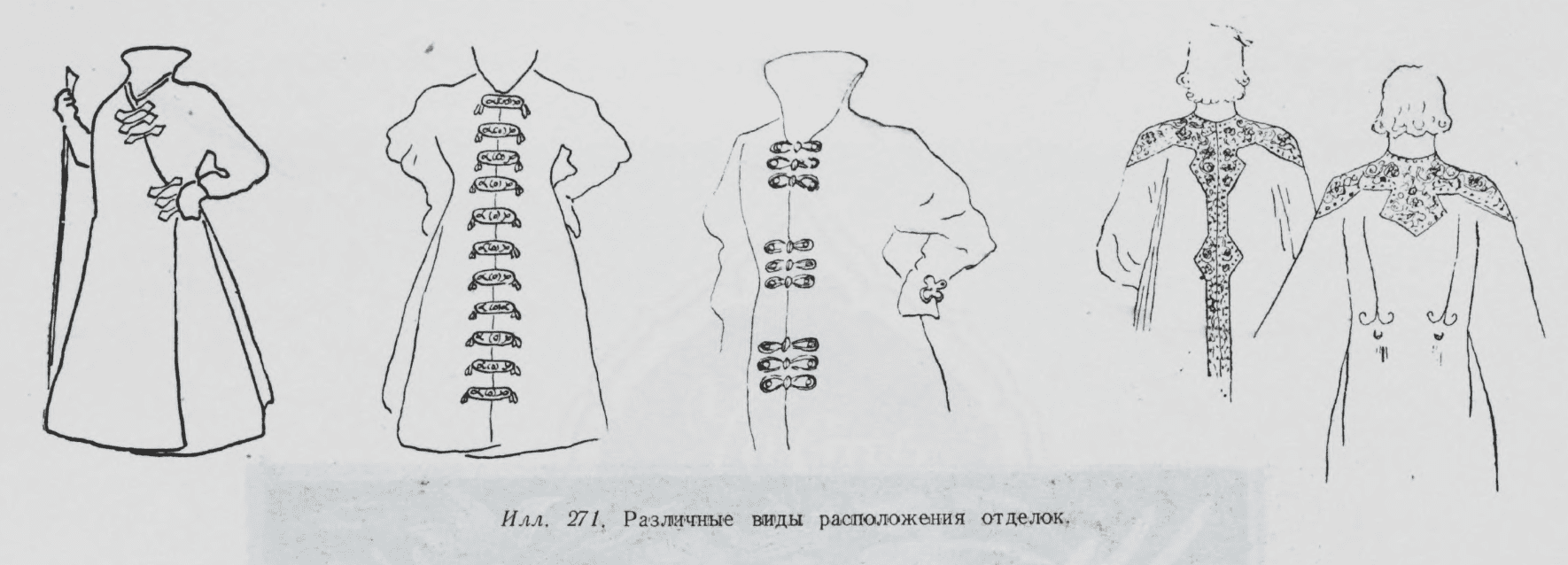

Caftans were made from various kinds of fabric: townspeople primarily wore cotton, merchants wore broadcloth, and boyars and nobles wore silk, brocade or velvet. Caftans were edged in various colors of braid, gold braid or galloon, which was called “lace”. The front of the caftan was fastened using buttons and loops, which were often long and decorated with tassels. The sleeves were gathered at the wrist. They did not have pockets; instead, they used hanging pouches called kality.

Boyars wore caftans as house wear. Outdoors, only younger men would wear caftans; older men would wear a ferjaz’, okhaben’ or shuba over their caftan.

There were various types of caftans, for example:

Caftan with a kozyr’ collar [Illustration 141, using the zipun pattern, Diagram 9]. This was the most common type of Russian caftan used for productions at the Moscow Art Theater and has become stereotyped.

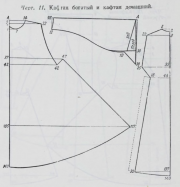

Rich caftan [Illustration 142, Diagram 11]. A green velvet caftan with silver button loops, worn in private.

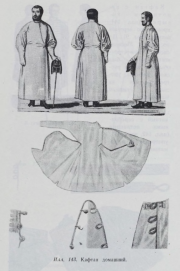

House caftan of a famous boyar, of silk without decoration [Illustration 143, Diagram 11]. Such a caftan might have had fur trim.

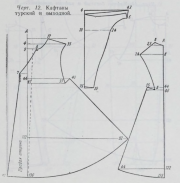

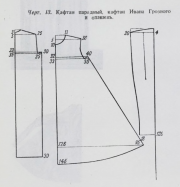

Turkish caftan [Illustration 144, Diagram 12]. A long outfit with a small standing collar, without button loops. The right panel passed over the to the left and was fastened on the left side.

Travel caftan [Illustration 145, Diagram 12, sewn like the Turkish caftan]. Worn over a zipun, worn either buttoned up or wide-open. The caftan was fitted close to the figure over the upper torso. Sleeves could be either long or short. This caftan was sewn from light-weight silk fabric with a lining and with trim. Gold or silver braide was used as decoration.

Formal caftan [Illustration 146, Diagram 13] made from very rich Kyzylbash brocade, without any decoration. It appears to be fastened using a clasp at the collar.

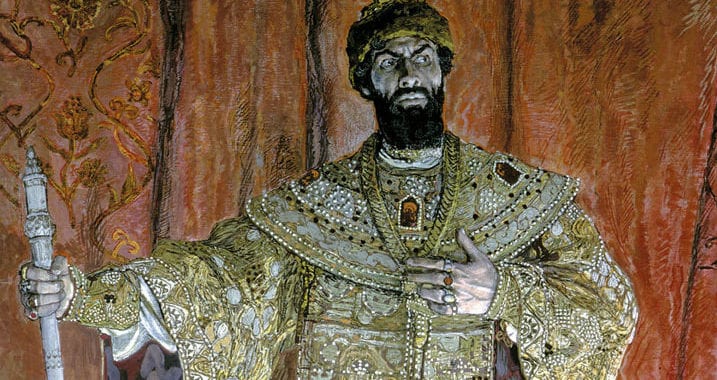

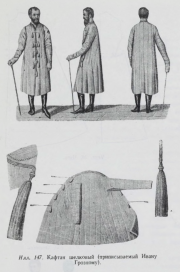

Silk caftan [Illustration 147, Diagram 13]. Several historians attribute this caftan to Tsar’ Ivan the Terrible.

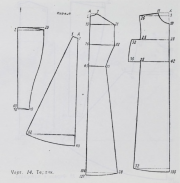

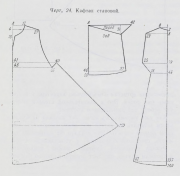

Terlik [Illustration 148, Diagram 14; pl.: terliki]. A type of caftan, relatively narrow with a normal or high waist, and with stitched buttonholes. At the neckline, hem and cuffs, a terlik was typically decorated with silver or gold braid, pearls and precious stones. Terliks were sometimes made from fur, with a fur collar around 12cm wide. Ivan the Terrible wore such a terlik. Members of the court would wear terliks at receptions of ambassadors or eminent guests. By the 17th century, they were worn only by civil servants and the tsar’s bodyguards.

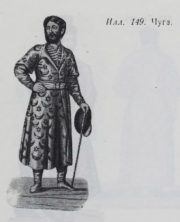

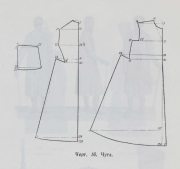

Chuga

[Illustration 149; Diagram 16; pl.: chugi]

An outfit worn when riding or by the military. The cut of the chuga was similar to that of a caftan, but with short, elbow-length sleeves. These were worn over a zipun, and belted with a belt or sash. Cuts were made along the bottom on either side for convenience when riding. Chugi were made not only from broadcloth, but also from satin, velvet or brocade. On the chest, they were decorated with ribbons, loops and buttons. Sometimes, the buttons were replaced with studs.

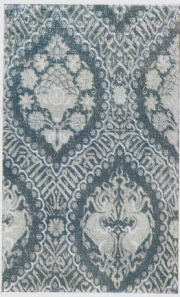

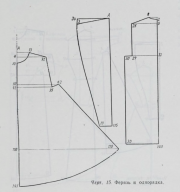

Odnorjadka

[Illustration 151; Diagram 15; pl.: odnorjadki]

A ferjaz’ without a lining or trim, made from broadcloth or various kinds of wool fabric. Worn primarily in inclement weather. Another form of the odnorjadka was the opashen’ [Illustration 150, Diagram 15].

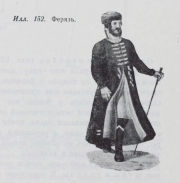

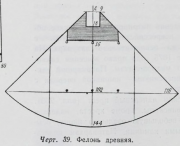

Ferjaz’

[Illustration 152; Diagram 15; pl.: ferjazi]

A long item of clothing, without a waist, reaching almost to the ankles, with long sleeves. It was worn over a caftan, and buttoned down the middle with long button loops and buttons. They were sewn from cotton and silk, and sometimes from broadcloth, velvet or brocade. Typically, the ferjaz’ had no collar, either as as a keyhole, standing or lying flat. They were decorated with braid across the chest, with knots or tassels. There were anywhere from 3 to 7 of these strips. Around the edges, the ferjaz’ was decorated with lace/knotwork, which was sometimes applied in two rows. Indoor ferjazi were classified as “cold” or “warm”, the latter of which sewn from fox or sable fur. Townsfolk and lesser merchant classes would wear the ferjaz’ directly over their shirt. According to Olearius, their ferjazi were typically white or dark blue in color, because white was the natural color of sheep’s wool, and dark blue (or “kubovyj”) was known for its durability.

Ferezeja

[Illustration 153; pl.: ferezei]

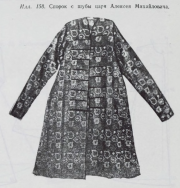

During the reign of Tsar’ Aleksej Mikhajlovich (as witnessed by Zabelin), there appeared a type of ferjaz’ called a ferezeja which was sometimes worn over a ferjaz’. It maintained its original cut, but its length and size were larger due to its use as an outer layer. They had long sleeves, like the ferjaz’, which were bunched up at the wrist, and they were decorated with button loops, buttons, stripes, lace, knots and tassels.

Tsar’ Aleksej Mikhajlovich loved this kind of coat and would wear it not only when traveling about the city or on trips to the countryside, but also as an everyday item, as well as to the palace church. The ferezeja became an official formal uniform of the court.

The riding ferezeja, like every other form of dress intended for official journeys, was heavily decorated, with stripes dripping with pearls, pearl ties, tassels, and forged silver lace. The width of the hem reached up to 280 cm, and the entire ferezeja was fit loosely, as an outer layer.

In his military outfit, Aleksej Mikhajlovich wore his riding ferezeja over a chuga.

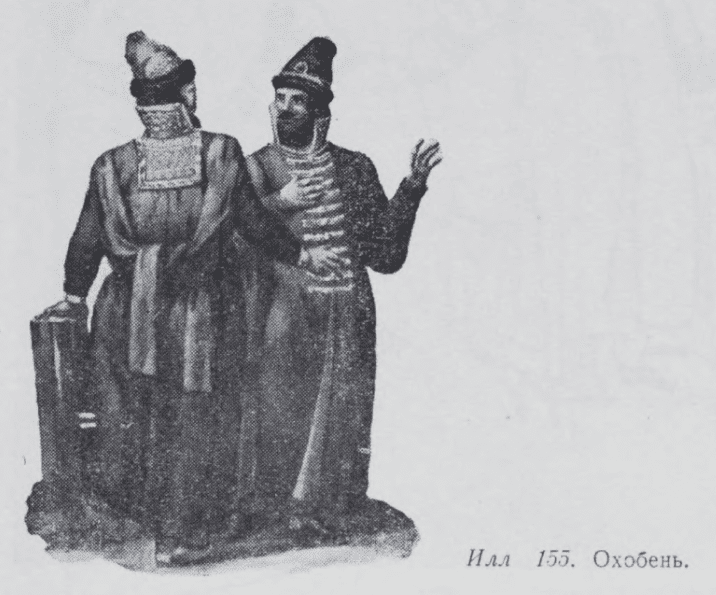

Okhoben‘ or Okhaben’

[Illustration 155; pl.: okhobni / okhabni]

In the summer, one more long, floor-length layer was worn over the ferjaz’. It was similar in cut to the ferjaz’, but wider and with openings under the sleeves through which the arms could be extended, such that the sleeves themselves hung from the shoulders [either straight or tied behind the back] as a form of decoration. The okhaben’ had a large square, loose collar, which would hang nearly halfway down the back or lower, and which was decorated similarly to the kozyr’. Okhobni were made of ob’jar’, satin, velvet, or brocade. This was worn with a hat, and to show off the sleeves.

Shuby

In the winter, peasants would wear sheepskin shuby [sing.: shuba] or coats. In inclement weather, they would wear them with the wool facing outward. The upper classes wore shuby made from broadcloth, damask, satin, velvet or brocade, decorated with hare, arctic fox, fox, mink, sable, or other fur.

Russian shuby [Illustrations 154 and 157; Diagram 17] were cut wide, with turned-down collars reaching down to the chest. They were fastened sometimes with buttons, and sometimes with long cords with tassels. In front, from the armhole to the elbow, there were slits decorated with fur or gold braid, so that the arms could be threaded through and extended.

Turkish shuby [Illustration 156; Diagram 17] Representatives of the upper classes most frequently wore Turkish shuby, which were cut the same as the Russian shuby but with longer sleeves. These sleeves could be wide to the hands, or were sometimes doubled — they would put their arms through one set, and would tie the second set behind the back as decoration.

Royal shuby had a collar of sable or beaver fur, up to 52 cm long. The edges along the hem, the wrists and the opening down the front were also decorated with fur, up to 9 cm wide. The hem, opening and wrists were also often decorated with lace or trim. Typically, the front of a royal shuba did not overlap, but rather was fastened using luxurious clasps with loops and buttons. Two excellent examples of the royal shuba were given as gifts by the tsar’ to the Baron von Herberstein [Illustrations 12 and 13].

Shuby received various names. The table shuba [stolovaja shuba] was either plain (with buttons and tassels) or covered with white taffeta and light-grey squirrel fur. The sleigh shuba [sannaja] or riding shuba [ezdovaja] had a standing collar. The standing shuba [stanovaja] was probably called such because of its similarity to the standing caftan, which was taken in at the waistline [Diagram 18].

During coronations, the tsar’ was presented with garments made of brocade and fur — a mantle and a Russian shuba worn with the front open [Illustration 157]. When the tsar’ would process to his personal chapel without leaving the confines of the palace, he would wear a shuba directly over his zipun.

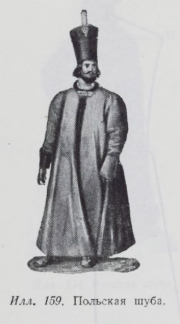

In the late 17th century, new fashions of caftans and shuby appeared. The Polish shuba [Illustration 159; Diagram 19] did not have a collar or button tabs, but rather was fastened at the neck using a stud similar a cufflink. The sleeves were wide, with fur cuffs. The 17th century caftan, also called a Polish caftan [Illustration 160; Diagram 20] was sewn from thick, dense broadcloth (or velvet). The edges were decorated with gold cord. This form of caftan was introduced during the reign of Tsar’ Fjodor Alekseevich and replaced the older, Tatar cut. The new-style caftan from the portrait of Prince Repnin the Elder [Illustration 162; Diagram 21] bore the marks of western influence. This short caftan — a zipun without sleeves and with one armhole — had a shuba-cloak draped over it [Diagram 21].[1]It is recommended to sew the cloak with one armhole and with the other side over the shoulder. His younger brother is in a long caftan with a tall kozyr’ collar [Illustration 161; Diagrams 10 and 13].

There also existed a few other forms of outerwear.

The Epancha [pl.: epanchi] was a long cloth cloak, lined and with fur trim, decorated with gold braid. The length was typical as of most longer garments, and the width of the hemline reached almost 5 meters. An epancha was worn over any outfit as a raincoat.

The Armjak [pl.: armjaki] was a variety of the ferjaz’ made from thick or thin fabric (predominantly camel wool). These were used as outerwear in times of cold or inclement weather.

Mourning (aka “quiet”, “funeral” or “sorrowful”) outfits were typically black, but were also sometimes brown, wine-colored, clove, azure or crimson in color. During times of great sadness, mourning clothes were worn by the entire court, including the imperial guard.

The cut of clothing for different classes in society was more or less identical – the difference was typically only in the material used.

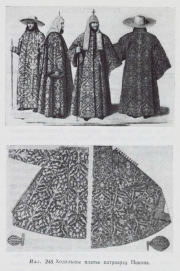

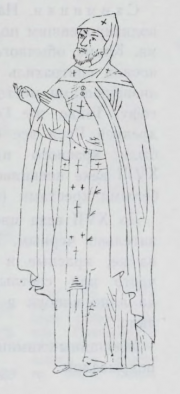

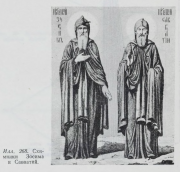

Royal Vestments

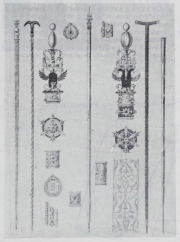

The term “royal vestments” was used for clothing and regalia which were used in particularly ceremonial situations [Illustration 163]. Zabelin, in the second part of Life of the Russian Tsars, gives the following list of items included in this term:

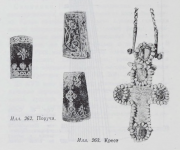

- A golden cross with a chain

- The Cap of Monomakh and other royal crowns/hats

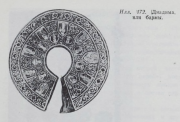

- The diadima or barmy [Illustration 172], a type of collar or very short round cape covering the shoulders and upper chest, richly decorated with icons, pearls and precious stones

- The Scepter [Illustration 169]

- The Orb of State, a golden ball with a cross

- The okladen’, a chain or sash decorated with an eagle, worn over the chest

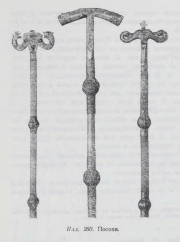

- A rod or staff [Illustration 164]

- The royal outfit

- A “standing” caftan

The Orb of Tsar’ Aleksej Mikhajlovich [Illustration 165], created around 1662, was made of gold with precious stones.

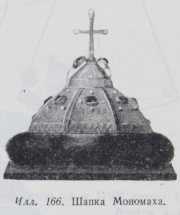

The Cap of Monomakh [Illustration 166; Diagram 23], according to legend, was sent to Vladimir Monomakh, Prince of Kiev, by his maternal grandfather, the Byzantine emperor Constantine Monomachos. The main part of the cap (a skufia of eight golden plates with a golden hoop at the bottom) is of either 11th-12th century Byzantine or 13th century Arab make. It probably once had hanging strands of pearls. A cross on a hemisphere and fur trim, as well as precious stones and settings mounted onto the filigree work are later additions (no earlier than 16th-17th century). It is likely that originally the star-shaped hole at the top was covered by a small cap or rosette to decorate the crown. The lining is of red satin.

The Cap of Astrakhan [Illustration 167] was created in 1627 for Tsar’ Mikhail Fjodorovich.

The Cap of the Second Order [Illustration 168] was created for the coronation of Peter I in 1682.

The Scepter of the First Order [Illustration 169] is gold, decorated with with precious stones and topped with an eagle and crown.

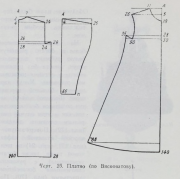

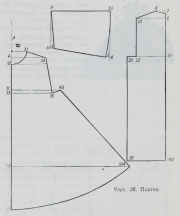

Dressing the tsar’ was a solemn act which had its own special ritual. Over a pair of silk underwear and a richly embroidered white shirt, he was dressed in a zipun, sometimes without sleeves, and sometimes with lightweight silk sleeves. When the tsar’ wore the Great Robes of State, the zipun was worn without a collar, as in this case, he would wear a diadima [Illustration 172]. Over the zipun, he wore a royal standing caftan [Illustration 171; Diagram 24], made of silk and also richly decorated, with sleeves to which were attached exquisitely decorated cuffs [zapast’ja] [Illustration 170]. Over this caftan, he would wear the so-called royal robes [Illustration 173 and 174], which was sewn from expensive gold fabric and typically decorated with pearls and precious stones. These robes were of typical length, but with extremely wide sleeves, 45-50 cm long and 27-36 cm wide at the elbow. The hem was also cut very wide. The fur set of royal robes were made from ermine fur.

Starting with the coronation of Tsar’ Fjodor Alekseevich, that is in 1678, the royal robes began to be called “porphyry”. During the coronation, it served the role of regalia.

Over the royal robes, the tsar’ would wear the diadima (or barmy) mentioned above [Illustration 172], and over that, a cross and chain of state [okladen’]. On his head, the tsar’ would wear the Cap of Monomakh. When the tsar’ would receive ambassadors or attended some other important ceremony, then in his hands he would hold the Orb and Scepter. During parades or processions, he would hold a staff. During especially important situations, the tsar’ would wear the so-called Great Robes of State, which were distinguished by an exceptionally luxurious finish; at less important events, he would wear the Lesser Robes of State, which were more modest in material and finish.

When reproducing these items for a historical performance, it is important to remember that in the 16th and 17th centuries, the cutting of stones as used by modern jewelers was as yet unknown, so the brilliance of the stones was much weaker. Nevertheless, while adhering to accurate historical data as much as possible, we in the theater must at the same time adapt to the tastes of our modern audiences. The character displayed on stage should, in the course of action, arouse in the viewer either admiration and sympathy, or dislike and ridicule. For this reason, costume should always strongly harmonize with the character of a dramatis persona. It is necessary to advise all customers to attend readings of the play and to listen carefully to the instructions given by the director to the artists regarding the nature of the roles they are to perform. This will significantly ease the work in executing their costumes.

As mentioned above, it is not necessary to dress the actor in all of the items of regalia mentioned above. Doing so would most likely severely restrict the actor’s movement, and would cause the actor to languish. The sleeves of a standing kaftan could be attached to the armhole of the robes of state, giving the illusion of inner layers. To date, there is only on play known where the dressing of the tsar’ occurs on stage. This is The Death of Ioann the Terrible by A. Tolstoj, in the scene where Ioann turns from a monk back into the tsar’. In this case, of course, it would be necessary to present the standing caftan and robes of state as separate items.

Researchers of medieval Russian clothing are of differing opinions regarding the royal vestments. Aside from differences in the descriptions of the cut, various authors also give different names for items, for example, a robe [platno] vs. an opashen’. Zabelin attributes the one robe to the Greater Robes of State, while Viskovatov attributes them to the Lesser Robes of State. We have provided two images, according to Solitsev [Illustrations 173-174; Diagrams 25 and 26]. While admitting the great importance of showing these figures in all their glory to the people or to foreigners in the full splendor of their greatness, at the same time, the tsars dressed very plainly in private. On processions, the tsar’ walked in the richest outfit possible, but when entering a crowded place, he would change into a more modest outfit. The cut of clothing among various levels of society was typically more or less identical, but the material from which they were sewn varied widely.

Belts and Sashes

Starting with the simple cord which a Russian peasant would use to belt his shirt, belts and sashes in Russian costume were an unending variety, both in the selection of material from which they were prepared, as well as in color, size and decoration. Zipuny and certain caftans were belted. Remaining items of clothing were worn unbelted.

Young men would wear sashes at the waistline, tied rather tightly in order to emphasize the slimness of their figure. Those who were of a more mature age, and in particular those who were overweight, found it convenient to wear their sashes lower, highlighting the roundness of their bellies. Describing the clothing of the 16th century, Herberstein writes on this topic: “They are tied not at all at the waist, but at the hips, and the belt could even be tied below the groin, in order to emphasize the stomach.” It is worth remembering that plumpness and corpulence were considered in medieval Rus’ to be a sign of affluence. Not only did they not try to hide the fullness of figure via the cut of their clothes, but exactly the opposite, they strongly reinforced its splendor with one after another item of clothing. For this reason, boyars and the well-to-do of medieval Rus’ should be presented on stage as plump, sedentary and a bit awkward. Only a young man should be slim and lean, for example, an unmarried individual who has not yet had time to become a sturdy family man.

Belts and sashes were made from leather, silk, brocade and velvet, decorated with embroidery, silk, gold, pearls, precious stones, forged metallic plaques, gold braid, etc. Frequently they were decorated with an array of pendants and decorations, as well as a money purse [kalita], a small bag like a wallet, used into the 17th century. Wider sashes were folded over several times and were made of various colors of silk, often decorated with gold or silver. From a belt or sash, they would wear a knife, a kinjal, or sometimes a knife and spoon. A beautiful, artfully selected sash could highly emphasize the effect of an outfit [Illustration 175].

Gloves and Mittens

Due to the harsh climate, people of all levels of society including peasants would wear gloves in the wintertime, which in addition to their primary use also served as decoration for the wealthy, complementing their overall outfit with their finery. Handwear (both cold and warm weather) were divided into mittens and gloves [Illustration 176]. They were made not only of leather or goatskin, but also of velvet, silk, and so forth. Knitted gloves were common. For example, the imperial wardrobe included a pair of gloves that were “rainbow-colored, with the wrists embroidered with gold on scarlet satin with pearls, with a gold and silver fringe; knit scarlet silk, a golden wrist, and a golden fringe, mounted on scarlet taffeta”, and so forth (Zabelin).

When creating gloves or mittens for the stage, we should be guided by the same considerations as were already stated above with regards to sashes. Discarding unnecessary details, one must choose choose a pattern that is significantly large and colors that are harmony with the costume as a whole.

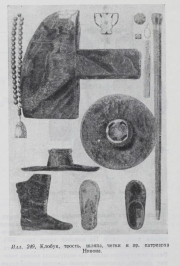

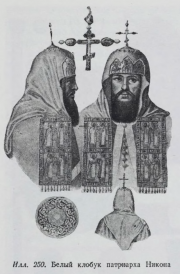

Hairstyles and Headwear

Hair in Muscovite Rus’ was worn relatively short, often braided.[2]For hairstyles of earlier times, see the corresponding illustrations. Olearius reports that several nobles even shaved their head. Long, uncut hair was worn by members of the clergy and by boyars who had incurred royal anger and disgrace. As a sign of mourning, a boyar would cover his face with tangled, unkempt hair.

Long beards were always at a premium in Rus’. A long, full beard, just like corpulence of the body, inspired the respect of those around. And yet, in the early 16th century, it was normal to shave one’s beard. For example, Prince Vasilij Ivanovich shaved his beard when preparing for his second wedding. However, during the reign of Tsar’ Ivan Vasil’evich the Terrible, shaving one’s beard and mustache was firmly forbidden by law. “The repeal of this law during Godunov’s reign was one of the important reasons for the people’s dislike of him,” writes Savvaitov. There is a portrait of Boris [Godunov] that has survived, showing him with only a mustache and beard.

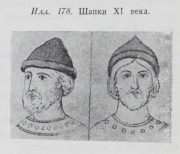

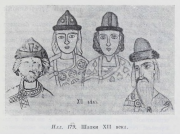

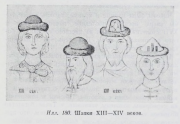

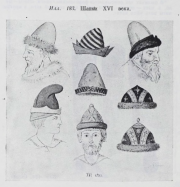

Starting in the 11th century, Russian men have worn hats of various forms [Illustrations 177-183]. In the 16th century, tall pointed hats made from felt or lamb’s wool and narrow fur trim are mentioned in sources as kolpaki [see description below], but in the 17th century, these changed into simple hats. They were worn by everyone, including the tsar’. In the summer, the lower classes would wear hats primarily of felt or lamb’s wool; in the winter, they were made from thick broadcloth. The middle classes wore hats made from thick broadcloth or velvet. Among the upper class, hats were made of velvet or brocade, with embroidered or appliquéd decorations of silver, gold, pearls, and precious stones. Tsar’ Aleksej Mikhajlovich began to wear these instead of the crown, making the hats seem low and flat.

A different fashion of hat was the murmolka [Illustration 59; pl.: murmolki], a tall, flat-topped hat, slightly fitted to the size of the head. These hats were made from velvet or brocade. Instead of a head band, they had flaps which were buttoned in front to the crown of the hat and in two places with loops and buttons. Murmolki were primarily worn by young men.

In the 16th century, the boyars also wore a thick fur hat with the fur facing outward, which can be seen on the image of the Sugorskij embassy [Illustration 22]. In the 17th century, this hat morphed into the tall boyar hat [gorlatnaja shapka, literally, “throat hat”], so named because it was primarily sewn from the throats fur of animals [Illustrations 145 and 156]. These hats, which were up to 35 cm tall, were cut to the circumference of the head at the opening and became wider toward the top, and were primarily made from the fur of silver fox, sable or marten. The tops of hats were usually either velvet or brocade, sometimes with silk, silver, gold or pearl decorations. “In the treasury of Tsar’ Mikhail Fjodorovich in 1630, there was a boyar hat with silk,” reported Zabelin. These hats are believed to have been worn only by the sovereign and members of the Duma. But, in formal situations and during audiences, solicitors, nobles, clerks and even guests would appear at court in these hats. During the reign of Tsar’ Mikhail Fjodorovich, the boyar hats were not removed from the head even in the presence of the tsar’, not when receiving ambassadors or at meetings of the Duma. During the reign of Aleksej Mikhajlovich, in such situations, they would hold their hats in their hands. Murmolki and boyar hats were sometimes decorated with a broach of precious stones or large pearls with a spray of white feathers or seed pearls.

Underneath this outer headwear, they would wear a taf’ja[3]jeb: See here for more info. [pl.: taf’i], a small hat which covered the top of the head. These hats were also worn continually at home. A dressy taf’ja was made of silk of various colors, gold, pearls and precious stones. During the rule of Ivan the Terrible, this kind of hat was also worn by the oprichniki, even in church. The indignation of the clergy led them to ban these hats in the laws of the Stoglavy Synod. Taf’i were also worn by clerks; they were not worn by peasants, townsfolk or merchants.

Another form of hat was the kolpak [pl.: kolpaki], which was somewhat pointed with satin, broadcloth, velvet or gold fabric, and which instead of fur trim had a raised brim in the form of a lapel. In front, these brim flaps were separated by a gap, above which was placed an expensive brooch of pearls and precious stones. In royal live, kolpaki were worn primarily on outings, and on holidays or for solemn occasions.

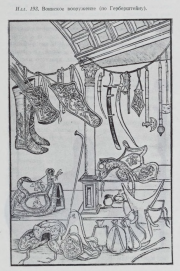

Footwear

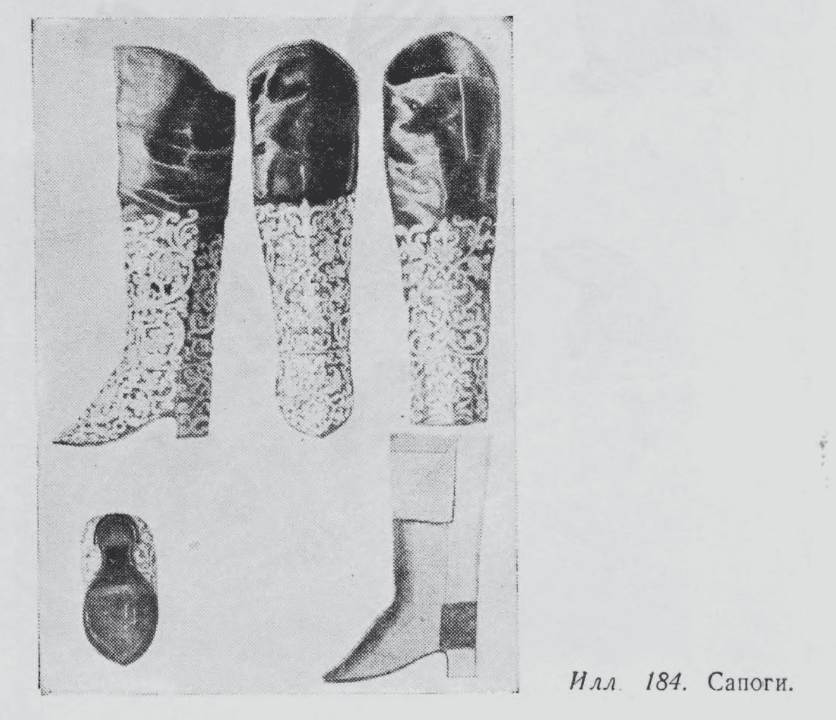

Since ancient times, the most common Russian footwear has been bast shoes [lapti], made from bast fiber and attached to the foot (which is wrapped up in cloth) with a bast strap or a cord. Wealthier individuals wore boots or chjoboty [see description below], depending on their level of wealth: simple, leather or goatskin, pointed, with the tops bent upward. The sole was attached using small hobnails, and the heels would have silver or iron straps attached, again depending on wealth. Boots came in various colors: black, yellow, green, and predominantly red; the wealthy would have boots decorated with silver plaques, metallic braid, or embroidered designs, and often with pearls and precious stones. Boots were also made of velvet. The boot-tops were cut at an angle, were folded down nearly to the middle of the calf, and were tied below the knee with a strap or garter. Some people would tie their boots below the calves. The first two ways of wearing boots were already seen as early as the 11th century; the latter is seen in images starting in the 13th and 14th centuries. Herberstein writes thus of footwear in the early 16th century: “The boots they wear are primarily red and moreover are very short, such that they do not reach the knee, and the heels are decorated with iron straps.”

16th century boots were similar to Tatar boots, without heels [Illustration 193]; in the 17th century, on the other hand, they had large heels [Illustration 184].[4]In the epic poems, smart-looking boots were described thus: “Their noses were embroidered, and their heels were tall.” “A nightingale could fly under the heel, and or even lay an egg.” Around the 17th century, shoes of various colors for men appear, made of Russian leather, goatskin, or velvet, with knit or silk stockings also of various colors. These also had gold and silver designs, and were decorated with hobnails and plaques. It is inconvenient to dress actors representing Russians from the pre-Petrine period in stockings and shoes; by long-standing tradition, they are exclusively dressed in boots.

Royal footwear. The tsar’s wore only boots or choboty, a type of boot with short boot-legs, made of velvet and almost always decorated with gold thread, pearls and stones. Typically the fronts, backs and heels were decorated. Tsar’ Mikhail wore “choboty of yellow, crimson and azure goatskin.” The Great Robes of State included a pair of particularly richly embroidered choboty. Zabelin describes them as: “Chjoboty dripping with pearls, on a base of crimson velvet, half-length, on the front there are three azure sapphires in settings, and on the sides, and on the back there are emeralds; they are lined with crimson ob’jar’ [a type of thick, silk fabric]; the tops are decorated with gold and azure silk; the heels are silver.” Many of the grand princes had chjoboty which had the toe and heel “decorated with Ormuz pearls.”

Chjoboty could be straight or curved, that is, with the toe curled upward; the latter was seen starting in the 17th century. They were made of dyed goatskin and were richly embroidered with gold. When riding horseback, spurs were attached.

The garters which, as mentioned above, were used to tie boots under the knee were very smartly decorated. Zabelin gives the following description: “The garters are encircled in gold and silver stars and crimson, azure and tausine silk, and at the tips, green silk and gold. The buckles and strap ends are of hammered silver and gold….” Zabelin writes that the straps were decorated in this way such that they would be very visible when riding horseback in a short outfit.

Clothing of Court Officials

With the exception of the imperial guard, courtiers did not wear a particular uniform, but would dress typical of a boyar. The tsars would give those around them clothing “off their own royal shoulders.” During royal processions and great receptions, they would lend outfits from the royal storerooms for temporary use. In the winter, boyars and other dignitaries would appear before the royal throne wearing a plain shuba or a squirrel and taffeta shuba. The tsar’ would sometimes appear in a shuba of silver brocade. Zabelin notes that during a ceremonial reception, “chashniki i stol’niki[5]jeb: Two of the ranks at court, cup-bearers and throne-attendants. wore clothing of gold and silver brocade with long collars almost a half-arshin[6]About 36 cm. in width, with drop pearls running down the back, taf’i covering the crowns of their heads, tall boyar hats. The stol’niki who were great or senior in rank wore chains on their chests with precious stones.” At a royal feast, according to the same author, beside the tsar’ “to the left and right stood stol’niki with swords in gold ferezei and hats.” At the gates to the palace there stood “zhil’tsy[7]jeb: Another court rank, see more below. with partisans and halberds, in crimson caftans and terliki made of ob’jar’. … In the winter, when the sovereign would go riding in a sleigh, the driver and the attendants would also wear terliki as a type of uniform… Zhil’tsy would also wear terliki when sitting behind the royal throne” (Zabelin). It is known from the inscriptions in the royal tailor’s books that in 1647, they created ferezei for the stol’niki.

Artists and costumers are given great leeway in the selection of fashion, color and material for clothing, but they need not overload the stage with gold shuby, lest they overwhelm the viewer. In addition, on the stage, impressing the viewer is not the only important thing. It is necessary to convey to the public the social standing of the characters on stage. For this reason, it is better to dress in gold perhaps a few of the boyars who are closest to the tsar’, the next in rank in velvet, lower ranks in broadcloth, etc.

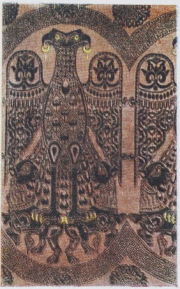

During the reign of Aleksej Mikhajlovich, there appeared at court the need for the falconer [sokol’nik], as falconry was a favorite activity of the tsar’. The falconer’s outfit included: “a colored broadcloth caftan with embroidery of gold or silver, depending on the fabric, and yellow boots.” On the chest and back, these had embroidered eagles [Illustration 185; Diagram 27]. The caftan shown in the adjacent image is reminiscent of that of a herald at an imperial coronation. There is reason to suppose that this caftan was patterned after western clothing which was appearing at that time in Russia along with foreign troops (until this time, no other Russian item was fitted at the waist). The presence of western influence is also seen in the fashion of the puffed sleeves. A Russian engraving from the 17th century [Illustration 186] shows a falconer dressed in an outfit with a cut that is quite typical for that time.

Talking about those who surrounded the tsar’ of Muscovy, it is impossible not to mention the jester who was an indispensable companion not only of the tsar’, but also of every noble. In the monotony of medieval Russian life, jesters, midgets and the like provided a certain liveliness. The costume of a jester was similar to that of everyday wear, but was made from panels of different colors; instead of buttons, there were bells sewn to the outfit, and and bells were also sewn to the hat. Frequently the jester’s outfit would be decorated with trim, and sometimes the costume would be made up from the ends of various kinds of fabric, on which would be woven or written depictions of factory symbols, emblems, letters, and so forth. Zabelin writes: “In 1618, the sovereign granted the fool Mosej a broadcloth odnorjadka of various colors, with forged metallic lace, with silk ties and loops; a broadcloth caftan made of remnants of various colors, also with ties and lace and with tin buttons.” Sometimes a jester’s outfit was made from rogozha, a rough fabric made from woven bast.

Imperial Guard

The imperial guard belonged to the so-called regular troops. Our description of them is entirely thanks to Viskovatov, who dedicated particular effort to the clothing and weaponry of the Russian soldier. Of the orders serving the tsar’, particular outfits were worn by the ryndy, zhil’tsy and the bodyguards.

The ryndy, established by Grand Prince Vasilij Ivanovich (father of Ivan the Terrible), were the omnipresent bodyguards of the tsar’. During times of war, the ryndy and sub-ryndy would follow behind the tsar’ as armor-bearers. During all processions and ceremonies, the ryndy would walk beside the tsar’, carrying poleaxes on their shoulders. They were dressed in terliki or ferjazi of white damask, satin, broadcloth, or velvet or of silver brocade. The hem and edges of their outfits were decorated with ermine fur. They wore tall white hats [Illustration 187; Diagram 28]. During the reign of Aleksej Mikhajlovich, the ryndy began to wear murmolki, which were also white with ermine trim. Their boots were also white. Two gold chains hung crosswise across their chest, from shoulder to hip.

The zhil’tsy were established by Ivan the Terrible and were named as such because the majority of them came to Moscow from other cities looking to “earn their living.” They were selected from the children of the nobility. The zhil’tsy were an honorary guard; they would appear at court during ceremonies dressed in terliki of various colors made of velvet, ob’jar’ and satin, in hats of gold brocade with fur trim. Their weapons were halberds and partisans. In 1674, the zhil’tsy wore as their outer wear a caftan with a small standing collar, padded with fur and tied with long sashes which had fringe on the end. On the front of their hats there was a decoration embroidered in silver or gold; on their hands, they wore gloves with wide openings. During the reign of Fjodor Alekseevich, in Moscow there was a squad of zhil’tsy with large wings fastened to their backs [Illustration 188]. They also had gilt metallic dragons fastened to their long spears. The Polish embassy which was in Moscow at the time called them “the Legion of Terrible Angels.”

The bodyguards of Dimitrij the Pretender were of two types: those who carried halberds, and those with partisans. The partisan-carriers wore sumptuous red decorated with gold braid. Their spears’ tips were decorated in gold with the royal coat of arms, and the spear poles were wrapped in velvet. A tassel of gold or silver hung from the top of the spear pole. The first order of the halberd-carriers wore purple outfits with sleeves of red damask and piped in red velvet cord. The second order had sleeves and piping of green. Their ceremonial clothing was velvet, everyday was broadcloth. The exact cut of these foreign soldiers’ outfit is unknown.

Weaponry

Medieval Russian soldiers fought on foot. Only princes and commanders would ride out on horseback. A soldier’s armor consisted of chainmail [kol’chuga], a type of shirt made of small iron rings, also called a pantsyr’ (from the Greek word “pansiderion“) or a bajdana (from the Arabic بدن “badan“). These were different only in form and the size of the rings. Soldiers also wore chainmail leggings, boots, and pointed helms, to which were attached a chainmail curtain in back, joining together in the front, in order to protect the nape and neck [Illustration 191].

Weaponry consisted of a sword [Illustration 189], which was hung from the belt, a knife, a long spear, and shields [Illustration 190] of various forms and red in color. Shields were flat or convex, typically round, and made from leather, iron, copper, or damask steel, sometimes covered in leather or velvet, and for a warlord, would be richly decorated.

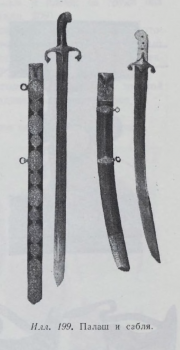

In the 13th century, Russian soldiers adopted from the Tatars both their weapons and armor, and assimilated their methods of warfare. Professor S.K. Bogojavlenskij writes, “Swords finally receded into the realm of legend as a weapon that was too heavy, and designed only to provide the strong blow necessary to crush heavy, solid armor, which our closest neighbors and enemies did not have. Sabers became common in our country earlier than in Western Europe, due to our extensive relations with the East, where sabers were held in special esteem as weapons for crushing, piercing and cutting. The pommel of a saber was in the shape of a cross in order to protect the hand through the hilt, a longitudinal metal strip which was intended to stop enemy weapons sliding along the saber blade. Eastern sabers were highly prized due to the elegance of their finish and the merits of damask steel…”

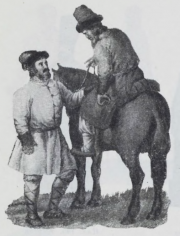

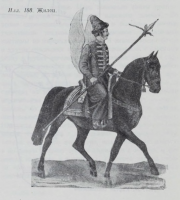

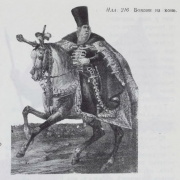

The main opponent of the Rus’ in the 16th century were the Tatars, who troubled the southern and eastern borders. The Tatars were almost exclusively armed in cold steel. So too were the Russian soldiers, for the most part. Until the 17th century, noble cavalry was the primary army. Nobles were required to perform military service at the call of the authorities “mounted, peopled and armed,” that is, on their own horse, accompanied by armed servants and with their own weapons [Illustration 193]. The men accompanying their noble to war were required to carry all supplies (the noble ate at his own expense) and to defend him from harm. The noble was also armed at his own expense, by his own means, and per his own tastes, as official requirements in this regard were vague.

Warfare on the eastern border against the semi-nomadic neighbors long preserved old methods of warfare. There were almost no firearms. Some nobles made use of carbines and pistols [Illustration 192], but they were short-lived and inferior to Tatar arrows, which could pierce straight through a person and kill their horse on the spot. Shields, which were heavy and bulky, were already no longer in use. The role of shields was filled instead by permanent and temporary fortifications, or at the very least by cover from carts, which was widely practiced in the battle against the Crimeans.

If a cloud of arrows fired at the Tatars was unable to stop their onslaught, then hand-to-hand combat would ensue. For this purpose, it was necessary to have light weapons in the form of a saber. In warfare against the Tatars, spears were little used.

In the 16th-17th centuries, Russian armor consisted of chainmail to which additional defensive bits were attached. The Russian troops did not wear complex solid metal armor. Instead, they used chainmail with two or three rows of metal plates on the chest, back and sides. Aside from this, they also wore:

Bekhterets – Rows of metallic chainmail, covered from top to bottom by continuous rows of narrow plates, like scales. On the bekhterets worn by Tsar’ Mikhail Fjodorovich, the chest was covered by five rows of scales, with 100 scales in each row.

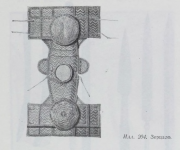

Zertsalo – several metallic plates covering the entire body, protecting the chest, sides and back; the outer plates were fastened using ties [Illustration 204]. The right to wear a zertsalo belonged to the highest commanders.

The aventail [barmitsa], a type of steel mantle.

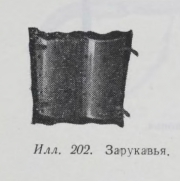

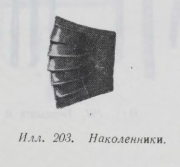

Bracers and Greaves, fastened metallic plates for the arms and legs [Illustrations 202-203].

Aside from metallic plates, they also wore tegiljaj [Illustration 196], a quilted outfit made from wool or other fabric, with a tall standing collar, fastened with buttons, and with short sleeves, and a kujak, a form of Brigantine armor from broadcloth, velvet or other fabric covered with metallic scales on the chest, back and sides [Illustration 215].

In addition to the cavalry, during times of military action, there also would have been foot soldiers. Their armaments and clothing woudl have been of the same character, but of course, a bit more randomly assorted and of lower quality.

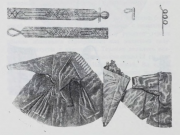

Knives of various forms, both long and short, with straight or curved blades, worn largely at the belt, but sometimes stuck into the leg of a boot.

A kinzhal with a long and sometimes curved blade was worn in a scabbard, which was hung from the belt.

A spear made of damask steel, steel or iron of various forms, attached to a long wooden pole [Illustrations 191 and 197]. In many cases, behind the tip there was a spherical ball called a jablochko [literally, a “little apple”].

The flail [kisten’] was a short stick with a metallic weight attached at one end and a loop for the hand on the other. [8]jeb: See an example here.

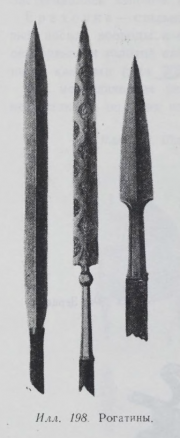

The bear spear [rogatina] was a weapon, similar to a spear, but with a wide, flat head. The pole had two or three metallic fixtures to make it easier to grip [Illustration 198].

A poleaxe [berdysh] was a weapon in the form of a wide axe, sharpened on one side and fastened to a long pole. There were many styles of poleaxes [Illustration 197], and they were used only by foot soldiers (cf. the clothing of the strelets).

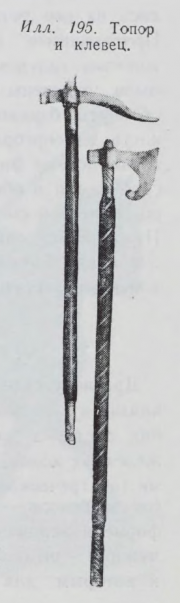

An axe [topor] [Illustration 195] was similar to a poleaxe, but smaller in size. This was used as a weapon by cavalry.

A six-flanged mace [shestopjor] was the symbol of a leadership. It was made up of a handle with a metallic cap on one end, and on the other, six “feathers” (flanges). Maces with more a greater number of flanges were called a pernat or a byzdykhan.

A mace [bulava] was the symbol of the most powerful leaders and soverigns. Instead of flanges, this had a “head” in the form of a sphere or polyhedron [Illustration 216].

A bow quiver [saadak] was the weapon of a horseman, consisting of a bow with all of its accessories. The saadak included a bow with a bow case, and arrows in a quiver [Illustration 205]. The bow and bow case were worn on the right side, while the quiver and arrows were worn on the left, suspended from the saber belt or from its own belt. The case and quiver were made of leather or goatskin; the wealthy would cover theirs in satin, velvet or brocade and decorated them with embroidery and stones.

Field equipment included cloth bags to carry various trifles, and vessels of leather or of wood covered with leather for storing water and wine.

Firearms appeared in Rus’ in the 14th century, but entered general use only in the 16th century. The hand cannon [pishal’] was the first firearm in Rus’. They were also called a samopal, and various forms of them were called carbines and muskets. They were used with a wooden monopod with a metallic mount. With the advent of firearms, soldiers began to wear a special kind of belt or bandolier called a berendejka [pl.: berendejki], which had a series of charges or boxes hollowed out of wood and pasted over with leather hung from it [Illustration 218]. Sometimes the berendejka was also used to carry a bag of shot, a bag of wicks, and a box or horn for powder. The powder boxes could be made of wood, bone, mother of pearl, copper or silver, and were often distinguished by their luxurious and delicate finish.

The line of medieval weaponry also includes halberds and partisans.

A halberd [alebarda] is a weapon in the form of a wide axe or sickle on a long pole which can be painted or decorated with velvet or cloth.

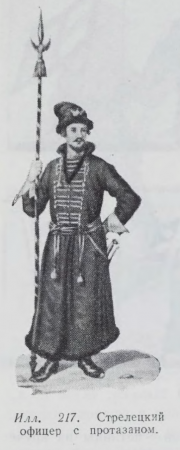

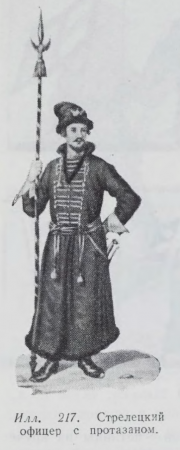

A partisan [protazan] is pole with a wide, solid or slotted spearhead. Partisans always had silk, silver or gold tassels [Illustration 217].

Military Headwear

A helm or helmet was an iron hat with iron earflaps, fastened under the chin. At the front of the visor, a nosepiece was attached to the helmet – a metallic strip to protect the face from saber blows.

A kolpak [Illustration 209; pl.: kolpaki] was made up from several pointed petals joined at the bottom by a band and at the top by a metallic decoration. A chainmail curtain was attached to the bottom of the kolpak covering the cheeks, nape and shoulders. At the chest, it was fastened with a buckle.

An erikhonka [Illustrations 207 and 215; pl.: erikhonki] was a steel helmet worn by generals and sovereigns, richly decorated with gold and silver inlay, and sometimes even with precious stones.

All metallic headwear was thickly lined, and quilted caps were worn under them.

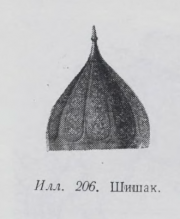

A shishak [Illustration 206] was very similar to a kolpak, but with a sharply pointed spire at the top.

A misjurka [Illustration 211] was an iron hat with a chain aventail and earflaps, flat on top, reaching down to the forehead (misjurka-prilbitsa) or covering only the crown of the head (misjurka-napleshnik).[9]jeb: The name comes from the Arabic مصر Miṣr “Egypt.”

A cotton cap [shapka bumazhnaja] [Illustration 212] was a type of hat, made of various materials, with a dense lining of cotton or hemp, with the addition of pieces of metal inside the lining. These hats also had a metal nosepiece.

An iron cap [shapka zheleznaja] was the headwear of militia troops. This was a short hat of sheet or wrought iron, without a nosepiece, earpieces, or aventail.

Horse Wear

Saddles were relatively tall, with short stirrups. Spurs were used infrequently. Horses of warlords and of the tsars were outfitted quite richly, and their saddlecloths were decorated with embroidery [Illustrations 193, 215, 216].

Indispensible (Regular) Troops

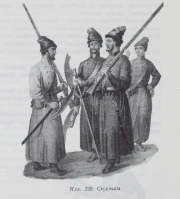

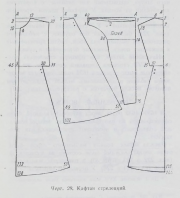

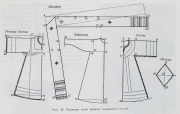

Strel’tsy [Illustrations 217, 219, and 220; Diagram 29]. The strel’tsy force was created by Tsar’ Ivan the Terrible around 1550. When dismantling the Moscow strel’tsy in 1710, Peter I left them in other cities, where they continued to exist for some time.

The strel’tsy dressed in long broadcloth caftans. They were armed with sabers, hand cannons, improvised firearms, and poleaxes, which they carried on their soldiers while marching; the rest of the time, they carried them in their right hand. Each strel’tsy regiment included spearmen.

In 1606, in Moscow, there were mounted and foot strel’tsy. The former wore red broadcloth, white berendejki, and long firearms with monopods, which were red. The spearmen were armed with spears and sabers. In 1661, according to Baron Meyerberg, the Moscow strel’tsy were dressed (depending on the regiment) in red or green of various shades, hats trimmed with fur, and white berendejki. In 1664, the Swedish captain Palmquist, who served in the embassy, described 14 different types of outfits worn by the Moscow strel’tsy:

- 1st regiment of Egor Lutokhin – a red outfit with crimson tabs, dark grey hats and yellow boots

- 2nd regiment of Ivan Poltev – a light grey outfit with crimson tabs and lining, crimson hats, and yellow boots

- 3rd regiment of Vasilij Bukhvostov – a light green outfit with crimson tabs and lining, crimson hats, and yellow boots

- 4th regiment of Fjodor Golovlinskij – a cranberry colored outfit, with black tabs, yellow lining, dark grey hats, and yellow boots

- 5th regiment of Fjodor Aleksandrov – a scarlet outfit, with dark red tabs and light blue lining, dark grey hats, and yellow boots

- 6th regiment of Nikifor Kolobov – a yellow outfit, with dark crimson tabs, bright green lining, dark grey hats, and red boots

- 7th regiment of Stepan Janov – a light blue outfit with black tabs, brown lining, crimson hats, and yellow boots

- 8th regiment of Timofej Poltevo – an orange outfit, with black tabs, green lining, cranberry colored hats, and green boots

- 9th regiment of Pjotr Lopukhin – a cranberry colored outfit, with black tabs, orange lining, cherry colored hats, and yellow boots

- 10th regiment of Fjodor Lopukhin – a yellow-orange outfit (previously, ore-yellow), green tabs and lining, crimson hats, and green boots

- 11th regiment of Davyd Vorontsov – a crimson outfit, black tabs, brown lining, brown hats, and yellow boots

- 12th regiment of Ivan Naramanskij – a cherry-colored outfit, with black tabs, light blue lining, crimson hats, and yellow boots

- 13th regiment of Lakovskin – a lingonberry outfit, with black tabs, light blue lining, crimson hats, and yellow boots

- 14th regiment of Afanasij Levshin – a light green outfit, with black tabs, yellow lining, crimson hats, and yellow boots

The trim of the strel’tsy caftans had tabs of twisted cord, either singular or doubled, with short tassels on the end. Their outerwear had small standing collars[10]Until the 1st quarter of the 17th century, these were turned down., and their hats were trimmed with fur. Strel’ets flagbearers had hats without fur trim, with the hat band bifurcated over the brow, sabers hung from their leather belts, and leather berendejki and pouches. The officers of the strel’ets regiments were dressed almost the same as described above for 1674: they were armed with sabers and partisans, walked with a cane or staff, and wore bell-cuffed gloves [Illustration 217].

Foreign Troops

In 1630-1632, before the war with Poland, several regiments were formed from foreign soldiers: 4 foot or soldier regiments, and several dragoon or cavalry regiments.

The clothing for these foreign foot regiments was quite non-uniform. Each regiment was made of up musketeers [Illustrations 222, 223; Diagram 30] and pikemen or spearmen [Illustrations 224, 226]. The former had baldrics over their shoulders with a saber or sword, and in their hands they carried a musket with a wooden stock, to which was attached a lanyard. Over their left shoulder, they wore a buckskin bandolier, which carried charges and wicks. Their heads were protected by steel helmet or shishak with earflaps, fastened under the chin. The spearmen carried spears and pikes that were over 2 sazhens long [11]jeb: 1 sazhen’ was equal to 3 arshin or 2.13 m., steel helmets and armor, the front of which was divided into two halves. Around their necks they wore gorgets, they had swords hanging from their belts, and they also wore bracers.[12]For the theater, armor can be made of metal, or papier-mâché with metallic paint. In the ranks, German captains carried spears, guards carried partisans, ensigns carried battle standards, and sergeants carried halberds.

The Russian foot regiments, organized around the same time, were armed like the German regiments, but were dressed the same as strel’tsy, in outfits called service dress. Their standards were called spear flags. They were primarily made out of fabric with various images depicted on them, and were quadrangular with two long, pointed ends, like swallowtails.

The weaponry of the German dragoons was the same as that of the musketeers, except for the axes which they tied to their saddles. The German cavalry (reiters) wore shishaki and armor as described above. For weaponry, they had swords, two pistols, and a musket, which was later replaced by a carbine.

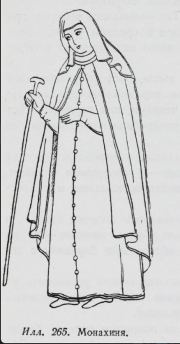

Women’s Clothing in Muscovite Rus’

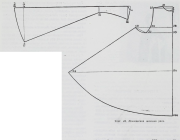

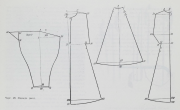

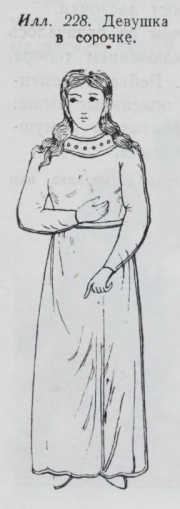

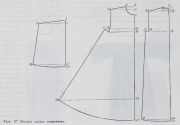

Women wore a long, white, linen shirt (sorochka) with rather long sleeves [Illustration 228]. This shirt was cut from straight panels, equally wide at the collar and hem. The superfluous material was gathered on a ribbon at the collar, where where a small cut was made in the front. Well-to-do women wore two shirts, an outer and an inner (with short sleeves). The outer shirt, worn at home as outerwear (strangers would not see her in this alone), was called the “red,” that is, “beautiful” sorochka. It was sewn from colored silk fabric and decorated with embroidery and ornamentation. The sleeves, narrow and very long, were gathered at the wrist in small folds and were decorated with silk or goldwork embroidery and pearls. The seams were decorated with gold braid or small pearls.

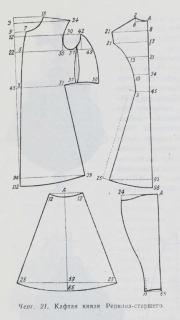

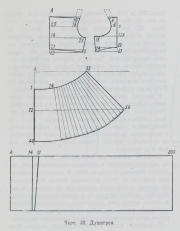

Over this shirt, a woman would wear a sarafan. Excessive fabric was gathered at the waist. Sarafany were made from homemade canvas, colored calico, or block-printed fabric; for the wealthy, they were made of expensive fabric, and were straight, tapered downward, or were cut so that there was almost no gathering at the collar. In front, they were decorated from top to bottom with gold braid and a row of buttons [Diagram 31]. A portrait of a woman in a sarafan [Illustration 230] has survived from the 18th century. Earlier depictions of sarafany no longer exist.

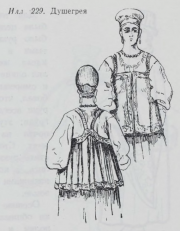

The dushegreja [Illustration 229; Diagram 32; pl.: dushegrei] were a type of short blouse (without sleeves) worn over a sarafan, suspended on straps, and in cut reminiscent of a sarafan. The dushegreja was fastened in front with a row of buttons. The front panels hung flat. The back was very wide, with material added through even pleats.

Outerwear for wear outside the home were divided by cut into two types: overhead and opashen’-like. The overhead type items were without an opening, and were put on over the head. The opashen’-like items were fastened down the front with buttons or laces.

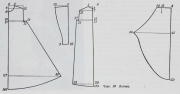

The letnik [Illustration 231, Diagram 33; pl.: letniki] were a floor-length, wide, overhead item, which was sharply angled to the floor. The sleeves, which were called nakapki, reached to the floor, and were sometimes longer than the letnik itself; their width was equal to half their length. The sleeves were sewn together only about half their length, or perhaps slightly more. The lower half remained unsewn, and hung open freely as a panel.

The letnik was decorated with voshvy, made up of small pieces of more dense and expensive fabric than the letnik itself, typically of smooth satin or velvet, 105-140 cm in length and 35 or more cm wide. These pieces, which were richly embroidered with silk, gold, and sometimes pearls or precious stones or even metal plaques, were cut on the bias, in the form of a triangle, the pointed end of which was slightly rounded off. They were attached to the sleeve such that the wide end of the voshva was pointed upward, near the wrists, and the pointed end hung downward toward the floor. In order to keep the voshva from becoming crumpled and to ensure it always remained flamboyant, it was stiffened from the inside with a fish glue.

Voshvy were usually made of a different color than the letnik. Smaller sets of voshvy which decorated the chest and collar were called peredtsy. Peredtsy generally referred to pieces of expensive fabric sewn to visible parts of clothing. For this reason, it is possible to find mention of voshvy at the wrist being decorated with peredtsy. The will of Prince Verejskij (died 1486) mentions: “A letnik of ob’jar’ panels, and a voshva of black samite; a green brocade letnik, and a scarlet voshva…” Among the letniki of Evdokija Luk’janov, there is mentioned one that had “voshvy of scarlet silk base dripping with pearls, and on the base, 18 azure sapphires in gold settings, and 41 crimson rubies, plaques and stars of gold, and bright gold gimp and seed pearls, and between the gold stars there were more, smaller stars.” On another letnik there was “at the collar peredtsy of scarlet satin embroidered with gold and silver.”

In order to ensure that the voshvy were completely visible, it was necessary to hold one’s hands at elbow height. Since the ideal woman was the personification of meekness and humility, custom demanded that she keep her hands always folded on her chest; we find this pose on almost every depiction. If they were to let their hands fall, then the voshvy would become crumpled and their ends would drag along the ground.

Autumn and winter letniki were trimmed at the collar, opening and hem with fur, usually beaver, about half-width. Zabelin writes that such fur-trimmed letniki were also sometimes worn in the summer. When it was cold, the upper classes would wear a beaver false collar [ozherel’e], a round collar worn over the head and with an opening in front with hidden fasteners. The fur used on a collar was always dyed black in order to highlight the whiteness of the face.

Letniki were sewn, depending on the wearer’s wealth, from a wide variety of fabrics: cotton, silk, and even cloth of gold. The most used was damask. For the lining, they would use a lightweight fabric, often taffeta.

Diagram 33 can be used to make any of the female outfits. The only difference is in the sleeves.

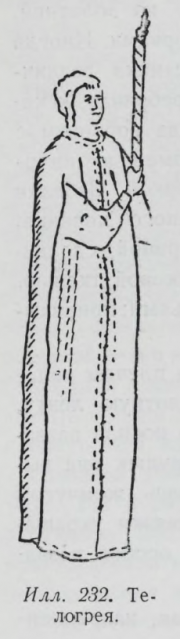

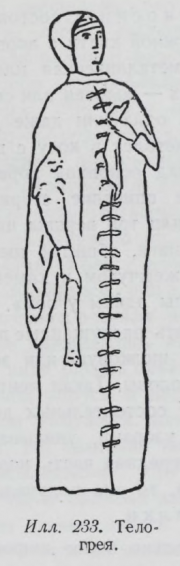

The telogreja [Illustration 232, 233; pl.: telogrei] was a wide outdoor outfit of the opashen’ type, with buttons or clasps in front. The telogreja was cut long, almost to the heels; its width in the helm was similar to that of the letnik, 425 cm. The sleeves reached to the floor, but at the armhole there were slits so that the arms could be extended through, and the sleeves themselves were often tied behind the back, or one could be threaded through the other behind the back to make a loop. Telogrei were made of relatively heavy fabric, for example, damask, satin, ob’jar’, zuf’, or brocade. At the collar, opening and hem, they were edged with gold or silver braid. In the 17th century, they were also made with pockets.

The order of clothing which Zabelin calls “middle wear” includes the false fur coat [shubka nakladnaja] [Illustration 234]. These coats were sewn in a typical cut, with the hem width obtained by inserting gores. Its length was to the floor, as with other garments. The collar was straight with a small opening at the chest which was closed using buttons and tabs. The sleeves were exactly the same as with telogrei. If this item was to be worn outside the house, then it was made of thick, heavy silk, gold velvet, cloth of gold, etc. At home, it was made from broadcloth of various colors without a lining, and with satin trim only at the hem. False shubki were worn to solemn occasions at the table, because of which they were called table coats [shubka stolovaja]. Typically the false shubka was without any particular ornamentation; the wealthy would wear it with a false fur collar when outside the home.

In the wardrobe of the tsaritsa or tsarevna, the shubka played the role of royal regalia. In such situations, they were made from expensive cloth of gold, and it became wide and flowing in cut. The sleeves were cut long to the palm, and their width at the wrist reached up to 35 cm. The sleeves, hem and opening were richly decorated, with gold braid and trim. It was fastened in front using 15 (or more) expensive buttons. The front was also sometimes decorated with alamy, round gilt plaques, hammered or forged. Alamy also could refer to round cut pieces of fabric, decorated with pearls. The shubka was worn richly embroidered, with alamy and with a wide collar that corresponded to the royal diadima.

At weddings, the letnik and false shubka were mandatory wear for the bride, as well as for the matchmaker and other participants in the ceremony. Zabelin writes on this topic: “The wedding ranks, matchmakers and boyarinas sitting for the rite are required to dress up for the ceremony in yellow letniki, in crimson shubki, in veils and beaver collars; in the winter, instead of a veil, they wear a hood. The bride herself, prepared for the rites, was in a coronet, and also in a yellow letnik and crimson shubka.” “On another day after the wedding, the newlywed and the bojarinas were dressed in white letniki. The wedding rite allows the bride to dress herself in long sleeves.”

The opashnitsa or rospashnitsa was identical to a letnik, but open at the hem. It was made from silk or gold cloth, brocade, or satin, with a lining of taffeta or striped fabric. Zabelin describes the opashnitsa or privoloka as a short mantle made from expensive gold fabric, decorated with goldwork embroidery, frequently with images of animals and birds, with peredtsy and buttons. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the privoloka was called a podvoloka.

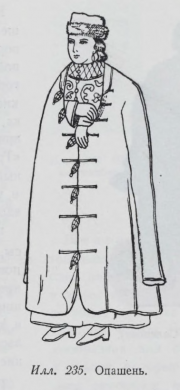

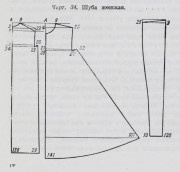

The opashen’ or okhaben’ was a flowing dress of expensive fabric, typically of crimson broadcloth [Illustration 235]. The figure was cut straight, with gores inserted at the hem. The collar was beveled, as if it were a continuation of the angle from the hem. The sleeves were flush with the hemline. On these fabric okhabni, as decoration, they used a line of gold and silk lace. The buttons sewn onto an opashen’ were quite large. A fur okhaben’ was called a shuba [Illustration 237; Diagram 34]; lace was not used on these. The collar on these was a turned-down lapel.

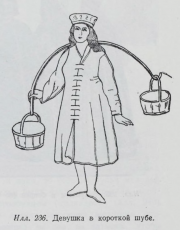

Peasants wore sheepskin coats or shuby similar to those of men.

The kortel’ was a fur-lined winter outfit, covered in light fabric (taffeta, damask) or bare, but always richly decorated with voshvy and a podol’nik (a strip of material of a different color, sewn to the hemline). In cut, the kortel’ was similar to the letnik, but it was only worn in the winter and was always fur-lined. It is not known whether the sleeves were normal length or long, but the voshvy are mentioned in contemporary descriptions.

The torlop was a fur item similar to the kortel’, but with wide sleeves.

Women’s Headwear

Unmarried girls wore their hair uncovered about their shoulders; the upper classes wore it artfully curled. They also wore hair braided into a single plait tied with a ribbon or a knot, sometimes with a gold tassel or pendant called a kosnik or nakosnik. The braid would start at the temples. The hair was braided as loosely as possible, in order to make the braid seem as thick as possible. The hair was divided into many strands and intertwined with golden thread. Wealthy families would also weave strands of pearls into the braids.

The kosnik or nakosnik consisted of a silk or pearl tassel with a brooch. Sometimes, the brooch was replaced by a metallic plate of a different form, which for the rich was made of gold or silver, two which was attached either one or even two cords with braids. The kosnik was woven into the braid with the help of a cord located over the primary tassel. Zabelin gives the following description of a medieval kosnik: “A triangle 2-3 vershki[13]jeb: A medieval Russian measure, 1 vershok = 4.45 cm. wide, made of thick cotton, embroidered with silk, and decorated in patterns with pearls and stones; they were woven into the end of a braid from one corner.

In order to hold their hair down to their shoulders, young women would wear a silk or gold band tied about their head. This was called a head band [perevjazka]. For upper class girls, this would have been embroidered in bright colors, and decorated with pearls and stones. If the front of the band was particularly richly decorated, then it was called a chelo or chelka. A similar band, but wider and fastened to a stiff lining, was worn such that one side was slightly behind the head; it was sometimes cut in the shape of a sickle, and would have wide ribbons attached to the ends and tied in the back in a large fan. In the 15th century, this type of perevjazka came to be called a chelo kichnoe. A headband which encircled the head in the form of a continuous strip was called a wreath [venok, Illustration 236]; a wreath that was carved with a pattern of battlements or teeth at the top was called a circlet [venets, Illustration 239]. The wreath was worn on an uncovered head, and was worn exclusively by young girls. Together with a circlet they would wear rjasy, long strands of pearls and stones, hung from either side of the face along the cheeks, and also a podniz’, a net of pearls with pendants on the bottom to decorate the forehead. In The Everyday Lives of the Russian Tsars, Zabelin gives a complete description of the circlet of the young tsarevna Irina Mikhajlovna, including the rjasy and podniz’. A circlet with a rounded top, sometimes composed of individual sections which were fastened at the top by precious stones, was called a koruna, and was worn only by the royal family [Illustration 242].

Married women were not allowed to show their hair to anyone. She would cover it with a podubrusnik or a povojnik. The podubrusnik was made of light silk or cotton fabric, and although the exact cut is not known, it has been proposed that it was a type of taf’ja or light hat which covered the hair. In the back, the podubrusnik was attached to a so-called podzatyl’nik, a small piece of the same fabric which covered the nape. Over the podubrusnik, she would wear an ubrus [Illustration 234], a thin linen veil, satin stitched with either silk and gold, or silver, and with pearl pendants. The ubrus was wrapped around the head in beautiful folds, held together with special pins with pearls or gemstones, and with embroidered ends which would hang on either side. Ubrusy could also be made of lightweight silk. The typical colors were white and purple.

Along with the ubrus, they also used a different type of headwear called a volosnik. This was a net, woven or braided from gold, silver or silk thread, weighed down by a hatband of purple, red or white taffeta or satin, richly embroidered with silk or gold, with studs, pendants, etc. depending on the wealth and tastes of the wearer. Items with particularly rich and intricate designs were called oshivki [sing.: oshivka]; those with simple designs were called volosniki or just “nets”. To the front of an oshivka was sometimes attached pavrozy, thick pleats in the form of ruffling, which bordered the face and peeked out from under the ubrus and other headwear.

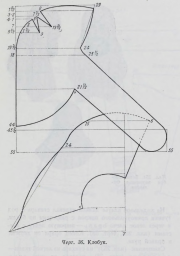

The main headwear of a married woman was the kika [Illustrations 241, 243; pl.: kiki]. At weddings, the kika, along with the podubrusnik, podzatyl’nik, ubrus, and volosnik, was part of the woman’s marriage regalia and occupied the primary role among them. A kika was typically made from a soft crown, surrounded by a podzor, a band of varying width and form which encircled the head. The podzor typically widened toward the top. The crown was most often made from simple fabric, pasted with fish glue to heavy paper. The top was covered with bright silk fabric, often satin. The front of the kika‘s podzor, located near the face, came in a wide variety of sizes and forms, and would be heavily decorated pearls, gems and all kinds of intricate finishes. Kiki also used podnizi and rjasy as described above, typically of made of pearls, which would best highlight the whiteness of the face. Attached to the back of the kika was the so-called zadok, made of velvet or sable fur and divided into three parts (or “petals”), one of which covered the nape, and the other two covering the cheeks and side of the face. The kiki of the tsaritsas were distinguished by their extreme lavishness. For example, amongst the kiki of Tsaritsa Evdokija Luk’janovna is described: “A kika of crimson satin, and upon it a field of gold, upon which there are stones in settings, and sapphires, rubies and emeralds; the podniz’ was of Ormuz seed pearls, and the back and sides were of black velvet” (Zabelin).

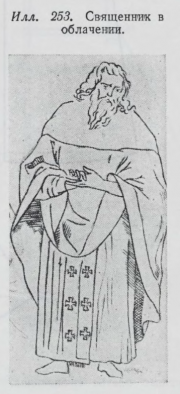

Hats [shljapy]. Amongst the historical documents which have survived to our day, we find descriptions of women who over their ubrusy wore round hats with rounded crowns. Descriptions of these hats are also found in descriptions of the royal treasuries. These were primarily worn in the summer. These were made of lamb’s wool; moreover, the brim was two or more vershki wide. According to Zabelin, to give these hats a glossy finish, they were coated on the outside with a special composition of white lead and fish glue. The brim was lined with smooth or gold satin. It was decorated with special cords of colored silk with pearls and embroidered silk bands, expensive pearls and precious gems.