Today, I’d like to present an article I recently finished reading by B.A. Rybakov, about the symbolism on silver cuff bracelets that are commonly found in Rus’ treasure troves from the pre-Mongol Invasion period. These cuffs, or obruchi, have two parts, are hinged, and appear to have been related to the pagan holidays of Rusalia, which continued to be celebrated well after the acceptance of Christianity, much to the Church’s dismay. In addition to dancers and musicians, these cuffs often depict a creature called a Simargl, a fantastic beast similar to the Senmurv in Persian folklore. This beast was seen as a protector of crops and vegetation, as well as the titulary protector of sailors on Rus’s riverine highways, and appears to have later become associated with a pagan god named Pereplut. Interestingly, ethnographers in the 18th and 19th centuries collected data about pagan celebrations that appear to have been remnants of those pre-Christian rites, giving us some idea how these holidays may have been celebrated in period and serving as a great example of how Russia’s long-standing dual-faith system (двоеверие / dvoeverie) preserved belief in nature spirits and pagan deities alongside Orthodox Christianity. The article also provides some great examples of designs from medieval decorative art.

Rusalia and the God Simargl-Pereplut

A translation of Рыбаков, Б.А. «Русалии и Бог Семаргл-Переплут.» Советская археология, 1967 (2), с. 91-116. / Rybakov, B.A. “Rusalii i Bog Semargl-Pereplut.” Sovietskaja arkheologija, 1967 (2), pp. 91-116.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

http://archaeolog.ru/media/books_sov_archaeology/1967_book02.pdf]

The authors of medieval Russian sermons against paganism left us many riddles. The frequently spoke in hints and omissions, not thinking it necessary to describe to their readers or listeners the pagan ritualism which surrounded them in everyday life, and they would have been completely understood.

In this regard, the writings of their Western contemporaries, the Catholic missionaries, are more detailed historical sources. There, we find descriptions of the beliefs of the Western pagan Slavs, the outward appearance of their churches and idols, detailed notes about their religious ceremonies, and the calendar dates of their holidays and prayers. The missionaries were writing for distant readers in old diocesan centers, whom they attempted to amaze not only with their descriptions of Slavic paganism, but also with stories of the triumph of Christianity, that is, of their own success. Of course, the more detailed the paganism was described, the greater the missionaries’ successes would appear.

The intent of medieval Russian sermons was completely different: they were directed not toward the church leadership, and not toward the Russian semi-pagans of the 11th-13th centuries themselves, but to that particular section of the Russian clergy which struggled with the vestiges of paganism, who adapted to the folk holidays, who allowed themselves to take part in the pagan feasts and holidays organized by their parishioners: “for the sake of drinking and eating and exchanging gifts with them,” as is said in one of the sermons.[1]Anichkov, E.A. Jazychestvo i Drevnjaja Rus’. St. Petersburg, 1914, p. 135. As a result, the Russian sermons only mention the existence of pagan rites and beliefs, but hardly ever describe them or reveal their details, leaving much unsaid and unclear. This lack of clarity raised many doubts among scholars, and they started crossing off one god after another from the relatively small Slavic pantheon. Doubts were raised first about Simargl, whom older writers turned two gods – Sima and Regla; then Makosh’ was moved to the line of Finnish gods, Khors was moved to the Iranian pantheon, and Svarog to the Indian pantheon; the god Rod[2]jeb: Primordial god of the universe and creator of all the other gods. was relegated to a minor, petty household god. Rusalki and vily (fairies) began to be seen as having been adopted from the Bulgars, and the god Pereplut, in whose honor medieval Russians danced and drank from sacred horns, was declared dubious.

In addition, the separation of study of medieval Russian paganism based on sources from the 11th-13th centuries from the study of 19th century Russian folklore, in particular the annual cycle of folk holidays, caused researchers to lose touch with the functional meaning of these or those Slavic deities. There was created a very empty, vapid formula: “The Slavs deified nature and believed in leshy (forest spirits), rusalki[3]jeb: In Slavic folklore, the rusalka (plural: rusalki; Cyrillic: русалка) is a female entity, often malicious toward mankind and frequently associated with water., vodjanye (water spirits), and domovye (house spirits)….” The magical character of their rites, prayers and offerings, which survived to the very turn of this century (for example, St. Ilya’s/Elijah’s Day), was not completely revealed; rusalki were perceived only as a poetic image. The fruitful work of ethnographers had little impact on studies of the earliest data about Slavic paganism.

A new uncharted area of knowledge about paganism blossomed once information about medieval and modern folk art came together. In 1923, V.A. Gorodtsov discovered a stable and archaic image of the Great Goddess in Northern Russian peasant embroidery, which was obviously the old Russian god Mokosh.[4]V.A. Gorodtsov. “Dako-sarmatskie elementy v russkom narodnom tvorchestve.” Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja. 1926 (1). An interesting continuation of Gorodtsov’s works are a series of articles by A.K. Ambroz, who studied the consistent symbol of fertility in the shape of a diamond/rhombus. Ambroz, A.K. “Rannezemledel’cheskij kul’tovyj simvol (‘romb s krjuchkami’).” Sovetskaja arkheologija. 1965 (3); –. “O simvolike russkoj krest’janskoj vyshivki arkhaicheskogo tipa.” Sovietskaja arkheologija. 1966 (1).[5]jeb: “Moist”, a great Earth goddess, related to the Indo-Iranian goddess Anahita.

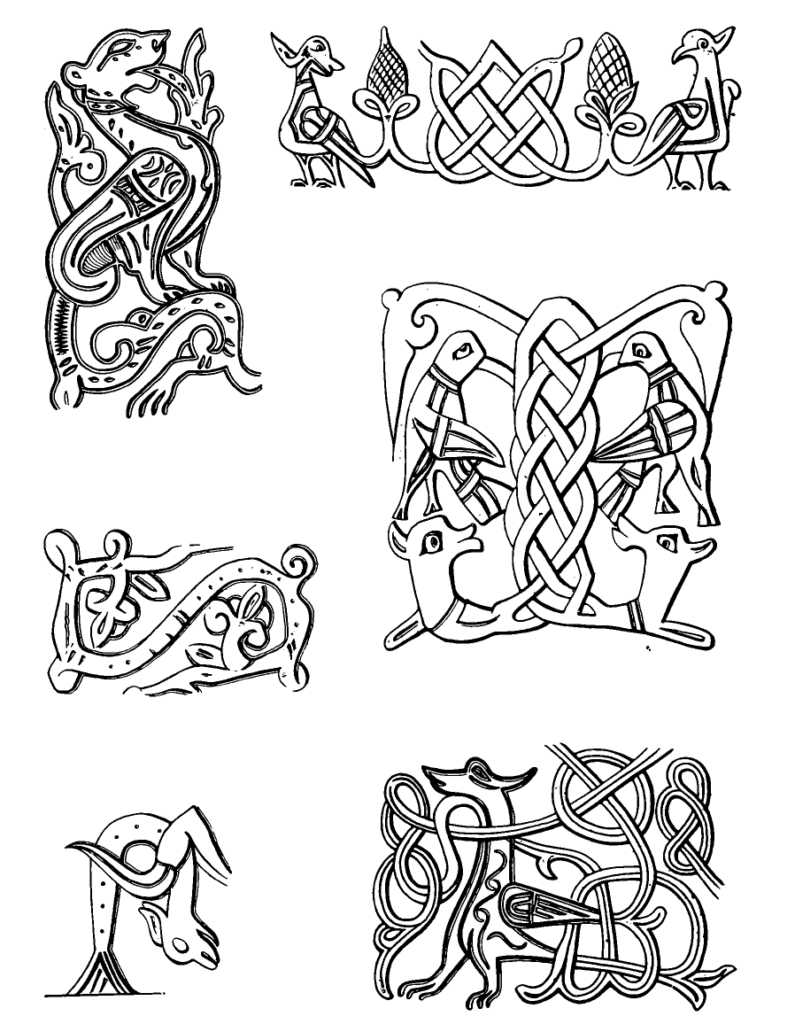

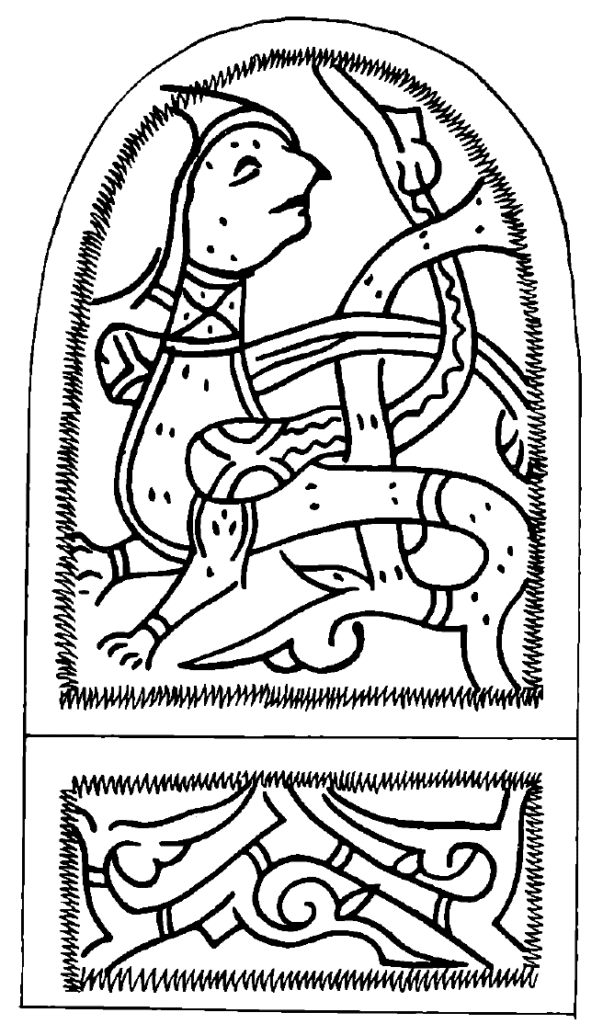

In 1933, K.V. Trever solved the riddle of the Simargl, by establishing its likeness to the Iranian Senmurv (Simurg), a sacred winged dog who was the protector of plants.[6]Trever, K.V. “Sobaka-ptitsa: Senmurv i Paskudzh.” Iz istorii dokapitalisticheskikh formatsij. Moscow-Leningrad, 1933, pp. 324-325.

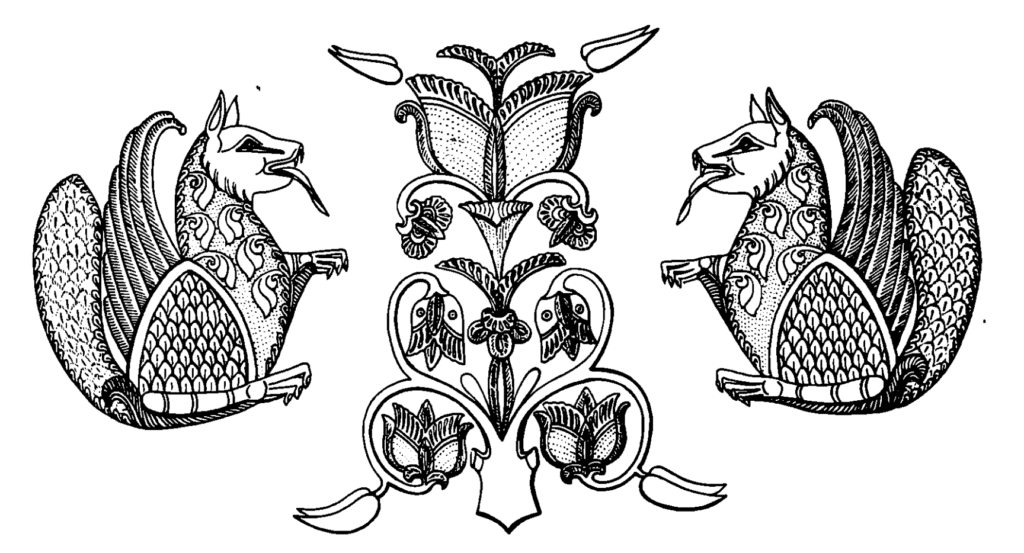

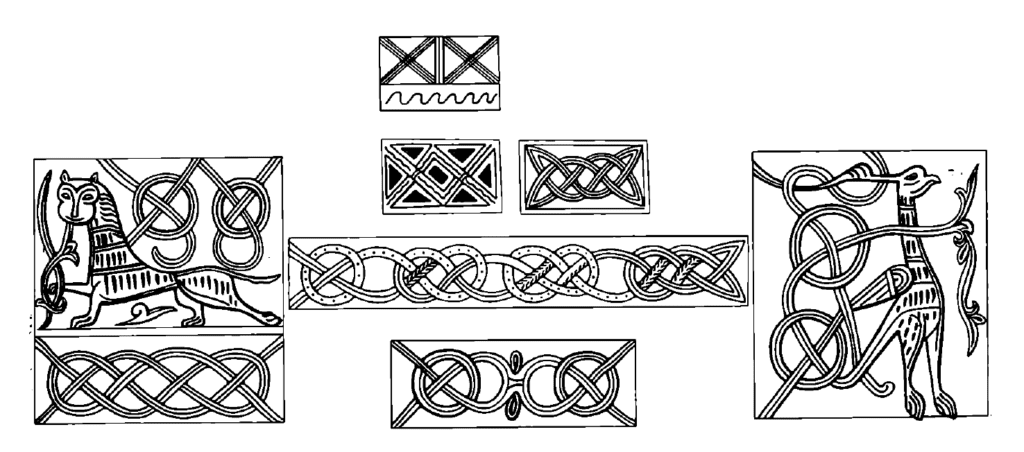

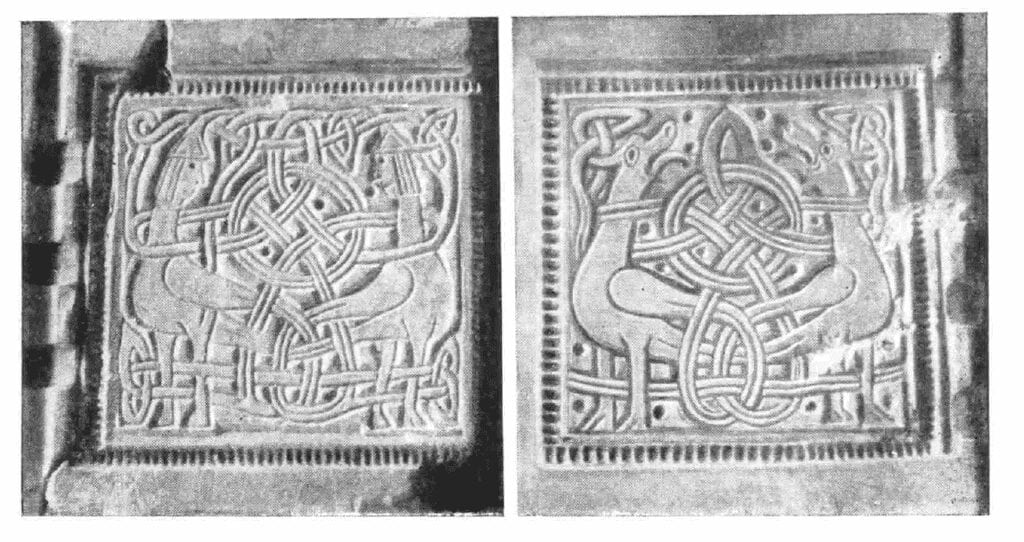

Thanks to Trever’s finding, many depictions of sacred winged-dogs in medieval art from Iran and Transcaucasia received interesting explanations (Illustration 1). It was revealed that decorative art of the medieval period (silver vessels, architectural reliefs, fabrics, etc.) were able to preserve and revive ancient images of Zoroastrianism, which permeated into both the Muslim and Christian culture. Thus, the researchers found in their very laps abundant and varied material reflecting archaic folk beliefs which were not subject to the laws of artificial literary composition.

Russian material, which was far from K.V. Trever’s sphere of interest, was not included in her interesting article, with the exception of a dish from Gnezdovo. It received here, however, its first scientific investigation, allowing us to rely on Chronicle accounts and to search for pictorial sources. “Study of the question of the Senmurv in the Chronicles must be prioritized anew.”[7]idem., p. 325.

Unfortunately, the subjects of medieval Russian decorative art (Illustration 2) have almost never been the subject of research. A.S. Guschin and G.F. Korzukhina, in their works dedicated to objects discovered in Russian treasure hoards from the 10th-13th centuries, did not examine the subjects depicted on those items.[8]Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi. Leningrad, 1936; Korzukhina, G.F. Russkie klady IX-XIII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1954.

In general reviews of the artistic craft of medieval Rus’ written by this author, there also has been no detailed examination and full semantic analysis of all aspects of this rich and bright artwork.[9]Rybakov, B.A. “Prikladnoe iskusstvo i skul’ptura.” Istorija kul’tury drevnej Rusi. История культуры древней Руси. 1951 (2), pp. 396-464; –. “Iskusstvo drevnikh slavjan.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. 1953 (1), pp. 39-94.; –. “Prikladnoe iskusstvo Kievskoj Rusi IX-XI vekov i juzhnorusskikh knjazhestv XI-XIII vekov.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. 1953 (1), pp. 233-297. Almost nothing new is added by this article: Bogusevicha, V.A. “Zobrazhenija Simargla v drevn’orus’komu mistetstvi.” Arkheologija. 1961 (XII). Here, the relief from a 12th century Chernigov capital (Illustration 4) is interpreted as a depiction of a Simargl, as are several well-known images of dragons (Illustrations 5-8), none of which can be accepted: Vagner, G.K. Skul’ptura Vladimiro-Suzdal’skoj Rusi. Moscow, 1964, pp. 120-123. Only by decrypting the ancient Slavic calendar was I able to go into a more in-depth analysis of the semantic decoration and depictions of medieval artwork.[10]Rybakov, B.A. “Kalendar’ IV v. iz zemli poljan.” Sovetskaja arkheologija. 1962 (4), pp. 66-89; –. “Slavjanskij vesennij prazdnik.” Novoe v sovetskoj arkheologii. Moscow, 1963, pp. 254-257; –. “Jazycheskaja simvolika russkikh ukrashenij XII v.” Tezisy dokladov sovetskoj delegatsii na I Mezhdunarodnom kongresse slavjanskoj arkheologii v Varshave. Moscow, 1965, pp. 64-73; –. “O chem povedala litejnaja forma.” Nauka i zhizn’. 1966 (1), pp. 29-30; –. “Khristiane ili jazychniki?” Nauka i religija. 1966 (2), pp. 46-49; –. Jazychestvo i khristianstvo v Drevnej Rusi. Tezisy dokladov na sessii Otdelenija istorii AH SSSR v 1956 g.

Archaic pagan symbolism is widely represented in both rural and urban archeological material. Of particular interest to us are gold and silver items from upper-class hoards of the 12th-early 13th century, from the same time as the Lay of Igor’s Campaign, many of the writings against paganism, and the white stone architectural carvings in Vladimir and Jur’eva-Polskij, which contain many similar motifs.

It is possible to count over 50 subjects depicted on kolts, bracelets, necklaces, and diadems from the 12th century: the tree of life, birds, lions, sirens, Fleurs de Lis, centaurs, winged dogs (Simargli), knotwork, vegetative designs, griffons, warriors, dancing women, Christian saints, the Deësis, Alexander the Great rising to Heaven on a griffon, etc. In various combinations, they make up complex compositions which only toward the early 13th century began to lose their harmony and meaning.

As seen from this list, almost none of these subjects are exclusively Russian, but rather are like the wandering plots of verbal folklore and apocrypha widely established in the art of Byzantium, Western Europe, and the Middle East. Byzantine “gold and thread”[11]jeb: Byzantium was known for its cloth of gold brocades. and Iranian fabrics and silver vessels with chased decorations for several centuries distributed these ancient subjects into European lands, where they took root and merged into medieval artwork with local archaic and, most likely, similar views about the magical, spellbinding power of images of trees, the sun, water, sprouting plants, or of fantastic benevolent monsters, endowed with the claws of a lion, the teeth of a dog and the feathers of an eagle so that they may defend all that is good.

In the Russian material, which still possesses its own specificities, there is a good answer to the most important questions which inevitably arise when one first approaches the complex and rich world of imagery in medieval decorative art: were these images embued with any meaning by their creators? Were the looked upon by contemporaries as a symbolic expression of some idea, or were they merely the result of rote duplication of earlier designs?

The coexistence of Simargli and sirens with Christian saints in the very end of the pre-Mongol period presents a strong and convincing answer to the question above: yes, the images on kolts, necklaces and cloisonné circlets was definitely tied to a kind of magical, apotropaic belief. This is natural, given that all of these most precious of items, hidden away in treasure hoards in times of danger, were most likely part of an extremely precious set of wedding attire, oversaturated with protective symbols.

The semantics of wedding rites and decorations have always been associated with a pair of beliefs: protection from evil, and the idea of fertility. The life-giving force of the bride is symbolized in the form of a young sprout, the tree of life, two birds on either side of a tree (a symbol of the wedding couple), or in the form of two winged-dogs or sirens, which should be compared to the fairies and winged female sirens (rusalki) of Slavic folklore, which ensure the fertility of the fields. Since the most ancient of times, the image of grain ripening in the fields has been intertwined in the farmers’ minds with the image of woman awaiting the birth of her child. On golden kolts, in addition to vegetative designs, we often encounter the image of a young woman wearing expensive headdresses. The wedding rites are likewise associated with images of ripe hops and cornucopias, which are also encountered on kolts.

Ancient dualism divided the world of secret forces into good and evil spirits, into “ghouls” and “bereginjas“[12]jeb: Gods of waters and of the riverbank, protectors of the Earth., and is also seen in the decoration of medieval jewelry. If the forces of good are represented here by the magic of fertility in a generalized sense (the “plant-woman” image), then protective magic against evil is also seen in the form of well-armed and benevolent monsters: griffons with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion (known in the Dnieper River region since Scythian times), winged two-legged dogs, and four-legged winged leopards with open jaws and one paw raised against the enemy. All of these symbols can be seen as hearkening back to the Simargl, protector of the world tree.

It is important to recognize one thing: on the very expensive, golden attire found in these troves, which can be interpreted as specifically as wedding or ceremonial robes for the Russian princesses (as opposed to the silver items in the same hoards), we never see the pagan Simargl depicted in any fashion, which no doubt is tied to the bride being required to wear this ceremonial outfit in church for the wedding. The array of symbols for these outfits almost never strays beyond the borders of Christian apocryphal folklore, a series of familiar images approved by Christianity: the tree of life, Fleurs de Lis, behaloed sirens, and flourishing crosses. Precisely here, on golden kolts and crowns, we see the first enameled depictions of Christian saints crowding out semi-pagan symbols.

We look differently upon the silver utensils used to serve the same individuals in the feudal upper class as everyday use, or possibly belonging to a more democratic societal layer. Here, the primary image is of the dualistic juxtaposition of good and evil: birds, the tree of life, and its protector the intimidating Simargl with open wings and a raised paw. On silver kolts, we never see Christian saints depicted.

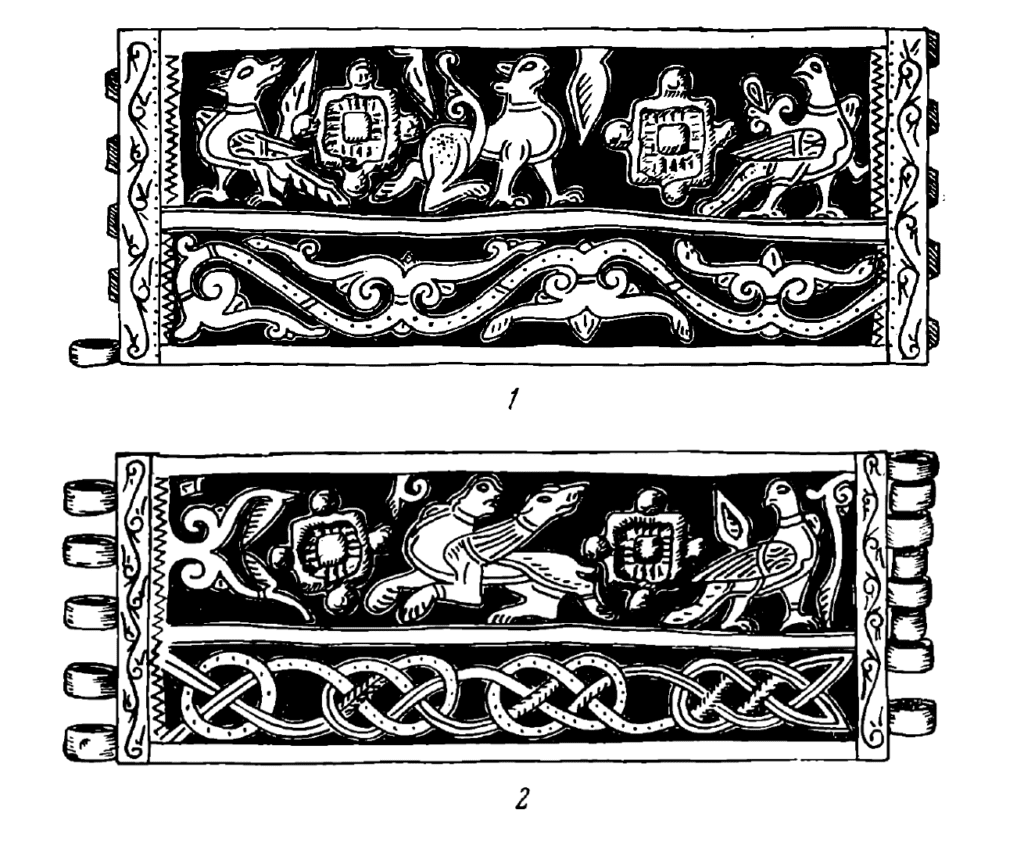

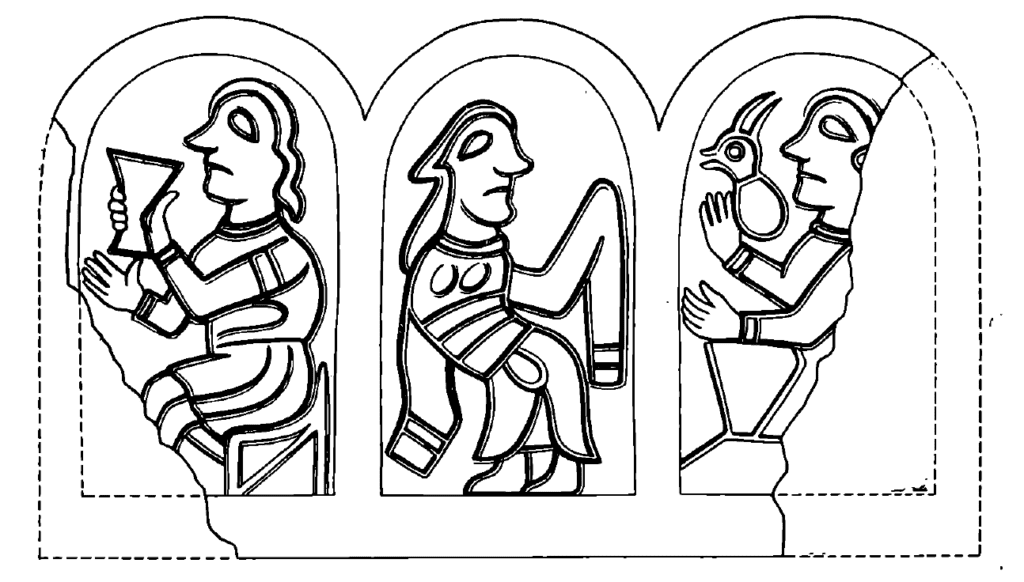

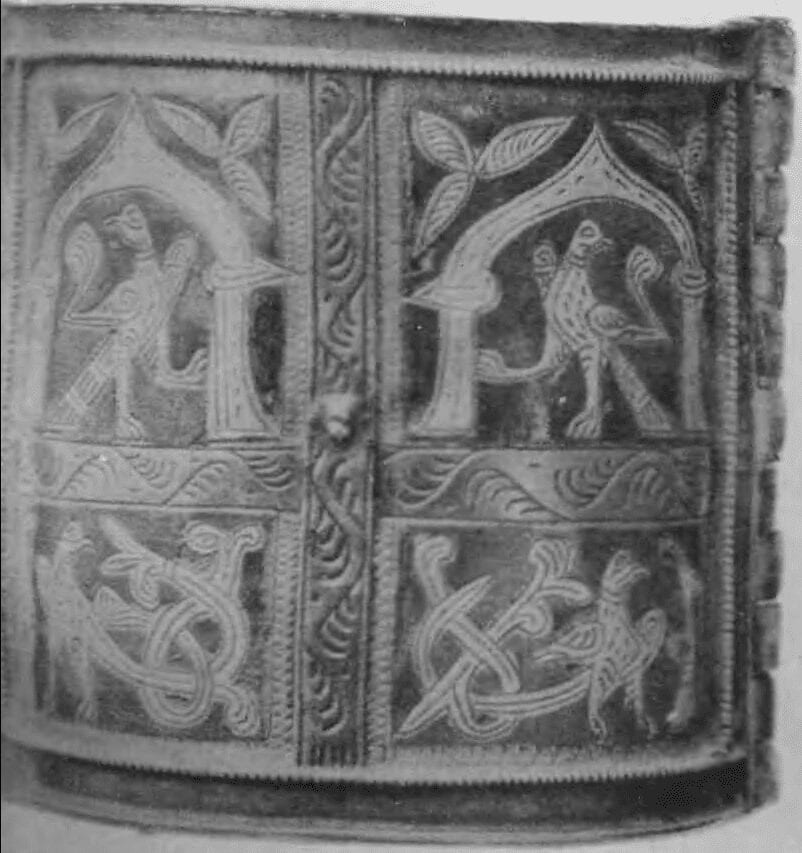

From Russian silver jewelry from the 12th-early 13th century, of particular interest for the study of paganism and pagan symbolism are the well-known wide, two-part bracelets which served to hold up one’s sleeves at the wrist. Here too we never see Christian images, even though many of these cuffs have been found in wealthy princely troves. Pagan symbolism is presented here in abundance, most likely due to the cuffs’ particular functional role as a “protector” of the sleeves (Illustration 3).[13]Here, we must revive the medieval Russian word for a bracelet, obruch, which for some reason is also sometimes perceived to mean a neck torc. In sources from the 12th-14th centuries, obruchi are clearly distinguished from torcs: “… obruchi, torcs, rings, and temple rings,” “place your obruchi upon your arm,” “on her hands there were golden rings and obruchi,” “torcs were worn upon the neck, and obruchi upon the arm.” Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevnerusskogo jazyka. Vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1903, column 550. Etymologically, obruch is related to ruka (“hand”, “arm”), thus its other meanings appear to have been of later origin.

Our first encounter with obruchi in the Chronicles immediately ties them to pagan rituals: in Prince Igor’s treaty with Byzantium in 944, the Russian pagans’ oath appears, tantamount to kissing a cross in church: “… but the unbaptized Rus’ believe in carrying their swords and shields, their obruchi and other weapons (on Perun Hill)…”[14]Povest vremennykh let. Moscow-Leningrad, 1950, p. 38.[15]jeb: Perun Hill is a tall bluff overlooking the Dnieper in Kiev, where the pagan Rus’ erected statues of their pantheon of deities. When Rus’ officially accepted Christianity in 988, Prince Vladimir I had these statues torn down, dragged through the streets, and then chucked into the river as a symbolic baptism.

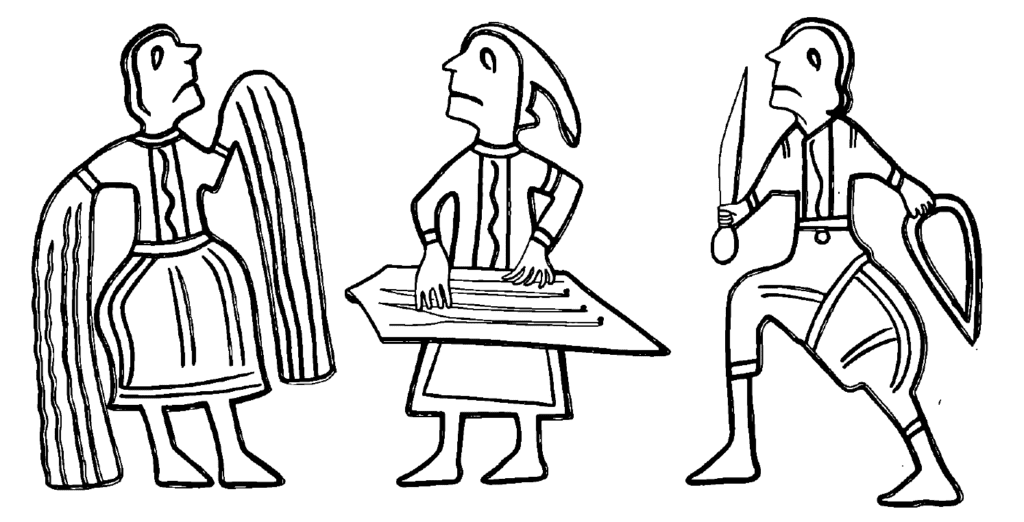

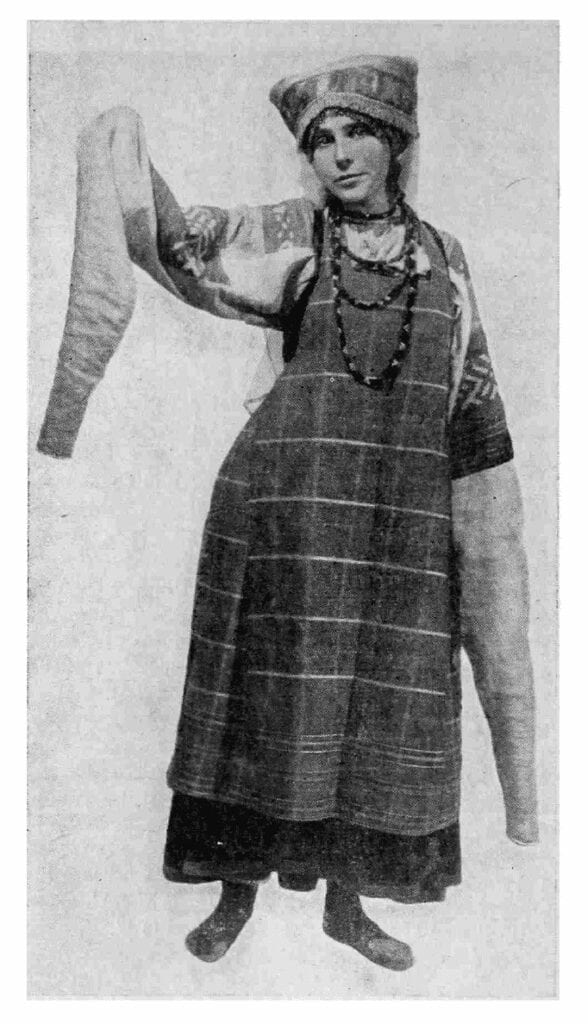

The 12th-13th century bracelets known to us belong to female apparel and, it appears, were associated with a particular type of Russian dress which was still worn by dancers during festivals right up to the early 20th century, a long tunic with very long sleeves, reaching almost to the floor (Illustration 4). Prior to dancing, the young woman would have to tie back these long sleeves at the wrist using two-sided articulated cuffs adapted for this specific purpose. Before dancing, in order to let out her long sleeves, the dancer would unfasten and remove these cuffs. This explains the pairing and completeness of the cuffs found in troves. This festival dance “of the loosened sleeves” is documented in a famous miniature from the Radziwiłł Chronicle, captioned “Merrymaking” (Illustration 5). This type of dancer with long sleeves is also seen in the fairytale of the Frog Princess: the young bride of the prince hides bones and pieces of food from the feast in her sleeves. When she goes to dance, lets out her sleeves and begins to wave them about, she scatters what she has collected, which are magically transformed into trees, water and birds.

Of particular interest is the fact that these bracelets often depict women in dresses with long, loose sleeves. Here we see both women with gathered sleeves (in which case the artisan always show bracelets gathering these sleeves at the wrist), as well as women dancing with loosened sleeves, as if transforming the dancer into a winged fairy or bird-woman swinging her white wings.

If these silver cuffs never showed any other pagan depictions other than dancers, then it would be easily understood why the Christian saints are absent on them: the cuffs were intended not for churchgoing, but rather for the complete opposite purpose. It was not without reason that 11th and 12th century preachers bitterly spoke that their contemporaries lived “without hearing the word of God, but rather dancing and playing the gusli, or calling to gather for merrymaking or celebrating heathen festivals – they all go thither to be merry.”[16]Gal’kovskij, N. Bor’ba khristianstva s ostatkami jazychestva v drevnej Rusi. Moscow, 1913, p. 82, “Slovo o tvari.” And, there was no object more scourged by the Christian preachers than a woman who participated in dances: “One who dances is the bride and wife of Satan, the acclaimed and beloved of the devil, and the spouse of demons…”. Demons seduce people into various sins, “and tempt them to dance, where everything is evil and bitter,” for it is dancing is most pleasing to the devil, in that it turns men away from God and leads them “to the depths of hell.”[17]idem., p. 188, “Pouchenie Ioanna Zlatousta o igrakh i pljasanii.”

Women dancing to accompaniment on the gusli was seen as the clearest manifestation of paganism, and as the most severe transgression: “Where is it written that Christians to commit evil deeds? Yea if you collect all the books from the world, are the faithful ever commanded to play the gusli and dance? No, this is the essence of the matter — their eternal torment and trial by fire.”[18]idem., p. 195.

How shall we explain this frenzied pursuit against everyday folk entertainment? We can assume that dancing to the gusli was not as innocent as it may sound, from the Christian point of view. Much may be clarified by taking a closer look at the medieval Russian Rusalias, which were always compared to “heathen merrymaking.”

In medieval Rus’, Rusalia was the culmination point of the pagan folk festivities. All manner of art was manifested in this: music, singing, dance, martial games, and theatrical works which were sometimes performed in masks. The participants of these holidays, one can assume, were everyday citizens, along with specific people who carried out specific roles in the games or rites, just as how even recently in modern-day Bulgaria, a village’s solemn New Year celebrations were performed by 12 “elders” in enormous masks and ceremonial robes.

The non-Christian, heathen essence of Rusalia appears even in its first mention in the Chronicles. Such a great all-Russian misfortune as the invasion by the Polovtsians led by Sharukan in 1068 was regarded by the chroniclers to be a manifestation of God’s anger caused by the fact that the Russian people had (during a time of drought) turned against their new Christian God and returned to the old gods of their grandfathers: “I shall keep the rain from you,” the Christian God tells the people. “Turn to me and I shall turn to you, saeth the Lord, and I shall open the gates of Heaven for you.” “The devil tempts us,” the author of the sermon states through the chronicler, “leading us away from God with trumpets and skomorokhi, guslis and Rusalias.” “We see that the festivals are thickened with a multitude of people… but the churches stand. Whenever there is a year of prayer, few of them are found in church. Lo, for this very reason, we receive all kinds of impure misfortune from God, including these soldiers… due to our sin.”[19]Povest vremennykh let, pp. 112-114. The chronicler Nikon the Great used here a particular essay, “A Word about the Drought and the Decimations of God.”

A hundred years later, Kirill of Turov included in a list “of evil and impure deeds, which Christ commands us to give up” “dancing, cymbals, flutes, guslis, impure games, and Rusalias.” Another writer from the same period writes that hellish torments shall punish “games, wild talk, skomorokhs, and Rusalia dances, and all devilish merrymaking.” A 13th century Izbornik cautions: “Whenever Rusalias or skomorokhs play, or dancers call, or there are heathen games, get thee home that very hour!” All of this was written in the same century when ecclesiastic painters boldly depicted in miniatures in liturgical books the bells and flutes and trumpets of the holy King David. It is apparent, then, that the problem lay not in the music itself, but in its religious direction: “The demons of Satan, having gathered, turn into humans and come together in a great number, and having placed great leather masks upon their faces, and perform a mockery of mankind. And the multitude, having left the church, come together at this spectacle, which are called Rusalias.”[20]Sreznevskij, I.I. Materialy dlja slovarja drevnerusskogo jazyka. Vol. III. St. Petersburg, 1903, col. 197; Gal’kovskij, N. Op. cit. Sometimes, this condemnation was stated quite succinctly: “His sin was dancing and Rusalias.”[21]Sreznevskij, op. cit.

In order to understand the essence of Rusalia and the reasons for its competition against Christian worship, it is necessary to look at the timing of pagan holidays. The Stoglav provides this interesting information: “Rusalias: on St. John’s Day, and the evening before Christ’s birth and Epiphany: men and women and girls go out to evening celebration and wild talk and demonic songs and dancing and stories and other impure activities.”[22]“Tsarskie voprosy i sobornye otvety v mnogorazlichnykh tserkovnykh chinakh.” Stoglav. Moscow, 1890, Question 24.

Missing from this list are Rusalias held during “Semik week,” which seems to come from the term Semik (the seventh Thursday after Maundy Thursday), which by this time had already established itself and overshadowed a more ancient word for Rusalia. A Kievan chronicle from the 12th century tracks the time of Rusalias tied specifically to Semik (1174, 1177, 1195). The Chronicles call the seventh week after Easter “Rusalia week”, ending with the feasts of the Trinity (the seventh Sunday) and the Descent of the Holy Spirit (Whitsunday or Pentecost).

The word Rusalia so firmly entered the everyday life of 12th century Rus’ that even in a list of purely Christian feasts, we see this mention: “… and for the Descent of the Holy Spirit, that is, Rusalia…” “… and butter is acceptable up until Rusalia…”[23]Sreznevskij, op. cit.

Thus, we’re able to discern four calendar dates for rusalii, divided into two seasonal groups. The first group is Christmastide: Christmas eve (the eve before December 25), and the evening before Epiphany (the evening before January 6), famous for its fortune telling. The second group are the summer holidays, or the so-called “Green Christmastide:” Semik and Ivan Kupala Night (the night before the 24th of June). Let us leave aside for now the rural 12th century “Rusalia week,” as its pagan dates were certainly shifted from their original spot by the fluid Easter calendar, leading to the destruction of the “Rusalia Trinity” by the time Stoglav Cathedral was built. The three remaining dates coincide with the three most important church holidays (Christmas, Epiphany, St. John’s Day), and what’s more, two of them with the phases of the sun, the winter and summer solstices.

Independent from one another, Christianity and Slavic paganism included in their religious calendars the solar phases, including the winter turn of the sun toward summer (called Korochun), tied to the idea of the death and resurrection of God, and the boundary of the summer solstice, falling on the longest day of the year. The holiday of Epiphany (January 6) was tied to the “heating up” of the sun, and appears to have been determined by adding 12 days (the number of months in the year) to the date of Christmas (Koljada), when a spell for good weather and luck was made for the 12 months of the upcoming year. In Slavic lands, the last day of the 12 days of Christmas is firmly associated with the spells of water (Vodokreschi).

The winter Rusalias “on the eves of Christmas and Epiphany” began and finished the Christmastide new year cycle of spell-casting rites, at the center of which were the blessing of the bread, the spell of the 12 wells, fortune-telling the harvest from 12 sheaves of wheat, and the girls fortune-telling about marriage.[24]Chicherov, V.I. Zimnij period russkogo zemledel’cheskogo kalendarja XVI-XIX vekov. Moscow, 1957.

Judging by the Chronicles, the main time of year for Rusalia was summer, which by the 12th century had already adjusted to the Christian trinity and the firmly fixed date of the summer solstice, the day of Kupala (the birth of John the Baptist). It is not surprising that medieval churchmen so sharply and stubbornly protested against the pagan merrymaking and Rusalias which were held on these most important of Christian holidays.

The character of Rusalia, as described by the articles written by church writers, does not leave any doubts of their pagan ritual essence, which is easily traceable using ethnographical data from the 19th century. Rusalias were “great gatherings” of a large number of people dressed in bright, festive outfits. The gathering would occur “in the city,” “on the squares” (that is, immediately near Christian churches) at night. The presence of particular individuals who organized the greater part of the festivities is obvious. There were musicians, playing on string, wind and percussion instruments, gusli players, and skomorokhs wearing “skuraty” (masks), and mimicking the other people. In addition, there were dancers, who were not part of the skomorokh group and were selected, it appears, from the most beautiful of the girls from the city or village, as was done throughout medieval Europe during the May and Trinity holidays when they would select a holiday queen and king. The “wild talk”, “jumping”, “dancing” and “mockery” were performed for the benefit of those attending.

Aside from the Rusalia dancing and jumping, the Rusalias included some kind of pagan rites, which unfortunately are not described by the church authors, aside from generalized so-called “demonic merrymaking,” “idolatrous games,” and “unbelievable festivity.” Only once are dolls mentioned, which reminds us of the ethnographically famous burials of effigies of Kostroma, Kostrubon’ka, and a phallic “doll” of Jarilo. Sometimes, the Rusalias were accompanied by a kind of primitive tournament, when people, “keeping the demonic customs of the damned Hellenes,” would start “on the saintly holidays various kinds of disgraceful games, with whistling and crying out and yelling like some kind of drunkard, and thrashing each other almost unto death.”[25]Niederle, Lubor. Slovanske Starozitnosti. II (1), 1924, p. 261. We likewise recall that in Rus’, tournaments were also called “games”. “Axes,” according to Dmitrij Donskoj’s tutor, “are used to beat others during a tourney.” Troitskij Chronicle, 1390.

Great interest in this relationship is presented by Bulgarian ethnographic works about rusalki, Rusalias and special servants in the cult of the rusalka, called “rusaltsi” collected by D. Marinov. “Rusalki are female creatures, very beautiful women with long hair and wings.” They live on the edges of the world, and only come to us once year in the spring, at the right time to irrigate the grain-growing fields with rain. They pour dew from a horn, and the grain begins to sprout. The fertility of the fields relies on these rusalki.[26]Marinov, D. Narodna vera i religiozni obichai. Sofia, 1914, p. 191. The rusalka has dual functions: on one hand, they look after the rain and irrigation of the fields; on the other, they look over the pollination of flowering grains of wheat when the fields glow, as if it were their marriage celebration.[27]idem., p 476. All of this occurs in June, which is also called “rusalka month” (rusalskaja mesjatsa).

Rusalia week, which in Bulgaria starts on the Day of the Trinity, was observed in the strictest manner. The slightest violation would cause the guilty person to fall ill with Rusalia sickness. They would be unable to work, forbidden from visiting the rusalka wells or sleeping under a sacred tree. All people were expected to participate in the Rusalia merrymaking.

Bulgarian ethnography preserved extremely valuable information about a particular pagan priesthood, the 19th century wizards called rusal’tsi who led the merrymaking during Rusalia Week. In their magical spells, we see two particular elements tied to the dual functions of the rusalka: water and grass, and magical potions.[28]idem., pp. 476-486.

Squads of rusaltsi (from 3-13 people) were formed from the local peasants, but acceptance into the rusaltsi was based on almost the same complex rites as those in a Masonic lodge. All affairs were decided by a leader (“vatafin”), who was obeyed unquestioningly. In everyday life, he was just one of the village inhabitants, but he was distinguished by a strictly limited hereditary title. The leader-vatavin was the main participant in Rusalias; without him, the Rusalia holiday could not be carried out, just as a church service could not be held without a priest. Only the vatafin could select the magical herbs used for Rusalia, only he knew all the spells, he would sanctify the banners, lead the games, and the samovili (woodland fairies) and rusalki would obey only him. Only he could select new priests and sanctify them. Only respected, honorable men who did not drink and were good family men, able to dance and jump could become rusaltsi. He was required to yield to the hypnotic power of the leader and to strictly preserve the rusalets secrets. It took weeks to collect information about a candidate. They neophyte would be given a mentor and forced to fast for 3-7 days, after which he would stand in the middle of a circle of elders, who blessed him by sprinkling him with holy water blessed with sacred herbs, and he would give a sacred oath to perform all the duties of a rusalets and to keep secret its secrets. The oath began with a sacred curse against breaking his vows: “May the fire in my hearth go out, may snakes and lizards lay their eggs in it…”, and ended with no less severe a curse: “May the earth refuse my bones….”

Before Rusalia, the leader-wizard would call together the rusaltsi and prepare before their eyes a new flag, made from new canvas, with sacred herbs sewn into the corners (including perunika – blue irises), which was then blessed with sacred water; he would then give to the rusaltsy the tojagi, sacred wands about 1-1.5 meters in length which often were passed down from father to son, which he kept in his possession and which were also blessed with holy herbs. Other mandatory accessories for Rusalias were an earthen vessel filled with holy herbs which would be shattered with a blow from a wand at the end of the ritual, and a cup filled with a garlic infusion, which the rusaltsy would drink during a ritual dance. The same infusion was also given to the sick as medicine. This veneration of garlic was also mentioned in medieval Russian sermons, and a blessed pot broken into shards was found by M.A. Tikhanovaja in a 4th century sanctuary. On their heads, the rusaltsy would wear wreaths interwoven with flowers that were sacred to the woodland fairies, and on their belts and shoes they would wear bells, which rang whenever they walked or danced.

An ever-present participant in Rusalia was a flautist (svirets or svirach) who knew the particular melodies of the fairies or rusalki. The cohort of rusaltsi would travel from village to village making the rounds, so that at the end of the Rusalia Week, they would return to the village where their leader lived. “There, where they began, the fields would be in bloom, promising a good harvest.”[29]idem., p. 477. Throughout Rusalia week, the rusaltsy would neither be Baptized or pray according to Christianity under any circumstances. The Rusalia “games” consisted of round dances (“khoro“), and various kinds of dancing and jumping, as mentioned in the Stoglav. The dances were carried out in a quick, frantic pace, in which it would appear that the rusaltsy did not touch the ground. The primary motif was “the most varied kinds of wriggling about,”[30]idem., p. 482. which reminds one of the “multiple kinds of dancing” scourged by 11th-12th century Russian churchmen. The dance was accompanied by whoops and screams. The dance would end with “the rusaltsy would go into a frenzy and fall unconscious.” The final melody of the dance bore the characteristic name of “florichika“, emphasizing the agrarian-magical nature of the Rusalia games.

[Modern] Bulgarian Rusalias help us imagine the appearance of medieval Russian wizards from the 11th century. Even in 17th century Rus’, belief in rusalki was called “magic and witchcraft.”[31]Snegirev, I. Russkie prostonarodnye prazdniki i suevernye obrjady. Vol. IV. Moscow, 1839, p. 5.

Echoes of medieval Rusalias have also been preserved in Russia. S.V. Maksimov reports that after Trinity Day, peasants in the Penza region arranged a reception and sending off for the rusalki: young boys dressed up as goats, pigs and horses, wore masks and danced and jumped about to music and the banging of pots and pans, traveling from village to village. At the head of this procession of rusal’schiki they often would carry a stuffed horse with a real horse’s skull on a pole; the crowd would travel to a field on the outskirts of town, where “in honor of the rusalki, a perky girl was selected, who would jump back and forth with sticks in her hand.” Sometimes the whole rite would take place in a rye field.[32]Maksimov, S.V. Nechistaja, nevedomaja i krestnaja sila. St. Petersburg, 1903, p. 101-102, 460-462. During Rusalia Week, “men would start to ‘rusal’nik‘ about, that is, to wander about in all directions and to drink during the entire all-saints week.”

The heathen character of Semik festivities right up to the early 19th century: in the Voronezh province, on the shore of Lake Gorokhovo in the middle of an oak grove, they would build during this time a kind of pagan temple, “and decorated it with wreaths of flowers and of fragrant greenery; in the center, on a raised spot, they put an effigy made of wood or straw, dressed in festive garb. The local residents would gather near the hut, having brought with them particular kinds of food and drink. They would sing and dance in a circle around the hut, which represented a kind of temple.”[33]Snegirev, I, op. cit., vol. III, pp. 106-107, citing a “Ukrainian journal” from 1834, chap. 11, Khar’kov.

Rusalia appears to be a common Slavic (and possibly even a common Indo-European) agrarian holiday, tied to the fertility of the fields, as well as prayers for rain and for the young plant shoots. Scholars have long noted the similarity of the rites and holidays for the month of June: Semik, Whitsunday, and Kupala Night. Folk poetry also united the three:

"Thus we have three holidays a year:

The first holiday is fair Semik,

The second holiday is Whitsunday,

The third holiday is Kupal'nitsa."[34]Snegirev, op. cit., vol. III, p. 125.

In each of these holidays, we clearly see a cult of water, vegetation, and fertility. The dancing girls, the dances around birch trees, the weaving of wreaths and tossing them into water, the songs about the Spring wheat and the future harvest, about Jar-Khmel[35]jeb: A pagan god of the springtime. Khmel’ is the Russian word for “hops”., and about young men and women, the imitation of coitus, the entreaties to the rusalki, Lado, Lel’, Tur, and Jarilo[36]jeb: More pagan gods associated with springtime and nature. Jarilo, in particular, was a Slavic sun god., the offerings to water in the form of female dolls, and the funeral rites for male effigies (Kostroma, Kostrubon’ka, Jarilo) — all of these typically occurred between June 4th and June 30th. Confusion over the timing of these rites arose, first of all, due to geography (the further north, the later the rites would take place), and secondly due to the ecclesiastical calendar with its variable dates for Easter and Whitsunday, and the shifting dates for the pagan Semik and Rusalia Week holidays. Some of the more stable Kupala rituals were tied to a specific date: June 24th. These repeated all the details of the Rusalia holidays, but also included their own particular traits as the celebration for the Summer solstice: bonfires on the banks of rivers and on mountaintops, and a special “sun-chariot” with two wheels (the chariots used during Shrovetide rituals always had only one wheel). The young girls, “having seized the front wheel of the cart, would sit upon the axle, and what’s more, having grabbed the shaft, they would ride about the town, and then around the fields singing songs until the dawn, when they would wash themselves with dew for good health.”[37]Snegirev, op. cit., vol. III, p. 125.

The Kupala, Semik, and Rusalia rites were united by the image of Jarilo,[38]jeb: Slavic god of fertility., in whose honor celebrations occurred in various locations throughout the month of June, between June 4 and June 30.

A celebration of Jarilo held in Voronezh and written about in 1763 was very similar to the various Bulgarian Rusalias described above: “the townsfolk and the villagers living nearby flocked to the central square, and set up a kind of fair. There were preparations in houses throughout the town, as if for a great holiday. In the square, the crowd would elect a man, who was tied with all kinds of flowers and ribbons, and who was bedecked with bells. Upon his head was placed a tall hat, and into his hands they placed some noisemakers. In this outfit, he would go around the square in Jarilo’s name, dancing and accompanied by townsfolk on every side. This celebration also included games, dancing, feasting and drinking, and fistfights… They called this merrymaking, Everyone looks forward to it like an annual celebration… and gather wearing their finest outfits.”[39]idem., p. 59. In some cases, the image of Jarilo was given fantastic features. This was especially true for Jarilo’s funeral which, it appears, represented the final death of the grain which had been sown into the Earth and a period for the formation of new shoots.

These lines bring us back to six centuries ago, to the medieval Russian denunciations of Rusalia, when “the people dressed in bright colors to gather on the city streets and gave themselves over to heathen merrymaking.”

Jarilo Day, celebrated in the 19th century on the 4th of June, corresponds to a great pagan festival of the Pomor Slavs, which was celebrated in the 12th century on the same date. In 1121, Sefrid recorded that there was a riotous nighttime celebration near the city of Piritso: “having gotten close, we saw nearly 4000 people who had gathered together from every side. It was some kind of pagan holiday, and we grew afraid, seeing how the mindless crowd celebrated it with games, voluptuous body movements, songs, and loud cries.”[40]Famintsyn, A.S. Bozhestva drevnikh slavjan. St. Petersburg, 1884, p. 51.

The pagan, ritualistic character of Rusalia is sufficiently confirmed by ethnographically-gathered examples. In order to examine the images on silver vessels presumed to be associated with Rusalia merrymaking, we need only attempt to define the number and timing of the June holidays in the pre-Christian era, that is, before their timing became affected by the movable dates of Easter, which may fluctuate by up to an entire month. It is particularly important to determine the original date of Semik, which in Ukraine was called “the Great Day of Rusalia“, or Rusalia Easter.

According to the Christian calendar, Semik could fall in different years anywhere from mid-May to mid-June. The only source which clarifies this is an exquisite 4th century urn-calendar found in the village of Romashki on the Kievschina.[41]Ribakov, B.A. “Kalendar’ IV v. iz zemli poljan.” Sovietskaja Arkheologija. 1962 (4), pp. 66-89. It precisely lays out 4 periods of rain essential for spring crops. They coincide with the optimal times for rains according to agronomical data from the 19th century. Between these rains, the urn has signs for the 3 most important holidays: a tree for June 4, two crosses for June 24, and a sign for thunder on July 20, on the eve of the harvest.

Kupala Day, marked by the dual crosses, was preceded by a 6-day period, indicated by special symbols. The juxtaposition of ethnographical data onto the calendar grid of the Antae civilization allows us to determine the pagan holidays as follows: on June 4, before the first rains, Jarilo Day was celebrated; these were the first Rusalia, associated later with Semik and Whitsunday. The second Rusalia started on June 19 and ended, as they did in the time of the Stoglav, on June 24. The holiday for the god of thunder had no relationship to Rusalia. Judging by the clearly distinguished marks for June 19-24, the second Rusalia, associated with Kupala and the summer solstice, was clearly most important in those long-ago times. We are able to guess the importance of this holiday by the fact that on a second calendar-vessel from the same time period, the month of June is indicated by Kupala symbolism – 2 oblique crosses and a wavy line indicating water. The crosses in this situation express the idea of the Sun-Svarog[42]jeb: Svarog was the Slavic sun god. and the bonfire lit in his honor. The role of water in the Kupala rights is obvious.[43]jeb: Kupala was a goddess of joy and water, celebrated with purification rituals involving fire and water. The name “Kupala” is thought to be related to the verb kupati, “to wet”. This explains how Kupala Night became associated with John the Baptist during the conversion to Christianity.

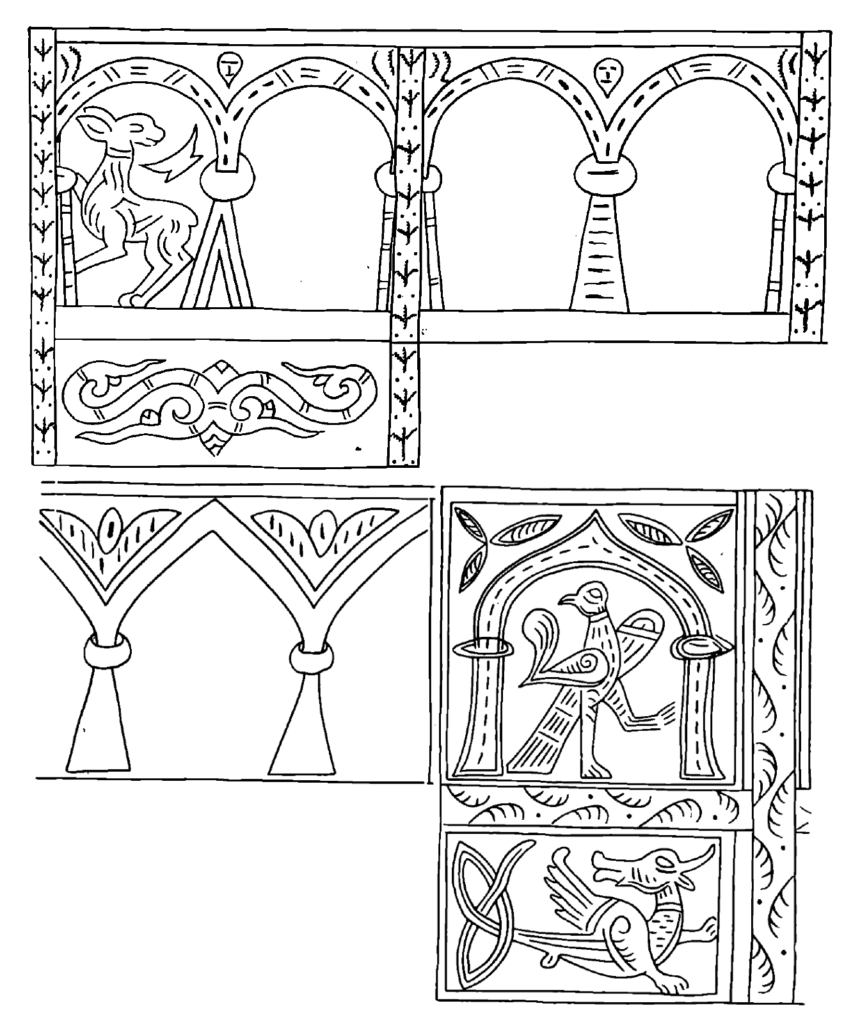

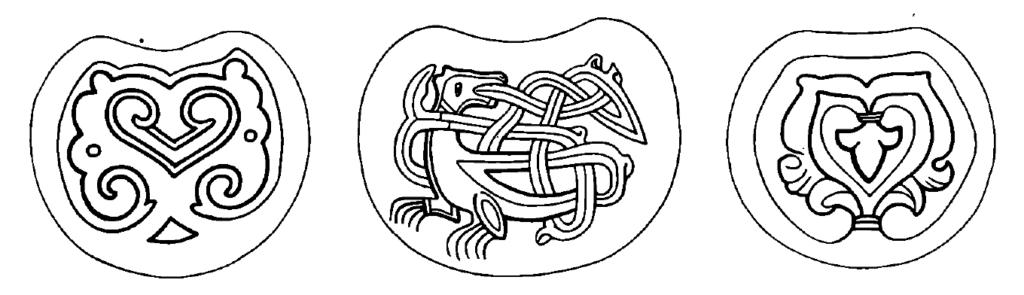

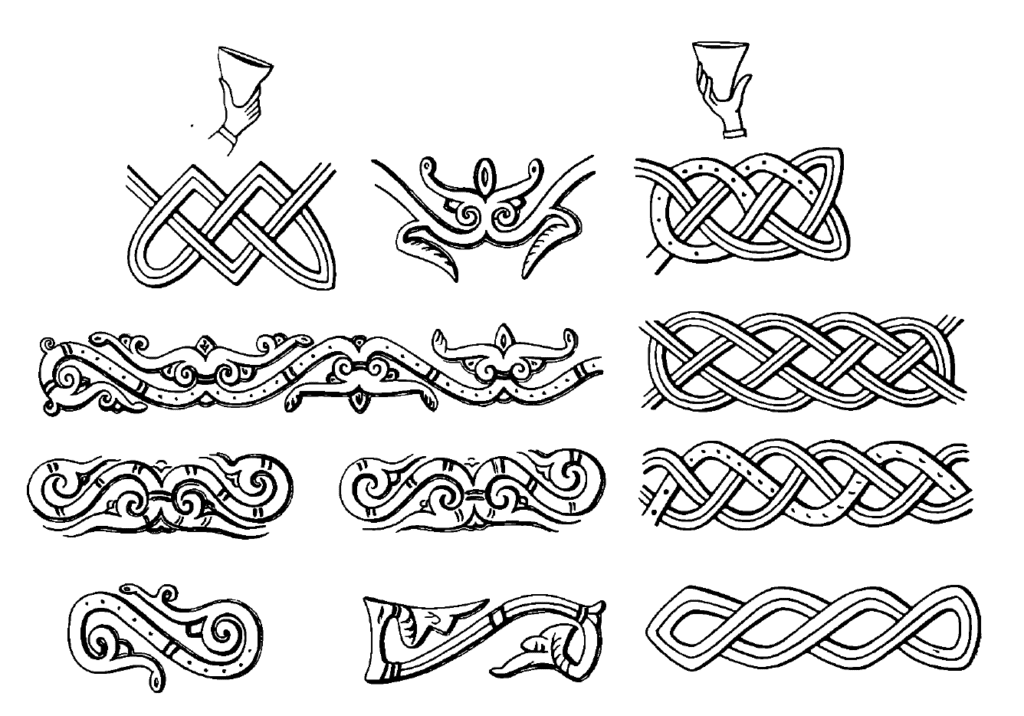

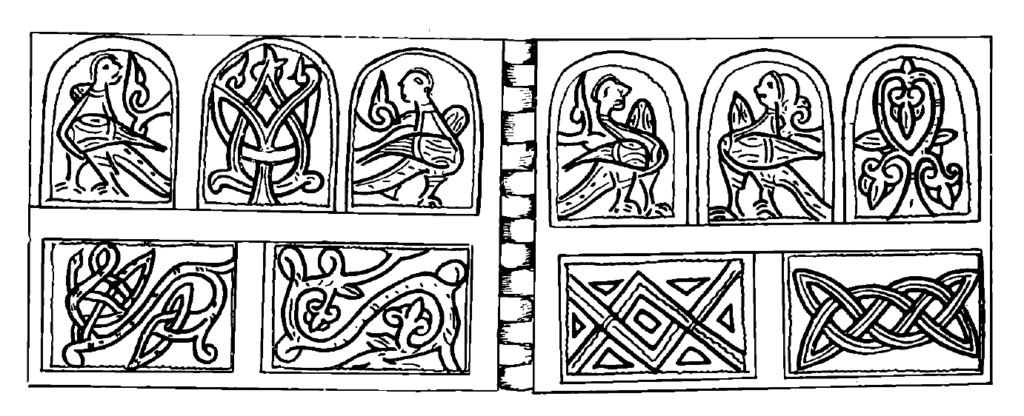

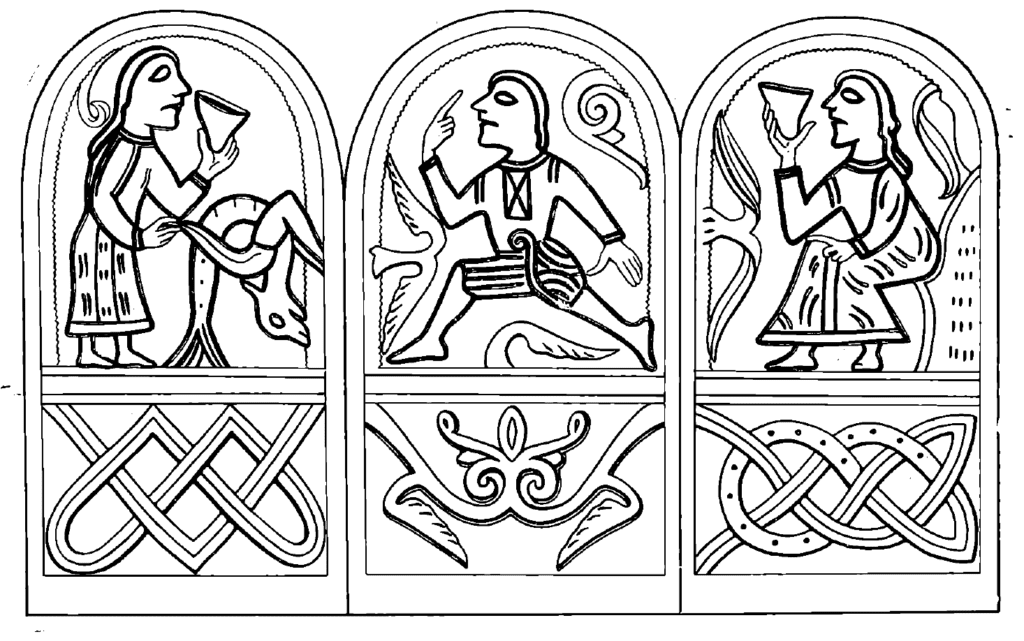

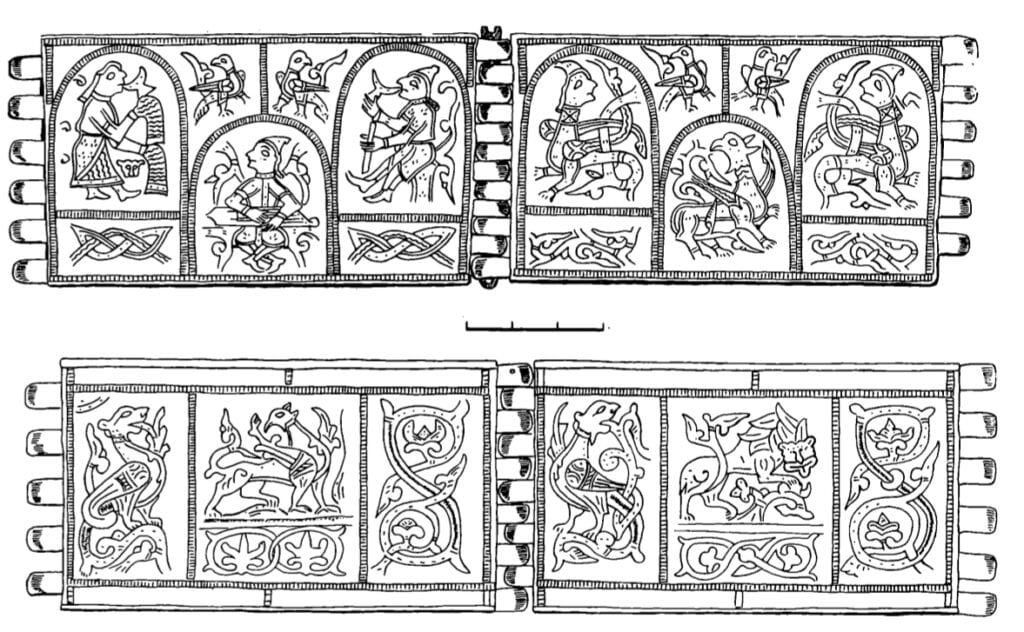

The information above is sufficient to allow us to return anew to the bracelets of interest. These wide, two-part silver cuff bracelets are found in almost all wealthy Rus’ troves from 1170-1240 buried during Batu Khan’s invasion. Most often, each of the sides was divided into 2 or 3 arches, with birds, sirens, the tree of life, centaurs, musicians, dancing or singing men or women, lions, or griffons engraved within. Sometimes these arches would stretch over the entire surface, but in the majority of cases, the decoration is divided into two rows: arches with figures in the upper row, and on the lower row, a series of rectangular stamps representing, as it were, the base for each archway. The character engraved onto the upper row rarely matches the one in the lower row, although often a semantic relationship between the two can be seen. In this lower row, 12th century artisans placed knotwork and vegetative patterns (Illustration 6). The knotwork comes in two forms: one of these is uniform braiding in the form of a pigtail with three strands; the other is a more unique kind of braid which includes weaving a circle (or two circles, side by side) with an oblique cross. Vegetative forms in the lower row, as a rule, depict pairs of connected S-shaped curls which are reminiscent of roots and shoots. Sometimes in the central crevice between the shoots, the artist would draw an oval speck, possibly representing a seed, from which the roots and shoots emerge in both directions. Leaves on the shoots are shown in the initial stage of growth, half-open.

(Left – shoots and roots, Right – water)

Knotwork is placed in the lower tier whenever the upper tier depicts people drinking from vessels, or dancing women. This allows us to see the knotwork as a decorative riff on the ancient ideogram for water, the wavy line. Incidentally, sometimes one of the three bands in the braid will be decorated with dots in the form of a simple wavy line. This dotted decoration is also sometimes seen on plant stems, as well as on the arches themselves. On the whole, the subjects depicted in the lower row seem to convey a single idea: plant shoots need to be watered.

Of particular interest is the presence of oblique crosses (which the Poles call “pagan roofs”[44]jeb: ?? “poganskie kryzhi” — this refers to the “X” shaped symbols.) on both the upper and lower tiers on bracelets. Clearly standing out from the woven ribbons, these crosses inside circles are in no way in keeping with the artistic logic of the design. Quite the opposite, they emphatically stick out from the initial plan, breaking the rhythm of knotwork and vegetative design. Most likely, these oblique crosses inside circles need to be viewed in relation to the calendar symbols for the month of June on the calendar-urn from a village in Lepesovko (Illustration 7). A complete analogy is found on a bracelet from a trove found in 1903 in the Mikhajlovskij monastery in Kiev. On the upper row, it depicts a lion flanked on either side by two oblique crosses inside circles; in the lower row, as on the Lepesovko drinking vessel, the symbol for water, a wavy line, appears beneath two oblique crosses. As a whole this appears to point to the month of June, the Rusalia month, and specifically to the Kupala Rusalia, which occurred during the time of the summer solstice.

On one of the bracelets found in Kiev, the same symbol for the Kupala holiday is seen inside a double rectangle in the lower row: two oblique crosses (without a circle) next to water-knotwork. In the upper row, there is a tree of life flanked by two rusalki-water spirits in the form of sirens.

The Rusalia/Kupala symbolism is indirectly tied to the form of vegetative design from the upper row: there, we often see depicted a stylized fern in the form of a heart-shaped figure with the point facing upward. The role of the fern in the Kupala rites is also well known.[45]jeb: It was believed that Kupala Night was the only time when a fern would flower. Anyone finding a fern flower would be blessed with wealth, power and luck.

A second recognizable plant, in my opinion, is hops. Its pairwise connected roots (exactly how hops are propagated by cuttings) are depicted inside boxes in the lower row. The arches in the upper row depict lateral shoots and bines at the time of flowering (in June, around the time of the Kupala holiday), while the “tree of life” seen in some archways seems to show ripe bines of hops, with the cones pulling the vines downwards toward the ground. On the calendar, this phase of hops’ growth occurs in the end of June or early July.[46]Nechiporuk, I.D. “Agrobiologicheskie osnovy vozdelivanija khmelja. L’vov, 1955, pp. 46-50. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank him for his kind consultation and for pointing me to the works of A.V. Kir’janova.

The presence and variety of images of hops in various phases of growth should not surprise us, as even in folk songs about Rusalia, hops are granted a special role:

"As on the Volga Jar-Khmel'

Curls beneath the bush...

I pinch the hops, the ardent hops,

And I'll brew the beer, the young beer.

(Semik song)[47]Snegirev, op. cit., vol. III, pp. 123-124.

Judging by the rites for weddings, New Year celebrations, and Rusalia, hops played the same important role in Russian life as grapevines played for peoples who lived further south. For the Indo-Iranians, the sacred plant was called khoma or soma, which appears to also indicate hops (medieval Russian k’mel’, Latin humulus). A general review of all the secondary elements depicted on bracelets intended for merrymaking gives us a clear set of symbols: the idea of fertility is expressed by plants and roots, irrigated with water during the critical period for growth, the summer solstice, and to provide all growing things with heavenly moisture, that is, rainfall. The plant world, thirsty for moisture, is expressed using ferns and hops, a sacred plant without which they could not celebrate any holidays with beer or hopped mead. The lower row of the bracelets, passing below the humans’, animals’ and birds’ feet, is interwoven with roots and fertile ideograms of water and the power of growth, graphically embodying the idea captured in the phrase “The Damp Mother Earth.”[48]jeb: Mat’-syra-zemlja, possibly the oldest Slavic pagan goddess. Later, this goddess merged into the god Mokosh, whose name literally means “damp”.

Of particular interest are the compositions on eight bracelets which include images of people or beings with human faces.

(1) A bracelet from Kiev (Rakovskij estate, found in 1889, Illustration 8).[49]Karger, M.K. Drevnij Kiev. Vol. I. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958, plate LXI.. The composition is in two rows. On the left side, in the central arch is a stylized fern-shaped Tree of Life; the two neighboring arches have sirens, with their heads turned toward the tree. On the other side, two sirens stand facing one another, and ripe hops are depicted in the final archway. The heads of the sirens are of young girls, bareheaded, without halos. Near each of the bird-girls is a shoot of curly plant growth. The lower row of each side is divided into two panels. The left side shows roots with tightly entwined buds and shoots. On the right, the already-mentioned dual oblique crosses, presented very clearly, with a water-knotwork. If the water and oblique crosses are, as written above, a symbol of the Kupala solstice Rusalia, then the figures in the upper row, as it turns out, would also be associated with Rusalia, as it is known that birds with girls’ faces were equated in medieval Rus’ with rusalki: “sirens, river spirits,” and the relationship of winged river spirits with rusalki was already seen above (“rusalki were beautiful girls with long hair and wings”). Birds (“the unlucky hen”) were sacrificed to these water spirits in medieval Rus’, it would appear, due to the spirits’ half-bird nature.

The fact that the image of the siren is widespread in medieval art of the Old World can in no way detract from the ancient symbolism of the bird-maidens and their connection to the sky, water, and vegetation. Roots of this type are seen on items even from the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.[50]Urns with bird-maidens and vertical streaked lines of rain. Kalicz, Nandor. Die Peceler (Badener) Kultur. Budapest, 1963, plates I-III.

The entire arrangement depicted on this bracelet is quite finely drawn, and all of its parts, from the fern to the dual oblique crosses, are firmly associated with the holidays of Rusalia and Ivan Kupala.

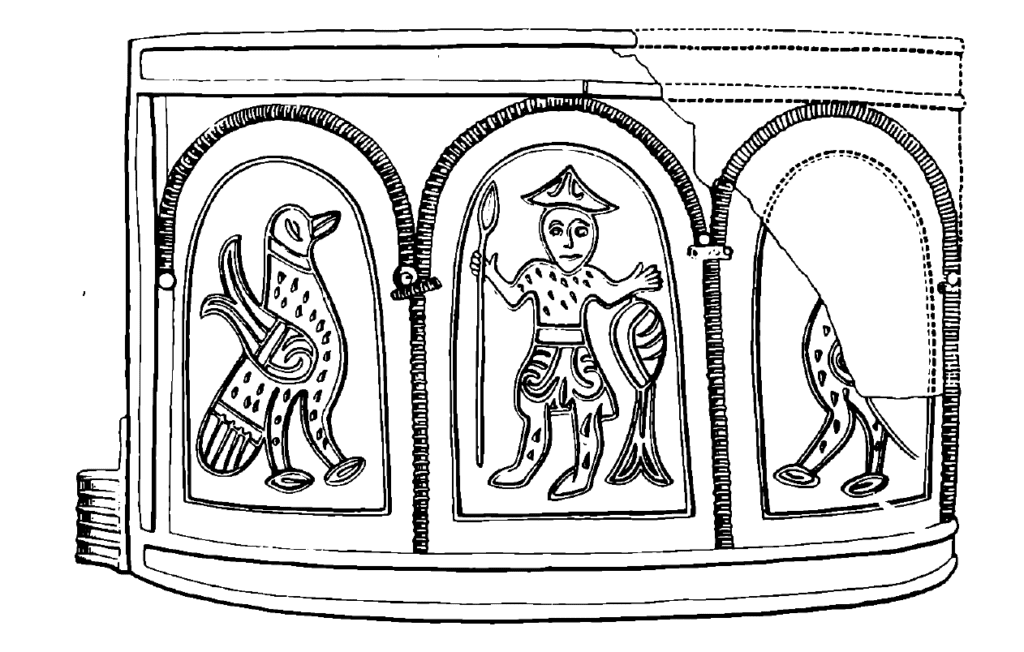

(2) A mold for casting a two-part bracelet (Kiev, Illustration 9), belonging to a type of Kievan bracelet, where the entire surface of each side is taken up by a single composition. On one side, there are two bird-maidens, with a bird and cross entwined between them. Their heads are masculine, wearing kolpak-style caps. The other side (which is broken), is nearly the exactly same image with the circle in the middle, but the birds here do not have human heads; instead, they have canine heads, making them typical Simargls. The Simargl-Senmurv as savior of the seeds and roots of the sacred tree is completely appropriate for jewelry intended for dancing. In medieval Iranian art, which can help us decode the Russian Simargl, Senmurvs are frequently depicted alongside priestesses dancing in outfits with long sleeves, just like the Russian girls at holidays (cf. the Radziwiłł Chronicle miniature “Merrymaking”). We will return to the male “sirens” later in this article.

(3, 4) Two identical paired bracelets of unknown provenance (collection of the State Historical Museum, illustration 10). They differ in the absence of niello and gilding over the design elements. The composition is two-tiered. On the left side, the lower row shows paired shoots (hops cuttings?); above them inside four archways there are two birds holding some kind of leaf in their mouths, and two hares. Near the hares’ muzzles we see two chalices with bottoms, tilted as if the hares were drinking from them. In medieval Rus’ right up through the 17th century, hares were taboo and were not used as food. Hares were associated with a number of meanings: seeing one crossing a road was bad luck, as was remembering a hare while floating on water, as the water would raise a storm.[51]Afanas’ev, A.A. Poeticheskie vozzrenija slavjan na prirodu. Vol. III. Moscow, 1869, p. 255. The author notes that, as with storks, the Germanic tribes considered rabbits to be a soul-bearer, that is, associated with the idea of fertility and the beginning of new life. The Lithuanians had a “rabbit god” named Diveriks, who was the protector of forest vegetation. If a hare was to run out of a forest, then hunters would not enter the forest “and dare not break a twig.”[52]Pol’noe sobranie russkikh letopisej. Vol. II, p. 188.

The “rabbit god” on the upper row of our bracelet completely corresponds with the roots and shoots of the lower row. Until now, the symbolic meaning of the centaur holding a hare in its hands carved on the Western side of St. George’s Cathedral in Yuriev-Polskij has not been deciphered.[53]Vagner, G.K. Skul’ptura Vladimiro-Suzdal’skoj Rusi. pp. 111-113, plate XXVIII. It is possible, and should be considered, that centaurs, which are frequently considered to be gods of fertility, were placed in that zone of the cathedral’s sculptural decoration which symbolizes the vegetative and fertile powers of the Earth. The centaur relief is depicted next to a tree with blossoming leaves. A centaur or kitovras[54]jeb: A medieval Russian monster, a centaur with wings. was also engraved onto a famous bracelet from a Tver’ trove found in 1906 (see below), which moreover also depicted shoots and roots on the lower tier.

The cult role of the hare is also reflected in medieval Rus’ amulets found in burial mounds from the 11th-12th centuries, which were most likely part of a wedding outfit, strongly saturated with magical elements. Among the amulets we find miniature axes, combs, keys, spoons, and parts of cast depictions of teeth and predator’s jaws. There are also depictions of birds, bulls and horses(?). The most common form of amulet is cast figurine of a canine animal with shoots on its back near the shoulders, abutting a curved tail. If you take these additions to the canine image as stylized wings, then it may be that we should consider them to be a variation of the Simargl, a protection from evil (like the Simargl on urban kolts). The axes and dogs are usually enclosed in circular solar decoration. In Pskov (the Gdov burial mounds, 11th-12th century), in addition to dogs, clear and distinct images of hares have been found repeatedly, which can also be perceived as ties to the cult of fertility.

On the other side of the bracelet, in the lower row there is a knotwork; in the four arch ways above, there are a musician and dancers. In the right pair of arches, a maiden with loose hair to her shoulders in a shirt with sleeves gathered at the wrist by a cuff bracelet. There is embroidery on her right shoulder. She wears a yubka or paneva over her shirt. She sits upon a small folding stool, facing the musician. The musician sits upon a more solid stool with an arched back. Under his left arm is something resembling a bagpipe, but he is not playing. The left half of this side is dedicated to the same individuals: on the right is the musician with his bagpipes, while on the left is the maiden, dancing with her sleeves loosened, reaching down almost to the ground. On both bracelets, the artist emphasized the maiden’s breasts, long hair and bare feet.

The dancing is shown in the same classical pose of the participants of the merrymaking as is documented in miniatures and numerous Russian and Bulgarian ethnographic examples. In Bulgaria, the “St. John’s Day maiden” walks around the fields of the village, singing songs about the sun and the birth of the crops, and dances “while waving the long sleeves of her outfit, just like a bird waves its wings.” The procession would stop at each well, where this “bird-maiden” would repeat her dance.[55]Marinov, D. op. cit., p. 494. This maiden dancer filled the role of the water spirit, a winged rusalka, irrigating the fields with dew and rain. It is likely that the same idea is seen in the dancer on the bracelet, which is accompanied in the lower row by the ideogram for water.

(5) A fragment of a casting form from Serensk (from a dig by T.N. Nikol’skaja, 1965) (Illustration 11). The description should be read taking into account that the bracelet cast from this mold would have had a mirror image. This side of the cuff is made up from 4 arches, but the left side is missing. The second archway shows a seated female holding a goblet in her left hand. The third arch shows a dancing maiden, waving her long sleeves and deeply curved in the dance. Her breasts have been industriously emphasized by the artist. The right quarter of the cuff depicted, according to V.P. Darkevich’s guess (see his article in this same issue)[56]jeb: Darkevich, V.P., Mongajt, A.L. “Starorjazanskij klad 1966 goda.” Sovietskaja arkheologija. 1967 (2), pp. 211-223, a musician holding a goat or a goat skin, that is, a set of bagpipes decorated with a goat’s head.

(6) A bracelet from Kiev, one-tiered, with the band broken up into three arches (Illustration 12). The leftmost arch shows a dancing maiden in an embroidered shirt, wearing either a paneva or jubka. Her sleeves are long and streaky. Her right hand (as on all other images of dancers on bracelets) is pointed downwards, while her left waves in the air. The third segment shows a gusli-player with a long kolpak cap and a long, embroidered outfit. His face is turned toward the maiden. The right-most arch shows a man, either jumping or dancing, wearing a short outfit. He has a sword in his right hand and an almond-shaped shield in his left. His face is turned toward the gusli-player.

The archway between the dancer and the gusli-player and in the arch next to the dancing warrior depict Simargls – birds with clearly canine heads and tails in the form of vines. The Simargls are presented in a spread-out, heraldic pose.[57]Petrov, V.P., Markevich, M.L. “Ob isobrazhenii na drevnerusskom braslete.” Kratkie soobschenija instituta arkheologii. 1962 (12). In the fourth arch from the left, behind the gusli-player, a bird buries its head under its wing. All of the human figures are surrounded by vines.

(7) A massive bracelet from Staraja Rjazan’ (dig by A.L. Mongajt, 1966). An article in this issue is dedicated to this particular item, so we will avoid a detailed description here. [58]jeb: Darkevich, V.P., Mongajt, A.L. “Starorjazanskij klad 1966 goda.” Sovietskaja arkheologija. 1967 (2), pp. 211-223. See Illustration JEB1 at the end of this post. It checks out very well against the general system of Rusalia decoration: the dancing maiden with long, streaked sleeves (as on Illust. 3 and 5), left hand pointing toward the ground, right hand drinking from a cup, quite similar to the one the hare drinks from in Illustration 10. At her feet lies another accessory of the merrymaking – a mask. A musician in a kolpak sits on some kind of a sprouted tree stump and drinks from the same kind of cup. In his hand, he holds a stick (possibly some kind of rod or club?). Beneath the drinking figures, there is knotwork symbolizing water. In the center is a gusli-player, surrounded by vines.

On the other half of the cuff there is a griffon and two bird-like male figures in kolpaks, beneath whom there appears vegetative designs. We will return to these figures, who are reminiscent of Kiev. In addition to lions and griffons, there are two exquisite depictions of Simargls, rising out of plant roots.

(8) A bracelet from the south-western edge of Kievan Rus’ (the village of Demidovo, near the city of Nikolaevo) (Illustration 13). On the left side there are 3 arches, showing the tree of life surrounded by two birds. On the right side, between two birds, there is a male figure in a short outfit and a conical hat. In his right hand, he holds a spear or staff, while his left is stretched out over an unopened plant. The figure is reminiscent of a Bulgarian rusalets with his staff and kolpak.

(9) A key to the content of all of the images seen on these bracelets is found on a bracelet from a Tver’ hoard found in 1906 (Illustration 14). Each side of the cuff is precisely divided into three arches which reach down into the bottom layer, by which the top and bottom layers for each archway are strongly correlated.

In the upper parts of the arches on the left side, we see the following: in the center, a dancing male in an embroidered shirt which is tucked into his pants. His wide stance and the sharp movement of his hands suggest that he is dancing, perhaps similar to the boisterous dancing and “wriggling about” of the Bulgarian rusaltsy. This rusalets dances amongst several branches of growth which surround him on three sides. Below, in the corresponding cell in the lower row, there is a doubled plant with a seed and roots. On either side of the dancer there are two female figures. The one on the right sits on a sprouted stump (as on the bracelet from Staraja Rjazan’), facing the dancer and raising a triangular goblet high with her right hand. In front of the woman, there is a doubled vine of some kind of climbing plant. The woman on the left is standing, holding her goblet in her left hand. Her right hand holds a bent Simargl by the wing. The Simargl grows out of the ground like a plant stem, and at waist-level bends again toward the earth. Its wings, forepaws and canine face (turned toward the ground) are clearly depicted. In the lower row, as on the bracelet from Staraja Rjazan’, we see knotwork, corresponding to the people drinking from vessels.

The right panel is made up from an image of the tree of life in the form of hops, weighed down with ripe buds, and a centaur-like being in the middle; in both cases, the lower tier depicts plant shoots. In the left arch is a beast with a flowering tail. The “centaur” has no horse-like traits: its front paws are soft, with claws instead of hooves, and its tail is more like that of a lion than of a horse. It’s human form does not allow us to decide whether it is male or female. Compositionally, it corresponds to the dancer, and beneath it is the same form of vegetation as under the dancer.

Everything depicted on these 9 bracelets and their forms completely correspond to our historical and ethnographical hypothesis on the summer Rusalia holidays.

A general trait on many of these bracelets is the presence of the arches which surround the people, animals, birds, and plants (Illustration 15). It’s not really possible to see them as an architectural arcade, as in the cases when the arches are not drawn schematically, but rather with details, they no longer look like an arcade. Their “columns” almost always widen notably toward the bottom, and are often covered in transverse lines that resemble birch bark. The arcs are also covered in marks, and the “capitals” look like rings going around the trunks. At the forks between the arches, we almost always see leaves depicted, and they are often framed by rows of separate branches. These details are reminiscent not of a princely palace with white stone arcades (where hares, ferns and birds would be relatively incongruous), but rather of the widespread custom of “curling” birch trees during Rusalia week on Whitsunday. This rite would take place in a grove near a sown field; there, they would link the tops of young birch trees together, weave birch branches into wreaths, and tear off birch branches. Under the “tent” created by these birches, people would feast and dance.[59]Snegirev, I. op. cit., vol. III, p. 102. These rites were still practiced in the Marinya Roscha district of Moscow as late as 1771.

Of course, Byzantine and Western jewelry depicting realistic arcades coudl have influenced Russian artisans, but the forest-like, birch-like character of the Russian “arches” on these bracelets is quite apparent and must have complemented the Rusalia subjects of these semi-ritualistic cuffs.

The final subject we need to analyze is an image that is associated with the Simargl, the protector of seeds, plants and shoots (Illustration 16). The ancient image of a winged, heavenly dog protecting the holy “tree of all seeds” is an image which, coming from the heavenly (wingless) dogs of the Trypilian culture, which has undergone a number of changes and contamination.

In the medieval art of Iran, Byzantium and Rus’, the same function as the protector of plants was filled by griffons, and possibly centaurs. In written sources, this mysterious image of the Simargl disappears from texts around the 11th century, while in the 12th-13th centuries we see the appearance of a new god of unknown function: Pereplut. The “Word of a Certain Lover of Christ” still mentions the Simargl, while in the “Word about how the Pagans Bowed to an Idol,” we no longer see the Simargl, but rather see Pereplut.[60]Anichkov, E.V. Jazychestvo i Drevnjaja Rus’. pp. 47, 75.

M. Sokolov has presented an interesting theory that Pereplut is the god of vegetative power, Jarilo.[61]Sokolov, M. Starorusskie solnechnye bogi it bogini. Simbirsk, 1887, p. 38.

G.A. Il’inskij thinks that Pereplut should be etymologically interpreted as the “god of abundance and wealth,” and matched to the medieval Russian deity of Pilvitus, which was also a god abundance, and in whose honor “a cup of beer and a prayer were raised, so that the god would send the land a good harvest.”[62]Il’inskij, G.A. “Odno neizvestnoe drevneslavjanskoe bozhestvo.” Izvestija Akademii nauk SSSR. 1927, p. 372. A.V. Solov’ev has proposed that Pereplut should be seen as a fertility god (from the word for entanglement or complexus), which completely agrees with both of the aforementioned opinions.[63]A.V. Solov’ev’s theory was mentioned by him while we were discussing my theory of “Pagan Symbolism of 12th Century Russian Jewelry” at the 1st International Congress on Slavic Archaeology in Warsaw in 1965.

Returning to our “silver folklore,” the 12th century Rusalia bracelets, we see that the classical image of the two-legged winged dog, the Senmurv/Simargl, is quite variable in shape. On bracelets there is a Simargl/crop protector as seen in Iranian mythology; on Kievan and Vladimir bracelets we also see birds with clearly canine faces near plants (Illustration 16, top right). This kind of Simargl was also seen on a Kievan casting mold, and two Simargls are seen on a bracelet from Terikhovo, placed in the lower row, as if under the woven birch branches in the upper row.[64]Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla Drevnej Rusi. Leningrad, 1936, Plate X.[65]jeb: See Illustration JEB2 at the end of this post.

Of great interest is the composition on a second bracelet from the Tversk trove found in 1906:[66]jeb: See illustration 16, middle right. a tree of life (?) is depicted in the form of a vertical braid; two birds sit on the branches above, and near the roots, as if interwoven into them, are two dog-headed creatures, which should, it appears, also be interpreted as Simargls. Or should we perhaps already start to call them by their later name, Pereplut, intertwined with the roots from the tree of life?

A Simargl/Pereplut, whose tail and wings transform into vegetative knotwork, is depicted on a Kievan bracelet from the Mikhajlovskij Monastery hoard, found in 1903 (Illustration 16). Next to it is a symbol of the sun. On another Kievan bracelet (number 1 described above, see Illustration 8), the lower, or so to say, underground layer under winged vilas and ferns, roots are depicted, curved so oddly that they imitate the semblance of some creature. These roots should be compared to the exquisite Simargl on a second bracelet from Staraja Rjazan: the tail of this winged dog transforms in its lowest parts into the same kind of roots.

Also of interest are the two beings depicted on the Kievan casting mold described above (Illustration 9). While on one side we see the typical Simargls, on the second there are “male sirens”, birds with male (rather than female) heads in kolpaks. Is this not the beginning of the anthropomorphization of the Simargl/Pereplut?

The clearest in this series are two of the same kind of beasts on an exquisite Staraja Rjazan’ bracelet with dancers and gusli-players. The male heads in kolpaks, the wedding symbol at the gate (rising toward a triangular ideogram of a sown field), the wings with wavy lines of water, the two canine paws, and the tail transforming into shoots and roots (Illustration 17). It is possible that one of the offshoots from his root/tail represents the phallus of this Pereplut, which would completely align with the understanding of him as Jarilo. The lower tier depicts roots and shoots.

The cult of Pereplut is strongly evidenced by Russian medieval sources. In the “Word about how the Pagans Bowed to an Idol,” which has roots back to the 11th century, but which has a passage of interest to us which was inserted in the 12th-13th century, it mentions that the Slavs made offerings to the following gods: “to vilas (rusalki), and Mokosh, Deva, Perun’, Khors, to Rod and Rozhanitsa, to vampires and bereginy (riverbank spirits), and they dance about and drink to Pereplut from horns.”[67]jeb: Mokosh was the mother goddess. Deva was the goddess of hunts and the forest. Perun’ was the god of war and thunder. Khors means “radiant” and was associated with the names of the gods for the sun and the moon (Dazhbog, Jutrobog). Rod and Rozhanitsa were the paired “male and female” supreme divinity. Another sermon (“A Word on How the First Pagans Believed in Idols”) repeats these words about Pereplut, and mentions that in his honor, the pagans would dance and drink from horns: “And the folk believe in Stribog and Dazhbog and Pereplut, and dance about and drink to them from horns, having forgotten the God who made heaven and earth and the seas and rivers and springs” (Illustration 18).[68]Gal’kovskij, N. op. cit., pp. 23, 60. In the ethnographic record, we saw how the Bulgarian rusal’tsy danced in frenzied “wriggling” during Rusalia week while engaging in ritual drinking from chalices.

The magic of fertility was the most ineradicable form of ritual, and it is not surprising that the clergy were so opposed to dancing in general, and to the dancing in honor of Pereplut in particular: “a curse upon all this merrymaking and all forms of dancing, which leads man away from God and leads him to the depths of Hell!”[69]idem., p. 189, ex. 11.

Pergrubij, a Lithuanian god of vegetation and the powers of fertility, seems to have been very similar to the Russian god Pereplut. Offerings to Pergrubij, according to data collected by M. Strotkovskij (11th century), went thusly: a priest would hold a chalice filled with beer in his right hand, and would sing to him: “O, our omnipotent god Pergrubij! You drive away the harsh winter and propagate the plants, flowers and herbs. We ask of you, multiply the grain we have sown and which we will yet sow, so that it may grow up tall and spiky….”[70]Famintsyn, A.S. Bozhestva drevnikh slavjan. St. Petersburg, 1884, pp. 115-116. The priest with the chalice, the round dances, and the dancing in honor of the god of fertility and growth – these are all well established in both medieval Russian sermons, as well as in the engravings of the Rusalia bracelets, against whose owners these teachings were directed.

We should turn our attention to the composition associated with these rites on the silver bracelets from the 12th century, in particular the one on the left side of the Tver’ bracelet: the dancing rusal’ets in the middle, surrounded by maidens drinking from conical cups or horns. One of the women (specifically, the one whom the rusal’ets is looking at) raises her horn, while touching the wing of the Simargl which grows up from the ground. This interesting scene can hardly be described as anything other than as an offering to Simargl-Pereplut. Here we have the rusal’ets in pied clothing, twisting in his dance, sprouting hops, women drinking from horns or cups, and the hero of the celebration himself, the god of vegetative power, the winged dog Simargl, protector of roots, receiving life-giving moisture from the rusalki.

Courtly ladies in Rus’s princely households, contemporary with the Lay of Igor’s Tale, would wear these semi-forbidden bracelets with pagan symbols and scenes during Rusalia, and carefully hid them in treasure troves during times of danger. Historians should not be surprised to find the presence of pagan subjects in the Lay of Igor’s Tale – its author was a man of his time.

Addendum

[jeb: The article references a few images from other sources, which I have added below.]

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Anichkov, E.A. Jazychestvo i Drevnjaja Rus’. St. Petersburg, 1914, p. 135. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | jeb: Primordial god of the universe and creator of all the other gods. |

| ↟3 | jeb: In Slavic folklore, the rusalka (plural: rusalki; Cyrillic: русалка) is a female entity, often malicious toward mankind and frequently associated with water. |

| ↟4 | V.A. Gorodtsov. “Dako-sarmatskie elementy v russkom narodnom tvorchestve.” Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja. 1926 (1). An interesting continuation of Gorodtsov’s works are a series of articles by A.K. Ambroz, who studied the consistent symbol of fertility in the shape of a diamond/rhombus. Ambroz, A.K. “Rannezemledel’cheskij kul’tovyj simvol (‘romb s krjuchkami’).” Sovetskaja arkheologija. 1965 (3); –. “O simvolike russkoj krest’janskoj vyshivki arkhaicheskogo tipa.” Sovietskaja arkheologija. 1966 (1). |

| ↟5 | jeb: “Moist”, a great Earth goddess, related to the Indo-Iranian goddess Anahita. |

| ↟6 | Trever, K.V. “Sobaka-ptitsa: Senmurv i Paskudzh.” Iz istorii dokapitalisticheskikh formatsij. Moscow-Leningrad, 1933, pp. 324-325. |

| ↟7 | idem., p. 325. |

| ↟8 | Guschin, A.S. Pamjatniki khudozhestvennogo remesla drevnej Rusi. Leningrad, 1936; Korzukhina, G.F. Russkie klady IX-XIII vv. Moscow-Leningrad, 1954. |

| ↟9 | Rybakov, B.A. “Prikladnoe iskusstvo i skul’ptura.” Istorija kul’tury drevnej Rusi. История культуры древней Руси. 1951 (2), pp. 396-464; –. “Iskusstvo drevnikh slavjan.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. 1953 (1), pp. 39-94.; –. “Prikladnoe iskusstvo Kievskoj Rusi IX-XI vekov i juzhnorusskikh knjazhestv XI-XIII vekov.” Istorija russkogo iskusstva. 1953 (1), pp. 233-297. Almost nothing new is added by this article: Bogusevicha, V.A. “Zobrazhenija Simargla v drevn’orus’komu mistetstvi.” Arkheologija. 1961 (XII). Here, the relief from a 12th century Chernigov capital (Illustration 4) is interpreted as a depiction of a Simargl, as are several well-known images of dragons (Illustrations 5-8), none of which can be accepted: Vagner, G.K. Skul’ptura Vladimiro-Suzdal’skoj Rusi. Moscow, 1964, pp. 120-123. |

| ↟10 | Rybakov, B.A. “Kalendar’ IV v. iz zemli poljan.” Sovetskaja arkheologija. 1962 (4), pp. 66-89; –. “Slavjanskij vesennij prazdnik.” Novoe v sovetskoj arkheologii. Moscow, 1963, pp. 254-257; –. “Jazycheskaja simvolika russkikh ukrashenij XII v.” Tezisy dokladov sovetskoj delegatsii na I Mezhdunarodnom kongresse slavjanskoj arkheologii v Varshave. Moscow, 1965, pp. 64-73; –. “O chem povedala litejnaja forma.” Nauka i zhizn’. 1966 (1), pp. 29-30; –. “Khristiane ili jazychniki?” Nauka i religija. 1966 (2), pp. 46-49; –. Jazychestvo i khristianstvo v Drevnej Rusi. Tezisy dokladov na sessii Otdelenija istorii AH SSSR v 1956 g. |

| ↟11 | jeb: Byzantium was known for its cloth of gold brocades. |

| ↟12 | jeb: Gods of waters and of the riverbank, protectors of the Earth. |