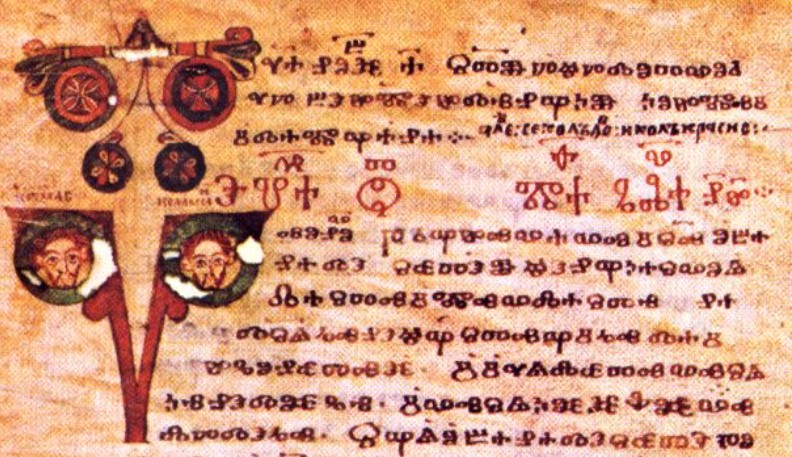

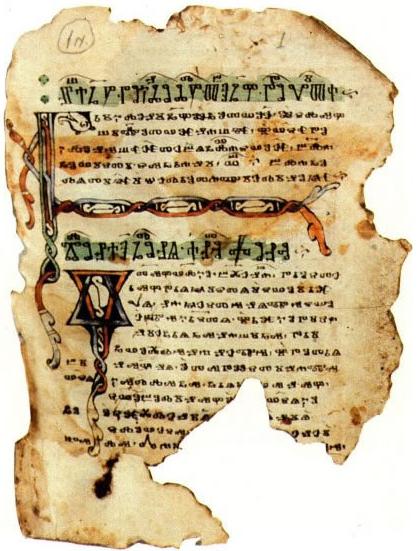

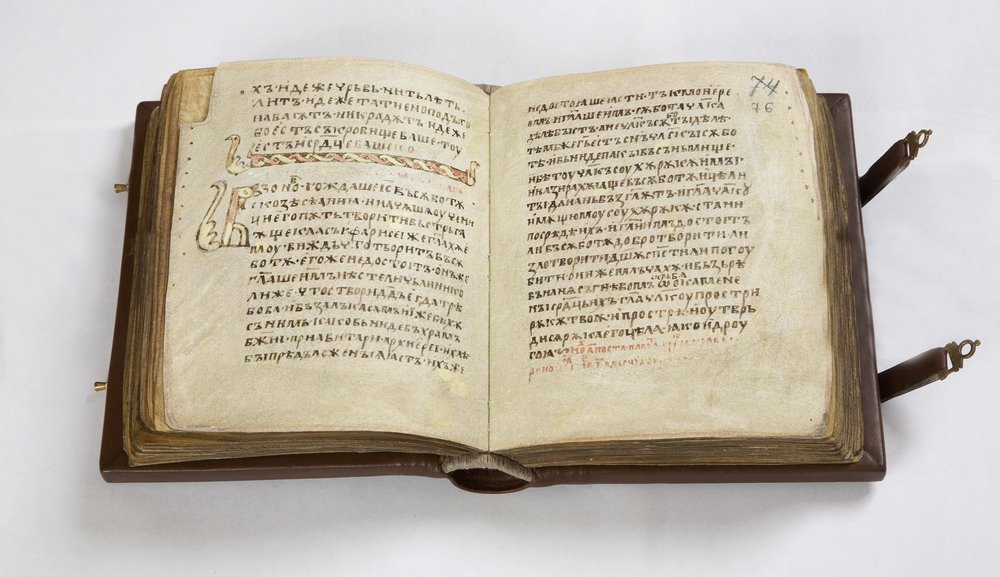

Another chapter of Schepkin’s Textbook of Russian Paleography completed. This chapter talks about the dialects of Old Church Slavonic (OCS) that were created by Serbian, Bulgarian, and Russian scribes as they introduced elements of their own language into OCS, mirroring the evolution that occurred as Proto-Slavic developed along the South Slavic and East Slavic tracks. Slavic languages underwent their own “great vowel shifts” just like English did, and instances of these mutations of vowels generating typos in the OCS. An interesting example are what the author calls “anti-Russisms,” where scribes knew how some words had mutated from OCS > Russian, incorrectly assumed other words followed the same pattern, and introduced typoes as a result. Based on these various kinds of typos, it’s possible to guess where a manuscript originated, where subsequent copies of it were made, and the nationality of the scribes involved. All of the examples are shown in Cyrillic, but originate from both Cyrillic and Glagolitic texts. This chapter is a bit more dense than the previous one, given the numerous grammatical and spelling examples. To help break it up, I provided a few pretty pictures of OCS manuscripts.

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 3: Dialects

A translation of Щепкин, В.Н. «Изводы.» Учебник русской палеографии. Москва, 1918. с. 20-25. / Schepkin, V.N. “Izvody.” Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1918. pp. 20-25.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://ru.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Файл:Щепкин В.Н. Учебник русской палеографии. (1918) — цветной.pdf.]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 1: Goals and Methods

Chapter 2: Old Slavonic Language and the Slavonic Alphabets

Chapter 3: Dialects (this post)

Chapter 4: Materials and Writing Tools

Chapter 5: Ligatures (Vyaz’)

Chapter 6: Ornamentation

Chapter 7: Miniatures

Chapter 8: Watermarks

Chapter 9: Cyrillic Hands

Chapter 10: Russian Hands in Parchment Manuscripts

Chapter 11: South-Slavic Writing

Chapter 12: South-Slavic Influence on Russia

Chapter 13: Russian Poluustav Script

Chapter 14: Skoropis’

Chapter 15: Steganography (Tajnopis’)

Chapter 16: Numbers and Dates

Chapter 17: Verification of Dates

Chapter 18: Descriptions of Manuscripts

Appendix: Slavonic and Russian Chronology

Chapter 3: Dialects

Local variants of the Old Slavonic[1]jeb: aka Old Church Slavonic, or OCS. literary language are called dialects (Rus. извод, izvod). The word dialect is a translation of the Greek word αρχητυπον (archetypon), meaning “the main form”. The Old Slavonic language of Sts. Cyril and Methodius (naturally, significantly changed) survives to this day in ecclesiastical use among the Russians, Bulgarians, Serbs, and partly among the Croats; in addition, among those first three nations, it was used for many centuries as a literary language. Due to its proximity to the Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian and Croatian languages, local features have always penetrated into works in Old Slavonic during the writing process, and as such, there arose dialects or local variants of the literary language. This situation was significantly different from medieval Latin writing, where for most peoples, Latin was completely unknown, and as a result, the peculiarities of the local language only occasionally was reflected on Latin texts. Along with the indicated “main forms” of literary Old Slavonic (or later, Church Slavonic), there are also a few other, less common dialects; for example, we spoke above about a Czech copy of an Old Slavonic original text (the “Prague fragments”); this work represents a Czech dialect. Another example of the Czech dialect is the Glagolitic part of the Rheims Gospel, written by a Czech in 1395.[2]In addition to the Glagolitic section, the Rheims Gospel also includes a Cyrillic section in an 11th century Russian dialect. This work, brought by chance during the Hussite Age to Rheims, has survived to this day in Rheims Cathedral, where during the coronation of the King of France, they would take their oath over the text of the Rheims Gospel. We mentioned earlier that some see a Moravian dialect in the Kievan Fragments. They also speak of a Romanian dialect in ecclesiastical texts, but the latter was actually a local variant of the Bulgarian dialect, for in the Middle Ages, Romania had a significant Slovenian (Bulgarian) population, and until the 17th century preserved a Middle Bulgarian dialect of Old Slavonic in its church.

Along with these dialects, we should note that the Old Slavonic language itself was, in principle, a dialect of the First Teachers'[3]jeb: Sts. Cyril and Methodius, Equals to the Apostles, First Teachers of the Slavs. pure language. In fact, no manuscript from the time of the First Teachers (mid-9th century) has survived to modern day; the oldest works of surviving Slavonic writing date to the late 10 century or 11th century. In science, it is customary to call “Old Slavonic” any of those works which do not contain any Russian, Serbian or later Bulgarian traits; in other words, for the most part, these are early copies made in various regions of the Bulgarian tribe, or works in 11th century Old Bulgarian which reflect in their language traits of various Old Bulgarian languages. In light of the age of these copies, and in particular in light of the special relationship of the First Teachers’ Old Bulgarian language to the remaining Old Bulgarian dialects, these 11th century works really give us the most accurate understanding of the Old Slavonic language. Vostokov and his followers, who from the very beginning insisted on the Bulgarian origin of Old Slavonic, introduced for later Bulgarian works (12th-15th century) the term “Middle Bulgarian,” which we shall use as well.

The peculiarities of Russian, Serbian, and Bulgarian which were introduced by scribes of these nationalities into Old Slavonic texts are commonly called Russisms, Serbisms, and Bulgarianisms. But in paleography, we also need to speak of anti-Russisms, anti-Serbisms, and anti-Bulgarianisms, understanding these terms to mean those incorrect spellings introduced into Russian, Serbian, etc. texts out of a desire to avoid Russisms, Serbisms, and Bulgarianisms. For example, spelling the word “swamp” as болото (Rus., boloto, “swamp”) would be a Russism, but the phrase въ злѣнѣ блатѣ (vŭ zlěně blatě, “in the green swamp”) actually contains an anti-Russism: the incorrect *злѣнъ[4]jeb: The asterisk before this word indicates it is a grammatically or orthographically incorrect form shown intentionally (as opposed to a typo). (zlěnŭ, “green”). The Russian word берег (bereg, “shore”) corresponds to the Old Slavonic брѣгъ (brěgŭ),[5]jeb: These examples of (OCS) брѣгъ >> (Rus.) берег and (OCS) блатъ >> (Rus.) болото are examples of polnoglasie or “full vowelization,” a tendency for consonant clusters to have inserted vowels, or for short vowels to become longer vowels in the transition from OCS/Slavic roots to the Russian form. but the Russian word зелен (zelen, “green”) corresponds to the Old Slavonic, Serbian and Bulgarian word зеленъ (zelenŭ), not *злѣнъ (zlěnŭ). Spelling the word as зленѣ (zleně) would also still contain a Russism – the Russian е instead of the Old Russian ѣ in the supposed form *злѣнъ (zlěnŭ).[6]jeb: Confused? He’s saying the correct form in OCS would be въ зеленѣ блатѣ. The misspelled *злѣнѣ would show the writer thought зеленъ was too “Russian”, so he tried to write it as *злѣнъ thinking it sounded “more like OCS,” assuming it would follow the same pattern as (Rus.) берег/(OCS) брѣгъ. The author calls this an “anti-Russism,” I call it “trying too hard.” Fun with grammar and orthography!

The Serbian, Bulgarian and Russian dialects each have their own linguistic peculiarities which generate violations of the Old Slavonic orthography, see more details below in the examples of dialects (see Appendix I). Some of these peculiarities are encountered quite infrequently, while others are seen not just in one dialect, but in two or three different dialects, which can be important for paleography, in order to quickly and accurately distinguish each dialect from all others. In addition, paleography provides an accurate means for those unfamiliar with Slavic languages to determine dialects: e.g. for historians, archeologists, archivists, numismatists, antiquarians, etc. From this point of view, the most valuable tool is the use of the letter ѧ, which in Old Slavonic indicates a nasalized e, taken from the proto-Slavonic nasal ę. Russian has, from the proto-Slavic nasalized ę, the letter а with a preceding softness which in known situations has disappeared, or which was not indicated in written form, due to which in Russian writing there is a mixing of letters: instead of the Old Slavonic ѧ (ę) we see the letters а (a) and ꙗ (ja), and likewise, we see the letter ѧ used instead of the ꙗ (and sometimes а); for example:

- рекоша instead of рекошѧ (rekosha/rekoshę, “I said”)

- пꙋстиша instead of пꙋстишѧ (poustisha / poustishę, “I sent”)[7]jeb: ꙋ is a letter called “Uk”, borrowed from Greek, and serving as a digraph of “ου” (omicron-upsilon). It was used in early Cyrillic to represent the sound u/oo, but was later replaced with a different form, ѹ (also called “Uk”), and even later as just у.

- часто instead of чѧсто (chasto/chęsto, “often”)

- ꙗзыкъ instead of ѩзыкъ (jazykŭ/językŭ, “language”)

- vice versa, ѩко or ѧко instead of ꙗко (jęko/ęko/jeko, “for/since”)

The examples of this inverse replacement is based on the face that the letters ѩ/ѧ and ꙗ/а are found in Old Slavonic texts in strictly defined situations, but for the Russian scribe they were equivalent and could not be told apart; later, these letter pairs received a specific orthographic meaning, which we’ll speak more of later. In Serbian, the proto-Slavic nasalized ę became a pure (un-nasalized) e, as a result of which in Serbian dialects we see е/ѥ (e/je) written instead of ѧ/ѩ (ę/ję):

- име instead of имѧ (ime/imę, “name”)

- рекоше instead of рекошѧ (rekoshe/rekoshę, “I said”)

- често instead of чѧсто (chesto/chęsto, “often”)

- ѥзыкь instead of ѩзыкъ (jezykě/językŭ, “language”)

The opposite is not seen, because in Serbian writing the letters ѧ/ѩ as an unnecessary pair were completely eliminated very early on. Only in a few of the earliest Serbian manuscripts do we sometimes encounter the yus signs.[8]jeb: this name refers to the names of 4 letters: ѧ (non-iotated little yus), ѩ (iotated little yus), ѫ (non-iotated big yus), ѭ (iotated big yus).

In modern Bulgarian, the proto-Slavic nasalized ę changed, with a few dialectical exceptions, into the non-nasalized e, but this evolution completed only at the end of the Middle Bulgarian period. Earlier on, the nasalized ę did not correspond to the non-nasalized e, and the two were usually not mixed in writing. The nasalized ę after the sibilant letters ж (zh), ш (sh), щ (sch) (=шт/sht) and жд (zhd) (and in some dialects also after the letters ч (ch), ц (ts), ѕ (dz), after a з (z) originating from a ѕ (dz), and after j’a) in Middle Bulgarian was similar to the letter which came from the proto-Slavic nasalized ǫ; as a result, in this position, the letter ѧ (ę) was consistently represented in written form as ѫ (ǫ):

- рекошѫ instead of рекошѧ (rekoshǫ/rekoshę, “I said”)

- dial. чѫсто instead of чѧсто (chǫsto/chęsto, “often”)

- ѫзыкъ instead of ѩзыкъ (ǫzykŭ/językŭ, “language” – in Old Bulgarian writing, the letter ѭ (jǫ) was almost never used)

On the other hand, the proto-Slavic nasalized ǫ in Middle Bulgarian after strongly-soft consonants (from the proto-Slavic groups nj, lj, rj, and labials+j) was similar to the letter which came from the proto-Slavic nasalized e. In these locations, ѧ (ę) was written instead of ѭ (jǫ):

- хвалѧ instead of хвалѭ (khvalę/khvalǫ, “I praised” – in Old Bulgarian writing, ѩ (ję) is almost never used)

- acc. sing. волѧ instead of волѭ (volę/voljǫ, “will”)

In some dialects of Middle Bulgarian, the letter ч (ch) was also treated as soft, and as a result there also existed the dialectical spelling плачѧ instead of плачѫ (plachę/plachǫ, “I cry”). As such, in very specific circumstances in Middle Bulgarian writing, we find the letter ѫ instead of ѧ, and ѧ instead of ѫ, a phenomenon which is commonly called (graphically) “jus shifts”.

It is clear that all three languages diverge in their use of the Old Slavonic letter ѧ (ę). As a result, the dialects can be identified based on this method. It is worth remembering, however, that:

- At the end of a word, the proto-Slavic nasalised ę in known cases resulted in the Russian letter ѣ (ě), from whence later we see the medieval Russian еѣ (eě) instead of the Old Slavonic ѥѩ (gen. sing. fem.), and later the Russian ее (jeje), and today the non-phonetic ее or её (jejo – “her”) as the genitive and accusative form. See also the Little Russian jeji, with an i instead of ѣ (ě).

- In the Bulgarian dialect, starting from the 15th century, we already encounter examples of writing е (e) instead of ѧ (ę), and earlier, there are rare cases of writing ѣ (ě) instead of ѧ (ę).

With these caveats, when getting accustomed to Old Slavonic orthography, the use of the letter ѧ can accurately determine the dialect. Instances of the use of the Old Slavonic ѧ (and in dialects, their replacements) are extremely frequent and can be found on almost any page of a manuscript. Persons unfamiliar with Slavic languages should have in mind a certain selection of Old Slavonic words which include the letter ѧ, as they are the most useful and most frequently encountered words: the pronouns мѧ, тѧ, сѧ (mę, tę, sę, “me, you, these”), the 3rd person plural aorist verb conjugations such as бышѧ, рекошѧ (byshę, rekoshę, “I was, I said”), etc. In any cases of doubt, referencing an Old Slavonic dictionary and/or grammar may be necessary.

As for the so-called Old Slavonic dialect, that is, those few of the most ancient manuscripts whose language does not include Russian, Serbian or Middle Bulgarian characteristics, the definition of this dialect cannot be quickly produced on the basis of an analysis of a few lines from a manuscript. The Old Slavonic dialect is characterized by the absence of certain features, and only by having completely read a given manuscript can we be assured that it definitely does not contain any Russian, Serbian, or Middle Bulgarian features. On the other hand, the Old Slavonic dialect contains several affirmative characteristics of the Old Bulgarian dialects from the 10th-11th centuries, primarily in their use of the letters ь (ě) and ъ (ŭ).[9]The Old Slavonic dialect is represented (aside from insignificant fragments) by in total eight manuscripts. Six of these are in Glagolitic: the Codex Zographensis (Rus. Зографское Евангелие, Zografskoe Evangelie, “Zograf Gospel”), the Codex Marianus (Rus. Мариинское Евангелие, Mariinskoe Evangelie, “Marianus Gospel”), the Codex Assemanius (Rus. Ассеманиево Евангелие, Assemanievo Evangelie, “Assemani Gospels”), the Psalterium Sinaiticum (Rus. Синайская Псалтырь, Sinajskaja Psaltyr’, “Sinai Psalter”), the Euchologium Sinaiticum (Rus. Синайский требник, Sinajskij trebnik, “Sinai Missal”), and the Glagolita Clozianus (Rus. Сборник графа Клоца, Sbornik grafa Klotsa, “the Count Cloz Collection”). Two are in Cyrillic: Sava’s Book (Rus. Саввина книга, Savvina kniga) (also known as the “Gospel-anrakos) , and the Codex Suprasliensis (Rus. Супрасльская рукопись, Suprasl’skaja rukopis’, “Suprasl Manuscript”) (a Menaion reader for the month of March). Some of the Glagolitic Kievan fragments are also of interest.

In addition to the simple dialects mentioned above, there also exist compound dialects, among which the most common is the Serbo-Bulgarian dialect, consisting of manuscripts copied by Serbs from Middle Bulgarian originals. It is also possible to make out a Russo-Bulgarian dialect, consisting of manuscripts copied by Russians from Bulgarian originals, primarily of Romanian wording. If a manuscript simultaneously contains both Serbian and Bulgarian characteristics, for example if it contains both the forms жетва instead of жѧтва (zhetva/zhętva, “sacrifice”) and рекошѫ instead of рекошѧ (rekoshǫ/rekoshę, “I said”), then we are able to determine in which order the two layers (Serbian and Bulgarian) of the Old Slavonic text were written. It is necessary to find in such a text those spellings in which one layer was directly applied over another; for example, the spelling рекошѹ (rekoshu, “I said”) shows us that the Old Slavonic рекошѧ (rekoshę) was first changed by a Bulgarian to рекошѫ (rekoshǫ), which then was changed by a Serb to рекошѹ (rekoshou = rekoshu). Such situations are rare misunderstandings: usually the Serbian scribes recognized in the Bulgarian рекошѫ their own рекоше (rekoshǫ/rekoshe) and wrote down the latter. But until we have found such spellings as рекошѹ, we can only guess based on probability in which order the Bulgarian and Serbian layers were laid down. Based on historical grounds, the most common situation would be a Serbian copy of a Middle Bulgarian original, rather than the opposite, as the Serbs joined the Slavic culture later than the Bulgarians, and in the period of their state’s might (13th-14th centuries) occupied the Bulgarian lands in Macedonia, where the influence of the Serbian church persisted even after the fall of the Serbian state (see the Appendix on Chronology). This question of the order of layers can also be answered using anti-Russisms, anti-Serbisms and anti-Bulgarianisms which, as we have seen, represent inept imitations of some other dialect by Russian, Serbian, or Bulgarian scribes. However, such imitations may also date back to the original manuscript and not be an accident by the scribe of a given copy. For example, alongside Serbisms and considerations of a purely literary nature, an anti-Serbism of молчаніе (molchanie, “silence”) instead of мꙋчаніе (mouchanie, “torment”) to mean “exposed to torture” found in one Russian copy convinced the academician Shakhmatov that the author of the Russian chronograph and therefore the creator of the original for these Russian copies was Pachomius the Serb (Pachomius Logothetes). The Russian words солнце (solntse, “Sun”) and домъ (domŭ, “house”) in place of the Serbian сунце (suntse, “Sun”) and дум (dum, “house”) were the source of the aforementioned misspellings (on these dialects, see also Appendix I).

Footnotes

| ↟1 | jeb: aka Old Church Slavonic, or OCS. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | In addition to the Glagolitic section, the Rheims Gospel also includes a Cyrillic section in an 11th century Russian dialect. This work, brought by chance during the Hussite Age to Rheims, has survived to this day in Rheims Cathedral, where during the coronation of the King of France, they would take their oath over the text of the Rheims Gospel. |

| ↟3 | jeb: Sts. Cyril and Methodius, Equals to the Apostles, First Teachers of the Slavs. |

| ↟4 | jeb: The asterisk before this word indicates it is a grammatically or orthographically incorrect form shown intentionally (as opposed to a typo). |

| ↟5 | jeb: These examples of (OCS) брѣгъ >> (Rus.) берег and (OCS) блатъ >> (Rus.) болото are examples of polnoglasie or “full vowelization,” a tendency for consonant clusters to have inserted vowels, or for short vowels to become longer vowels in the transition from OCS/Slavic roots to the Russian form. |

| ↟6 | jeb: Confused? He’s saying the correct form in OCS would be въ зеленѣ блатѣ. The misspelled *злѣнѣ would show the writer thought зеленъ was too “Russian”, so he tried to write it as *злѣнъ thinking it sounded “more like OCS,” assuming it would follow the same pattern as (Rus.) берег/(OCS) брѣгъ. The author calls this an “anti-Russism,” I call it “trying too hard.” Fun with grammar and orthography! |

| ↟7 | jeb: ꙋ is a letter called “Uk”, borrowed from Greek, and serving as a digraph of “ου” (omicron-upsilon). It was used in early Cyrillic to represent the sound u/oo, but was later replaced with a different form, ѹ (also called “Uk”), and even later as just у. |

| ↟8 | jeb: this name refers to the names of 4 letters: ѧ (non-iotated little yus), ѩ (iotated little yus), ѫ (non-iotated big yus), ѭ (iotated big yus). |

| ↟9 | The Old Slavonic dialect is represented (aside from insignificant fragments) by in total eight manuscripts. Six of these are in Glagolitic: the Codex Zographensis (Rus. Зографское Евангелие, Zografskoe Evangelie, “Zograf Gospel”), the Codex Marianus (Rus. Мариинское Евангелие, Mariinskoe Evangelie, “Marianus Gospel”), the Codex Assemanius (Rus. Ассеманиево Евангелие, Assemanievo Evangelie, “Assemani Gospels”), the Psalterium Sinaiticum (Rus. Синайская Псалтырь, Sinajskaja Psaltyr’, “Sinai Psalter”), the Euchologium Sinaiticum (Rus. Синайский требник, Sinajskij trebnik, “Sinai Missal”), and the Glagolita Clozianus (Rus. Сборник графа Клоца, Sbornik grafa Klotsa, “the Count Cloz Collection”). Two are in Cyrillic: Sava’s Book (Rus. Саввина книга, Savvina kniga) (also known as the “Gospel-anrakos) , and the Codex Suprasliensis (Rus. Супрасльская рукопись, Suprasl’skaja rukopis’, “Suprasl Manuscript”) (a Menaion reader for the month of March). Some of the Glagolitic Kievan fragments are also of interest. |