This article by E. Yu. Katasonova is a great overview of medieval Russian goldwork embroidery. It covers mentions of goldwork in the Chronicles, artistic images in frescos and manuscripts, and physical remnants from archeological digs and church treasuries. With over 35 illustrations and pictures, this is a great source for SCA reenactors.

Goldwork Embroidery in Pre-Mongol Rus’ of the 10th-13th centuries

A translation of Катасонова, Е. Ю. “Zolotnoje shit’jo domongolskoj Rusi. X-XIII vv.” Ubrus 4 (2005), 21-45.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

The article in the original Russian can be found here:

http://www.academia.edu/15826687/Золотное_шитье_домонгольской_Руси._Х-XIII_вв

[After I started this translation, I discovered that Mistress Sofya la Rus, mka Lisa Kies, also translated this work on her blog. See her translation here for comparison.]

Elena Yu. Katasonova is a graduate of the Faculty of Philology of the St. Petersburg State University; since 1999 she has been heading the Goldwork embroidery workshop “Ubrus” and the School of Church Embroidery and Goldwork Embroidery at the Uspensky Compound of the Optina Monastery. The article is written on the basis of lectures delivered to students of the School in the second year of study.

Introduction

In Medieval times, goldwork embroidery was in common use throughout Europe, and Medieval Rus’ was no exception. Gold embroidery decorated festive clothing, shoes, horse and military dress, and fabrics in the interiors of religious and secular buildings. Starting in the 10th century, after the official conversion to Christianity, narrative, ecclesiastical embroidery also spread to Rus’. Russian princes built temples and decorated them at their own expense with painting, icons, books, and essential church items, including fabrics and embroideries.

Unfortunately, the specific nature of the material itself, its delicacy and fragility, do not allow us to judge the entire wealth of articles from this oldest period from the history of Russian needlework. Very few examples of embroidery from the 10th-13th centuries have survived, the majority through archeological finds. These are typically fragments of clothing, hats, and shoes found during excavations. Despite this scarcity of material evidence, we can judge the former splendor of examples of artistic embroidery through indirect sources: from written accounts and from surviving depictions in frescoes and miniatures.

1. Evidence from Written Sources

The first mention of goldwork embroidery and precious fabric in Rus’ appears in the ninth century. “Pavoloki“[1]It is unclear from the Chronicles what exactly is meant by the term “pavolok“. It appears that this was initially a general term for all silk fabrics coming to Rus’ from Byzantium. Over time, M. Fekhner suggests, smooth monochromatic fabrics, which formed the bulk of imported silk, were called “pavoloki”, while polychromatic patterned fabric began to be called axamit. (Fekhner, M.V. “Izdelija shjolkotkatskikh masterskikh Visantii v Drevnej Rusi.” Sovetskaja arkheologija, 1977 (3), p. 140) and other luxurious patterned fabrics came to Rus’ as gifts, spoils of war, and as ransom, while Byzantium also tried to limit their purchase by Russian merchants: in a treaty from 945 it is mentioned that “as for the Rus’ … they may not purchase more than 50 zalotniki of pavoloka,” that is, they could only purchase a limited amount[2]Novits’ka, M.O. “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi (Za materialami rozkopok na teritorii URSR).” Arkheologija (XVIII), 1965, p. 25.[3]jeb: A zalotnik is an old Russian unit of weight, equal to about 4 grams or 1/96 of a pound.. While discussing Prince Oleg’s military campaigns “hanging his shield on the gates of Constantinople,” the Primary Russian Chronicle reports that in 907, “Oleg came to Kiev carrying gold, and povoloki, and fruit, and wine, and all kinds of finery.” His successor Igor, who also went on military campaign to Byzantium, in 941 “… having seized gold and pavoloki from the Greek soldiers, turned back and returned to Kiev.” After his death, his wife Olga was baptised in Constantinople. Emperor Constantine “… gave her many gifts: silver and gold, and pavoloki, and various vessels.” It is noteworthy that in the Chronicle, pavoloki are mentioned alongside gold, speaking to their special value. The same Chronicle contains a tale in 971 which is curious in this sense: “during the prolonged siege of Constantinople, the Greek ambassadors came to Sviatoslav, bringing him ‘gold and pavoloki‘ as gifts. The prince remained unmoved, and without looking, told them to take these away. But when they brought him a sword, Sviatoslav began to praise, professing his love and gratitude to the emperor. And the Greeks decided, ‘This man will be fierce, for he neglects wealth, but takes a weapon.'” After that, a peace treaty was concluded with the Greeks, and they pledged to pay tribute to Rus’. In this story, pavoloki, along with gold, appear as a symbol of wealth and treasure. A different Sviatoslav, demonstrating his treasures to the German ambassadors in 1075, showed them, along with “an abundance of gold and silver,” also pavoloki[4]Cited by Novtks’ka, “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi,” p. 25-26..

Precious embroideries also came to Rus’ by the same route. The chronicles contain evidence of the distribution of embroidery to Rus’ dating from the 11th century. Embroidery was even exported beyond Rus’ borders: in the records of Ksilurgu Monastery on Mt. Athos, Russian contributions are mentioned in 1143: “one gold Russian epitrachelion; the hand of the Blessed Mother is Russian with a gold border, surrounded by a cross and two doves; and also two purple mandylia [ruchniki], one with decoration for hanging, and the other ancient Russian”[5]Kondakov, N.P. O nauchnykh zadachakh istorii drevnerusskogo iskusstva. St. Petersburg, 1899, p. 91; cited by Noviks’ka, “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi,” p. 26..

Unfortunately, time has not preserved documentary evidence of the makeup of goldwork embroidery workshops in Rus’ during this oldest time period. The chronicles bring us only mention their existence, as well as the names of several persons in the Grand Prince’s family who were engaged in embroidery. For example, it is known that Vladimir Monomakh’s sister, Anna Vsevolodovna (Yanka), the first of the Russian princesses to become a nun, having become a member of the Andreevskaja monastery founded by her father, opened a school there in 1086 where young girls studied gold and silver embroidery[6]Odobesko, A.I. Vozdukh c vyshitym izobrazheniem Polozhenija Spasitelja vo grob. Drevnosti. TMAO, vol. 4, iss. 1, 1874, p. 7.. At the beginning of the 13th century, a different Anna Vevolodovna, wife of Kiev’s Prince Ryurik Rostislavovich, embroidered for her own family, as well as to decorate churches: “I committed myself to labor and needlework in gold and silver, both for myself and my children, and more so for the Vydubitskij monastery”[7]Tatischev, V.I. Istorija Rossijskaja s samykh drevnejshikh vremen. Book 3. St. Petersburg, 1774, p. 329..

In Rus’, embroidery workshops existed both in monasteries, as well as in the palaces of the Great and other princes. It is well known that while building and decorating churches and monasteries, the princes of Rus’ supplied them with everything essential for worship: veils [pokrovtsy], curtains [zavesy], liturgical gowns [inditii, per Lunt, “Concise Dictionary of Old Russian:” “prestol’naja odezhda“], and so forth. During the construction of Kiev’s St. Sophia Cathedral in 1037, Prince Yaroslav the Wise, according to the Chronicle, “decorated with with every kind of beauty, with gold and precious stones, and with pavoloki.” In 1231, Rostov’s Bishop Kirill “decorated the Cathedral of the Holy Virgin with precious icons, with their power and stories, and hung podeai, that is, peleny, causing the shrine [kivot, “ark”] to be highly valuable, and the valuable liturgical gowns also, and on the table [trjapeza] vessels and fans [ripidi], and a multitude of every pattern…”[8]Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej, vol. 1, Moscow, 1962, p. 458 (cited by: Putsko, V.G. “Pamjatniki russkogo prikladnogo iskusstva XV-XVII vekov v Rostovskom muzee.” Muzej prmen’ene umetnosti. Zbornik 24-25. Beograd, 1980/1981. p. 52.). In the chronicle for 1288 are enumerated the many contributions of Grand Prince Vladimir Vasil’evich to various churches “curtains embroidered in gold” (in Vladimir), “aksamite robes [plattsy] decorated with gold and pearls” (in Ljubomila), and “all liturgical clothes embroidered in gold”[9]Cited by: Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 42; Novits’ka, M.O. “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi (Za materialami rozkopok na teritorii URSR).” Arkheologija (XVIII), 1965, p. 26..

Goldwork was used not only to decorate ecclesiastical items, but also served as a singular sign of belonging to the upper class: in 1216 before the Battle of Lipoveskaja, Prince Jaroslav Vsevolodovich told his warriors: “If his shoulder is decorated with gold, kill him!”[10]PSRL, vol. 1, iss. 3, St. Petersburg, 1843, p. 445.. Prince of Galicia Daniil Romanovich wore “boots of green leather, embroidered with gold”[11]PSRL, vol. 1, iss. 3, St. Petersburg, 1843, p. 147, cited by Cited by: Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 43.. It is natural to assume that these items were produced in well-lit towers of the the Grand Princes, under the guidance of the mistress of the house, such as was seen in later periods from which far more sources still survive. Following the example of the Grand Princesses, similar workshops were also created by other representatives of the feudal nobility.

The majority of Chronicle references to examples of embroidery are tied to their loss. In a time of fires, internecine wars, pillage and hostile invasions, the precious heritage of Kievan Rus’ was irrevocably lost. Russian princes perished in gory internecine discord, and cities and villages burned. During the destruction of Putivl’ by Jacheslav in 1046, “liturgical gowns” and “official robes, all decorated with gold” were destroyed[12]Cited by : Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 42.. In 1202, during the battle outside the capital, Kiev, between Rjurik Rostislavovich and Roman Mstislavovich of Galicia, “a great evil occurred … not only was Podil captured, but they also ransacked the metropolitan St. Sophia, the Church of the Tithes of the Blessed Virgin, and all monasteries, and they ripped the rizas off of the icons … and the priceless robes of the first Princes which hung in the churches in their memory – those too were carried away.” This manuscript testimony is also interesting in that contains an ancient Byzantine custom reflected in Rus’: in the churches there hung many secular items of clothing, donated by the princes “to remember me by.”

It is possible that the Oration in the Hypatian Codex is discussing exactly such “memorable contributions”, when under 1183 it talks about the great fire in Vladimir. Nearly the entire city burned, along with 32 churches, including the only just completed “Gold-Domed” Cathedral of the Assumption with a great number of “patterned fabrics” [yzorochij] in her sacristy[13]About the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Holy Mother, built and decorated by Andrej Bogoljubskij in 1158, the chronicler writes: “In the summer of 6666, the Christ-loving Prince Andrej, likening himself to King Solomon, dedicated [dospe] a stone cathedral to the Blessed Holy Mother, and to Saint Velma, and gilded its five domes, and created three golden church doors, decorated with many valuable ornaments of precious stones and pearls, and with all sorts of patterns, and in all ways as wondrous and astonishing as Solomon’s Holy of Holies.” (Cited by Ljubavskij, M. Lektsii po drevnej russkoj istorii do kontsa XVI veka. St. Petersburg, 2002, p. 216-217). The chronicle says that the number of lost embroideries was “innumerable.” There burned “countless cloths embroidered with gold and pearls, which would hang in two streams on holidays from the golden gates to the Church of the Virgin Mary, and from thence to the “leader’s shadow” in two streams”[14]Cited by: Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 43.. According to some researchers (V.T. Georgievskij, M.A. Novitskaja), this means the golden gate of Vladimir, which was located more than a kilometer from the Cathedral of the Assumption; the “leader’s shadow” (they suggest) probably refers to the now-unpreserved bishop’s palace, which was presumably not far from the cathedral[15]Georgievskij, V.T. “Drevnerusskoe shit’jo v riznitse Troitse-Sergievoj lavry.” Svetil’nik, 1914 no. 11-12, p. 4.. A more plausible interpretation is that of N.N. Voronin, who proposed that the manuscript has in mind the northern “golden gates” and the southern doors of the cathedral, and that the “leader’s shadow” refers to the bishop’s palace: “… on the holiday of the Assumption of the Virgin, the southern and northern “golden gate” cathedral doors were opened, and the precious vestments and fabrics of the cathedral vestry would hang between them in two ‘verses of the people.’ Along this ‘corridor,’ issuing forth from the cathedral amongst brightly colored silken fabrics blowing in the breeze, a stream of pilgrims would stream to worship the icon”[16]Voronin, N.N. Vladimir, Bogoljubovo, Suzdal’, Jur’ev-Pol’skoj. Moscow, 1965, p. 47..

Fires were common occurrences in wooden medieval Rus’, and constant civil strife was devastating, but nothing could compare to the calamity that befell Rus’ during the years of the Mongol yoke. “In that year (1223),” the chronicles report, “there came a people about whom no one knows for sure — who they are, where they came from, or what language they speak, or their faith or tribe. And they are called Tatars, while others are called the Taumeni, and a third group are the Pechenegs”[17]Pamjatniki literatury Drevnej Rusi. XIII v. p. 132.. The Mongol-Tatar invasion brought Rus’ innumerable disasters. Almost all major cities were burned, destroyed and looted. Masonry construction ceased, and industry, the production of chronicles, and cultural life all came to a halt. During the pogroms of 1237-1240, an enormous number of churches were burned or looted by the Tatars. During the capture of Kiev by the Tatars in 1240, the chronicle notes: “that summer, Kiev was seized by the Tatars and St. Sophia was looted, and all the monasteries and icons and the fair crosses and all church decor were taken…”. Kiev was unable to recover after this defeat. Aleksandr Nevskij, having received the fief to the Kievan principality, did not actually go there, and didn’t even bother to send a deputy. There were no Russian princes in Kiev in the second half of the 13th century, and it was ruled instead by the Tatar basqaqs. The transfer of the metropolitan capital from Kiev to Vladimir-Zalessky underscores this complete downfall of “the mother of all Russian cities.” “Around 1300,” says the chronicler, “Metropolitan Maksim, unable to endure the Tatar violence, moved to Vladimir with his entire household. At that same time, Kiev completely fell to pieces”[18]Ljubavskij, M. Lektsii po drevnej russkoj istorii do kontsa XVI veka. St. Petersburg, 2002, p. 240.. It is not surprising that examples of embroidery from the Kievan period have not survived to today. They simply were unable to survive for objective reasons.

“Manuscripts paint a picture of uninterrupted Tatar raids [“ratej“} throughout the entire last quarter of the 13th century. Over 20-25 years, the Tatars undertook significant raids against northeastern Rus’ 14 times… the lands of Vladimir and Suzdal were devastated by the Tatars 5 times in those years… Vladimir, Suzdal, Jur’ev, Perejaslaval’, Kolomna, Moscow, Mozhajsk, Dimitrov, Tver’, Rjazan’, Kursk, Murom, Torzhok, Bezhetsk, and Vologda suffered greatly from numerous Tatar raids in the second half of the 13th century”[19]Kargalov, V.V. Vneshnepoliticheskie faktory razvitija feodal’noj Rusi. Moscow, 1968, p. 171.. In 1281, Aleksandr Nevskij’s son Andrei, fighting against his brother Dmitri for the Great Prince’s throne, brought Tatar troops to Rus’, and “… the Tatars devastated cities and regions, villages and churchyards, and looted the churches and monasteries — they plundered the icons, and crosses, and the sacred vessels, and podeae, and books, and all of the riches. And thus also near Rostov, and around Torzhok, and around Tver’ they devastated everything all the way to Torzhok…”[20]”Moskovskij letopisnyj svod kontsa XV veka.” PSRL, vol. 25, Moscow-Leningrad, 1949, p. 153.. The interior regions of northeastern Rus’ were ravaged not only by the struggle between Aleksandr Nevskij’s sons, but also in the first quarter of the 14th century during fighting between Moscow and Tver’.

In addition to these written sources recalling examples of embroidery and valuable fabrics, we can also get some insight about them through preserved artistic depictions.

2. Artistic Representations

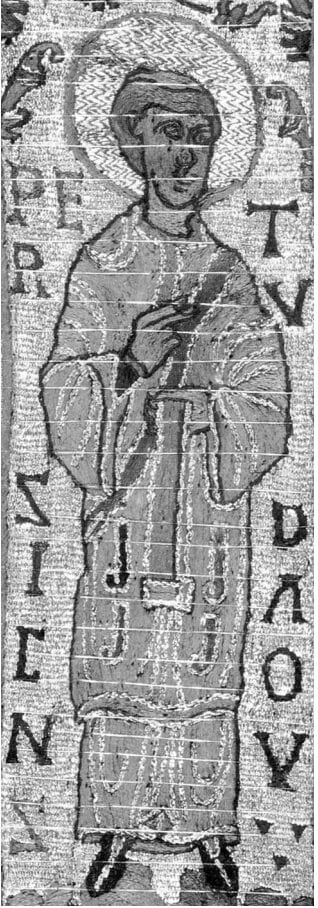

Portraits of the Grand Princes and their families in preserved monumental paintings and in manuscript miniatures give an idea of the ornamentation of royal ceremonial clothing: they were sewn from expensive fabrics, and their shoulders, hems, wrist lines and belts were richly decorated with gold, pearls and precious stones. A portrait of Yaroslav Izjaslavovich can be seen in the Egbert Psalter[21]Lazarev, V.N. “Iskusstvo srednevokovoj Rusi i Zapad.” XIII Mezhdunar. kongress istor. nauk, Moscow, 1970, p. 29-31..

In the frescos of Kiev’s St. Sophia, build in 1037 by Jaroslav the Wise, there remains a founder portrait [ktetor] composition depicting the family of the Great Prince (illus. 1)[22]Lazarev, V.N. “Gruppovoj portret semejstva Jaroslava.” Russkaja srednevekovaja zhivopis’. Moscow, 1970, p. 27-54.. A close analogy of the royal family’s clothing is found in the inventory of female burials located near the foundation of the Church of St. Michael in Chernigov (12th cent.). The inventory states that on their chests there were “scraps of silk fabric, woven with gold, decorated with narrow gold braid [pozument, aka, gimp] with embellishments of small metal plaques, some decorated with green and gold pieces of glass.” The hem was also decorated with plaques: “… metal plaques in the form of a cross, heart-shaped plaques inset with gold and green glass, circles, squares, triangles, and semi-circles with and without inset of tiny carnelian cabochons.” While sifting the earth, two small pearls were found. In the crypt of the Church of the Tithes, fragments of cloth were also found decorated with plaques and pearls[23]Cited by: Novits’ka, M.O. “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi (Za materialami rozkopok na teritorii URSR).” Arkheologija (XVIII), 1965, p. 28..

[jeb: Color version found online here.]

In a 12th century fresco in the Savior Church on the Nereditsa near Novgorod, an image of Prince Yaroslav of Novgorod has been preserved (illus. 2). His cloak (coat) of expensive, large-patterned fabric is decorated around the edge with a gold braid.

[jeb: Color version found online here.]

But, of course, the most interesting examples for our study are fragments of medieval Russian embroidery which found in archeological digs. In our modern day, it is they that allow us to accurately restore the technical particulars of gold embroidery from the pre-Mongol period.

3. Physical Examples

In addition to the previously mentioned indirect examples, there is a small collection of embroidery examples which have survived to modern times from the medieval period of embroidery in Rus’. With the exception of a few preserved examples of ecclesiastical embroidery [litsevoe shit’jo, literally, “facial embroidery”], these are for the most part examples of ornamental embroidery that decorated female ceremonial clothing. This is due to the fact that the majority of archeological finds were of burial sites (plus a few early-Medieval treasure caches). It’s not always understood from what part of the clothing a preserved fragment of embroidery may have come. Archeological expeditions have reported collars, belts, bands of trim, headbands, the edging of various articles of clothing, lapels, and chest ornaments. The composition of the ornament is always tied to the shape and size of the where on the clothes the embroidery was located. The particular value of these preserved examples is directly proportional to their small quantity. Often, the original researchers did not distinguish an embroidered design from one that was woven, and in many sources, the oldest examples of embroidery are called brocade, or braid, or golden bands or fabric[24]Novits’ka, M.O. “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi (Za materialami rozkopok na teritorii URSR).” Arkheologija (XVIII), 1965, p. 24..

A significant number of pre-Mongolian embroidered items known today are kept in the archives of the State Historical Museum [GIM]. These are fabrics of archeological origin from the Kiev, Chernigov, Vladimir-Suzdal, Rjazan’, Smolensk and Novgorod regions. Traces of medieval embroidery are found on 51 out of 80 fragments in the collection. In addition to the collection in the State Historical Museum, fragments of medieval needlework are also preserved in the Hermitage, and the museums of Kiev, Chernigov, Lviv, Chersonus, Novgorod, and other cities.

From more than 50 examples found in Ukraine, two thirds originate from Kiev itself and the surrounding area, and only one third from other areas[25]idem., p. 27.. Fragments of 20 embroidered items were found in Kiev proper. They came from a cache in the Mikhajlovskij Monastery, from the crypt of the Church of the Tithes where Kievans perished during Batu’s Invasion of 1237, and from graves near the Church of the Tithes and in St. Sophia.

There is a widely-held belief that goldwork embroidery was exclusively developed among the highest circles of feudal society. However, samples of medieval needlework are found even in graves of the rural population, especially that of women. “Out of 53 examples of embroidery with remnants of gold embroidery, only 16 fragments come from treasure caches and the princely burial sites of Kiev, Chernigov, Smolenski and Old Ryazan’; the remaining 37 embroidered items were found in village mounds from various regions of Eastern Europe. The latter were undoubtedly created by the peasants themselves. They astound the viewer with their subtlety of execution, variety of motifs, and the succinctness and elegance of their design”[26]Fekhner, M.V. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi.” Pamjatniki kul’tury. Novye otkrytija [PKNO], 1978. Leningrad, 1979, p. 402.. Due to their high cost, the rural population would use gold fabric only to decorate festive costumes. Goldwork on silk decorated shoulders, collars, cuffs, headbands, and other areas of clothing. Most often, the Byzantine and oriental fabrics that were used were predominantly red in color (in our time, their long stay in the ground has turned them to a greyish-brown). They brought not only fabric, but also gold and silk threads from Byzantium. It is known that in Byzantium and Spain, they used threads with gold wrapped around a silken core; in the East, they used a linen base thread, which survived more poorly underground[27]Fekhner, M.V. “Shjolkovye tkani kak istochnik dlja izuchenija ekonomicheskikh svjazej Drevnej Rusi.” Istorija kul’tury Vostochnoj Evropy po arkheolchicheskim dannym. Moscow, 1971, p. 215..

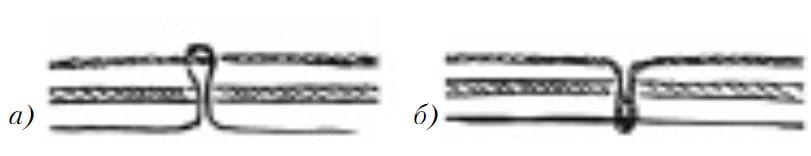

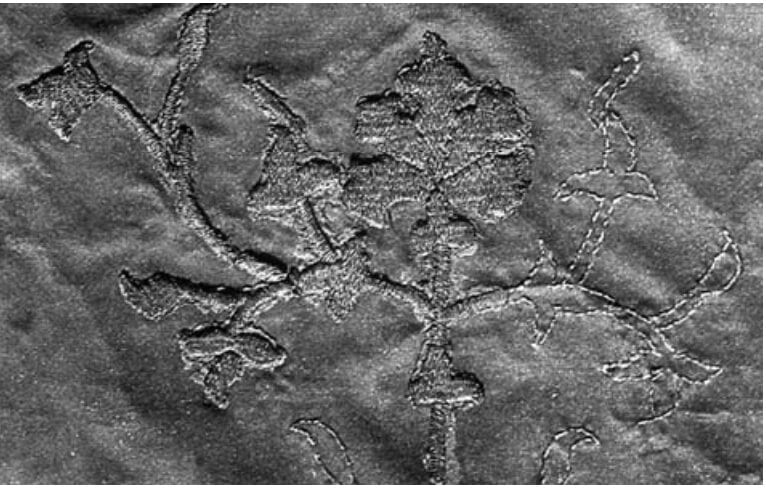

The embroidery technique has been studied in detail and minutely described by M.A. Novitskaja. The majority of preserved embroideries are carried out with embroidery styles called “canvas work” [v prokol, literally, “by piercing”] and passing the gold through the fabric [na projom, literally, “at the opening”]. “The peculiarity of the latter lies in how the metallic threads, either drawn or twisted, are attached to the fabric. On the front side stitches about 7mm are made, and on the reverse – stitches of almost the same length. On the front, the new row lies immediately next to the previous, one after another, with each stitch beginning in the middle of the previous one. Thus, they obtained surfaces that were solid, as if forged (illus. 3). The effect of the metallic luster and the play of light was accentuated by embroidery stitches in different directions: the craftswoman placed them parallel to each other, or now along a curve, following the outline of the design — sewing with the design [‘shov po forme’]; for stems and narrow strips, they often would use a herringbone stitch [shov ‘v elochku’] (illus. 4). Enriched color combinations were achieved by the artist completely filling in the areas of the design, leaving the areas around the design unembroidered”[28]Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 44.. A downside of this technique is that it is difficult to pass the golden threads through the fabric without damaging them. It is possible that tiny holes were first made in the fabric using awls such as those found in the graves at Chernaya Mogila (made from bronze and bone)[29]Fekhner, M.V. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi.” PKNO, 1978. Leningrad, 1979, p. 403..

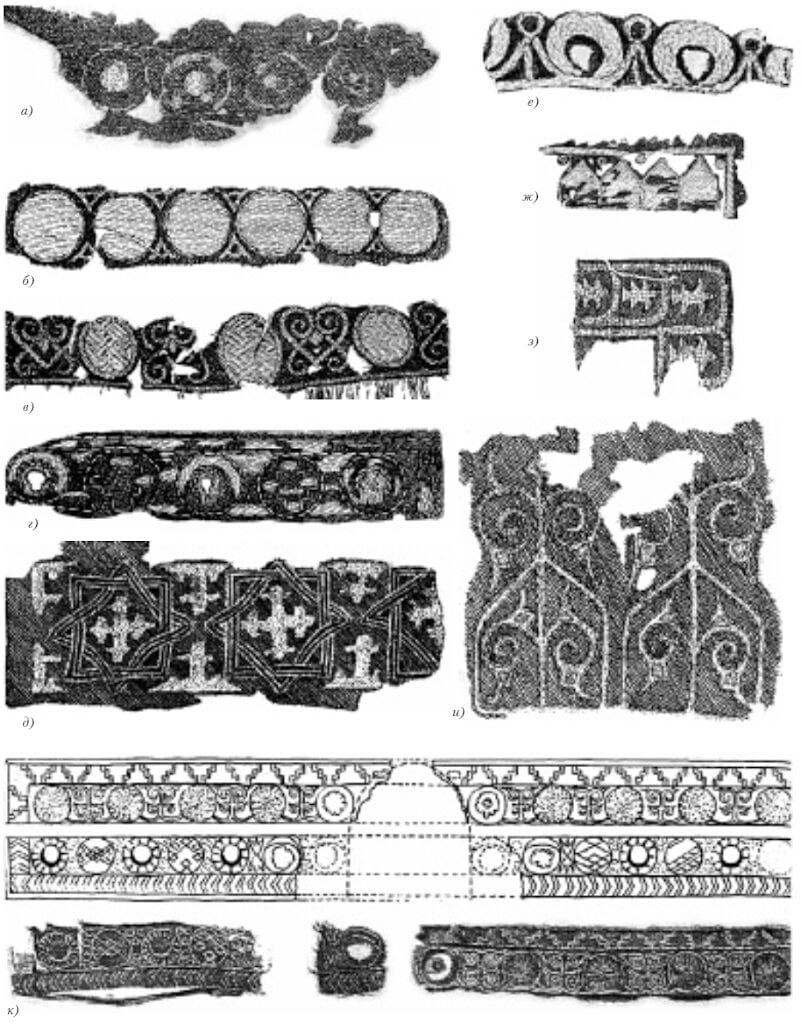

The ornamentation found in these early embroideries are characteristic of their time and find counterparts in other forms of decorative and applied art: in bone and wood carvings, in stone carvings, metal castings, and illuminated miniatures. In the words of J. Evans, diving into the details of ornament, one can “get a keen impression of the time…”[30]Evans, J. Style in Ornament. London, 1950, p. 3.. In modern science, the study of ornament has received a great deal of attention. M.A. Orlova calls it “the handwriting of that time,” “formulaically succinct, and the most accurate and distinct expression of a particular style”[31]Orlova, M.A. Ornament v monumental’noj zhivopisi Drevnej Rusi: Konets XIII-nachalo XIV v. Ch 1. Moscow, 2004, P. 5.. Questions of analogies and the stylistic uniqueness of ornament of the epoch in question are in one way or another raised by the majority of articles devoted to medieval embroideries, and we will not touch upon them here. We will note only that materials at hand — textiles: patterned silk fabric or woven bands — served as the closest analogy and, most likely, the source of motifs in medieval embroidery. The latter are often found in archeological digs[32]Silk and gold ribbon make up half the collection of archeological fabrics in the State Historical Museum – in all, 68 examples. (see Fekhner, M.V. “Shjolkovye tkani kak istochnik dlja izuchenija ekonomicheskikh svyazej Drevnej Rusi.” Istoria kyl’tury Vostochnoj Evropy po arkheologicheskim dannym. Moscow, 1971, p. 214.) Most commonly seen are bands with geometric patterns: braids, zigzags, diagonal lines, diamonds; less often seen are bands with floral and zoomorphic motifs, and also with the images of saints.. Such woven bands, both silken and golden, decorated collars, headbands, and the edges of sleeves in medieval times – that is, both sewing and needlework emphasized the same areas. A significant number of archeological finds attest to the fact that ornamentation on clothes frequently consisted of two types: narrow strips of relatively simple design outlined the main embroidered area of a collar or other area of the item of clothing. In illustrations 4, 6г[33]jeb: Note that I left the image references using the Russian letter, to match the letter in the image., and 14, we see the main embroidery outlined in gold braid; in illustrations 6б, 6ж, 6з, 7и, 7к and 8а both parts of the design are embroidered.

а – fragment of standing collar from a burial at village of Khreple, Novgorod region, 12th c;

б – fragment of standing collar from a burial at village of Karash, Yaroslav region, 11-12th c.

в – fragment, standing collar, burial mound, village of Maklakovo, Rjazan’ region, late 12th-early 13th c.

г – fragment, standing collar, burial mound, village of Kubaevo, Vladimir region, 11-12th c.

д – fragment of a collar, village of Karash, 11-12th c.

е – fragment of embroidery found near the village of Osipovtsy, Vladimir region, 11-12th c.

ж – fragment of a collar, village of Maklakovo, late 12th-early 13th c.

з – fragment of clasped collar from mass grave in Staraja Rjazan’, first half of the 13th c.

и – clothing fragment from the Mikhajlovskij monastery crypt, late 12th-early 13th c.

к – headband from burial under the Cathedral of the Assumption in the Moscow Kremlin, drawing and two fragments, second half of the 12th c.

In embroidery of the 10-13th centuries, we find different types of geometric, floral, and zoomorphic designs or combinations thereof. This type of embroidered ornamentation always has a neat and clear rhythm. Geometric ornamentation is found most frequently. We find goldwork in the form of circles in grave finds from the Rajki settlement near Berdichev[34]Goncharov, V.K. Rajkovetsnoe gorodische. Table XXIX, 3. Kiev, 1950., in embroidery from the crypt of the Church of the Tithes[35]Karger, M.K. Arkheologicheskie issledovannija drevnego Kieva. Kiev, 1950, p. 130, figure 95., on collar fragments from the burial mound near Karash in the Yaroslav region (illus. 5ж), and from female burials in the Pskov region[36]Zapiski Russkogo Arkheologichekogo obschestva, Vol. 5, No. 1. St. Petersburg, 1903, p. 51; Pskovskij muzej-zapovednik, inventory number 2634..

The ornament of a fragment of collar (12 cent.) found near Khreple in the Novgorod region consisted of red silk with circles completely embroidered with gold (illus. 5а). Today, only fragments of this embroidery remain. There are also ornamentation consisting of triangles, rings, rosettes, crosses, and stripes.

Several fragments of rich headbands were found in female burials under the Cathedral of the Assumption in the Moscow Kremlin, made from 2 embroidered bands of green and red. The upper band, 3cm wide, is framed with a geometric stepped pattern on top; the central section is formed by circles ringed in gold divided by treelike motifs with branches curving downward. In structure, this part is similar to a late 12th-early 13th century collar from the burial mound near Maklakovo in the Rjazan’ area (illus. 5в) and the “tree of life” from the Mikhali collar (illus. 9a). The design of the lower band is also two-part: circles with alternating images of lunnitsas and geometric motifs, and below, a strip of double chevrons. The center of the headband was decorated with a diadem[37]Sheljapina, N.S. Arkheologicheskie issledovanija v Uspenskom sobore. MMK. Materialy i issledovanija. No. 1, Moscow, 1973, p. 57-58. and small pearls.

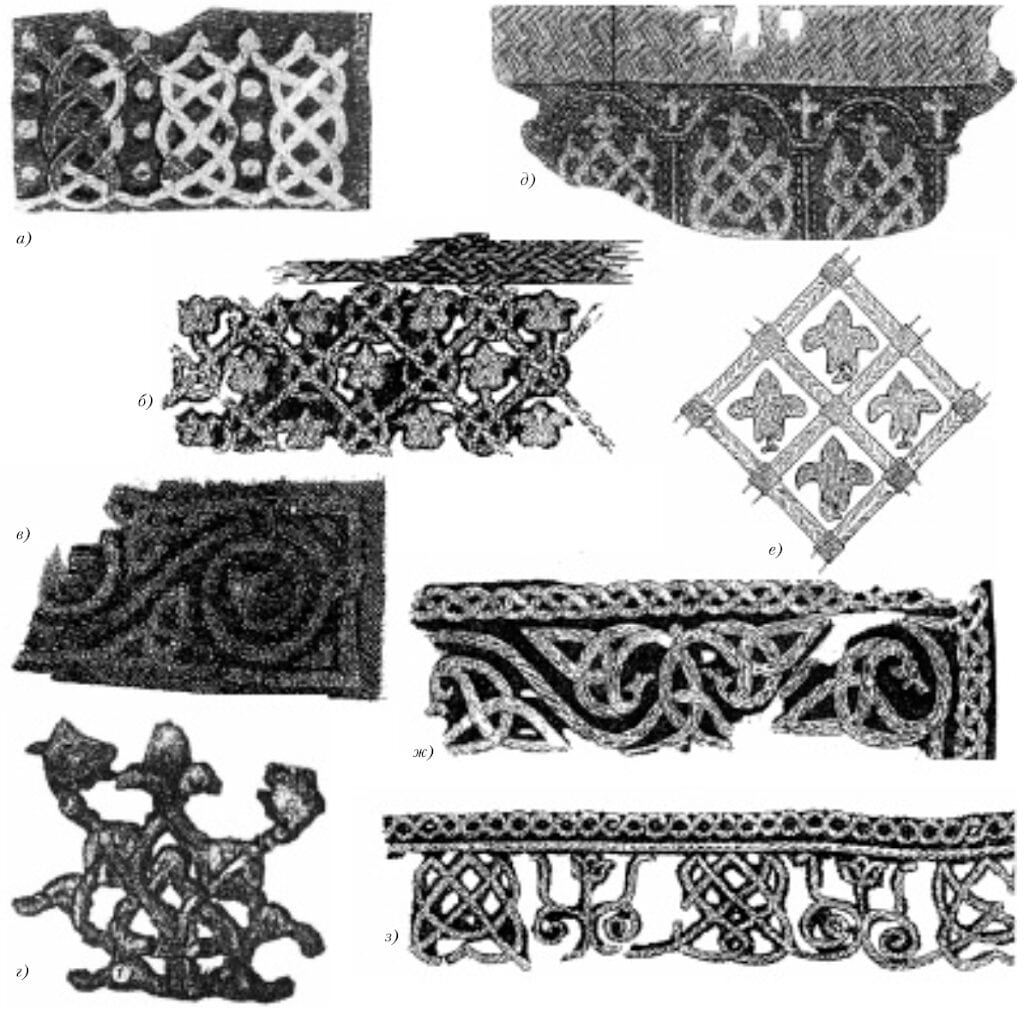

A frequent motif are all kinds of braids — these are a type of geometric ornament, but can be decorated with floral elements: stylized leaves, shoots, lilies, and can also be combined with zoomorphic motifs. A collar from burial clothes was decorated with braid in Vasil’ki near Vladimir (illus. 6a), dated to the 11th-12th century. More complex braids are seen in combination with lily-shaped ends on a 12th century sewn collar from the Ivankov region (illus. 6д). Notable patterns of braidwork were placed on embroidered 11-12th century collars from the burial mound of Karash in the Yaroslav region (illus. 6ж), having a lot in common with a morocco-leather wallet (late 12th-early 13th cent.) found in a burial mound near Anis’kino in the Moscow region (braids ending in animal heads, illus. 6в), as well as a fragment of a 12th century standing collar from an excavation near Staraja Rjazan’ (illus. 6з).

Stylized floral ornaments, found less commonly, are typically of triangular or heart-shaped leaves, lilies, and vines of various forms. It is often difficult to to classify a particular ornament, as in many cases, we are dealing with a combination of multiple elements into a single pattern: a braid, leaves, lilies, circles, triangles, et.al. One of the most commonly encountered elements is the stylized “tree of life”, a motif that goes back to deep antiquity. We can see this on an embroidery from the 11-12th century from Shargorod[38]KGIM No. V-2651. Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, Table III, image 13., and also on a 12th-13th century embroidery from a burial near Churkin, Nizhnij Novgorod region[39]Spitsyn, A. “Churkinskij mogil’nik.” Zapiski otd. russkoj i slavjanskoj arkheologii IRAO. Vol 5, No. 1, image 38..

а – fragment of a collar from a burial mound near Vasilki, Vladimir region, 11th-12th c.

б – fragment of a collar from a tomb at the Church of St. John the Divine, Smolensk, late 12th-early 13th c.

в – morocco-leather wallet from a burial mound near Anis’kino, Moscow region, late 12th-early 13th c.

г – fragment of a pectoral embroidery from Belgorod, 11th-12th c.

д – fragment of a collar from a burial near Antonovo, Ivanov region, 12th c.

е – fragment of embroidery from Romashki, near Kiev, 11th c.

ж – fragment of a collar from a burial mound near Karash, Yaroslav region, 11th-12th c.

з – fragment of a standing collar from Staraja Rjazan’, 12th c.

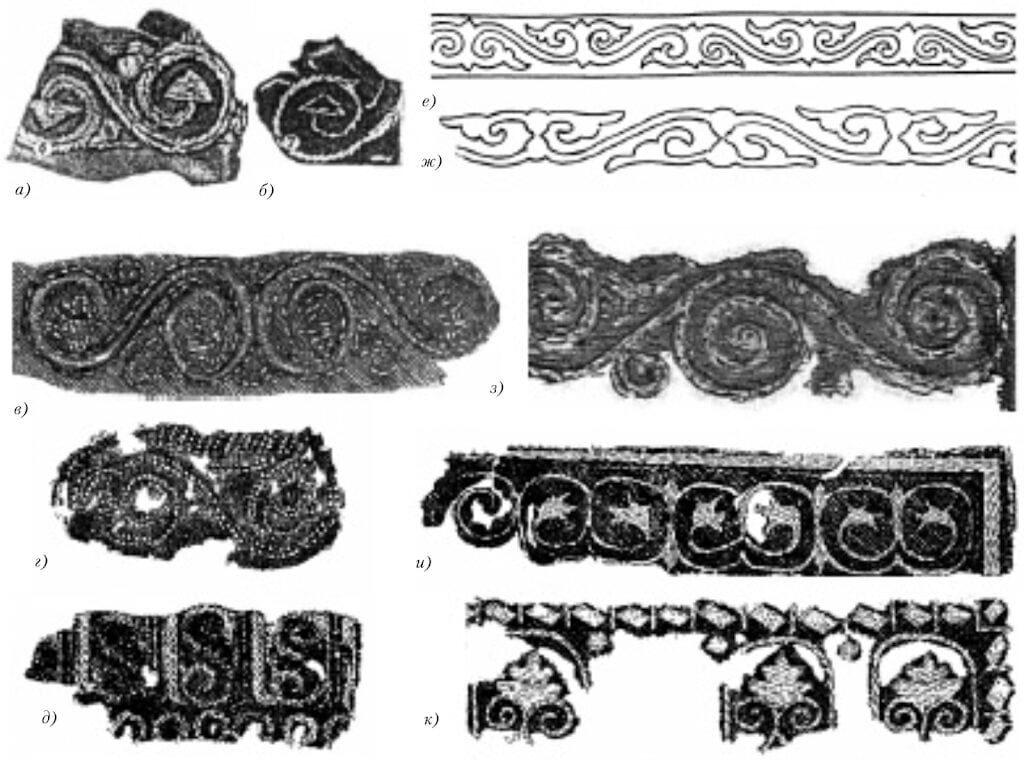

A stylized floral ornament decorates a woman’s headband found during the 1941 excavation in Starij Galich, where the grave of a 12th century young woman was found near the sarcophagus of [Yaroslav] Osmomysl. The embroidery style is a smoothly curling stem, from which paired symmetrical tendrils split off above and below (illus. 7e). Almost the same design is seen on a different headband found in the crypt of the Mikhajlovskij Monastery in Kiev (illus. 7ж), which is also decorated with metallic plaques and small pearls.

а, б – fragments of embroidery from the crypt of the Church of the Tithes, Kiev

в – embroidery from the burial mound near the village of Kubaevo, Vladimir region

г – fragment of a collar from a burial mound near the village of Kir’janovo, Yaroslav region, 11th c.

д – fragment of a headband from a child’s grave near Boldina Gora, Chernigov region, 11th c.

е – fragment of a headband from Starij Galich, 12th c.

ж – headband from the crypt of the Mikhajlovskij Monastery, Kiev

з – fragment of embroidery from a tomb under the Cathedral of the Assumption, Moscow Kremlin, 13th c.

и – fragment of a standing collar from the Nizhnij Novgorod region, 12th c.

к – fragment of a standing collar from the village of Kulebovo, Vladimir region, 11th c.

On two fragments from the crypt of the Church of the Tithes (illus. 7а, б), we see a composition of plant motifs and vines characteristic of that era. Similar elements date from the 13th century, coming from a tomb under Church of the Assumption in the Moscow Kremlin (illus 7з) and from the necropolis in the northern fortification in Starij Rjazan'[40]Mongajt, A.L. “Staraja Rjazan’.” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii, 1955, No. 49, p. 171, image 133.. One of these (the Kremlin burial) is a serpentine stem with beautifully curling shoots branching off from it. The ornament of the embroidery from the village of Kubaevo, Vladimir region (illus. 7в) and the village of Kir’janovo in the Yaroslavl region (illus. 7г) consists of s-shaped curls, arranged in pairs and supplemented with other small elements. These designs can be interpreted as either geometric, or as highly-stylized plants. Ornament from the 11th century from the Trinity burial mound on Mt. Boldino, Chernihiv region, using the same design (vertical S-shaped curls surrounded by rectangles supplemented below with small rings) would rather be classified as geometric (illus. 7д)[41]Analogies of this ornament are presented in Fekhner, M.V. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Vladimiro-Suzdal’skoj Rusi.” p. 224-225..

An embroidery from Nizhnij Novgorod is composed of closed vegetative curls and a wide strip going along the edge of the collar. M.V. Fekhner dates this embroidery, which is couched on fine silk, to the 12th century (illus. 7и)[42]Fekhner, M.V. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi.” PKNO, 1978. Leningrad, 1979, p. 404.. A strip of birch bark was sewn into the collar as a stiffener.

Fragments of embroidery from the village of Romashki in the Kiev region[43]Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 47. are formed of diamonds forming a grid filled with lilies (illus. 6е). This embroidery decorated a wide area, not just a narrow strip; a strip of birch bark was placed beneath it as a stiffener, from which it is possible to conclude that it was a breast decoration. It has elements in common with a fragment of a collar found in the late 12th-early 13th century tomb in the Church of St. John the Theologian in Smolensk (illus. 6б)[44]Fekhner, M.V. “Drevnerusskoe zolotnoe shit’jo X-XIII vv. v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Istoricheskogo muzeja.” Srednevekovye drevnosti Vostochnoj Evropy. Trudy GIM. No. 82. Moscow, 1993, p. 8-9; Ignashina, E.V. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe i ornamental’noe shit’jo v cobranii Novgorodskogo muzeja: Katalog. Veliky Novgorod, 2003, p. 24, catalog number 1a., decorated with diamonds filled with lilies. These same lilies enclosed in a grid also decorate an embroidery from Starij Rjazan'[45]Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, Table I, image 5..

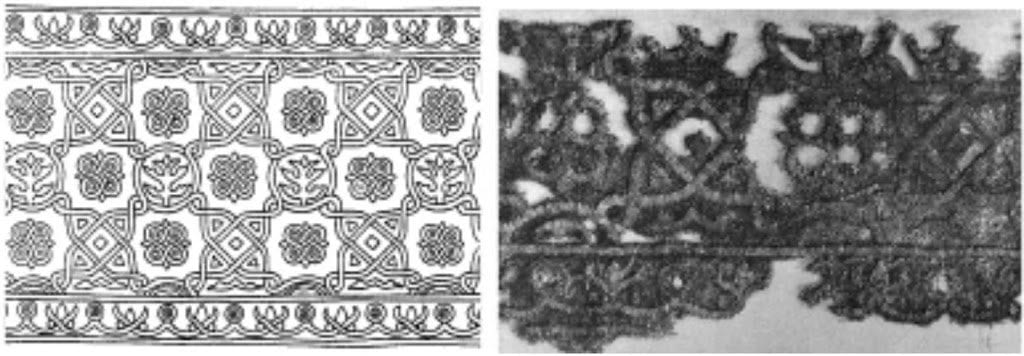

Ornamental embroidery is often similar to silk fabrics in its design and pattern. For example, the pattern of an embroidered collar from a burial mound near the village of Kubaevo (illus. 10) and needlework from Staroe Bykovo in the Vladimir region[46]Fekhner, M.V. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Vladimiro-Suzdal’skoj Rusi.” Srednevekovaja Rus’. Moscow, 1976, p. 224., consisting of heart-shaped figures, practically mirror by design Byzantine fabric from the 12th century in the Kestner Museum in Hannover[47]Gronwoldt R. Webereien und Stickereien des Mittelalters. Hannover, 1964. p. 134. Table 33.. This design has elements in common with a wrist cuff found in a burial in Novgorod’s St. Sophia (illus. 8) and the belt of Prince Vladimir (1020-1052), older son of Yaroslav the Wise. The sleeve cuff stored in the Novgorod museum is decorated with well-preserved embroidery on faded red silk fabric. Some researchers interpret its design as “the Tree of Life”[48]NIAKhMZ [Novgorodskij istoriko-arkhitekturnyj i khudozhestvennyj muzej-zapovednik], no. 3799, Katalog VI vystavki proizvendenij izobrazitel’hogo iskusstva, restavrirovannykh v GTsKhNRM. Moscow, 1969, p. 129. Ignashina, E.V. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe i ornamental’noe shit’jo v cobranii Novgorodskogo muzeja: Katalog. Velikij Novgorod, 2003, p. 78, no. 49.. It’s interesting to note that this embroidery repeats the design of the patterned Byzantine fabric from which the Prince’s belt was sewn. It is possible to see several analogies to this on collars from graves in the village of Maklakovo in the Rjazan’ province[49]Fekhner, M.V. “Drevnerusskoe zolotnoe shit’jo X-XIII vv. v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Istoricheskogo muzeja.[GIM]” Srednevekovye drevnosti Vostochnoj Evropy. Trudy GIM. No. 82. Moscow, 1993, Catalog number 39, illustration on page 11. and the village of Mikhali near Suzdal’. The latter preserved only the outlines of two “trees”[50]Saburova, M.A. “Stojachie vorotniki i ‘ozherelki’ v drevnerusskoj odezhde.” Srednevekovaja Rus’. Moscow, 1957, p. 228..

Stylized “trees of life” are also included in the design of a different part of the same standing collar from Mikhali (illus. 9а)[51]idem., p. 226.. A similar motif, with alternating “trees” and birds inside circles, was used in an 11th-12th century embroidery from the Derevjanitskij burial ground near Novgorod (illus. 9д). They are couched with untwisted silk threads to brown silk fabric. This is a fragment of a standing collar[52]NIAKhMZ, no. KP31899. Konetskij, V.Ja. “Drevnerusskij gruntovyj mogil’nik u poselka Drevjanitsy okolo Novgoroda.” Novgorodskij istoricheskij sbornik. Leningrad, 1984, No. 2(12), p. 50, image 52.. Identical images of birds and floral motifs enclosed in circles are sewn on a 12th century cuff from the burial mound near the village of Aseevo in the Moscow region (illus. 9в)[53]State Historical Museum [GIM], No. 78607, op. 462, no. 4. Size 10 x 2 cm..

9. Samples of ornamental embroidery:

а – fragment of a standing collar from a burial mound in the village of Mikhali near Suzdal’

б – fragment of embroidery from Shargorod, 11th-12th c.

в – fragment of a headband from a burial mound near the village of Aseevo, Moscow region, 12th c.

г – fragment of a collar from the Ivanovo region, 12th c.

д – standing collar from the Derevjanitskij burial ground near Novgorod, 11-12th c.

Images of birds are an element of zoomorphic ornament. Birds are seen on a 11th-12th century embroidery from Shargorod (illus. 9б), carried out in gimp[54]KGIM, No. V-2310.. The ornament consists of diamonds filled with various rosettes and birds. Similar images of birds are also seen on a 11th-12th century collar from the village of Lisno in the Vitebsk region[55]Sergeeva, Z.M. “Raskopki kurganov na severo-zapade Vitebskoj oblasti.” Arkheologicheskie otkrytija 1975 g. Moscow, 1975, p. 425., in a 12th century embroidery from Vladimir[56]Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi X-XIII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1936, illustration on p. 29., on 12th century embroidered cuffs from the villages of Aseevo in the Moscow region and Kokhany in the Smolensk region[57]Fekhner, M.V. “Drevnerusskoe zolotnoe shit’jo X-XIII vv. v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Istoricheskogo muzeja.[GIM]” Srednevekovye drevnosti Vostochnoj Evropy. Trudy GIM. No. 82. Moscow, 1993, Catalog number 39., and on a band from Staraja Rjazan’ where birds are located beside a sacred tree[58]Jakunina, L.I. Fragmenty tkanej iz Staroj Rjazani. Kratkie soobsch. Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury, XXI, 1947. Illus. 36/3.. There is also data of a standing collar with images of birds inside archways found in the Poltavsk region[59]Novits’ka, M.O. “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi (Za materialami rozkopok na teritorii URSR).” Arkheologija (XVIII), 1965, p. 32..

Exquisite embroidery from the 12th century found on a collar in the Ivanov region displays birds in profile inside round medallions, separated by elegant floral motifs (illus. 9г)[60]Fekhner, M.V. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi.” PKNO, 1978. Leningrad, 1979, p. 404.. This piece has much in common with the aforementioned fragments from Novgorod and Aseevo (illus. 9д-е, в). Birds were a common motif of 11th-12th century ornament. Analogies from other forms of applied art are presented in many sources[61]Fekhner, M.V. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Drevnej Rusi.” PKNO, 1978. Leningrad, 1979, p. 405..

Cheetahs are depicted on a rectangular chest decoration analogous to that which can be seen on a mosaic portrait of Empress Irene from the early 12th century found in the southern gallery of Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia. This embroidery was found by V.V. Voijko during the excavation of the burial of a young woman in Belgorod (illus. 6г). Two full (7.3 x 8 cm) and two fragmentary images of cheetahs whose bodies turn into knotwork have been preserved[62]Kiev State Historical Museum, no. v-1783, v-2264; Novits’ka, M.O. “Haptuvannja v Kyivs’kij Rusi (Za materialami rozkopok na teritorii URSR).” Arkheologija (XVIII), 1965, p. 32.. “The cheetahs are part of a complex braid found in one of the burials from the 11th-12th centuries in Belgorod on the chest of the deceased. Rising sharply on either side of the lilies which emerge from the knotwork, they give the composition a heraldic appearance”[63]Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 46..

In the 1830’s, fragments of silk fabric were found in the royal tombs of Rjazan’s Cathedral of Sts. Boris and Gleb, on which “golden images of dragons, ostriches, crocodiles, vultures, etc.” were depicted[64]Tikhomirov, D. Istoricheskie svedenija ob arkheologicheskikh issledovanijakh v Staroj Rjazani. Moscow, 1844, p. 14-15, illustration 5; Mongajt, A.L. Staraja Rjazan’. Moscow, 1955, p. 171, illus. 131..

Of unknown purpose are the fragments of embroidery from the Michajlovskij crypt (illus. 5и) found by M.F. Beljashevskij. Its large ornamental motifs, 9-10 cm tall, from stylized spiral shoots and archways has no analogy. As can be seen from the above examples, archways are relatively frequently seen as a way of rhythmically dividing a design (illus. 7к). Another preserved fragment from the Mikhajlovskij crypt was perhaps part of “a valuable shoulder strap – from it, a piece of collar remains…”[65]Beljashevskij,N. “Tsennyj klad velikoknjazheskoj epokhi.” Arkheologicheskaja letopis’ juzhnoj Rossii No. 5, 1903. Moscow, 1904, p. 302-303., decorated along the edges with gold semi-circular decorative plaques [drobnitsy] and small pearls. L.I. Jakunina believed that no examples of pearl work had survived from the 12th century[66]Jakunina, L.I. Russkoe shit’jo zhemchugom. Moscow, 1955.. Modern methods of research allow us to identify traces of pearl work, even after the pearl work itself has been completely lost. In addition to fragments of embroidery from the Mikhajlovskij crypt, pearls were used to decorate a sleeve cuff from Ivorov (see below), the aforementioned cuff from the excavations of the Cathedral of the Assumption in the Moscow Kremlin, and other pieces.

The unity of the ornamental style and the commonality of technical methods of embroidery are characteristic for different artistic centers of Medieval Rus’: Kiev, Chernihiv, Lviv, Vladimir on the Kljaz’ma, Novgorod, Rjazan’, Nizhnij Novgorod, and other cities.

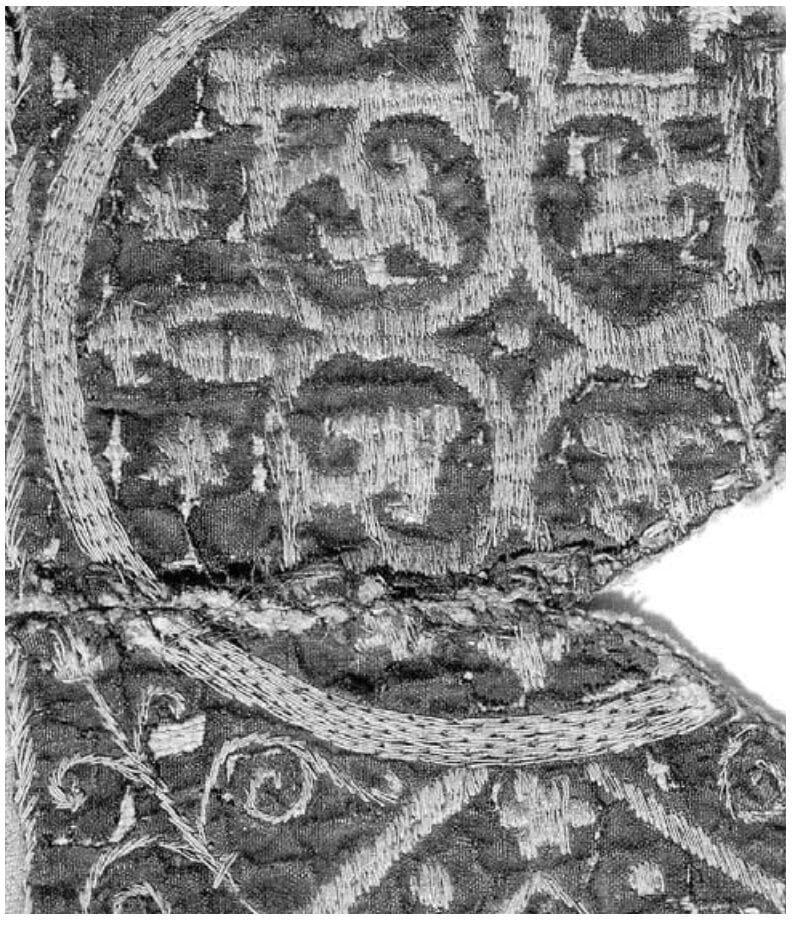

In addition to the technique of passing the gold through the fabric [shit’jo “na projom”], we also encounter couching [shit’jo “v prikrep”]: metallic threads are laid over the fabric and held down to it by tiny stitches of silken thread which pass through the fabric. The transition to this simpler and more convenient form of goldwork occurs in the late 12th-early 13th century. A 10th-12th century embroidery from the village of Zhezhavy[67]Historical Museum of Lviv. was carried out using this method; it consists of wide bands of diamonds, around which are placed rosettes (illus. 11).

An embroidery from Chersonesos[68]Chersonesus Historical-Archeological Museum, no. 6292. dated to the 12th century has the most complex composition of embroidery, possibly used to decorate the lower hem of an item of clothing (illus. 13). It is interesting to note that in width (about 20 cm), it is similar to the hem of clothing from the family of Jaroslav on the fresco in the Kiev St. Sophia cathedral. The main strip is edged above and below by narrow stripes filled with a complex braided design. On the top and bottom edges, the plant motifs are turned to one side, confirming the horizonal position of the embroidery. This embroidery, like the one from Zhezhavy, is worked in surface couching, and the metal threads are laid not along the design, but across the narrow width of the pattern, always turning back and forth where it meets the fabric edge (satin stitch [shov “v lom”]).

Kievan Rus’ was tied to Byzantium by both military as well as trade and cultural ties. M.A. Novitskaja suggests that the embroidery from Zhezhavy and especially from Khersonesos could have been brought from Byzantium. Gradually in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, the overside couching technique, which was more suitable for work with golden threads, spread throughout Byzantium, Western Europe, and in Rus’, replacing the practice of sewing the gold through the fabric. This gives evidence not only to close trace and economic ties between Rus’ and Byzantium, but also to their unity of cultural skills.

Surface couching was used on the border in the form of a braid on the collar of a woman’s outfit from a late 12th-early 13th century grave near the Church of St. John the Theologian in Smolensk (illus. 6б). The same item, however, also uses gold sewn through the fabric. Multiple techniques were also used on the embroidered collar from Maklakovo (illus. 5в): gold split stitch fills the outlines of the circles using dense red silk. The braid and interior of the circles, however, was sewn with surface couching. The edges of the design are outlined in colored silk.

A late 12th century embroidered collar from a woman’s grave near the village of Staroe Pushkino in the Moscow region is worked with surface couching (illus. 14).

Sister Marionilla Salamatova, who practices the technique of canvas stitching with gold, in her article “An Embroidered Collar from the Pre-Mongol Period from Chernihiv and the Technical Details of its Production”[69]Sister Marionilla (Salamatova). “Shityj vorotnichok domongol’skogo perioda iz Chernigova i tekhnicheskie ocobennosti ego ispolnenija.” Seredn’ovichni starozhitnosti Pivdennoi Rusi-Ukraini. Chernigiv, 2004. describes another variant of the surface couching technique which imitates gold split stitch. In this method, the couching stitch which comes to the front of the work and grabs the gold thread is then fed back down through the same hole from which it emerged, and the gold thread is pulled through to the reverse (illus. 15б). In following rows, the couching stitches are staggered. On the face, this appears the same as canvas stitching, and it is possible to tell the difference only from the reverse side and by tiny gaps along the edge of embroidered fragments[70]jeb: that is, where the gold threads reverse direction, as are seen in couched works[71]”When surface couching [шов «на проем», shov “na projom”], at the end of each row, it becomes necessary to make a stitch (or 2, not more) that violates the stitch sequence pattern… As a result, these thicken the stitching along the outer edges of each individual section, and cause higher relief on the front of the work due to the greater density on the reverse side. This is clearly seen in examples of embroidery from the 12th century where goldwork within the image completely covers the entire surface of the fabric. The embroideress consistently filled in row after row leaving very narrow strips of the background uncovered between.” (Sister Marionilla (Salamatova). “Shityj vorotnichok domongol’skogo perioda iz Chernigova i tekhnicheskie ocobennosti ego ispolnenija.” Seredn’ovichni starozhitnosti Pivdennoi Rusi-Ukraini. Chernigiv, 2004, p. 73). The prevalence of this method in early embroidery remains an open question.

The heart-shaped design of the collar (illus. 12) is very reminiscent of the collar from the burial mounds near the villages of Staroe Bykovo[72]Fekhner, M.V. “Drevnerusskoe zolotnoe shit’jo X-XIII vv. v sobranii Gosudarstvennogo Istoricheskogo muzeja.[GIM]” Srednevekovye drevnosti Vostochnoj Evropy. Trudy GIM. No. 82. Moscow, 1993, Catalog number 22. and Kubaevo in the Vladimir region (illus. 10).

Interesting analogies to the technique of couching imitating gold passing through the fabric (that is, underside-couching) can be seen in British embroideries from the same period. For example, several examples of embroidery in the Victoria and Albert Museum[73]King, Donald and Santina Levey. The Victoria and Albert Museum’s Textile Collection: Embroidery in Britain from 1200 to 1750. London, 1993. Cat. no. 3, 4. in London, judging by Donald King’s description, were worked in this method: for example, a fragment of embroidery dated 1160-1190 (illus. 18) and a part of a shoe (1220-1250) belonging to Bishop Walter de Cantelupe (illus. 16). Both are embroidered with couched gilt silver thread and silk stem stitches [stebel’chatij shov]. Liturgical outfits from the late 13th-early 14th centuries were decorated with both couched and split-stitch styles[74]idem., Cat. no. 5, 6, 7..

An example from an earlier time in the same museum, the orarion of St. Cuthbert depicting Peter, St. Gregory’s Deacon, dating to 909-916, uses the techniques of couched goldwork, split stitch silk, and silk stem stitch (illus. 17)[75]idem., Cat. no. 1..

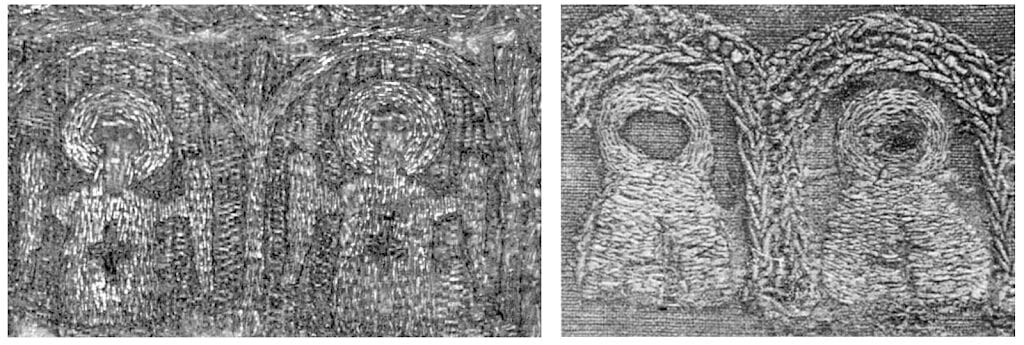

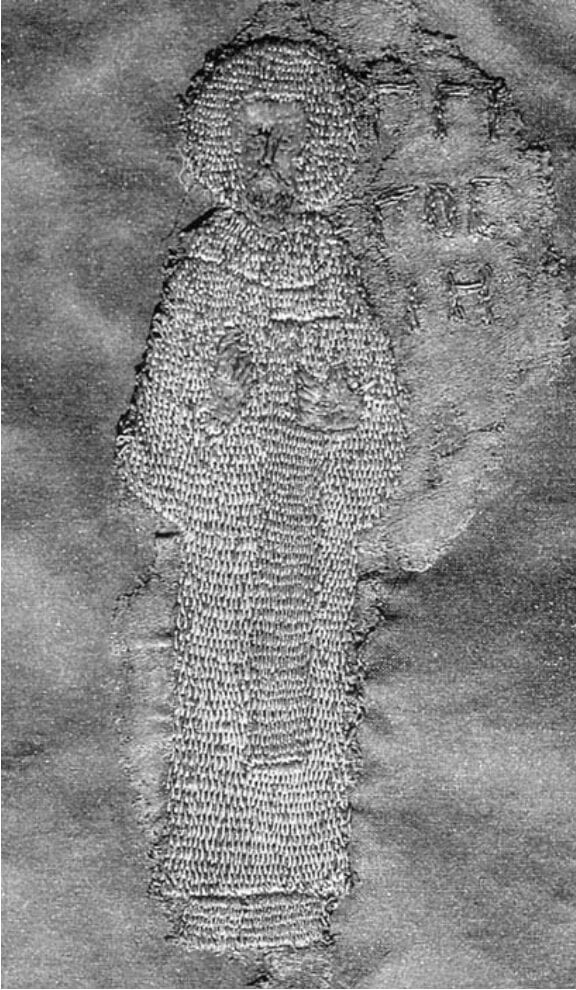

Along with the ornamental designs, in medieval Russian embroidery of the period under review, we also encounter ecclesiastical designs. On a fragment of one of the 12 standing collars found in the Novgorod Derevjanitskij burial ground, there are depicted 5 embroidered half-length figures of angels enclosed in semi-circular arches. Above and to the right there is a decoration in the form of a braid (illus. 19а, 20)[76]Konetskij, V.Ja. “Drevnerusskij gruntovyj mogil’nik u poselka Derevjanitsy okolo Novgoroda.” Novgorodskij istoricheskij sbornik, no. 2(12), Leningrad, 1984, p. 60, illus. 52; Ignashina, E.V. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe i ornamental’noe shit’jo v sobranii Novgorodskogo muzeja: Katalog. Velikij Novgorod, 2003, p. 24, cat. no. 16.. This miniature embroidery (the width of the fragment is 4.8 cm) is worked on brown silk fabric, with twisted and smooth gold thread in split stitch.

а – fragment of a collar from the Derevjanitskij burial ground near Novgorod

б – fragment of a headband from a burial near the village of Ivorovo, Tversk region

в – gold fabric band from a mound near the village of Maklakovo, Rjazan’ region, 12th-early 13th c.

Similar embroidery was found in a female grave near the village of Ivorovo in the Tversk region. On a fragment of a headband, part of a half-length Deësis composition[77]Komarov, K.I. and A.K. Elkina. “Kurgannij mogil’nik v okrestnosjakh r. Staritsy.” Vostochnaja Evropa v epokhu kamnja i bronzy. Moscow, 1976, p. 234. It is not clear why the authors call this composition a Deisis. As far as can be determined from the photographs and reconstructions, it appears frontal images of saints are located between the arches. But, due to the small size and poor quality of the photos, it is difficult to tell for sure., embroidered with colored silk and wrapped silver threads, was preserved (illus. 19б, 20). The arches are 2.5 cm tall; the figures are 1.8 cm tall. “The half-length figures of the saints with halos are embroidered in horizontal stitches with a checkerboard pattern. The following three are worked with vertical stitches which fall in ray shapes from top to bottom, as if depicting the draping folds of clothing. The halos are sewn in circular rows of stitches. Traces of split-stitch embroidery in silk remain, following the contours of the face and hands.” The figures themselves are worked in wound gold-plated silver; the arches are worked in four cords twisted in different directions from specially-made threads: silk wrapped around pre-spun gold threads. The arches and contours of the halos preserve traces of pearl-work. “The sharp contrast of the smooth figures, sewn airily in gold threads, with the relief archways and pearls protruding above the plane of the fabric, gave the entire miniature composition of the Deësis a particular sternness and architecturalism”[78]Komarov, K.I. and A.K. Elkina. “Kurgannij mogil’nik v okrestnosjakh r. Staritsy.” Vostochnaja Evropa v epokhu kamnja i bronzy. Moscow, 1976, p. 234..

A very close analogy to this headband mentioned above is another headband from the Karash burial mound, where half-length figures of saints surrounded by arches alternate with ornamental motifs[79]Uvarov, A.S. Atlas i issledovaniju o merjanakh i ikh byte. Moscow, 1872, Table XXXV; Spitsyn, A.A. “Vladimirskie kurgany.” Izvestija arkheologicheskoj komissii [IAK]. No. 15, St. Petersburg, 1905, p. 148, illus. 257..

In the History Museum in Kiev are preserved fragments of a 12th century standing collar decorated with arches and half-length saints, alternating with images of birds[80]Orlov, R.S. “Davn’orus’ka vishivka XII st.”, Arkheologija, 1973, no. 12..

Ecclesiastical embroidery also decorates a band found in the royal burials found in the vestibule of the Cathedral of Sts. Boris and Gleb in Staraja Rjazan’. On it, one can discern the bust-length portrait of a saint with unproportionally large hands uplifted[81]Tikhomirov, D. Istoricheskie svedenija ob arkheologicheskikh issledovanijakh v Staroj Rjazani. Moscow, 1844..

Analogous ecclesiastical designs are also found on Byzantine golden bands (already described above). One of these bands was found in a 12 century female grave under the Cathedral of the Assumption in the Moscow Kremlin[82]Sheljapina, N.S. Arkheologicheskie issledovanija v Uspenskom sobore. MMK. Materialy i issledovanija. No. 1, Moscow, 1973, p. 59-60.. In the center is a half-length image of the Virgin Orans, flanked on both sides by figures of the archangels in square frames. The images are woven in silk on a gold background.

A preserved fragment of a golden band with a half-length Deësis composition (illus. 19в) was discovered during excavations of 12-early 13th century burial mounds near the village of Maklakovo in the Rjazan’ region[83]Fekhner, M.V. “Izdelija shjolkotkatskikh masterskikh Visantii v Drevnej Rusi.” Sovetskaja arkheologija, 1977 (3), p. 141.. The burial was undoubtedly Christian, and the braid appears “as if a prototype for later funerary circlets”[84]Fekhner, M.V. “Shjolkovye tkani kak istochnik dlja izuchenija ekonomicheskikh svjazej Drevnej Rusi.” Istorija kul’tury Vostochnoj Evropy po arkheolchicheskim dannym. Moscow, 1971, p. 221., used in Christian funerals to this day.

Golden bands brought from Byzantium would have been expensive means of decoration. As was already mentioned above, they were often imitated through embroidery. “They probably began to imitate the ornament of expensive patterned fabrics contemporaneous to their appearance in Rus'”[85]Komarov, K.I. and A.K. Elkina. “Kurgannij mogil’nik v okrestnosjakh r. Staritsy.” Vostochnaja Evropa v epokhu kamnja i bronzy. Moscow, 1976, p. 235..

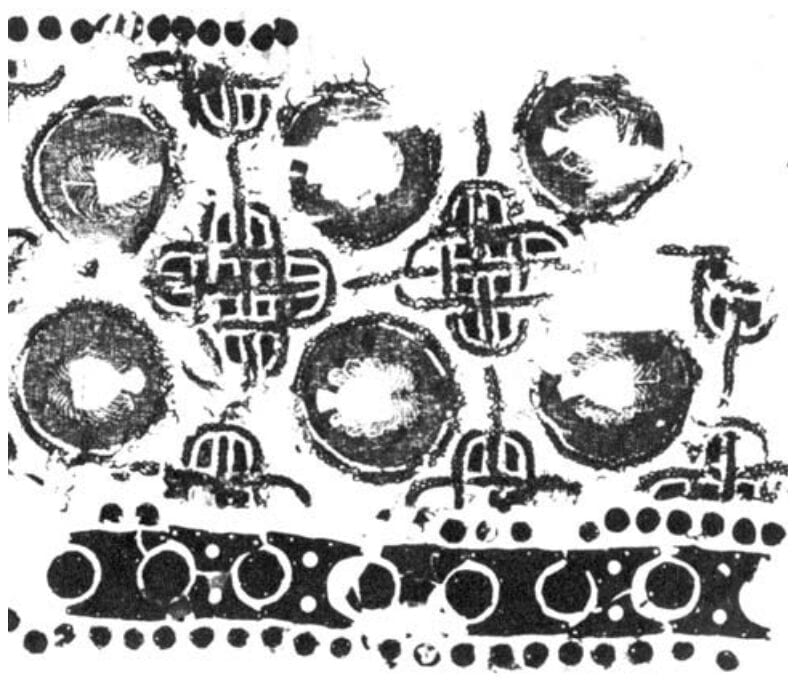

In the early 1980s, the late 12th-early 13th century Chingul’ burial mound was excavated on the banks of the Molochnaja river[86]Otroschenko, V. and Ju. Rassamakin. “Polovetskij khan ili?…” Znanie – sila, July 1986, p. 30-32.. This was an extremely lavish burial of a noble medieval nomad warrior. Of particular interest to us are two of the six kaftans which were able to be reconstructed in detail. The deceased was buried in a kaftan of thick scarlet silk with goldworked inserts on a blue background. The entire front, the upper sleeves, and the wrists were decorated with embroidery. The design is a grid with gold plaques at the intersections, and inside the squares are circles decorated with golden faces, some female, and some angelic (illus. 21, 22, 23). The kaftan collar and a round cap were decorated with golden plaques with inlaid gems. A row of pearls follows the outline of the design.

The second kaftan is just as luxurious, and is also decorated with ecclesiastical embroidery: the chest of the warrior was decorated with the Image of Edessa. The fabric and threads were produced in Constantinople. The second kaftan has a Slavonic inscription, which led A.K. Elkina to interpret the work as of Russian make, produced in the court of the Great Russian Princes shortly before the Mongol invasion (illus. 24).

Unfortunately we cannot include in this overview the exquisite examples of embroidery found in 1999 in the royal burials in Novgorod’s St. Sophia. The superb preservation, fine ornamentation and interesting subject of these embroideries will, we hope, serve as a shining page in the history of pre-Mongol needlework following their publication. The total number of preserved fragments of goldwork from secular clothing is relatively large. As for items of liturgical origin, the researcher has only a few examples at their disposal. There are a few items in the Novgorod museum, remnants of episcopal burial vestments from Kiev’s St. Sophia, and a podea in the State Historical Museum.

In 1936, during the excavations of the altar section of Kiev’s St. Sophia, several fragments of goldwork embroidery, scattered and in poor condition, were found in one of the metropolitan tombs from the 1280s[87]Novitskaja, M.A. “Vyshivki zolotom s izobrazheniem figur, najdennie pre raskopkax v Sofii Kievskoj.” Sofija Kievskaja: Materialy i issledovanija. Kiev, 1973, p. 62.. Three of these make up a composition of “The Virgin Orans with Angels,” and five of the others have images of saints. The ornamental motifs were of “trees of life” and so forth. The St. Sophia embroideries were executed on brown silk. The clothing of the Virgin, the angels and the saints were embroidered mostly in wrapped gold threads, with wrapped silver threads used in details. Hands and faces were worked in colored, unspun silk in one direction; hair and shoes are dark brown; the lips are red; facial details are also worked in dark brown silk in stem stitch. The main features of the figures are sewn in stem stitch, with details in couched gold. We have seen this combination of techniques in examples of secular embroidery seen above. To indicate the contours and folds on the clothing, narrow stripes of the background were left unembroidered.

In the center of the composition is the Virgin Orans (to the right of her halo is preserved the inscription “MR”). She is dressed in a long narrow tunic and shift which stretch below the knee; her arms are bent with the hands raised upward. The facial embroidery has not survived. Flanking the Virgin, angels with down-stretched wings (the height of each about 10.75 cm) gesture toward her[88]Novits’ka, M.O. “Davn’orus’ke haptuvannja z firurnimi zoobrazhennjami.” Arkheologija (XVIV), 1970, p. 88.. They are wearing gold chitons with silver hems, and gold cloaks with silver linings. The upper parts of their golden wings are worked in vertical stitches, and are separated by a silver stripe from the lower section, which are sewn in a herringbone pattern (illus. 25).

The figures of the saints are front-facing; they bless with their right hand, and in their left, they hold the Gospels. They wear an omophorion over their sakkos. The entire figure of the first saint (height 12.7 cm)[89]idem., p. 93. is embroidered in gold, and to the right of his halo are preserved the letters GIO with a symbol above, which can be interpreted as an abbreviation of “AGIOS” [“Saint”]. The clothing of the second saint is a mixture of gold and silver. This is the only figure where the embroidery of the face, filled in with light silk, remains. Judging by the surviving inscriptions, which has a Slavonic rather than Greek ending, this is St. Gregory the Theologican (illus. 26). Three other saints are dressed in an undertunic, phelonion, epitrachelion and omophorion, which speaks to their holy nature. One of these figures is embroidered in silver and gold threads; the other two in gold. M.A. Novitskaja believes that these were embroidered by different seamstresses, “… differing in their level of observation and of differing mastery of goldwork. This is visible in the differing lengths of the stitches: sometimes tiny and tightly fitting one after another, and others longer and placed further apart”[90]Novitskaja, M.A. “Vyshivki zolotom s izobrazheniem figur, najdennie pre raskopkax v Sofii Kievskoj.” Sofija Kievskaja: Materialy i issledovanija. Kiev, 1973, p. 65..

Surviving fragments of ornamental embroidery show floral decoration (illus. 27). It was possible to reconstruct 3 compositions of the “tree of life” on the St. Sophia embroideries, along with part of a fourth. The contours are worked in silk split stitch, but are barely preserved.

It is possible that the saintly figures and the floral ornamentation were located on an epitrachelion, and the composition with the Virgin could have been located on the shoulder of a phelonion. M.A. Novitskaja believes that they were worked by local Kievan needleworkers and dates them to the 12th century[91]Novits’ka, M.O. “Davn’orus’ke gaptuvannja z fihurnimi zoobrazhennjami.” Arkheologija (XVIV), 1970, p. 98..

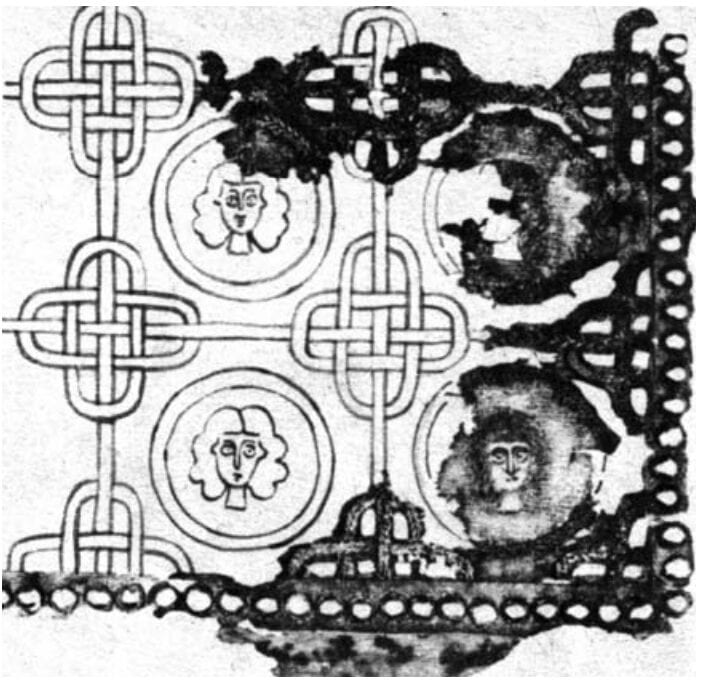

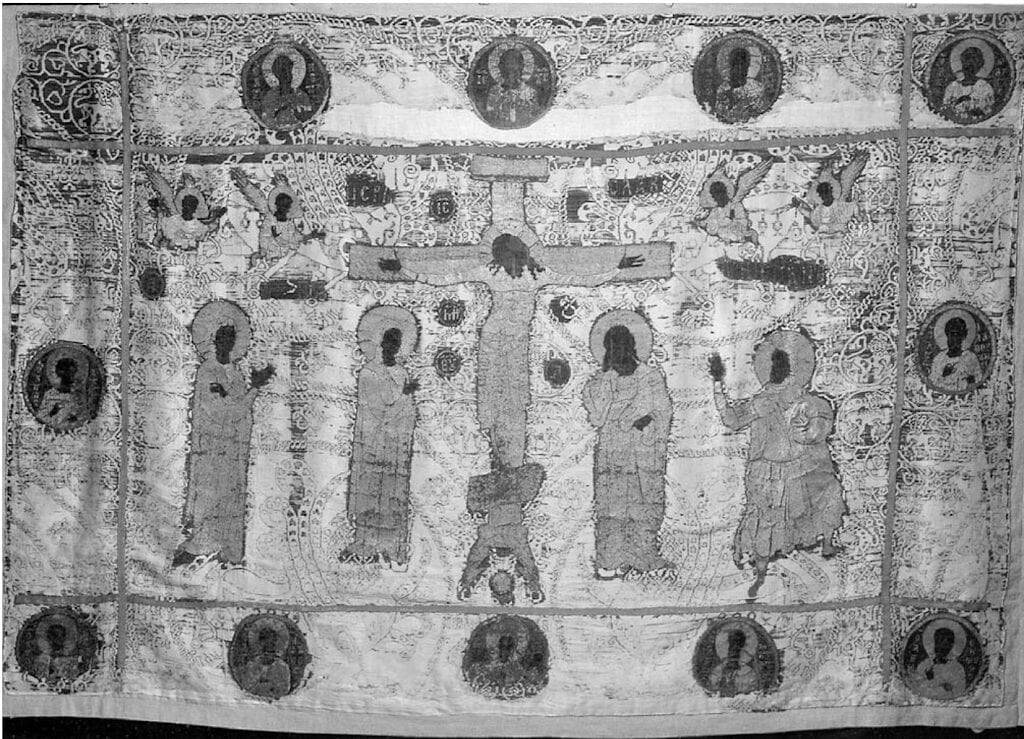

The early works of Novgorod embroidery include a podea from the last quarter of the 12th century, “The Crucifixion with the Forthcoming” [“predstojaschie”], allegedly originating from Novgorod’s Juriev Monastery (illus. 28, 29)[92]Gosudarst’venij istoricheskij muzej, No. 55115/RB-1674.. In the center of the podea to either side of the crucified Christ are depicted the Virgin, St. John the Theologian, Mary Magdelene, and the centurion St. Longinus. At the top of the middle section, four angels float beside the cross with upraised hands. Along the border of the podea in 11 medallions are the images of the Savior and Virgin of the Sign (in the center of the top and bottom borders) and various apostles. Originally, the figures were embroidered on a dark silken twill weave fabric, which is preserved in a few spots where the silk embroidery in the faces and under the inscriptions has been lost over time. Later, probably in the last 12th-13th centuries, the figures were transferred to a new background, at which time the order of the medallions was modified (the Evangelists most likely were originally in the 4 corners), and the ratio of the centerpiece to the border was lost. This new background was of a rather ancient Byzantine[93]Regarding this fabric, scholars are of differing opinions. A.N. Svirin considered it to be a rare example of late-Sassanid as interpreted through Byzantine culture (Svirin, A.N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1963, p. 24); L.V. Efimova calls it a fabric “of 11th century Byzantine make” (Efimova, L.V. and R.M. Belogradskaja. Russkaja vyshivka i kruzhevo. Moscow, 1982. silk fabric with a large pattern: winged bulls are seen enclosed in circles, surrounded by lions and cheetahs.

The clothing was sewn with wrapped gold and silver threads split-stitch style, with the folds outlined in silk. The faces of all of the characters were also worked in silk stitches which have not survived. The body of the Savior (except the face, hair, hands and feet) was sewn with golden thread split-stitch style. This unusual style of ecclesiastical embroidery is quite rarely seen[94]14th century shroud [plaschanitsa] from the Pantokrator monastery on Mt. Athos; 16th century Aër [vozdukh] from the Suzdal museum; a 17th century podea [pelena] called “The Virgin of the Caves with Anthony and Theodosius” from the Russian State Museum [GRM], et.al..

[jeb: Color photo found online here.]

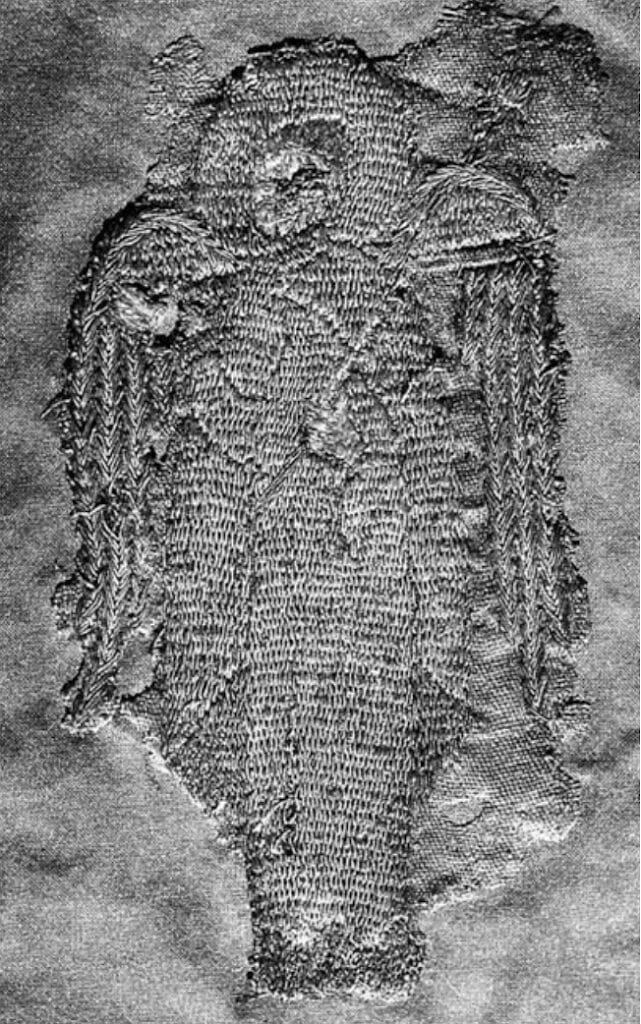

In the Novgorod Museum are displayed the so-called Epimanikia of St. Varlaam of Khutyn (illus. 30, 31)[95]NIAKhMZ [Novgorodskij istoriko-arkhitekturnyj i khudozhestvennyj muzej-zapovednik], No. KP 2118.. On each is seen a 3-figured Deësis: the adult figure of Christ is placed in the center awaiting the Virgin and John the Baptist. This version of the Deësis is known from both Byzantine and Russian examples. V.G. Putsko, based on the general nature of the composition and its details, does not rule out “the possibility that an image from an illuminated Byzantine manuscript may have served as a direct source”[96]For more details, see: Putsko, V.G. Drevnie poruchi iz Khutynskogo monastyrja. http://copy-www.novsu.ac.ru/chelo/9/puzko/puzko.htm.

The components of the Deësis are surrounded by semicircular arches supported by columns with rectangular capitals. The base is a strip of floral ornament, composed of garlands of acanthus leaves. The same band completes the composition from above. Two other variants of stylized floral ornament are located in the archways and in the columns supporting them. “Although the elements of the Deësis are central to the epimanikia, the role of floral ornament here is also significant. In general, artistic feeling is given almost paramount importance. The ratio of the ornamental stripes both to themselves and to the central composition has been keenly worked out by the artist”[97]Manushina, T.N. “K voprosu ob ornamentike v proizvedenijakh russkogo shit’ja XII-XV vekov.” Drevnerusskoe khudozhestvennoe shit’jo: GMMK [Gosudarstvennij istoriko-kul’turnij muzej-zapovednik “Moskovskij Kreml'”]. Materialy i issledovanija. Moscow, 1995, p. 161..

It is interesting to note that the pattern enclosed in the semicircles of the arches are practically identical to the headband ornament from Starij Galich and Kiev (illus. 7а, б), which again confirms the commonality of ornament of both secular and religious items, as well as the ornament that runs along the edge of the so-called Dalmatic of Charlemagne (a Byzantine sakkos from the 14th century). [jeb: see image here.]

The embroidery is worked with wrapped gilt silver on dark blue silk fabric. The folds of the clothes are marked in thin lines worked in dark silk stitches. The goldwork is not fully preserved. The facial embroidery, sewn in flesh-colored silk, are almost completely lost. The contours of the design are outlined in small pearls without any support. The inscriptions are embroidered in wrapped gold threads in Greek-styled Cyrillic letters. In manner of technique, the epimanikia are analogous to the aforementioned epitrachelion from the metropolitan grave in Kiev’s St. Sophia, and to the podea with the Crucifixion from the State Historical Museum.

N.A. Majasova does not cast doubt on the possibility that the epimanikia belonged to the hermit Varlaam of Khutyn. V.G. Putsko suggests that they belonged to Novgorod Archbishop Anthony (aka Dobrynja Jadrejkovich), as such precious epimanikia are more in character with episcopal vestments. Anthony (a monk from Khutyn) occupied the Novgorod prelate from 1210-1220, and again from 1226-1229. After retirement, he lived in the Khutynskij monastery, where he died in 1232. “After his death, items from the episcopal household would have been left behind, including possibly the epimanikia under discussion”[98]Putsko, V.G. Drevnie poruchi iz Khutynskogo monastyrja. http://copy-www.novsu.ac.ru/chelo/9/puzko/puzko.htm. A similar story took place with a Khutyn servant who belonged to Anthony, but was later attributed to St. Varlaam. Based on this, Putsko proposes a later date for the epimanikia: the first quarter of the 13th century.

An interesting example of 12th century ornamental embroidery is the hem of a phelonion from the Antoniev monastery, the so-called Chasuble of Anthony the Roman (illus. 22 [sic], 32)[99]NIAKhMZ [Novgorodskij istoriko-arkhitekturnyj i khudozhestvennyj muzej-zapovednik], No. KP 2118.. It depicts alternating ovals and circles with paired images of fantastic beasts on either side of a stylized tree. Technically, this item is different from those discussed above. The embroidery is worked on a foundation of gold and blue damask in spun gold above a base of linen thread. Due to the linen thread, the embroidery acquired a heightened relief. The original purpose of this embroidery is not known. The hem is divided into two parts: The upper half is sewn directly to the front of the phelonion’s hem; the lower is attached to the hem from behind. The phelonion itself, sewn from light colored damask and with a shoulder of golden velvet, has an ancient bell-shaped cut and was first mentioned in the Inventory of the Novgorod Savior of Khutynsk Monastery in 1642.

A.N. Svirin further noted the similarity of the images in this embroidery to the pattern of a Byzantine silk fabric stored in London’s Kensington Museum (illus. 34). “The complete similarity of the border ornamentation and the embroidered pattern has us convinced that embroiderers used fabric patterns for ornamental compositions”[100]Svirin, A.N. Drevnerusskoe shit’jo. Moscow, 1963, p. 24.. In turn the motif of birds or fantastic beasts symmetrically arranged on either side of a sacred tree as a design on Byzantine textiles is one that came to Byzantium from Sassanid art.

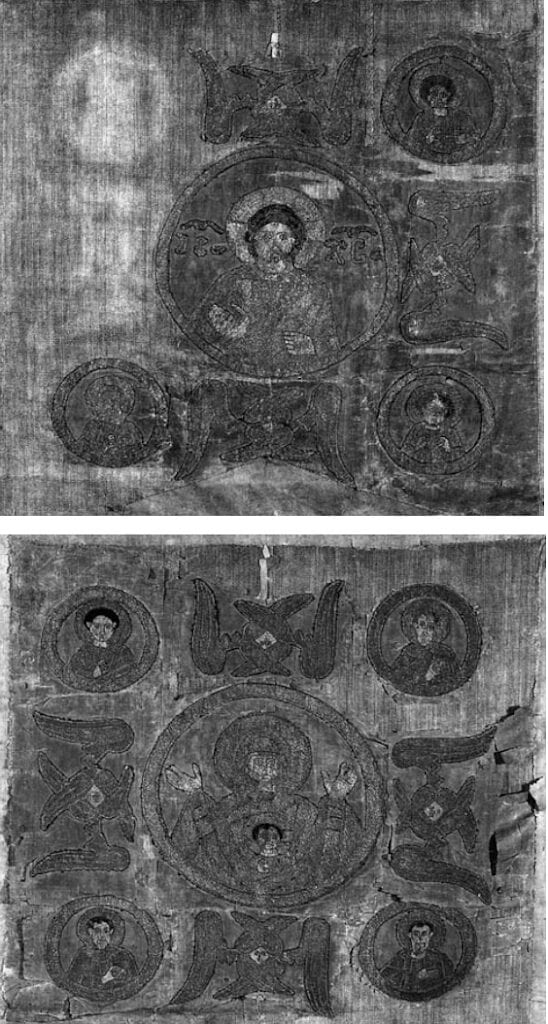

The most recent examples in a series of famous examples of 10th-13th century embroidery are two veils recently published by N.A. Majasova from the collection of the Museum of the Moscow Kremlin (illus. 35-36)[101]Majasova, N.A. Drevnerusskoe litsevoe shit’jo v sobranii Muzeev Moskovskogo Kremlja. Moscow, 2004. Cat. no. 1, p. 79-80.. Their origin has not yet been established; the museum acquired tem in 1925 from the collector S.P. Tjulin as sides of a banner. But, their size and composition allow us to consider them to be the earliest examples of Aërs for a chalice and diskos. On the first Aër, the central round medallion depicts the half-length figure of Christ Pantokrator; in the smaller corner medallions are three (the fourth is lost) half-length figures of the apostles, with cherubs between them. In our time, the Savior and the apostles are presented frontally; the cherubs surrounding the medallion with the Savior have their heads turned toward the center. The second veil has a similar composition: in the central medallion, surrounded by cherubs, is the Virgin Incarnate, with the evangelists in the corners.

In places where the embroidery has been lost, the original foundation fabric, a crimson taffeta, is visible. Today, the foundation is an ancient coarse-grained linen with remnants of sand-colored taffeta. The faces are embroidered with sand-colored unwound silk with large split stitches in one direction. The outlines and hair are worked in brown silk. All of the clothing is worked in wound gold threads that are couched (in brickwork and zigzag patterns, with tiny stitches). Based on technique of execution, it seems to us that they were worked in a relatively later period. Only a lining of linen threads has survived of the pearl-work. The silk embroidery is poorly preserved, and the gold shows signs of wear. At the time when it was repaired, the small medallions swapped positions; in addition to the images of an apostle and a cherub on the diskos Aër, the borders and inscriptions have been lost.

“Several of the features (stocky figures with round heads, protruding ears, and large hands), the combination of the images of the Savior Pantocrator and the Virgin of the Sign (in the variant called ‘Incarnate’), the archaic and somewhat primitive nature of the images with the marked features of the four faces found in 13th century Novgorod art, the technique of the embroidery… allow us to determine that the Aërs were created in Novgorod earlier than the 14th century. In the Inventory of the Armory, the works are dated to the 11-12th century, with this postscript: ‘Novgorod embroidery'”[102]idem., p. 80..

Conclusion

The small number and not always well preserved nature of items do not allow us to fully recreate the picture of the development of medieval Russian embroidery of the 10th-13th centuries. Based on data from archeological sources, we can only draw the following preliminary conclusions:

(1) All materials used in embroidery (such as the silk fabrics for the foundation, as well as the gold, silver and silken threads) were imported, therefore, their cost would have been relatively high. Nevertheless, they decorated with goldwork not only vestments of feudal nobility, but also some parts of festive clothing (collars, edges of sleeves, headbands) of the urban and rural population of medieval Rus’.

(2) The main technique used in goldwork was split-stitch style, with the gold passing through the fabric. At the turn of the 12th-13th centuries, this was replaced by the simpler and easier method of embroidering via couching. The edges of goldwork were often additionally outlined with silk thread in “straight stitches” [shvi “vperjod igolku”] or in stem stitch.

L.I. Pogodin considers the prototype of the technique of gold couching to be the ancient Eastern method of embroidering with couched cord (“laced cord”). In the ancient East it is well known that carpets were decorated in this way. He posits that the relatively late arrival of couching gold threads in this manner was due to the centuries-old tradition of embroidering with simple threads through the fabric[103]Pogodin, L.I. “Zolotnoe shit’jo Zapadnoj Sibiri (pervaja polovina 1 tys. n. e.)” Istoricheskij ezhegodnik, 1996, p. 123-134. Omsk State University, 1999..

At the same time, M. Dreger, a German scholar of medieval goldwork, explained the use of split-stitch style technique in medieval Rus’ was due to the close kinship of members of the Great Princely family to rulers of northern and western Europe: Yaroslav the Wise’s wife Indigerd was the daughter of Norway’s King Olaf, their sons were married to representatives of German feudal nobility. He argues that the method of sewing gold through the fabric was common to all the northern lands, while couching goldwork was a method used by southern lands, including Byzantium[104]Novitskaja, M.A. “Zolotnaja vyshivka Kievskoj Rusi.” Byzantinoslavica XXXIII, Prague, 1972, p. 49..

Unfortunately, questions about relation, possible mutual influences, and possible borrowings between western European and medieval Russian embroidery in this period have not been sufficiently studied. The same is likewise true for Russian-Eastern relations. Examples of goldwork embroidery are also found in the tombs of the tribes that roamed the southeastern borders of Rus’: the Pechenegs and the Polovtsy. The Rus’ principalities were continually in close contact with them (militarily, politically, and familially). Valuable embroidery was almost certainly among the gifts exchanged by the Russian princes and representatives of the nomadic aristocracy. It is fully possible that clothing embroidered with goldwork would also have passed in one or the other direction as spoils of war.