Today’s post is my translation of N.A. Majasova’s overview of 5 items of Muscovite ecclesiastical embroidery from the late 14th-early 15th centuries, influenced by or possibly related to the workshop of the icon painter Dionisius.

Several Examples of Muscovite Embroidery from the Time of Dionisius

A translation of Маясова, Н.А. “Группа памятников московского шитья времени Дионисии.” Ферапонтовский сборник. 1995(5), pp. 208-222.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[Note that the original article had photographs in black and white. Where possible, I’ve replaced them with color images found online.]

[The article in the original Russian was originally found online here:

http://oz-gora.ru/d/513321/d/n.a.mayasova—gruppa-pamyatnikov-moskovskogo-shitya.pdf ]

Just as Muscovite art from the late 14th-early 15th centuries is illuminated by the genius of Andrej Rublev, so too is that of the second half of the 15th-early 16th centuries inseparable from the name of Dionisius. The creative work of this master and the artists of his circle is evident not only in frescos, icons and miniatures, but also in the ecclesiastical embroidery of that period.

The “Dionisian” style is particularly pronounced in works from the atelier of Grand Prince Vasilij III’s first wife, Solomonia Saburova, from the first quarter of the 16th century.[1]Vasilij Ivanovich married Solomonia Jur’evna Saburova in 1505, but in 1525 she was forced to enter Suzdal’s Pokrovskij Monastery “as a result of barrenness.” We should note that Solomonia’s works in the final years of her marriage are already no longer closely tied to the artistic style of Dionisius. For example, the 1525 podea of the Appearance of the Holy Mother to St. Sergius (Sergiev-Posad museum, inventory number 409) or the “St. Sergius of Radonezh” veil of the same year (ibid., inventory number 410). This school is attributed with the creation of palls on the tombs of several saints (Metropolitan Peter, Leontij of Rostov, Cyril of Beloözero, Pafnutij of Borovsk[2]The “Metropolitan Peter” veil of 1512 is stored in the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin (inv. TK-36), the “Leontij Rostovskij” of 1514 in the Rostov Museum (inv. TS-921/51), the “St. Cyril of Beloözersk” of 1514 in the State Russian Museum (inv. DRT-306), as is the “Pafnutij of Borov” (DRT-297).), the podea “Cyril of Beloözero with Scenes of His Life” under the icon of the same name in the Assumption Cathedral in the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery[3]State Russian Museum, inv. DRT-276. (Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971, p. 26, illus. 40)., and a podea with a half-length image of St. Nikolaj intended, we think, for the “Secret” image of St. Sergius[4]Sergiev-Posad Museum, inv. 668 (ibid., p. 22, illus. 32). The icon is in the same location (inv. 388); in 1993, it was given to the Moscow Patriarchate. Several researchers date it to the late 15th or even early 16th century. (Kochekov, I.A. “Ikona ‘Nikola’ izvestnaja kak kelejnaja prepodobnogo Sergija.” Istorija i kul’tura Rostovskogo zemli. Rostov, 1994, pp. 56-59)..

The “Dionisian” style is also repeatedly noted in works by other masters, for example, in the podea “The Birth of the Holy Virgin” from 1510 with an inscription about how it was created by Princess Anna, spouse of the Prince of Volotsky, Fedor Borisovich[5]State Tretyakovskaya Gallery, inv. 20930 (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 23-24, illus. 34).

However, the participation by Dionisius or artists in his close circle can be traced also in the creation of several embroidered items from the last quarter of the 15th century. To this in particular should be included a group of podeai which were undoubtedly embroidered at one of the Moscow ateliers. Several of them attracted the attention of scholars even in the pre-Revolutionary era, however they were not tied together at that time. The first proposal that four of these items were made in the same workshop was published in 1971[6]ibid., pp. 14-15, illus. 12, 13, 14, 15.. Today, we include seven or possibly even eight works in this group. They are stored today in various museums, and it is not always possible to determine their original origin.

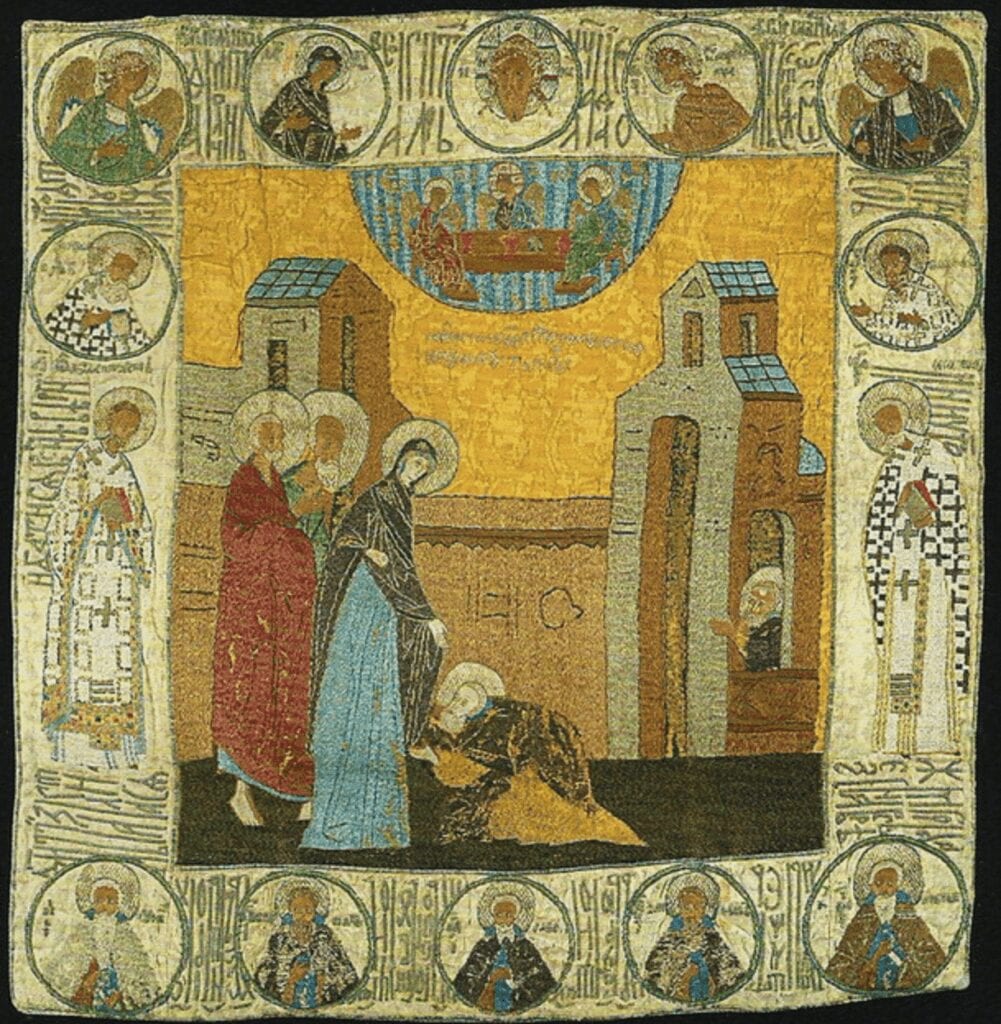

Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. [Color photo obtained online here.]

In scientific literature, the most well-known of these works is the podea “Our Lady of the Burning Bush, with Selected Saints” from the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery (illus. 1)[7]State Russian Museum, inv. DRT-31; size 54 x 52 cm. (Varlaam, arkhim. “Opisanie istoriko-arkheologicheskoe drevnostej i redkikh veschej, nakhodjaschikhsja v Kirillo-Belozerskom monastyre.” Chtenija v Imperatorskom obschestve istorii i drevnostej Rossijskikh pri Moskovskom universitete. Vol 3, 1859, pp. 62-63; Schekotov, N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Sofia, 1914, p. 13; Nikolaeva, T.V. Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva s nadpisjami XV-pervoj chetverti XVI veka. Moscow, 1971, pp. 61-62, No. 45; Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 14-15, illus. 14 (here for the first time, instead of Our Lady of the Sign, the podea is called the Burning Bush); Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo XV-nachala XVIII veka v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Russkogo muzeja. Katalog vystavki. Leningrad, 1980, p. 14, illus. p. 129).. In the center of the podea, on bright-yellow Italian damask, Our Lady of the Sign is embroidered against the background of the burning bush. To her left is a flying angel; on her right, Moses removes his sandals. Below, in prayer, stand the Metropolitans Peter and Aleksej with arms outstretched in front of each other, Leontij of Rostov and Sergius of Radonezh, and Cyril of Beloözero and Varlaam of Khutyn. Around the edges on brown damask are 16 round medallions, between which in thin, narrow knitted letters [vyaz’] are embroidered the lyrics of the chant for Holy Saturday, “Let all human flesh be silent…”[8]The chant “Let all human flesh be silent…” from the Liturgy of St. Basil of Caesarea (chapter 8) is sung at the Sabbath’s Supper instead of the Cherubim.. In the medallions on the upper border are the Mandylion in the center, and around him in a Deësis are half-length figures of the archangels Michael and Gabriel and the apostles Peter and Paul; on the side borders, in three-quarter profile turned toward the center, are half-length figures of Sts. John Chrysostom and Basil of Caesarea, Nikolaj the Miracle-Worker and Gregory the Theologian, and Anthony of the Caves and Euphemius of Suzdal’; on the lower border are forward-facing images of Theodosius of the Caves, Savva Visherskij, Varlaam of Khutyn, Tsarevich Ioasaf, and Dmitrij Prilutsky. A name is inscribed under every image.

We recall that the name “Our Lady of the Burning Bush” is typically assigned to icons mainly in the 16th-17th centuries showing the Holy Mother with the infant Christ in her left hand, a “non-rugged” mountain and stairs on her right, against a background of overlapping green and red diamonds representing the bush and fire[9]Antonova, V.I., Mneva, N.E. Katalog drevnerusskoj zhivopisi [GTG]. Vol. 2. Moscow, 1963, No. 373, 623, 829.. The earliest Christian interpretations of the Biblical subject of the appearance of an angel to Moses in a burning bush on Mt. Sinai, directing him in the voice of the Lord to lead the Jews from captivity in Egypt[10]Exodus, 3:3-5., are known only in several monuments of the Byzantine world from the 11th-15th centuries, in particular in the Church of the Holy Savior in Chora, and in St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai[11]Weitzmann, K. “The Mosaic in St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai.” Studies in the Arts at Sinai. Princeton, 1982, fig. 9, 14.. Among Russian works, analogies to this iconography are likewise found extremely infrequently. We can name two depictions, one on the western “golden” gates from the mid-16th century in the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin[12]Kachalova, I.Ja., Majasova, N.A., Schennikova, L.A. Blagoveschenskij sobor Moskovskogo Kremlja. Moscow, 1990, illus. 223., and along with other Biblical miracles, on the edge of “Old Testament Trinity” podea from 1593 donated by Dmitrij Ivanovich Godunov[13]Museums of the Moscow Kremlin, inv. TK-2824 (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, illus. 51).. We also encounter this composition, divided into two parts, placed in round frames in the corners of an icon with the typical iconography of the burning bush in the Ryabushinsky collection[14]Vystavka drevnerusskogo iskusstva, ustroennaja v 1913 godu v oznamenovaniie 300-letija tsarstvovanija Doma Romanovykh. Moscow, 1913, No. 68.. Also rare is the iconography of the Deësis in the upper border, where the Holy Mother and John the Baptist are absent, and in the center is not Christ Pantocrator, as usual, but an image of the Mandylion.

Podea (Sudarium?), 1480s, Museums of the Moscow Kremlin.

It is noteworthy that this image was depicted on four works from our group of monuments, in particular on the most similar to the “Burning Bush” podea, another podea with the image of the Appearance of the Holy Virgin to St. Sergius in the center (illus. 2)[15]Museums of the Moscow Kremlin, inv. TK-2552; size 51 x 49 cm (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 15, illus. 15).. This podea was transferred in the 1920s to the Armory of the State Museum Fund, and its original location is unknown. It is possible that it came from one of the Kremlin churches. In any event, these podeai were embroidered contemporaneously, as the very same bright-yellow damask was used as the base for both items. The subject of this podea is based on an episode from the Life of Sergius of Radonezh[16]Velikie Minei Chetij, sobrannye vserossijskim metropolitom Markiem. Sentjabr, dni 25-30. St. Petersburg, 1883, stb. 1442-1444. and received widespread use not only in iconography, but also in “small-form sculpture” [melkaja plastika] and embroidery. The earliest mention of it is a funerary icon with which Vasilij II, having taken refuge in the Trinity Monastery, rode out against his enemies in 1446[17]Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej [PSRL], vol. 12, p. 198.. We, as well as other researchers, have noted several times that this subject is known in two basic variants – one with St. Sergius standing before the Holy Virgin, and the other with him kneeling, as seen on this podea[18]Majasova, N.A. “Obraz prepodobnogo Sergija Radonezhskogo v drevnerusskom shit’e (k voprosu ob ikonografii.” Drevnerusskoe iskusstvo. Sergij Radonezhskij i khudozhestvennaja kul’tura Rusi XIV-XV veka. (out for publication); Guseva, E.K. “Osobennosti slozhenija ikonografii ‘Javlenie Bogomateri Sergiju” (lecture given 3 Oct 1992 at Danilov Monastery at the International Scientific Conference “The Venerable Sergij of Radonezh and Traditions of Russian Spirituality”).. As both iconographic variants are seen on mid-15th century crosses by the Trinity Monastery’s Amvrosij the Carver[19]An altar cross with Sergius erect (Sergiev Posad Museum, inv. 1847) and an altar cross with Sergius on his knees (ibid., inv. 2389); Nikolaeva, T.V. Proizvedenija melkoj plastiki XIII-XVII vekov v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Zagorsk, 1960, No. 155, 157., we believe that they developed simultaneously, depicting different moments of the same event.

The “Old Testament Trinity” depicted above the main composition indicates the location of the “Appearance”, but also perhaps the location to which the item was donated – one of the Trinity Churches. The upper border of pale yellow brocade depicts, just as on the first icon, a Deësis composition with the Mandylion in the middle. However, the iconography here is traditional, with the Holy Virgin, John the Baptist, and archangels. The structure of the side borders is also changed. Here, there are only two medallions with St. Gregory the Theologian and St. Basil of Caesarea; St. John Chrysostom and St. Nikolaj the Miracle-worker are shown full-length. On the lower border, there are five medallions with half-length images of Euphemius of Suzdal’, Cyril of Beloözero, Savva Visherskij, Varlaam of Khutyn, and Anthony of the Caves. Between these images, the familiar woven writing spells out the same chant as on the first podea.

In the Works of the VIII Archeological Congress, an “embroidered icon” from the Tver Museum, which was on display at the congress in 1890, was published (illus. 3)[20]Trudy VIII Archeologicheskogo s’ezda. Vol. 4. Moscow, 1897, p. 226; unfortunately the location of the podea is today unknown.. In its center is depicted The “Cloudy” Dormition of the Virgin, but the borders are decorated as on the “Burning Bush” – half-length saints in round medallions, between which are located thin letters of thickly knit writing. On the upper border is the Mandylion with two archangels and the apostles Peter and Paul. On the side and lower borders in 11 medallions are depicted, based on the iconography, the same saints and in the same locations as on the first podea, with the exception of Varlaam and Tsarevich Ioasaf.

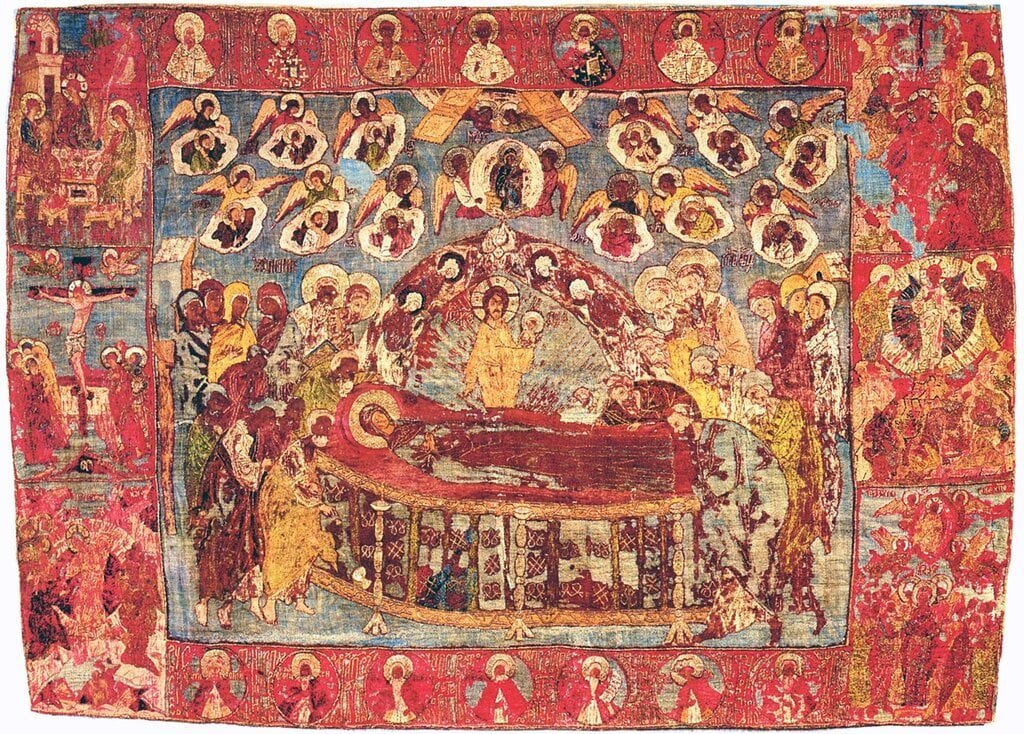

In 1951, the Hermitage obtained an almost identical podea from the private collection of I.A. Gal’ibek[21]State Hermitage Museum, inv. E/PT-7976; size 39.5 x 39.5 cm; Kostsova, A., Moiseenko, E. “Dve shitie ikony XV veka.” Soobschenija Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha. Vol. XLII. Leningrad, 1977, pp. 18-21. During restoration at the Hermitage in the 1960s, the background of the piece was “slightly tinted with watermarks, in a color close to that of crimson damask.” The lining is made of blue tulle. The podea has been glued to a silk fabric and plywood (ibid., p. 21, example 7).. The “Cloudy” Dormition is also embroidered on this item, on raspberry brocade (illus. 4). However, in contrast to the previous podeai, this one includes the scene of the angel cutting off the hands of the wicked Avfonia. The compositions and other details (the poses of several apostles, the turn of the figure of the exalted Holy Mother, the forms of the clouds and architecture, etc.) differ. At the same time, here we have the same proportions of figures, drawing of faces and structure of the border, duplicating that of the first podea, embroidered on light-blue greenish taffeta. Above are the Mandylion, archangels, and the apostles Peter and Paul. In the remaining 11 medallions are John Chrysostom and Basil of Caesarea, Gregory the Theologian and Nikolaj the Miracle-Worker, Leontij of Rostov and Euphemius of Suzdal’, Theodosius of the Caves, Sergius of Radonezh, Varlaam of Khutyn, Tsarevich Ioasaf, and Anthony of the Caves. All of the space between the medallions is filled with a chant to the Holy Virgin in the same calligraphy[22]”DNS’ BLGOVRNII SVETLO PRAZNUEM OCENJAEMI TVOIM BOGMTI PRISHESTVIEM I K TVOEMU PRCHSTMU VZRAJUSCHE OBRAZU UMILNO GLEM’ POKRY NAS” TSENYM POKROVOM” I IZB’VI H’ OT VSJAKOGO ZLA MOLJASCHI SNA SVOEVO KHRI BA HASHGO SPSTISJA DSHA NASHA.” The inscription comes from the aforementioned book by A. Kostsova and E. Moiseenko, p. 20..

One more podea of the Dormition of the Virgin, similar to the previous, comes from the Svyato-Uspensky Knjaginin Monastery in Vladimir (illus. 5)[23]State Tretyakovskaya Gallery, inv. 20981, size 62.5 x 100 cm (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 14, illus. 13). The original medieval background (brown brocade) no longer exists; the embroidery is now fixed to coarse blue homespun cloth. The silk embroidery, especially on the faces, has been largely lost The inscription is also very poorly preserved. . It is almost twice as wide as the other items; as a result, the composition of the Dormition embroidered in its center is stretched out and contains a greater number of figures in the crowd around the Virgin’s bed. The scene of the “cutting off the hands of Avfonia” is missing, but in front of the bed stand three figural candlesticks which serve as a distinctive feature of this podea. Another distinguishing feature of this composition are the wide-open gates of Heaven, with angels prepared to receive the ascending Holy Mother. All three treatments of the Dormition belong to established iconographical variations of the “Cloudy Dormition” canon, which developed in Muscovite iconography in the second half and, in particular, the last third of the 15th century. However, they are not all identical. Each of them is oriented toward different variations of the canon which were common at that time. The most significant is the Vladimir podea, despite the iconographic nuances (the absence of the scene with Avfonia); in its artistic style and expressiveness, it can be compared to similar well-known works of the Dionisius circle, including icons from Kirillov[24]Lelekova, O.V. “Ikonostas 1497 goda iz Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja.” Pamjatniki kul’tury. Novye Otkritija. Ezhegodnik, 1976. Moscow, 1977, pp. 187-190, illus. on p. 189 (now in the Tretyakovskaya Gallery.) and Dmitrov[25]Popov, G.V. Khudozhestvennaja zhizn’ Dmitrova v XV-XVI vekakh. Moscow, 1973, pp. 78-86, illus. 13..

As for the borders of raspberry silk on the Vladimir podea, with the exception that the Mandylion is not present, the upper and lower edges are decorated as is traditional for our group of podeai under study: each has 7 medallions depicting half-length saints, and between them in the same woven writing, the words of a chant are spelled out in long, narrow letters in gold thread. The selection of saints is also the same. In the center of the upper border is St. John Chrysostom, and on either side are Basil of Caesarea and Gregory the Theologian, Nikolaj and the only new saint named John (the Merciful?), Metropolitans Peter and Aleksej. On the lower border are Anthony and Theodosius of the Caves, Euphemius of Suzdal’, Savva Visherskij, Varlaam, Tsarevich Ioasaf, and Dmitrij Prilutsky. Three holidays are depicted on each of the side borders: on the left, the Trinity, the Crucifixion, and the Harrowing of Hell; on the right, the Baptism of Christ, the Transfiguration, the Ascension. If the iconography of the saints in the medallions is identical to that on other images in the group, here the holidays are similar to those on the Trinity Sudarium from the Trinity-Sergius Lavra (illus. 6), and above all to the “Old Testament Trinity” itself[26]Sergiev-Posad Museum, inv. 361; size 55 x 51 cm (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 14, illus. 12). The original background has not survived. During restoration in 1951, the images were transferred from the previous red velvet to dark blue homespun..

Many researchers have attributed the sudarium, or as it was called earlier, the podea The Trinity with Holidays to the beginning of the 15th century, and even thought it a replica of an icon by Rublev[27]Antonova, V.I. “O pervonachal’nom meste ‘Troitsy’ Andreja Rubleva.” Materialy i Issledovanija Gos. Tret’jakovskogo galerei. Issue 1. Moscow, 1956, pp. 26-30.. In reality, the head icon painter, repeating what is at its core a Rublev standard, tried to convey the general mood of the great work. He made, however, some of his own adjustments. Here, there are several different correlations of the figures, causing the circularity of the composition to fall apart: on the table, there are three chalices instead of one, and the tower behind the angel on the left has become more complex in form. This work is of a different time. Based on its differences, it is more similar to monuments of the end of the 15th and early 16th centuries, such as the Volokolamsk icon of Paisius from 1485, or icons from Kolomna (late 15th century) and the Makhrischsky Monastery (early 16th century), or a few others[28]Vzdornov, G.I., ed. Troitsa Andreja Rubleva. Antologia. Moscow, 1989, illus. 43, 44, 47., although this Trinity from Sergiev-Posad is more lyrical.

The holidays sewn on the borders of the Vladimir Dormition and the Sergiev-Posad Trinity mirror the variants, widely in use in the 15th century among Muscovite artists, in that several are similar to compositions developed in the first half of the century by Rublev’s followers. We note when comparing the Vladimir Dormition to the Sergiev Trinity that, having lost its original base of green sand-colored brocade, the holidays are now separated by significant unfilled distances. We must imagine that, as with the other items in this group of works, these spaces were originally filled with long, thin letters of a liturgical inscription.

[Color photo obtained online here.]

Supporting this theory, based on our interpretation, is a seventh monument of this group, the Kirillov podea of the Transfiguration (illustration 7)[29]State Russian Museum, inv. DRT-19; size 49 x 51.8 cm: Likhacheva, L.D., ed. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo XV-nachala XVIII veka v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Russkogo muzeja. Katalog vystavki. p. 12, illus. p. 128. This podea is better preserved than the other members of this group, and therefore seems a bit bright and garish by comparison.. The composition embroidered in its center on green satin is of an abbreviated form without the scenes of the apostles climbing up and down the mountain before and after the event. The twelve holidays embroidered on the raspberry taffeta border (the Annunciation, the Birth of Christ, Candlemas, Epiphany, the Raising of Lazarus, the Entry into Jerusalem, the Crucifixion, the Descent into Hell, the Trinity, and the Dormition of the Virgin) are similar to those on the Trinity sudarium from Sergiev Posad, but the spaces between them are filled with the lyrics of a chant for the Transfiguration, sewn in gold thread in the familiar woven writing, the narrow letters of which, sewn in two or sometimes even three layers, are not without a certain grace.

T.V. Nikolaeva, studying the Burning Bush podea from a paleographic point of view, noted: “despite the fanciful style of the thin, narrow letters, this is not yet the well-developed woven writing style of the 16th century. There are few ligatures in the inscription, and there is no use of the newer forms of the letters A, Ja, U, et.al.” This evidence “does not allow us to date this work any later than the 1480’s.”[30]Nikolaeva, Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva…, p. 62.

Related to these inscriptions, we should look at the function of these works. With the exception of the Vladimir Dormition, which undoubtedly served as a suspended podea under the local row of the iconostasis and perhaps on holidays as a portable icon, the remaining items of our study appear to be sudaria. The Sergiev Posad Trinity followed the example of another Godunov podea of the same size, designated in the monastery’s inventory of 1641 as “a veil for the Sergius’ face”[31]Opis’ Troitse-Sergieva monastyrja 1641 goda, leaf 96-96 obv. (Sergiev-Posad Museum, inv. 289)., in our opinion. As for the Burning Bush and Appearance of the Virgin to St. Sergius, the song embroidered on their borders (“Let all human flesh be silent…”), performed on Holy Saturday during the presentation of the gifts and more typically seen on shrouds and Aërs, veils placed over liturgical vessels, speaks to its intended use. Based on size, the smaller Dormition and Transfiguration items could also have been used for this purpose, although they lack the embroidered holiday chants.

It is noteworthy that one more item certainly having come from the same workshop as the items above is called “a sudarium” in the 1545 Inventory of the Iosifo-Volokolamsk Monastery. There, on the altar of the Cathedral of the Dormition amongst other liturgical items, is mentioned “a sudarium of the Dormition of the Holy Virgin with clouds and apostles. Embroidered on dark blue taffeta. On the Savior, and on the Most Pure One, and on the saints and angels, and on the apostles there are crowns embroidered in gold. And the border is of crimson taffeta, and on the taffeta is embroidered the image of the Savior Not Made By Hands, and on either side are the archangels and Peter and Paul, and on the sides and bottom are embroidered images of the holy saints and venerable ones, and all are embroidered with golden crowns, and a large inscription is embroidered in yellow silk.”[32]Inventory of the Iosif-Volokolamsk Monastery of 1545 (7053). (Georgievskij, V.T. Freski Ferapontova monastyrja. St. Petersburg, 1911, Attached, p. 6. This description fits two other works of the group, and if this is not the sudarium which ended up in the Tver museum, then this could refer to an eighth work of our workshop. At earliest, this work would have been created in 1484-1485, when the stone Cathedral of the Assumption in the monastery was built and decorated, which does not contradict the dating of our other items.

All of the works in our group were embroidered in silk of various colors on bright silk fabrics. Wrapped silver and gold threads were used only in specific details (haloes, crosses on sakkoses, inscriptions, etc.). The golden threads follow the contours and outlines of the design. The stitches are straightforward: silk split-stitch, with golden threads couched in a basketweave pattern. The stitching of faces and hands does not follow the form of the design – they are sewn in one direction, without shading. Although these are characteristic signs of Muscovite embroidery of the second half of the 15th century, their combination and overall manner of performance, along with other unifying features, speak to their coming from a single workshop.

There may have been more than one master iconographer: the Trinity and the Transfiguration seem to have been earlier and, perhaps, were drawn by a different artist than the rest; but, all of the works were carried out in a single artistic style, similar to that prevailing in the circle of Dionisius. This is especially true of the first two items. Here we see the same slender, elongated figures with small heads and hands, the same soft rhythm of movement, and gravity of composition. It is not by chance that N. Schekotov, one of the first researchers of medieval Russian embroidery, holds up the Kirillo-Belozersky Burning Bush as an example of the formation of our national style[33]Schekotov, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 13.. As for our assumption that artists from the Dionisian school participated in the creation of these works, we should also consider the rather formal details of the structure of the works, such as the placement of half-length images of saints in round medallions, a technique used by those artists, as well as by Ferapontov in his paintings in Moscow’s Cathedrals of the Dormition and of the Annunciation.

Finally, we should note the general ideological plan that guided the patron of these works. The image of a row of Greek fathers of the church alongside a whole host of Russian saints worshiped in Moscow at the end of the 15th century suggests a significant reason for their creation. The image of the Mandylion, typically placed on Russian banners of war where, as the Chronicle says about Dmitrij Donskoj’s banner, “it shone like the sun,” suggests a prayer from all mankind for deliverance from enemy invasion. We here recall the 1389 Aër by Grand Princess Maria Alexandrovna, wife of Simeon the Proud, undoubtedly a monument to the victory at the Battle of Kulikovo, which features one of the earliest half-length Deësis images with the Mandylion in the center[34]State Historical Museum, inv. RB-1 (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 10-11, illus. 5).. We agree with T.V. Nikolaeva who suggests that, based on the makeup of its selected saints, the Burning Bush podea (she refers to it as “Our Lady of the Sign”) is connected with the “uprise” on the Ugra and the fall of the Tatar yoke[35]Nikolaeva, Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva…, p. 62.. It is worth remembering the chroniclers’ mention that at that time in the Cathedral of the Dormition and in other churches, national prayers were held, and “then there was a glorious miracle… God forbade the Russian land from the foul Tatars, thanks to the prayers of the Most Pure Mother of God and the great Miracle-Workers.”[36]PSRL, Vol. 12, p. 202. To this end, the images of Rostov’s Metropolitan Varlaam and of Tsarevich Ioasif are seen on four of our podeai, as a reminder of Varlaam’s edifying missive about the Ugra. Moreover, the image of the Burning Bush likens the “deeds” of the Prince of Moscow to the great deeds of Moses. The use of the Life of Sergius of Radonezh is also clear, as he was associated with the victories of Dmitrij Donskoj; also, the Dormition of the Virgin, as the main representative before God for the Russian land, and who called the Dormition Cathedral “home”.

All of the above, as well as the appearance of St. John Chrysostom, heavenly patron of Ivan III[37]On the Appearance of the Holy Virgin to St. Sergius podea has St. John Chrysostom depicted in full length on the side border across from St. Nikola; on the Dormition from Vladimir, he is in the center of the upper border., gives cause to consider the item in question to be a work of the Grand Prince’s workshop from the 1480s. It is not by chance that the most significant work of the group, the Burning Bush podea, was in the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, where the Grand Prince “sent” Sophia Fominishna “because of the Tatars.”[38]PSRL, Vol. 12, p. 212. In this way, the reviewed works fill the gap existing between the monuments which have survived to today from this 15th century workshop (St. Sophia’s Epitaphios of Vasilij II of 1456 and the podea of Our Lady of Smolensk from the 1460s) and items by that workshop from the 1490s (the podeai by Elena of Moldova and Sophia Palaiologina)[39]On these works: Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 9, 19-22, illus. 26-31..

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Vasilij Ivanovich married Solomonia Jur’evna Saburova in 1505, but in 1525 she was forced to enter Suzdal’s Pokrovskij Monastery “as a result of barrenness.” We should note that Solomonia’s works in the final years of her marriage are already no longer closely tied to the artistic style of Dionisius. For example, the 1525 podea of the Appearance of the Holy Mother to St. Sergius (Sergiev-Posad museum, inventory number 409) or the “St. Sergius of Radonezh” veil of the same year (ibid., inventory number 410). |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | The “Metropolitan Peter” veil of 1512 is stored in the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin (inv. TK-36), the “Leontij Rostovskij” of 1514 in the Rostov Museum (inv. TS-921/51), the “St. Cyril of Beloözersk” of 1514 in the State Russian Museum (inv. DRT-306), as is the “Pafnutij of Borov” (DRT-297). |

| ↟3 | State Russian Museum, inv. DRT-276. (Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1971, p. 26, illus. 40). |

| ↟4 | Sergiev-Posad Museum, inv. 668 (ibid., p. 22, illus. 32). The icon is in the same location (inv. 388); in 1993, it was given to the Moscow Patriarchate. Several researchers date it to the late 15th or even early 16th century. (Kochekov, I.A. “Ikona ‘Nikola’ izvestnaja kak kelejnaja prepodobnogo Sergija.” Istorija i kul’tura Rostovskogo zemli. Rostov, 1994, pp. 56-59). |

| ↟5 | State Tretyakovskaya Gallery, inv. 20930 (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 23-24, illus. 34) |

| ↟6 | ibid., pp. 14-15, illus. 12, 13, 14, 15. |

| ↟7 | State Russian Museum, inv. DRT-31; size 54 x 52 cm. (Varlaam, arkhim. “Opisanie istoriko-arkheologicheskoe drevnostej i redkikh veschej, nakhodjaschikhsja v Kirillo-Belozerskom monastyre.” Chtenija v Imperatorskom obschestve istorii i drevnostej Rossijskikh pri Moskovskom universitete. Vol 3, 1859, pp. 62-63; Schekotov, N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Sofia, 1914, p. 13; Nikolaeva, T.V. Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva s nadpisjami XV-pervoj chetverti XVI veka. Moscow, 1971, pp. 61-62, No. 45; Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 14-15, illus. 14 (here for the first time, instead of Our Lady of the Sign, the podea is called the Burning Bush); Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo XV-nachala XVIII veka v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Russkogo muzeja. Katalog vystavki. Leningrad, 1980, p. 14, illus. p. 129). |

| ↟8 | The chant “Let all human flesh be silent…” from the Liturgy of St. Basil of Caesarea (chapter 8) is sung at the Sabbath’s Supper instead of the Cherubim. |

| ↟9 | Antonova, V.I., Mneva, N.E. Katalog drevnerusskoj zhivopisi [GTG]. Vol. 2. Moscow, 1963, No. 373, 623, 829. |

| ↟10 | Exodus, 3:3-5. |

| ↟11 | Weitzmann, K. “The Mosaic in St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai.” Studies in the Arts at Sinai. Princeton, 1982, fig. 9, 14. |

| ↟12 | Kachalova, I.Ja., Majasova, N.A., Schennikova, L.A. Blagoveschenskij sobor Moskovskogo Kremlja. Moscow, 1990, illus. 223. |

| ↟13 | Museums of the Moscow Kremlin, inv. TK-2824 (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, illus. 51). |

| ↟14 | Vystavka drevnerusskogo iskusstva, ustroennaja v 1913 godu v oznamenovaniie 300-letija tsarstvovanija Doma Romanovykh. Moscow, 1913, No. 68. |

| ↟15 | Museums of the Moscow Kremlin, inv. TK-2552; size 51 x 49 cm (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 15, illus. 15). |

| ↟16 | Velikie Minei Chetij, sobrannye vserossijskim metropolitom Markiem. Sentjabr, dni 25-30. St. Petersburg, 1883, stb. 1442-1444. |

| ↟17 | Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej [PSRL], vol. 12, p. 198. |

| ↟18 | Majasova, N.A. “Obraz prepodobnogo Sergija Radonezhskogo v drevnerusskom shit’e (k voprosu ob ikonografii.” Drevnerusskoe iskusstvo. Sergij Radonezhskij i khudozhestvennaja kul’tura Rusi XIV-XV veka. (out for publication); Guseva, E.K. “Osobennosti slozhenija ikonografii ‘Javlenie Bogomateri Sergiju” (lecture given 3 Oct 1992 at Danilov Monastery at the International Scientific Conference “The Venerable Sergij of Radonezh and Traditions of Russian Spirituality”). |

| ↟19 | An altar cross with Sergius erect (Sergiev Posad Museum, inv. 1847) and an altar cross with Sergius on his knees (ibid., inv. 2389); Nikolaeva, T.V. Proizvedenija melkoj plastiki XIII-XVII vekov v sobranii Zagorskogo muzeja. Zagorsk, 1960, No. 155, 157. |

| ↟20 | Trudy VIII Archeologicheskogo s’ezda. Vol. 4. Moscow, 1897, p. 226; unfortunately the location of the podea is today unknown. |

| ↟21 | State Hermitage Museum, inv. E/PT-7976; size 39.5 x 39.5 cm; Kostsova, A., Moiseenko, E. “Dve shitie ikony XV veka.” Soobschenija Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha. Vol. XLII. Leningrad, 1977, pp. 18-21. During restoration at the Hermitage in the 1960s, the background of the piece was “slightly tinted with watermarks, in a color close to that of crimson damask.” The lining is made of blue tulle. The podea has been glued to a silk fabric and plywood (ibid., p. 21, example 7). |

| ↟22 | ”DNS’ BLGOVRNII SVETLO PRAZNUEM OCENJAEMI TVOIM BOGMTI PRISHESTVIEM I K TVOEMU PRCHSTMU VZRAJUSCHE OBRAZU UMILNO GLEM’ POKRY NAS” TSENYM POKROVOM” I IZB’VI H’ OT VSJAKOGO ZLA MOLJASCHI SNA SVOEVO KHRI BA HASHGO SPSTISJA DSHA NASHA.” The inscription comes from the aforementioned book by A. Kostsova and E. Moiseenko, p. 20. |

| ↟23 | State Tretyakovskaya Gallery, inv. 20981, size 62.5 x 100 cm (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 14, illus. 13). The original medieval background (brown brocade) no longer exists; the embroidery is now fixed to coarse blue homespun cloth. The silk embroidery, especially on the faces, has been largely lost The inscription is also very poorly preserved. |

| ↟24 | Lelekova, O.V. “Ikonostas 1497 goda iz Kirillo-Belozerskogo monastyrja.” Pamjatniki kul’tury. Novye Otkritija. Ezhegodnik, 1976. Moscow, 1977, pp. 187-190, illus. on p. 189 (now in the Tretyakovskaya Gallery.) |

| ↟25 | Popov, G.V. Khudozhestvennaja zhizn’ Dmitrova v XV-XVI vekakh. Moscow, 1973, pp. 78-86, illus. 13. |

| ↟26 | Sergiev-Posad Museum, inv. 361; size 55 x 51 cm (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 14, illus. 12). The original background has not survived. During restoration in 1951, the images were transferred from the previous red velvet to dark blue homespun. |

| ↟27 | Antonova, V.I. “O pervonachal’nom meste ‘Troitsy’ Andreja Rubleva.” Materialy i Issledovanija Gos. Tret’jakovskogo galerei. Issue 1. Moscow, 1956, pp. 26-30. |

| ↟28 | Vzdornov, G.I., ed. Troitsa Andreja Rubleva. Antologia. Moscow, 1989, illus. 43, 44, 47. |

| ↟29 | State Russian Museum, inv. DRT-19; size 49 x 51.8 cm: Likhacheva, L.D., ed. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo XV-nachala XVIII veka v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Russkogo muzeja. Katalog vystavki. p. 12, illus. p. 128. This podea is better preserved than the other members of this group, and therefore seems a bit bright and garish by comparison. |

| ↟30 | Nikolaeva, Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva…, p. 62. |

| ↟31 | Opis’ Troitse-Sergieva monastyrja 1641 goda, leaf 96-96 obv. (Sergiev-Posad Museum, inv. 289). |

| ↟32 | Inventory of the Iosif-Volokolamsk Monastery of 1545 (7053). (Georgievskij, V.T. Freski Ferapontova monastyrja. St. Petersburg, 1911, Attached, p. 6. |

| ↟33 | Schekotov, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, p. 13. |

| ↟34 | State Historical Museum, inv. RB-1 (Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 10-11, illus. 5). |

| ↟35 | Nikolaeva, Proizvedenija russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva…, p. 62. |

| ↟36 | PSRL, Vol. 12, p. 202. |

| ↟37 | On the Appearance of the Holy Virgin to St. Sergius podea has St. John Chrysostom depicted in full length on the side border across from St. Nikola; on the Dormition from Vladimir, he is in the center of the upper border. |

| ↟38 | PSRL, Vol. 12, p. 212. |

| ↟39 | On these works: Majasova, Drevnerusskoe shit’jo…, pp. 9, 19-22, illus. 26-31. |