I recently finished reading a chapter from “The History of Russian Art” on the applied arts in Kiev and the southern Rus’ principalities from the 9th-13th centuries. This article by noted scholar B.A. Rybakov was a lengthy read, but was very interesting in the wide range of examples of applied art, as well as his in depth discussion of the pagan and Christian influences which mixed together on everyday items. He pulls examples from various art forms, including sculpture, embroidery, illumination, jewelry, stone-carving, enamelwork, and Christian symbology (icons, crosses, church decorations) to shed light on the beliefs and artistic tastes of pre-Mongol Rus’.

The Applied Arts of Kievan Rus in the 9th-11th centuries and the Southern Russian Principalities of the 12th-13th centuries

A translation of Рыбаков, Б.А. «Прикладное искусство Киевской Руси IX -XI веков и южнорусских княжеств XII-XIII веков.» История русского искусства. Том I. Москва, 1953, с. 233-297. / Rybakov, B.A. “Prikladnoe iskusstvo Kievskoj Rusi IX-XI vekov i juzhnorusskikh knjazhestv XII-XIII vekov.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1953, pp. 233-297.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. Images labeled “jeb:” were added by me. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://yadi.sk/d/3W8-vpPd3WbPuC. ]

Applied Art in Everyday Life

On the broad squares of populous Kiev, at the noisy royal feasts as glorified by the bylini, in village brotherhoods and conversations, in the palaces of the boyars and the huts of the serfs – everywhere, we see the sparks of artwork. The various items produced by artisans which decorated everyday life and transformed simple items into works of art were called uzoroch’e by medieval Kievans. Uzoroch’e was everywhere; it filled the outer world created by the hand of man, and often this decoration on clothing, the design on a silver bangle, or the carved handle of a ladle can reveal the thoughts of these Russian folk more fully than preserved items of monumental art.

The semi-pagan images in the Lay of Igor’s Campaign, the symbolism of the bylini and fairytales, and the fantastic characters in the white stone carvings of Vladimir may be fully understood only against the backdrop of its multifaceted, rich and exquisite applied art. In the cities of Kievan Rus’, art ceased to be only materialized nameless folklore as it had been in ancient times. Here, the master artisan, with his students and artistic schools, stood out, signing works with his own name. The work of the best goldsmiths was monitored by a chronicler, who wrote an admiring review of one artisan’s jewelry-making skills on the parchment of his books: “He decorates so beautifully that I am unable to describe a single item sufficiently well: for many from Greece and other lands say, ‘Nowhere else does such beauty exist.'”[1]Zhitija svjatykh muchenikov Borisa i Gleba. A. Abramovich, ed. Petrograd, 1916, p. 63.

This Kievan chronicler, admiring the silver tomb of Boris and Gleb decorated with nielloed images of the saints and “various large crystals” in Vyshgorod in 1115, was not alone in his assessment of the Russian artisan. In Germany, a priest named Theophilus from the Helmershausen Monastery near the city of Padersborn, author of a large tract about the techniques of jewelry making (Schedula diversarum artium)[2]Published Vienna, 1873. informs the reader in the Preface of an honored list of countries whose artisans are renowned for various types of artwork. In this list, Rus’ (“Russia”) of the 11th-12th century is listed in second place behind Byzantium as the inventor “of meticulous enamel and various kinds of niello.”[3]idem., p. 9. Furthermore, the Russian jewelers were followed by the Arabs, Italians, French, and Germans.

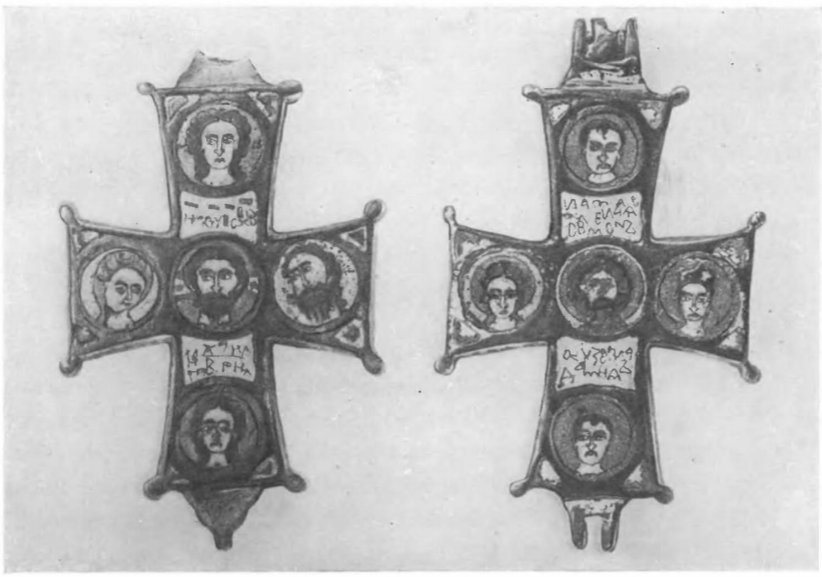

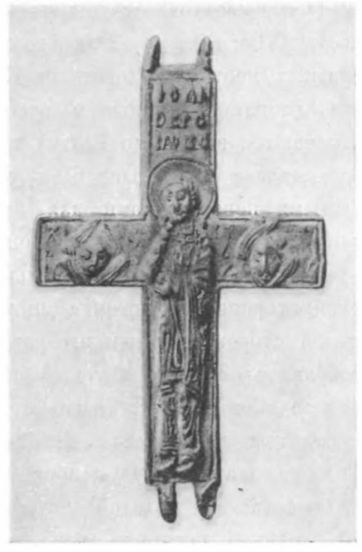

In the sacristy of the the Cathedral of St. Godegard in Hildesheim, there is preserved a folding cross of 12th-century Russian make with an inscription.[4]Mjasoedov, V. “Ierusalimskij krest v riznitse sobora v Gil’desgejme.” Zapiski Otdeleneja russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. 1918 (XII), illus. III-IV. In Constantinople itself, the refined Byzantine Ioann Tzetzes glorified in Greek verse a delicately carved bone pyxis from Rus’. He compared the 12th-century Russian carver to the lengendary Daedalus.[5]Kondakov, N. Russkie klady. St. Petersburg, 1896, p. 80. This gives us confidence to believe the aforementioned review. Indeed, many coming from Byzantium and other countries exclaimed: “Nowhere have we encountered such beauty, even though we have seen the tombs of many saints.” It is a pity that this magnificent work perished, it seems, at the hands of Tatar invaders, as did many other works of Russian art.

Decorative origin permeated all sides of private and social live in medieval Rus’. Social differences amongst the population of the Russian principalities quite clearly had an impact on applied art – on its material, style, and subjects. Items from village burial mounds were made from cheaper materials; in addition, within the villages, we distinguish social and property inequality. Urban items are likewise non-homogenous: there are mass produced items that belonged to simple townsfolk, and items from artisans to the royal courts into which went gold, precious stones, and many months of painstaking labor. Rural art, known to us almost exclusively from metallic items, was permeated by ancient, pagan elements. We can only imagine the wealth of folk, peasant artwork from ethnographic materials: carved wood, marvelous embroidery, painted spinning wheels, beautifully patterned fabrics. We have the right to imagine all of these belonging to the peasants of the 10th-12th centuries. Urban culture is much more known to us, in particular that of the upper ruling classes.

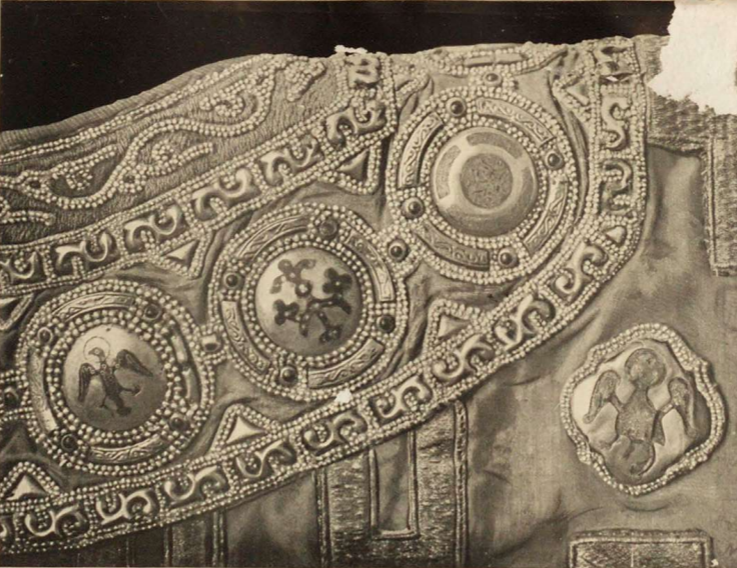

Clothing was sewn from patterned fabric, and the surface was embroidered in colorful silks, gold or silver threads, and dyed wools. Sometimes, the woven or embroidered patterns were produced using a more simple technique – already by the 10th-11th centuries in Rus’, the practice of colored fabric stamping was in use. Silk and gold samite are found not only the graves of wealthy individuals, but even in those of simple townsfolk, and bands are found even in the graves of peasants.

jeb: Part of the sakkos of Metropolitan Aleksey, 14th century. Nikol’skij, V. Drevnerusskoe dekorativnoe iskusstvo. Petrograd, 1923, illus. 1.

jeb: Reconstruction of the pattern from a fragment of gold brocade, 12th century, found in a tomb of one of the princes of Vladimir-Suzdal’. Guschin, A. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi. Moscow-Leningrad, 1936, plate XXIV.

The sumptuous clothing of the boyars was decorated with sewn-on plaques with relief and colored patterns, and with solid rows of seed pearls.[6]Nikol’skij, V. Drevnerusskoe dekorativnoe iskusstvo. Petrograd, 1923, illus. 1. Particularly extravagant, based on medieval depictions, were their outer cloaks, the korzna. These were made of the most expensive imported fabrics – olovir,[7]jeb: An imported purple fabric. samite, and others. The complex fabric patterns, aside from their colorfulness, are also interesting for their subjects: lions, elephants, birds with women’s faces, horsemen, winged bulls and leopards, bright flowers, eagles – the entire colorful world of eastern fantasy shown off on the shoulders of the royal household members.[8]Guschin, A. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi. Moscow-Leningrad, 1936, plates XXIII and XXIV.

Trade in Eastern silk fabrics had by the 11th century almost become monopolized by Russian merchants. Before the Crusades, Rus’ was the most important mediator in trade between East and West. It is not without reason that a French poet from the 12th century, when describing a beautiful woman, spoke of her lovely clothing of “Russian silk.”[9]Spitsyn, A. “Torgovye puti Kievskoj Rusi.” S.F. Platonovu – ucheniki, druz’ja i pochitateli. St. Petersburg, 1911, pp. 240-241. Medieval Russian townsfolk would have constantly seen before their eyes clothing on which Russian patterns mixed with the patterns of Iranian and Byzantine fabrics, which had broad international circulation. Although of these fabrics, only a few fragments have survived to modern day, we can certainly account for their creativity in the works of Russian artisans.

The wide scope of activity by “merchants in gold and silver” is apparent in the world of jewelry making.

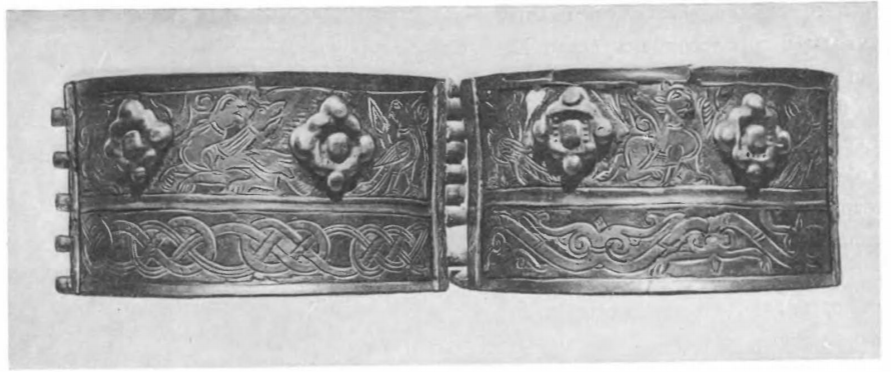

The golden crowns of the Russian princesses were decorated with enamel and pearls. Golden chains depicting birds dangled from the crown to the shoulders, ending in kolty decorated with sirens, leopards, and flowers. Women’s necks were decorated with various types of “grivny,” consisting of necklaces made up of large medallions, as well as various kinds of beads, amulets, lunnitsy and crosses. This was all created subtly and gracefully, twisted with swirls of wire and strewn with the finest granulation. Women’s sleeves were gathered at the wrist by wide silver bracelets, richly decorated with images of birds, centaurs, gusli players, and dancers; their fingers were decorated with rings.[10]Kondakov, N. op. cit., plates I-XIX; Guschin, A. op. cit., plates XV, XX; Khanenko, B and V. Drevnosti Pridneprov’ja. 1902 (V), plates XV, XVI, XXIX. Princes and boyars were dressed in patterned cloaks, and on their heads wore special hats with fur edging and and a patterned top. Their collars and cuffs were decorated with embroidery and metallic thread. Their jackets were buttoned with diamond-shaped clasps or tied with bright cords. Belts were decorated with silver or gold plaques. They word soft leather shoes, dyed in bright colors and decorated with pearls.

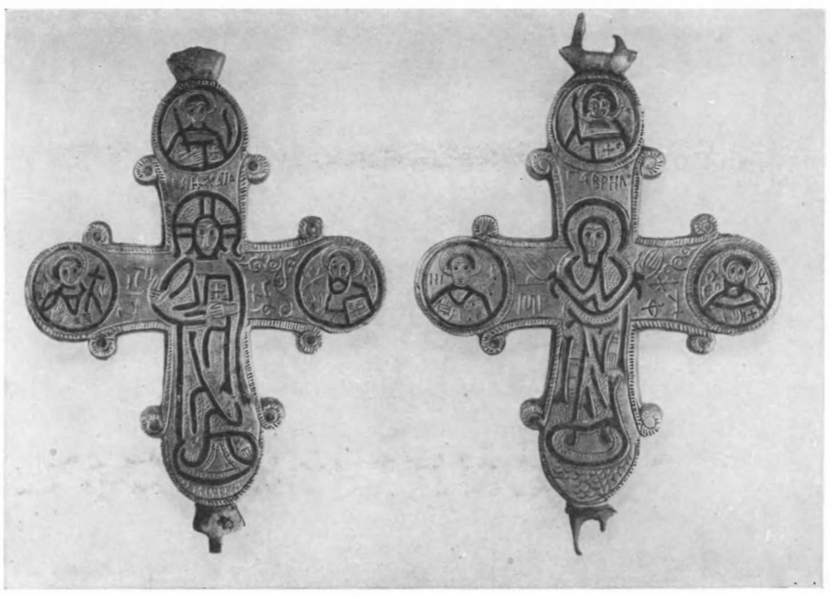

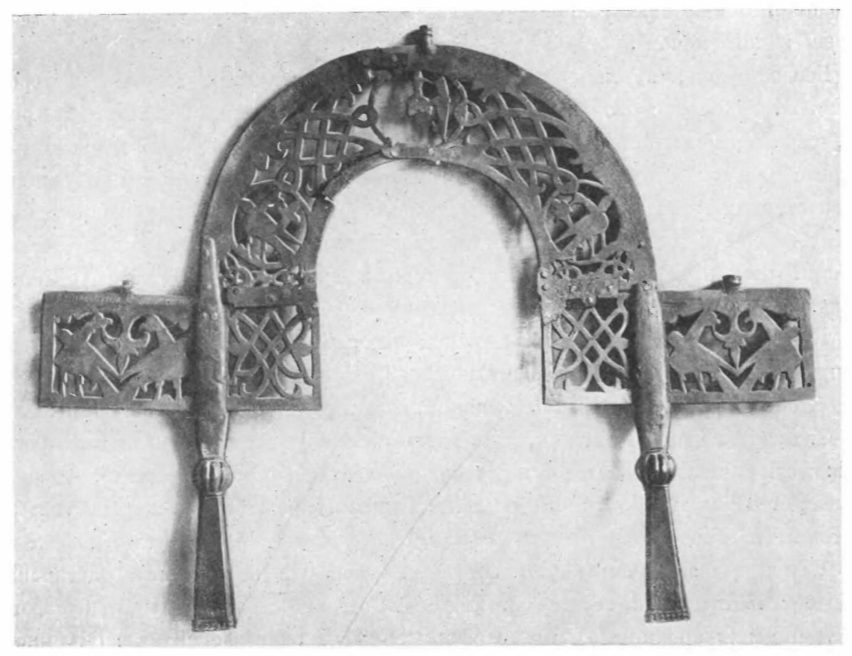

Cast brass arch, by the artisan Konstantin, from the princely castle of Vschizh, near Bryansk. Second half of the 12th century. State Historical Museum.

Cast brass arch (reverse), by the artisan Konstantin, from the princely castle of Vschizh, near Bryansk. Second half of the 12th century. State Historical Museum.

In addition, warriors tried wherever possible to decorate their weapons and armor. Gold- and silver-plated helmets were charged with niellated-silver patterns or images of saints. Suits of chainmail had brass edges. The sword pommels and scabbards of swords were decorated with silver wire, engraved silver, and cast plates (on the ends of the scabbard) depicting birds, masks, rows of knotwork, and animal faces. Flail heads were decorated with relief images of birds. Particularly exquisite are the ceremonial axes of state. Here we find birds depicted on either side of the handle, as well as artfully designed initials (for example, the letter A in the shape of a snake pierced by a sword).

Warhorses, the soldier’s companion, were likewise a subject of the jeweler’s art. Bridles with bronze plaques, with animal heads on the strap ends, silver lunnitsy on their harnesses, saddles made of “burnt gold,” and flowery or patterned saddle-cloths decorated their horses. Bone plaques on quivers depicting quirky, interwoven, fantastic beasts, carved knife handles, graceful folding combs, spurs with miniature gold flowers, battle shields with heraldic symbols, and a multitude of other various designs completed a warrior’s kit.

The prows of warships were decorated with carved dragon heads, held high above the water, and sails were sewn from colored silk.

The “honored feasts” of the prince with his household, as described by the epics, chronicles and even Christian preachers, were a unique exhibition of princely wealth: the tables were set with gold and silver dishes, drinking horns with hammered rims, glass goblets, and carved chalices;[11]Rzhiga, V. Ocherki byta domongol’skoj Rusi. Moscow, 1929, p. 24. the floors were covered with colorful eastern rugs.

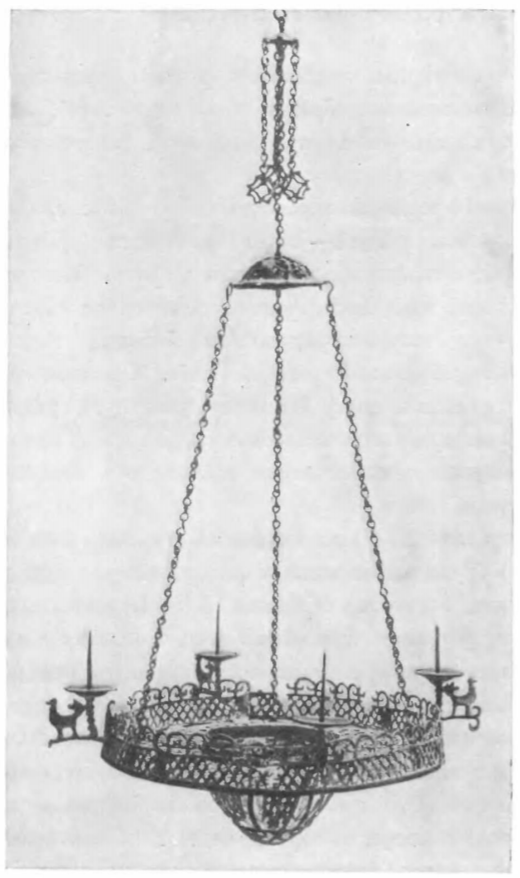

Servants provided water for washing to the feasters in bronze aquamanuals shaped like animals or riders. Next to the tables were incense burners (“ukropnitsy”), also shaped like animals; they were filled with aromatic herbs, their smoke escaped through openwork cuts in the body, and the flames burst through the eyes and ears. The rooms were lit by candles in candlesticks which stood upon animal paws, while large princely feasting halls most likely were also lit by bronze chandeliers with 12 to 16 candles. These chandeliers were also seen in churches from the 10th-12th centuries. Candles were stuck onto the sharp thorns of bronze branches, next to which sat birds, the obligatory companions of fire and the prototype of the firebird.

Feasting dishes were wildly decorated. Various forms of jewelry making were used, and we see various subjects, including motifs from Russian stories and of courtly entertainment: depictions of musicians, wrestlers, dancers, gladiators, and horsemen. Alongside the Russian utensils, we also find foreign items. Sometimes, the caring hand of the prince’s treasurer marked the cost of each item on the bottom.[12]Spitsyn, A. “Dve serebrjanye chashi.” Zapiski Otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii Russkogo arkheoloicheskogo obschestva. Vol VIII, iss. 1, 1906.

Royal treasuries, the repositories of huge artistic and material wealth, were shown to the ambassadors of foreign governments, who admired the abundance and beauty of their contents. Prince Svyatoslav Yaroslavich took his guests to his treasury as if it were a museum. It is possible that the Russian princes had the same custom as the Byzantine emperors, of arranging exhibitions of artwork, weapons and jewelry in the palace on special days. Prince Izyaslav Yaroslavich, when he arrived in Germany in search of allies, amazed the German nobles with the splendor of the items he brought with him.

How the interior of the palaces were richly decorated is not known to us. Unfortunately, we do not know the shape or decoration of their furniture. Beds of yew, golden thrones, tables set in a semicircle, weapons hanging on the walls, carved “princelings” [reznye “knjaz’ki”] — all of these are known only by hints in the texts and illustrations from the Chronicles.

Decorative art also extended to personal items. Boxes (caskets) were decorated with patterned overlays, bone and bronze combs were decorated sometimes with geometric designs, sometimes with depictions of horses, boats with sails, bears, etc. Bone was turned on a lathe to create chess and checkers pieces, and playing dice.

Especially lovingly decorated were books, those “rivers watering the universe” with their wisdom: lines of cinnabar, well-designed capital letters, sparkling illustrations and miniatures with gold and bright colors like enamel, slender branches upon which perch panthers, peacocks, and pheasants, snakes intertwined around lines, and stylized letters under birds. Book covers and bindings were encased in fine silver, with inset precious stones and gold plaques with enamel designs. It was not without reason that contemporaries said that the value of certain book was so great that it was “known only to God,” or that during a fire, books were the first times to be saved.

The cathedrals in the city centers were a focus of creativity. Along with the “artisans of stonework” there were painters, mosaicists, carvers of slate and marble, “smiths of brass, silver and gold” who cast chandeliers, gonfalons, crosses, icon-lamps, and the decorated, holy dishes, all decorated with every trick of the trade. Scribes copied holy books, jewelers clad them with priceless covers, the skillful hands of palace embroideresses embroidered silk podeai, altarcloths [“antiminsy”], and veils which covered the altar. Roofers framed the zakomary with golden lace of pierced brass, and artisans with the finest touch decorated the church doors with acid-etched lines.[13]Gal’nbek, I. “O tekhnike zolochenykh izobrazhenij.” Materialy po russkomu iskusstvu. Vol. I. Leningrad, 1928, pp. 22-31.

It is possible to say that the medieval cathedral was the “Dove-Book” [“Golubinaja kniga”] of folk creativity. A Russian chronicler from the 12th century was justified when he wrote about a new church that it was “filled with all the virtue of the church, and with every subtlety that can be dreamt of.”[14]Hypatian Chronicle, under year 6683 (1175).

Artistic Craft and its Technique

Medieval Russian craft was more or less the foundation upon which all of the material culture of Kievan Rus’ was based.[15]Rybakov, B. Remeslo drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1948.

In villages, specialist smiths provided their fellow villagers with all possible iron items that were necessary for village life, fishing, felling trees, hunts, and warfare. Russian smiths empirically managed to find the form for axes which spread throughout all of Eastern Europe.

Village potters created dishes with the help of a potter’s wheel, and stamped them with their maker’s mark. A favorite Slavic decoration on clay pots was a combination of wavy and straight lines. It is possible that the waves were a persistent symbol of water (a connection still seen in modern times), and therefore was not coincidentally placed on the body of vessels intended for liquids. Gradually by the 13th century, wavy lines were partially placed by a single line. Baking vessels with a folded edge were very consistent and existed until the 19th century. Russian pottery influenced that of the Swedes; it appears that the Varangian squads who came to Rus’ took this form of ceramics back with them.

Jewelry is best able to fully acquaint us with folk applied arts. At the dawn of the Russian state, creation of jewelry in the villages was a women’s art. Women weaved various items from wax cords, which were then covered with a layer of clay, the wax was melted, and it its place, molten metal was poured. The result was a beautiful item that appeared to have been woven from wire. But, already by the 10th century, bronze and silver casting ceased to be a women’s handiwork: it was taken over by male smiths. Along with casting using wax models, they began casting using clay and stone molds.

By studying various items from Russian village burial mounds from the XI-XIII centuries, it is possible to ascertain that amongst burial mounds which were located closely together, one can find items which were cast using one and the same mold, that is, which came from the same artisan’s workshop. By placing the location of these finds from a given artisan on a map, the sales area for that artisan can be determined. The size of these areas was relatively small, with the furthest points no more than 10 kilometers from the workshop where they were made. Here we see justified the English medieval rule, that markets and workshops should be located close enough to the villages that they served, such that a peasant could travel to buy what he needed an return home within a single day. The small sales areas of Russian village artisans completely agree with this condition. At the borders of one region, another would begin. On the territory of the Rus’ lands from the 11th-13th centuries, a multitude of such workshops existed side by side.

Jewelry used in young women’s headwear was particularly elegant. For example, in the land of the Radimichi along the River Sozh, artisans created suspended jewelry based on a ring with a semicircular shield at the bottom. From the bottom and sides of this shield there emerged seven rays, giving the entire item the appearance of a beautiful bronze star. The neighboring Vyatichi had similar temple rings, except in that the ends of the rays broadened and turned into blades. Later, these blades were surrounded by metallic lacework, and inside the circle would be the images of horses or birds. These seven-bladed temple rings, worn in groups of three on either side of the forehead, created a very particular appearance to headwear. Their elegant silhouette would gracefully harmonize with the kokoshnik and the embroidery on their clothing.[16]Artsikhovskij, A. Kurgany vjatichej. Moscow, 1930, pp. 35-47; Rybakov, B. Radimichi. Minsk, 1932, plate IV.

Metalwork was not limited to casting. Cast items were additionally decorated with stamped and engraved patterns. Special punches were used to stamp various designs. Sometimes, the stamping was done using a toothed, steel wheel. A typical stamped design consisted of a triangular crenate form placed in two rows, creating a “wolf’s teeth” appearance. Bronze bracelets from the Novgorod region were particularly sumptuous. As opposed to other regions, where bracelets woven from wire were predominant, here artisans prepared them from broad strips of metal, which left much room for ornamentation. Alongside simple designs made up of circles, triangles, and dots, we also see more complex designs. Knotwork from two bands is seen, sometimes angular, sometimes smooth and rounded. The background around these bands was stamped with a complex dotted pattern, offsetting the smooth bands of the knotwork. Sometimes we find stylized flowers and Eastern S-shaped images of juicy tendrils. Sometimes, it is as if the stamped decoration of a bracelet reproduces the diamond patterns of complex woven fabric.[17]Spitsyn, A. Kurgany Peterburgskoj gubernii i raskopkakh Ivanovskogo. St. Petersburg, 1896, plates III, IV, XII.

On many rural items, we can see an attempt to reproduce urban pieces. Urban filigree patterns are reproduced using simpler casting techniques.

Among materials excavated by archeologists from rural burial mounds, we often find items created by urban artisans. This can particularly be seen from the existence of specially produced items from large Russian cities in the 12th-13th centuries designed for mass production. In the cities, they produced inexpensive items which were distributed by gostebniki (peddlers) to the furthest corners of Rus’; these included slate spindles, crosses with yellow champlevé enamel, etc. Another way these urban items became widely distributed was through the existence in the villages of “young squads” [molodshaja druzhina] which in times of war would gather “in the cities.”

In this way, by the time when urban culture of the 12th-13th centuries had strayed far from the folk culture which had nurtured it, various new connections had been created between urban and folk culture, allowing a famous leveling of art. Urban patterns and international subjects including winged leopards percolated into the countryside as well. This process of interplay between the city and country was interrupted by the Mongol invasion.

Rural applied art was not limited to geometric designs on bronze and silver. As we have seen above,[18]jeb: The author is referring to an earlier chapter on the art of the ancient Slavs. stylized images of various animals, beasts and birds, tightly associated with magical ideas of paganism, were in widespread use in the countryside. Human images figure significantly less frequently in materials which have survived to modern day. They doubtlessly played an important role in embroidered designs, but appear not to have been used on metallic items. Speaking about folk decorative craftsmanship, we must note that every region had its own particular forms of ornament, forms of items, and subjects depicted. Ancient tribal areas, separated by woodlands, still lived their own separate artistic lives, although with every passing century the commonality of the “all Russian” culture became stronger.

Urban craftwork of Kievan Rus’ was quite diverse, multiform and technically equipped. The majority of urban dwellers were artisans. Entire streets and even neighborhoods were named for the type of art which was predominant: Gonchary (“Potters”), Gonsharskij konets (“Potter’s End”), Kozhemjaki (“Leatherworkers”), Kuznetskaja ulitsa (“Smiths Street”), Kuznetskaja vorota (“Smiths Gate”), Plotnitskij konets (“Carpenters Street”), et. al.

Modern-day archaeological excavations have uncovered a multitude of medieval Russian art workshops with their equipment (ovens, forges, tanning vats, anvils, etc.), instruments, supplies of raw materials, semi-finished items, finished goods, and old items brought to the artisan for repair. Judging by these workshops, as well as by data from written sources, it appears that artisans were divided into profession not based on technical skill, but by the end product, that is, by the category of item which was created by a given artisan. There were very few artisans who in their work practiced only one given technical skill, for example only forging or only stamping, or only filigree-work. Each artisan was universal terms of their familiarity with various technical skills: he was able to forge, and to cast metal, and to stamp, and to engrave. He would have had the equipment allowing him to carry out his diverse work. The division of labor is seen in that one artisan created weapons, another quivers, a third women’s jewelry, and a fourth book covers.

In addition to those with such broad categories of specialty, there were also artisans with very specific skills, for example, nail-makers. At the very minimum, there were in Kiev more than 60 various artistic professions. Based on their social standing, artisans were divided into royal artisans [Rus. votchinnye, “fief-based”], which were tied to a princely court, and urban or posad-based artisans. The former category also includes monastery craftsmen. Royal artisans typically worked on spec; they were little concerned with quickening the process of their art and were able to spend long months of meticulous, loving refinement on any given aspect. The majority of items from 12th-13th century treasure troves were made by the hands of such courtly artisans. It was namely these skilled craftsmen belonging to a princely or boyar court who are mentioned in the Russkaya Pravda,[19]jeb: The “Rus’ Justice,” 12th-century collection of Russian laws. which imposes a rather large fine of 12 hryvnia for their murder.

By the 11th-12th centuries, urban artisans were already to a significant degree tied to the market, which required them to find new ways to increase the speed of their production. At the same time, they did not wish to stray too far from their royal brethren in their artistic ideals, and attempted to copy them in the form and finish of their jewelry. Urban artisans had to reckon with both the natural desire to reproduce expensive items of courtly artwork, and with the legitimate concerns of the market to increase the volume of production. In the archaeological record, we are able to see how urban craftsmen were cleverly able to solve this problem. They invented technological methods which allowed them to imitate aristocratic examples without resorting to the same laborious individual creation of each item. Chasing was replaced with stamping items against special convex matrices, and engraving was replaced with casting using special molds,[20]Kondakov, N. op. cit., p. 144, illus. 93. as were extremely complex granulation and filigree.

Particular attention was given by artisans to the production of stamps and casting forms which allowed them to easily create for the market entire series of items, which in appearance were similar to the expensive items emerging from the courtly jewelers’ workshops.

If the rural market for sales had a radius of about 10-20 kilometers, for urban artisans, we need to significantly increase that number; some products might have had a range of 200-400 km, and for others, it may have even been as high as 1000 km. On the even of the Mongol invasion, Russian cities, like those of the advanced countries of Western Europe, began to overthrow the primitive economy of feudal society, breaking up the narrow confines of subsistence farming and entering into a more or less wider market.

Many Russian craftsmen worked with apprentice assistants; some workshops required the participation of several men. We know that even in the 11th century there existed hired labor. Sometimes, between a master and his apprentices, conflict would occur. One such situation is described Patericon of the Kiev-Pecherskij Monastery: a master Alimpius, an icon-painter and jeweler, was upset that his assistants had taken advantage of his illness and accepted private orders. The offending apprentices were punished. This occurred in the early 12th century, around the time when the urban population of Kiev proved itself in the famous 1113 uprising against the boyars.[21]Paterik Kievo-Pecherskoj lavry, p. 171.

It is possible that in larger Russian cities in the 12th-13th centuries, there already existed craftsmens’ guilds similar to those of Western cities, and that the elevation of an apprentice to a master was tied to the production of a specific “item”. In the sacristy of the Novgorod St. Sophia’s Cathedral, there are two 12th-century vessels with exquisite niello-work.[22]Pokrovskij, N. “Drevnjaja Sofijskaja riznitsa v Novgorode.” Trudy XV Arkheologicheskogo s’ezda. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1914, pp. 42-60, plates III-V. One was made in the second quarter of the 12th century; the second was made a bit later, clearly in imitation of the first down to the finest detail. The bottom of each has an inscription according to a specific formula, certifying that the given vessel was created by a specific artisan (the older one by “Bratilo”, the younger one by “Kosta”). It is possible that here we see one of the earliest examples of a “test” for the title of Master Artisan.

The urban artisans who created the shimmering culture of the Russian princedoms were literate. As early as the 11th century, a master potter who created an amphora for wine, signed in the wet clay: “This pot is full of grace.” On stone casting molds, bronze items, and items with enamel, we find the inscriptions of their artisans.

Let us look at a few of the technical methods used by these artisans of decorative art. One of the most important techniques was metal casting. Casting was used to create a wide number of copper/brass, bronze, silver and pewter items, from tiny buttons one’s collar and small pectoral crosses to enormous chandeliers suspended from patterned bronze chains. Items were cast either in stone molds, where an artisan carved the image and had to pay attention to how the image would be mirror reversed when cast, or they were created using previously-prepared was models. Several stylistic features can clarify which of these techniques was used (for example, hair lines seen on seals). Working with wax models, which sometimes preserved even fingerprints on an item, allowed greater freedom and fluidity of form.

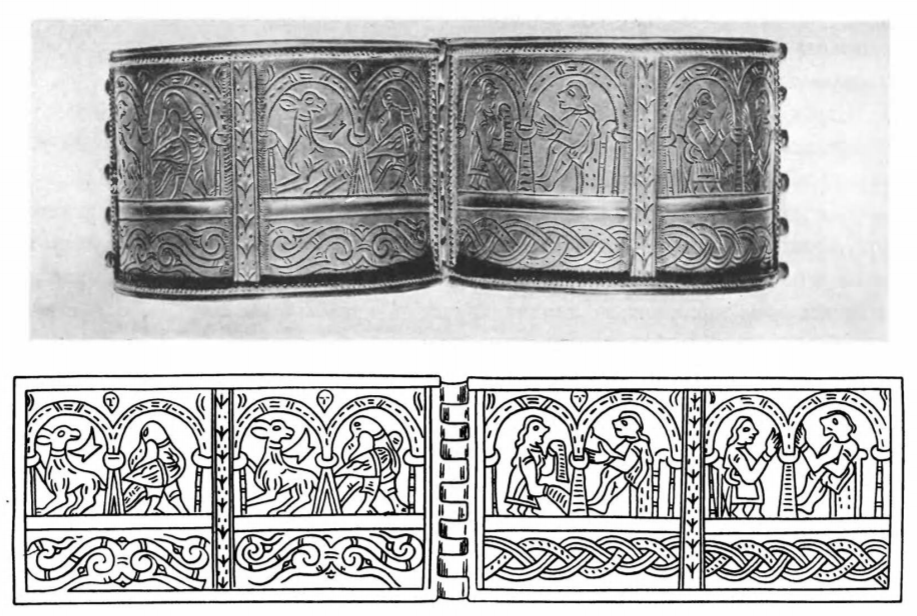

As examples of complex brass casting, see two arches from the princely castle of Vschizh, near Bryansk. Both arches, which are stored in the State Historical Museum, identical (see image above.) The arches are formed from pierced bronze lacework from interwoven bands. Similar woven designs are also found in illuminations, and in jewelry, and in architectural decorative carving. Amidst the weaving, there are three circles with birds inside; above, a bird spreads its wings similar to a heraldic eagle. In the side borders, birds turn their heads softly around to clean their tails, which resemble flowers. Below the circles, within the woven belts, crawls some kind of beast from a medieval bestiary. In the side offshoots, there are two birds, which turn toward the stylized lilies located between them. In order to attach the arches to poles, each has two bushings at the bottom in the shape of long dragons’ heads, holding the archway in their mouths. Similar dragons are known from the architectural carvings from the Vladimir-Suzdal’ princedom.

On the rear of these arches, there is a magical spell, written by the artist onto the wax mold before the casting (possibly to ensure the casting was a success): “Lord, help Your servant Konstantin.” Master Konstantin, who lived in the second half of the 12th century, found good taste and great technical skill.

Along with casting, forging and chasing of silver, brass and gold were widely used. Complex dishes were chased to shape, and silver items were chased for decoration. Artistic chasing was done not only with punches, as was done in the countryside, but also with more complex techniques which created high relief. Repoussé [Rus: обратная чеканка, obratnaja chekanka, “reverse chasing”] was used, where a sheet of silver was placed on an elastic cushion of resin or pitch and was deeply embossed. One of the oldest techniques in jewelry-making was the use of thin twisted wires (filigree [Rus: филигрань, filigran’, or скань, skan’]) and very small grains (granulation [Rus: зернь, zern’]) of gold or silver.

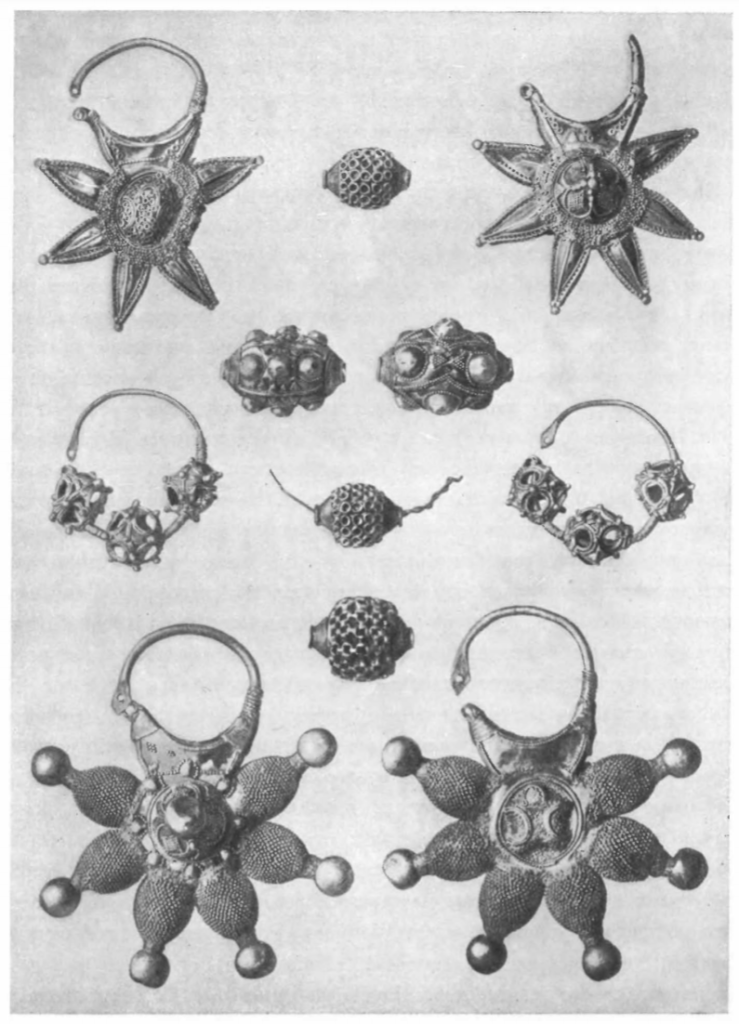

Long ago, even among the artisans of the ancient Slavic princes of the 6th-7th centuries, there arose a desire to reproduce fine Eastern works using filigree and granulation. In that distant past, instead of drawing wire using a drawing plate, it was created with forging or casting, while grains were created by sculpting small balls of wax and then casting them in metal. These imitations were quite coarse. By the 9th-10th centuries, Russian artisans learned how to do actual filigree and granulation, which subsequently became widespread. We see the combination of these techniques on 10th-11th century temple rings from Volynya. Granulation covers the face of the rings, while filigree frames the ring with braided lacework. The hands of the royal court jewelers produced works that are exquisite in their subtlety: granulated lunnitsy, amulets, beads, and star-shaped kolty.

As an example, let us point to the kolty from the 1906 Tver treasure hoard.[23]“Tverskoj klad 1906 goda.” Zapiski Otdelenija russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XI. 1915, plates I-II. Each ring has a semicircular shield (as also seen on temple rings), to which there are soldered six silver cones with spheres on the end (see image above). Each cone was first soldered with a multitude of miniature rings made from thin wire that was 0.02 cm thick. The diameter of each ring is about 0.06 cm. Determining these dimensions required the use of special microphotography. In total for a single kolt, the jeweler had to solder around 5000 such rings. But, this was not the end result for this artisan’s intensive labor: the rings merely serve as pedestals for granulation, and each ring is seeded with a tiny granule of silver 0.04 cm in diameter. As a result, every grain would have shone and created a play of light with the slightest turn of the head.

Naturally, only a court jeweler who had few customers would have been able to expend the time necessary for such work. Urban jewelers created similar kolty using a special casting mold, where each grain had a corresponding small depression in the wall of the mold. Cast kolty were somewhat coarse, but they could be cast by the dozen. Similar “imitation”-style molds date to the early 13th century (see image above), as seen in a find from the ruins of the Church of the Tithes in Kiev. When in 1240 the Kievans defending the city from the Mongols “fled to the church vaults,” the church collapsed, burying the last of Kiev’s citizens. Among them was a master jeweler, who took along with him his most prized, painstakingly created casting forms for imitating granulation-work.[24]jeb: More details about “Kievan”-type imitation molds and this unfortunate master jeweler can be found in this article: Корзухина, Г. Ф. “Киевские Ювелиры Накануне Монгольского Завоевания.” Советская Археология, 14 (1950), с. 217–244. A translation of this article can be found on my blog here: Kievan Jewelers on the Eve of the Mongol Conquest. Similar molds also existed in the 13th century on the Volga, where Batu sent his Russian captives.

A large role was played by filigree in the development of certain forms of ornamentation. Finished items were created from filigree wires where the gold wire itself made up the frame of an object. For example, temple rings with three filigree beads made from thin wire were very common. Despite the comparative simplicity of the artisan’s drawing, the filigree created a high level of gracefulness and lightness. A second use of filigree was patterned filigree, soldered to flat surfaces. Usually these were laid out as spirals into various patterns. Spirals were the most natural form of this use of the material.

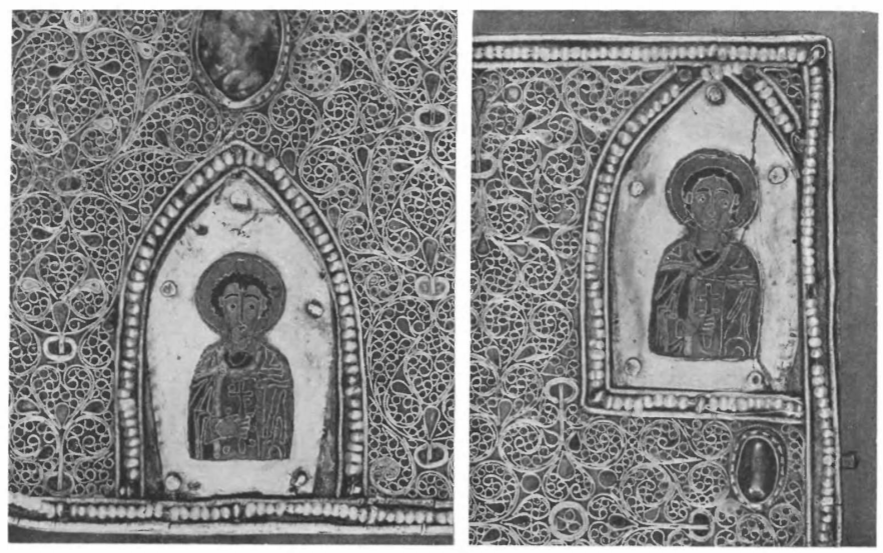

Spiral patterned filigree had great influence on decoration in painting, book illumination, and sculpture. In the second half of the 12th century, spiral decorations were widely used, but by the 14th century they became predominant. The best examples of preserved gold filigree come to us from Staraya Ryazan’.[25]Kondakov, op. cit., pp. 85-87. A famous treasure trove found in 1822 contained filigree bracelets. Pectoral medallions have a unique two-layer filigree: the lower layer lies flat against the gold plate, while the upper later is soldered to the wires of the lower layer, appearing to float in midair. Large gold kolty with depictions of Sts. Boris and Gleb have filigree laid in a beautiful pattern in the form of stylized branches and flowers (see image above). In the 13th century, we encounter heart-shaped formations, with two branches emerging from the same root. An excellent example of Ryazan’ filigree work is a gold frame for a small cross from a 20th century random find (see image above). The frame is decorated with colored stones. Between the, the jeweler placed an entire garden of miniature golden flowers with stems made from golden springs wound from extremely thin wire, and crowns with cups made from five golden petals, each about 1 mm long. In total, the 8 cm space is covered with about 120 such flowers.

One of the earliest Russian accomplishments in jewelry making was niello [Rus. чернь, chern’]. Silver is a very appreciative contrasting material for niello work. The technique of niello appeared in Rus in the 9th-10th centuries, originally as an encrustation, but already by the 11th century, the next level of mixing black and silver areas had been established: the central design was made convex and remained clean, while the background (which was slightly sunken) was completely flooded with niello. The silver field of the image was drawn with a chisel to create details. In the 11th century, the designs themselves were relatively simple and compact, and the niello surrounded them as a dense border (see image above). This later evolved such that the designs became more complex and the niello was gradually displaced. On kolty depicting leopards with flowers in their mouths (Chernigov, 11th century) or winged beasts surrounded by knotwork (12th century), the designs became so complex that the niello remains as only individual lines or spots. Artisans increasingly concentrated on cutting the design with their chisels: soon they began to fill these channels with niello, and the silver and niello fields changed places (much as happened in antiquity when black-figure silhouettes were replaced with red-figures in painting). The field becomes smooth silver, and the design itself was industriously created with niellated contours. By the 13th century, this technique had almost supplanted the original use of niello, which would have appeared crude by comparison.

In the 11th-12th centuries, it was essential to deepen the ground under the niello. This was done by chasing thin sheets of silver on special brass matrices with raised designs (see image above). In the 12 century, the ground under the niello was sometimes roughened to allow better particle adhesion between the niello and the silver. For contour niello, no relief was required, and everything was made possible using the chisel. In the 13th century, the entire surface of a design was diligently filled with strokes of niello, leaving no smooth spaces at all. This contoured technique was used to create monisto[26]jeb: Rus. монисто, a type of necklace worn by women to show off their wealth and social status. They were decorated with coins or flat coin-like plaques. plaques depicting images of saints, rings, kolty, and belt sets.

In some cases where earlier a niellated field would have been used, 12th century artisans found a more delicate solution. For example, on wide silver bracelets which previously used a niello background for the figures in arches, 12th-13th century artisans turned away from niello, and left the background as clean silver, while the figures themselves were gilded.[27]Slovo o polku Igoreve. Moscow-Leningrad, 1934, p. 17. In the annotation, the bracelet is incorrectly attributed to the Mikhailovskij Monastery treasure hoard. The bracelets with dancers and house servants came from an unknown hoard. This noble combination of golden figures and the silver background speaks to the development of refined tastes (see image above).[28]jeb: For more information about these silver cuff bracelets, see Рыбаков, Б.А. «Русалии и Бог Семаргл-Переплут.» Советская археология, 1967 (2), с. 91-116. A translation of this article is available on my blog here: https://rezansky.com/pagan-elements-in-the-decorative-art-of-medieval-rus-rusalia-simargl-and-pereplut/

The technique of gilding has long been known. There existed the ability to heat gold amalgams with a later melting, the so-called “fire-gilding” [Rus. жженое злато, zhzhenoe zlato, “burnt gold”] method.[29]jeb: Also called “mercury gilding”. Gold is mixed into an amalgam with mercury, and painted onto the surface to be gilt. The piece is then heated from below to boil off the mercury, leaving behind the gold. Gold was also used as incrustations. But, the most complex method was depletion gilding using acid [Rus. золотая наводка, zolotaja navodka, “gold laying”]. This method was used for gilding cupric metals and is known to use in full detail from later monastic manuals. This process was used in the 13th-14th centuries to gild church doors. It undoubtedly originated during the pre-Mongol period. Items created using depletion gilding have been found in both Kiev and Staraya Ryazan’.

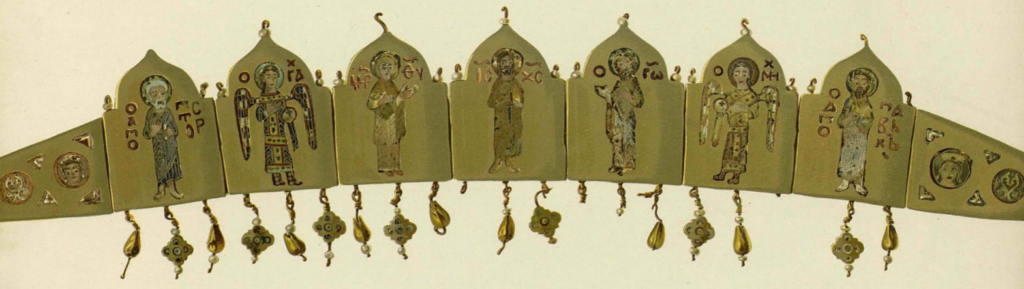

One of the peaks of applied art was enamelwork. Multi-colored enamel with its unfading colors made Kievan artisans famous in Western Europe.[30]Kondakov, N. Istorija i pamjatniki vizantijskoj emali. St. Petersburg, 1892. Enamel decorated golden crowns, kolty and their chains, pectoral medallions, images, pectoral crosses, book covers, and torcs. The masters of enamelwork were the Greeks. From Byzantium, artisans were sent to Germany and Italy. In Kiev, there were enamel workshops belonging not to Byzantine, but rather Russian artisan. The technique of enamel was quite complex. At first, on a smooth sheet of gold, they would work out the general contours of the design, then in these tiny recesses, extremely thin partitions were soldered on edge, intended to separate the enamel of one color from that of another. The resulting cells were filled with powdered enamel, then would be placed into a fire several times. The enamel would melt, and the item would attain solidity. Once the item had cooled, the artist would unhook the gold partitions, polish the enamel, and as a result of this painstaking work which required a huge amount of practice, would create an exquisite and lively work with well-defined borders between each shade and with golden contours of the design (see image above). The fineness of the work by these Kievan artisans is amazing. Sometimes on an area as small as the cross-section of a pencil, they were able to create the image of a woman’s head in a crown, wearing earrings, with clearly defined eyes, mouth, and hair.

Enamelwork was related to the production of glazed ceramics, which was used for paving floors and decorating the walls of buildings. Glazed tiles were decorated with colored enamel to create various patterns. Here we see imitation jasper, geometrical designs, and stylized branches and flowers.[31]Polonskaja, N. “Arkheologicheskie raskopki V.V. Khvojko 1909-1910 godov v mest. Belgorodke.” Trudy Moskovskogo predvaritel’nogo komiteta po ustrojstvu XV Arkeologicheskogo s’ezda. 1911 (1), p. 58.

Many types of craft were not included in this brief overview, but what has been shown is enough to demonstrate the complex techniques of Russian urban arts and the ability of its artists to create fine and beautiful items.

One particular area of decorative art was the decoration of books. Books were written in special workshops, where the oldest scribe would have several apprentices. Whereas the creation of priceless covers were the work of goldsmiths and enamel workers, the ornamentation of the book interior was done by specialized gilders.

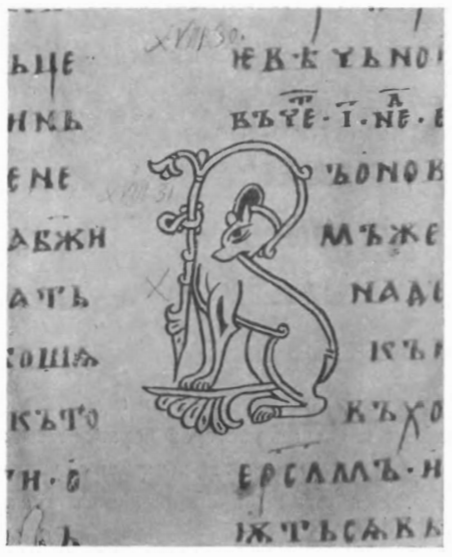

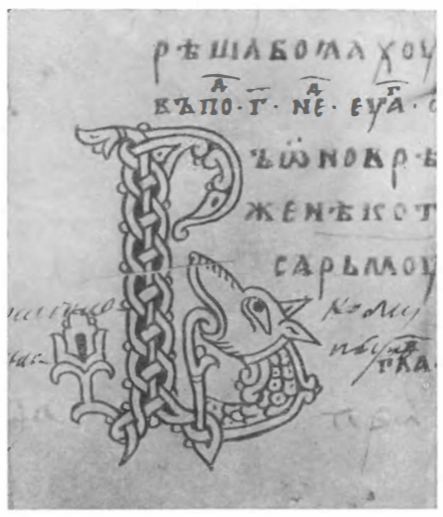

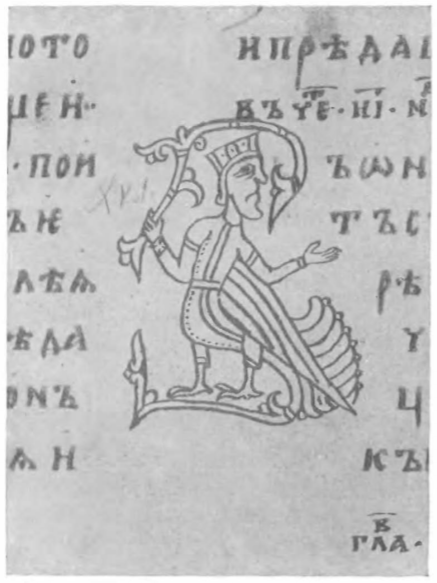

We can establish several points of contact between book decoration and jewelry-making.[32]Stasov, V. Slavjanskij i vostochnyj ornament. St. Petersburg, 1887, plate XLII. The chapter “Painting and Sculpture in Kievan Rus”[33]jeb: An earlier chapter in the same book as this article. mentioned the influence of cloisonné enamel [Rus. перегородчатая эмаль, peregorodchataya emal’] on the miniatures of the Ostromir Gospel: the gold outlines, the bright colors, and the presence of fine details. Enamelwork had a similar impact on the initials (capitals) of this significant book (see images above). The initials in this book are unique in their colors and designs.[34]This manuscript is stored in Leningrad, in the Saltykov-Schedrin State Public Library, inv. no. F II, 1, no. 5. The vertical bases of the letters consist of many small segments of various colors, surrounded (as in cloisonné) by closed golden frames. In a multicolored bright frame, we frequently see plain pinkish masks, similar to a conventional image of the sun. This combination of flesh tones and multicolored outlines is again reminiscent of cloisonné. A particular characteristic of the Ostromir letters are the presence of large dragon heads. This motif was also used in later works, but the heads lose their large size and raised appearance. In the character of the curls and various branches off the columns, the initials from the Ostromir Gospel are most similar to the famous golden diadem from Sakhnovka with its depiction of “the Ascension of Alexander the Great” (see image above).[35]Khanenko, B and V. Drevnosti Pridneprov’ja. Issue V, pp. 54-55.

The later, 11th-century manuscript, the Izbornik of Svyatoslav Yaroslavich from 1073, completely preserves this “enamelwork” style in its miniatures.[36]This manuscript is stored in the State Historical Museum in Moscow, Patriarchal Library, D 31. Of particular interest is that on the parchment, one technical style of enamel was imitated in its miniatures. In many enameled items, the pattern is created using bit by bit using curved partitions, which is much easier to solder to the sheet as a result of its bends. This same step-wise pattern appears also in book decoration (in the Izbornik and in the Yuriev Gospel).

The renowned Mstislav Gospel (c. 1117) imitates the Ostromir Gospel, and ends the line of “enameled” manuscripts, with their many colors and gold borders.[37]Simoni, P. “Mstislavovo Evangelie nachala XII v., T. II. Snimki.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti. No. CXXIII. St. Petersburg, 1904, plate I. The manuscript is stored in the State Historical Museum in Moscow, Patriarchal Library, No. 1203.

The best example of manuscript art from the 12th century is the Gospel of the Yuriev Monastery in Novgorod, written 1120-1128, most likely in Kiev.[38]Atlas risunkov k trudam II Arkheologicheskogo s’ezda. St. Petersburg, 1881, Plates IX-X. The Yuriev Gospel is stored in the State Historical Museum in Moscow, Patriarchal Library, No. 1003. The miniatures and initials from the Yuriev Gospel are distinctly different from those described above, in particular in its colors. All of the contours are written in cinnabar alone, and their graphic nature is similar to the engraved outlines of depictions on 12th century silver items, to which they are also related in style (see images above). The artist who decorated this manuscript with its capital letters was a powerful master. All 65 initials are carried out in a single style, by a single hand. They are all carried out in a single size, but at the same time, each letter is completely original. While preserving the unity of style, the artist continuously invented new forms and new images for each letter; this required a certain amount of fantasy, since the set of letters was very limited: Б, В, and Р. The drawing of these letters pleases the eye with its definition and smoothness of line. The curves are distinguished in their grace and beauty. The author’s rich fantasy brightens up this Christian liturgical book with an entire menagerie. We find here a two-humped camel, a saddled horse, leopards, a snake, bears, a lioness, a cat, a dog, a wolf, and a unicorn. Just as rich is the world of feathered creatures: a pheasant, a crane, a falcon or hawk, a raven in a wolf’s mouth, and various small birds on branches. We also encounter a siren with a maiden’s face and wearing a crown that is similar to the diadems known to us from archaeological finds.

In one capital, we find two female figures in long dresses, who appear to throw flowers upon a grave. A letter Р (“R”) is shown in the form of a nude woman holding a lush flower; the woman is reminiscent of images of priestesses on Iranian silverwork from the 7th-10th centuries. These priestesses were depicted either as nude, or wearing very light clothing; they danced while waving narrow veils, or walked while holding finger cymbals, sacred pheasants, vessels, or flowers with juicy petals. We also see this same kind of flower in the Yuriev Gospel. Here, as in other situations, decorative art reflects medieval Rus’s broad, international relations.

The decoration of the Yuriev Gospel is organically tied to the jeweler’s arts. In one situation, the artist depicted a cloisonné design with the characteristic cells used by 12th century enamelwork. Another letter reproduces the knotwork decoration from bone items, with a typical carved two-strand outline with points in the middle. Even the subject selected here is exactly the same as on that is found in carved bonework – the snake. In several letters, the knotwork reproduces the chainmail design found on woven silver bracelets and torcs. The miniatures in many letters are extremely similar to the chased handles of vessels. They remind us of the outlines of the handles of the vessels in Novgorod’s St. Sophia’s Cathedral sacristy (the ones created by Bratilo and Kosta); the oldest of those vessels and the Yuriev Gospel were created around the same time, in the 1120s. The Yuriev Gospel and these vessels are also quite similar in their depiction of flowers. We can also see much in common with the cast, brass arches from Vschizh: their handling of feathers is completely identical; the rounded, flowerlike tails of the arches’ birds are analogous to the flowers in the initials. Even the monsters surrounded by knotwork are identical to the smallest details in both items. The letters’ depiction of leopards is similar to those on wide silver bracelets and in the Vladimir reliefs, where leopards were also common. The image of a running beast with a flower in its mouth depicted on one letter is also found frequently on kolty and other items of jewelry. We note, by the same token, that the engraved design on a silver bracelet from the 1886 Vladimir hoard was, in its composition, typical of 13th century book illuminations, only carried out in silver. In short, the cinnabar initials from 1120-1128 reveal many points of similarity with items of other forms of artwork from the same century.

Having reviewed these bright examples of urban artistic crafts from the 11th-13th centuries and their techniques, we now turn to an overview of Russian ornament by its individual stages of development.

Ornament

The exact dating of its monuments presents a great difficulty for the study of medieval Russian decorative art. Pagan burial mounds, which only preserved items of the highest quality, disappeared from urban life by the early 11th century, around the same time as the acceptance of Christianity. There are few known Christian burial sites from the 11th-13th centuries; as a result, we lack important data from mass graves from these centuries.

The majority of items of artistic craft have been found in treasure troves. These troves, discovered accidentally during earthworks in several ancient Russian cities, consist primarily of female jewelry hastily thrown into a pot or cauldron and buried in the in times of danger. Sometimes these items were buried with a fastened lock meant to magically protect the hoard by “locking” it away from all except the true owner who possessed the key.

Scholars have tried to tie this burying of valuables in the earth to the numerous princely strifes which fill the pages of our chronicles. But, these strifes began in Rus’ in the 10th century and extended to the 15th, while the items in these troves show a high level of homogeneity and simultaneity. Only an insignificant group of troves can be dated to the 10th-11th centuries; the majority belong to a later time.

If one locates these later finds on a map, we see that they are grouped around the Vladimir-Suzdal’, Kiev, and Galitsko-Volynsk regions. If we also place Batu’s campaigns from 1237-1241 on the same map, we find that there is a great deal of overlap between the two sets. Those places where the Tatars razed cities and took the population prisoner, and where the owners of troves were therefore unable to return to their ashes to dig up their possessions, are where troves remained until their chance discovery. Moreover, where the Tatars did not invade – Smolensk, Polotsk, Novgorod, Pskov – there are no troves.

As such, the majority of troves were buried in the years 1237-1241. Naturally, the majority of items in these troves were created in the 12th-13th centuries. We have at our disposal very few items from the 11th century, and the time period between the antiquities of the pagan period (9th-10th centuries) and the late pre-Mongol period represent an annoying gap. Sometimes the dating of items can be assisted using ethnographic evidence – the character of inscriptions; items sometimes have princes’ symbols, allowing us to narrow down its date (e.g., on seal-rings). Unfortunately, far from all signs on applied art thus facilitate accurate dating.

For the earliest period of applied art in Kievan Rus’, the 9th-10th centuries, we have abundant material from excavations of the burial mounds of the princes and their households from Kiev, Chernigov, Smolensk, Ladoga, Suzdal’, and other old cities.

The preserved fragments of metallic jewelry which survived the flames of the funerary pyres, of course, cannot allow us to fully judge all of the varied forms of art from everyday medieval Russian life. As a result, we need to admit in advance that our analysis of decorative motifs is incomplete.

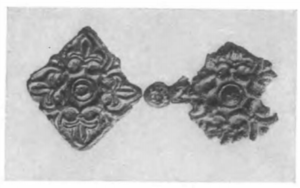

On numerous silver lunnitsy and amulets, we find simple geometric designs; granulation is laid out in diamonds, triangles, or lines (see image above). Depictive motifs, for example birds, are seen very infrequently in this technique. We also find chasing used to imitate granulation; this is also dominated by the same geometric style. We also find this style in the decoration of bone items: “eyes” drawn with a special compass and with a dot in the center, and rows or triangles of these “eyes”.[39]Guschin, op. cit., plates IV and XI. But, a different geometric style is characteristic for military household art in the 9th-10th centuries. In artwork from the stormy years of Oleg and Igor’s campaigns, we find cheerful decorative finishes. As an example, look at belt findings, which were uniform across almost all of the lands of Rus’. Large, diamond-shaped plaques with a slot in the middle for the belt were decorated in the corners with heraldic lilies; the spurs off their stems were intertwined and ended in rings. This ornamental motif was quite long-lasting. We also find it, for example, on silver clasps from the famous Chernigov burial mound in Gul’bische (see image above).[40]Samokvasov, D. Mogil’nye drevnosti serebrjanskoj Chernigovschiny. Moscow, 1917, illus. 58. These diamond-shaped clasps are still used in Ukrainian Hutsul[41]jeb: an ethnic group living in western Ukraine and Romania. ethnic costume today. On one of the aurochs horns (also from Chernigov), amid the woven garlands we find four of the same lilies, or as they were called in Rus’, kriny [sing. крин, krin]. Much later, in the 12th century, we also find these lilies on a fresco at the Savior Church on the Nereditsa, in a cross-shaped pattern on Yaroslav Vladimirovich’s cloak. Local production of plaques and clasps is beyond question, as similar items have not been found in any other locations. Sometimes on belts, flowers and plant forms were replaced with decorative forms of princely signs, a prototype of coats of arms. Yaroslav the Wise’s seal, for example, has been found in the Ladoga region and in Suzdal’; all elements of the seal here acquired an ornamental character of leaves and flowers.

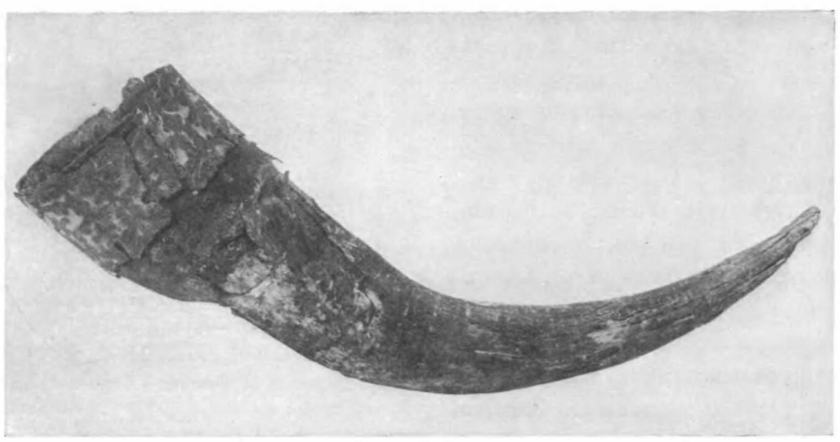

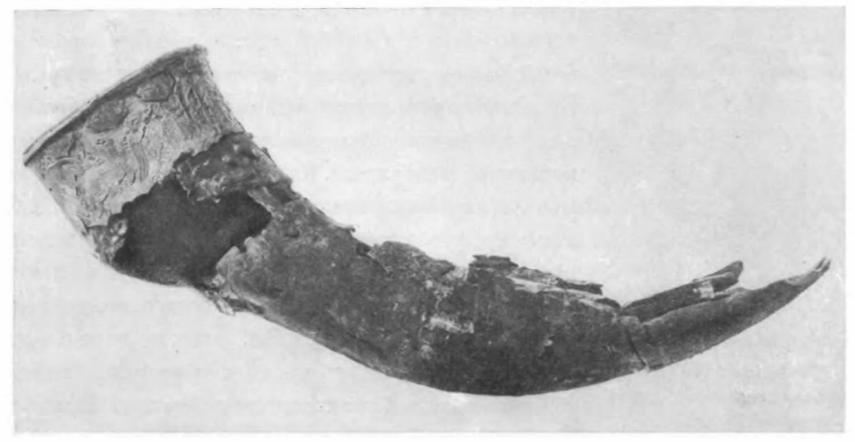

In Chernigov, in an enormous burial mound (the so-called Black Grave), a contemporary of Svyatoslav was buried, a prince of Chernigov whose name is unknown. After a funeral at the top of the primary embankment, crowned with the weapons and armor of the deceased, two enormous aurochs horns bound in silver were placed in the grave.[42]idem., illus. 13-16. Both of these horns, each in their own way, are important for the history of Russian art. On one of them, there are boldly engraved garlands of stylized leaves and bands, recalling designs which were already long known in Eastern art (see image below). This is were we encounter the pattern of four lilies already mentioned above. This ornament became firmly entrenched in the arsenal of Dnieper-region jewelers. In Kiev, near the Golden Gates, a sword was found with a hilt which was covered in silver plate with exactly the same design. Later, this design is also seen in Czechia and Moravia; Czech scholars attribute the appearance of this pattern to the strong influence of Kievan Rus’ on the region.

Vegetative designs were not the only motif in decorative art of the 9th-10th centuries. We also frequently encounter complex braided beasts, snakes, people, animal paws, and human hands. Cast from bronze or silver, always from a wax model and worked with a sharp chisel, these items (famous primarily from Gnezdovo, near Smolensk) associate Russian casting arts with the artwork of the northern European peoples. The sources of this “animal style” cannot be reduced to a borrowing from the Varangians, who were merely a few detachments of mercenaries from Scandinavia. The Varangians did not give the Rus’ their language, their runic writing system, or any other elements of their especially high culture; quite the opposite, they gave up all their national traits in Rus’ and became Russified.

Horses, birds, snakes, and ruling above all of this animal world the figure (or at least the head) of man – this kind of composition was known in the Dnieper glades at least 200 years before the appearance of the Varangians in the region (see the earlier chapter, “Art of the Ancient Slavs”). This style was particularly apparent in carvings on bone. Knotwork designs and bizarrely curved bones of beasts are quite often seen on bone plates from quivers, sword hilts, and cases for folding combs. In all likelihood, this style was also widely used for wood carving; in any case, vestiges are easily traceable to Russian folk wood carving in the 17th-19th centuries. We also find it in brass castings among burial mound antiquities. This style was intrinsic not only in the North, but also in the South. For example, an amulet with two interwoven dragons was found in a Belogorsk burial mound group in the Kursk region. Well-carved bone is also found in burial mounds from the 10th century alongside log huts to the south of Chernigov.

The harmonic coexistence of knotwork-animal ornament and Eastern motifs can be seen on the second aurochs horn from the Black Grave (see images below). The silver cover is framed with typically Eastern plaques with floral designs, worked in niello. The central part of the cover consists of a frieze of beasts, birds, animals, and people. Here we also see a rooster, a wolf, an eagle, and some incomprehensible beasts. Their bodies are intertwined and they are biting one another, and their tails have merged into a single ornamental palmetto. All of the personages in the frieze are entangled in a knotwork of ribbons, uniting these individual links into a single compositional whole. It is possible to find close analogies to just about every figure depicted on the horn amongst Russian burial mound antiquities from the 9th-10th centuries. All of these images, each individually customary to the Russian eye, were skillfully arranged by a Chernigov artisan into a single artistic whole. The chaser built his work according to certain compositional principles: the face of the vessel depicts a a scene of two men hunting a bird (see more below); on either side of this central subject stretch out woven tree branches, inhabited by a host of animals and beast-like spirits. On the rear of the horn, the two rows of beasts come together, and the tails of the last two dragons fuse into a palmetto, serving as a dividing mark for the entire composition. Having by chance survived the flames of the funerary pyre, this aurochs horn serves, as it were, as an artistic epigraph to Russian art of the following age. The embryos of many ornamental motifs on silver, on the parchment of manuscripts, and on the white stone of urban cathedrals can be found here on the cladding of this significant Chernigov horn. This horn stands on the brink between two epochs, between pagan and Christian Rus’. It closed out one epoch, and began another, just as after the Christening of Rus’, old pagan motifs continued to live.

Aurochs horn, clad in silver with depictions of animals and hunt scenes. From the Black Grave burial mound in Chernigov. 10th century. State Historical Museum.

From the 11th century, the time of Yaroslav the Wise’s rule, very few items have survived. It is possible to believe that among the later troves buried during Batu’s invasion, there are individual items created in the 11th century. One reference point we can use is handwritten ornament, the close connection of which, as we saw above, can be seen with other kinds of applied art. The decoration of the Ostromir Gospel (1057) and Svyatoslav Izbornik (1073) clearly imitates enamelwork. This allows us to look in treasure troves for items, buried among expensive gold jewelry, which are similar in style to these manuscripts. We can look, for example, at kolt chains in the form of a stylized tree with three branches. The variegated colors, massive stems, and characteristic curves make this enamel similar to the initials from the manuscripts. Even more similarity with the Ostromir Gospel can be seen in the enamel patterns of the diadem from Sakhnovka. The bizarre curves of the multicolored branches with many offshoots and a complex inner design, as well as the style of the gryphons, are extremely similar to the “enameled” capitals from the manuscript. Both the diadem and the Ostromir Gospel can be assigned to a single stylistic group. This style dates to the second half of the 11th – early 12th centuries.

A somewhat later monument of this direction, the Mstislav Gospel (around 1117) contains many decorative elements in common with kolty and golden ryasny.[43]jeb: The chains used to suspend kolty from a woman’s headgear, typically at shoulder height. Among these is the pattern of leaves with wavy whitework inside. We find this on items from Sakhnovka, where the diadem above was found.[44]Kondakov, Russkie klady. Vol. I; Khanenko, op. cit., plate XXXI, illus. 1096. In all cases, items with this design accompany kolty with sirens, rather than Christian images which were in widespread use by the mid-12th century. Few items have come to us from the late 11th century which can be more or less precisely dated. One of these was a mold for chasing silver kolty. The obverse of the mold is inscribed with the princely mark of Vsevolod Yaroslavich, who died in 1093 (see image above). This instrument of a courtly artisan can be dated to the second half of the 11th century.[45]Rybakov, B. “Znaki sobstvennosti v knjazheskom khozjajstve Kievskoj Rusi.” Sovetskaja arkheologija. 1940 (6), p. 254, illus. 82-85. The image of a beast with a flower in its mouth is carried out without any specific details. There is no knotwork design, just as there is none on other items from the 11th century. Kolty with very similar designs have been found near Chernigov. In the Church of the Tithes, they found the sarcophagus of Prince Rostislav Mstislavich, who died at the same time as Vsevolod (1093). It contained a silver cover for a sword sheath and belt set. On the belt tip, there was a vegetative design with rounded and smooth lines. The sheath had a depiction of a very generalized figure of a bird and the same rounded plant designs. Below, there was a woven ornamental design.[46]Karger, M. “Knjazheskoe pogrebenie XI v. v Desjatinnoj tserkvi.” Kratkie soobschenija IIMK. 1940 (5 (jeb: sic)), illus. 5.[47]jeb: Note, this attrbution contains a typo; the article in question was actually in issue 4.

In the 12th century, knotwork took a predominant position in Russian decorative art. Carved capitals (Chernigov) and knotwork designs on white stone (Vladimir) were common in architectural décor. Knotwork made up from four bands were strikingly identical in carved stone as well as in silver jewelry (for example, a late 12th century bracelet from the 1906 Tver’ hoard, a bracelet from the Rakovskaya manor in Kiev, the arches from Vschizh, and other items). These bands of knotwork surround beasts on kolty and in manuscripts. The wings of birds and beasts transform into a large net of lace, and their legs weave together into bands of knotwork.

The turns of the bands come in two manners. In the center of the work they are rounded, and the joining of several bands creates a figure similar to a circle. On the ends, the bands bend into acute angles. Alongside the knotwork, a smooth pattern of vegetative fronds continues to be seen. These fronds are few in number, but are large and primarily curl into the shape of the Latin letter “S”.

Tied to this more complex form of image and the strengthening of the knotwork motif, artisans abandoned the use of blackened backgrounds and turned around the middle of the 12th century to the use of niello for contours and outlines. The late 12th and early 13th centuries were characterized by the strong influence of filigree patterns made up from curls and spirals on jewelry, illumination, and fresco decoration. On clothing, on the haloes of saints, and on the bodies of beasts, spiral patterns appear more and more frequently, looking similar to the wire curls of filigree. The folds of clothing even follow this general style and twist into spiral curls.

Toward the end of the pre-Mongol period, the use of rounded vegetative patterns with leaves and lilies (kriny) became stronger (as if to counterbalance the fractional patterns of spirals). Flourishing crosses are quite common in this period, framed by these stems and leaves. This style was fully developed in the reliefs of the St. George Cathedral in Yur’ev-Pol’skiy (1234).

The compositional construction of Russian ornament in the 11th-13th centuries was always subordinated to the relatively small space of 1-3 squares. Very rarely, the ornament consisted of long, uniform stripes or ribbons. The earlier Russian artisans always broke up the decorative area into several distinct sections; each of these would then have its own independent pattern. These sections were sometimes clearly delimited by some kind of separating lines; sometimes, the artisan, having placed the design inside a circle, square or triangle, then deleted these geometric borders.

As an example of compositional arrangement of ornament, let us look at the wide silver bracelets frequently found in 13th century Russian troves. These bracelets always consist of two valves joined with a hinge. Each valve is typically divided horizontally into two unequal parts, with the upper part around 2/3 of the height, and the bottom 1/3. In addition, the plane of the valve is broken up by arches into 3-4 sections. The upper layer with the arcades was intended to be filled with birds, fantastic animals, and people. In the lower layer, the artisan placed knotwork and vegetative designs (see image above).[48]Guschin, op. cit., plate VIII, illus. 13. Once closed, the bracelet resembled a miniature tower with an ornamented base and an arcade running above the base all the way around the bracelet. The arches (in the 12th century these were round, in the 13th they were pointed) rest upon patterned columns with decorated capitals; the space between the arches is filled with flowers or with roughly human masks, and the golden birds in the arches complete the resemblance to the architectural décor of this period.

All types of decorative art were tightly interrelated: enamelwork to manuscript initials, initials to niello designs on silver, etc., and all this together came in contact with the bizarre fantasy of the artisans who created white stone carvings.

Items which were created by the hands of Russian goldsmiths were admired not only for their graceful execution, subtlety of technique and beautiful lines of decoration, but also for their bright colors and their combination of various colors. In medieval Russian clothing, the contrast between flamboyantly colored and white linen fabrics was echoed by multicolored jewelry. The silvery surfaces of kolty and bracelets was decorated by the contrasting black color of niello. Golden diadems, kolty and torcs were colored with enamel. The colors of enamel were dominated by dark and light blue tones, with green and flesh-colored tones lying alongside them, surrounded by red outlines. Details of the design were also accented with red enamel. As opposed to the Byzantines, Russian artisans loved to use white enamel, which completed the enameller’s rich palette.

Polychromatic enamel on gold or bronze was not the only means of pleasing the eye with an abundance and diversity of color combinations. We also constantly encounter colored gems and pearls in jewelry. Seed pearls framed golden kolty, and pearled designs bordered rich, silken clothing, continuing that noble combination of gold and white which was also seen in gilt silver items, and on white stone topped with gold filigree heads. On the golden jewelry from kokoshniki (the Kamenobrodsky trove), we see fine golden shells with pearls. It has now been proven that all of these pearls, which were widely used across Kievan Rus’, were of local, Russian production.[49]The issue of the history of Russian pearls and their role in decorative art was clarified by the dedicated research of L.I. Jakunina (PhD thesis defended in 1945 at Moscow State University. Manuscript). Along with pearls, precious stones and colored glass were also widely used. Glass bracelets with light blue, green, and black colors interwoven with smooth or relief goldwork were a favorite item of jewelry for urban women. In Kiev, they even wore glass seal rings. The color combinations in beads were exquisite. Alongside red carnelian and crystal, they wore beads made from paste with multicolored mosaic patterns.

On items of gold, artisans placed gems inside thin bezels, framed with pearls. Light-violet amethysts, dark blue sapphires, jasper, chalcedony, white sapphires, red garnets, and green emeralds were strewn over kokoshniki, kolty, and torcs, rivaling the colors of their enamel. Sometimes, the artisan would achieve an amazing color effect: the stone was placed not in a solid frame, but in an openwork one, raised above the surface of the golden plate on miniature golden arches (Staraya Ryazan’). As a result, the stone appeared to be suspended over the gold, and rays of light creeping through the archways under the stone and reflecting from the mirrored surface would illuminate a transparent gem from within.[50]Kondakov, Russkie klady, p. 87.

Many gemstones had various symbolic meanings in medieval Rus’. Especially revered were emeralds, or as they were called in medieval Russian, izmaragd. It was thought to be a stone of wisdom. Collections of sayings were called Izmaragdy, and sometimes princely daughters were named at birth after a stone. For example, the daughter of Rostislav Ryurikovich was given the Christian name Efrosin’ja, but her worldly name was Izmaragd, “as a precious stone might be called.”[51]Hypatian Chronicle, under year 6707 (1199). The color spectrum of medieval Russian artisans was bright and rich, complemented various technical methods, and played an important role in the formation of ornamental motifs.

The Subjects of Applied Art

Images on medieval Russian jewelry open before us the bright and colorful world of those artistic images and ideas which were lived by the artisans who created these significant works of decorative art.

In literature, in the white stone relief carvings of urban cathedrals, in the diadems of the queens, and in the patterned fabrics of heavy cloaks — everywhere, we see whimsical fantasy fueled by folk stories and pagan myth. Centaurs, leopards, sirens with young girls’ faces, basilisks, phoenixes, the holy “Tree of Life,” doves, eagles, gryphons — all of these were depicted on everyday items of the XI-XIII centuries on equal footing with the images of Sts. Boris and Gleb. The Christian becomes interwoven with the Pagan. As in the Lay of Igor’s Campaign where the Blessed Virgin and Deva Obida[52]jeb: An old Slavic goddess, the Black Swan Maiden, a harbinger of disaster. are mentioned side by side, so too in decorative art, the stern Deësis row and illustrations of the legend about the ascension of Alexander the Great to heaven are seen on one and the same item.

An overview of subjects should start with the important aurochs horn from the Black Mound in Chernigov (see image above). Among the wolves, birds and fantastic beasts artfully worked by the mid-10th century artisan, there is a main subject which stood in the center of the artist’s attention: two hunters with bows shooting at a bird. Examining the figures of these archers, we note the following details: in front is a woman holding a quiver and bow, with a long ponytail and without any sort of headgear. She is dressed in a yubka with a checkered pattern (a poneva?) and a shirt with decorated sleeves. Behind her is a bearded man with long hair, wearing a kaftan or chainmail (?), holding a bow. It appears he has just fired an arrow. Both figures are striving toward the bird, but arrows have fallen not only near the bird, but even behind the man. One arrow flies aloft, another is broken in half, and a third points directly to the back of the man’s head.

We obviously have before us some kind of fabulous story – bewitched arrows which turn back against the archer, and the entire composition is reminiscent of a story: a young maiden, a man with a bow, and a predatory bird (eagle?). However, it is not among stories, but rather among the Russian byliny, specifically those of the Chernigov cycle, where we find a clue to this scene. The bylina about Ivan Godinovich tells of how a young Kievan bogatyr’ set off toward Chernigov to find his bride, Mar’ya Dmitrievna. On the way, Ivan’s cohort scattered throughout the woods, following animal tracks. In Chernigov, it is revealed that Mar’ya is betrothed to Tsar’ Kaschey the Immortal, but Ivan Godinovich takes her away anyway. On the road, Kaschej falls upon them and, having cunningly defeated Ivan, ties him to an oak tree. All of a sudden, a bird arrives, the “black lie,” and in a human voice foretells a bad fate for Kaschej. From this moment forward, the Chernigov bylina and the stamped image on the Chernigov horn are completely identical. Kaschej asks Mar’ya to bring his bow and arrows (on the aurochs horn, the maiden holds a bow and quiver; the man has no quiver), and he shoots at the prophetic bird. Ivan bewitches the arrows, and they fly into Kaschej’s head. On the stamped image, one of the three arrows is directed toward the head of the man, Kaschej. The presence of this bylina subject on this ritual vessel from the 10th century is of great interest, and definitively belies the fabrications of several German scholars about the supposedly Norman origin of this aurochs horn.

In the given example, the subject was denoted clearly and precisely. In other situations, it’s not always possible to immediately guess the idea presented, as it is hidden or extremely stylized, or symbolic meaning which may have been immediately understood by contemporaries, but which are mysterious to us.

In medieval applied art, magical elements prevailed over the purely aesthetic. We can judge this by the pagan gryphons, holy trees, birds which bring happiness, amulets with symbols of the sun or the moon, and other benevolent symbols which in 12th century urban art become replaced with images of the new gods – the Christian saints. On monista and kolty, gryphons were replaced by Sts. Boris and Gleb, Peter and Paul. This means that the previous images also had sacred, protective meaning, or such an exchange would not have been possible.