The article traces the history of origin of ecclesiastical embroidery in Ancient Russia, the use of works of embroidery in the design of Christian worship and decorative furnishings of the temples, and the process of creation and artistic features of medieval Russian artistic embroidery.

The Genesis of Ecclesiastical Embroidery in Ancient Russia

A translation of Валькевич, С.И. “Генезис вышивки «Лицевое шитьё» в Древней Руси.” Научный журнал КубГАУ, 85(01), 2013: 1-12.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

The article in the original Russian can be found here:

http://ej.kubagro.ru/2013/01/pdf/29.pdf

The processes and phenomena that form modern art have deep roots in traditional culture. They are of particular importance in times of economic restructuring and of social infrastructure. The legacy of many centuries, assimilated by the Russian people, became their artistic heritage and formed medieval Russian art. A historical study of the culture of artistic embroidery in Russia suggests that, both in theory and in practice, there was a cyclical process of conversion of folk culture.

Embroidery is one of the most ancient forms of artistic creativity. Its history hearkens back to a distant era when embroidered images were heavily associated with magic and were valued as a type of “amulet” guarding against evil forces. Samples of embroidery with themes of Slavic pagan mythology from both ancient archaeological digs, as well as from peasant embroidery from the 18th and 19th centuries, suggest that this kind of art was widespread in the pre-Christian period. Medieval Russian examples in museum collections in Moscow, Sergiev Posad, St. Petersburg, and Torzhok hold a special place in Russian embroidery. In their methods and appearance, they verge on the art of medieval Russian painting, and is rightly referred to as “needle painting.” The historical development of Russian embroidery has not yet been sufficiently studied. The origin of ecclesiastical embroidery in Russian appears to be the Byzantine tradition.

By the 7th century, religious matters played a significant role in Byzantine society. Orthodoxy was tightly connected to nation. Monasticism and wealthy monasteries began to develop, as well as the influence of the clergy on the souls of believers, the respect surrounding the clergy, and the veneration of holy icons owned by those monasteries (Dil’, p. 53). Byzantine trade spread to the furthest borders of Asia and through the mediation of the Avars, Bulgarians, Hungarians and other peoples, penetrated deep into western Europe. Through the Turks, Pechenegs, and Kumans, they reached other tribes through the northernmost regions of Russia. The best products from these countries were delivered directly to Byzantine markets, including silk fabrics, raw silk, linen, coarse and fine woolen fabrics, dyed and patterned scarves, leather, leather products, furs, weapons, metals, precious stones, pearls, and much more (Vejs, p. 459). This state of commerce in the Byzantine Empire favored the spread of sumptuous decoration in churches and palaces.

Byzantium entered into relations with the Kievan state starting in the middle of the ninth century. Russian marauders repeatedly harassed Constantinople starting in 860 (cf. 907 and 941). And yet, Byzantine emperors readily recruited soldiers among these brave warriors, and Rus’ merchants often visited the Byzantine markets. Byzantine nationality already existed by this time. The empire enjoyed religious unity, political power, and a greatness of spiritual life. Above all, it became the great Eastern empire, and for 150 years (from 867 to 1025) experienced a period of incomparable grandeur (Dil’, p. 83). The influence of Byzantine culture also extended beyond the regions under their protectorate. Relations between the empire and Rus’ grew even closer after Grand Princess Olga visited Byzantium in 957 and adopted Christianity (Kostomarov, p. 9; Karamzin, p. 60).

The economic prosperity of Byzantium, its solid financial management, and the significant flourishing of its industry and commerce in the 10th century gave the empire not only power, but also great wealth. Byzantine artisans produced many masterpieces of art, including silk fabrics of many bright colors completely covered with embroidery, magnificent items glistening with enamel, dazzling jewelry made of precious stones and pearls, finely carved ivory, bronze and silver, and glass decorated with gold. These luxurious wonders brought the Greek masters world renown. Trade developed extremely well. Byzantium elevated the wealth of the entire world through the activities of its merchants, the power of its fleet, and the rich possibilities of exchange enabled by its ports and grand markets (Dil’, p. 88). The Byzantines regarded art as materialized sensual reflections of spiritual archetypes, and endowed the objects themselves with “true” secret meaning. Along with explicit functional practicality, they also had symbolic purpose. Both religious items and items of secular ceremonial use, such as imperial regalia, were imbued with multiple meaning (Kul’tura Vizantii, p. 520). The powerful influence of Byzantine art spread throughout the world — in Bulgaria, Rus’, Armenia, the south of Italy. Constantinople was the shining center of this wondrous blossoming, as the capital of the cultural world and as a queen of beauty. Behind its powerful defensive walls, the “Devout City” contained incomparable magnificence. Hagia Sophia, the harmonic beauty and opulent ceremonies amazed all who attended. The Sacred Palace, reflecting the ambition efforts of ten generations of emperors, embodying unheard of magnificence. The Hippodrome, serving as the arena hosting all kinds of pageants to amuse the populace. These were the three centers toward all life in Byzantium gravitated. Along with this, a multitude of churches and monasteries, magnificent palaces, rich markets, and masterpieces of ancient art filled the squares and streets, and turned the city into a glorious museum. Only 10th century Constantinople could boast of owning the 7 Wonders of the World as had been known by the ancient world. Foreigners from both West and East dreamt of Byzantium [sic] as the only city in the world filled with golden radiance (Dil’, p. 91).

The conversion of Kievan Grand Prince Vladimir to Christianity at the end of the 10th century was a decisive event. The end of the 10th century (980-1015) culminated complete unification of the Eastern Slavs into the state borders of Kievan Rus’. The old pagan religion of the Eastern Slavs reflected a variety of religious ideals, and as such, the ideology of various echelons in the development of primitive Slavic society. This Slavic paganism did not well fit the interests of an emerging class of feudal lords (Mavrodin, 130). By the time of Svyatoslav [(ruled Kiev 945-972)] and Vladimir [(ruled Kiev 980-1015)], a considerable body of Christian literature written in Old Slavonic already existed in neighboring Bulgaria, completely understandable to all Russians. But, the princes of Kiev were slow to adopt Christianity as, according to Byzantine theological and legal views of the time, this would predicate the transition of any newly converted nations to vassal dependence on Byzantium (Rybakov, p. 397). But, in 988, Byzantine emperor Basil II received an army of 6000 mercenaries from the Grand Prince of Kiev, to help with the suppression of feudal uprisings. For this, Grand Prince Vladimir demanded the hand of a Byzantine princess in marriage. He also at this time seized the city of Cherson, and from there, he dictated his terms to the emperor. He wanted to intermarry with the imperial house, marry a princess, and convert to Christianity (Dil’, p. 84; Rybakov, p. 397). Emperor Basil II gave in to the insistence of the Grand Prince, and convinced him to be baptized. Vladimir was baptized in Cherson (989), and then baptized his people in Kiev. Vladimir’s son Yaroslav (1015-1054) continued and completed the work begun by his father: he turned his capital Kiev into a rival of Constantinople and one of the most beautiful cities in the East. A group of Poles who visited the capital of Rus’ left behind an interesting description of Kiev, preserved by the historian Titmar: “In the large city which was the capital of that state, there were more than 400 churches, 8 shopping areas, and an extraordinary conglomeration of people…” (Rybakov, p. 411).

With the advent of Christianity in Rus’, and the large number of churches and monasteries embellished with finery and ceremony decorated with embroidered items which followed, there arose a particular branch of artistic needlework — ecclesiastical embroidery [litsevoje shit’jo, lit. “facial embroidery”], or so-called needle painting, depicting state and church leaders and Biblical and Gospel stories. Ecclesiastical embroidery formed under the direct influence of Byzantium, but flourished greatly in medieval Russia. Once acquainted with this style of needlework, Russian craftswomen eagerly mastered its methods and technique (Khudozhesvennoe shit’jo, p. 14).

Ecclesiastical embroidery of this period, which was dominated by a religious outlook, received primary importance. Along with icons, it was given an important role in the social structure. These works typically feature images of saints with scenes from their lives, evangelical or Biblical scenes, and borders with similar images or ornamentation, and with embroidered liturgical or supplemental inscriptions. These works are constructed from expensive silk fabrics and silver, gold, and later gilt threads. Convents were renowned for their embroideries. By the 15th century, monasteries became the focal points of various artistic crafts such as the production of items with ecclesiastical embroidery and goldwork.

Ecclesiastical embroidered works were used in the decoration of the Christian church and the decoration of its shrines. Patron saints were embroidered on church vessels, clergymen’s clothing, covers displayed beneath icons [peleny], altar cloths and burial shrouds, and curtains for the royal doors. Banners and epitaphia (large icons embroidered or painted with the image of Jesus Christ or the Holy Mother lying in their tomb) used to decorate sacred ceremonies, and embroidered iconostases to accompany people on long journeys or on military campaigns. Valuable embroidered items were given as gifts to clergy from other Orthodox countries.

These embroidered works were distinguished by the complicated process of their creation. Sometimes several artists would be involved in the production of a single item: “masters” [“znamenschiki“] — icon artists [ikonopistsy] and artists who specialized in illuminators [travschiki] and calligraphers [slovopistsy] “celebrated” [znamenili], that is, drew out the images, backgrounds, and words to be embroidered. The images were drawn out onto paper and transferred onto fabric, or sometimes they were painted directly onto the fabric. For this step, they used ink, soot, white lead, minium [red lead], and other paints. These masters were usually professional icon painters, illuminators and calligraphers. Once the master’s cartoon had been applied to the fabric, the design was outlined in white thread and then embroidered.

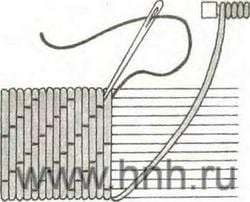

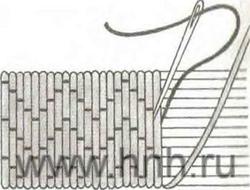

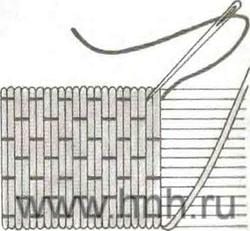

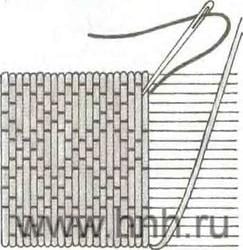

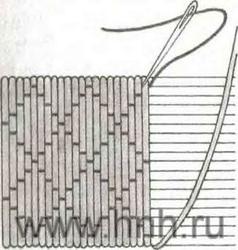

Creating an embroidered work was a time-consuming and lengthy process. It began with the choice of fabric to serve as the background and foundation of the work. The selection was influenced by various factors. The body and borders were typically embroidered on monochromatic fabrics, such as taffeta, damask, satin or velvet. It fell to skilled needleworkers to do the embroidery. They used both silk thread, as well all sorts of gold threads, including spun [pryadenye, literally, “spun thread,” possibly passing thread?], “wrapped” gold [skan’, modernly called Japan gold], “drawn” wire [volochenye, possiblycouching thread?], gimp cord [kanitel’], bullion [truntsal], and gold plate [bit’, literally, “to beat”]. Embroideries were also decorated with pearls, precious stones, and gold and silver beads decorated with niello, engraving, chasing, and enamel. Just as diverse was the technology of needlework. Embroidering with multicolored silks, Russian needleworkers would try to emulate either the smooth, colorful surface of the icon, or the satin surface of the fabric. For this type of work, very smooth stitches [atlasnyj shov, typically translated as “satin stitch”, but doesn’t make sense in context] were suitable, of which there were two varieties: split stitch, where the needle would pierce the middle of the previous stitch; and satin stitch [glad’] where the stitches were placed immediately next to each other. Usually this method was used to stitch the faces, and later by the 15th century, sometimes the entire composition was thus embroidered. From the 15th to the beginning of the 16th century, faces are sewn using light colored silks of a single tone. Starting from the middle of the 16th century, shading was introduced along the outline and around the eyes, using silks of a darker color than the main color, and the stitches typically followed the contour of the design. Starting from the 16th century, multicolored silks began to be replaced by gold and silver threads. Where gold and silver threads were sewn down continuously, couching patterns varied widely, among which the brickwork [klopets], diagonal rows [kosoj ryad], and zig-zag [gorodok, literally, “little village”]. [jeb: see diagrams at the bottom of the page] The outline was typically sewn in low relief over couched strings [po verevochke]; a string was first attached following the contour of the design, and then gold or silver threads were couched back and forth over the string.

The person (typically, the face) was embroidered using different shades of fine, sand-colored silk; clothes and everything else was embroidered using silk, silver, gold, and later gilt threads using various stitches. Sometimes a thick linen or cotton fabric was placed under the golden thread to provide relief. Often the embroidered piece was decorated with precious stones and trimmed with pearls. For durability, when embroidering on silk, they would reinforce the silk with dyed linen and then sew a lining onto the piece.

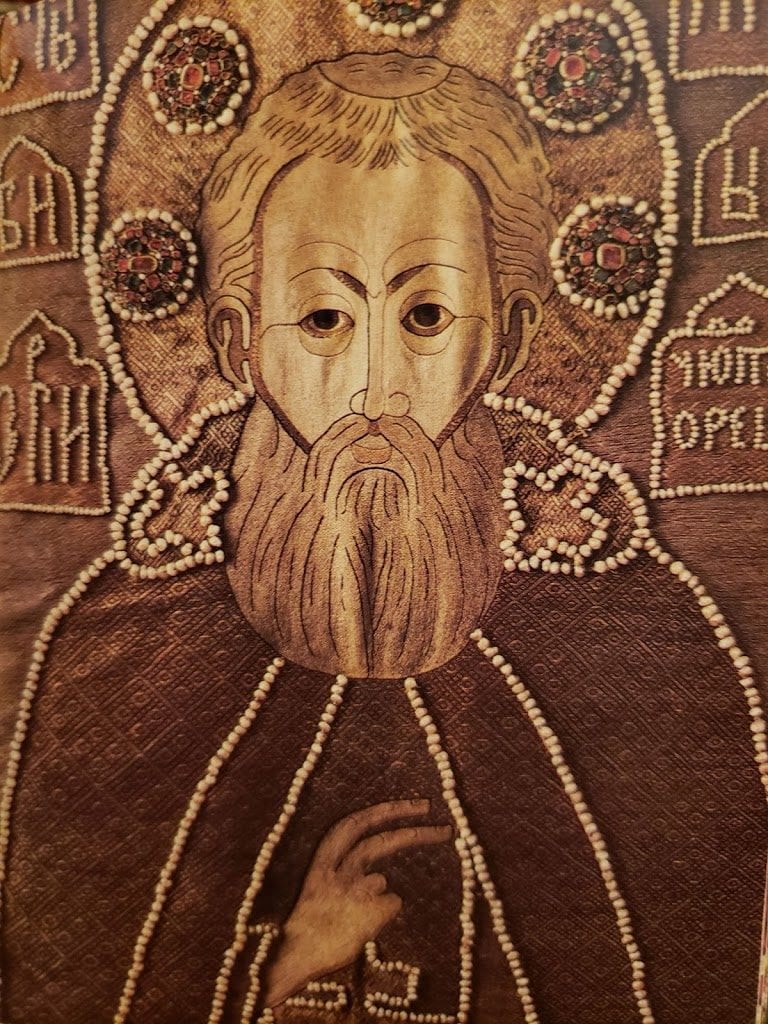

Works of ecclesiastical embroidery were highly valued and carefully preserved. It is possible to trace this through the numerous and varied contributions to large monasteries of embroidered items. The collections of ecclesiastical embroidery in the historical-architectural art museums/reserves of Zagorsk, Aleksandrovskaya Slaboda, Kostroma, and others are of inestimable value. Embroidered items were often accompanied by supplemental inscriptions indicating the time of their creation, the intended recipient, the name of the donor, sometimes the reason for the contribution, and in rare cases, even the name of the needleworker. For example, in the Contribution Book of the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius, there is the following entry: “7027 (1519) – on the 16th day, Vasily Ivanovich, Grand Prince of all the Russias, granted the contribution of his brother, Prince Semyon Ivanovich, 30 rubles.” The sovereign, Grand Duke Vasily Ivanovich, made a contribution recorded in the donation book of the 83rd year (1574-75): “A black altar cloth, on which is embroidered the likeness of the Miracle-Worker St. Sergius, the crown is sewn with gold, around the crown is situated a single strand of pearls, and then is laid a smoky stone. The veil is blue, and the center is grey, and a cross of pearls is placed upon it, an inscription near the cross and near the Vision is written in pearls. On the same icon cover are 14 stones on situated on taffeta. The first veil is written in the books; the damask icon cover is blue, around is a circle of cherry; the image of the Miracle-Worker Sergius is embroidered with gold and silver, and on the Miracle-Worker, 24 stones; around the shroud of the Miracle-Worker Sergius is covered with pearls. There are two shrouds in the books” (Vkladnaja kniga, p. 26). [jeb: See image here.] Early works of the 16th century still retain the character of the pictorial style echoing the icon school of Dionysius and his students; but at the same time, gold and silver embroidery was introduced, laid out with colorful silk forming small ornamental motifs in imitation of imported cloth of gold. They are already more modest, but still have pearls and precious stones, mainly decorating the haloes of the saints and the inscriptions.

A new important stage in the development of ecclesiastical embroidery can be traced through the example of the workshop owned by the Staritsky princes, the closest relatives of Ivan the Terrible. Concentrated in this workshop were, perhaps, the best artists and needleworkers, creating a special embroidery school whose works later served as subjects for imitation. Here they created monumental Great Aers with multi-figured compositions and complex inscriptions. In the Godunovs’ royal workshop, works of ecclesiastical embroidery were turned into jewels through the abundant use of pearls, precious stones, and gold and silver pellets of various shapes and sizes, decorated with niello. The decorations were always subject to complex artistic goals.

Numerous items made in the workshops owned by the famous merchants, the Staritskys, have been preserved. The museum in Zagorsk houses a burial shroud called “Sergius of Radonezh, with scenes of his life,” made in 1671, 183cm x 67cm, inventory no. 400. Sergius is depicted full length in monastic robes. [jeb: see closeup image of this work at the bottom of this page.] His right hand is held before his chest in a gesture of prayer; his left holds a folded scroll. The Trinity and nineteen hagiographical scenes are depicted around the border. The faces and hands are satin stitched in light grey silk, shaded with greyish-brown silk. The background of the central section, the border, clothing and halos are all covered with gold and silver thread couched down with barely noticeable silk stitches. The primary couching patterns are a separated diamond pattern [razvodnaya kletka, literally, divided cell] and diamond pattern [yagodka, literally, “berry”]. All of the image outlines, folds of the clothing, and around the inscriptions are decorated with large, medium, and small pearls. In Sergius’ halo, there are 5 plaques [zapony] with enamels, rubies and emeralds in gold settings (along the rim of the stones). The lining is of lilac satin. The date when this piece was created can be established from its entry in the Contribution Book of 1673 (Vkladnaja kniga, p. 769): “On the 11th day of July, year 179 (1671), Anna Stroganova, the widow of Dmitriy Andreevich Stroganov, and his son Grigorij Stroganov, and his daughter Pelegaja Stroganova gave to the Trinity Monastery a shroud [dedicated] to the Miracle-Worker Sergius, sewn with gold and silver; Sergius is decorated with 5 rubies in bezels, and near the stones there sparkle rubies and emeralds; near the crown and in the fields and the outfit, there are the life of the Miracle-Worker Sergius, and at the bottom there is an inscription in small pearls; the lining is of tausin [a reddish-blue] satin” (Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo, p. 83).

[jeb: Here is an image of the shroud decorated with the image of St. Sergius of Radonezh with scenes of his life, 1671. Khudozhesvennoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow: Sovetskaja Rossija, 1983, p. 203.]

The names of donors found on embroidered works, along with other historical written sources, indicate that the courts of princes, boyars, and the wealthy had their own embroidery workshops called solaria [svetlitsy] where specially-selected and well-trained embroiderers would work. Embroidering liturgical items was considered to be a pious activity. In more or less every wealthy house of Medieval Russia, there would be a solarium [svetlitsa], a brightly-lit room especially dedicated to women’s handiwork. In these workshops, sometimes as many as 50 craftswomen would work under the guidance of the mistress of the house, herself often a skilled needleworker. Most important of these solaria at the end of the 15th century were those of the Grand Princes of Moscow, which by the middle of the 16th century were nicknamed “the Tsaritsa’s Glittering Chambers” [tsaritsyny svetlichnye palaty]. The needleworkers included tsaritsas, princesses, boyarinas, merchants’ wives and common craftswomen. The subtlety of execution, the elegance of design, and the exquisite use of color are exemplified by the items embroidered by Maria Miloslavskaya (first wife of Alexei Mikhailovich), considered to be a unique monument to ecclesiastical embroidery. Embroidery was a time-consuming and lengthy process; several master needleworkers would often contribute to a single piece. Works of ecclesiastical art produced by these numerous solaria were donated to both churches and monasteries.

In particular, many works have survived from the 15-17th centuries. From these, it’s possible to trace the evolution of this art form, which preserves the best traditions of earlier times. At this time, more so than in previous centuries, embroidery was done using silver and gold threads, sewing techniques became more complex and advanced, and pearls and precious stones were used more heavily. Many of these embroidered items are no longer seen as mere embroidery, but as decorative and precious masterpieces. The Zagorsk State Historical Art Museum preserves items from some of the best art workshops of the 16th century. These include contributions from Grand Princess Solomonia Saburova, Vasily III, the famous workshops of the Staritsky princes and Tsaritsa Anastasia Romanovna, as well as the royal workshop of Boris Godunov, completing the evolution of embroidery in the 16th century.

The 17th century saw an end to the development of medieval Russian artistic embroidery. Ecclesiastical embroidery started to largely imitate precious icon covers [oklady]. Its images, with rare exceptions, lost their former inner significance. The crisis of religious worldview made itself felt, as many religious works acquired an emphasized secular character. On the borders of works, facial images are typically replaced by luxurious ornamentation, dominated by floral or geometric that are complex and intricately developed (Khudozhestvennoe shit’jo, p. 20).

Works of ecclesiastical embroidery testify to the close cooperation of visual and decorative principles. However, in its development there is a clear tendency to a constant strengthening of the latter role, due to the very nature of the art of embroidery. This tendency was expressed in the complicated nature of the stitches, the patterns of haloes and garments, and in increased attention to the decoration of the border. Through these works of ecclesiastical embroidery, one can get an idea of the national character of embroidery and feel the depth of the folk foundations of this art, which is so closely associated with ancient painting and peasant embroidery. The organic fusion of these traditions, carried out by the nation’s talented craftsmen, provided this art with a unique originality and deep content.

Cited Sources

- Vejs, German. Istorija kul’tury narodov mira: Kostium. Ukrashenija. Predmety byta. Vooruzhenie. Khramy i zhilischa. Obychai i nravy. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Eksmo, 2004.

- Vkladnaja kniga Troitse-Sergieva monastyrja / izdanie podgotovili E. N. Klitina, T. N. Manushina, T. V. Nikolaeva. Otv. Red B. A. Rybakov. Moscow: Nauka, 1987.

- Dil’, Sh. Istorija Vizantijskoj imperii. / Sh. Dil’. Per. s fr. A. E. Roginskoj pod red. B. T. Gorjanova. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo inostrannoj literatury, 1948.

- Karamzin, N. M. Istorija gosudarstva Rossijskovo. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Eksmo, 2004.

- Kostomarov, N. I. Russkaja istorija v zhizneopicanijakh ejo glavneishikh deyatelej. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Eksmo, 2009.

- Kul’tura Vizantii vtoraja polovina VII-XII vv./V. P. Darkevich. Otv. red. Z. V. Udal’tsova, G. G. Litavrin. Moscow: Nauka, 1989.

- Mavrodin, V. V. Proiskhozhdenie russkogo naroda. Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo Leningradskogo universiteta, 1978.

- Rybakov, B. A. Kievskaja Rus’ i russkie knjazhesva XII-XII vv. Moscow: Nauka, 1982.

- Khudozhesvennoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Moscow: Sovetskaja Rossija, 1983.

Goldwork Stitches

[jeb: http://www.hnh.ru/handycraft/2011-03-16-1 has some very handy diagrams for goldwork stitches and their names in Russian. For those who can’t read Russian, I’ve included and annotated these images below:]

(косой ряд, kosoj ryad)

(шов городок, shov gorodok)

(клопец, klopets)

(по веревочке, po verevochke)

(разводная клетка, razvodnaja kletka)

(ягодка, jagodka)