It has been a while since I’ve posted. My summer was full of non-SCA projects, including my gardens, renovating my deck, and painting my porch. I’ve also been busy as the Social Media Officer for my Kingdom. But, I’m starting to get back into research, and today I would like to post my translation of an article I recently read. It is an overview of different styles of medieval Russian jewelry from the 9th-13th centuries, written by N.V. Zhilina and based on finds from burial sites throughout Rus’. It covers the various styles of different periods in the era prior to the Mongol invasion.

Styles of Medieval Russian Jewelry from the 9th-13th Centuries

A translation of Жилина, Н. В. «Стили в древнерусском ювелирном искусстве IX–XIII вв.» Знание. Понимание. Умение. 2012 (1), с. 92-105. / Zhilina, N.V. “Stili v drevnerusskom juvelirhom iskusstve IX-XIII vv.” Znanie. Ponimanie. Umenie. 2012 (1), pp. 92-105.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/stili-v-drevnerusskom-yuvelirnom-iskusstve-ix-xiii-vv]

Medieval Russian jewelry are both works of applied art and items which are studied using archaeological methods. As a result, along with studying their typology and technology, it is necessary to consider the artistic side of their evolution and their changes in style — their consistent use of certain compositions and decorative elements to create an artistic image based on various jewelry techniques. The formal, decorative side of style may be complemented by specific ideological content or sociological attitudes.

The best items of jewelry from the royal and wealthy tradesmen-artisan classes are found in hoards from 4 particular chronological groups: 1) the 9th century to the early 10th century; 2) the second half of the 10th century to the end of the 10th century; 3) the 11th through the early 12th centuries; 4) the 1170s-1240 (Korzukhina, 1954, pp. 20-32). These fully characterize the jewelry arts of Medieval Rus’ in the pre-Mongol period and are able to fully demonstrate the characteristics of applied art of this time. In general, the principle of stylistic study of jewelry as an understanding of the stylistic unity of attire of the time was put forth by G.F Korzukhina (idem., pp. 14-31). This study of stylistics needs to be carried out at a more specific and detailed level (Zhilina, 1998).

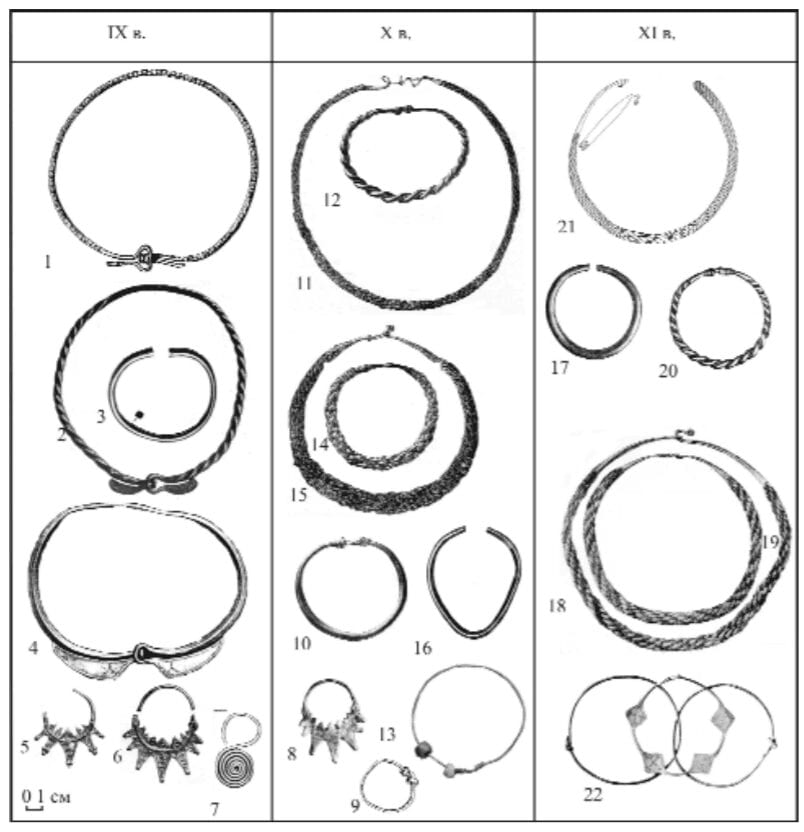

Treasure hoards from the 9th century contain silver forged and cast items — bracelets, torcs, temple rings, signet rings — which are artistically similar to folk art. Items of this type are closer to metallic rather than precious jewelry. These heavy items were worn in groups, an abundance of metal that remained as a legacy of the archaic culture of the Iron Age, when metal served as a primary indicator of a person’s wealth and properity (Illustration 1: 1-7).[1]References to the sources of illustrations are given by indicating the ID number of the hoard.[2]jeb: I have omitted this information and the accompanying tables here for readability.

[jeb: Across the top, the columns are labeled: 9th century, 10th century, 11th century.]

Bracelets and torcs were made from drawn or hammered wire. Their aesthetic influence is created mainly from the very shape of the products themselves, created by their cast or wire construction. Surface ornamentation is either absent or comparatively elementary. Stamped geometric and circular decorations and incised zigzag lines were applied. Nevertheless, at this stage, a number of ornamental motifs are seen, and are later combined with more subtle techniques.

By the mid-9th century, we see foreign jewelry re-imagined stylistically to match folk aesthetics. Radial temporal rings are shaped based on Byzantine jewelry, including star- and grape-cluster-shaped earrings. The decoration itself has been flattened, becoming more of a wide bow (Illustration 1, items 5 and 6). Thin lines of [jeb: stamped?] grain-like decoration cease to be seen (Illustration 1, item 8). (Shinakov, 1980; Zhilina, 1997a, 2007a; Grigor’ev, 2000)

The traditions of folk jewelry extend through the 10th and 11th centuries in the same categories as seen in metallic jewelry. Twisted and woven forms are developing (Illustration, items 9-22). The use of Eastern, silver dirham coins as pendants on necklaces results in the production of pendants which imitate their appearance. A desire to display one’s wealth stimulated this artistic phenomenon (Illustration 2, items 27-29, 32).

A stabilization of the technological methods of Russian art in the 10th century brought jewelry-making to a higher level, stylistically-speaking. The primary style tied to professional artistry was the use of granulation (Zhilina, 2005).

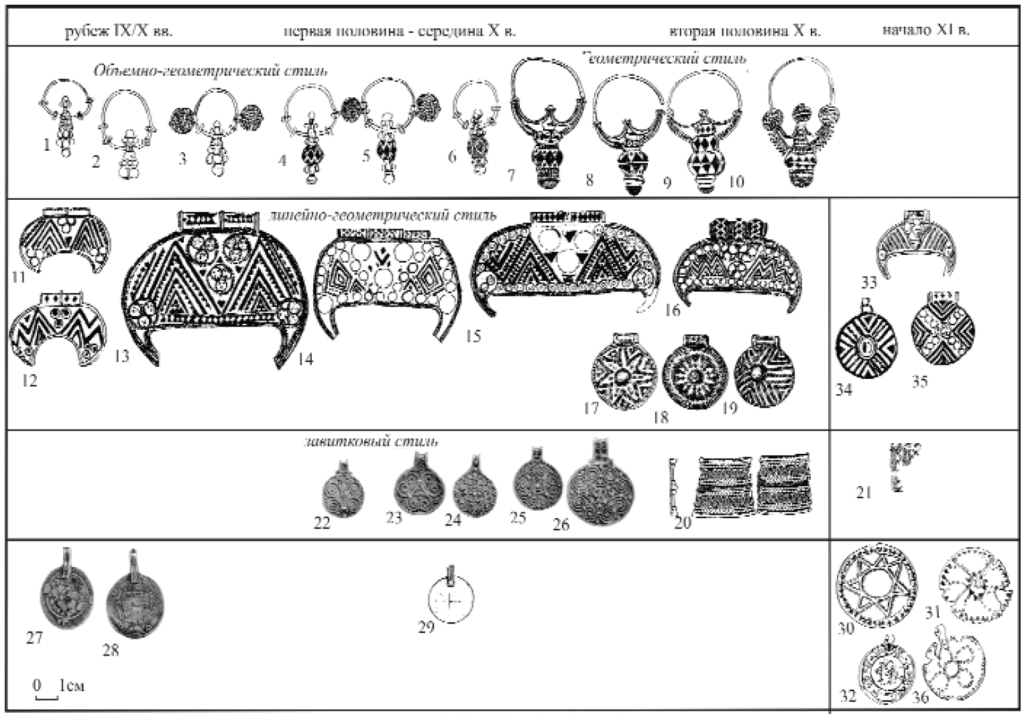

The voluminous-geometric style is seen in Rus’ from the late 9th through the first half of the 10th centuries (Zhilina, 2008, pp. 101-104, illustration 2). It used a wire-frame construction of the body of the item, created by soldering together filigree elements which also serve as ornamental elements — pyramids, granules, cones, rings, etc. (Illustration 2, items 1-6).

[jeb: The labels read: (across the top) Turn of the 9th/10th century, First half-Mid 10th century, Second half of 10th century, Early 11th century; (row 1) Voluminous-geometric style, Geometric style; (row 2) Linear-geometric style; (row 3) Curly style]

Furthermore, filigree jewelry is characterized by a solid embossed body with overlaid surface ornamentation in linear-geometrical and geometrical styles. The main element of the linear-geometrical style is lines of granulation, combining geometric elements with backgrounds that are completely covered in granulation. This style appeared in the 1st-3rd quarters of the 10th century. It is particularly well represented on lunitsy[3]jeb: Crescent-moon shaped pendants. and hemispherical medallions (Illustration 2, items 11-19, 33-35). The “clean” geometric style, which uses only rhombuses and triangles, arose toward the end of the 10th century. Early on, this style used small geometric elements created using a minimal number of granules (Illustration 2, items 15-16). This geometric style was used for the precious attire of Eastern, Western and Southern Slavs (Zhilina, 2007b). Filigree made from stamped wire was used relatively simply by local artisans, for borders, spirals, and to mount central elements onto the body of an item. In 10th century Rus’, we also encounter items in a curled style from Scandinavia — beads, and necklace pendants. The primary element of this style was two-dimensional curves, ranging from a single curve to S-shaped and spiral curves. These curves were used to create heart-shaped motifs and rosettes, forming borders and cells (Illustration 2, items 22-26). These curled style items were not yet manufactured in Rus’ (Duczko, 1985; Zhilina, 2008, pp. 130-142). In the late 10th-early 11th century, we see occasional examples showing a mastery of techniques using corrugated wire and flattened filigree (Illustration 2, items 20-21).

The artistic processes in 11th century jewelry are the most complex and interesting. The cultural and religious orientation of Rus’ changed sharply after the acceptance of Christianity in 988. An assessment of fragmentary and individual items of jewelry from this time of change allows us to separate items which preceded or followed this change.

In the early 11th century, the existence of jewelry in the linear-geometrical and geometrical styles come to an end. At this time, we also see the last uses of stamping with punches on flat items of jewelry[4]A punch was a thin stamp in the shape of a rod, the end of which carried a decorative motif or element. The stamping was performed by striking this punch with a hammer.(Illustration 2, items 30-31). In the mid-11th century, jewelry production underwent an inevitable pause associated with the loss of relevance of these previous styles and the need to develop new forms of jewelry. The poorest time period was, definitely, the second quarter of the century. Troves from this time preserve items of dismantled jewelry serving as material resources (Illustration 2, item 31).

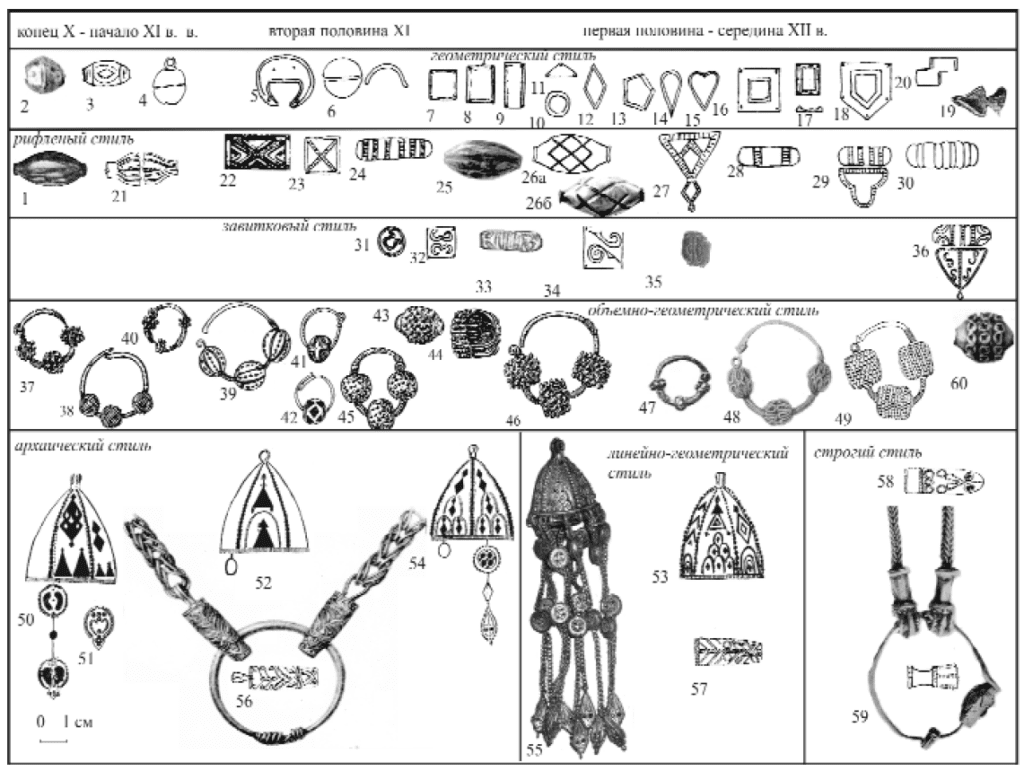

One of the first techniques to emerge from this period of stagnation was the use of embossing to create the body of jewelry (Illustration 3, items 1-2). In the second half of the 11th century, various techniques of embossing developed, the most original of which was the use of corrugation (Illustration 3, items 21-30). The grooved style which emerged from it started out by imitating the geometrical and curly styles of filigree (Illustration 3, items 3, 21-22, 36, 31-36). The first items of jewelry of this new generation were the ribbed beads, covered longitudinally with embossed corrugation, which became cemented in Russian production until the 12th century (Illustration 3, items 1, 21, 25). Corrugation was also used to create the ryasnas used to suspend kolts, a type of decoration that was hung from headwear (Illustration 3, items 24, 27-30).

Slavic burials from the medieval Rus’ period: (37, 41) Pskov Krivichi; (38) Poljans and Drevljans; (39, 40, 42) Vladimir burial mounds; (43, 44) Dregovichi; (47) Knjazhaja Gora, Kiev; (48) Starikovo, Kursk region; (49) Kiev; (51) Novgorod; (52, 59) Staraja Rjazan’; (53) Moscow; (54) Smela, Kiev region; (55) Staraja Rjazan’; (56) Mironovskij folwark, Kiev region; (57) Tver’; (58) Chernigov.

[jeb: The labels read: (across the top) Late 10th-early 11th centuries, Second half of the 11th century, First half-mid 12th century; (row 1) Geometric style; (row 2) Grooved style; (row 3) Curly style; (row 4) Voluminous-geometric style; (5) Archaic style, Linear-geometric style, Severe style.]

Several new forms were created based on older traditions which were converted to the context of the new age. In the late 11th century, there was an attempt to combine the advantages of wire-based and hammered construction, that is, styles of flat and voluminous decoration. Granulated beads, both hammered as well as those based on rings or loops, became a part of necklaces and temple rings (Illustration 3, items 37-46). This jewelry is well represented in burials, are practically missing from 10th and 11th century troves. It appears that their development began in the culture of folk jewelry. Beads and granules are large and rough, but are made from precious metals such as gold and silver, and the use of granulation in itself raises these works above other forms of Slavic jewelry. More delicate works of this form were mastered toward the first half of the 12th century, as seen in a series of three-beaded rings of the highest quality and proven technology found in burial mounds from the 12th-13th centuries (Illustration 3, items 47-49). This became a sort of national element in Russian jewelry, having arisen from grassroots culture.

In the 11th century, based on beads covered with miniature vertical spirals, we can discern the appearance of the Carpet style, characterized by voluminous decoration which completely fills the surface (Illustration 3, item 60).

In the late 11th-first half of the 12th centuries, we also start to see jewelry in a new style of filigree: pectoral chains, discovered in troves from the 11th century, and bell-shaped ryasnas with chains and plaques appear in the layers of early material in troves from the 12th-13th centfuries. These items clearly do not belong to any of the previously described styles of filigree, and are characterized by a combination of hammered and voluminous methods of decoration. This lack of distinct style makes these items similar to folk art, but they are carried out with the highest level of skill. The link between these items and examples from pagan cults is quite tangible (Zhilina, 1996). These marked features lead us to define this style as “Archaic” (Illustration 3, items 50-52, 54, 56).

Byzantine culture introduced into Russian attire the technique of enameling, and gave new impulse to the development of blackening (Makarova, 1975, 1986). The most important new artistic phenomenon was the spread of the use of vegetative ornamentation, using elements such as flowers, leaves, petals, and stems. Russian jewelers gradually and with originality revealed the capabilities of this style for every technique. The initial motif was a sprout of a lily flower, the flowers of which became like leaves as they became more ornamental. Trefoils become half-trefoils, doubled, or otherwise multiplied figures. These plant-based decorations served as the basis for the formation of various other jewelers’ techniques.

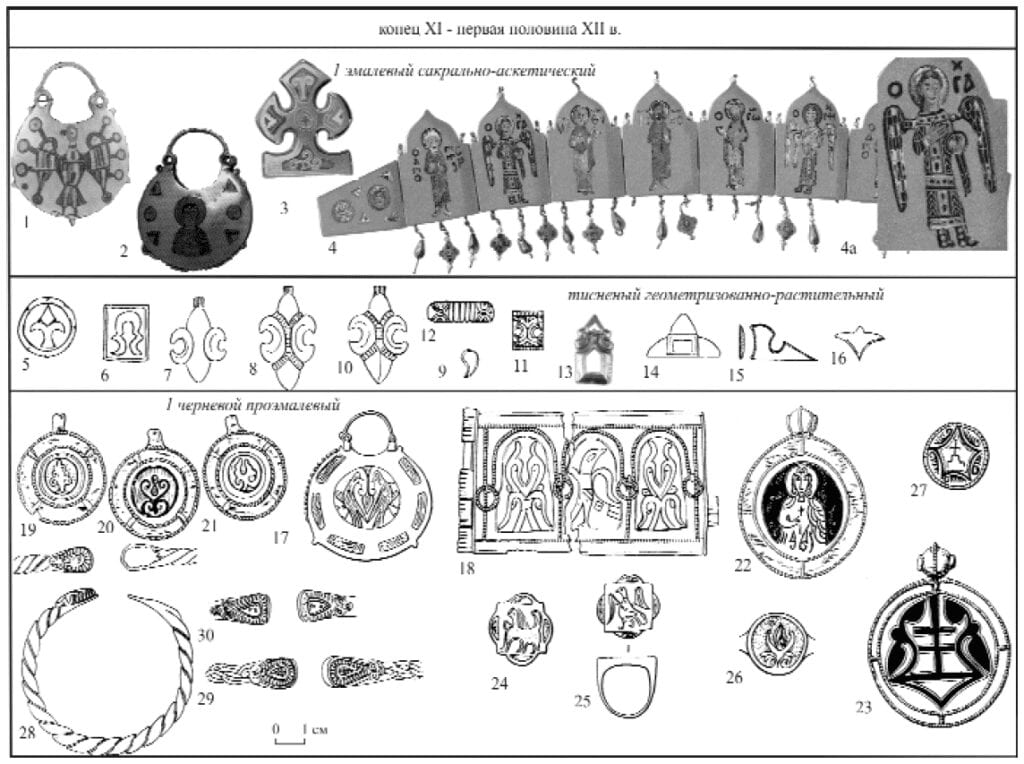

In the 11th century, these new phenomena were not yet wide spread. These subtle jewelers’ techniques were first applied to the decoration of traditional metallic items. The first group of items of Russian production to show signs of blackening, woven and braided bracelets with blackened terminals in a geometric vegetative style, appear in the second quarter of the 11th century (Illustration 4: items 28-30). Interwoven filigree is used, complementing the wire construction (Illustration 1, item 20).

[jeb: The captions read: (across the top) late 11th-first half of the 12th centuries; (row 1) ascetic-sacred style enamel; (row 2) geometric-vegetative embossed style; (row 3) blackened pseudo-enamel style.]

The geometric stage of vegetative decoration is characterized by arranged outlines of plant-like elements, combined with geometric elements or drawn within them. The ornamental division is emphasized by linear borders. The origin of this style is tied to cloisonné enameling, the ornamental elements of which are created by the geometric forms of the cells which are clearly outlined by curved lines (Illustration 4, items 5-20).

The emergence of enameled items in Rus’ occurred in the late 11th and early 12th centuries (Makarova, 1975). O.S. Popova singled out the 1030s-1040s as the period when the ascetic style arose in Byzantine art (Popova, 2006, p. 7). From the 9th to the early 11th centuries, Byzantine cloisonné focused on geometric, static depictions of the members of the Christian Deësis and the saints. Secular items displayed geometric vegetative designs, sometimes with zoomorphic motifs. All items were worked in angular lines, and geometric or curly elements. This same style of enamelling was also the first seen in Rus’, called the static-geometric or ascetic-sacred style. The first items of jewelry were moon-shaped kolts with pearl-like bumps, which were hung from rjasnas made from round plaques depicting the saints, birds, or gryphons; enamel was also used on coronets and medallions depicting the Deësis (Illustration 4, items 1-4).

The first items of nielloed jewelry imitated enamelling; as a result, this first niello style is rightfully called “pseudo-enamel”. This style used similar subjects, compositions and decoration: curly, and geometric-vegetative. From the turn of the 11th-12th centuries, we know of moon-shaped kolts with imitation pearl bumps in the form of small metallic spheres, single-tiered wide bracelets divided by archways into ornamental “icon-cases,” rings with round or rectangular shields, and medallions with inset shields on flat and tubular suspension hinges (Illustration 4, items 19-30).

In the second half of the 11th century and the first half of the 12th century, the geometric-vegetative style also came to be used on embossed items. The most common items in this style are silver plaques which were sewn onto clothes, and fleur-de-lis shaped amulets worn from necklaces (Illustration 4, items 5-20).

In urban material from the 1070s, the first items in an austere, curly style with Christian semantics were found: chains suspended from rjasny. Their appearance was tied to the Byzantine filigree culture, but their wide-spread use occurred in the first half of the 12th century (Illustration 5, item 9).

[jeb: The captions read: (across the top) First half-mid 12th century; (row 1) granulated geometric style; (row 2) austere filigree style; (row 3) curly filigree style, filigree carpet style.]

Jewelry from the richest group of 12th-13th century hordes is subdivided into periods based on stylistic, stratigraphic and typological characteristics. One layer of jewelry belongs to the first half to mid 12th century, and is associated with specific styles: geometrical granulation, stern, curvy and carpet style with wire filigree; and fleur-de-lis shaped designs with enamel, niello, and embossing (Illustration 5).

In the first half of the 12th century, the granulated geometric style became number one priority (Illustration 5, items 2-8). It was freed from small details and becomes defined by strictly-ordered, ornamental compositions: rosettes, lattice, and borders. Remnants of the linear-geometric style are seen in the design of the earliest sun-shaped kolts with large rays (Illustration 5, item 1). A new shape of kolts appears, with rays in the form of crescent moons, and durable types of beads and three bead rings develop. In the mid-12th century, the art of granulation appears in fleur-de-lis-based designs (Illustration 5, item 21). Toward the end of the century, flat granular ornamentation took the place of filigree and openwork constructions.

Filigree styles were dated based on analogies to foreign works and an analysis of the complex of a trove from Staraja Rjazan found in 1822 (Zhilina, 2006). In the first half-mid 12th century, the distribution of the curly filigree style remained in use, as it was quite adequate for Christian artwork (Illustration 5, items 9, 22-24).

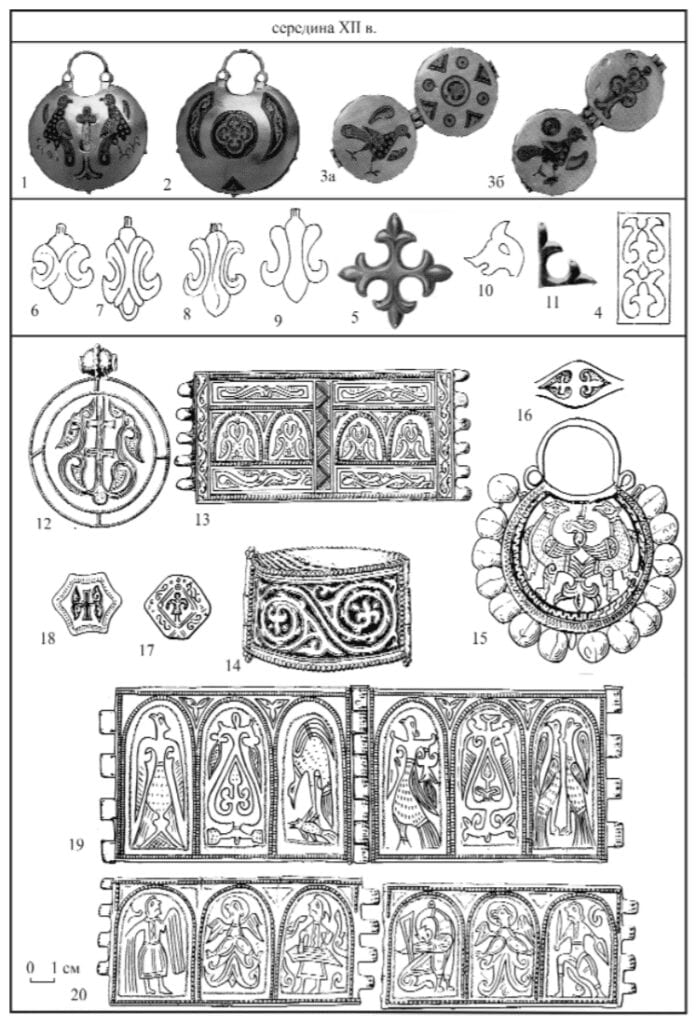

[jeb: The caption at the top reads “Mid-12th century”]

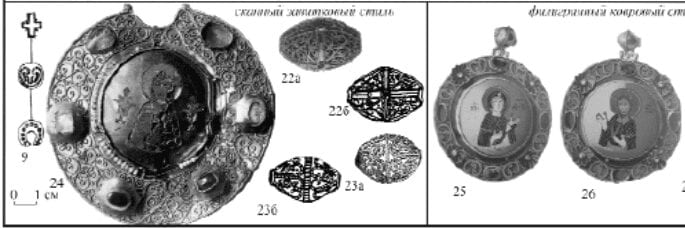

Up until the mid-12th century, the cloisonne enamel was used exclusively in the filigree carpet style to create luxurious framework on jewelry. The gold plate surface was completely covered with various opulent miniature elements without any ornamental design: curls, honeycombs, spirals, cones, and granules. This carpet style was one of the key elements in the formation of the lush gold filigree style of the pre-Mongolian period (Illustration 5, items 25-27).

A second style of Russian enameled jewelry had a slightly more worldly focus (Illustration 6). Around the middle of the 12th century, we begin to see the development of motifs of paired birds or sirens standing on either side of a tree, which form the basis of the “realistic vegetative style” (Illustration 6, items 1-3). Vegetative elements in naturalistic shapes are used. These vegetative motifs also form the basis of the ornamental composition and general form of jewelry. The structure of this composition is not emphasized by a division of the work into zones (Illustration 6).

The second style of nielloed works is similar, but thanks to the greater visual opportunities provided by niello, these compositions look more lifelike (Illustration 6, items 12-20). The technique of embossing based on realistic fleur-de-lis-shaped designs resulted in a magnificent ensemble of sewn-on plaques and necklace pendants (Illustration 6, items 4-10).

In the 12th century, all of these jewelry techniques reached a stylistic perfection based on a harmony of design and their own peculiar technical abilities.

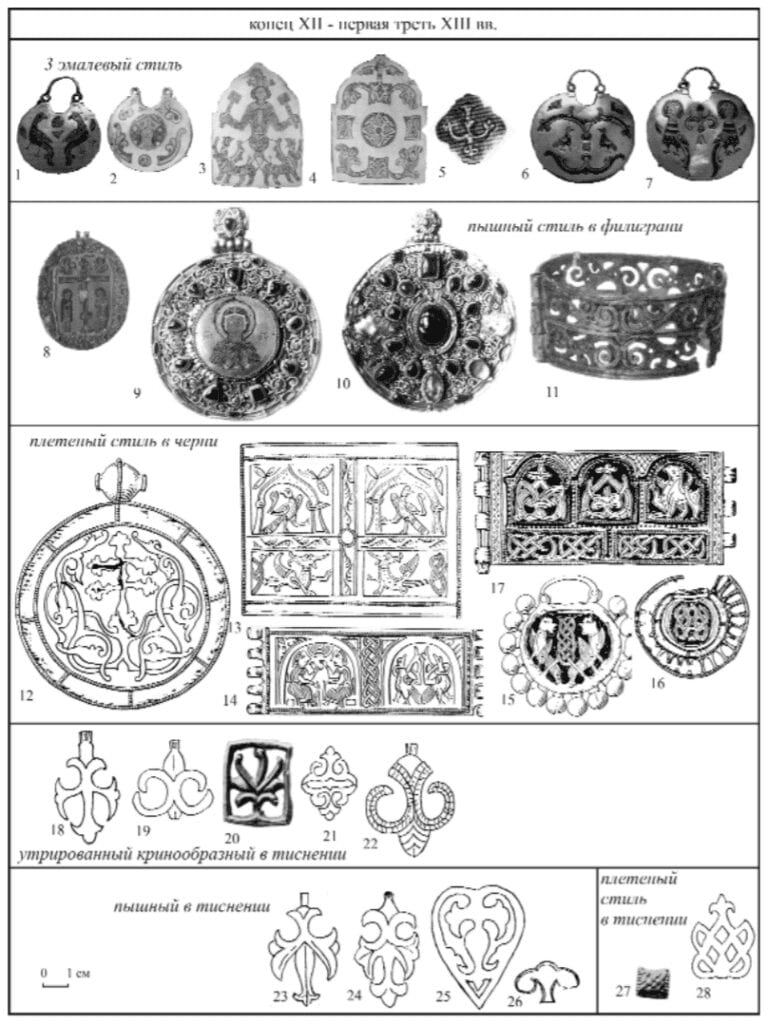

[jeb: The captions read: (across the top) Late 12th-first third of the 13th centuries; (row 1) Enameled style; (row 2) lush filigree style; (row 3) nielloed knotwork style; (row 4) exaggerated embossed fleur-de-lis style; (row 5) lush embossed style; embossed knotwork.]

The stratum of jewelry from the last quarter of the 12th century through the first third of the 13th century was to be the final one for the culture of Medieval Rus’. In enamel and embossed works of this time, fleur-de-lis-based designs of an exaggerated type are widely used. This style is characterized by bizarrely united vegetative elements with curved and elongated details (Illustrations 6, 7). B.A. Rybakov eloquently characterized this stylistic phenomenon as ornamental “ribbons” (Rybakov, 1987, pp, 590-591).

We begin to see at this time the increased use of enamel in worldly items, and on enameled kolts and coronets we see depictions of crowned individuals: holy princes, Alexander the Great, alongside paired sirens (Illustration 7, items 1-7). Enameled medallions have luxurious frames in lush filigree. The main ornamental element is a voluminous spiral curl, with loops rising and tapering towards the center, and superimposed with small simple curls. The best examples of these are settings from a trove found in Staraja Rjazan’ in 1822 (Illustration 7, items 8-10). Based on the lush filigree style, a flat spiral design arises, which in the 14th-15th centuries would become the base for the formation of the spiral style (Illustration 7, item 11).

In embossing and niello work, we see the advent of the knotwork style. This is the third style of niello-work, and is the most original. Knotwork is joined with fleur-de-lis and zoomorphic motifs, along with subjects and scenes of princely and pagan life.

The first stage of knotwork design is characterized by a sporadic interweaving of elements placed around the periphery of the work in the form of knotwork borders (Illustration 7, items 12-13). In the second stage, knotwork becomes a compositionally-important element for the presentation of the subjects. The personages are tightly interwoven, and the borders are intricate and harmonious (Illustration 7, items 14-15). In the final stage, there is an “absorption” of zoomorphic and vegetative elements into the knotwork (Illustration 7, items 16-17). This third stage coincided with the spread of easier methods of preparing plate metal for niello through embossing around the end of the 12th century (Makarova, 1986, p. 91). In embossing itself, we likewise see the widespread use of exaggerated vegetative (Illustration 7, items 18-22), lush (Illustration 7, items 23-26), and knotwork styles (Illustration 7, items 27-28).

The stylistics of late 12th-early 13th century jewelry is characterized by excess and a somewhat eclectic busyness. Time was ripe for a new stylistic development, but this was not destined to occur for some time. The growth of Rus’ jewelry was interrupted by the Tatar-Mongol invasion. Further achievement in Russian jewelry would have to wait for the period of Muscovite Rus.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | References to the sources of illustrations are given by indicating the ID number of the hoard. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | jeb: I have omitted this information and the accompanying tables here for readability. |

| ↟3 | jeb: Crescent-moon shaped pendants. |

| ↟4 | A punch was a thin stamp in the shape of a rod, the end of which carried a decorative motif or element. The stamping was performed by striking this punch with a hammer. |

Nice post! I will be downloading some images to look at closer for sure. =)

Thanks! The original PDF scan didn’t have great resolution. 🙁 But the images are good enough idea of what’s going on.

Very intriguing, thank you.