Chapter 9 of Schepkin’s Textbook of Russian Paleography is an overview of the three major “hands” in Cyrillic paleography – ustav (Uncial), poluustav (semi-Uncial), and skoropis’ (cursive). The comparison of these three hands and their goals is useful information. He also discusses several of the earliest known examples of Cyrillic, including two inscriptions on the so-called Stone of Tmutarakan (1068) and the Samuil Inscription (993). This was fun, because I was able to find pictures of both and work through the transliteration and translation into English. He doesn’t provide any examples of the three hands from manuscripts, however, so I’ve provided sample photos of ustav, poluustav, transitional or early skoropis’, and later skoropis’, which were also fun to track down on the internet. I feel a need to put together a post with a dated list of manuscripts and which/where they can be viewed digitized online.

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 9: Cyrillic Hands

A translation of Щепкин, В.Н. «Кирилловские почерки.» Учебник русской палеографии. Москва, 1918. с. 92-97. / Schepkin, V.N. “Kirillovskie pocherki.” Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1918. pp. 92-97.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://ru.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Файл:Щепкин В.Н. Учебник русской палеографии. (1918) — цветной.pdf.]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 1: Goals and Methods

Chapter 2: Old Slavonic Language and the Slavonic Alphabets

Chapter 3: Dialects

Chapter 4: Materials and Writing Tools

Chapter 5: Вязь (Vyaz’)

Chapter 6: Ornament

Chapter 7: Miniatures (this post)

Chapter 8: Watermarks

Chapter 9: Cyrillic Hands (this post)

Chapter 10: Russian Hands in Parchment Manuscripts

Chapter 11: South-Slavic Writing

Chapter 12: South-Slavic Influence on Russia

Chapter 13: Russian Poluustav Script

Chapter 14: Skoropis’

Chapter 15: Steganography (Tajnopis’)

Chapter 16: Numbers and Dates

Chapter 17: Verification of Dates

Chapter 18: Descriptions of Manuscripts

Appendix: Slavonic and Russian Chronology

Chapter 9: Cyrillic Hands

The Old Slavonic works from the First Teachers'[1]An appellation used for Sts. Cyril and Methodius, the first missionaries to the Slavic peoples. time have not survived to modern day, and as such, the question about which alphabet was used by the First Teachers cannot be directly solved. Indirect evidence forces us to believe that St. Cyril invented Glagolitsa, as has been described above (see Chapter 2). This chapter will review the history of several Cyrillic hands (Rus. почерк, pocherk, “handwriting style”).

Over the course of the 12th century among the Orthodox Slavs, Glagolitsa generally disappeared and Cyrillic was left as our only remaining alphabet. Within Cyrillic, we distinguish three types of hands, or three basic manners of writing which succeeded one another: ustav (Rus. устав, literally “charter”), poluustav (Rus. полуустав, lit. “semi-ustav“), and skoropis’ (Rus. скоропись, “cursive”). The earliest and therefore original hand was ustav. At a certain point in time, ustav was completely replaced in all forms of writing by poluustav, and from that moment was preserved only as an artistic hand and for a very specific use: in luxurious, calligraphically-executed liturgical works. Later, poluustav was replaced by skoropis’ in those forms of writing which were used for practical purposes, and later even in the category of literary works. In the case of liturgical and other purely religious works, poluustav held on as long as written literature itself existed.

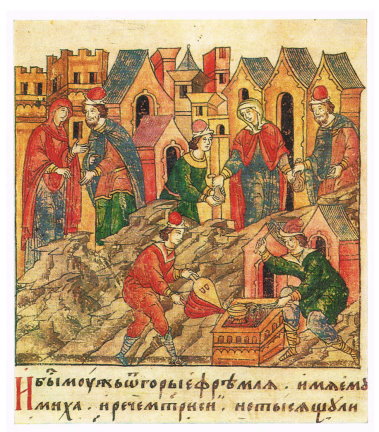

jeb: A page from the Svyatoslav Izbornik, 1073, written in ustav hand. Photo in public domain.

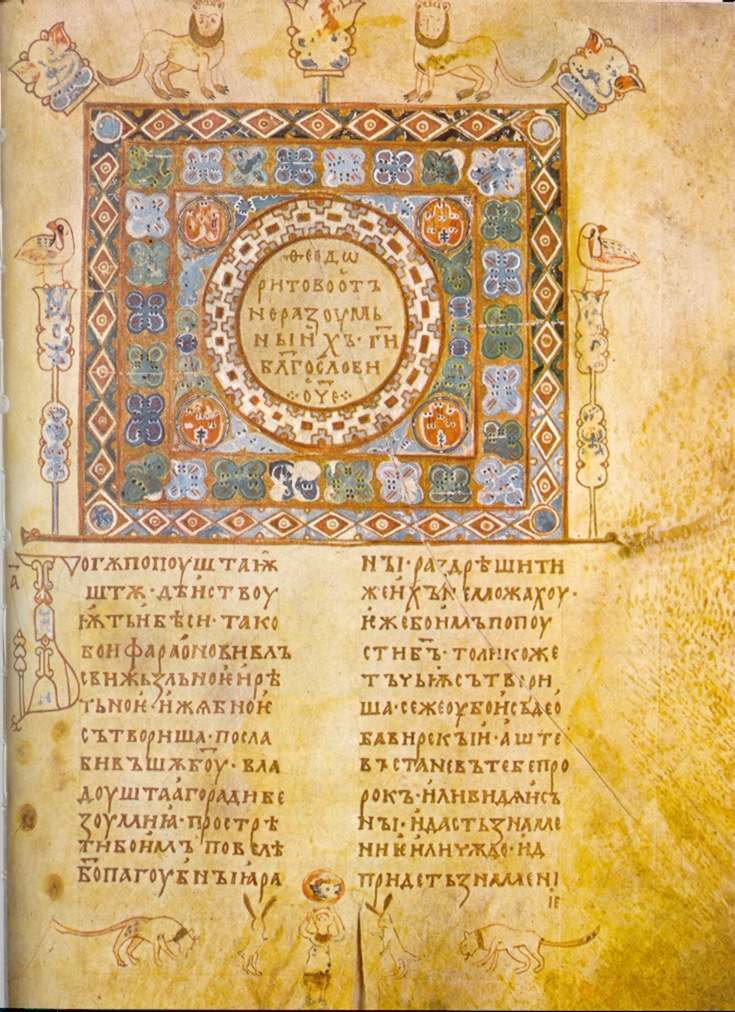

jeb: A page from the Buslaev Psalter, 1470-1490, written in poluustav hand. Photo in public domain.

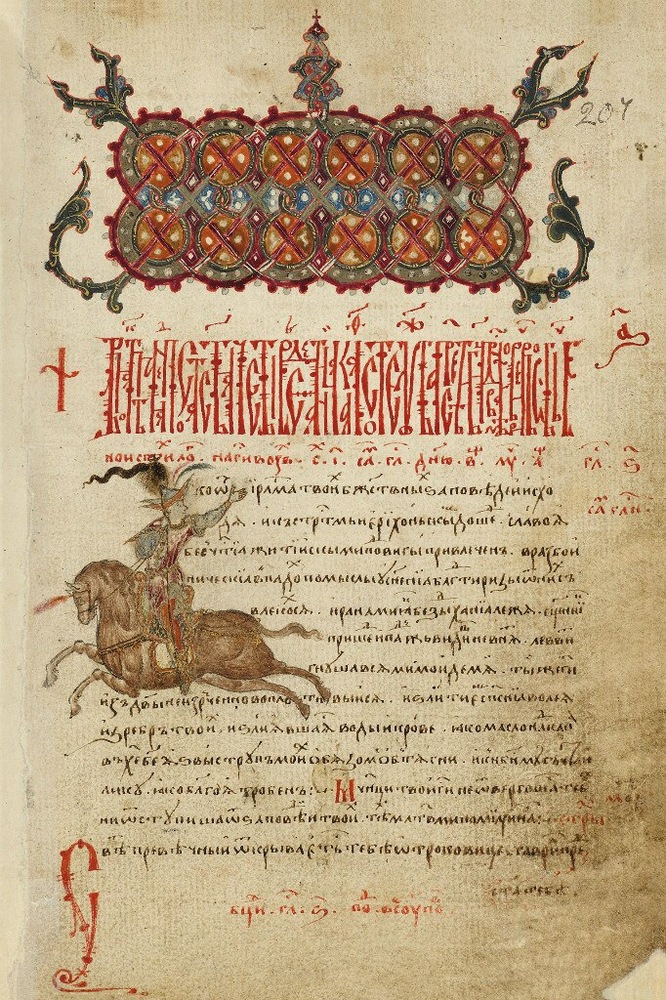

jeb: Another page from the Buslaev Psalter, 1470-1490, written in transitional skoropis’ hand. Photo in public domain.

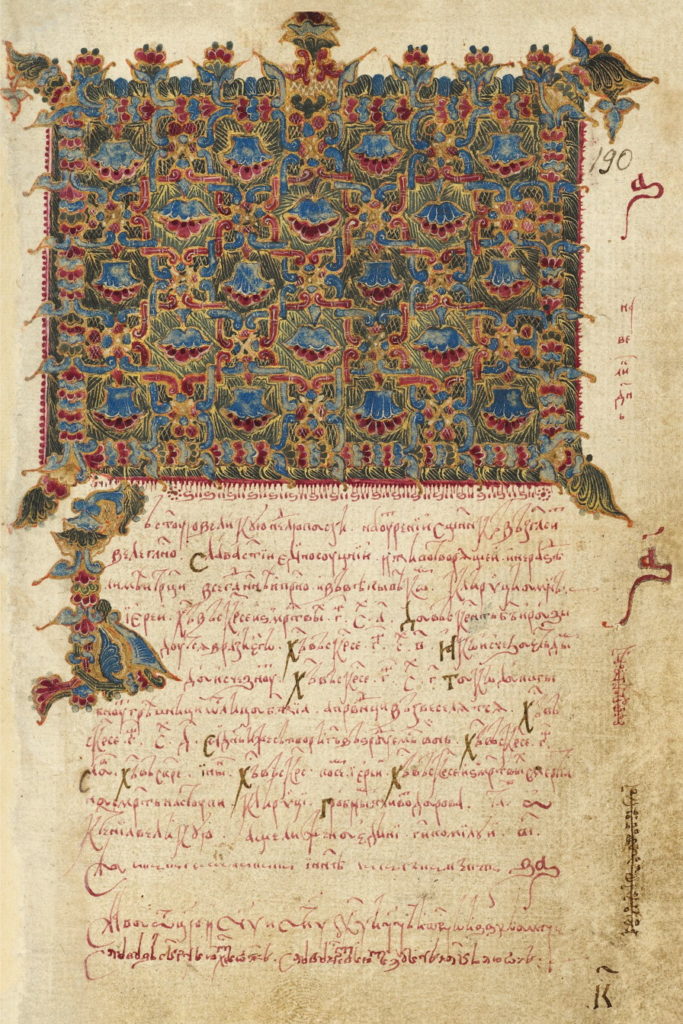

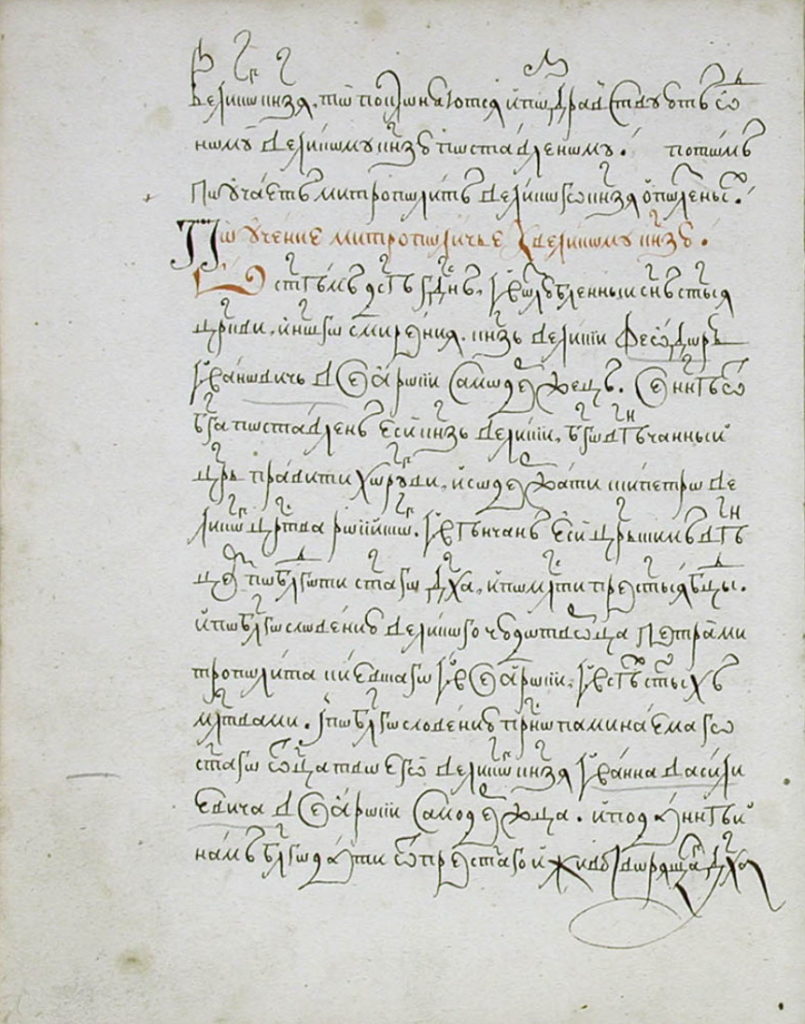

jeb: Page from the Coronation Rite of Tsar’ Feodor Ivanovich, 1584, written in skoropis’. Photo in public domain.

All attempts to accurately establish the distinctive characteristics of ustav, poluustav, and skoropis’ based on the appearance of these three types of writing suffer from uncertainty. definitions obtained in this manner by various scholars diverge significantly, and in fact often turn out to be insufficient. Meanwhile, practically speaking, that is, based on real examples, the distinction between these three types of writing is easily learned, and one rarely hesitates to choose the correct one. This is explained in that the mutual differences between ustav, poluustav, and skoropis’ are numerous, but are not all equally obligatory; that is, in each separate instance, those visible signs may be absent or weakly represented which might be considered essential by a given scholar. As a result, we consider it to be expedient to define ustav, poluustav, and skoropis’ not by their appearance, but by the purpose for which each of these types of writing were used. Similar to its source, Byzantine uncial (Rus. Византийский устав, Vizantijskij ustav), ustav is a slow and solemn form of writing. Its goal is beauty, accuracy, and ecclesiastical splendor. Ustav characterizes the age the writing had a principally liturgical character. From this flow all of its outer features: its distinct architectural character of line and its insignificant number of abbreviations. As with all writing, ustav has its variants, and over the course of its existence did not go without changes. For example, among the earliest of Russian manuscripts, the Ostromir Gospel has a large, beautiful ustav hand which is somewhat laterally compressed. The Svyatoslav Izbornik from 1073 has an ustav of medium size which is more simple, and has letters which are almost square (uncompressed laterally). Service menaea from the 1090s have an ustav which is small and simple. But, all of these works are characterized by a geometric, slowly-written character of letters and a small number of abbreviations. These traits of Russian ustav, along with all of its changes, were preserved even later on, for during this era of ustav, the writing of manuscripts was primarily a pious activity, and this point of view, which eliminated the haste of work, to a significant degree spread even to works which served practical purposes, for example charters (Rus. грамота, gramota).

Slavonic poluustav characterizes a time when writing outgrew its liturgical scope and found a wider literary evolution. Due to the increased demand for books, poluustav was more of a business hand for the scribes who worked on commission as well as for sale. Poluustav united the goals of ease of writing and accuracy, giving rise to its external form. Generally speaking, poluustav was smaller and simpler than ustav and had significantly more abbreviations. Much more frequently than ustav, poluustav was slanted, toward either the front or back of the letter, for strongly vertical hands require more time and attention to accuracy. Straight or vertical poluustav was typically devoid of calligraphic rigor: individual letters were only more or less straight than others. Likewise, poluustav letters do not hold to a strongly geometric principle. Straight strokes allow some curvature, and curves are not made up of perfect arcs. This all resulted in an easier or simplified writing process, striving primarily for convenience, with the requirement of beauty replacing that of clarity. This principle of ease was also served by the use of abbreviations, although their quantity could be quite varied. This convenience was associated, incidentally, with a certain acceleration of writing, but speed was not a direct goal of poluustav, for its other requirement was clarity. Poluustav in which this acceleration of the writing process is noticeably visible is called running poluustav (Rus. беглый полуустав, beglyj poluustav). If this desire to hasten the writing process was seen not only in the simplicity of the hand, but also in certain special adaptations from skoropis’, then we talk about this poluustav as being transitional to skoropis’. During the poluustav era, ustav was long preserved for use in sumptuous liturgical works. But, in the end, even in this artistic use, ustav was replaced by so-called calligraphic poluustav. This was larger and more meticulous than simple poluustav, but preserved many of the properties of poluustav which were developed for the purposes of convenience – namely, the use of sloped lines, the use of curves where lines had previously been straight, and the greater number of abbreviations.

Skoropis‘ is a general form of writing, having the exclusive goal of economy of time, or significantly accelerating the process of writing. Skoropis’ first appeared at the end of the period when ustav was prevalent, but became widely used only during the time of poluustav. It marks that time when writing was widely used only to meet the demands of high culture, but also as a tool for practical goals, at first for international and legal concerns, and then in public and private administration. In these last two areas, by virtue of the strengthening of government control and private economy, original brief records were increasingly replaced by a system of detailed documents. A significant acceleration of the process of writing was achieved in skoropis’ using particular methods which were used by neither ustav nor poluustav. These methods of writing are sharply reflected on the appearance of cursive letters and their connections. Even abbreviations took on a completely different character in skoropis’. See more below in the chapter on skoropis’ (chapter 14).

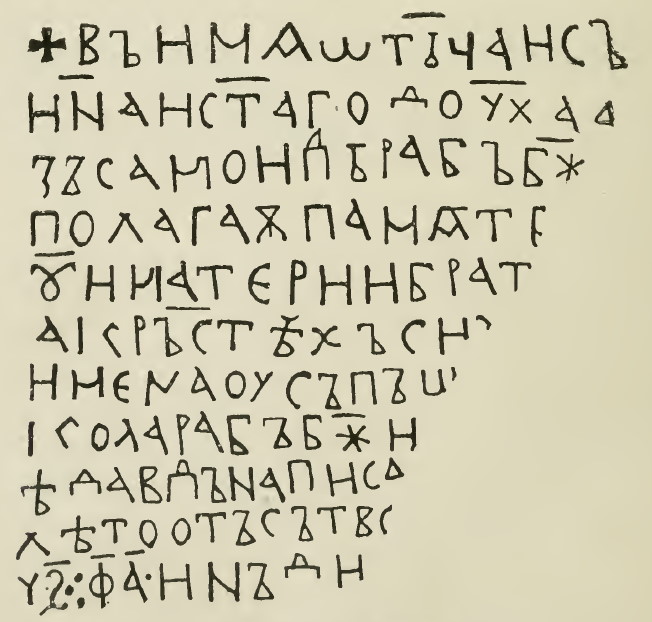

The origin of Cyrillic ustav has been described above (see chapter 2). Examples of the original use of Cyrillic have not survived to modern day.[2]Allowing that Glagolitsa was invented by St. Cyril the First Teacher, then we must indirectly accept that Cyrillic arose a half century later, in Eastern Bulgaria at the court of Tsar’ Simeon I in the first quarter of the 10th century. Having been educated in Byzantium and forever admiring of Constantinople culture, Simeon ascended to the Bulgarian throne in 893, and following a brief war concluded a 12 year peace treaty with Byzantium. After the expiration of this treaty, the second period of Simeon’s rule (913-927) was occupied by tense, uninterrupted wars with Byzantium. All of Simeon’s cultural activity fell during the first, 12-year period. It was then that he founded the first Slavonic literary school and Old Bulgarian literature. It was also then that, in direct imitation of Byzantine uncial, Cyrillic script may have been invented to replace Glagolitsa, which gave an impression of Eastern rather than Greek writing. From the surviving Cyrillic works from this time period, the earliest is an inscription bearing the name of Tsar’ Samuil, from 933. [3]This headstone with the names of the parents and brother of the Western Bulgarian Tsar’ Samuil was found in Macedonia, in a church in the village of German, near Lake Prespa. It appears that this inscription is also the earliest surviving work of Cyrillic, for among the undated items, none of their archaisms can compare to the Samuil Inscription (Rus. Надпись Самуила, Nadpis’ Samuila).

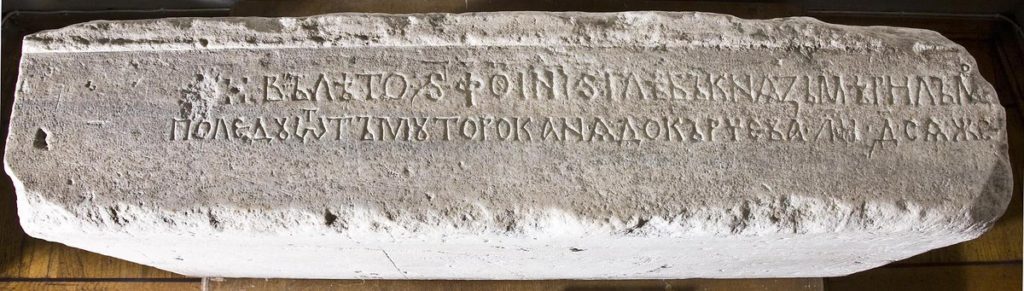

⁙въ лѣто ҂ѕ҃ф҃о҃ ін︮[д]і︯[кта] ѕ҃ глѣбъ кнѧзь мѣрнлъ мо[ре] / по ледꙋ ѿ тъмꙋтороканѧ до кърчева ҂і҃҂д҃ сѧже[нъ]

(vŭ lěto 6570 in[d]i[kta] 6 Glěbŭ knęzě měrilŭ mo[re] / po ledou ot tŭmoutorokanę do kŭrcheva 14000 sazhe[nŭ],

“In the year 6570 indicta 6 Prince Gleb measured the sea over the ice from Tmutarakan to Kerch 14,000 sazhen.”)

The earliest dated works of Cyrillic writing belong to the Russian dialect: the Ostomir Gospel of 1056-1057, the Svyatoslav Izborniks of 1073 and 1076, the Arkhangelsk Gospel of 1092, and three Novgorodian Menaia from the 1090s. As such, based directly on the handwriting of these manuscripts, we are only able to judge the Cyrillic hand from the second half of the 11th century. From this time period also comes the earliest example of Russian epigraphy, the so-called Stone of Tmutarakan from 1068. It contains an inscription saying that Prince Gleb measured the width of the Tmutarakan (Kerch) Straits from Taman to Kerch. However, we may also indirectly judge the writing of the 10th century and the first half of the 11th century. First of all, the Russian works of the 11th century, based on their language, point to their being copies of Old Bulgarian originals. The luxurious Ostromir Gospel preserves well the Simeon redaction not only of the text, but also of its language, that is, 10th century Eastern Bulgarian. In the Izbornik from 1073, the name of Prince Svyatoslav is famously written as a correction (that is, over a scraped spot), but one of the later copies of the same text preserves the name of Tsar’ Simeon in this spot. And although the 1073 Izbornik and other works convey their Old Bulgarian originals less carefully than the Ostromir Gospel and contain many Russisms, all of these works contain in their graphics (the drawing of the letters) and orthography (spelling) much that is traditional and which points back to their earlier originals. Secondly, examples of Old Bulgarian Cyrillic have survived, although they are both few in number and all undated, of which the most important are the Codex Suprasliensis (a Menaion for the month of March) and Savva’s Book (a canon evangeliary). Slavists date both these works to the 11th century based on comparisons with the aforementioned Russian works dated to the 11th century. The Codex Suprasliensis and Savva’s Book are somewhat earlier than these medieval Russian works. The 11th century Old Bulgarian manuscripts also preserve various features of their earlier originals in their graphics and their orthography. Thirdly, among the mostly insignificant epigraphic works, one genuine example from the late 10th century has survived, the aforementioned Samuil inscription. A comparison of these three sources allows us to made various assumptions about the early Cyrillic of the 10th century and thus to show archaisms and innovations in 11th century graphics. Fourth and finally, the ultimate source of Cyrillic, the Greek liturgical uncial hand of the 9th-10th century, verifies these assumptions.

⁜въ имѧ ѡт︮ь︯ца и съ

и︮н︯а и с[вѧ]таго дѹ︮х︯а а

зъ самоил рабъ б︮[о]ж︯(и)

полагѫ памѧт (ѡц)

ꙋ҃ и матери и брат(ѹ н)

a крь︮с︯тѣхъ сих(ъ се)

имена ѹсъпъш(ихъ ни)

кола рабъ б[о]ж҃и (риѱими)

ѣ давдъ написа(но се въ)

лѣто отъ сътво(рениѣ миро)

у ҂ѕ҃ф҃а҃ инъди(кта ѕ҃)

(vŭ imę otětsa i sŭ/ina i svętago doukha a/zŭ samoil rabŭ bozhi / polagǫ pamęt ots/ou i materi i bratou n/a krěstěkhŭ sikhŭ se / imena ousŭpŭshikhŭ ni/kola rabŭ bozhi ripsimi/ě davdŭ napisano se vŭ lěto otŭ sŭtvoreniě miro/u 6501 inŭdikta 6,

“In the Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, I, Samuil, servant of God, made a memory of [my] father, mother, and brother on these crosses. These are the names of the deceased: Nikola, servant of God, Ripsimia, [and] David. This was written in the year 6501 since the creation [of the world], indiction 6.”

Based on this data, we can assert that the original Cyrillic, which has not survived, had the following features:

- The letter a had a small triangular head, while the back stroke leaned to the left. The Samuil inscription, Savva’s Book, and sometimes the Codex Suprasliensis have this trait. Russian dated manuscripts from the 11th century do not have this feature, probably because they all belong to the second half of the 11th century. In South Slavic manuscripts, this type of a is also seen even later than the 11th century.

- The letter p had a small semi-circular head, at the top of a straight back stroke. This type of p is seen in the Samuil inscription and on silver coins made by Yaroslav the Wise (died, 1054). Russian dated manuscripts do not have this feature, nor do Savva’s Book or the Codex Suprasliensis. Later, this p reappears in South Slavic manuscripts, while in Russian undated manuscripts, a similar p is seen in the Life of St. Quadratus of Athens (Rus. Житие Кодрата, Zhitie Kodrata).

- The letters ц, щ stood upon their tails, and as such, similar to the early a, p, had a small upper section. The single ц in the Samuil Inscription is of this type. So too are the ц, щ in Savva’s Book. Russian dated manuscripts from the 11th century had already lost this feature. But in South Slavic manuscripts, this feature is still seen even later than the 11th century.

All of these traits can be identified as “small scale” symbols for the letters a, p, ц, щ. During the 11th century in Russia and the 12th century among the South Slavs, all of these letters increased in size to that of the other letters in the alphabet. Other graphic traits of the earliest Cyrillic are preserved in both Old Bulgarian and Old Russian works from the 11th century, and by and large are inherent to the manuscripts of the 12th century, in particular those of the South Slavs, which will be discussed in a later chapter.

The main works of Old Bulgarian were enumerated above (see chapter 3). They can be identified primarily by their dialect, that is, by the type of their language, and then, in association with the language, by their orthography, that is, by the way the letters of the alphabet are used to indicate sounds. In their language and spelling, these Old Bulgarian works show some dialectic differences, as explained in any scientific textbook of the Old Slavonic (Old Bulgarian) language.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | An appellation used for Sts. Cyril and Methodius, the first missionaries to the Slavic peoples. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Allowing that Glagolitsa was invented by St. Cyril the First Teacher, then we must indirectly accept that Cyrillic arose a half century later, in Eastern Bulgaria at the court of Tsar’ Simeon I in the first quarter of the 10th century. Having been educated in Byzantium and forever admiring of Constantinople culture, Simeon ascended to the Bulgarian throne in 893, and following a brief war concluded a 12 year peace treaty with Byzantium. After the expiration of this treaty, the second period of Simeon’s rule (913-927) was occupied by tense, uninterrupted wars with Byzantium. All of Simeon’s cultural activity fell during the first, 12-year period. It was then that he founded the first Slavonic literary school and Old Bulgarian literature. It was also then that, in direct imitation of Byzantine uncial, Cyrillic script may have been invented to replace Glagolitsa, which gave an impression of Eastern rather than Greek writing. |

| ↟3 | This headstone with the names of the parents and brother of the Western Bulgarian Tsar’ Samuil was found in Macedonia, in a church in the village of German, near Lake Prespa. |

| ↟4 | jeb: The inscription reads (with the text restored in parentheses where it was lost by the broken stone): ⁜въ имѧ ѡт︮ь︯ца и съ и︮н︯а и с[вѧ]таго дѹ︮х︯а а зъ самоил рабъ б︮[о]ж︯(и) полагѫ памѧт (ѡц) ꙋ҃ и матери и брат(ѹ н) a крь︮с︯тѣхъ сих(ъ се) имена ѹсъпъш(ихъ ни) кола рабъ б[о]ж҃и (риѱими) ѣ давдъ написа(но се въ) лѣто отъ сътво(рениѣ миро) у ҂ѕ҃ф҃а҃ инъди(кта ѕ҃) (vŭ imę otětsa i sŭ/ina i svętago doukha a/zŭ samoil rabŭ bozhi / polagǫ pamęt ots/ou i materi i bratou n/a krěstěkhŭ sikhŭ se / imena ousŭpŭshikhŭ ni/kola rabŭ bozhi ripsimi/ě davdŭ napisano se vŭ lěto otŭ sŭtvoreniě miro/u 6501 inŭdikta 6, “In the Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, I, Samuil, servant of God, made a memory of [my] father, mother, and brother on these crosses. These are the names of the deceased: Nikola, servant of God, Ripsimia, [and] David. This was written in the year 6501 since the creation [of the world], indiction 6.” |