Today’s post is a translation of an article about the important trade route which passed through Volga Bulgaria between Europe to the Northeast and the Arab lands to the South. In particular, during the periods of the Crusades, when trade routes through the Mediterranean were cut off, this more roundabout route through Eastern Europe became an important source of silver for Western and Northern Europeans in the 9th and 10th centuries. The article is an interesting overview of international trade relations along the Great Volga Route during the Viking and Rus’ periods until the mid-13th century, when Volga Bulgaria was defeated by the Mongol Invasion.

Trade Relations Between Volga Bulgaria and Northern and Western Europe in the Pre-Mongol Period (9th-early 13th cent.)

A translation of Валеев, Р.М. «Торговля Волжской Булгарии с Северной и Западной Европой в Домонгольский Период (IX – начало XIII века).» Вестник НГУ. Серия: История, филология. 2011 (3). с. 175-182. / Valeev, R.M. “Torgovlja Volzhskoj Bulgarii s Severnoj i Zapadnoj Evropoj v Domongol’skij Period (IX – nachalo XIII veka).” Vestnik NGU. Serija: Istorija, filologija. 2011 (3). pp 175-182.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/torgovlya-volzhskoy-bulgarii-s-severnoy-i-zapadnoy-evropoy-v-domongolskiy-period-ix-nachalo-xiii-veka]

[Note that the original article had no illustrations. Where images are seen below, they are my additions.]

Abstract

Having inherited the role of trade mediator from the Khazar Khaganate in the 10th century, Volga Bulgaria enjoyed a monopoly over trade between East and West, Europe and Asia. Trade relations with Northern and Western Europe were most important among these, as is attested by imported items from a number of archeological finds: European swords, Eastern jewelry, Kufic, Bulgarian and Western European coins, metallic utensils, and other products discovered in Western and Northern Europe. The demand in Europe for Eastern silver is shown by the large volume of trade in Kufic and other coins.

One of the most important directions of trade relations in Volga Bulgaria of the 9th-early 11th centuries was to the West and Northwest. European governments’ interest in trade with Eastern lands stimulated the development of trade routes. An important role in the organization of trade was played by cities located on river highways and other convenient locations at the intersections of overland routes and river portages, where there was convenient contact between city-dwellers and the surrounding rural villagers. A.N. Kirpichnikov has listed the trade cities which had direct or indirect relations with the Great Volga Trade Route in the 8th-9th centuries and later: Dorestad in Frisia, York in Britannia, Ribe and Hedeby in Denmark, Nidaros and Kaupang in Norway, Åhus and Birka in Sweden, Oldenburg, Mecklenburg, Ralswiek and Arkona on the island of Rügen, Menzlin, Shecin, Wolin, Kolbsheg, and Truso in Gotland, Saltvik on the Åland Islands, Grobiņa in Latvia, Ladoga, the Rjurik settlement (now Novgorod), Timerovo and Mikhajlovskoe (later called Jaroslavl’), the Sarskoe settlement (later Rostov), Suzdal’, Kleschin (later Pereslavl’ Zalesskij), Murom on the Oka River, as well as settlements and cities in the Central Volga region – Izmeri, Simenovo, Bolghar, Biljar, Suvar, and Kazan’. They were pivotal for determining the state of international market relations. An interesting description description was provided by a German missionary who was in Sweden in 829-830 and 852. In “The Life of Saint Ansgar,” he writes that in Birka “there were many wealthy merchants, an abundance of every kind of good thing, and many valuable objects.”[1]Iz rannej istorii shvedskogo naroda i gosudarstva. Moscow, 1999, p. 40. And through these cities, a major trade route was laid.[2]Kirpichnikov, A.N. “Velikij Volzhskij put’, ego istoricheskoe i mezhdunarodnoe znachenie.” Velikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 13-14.

In the 8th and 9th centuries, European trade with the Central Volga region over Russian lands were founded by the Scandinavians, or, as Eastern sources call them, the Rus’. M.I. Artamonov has noted that this name could refer to Normano-Slavic squads of fighters or merchants only insofar that they formed in the Rus’ lands and traveled from thence.[3]Artamonov, M.I. Istorija khazar. Moscow, 1962, p. 383. A.N. Kirpichnikov likewise emphasizes that they were defined as a specific group of traders, and therefore could include peoples of various origins among its number: Scandinavians, Slavs, and quite likely, Finns. Generally speaking, the term “Rus'” is not so much an ethnic concept, as a geosocial one.[4]Kirpichnikov, 2001, p. 19.

Considering this, it is important to highlight questions tied to the characteristic types of goods passing through these trade routes; this provides input into the chronological and ethnocultural interpretation of a number of finds from archeological sites.

Sufficiently characteristic from this time period is the image of the warrior-merchant, who has traveled many lands and who can handle a sword or a set of scales equally well. Indeed, swords which were mass-produced in foundries between modern-day Mainz and Bonn have also been found in our region.

It has long been thought that the Balymer burial mounds, found in the late 19th century in the Spasskij region of the Kazan’ province (today, the Spasskij region of Tatarstan) were left behind by Rus’, either Slavs or Vikings. Here, there are clear signs of a burial with grave goods, including decorations from a horse’s bridle, as well as items of daily life: an armchair, a tinder horn, et.al. Importantly, the grave contained an iron sword, broken in two. It is interesting that in the 1980s, in burial mounds from the Mordovian tribe from the 10th-11th century Oka region, swords were found which were likewise broken in two. Similarly broken swords have also been found in Scandinavia.[5]Kirpichnikov, A., Tolin-Bergman, L. Janson, I. “Novye kompleksnye issledovanija mechej epokhi vikingov iz sovranija Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja.” Slavjane, finno-ugry, skandinavy, volzhskie bulgary. St. Petersburg, 1999, p. 121.

Supporters of the Scandinavian version of the origin of these objects provide a different argument. One of the items found in the Bulgarian settlement was a Scandinavian, female fibular clasp. Special hair pins created in a Scandinavian style wee also found in the Uljanovsk region and in Udmurtija. These personal items were worn, as a rule, by women, and as such could not have been acquired by local inhabitants of Volga Bulgaria. This would suggest that the Scandinavians brought their wives with them. But, here too there are nuances. Even though the Bulgarians typically did not wear such jewelry, the northern Finns used these with a relish, as they also used European swords. We know that Finnish tribes from the northern regions (the Lake Ladoga region and Karelia) were frequent guests of the Volga Bulgars, as is attested by numerous archaeological finds.

European swords, or fragments thereof, have also been found in other areas of the Central Volga and Kama regions: a fragment of a 10th-century sword with zoomorphic details in Biljar, an S-type sword from the late 10th-early 11th century with a silver-inlaid hilt from Salman in the Spasskij region of the Kazan’ province, swords richly decorated with silver in the Ringreike style from the 11th century found on the outskirts of Elabuga.[6]Jansson, I. “‘Oriental Import’ into Scandinavia in the 8th-12th Centries and the Role of Volga Bulgaria.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XVI vv. Kazan, 1999, p. 120 189-189 examples of this type of blade have been found in European countries, of which 16-17 were found in Sweden; meanwhile, 12 whole swords and 8 fragments have found in Volga Bulgaria.[7]Kirpichnikov, et.al., 1999, pp. 108-109; Izmajlov, I.L. Vooruzhenie i voennoe delo naselenija Volzhskoj Bulgarii X-nach. XIII v. Kazan’, 1999a, p. 34. This similarity in numbers speaks convincingly enough of the widespread penetration of such items into the Central Volga region.

Several swords are stored in the collections of the National Museum of the Republic of Tatarstan.[8]Valeev, R.M. Torgovlja i torgovye puti Srednego Povolzh’ja i Priural’ja v epokhu srednevekov’ja (IX-nachalo XV vv.). Kazan’, 2007, p. 118, Illus. 153-155. Several more swords, discovered in the Kazan’ province, are now in the collections of the State Historical Museum (Moscow) and the Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg). These are massive objects, nearly 1 meter in length, with wide, double-edged blades, upon which are preserved a hallmark of the workshop where they were produced in the form of the name “ULFBERHT,” most likely the name of the workshop’s founder. This workshop, located in the Rhine region of Germany, released hundreds of swords in the 9th-early 10th century which then spread out into many European countries. This was the largest arms factory of the Middle Ages, which produced what were generally recognized as the best weapons. The application of brass created the impression that the sword was decorated with gold, while the inclusion of silver in the finish gave the richly decorated surface an outward appearance that was iridescent with various colors.[9]Kirpichnikov, et.al., 1999, pp. 109-110.

The “ULFBERHT” trademark was created using iron or damascened wire laid into stamped grooves in the upper section of the blade. The grooves themselves were created along the contours of the inscription’s letters. The sword’s guard was decorated with sinuous designs with silver incrustations. The pommel was decorated with filigree. The swords from the collection of the National Museum of the Republic of Tatarstan date no earlier than the 10th century.

The sword was an attribute of a warrior-hero and intrepid individual. In Europe, since the times of the Merovingians, the sword was the primary weapon of a warrior on horseback and was a must-have for every free citizen. It was a kind of sign of the time. A warrior armed with a sword, be he a European knight, Scandinavian Viking, or Eastern merchant, became simultaneously an ambassador, traveler, merchant and brigand. The sword served as a kind of key for the moral and ethical beliefs of the time. Since the time of Alexander the Great, the phrase “cutting the Gordian knot” has been used. The Icelandic sagas contain the following phrase: “to dissect one’s vows with a sword.” Swords were one’s most prized possession, and were cherished and cared for.

Export and sale of these swords was prohibited, especially with potential enemies. But, despite these bans, the contraband trade in blades and weapons was extremely wide spread. Swords were individual and extremely expensive products. In the 10th century Baltic region, for example, an average-quality sword cost 0.5-0.75 silver marks (117-175.5 grams, or 39-58.5 dirhams). By comparison, 1 silver mark (about 234g) could buy 1 slave, 2 cows or 4 spears. By weight, according to calculations by the German scholar Joachim Herrman, in the 11th century a sword cost 125g of silver, a horse cost 50g, spurs cost 20g, a bridle cost 10g, a bridle buckle 5g, a knife cost 3g (1 dirham), and 1 glass bead cost 3g. [10]Kherrman, I. “Slavjane i normanny v rannej istorii Baltijskogo regiona.” Slavjane i skandinavy. Moscow, 1986, p. 81.

The sagas also describe the fabulously expensive price of swords – in half-marks of gold (117g of gold).[11]Lebedev, G.S. “Etjud o mechakh vikingov.” Arkheologicheskaja tipologija. Leningrad, 1991, p. 289. The relative cheapness of these items [compared to those listed above], in our opinion, only appears such because the price of consumer goods at the time was significantly different. In Rus’ at the time, 1 horse cost 150g of silver, 1 cow was 80g, 1 ox was 50g, a sheep was 15g, and 1 pig was 10g. The purchasing power of silver was particularly high with relation to household goods. In Prague around 965, for example, 1 dirham could buy 25 chickens, or 75 daily rations of wheat for a man, or 100 daily rations of barley for a horse. A 12th-century household member’s allowance was 200 silver grivny a year, equal to about 50 silver marks (about 11.7kg). In Scandinavia, the annual income for a professional warrior averaged 100 marks (approximately 23.4kg).[12]Herrman, 1986, p. 81.

Via the Central Volga and Khorezm, these swords were also sold in the lands of the East, as directly mentioned in the 9th century writings of Ibn Hordadbeh[13]Khvol’son, D.A. Izvestija o khazarakh, burtasakh, bolgarakh, mad’jarakh, slavjanakh i russakh Abu Ali Akhmeda Ben-Omar ibn Dasta. St. Petersburg, 1870, p. 158. and in the 980s by al-Muqaddasi.[14]Garkavi, A.Ja. Skazanija musul’manskikh pisatelej o slavjanakh i russkikh (s pol. VII do kontsa X v. po R.X.). St. Petersburg, 1870, p. 282. Although Bolghar was typically a final stop for Scandinavian merchants, several of them sometimes reached the Caspian Sea, Central Asia, and even Baghdad.[15]Polubojarinova, M.D. “Torgovlja Bolgara.” Gorod Bolgar. Kul’tura, iskusstvo, torgovlja. Moscow, 2008, p. 93. Via Volga Bulgarian merchants, a 12th-early 13th century sword with a Latin inscription and a bronze sculpture of a dragonslayer cast in Lorraine in the early 13th century even reached as far as western Siberia.[16]Kyzlasov, L.R. “Torgovye puti i svjazi drevnekhakasskogo gosudarstva s Zapadnoj Sibir’ju i Vostochnoj Evropoj.” Proshloe Srednej Azii. Dushanbe, 1987, p. 83; Polubojarinova, 2008, p. 34.

There was an interesting find in Bolghar of an equal-arm cast brooch of Scandinavian import from the second half of the 10th century. Its ends were in the shape of animal heads, and the surface was decorated in knotwork with fine grooves. Around 20 examples of such items imported from Scandinavia have been found in Rus’ sites.[17]Poljakova, G.F. “Izdelija iz tsvetnykh i dragotsennykh metallov.” Gorod Bolgar. Remeslo metallurgov, kuznetsov, litejschikov. Kazan’, 1996, pp. 154-168.[18]jeb: See illustration 3, left (labeled “24”). Although I.L. Izmajlov considered these fibulae to be part of the sacralized complex of personal belongings and amulets tied to the presence of Scandianvians in the Central Volga and believed that they would not have been trade items,[19]Izmajlov, I.L., “‘Rusy’ v Srednem Povolzh’e (etapy bulgaro-skandinavskikh etnosotsial’nykh kontaktov i ikh vlijanie na stanovlenie gorodov i gosudarstv.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999b, p. 97., they were traded, and at the same time serve as evidence of close trade relations between Volga Bulgaria and Northern Europe. In addition, on a fibula found in the Bulgarian settlement of Krasnaja Reka II in the Staromajnskom settlement of the Ul’janov region, and previously though to be of Scandinavian origin, signs of runic Scandinavian writing indicating the owner’s name were found after chemical cleaning of the surface.[20]Semykin, Ju.A. “Nakhodka kol’tsevoj skandinavskoj fibuly iz Ul’janovskogo Povolzh’ja.” Velikij Volzhskij put’: istorija, formirovanija i razvitija. Kazan’, 2002, p. 248-250. Likewise, a horseshoe-shaped fibula of 11th-12th century Baltic origin was found in the Volga region.[21]Poljakova, 1996.[22]jeb: See illustration 3, right (labeled “25”).

I.V. Dubov admits there are various ways that brooches could have reached the lands of Eastern Europe, either directly with Scandinavians, or as a result of trade relations.[23]Dubov, I.V. Velikij Volzhskij put’. Leningrad, 1989, p. 119. Ju.A. Semykin, a scholar of the Kraskorechenskij settlement, considered the fibula brooch to be an accessory of a Scandinavian merchant. Early 10th century Varangians not only were engaged in wholesale trade in the Central Volga, but also independently traded small lots of their goods in remote areas.[24]Semykin, 2002, pp. 251-252. In our view, archeological materials are insufficient to make such a bold deduction, despite the appeal of such an opinion.

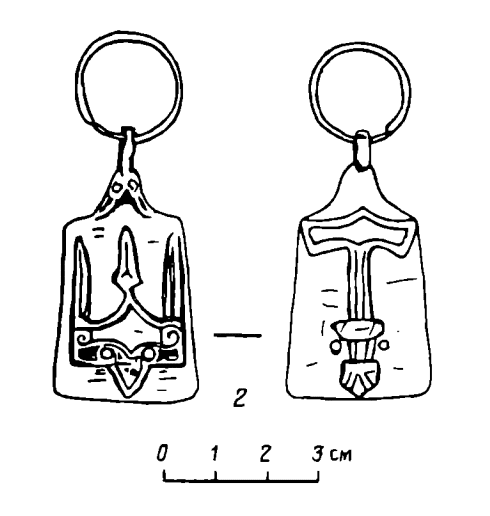

It is interesting that the famous Elmed hoard found near Bilyar, consisting of 150 dirhams and to-date the only hoard to contain 8th-9th century coins, included 2 coins with graffiti, one of which is identical to the Scandinavian rune for “S”.[25]Dubov, 1989, p. 187, Illustration 57, item 6; Mel’nikova, E.A. “Baltijsko-Volzhskij put’ v rannej istorii Vostochnoj Evropy.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, p. 84. 4 hoards of Kufic coins from 802-843 have been found in the Vjatka and Kama region (the former Vjatka province) and on the border of the Udmurtia and Kirov regions. Many scholars believe that in the 9th century, the upper reaches of the Vjatka and Kama were a special region. It was located to one side of the major river trade routes, but nevertheless attracted merchants, especially Scandinavians, from the Baltic-Volga trade route. It is possible that the borders of this region lay near modern-day Perm’. There, an amulet bearing the symbols of the Rjurikovichi (a trident on one side, and a Thor’s hammer in the form of a sword grip on the other) was found in a male gravesite from the second half of the 10th-early 11th century; it appears that it belonged to a royal retainer of Scandinavian descent.[26]Krylasova, N.V. “Podveska so znakom Rjurikovichej iz Rozhdestvenskogo mogil’nika.” Rossijskaja arkheologia. 1995 (2), pp. 192-197; Mel’nikova, 1999, pp. 84-85; Izmajlov, 2001, p. 73.[27]jeb: See illustration 4.

A stabilization of relations between the Bulgars and the Rus’ occurred after 913, when the Bulgars defeated the Rus’ on the Volga. One segment of the Rus’ continued trading and paid duties to Volga Bulgaria, but another became part of the social structure of Bulgar society. A number of warriors entered service to Bulgar nobility. When their service ended, they returned to Scandinavia or Rus’, taking Bulgar items along with them (belt decorations, horse tack, etc.), as well as knowledge of the peoples of the Volga region (“Bulgarland”, “B’jarmland”).[28]Izmajlov, I.L. “Baltijsko-Volzhskij put’ v sisteme torgovykh mgistralej i ego rol’ v rannesrednevekovoj istorii Vostochnoj Evropy.” Vilikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, p. 76.

The saga about Norse King Olav Haraldsson (1014-1028) and his flight in 1029 to Rus’ relates that: “Prince Jaroslav and Princess Ingegerd asked King Olav to stay with them and to seize the land which is known as Bulgaria, which was part of Garðaríki[29]jeb: The Old Norse term for Rus’. and which was filled with many heathen peoples.”[30]Dzhakson, T.N. “O jazycheskoj Bulgarii Snorri Sturlusona.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, p. 31. In the minds of Scandinavians who had traveled from the Baltic to the Central Volga, Garðaríki and Volga Bulgaria were inextricably linked. This fact (Prince Jaroslav specifically suggests Bulgaria to Olav), as interpreted by Snorri Sturluson who was trying to exalt the king and patron saint of Norway, reflects the location of Volga Bulgaria in the “mental map” of medieval Scandinavians and the importance which was given to the trade relations along the Great Volga Route.[31]idem., p. 34.

The visit by Scandinavian merchants to the Central Volga, according to Ibn Fadlan’s account from 922,[32]Kovalevskij, A.P. Kniga Akhmeda ibn Fadlana o ego puteshestvii na Volgu v 921-922 gg. Khar’kov, 1956, pp. 141-146. was tied to their interest in Eastern trade goods, especially the Kufic silver coins brought there by Islamic merchants.

K. Heller, V. Vogel, D. Elmers, H. Arbman, and other western scholars note that in Sweden and in Scandinavia as a whole at the turn of the 8th-9th centuries, there appeared a new type of professional merchant, the “farmaðr”. He was not engaged in traditional trading, but rather only in long-distance trade, which became possible due to the transport links between Western Europe, Scandinavia and the East, and the appearance of a new type of trade outlet in the Baltic Sea region, including Birka. Over the course of almost 200 years, trade relations between the East and West were carried out in that city. As a trade transit point, Birka connected two ends of the long-distance trade route: one, starting in the Rhine region and passing through Hedeby to the Baltic Sea, and the other, the open route along the Volga river system from Sweden to the East. For this reason, in the 9th-10th centuries, Scandinavian long-distance and transit trade functioned thanks the profit from this commercial convergence of East and West. One precondition for this was the economic resurgence of Western Europe and the far-away development of the Arabian East, as well as the fact that, due to Arabian expansion, old trade routes through the Eastern Mediterranean to the East were a great deal more difficult.[33]Kheller, K. “Rannie puti iz Skandinavii na Volgu. Skandinavskaja ekspansija v vostochno-evropejskoe prostranstvo s nachala VIII veka.” Velikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 101-102.

Eastern, Northern, and in particular Western Europe were in need of eastern silver. In Northern Europe, demand for Kufic dirhams was enormous, as there were no local sources of silver. Until the German silver mines were opened and silver coins began to reach the Baltic (second half of the 10th century), the Islamic world, including Volga Bulgaria, held a de facto monopoly on silver.[34]Nunan, T. “Torgovlja Volzhskoj Bulgarii s samanidskoj Srednej Aziej v X v.” Arkheologija, istorija, numizmatika Vostochnoj Evropy. St. Petersburg, 2004, p. 258. Beginning in the mid-8th century, great numbers of silver coins reached these regions via the Volga and Don River regions. This establishes the beginning of the silver trade even earlier than previously thought. In the beginning, the Khazars and Lower Volga region played a defining role as a river stop in the monetary trade between East and West, but by the second half of the 9th century and in particular in the 10th century, this role was held by the Bulgars and the Central Volga region. The role of Volga Bulgaria in the supply of Eastern silver into Northern and Western Europe is attested by the use of Samanid coins from the late 9th-10th centuries, of imitation Samanid dirhams minted in large part by the Bulgarians, and of Bulgarian jarmak coins from the 10th century.

As one of the most important precious metals, silver held great meaning for the Baltic and Western European economies. A comparison of prices for the most popular and highest quality goods gives us a good picture of this. In the Northern Scandinavian region, a slave cost 200-300g in silver. In the contract which Prince Igor’ of Kiev negotiated in 944 with the Byzantine emperor, the price of a young slave was set at 10 zlatniks, or about 426g of silver. An elderly or child slave cost a half of this amount. A slave cost more than 2 bolts of silk.[35]Herrman, 1986, p. 80.

Of the approximately 60,000 Arabian coins which have been found in Sweden, about 50,000 date to the 10th-11th centuries. Similar proportions are true as well for the regions around the southern Baltic coast. One of the earliest and largest hoards in Northern Europe was found in 1973 from a settlement of the early-city type near Ralsvik on the island of Rügen. It consisted of over 2200 coins (primarily Arabian), and a fragment of a bracelet from Perm’ of the so-called “Glazov type”.[36]Herrman, 1986, pp. 80, 82, Illustration 33. Across over 1500 troves in the Baltic region, about 150,000 Arabian coins have been found, clearly demonstrating the scale of trade in the 9th-10th centuries.[37]idem., pp. 77, 82.

Numismatic evidence from the 8th-11th centuries shows a definite period of changes in the flow of Kufic dirhams to Northern and Western Europe and the role the Khazars and Bulgars played in the intermediary trade of silver. In the 770s, hoards of Arabic dirhams began to appear in the Caucasus, and by the 780s they had already reached Ladoga and Gotland. It follows, then, that by the last quarter of the 8th century, the Vikings or Rus’ had established trade relations with the Islamic region via Khazaria. This period, until the end of the 9th century, is called the “Khazar phase.”[38]Nunan, 2004, p. 258. According to recent information from A.N. Kirpichnikov, a dirham was found in the Ladoga region dated 699-700, located in a layer from the earliest existence of the city around 750-760.[39]Kirpichnikov, A.N. “O nachal’nom etape mezhdunarodnoj torgovli v Vostochnoj Evrope v period rannego crednevekov’ja (po monetnym nakhodkam v Staroj Ladoge).” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Crednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, p. 112.

In the late 9th-early 10th century, significant changes occurred. A new caravan route from Samanid Central Asia via Volga Bulgaria replaced the traditional routes through Khazaria. This is clearly shown by the numismatic evidence. While Eastern European and Baltic troves from 875-899 are predominantly made up of Abbasid dirhams minted in the Middle East and imported via Khazaria,[40]Nunan, 2004, p. 260, plate 1. by 910 older Abbasid dirhams almost completely vanish from troves. Troves from 900-910 primarily consist of new Samanid dirhams. It follows that starting in 900, the majority of trade flowed through Volga Bulgaria.[41]ibid., pp. 260-261, plate 2.

Likewise, Samanid dirhams first appeared in the Baltic region in the early 10th century. Their quantity increased steadily, and by 940 represented over 90% of the total flow. Older Abbasid dirhams remained in circulation a bit longer in Eastern Europe, indicating that it took a bit longer for the Samanid coins to reach those lands.[42]Nunan, 2004, p. 261, plate 3. An important role in this was played by the merchants of Khorezm. In the late 9th century, Khorezm entered the Samanid empire, and its merchants convinced their rulers to mint more dirhams for export. They developed the plan for their trade and the method of transportation by caravan over the steppes to Volga Bulgaria, where they sold the dirhams to the Rus’ and other merchants.[43]ibid., p. 266.

Out of nearly 56,600 coins found in 10th-early 11th century troves in Sweden, nearly 41,000 were Samanid dirhams. The lower numbers in the number of Samanid dirhams in Eastern Europe was not as noticeable in Sweden until the early 11th century. The number of dirhams in Eastern Europe was twice as great as in Sweden, but the quantity of Samanid dirhams in both regions was nearly identical, around 78.4% and 80% respectively. The flow of Samanid dirhams from Volga Bulgaria to the South-East Baltic, Poland, Germany and Denmark shows the same tendency. In South-East Baltic hoards from 900-950 there were 1605 dirhams while in hoards from 960-990 there were 1683; in Poland, these numbers are 5718 and 13,275; in Germany, 2926 and 2100; in Denmark, 3465 and 304.[44]idem., pp. 292-294, plates 4-6.

According to calculations by the American scholar T. Nunan, in troves from Eastern, Northern and Western Europe, some 319,000 dirhams have been found. Alongside counterfeit and ambiguous coins, a bit more than 248,500 dirhams were imported from Central Asia during the Samanid period, and over 70,000 were imported from Volga Bulgaria. In all, taking into account a coefficient of loss, over the course of the 10th century, he estimates some 125 million Samanid dirhams, or 375,000 kg of silver, were imported from Central Asia, averaging 3750 kg or 125,000 dirhams a year.[45]idem., pp. 295-296. These numbers show the scale of the trade in Kufic silver which flowed through the markets of Volga Bulgaria.

Another important piece of evidence of the volume of trade between the Central Volga and Scandinavia are finds of counterfeit Kufic coins and coins printed in Bolghar. The Swedish numismatist G. Rispling released in 1985, 1985 and 1999 detailed studies of the metallic compositions of Kufic dirhams found in Scandinavian archeological sites and concluded that in the 9th century, about 5% of coins were counterfeit. Of these, one group, dated to the second quarter of the 9th century, originated in Khazaria. By the 10th century, 10% of Arabian coins were counterfeit, produced with a certain precision in Volga Bulgaria.[46]Jansson, 1999, p. 117.

Coins printed in Bolghar have been found in 8 hoards in Estonia, 10 in Poland, 3 in Finland, 2 in Denmark, and in 1 hoard in Norway. The largest quantity of Bulgarian dirhams has been found in Sweden – in 39 hoards, of which 33 were on the island of Gotland.[47]Kropotkin, V.V. “Bulgarskie monety X v. na territorii Drevnej Rusi i Pribaltiki.” Volzhskaja Bulgarija i Rus’. Kazan’, 1986, pp. 38-57. It is remarkable that 10th century Bulgarian coins were in circulation alongside Kufic dirhams from the 10th and early 11th centuries, and in the second half of the 11th century into the 12th century they circulated alongside Western European and Byzantine coins. In Lund (Sweden), a hoard of coins from 958-959 was discovered, consisting of 235 Kufic and 22 Western European coins, as well as 9 Bulgarian coins which mention Mikail ibn Jafar, Barman, Abdallah ibn Tagin, and Talib ibn Akhmed (the hoard was buried in 965). In Botelse [?], Gotland, a hoard from 948-949 was found containing 220 whole and 2046 fragments of Kufic and Western European coins and 30 Bulgarian dirhams mentioning Mikail ibn Jafar and Abdallah ibn Mikail. In Effinds (also on Gotland), a hoard of Kufic coins (1452 examples) and other items included 25 Bulgarian coins mentioning Mikhail ibn Jafar, Talib ibn Ahmed (949-950), and Abdallah ibn Mikail (957-958). In a hoard from near Kohtla-Järve (Estonia), 777 coins were found, including one cast in the name of Mumin ibn Ahmed (975-976).[48]idem., pp. 49-54. This hoard, buried in 1130, contained a majority of Western European coins. The coexistence of Kufic and Bulgarian dirhams and monetary plate metal attests to the fact that they were all in circulation at the same period in the Baltic region, that is, that Bulgarian coins were in use in the 12th century.

The flow of trade in the other direction is shown by 11th-century Western European denarii from Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Germany, and England, as well as Byzantine coins, which circulated in Volga Bulgaria during the so-called “moneyless period.” Until recently, no Eastern European coins had been found in the Central Volga. Only very recently, in 10-11th century digs of Bulgarian settlements in I Semjonovskoe, I Izmerskoe and Kirpichno-Ostrov villages led by A.S. Beljakov were denarii from Denmark (1047-1075), from Namur[49]jeb: A province in modern-day Belgium. under Count Albert II (1037-1060), copper counterfeit denarii from Groningen, and Deventer denarii from the reign of Groningen’s Bishop Bernold (1027-1054)[50]jeb: See illustration 6., as well as copper Byzantine coins, found in Bulgaria, as well as in a village near Murom (Zhiguli).

Significantly more Western European coins have been found in the Kama and Ural regions. In Udmurtia, 6 coins have been found: in the Chemshajskij and Kachkashurskij burial grounds, and two each in the Ves’jarsko-Bigershajskij and Kabakovskij burial grounds. In graves from the Kichil’kosskij burial mound (Northern Ural region), more than 50 coins have been collected. In the Perm’ region, around 15 have been found: Anglo-Saxon coins in the vicinity of Cherdyn and in the Chanwen cave, English denarii from 1042-1066 in the Arafonovskij II burial ground, and an Ethelred denarius in the Rozhdestvenskij burial ground.[51]Belavin, A.M. Kamskij torgovyj put’. Srednevekovoe Predural’e v ego ekonomicheskikh i etnokul’turnykh svjazjakh. Perm’, 2000, p. 186; Savel’eva, E.A. Vymskie mogil’niki XI-XIV vv. Leningrad, 1987, p. 167. Western European coins have also been found in the Mari Volga region: in Dubovskij, a denarius from Duke Ohrdulf (Otto) of Saxony (1059-1071) or Baron Hermann (1059-1086)[52]Fedorov-Davydov, G.A. “Monety Dubovskogo mogil’nika.” Novye pamjatniki arkheologii Volgo-Kam’ja. Arkheologija i etnografija Marijskogo kraja. Issue 8. Yoshkar-Ola, 1984, p. 165.; and in the Lower Strekkov region, an English denarius from 1017-1023.[53]Nikitina, T.B. “Inventar’ mogil’nika ‘Nizhnjaja Strelka.'” Drevnosti Povetluzh’ja. Issue 17: Arkheologija i etnografija Marijskogo kraja. Joshkar-Ola, 1990, p. 94.

In Biljar and a series of settlements in the Penza region, a number of metallic vessels (bronze goblets and aquamaniles) and other objects made in the Lower Lorraine and Aquitaine regions have been found. Similar 12th-13th century vessels, as well as those of Magyar and Byzantine make, have been found in Western Siberia. In the opinion of A.Ju. Borisenko and Ju.S. Khudjakov, they could have gotten there via Bulgarian merchants.[54]Khuzin, F.Sh. “Bulgarskaja tsivilizatsija i ee mezhdunarodnye svjazi.” Velikij Volshzkij put’. Kazan’, 2001, p. 48.

Other trade goods exported to Scandinavia through the Central Volga region include weights and scales, which have been found along the entire length of the Great Volga trade route; beads made of carnelian, crystal and glass; cowrie shells; clothing and fabric; metallic decorations for belts and horse tack; bronze vessels and fragments of silver vessels; and even a statuette of the Buddha from Kashmir; and more.[55]Jansson, 1999, p. 118.

On the whole, trade relations between Volga Bulgaria and Northern and Western Europe, which although of an indirect nature are included in Eurasian international trade, played a distinctly important role in the life of the peoples of these countries, especially in the 10th-11th centuries, when Northern trade routes were a priority.

Bibliography

- Artamonov, M.I. Istorija khazar. Moscow, 1962. 523 pp.

- Belavin, A.M. Kamskij torgovyj put’. Srednevekovoe Predural’e v ego ekonomicheskikh i etnokul’turnykh svjazjakh. Perm’, 2000. 196 pp.

- Valeev, R.M. Torgovlja i torgovye puti Srednego Povolzh’ja i Priural’ja v epokhu srednevekov’ja (IX-nachalo XV vv.). Kazan’, 2007. 391 pp.

- Garkavi, A.Ja. Skazanija musul’manskikh pisatelej o slavjanakh i russkikh (s pol. VII do kontsa X v. po R.X.). St. Petersburg, 1870. 308 pp.

- Dzhakson, T.N. “O jazycheskoj Bulgarii Snorri Sturlusona.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, pp. 28-35.

- Dubov, I.V. Velikij Volzhskij put’. Leningrad, 1989

- Izmajlov, I.L. Vooruzhenie i voennoe delo naselenija Volzhskoj Bulgarii X-nach. XIII v. Kazan’, 1999a. 212 pp.

- Izmajlov, I.L., “‘Rusy’ v Srednem Povolzh’e (etapy bulgaro-skandinavskikh etnosotsial’nykh kontaktov i ikh vlijanie na stanovlenie gorodov i gosudarstv.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999b, pp. 94-100.

- Izmajlov, I.L. “Baltijsko-Volzhskij put’ v sisteme torgovykh mgistralej i ego rol’ v rannesrednevekovoj istorii Vostochnoj Evropy.” Vilikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 69-78.

- Iz rannej istorii shvedskogo naroda i gosudarstva. Moscow, 1999. 332 pp.

- Kirpichnikov, A.N. “O nachal’nom etape mezhdunarodnoj torgovli v Vostochnoj Evrope v period rannego crednevekov’ja (po monetnym nakhodkam v Staroj Ladoge).” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Crednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, pp. 107-115.

- Kirpichnikov, A.N. “Velikij Volzhskij put’, ego istoricheskoe i mezhdunarodnoe znachenie.” Velikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 9-35.

- Kirpichnikov, A., Tolin-Bergman, L. Janson, I. “Novye kompleksnye issledovanija mechej epokhi vikingov iz sovranija Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja.” Slavjane, finno-ugry, skandinavy, volzhskie bulgary. St. Petersburg, 1999, pp. 100-125.

- Kovalevskij, A.P. Kniga Akhmeda ibn Fadlana o ego puteshestvii na Volgu v 921-922 gg. Khar’kov, 1956. 345 pp.

- Kropotkin, V.V. “Bulgarskie monety X v. na territorii Drevnej Rusi i Pribaltiki.” Volzhskaja Bulgarija i Rus’. Kazan’, 1986, pp. 36-82.

- Krylasova, N.V. “Podveska so znakom Rjurikovichej iz Rozhdestvenskogo mogil’nika.” Rossijskaja arkheologia. 1995 (2), pp. 192-197.

- Krylasov, L.P. “Torgovye puti i svjazi drevnekhakasskogo gosudarstva s Zapadnoj Sibir’ju i Vostochnoj Evropoj.” Proshloe Srednej Azii. Dushanbe, 1987, pp. 79-86.

- Lebedev, G.S. “Etjud o mechakh vikingov.” Arkheologicheskaja tipologija. Leningrad, 1991, pp. 280-304.

- Mel’nikova, E.A. “Baltijsko-Volzhskij put’ v rannej istorii Vostochnoj Evropy.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, pp. 80-87.

- Nikitina, T.B. “Inventar’ mogil’nika ‘Nizhnjaja Strelka.'” Drevnosti Povetluzh’ja. Issue 17: Arkheologija i etnografija Marijskogo kraja. Joshkar-Ola, 1990, pp. 81-118.

- Nunan, T. “Torgovlja Volzhskoj Bulgarii s samanidskoj Srednej Aziej v X v.” Arkheologija, istorija, numizmatika Vostochnoj Evropy. St. Petersburg, 2004, pp. 256-313.

- Polubojarinova, M.D. “Torgovlja Bolgara.” Gorod Bolgar. Kul’tura, iskusstvo, torgovlja. Moscow, 2008, pp. 27-107.

- Poljakova, G.F. “Izdelija iz tsvetnykh i dragotsennykh metallov.” Gorod Bolgar. Remeslo metallurgov, kuznetsov, litejschikov. Kazan’, 1996, pp. 154-168.

- Savel’eva, E.A. Vymskie mogil’niki XI-XIV vv. Leningrad, 1987. 200 pp.

- Semykin, Ju.A. “Nakhodka kol’tsevoj skandinavskoj fibuly iz Ul’janovskogo Povolzh’ja.” Velikij Volzhskij put’: istorija, formirovanija i razvitija. Kazan’, 2002, pp. 246-252.

- Fedorov-Davydov, G.A. “Monety Dubovskogo mogil’nika.” Novye pamjatniki arkheologii Volgo-Kam’ja. Arkheologija i etnografija Marijskogo kraja. Issue 8. Yoshkar-Ola, 1984, pp. 160-172.

- Khvol’son, D.A. Izvestija o khazarakh, burtasakh, bolgarakh, mad’jarakh, slavjanakh i russakh Abu Ali Akhmeda Ben-Omar ibn Dasta. St. Petersburg, 1870. 199 pp.

- Kheller, K. “Rannie puti iz Skandinavii na Volgu. Skandinavskaja ekspansija v vostochno-evropejskoe prostranstvo s nachala VIII veka.” Velikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 100-109.

- Kherrman, I. “Slavjane i normanny v rannej istorii Baltijskogo regiona.” Slavjane i skandinavy. Moscow, 1986, p. 8-128.

- Khuzin, F.Sh. “Bulgarskaja tsivilizatsija i ee mezhdunarodnye svjazi.” Velikij Volshzkij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 43-49.

- Jansson, I. “‘Oriental Import’ into Scandinavia in the 8th-12th Centries and the Role of Volga Bulgaria.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XVI vv. Kazan, 1999, pp. 116-122.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Iz rannej istorii shvedskogo naroda i gosudarstva. Moscow, 1999, p. 40. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Kirpichnikov, A.N. “Velikij Volzhskij put’, ego istoricheskoe i mezhdunarodnoe znachenie.” Velikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 13-14. |

| ↟3 | Artamonov, M.I. Istorija khazar. Moscow, 1962, p. 383. |

| ↟4 | Kirpichnikov, 2001, p. 19. |

| ↟5 | Kirpichnikov, A., Tolin-Bergman, L. Janson, I. “Novye kompleksnye issledovanija mechej epokhi vikingov iz sovranija Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja.” Slavjane, finno-ugry, skandinavy, volzhskie bulgary. St. Petersburg, 1999, p. 121. |

| ↟6 | Jansson, I. “‘Oriental Import’ into Scandinavia in the 8th-12th Centries and the Role of Volga Bulgaria.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XVI vv. Kazan, 1999, p. 120 |

| ↟7 | Kirpichnikov, et.al., 1999, pp. 108-109; Izmajlov, I.L. Vooruzhenie i voennoe delo naselenija Volzhskoj Bulgarii X-nach. XIII v. Kazan’, 1999a, p. 34. |

| ↟8 | Valeev, R.M. Torgovlja i torgovye puti Srednego Povolzh’ja i Priural’ja v epokhu srednevekov’ja (IX-nachalo XV vv.). Kazan’, 2007, p. 118, Illus. 153-155. |

| ↟9 | Kirpichnikov, et.al., 1999, pp. 109-110. |

| ↟10 | Kherrman, I. “Slavjane i normanny v rannej istorii Baltijskogo regiona.” Slavjane i skandinavy. Moscow, 1986, p. 81. |

| ↟11 | Lebedev, G.S. “Etjud o mechakh vikingov.” Arkheologicheskaja tipologija. Leningrad, 1991, p. 289. |

| ↟12 | Herrman, 1986, p. 81. |

| ↟13 | Khvol’son, D.A. Izvestija o khazarakh, burtasakh, bolgarakh, mad’jarakh, slavjanakh i russakh Abu Ali Akhmeda Ben-Omar ibn Dasta. St. Petersburg, 1870, p. 158. |

| ↟14 | Garkavi, A.Ja. Skazanija musul’manskikh pisatelej o slavjanakh i russkikh (s pol. VII do kontsa X v. po R.X.). St. Petersburg, 1870, p. 282. |

| ↟15 | Polubojarinova, M.D. “Torgovlja Bolgara.” Gorod Bolgar. Kul’tura, iskusstvo, torgovlja. Moscow, 2008, p. 93. |

| ↟16 | Kyzlasov, L.R. “Torgovye puti i svjazi drevnekhakasskogo gosudarstva s Zapadnoj Sibir’ju i Vostochnoj Evropoj.” Proshloe Srednej Azii. Dushanbe, 1987, p. 83; Polubojarinova, 2008, p. 34. |

| ↟17 | Poljakova, G.F. “Izdelija iz tsvetnykh i dragotsennykh metallov.” Gorod Bolgar. Remeslo metallurgov, kuznetsov, litejschikov. Kazan’, 1996, pp. 154-168. |

| ↟18 | jeb: See illustration 3, left (labeled “24”). |

| ↟19 | Izmajlov, I.L., “‘Rusy’ v Srednem Povolzh’e (etapy bulgaro-skandinavskikh etnosotsial’nykh kontaktov i ikh vlijanie na stanovlenie gorodov i gosudarstv.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999b, p. 97. |

| ↟20 | Semykin, Ju.A. “Nakhodka kol’tsevoj skandinavskoj fibuly iz Ul’janovskogo Povolzh’ja.” Velikij Volzhskij put’: istorija, formirovanija i razvitija. Kazan’, 2002, p. 248-250. |

| ↟21 | Poljakova, 1996. |

| ↟22 | jeb: See illustration 3, right (labeled “25”). |

| ↟23 | Dubov, I.V. Velikij Volzhskij put’. Leningrad, 1989, p. 119. |

| ↟24 | Semykin, 2002, pp. 251-252. |

| ↟25 | Dubov, 1989, p. 187, Illustration 57, item 6; Mel’nikova, E.A. “Baltijsko-Volzhskij put’ v rannej istorii Vostochnoj Evropy.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, p. 84. |

| ↟26 | Krylasova, N.V. “Podveska so znakom Rjurikovichej iz Rozhdestvenskogo mogil’nika.” Rossijskaja arkheologia. 1995 (2), pp. 192-197; Mel’nikova, 1999, pp. 84-85; Izmajlov, 2001, p. 73. |

| ↟27 | jeb: See illustration 4. |

| ↟28 | Izmajlov, I.L. “Baltijsko-Volzhskij put’ v sisteme torgovykh mgistralej i ego rol’ v rannesrednevekovoj istorii Vostochnoj Evropy.” Vilikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, p. 76. |

| ↟29 | jeb: The Old Norse term for Rus’. |

| ↟30 | Dzhakson, T.N. “O jazycheskoj Bulgarii Snorri Sturlusona.” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Srednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, p. 31. |

| ↟31 | idem., p. 34. |

| ↟32 | Kovalevskij, A.P. Kniga Akhmeda ibn Fadlana o ego puteshestvii na Volgu v 921-922 gg. Khar’kov, 1956, pp. 141-146. |

| ↟33 | Kheller, K. “Rannie puti iz Skandinavii na Volgu. Skandinavskaja ekspansija v vostochno-evropejskoe prostranstvo s nachala VIII veka.” Velikij Volzhskij put’. Kazan’, 2001, pp. 101-102. |

| ↟34 | Nunan, T. “Torgovlja Volzhskoj Bulgarii s samanidskoj Srednej Aziej v X v.” Arkheologija, istorija, numizmatika Vostochnoj Evropy. St. Petersburg, 2004, p. 258. |

| ↟35 | Herrman, 1986, p. 80. |

| ↟36 | Herrman, 1986, pp. 80, 82, Illustration 33. |

| ↟37 | idem., pp. 77, 82. |

| ↟38 | Nunan, 2004, p. 258. |

| ↟39 | Kirpichnikov, A.N. “O nachal’nom etape mezhdunarodnoj torgovli v Vostochnoj Evrope v period rannego crednevekov’ja (po monetnym nakhodkam v Staroj Ladoge).” Mezhdunarodnye svjazi, torgovye puti i goroda Crednego Povolzh’ja IX-XII vekov. Kazan’, 1999, p. 112. |

| ↟40 | Nunan, 2004, p. 260, plate 1. |

| ↟41 | ibid., pp. 260-261, plate 2. |

| ↟42 | Nunan, 2004, p. 261, plate 3. |

| ↟43 | ibid., p. 266. |

| ↟44 | idem., pp. 292-294, plates 4-6. |

| ↟45 | idem., pp. 295-296. |

| ↟46 | Jansson, 1999, p. 117. |

| ↟47 | Kropotkin, V.V. “Bulgarskie monety X v. na territorii Drevnej Rusi i Pribaltiki.” Volzhskaja Bulgarija i Rus’. Kazan’, 1986, pp. 38-57. |

| ↟48 | idem., pp. 49-54. |

| ↟49 | jeb: A province in modern-day Belgium. |

| ↟50 | jeb: See illustration 6. |

| ↟51 | Belavin, A.M. Kamskij torgovyj put’. Srednevekovoe Predural’e v ego ekonomicheskikh i etnokul’turnykh svjazjakh. Perm’, 2000, p. 186; Savel’eva, E.A. Vymskie mogil’niki XI-XIV vv. Leningrad, 1987, p. 167. |

| ↟52 | Fedorov-Davydov, G.A. “Monety Dubovskogo mogil’nika.” Novye pamjatniki arkheologii Volgo-Kam’ja. Arkheologija i etnografija Marijskogo kraja. Issue 8. Yoshkar-Ola, 1984, p. 165. |

| ↟53 | Nikitina, T.B. “Inventar’ mogil’nika ‘Nizhnjaja Strelka.'” Drevnosti Povetluzh’ja. Issue 17: Arkheologija i etnografija Marijskogo kraja. Joshkar-Ola, 1990, p. 94. |

| ↟54 | Khuzin, F.Sh. “Bulgarskaja tsivilizatsija i ee mezhdunarodnye svjazi.” Velikij Volshzkij put’. Kazan’, 2001, p. 48. |

| ↟55 | Jansson, 1999, p. 118. |