My first year in grad school for Slavic Languages, one of my classes was on Old Church Slavonic (OCS) or Old Slavonic. OCS is a preserved form of very early Slavic, as close to proto-Slavic as exists in any written form. It developed in the Bulgarian region, however, and as such contains a heavy slant toward south-Slavic qualities, and developed separate from vernacular Russian and other modern Slavic languages. My fellow students and I arrived in class on the first day, where the professor told us there was no text book (the best work, Lunt’s Old Church Slavonic Grammar, was out of print, he told us. But, we might be able to find a copy in a used book store…). He then proceeded to have us start reading passages from texts out loud and trying to translate them, teaching us on the fly how to pronounce the weird vowel symbols or the grammar which was quite different from the Russian we knew (although, luckily, there were quite a few helpful similarities with Serbo-Croatian, which I was taking in the hour immediately before OCS). Almost all the reading passages were from the Gospels (as those are the main source of texts in OCS), and one day as I was walking to class, the Gideon Society was out and helpfully handed me an answer key to my reading passage for that day – a miniature copy of the New Testament.

In one of the early classes, the professor introduced us to photocopied texts written in an alphabet called Glagolitic, which scholars now think was the original alphabet created by St. Cyril when he and St. Methodius started to minister to the Bulgarian Slavs. Cyrillic was created later, named after St. Cyril, but both forms were used in early period. Whereas many of the Cyrillic letters are easy to decipher if you know some of the Greek alphabet (either from math or frat names, your choice…), the Glagolitic letters seemed kinda funky and looked like a “made up” code language to me. I learned later that this was because the letters were largely based on medieval Greek cursive forms, some of which look nothing like the Greek block characters. Back when Cyril was creating Glagolitic, the people from his hometown of Thessaloniki were bilingual in Greek and Slavic, and they were most likely quite familiar with the Greek cursive forms. Of course, that didn’t help me make any sense of a text like ⰵⰲⰰⰳⰳⰾⰻⰵ ⱁⱅⱏ ⰿⰰⱃⱏⰽⰰ!Even today, I can only recognize a few of the Glagolitic letters without a reference table, and as we did back in my class I still have to parse the letters one by one to determine that the phrase above says “evagg[e]lie otъ marъka” or “The Gospel of Mark.” Medieval Cyrillic looked more familiar, but had a number of odd characters I hadn’t seen before like Ѧ and Ѫ. It also used ь and ъ as pronounced vowels, rather than as silent orthographic markers like they are now in modern Russian. I’ve been interested ever since in trying to learn more about how these alphabets originated and how they interrelate.

The translation below is of Schepkin’s chapter on OCS and these two alphabets, their creation, and a comparison of the two and how some of the letter forms may have been created — from Greek block letters, from Greek cursive, or in some cases, by creatively combining forms to generate letters for Slavic sounds which didn’t translate well to either. He ends with a comparison of how the older vowels may have been pronounced, and uses this to investigate where Cyrillic may have borrowed from Glagolitic or vice versa as the two alphabets developed side by side. Schepkin included a great table comparing the Greek cursive, Glagolitic, and Cyrillic forms for a good number of letters.

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 2: Old Slavonic Language and the Slavonic Alphabets

A translation of Щепкин, В.Н. «Старославянский язык и славянския азбуки.» Учебник русской палеографии. Москва, 1918. с. 11-20. / Schepkin, V.N. “Staroslavjanskij jazyk i slavjanskija azbuki.” Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1918. pp. 11-20.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://ru.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Файл:Щепкин В.Н. Учебник русской палеографии. (1918) — цветной.pdf.]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 1: Goals and Methods

Chapter 2: Old Slavonic Language and the Slavonic Alphabets (this post)

Chapter 3: Dialects

Chapter 4: Materials and Writing Tools

Chapter 5: Ligatures (Vyaz’)

Chapter 6: Ornamentation

Chapter 7: Miniatures

Chapter 8: Watermarks

Chapter 9: Cyrillic Hands

Chapter 10: Russian Hands in Parchment Manuscripts

Chapter 11: South-Slavic Writing

Chapter 12: South-Slavic Influence on Russia

Chapter 13: Russian Poluustav Script

Chapter 14: Skoropis’

Chapter 15: Steganography (Tajnopis’)

Chapter 16: Numbers and Dates

Chapter 17: Verification of Dates

Chapter 18: Descriptions of Manuscripts

Appendix: Slavonic and Russian Chronology

Chapter 2: Old Slavonic Language and the Slavonic Alphabets

Old Slavonic is the name of that ancient Slavic language into which the Holy Scripture was translated in the 11th century by the “First Teachers” (Rus. Первоучители, Pervouchiteli), Sts. Cyril and Methodius.[1]jeb: This appellation is an abbreviation of Sts. Cyril and Methodius’ longer ecclesiastical title, Равноапостольные Первоучители Словенские / Ravnoapostol’nye Pervouchiteli Slovenskie / Equals to the Apostles, First Teachers of the Slavs. In modern day, the opinion prevails that the language of these apostles was one of the dialects of medieval Bulgarian, namely the medieval Thessalonian dialect. Old Slavonic has long been a dead language, and the question of its homeland has long been a subject of Slavic science. Even at the beginning of the 19th century, Vostokov pointed out the close relationship between Old Slavonic and Bulgarian based on phonetics: the proto-Slavonic tj = the Old Slavic and Bulgarian шт (“sht“), while P. J. Šafárik pointed out that, according to a primary historical source, the so-called “Pannonian” Lives of the First Teachers, the Slavic alphabet was invented by and that the translation of the Gospels was begun by St. Cyril while he was still in Constantinople, and therefore that the basis of Slavic writing was fixed by the language which had been known to Cyril earlier, that is, most likely, the Thessalonian dialect. Also quite important is the evidence from the Pannonian Lives that in Constantinople at the court cathedral, Cyril was told, “You are from Thessaloniki, and the Thessalonians speak pure Slavonic.” This quote testifies to the bilingualism of the Thessalonian Greeks which was well known to the Byzantine government. Other opinions on the homeland of the Old Slavic language were able to persist while there was insufficient information about Bulgarian dialects. It should, then, have been surprising that the indicated phonetic feature of the Primary Teachers’ language was actually closer to the Eastern Bulgarian dialect than to Macedonian, while Thessalonian refers to the latter. To this day, however, not far to the east of Thessaloniki and belonging to the Eastern Bulgarian dialect by origin, as well as in the modern Solun dialects, features of the transition from the Macedonian dialect to the Eastern dialect can still be found. These observations dispersed the apparent disagreement between the facts of language and history. It is clear that Cyril would have been able to pick up the Slavonic language in Thessaloniki or its surroundings in the 11th century.

The literary language of the First Teachers came to us in two alphabets – Glagolitic (Rus. глаголица, glagolitsa, from глагол, glagol, meaning “word” in medieval Russian) and Cyrillic (Rus. кириллица, kirillitsa). The word Glagolitic, like the word butvitsa (Rus. буквица, “initial letter”, derived from буква, bukva, “letter” or “character”), denotes an alphabet in general. The word glagolitsa is still used by Croats who maintain the Slavonic Glagolitic liturgy.[2]Among Croats, the word glagolica can be documented to the 16th century, and in Latin documents, the term glagola, glagolita “being used in Glagolitic ecclesiastical books” can be documented to the 14th century. The word bukvitsa in Western-Serbian regions (Bosnia) indicates a special alphabet which borrowed its letters from both Glagolitic and Cyrillic. The word Cyrillic obviously means “the alphabet invented by Cyril.” However, the antiquity of this word for this meaning has not been proven. To this day, it can be traced in this meaning only to the Kievan Theological School of the 16th century. Manuscripts from these apostles’ time have not survived, but the alphabets were known by at least the 11th century, and can even be traced to the 10th century: Glagolitic in some Kievan excerpts, and Cyrillic in an inscription by the Western Bulgarian Tsar Samuel (993).

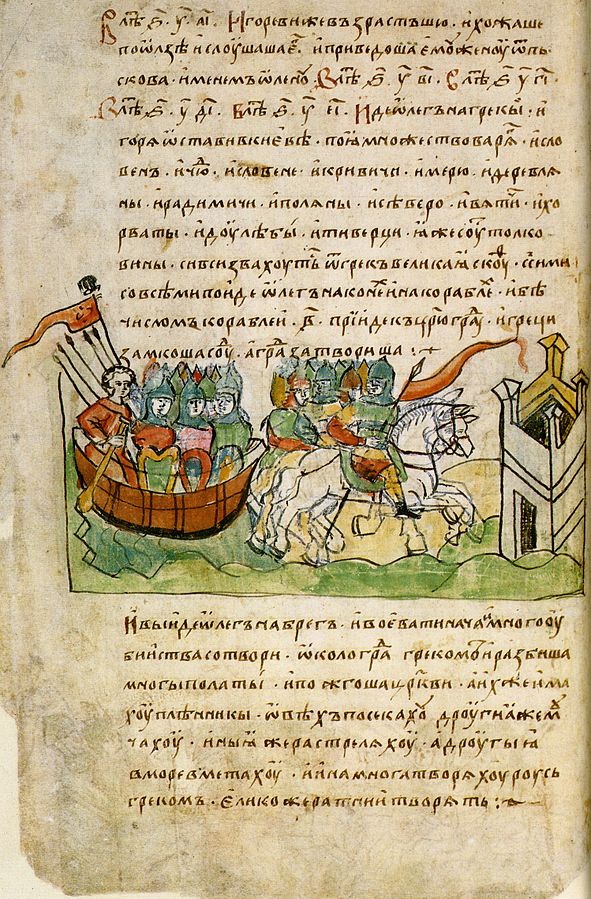

![jeb: An example of a work in Glagolitic, a page from the Codex Zographensis (late 10th-early 11th cent. copy of the Gospels). The title inside the box reads, in Glagolitic script:

ⰵⰲⰰⰳⰳ[ⰵ]ⰾⰻⰵ ⱁⱅⱏ ⰿⰰⱃⱏⰽⰰ

(Єваггєлїе отъ Маръка / The Gospel of Mark).

The notations in red at the top and right borders of the page are in Cyrillic. The writing in black on the left border is in Glagolitic.

Image in Public Domain.](https://b2058619.smushcdn.com/2058619/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ZographensisMark.jpg?lossy=0&strip=1&webp=1)

ⰵⰲⰰⰳⰳ[ⰵ]ⰾⰻⰵ ⱁⱅⱏ ⰿⰰⱃⱏⰽⰰ

(Єваггєлїе отъ Маръка / The Gospel of Mark).

The notations in red at the top and right borders of the page are in Cyrillic. The writing in black on the left border is in Glagolitic.

Image in Public Domain.

Not a single historical account mentions there being two Slavonic alphabets: the Life of St. Cyril the Apostle tells us only that he invented Slavic writing. The monk Khrabr, a writer from the so-called Golden Age of Bulgarian writing (Tsar Simeon’s school, 10th century), in his story about Slavonic writing, defends these writings and says, among other things, that they have been and are undergoing reform, but there is not a word about the existence of two different alphabets. Several of the factual statements cited by Khrabr, for example about the number of letters (38) in the Slavic alphabet, are obviously more applicable to Glagolitic than Cyrillic. The opinion that in Khrabr’s day there existed only one alphabet should be tossed aside; on the one hand, it is known that Simeon’s school used Cyrillic, and on the other, it is possible that the Glagolitic Kievan excerpts may be from Khrabr’s time.

Until the discovery of a series of medieval Glagolitic works, it was possible to speak only about the primacy or greater antiquity of Cyrillic; today, this possibility has been rejected. It is true that all of the extant material is to date so fragmentary that it allows only a hypothetical resolution to this question. However, by the mid-19th century, a gradual accumulation of material allowed the great Czech Slavist P.J. Šafárik to come up with the science-based hypothesis which to date has been accepted by the majority of Slavists. Šafárik came to the conclusion that Cyril invented Glagolitic, and that Cyrillic arose a half century later in Tsar Simeon’s school. One of Šafárik’s arguments must be rejected today: he referred to the fact that in the brief (Greek) Life of St. Clement (a student of the First Teachers, who died while Bishop of Macedonia during Simeon’s reign) directly says: “he also invented, for greater clarity, new letters.” But this brief Life of St. Clement has turned out to be unreliable, full of errors and fantasy, abbreviated from the longer (also Greek) Life of St. Clement . In the complete version, the quoted line is missing. However, the proposal remains completely likely that Cyrillic arose at the Byzantine court of Tsar Simeon as a direct imitation of a Greek charter hand. Let us look at Šafárik’s arguments which still preserve their evidentiary value.

I. In the regions where the First Teachers’ ministry began or spread early on, we do not find Cyrillic, bur rather Glagolitic.[3]Sts. Cyril and Methodius preached in the Great Moravian kingdom (now, the northwest corner of Hungary) and in Pannonia, that is, in the Principality of Balaton (now the extreme western part of Hungary including Lake Balaton). To the south of this latter territory, across the River Drava, begins the land of the Croats (now, Croatia and Slavonia, or the southwestern corner of Hungary).

1. The Kievan Glagolitic fragments – the only Old Slavonic manuscript which based on paleographic indicators dates to earlier than the 11th century – indicate it originated from the western-Slavic regions. This is a liturgical book for of Catholic composition (a missal), translated from Latin, and containing Latinisms such as мьша (m’sha, Latin missa, “mass”), прѣфациꙗ (prefatsija, Latin praefatio, “preface”), or Богъ (Bog’) used as a Vocative form instead of Боже (Bozhe, cf. Latin vocative Deus, “God”). The Old Slavonic in this manuscript contains very special west-Slavic features, the origin of which some scholars explain as due to the scribe who wrote the manuscript being a Moravian. Other scholars, and with good reason, see in the Kievan language fragments of a special Old Slavonic dialect, specifically of Slovenian,[4]The Slovenes were a Slavic people living to the south and north of the lower Danube. Those to the south of the Danube later came to be called Bulgarians. The Slovenes to the north of the Danube were assimilated by the Romanians and Hungarians. The word “Old Slavonic” (Rus. старославянский, staroslavjanskij) was used for the Thessalonian language of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, and earlier for other Old Bulgarian (that is, South-Slovenian) languages. specifically a transitional dialect which was located along the border of modern-day Hungary with the lands of the Czech-Moravians, and which contained phonetic traits which were related to Western Slavic languages. At the same time, some see in the Kievan fragments a Moravian dialect of Old Slavonic, while others see a living transitional language, of which Slavic philology is acquainted with quite a few. According to the former theory, the manuscript was created in that region where Cyril and Methodius preached, while the latter says that it arose near that territory less than a century after the death of St. Methodius (died, 885), that is, in the period of Latinization of the Slavonic liturgy in Moravia and Pannonia.

2. The Prague Glagolitic fragments represent a Czech dialect of the Old Slavonic text, clearly pointing to the nationality of its scribe. Šafárik attributed these fragments to the 9th-10th century and associated them with the tale in the Pannonian Lives about the baptism of the Czech Prince Borivaya by Methodius and with the testimonies in the legends about Prince Wenceslaus of Bohemia. More recent paleographers attribute the Prague fragments to the 12th-13th century, and as such, the question arises whether they should be seen as echoes of the First Teachers’ liturgy in Czechia, or if they represent a secondary adoption of Glagolitic among Croats. We observe that now Slavists have rejected that the First Teachers’ liturgy arose in Czechia in Methodius’s time, given that the oldest surviving fragments of the Scripture translated into Czech contain derivations from the Old Slavonic translation.

3. Among the Dalmatic Croats in the 12th-13th century and to this day, only Glagolitic can be traced. The oldest example of this, the Viennese Passages from the 12th century, are a Croatian dialect of Old Slavonic. They were discovered after Šafárik, but he was already able to point to the broad, early spread of Glagolitic writing among the Croats and to speak about their unbroken Glagolitic tradition going back into the depths of history. In addition, by the 10th century, at the local cathedral in Split, the Slavonic liturgy was condemned as an evil which was already ingrained into the Croatian regions. At that time, it could only have reached Dalmatia through Pannonia.

4. The surviving works in Old Slavonic (Old Bulgarian) dialect can be divided into two classes: Glagolitic works with phonetics which point to Macedonia, where the First Teachers’ student Clement preached, and Cyrillic works pointing to Eastern Bulgaria, where Tsar Simeon started his literary school. In literary works arising from the Simeon school, to date, no signs of Glagolitic have been found. This includes, for example, the luxurious Russian 11th century copies of 10th century Eastern Bulgarian manuscripts: the Ostromir Gospel, the Chudov Psalter, and the Svyatoslav Izbornik (actually created by Simeon) from 1073.

II. In 1047, the priest Upyr’ Likhoy penned a manuscript of the Prophets with Interpretations. This manuscript has not survived, but copies made from it preserved Upyr’ Likhov’s chronicle or “afterword”. It begins with the words: “слава тєбѣ господи царю нєбєсный, ꙗко сподоби мѧ написати книгы сиꙗ не кѹриловнцѣ” (slava tebe gospodi tsarju nebesnyj, jako spodobi mę napisati knigy snja ne kourilovntse / Glory to You, Lord, Heavenly King, for helping me to write this book in Cyrillic). Two of the earliest surviving copies date to the 15th century, and both contain letters and even whole words written in Glagolitic. The obvious conclusion is that in 11th century Novgorod, the Glagolitic alphabet was called Cyrillic. Glagolitic was known in 11th-12th century Novgorod, as demonstrated by two Glagolitic inscriptions from this time found on the walls of Novgorod’s St. Sophia Cathedral. Glagolitic letters adn words are also found in the earliest Russian manuscripts (11th-12th century), sometimes in the text, and sometimes in marginalia (Rus. приписки, pripiski).

Šafárik’s hypothesis was one of those tenacious theories which are able improve and draw strength over time. Cleared of mistakes by the efforts of Slavists in the second half of the 19th century, his hypothesis to this day adequately interprets all newly discovered facts and all newly arising questions. Al attempts to shatter his conclusions through other interpretations or combinations of facts have so far been unsuccessful. However, we should remember that, due to the limited and fragmentary nature of the material upon which Šafárik’s hypotheses were founded, they can principally be called only hypotheses. We are only sure that the surviving material does not allow any other, more believable hypothesis, but we cannot be sure that this material is overall sufficient to fully discover the truth. A similar restriction also remains in force related to even the most fruitful scientific hypotheses.

With regards to the source of both alphabets, the vast majority of scholars agree: Cyrillic is an exact duplicate of the Greek liturgical charter hand (Rus. устав, ustav) from the 9th-10th centuries, while Glagolitic was based on Greek cursive from around the same time. In 9th century Byzantium, both forms of writing were in use, but starting in the 10th century, the Byzantine charter hand (that is, with straight, separate and precise letters) ceased to be the typical hand, and continued to be used only for liturgical purposes, e.g., for luxurious, calligraphically-executed liturgical books: the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and Psalters. But it would not be careless to take from this fact that any kind of dates for the Slavonic alphabets. For example, it would be impossible to assert that Slavonic Cyrillic was created in the 9th century, rather than the 10th, for nothing could have prevented Simeon’s school from creating a liturgical hand in imitation of the Greek liturgical hand, or from using as Cyrillic that Greek charter hand which was is use during the years of Simeon’s youth, which he spent in Constantinople (prior to 893), and in even earlier manuscripts. Of course, we should remember that the currents of culture, especially in the border areas, do not change overnight, and the disappearance of the charter hand for business purposes in the 10th century does not mean that it disappeared everywhere in the early years of that century.

Glagolitic. The Glagolitic letters are clearly divided into two classes: 1) letters inherently belonging to the Greek language and alphabet, and 2) letters which were foreign to the Greek language and alphabet. The first class of letters was primarily adopted directly from Byzantine cursive and has little in common with the corresponding Cyrillic letters, which borrowed from Byzantine charter hand. The abundance of rounded forms and loops in Greek cursive prompted Glagolitic’s creator to stylize almost all letters using loops; by removing some of these loops, we can recognize the Greek cursive letters. See for example the Greek and Glagolitic letters for г, д, i, л, в, and ю (table 1, columns I and II, rows 2, 3, 4, 5, 11). Not all of the letters can be explained this way. Some letters have been explained differently by different scholars, but the line of thinking published by the English scholar Isaac Taylor (The Alphabet: An Account of the Origin and Development of Letters. London, 1883) is beyond doubt. Even the second class of letters, made up of signs which were foreign to the Greek language and alphabet, are somewhat easily explained as ligatures (conjunctions) of two Greek letters. For example, the Glagolitic letter Ⰱ (Rus. б, b – table 1, row 1) is a ligature of the Greek cursive letters μπ (“mp”), and all of the Slavonic affricatives contain in their Glagolitic forms, it seems, the Greek σ (“sigma”, the letter “s”) – for example, the Glagolitic letters Ⱌ (Rus. ц, ts – table 1, row 2), Ⰷ (Med. Rus. Ѕ, dz – table 1, row 3) and Ⱍ (Rus. ч, ch – table 1, row 4). The signs which are alien to the Greek language and alphabet are interesting in another sense: many of them in Glagolitic are closely related to their corresponding Cyrillic forms. This relationship can be seen in the letters Ⰱ (Rus. б, b), Ⱌ (Rus. ц, ts), Ⰷ (Med. Rus. Ѕ, dz), Ⱍ (Rus. ч, ch), Ⰶ (Rus. ж, zh), Ⱎ (Rus. ш, sh), Ⱋ (Rus. щ, sch), Ⱘ (Med. Rus. Ѫ, ǫ), Ⱔ (Med. Rus. Ѧ, ę), Ⱏ (Med. Rus. ъ, ŭ), Ⱐ (Med. Rus. ь, ĭ) (table 1, columns IV-V). The same cannot be said for those letters which were characteristic of Greek: Ⰳ (Rus. г, g), Ⰴ (Rus. д, d), Ⰾ (Rus. л, l), etc. (table 1, rows 2, 3, 5).

(jeb: translations: Column I: Greek cursive, Column II: Glagolitic, Column III: Cyrillic, Column IIIb: Greek cursive, Column IV: Glagolitic, Column V: Cyrillic.)

Row 1, a (а), б (б / b); Row 2, г (г, g), ц (ц / ts); Row 3, д (д, d), ѕ (дз, dz); Row 4, і (и, i), ч (ч, ch); Row 5, л (л, l), ж (ж, zh); Row 6, у (у, u), ш (ш, sh); Row 7, т (т, t), щ (щ, sch); Row 8, с (с, s), ѫ (ǫ); Row 9, х (х, kh), ѧ, ѩ (ę, ję); Row 10, н, (н, n), ѧ (ę); Row 11, ю (ю, ju), ѣ (e, ě); Row 12, о (о), ъ (ъ, ŭ); Row 13: є (e, e), ь (ь, ĭ)

In some cases, the similarities are immediately clear (hissing sounds, or sibilants), while in others, it becomes apparent if the Glagolitic letter is turned on one side (the yus letters: Ѧ, Ѫ).[5]jeb: These letters, called little yus and big yus, represent the nasalized vowel sounds ę and ǫ (respectively) which no longer exist in modern Russian, but were present in Medieval Russian. The Cyrillic characters, in addition to their more geometric style, are also somewhat simplified. The geometric style of some of these Glagolitic letters can be explained in that not all of Glagolitic was stylized with twists and loops; for example, the letters а and б are geometrical. Likewise, there is no need to accept that letters such as ш were borrowed into a later form of Glagolitic from Cyrillic. Such an assumption would only make sense if one assumed a priori that Cyrillic was invented by St. Cyril and that the oldest form of Glagolitic was a pre-Cyril vernacular alphabet of a quite imperfect character; even then, it would be difficult to argue that this supposed “older” form of Glagolitic was completely devoid of unique signs for especially Slavonic sounds. Let us return again to the analysis of these similar letters in Glagolitic and Cyrillic. Most important to us are those which help answer the question about letters were borrowed from Glagolitic into Cyrillic, or vice versa.

The letter ш (sh) is derived from a very similar Hebrew character, or from a Greek ligature for σσ (ss). The letter щ (sch) denotes the group шт (sht), and as such the Cyrillic щ better expresses the purpose of this sign than the Glagolitic Ⱋ. However, it is impossible to confirm whether the Glagolitic letter (table 1, column IV, row 7) was borrowed from the Cyrillic щ, for the theory remains quite possible that the Glagolitic щ (Ⱋ) contains a Greek T stylized with loops, for example, see another stylized Glagolitic T (Ⱅ – table 1, column II, row 7). The Glagolitic letters Ⱏ (ъ) and Ⱐ (ь) are similar that the oldest of their variants are explained from Glagolitic itself as variants of the letters Ⱁ (о) and Ⰵ (е). Later variants (table 1, column IV, rows 12-13) appear to have served as prototypes for the Cyrillic ъ and ь, which cannot be fully attributed to either the Greek or Cyrillic alphabets. The Glagolitic yus letters can be decomposed into O, E plus a symbol similar to a Cyrillic є, apparently expressing the nasal vowel tone, and thought to be related to the Glagolitic Ⱀ and the Greek cursive letter for н / n (table 1, columns I-II, row 10). As such, they represent nasalized o and e sounds. The Cyrillic letters Ѫ and Ѧ (as with ъ and ь) express nothing per their composition, but they look like geometrically re-stylized versions of the Glagolitic yus letters placed on their sides (Ⱘ > Ѫ, Ⱔ > Ѧ) (table 1, columns IV-V, rows 8-10). Finally, the Glagolitic jat‘ Ⱑ (ѣ / ě) (table 1, column IV, row 11) decomposes into a simplified, geometric version of Ⰺ + Ⰰ (і + а), and as such represents the ja sound. The Cyrillic jat’ ѣ decomposes into the letter ь (ĭ) and the Glagolitic Ⰰ (a) (table 1, column II, row 1). Finally[6]jeb: sic. – the original text says “finally” in both this and the previous example. the Glagolitic Ⱓ (ю / ju) (table 1, column II, row 11) contains a stylized Greek υ (upsilon / у / ŭ or oo – table 1, column II, 6) (another stylized form of υ can also be seen in the Glagolitic Ⰲ / в / v), while the Cyrillic ю is merely a re-stylized form of the Glagolitic letter (Ⱓ > ю). In all of these examples, the Glagolitic letters are likely direct sources for the Cyrillic letters, while the Cyrillic ѣ preserves in its upper section signs of a borrowing from a Glagolitic letter.

From this comparison of various Glagolitic letters with their Cyrillic forms, we can extract some interesting linguistic conclusions. The letter ю (= Greek υ, upsilon) apparently represents the letter ŭ, and not ju with a preceding jot, and also not iu with a preceding non-syllabic i. In Cyril’s time, the Greek υ had not yet turned everywhere into an i sound, and in Macedonia, just like today, there were Greek dialects which pronounced υ as ŭ. As for the Novgorodian letter ю, just like today, was pronounced as one type of ŭ. The Glagolitic jat’ Ⱑ indicates not only the vowel ѣ (ě), but also ꙗ (ja). This could be an inaccuracy in the recording of two separate sounds, or might indicate that in the First Teachers’ language both vowels matched the diphthong ja with an unsyllabic jot. In Cyrillic, ѣ and ꙗ are different, in that ѣ decomposes into ь + а, that is, most likely indicates the diphthong ea. The modern Eastern Bulgarian dialect in many cases to this date preserves the same pronunciation as this medieval ѣ. The Cyrillic ѩ (iotated[7]jeb: iotation is a term used in Slavic paleography and linguistics to indicate that a vowel is preceded by a palatalized “y” sound, a > ya (also written as “ja”, to clarify that the iotation is pronounced as part of the same syllable, not as a separate syllable). Most Russian vowels have unpalatalized/palatalized partners: a/ja, o/jo, e/je, u/ju, etc. small jus — ję) as a compound letter obviously corresponds to the Glagolitic compound letter Ⱗ, whereas the Cyrillic ѧ (ę) represents the Glagolitic Ⱔ. However, some Glagolitic works (among them, the earliest of the Kievan fragments) only contain the letter Ⱗ, which as we have seen decomposes into e+n and, as such, originally indicated only that nasalized ѧ / ę, and not the iotated ѩ / ję. On the other hand, the Glagolitic letter Ⱔ (as we saw from the comparison with the Glagolitic Ⱘ=n+o) indicates only n and as such originally could not have been used as a nasalized e. Glagolitic originally did not denote so-called iotation at all. The Glagolitic Ⰵ was originally used for both е (e) and ѥ (je); Ⱑ was used for both ѣ (ě) and ꙗ (ja). It appears that only later, the compound letter Ⱗ came to represent ѩ (ję), and that from the same Glagolitic letter, the simplified form Ⱔ came to be used for ѧ (ę). It is possible that this differentiation between Ⱔ and Ⱗ arose in Glagolitic not on its own, but under the influence of the emerging Cyrillic alphabet, in which iotation is indicated (for the unsyllabic j between vowels, or after softened consonants).

Glagolitic and Cyrillic are obviously based on similar, but nevertheless different dialects of Old Slavonic. One dialect most likely pronounced ѣ as ja, and the other as ea (where the j and e were both unsyllabic). That these were dialects of Bulgarian is clear from the presence in both alphabets of the special symbol Ⱋ / щ (sht), which can usually only be seen in alphabets for languages which contains the phonetic group sht. The group sht is extremely common in Old Slavonic, as it was acquired from five different proto-Slavic groups:

1) from tj: платити – плаштѫ (platiti – plashtǫ / “to pay” – “I pay”), proto-Slavic platjǫ;

2) from stj: простити – проштѫ (prostiti – proshtǫ / “to ask” – “I ask”), proto-Slavic prostjǫ;

3) from skj: искати – иштѫ (iskati – ishtǫ / “to seek” – “I seek”), proto-Slavic iskjǫ;

4) from sk’ (that is, sk before a soft vowel): дъска – дъштица = дъщица (dŭska – dŭshtitsa = dŭschitsa / “board” – “tablet”), proto-Slavic dъskika;

5) from kt’ (that is, kt before a soft vowel): рекѫ – решти (rekǫ – reshti / “I say” – “to say”), текѫ – тешти (tekǫ – teshti / “I am headed” – “to head”, “to flow”), proto-Slavic rekti, tekti.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | jeb: This appellation is an abbreviation of Sts. Cyril and Methodius’ longer ecclesiastical title, Равноапостольные Первоучители Словенские / Ravnoapostol’nye Pervouchiteli Slovenskie / Equals to the Apostles, First Teachers of the Slavs. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Among Croats, the word glagolica can be documented to the 16th century, and in Latin documents, the term glagola, glagolita “being used in Glagolitic ecclesiastical books” can be documented to the 14th century. |

| ↟3 | Sts. Cyril and Methodius preached in the Great Moravian kingdom (now, the northwest corner of Hungary) and in Pannonia, that is, in the Principality of Balaton (now the extreme western part of Hungary including Lake Balaton). To the south of this latter territory, across the River Drava, begins the land of the Croats (now, Croatia and Slavonia, or the southwestern corner of Hungary). |

| ↟4 | The Slovenes were a Slavic people living to the south and north of the lower Danube. Those to the south of the Danube later came to be called Bulgarians. The Slovenes to the north of the Danube were assimilated by the Romanians and Hungarians. The word “Old Slavonic” (Rus. старославянский, staroslavjanskij) was used for the Thessalonian language of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, and earlier for other Old Bulgarian (that is, South-Slovenian) languages. |

| ↟5 | jeb: These letters, called little yus and big yus, represent the nasalized vowel sounds ę and ǫ (respectively) which no longer exist in modern Russian, but were present in Medieval Russian. |

| ↟6 | jeb: sic. – the original text says “finally” in both this and the previous example. |

| ↟7 | jeb: iotation is a term used in Slavic paleography and linguistics to indicate that a vowel is preceded by a palatalized “y” sound, a > ya (also written as “ja”, to clarify that the iotation is pronounced as part of the same syllable, not as a separate syllable). Most Russian vowels have unpalatalized/palatalized partners: a/ja, o/jo, e/je, u/ju, etc. |