The seventh chapter of Schepkin’s Textbook of Russian Paleography provides a general overview of miniatures/illumination in Russian manuscripts, and their relation to Byzantine and iconographic sources. He provides a general overview, and some detailed history of how the ways nature, buildings, and people were depicted in manuscripts changed over time. Unfortunately, for a chapter specifically focused on art history and styles, he provided infuriatingly few pictures to demonstrate his points, so I have supplemented his images with a number of color images from the 10th-18th centuries. His data on early period is relatively scant, but it’s still a short, interesting essay.

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 6: Miniatures

A translation of Щепкин, В.Н. «Миниатюра.» Учебник русской палеографии. Москва, 1918. с. 73-82. / Schepkin, V.N. “Miniatjura.” Uchebnik russkoj paleografii. Moscow, 1918. pp. 73-82.

[Translation by John Beebe, known in the Society for Creative Anachronism as Boyarin Ivan Matfeevich Rezansky, OL.]

[Translator’s notes: I’ve done my best to convey both the meaning and style from the original. Comments in square brackets and footnotes labeled “jeb” are my own. This document may contain specialized vocabulary related to embroidery, archeology, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Russian history; see this vocabulary list for assistance with some of these terms. This translation was done for my own personal education, and is provided here as a free resource for members of the Society for Creative Anachronism who may be interested in this topic but are unable to read Russian. I receive no compensation or income for this work. If you like this translation, please take a look at other translations I have made available on my blog.]

[The article in the original Russian can be found here:

https://ru.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Файл:Щепкин В.Н. Учебник русской палеографии. (1918) — цветной.pdf.]

Medieval Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters are shown in BukyVede font, cf. https://kodeks.uni-bamberg.de/AKSL/Schrift/BukyVede.htm

A Textbook of Russian Paleography

Chapter 1: Goals and Methods

Chapter 2: Old Slavonic Language and the Slavonic Alphabets

Chapter 3: Dialects

Chapter 4: Materials and Writing Tools

Chapter 5: Вязь (Vyaz’)

Chapter 6: Ornament

Chapter 7: Miniatures (this post)

Chapter 8: Watermarks

Chapter 9: Cyrillic Hands

Chapter 10: Russian Hands in Parchment Manuscripts

Chapter 11: South-Slavic Writing

Chapter 12: South-Slavic Influence on Russia

Chapter 13: Russian Poluustav Script

Chapter 14: Skoropis’

Chapter 15: Steganography (Tajnopis’)

Chapter 16: Numbers and Dates

Chapter 17: Verification of Dates

Chapter 18: Descriptions of Manuscripts

Appendix: Slavonic and Russian Chronology

Chapter 7: Miniatures

The collective noun “miniature” (Rus. миниатюра, miniatjura) and its plural “miniatures” denote pictures in written works, worked by hand in paint. The word “miniature” was borrowed by the Russian language through French, from the Italian. The word miniatura was created from the verb miniare, which was itself taken from the word minium, meaning “red lead,” and as such, the word miniatura originally meant writing or an image worked in red paint, then later came to mean a “red capital” and “a picture in a manuscript,” then later “an image (in red) of very small size,” and finally was understood as “a small size”. The two original meanings of the word disappeared, but the other three have been preserved. In Russia, we have also used our own terms since olden times: a decorated manuscript (Rus. рукопись украшенная, rukopis’ ukrashennaja) (fancy, “tricked out”), and a so-called “facial” manuscript (Rus. рукопись лицевая, rukopis’ litsevaja). The first term is related to the binding and ornament, while the latter is related to the depictions of facial images (Rus. лицо, litso, “face” or “famous person”), that is, to that type of miniature which was predominant in both medieval Russian as well as South Slavic and Byzantine writing. As such, for medieval Greek and Slavonic cultures, the word “facial” (Rus. лицевой, litsevoj) is an exact synonym for “illustrated” or “pictorial” (Rus. иллюстрированный, illjustrirovannyj).

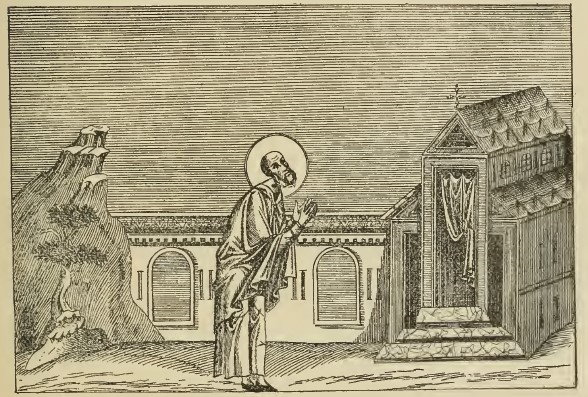

December 3: St. Theodulus.

A major type of pictorial art in Byzantium and among the Orthodox Slavs was iconography (Rus. иконопись, ikonopis’), that is, religious paintings with a generally contemplative mood, and a certain artistic style which evoked this mood. Miniatures, especially Russian ones, was dependent on icon painting in its predominantly religious content, which explains why for such along time other styles of pictorial art did not exist at all in the Russian territories. However, the iconographic style was always strict and consistent, allowing it to serve as a yardstick for measuring the style of miniatures and its changes. On the other hand, miniatures contain infinitely more accurate chronological data than iconography, allowing miniatures to be used in the dating of icons. Not all of the traits of icons were fully expressed equally in miniatures; for example, in miniatures it is more difficult, as a result of their size, to observe changes in facial expressions, as well as the techniques and coloring used in painting faces. These two details of painting are generally less developed in miniatures. On the other hand, in miniatures it is possible to follow the chronological changes in the drawing of figures, landscapes, and buildings, as well as the chronological changes in the use and composition of various solid paints. In light of the overall rarity of works of South Slavic miniatures and the widespread development of Russian pictorial manuscripts, this chapter will primarily look at the paleographic data for Russian miniatures.

The overall evolution of Russian miniatures consists partially of the disappearance of various traits from Byzantine art, and partially from the gradual borrowing of various features from Western art, at first primarily from Germany. Landscapes (Rus. ландшафт, landshaft) were depicted in miniatures as mountainous and sparsely vegetated. The mountains were depicted basically realistically, but of a single designated type: ledged or stepped mountains, which in geography carry the name “wastelands” (Rus. сбросовая гора, sbrosovaja gora, “waste mountain” or “fault-line mountains”). In the 14th century, among both the Russians and the South Slavs, they were depicted as large massifs, dissected by deep gorges into several large steps; sometimes, only a single large mountain was shown. In the 15th century, this almost architectural template of wastelands became more realistic: they were depicted as massifs which have overhangs in either the front or back, and with individual steps which are no longer as regular. In the 16th century, images of mountains became once again geometric, and yet at the same time more ornamental. The massifs were once again vertical, with small, regular steps, and with the top step ending in the rear in semi-circles. The steepness of the steps became quite varied. Also in the 16th century, but less frequently, we also encounter mountains with somewhat distorted figures: the ledges are overall drawn in three-quarters profile, and as a result, one side (usually the left) of the mountain ends in a series of corners. The distortion of the image consists in the fact that the corners are depicted in the form of ships’ prows or birds’ beaks, and their tops, which lie flat, are not depicted at all. This manner was older than Russian 16th century, and was actually brought to Moscow from Byzantium in the 14th century during the birth of Muscovite iconography. Prototypes of this type of mountain are found in Byzantine miniatures as early as the 12th-13th centuries, and this method was borrowed by Italy no later than the 15th century. In the 17th century, the stepped method of depicting mountains became rare and quite formulaic; typically in the 17th century, mountains were depicted only as a general silhouette, with a bit of shade in some parts and some unevenness of the mountain surface. As a result, the typical silhouette of a 17th century mountain became “saddle-shaped”, that is, a hollow with a hill on either end; the hills would lean toward the edges of the drawing. In iconography, the stepped method of depicting mountains was used in the 17th century only in the very best calligraphic icons, and as a result, in the second half of the 17th century, these steps ended in a series of a kind of small creeping branches, or the entire mountain was replaced by a type of bushy plant. This style carried over into the 18th century as well, but in miniatures it was usually not seen. In miniatures from the 18th century, the landscape, if depicted at all, was realistic and of western style, consisting of trees and grasses.

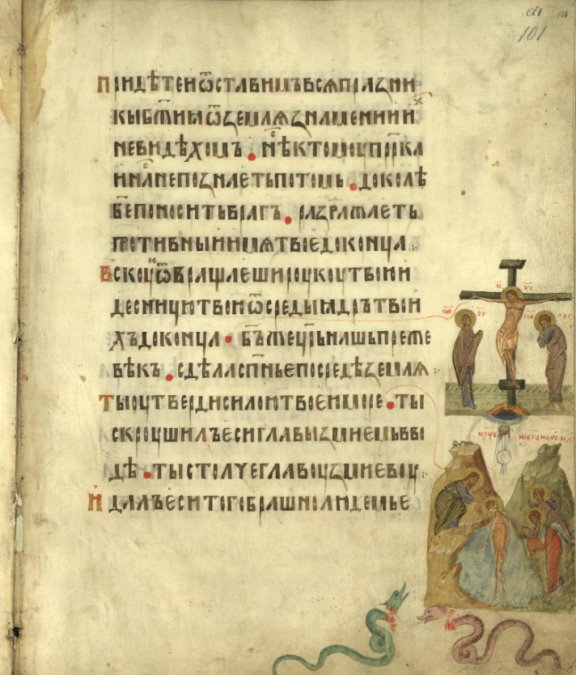

jeb: Miniature from the Kiev Psalter (Rus. Киевская псалтирь, Kievskaja psaltir’), 1397, depicting the Crucifixion and Harrowing of Hell.

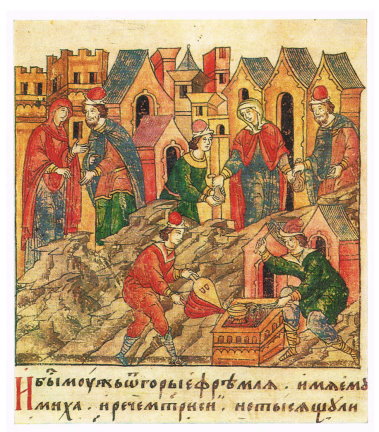

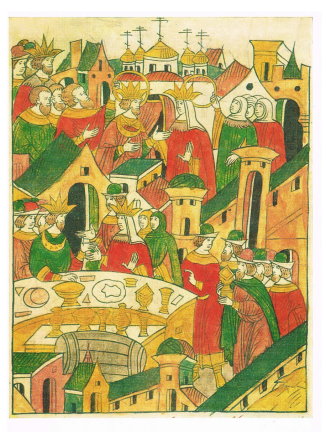

jeb: Series of miniatures from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan IV The Terrible, 1568-1576, depicting the appearance of the angels to Abraham. Photo in public domain. Note the step-wise mountains, bushes, trees, and buildings in 16th century style.

jeb: Review of Russian church architecture, using the Smaller Cathedral of Donskoy Monastery in Moscow as an example. The onion dome sits atop a round tambour, or “drum”, which rises above three rows of large, semi-circular kokoshniki. If the kokoshniki refkected the shape of the arched ceiling inside and were weight-bearing, they would be called zakomary instead.

October 25: The Martyrdom of Sts. Marcian and Martyrius.

Buildings, or to use the old terminology, chambers (Rus. палата, palata), or drawings of buildings (Rus. палатное письмо, palatnoe pis’mo, “chamber writing”) were depicted on Russian icons up to the 16th century almost identically to those on Byzantine icons and miniatures, except that those on Russian icons were typically simpler and plainer. As for Russian miniatures, they carried this iconographic character only up until the mid 15th century.[1]The Menologion of Basil II, a church calendar written around 1000 for the Byzantine emperor Basil II (the brother-in-law of St. Vladimir) is very important for the understanding of ancient Slavonic miniatures. This manuscript is from that time period when Byzantine art was transferred to Rus’. (The original is preserved in the Vatican library in Rome. The drawings were reproduced as engravings in a publication by Cardinal Albani, Menologium Graecorum. Urbino, 1727.) If we exclude the luxurious architectural façades and porticoes against which the Menologion commonly depicts the apostles, prophets, bishops, abbots of monasteries, and servants of the church, then the remaining architecture from the Menologion turns out to be quite simple and uniform. With further simplification and sometimes with distortions, the same types of buildings were reproduced by South Slavic and Russian manuscripts. Manuscripts up through the mid-15th century contained the following types: columns; square towers with flat roofs, sometimes open, and often with an extended cornice; the same kind of tower, covered on one side or sometimes on all four; an octagonal or round tabernacle, covered with a sloped roof, reduced to a sort of tower; a rectangular tabernacle, covered with gables (sometimes abbreviated into a tower), or in rare cases, covered with a semi-cylinder; a rectangular tabernacle, covered with sloped roofs, with two covered wings, that is, a realistic three-naved basilica (or more frequently, abbreviated to a single side nave); a ciborium, or altar canopy, of varying sorts. All of the types listed above depict actual architecture of the early-Christian period. From Byzantine period architecture, we see: a round church with a dome (Rus. купола, kupola) atop a tambour; a square church with a dome atop a “drum” or tambour (Rus. тамбур, tambur); and rarely, five-domed churches of the same type. The kokoshniki [jeb: semi-circular or keel-like decorative elements on the outside of Old Russian churches, which bore no weight and were purely decorative, resembling the female headwear of the same name. See image above.] of the façades in real Byzantine architecture were semi-circular, but in miniatures they were depicted as semicircular, gabled, or patterned. Semicircular kokoshniki could also be pointed or in the form of a three-pointed arch. Gabled and patterned kokoshniki were borrowed by miniatures directly from depictions of arcades (porticoes) and doors; moreover, decorated arcades also appear in Byzantine miniatures by the 12th century. All of these listed types in Byzantine miniatures were also seen in combinations, that is, made up architectural groups. The most complex of these made up depictions of a city: a round, tall wall with square towers; inside the walls, various types of buildings crowd together. In terms of perspective, Byzantine miniatures contained various types of drawings of buildings: 1) façade images, completely avoiding perspective as much as possible; 2) depictions from one corner; the horizon (eye line) runs through the center of the image, while the visual center (center of view) runs through the building’s corner; 3) bird’s-eye views, where the horizon lies above the center of view; 4) depictions from below, where the horizon lies below the center of view; in this last method, the Byzantines made the most mistakes counter to perspective. All four methods were carried over into Slavonic miniatures, but bird’s-eye and façade views were most common. Starting from the middle of the 15th century, Russian miniatures show the influence of western drawing: drawing becomes faster, and perspective becomes better and more varied. Foreigners depicted from nature actual Russian buildings from Novgorod-Pskov, Vladimir-Suzdal’, and Muscovite architecture, including a depiction of Moscow’s Cathedral of the Assumption. In place of the old Byzantine (semicircular) forms, domes take on the Russian, onion-shaped form. At the same time, the old architectural forms are combined into more complex groups. Few illuminated manuscripts from the 15th century have survived to our day, but all of these innovations continued to live on in the more numerous Russian miniatures of the 16th century, which there were two major schools: that of Archbishop Macarius of Novgorod in the first half of the century, and that of Grozny in the second half. The Macarius miniaturists, depicting heavenly and fabulous buildings, sometimes took their combinations of traditional types to very complex architectural conglomerations, which should be called fantastical in the sense that they were completely impracticable and look like they’re about to collapse. Among the Novgorod artisans, we already encounter newcomers from the West, but the Western influence was generally not yet encountered in the strict church miniatures of the Macarius school. When Macarius moved to the Metropolitan See of Moscow, his artisans followed him to Moscow and it appears that here they began to include in their drawings of buildings schematic depictions of the real churches of Vladimir-Suzdal’ and Muscovite architecture, including churches covered with several rows of kokoshniki. Actual cathedrals of the Novgorod-Pskov type, with eight-sloped roofs (with two slopes per side) are rarely seen in Russian icons or miniatures.[2]jeb: You can see a photo of Pskov’s Church of Sts. Koz’ma and Damian from Primostye, an example of this type of “eight-sloped” church, here. Each of the four central walls is gabled, resulting in each having two pitched roofs slanting away from the central drum and dome.

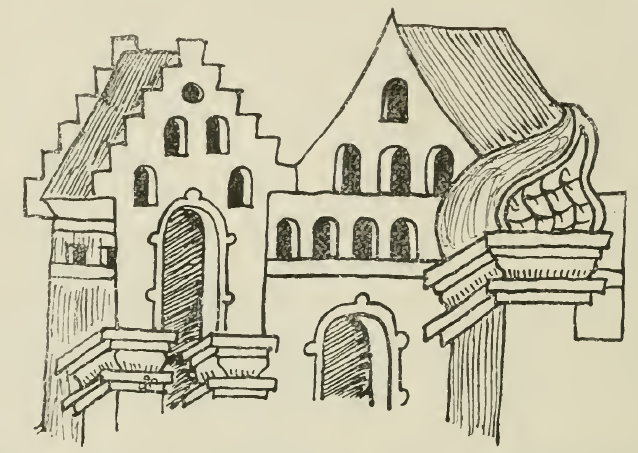

After the Great Fire of Moscow in 1547, the Macarian artisans, in order to restore the church murals, iconostases and icons, united with various other schools of artisans, and from the interactions of these various styles of painting there arose the Royal School. Starting from the second half of the 16th century, the miniaturists of the Grozny School[3]jeb: Named for Ivan IV “The Terrible” (Rus. Иван Грозный, Ivan Groznyj). (his so-called “artisan chamber”, Rus. мастерская палата, masterskaja palata) worked on, among other items, the so-called Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible (Rus. Лицевой Летописный Свод, Litsevoj Letopisnyj Svod, “Collected Facial Chronicle”), which covers the period from the creation of the world to the end of Ivan the Terrible’s reign (almost all of the volumes of this work have survived to our time). In addition to 16th-century Novgorodian traditions, the Grozny artisans also used Western engravings and must have included in their midst Western immigrants. In depictions of the royal palaces and interior views of large cities, the Grozny artisans established an architectural painting style which was exceptionally luxurious and rich in motifs, which incidentally included several Western styles which were previously unseen in Russian miniatures, chief among which was the use of externally stepped borders (Rus. ступенчатый наличник, stupenchatyj nalichnik) on gabled pediments (Rus. двускатный фронтон, dvuskatnyj fronton) (see illustration 35).[4]This type of border is well known in both the secular architecture of the late Gothic style, as well as in German miniatures from the same period. It should be distinguished from the stepped interior decoration of gabled pediments, which are encountered in Byzantine miniatures, borrowed from Christian art; cf. the stepwise patterns worked into squares in Christian mosaics. In the 17th century, depictions of buildings in Russian miniatures was quite simple and was largely limited to several stereotypical forms. The stepwise pediment became quite rare. In the mid-17th century, we see, gradually strengthening over time, a Western influence through engravings of Biblical content, German, and Dutch.[5]Particularly influential in this time was the engraved Piscator Bible (Rus. Библия Пискатора, Biblia Piskatora), known in Moscow since at least the middle of the 17th century. jeb: This printed bible was named after its creator, the Dutch engraver Claes Jansz. Visscher, aka Nicolas Joannes Piscator.

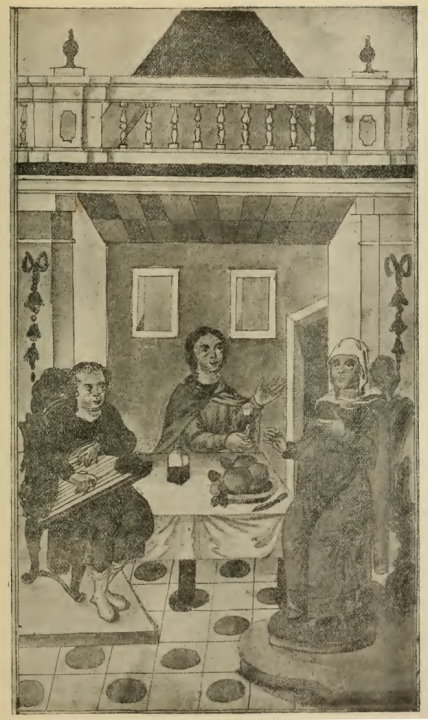

In the best works of Muscovite iconography from the second half of the 17th century (icons by the royal icon painter Simon Ushakov and his students), the buildings were luxurious and complex, using all of the architectural effects from the Western Renaissance, building painting styles inherited from Russian iconography, and sometimes the actual architecture of Moscow. This masterly painting of buildings passed into the best Palekh icons from the 18th and early 19th centuries and in iconography in general, but did not arise in manuscripts in terms of its complexity. Building painting in Russian manuscripts of the 18th century continued to use the templates from the 17th century, adding to it several (a few) Western types. In the depiction of internal setting (thrones, baldachins, furniture, stucco décor, etc.) in 18th-century manuscripts (the second half), the Rococo style often appears, or less frequently Louis XVI style. See illustration 36, a miniature from an 18th century Book of Feasts (Rus. Цветник, Tsvetnik, “Flower Garden”).

The use of color changed over the centuries. During the times of parchment manuscripts, miniatures were heavily grounded in white (lead), and paints were mixed onto this white, superimposed in long strokes, which created an effect of plasticity. This Byzantine technique, heavily strengthened in Russia, disappeared during the time of paper manuscripts. Paper made possible the lighter technique of watercolor painting which, not without the influence of Western artisans, came to be used in several variants. Where we also find numerous paper manuscripts (even in the 16th century) with miniatures which were heavily primed and painted in thick paints, these are rare direct copies of miniatures on parchment. Such was the illuminated 16th-century Uvarov Paleya, copied for Ivan the Terrible’s courtiers from an illuminated parchment 14th-century paleya,[6]jeb: A paleya (Rus. палея) was a type of medieval Russian manuscript which laid out Old Testament history, sometimes combined with Apocryphal or other Christian theological works and reasoning. which has survived to modern day and is preserved in the library of the Aleksandr Nevsky Lavra. On plain, easily absorbent paper, this technique does not provide good results. In the miniatures of the 16th century, the paints were more varied and richer in shades due to skillful mixing. Gold was used only in miniatures of a iconographic character (for example in large depictions of the Evangelists in a copy of the Gospels) and then almost only as “light” (that is, the background) and crowns (haloes). In the 17th century, paints were numerous and simple, that is, they were typically only in basic, unmixed tones. On the other hand, in the second half of the 17th century, coloration was content to be limited to three colors: yellow, red, and green in plain, basic tones; a fourth color was black, used to draw outlines and sometimes shaded depths (the abyss of Hell, or the interiors of buildings seen through doors and windows). The combination of these basic tones was resourceful and calm, but the observer has no thought about the poverty of color. This “three color style” continued into the 18th century. Throughout the 18th century, a new complicated color scheme arose. Ignoring the appearance of new compositions of paint and therefore new shades which replaced the older cinnabar, green and ocher, in miniatures from the late-18th and 19th centuries, we see completely new basic colors: bright purple and crimson (carmine), which were totally alien to old Russian miniatures.

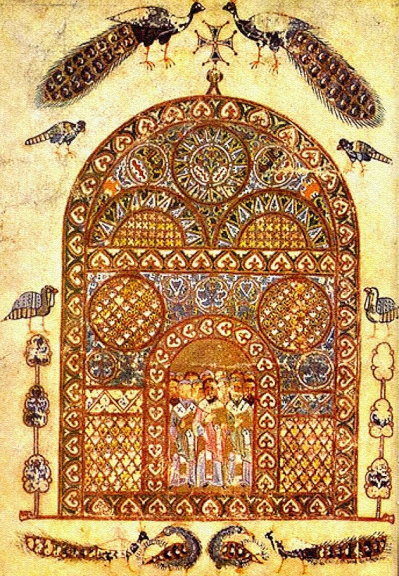

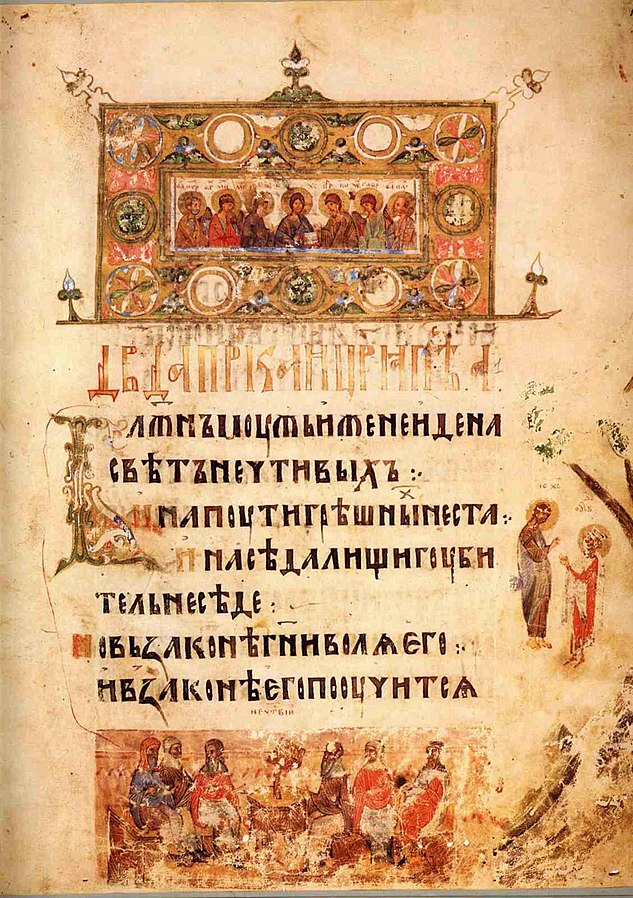

jeb: Carpet page from the Svyatoslav Izbornik, Kiev, 1073. Photo in public domain.

jeb: Miniatures from the Kiev Psalter, 1397. Photo in public domain.

jeb: Miniature from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan IV The Terrible, 1568-1576, depicting a wedding feast. Photo in public domain.

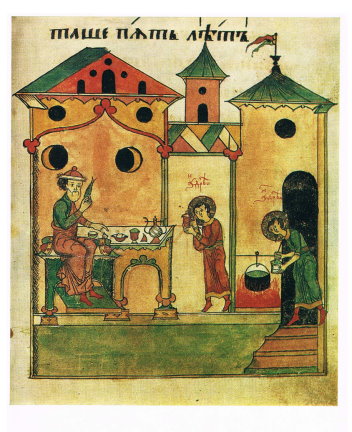

jeb: Miniature from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan IV The Terrible, 1568-1576, depicting a jeweler at work. Photo in public domain.

jeb: Miniature from The Life of Anthony of Siyisk, 1648, depicting a meal. Photo in public domain.

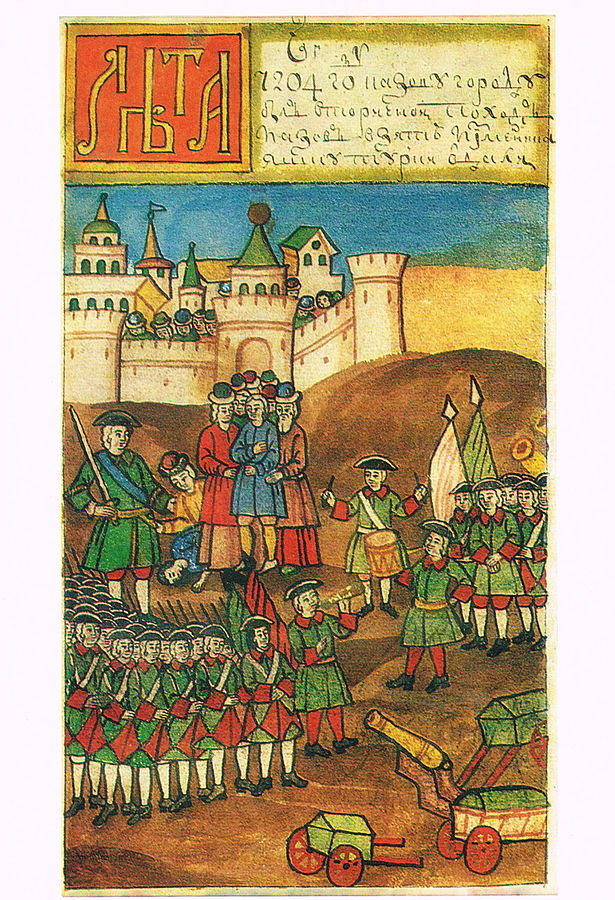

jeb: Miniature from Krekshin’s History of Peter I, first half of the 18th century, showing the Capture of the Fortress of Azov. Photo in public domain.

The drawing of figures, typically covered in clothing, during the time of parchment manuscripts, that is, when the Byzantine style was predominant, had a very sculptural character. Sharp contrasts of light and dark tones indicated the largest of protrusions or depressions. The folds of clothing were coarse and relatively straight, as when wearing thick woolen material. In the end, this was a heritage of forms used in antique sculpture. In the 15th century, Russian miniatures adopted (from engravings and directly) the influence of Western painting which, as we have seen, was expressed as a transition to a lighter, more watercolor style. In this style, figures were less plastic, but at the same time became more detailed. Their poses and gestures became less general and more dramatic. However, all of these adoptions did not create a new direction: they remained more or less incidental and did not disturb the basic Byzantine iconographic style. In the 16th century, the so-called Novgorod style, which was mainstream and the best, represented a kind of regulation of the Byzantine drawing of figures with the use of straight and sharp lines. In the Grozny miniatures, drawing was pretty much identical, but with a touch of a kind of artistic and somewhat mannered (Western) realism in the way folds of clothing were drawn. In the 17th century, the drawing of figures was generally quite poor. The use of inherited straight and simple lines dominated, but they were used only by rote, without any idea of the shapes of covered bodies, and as a result, the figures’ bodies cannot be seen under the clothing, have no sense of shape, and often stand strangely. Deviations from iconographic style (Rus. фрязь, frjaz’, “mud/dirt”), that is, Western pictographic styles, especially Baroque, which infiltrated into iconography starting in the 2nd half of the 17th century) in the area of drawing were poorly represented in miniatures, for the drawings of these styles were too complex and noisy for folk miniaturists, but sometimes can be seen in miniatures from the late 17th century through an abundance of small, complex folds in clothing, as if depicting lighter silk materials. Baroque folks also appear in original iconographic designs, on the edges of clouds and the wings of angels (see Illustration 37). These deviations carried forward into the 18th century. In the sphere of faces, these deviations created numerous portraiture and scenic depictions, and as such reflected Russian reality.

Footnotes

| ↟1 | The Menologion of Basil II, a church calendar written around 1000 for the Byzantine emperor Basil II (the brother-in-law of St. Vladimir) is very important for the understanding of ancient Slavonic miniatures. This manuscript is from that time period when Byzantine art was transferred to Rus’. (The original is preserved in the Vatican library in Rome. The drawings were reproduced as engravings in a publication by Cardinal Albani, Menologium Graecorum. Urbino, 1727.) If we exclude the luxurious architectural façades and porticoes against which the Menologion commonly depicts the apostles, prophets, bishops, abbots of monasteries, and servants of the church, then the remaining architecture from the Menologion turns out to be quite simple and uniform. With further simplification and sometimes with distortions, the same types of buildings were reproduced by South Slavic and Russian manuscripts. Manuscripts up through the mid-15th century contained the following types: columns; square towers with flat roofs, sometimes open, and often with an extended cornice; the same kind of tower, covered on one side or sometimes on all four; an octagonal or round tabernacle, covered with a sloped roof, reduced to a sort of tower; a rectangular tabernacle, covered with gables (sometimes abbreviated into a tower), or in rare cases, covered with a semi-cylinder; a rectangular tabernacle, covered with sloped roofs, with two covered wings, that is, a realistic three-naved basilica (or more frequently, abbreviated to a single side nave); a ciborium, or altar canopy, of varying sorts. All of the types listed above depict actual architecture of the early-Christian period. From Byzantine period architecture, we see: a round church with a dome (Rus. купола, kupola) atop a tambour; a square church with a dome atop a “drum” or tambour (Rus. тамбур, tambur); and rarely, five-domed churches of the same type. The kokoshniki [jeb: semi-circular or keel-like decorative elements on the outside of Old Russian churches, which bore no weight and were purely decorative, resembling the female headwear of the same name. See image above.] of the façades in real Byzantine architecture were semi-circular, but in miniatures they were depicted as semicircular, gabled, or patterned. Semicircular kokoshniki could also be pointed or in the form of a three-pointed arch. Gabled and patterned kokoshniki were borrowed by miniatures directly from depictions of arcades (porticoes) and doors; moreover, decorated arcades also appear in Byzantine miniatures by the 12th century. All of these listed types in Byzantine miniatures were also seen in combinations, that is, made up architectural groups. The most complex of these made up depictions of a city: a round, tall wall with square towers; inside the walls, various types of buildings crowd together. In terms of perspective, Byzantine miniatures contained various types of drawings of buildings: 1) façade images, completely avoiding perspective as much as possible; 2) depictions from one corner; the horizon (eye line) runs through the center of the image, while the visual center (center of view) runs through the building’s corner; 3) bird’s-eye views, where the horizon lies above the center of view; 4) depictions from below, where the horizon lies below the center of view; in this last method, the Byzantines made the most mistakes counter to perspective. All four methods were carried over into Slavonic miniatures, but bird’s-eye and façade views were most common. |

|---|---|

| ↟2 | jeb: You can see a photo of Pskov’s Church of Sts. Koz’ma and Damian from Primostye, an example of this type of “eight-sloped” church, here. Each of the four central walls is gabled, resulting in each having two pitched roofs slanting away from the central drum and dome. |

| ↟3 | jeb: Named for Ivan IV “The Terrible” (Rus. Иван Грозный, Ivan Groznyj). |

| ↟4 | This type of border is well known in both the secular architecture of the late Gothic style, as well as in German miniatures from the same period. It should be distinguished from the stepped interior decoration of gabled pediments, which are encountered in Byzantine miniatures, borrowed from Christian art; cf. the stepwise patterns worked into squares in Christian mosaics. |

| ↟5 | Particularly influential in this time was the engraved Piscator Bible (Rus. Библия Пискатора, Biblia Piskatora), known in Moscow since at least the middle of the 17th century. jeb: This printed bible was named after its creator, the Dutch engraver Claes Jansz. Visscher, aka Nicolas Joannes Piscator. |

| ↟6 | jeb: A paleya (Rus. палея) was a type of medieval Russian manuscript which laid out Old Testament history, sometimes combined with Apocryphal or other Christian theological works and reasoning. |