I was starting to work on a quiver for my crossbow bolts, and found this book while trying to locate information on what I discovered was a rather esoteric topic of medieval Russian quivers. Although a number of Rus’ manuscripts show archers and crossbowmen, I was having difficulty finding any that included a picture of their quiver. But, I was lucky enough to come upon a book by A.F. Medvedev that was completely devoted to archery in Rus’ in the 13th-14th centuries, based on archeological finds and other data. One of the chapters, which I’ve translated below, was devoted to quivers and bow-cases, which provided a lot of source material as well as links to other articles that I could use for my project!

Quivers in Medieval Rus’

A translation of Медведев, А.Ф. «Колчан и Налучье.» Ручное метательное оружие (лук и стрелы, самострел): VIII-XIV вв. Москва, 1966, с. 19-25. / Medvedev, A.F. “Kolchan i Naluch’e.” Ruchnoe metatel’noe oruzhie (luk i strely, samostrel): VIII-XIV vv. Moscow, 1966, pp. 19-25.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Master Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The book in the original Russian can be found here:

https://www.academia.edu/30139333.]

The quiver [Rus. колчан, kolchan, or тул, tul] was a case for storing and carrying arrows. Its use amongst the tribes of Eastern Europe can be traced back to the 11th century BCE.[1]Sinitsyn, I.V. “Arkheologicheskie issledovanija Zavolzhskogo otrjada (1951-1953 gg.)” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR (MIA), 1959 (60), p. 168, illus. 59 and 60, item 6; Bobrinskij, A.A. “Otchet o raskopkakh v Chigirinskom u. Kievskoj g. v 1908 g.” Izvestija arkheologicheskoj komissii (IAK). 1910 (35), p. 61; –. “Otchet o raskopkakh u s. Tur’i.” Otchet Arkheologicheskoj komissii (OAK) za 1908. 1912, p. 161; Rykov, P. “Sulovskij kurgannyj mogil’nik.” Uchenye zapiski Saratovskogo universiteta. Vol. IV, iss. 3. 1925, p. 28; Stepanov, P. “Izdelija iz dereva v kurganakh Suslovskogo kurgannogo mogil’nika.” Uchenye zapiski Saratovskogo universiteta. Vol. IV, iss. 3. 1925, p. 76; Novokreschennykh, N.N. “Gljadenovskoe kostische.” Trudy Permskoj uchenoj arkhivnoj komissii. Vol. XI. 1914, p. 72, plate I, items 3 and 26; plate XIII, item 2. The most ancient quivers typically were cylindrical in shape and were made from birch bark, wood, or leather. Birch bark was rolled up into a cylinder and covered in leather. Sometimes quivers were made with a lid. Quivers of similar form were widely used in antiquity among the tribes of Siberia and Central Asia.[2]Gorodtsov, V.A. “Skal’nye risunki Turgajskoj oblasti.” Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja (Trudy GIM). Iss. 1, 1926, p. 53, illus. 25; Savenkov, I.T. “O drevnikh pamjatnikakh izobrazitel’nogo iskusstva na Enisee.” Trudy XIV arkheologicheskogo s’ezda. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1910, pp. 192, 207, plate 8, illus. II, item 13, illus. XVII, item 2; Rudenko, S. and Glukhov, A. “Mogil’nik Kudyrge na Altae.” Materialy po etnografii. Vol. III, iss. 2. Leningrad, 1927, p. 45, illus. 13; Kiselev, S.V. “Drevnjaja istorija Juzhnoj Sibiri.” MIA. 1949 (9), pp. 294, 299, plate 50, item 24; Evtjukhova, L.A. Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki enisejskikh kyrgyzov. Abakan, 1948, pp. 61-65, illus. 112-114; Orbeli, I.A. and Trever, K.V. Sasanidskij metall. Moscow-Leningrad, 1935, plates 9 and 14.[3]jeb: See Plate 1, items 8-9, for layouts of two types of Russian quiver.

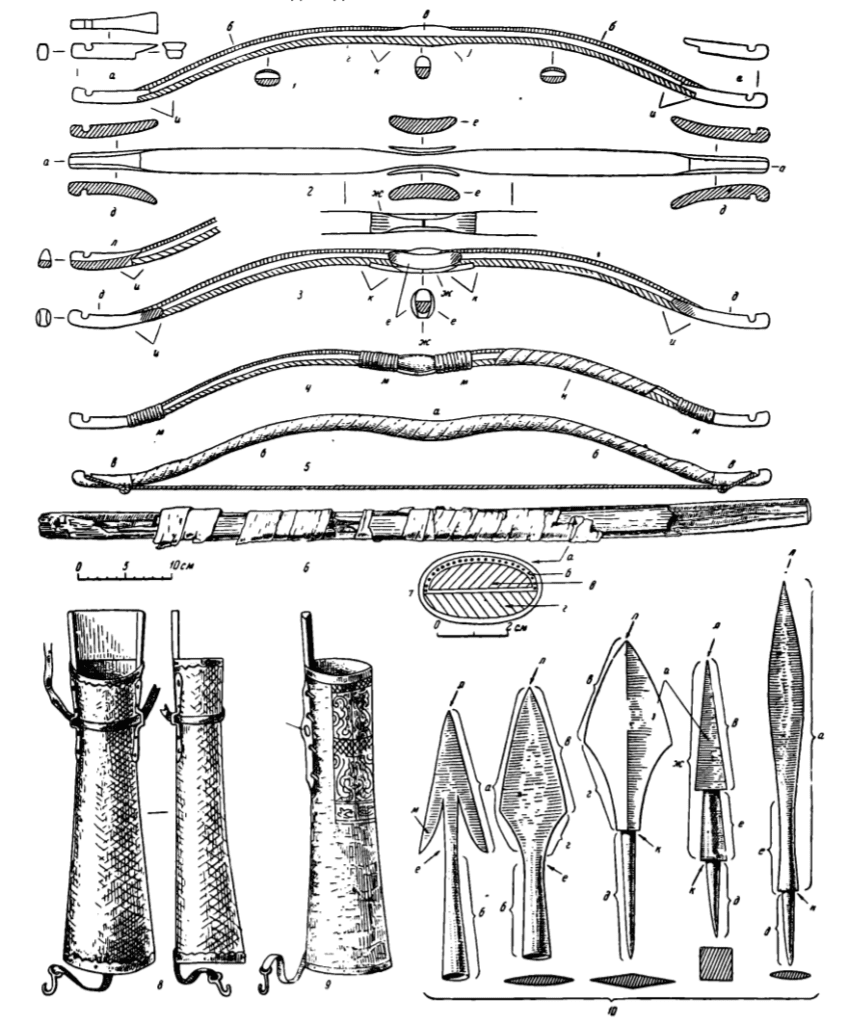

1 – the wooden foundation of a bow: а – ends with grooves for the string, б – tendons, в – birch wood, г – juniper wood, и – join of the ends, wood and tendons, к – join of the tendons and bone overlay for the bow grip

2 – a view of the wooden foundation of the bow from the inner side, and the layout for placing bone overlays: д – tip overlays with grooves for the string, в – side overlays for the grip, ж – lower overlays for the grip from the inner side of the bow;

3 – layout for placing overlays on the bow (side view): д – tip overlays, е – side overlays, ж – lower overlays, и – join at the ends of the bow, к – join at the bow grip;

4 – reinforcing the joins of the bow parts by winding on tendons with glue and wrapping the bow with birch bark: м – bundle (wound tendons), н – pasted-on birch bark;

5 – bow strung after being glued together;

6 – fragments of a composite bow, late 12th century, Novgorod;

7 – cross-section of (6): а – birch bark wrapping, б – tendons, в – birch wood, г – juniper wood;

8 – layout for iron brackets and finishings on 10th-century quivers;

9 – layout for bone hinge and decorative overlays on 8th-14th century quivers;

10 – Names of the parts of iron arrowheads: а – head [Rus. перо, pero, “feather”], б – socket [Rus. втулка, vtulka], в – blade [Rus. сторона, storona, “side”], г – stem [Rus. плечико, plechiko, “shoulder”], д – flange [Rus. черешок, chereshok, “petiole”], е – neck [Rus. шейка, shejka], ж – warhead (for armor-piercing heads) [Rus. боевая головка, boevaja golovka], и -facet [Rus. грань, gran’], к – flange [Rus. упор для древка, upor dlja drevka, shaft support], л – point/tip [Rus. острие, ostrie], м – barb [Rus. шип, ship]

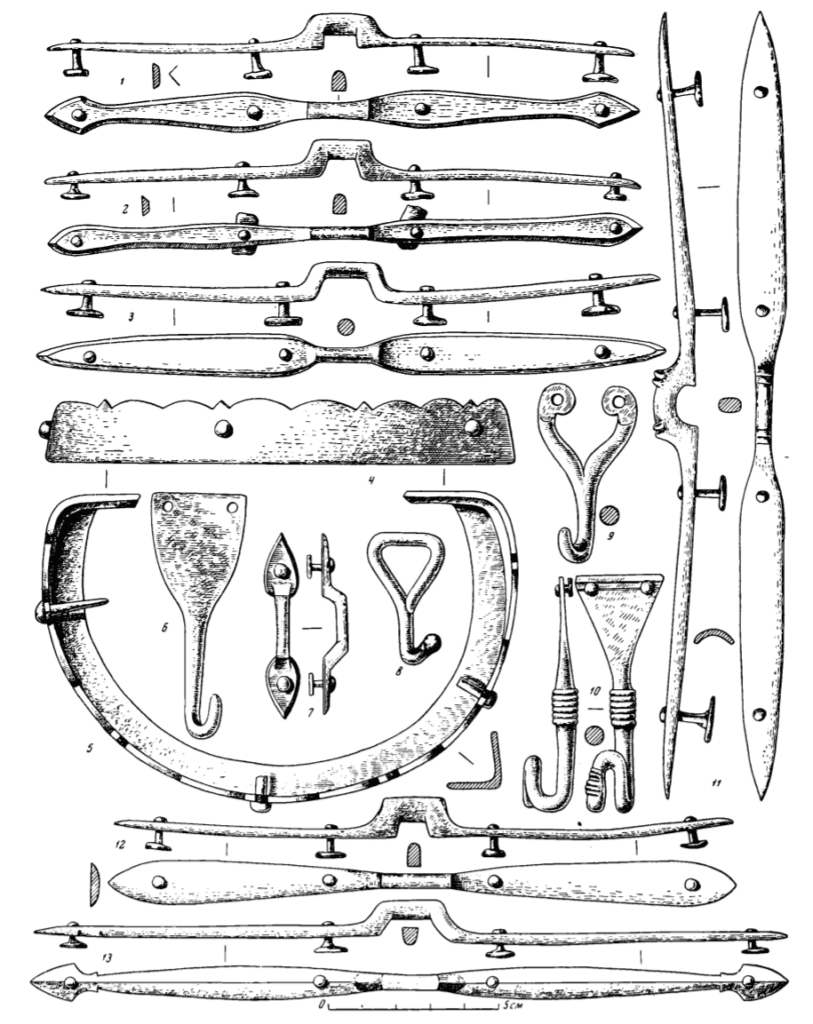

The Eastern Slavs used the same kind of quivers, carrying them at the waist. Wood and leather are poorly preserved in earth, and as a result, remnants of quivers are rarely found during excavations. Almost no intact quivers from the 8th-9th centuries have survived, but in the graves of archers, we find many iron remnants: loops, buckles, and hooks (Plate 7, items 7-10).

Leather quivers with hooks on straps attached to the bottom and iron loops in the form of brackets with two rivets (Plate 7, item 7) were found in burials 10, 33, 55, 75, 122, 143, 200, 212, 234, 235, 274, 277, and 313 in the Bol’she-Tarkhanskij burial ground.[4]Digs by V.F. Gening and A.Kh. Khalikov, 1957 and 1960, in the Archive of the Department of Archeology of the USSR Academy of Sciences (IA AN SSSR). Gening, V.F. and Khalikov, A.Kh. Rannye bulgari na Volge. Moscow, 1964, pp. 47-50, illus. 14, plate XIII, items 1-3, 5-6, 8-9. On their proposed reconstruction of the quiver, it appears that they correctly placed the brackets with two rivets (plate XIII, item 9) and the hooks at the bottom, but the brackets (plate XIII, items 5, 6) for the hooks and the bone plaques (plate XIII, item 18) could hardly have been attached to the body of the quiver. Undoubtedly these quivers were made of birch or bast, but they have not survived. Iron brackets with rivets were quite characteristic in the 8th and 9th centuries. In the 10th century, similar brackets with 4 rivets became widely used.

1 – loop from a 1st c. burial mound in Porech’e; 2, 3 – loops from burial mound 85 from Timerovskij burial ground; 4, 5 – bottom fitting for a quiver (4 – side view, 5 – top view) from burial mound 16 from the Berezki burial ground; 6 – a hook from burial 18, Nevolinskij burial ground; 7, 8 – a loop and hook from Bol’she-Tarkhanskij burial ground; 9 – hook from tomb 5 from the Dmitrievskij burial ground; 10 – hook from Gnezdovo burial ground; 11 – loop from burial mound 206 from Timerovskij burial ground; 12, 13 – loops from the Gnezdovo burial mound.

Many remnants of quivers from the 9th-14th centuries from the Russian and peoples of Eastern Europe have survived to modern day. They are found particularly frequently in the burial mounds of nomads from Southern Russia and Ukraine. These include iron brackets and fittings for the mouths and bottoms of leather quivers with wood or birch bark bodies, widely used in the late 9th-10th centuries by the Eastern Slavs and Magyars (Plate 7, items 1-5, 11-13), bone hinges and ornamental overlays from leather and birch quivers from the 9th-14th centuries, and finally almost complete quivers.

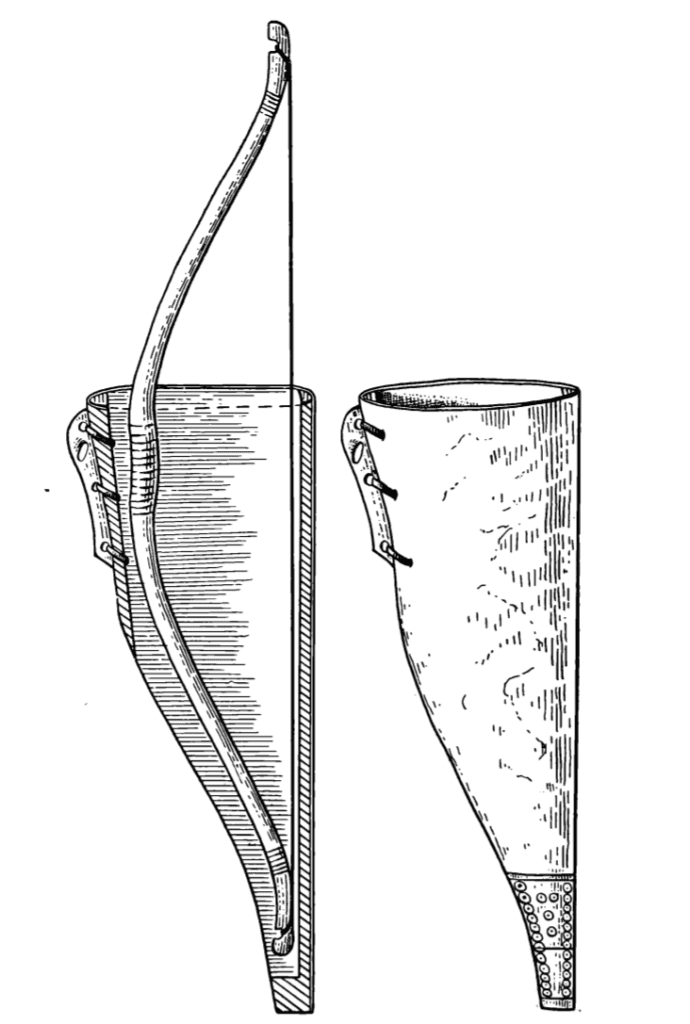

In the lands of Eastern Europe during the 8th-14th centuries, there were in use, it appears, two general types of quivers: cylindrical quivers made of birch with bone flaps for suspension,[5]jeb: See Plate 1, item 9. and leather semi-cylindrical quivers with iron finishings and brackets for suspension.[6]jeb: See Plate 1, item 8. Both types had a wood bottom and body or a plank to which the brackets were nailed or riveted. Quivers of the first type were accessible for any archer, and they were used throughout this entire period. Quivers of the second type were used from the late 9th to the early 11th century, especially among Russian professional soldiers [druzhinniki] and the Magyars.

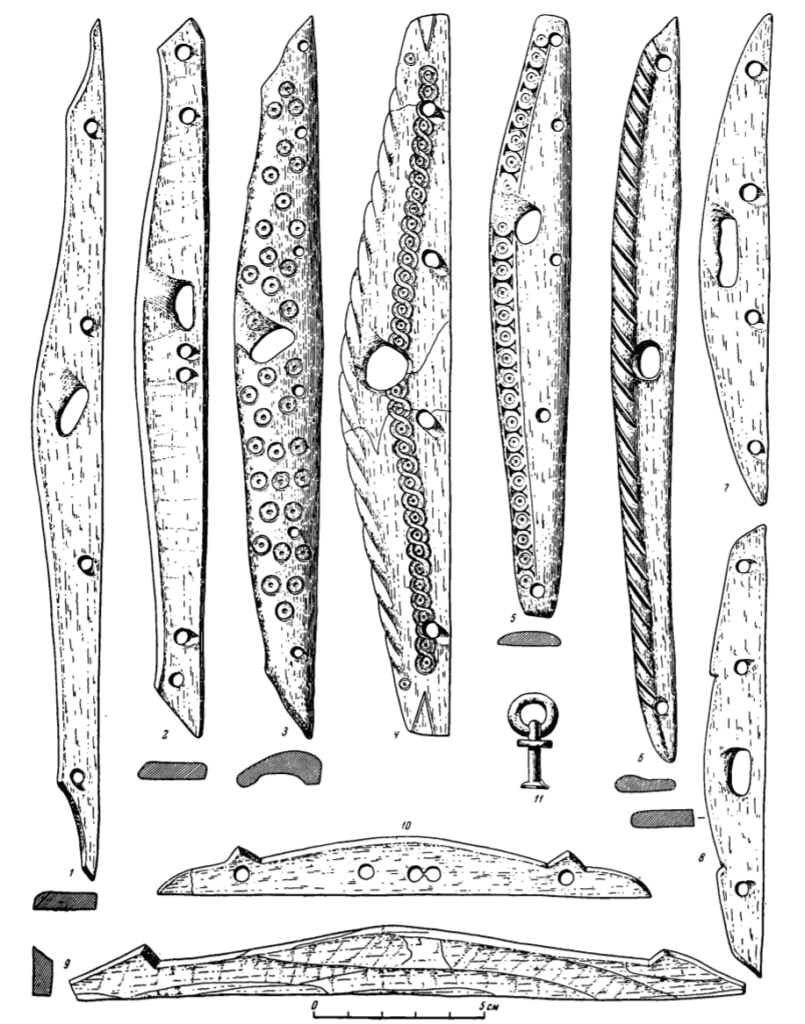

Cylindrical quivers with a widening at the bottom and at the throat were made of two layers of thick birch bark, and had a wooden bottom about 1 cm thick which was attached to the bark with iron nails with heads. The bottom was inserted upward prior to fastening. A strap with an iron hook on the end was sometimes attached to the wooden bottom, used to anchor the quiver when riding quickly on horseback. This hook on the bottom was a characteristic sign that the quiver belonged to a mounted archer. Inside the quiver (from the bottom to the throat), it appears they always inserted a wooden plank, to which a bone hinge would be attached with straps, or from which would be suspended an iron ring for suspending the quiver from the belt or over the shoulder on a shoulder strap. The bone hinges were attached using 2-3 parallel straps, which would also sometimes cover the quiver at the throat. They were sometimes covered on top with leather, but not always. Rarely, birch cylindrical quivers were decorated with plaques or thick lamellae of bone with carved ornamentation. They were glued, sewn or riveted to the upper part of the quiver, near the throat.

These quivers reached up to 60-70 cm in length, and rarely exceeded this limit. These were used to hold arrows that were 70-90 cm in length. The quivers’ diameter at the bottom did not exceed 12-15 cm, and at the center of the body, 8-10 cm. The arrows were carried fletches up, and the quiver widened at the bottom to accommodate the arrow heads. In order to prevent the plumage from getting crumpled, the quivers often also got wider at the throat. The arrow shafts were almost always decorated at the fletches in various colors, depending on the purpose of the arrow heads. This allowed the archer to correctly select an arrow for a given situation by the nock based on this color, and to immediately nock this arrow on the string. If the arrows were stored with the fletches down, then the archer would have to waste time turning the arrow around to nock it, and the damage to the fletches would be greater.

Quite a few remnants of cylindrical birch-bark quivers are preserved in Eastern Europe, as well as in Siberia. Even more of the bone hinges have survived.

1, 2 – hinges from Novgorod; 3, 8 – hinges from Bilyar; 4 – a hinge from the Donetskoe hill fort; 5 – a hinge from Sarkel, Belaja Vezha; 6 – a hinge from nomad burial mound #367 near Zelenki; 7 – a hinge from Smolensk; 9 – an unfinished hinge for a quiver from Sarkel, Belaja Vezha; 10 – an unfinished hinge for a quiver from Biljar or Bolgar; 11 – an iron rivet with a ring from a 14th century birch bark quiver from a nomad burial near Grushevki.

A birch-bark quiver, cylindrical in form with a widening at the bottom and, most likely, and the unpreserved throat was found in burial mound VIII near the Avilovskij farm. This quiver was around 60 cm in length, and its width in its flattened state at the throat was 12 cm, and at the bottom 18 cm. It is easy to determine the original diameter of the quiver: 12 cm at the bottom, and around 9 cm at the throat. It was worn on the left side at the hip, on either a belt or shoulder strap. I.V. Sinitsyn dated the grave to the 5th-8th century, but it most likely comes from the 8th century, judging by the iron arrowheads found there, which were typical for that time.[7]Sinitsyn, I.V. “Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki v nizov’jakh reki Ilovli.” Uchenye zapiski Saratovskogo universiteta. Vol. 39. 1954, pp. 228, 230, illus. 1 and 4 (center).

A similar birch-bark quiver from the 14th century, covered in leather, with bone hinges at the throat was found in grave 6, burial mound 9 at Berezhnovki.[8]Sinitsyn, I.V. “Drevnie pamjatniki v nizov’jakh Eruslana.” MIA. 1960 (78), pp. 117, 166-168, illus. 45, item 1. The hinges have 4 small holes for attaching to the quiver, and a large hole (loop) for the belt. It was possible to trace where these hinges were located on the quiver: it was attached using a thick cord at the throat to a vertical plank or to a leather strap. The edges of all of the holes had grooves worn into them by cord, caused by prolonged wearing of the quiver filled with arrows. The same grooves, although wider and in the opposite direction, were also seen on the hinges. This mark was caused by the suspension strap.[9]idem., p. 117, illus. 44, item 13.

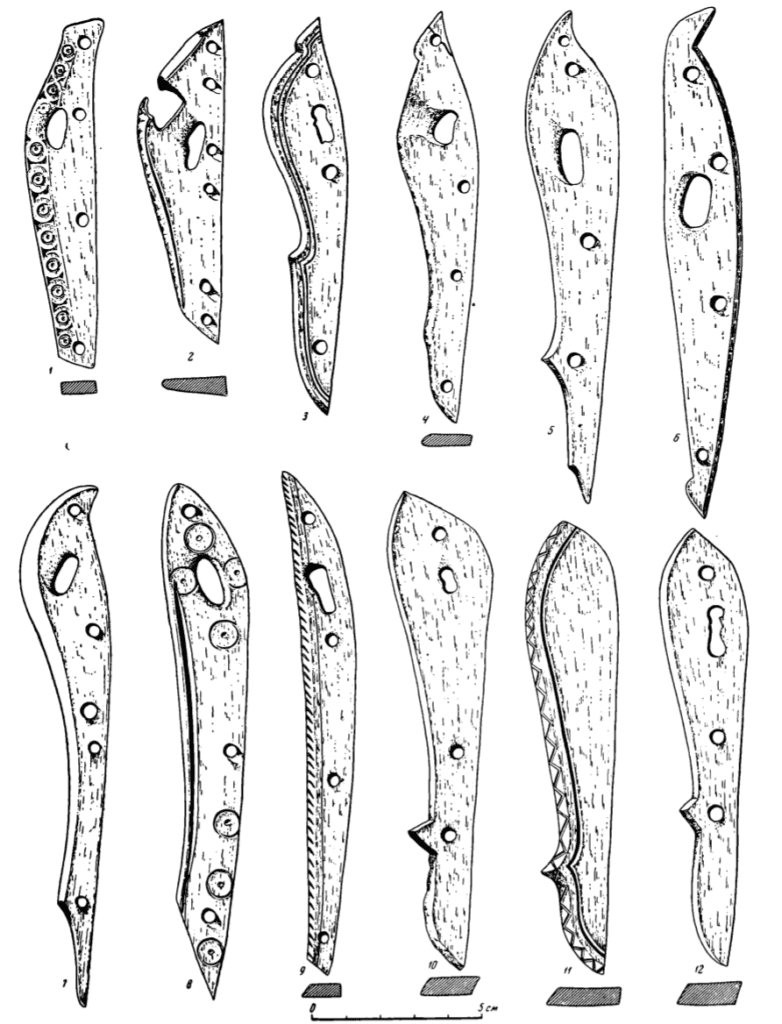

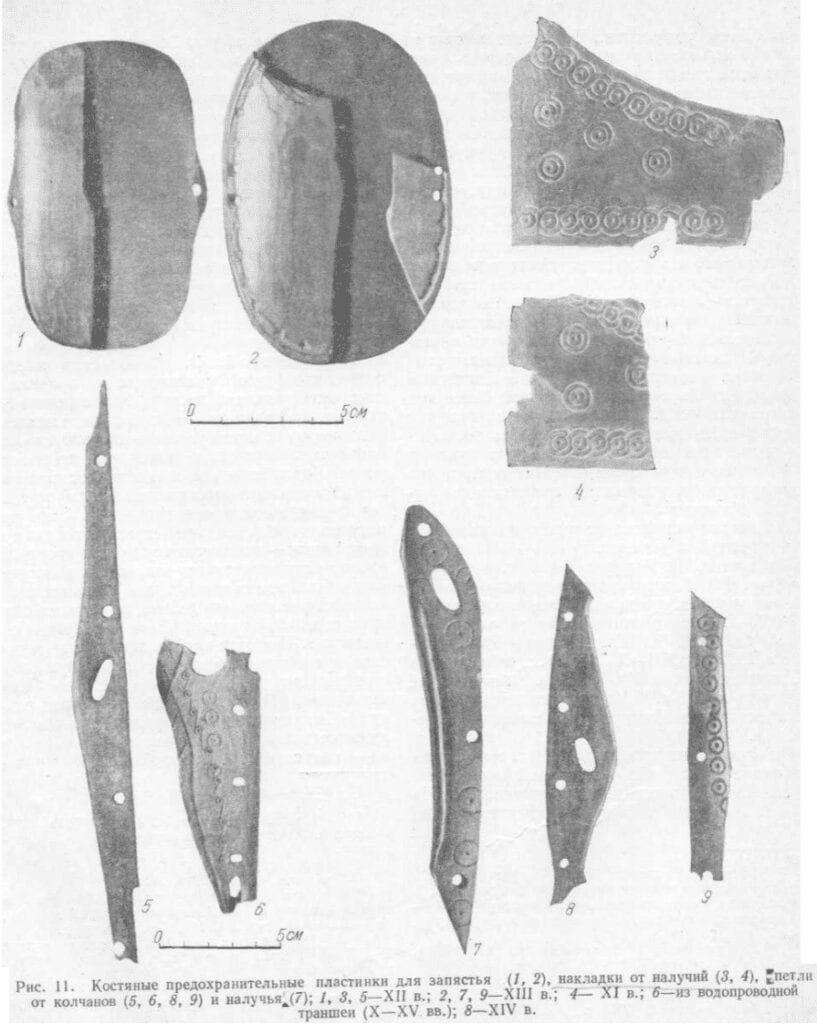

Bone hinges and plates were a constant accessory for birch-bark and bast quivers which were covered with leather. The outer side of the plate was often decorated with carving, while the inner, sometimes spongy side was undecorated. They also are not scratched with lines for gluing, because these plates were never glued or riveted on, but rather were attached using thin laces. They are varied in shape (Plate 9), but they had a single purpose – these hinges were used to hang the quiver from a belt or shoulder strap.

Sometimes, along with these and in the very same grave, we find hinges of a particular shape, with curved ends (Plate 8). These were, most likely, hinges not for a quiver, but for a bow case [Rus. налучье, naluch’e], a special leather case used to carry a bow and to protect it from the elements.

1 – from Sarkel, Belaja Vezha; 2 – from a burial mound near Solyanika Island; 3, 12 – unfinished hinges from Bilyar; 4 – from Bilyar or Bolgar; 5 – from Belozero; 6 – from a nomad burial mound near Stretovki; 7, 8 – from Novgorod; 9 – from a nomad burial mound near Krasnopolki; 10 – unfinished hinge from Bilyar or Bolgar; 11 – unfinished hinge from Kylasovo hill fort.

Half-round quivers had a wooden semi-circular bottom, and a wooden body (a flat wall made of thin wooden board), to which the iron brackets were attached and iron finishings were nailed (Plate 1, item 8). The body was most likely of thick leather, or birch bark covered with leather. Felt may also have been used, but no signs of this have been found in burial sites.

The majority of finds of this type of quiver has been from burial mounds with interments from the 10th century. There, neither leather, birch bark, nor felt has survived. Only the iron brackets, finishings and rivets have survived, and those frequently only in fragments.

In medieval Russian burial mounds from the 10th century (Gnezdovo, Shetovitsy, Timerevo, et.al.) iron findings from the bottom and throat and iron brackets with flattened ends (Plate 7) are found rarely, and their purpose was not guessed for a long time. In Hungary, similar pieces were found together with fragments of a quiver body covered with leather and fused arrowheads.[10]Hampel, J. Alterhümer des frühen Mittelalters in Ungarn. Vols. I-III. Braunschweig, 1905, p. 178, illus. 429. Based on these preserved elements, the form of this type of quiver can be reconstructed relatively easily (Plate 1, item 8).

This type of quiver was used throughout the territory from the Central Volga and Kama Rivers to Hungary. It is possible that in Hungary, they were used by the Magyars.

It is possible that in Rus’ and among the nomadic tribes, a third type of quiver was used, which was flat with a wooden body, covered in leather and decorated with thin sheets of carved bone. These quivers also had a widened bottom for arrowheads. The existence of these quivers can be judged based on several archer graves from the 12th-14th centuries, which contained long, thin decorated bone plates with rivets and rivet holes. These plates were up to 65 cm in length, corresponding to the length of a quiver, and were around 2 cm wide. Judging by the shape and size of these plates, they were attached to the narrow side (or sides) of the quiver, or by their edges to the front of the wooden body. It is possible that these quivers led to the later flat Russian quivers (16th-17th century), which were a bit shorter and baroque.

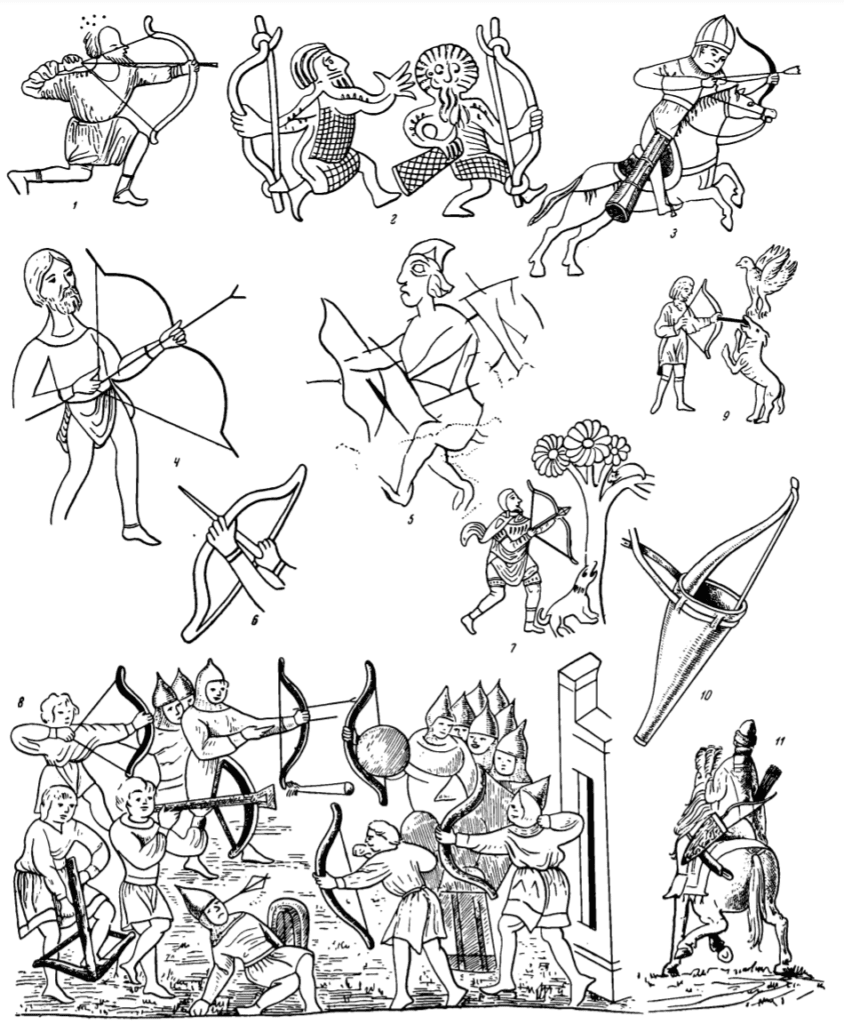

A multitude of images of medieval Russian quivers have been preserved on everyday and architectural items, in miniatures, and on icons. Based on these, we can determine their shapes and dimensions. The 10th century silver covering of an aurochs horn found in Chernaja Mogila depicts archers with composite bows and a quiver at one person’s right thigh (Illustration 1, item 2). Its shape is similar to that used by Siberian, Altai, and Central Asiatic tribes in the early Middle Ages.[11]Samokvasov, D.Ja. Mogilnye drevnosti severjanskoj Chernigovschiny. Moscow, 1917, p. 14, illus. 16; Rybakov, B.A. “Drevnosti Chernigova.” MIA. 1949 (11), p. 48, illus. 20.[12]jeb: See image JEB1 below, showing a photograph of this silver horn finding. These were round or semi-round in cross section, and widened at the bottom. This form, judging by the remnants of iron finishings in burial mounds and interments, was also in use in Rus in the 10th century.

The remains of a wooden body from a quiver with iron brackets and findings was found by M.K. Karger in the grave of a Rus’ 10th century soldier under the Cathedral of the Tithes in Kiev.[13]Karger, M.K. Pogrebenie kievskogo druzhinnika X veka.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury Akademii nauk SSSR (KSIIMK). 1940 (5), pp. 79-81, illus. 18; –, 1958, p. 184, illus. 32. This quiver contained roughly 20 arrows with different types of heads.

1 – footsoldier from a miniature in the Khlodovskij Psalter; 2 – archers on silver covering of an aurochs horn from Chernaja Mogila; 3 – a Russian archer on horseback, 10th century, from a miniature in the Manasene Chronicle; 4 – archer from the Svjatoslav Izbornik of 1073; 5 – depiction of an archer on a late 11th-early 12th century stone sinker from Novgorod; 6 – image of a bow from a stone carving in 12th century St. Dmitrij Cathedral in Vladimir; 7 – hunting with a bow, from the frescos in St. Sophia’s Cathedral in Kiev; 8 – archers and crossbowmen in a miniature from the Radziwiłł Chronicle; 9 – a hunter with a bow, carved on the shaft of a spear belonging to Tver’ prince Boris Aleksandrovich; 10 – a bow and bow case, from a drawing in Gerberstein’s 1556 book; 11 – a 17th century archer on horseback, from Meierberg’s album.

The capacity of medieval Russian quivers appears to have rarely exceeded 20 arrows. Exactly that many arrows were found from an unpreserved quiver from a 10th century burial from the Borka burial ground.[14]Dig by V.I. Zubkov, 1949, Rjazan’ Museum. Quivers from later times also appear to have been limited to around 20 arrows. This can be determined from diplomatic letters from the 15th-17th centuries.[15]Sbornik Russkogo istoricheskogo obschestva [Sb. RIO]. 1884 (41), p. 230; Akty istoricheskie. Vol. IV. St. Petersburg, 1842, p. 399

Quivers of the Tatars, Turkmen and Circassians could accommodate up to 30 arrows. In the Karras group of burial mounds near Pjatigorsk, bundles of rusted arrow heads are frequently found, based on which we can determine their quivers could accommodate 30 arrows. This number is not exceeded even once.[16]Samokvasov, D.Ja. Mogily Russkkoj zemli. Moscow,1908, p. 242+, burial mounds 12, 13, et. al. Quivers from the 14th century Belorechenskij burial mounds could hold the same quantity of arrows.[17]Digs by N.I. Veselovskij, 1906. State Historical Museum.

Marco Polo noted that among the Turkmen of Central Asia in the 13th century, it was customary for every soldier to carry 60 arrows into battle: 30 small arrows (darts), and 30 large arrows with wide iron heads.[18]Polo, Marko. Puteshestvie. Leningrad, 1940, p. 245. The latter could be used to cut the bowstrings of enemy archers, to fell enemy cavalry horses, etc. It appears that during war with the Mongols, Central Asian warriors would carry two quivers each (30 arrows apiece), as was also common among their enemy, the Mongols.[19]Karpini,Ioann de Plano. Istorija mongolov. St. Petersburg, 1911, pp. 27-28.

Russian epic poems [byliny] dating back to the earliest history of Rus’ and reflecting historical facts of war against the nomadic tribes frequently mention quivers, but do not provide any description of their construction. They typically speak mere of a “quiver of hot arrows.”[20]Danilov, Kirsha. Drevnie rossijskie stikhotvorenija, sobrannye Kirshoju Danilovym. Moscow, 1818, pp. 22-24, 61, 129, 204, 208, 217.

It seems that medieval Russian quivers may have had leather covers to protect the arrows’ fletching from rain and damage. These covers would normally have been kept closed, and only opened prior to battle, judging by the Lay of Igor’s Campaign, which says: “They strung their bows, and opened their quivers.”[21]Slovo o polku Igoreve. p. 8. But, these covers are not mentioned in any other documentation.

The medieval Russian chronicles also mention quivers, but they are not depicted in any miniatures, with the exception one of the saints’ lives, admittedly later period, but where we can see a quiver which widens at the bottom and appears to be cylindrical, quite similar to the one depicted on the 10th century aurochs horn from Chernaja Mogila.[22]Zhitie Antonija Sijskogo. 1648. Folio 235 obv. Storied in the Manuscript Department in the State Historical Museum. In medieval Rus’, as was noted by N. Aristov, quivers were made of leather.[23]Aristov, N. 1866, p. 151. The Ipatiev Chronicle from the mid 13th century mentions tul’niki, specialized artisans who made quivers to carry and protect arrows.[24]Letopis’ po Ipat’evskomy (Ipatskomu) spisku. St. Petersburg, 1871, under year 1259.

Based on remnants of quivers preserved together with arrows at the Rajkovets settlement, which was destroyed by the Mongols, we can judge the materials that went into their manufacture. The Rajkovets quiver had a wooden base, covered with leather. It’s form was not hard set. It contained a collection of various kinds of arrows: narrow armor-piercing ones, wide cutting ones, chisel- and diamond-shaped ones, all used for different purposes.[25]Goncharov, V.K. Rajkovetskoe gorodische. Kiev, 1950, pp. 42-43. The quiver from grave #105 in Kiev was made from bast and leather.[26]Karger, M.K. Drevnij Kiev. Vol. 1. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958, p. 167.

Quivers of these older forms existed in Rus’ among ordinary warriors until the late Middle Ages, while in the 14th-15th century nobles took up the custom of wearing saadaks, quivers which had a more artistic shape and which were luxuriously decorated.[27]jeb: See image JEB2 for a picture of a saadak-style quiver. On 15th century icons housed at the Tretyakovsky Gallery in Moscow, for example, icons of Demetrius of Thessaloniki and George, the quivers are depicted in that form which predominated in Rus in the 10th century – cylindrical or semi-cylindrical cases, up to 70cm long, widening at the mouth and bottom. Their arrows are stored with the fletches upward. Russian warriors always carried their quiver at the hip on a belt, or across the shoulder. Roughly the same shape of quiver with fletched arrows is seen on a private soldier from the 16th century on a German engraving in Gerberstein’s book. It is worn on the right hip, and his composite bow is in a case work on the left (Illus. 1, item 10).[28]Gerbershtejn, S. Zapiski o Moskovitskikh delakh. St. Petersburg, 1908, illus. between pp. 64-65. Gerberstein also depicts more wealthy cavalry warriors, also with quivers on their right hip.[29]idem., pp. 249, 258.

Interestingly, in the 16th century, the peoples of the Northern European sections of the USSR used four-sided quivers, which were worn on the back. Such quivers are shown by Gerriet de Vera amongst the Nenets tribe. These widened only at the top, for the fletches.[30]idem., p. 187. Back quivers were also worn by foot archers in North-Eastern Europe, as is seen on illustrations in Karion Istomin’s primer, but there the quivers are not four-sided, but rather round in cross-section (that is, cylindrical). The arrows in these are placed fletches upward.[31]“Bukvar’ Kariona Istomina 1694 g.” Trudy Moskovskogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XXV, letter Ju. The Nganasans and other Northern tribes carried their quivers on the back until the 20th century.[32]Popov, A.A. “Okhota i rybolovstvo u dolgan.” Sbornik statej pamjati V.G. Bogoraza. Moscow-Leningrad, 1948, p. 23.

A 15th century Arab treatise states that quivers may be made of leather, felt or wood, but that the best are made of leather. They should be wide at the throat, narrow in the middle, and widen again at the bottom, and should have a cover in order to protect the fletches from rain. They should be able to carry 25-30 arrows. The length of the quiver may be 70 cm or more, in order not to damage the fletches, especially for those who shoot long arrows from an oblique angle like the Persians, who used arrows 90 cm or more in length (12 hands), which were fletched right at the notch. It was recommended to cover the quiver with leather on both the inside and outside. These would hang on a strap across the left shoulder such that it sat on the right side at elbow level.

Some medieval archers, according to the author of this treatise, felt that a quiver should be 3 spans long (66-70 cm). But, the author himself disagreed, as arrows used in his time were usually 3-3.5 spans in length (66-80 cm), and placing such arrows in a quiver which was the same or nearly the same length would inevitably damage the fletches. As such, the length should just reach the fletches, and not cover them.

The treatise recommends making a bow cover up to 12 cm shorter than a strung bow, up to equal to the strung bow’s length, and to wear it on the left. An archer should carry with him (in a pocket on either the quiver or bow cover) scissors for cutting fletches, and a file for expanding wooden arrow shafts or sharpening arrowheads as needed.[33]Arab Archery: An Arabic manuscript of about A.D. 1500: A book on the excellence of the bow and arrow and the description thereof. Trans. by Nabih Amin Faris and Robert Potter Elmer. Princeton, 1945, pp. 154+ Arabian, Persian and other Eastern archers often carried knifes as well. It is known that Russian archers also carried saadak– and boot-knifes, which have been found in burials of archers from the 8th-14th centuries, along with files.

Based on a comparison of medieval Russian quivers with this Arabian description, it is clear that they were very similar in build, material, length and capacity, as well as in how they were worn on the right side. But, this addresses only the most common and widespread quivers from common soldiers, rather than those of the upper class, where among both the Russians and Arabs, quivers had a different structure and style, although they still had the same basic requirements.

Upper-class quivers are shown on Iranian miniatures from the 16th century. One can trace the perfect similarity in all details with medieval Russian archery equipment from the same period housed in the State Armory and other museums of the USSR. Their structure, form and decoration can be well understood from the Sheremetevo weapons collection. They are completely analogous to Persian quivers of the same time (see the miniatures in the Book of Kings [Shahnameh] manuscripts in museum collections).[34]Gjuzal’jani, L.T., D’jakonov, M.M. Iranskie miniatjury v rukopisjakh Shakh-Name leningradskikh sobranij. Leningrad, 1935, plate 1, items 17a, 21, 26, 39, 40, 42, 47, 48, 50; Lents, E. , 1895, pp. 98-99.[35]jeb: See images JEB3, JEB4. Primarily starting in the 15th century in Rus’, so-called saadaki or sagadaki came into use, consisting of a bow case and quiver.

The bow case [Rus. налучье, naluch’e] was a case for carrying a bow and protecting it from the elements. Bow cases were made in the shape of the medieval Russian composite bow. As a rule, they were flat, with a wooden body covered with leather or flat material. Such also are all bow cases from the 16th and 17th centuries stored in our museums. Bow cases are sometimes portrayed with an opening in the shape of an extended oval, such as on an engraving in Gerberstein’s book (Illustration 1, item 10). The rigidity needed for a quiver to protect the fletches and shafts from becoming deformed was not as necessary for a bow case. The bow and string, being quite strong, were not much affected by vibration from fast riding on horseback, but dampness, excessive heat, and frost could weaken the bow’s power and the strength and elasticity of the string. In addition, foot soldiers and especially cavalry could not always hold their bow in their hands, as they had to sometimes wield other weapons (sabers, maces, etc.), and at the same time direct their horse. These details of Russian archers are shown quite cleverly in Gerberstein’s description.

Bow cases are not mentioned in any Russian written sources until the 15th century, but they doubtless existed in the 9th-14th centuries. Use of bow cases in Rus’ at this time is reflected in medieval Russian epics, which stretch back, according to Prof. Ju.M. Sokolov, into the oldest times and and reflect the age-old struggle against the nomads and other enemies.[36]Sokolov, Ju.M. Byliny. Moscow,1937, p. 247. Bow cases [налучье / налушне, naluch’e / nalushne] are mentioned in the byliny [epic songs] about Mikhajl Kazarinov and Mikhail Ivanovich Potyk (“He took from its case his taught bow.”)[37]Danilov, op. cit., pp. 208, 217. On a stone carving from the 12th-century Dmitrievskij Cathedral in Vladimir, a cavalry archer is depicted with a quiver and a bow in a case.[38]Rikman, E.A. “Izobrazhenie bytovykh predmetov na rel’efakh Dmitrievskogo sobora vo Vladimire.” KSIIMK. 1952 (47), illus. 7, item 4. The bow case itself, aside from its mouth, is almost completely hidden and it is difficult to judge its shape; but, on later depictions from the 16th-17th centuries, the form of the bow case is well presented, and it completely corresponds to bow cases from the time stored in museums (Illustration 1, items 10 and 11).

Neither leather nor wood remnants of bow cases have been found in excavations of medieval Russian settlements or gravesites. They decay quite easily in the ground, similar to fabric. But, a large number of characteristically-rounded bone hinges, most likely from bow cases, have survived (see Plate 8). These hinges have always been found in graves where there were remnants of bows and quivers with arrows. As a rule, they accompany the hinges from quivers (Plate 9). As with decorative bone plates which were glued or sewn to the bow covers, these hinges date from the 9th-14th centuries, when they were in widespread use throughout all of the European part of the USSR.

Bow cases were somewhat shorter than their bows, in order to facilitate removal. In the 16th-17th century, they became significantly shorter. In antiquity, they were decorated with carved bone plates, which were attached at the stiffest location — at the lower end, gradually widening upward according to the shape of the bow (Illustration 3). During A.V. Artsikhovskij’s excavations in Novgorod, in layers from the 9th-13th century, three decorated plates from bow cases with circular decorations were found, along with signs that they were glued along with other plates and sewn to the leather case.[39]Medvedev, A.F. “Oruzhie Novgoroda Velikogo.” MIA. 1959 (65), p. 148, illus. 11, items 3, 4.[40]jeb: See image JEB5, items 3 and 4.

Bow cases of the nobility from the 16th-17th centuries had a front made of velvet with leather fringe and embroidered with gold. On the inside, they had a soft leather lining. In addition, they were decorated with various metallic plaques. Sometimes, they had a leather base, sewn around the corners, edges and middle with gold and silver thread, in a design imitating various herbs and leaves. The belt was made from leather, decorated with gold braid. The buckles and plaques were often covered in niello and gilt.

The sizes of bow cases were primarily all similar, since the length of the Russian composite bow rarely changed. 16th and 17th century bow cases averaged around 75 cm in length, significantly shorter than the bow itself, even when strung. In the 18th century, they became even shorter. Their width was consistently between 14-32 cm. The weight of one of the bow cases in the Sheremetevo collection was around 1 kg.[41]Lents, op. cit., p. 98, plate XVII.

Quivers from the 16th-17th centuries were a component of a sagadak or saadak, made from the same material and decorated the same as the bow case. The quiver had a pocket on the front for string and a brush. The length of these upper-class 16th-17th century quivers was 40-50 cm, width at the top 17-20 cm, at the bottom 13-15 cm. The weight of the quiver (minus arrows) did not exceed 600 g.[42]idem. p. 99, No. 489-498.

Saadaki were also owned by Russian merchants. It is possible that they were a trade good. In any event, the documents from a 15th century diplomatic correspondence frequently mention that Russian merchants traveling abroad would sometimes carry 2-3 saadaki each.[43]Sb. RIO, vol. 35., pp. 27, 32, 45. Personal weapons were an absolute necessity for merchants to protect their goods from bandits. Marco Polo notes that in 8th century Persia, “merchants without weapons or bows would be killed (by bandits – A.M.) or robbed without mercy.”[44]Polo, op. cit., p. 30. Most likely the same was also true in Rus’ and other countries, forcing merchants to travel with bows and other weapons.

Bow cases were rarely used in Western Europe, and the warrior would store his bow string in his pouch. Quivers there had a prismatic or cylindrical shape with a widening at the bottom. The body was made of wood, and was often covered with parchment and painted, or sometimes covered with animal hide (with the fur side out).[45]Boeheim, W. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Leipzig, 1890, pp. 389-401, illus. 472, 477-479; Demmin, Auguste. Guide des amaeurs d’arms et armures. Paris, 1869, p. 493, illus. 6.

Unlike Western Europe, where archers were frequently unable to use their simple bows because of the elements,[46]jeb: Zing! Keep in mind the time when this book was written. It was de rigeur for Soviet authors to attempt to show the superiority of the peoples of the USSR over the West. the peoples of Eastern Europe and Siberia protected their bows from the ill effects of moisture in bow cases, which were used, for example, by the Nganasany peoples almost until the 20th century.[47]Popov, op. cit., p. 23.

Bow cases and quivers (saadaki) of the Russian, Persian and Turkish nobility were more often used as expensive decorations for ceremonial outings than as actual weapons. For example, in the 17th century, Grigorij Kotoshikhin notes that certain members of the court were required to carry the royal saadaki.[48]Kotoshikhin, Grigorij. O Rossii. St. Petersburg, 1906, p. 25.

Addendum

[jeb: The article references a few images from other sources, some of which I have included below.]

![Manuscript miniature from the Iranian Book of Kings [Shahnameh].](https://b2058619.smushcdn.com/2058619/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/20-317-307-32-C6226058.jpg?lossy=0&strip=1&webp=1)

![Manuscript miniature from the Iranian Book of Kings [Shahnameh]](https://b2058619.smushcdn.com/2058619/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Rustam_Kills_the_Turanian_Hero_Alkus_with_his_Lance-1-817x1024.jpg?lossy=0&strip=1&webp=1)

Footnotes

| ↟1 | Sinitsyn, I.V. “Arkheologicheskie issledovanija Zavolzhskogo otrjada (1951-1953 gg.)” Materialy i issledovanija po arkheologii SSSR (MIA), 1959 (60), p. 168, illus. 59 and 60, item 6; Bobrinskij, A.A. “Otchet o raskopkakh v Chigirinskom u. Kievskoj g. v 1908 g.” Izvestija arkheologicheskoj komissii (IAK). 1910 (35), p. 61; –. “Otchet o raskopkakh u s. Tur’i.” Otchet Arkheologicheskoj komissii (OAK) za 1908. 1912, p. 161; Rykov, P. “Sulovskij kurgannyj mogil’nik.” Uchenye zapiski Saratovskogo universiteta. Vol. IV, iss. 3. 1925, p. 28; Stepanov, P. “Izdelija iz dereva v kurganakh Suslovskogo kurgannogo mogil’nika.” Uchenye zapiski Saratovskogo universiteta. Vol. IV, iss. 3. 1925, p. 76; Novokreschennykh, N.N. “Gljadenovskoe kostische.” Trudy Permskoj uchenoj arkhivnoj komissii. Vol. XI. 1914, p. 72, plate I, items 3 and 26; plate XIII, item 2. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | Gorodtsov, V.A. “Skal’nye risunki Turgajskoj oblasti.” Trudy Gosudarstvennogo istoricheskogo muzeja (Trudy GIM). Iss. 1, 1926, p. 53, illus. 25; Savenkov, I.T. “O drevnikh pamjatnikakh izobrazitel’nogo iskusstva na Enisee.” Trudy XIV arkheologicheskogo s’ezda. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1910, pp. 192, 207, plate 8, illus. II, item 13, illus. XVII, item 2; Rudenko, S. and Glukhov, A. “Mogil’nik Kudyrge na Altae.” Materialy po etnografii. Vol. III, iss. 2. Leningrad, 1927, p. 45, illus. 13; Kiselev, S.V. “Drevnjaja istorija Juzhnoj Sibiri.” MIA. 1949 (9), pp. 294, 299, plate 50, item 24; Evtjukhova, L.A. Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki enisejskikh kyrgyzov. Abakan, 1948, pp. 61-65, illus. 112-114; Orbeli, I.A. and Trever, K.V. Sasanidskij metall. Moscow-Leningrad, 1935, plates 9 and 14. |

| ↟3 | jeb: See Plate 1, items 8-9, for layouts of two types of Russian quiver. |

| ↟4 | Digs by V.F. Gening and A.Kh. Khalikov, 1957 and 1960, in the Archive of the Department of Archeology of the USSR Academy of Sciences (IA AN SSSR). Gening, V.F. and Khalikov, A.Kh. Rannye bulgari na Volge. Moscow, 1964, pp. 47-50, illus. 14, plate XIII, items 1-3, 5-6, 8-9. On their proposed reconstruction of the quiver, it appears that they correctly placed the brackets with two rivets (plate XIII, item 9) and the hooks at the bottom, but the brackets (plate XIII, items 5, 6) for the hooks and the bone plaques (plate XIII, item 18) could hardly have been attached to the body of the quiver. |

| ↟5 | jeb: See Plate 1, item 9. |

| ↟6 | jeb: See Plate 1, item 8. |

| ↟7 | Sinitsyn, I.V. “Arkheologicheskie pamjatniki v nizov’jakh reki Ilovli.” Uchenye zapiski Saratovskogo universiteta. Vol. 39. 1954, pp. 228, 230, illus. 1 and 4 (center). |

| ↟8 | Sinitsyn, I.V. “Drevnie pamjatniki v nizov’jakh Eruslana.” MIA. 1960 (78), pp. 117, 166-168, illus. 45, item 1. |

| ↟9 | idem., p. 117, illus. 44, item 13. |

| ↟10 | Hampel, J. Alterhümer des frühen Mittelalters in Ungarn. Vols. I-III. Braunschweig, 1905, p. 178, illus. 429. |

| ↟11 | Samokvasov, D.Ja. Mogilnye drevnosti severjanskoj Chernigovschiny. Moscow, 1917, p. 14, illus. 16; Rybakov, B.A. “Drevnosti Chernigova.” MIA. 1949 (11), p. 48, illus. 20. |

| ↟12 | jeb: See image JEB1 below, showing a photograph of this silver horn finding. |

| ↟13 | Karger, M.K. Pogrebenie kievskogo druzhinnika X veka.” Kratkie soobschenija Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury Akademii nauk SSSR (KSIIMK). 1940 (5), pp. 79-81, illus. 18; –, 1958, p. 184, illus. 32. |

| ↟14 | Dig by V.I. Zubkov, 1949, Rjazan’ Museum. |

| ↟15 | Sbornik Russkogo istoricheskogo obschestva [Sb. RIO]. 1884 (41), p. 230; Akty istoricheskie. Vol. IV. St. Petersburg, 1842, p. 399 |

| ↟16 | Samokvasov, D.Ja. Mogily Russkkoj zemli. Moscow,1908, p. 242+, burial mounds 12, 13, et. al. |

| ↟17 | Digs by N.I. Veselovskij, 1906. State Historical Museum. |

| ↟18 | Polo, Marko. Puteshestvie. Leningrad, 1940, p. 245. |

| ↟19 | Karpini,Ioann de Plano. Istorija mongolov. St. Petersburg, 1911, pp. 27-28. |

| ↟20 | Danilov, Kirsha. Drevnie rossijskie stikhotvorenija, sobrannye Kirshoju Danilovym. Moscow, 1818, pp. 22-24, 61, 129, 204, 208, 217. |

| ↟21 | Slovo o polku Igoreve. p. 8. |

| ↟22 | Zhitie Antonija Sijskogo. 1648. Folio 235 obv. Storied in the Manuscript Department in the State Historical Museum. |

| ↟23 | Aristov, N. 1866, p. 151. |

| ↟24 | Letopis’ po Ipat’evskomy (Ipatskomu) spisku. St. Petersburg, 1871, under year 1259. |

| ↟25 | Goncharov, V.K. Rajkovetskoe gorodische. Kiev, 1950, pp. 42-43. |

| ↟26 | Karger, M.K. Drevnij Kiev. Vol. 1. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958, p. 167. |

| ↟27 | jeb: See image JEB2 for a picture of a saadak-style quiver. |

| ↟28 | Gerbershtejn, S. Zapiski o Moskovitskikh delakh. St. Petersburg, 1908, illus. between pp. 64-65. |

| ↟29 | idem., pp. 249, 258. |

| ↟30 | idem., p. 187. |

| ↟31 | “Bukvar’ Kariona Istomina 1694 g.” Trudy Moskovskogo arkheologicheskogo obschestva. Vol. XXV, letter Ju. |

| ↟32 | Popov, A.A. “Okhota i rybolovstvo u dolgan.” Sbornik statej pamjati V.G. Bogoraza. Moscow-Leningrad, 1948, p. 23. |

| ↟33 | Arab Archery: An Arabic manuscript of about A.D. 1500: A book on the excellence of the bow and arrow and the description thereof. Trans. by Nabih Amin Faris and Robert Potter Elmer. Princeton, 1945, pp. 154+ |

| ↟34 | Gjuzal’jani, L.T., D’jakonov, M.M. Iranskie miniatjury v rukopisjakh Shakh-Name leningradskikh sobranij. Leningrad, 1935, plate 1, items 17a, 21, 26, 39, 40, 42, 47, 48, 50; Lents, E. , 1895, pp. 98-99. |

| ↟35 | jeb: See images JEB3, JEB4. |

| ↟36 | Sokolov, Ju.M. Byliny. Moscow,1937, p. 247. |

| ↟37 | Danilov, op. cit., pp. 208, 217. |

| ↟38 | Rikman, E.A. “Izobrazhenie bytovykh predmetov na rel’efakh Dmitrievskogo sobora vo Vladimire.” KSIIMK. 1952 (47), illus. 7, item 4. |

| ↟39 | Medvedev, A.F. “Oruzhie Novgoroda Velikogo.” MIA. 1959 (65), p. 148, illus. 11, items 3, 4. |

| ↟40 | jeb: See image JEB5, items 3 and 4. |

| ↟41 | Lents, op. cit., p. 98, plate XVII. |

| ↟42 | idem. p. 99, No. 489-498. |

| ↟43 | Sb. RIO, vol. 35., pp. 27, 32, 45. |

| ↟44 | Polo, op. cit., p. 30. |

| ↟45 | Boeheim, W. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Leipzig, 1890, pp. 389-401, illus. 472, 477-479; Demmin, Auguste. Guide des amaeurs d’arms et armures. Paris, 1869, p. 493, illus. 6. |

| ↟46 | jeb: Zing! Keep in mind the time when this book was written. It was de rigeur for Soviet authors to attempt to show the superiority of the peoples of the USSR over the West. |

| ↟47 | Popov, op. cit., p. 23. |

| ↟48 | Kotoshikhin, Grigorij. O Rossii. St. Petersburg, 1906, p. 25. |

Thank you so much for this!

On the way that the arrows were stored in cylindrical quivers. do you have more information on this? Contrary to what you stated, there is a lot of evidence from many cultures to suggest that cylindrical arrow quivers would hold arrows with their points up with the fletching end in the bottom of the quiver. This article provides a brief overview on that:

https://www.atarn.org/islamic/bede/CLOSED%20QUIVER2001.htm

Of course I can still be wrong and we’re talking about completely different types of quiver though! I hope to hear from you soon!

Hello! I’ve read/heard of this as well. This particular source does not mention the direction of the fletches; neither does my other translation here: https://rezansky.com/crossbows-in-medieval-rus/

Long bow quivers in Rus’ tended to flare at the top because of the fletches, but when I built my crossbow quiver, I also assumed that the fletches would point down. More info here: https://rezansky.com/11th-century-russian-style-crossbow-bolt-quiver/

This is the only scholarly info I have found to date on Russian quivers and crossbows, but I hope to find more!

Nice article. Only error was referring to the bow as “compound” which is one of those unspeakable machines.You meant to say “composite”. Surely a translation from Russian to English.

Vardak Mirceavitch Basarabov