Having recently finished reading a very brief chapter in Schepkin’s Textbook of Russian Paleography on the tools of the medieval Russian scribe, I was interested to find more, and happened upon V.A. Schavinsky’s book Notes on the History of Painting Techniques and Paint Technology in Medieval Rus’, which has a quite lengthy chapter devoted to the topic. He starts with a brief discussion of medieval quills, but then goes into a quite lengthy discussion of the three types of inks used in medieval Russia (and elsewhere): atramentum (lampblack- or soot-based ink), incaustum (inks based on plant-based tannins), and ferrous inks (inks which contain iron salts). This chapter a challenge to read, because it contains a lot of chemistry vocabulary that I wasn’t previously familiar with. But, the challenge became more fun when he started including a number of quotations from medieval recipes for ink. I discovered how to show side-by-side text, so I’ve used this to show the original medieval Russian text next to my translation – I found these to be interesting puzzles, so I’m “showing my work”, as they say in math class. In all this was a very interesting read, with lots of source material for the SCA scribe.

With What Did the Russian Scribe Write?

A translation of Щавинский В. А. «Чем писал русский книгописец?» Очерки по истории техники живописи и технологии красок в древней Руси. М., Л., 1935. с. 21-38. / Schavinskij, V.A. “Chem pisal russkij knigopisets?” Ocherki po istorii tekhniki zhivopisi i tekhnologii krasok v drevnej Rusi. Moscow-Leningrad, 1935, pp. 21-38. [Notes on the History of Painting Techniques and Paint Technology in Medieval Rus’.]

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.icon-art.info/bibliogr_item.php?id=10230. ]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

Similarity is not uniform, and compositional differences are complex.

– Nicodemus of Syria

At the beginning of this century, in the Kargopol’ district of the Olonets province, there still existed a significant number of peasant families possessed of a singularly unusual profession for such folk. They were engaged in the copying of Old Believer books. This art took root in this location long ago. It was carried out primarily by young ladies who had perfectly mastered the Pomor’ye style of writing. Around 1910, this trade ended, having been replaced by another, more lucrative business: embroidery, to satisfy the growing demand at this time in Russian cities and abroad for Russian handicraft.[1]Reported by the renowned expert of Old Believer writing, V.G. Druzhinin. Thus ended the last school of scribes, not only in Rus’ but in general, an unbroken chain which had worked over the course of many centuries and even thousands of years.

Exactly when book writing began in Russia cannot be determined. We know only that Yaroslav the Wise, as recorded in the Chronicles, “was enamored of books, and having written many, placed them in St. Sophia’s Cathedral (in Kiev), and having gathered many scribes, translated many books from the Greek into Slavonic, and wrote many books,” and therefore that during his time, in Kiev, book creation was already a quite normal activity. His son, Grand Prince Svyatoslav, was also a great lover of books. He had “many books,” and in the Izbornik (collection) rewritten for him in 1073 by Deacon Ioann, his family portrait shows him with a book in his hands. Speaking of manuscripts of “Slavonic writing” in general, we have already missed the opportunity when we ought to have celebrated its thousandth anniversary.[2]On the prevalence of writing in medieval Rus’, cf: Sobolevskij, A.I. Slavjano-russkaja paleographija. Chapter 1. St. Petersburg, 1908.

It is difficult to imagine how many books were written in that time, just as it is impossible to count all the instances when and methods by which they were destroyed. If one imagines the painting from 1382 showing the burning of the Kremlin cathedrals during the Toktamysh invasion, when they were filled “to the hitch” (that is, to the roof) with books brought there “for the sake of preservation,” as the chronicler wrote, and remember that this image was repeated multiple times, not only in Moscow, but also in Kiev and other Russian cities, then it is hardly surprising that the number of medieval Russian books from the 14th century and earlier which have survived to modern day number less than 600. If one supposes that the 25,000 or so manuscripts surviving from the following three centuries (the 15th-17th) make up only 1/10 of those that were written in Russia over that time, this might barely begin to come close to the truth.

For a general assessment of the size of the written legacy of our past, we should also remember the charters and epigraphic works, the number of which was significantly larger, reaching the hundreds of thousands, or possibly even into the millions.

We became aware of the necessity of close acquaintance with this treasury of knowledge from our past over the course of the 19th century, and in the West a century earlier, through the science known as paleography. Its most important task is the determination of the time and place when a manuscript was written, given the manuscript does not directly state such information. We shall not enumerate there the various methods by which this is achieved, and shall say only that first and foremost, the branch of Slavic-Russian paleography reviews the tools and materials of writing, as well as the history of hands and individual letters.[3]Schepkin, V.N. Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1921, p. 11. jeb: see my translation here: https://rezansky.com/old-slavonic-and-the-slavonic-alphabets/

To answer the question which we posed in the title, we start with a topic which is not devoid of interest, that is, information related to the goose feather, the main and almost only[4]In a Pskovian Book of the Apostles from 1307, there is the following note: “I wrote this with a peahen quill.” writing tool used by Russian scribes.

The reed pen (Rus. трость, trost’, “cane”) depicted in the hand of a writing Evangelist in some miniatures is a echo of Eastern writing technique which was foreign to us. Daniil Zatochnik’s phrase “let my tongue be the reed pen of a hastened writer,” is a phrase taken from the Book of Psalms.[5]Sobolevskij, op. cit., p. 16. The image of goose quills along with a basic type of curved blade for cleaning them are often seen on Gospel miniatures.

A good description of the process used to clean features for various needs – for large or small skoropis’ (Rus. скоропись, “cursive”) writing, or for drawing with a pen – can be found in a collection from the 16th-17th centuries, in the article “On the pen:”

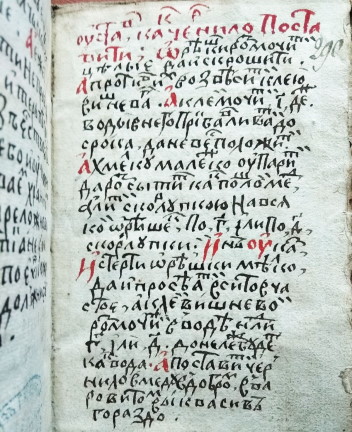

Достоит же пего чинити, к большему письму книжно пространно и тельно, к мелку ж мало, к знаменну по знамени, и к скорописно пространно ж. Срез же у книжных длее скорописнаго, у того ж сокращеннее. Разсчеп же у книжных и знаменна и скорописна твори в полы среза, аще тельно зело, аще ли жидко перо, и у того разсчеп твори не по срезу, но мал. У книжного большаго разсчеп твори подлее мелька вдвое. У книжных же конец кос на десно, у снаменных же на шуе, у скорописных впрям. И аще случится починити книжна ли знаменна, скрашеной стране самый мало, скорописна ж и с обоих. Аще ли раздвоится, срежи весь разсчеп и учини новой.

The quill needs to be cleaned, extensively and thoroughly for large book writing, a little bit for small writing, for znamenny chant notation (Rus. знаменное, znamennoe) according to the size of the notation, and extensively for skoropis‘. The cut is longer for book hands than it is for skoropis’, where the cut is smaller. For book work, znamenny, and skoropis’, make a slit the length of the cut tip if the feather is very stiff, or if the feather is soft, then make the slit not the full length, but smaller. For book writing, make the slit twice as long. For book writing, cut the tip straight across, for znamenny angle it to the left, and for skoropis’, angle it to the right. And if one is cleaning a quill for a book or for znamenny, the cut side of the tip should be very narrow, while for skoropis’ both sides should be narrow. If one should break the tip, then cut off the entire tip and start anew.

Another article from a second collection, also entitled “On the pen,” once again reminds us that this is not a new science. The 16th century scribe writes about how to construct a pen such that one would be able to write an entire page from a single dip of ink. He addresses this problem, which was only finally solved in the 20th century, simply and uniquely.[6]A manuscript collection of various articles from the 16th-17th centuries, Pub. Lib. XVII, no. 17. Published by P. Simoni in Памятники древней письменности и искусства [“Works of Medieval Writing and Art”], vol. CLXI. These publications by P. Simoni, which are excellent in terms of their scientific accuracy as well as the previously unpublished collection of antique texts which they kindly provide, will serve as the primary material for our further study.

If the method of cutting a quill can give the paleographer certain signs which influence the character of hand and the tracing of letters, then the ink (Rus. чернила, chernila) used should be of even greater importance, assuming, of course, that its composition did not remain unchanged over time. Modern take on the question of the composition of Russian inks in the medieval period is most simply characterized by the words of the most authoritative of our (Russian) paleographers. There are almost no disagreements or doubts here to date.

The creator of the earliest course on Slavonic-Russian Paleography, I. I. Sreznevskiy, speaks to this question categorically: “the ink used for writing books was always one and the same as in Byzantine Greece, that is, iron-based.”[7]Akadem. sborn., vol. XII, no. 1, p. 5. It is true that, in another place, while discussing the late 13th-century Galician Gospel, he notes that it was written “in ferrous inks which seem to have been mixed with soot.”[8]Sved. i zametki, vol. LVIII. This concludes his observations on the quality of inks.

The compiler of the most thorough and complete of modern courses, E.F. Karskiy, writes: “the composition of medieval inks is not known for certain, as no chemical study has been conducted. In any event, they were quite good inks, for the most part strong in solution, which penetrated deeply into parchment, and viscous, drying on the surface of the page in a thick layer. The assumption is that they were metallic inks, most likely ferrous. These inks were quite durable, as they have quite clearly survived to modern day, over the course of many centuries.” Further discussing I.I. Sreznevskiy’s observation on the inks in the Galician Gospel, Karskiy concludes: “regarding the inks from the later period (for example, the 17th century), it is worth noting that they were of the same composition as were used in the not-so-distant past in Russia, and are sometimes used even now.”[9]Karskij, E.F. Ocherk slavjanskoj kirillovskoj paleografii. Warsaw, 1901, pp. 120-121.

In his work Slavonic-Russian Paleography, A. Sobolevskiy writes: “The inks used in medieval Russian and South-Slavic manuscripts have to date not been studied, but one can hardly doubt that their composition in medieval times was generally the same as in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries.”[10]Sobolevskij, A. Paleografija. 1906 ed., p. 43.

In one of his textbooks on paleography, V. Schepkin, repeating in general the same as had been said by the previous authors on Russian and South Slavic inks, adds that: “In western paleography, observations have been made that the shade (and subsequently the composition) of inks can differ markedly by time and country.”[11]Schepkin, V.N. Uchebnik russkoj paleographii. 1910 ed., pp. 25-26.

Such unanimous opinions by the scholars of our young but already well-defined science, apparently deprives of any interest the question of the study of the composition of medieval Russian inks. The extreme importance, however, of inks as one of the most important paleographic indicators nevertheless led us to the idea of reviewing this subject anew, with a point of view which is not always available to scholarly philologists, namely from a technical-chemical point of view. In this light, as it seems to us, there is much to be gained, promising even more tempting perspectives.

In the depths of antiquity, when the various types of graphic arts had not yet had time to become differentiated, the primary, if not only, blackening substance was coal. Atramentum, or ink, was also used as a substance for depicting written signs, and was used as well for various other needs. With the separation, on the one hand, of the writing arts into an independent branch of art, and on the other hand, with the development of various artistic techniques, the technology of preparing inks and their composition changed as well. Memories of these universal inks were long preserved, even after the process of differentiation had been completed.

Artists from the time of Pliny and Vitruvius created ink – atramentum – from coal, wine residues, fruit seeds, soft species of wood, soot, and burnt bone. Pliny declared the best ink to be made from soot which had been created especially for this purpose. Writing ink was made from soot and resin.[12]This is followed by a description of a device used for creating soot.

Many centuries later, Heraclius listed the exact same materials. He also especially preferred ink made from specially prepared soot. This ink, he writes, “is necessary not only for painting needs, but also for everyday writing.”[13]Late 11th or early 12th century. It seems that he was unaware of any other kinds of writing ink, aside from soot-based ink. Heraclius’s information, in light of his closeness to Byzantine culture, is of particular interest to us. The ink, incaustum, described by Theophilus, who lived close to a century later, is already of a different composition. This was, primarily, a broth made from the bark of oak galls (Lignum spinarum), which was condensed through boiling and drying in the sun, to which the older atramentum was still added, but only in small quantities. Writing ink made from this dark-colored bark concoction, even with at least some admixture of sooty atramentum, must be seen as a completely new type of ink.[14]In one of the later copies used for a Viennese edition of Theophilus’ work, at the end of the recipe for preparing atramentum, it says that if the freshly-prepared ink is not black enough, to “take a piece of iron, anneal it in a flame, and throw it into the ink.” This addition is interesting because, firstly, it confirms that there was no need for iron in the normal course of this operation; secondly, because it points to the rise of a new, transitional type of ink where iron, given a certain amount of tannins, acids, and time in the same solution, could play the role of blackening agent, as in ferrous ink.

A third type in the process of improvement of this culturally important substance was the ink we use today – ferrous ink.

The main difference between these three types of ink is that, at the base of each, there is a completely chemically-different substance. The use of soot mixed with an adhesive substance or rather sticky, dark-colored vegetable extracts for the writing of letters on parchment or paper, as well as the preparation of these inks, was relatively simple and self-explanatory, but the chemistry of so-called ferrous inks is significantly more complex.

The essential part of this last type of ink consists of ferrous salts of tannic or gallic acid. These acids are quite colorless in and of themselves, and as such, in a solution, they are able to leave behind on paper only a faint mark, which darken as they dry in air due to the formation of iron oxides. These differ from acidic salts in their insolubility in water and their resistance to fading in light, which gives ferrous inks their strength. Tannic acids are found in the bark of various tree species and in various plants, and are especially abundant in oak galls.[15]Growths on oak trees caused by insects. The formation of ferrous salts from metallic iron or its oxides in aqueous solutions containing tannins occurs in the presence of a certain quantity of free extrinsic acids, which is why in medieval times they would pour kvass, vinegar, sour cabbage, etc. The process was long and occurred best in warmth. In addition, given that, as we said, iron salts are almost colorless, and that at the time of writing, the writer would have difficulty making out what he had written, they would add and even today we still add to the ink some kind of dark, impermanent coloring. This addition would be unnecessary if, during the preparation of the ink, coloring somehow was already added; for example, brown dyes from alder bark would be added to the ink during the process of condensing its tannins.

While the paleographers of our time are well aware of the existence in antiquity of atramentum and later of ferrous inks, the question of the significance of inks which were prepared as well described by Theophilus and called incaustum in Latin or έγχαυστον in Greek, has to this day not only been resolved, but so far as we are aware, has not even been posed, although in recent years, attentive paleographers have started to turn their attention to the fact that ancient manuscripts were frequently written with some type of ink with characteristics which were completely different from soot- and iron-based inks. Our medieval Russian literary sources, as well as comparative study of the inks in our written works, pose the question about the existence, it seems, of a third type of ink, widely used in the Middle Ages, and distinctly called “boiled ink” by our scribes. In light of this, it would be not without interest to list here at least some data about the study of inks in modern Western European literature. We are unable to cover these sources with exhaustive completeness. Since the main blackening agent of these inks was tannins from the bark of various plants known today as phlobaphenes, modified through cooking and evaporation, we are able to call them phlobaphenic inks.[16]Certain tannins, which are in and of themselves colorless, are under known conditions capable of producing intensely-colored substances called phlobaphenes. Their process of formation is tied, it seems, to the formation of tannic acid anhydrides. It is possible, though, that oxidative processes caused by plant enzymes called oxides also play an important role.

Professor A.P. Laurie, having studied the pigments of 7th-15th century Byzantine manuscripts, speaks more specifically to this matter than other scholars of medieval manuscripts.[17]Laurie, A.P. The pigments and mediums of the old masters. London, 1914, pp. 63-64. He quite clearly noticed the presence on their pages of some special type of ink, which had faded to a bright, warm brown tone, and which was completely dissimilar to both soot-based and iron-based inks. He writes that it can be assumed that that this ink consisted of a semi-liquid bitumen. Without insisting, however, on this definition of their composition, he finds that the topic of this type of Byzantine ink is worthy of further study.[18]idem., p. 64: “This matter of the Byzantine ink is worthy of further enquiry and investigation.”

In the second edition of his excellent work,[19]Gardthausen, V. Griechiche Paleographie. Leipzig, 1911. Gardthausen connects the appearance of new types of ink among the Greeks to their transition from papyrus to parchment, to which soot-based ink adhered insufficiently well. This more durable material required a more durable pigment. He recognizes these medieval inks by their beautiful yellow-brown bronze color, but considers them to be ferrous inks which have faded over time.[20]idem., Vol. 1, p. 202 et. al. Unfortunately, as with many scholarly paleographers, he has only the faintest notion of the content of this ink.[21]He thinks that the iron contained in the ink came from the oak galls. “Man waehlte dazu Gallaepfel, wegen ihres Eisengehalts.” [“Gall apples were chosen because of their iron content.”] idem., Vol. 1, p. 205. Studying the recipe, he notes further that in antiquity there existed a special type of ink which required being boiled over a fire, called έγχαυστον, but doesn’t touch upon the question of exactly which technological necessities of preparation were used in this process.[22]idem., p. 207.

An Analysis of Mineral Inks.

We find particularly interesting the scholarly debate related to the analysis of remnants of ink in a bronze inkwell found during the excavation of a Roman fortification near Haltern, near Lippe. G. Kassner, having studied this ink in his laboratory, and having excluded from his analysis those substances which he considers to have ended up inside the inkwell by chance, found that the ink primarily consisted of some kind of undetermined burnt organic substances, partially soluble (25.3%) and partially insoluble (65.3%) in water and acid. In the same quantity, he found some soot (around 13%) and an insignificant quantity of some kind of aromatic resin, and it also seemed to him that he was able to prove traces of tannic acids which had not been degraded by time. The presence of some kind of apparently completely insignificant quantity of iron, which he did not more accurately determine (his original analysis found iron oxide together with alumina and phosphoric acid, totaling 3.5%), led him to the conclusion that the coloring agent of this ink was a ferrous salt of tannic acid, with an admixture of soot.[23]Kassner, Georg. “Ueber eine aus der Erde gegrabene Tinte aus der Roemerzeit.” Archiv f. Pharmazie. Vol. 246, p. 329; “Die Tinte der Roemerzeit von Haltern in W.” Archiv f. Pharmazie. Vol. 247, p. 150.

Objecting to this, Professor R. Kobert quite reasonably notes that, based on all surviving literary data, inks of this time could not have been ferrous. In checking Kassner’s analytical data, he was unable to find in them any sign whatsoever of tannins. He is only able to suggest, then, that this was a soot-based ink,[24]Kobert, R. “Ueber antike Tinte.” Arch. f. d. Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften u. d. Technik. 1909, vol. 1, p. 103. which, however, is contradicted by the insignificant percent of soot that was found.

In our view, this as-yet unresolved debate is clearly resolved. The pigment base for the Haltern inks was obviously made up predominantly of dark organic material, the precise composition of which has not yet been determined, condensed through evaporation from either Theophilus’ decoction from the bark of Lignum spinarum or of some other kind of plant, a substance which we call a phlobaphene. The presence of a certain amount of soot, visible under a microscope, only confirms our comparison of the result of the analysis of the Haltern inks with the directions from the Greek-Latin author. Iron is ubiquitous, and trace amounts of it, of course, cannot be excluded from any kind of ink. In this case, judging by its quantity, which is quite insignificant in comparison to organic material, the iron most likely ended up in the ink along with the alumina, phosphoric acid sand, etc. from the soil.

Having outlined three historical types of ink (atramentum, incaustum, and ferrous), let us turn to the question of Russian inks.

We do not know what the scribes of St. Vladimir and Yaroslav the Wise wrote with, but as with their art, it was doubtlessly tightly associated with Byzantine-Greek art, and as such, we must think that, along their path of improving inks, they likely did not surpass the Western artisan Theophilus, who worked in this area much later, and whose entire wisdom, as he himself writes in the introduction to his book, boiled down to a knowledge of Greek technology.[25]Theophilus, Diversarum artium schedula. Venice, Ilg. Their inks, therefore, were atramentum or incaustum.

Our literary data on the techniques of writing books, as has been said, are no older than the mid-15th century, that is, the time when ferrous inks had already long been in everyday use. Despite this, we still find in them surviving elements which fully confirm the hypothesis that the scribes of our Middle Ages were acquainted with both of these archaic types of ink, the first of which was called in Russian “smoked ink” (Rus. чернила копчёная, chernila kopchjonaja), and the latter called “boiled ink” (Rus. чернила вареная, chernila varenaja).

Particularly important and interesting in this regard is the testimony of Nikodim of Siysk, an artisan from the second half of the 17th century, and a compiler of a famous icon-painting sourcebook (Rus. подлинник, podlinnik) and technological manual, and whose articles all carry undeniable signs of his practical knowledge of the material.

Alongside the articles on the preparation of ferrous inks, he includes an article “On the use of smoked inks for iconographic and book writing.” Having described the preparation of soot using household equipment and its collection “for use in icons,” he writes:

мощно и не тертой бумаге быть про книжное письмо, тож сажу на вине или на слине сначала малу смесив, потому воды присовокупив, натерши сдоволу и на потомок. А сколько на письмо належимое надобно отлучив то число, и прибавить комеди и утерти нагуста довольно по удобству, и вложить в кубышку из нея писать и развести по угожеству приливом и писать что волишь. А буде лучше похошчешь быть чернилу, згустным приливом, попарить чернильных орешков, толченых в платье, и тем приливом приливай в чернило. А иншия (чернила) с чернильным приливом, квасного сусла тож число, да толченых чернильных орешков и мало неголныя серы, сиречь лиственницы и железа прибавить смесив купно вложить в кувшинец не малой обвязать плотно поставить в тепло с продолжением, чтобы закисло, потом верх снять сиречь плесень. Лучше сего не бывает прилива. К тому комедь не надо.[26]Simoni, P., ed. “Rukopisnyj Sijskij ikonopisnyj podlinnik, Bibl. Arkhangel’skoj dukhovnoj seminarii.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 213.

And in order[27]jeb: мощно > можно. to write on stiffened paper, having first mixed the soot with a little wine or saliva, and having thus added water, grind it well and long. Having obtained however much [soot] you will need for writing, take that amount, add resin, and having ground it to a convenient thickness, put it into a cup from which to write, and dilute it as necessary with priliv,[28]By the word priliv (Med. Rus. прилив), the author apparently means a decoction of alder bark, the preparation of which he describes in detail in the previous article: “On priliv,” following folio 20.[29]jeb: Sreznevskij offers no translation for the word приливъ, but it clearly is derived from the verb приливати meaning подливать, доливать, прибавлять “to pour,” “to top up,” “to add”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja Slovarja Drevne-Russkogo Jazyka po Pis’mennym Pamjatnikam. Vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 1422. and write whatever you wish. And if you want the ink to be even better, a form called “thick priliv“, steam some oak galls which have been crushed within a piece of cloth,[30]jeb: платъ meaning кусок ткани, “a piece of cloth”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, p. 955. and then pour that priliv into your ink. For a different ink made with oak gall and priliv, add the same amount of kvass wort, and crushed ink galls, and a little bit of crushed resin,[31]jeb: сѣра = сѣрра, meaning смола, “resin”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja Slovarja Drevne-Russkogo Jazyka po Pis’mennym Pamjatnikam. Vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1912, p. 899. that is, from a larch, and iron, and having mixed it all together, place it all into a large jug. Close it tightly, and place it for a long time in a warm place until it sours, then remove the top, that is, the must. There is no better priliv than this. One need not add resin to it.

Historically deciphering the monk Nikodim’s recipe, we easily note the process of layering its oldest core with newer ideas. Having prepared his “smoked ink” (aka atramentum) made of soot and resin (cerasin – Rus. вишнёвый клей, vishnjovyj klej, “cherry gum”) according to the same rules used by Greco-Byzantine art of the 10th century, instead of using it as it would have been previously used, he suggests diluting it first with one of three forms of priliv. The first of these, a decoction of alder bark described in the previous chapter “On priliv,”[32]Simoni, op. cit., p. 212. is analogous to the Latin-Byzantine incaustum maded from the bark of Lignum spinarum; the second, which he calls “thick priliv,” is a decoction of crushed oak galls without any admixture of iron, and in effect belongs to the same type of ink. Only the third type of priliv, which he calls “oak gall priliv” (Rus. чернильный прилив, chernil’nyj priliv), contains iron and is in fact fully suitable for use as a 17th century ferrous ink with all of the characteristic traits of its preparation: kvass wort, prolonged storage in a warm place, etc.

Aside from Nikodim of Siysk’s prilivy, evidence of the use in Russia of the second archaic type of ink, incaustum or boiled ink, which did not initially contain any iron, can be found in many recipes. These are especially apparent among the earliest of our authors, a southern Russian scribe from the mid-15th century. After his directions on the creation of oak gall ink, he provides the following:

Како варить чернило. Часть дубовые коры, другая ольховые, полчасти ясеневые и сего наклады полон сосуд железен или глинян, и вари с водою дондеже искипит вода мало не вся, и уставшую часть воды влiй в сосуд опришнiй, и паки налив воды вари такоже, и сице сотвори до трикраты, наклады свежiе коры и потом вари без коры еже еси излiял во особый сосуд, а вложи жестылю в плат завязав и донелиже на жестыли тело все искипит, токмо кости останут в плату, и железину вложи и мешай на всякый день, и держи в тепле, а на третiй день пиши.[33]Simoni, P., ed. “Rukopis’nyj sbornik bibl. Troitse-Sergievskoj lavry.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 17.

How to boil ink. Take one part oak bark, one part alder bark, and a half part ash bark, and layer these into a vessel of iron or clay until full, and boil with water until not quite all of the water has boiled off, then pour this infused water into a second vessel, and having poured in the water, boil it again the same way, and repeat up to three times, adding fresh bark and then boiling again without any bark each time, then pour this liquid into another vessel, and add buckthorn berries tied up in a piece of cloth, and boil the berries until only the “bones” [the skins] remain in the cloth, then add iron and stir for an entire day, and keep in a warm place, and on the third day, write.

The oldest and main part of this recipe talks about the decoction of the bark of three species of tree containing extractives, followed by evaporation of the broth without any bark, with the goal of causing it to thicken and turn black. Theophilus does the same with his bark of Lignum spinarum. This decoction of Russian tree bark, however, seems to have been insufficiently colored in order to serve as ink. This intensification was achieved by steeping alder buckthorn berries in it “until their bodies boil.”[34]The zhastyl’ (Rus. жастыль, жестыль) mentioned appears to be the same as Rhamnus (Rus. Жостер, Zhoster), a genus of plants in the Buckthorn family. Buckthorn berries contain colorants, which is why they are so frequently used in dyeing. This last step is, in fact, where the preparation of boiled ink ends.

The last part about iron is of a later origin. Over the course of three days, under these conditions, iron would not have been able to create a large quantity of salts, and the quality of the ink would have depended on the colorants from the bark and berries. Despite the presence of iron, this ink nevertheless remains a typical “boiled ink” or incaustum. This Russian incaustum was not evaporated to complete dryness, as was done in Theophilus’ time, but mention of such inks in Russia in the late 16th century have been preserved. These were called “stored ink” (Rus. запасная чернила, zapasnaja chernila, from запас, zapas, “storage’). One of two recipes[35]In those cases which talk about the creation of ferrous ink, as can be seen from the recipes below, they use substances which are richer in tannic acid, strongly acidify the solution, include not one but many pieces of iron, and allow them to stand for much longer. reads:

Запасное ж чернило инем образом сице творити, сухое. В сковороду дондеже будет густо аки тесто и тогда в бруски сбивай.

How to make stored or dry ink by another method. In a pan, [boil it] until it is thick like dough, then knead it into bars.

On the creation of ferrous ink, starting in Russia in the 15th century, a most extensive recipe is indicated. Within this type of ink, several stages can be noted on the path of development. We begin with a general description of the materials and methods used in this production.

The iron needed for the formation of ink was originally introduced by immersing into the solution metal in the form of so-called uklad (Med. Rus. укладъ, “raw steel”) or oblong plates of iron (Med. Rus. огнивъце, ogniv’tse)[36]jeb: огнивъце = diminutive of огниво (ognivo), meaning “the cross-piece of a sword hilt”; cf. Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, p. 603. equipped with holes such that, once strung on a lace, it would be easier to submerse and remove them from the solution. These “irons” had several names. Instead of these, often they would use simply old “spare iron,” “locks and keys, broken pieces, or chains, cut into bits,” as is listed by one artisan from the 16th-17th centuries.[37]Simoni, P., ed. “Ruk. sborn. Publ. bibl., XVII.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 39. Some artisans added iron “clean of any rust,” while others preferred “deliberately rusty iron” or even iron scale knocked free by a blacksmith’s hammer, called “blacksmith iron” (Rus. железина кузнечная, zhelezina kuznechnaja) or even “forge slivers” (Rus. треска от кузницы, treska ot kuznitsy).[38]jeb: “трѣска = треска” meaning “sliver”, Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1027. Sometimes they even added the mud from under a grindstone, which would contain iron dust or particles from the tools sharped upon it. The iron was consumed slowly in the formation of ink, which is why large pieces of it needed to lie for a long time at the bottom of the vessel used to prepare the ink, along with roughly crushed oak galls, forming a so-called “ink nest” (Rus. чернильное гнездо, chernil’noe gnezdo), to which new priliv would be added. Such a “nest” would last “up to seven or ten years.”[39]Simoni, “Ruk. sborn. Publ. bibl., XVII,” p. 38. As one ran out of ink, it was replenished by adding fresh priliv.

The reactions which form ferrous salts require the presence of acids. For this purpose, liquids containing acid were added: sour cabbage soup, honey kvass, or simple “strong honey vinegar,” or liquids which once fermented would become acidic: “vulgar” or raw honey, barley beer, suloy (Rus. сулой, a slurry of water mixed with flour or sourdough), or plain wine. When, over time, these fermentable substances were consumed and the ink became sweet, which was easily checked by tasting it, then, according to the apt expression, they were “topped up” with raw honey, giving new food to the fermenting enzymes.[40]Some artisans, afraid to top up the ink with liquids which were not yet sufficiently fermented, or which contained sugary substances that would dry poorly, specify:

Доливать комедью или вином горячим или медвяным квасом стоялым. А патоки и медвяного нового квасу отнюдь в чернило не класть, занеж становятся не черниле лоск злой и писанное лист с листом сливается бедно.

Top up with resin or heated wine or with standing honey kvass. But by no means add molasses or new honey kvass, for an evil gloss will arise in the ink, and anything written will transfer from one page to another undesirously.

Simoni, P., ed. “Ruk. Mosk. sinod. bibl., No. 871-521.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 110. The specified acids achieved using a sugary alcohol solution degrade once they are converted into carbon dioxide by acetic bacteria. The vessel containing the ink was placed in a warm spot, and the contents were stirred several times a day. This process was slow. The production of ink required from 12 days up to a month. In order to moderate the fermentation and prevent the development of mold, a little hop brine was sometimes added to the mixture. Most often, resin or cerasin was added to the ink “for support” if the ink “wandered through paper.” Less frequently, we see alum, ginger or cloves added to help the ink flow:

Кладут в чернило инбирь и гвоздику, а чернила с пера не пойдут, класть гвоздику тертою и от гвоздики хотки будут… а с пера не побежат, то квасцей положити.[41]The clove protects ink containing resin and other organic substances from decay and the formation of mucilaginous compounds. Clove oil is still used in modern times for the same purpose.

Ginger and clove are added to the ink, and if the ink will not flow from the quill, add grated ginger and the ink will be good[42]jeb: I’m basing this translation of хотки (Med. Rus. khotki) on several related words (хоть, хоти, хотъный), cf. Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1389.… and if it will not flow from the quill, then add some alum.

Instead of iron, or quite frequently in addition to it, iron(II) sulfate (Rus. железный купорос, zheleznyj kuporos) later started to come into use, also called green vitriol, blackening vitriol, or cobbler’s vitriol[43]This was because cobblers used it when blackening tanned leather goods. (Rus. купорос зелёный, купорос чернящий, купорос сапожный). It was usually burned before use, or more correctly, heated slightly, then wrapped in paper[44]Here, the green crystals of iron sulfate, losing their crystallization water, turn into a white powder. The meaning behind this step is not completely clear. Undoubtedly it was adopted along with the use of vitriol from Western artisans, who also added powdery vitriol which had lost its crystallization water when preparing ink. until the crystallization water evaporated, and the crystals turned into a white powder. The addition of vitriol significantly accelerated the preparation of ink, allowing it to be prepared in a single day.

These are the several typical recipes for preparing ink. Aside from the archaic methods mentioned above, we present one frequently repeated method of boiling ink from bark using iron:

Первое устругав зеленыя корки ольховыя без моху молодыя и в четвертый день положить кору в горшок и налить воды или квасу добраго или сусла яшнаго, а коры наклады полон горшок и варить в печи, и гораздо бы кипело и прело довольно бы день до вечера, и положи в горшок железины немного, и поставить горшок совсем, где бы место ни студено ни тепло, а на третiй день разлити чернило.

Приготовить сосуд кукшин и в нем железо обломков старых мечи довольно или от кузнеца трести, завязав в плат впусти в горшок сусло чернильное процедить сквозь плат и налить кукшин полон, и сосуд заткнув поставить в сокровенное место на 12 дней. То есть скорое оное и книжное чернило.[45]“Ikon. podl. Publ. bibl. im. Lenina, No. 1463.” Publichnyj vestnik izjaschnykh iskusstv. 1887 (4), p. 563. Povtorenija sbornika poloviny XVIII v., Istor. muzej, Moskva, No. 1288, p. 40. in Rukop. sborn. nach. XVIII v. arzamasskogo diakona Feodora, prepared for publication by P. Simoni.

Having first arranged the green bark of young alder trees without moss, on the fourth day, place the bark into a pot and pour water or good kvass or barley[46]jeb: ꙗчьныи meaning ячменный, “barley”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1676. wort, and with the pot full with the overlaid bark, cook it in the oven, and let it boil and work [47]jeb: прѣти = пьрѣти meaning вести дело, “transact business”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, pp. 1705, 1774. for a full day until evening, and add a little iron to the pot, and place the entire pot in a spot which is neither warm nor cold, and one the third day pour out the ink.

Prepare a jug,[48]jeb: кукшин > кувшин, “jug”. and place(?) in it iron fragments of a very old sword or from a blacksmith, having tied them up in a cloth, and let the ink wort in the pot strain through the cloth, and pour until the jug is full, and having stoppered the jug, place it in a secret location for 12 days. And then it will quickly become[49]jeb: оныи meaning тот, будущий, “there, to-be”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, pp. 674-675. ink for writing.

Along with boiled ink, the oldest of our manuscripts includes the directions for preparing oak gall ink.[50]The term “oak gall placement” (Rus. чернильное ставление, chernil’noe stavlenie) typically means the preparation of oak gall ink. This ink is brewed from the bark, cf. for example, Simoni, op. cit., p. 336, early 18th century: “Память как чернило ставити” (“On the preparation of ink”), as well as “Их указ чернило варить” (“Directions for brewing ink“).

Сице чернильное ставление елико будет орешков и та клею всвеси вишневого противу орешков, да противу обою орешков и клею восвеси меду преснаго да клей намочи в меду в кислом в добром за две недели или доле до ставления, чтобы взнило яко дрождiе. По югноенiи клею возьми добраго меду кислаго, да стольки орешки мелко и с том просей, да лей на орешок меду кислаго по три яйца, да и клей туто же смешай, да и мед пресный, да приготовь укладов или желесца 12 продолжи единако, яко в сосуд вместити на дне, да почини на концах дыры, да на вервь возниши, занеж добро тй имати вон, да поставь в тепле и не мози застудить дондеж ушишут. А мешай на всяк день по трижды, а цеди трижды доколе устоят, а хоть устоять, а ты держи в тепле, да приимут языком чтобы недобре сладки были, сладость бы вольная, а будет и мака не слышати сладости, и ты подкармливай медком пресным, а стави их молода (месяцы 3-й день).[51]Ikon. podl. Troitse-Serg. lavry, No. 408-1245.

To prepare oak gall ink, take a number of oak galls, and add cherry resin to the galls, and to both the galls and the resin add fresh mead, and soak the resin in good sour mead for two weeks or a fraction thereof, until it begins to tremble.[52]That is, it bubbles from fermentation. While crushing(??)[53]jeb: угнѣтати meaning теснить, задавливать, “to squeeze,” “to crush”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1134. the resin, take some good sour mead, enough to cover the galls, and stir them together, and pour onto the galls three eggs of sour mead, and mix them al together, and add raw honey, and prepare 12 pieces of steel[54]jeb: укладъ meaning сталь, “steel”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1178. or iron in the same way, and place them at the bottom of the vessel, having pierced holes into their ends, and hang them on a string so that it will be convenient to remove them, and place [the vessel] in a warm place and do not allow it to get cold. Stir it thrice daily, and on every third day as it is standing while keeping it warm, test it with the tongue to see if it is terribly sweet, if it is sweet then leave it, but if it does not taste sweet, then top it off with raw honey, and set it on a young month, on the third day.

The note that the ink should be set in the first few days of a young month, often repeated, appears to be a rudimentary remnant of an old rule to let the ink sit in the “nest” for no less than that amount of time before its use. To make this easier to remember, it was always set out at the same time according to the lunar calendar. In a German recipe from the first half of the 18th century, this rule was preserved completely: “… und in dem letzten Viertel des mondes faenget man die Tinte anzumachen, so wird sie fertig in dem zunehmenden Monde des ersten Viertels.”[55]jeb: “…and the ink is caught in the last quarter of the moon, and it is finished in the waxing moon of the first quarter.”[56]Where exactly V.A. Schavinskij discovered the aforementioned quote is not mentioned in his notes. M.F.

P. Simoni mentions in his footnotes (p. 16) an interesting statement from the article “Powerful Lunaria” (“Сильный лунник”) (in a manuscript from a Novgorod cathedral, collection no. 1462 from the Kirill-Beloozersk Monastery) which, unfortunately, was incompletely published, where among other things it mentions a time that is “добро кровь пущати и чернило ставити” – “good for letting blood (?)[57]jeb: пущати meaning напускать, разрешать, отгонять, “to let,” “to allow,” “to drive away”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, pp. 1743-1744. and preparing ink.”

In those cases which used both bark and oak galls, the process became significantly more complicated. It was necessary at first to prepare a decoction from the bark, and then to let it sit in the “nest” with iron and galls.[58]The bark could be replaced with blueberries. A single “Recipe for Blueberry Ink” (“Указ о черниле черничном”) was preserved in a manuscript from the 16th-17th centuries.

Первее положити в котел две доли ягод черницы и третiю воды, лий штей кислых, и вываря то паки приготовь и третiе, потомуж приложа варити, что останется процедити в скудельник выжав ягоды. Положити в него железа ржавчивого, орешков и патоки по мере повязать платом впятеро и даты стоять до двою на десять дней. Потом же помешивать по вся дни до дваю на десять днiе, пытати потом пером.

First place in a cauldron two parts blueberries and one part water or sour cabbage soup, and boil this, and then third, boil what remains after pressing the berries in a clay pot. Add some rusty iron or oak galls to this liquid, having first tied them up in a piece of cloth, and let it sit for two and ten days. Then stir it all day long for two and ten days, and then test it with a quill.

An analogous recipe starting with the words “boil some tough krutik in water, so that the dyes color it” (“в воде варить краску крутик, что крашенины красят”) and so forth, is unclear, since krutik, or indigo, does not dissolve in wine[jeb: sic] and could not provide any benefit to ink.

In the 17th century, iron sulfate started to enter into general use. It provided the ability to significantly simplify and accelerate the process of preparing ink, but this property was unknown for a long time. It was simply added to the “nest,” along with metallic iron, without attempting to shorten the standing period, or at least, having cooked the ink in the previous manner, they began to cook it a little longer using this new addition. The process of development for this new method is clearly seen, for example, in the following “Directions for boiling ink” (“Указ чернило варить”) from the 17th-18th centuries:

Ольхи было бы много да котел большой налити воды полон, а иные бы воды не прибавливать и поварив, да иная ольха в туж воду и положити и не одинока класти ольху да под точилом взяти железины, да высушить да столчи, да в платы положити в чернило и как постоит неделю или две на гнезде, сколько надобно чернил положити в горшочек и на сковороду, да тутож клею толчёнаго и орешков с купоросом и как упреют да процеди, то и книжное чернило. А железина из чернила вынять, чтобы чернило бумаг не проедало.[59]V.A. Schavinskij’s manuscript does not provide any indication where he discovered this text. M.F.

Place a large amount of alder into a large cauldron and fill it with water, and if you top off the water which has boiled, then add more alder, but do not add more alder by itself; and take some of the iron from under a grindstone and dry it, and wrap it in a piece of cloth and place it in the ink and let it sit for a week or two in the nest; then take however much ink you need and place it in a pot or frying pan, and add crushed resin and oak galls and iron vitriol, and stir(??)[60]jeb: ꙋпрѣти = ꙋпьрѣти meaning победить в споре, доказать вину, “to win an argument,” “to prove guilt”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1251. and strain it, and it will be ink for writing. But remove the iron from the ink, lest the ink eat through the paper.

The correct use of iron sulfate, using it to replace the “iron plates,” began in the second half of the 17th century. In a recipe from this time, “On the hasty preparation of ink” (“О чернилах же зделать на скорую руку”), it says:

Взять чернильних орешков и разбив на мелко, полить сулоем и да стоет неделю, как орешки размокнут и не протцедить положить еще надо сапожнаго купоросу, прибавляя камедь заварить, и протцедить. Будут добрые чернила.[61]P. Simoni, ed. “Rukop. podl. ikon., Rukop. otdel. bibl. Akad. nauk, 45, 10, 1.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 226.

Take oak galls, and having smashed them to bits, add suloy and let it stand for a week, such that the nuts remain wet, and without straining them, you must also add some cobbler’s vitriol, and having added resin let it brew, and then strain it. It will be good ink.

It is interesting to note that nearby in the same manuscript, there is saved another recipe:

О чернилах же. Чернила делать что пишут. Наскобли вольхи молодой, да чешуи железной и варить в сусле гораздо и процедить и поставить на печь, и квасить неделю з две железом.

On ink. How to make ink that writes. Scrape some young alder and some iron scales and boil them well in wort, and filter it and place it on an oven, and let it ferment for a week with two pieces of iron.

Here, the principle of the first part of the aforementioned double recipe is still preserved in its pure form, as an independent method.

Contrasting these three recipes illuminates well the process of adoption of this new technological method along with older technology.

The influence of the West on the acceptance in Russia of this new method of producing ink can be seen in the names of the ink itself, which was sometimes called “German” ink. The article “German-style Ink” (“Чернил немецких пропорция”), already completely devoid of older vestiges in the form of bark, iron, cabbage soup, mead, hops, etc. was written in an early 18th century manuscript:

Три золотника орешков, три золотника купоросу, все сие стереть на мелко и положить в сосуд стеклянный, да взять воды горячей по пропорции, влить во все, дать устоять на сутки, и действуй.

Take three zolotniks[62]jeb: Rus. золотник, a Russian measure of weight equal to about 4.26 grams. of oak galls, three zolotniks of iron sulfate, and grind all of this to powder, and place in a glass vessel, and pour the same amount of hot water over all of it, and let it stand for a day, then then go to work.

This new kind of ink quickly became widespread and everyone started to like it. It was often mentioned as “good ink” (“чернила добрыя”).

In Ukraine, oak-gall and iron sulfide ink appeared even earlier. A Northern manuscript form the second half of the 17th century borrows from there, speaking about it with great praise in “Directions for ink made without resin” (“Указ о чернилах, что делать их без камеди”), calling it “the very best, the Kievans write with it” (“самые добрые, что пишут ими кiевляне”):

Орешки чернильные разбить не мелко и положить в кляницу и налить воды пополам. Воды было выше пальца, и поставить в теплоту и подержать будет в жару час, чтоб выкипело на палец, и воду слить, положить купоросу сапожнаго по мере, а купорос сушить на огне на бумаге над свечою, а вина простого 4 доли прибавить.

Do not smash the oak galls too finely, and place them in a clay pot, and pour in a measure of water. The water should be more than a finger deep, then place the pot in a warm spot, and hold it in the fire for an hour so that the finger’s worth of water boils off, then pour off the remaining water, add one measure of cobbler’s vitriol, having first dried the vitriol in paper over a candle flame, and add four parts of simple wine.

It says further: “This is the best” (“сие всего лутче”).

Serbian scribes from the second half of the 17th century prepared their “black ink” (“чорно мастило”) nearly the same way, not forgetting to add only a certain quantity of resin. This can also be said about “German ink.”

It is interesting to note that our conservative scribes, having adopted the use of iron sulfide, appear not to have decided to make use of it for coloring their writing ink, which was still achieved using tree-based dyes, the properties of which they were well acquainted. Meanwhile, in the West, a decoction of brazilwood was frequently used in writing ink.

The data which we have provided seems to us sufficient to dissuade us once and for all from the thesis posited by the authoritative scholars from the end of the previous century, namely that in Russia, “the ink used for writing was always one and the same as used in Byzantine Greece, that is, iron-based,” a position which influenced, as we have seen, many other modern-day scholars. Looking again with out any preconceived notions at the ink used in our manuscripts, we do not at all get this impression of monotony, which would have been a hopeless cause for paleography. First of all, quite strikingly, was the example provided by the same venerable scientist from the 13th-century Galician Gospel. This Gospel, written in a deep black, smooth, matte ink, can really serve as a great example of writing with soot-based or, as they were called in Russia, “smoked” ink.[63]Simoni, P. “Rukop. Gos. Istor. muzeja v Moskve, No. 2126.” Prepared for publication. There is no basis whatsoever to assume, as I.I. Sreznevsky thought, that the ink in the Galician Gospel contains iron. It is very likely that this is pure soot-based or “smoked” ink.

Possessing the quite undeniable testimony of a famous artisan from the 17th century that “smoked ink” was used in his day for book writing, and even the precise instructions used at that time for their preparation, we, of course, are now deprived of the right to assert that soot was not used in inks through the end of that century. We are able to make an analogous conclusion, based on this testimony and others which support these considerations, regarding the content of iron in ink.

Further, we now have no doubt that our artisans were familiar with a second type of ink, incaustum or “boiled ink,” or as we now would call it based on its content, phlobaphenic ink. Based on our data, we are able to make out two different types of ink within this group: ink whose coloring was based solely on phlobaphenes, and those to which were also added various plant-based dyes, such as rhamnetin from buckthorn berries. It is possible that both these types differ from one another even to the eye to more or less degree by their yellow shade. Just as in phlobaphenic ink, one of the constituent parts of ferrous ink, tannins, is present, the formation here of a certain quantity of iron salts is more likely than it was in soot-based ink. The presence of a small quantity of iron is not, of course, characteristic of ink which had coloring agents based on other pigments.

Becoming familiar with the numerous methods for preparing the third type of ink, the ferrous type, we can be sure that these methods led to different results in terms of the composition of these inks. Everywhere along with tannins, forming ferruginous salts, they contained other coloring agents of a different composition. Moreover, it must be assumed that their character was also influenced by whether they were prepared by prolonged standing on a “nest” of stacked iron strips, or if they were prepared “quickly” through the addition of iron sulfides.

In reality, carefully examining our medieval manuscripts, we can be certain that the predominantly brownish color of the ink comes in a variety of different brown shades, from an almost completely neutral-gray to rust-red and dirty yellow; we note that the ink had a more or less opaqueness, that the ink lay down either everywhere in the same way, or due to unevenness gave the writing a quite variegated look; that it dried sometimes maintaining a noticeable relief, sometimes without any relief at all; that the writing sometimes seems matte, sometimes shines with an oily sheen, or that it sometimes soaks through the paper and in other cases is imprinted on the surface of adjoining pages.

Further, we have seen that absolute black (without any shading), well-covering ink is found not only on the parchment of the aforementioned 13th-century Gospel, but also on much later paper manuscripts such as, for example, that commonly used on Pomor’ye manuscripts from the 18th century. Both of these types of doubtlessly different ink are completely impossible to discern by eye. After systematic study of our vast quantity of source material from our depositories of books and antiquities, the list of these visual signs might be easily increased significantly.

Attentive study of ink, even if with the assistance of a loupe and a permanently established color scale, would doubtless turn out to be very useful for paleography. Our acquaintance with their chemical composition, however, does not allow us to stop at the collection of visual signs. The microscope and microchemical analysis would provide us with dana of a different order, accurately and categorically defined, which, in terms of their scientific value, could hardly be compared with much of the data hitherto collected by our paleographers.[64]The development of techniques for determining the varying contents of ink could also be useful in yet one more regard. Being familiar with the chemical properties of their various component parts, we could expect to discover the methods for restoring texts of our oldest manuscripts, damaged by time, such as those which are found in our vaults in not small numbers. (In our day, similar work has been taken up in the laboratory of the Institute of Historical Technology of the State Academy of the History of Material Culture with great success. M.F.).

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Reported by the renowned expert of Old Believer writing, V.G. Druzhinin. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | On the prevalence of writing in medieval Rus’, cf: Sobolevskij, A.I. Slavjano-russkaja paleographija. Chapter 1. St. Petersburg, 1908. |

| ↟3 | Schepkin, V.N. Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1921, p. 11. jeb: see my translation here: https://rezansky.com/old-slavonic-and-the-slavonic-alphabets/ |

| ↟4 | In a Pskovian Book of the Apostles from 1307, there is the following note: “I wrote this with a peahen quill.” |

| ↟5 | Sobolevskij, op. cit., p. 16. |

| ↟6 | A manuscript collection of various articles from the 16th-17th centuries, Pub. Lib. XVII, no. 17. Published by P. Simoni in Памятники древней письменности и искусства [“Works of Medieval Writing and Art”], vol. CLXI. These publications by P. Simoni, which are excellent in terms of their scientific accuracy as well as the previously unpublished collection of antique texts which they kindly provide, will serve as the primary material for our further study. |

| ↟7 | Akadem. sborn., vol. XII, no. 1, p. 5. |

| ↟8 | Sved. i zametki, vol. LVIII. |

| ↟9 | Karskij, E.F. Ocherk slavjanskoj kirillovskoj paleografii. Warsaw, 1901, pp. 120-121. |

| ↟10 | Sobolevskij, A. Paleografija. 1906 ed., p. 43. |

| ↟11 | Schepkin, V.N. Uchebnik russkoj paleographii. 1910 ed., pp. 25-26. |

| ↟12 | This is followed by a description of a device used for creating soot. |

| ↟13 | Late 11th or early 12th century. |

| ↟14 | In one of the later copies used for a Viennese edition of Theophilus’ work, at the end of the recipe for preparing atramentum, it says that if the freshly-prepared ink is not black enough, to “take a piece of iron, anneal it in a flame, and throw it into the ink.” This addition is interesting because, firstly, it confirms that there was no need for iron in the normal course of this operation; secondly, because it points to the rise of a new, transitional type of ink where iron, given a certain amount of tannins, acids, and time in the same solution, could play the role of blackening agent, as in ferrous ink. |

| ↟15 | Growths on oak trees caused by insects. |

| ↟16 | Certain tannins, which are in and of themselves colorless, are under known conditions capable of producing intensely-colored substances called phlobaphenes. Their process of formation is tied, it seems, to the formation of tannic acid anhydrides. It is possible, though, that oxidative processes caused by plant enzymes called oxides also play an important role. |

| ↟17 | Laurie, A.P. The pigments and mediums of the old masters. London, 1914, pp. 63-64. |

| ↟18 | idem., p. 64: “This matter of the Byzantine ink is worthy of further enquiry and investigation.” |

| ↟19 | Gardthausen, V. Griechiche Paleographie. Leipzig, 1911. |

| ↟20 | idem., Vol. 1, p. 202 et. al. |

| ↟21 | He thinks that the iron contained in the ink came from the oak galls. “Man waehlte dazu Gallaepfel, wegen ihres Eisengehalts.” [“Gall apples were chosen because of their iron content.”] idem., Vol. 1, p. 205. |

| ↟22 | idem., p. 207. |

| ↟23 | Kassner, Georg. “Ueber eine aus der Erde gegrabene Tinte aus der Roemerzeit.” Archiv f. Pharmazie. Vol. 246, p. 329; “Die Tinte der Roemerzeit von Haltern in W.” Archiv f. Pharmazie. Vol. 247, p. 150. |

| ↟24 | Kobert, R. “Ueber antike Tinte.” Arch. f. d. Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften u. d. Technik. 1909, vol. 1, p. 103. |

| ↟25 | Theophilus, Diversarum artium schedula. Venice, Ilg. |

| ↟26 | Simoni, P., ed. “Rukopisnyj Sijskij ikonopisnyj podlinnik, Bibl. Arkhangel’skoj dukhovnoj seminarii.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 213. |

| ↟27 | jeb: мощно > можно. |

| ↟28 | By the word priliv (Med. Rus. прилив), the author apparently means a decoction of alder bark, the preparation of which he describes in detail in the previous article: “On priliv,” following folio 20. |

| ↟29 | jeb: Sreznevskij offers no translation for the word приливъ, but it clearly is derived from the verb приливати meaning подливать, доливать, прибавлять “to pour,” “to top up,” “to add”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja Slovarja Drevne-Russkogo Jazyka po Pis’mennym Pamjatnikam. Vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1902, p. 1422. |

| ↟30 | jeb: платъ meaning кусок ткани, “a piece of cloth”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, p. 955. |

| ↟31 | jeb: сѣра = сѣрра, meaning смола, “resin”; Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja Slovarja Drevne-Russkogo Jazyka po Pis’mennym Pamjatnikam. Vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1912, p. 899. |

| ↟32 | Simoni, op. cit., p. 212. |

| ↟33 | Simoni, P., ed. “Rukopis’nyj sbornik bibl. Troitse-Sergievskoj lavry.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 17. |

| ↟34 | The zhastyl’ (Rus. жастыль, жестыль) mentioned appears to be the same as Rhamnus (Rus. Жостер, Zhoster), a genus of plants in the Buckthorn family. Buckthorn berries contain colorants, which is why they are so frequently used in dyeing. |

| ↟35 | In those cases which talk about the creation of ferrous ink, as can be seen from the recipes below, they use substances which are richer in tannic acid, strongly acidify the solution, include not one but many pieces of iron, and allow them to stand for much longer. |

| ↟36 | jeb: огнивъце = diminutive of огниво (ognivo), meaning “the cross-piece of a sword hilt”; cf. Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, p. 603. |

| ↟37 | Simoni, P., ed. “Ruk. sborn. Publ. bibl., XVII.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 39. |

| ↟38 | jeb: “трѣска = треска” meaning “sliver”, Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1027. |

| ↟39 | Simoni, “Ruk. sborn. Publ. bibl., XVII,” p. 38. |

| ↟40 | Some artisans, afraid to top up the ink with liquids which were not yet sufficiently fermented, or which contained sugary substances that would dry poorly, specify:

Доливать комедью или вином горячим или медвяным квасом стоялым. А патоки и медвяного нового квасу отнюдь в чернило не класть, занеж становятся не черниле лоск злой и писанное лист с листом сливается бедно. Top up with resin or heated wine or with standing honey kvass. But by no means add molasses or new honey kvass, for an evil gloss will arise in the ink, and anything written will transfer from one page to another undesirously. Simoni, P., ed. “Ruk. Mosk. sinod. bibl., No. 871-521.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 110. The specified acids achieved using a sugary alcohol solution degrade once they are converted into carbon dioxide by acetic bacteria. |

| ↟41 | The clove protects ink containing resin and other organic substances from decay and the formation of mucilaginous compounds. Clove oil is still used in modern times for the same purpose. |

| ↟42 | jeb: I’m basing this translation of хотки (Med. Rus. khotki) on several related words (хоть, хоти, хотъный), cf. Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1389. |

| ↟43 | This was because cobblers used it when blackening tanned leather goods. |

| ↟44 | Here, the green crystals of iron sulfate, losing their crystallization water, turn into a white powder. The meaning behind this step is not completely clear. Undoubtedly it was adopted along with the use of vitriol from Western artisans, who also added powdery vitriol which had lost its crystallization water when preparing ink. |

| ↟45 | “Ikon. podl. Publ. bibl. im. Lenina, No. 1463.” Publichnyj vestnik izjaschnykh iskusstv. 1887 (4), p. 563. Povtorenija sbornika poloviny XVIII v., Istor. muzej, Moskva, No. 1288, p. 40. in Rukop. sborn. nach. XVIII v. arzamasskogo diakona Feodora, prepared for publication by P. Simoni. |

| ↟46 | jeb: ꙗчьныи meaning ячменный, “barley”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1676. |

| ↟47 | jeb: прѣти = пьрѣти meaning вести дело, “transact business”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, pp. 1705, 1774. |

| ↟48 | jeb: кукшин > кувшин, “jug”. |

| ↟49 | jeb: оныи meaning тот, будущий, “there, to-be”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, pp. 674-675. |

| ↟50 | The term “oak gall placement” (Rus. чернильное ставление, chernil’noe stavlenie) typically means the preparation of oak gall ink. This ink is brewed from the bark, cf. for example, Simoni, op. cit., p. 336, early 18th century: “Память как чернило ставити” (“On the preparation of ink”), as well as “Их указ чернило варить” (“Directions for brewing ink“). |

| ↟51 | Ikon. podl. Troitse-Serg. lavry, No. 408-1245. |

| ↟52 | That is, it bubbles from fermentation. |

| ↟53 | jeb: угнѣтати meaning теснить, задавливать, “to squeeze,” “to crush”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1134. |

| ↟54 | jeb: укладъ meaning сталь, “steel”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1178. |

| ↟55 | jeb: “…and the ink is caught in the last quarter of the moon, and it is finished in the waxing moon of the first quarter.” |

| ↟56 | Where exactly V.A. Schavinskij discovered the aforementioned quote is not mentioned in his notes. M.F. |

| ↟57 | jeb: пущати meaning напускать, разрешать, отгонять, “to let,” “to allow,” “to drive away”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. II, pp. 1743-1744. |

| ↟58 | The bark could be replaced with blueberries. A single “Recipe for Blueberry Ink” (“Указ о черниле черничном”) was preserved in a manuscript from the 16th-17th centuries.

Первее положити в котел две доли ягод черницы и третiю воды, лий штей кислых, и вываря то паки приготовь и третiе, потомуж приложа варити, что останется процедити в скудельник выжав ягоды. Положити в него железа ржавчивого, орешков и патоки по мере повязать платом впятеро и даты стоять до двою на десять дней. Потом же помешивать по вся дни до дваю на десять днiе, пытати потом пером. First place in a cauldron two parts blueberries and one part water or sour cabbage soup, and boil this, and then third, boil what remains after pressing the berries in a clay pot. Add some rusty iron or oak galls to this liquid, having first tied them up in a piece of cloth, and let it sit for two and ten days. Then stir it all day long for two and ten days, and then test it with a quill. An analogous recipe starting with the words “boil some tough krutik in water, so that the dyes color it” (“в воде варить краску крутик, что крашенины красят”) and so forth, is unclear, since krutik, or indigo, does not dissolve in wine[jeb: sic] and could not provide any benefit to ink. |

| ↟59 | V.A. Schavinskij’s manuscript does not provide any indication where he discovered this text. M.F. |

| ↟60 | jeb: ꙋпрѣти = ꙋпьрѣти meaning победить в споре, доказать вину, “to win an argument,” “to prove guilt”; Sreznevskij, op. cit., vol. III, p. 1251. |

| ↟61 | P. Simoni, ed. “Rukop. podl. ikon., Rukop. otdel. bibl. Akad. nauk, 45, 10, 1.” Pamjatniki drevnej pis’mennosti i iskusstva, vol. CLXI, 1906, p. 226. |

| ↟62 | jeb: Rus. золотник, a Russian measure of weight equal to about 4.26 grams. |

| ↟63 | Simoni, P. “Rukop. Gos. Istor. muzeja v Moskve, No. 2126.” Prepared for publication. There is no basis whatsoever to assume, as I.I. Sreznevsky thought, that the ink in the Galician Gospel contains iron. It is very likely that this is pure soot-based or “smoked” ink. |

| ↟64 | The development of techniques for determining the varying contents of ink could also be useful in yet one more regard. Being familiar with the chemical properties of their various component parts, we could expect to discover the methods for restoring texts of our oldest manuscripts, damaged by time, such as those which are found in our vaults in not small numbers. (In our day, similar work has been taken up in the laboratory of the Institute of Historical Technology of the State Academy of the History of Material Culture with great success. M.F.). |